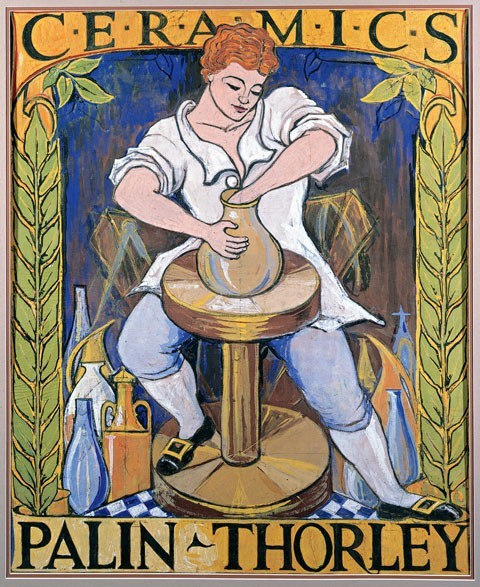

A cartoon, or preliminary drawing, for the sign that hung in front of Thorley’s studio-shop for many years. Opaque paint on paper. 26" x 33". Thorley realized the importance of advertising, and his papers reveal many drawings and sketches for signs. Some incorporate his wife’s name—Edith—instead of his. Even though this sign could not have been made before 1950, it reflects, as do many of his later ceramics, his interest in the designs of his earlier life, from the 1920s and 1930s. The original sign is in the collection of Fred Miller. (Unless otherwise noted, all illustrated objects are in the author’s collection and all photos are by Gavin Ashworth.)

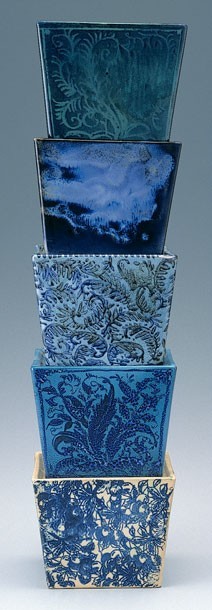

Jardinieres or square bricks, Palin Thorley, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1960. Whiteware. 4" x 5" x 5". The bases have Thorley’s experimental marks and his monogram

Trenthan Woods Autumn, by John Thorley, 1904. Watercolor on paper. 14" x 20". “And my father dropped the pottery now and he’s painting—painting landscape. . . . [He] would go sketching, mostly in Dovedale, in Derbyshire, all the ancient places around Staffordshire. It is beautiful country there, most beautiful in the world. There’s nothing to touch it anywhere—I still think that. So I would go to carry his traps, which he called them, which was a sketching umbrella to keep the sun off of him when he painted his watercolors, his paint boxes, and so forth, and maybe some lunch in a bag.”

Drawings for square bricks, Palin Thorley, ca. 1960. Pencil and watercolor on paper. Each 7" x 9 1/2".

Jardinieres or square bricks, Palin Thorley, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1960. Whiteware. 4" x 5" x 5". The bases have Thorley’s experimental marks and his monogram.

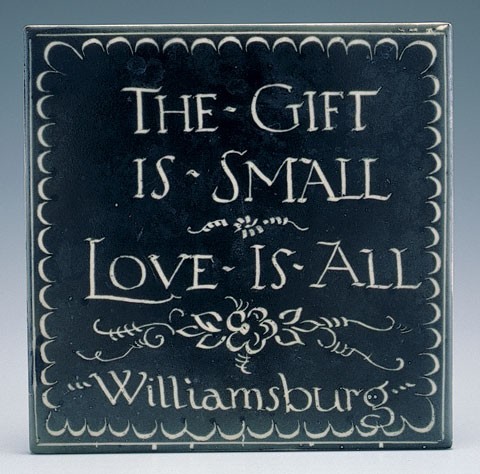

Plaque, Palin Thorley, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1955. Whiteware. W. 6". (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.)

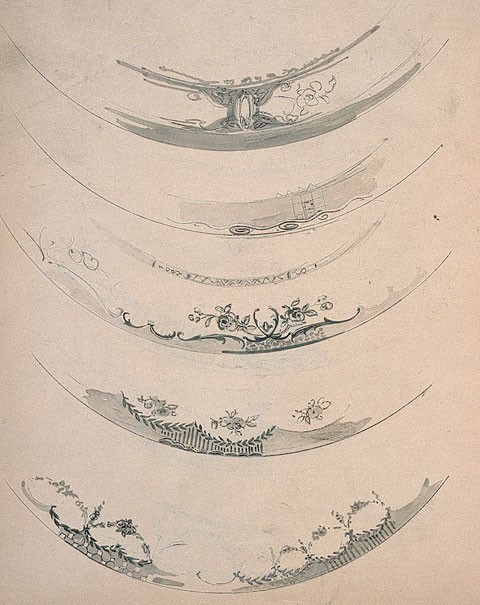

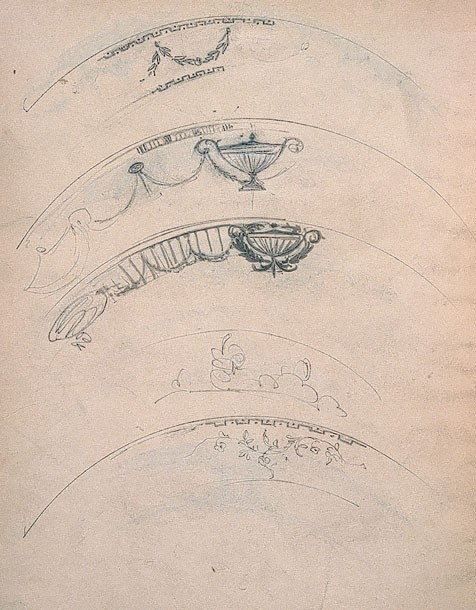

Drawings for plates, Palin Thorley, ca. 1930–1940. Watercolor on cardboard. 10" x 10".

Drawings for plates, Palin Thorley, ca. 1930–1940. Watercolor on cardboard. 10" x 11".

Covered jars, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1914. Whiteware. Left: H. 4". Signed on interior bottom: “J. P. Thorley 1914.” Impressed on exterior bottom: “WEDGWOOD.” (Another covered jar with the same mark is at Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) Right: H. 3 3/4". Unsigned. Mark on bottom: printed Portland vase and “Wedgwood England.”

Sauceboat, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1953. Creamware. L. 9". This design, known as the Edme pattern, was created about 1906 and is still in production at Wedgwood. In an interview Thorley mentioned that he “helped design the Edme pattern,” and in a draft of a letter to David Buten ca. 1973 he wrote, “Edme Pattern: I remember the advent of this fine shape—Mr. Goodwin had me do a number of detail drawings for various purposes and for Mr. Austin to model from. I used to sit watching Mr. Austin at work on it.”

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1914. Bone china. D. 9". Mark on reverse: printed Portland vase above “Wedgwood/England.” Signed and dated lower right of scene: “J. P. Thorley / 1914.”

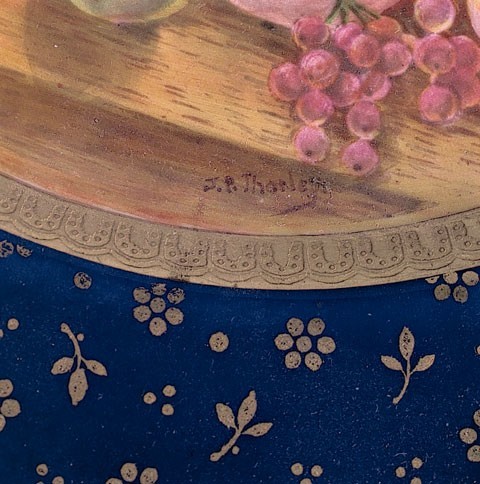

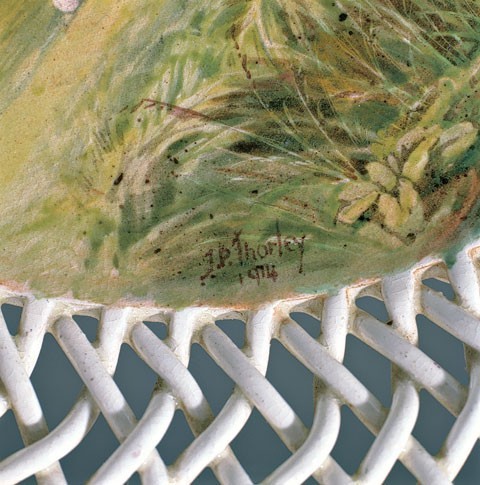

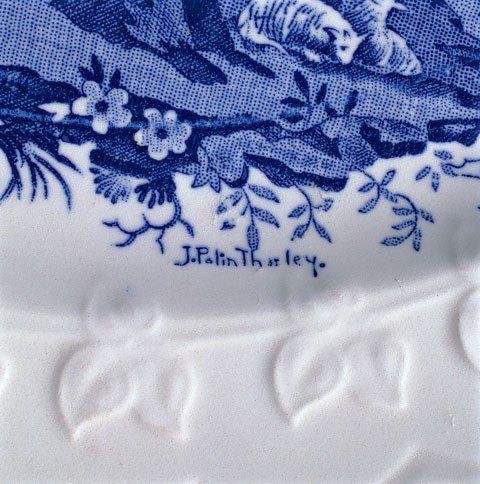

Detail of the signature on the plate illustrated in fig. 10.

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, ca. 1914. Bone china. D. 9". Inscribed by hand, on reverse: “Dusty Grouse.” Mark on reverse: printed Portland vase above “Wedgwood / England.”

Theodore Roosevelt plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1906– 1914. Bone china. D. 10 1/2''. (Collection of the White House, Washington, D.C.) The Theodore Roosevelt service was made by Wedgwood for the White House during Roosevelt’s presidency (1901–1909).

Theodore Roosevelt plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1906– 1914. Bone china. D. 10 1/2''. (Collection of the White House, Washington, D.C.) The Theodore Roosevelt service was made by Wedgwood for the White House during Roosevelt’s presidency (1901–1909).

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1906–1914. Bone china. D. 9". Signed: “J. P. Thorley.” Mark on reverse: printed Portland vase above “Wedgwood / England.” Thorley started to work as a painter at Wedgwood in 1906. His first “apprentice” plate was dated Nov. 4, 1906. This plate shows a view of Venice. Thorley kept it in his possession for many years, and it was found in 1985 when his studio and house were cleared.

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1914. Bone china. D. 9 1/4". Signed lower right: “J P Thorley 1914.” Mark on reverse: printed Portland vase. Thomas Allen, a ceramic painter and head of the painting department at Wedgwood, prepared a sketch book of his original drawings and watercolors which remained at the factory when he left, a short time before Thorley went to apprentice there. Among the illustrations Thorley copied from Allen’s book are this one, of a young Scot playing a bagpipe, and the lass in a field on the plate illustrated in fig. 16.

