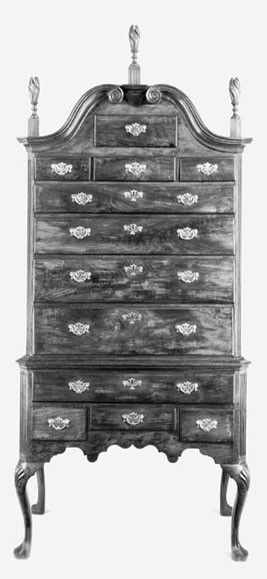

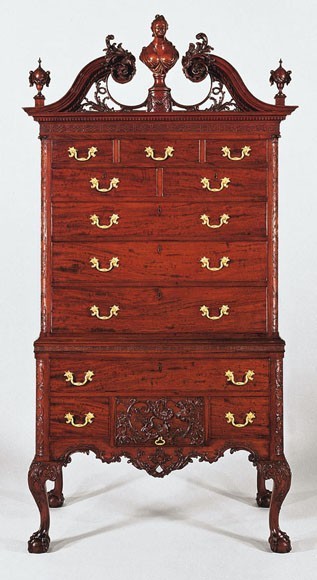

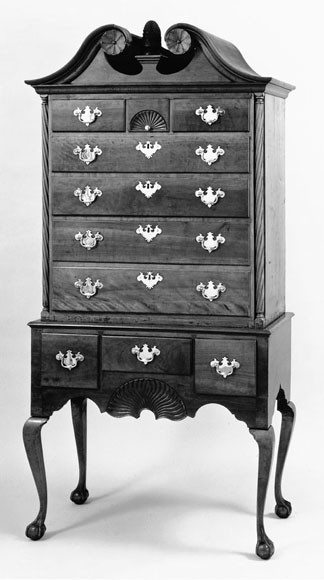

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1762–1775. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar. H. 99", W. 45 1/2", D. 25". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918, 18.110.6 All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

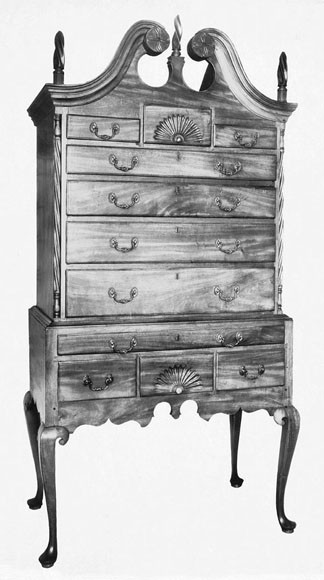

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1740–1750. Walnut with cedar and gum. H. 96 1/4", W. 43", D. 23 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Bureau with cabinet, Germany, probably Dresden, ca. 1750. Kingwood; mother-of-pearl, ivory, brass, ormolu mounts. H. 107 1/2", W. 50", D. 29 1/8". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.) www.vam.ac.uk

Slab table with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany and marble. H. 32", W. 54", D. 27". (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design, bequest of Charles L. Pendleton.) www.risd.edu

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Mme. Guimard, Paris, 1769. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Louvre Museum, Cliché des Musées Nationaux, Paris; photo, Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.)

Francois Boucher, Hercules and Omphale, Paris, ca. 1731–1734. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Pushkin Fine Art Museum, Moscow; photo, Scala/Art Resource, New York.)

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, Paris, 1767. Oil on canvas. (©By kind permission of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London)

Salon de la Princesse, Hotel de Soubise, Germain Boffrand, Paris, 1735. (Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.)

La Bastie d’Urfé, Forez, Italy, grotto 1551. (Courtesy, Dr. Naomi Miller.)

Sacra Bosco, Bormazo, Italy, ca. 1550–1570. (Courtesy, G. Putnam and Co., New York.)

Jean Mondon, Le Galand Chasseur, Paris, 1736. Engraving on paper. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harry Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930, 30.58.2(65). All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Gottlieb Leberecht Crusius, Capriccio, Germany, 1762. (Courtesy, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kunstbibliothek, Berlin; photo, Marburg/Art Resource, New York.)

