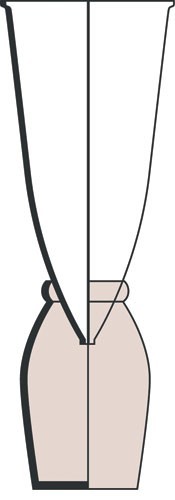

The cone-shaped mold was filled with sugar and set on a syrup jar. A white clay slip was poured over the sugar and the mold and jar were placed in a heated room. As the sugar and clay cap dried, water from the clay percolated slowly through the sugar, separating out the molasses, which dripped into the jar.

Sugar mold, Alexandria, ca. 1804–1828. Unglazed earthenware, hard sandy paste. H. 4". The tip has a 1/4-inch opening. (All objects courtesy Alexandria Archaeology; photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

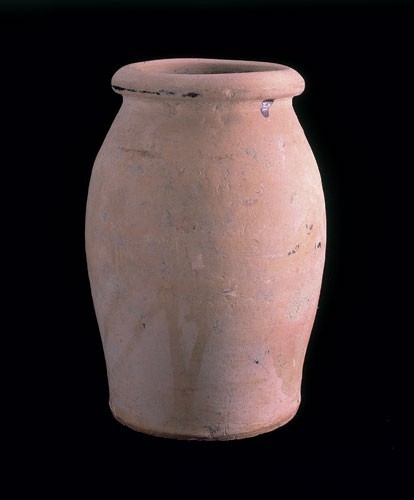

Syrup jar, probably Alexandria, ca. 1804–1828. Earthenware with lead-glazed interior. H. 8 1/2", d. of rim 4 1/2". The heavy rim, made to support the weight of the sugar mold, is a distinctive feature of jars used in sugar refining.

Sand-tempered sugar mold, Alexandria, ca. 1804–1828. Unglazed earthenware, hard sandy paste. D. of rim 7". The molds range in size from seven to twelve inches in diameter, and probably were two to three feet tall. The rim is chipped from the workers tapping it to release the sugar loaf. White clay from the claying process can be seen on the interior. The tip of a similar mold is illustrated in fig. 2.

Sugar mold, Sadirac, France, late eighteenth century. Unglazed earthenware, light-colored marbled clays. D. of tip 2 1/4", D. of rim 12". The tip has a 1-inch opening. Similar molds found in France are 24–30 inches tall.

Detail of the stamped mark “IG” from the French mold illustrated in fig. 5.

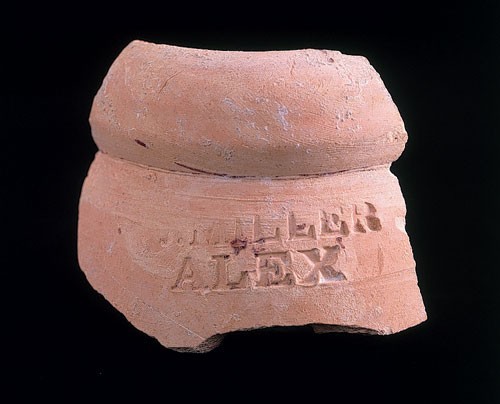

Syrup jar rim, Alexandria, ca. 1804–1828. Earthenware with lead-glazed interior. D. 4 3/4". Marked “J. MILLER, ALEX.” Fifteen marked jars were found and are similar in appearance to the thousands of unmarked jars.

Syrup jar rim, probably Alexandria, ca. 1804–1828. Earthenware with lead-glazed interior. D. 6". This form is unusual, and the jar is larger than those of the standard shape with rounded rim. Diderot’s Encyclopaedia of 1722 illustrates jars with a similar straight rim, supporting the conical sugar molds. Three of these vessels were found at the Moore-McLean Sugar House

From at least the Middle Ages until the nineteenth century the sugar refining industry used two unique forms of industrial pottery: thick-rimmed syrup jars (pots) and conical sugar molds. These distinctive forms have been found at archaeological sites in Cyprus, England (Southampton, Exeter, York, and Bristol), France (Sadirac, Rouen, and Bordeaux), the West Indies, Faneuil Hall in Boston, the Lambert-Douglas Plantation site in Trenton, New Jersey, and the Metropolitan Detention Center Site in Philadelphia. They also were used by early-nineteenth-century sugar refineries in Alexandria, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland.