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1914. Bone china. D. 9 1/4". Signed lower right: “J P Thorley 1914.” Mark on reverse: printed Portland vase. (Collection of the Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) Thorley copied this image from Thomas Allen’s book; see fig. 15.

Plate, Wedgwood, Burslem, England, 1914. Whiteware. D. 9 1/4". Signed and dated lower right: “J. P. Thorley, 1914.” Impressed on reverse: Wedgwood mark. Thorley painted two plates with a basketwork rim. This one, made of earthenware rather than the usual bone china, remained in his collection until he died.

Detail of the signature on the plate illustrated in fig. 17.

Plate, New Chelsea Porcelain Co., Longton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1923. Bone china. D. 8 1/2". Mark on reverse: New Chelsea mark incorporating an anchor. It has been said that the New Chelsea mark was not used until “c. 1936+,” which suggests that the mark was either used much earlier than recorded or, more likely, that Thorley’s designs continued to be used after he left the factory. The plate was found in Thorley’s studio.

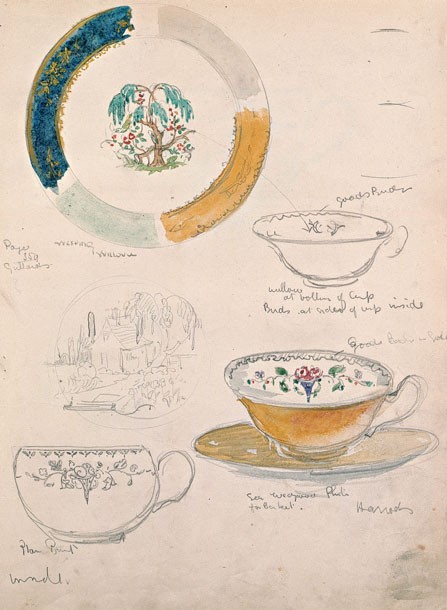

Page from Thorley’s drawing book illustrating the design of the plate illustrated in fig. 19. Thorley called this design Weeping Willow. A line drawn from the tree on the plate to the uncolored sketch of the cup to the right accompanied instructions—“willow at bottom of cup, birds at sides of cup inside”—that agree with the existing cup except that the separate birds are on the exterior.

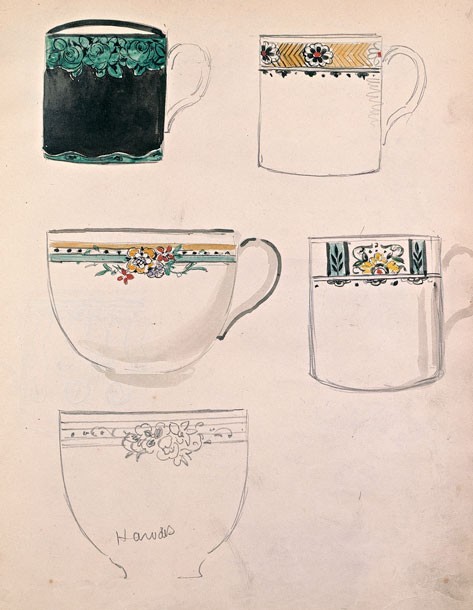

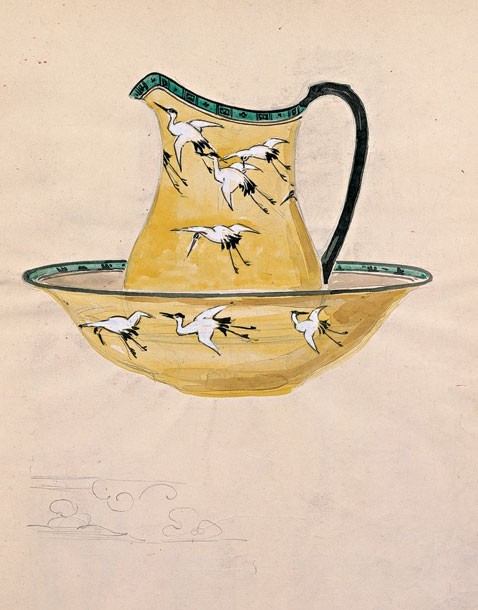

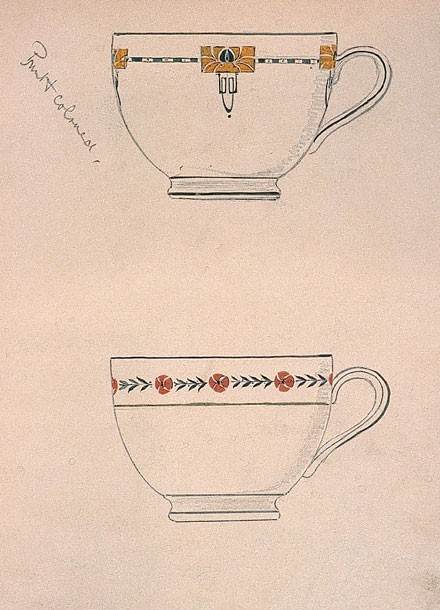

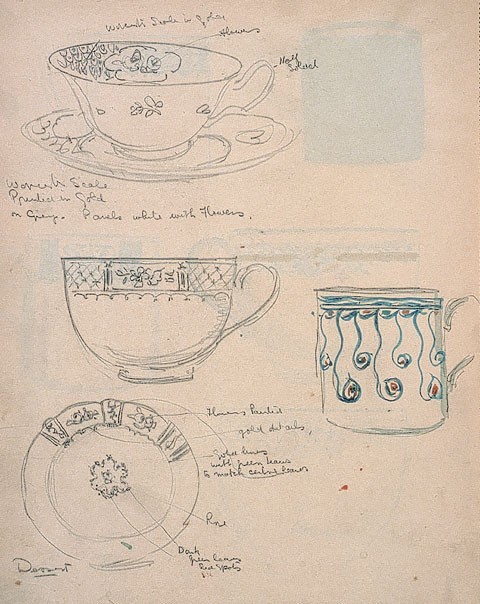

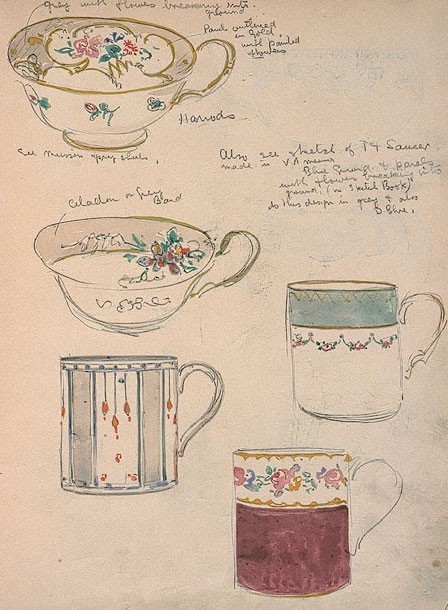

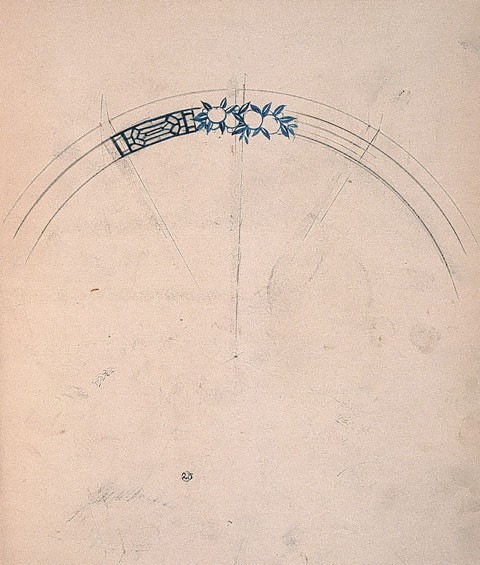

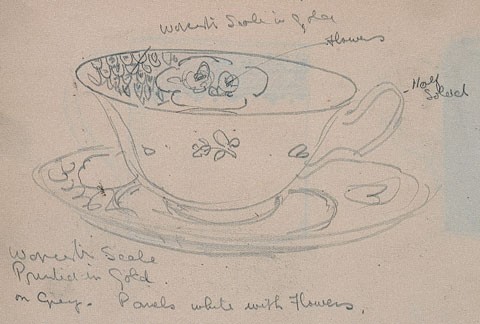

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

11 Pages from a notebook of Thorley’s sketches and watercolors showing ceramic objects such as wash pitchers and basins, cups and saucers, and plates. Many are annotated “printed” or “painted” and include information regarding color, size, estimated cost, possible markets (such as “Harrods”), and the sources of—or inspirations for—his design (for example, “see House & Garden Dec 1920 page 26”). Based on the styles, the relationships between the drawings and examples made at New Chelsea, and a small clipping in the book from a London newspaper dated 1923, I believe Thorley used this drawing book during his years at New Chelsea.

Cup and saucer, New Chelsea Porcelain Co., Longton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1923. Mark on reverse: Chelson mark. Inscribed: “Henwood Johannesburg.” These pieces display Egyptian-motif decoration, including a scarab, and a Chelson mark that was used in the early 1920s. They were made for Henwood, a department store in Johannesburg, South Africa.

A complete service in this design survives with the inscription “W. Savill & Co. Porcelain House, 22 Oxford Street, W1,” along with the mark. Thorley stated in an interview: “So I made my designs and then went up to London and I went to see Mr. Savill of Savill and Company, Oxford Street. Mr. Savill had a very beautiful china store there, china and glass. So when I showed him these Egyptian patterns, he picked one out and thought it was beautiful. He bought it. I reproduced it at the plant and shipped it to Savill . . . who put a big window display . . . right on Oxford Street, London.”

Clipping from a London newspaper, March 8, 1923. This clipping illustrating women’s hats in the Egyptian style was found in Thorley’s New Chelsea sketchbook. Note the scarab on the second hat from the left.

Partial coVee service, New Chelsea Porcelain Co., Longton, StaVordshire, England, ca. 1923. Whiteware. H. of coVee pot: 5 3/4". Mark: New Chelsea. The design of these pieces found in the attic at Thorley’s shop was influenced by the discovery in 1923 of the tomb of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun (r. 1333–1323 b.c.), which had launched an international revival of Egyptian motifs.

Plate, New Chelsea Porcelain Co., Longton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1923. Whiteware. D. 7". The scale decoration on the edge of the plate’s rim is in a style that was popular in the eighteenth century at Worcester and other English porcelain factories.

Detail of the mark used on the plate illustrated in fig. 25. Part of the Chelson mark on the plate states “MANUFACTURED / FOR / HARRODS LTD LONDON / ENGLAND.” Thorley suggests in his sketch book that some of the pieces he illustrated would be appropriate to offer to Harrods, a London department store.