Center ornament from a high chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1760–1768. Mahogany. H. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

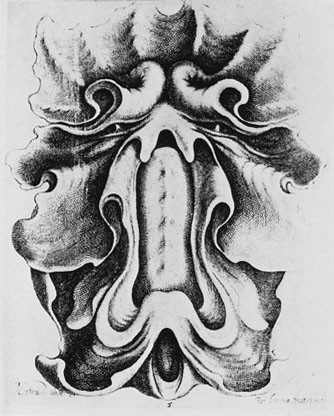

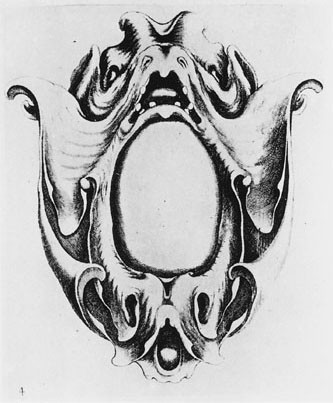

Jacobus Lutma, Festivities (from a twelve-part series), Holland, 1654. Illustrated in Rudolph Berliner and Gerhart Egger, Ornamentale Vorlagebläter (Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1981), fig. 1006.

Jacobus Lutma, Festivities (from a twelve-part series), Holland, 1654. Illustrated in Rudolph Berliner and Gerhart Egger, Ornamentale Vorlagebläter (Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1981), fig. 1005.

Adam van Vianen, tazza, Utrecht, 1618. Silver. (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

Adam van Vianen, tazza, Utrecht, 1618. Silver. (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

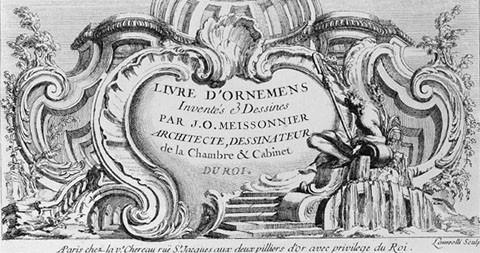

Juste-Aurèle Meissonier, title page from Livre d’Ornemens, Paris, 1734. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930, 30.58.2(136), All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

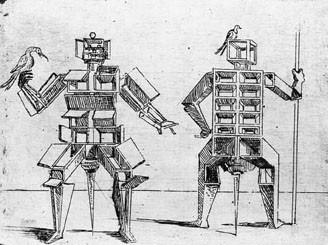

Engraving from Braccelli di varie Égure di Givovanbattista Braccelli, Livorno, Italy, 1624. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Salvador Dali, Le Cabinet Anthropomorphique, ca. 1935. Bronze. L. 24". (Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. ©2002)

André Groult, high chest of drawers, Paris, ca. 1935. H. 59", W. 27 7/16", D. 12 7/16". (Courtesy, Claude Boisgirard Auctioneer.)

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1762–1775. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 97 3/4", W. 44 1/4", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918, 18.110.60a,b. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Berea Masonic Lodge No. 114, A.F. & A.M., Gloucester, Virginia, ca. 1950.

Detail of the carving on a high chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on a high chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1763–1768. (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Detail of the carving on a dressing table, Philadelphia, 1750–1760. (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago, gift of the Antiquarian Society through the Jessie Spalding Landon Fund.)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, No. IV, 1930. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, bequest of Georgia O’Keffe.)

High chest by Henry Clifton and Thomas Carteret (cabinetmakers), Philadelphia, 1753. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 96", W. 45", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Francois Boucher, Two Nudes, Paris, ca. 1759. Black chalk drawing on paper. (©The Frick Collection, New York; photo, courtesy Colin Bailey.)

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Storming the Citadel, Paris, ca. 1771–1773. (©The Frick Collection, New York.)

William Hogarth, Analysis of Beauty, Plate I, London, 1753; reissued, ca. 1835 by James Heath. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1755–1790. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 91 3/4", W. 44 5/8", D. 24 5/8". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918, 18.110.4, All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the carving on the lower drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 32.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Trattati di archittetura ingegneria e arte militare, Italy, sixteenth century. (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Drawing based on a sketch for a pilaster base in the Medici Chapel by Michelangelo, Florence, Italy, 1519–1534. Original sketch at Casa Buonarroti, Florence.