Sugar refining pottery from the Alexandria and Baltimore sites recently was compared and found to be identical in appearance and clearly made by two manufactories that operated at the same time: Moore-McLean in Alexandria, 1804–1828, and Tool and Shutt, Baltimore, 1804–1829.[1]

The 1810 Census of Manufactures shows that Alexandria’s two refineries produced more sugar (800,000 pounds) than did the entire state of Maryland. But Baltimore went on to become the regional leader in sugar, with eleven refineries by 1825. Both of Alexandria’s refineries closed in the 1820s, but about 1850 Baltimore’s sugar refining industry evolved from the old method using clay molds to the vacuum pan method. The sugar refinery of Domino Sugar Corporation still dominates the skyline of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

The Refining Process

Alexandria’s sugar houses were each five to six stories high; the Tool and Shutt refinery in Baltimore was four stories high. Each had a fill house on the ground floor and drying chambers on the floors above. As described in publications of the 1830s and 1840s,[2] the refiners first boiled the sugar with lime water to help remove molasses and other impurities. They added egg white, bulls’ blood, or charcoal to the vat as a clarifying agent. This produced a scum, which rose to the surface and was removed. The liquid sugar was filtered and transferred to a copper cistern for evaporation, boiled until the right viscosity, and then transferred to a cooler, where it was stirred and agitated until it began to crystallize.

Before the cone-shaped earthenware molds were filled with sugar they were sometimes encased in wooden frames to prevent breakage during their first use, or to enable reuse of cracked molds.[3] The molds were soaked in water and the holes were plugged with twists of paper. After the sugar began to harden, “the paper plugs are removed, and a wire is passed through the hole to ensure an open channel; the moulds are then set in earthen jars . . .”[4] (fig. 1). A white clay slip (a liquid mixture of white clay and water) was poured on top of the sugar in the molds, and the molds and jars were moved to heated drying chambers on the upper floors. The molds dried for at least five days. As the clay dried, water from the clay percolated very slowly through the sugar, without dissolving it. Molasses separated from the sugar and dripped into the syrup jar. Finer grades of sugar might be clayed three times and left in the drying chambers for longer periods of time. After the sugar dried, the mold was tapped to release the cone-shaped sugar loaf. The hard clay cap was removed, any remaining discoloration at the tip was cut off, and the end of the sugar loaf was shaped with a “nosing tool.” The sugar loaf then either was reprocessed, to produce a finer sugar, or wrapped in blue paper for sale.

Characteristics of Sugar-Refining Pottery

Benjamin Silliman observed in 1833 that molds were made in Norwalk, Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey, but formerly all had been imported from England, Holland and France. He noted that English wares were “smoother, firmer and stronger than the American, but much more expensive.”[5]

In the 1980s Regaldo-Saint Blancard studied the methodology used to create the specialized molds used in the sugar industry, relying on a firsthand account from 1844, the study of archaeological materials from France, and experimental archaeology.[6] Potters used a combination of molding and turning to produce sugar molds. The potter first roughed out the form on a wheel, then put it—rim up—over a core mold or matrix attached to another wheel. After the mold was partially dried, the potter returned it to a wheel—rim down—and formed the tip. A fixed matrix, which remained stationary as the sugar mold turned against it, left telltale horizontal lines on the mold’s interior, whereas a matrix that turned along with the wheel left vertical or spiral marks close together.

Sugar molds commonly exhibit the following characteristics:

Porosity. Unglazed earthenware allowed evaporation as the sugar dried.

Hardness. Sand temper was sometimes added to the clay to increase the strength of the fabric, so that workers could tap the rim to release the loaves.

Smoothness. A smooth interior allowed the sugar loaf to be released from the mold.

Standard sizes. Conformity in the size of sugar loaves was important because of the high price of sugar. One matrix could be used to make molds of the same diameter but of different heights. Larger molds were used for lower quality sugar.