A teacup drawing from Thorley’s book showing the Worcester Scale decoration used on the plate illustrated in fig. 25. Both the scale decoration and the flowers in the ogee reserves can be seen on the drawing of a related teacup in the drawing book Thorley used during the years he was at New Chelsea. A note above the drawing (and pointing to it) reads, “Worcester Scale” and, below, “Worcester Scale Printed in Gold on Gray—Panels white with Flowers.” Blue scale was most popular in the eighteenth century, but pink scale and gold scale were also produced.

“Chatelaine,” J. Palin Thorley, Staffordshire, England, 1921. Bone china. H. 12". Signed; see fig. 29 for detail. This figure of a chatelaine in medieval dress was made during either Thorley’s last days at Simpsons or his early days as head of the art department at the New Chelsea Porcelain Co. It is most likely he created this on his own, not as part of the factory’s production, because both Simpsons and New Chelsea specialized in dinner ware and because so few examples of this figure appear to have been made. Stories that Thorley made only three of them—one of which was admired by and thus given to Queen Mary—cannot be verified, although he does say that the figure was admired by her. Thorley must have kept the mold, for a green (unfired) example, with head missing, was found in his studio in 1986 (see fig. 30). A letter to him from a customer, dated December 8, 1971, states, “We are eagerly awaiting the Chatelaine figurine. It will be our most prized possession,” which indicates that he promised to produce one for a client at that late date. In the Thorley papers there is an early photograph of the chatelaine—which may or may not be this example—that has the unexplained date “1917” written on the back.

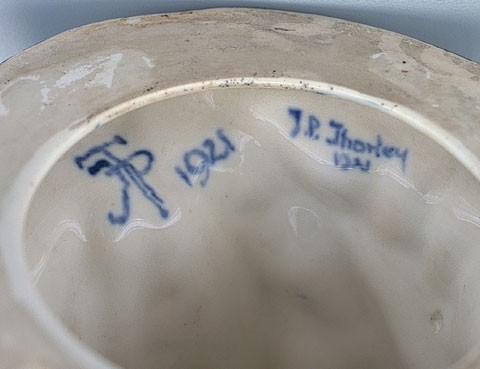

Detail of the marks on the base of the chatelaine illustrated in fig. 28. Thorley marked the figure twice, once with his monogram and date, once with his name and date.

“Chatelaine,” J. Palin Thorley, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1970. Greenware. This unfinished figure, with its head missing, was made from the same mold that was found in Thorley’s studio in 1986.

Plates, Charles Allerton & Sons, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1925. Left: D. 7 1/2". Right: D. 6 1/2". These examples, which bear the Allerton mark on the reverse, were found in the attic of Thorley’s studio-home. They were kept with other pieces that had been made in potteries where he had worked and whose designs were confirmed to be by him. Nevertheless, the attribution to Thorley of these particular plates remains tenuous.

Plate, Charles Allerton & Sons, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1925. Whiteware. D. 5 1/2". This unmarked plate was found in Thorley’s attic, along with pieces designed by him. Plates are recorded in this pattern that are impressed on the reverse with numbers ranging from 24 to 40, indicating that the plates—and most likely the decoration—were made from at least 1924 to 1940, both during and after Thorley’s stint at Allerton. It is possible that this is one of the patterns that Thorley had Mrs. Woolley reestablish.

Cup and saucer, Charles Allerton & Sons, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1925. Whiteware. Cup: H. 2 1/2". Saucer: D. 5". Mark on saucer: “Imperial China, Charles Allerton& Sons, England.” The mark is one that was used during Thorley’s tenure.

Plate, Charles Allerton & Sons, England, ca. 1925. Whiteware. D. 5 3/4". Mark: “A” within a wreath. It is possible that the term Thorley ware, which appears as part of the Allerton mark on this plate, does not refer to Palin Thorley, as the design is less sophisticated than ones usually attributed to him. The mark (see fig. 35) is said to have been used beginning ca. 1929; Thorley left Allerton in 1927. It is possible that the mark was used earlier than recorded. As the only non-family member on the board, Palin Thorley clearly was important to the Allerton pottery. Moreover, it is unlikely that another potter named Thorley would have had ware named for him, particularly so soon after Palin left. Palin’s younger brother Noel is perhaps a possibility, although whether he worked at Allerton is not known. According to a November 1951 article in the Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review, in about 1945 Noel opened a pottery in which he was a “small fancyware potter.”

Detail of the mark used on the plate illustrated in fig. 34.

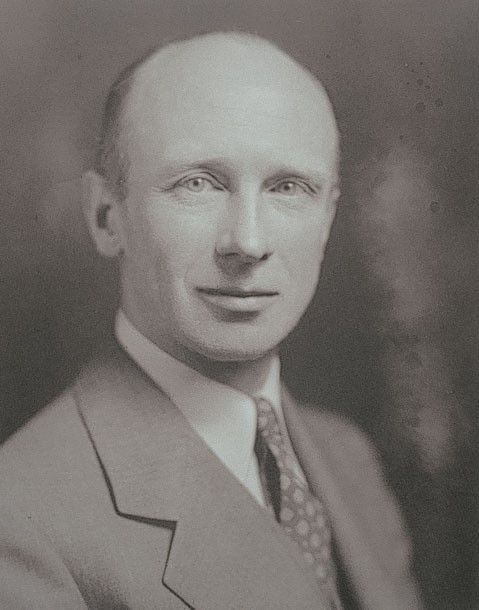

Photograph of Palin Thorley, taken in New York City in the mid- to late 1930s. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Photograph of the Thorley residence, Parkway, East Liverpool, Ohio. Inscribed on the back: “Residence of J. P. THORLEY (3 acres) land next to Country Club.” (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Photograph of Edith Bolling Thorley, Palin’s wife, in the garden of their home in East Liverpool, ca. 1920. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) The Thorleys were married in 1916, during World War I, and were devoted to each other until her death, in 1975, an event from which he never recovered. In my last visits with him, during any break in the conversation, he would shake his head and repeat, “Oh, my poor Edith.”

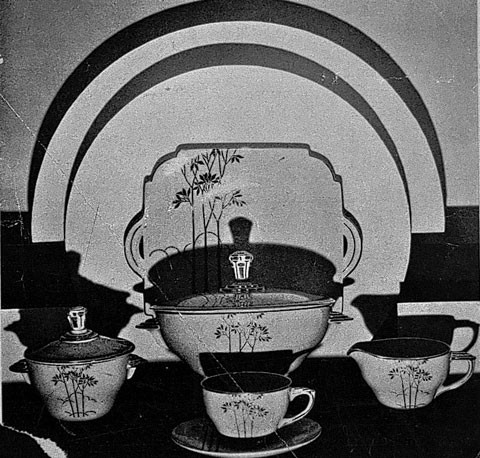

Illustrated in Pottery and Glass Salesman (March 1941) are the three plates shown here. The caption reads: “The next important development after the introduction of the Ivory body was the umbertone body, which was the first narrow-rim plate ever jiggered in America. The patterns illustrated here are ‘Strafford,’ ‘Duo-Bloom,’ and ‘Palm.’”

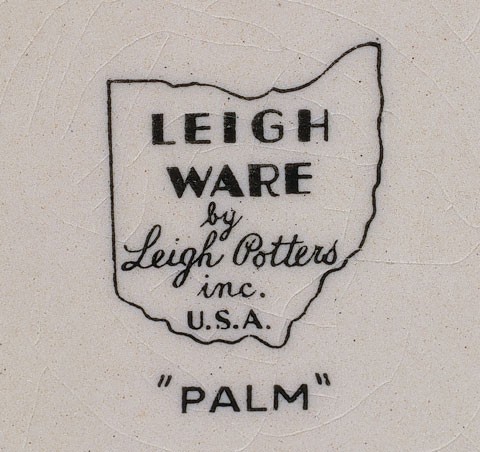

Leigh Ware dinner plates, Leigh Potters, Alliance, Ohio, 1930. Whiteware. D. 9". Left: Duo-Bloom design. Marks: “Umbertone” and the Leigh mark. Right: Palm, PT-115 design. Mark: Leigh mark. These plates were found in Thorley’s attic.

Detail of the mark used on the Palm plate illustrated in fig. 40, right.

Nouvelle plate, Knowles, Taylor, and Knowles, American Chinaware Corp., East Liverpool, Ohio, 1930. Whiteware. D. 6". Mark: “K. T. & K.”; “4 8 30” (possibly date of manufacture). Taylor, Smith & Taylor was one of the small potteries incorporated into the American Chinaware Corp. The Nouvelle form, attributed to Thorley, is decorated here with the Top o’ the Hill pattern and is reproduced in an article about the Nouvelle shape (see fig. 43). The plate was found in Thorley’s attic.

Clipping, “American Chinaware Corp. Has Many New Designs,” China, Glass, and Lamps, June 1930, p. 19, ill. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) This article contains a discussion of the Nouvelle form and shows the plate that is illustrated in fig. 42.

Partial Monte Carlo service, American Chinaware Corp., East Liverpool, Ohio, 1930. Whiteware. D. largest plate 9". L. sauceboat 8 1/4". Marks: “AMERICAN CHINAWARE CORP.” encircling the overlapping monogram “ACC”; “H-8-30” (possible date of manufacture). (Courtesy, Jo Cunningham Collection.)

Partial Monte Carlo service, American Chinaware Corp., East Liverpool, Ohio, 1930. Whiteware. D. largest plate 9". L. sauceboat 8 1/4". Marks: “AMERICAN CHINAWARE CORP.” encircling the overlapping monogram “ACC”; “H-8-30” (possible date of manufacture). (Courtesy, Jo Cunningham Collection.)

Clipping, “American Chinaware Corp. Has Many New Designs,” China, Glass, and Lamps, June 1930, p. 30, ill. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Poinciana plate, American Chinaware Corp., Sebring, Ohio, ca. 1930. Whiteware. D. 9". The shape of this plate is identical to the two with the Leigh marks (see figs. 40, 41) as well as the Nouvelle examples (see fig. 42). The name on the reverse, “Poinciana,” is not among those listed by Harvey Duke in Official Price Guide to Pottery and Porcelain (1995), pp. 42–45, as appearing on that shape. Like most of the others illustrated from this period, this plate was found in Thorley’s attic.

Detail of the printed mark on the plate illustrated in fig. 46: “Amerce [possibly Amercé] / DINNERWARE / AMERICAN CHINAWARE CORP.” ; and “POINCIANA” (handwritten). The printed mark is very rare. No date letter is found.

English Abbey plates, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933–1950. Whiteware. D. 9 1/4". These

dinner plates show the English Abbey design in three different colors and on three different shapes. All are marked “J. Palin Thorley” at the lower right edge of the design. The red print is on Thorley’s Laurel shape and marked “English Abbey” on the reverse. The blue print is on the Garland shape and is also marked “English Abbey” on the reverse. The green print is on the Fairway shape and is not marked

Detail of Thorley’s signature from the plate illustrated at the center in fig. 48.