Hughes Sambin, female term from Oeuvre de la Diversité des Termes, 1572. (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Univeristy.)

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, ca. 1755. Illustrated in Edgar G. Miller, American Antique Furniture, 2 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Lord Baltimore Press, 1937), 1:377, fig. 664.

High chest of drawers, New England, ca. 1750. (Courtesy of Sack Heritage Group.) www.sackheritagegroup.com

High chest of drawers, Preston area of Connecticut, 1770–1790. Cherry, birch, and maple with yellow poplar, chestnut, white pine, and oak. H. 82 3/4", W. 39", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Charles Willson Peale, Nancy Hallam in Cave Scene from Cymbaline, Annapolis, Maryland, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

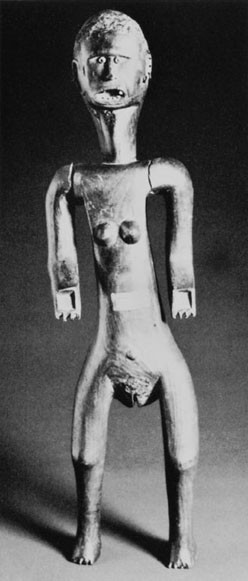

Female figure, central Tanzania, ca. 1900. (Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. ©2002).

Who will not agree with Hawthorne’s observation, that “After all, the moderns have invented nothing better in chamber furniture than those chests which stand on four slender legs, and send an absolute tower of mahogany to the ceiling, the whole terminating in a fantastically carved ornament”?

William Macpherson Horner, Jr.

Blue Book of Philadelphia Furniture

The pedimented and carved Philadelphia high chest of drawers (fig. 1) has been long celebrated as an outstanding “rococo” furniture form. Although this stylistic categorization is correct, the logic used to support it reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of key rococo principles. First, the overall form and visual weight of the Philadelphia high chest epitomize an earlier baroque aesthetic (fig. 2). Furthermore, the classically inspired architectonic facade is wholly antithetical to the more exuberant continental taste (fig. 3), and the relative decorative restraint and symmetry of the carved ornamentation is only marginally rococo. The same stylistic anachronisms characterize other Philadelphia “rococo” forms. A slab table (fig. 4), recently described as “one of the most imposing examples of Philadelphia rococo furniture,” displays a rhythmically undulating shape that unmistakably reflects a baroque rather than a rococo tradition. Whereas the ornate carving on the legs is “raffled” in the rococo manner, it nevertheless is symmetrical and baroque in inspiration. In short, analyses of Philadelphia rococo furniture overlook the original European rococo style, or genre pittoresque, with its frenzied decoration and themes of surprise, subversion, deception, and female sexuality. Guided instead by a connoisseurship that emphasizes aesthetics and an adherence to Palladian ideals, conventional analyses interpret Philadelphia rococo furniture and, in particular, the high chest in terms of the British rococo—a highly politicized artistic style that replaced the boisterous, feminized, and erotic character of the original French model with a more sedate and masculine baroque or classical facade. As a result, understanding of the Philadelphia high chest has been incomplete.[1]

To be sure, the architectonic character of the Philadelphia high chest echoes the conspicuous classicism of the British rococo, which reflected England’s desire to emulate the model of Republican Rome. Many Philadelphia high chests were produced by immigrant British cabinetmakers and carvers. These British parallels, however, represent only one part of the Philadelphia high chest story. An analysis that moves outside of existing decorative arts standards reveals a hidden facet of the Philadelphia high chest that directly links it with the continental rococo.