Pierced tip. The potter pierced the tip to form a hole (fig. 2); he then lengthened and turned the tip to form a knob on some larger molds. The molasses drained from the sugar through the hole in the tip.

Syrup jars (fig. 3) did not have the exacting requirements of sugar molds; they were wheel-thrown and could easily be made by local potters. They had the following characteristics:

Glaze: The earthenware jars are glazed on the interior, to hold liquid.

Rim: Most jars have a heavy, rounded rim to support the weight of the molds. Archaeological examples frequently have abrasions on the inside of the rim, from repeated insertion of the molds.

Base: Most jars have sturdy flat bases; some have multiple feet.

Size: Jars were made in varying sizes to support different molds; the size did not need to be precise.

Archaeological Finds from Alexandria and Baltimore

A visual comparison of archaeological finds from the sugar house excavations in Alexandria and Baltimore shows that both refineries used the same three types of pottery: sand-tempered sugar molds, French sugar molds, and locally produced syrup jars.

The Alexandria and Baltimore molds are of a hard, sandy fabric in a reddish color (fig. 4). Silliman noted that Long Island and New Jersey clays were mixed with sand to make a harder body. One of these was likely to have been the source for the Alexandria and Baltimore molds, but they could have been produced locally with the addition of sand temper. A preliminary study using spectrographic analysis to compare clay bodies shows the Alexandria molds to be similar in chemical composition to sherds from various Alexandria earthenware kiln sites; this study was far from conclusive, however, and no such sherds have been found at Alexandria potteries.[7]

Over ten thousand fragments of sand-tempered sugar molds were found at the site of the Moore-McLean Sugar House in Alexandria. These appear to represent between seventy-five and two hundred individual molds, in five sizes. Rim diameters ranged from six to fourteen inches.

More than seven hundred fragments of the same type of mold were found in a privy and within the foundations of Baltimore’s Tool and Shutt refinery. One sugar mold fragment still had the remains of exterior wood lathing, of the type used to support a new or cracked mold.

A few examples of large French sugar molds were found in both Alexandria and Baltimore (fig. 5). The sherds have buff and pinkish orange marbled clay with a pale pinkish orange surface. Like the more prevalent sand-tempered molds, these have horizontal striations, indicating the use of a fixed matrix. There are spiraling lines just near the tip, which was finished by hand.

A large, protruding tip found in Alexandria has a distinctive flat shape, and is marked with the impressed letters “IG” (fig. 6). A similarly marked tip, illustrated by Regaldo-Saint Blancard, was produced in Sadirac, near Bordeaux, in the second half of the eighteenth century. Sadirac was an important center for the production of sugar molds, accounting for one-third of the production of more than one hundred potters in the mid- to late eighteenth century. These supplied the sugar refineries of Bordeaux and also the overseas trade.[8] Perhaps the French molds in Alexandria and Baltimore had been acquired second hand from an earlier refinery, for a specialized purpose. Large molds like these were used to produce a less refined sugar.

The marks on examples of syrup jars from Alexandria and Baltimore indicate that they were locally produced, as was common in most sugar-refining areas. Jars with a similar profile were also made in Orléans in the nineteenth century. Similar syrup jars could have been made in Alexandria and Baltimore, as the paste and glaze of earthenware from kiln sites in these cities is similar.

With the exception of the rounded shoulders and heavy rounded rims necessary to support the weight of the molds, the jars are comparable to other local earthenware. They are wheel-thrown, with a flat bottom and a rolled rim that may be partially or fully turned. The diameter of the inside rim ranges from two to five inches. The paste ranges from light buff-orange to darker red, and the glaze from yellow to orange, olive, or brown due to variations in firing.

Out of nearly eleven thousand Alexandria jar sherds, fifteen were stamped “J. MILLER, ALEX” (fig. 7). James Miller worked in Alexandria in the early years of the nineteenth century. In 1820, he was listed in the Census of Manufacturers as a stoneware potter in Washington, D.C.

One jar from Baltimore exhibited the partial stamped mark “. . . REEN.” As this does not match the name of any known Baltimore pottery, it may be part of the address of the Tool and Shutt refinery, which was on Green (now Exeter) Street.[9]

Three large jars from the Alexandria site have straight rims (fig. 8). These are similar to syrup jars illustrated in Diderot’s Encyclopaedia of 1722. They show heavy wear from the repeated insertion of the sugar molds.