Castle plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933– 1940. Whiteware. D. 9". Thorley’s signature appears below the Castle design on this Garland plate, although the Garland shape is not associated with Thorley.

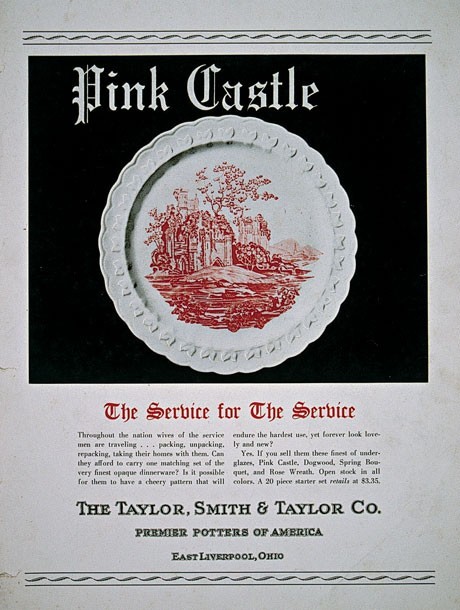

Advertisement, Pottery and Glass Salesman, June 1940, p. 3. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) This advertisement was to promote Taylor, Smith & Taylor’s Pink Castle line.

English Abbey sugar, tureen, and creamer, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933–1950. Whiteware. H. of tureen 5 1/2", sugar 4", creamer 4". Mark: “English Abbey.” (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.) These serving pieces have the Fairway form, which has not been associated with any designer.

Dogwood saucer, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1941. Whiteware. D. 6 1/4". Marks: “Taylor, Smith & Taylor, U.S.A.” within a wreath; “1941.” Vogue form. Thorley’s monochrome patterns are less common in brown.

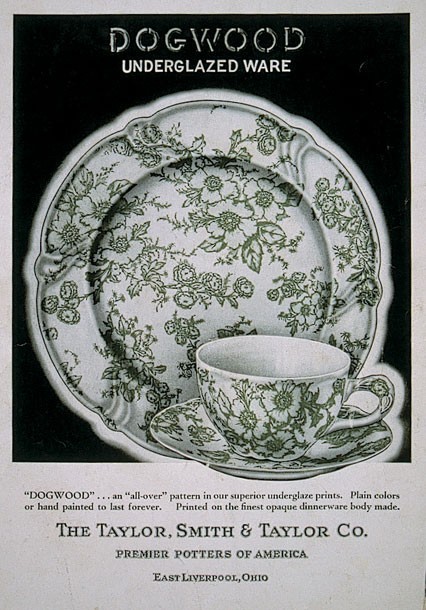

Advertisement, Pottery and Glass Salesman, June 1940, p. 3, for Taylor, Smith & Taylor’s Dogwood Underglazed Ware. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) Without this confirming ad, one might question the name, as the flowers seem to be more like primroses than dogwood flowers, which have four petals.

Dogwood dinner plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1941. Whiteware. D. 9". Marks: “Taylor, Smith & Taylor, U.S.A.” within a wreath, and “1941.” This plate is decorated with Thorley’s Dogwood decoration on his Vogue shape. (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.)

Dogwood bread-and-butter plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933–1950. Whiteware. D. 6⁄÷™". Marks: None. (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.) This plate is in the Marvel shape. Thorley’s Dogwood decoration was produced in monochrome, and, in later years, hand-colored highlights were added, giving the effect of a new pattern. Found in Thorley’s studio, this is probably a trial piece for the polychrome concept.

Dogwood bread-and-butter plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933–1950. Whiteware. D. 6⁄÷™". Marks: None. (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.) This plate is in the Marvel shape. Thorley’s Dogwood decoration was produced in monochrome, and, in later years, hand-colored highlights were added, giving the effect of a new pattern. Found in Thorley’s studio, this is probably a trial piece for the polychrome concept.

Center Bouquet dinner plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1940. Whiteware. D. 9". Marks: “Taylor, Smith & Taylor, U.S.A.” within a wreath; “1940.” This plate is decorated with Thorley’s Center Bouquet design on the Fairway shape, the designer of which has not yet been identified.

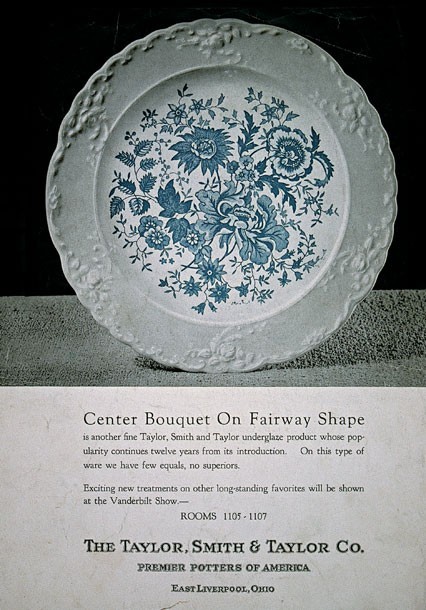

Advertisement for “Center Bouquet on Fairway Shape,” Pottery and Glass Salesman, February 1940, p. 3. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Spring Bouquet dinner plate, Taylor, Smith & Taylor, Chester, West Virginia, 1933–1950. Whiteware. D. 9". Marks: “Taylor, Smith & Taylor, U.S.A.” within a wreath; “1941.” A dinner plate in Thorley’s Spring Bouquet design (bearing his signature) and on his Laurel shape. The central transfer design on Thorley’s Spring Bouquet is identical to that on his Center Bouquet. In addition, this pattern utilizes a second transfer covering the rim. This decoration could be used only on Thorley’s Laurel shape, which is the only one without raised molded decoration on the rim.

Silk screen used by Palin Thorley in Williamsburg, ca. 1955. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) The color print would have been done in monochrome, with details, if desired, painted in by hand.

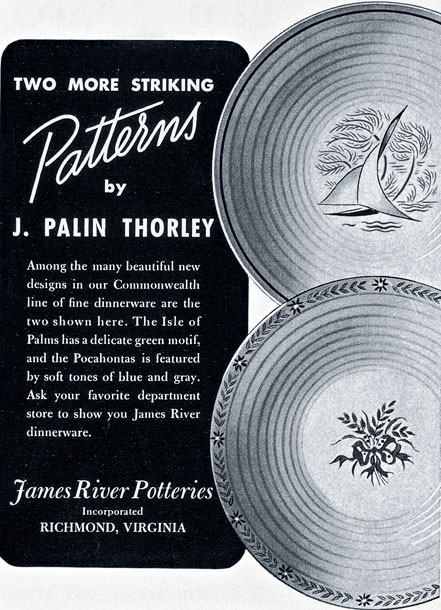

Advertisement, “Two More Striking Patterns by J. Palin Thorley, James River Potteries,” House and Garden, November 1937, p. 124. In this ad the manufacturer credits two patterns to Thorley: Isle of Palms and Pocahontas.

Jugs, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1940–1950. Whiteware. Front: H. 3 1/4". Mark: “Hall [within a circle] / MADE IN U.S.A. / 1536.” Rear: H. 5 1/2". Mark: “Hall [within a circle] / MADE IN U.S.A. / 1540.” Thorley Jugs, as they are called, were designed by Thorley and made for Hall in the 1940s. They were made in three sizes, the largest and smallest of which appear here; the middle-size jug is 5" tall and bears the number “1538.” All are the same form as the luster examples Thorley made for Colonial Williamsburg between 1938 and 1955, and appeared with many types of decoration for the rest of his active life.

Refrigerator water jug, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1935. Whiteware. H. 8 1/2". Mark: “Made Exclusively for WESTINGHOUSE By / The Hall China Co. MADE IN U.S.A.” During the 1930s Hall produced a series of ware for Westinghouse and other companies designed for use in refrigerators, a popular new appliance. In addition to water jugs, containers for “leftovers” were made in a large variety of shapes and sizes; most came in solid colors. A drawing book among the Thorley Papers illustrates what appears to be a series of these containers in forms reminiscent of those produced by Hall. In May 2000 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, presented “American Modern, 1925–1940: Design for a New Age,” an exhibition that included a related Hall/Westinghouse refrigerator water jug attributed to Thorley, which was dated to 1940.

Teapot, cup, and plate with ring for cup, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1945. Whiteware. H. of teapot 4 1/2", D. of cup 2", D. of plate 7 1/2". Marks: (teapot) “HALL CHINA / SET NO. 1 / BLUE BELL”; (cup) “HALL CHINA / SET NO. 1 / BLUE BELL / DEC.[for decoration] 80 PINK”; (plate) “HALL CHINA / SET NO. 2 / BUTTERCUP / DEC. 80 YELLOW.” The final color given as part of the mark—“PINK,” “YELLOW,” and “BLUE” (not shown)—refers to the small flowers. It is likely that these pieces were designed by Thorley because they were found in his studio attic with other examples, all of which are confirmed to have been made at potteries where he had worked and many of which are confirmed as his designs. Moreover, bills for the purchase of these and E-shape wares known to have been designed by Thorley show that these items were sold to him at a very low price (25 percent of list), whereas other pieces he purchased were sold to him at 50 percent of list price. Thorley ordered examples of these in the 1950s, presumably to sell in his shop.

Sears Roebuck catalog, fall-winter 1942–1943, p. 718.

Mount Vernon creamer and sauceboat, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1940–. Whiteware. Creamer: H. 3 1/4", L. 6"; sauceboat: H. 4 1/2", L. 9". Another E-shape design by Thorley, these pieces were sold exclusively through Sears Roebuck Co.

Coffee maker, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1942–1948. Whiteware. H. 11 1/2". This form, designed for brewing drip coffee, appeared in the Sears catalogs about ten years after Thorley designed the E-shape. Drawings for coffee makers in various forms appear in the Thorley papers. Mount Vernon was the only pattern used on the E-shape. The “coffee maker and 100 paper filters sold for $2.89” in the Sears catalog; see Margaret Whitmyer and Kenn Whitmyer, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Hall China (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 2001), p. 95.

Richmond sugar bowl, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1941–1960. Whiteware. H. 4 1/2". Often called the Black-eyed Susan pattern, this E-shape bowl was offered for sale in the Sears Roebuck catalogs.

Monticello berry bowl, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1940–. Whiteware. D. 5". Mark: Harmony House, including pattern name (Monticello) and manufacturer (Hall). This bowl illustrates the Monticello pattern and the E-shape. It is not known whether Thorley was responsible for the decoration or just the shape. The three patterns originally used on Thorley’s E-shape and offered in the Sears Roebuck catalogs of the early 1940s are Monticello, Mount Vernon (fig. 66), and Richmond (fig. 68).

Candlestick, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1940–1960. Whiteware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Clark Taggart Collection.) This form was offered by Sears to complement the E-shape dinnerware; they are illustrated together in the Sears catalogs. This unglazed and unmarked example was discovered in Thorley’s studio in 1986.