This essay will consider the high chest’s role as an active player in the remarkable cross-cultural drama called the continental or full rococo—a drama typically referred to as an eighteenth-century innovation, but which in fact, represents an amalgamation of many concepts rooted in antiquity, among them wild naturalism, overt sexuality, classical expression, and, most importantly, the richly symbolic grotto. By offering a new way of looking at the Philadelphia high chest, this paper reexamines and reinterprets the form’s visual vocabulary, which exists not only to adorn but also to inform. Such an approach necessarily suspends the Apollonian ideal that is the foundation of the traditional decorative arts view and instead emphasizes the need to think rococo and to recognize the style’s fantastic exploration of things Dionysian and mythological. It also emphasizes the power of metaphorical thought, a way of seeing and perceiving favored by classically educated rococo patrons but less familiar to modern observers, whose interest in the lessons of ancient mythology has given way to what Joseph Campbell calls the “news of the day” and “problems of the hour.” In sum, this new reading of the Philadelphia high chest entails moving our critical gaze away from the abstract ideal of spiritual order and toward the earth itself, where we must conceptually enter the primordial ooze in search of the grotto, the very soul of the rococo.[2]

Just what is the rococo? Typically described as an innovative style in the arts, the rococo is firmly rooted in the Enlightenment. In The Idea of Rococo, William Park asserts that even though the rococo style did not blossom in all parts of eighteenth-century Europe, the beliefs that governed and nurtured the style were everywhere:

However one regards history, the eighteenth century appears as the time of crisis, a time of extraordinary transformations, probably the most extraordinary that have ever taken place—feudal to bourgeois, classic to romantic, aristocratic to democratic, hierarchic to egalitarian, agricultural to industrial, religious to secular, from God the creator to man the creator.

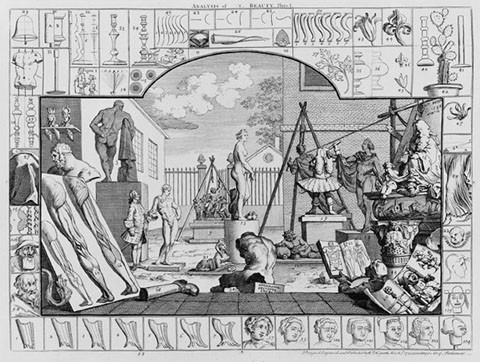

The rococo was fueled by the cultural fission of the Enlightenment, an era characterized not only by its promotion of rational thought but also by the development of sociopolitical liberalism and the public articulation of unorthodox, hedonistic, and erotic forms of expression. For instance, the free thinking spirit of the Enlightenment promoted the progressive notion that nature is inherently good, which in turn inspired the rococo and its enthusiastic exploration of sexuality, desire, and pleasure. Rococo design is a spatial analogue of this “enlightened” way of thinking, and the style’s fundamental spirit of inquiry, eroticism, and defiance is plainly expressed through its adoption of the S-scroll or serpentine line as a primary motif. The feminine and fluid S-scroll, sensually depicted in Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Mme. Guimard (fig. 5), is more than just a graceful gesture of asymmetry, more than just Hogarth’s “line of beauty.” The S-scroll opens the closed baroque C-scroll and effectively undermines the actual and implied architectonic strength of the earlier fashion. It is a brazen gesture that embodies the fundamental rococo spirit so long neglected in traditional analyses and invariably hidden beneath a veil of aesthetic jargon.[3]

A diverse range of continental expressions embody the full rococo style. For instance, rococo mythological paintings overturn preceding baroque mythological traditions. Gone are the heroic, masculine gods who symbolized the glories of Louis XIV and the French monarchy, and in their place appear gods, goddesses, and fabled figures who better express essential rococo themes. Typical of this new mythology is Francois Boucher’s Hercules and Omphale (fig. 6), which depicts a scene of great carnal intensity. In a disheveled bedchamber, the powerful Hercules passionately embraces Omphale, to whom he has been indentured for a year. Their uninhibited sexual activity, of a sort never so frankly expressed in classical texts, is all the more accentuated by the collapsing bed curtains and toppling gilt rococo table. Boucher’s overt celebration of erotic love and sexuality epitomizes the way in which rococo interpretations of mythology subvert the orthodox didacticism of the baroque style.[4]

Perhaps even more expressive of key rococo themes are continental genre paintings. Fragonard’s The Swing (fig. 7) depicts a young woman at the apex of her arc, a position brought about by the efforts of a naive cleric who pulls the swing rope. The young male courtier, who lies on the ground below the swing, gazes upon the woman’s unusually long, exposed legs. More provocatively, he also can see directly into the dark recesses of her pink, flowerlike dress, which serves as a direct allusion to her sexual anatomy. As Dore Ashton notes, the woman and her frilly dress in this rococo image represent a colorful and sexually suggestive opening reminiscent of Mallarmé’s sensual reference to the “flower that is absent from all bouquets.” Even the rake that lies in the foreground is sexually charged, referring to the French verb ratisser, “to rake,” a common eighteenth-century euphemism for coitus and illicit behavior.[5]