Traces of white clay could be seen on the interior of many of the sugar molds found in Alexandria, and lumps of white clay were found on the site. Benjamin Silliman, who chronicled the claying process in 1833, listed Federal Hill in Baltimore as one source of the clay.[10] Given its proximity, this clay was likely to have been used in both Baltimore and Alexandria.

Conclusion

In addition to their discovery at sugar refining sites, two large molds were found in Alexandria at the site of a late-nineteenth-century German bakery. They were used to form sugar loaves for use in a festive German holiday punch called feuerzangenbowle, still popular today. Rum is poured over the sugar loaf, which is set alight so that the burning sugar pours into the punch bowl. Thus the presence of sugar molds in areas where sugar was not refined may be an indication of ethnicity. Sugar-refining pottery is often misidentified at archaeological sites. Fragments of unglazed molds frequently are catalogued as flowerpots, and syrup jars as kitchen wares. We hope that a fuller understanding of the characteristics of sugar molds and syrup jars will lead to their recognition, and to a fuller understanding of their archaeological context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the staff and volunteers of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and former staff member Keith Barr, who excavated the site, processed thousands of artifacts, and conducted research on sugar refining. Thanks also go to Martha Williams of R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates, Inc., who provided information on the Baltimore refinery, and to Ronald Orr of the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, who provided access to the Baltimore artifacts.

Barbara H. Magid, Assistant Director, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; barbara.magid@ci.alexandria.va.us

Keith L. Barr, Pamela J. Cressey, and Barbara H. Magid, “How Sweet It Was: Alexandria’s Sugar Trade and Refining Business,” Historical Archaeology of the Chesapeake, edited by Paul A. Shackel and Barbara J. Little (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), pp. 251–65. The Moore-McLean Sugar House (44ax96) was excavated between 1987 and 1992 at Cameron and South Alfred Streets. The collection is curated by the Alexandria Archaeology Museum. Martha Williams, Nora Sheehan, and Suzanne Sanders, Phase I, II, and III Archaeological Investigations at the Juvenile Justice Center, Baltimore, Maryland (Frederick, Md.: R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates for the Maryland Department of General Services, 2000). The “Shutt and Tool, Sugar Bakers” site (18bc135) was excavated in 1998 at Hillen and Exeter Streets. The collection is curated at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory.

Benjamin Silliman, Manual on the Cultivation of the Sugar Cane and the Fabrication and Refinement of Sugar (Washington, D.C.: Printed by Francis Preston Blair, 1833); George Richardson Porter, The Nature and Properties of the Sugar Cane: With Practical Directions for the Improvement of Its Culture, and the Manufacture of Its Products (London: Smith, Elder, 1843).

Catherine M. Brooks, “Aspects of the Sugar Refining Industry from the 16th to the 18th Century,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 17 (1983): 8–9.

Charles Tomlinson, The Useful Arts and Manufactures of Great Britain (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1846). The section on sugar refining is available at www.mawer.clara.net (accessed March 29, 2005).

Silliman, Manual on the Cultivation of the Sugar Cane, p. 93.

Pierre Regaldo-Saint-Blancard, “Les Céramiques de Raffinage du Sucre: Typologie, Technologie,” Archaeologie du Midi Medieval 4 (1986): 161–65. The author cites Alexander Brogniard, Traité des Arts Céramiques, vol. 1 (Paris, 1844), 1: 543–44, for a firsthand description of the combination of molding and turning used to make the sugar molds.

Allison T. Stenger, “Spectrographic Analysis, Alexandria, Va.” (Portland, Ore.: Department of Anthropology, Ceramics Analysis Laboratory, Portland State University, 1988), pp. 1–4.

Regaldo-Saint-Blancard, “Les Céramiques de Raffinage du Sucre,” p. 156. This mold is illustrated as type 1E.

Williams et al., Phase I, II, and III Archaeological Investigations, pp. 174, 279.

Silliman, Manual on the Cultivation of the Sugar Cane, p. 92.