Cameo Rose teapot, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1960. Whiteware. H. 5 1/2". As with most dinner services, for which the most elaborate piece is usually the soup tureen, in a tea service the teapot generally dominates the table. Thorley’s E-shape teapot, seen here in the Cameo Rose pattern, is no exception. With its large coiling handle this is the most elegant of all the teapots made by Hall in the middle of the last century, and the pattern was sold exclusively through Jewel Tea Company from 1951 into the 1970s.

A color reproduction from a later Sears catalog—found in the Thorley Papers but without a date or page number—illustrates the same three patterns, again coupling the dinnerware with the candlestick. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Fairfax cereal bowl, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1941–1959. Whiteware. D. 7". This Fairfax example in Thorley’s E-shape is one of at least five patterns that could be purchased from Hall China by any retailer.

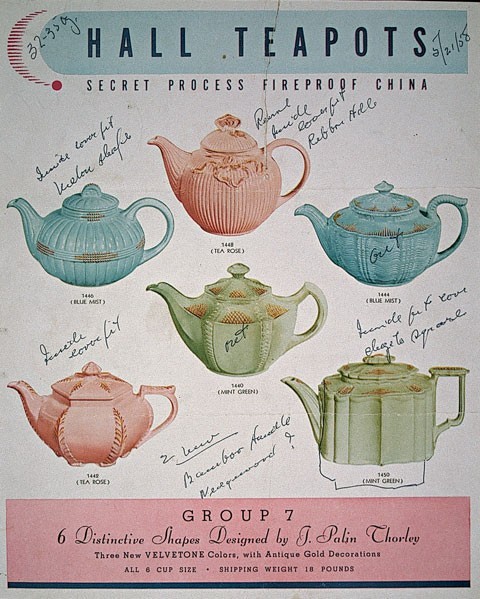

Flyer illustrating six teapots designed by Thorley that predates 1958. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.)

Teapots, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1945–1960. Whiteware. H. each 5". These two teapots were designed by Thorley, according to the flyer illustrated in fig. 74 from a series usually referred to as Victorian Style. The Plume shape is colored in Tea Rose and the Birch shape is colored in Blue Mist. A 1947 ad states that they were sold by the Jewel Tea Co. for $1.75 each (Whitmyer and Whitmyer, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Hall China, p. 202).

Teapots, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1945–1960. Whiteware. H. each 5". These two teapots were designed by Thorley, according to the flyer illustrated in fig. 74 from a series usually referred to as Victorian Style. The Plume shape is colored in Tea Rose and the Birch shape is colored in Blue Mist. A 1947 ad states that they were sold by the Jewel Tea Co. for $1.75 each (Whitmyer and Whitmyer, Collector’s Encyclopedia of Hall China, p. 202).

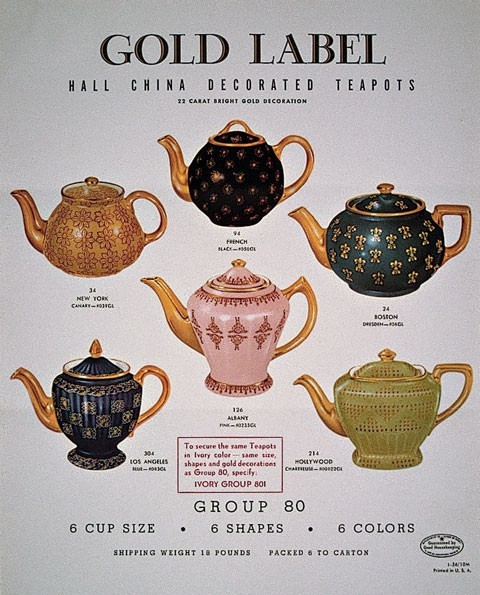

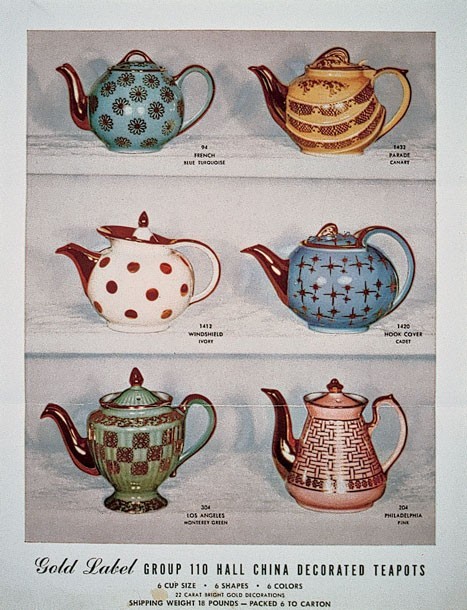

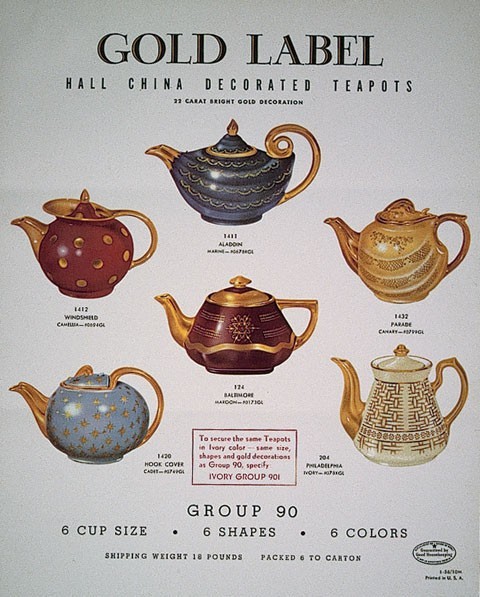

Other flyers illustrating Hall China teapots. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) The designers of these teapots are not specified, but the flyers were sent to Thorley in March 1958 along with letters and notes from Joe Thompson of Hall China Co. The center one is dated 1958; the other two are dated 1956.

Other flyers illustrating Hall China teapots. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) The designers of these teapots are not specified, but the flyers were sent to Thorley in March 1958 along with letters and notes from Joe Thompson of Hall China Co. The center one is dated 1958; the other two are dated 1956.

Other flyers illustrating Hall China teapots. (Courtesy, Thorley Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) The designers of these teapots are not specified, but the flyers were sent to Thorley in March 1958 along with letters and notes from Joe Thompson of Hall China Co. The center one is dated 1958; the other two are dated 1956.

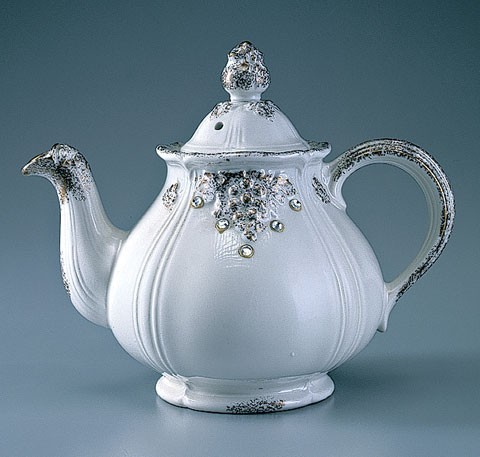

Teapot, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1960. Whiteware. H.7 1/2". This teapot has a gilded grape design that is studded with rhinestones. The inclusion of rhinestones, suggested by Joe Thompson of Hall China Co., can be found on several of Thorley’s teapot models. The bottom has several marks including “HALL” within a circle, “MADE IN U.S.A. 1528” in blue, and “HALL, 6 CUP MADE IN U.S.A. 0917” in gold.

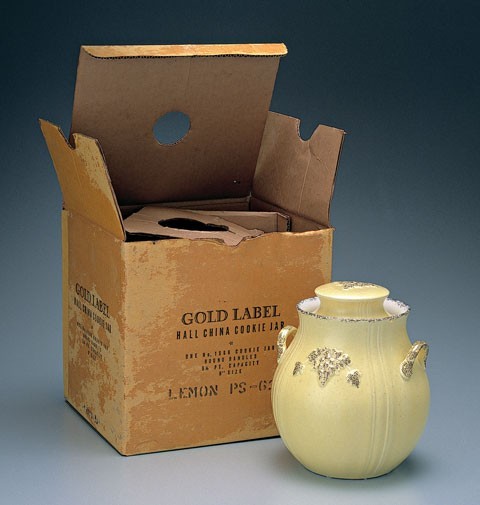

Cookie jar and mixing bowls, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1960. H. of cookie jar: 6 1/2". D. of bowls: 8 1/2," 7 1/2," and 6 1/4". These objects have Thorley’s gilded grape design, but without the rhinestones. Note the original shipping boxes. Mark on all four pieces: “HALL'S SUPERIOR QUALITY KITCHENWARE Made in U.S.A."

Cookie jar and mixing bowls, Hall China, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1960. H. of cookie jar: 6 1/2". D. of bowls: 8 1/2," 7 1/2," and 6 1/4". These objects have Thorley’s gilded grape design, but without the rhinestones. Note the original shipping boxes. Mark on all four pieces: “HALL'S SUPERIOR QUALITY KITCHENWARE Made in U.S.A.

I first met Palin Thorley about 1964. He was one of those wonderful characters who give something special to a small town, as Williamsburg then was. If one didn’t know Palin, one surely knew his beat-up old station wagon—and kept away from it when it was on the road. We met when I was digging the foundation for a church on the lot next to his studio/home on Jamestown Road. I got him talking about some fakes he had discussed with John Graham, who, as curator for Colonial Williamsburg, had acquired them in a collection of more than five hundred ceramic figures in England two years earlier.

In the later 1960s and into the 1980s I visited Palin in the evenings, and we talked about the (his) old days, mostly in England. His unhappy departure as a Colonial Williamsburg agent had festered and he had only derogatory things to say about it—us, actually, since I was a curator there. If I were silly enough to try to defend my foundation, or at least to try to soften his accusations, I would be kicked out of his house and asked never to return. The next day, of course, the phone call would come: “John, come back to see me so we can talk pots.” With the promise—never kept—that we would talk only about pots, I would return for another eventful evening. Sometimes he would tell me instead of his experiences in the trenches of France during World War I, as a British soldier fighting for his king and country. He could name each of the fallen boys from his South Staffordshire regiment; he even remembered the names of many of their loved ones, including his future sister-in-law.

Although I believe I knew it then, until I went through his papers I didn’t fully realize how important Palin Thorley was in the field of ceramic production. Many of his local friends were those who spoke his language, local archaeologists such as Norman Barka and Christine Sheridan. In 1970 Chris sat down with Palin and recorded him on more than sixteen tapes, representing seven to eight hours of reminiscences. (These, along with the one tape I recorded, in 1976, were immensely helpful in my research and are either directly or indirectly used in this article.) Other friends included those in the potting world, primarily the Mahoney family—Jimmy, his son Fred, and his nephew Charles Chrone. In 1986, when Thorley finally admitted that he could no longer manage alone, Charles took charge of his finances, got him into a retirement home nearby, and spent much time caring for him. He worked hard to make Palin’s last days comfortable and, when Palin finally died, settled his estate.