The rococo’s obvious allusions to female sexuality are revealed in other ways as well. Regarded as an interior decorative style, the rococo is associated with the increasing power of women as arbiters of taste. In eighteenth-century France—the ideological center of the rococo style—the self-aggrandizing vision of Louis XIV and his court yielded to the more delicate, provocative, and democratic artistic sensibilities of leading female tastemakers, most notably Madame de Pompadour and the Comtesse Du Barry, mistresses of Louis XV. The feminized nature of the full rococo also is revealed through the application of gendered terms such as “the shepherdess” to describe seating furniture forms, terms that are grammatically presented in the feminine voice. In fact, most of the words used by eighteenth-century and modern observers alike to describe the rococo style mirror those traditionally used to describe women. Examples include tender, delicate, soft, intimate, diminutive, erotic, playful, lighthearted, curvaceous, and pleasant, in addition to more obviously pejorative words such as frivolous, superficial, disordered, and dissolving. Even the basic formal motifs of the rococo refer to female sexuality and fertility. In the western cultural tradition, rocks, shells, and small woodland animals are invariably connected with “Mother Nature.” Feminine associations also emerge in the frequent rococo references to water and the fecund seasons of spring and summer. All of these deliberately covert and carefully coded symbols were readily understood by literate eighteenth-century patrons. As Mary Sheriff suggests, “part of the pleasure taken in the [rococo] erotic symbol was the pleasure of deception; the beholders who decoded these images were pleased and amused because they could clearly perceive the sexual discourse hidden from innocent eyes.”[6]

The feminized character of the rococo is perhaps most evident in its unwavering ideological allegiance to the grotto—indeed, the rococo style is the grotto style. The relationship between the grotto and the rococo is clearly seen in the fully developed rococo interior (fig. 8), which strives to emulate the wildly naturalistic interiors of garden grottoes (fig. 9). Rococo furniture, wallpaper, carpets, and other furnishings visually merge to create a unified, grotto vision. The rococo’s ideological affiliation with the grotto is further evidenced by the very word “rococo,” a pejorative term coined around the turn of the nineteenth century, well after the demise of the continental style. The word reflects the joining of two French nouns associated with the grotto: “rocaille,” the rockwork found in caves and grottoes, and “coquillage,” the shellwork used to adorn grotto walls, ceilings, and floors. As a primary source for rococo concepts and motifs, the grotto is essential to understanding the eighteenth-century continental style.[7]

More than just a cave or a hole in the ground, the grotto encompasses a wide range of emotional and intellectual experiences. Naomi Miller describes the grotto as the realm of endless contradictions, a place that, like the rococo style itself, is defined by an inherent lack of definition. The grotto provides shelter and protection, yet evokes mystery and fear. It is a site of contemplation and poetic inspiration, but also the arena of intellectual chaos; a sacred underground temple, but also the location of Bacchic orgies. Miller suggests that ultimately the grotto is best understood as “a metaphor of the cosmos,” something that can be experienced but never fully understood. The grotto and, by extension, the rococo represent places where Apollonian ideas about morality confront primal Dionysian desires and where the rational, classical mind comes unraveled.[8]

Eighteenth-century allusions to the grotto are directly linked to the Renaissance traditions of the grotesque. Inspired by the fifteenth-century unearthing of Nero’s Golden Palace in Rome and a revived interest in the ancient caves along the Adriatic coast, artists and writers alike began to combine familiar Christian messages with the newly rediscovered and often controversial ancient motifs, including the grotto. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the grotto emerged as a popular literary theme, most notably in pastoral poetry. About the same time, classically-inspired humanist gardens were built with full-scale grottoes that ranged from wildly sensual places (fig. 10), resplendent with coquillage and evocative sculpture, to more architecturally classical spaces that nevertheless retained the same chaotic grotto themes. By the seventeenth century, nature was surpassed by both art and science in these man-made grottoes, with the addition of fantastic waterworks and fountains that played music. The essential concept of the grotto, however, transcends any single time, place, or artistic style. As a “metaphor of the cosmos,” the grotto universally represents birth, sexuality, and death—themes intimately connected to the highly feminized rococo and, as we will suggest, to the Philadelphia high chest itself.[9]