When Palin moved into the retirement home, his home-shop-pottery was cleared out and things were scattered everywhere. I gathered up any and all pieces of paper that might have some meaning and stored them in trunks, boxes, and a file cabinet, where they remained until he died, the following year. I eventually petitioned the courts and was granted his papers, which I subsequently presented to the Rare Manuscript Department of the Swem Library at the College of William and Mary. Palin’s furnishings and some of his wares were sent to New York to be auctioned at Christie’s. I was able to purchase a few items, including the signed Wedgwood plates and the two figures. I bought several hundred additional pieces at a big sale that was held shortly after he moved to the retirement home. Some things—for example the plates with unfired decoration—were given to me several years later by the Reverend David Tetrauld, a mutual friend who took on the task of organizing and managing the sale. Most of the ceramics I bought at the sale were unsold perfect, unfinished, seconds, or experimental pieces from Palin’s Williamsburg days, but I did find in the attic an important group of dishes dating from his years in England and the East Liverpool, Ohio, area. All of them were made at potteries at which Thorley had worked, either on staff or under contract. Some of these pieces I now know were designed by him; he might have designed the rest, but that cannot be confirmed.

To illustrate this paper I have borrowed objects from several collections, including those of Rol and Marline Collins, Clark Taggart, the Reverend David Tetrauld, Trudy and Tom Moyles, and the Whitehall Restaurant (formerly Thorley’s home and studio), among others. The names of the owners appear in the captions to the illustrations.

Most of the information in this paper came from the Thorley Papers, now at the Swem Library at the College of William and Mary; the sixteen tapes of interviews taken by Christine Sheridan, for which I am most grateful; information provided me by my friend Jo Cunningham, also a Thorley fan, regarding Thorley’s East Liverpool period; and from the many conversations my dear friend Palin and I had of an evening, sometimes over a glass of port, in his living room on Jamestown Road.

I’ve got to start the day I was born. It was very early. It was [a] catastrophe. It happened that day [on] King Street Hanley Stoke-on-Trent, on June 4, 1892, at six o’clock in the morning. It was about a day after that, or so mother told me, that father came into the room—and he had drawings, etchings, design for china—and told my mother, “This is the last I do for the pottery industry. From now on I’m going to paint.” He did nothing else but paint and paint. You see, at that time my father [would create the designs for] the pottery industry—made the designs for china tea ware or plates and cups and saucers . . . and everything. Then he would [transfer] them on copper-plates by etching. Normal etching burns them in acid. From the copper-plate, prints would be taken and applied to the ware, which was afterward filled in by patronesses in lovely color designs. Some of them you’ll see in the antique shops today, looking very beautiful.

In those days they had no decalcomania. [Painting] was the only way they could put decorations by hand on china. Father had been doing that. He had served his apprenticeship as a young man under his father at Ridgeway’s. His father, my grandfather, was the art director, designer, manager, technician. He made the color of the glazes at the Ridgeway Pottery, which is a very old established pottery industry in Staffordshire. My grandfather was also drawing master at what today should still exist, called The Pottery Mechanic’s Institute in the building in Pall Mall. He was the drawing master—it was the name they were known by in the early days of the eighteenth century, drawing masters—and also designer at the Ridgeway Pottery.

I spent a lot of my time in my father’s studio as a kiddie growing up. I remembered it. Oh, we had a big bronze figure there. Solid bronze, I don’t know [what] the deuce became of that, I don’t know. Antique statue in bronze standing at one end of the studio. Always a gathering of friends in there. They liked to have their pipes, some drinking scotch whiskey and soda water while father painted. I remember him painting the portrait of Dr. Charles Worth, who was the military doctor, or the local volunteer, he was a colonel in the army and he was the gentleman who brought me into the world. And told my mother it was a red-headed, healthy boy when my birthday came, the day I was born.

And so it went on then, I think [about] a lot of stories about that period, until I was nine years of age and attending school. I very much wanted to go to art school in [the] evenings. My father thought I was too young. I was upset about it. I wanted to [attend] evening classes. But under mother’s persuasion father permitted me to go to evening classes at the Hanley School of Art. I started there when I was nine. I’d leave school and instead of playing football or rowing around, I’d go home and have something to eat, and wash my hands and face nice and clean and put a clean suit on, and I would go to the Art School until 9:30. . . . [T]he teacher there was named Charles Vice, who became [a] very, very fine sculptor. His work is now eagerly sought after by antique collectors. So it went on, working hard all day and study[ing] at night.

In 1904 I sat for the British English Board of Education Government examination in freehand drawing and outline and I passed. First class. Oh, but in the papers my high school teacher only got a second, so you see I passed with the first, but I worked harder. I worked and studied every night and studied hard under some very good teachers who were teaching in the art school in the evenings. I went on like that, working hard at art school. But in the daytime, in my father’s studio, whenever he got a moment to spare in addition—Sundays, for instance—father would teach me how to make new pottery things. I wanted to make some slipped ware because at school the headmaster had taken us to the local museum—our class of youngsters, age of the youngsters about ten, eleven, and twelve—and gave us lectures for each case in the museum. We got to the slipped ware of Staffordshire, Thomas Toft of Tinker’s Clough, and I knew Tinker’s Clough because I used to play football down there. I used to go looking around the place, but I could not understand quite that slipped ware. So father thought it would be a good idea if I made a slipped dish, and he was going to teach me how to do it. So we got some clay from one of father’s pottery friends, and other advice, and I started in his studio to make a slipped dish. Well, the first one or two tries were not very successful, but after awhile I was making slipped dishes. Thomas Toft of Tinker’s Clough. I took them down to a man that father [knew], one who [said], “This one, now this is a good one, you can have this one fired. Take it to Billy Wardle.” Now Billy Wardle, who was [a] friend of my father’s—name was . . . Waldon’s Art Pottery in Shelton—and they had a big . . . plant there making slipped ware. Not that kind of slipped ware made at Tinker’s Clough, but a different kind which my grandfather had introduced years ago at Ridgeway’s. But that’s another story. So I take down this [piece to] Mr. Wardle. I knock at the office door, young lady would come. “My father wants me to show this to Mr. Wardle.” In no time Mr. Wardle came out [of] the office and [said], “Yes, we will fire it, young man,” and took it off. “You come down on Wednesday.” And when I went there on Wednesday morning following, there was my dish in all its beauty. And Billy Wardle said, “Mr. Wardle”—his father called him Billy Wardle, William Wardle, Wardle Art Pottery and Company—“it’s very good. Boy’s doing fine.” So I [took] it home. Well, it remained in the house, much in mind, much talked about in my father’s studio. One day, my father said, when I got home from school at lunchtime, he said, “You know that slipped dish?” I said, “Yeah.” “Well, I sold that today.” “You did?” “Yes, I got £5 for it.” I said, “What? £5!” That seemed liked a fortune. He said, “Yes, I sold it to Mr. Reese Jones.” Reese Jones was a partner in . . . a large department store of ladies clothing—hats and everything like that—in town. [It was] one of the largest in the city. He was a collector of china [and] pottery, like many people were, and he bought that dish. I thought it was very nice of him and I shared the £5 with my father. It was wonderful.

And [I] did some more slipped ware. . . . I was making quite a lot of Staffordshire slipped ware, cradles—anything that Thomas Toft made I would make at home. Some we gave away. Some friends still have it, as far as I know. But I do know that many years afterward that dish now reposes in a museum. The curators still know. But what happen[ed] I found [out] . . . some years afterward. . . . Mr. Reese Jones died and . . . his collection was sold at [a sale] in Stoke[-on-Trent]. That dish was sold from there. Now I’m not going to get into any controversy on this thing, but I’ll tell briefly the story for the point of it. That was purchased at Reese Jones’s death in his sale, or when his collection was sold by another famous collector of Staffordshire’s wares, where it remained in his collection maybe twenty years. That’s when it . . . [was] purchased by a museum. Because [of] the two authorities owning it, it was [assumed] by the curators [to be] a regular eighteenth-century piece. There was no deception . . . intention[al] or otherwise. It was done as an exercise in order that I could make slipware. We made some to see how it was done and enjoyed the pleasure of it. . . . I thought it was bought because he wanted to encourage that young boy to proceed to making pottery like that. And when his collection was sold, there it was. By pure assumption it was [considered] to be an eighteenth-century piece. Of course that was interesting to me because if people wanted eighteenth-century pieces, my idea at that time was, why not let them have some? I don’t care. But [to] a lot of my friends in later life I could tell this story with many a laugh, many a laugh.

When I see all the collections in the museums today—you take Whieldon ware and Astbury figures, those little factor[ie]s in the eighteenth century that made that stuff couldn’t make very very much, [they were] only little tiny places. But every museum has such a collection. They had to make millions in that factory to supply our collectors and our museums with all they had. Well, the curators have got them. They all think they’re very nice and very lovely and they are, but they are not eighteenth century. They were made relatively recently by good men and true men, but if it gives pleasure to our curators and pleasure to our museums, why not. Does it make a difference whether they were done in the eighteenth century or the twentieth or the thirtieth? It makes no difference, if they’re good works. You get a little more money for them when they [paint] the little rosy picture [on it]. This was made two hundred years ago so it must be more valuable [than] if you made the same thing yesterday. I don’t hold that, but that’s the truth of matters. I have [had] many a laugh over it. I’m laughing now. It is funny.

Thorley was born in and of the Potteries. His ancestors on both sides worked in the field. His grandfather Joseph Thorley, who started what became the Hanley School of Art, had trained at Ridgeway, and his father, John Thorley, had trained under him. Both were competent ceramic painters, which, one might assume, is why Palin was apprenticed in the painting department at Wedgwood. As you have just read, Thorley’s father became upset with the Potteries and at Palin’s birth became a full-time painter. In spite of his anti-Potteries feeling, he taught his sons the basics of designing and producing slipware before Palin had any training in either art or pottery making.

At the age of ten, in 1902, along with his academic education, Thorley started studying art at the Hanley School of Art. Two years later he won firsts in drawing and other exams. In 1906 he started his apprenticeship at Wedgwood and continued as a journeyman and assistant to John E. Goodwin, head of the painting department, until he left to fight in the war. Although Thorley was apprenticed to the painting department at Wedgwood, he was given projects that taught him to design forms for dinnerware and the technique of lithophane. He must have learned the technique of pâte sur pâte during the short period after he left Wedgwood to work for Lawrence Burke, one of the best known producers of pâte sur pâte in England. Thorley had left Wedgwood due to the strict military way Sir Cecil Wedgwood was running the factory. Sir Cecil convinced him to return, shortly before he left for war.

Thorley worked as art director at three major potteries—Simpsons, New Chelsea, and Charles Allerton and Sons—before immigrating to the United States in 1927.

Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire

Thorley’s seven-year apprenticeship in the painting department at Wedgwood started in 1906 under James Hodgkiss.

One day Mr. George Carbage came to one evening class at the Hanley School of Art. He said, “Thorley, I read a letter from the Wedgwood factory. They want to know if I could recommend one of my good students, who’s young, to go as an apprentice in the art department. The apprentice in [the] art of potting.” “Oh, yes,” said I, “I would like it.” “Well,” he said, “suppose you talk with your father.” “Yes sir,” said I. So I went home as proud as punch and happy going to work for Wedgwood. I told my father and he said, “No.” You see, my father knew the pottery industry from A to Z. He knew everyone in it, he knew their background. He’d been [in] it, my grandfathers had been in it, and all been [in] it. The outlook generally in the art part of the pottery industry was rather dismal. Everyone [tries] to get out of the pottery industry, not stay in it. I didn’t know that much at the time. But, father wanted me to [apprentice with] Mr. William Campbell, who’s an architect, a very prominent one in our city and he wanted me to go as a pupil, as an architecture pupil, office boy, when I got to start as kind of an apprentice to architecture to Mr. William Campbell. I personally didn’t have a feel for architecture at the time because I didn’t know anything about it and I had been making slipped ware. I was fascinated by ceramics, pottery. I lived in the museum, practically speaking, with Mr. Yan [a curator] day after day. All the [staff members] of the museum knew me and patted me on the head when I went in there. So, there it was. I was disappointed. But I remember mother talking to father . . . and she said, “Well, John, let him go to Wedgwood’s. It’s in the blood. All the family—yours, mine—been potters, it’s in the blood, you can’t get it out. If he has anything at all, the boy will make his way. If he has anything . . . he’ll make his way no matter where he starts. He might as well be [at] Wedgwood’s as anywhere. . . . If he has anything he will get there.” So with some reluctance, my father took me to Wedgwood and I met Mr. Goodwin in the office and I was duly engaged and I went to Wedgwood’s.

There was seven years of apprenticeship. That was the terms. The wages was two shillings and six pence per week. That was about 62 cents. Wasn’t much money. So I went first with Mr. Hotchkiss. I started to learn to paint and gild and decorate. That’s quite a story, I can tell you. And from there I advanced to become Mr. Goodwin’s assistant, but I was going three days as I went three days a week to Wedgwood because you could only go [to work] three days a week because of my scholarship. Here’s what happened. I would go to Wedgwood three days and three days at art school. So Wedgwood would give me one shilling and thruppence per week. Ah, my pay. One shilling and threepence was 31 cents a week. I used to walk two miles to the factory and two miles back home. Come home from the factory every night and then I could go to art school. I put my three days in and I couldn’t do it [in] less time because my fellow students, they were competitive. When you sat for an examination, you’ve got to keep up those or out you go, you got nowhere. I had to obey the orders of my scholarship to win the favor of [the] . . . headmaster. He would have no loafers around there. I didn’t know those words then, but that was it. I was enthusiastic and interested. I loved every moment of it. I was happy in every moment of it. What more could you ask for? I stopped all my football playing and athletic thing, running. I used to go out and run with the harriers, but then I dropped it because I couldn’t go running with the harriers on Saturday afternoon when I went to art school doing the life class instead. I used to go and draw from life when I was fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years of age from a figure. From a Mr. Yan, Mr. Light, and George Cartilage—so it went on. Occasionally I’d have exhibitions. I’d have a little something to get an exhibition. All the same things as an art student does. That went on at the Wedgwood factory.

Now I could tell a lot of interesting things about the Wedgwood factory and the apprenticeships. I was getting an enormous sum of about 30 cents a week. I was working, yes, 18 hours a day. I was serious. I was doing work which they had approved of and said nice things about. But all I got was one shilling, 25 or about 30 cents a week, and I was doing all this hard work and study to make workman better workman. I couldn’t understand that at first, but as time went on I got a little more observant and heard more from my father and others and saw the workmen at the plants and talked with the gilders and the artists and the painters and all of them. It began to dawn on me . . . Now at Wedgwood we had seventeen to twenty apprentices in the art department alone. Douglas Hall was the senior one, he was twenty-five years of age when I was fifteen. He was out of his time. But he ended up with the milk round . . . the headmaster of Stokes School of Art (that was a town in the city, part of the city, was named Woolridge). And he told me this story, that when he first took over, headmaster of the Stokes School of Art, he went across to the Minton factory, on the opposite side of the street from the art school in Stoke. He went to see Mr. Solon, who was the art director and very famous, and said to Mr. Solon, “All these boys you have as apprentices, Mr. Solon, don’t you think you should have them attend the art school in the evenings? They will never get anywhere just doing what they’re doing at the factory, and if you would have them attend the art school and fill our classes up. . . . City Art School, it would help those boys to get forward in life.” So Solon said words to the effect, “Oh, we are not concerned with that, we want this work done, let them look after themselves and push a barrel.” So Minton had all those students. And what they were painting were roses, pansies, and forget-me-nots. The boy would start in at fourteen years of age and after six months he could paint little roses, little pansies, and forget-me-nots scattered all over teacups and saucers. And all day long he painted roses, pansies, and forget-me-nots, but they didn’t encourage him to go to art school. When the boys reached twenty, if he wanted any more money they fired him, they let him go out wherever, get a job any place, which he couldn’t do because all he could do was roses, pansies, and forget-me-nots and could not do anything else for a living. I was young and observing this, and of course my father saw it too and so did others by this time.

The Theodore Roosevelt dinner service (see fig. 13) was first ordered from Wedgwood by the White House for Roosevelt’s state dinners in 1902, and all 1,296 pieces were delivered to Washington the next year.[1] In the next administration the wife of President William Howard Taft decided to use the same service and ordered an additional 360 pieces from Wedgwood in 1910.[2] It may have been the Taft service that Thorley was involved with, or perhaps replacement pieces produced between 1906 and 1908, during the last years of the Roosevelt administration. Thorley stated in an interview with Dorothy Levy that Hubert Cholerton was the crest painter for the Roosevelt service, which Wedgwood confirms,[3] but Wedgwood records do not mention the names of the other men who probably were working under him. It would seem logical that more than one decorator would be needed to paint the crests on such large orders.

When I first got to Wedgwood in 1906 or 7 they were very busy painting and doing a very beautiful service for Theodore Roosevelt. . . . They were doing this beautiful set with the White House resident’s coat of arms on it. Beautifully done. And there were men they called “crest painters” who painted the crests. I was very interested. I sat in the same workshop or the next work room with Mr. Hotchkiss, but out in the gilding department all the men were working on these White House crest plates. They were beautiful. . . . I got rather friendly with some of the men who were doing this crest painting, I persuaded them to let me have a try on a blank plate to paint a crest. After some struggles and trials and . . . a lot of tuition and kindly helpfulness on the part of the men who were painting. Well, a little later Mr. Felclift let me paint some crests for him. There I was sitting, instead of going home to art school early, I waited until Mr. Hotchkiss went home, then I would sneak back into the workshop and sit down at this desk at the bench there and with the White House crest plate, I would paint it. I would paint the White House crest on it. Then when I painted it I’d show each step to the crest painter, by whose side I was sitting, and he’d nod his head and smile and I went on working and doing the work for him and enjoying it, learning how to paint crests. . . . I heard all the stories about crest painting. It was then a dying art. The painted crests [were] fading away and there weren’t sufficient orders or people didn’t desire to pay the price of crests. But this White House order . . . was very beautiful. And it [was] all going to America.

Soho Pottery (subsequently Simpsons, Ltd.), Cobridge, Staffordshire

On his return to Wedgwood after the war, in 1918, Thorley had a conversation with Daisy Makeig-Jones, whose Fairyland Lustre is still highly collectible. She complimented him on his painting and said she hoped he would stay on. His reply was,

“Oh, Miss Jones, I am going to get out of here as soon as I can. . . . I am going to get a job as manager someplace, if I can. . . .” But a few months afterward an opportunity comes, saw it in the newspaper, somebody told me, I forget where I got it. But the Simpson Pottery Company, Soho Pottery Company were looking for a designer and decorative manager. So I applied for it and received a letter in response saying come to the Simpson Pottery Company in Cobridge, which I did and I met Mr. Simpson, the managing director. The first thing he said was I was too young—too young for [the position]—and he took all the data and [said] he would let me know. So I remember leaving his office and somewhat sadly I went on home. I didn’t think I had good news to tell Edith [Thorley’s wife]. I thought, well, I am too young perhaps . . . so this gentleman took me by the arm, Mr. Simpson [Mr. Connell] came running after me down the street when I left factory, oh about 2 or 300 yards down the street. He came running after me and said, “Mr. Thorley, come back to the office. Mr. Simpson wants you to come back again.” So Mr. Connell, the gentleman, took me to the office and I sat down with Mr. Simpson and I got the job. I got the position of art designer and decorat[ion] manager at the Simpson Pottery Company at two pounds ten shillings per week. I thought that was a very good raise. It was a step up. It’s very difficult to get a position of that kind. Mr. Simpson told me that I was the youngest man in the pottery industry ever to have a position of that responsibility of the decorat[ion] department and design. Well, I really was an unknown quantity, because I had always been at Wedgwood, most of the time. So in due course I resigned from Wedgwood and I go to the Simpson Pottery Company, the Soho Pottery Company at Cobridge. . . . There I was, although successful apparently because in 1945 Tom Simpson, who succeeded his father, met me in Pittsburgh when he was over here with the British Pottery Manufacturers Research Council on a trip to America. He said, “You know, you remember the shape you made in 1919 when you came to our factory, Simpsons?” I said, “Yes, Victory shape. I remember sitting around the table at the office with your father and the sales managers and everyone else. They thought the shape was very beautiful. What name shall we call it, what name shall we give to this shape? Someone suggested and I don’t know how it was accepted, Victory shape.” So Tom says, “Well, yes, and it’s still our biggest seller. We sell more of the Victory shape than any other shape we’ve got, Joe.” “Tom, that’s a great compliment,” I said. “[In 1919 I did] the first one . . . in my new venture as a young man just starting, and in 1945 you tell me it’s your biggest seller still. Tom, I feel very, very proud and very happy.”

New Chelsea Porcelain Company, Longton, Staffordshire

In spite of Thorley’s uncanny memory for names, it is difficult to pin down exact dates from his interviews and later correspondence. And, one must remember, he is recalling information in some cases fifty years after the events. Evidence confirms, however, that he is correct when he states, “In 1920–21 I really started going places and became designer, art director, and manager of decorations department, so forth and so on, at the New Chelsea Porcelain Company.”

He remained at New Chelsea until he went to Allerton’s, in 1924 or 1925. New Chelsea Porcelain (later China) Company produced fine bone china dinner and tea ware in Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, until 1961, when it was taken over by Grosvenor China Ltd. The names “New Chelsea” and “Chelson” were both used as part of their marks during the years Thorley was at the factory. New Chelsea marks usually, but not exclusively, incorporated an anchor, probably based on the mark used by the famous eighteenth-century Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory in London, even though there was no connection between the two potteries.

New Chelsea Porcelain produced exclusive designs for better-grade department stores such as Harrods in London, Plummers in New York, and Henwood in Johannesburg, South Africa. As their business was international, they had offices and a showroom in London, at Hatton Garden, and Thorley was there quite frequently, working with companies wishing to acquire exclusive patterns. It was on one of these trips that he read in the paper of the excavations of the tomb of Tutankhamun—an Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh (r. 1333–1323 b.c.)—which inspired a series of his designs.

Ancient Egypt always fascinated Thorley; in fact, the thought that he might be sent there contributed to his decision to join the army during World War I.

I used to hear this story from my father when I was child, how he would go to Paris and see what the ladies were wearing in their hats. What was the fashionable flower in the Parisian wear in ladies’ fashion centers? When he got back to England he would design some china tea sets with . . . whatever flower it was in style they were having in Paris, he would put them on the bone china in London and that would govern his design at that period.

With all this in mind, I’m a very young man and I’m in London . . . on business with the New Chelsea Porcelain Company. I open the paper and there is a big full-page [article] about the great discovery in Egypt. Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon had discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun and it was pictured [on] three pages in the London newspaper. I read this with great interest because I had always been interested in Egyptology . . . and when I read this . . . I decided I better make some designs for tea ware using Egyptian motifs. So when I got back to the factory up in Longton I got some cups and saucers [and] placed some designs on them using the Egyptian motifs in feelings or spirit and made them simple so that we could sell a forty-piece tea set for about $10. It had to be done in a very economical way and effective. It had to be attractive. So I used a scarab and with a very simple border with a spot of color I made, saying it myself today I remember, a very attractive design that was proved to be attractive because it became a big seller.

Charles Allerton and Sons, Longton, Staffordshire

In 1924 or 1925 Thorley moved to Charles Allerton’s pottery as director of design and a member of the board. When he arrived he discovered that the Allerton factory had never stopped producing the popular nineteenth-century pottery called luster. Although production was small, it was hand-painted by a woman, Mrs. Woolley, who had learned the art at Allerton’s in the 1840s and had continued to make it. She learned it from a woman, “Old Diana,” who had painted luster at Allertons for many years before that. Thorley tells the story:

So there are luster figures—pink luster, gold luster, copper luster, so called. It brought recollection of my early advent into the firm of Allerton, Charles Allerton, Allerton of Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, England. I became a member of the firm by invitation of Mr. Ivan Allerton and went to their old pottery in Longton. The first few days [I spent] walking around the plant, getting acquainted with different people. I came to a workshop . . . it was very old, built I’d say around 1790 or 1800, and sitting there was an elderly old lady and I walked to have a look and she was painting luster. That was the first time I’d seen luster actually being painted in the workshops; it had died out. I’ve done little bits myself at different times, of course, and knew all about it. But here was a work lady painting luster patterns. So I walked over to her to watch. She said, “Good morning sir.” I said, “Good morning. Oh, I say, you paint luster.” “Yes, sir,” said she. So I watched the dear old lady work and got into conversation with her. Her name was Mrs. Woolley. I said, “This is nice luster that you’re painting.” “Yes, sir,” said she. “Have you always painted this?” said I. “Oh yes, sir.” So I watched her work. I said, “It’s very, very nice,” and she smiled. She had a lighter face, peach complexion, gray hair I think, but she was very stout [and] was sitting on this little stool there. She overfilled the stool in all directions. You couldn’t see a stool there, so voluminous were her skirts, and there she painted. Well, we had a little conversation. I said, “How long have been here, Mrs. Woolley?” “Oh, Mr. Thorley,” she said, “I’ve been here ever since I was a little girl. . . . I came here when I was eight years of age.” “Good gracious,” said I, “eight years of age! How old are you now, Mrs. Woolley?” She said, “Eighty-six.” “Good gracious,” I said, “that’s a long while. And have you painted luster all those years?” She said, “Yes, sir,” and commenced to tell me quite an interesting story. . . . So the next day, as I pass through the workshop, I go to see Mrs. Woolley. “Good morning, Mrs. Woolley.” “Good morning, Mr. Thorley” said she. So after a little chat I said, “Mrs. Woolley, who taught you how to do the luster?” “Oh,” she said, “Old Diana taught me, Mr. Thorley, she did.” I said, “How long ago was that?” “Oh, a long while ago, a long while ago,” she said. “Old Diana died” she said. “The luster killed her.” I said, “What?” “Yes, the luster smell killed her.” “No.” “Yes,” she said. “How old was she when she died, Mrs. Woolley?” said I. “Ninety-six,” she said. . . . Here I have a direct unbroken descent of early Staffordshire luster right here at our pottery. I don’t think anyone ever thought about it like that, but I did. So I got thinking about it and [the] more thinking I did, the more thinking I did. . . . But now I was teaching two or three evenings a week at the Stoke-on-Trent Art School, mostly young ladies who were engaged in painting, decorating, and design departments of the factories. There was one little [lady] there named Minnie Moore. Minnie was very skillful and a very charming young lady, probably about 19 or 20 years of age. So I got thinking more and more and looked through the early record of the plant. I could find no records of the early patterns. We had pattern books illustrated mostly, but no luster. So I went to Mrs. Woolley and said, “Mrs. Woolley, how long have you been here, all those years? Don’t you think you should have a little time to rest a little bit and take life easier?” I’ll never forget the way she looked at me, she thought I was going to tell her to just stop working and I realized it very quickly, of course. So I said, “Mrs. Woolley, I’ll tell what I want you to do. I’m going to give you a young lady to come here, if you are agreeable to it, to help you. I like her very much. She’s one of my students at the school at the College, and if you’d like to have her with you, I’ll introduce you. If you like her, she’ll even come here to help you, brew you a little cup of tea in the afternoon, and see that you have your lunch properly and do all the little things around your workshop here, if it will help you.” The smile lit up her face and she looked at me with her eyes all smiling and so happy. I said, “So that’s what I’m going to do, if you are agreeable. And then when you have your bronchitis, I know it troubles you. She’ll even get a taxi cab for you and take you home when it gets too bad. And when it gets better, she’ll get a taxi cab and bring you back to work again and take more care of you, all the time doing the hard work for you.” “Oh, Mr. Thorley,” she said, “Oh, Mr. Thorley, you’re so good. You know, I remember Mr. Ivan [Allerton] that he came here to the factory, Mr. Ivan chairman of the board in the late seventies.”

Then she said she remembered Mr. Ernest when he came into the factory with his father. He came here, Mr. Ted—Mr. Ted was Mr. Allerton’s son, ten years my senior at that time. “I remember Mr. Ted, now you’ve come here,” she said. “I remember everyone coming here to the factory.” “Well, Mrs. Woolley, if you can remember all of that, you can remember some of those very early patterns you painted when you were a little girl that Old Diana taught you to do?” “Oh, yes, sir,” said she, and immediately the dear old lady went into rapidly describing to me ancient names for patterns, like Lady Luster, . . . each one had a name to recognize it with when they painted them. I said, “Do you think you could spend your time now remembering all those patterns and painting me cups and saucers, teapots and things?” “Oh, yes, sir,” she said. In due course I brought Miss Moore along and introduced them, started it off. Every morning at my table on my desk when I got into my office would be a teapot, a sugar, a cream pitcher, a cup, a saucer, or a plate with old paint luster pattern on it, some of them [were] beautiful and I accumulated and put them in my cupboard. Here I was by myself reviving all those old late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century luster decorations. . . . That old lady, Mrs. Woolley, I remember to this day. In a few months after that . . . I had quite a set. The luster began to be revived and in no time at all I got six or seven, half a dozen young ladies from the art college all painting luster in our shop under the management of—first one I put on—Miss Minnie Moore. I thought that was an interesting story because . . . Mrs. Woolley was living when I was there.

Thorley in the United States

Unlike his days in Staffordshire, where Thorley would either be on the staff of one company or move on to another, in America he would sometimes be the art director of one company but still do contract work for another. Thorley first worked for Sebring. While there (1927) he designed for Leigh Pottery, an affiliate of Sebring. Two years later, in 1929, he was art director for the American Chinaware Corp., and, by 1930 at the latest, he was designing for Taylor, Smith and Taylor. For the next ten to twelve years, until about 1941, Thorley was producing forms and decoration for that pottery. Yet through ads in 1937 magazines we know he was producing wares for James River Pottery; he produced the E-shape for Hall China Company in East Liverpool, Ohio, in the early 1940s; and by about 1941 he had started producing for Colonial Williamsburg. For Williamsburg, he was actually producing and not just designing the wares, as he was for the other, more commercial factories. It is also reported that he did projects for Stetson China Co., Edwin M. Knowles, and Homer Laughlin.[4]

In 1956 Thorley stopped producing for Williamsburg, but he continued to make similar forms, which he sold to gift shops and department stores in Washington, New York, and Boston, as well as out of his shop in Williamsburg. In 1958 he started designing teapots, again for Hall China Company.

During his active years in the Ohio area, Thorley received an honorary doctorate from the University of West Virginia. In 1937, at the completion of the construction of the great Art Nouveau building, the Tower of Learning, at the University of Pittsburgh, Thorley assisted in the creation of the ceramics department, which consisted of a gallery, for exhibiting a collection of antique ceramics, and a work area, which was described as “a complete pottery in miniature.” There, with kilns and other pottery equipment, Thorley instructed students in the making of pottery. In 1929 he was described as the “Internationally known ceramist and Director of the University of Pittsburgh ceramics department.”[5] He apparently held the position as director of the ceramics department for only for a few years, because in 1942 he was described in an article as “formerly Professor of Ceramics at the University of Pittsburgh.” Thorley enjoyed the “professor” title and encouraged its use.

Thorley’s most important publication was “The Potter’s Technique at Tell Beit Mirsim Particularly in Stratum A,” in Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 21–22 (1943), which he wrote with James Leon Kelso, professor of Old Testament studies at Pittsburgh-Flenia Theological Seminary. The article deals with the excavations of Tell Beit Mirsim, an area of Babylon in the sixth century b.c. Thorley discussed the techniques used in producing the ceramics; Professor Kelso discussed the history. A flyer promoting the article reads, in part, “A very important feature is the detailed study of the pottery from the technical ceramic standpoint. . . . This study will be revolutionary in its significance of our understanding of the process of manufacture in ancient Israel.”

Thorley also wrote many articles for magazines and trade journals. Among them was a twenty-seven-part series entitled “Pottery Fundamentals” published in Pottery, Glass and Brass Salesman starting in May 1938 and continuing at least to June 1941. Shortly thereafter he published a two-part article, “The Ceramic Designer in Wartime,” in Crockery and Glass Journal, in June and August 1942.