The gendered character of the grotto derives from its basic form. Literally, the cave or grotto is shaped like a vagina. Both the grotto and female genitalia are traditionally depicted as sacred or secret places and sensually equated with darkness and dampness. European writers and artists, most of them men, have long alluded to the feminine and erotic aspects of the grotto. The lecherous Bacchus typically appears in a mythological grotto surrounded by a chaotic, orgiastic scene. In like manner, Ovid’s erotic and poetical landscapes are filled with suggestive references to dripping grottoes; St. Augustine’s submission to sexual temptation takes place in a grotto. Canto Four in Alexander Pope’s widely read poem Rape of the Lock (1714), a classically inspired text that nevertheless reveals many characteristic rococo attributes, describes the libidinous Cave of Spleen. Evocative grotto themes were also apparent to the amorously minded Thomas Jefferson, who in the months leading up to his marriage was inspired to design a hillside grotto at Monticello. John Keats’s romantic poem La Belle Dame Sans Merci, written in 1819, explicitly details the human sex act through metaphorical descriptions of male and female genitalia: the former described as a “pacing steed,” and the latter as an “elfin grot.” Procreative implications of the grotto include its depiction as the orifice of Mother Earth, and the act of entering the grotto is commonly equated with entering a womb. The Bible not only refers to the Grotto of the Nativity but also to other grottoes from which the earth, firmament, plants, and animals were spawned. As Miller explains, the grotto frequently is characterized as “a generative organ, the archetype of the maternal and the site of a mystery.”[10]

At the same time, the grotto and the female genitalia it metaphorically represents are associated with death or consumption. For example, the mythological Grotto of Ephesus tests the chastity of young women. If the woman who enters the grotto is not chaste, discordant sounds are heard, and she disappears, consumed by the grotto. But if musical sounds emerge, the young woman is a true virgin and escapes unharmed; in a sense, she is born again. Such characterizations of the grotto as a place of both creation and destruction reflect the ancient concept of the vagina dentata or “toothed vagina.” Rooted in the Greek idea of lamiae—lustful she-demons whose name meant both mouth and vagina—the vagina dentata embodies an ancient notion that the soul resides in both the mouth and the genitals. Several Renaissance grottoes literally depict the vagina dentata. The gaping, ogre-like figure (fig. 11) that guards the Sacra Bosco in Italy is a visual archetype of the vagina dentata; the Sacra Bosco also was called the Gate of Hell or Mouth of Hell, widely understood allegories for female genitalia. The sexual, procreative, and consumptive character of the grotto reveal it to be a highly gendered concept that is explicitly linked to the rococo.[11]

The connection between the grotto and the rococo is clearly revealed in Jean Mondon’s 1736 engraving Le Galand Chasseur, or The Gallant Hunter (fig. 12). A young woman sits next to a kneeling young hunter; her right hand suggestively grasps the barrel of the hunter’s rifle. At her feet lie the rewards of the hunt. The dog symbolizes the young man’s loyalty and amorous desire and may also refer to Circe, the sorceress in Homer’s Odyssey who had the power to tame men by turning them into subservient beasts. The hunter has one arm around the woman’s back, while the other points provocatively toward her lap, where in typical rococo fashion the light is most highly focused. Rather than dismiss his advances, the smiling woman also points to her lap. The overt sexual character of the image is further proclaimed by the grotto entrance above, which literally and figuratively alludes to the young woman. Bordered with excitedly raffled edges and emitting a torrent of water, this motif is unmistakably vaginal in character. A manifestation of midwife Jane Sharp’s 1671 description of female genitalia as “the wellspring,” this grotto entrance doubly functions as a sexual metaphor for the hunter’s impending conquest of the young woman and her ability to render the man subordinate. The overt eroticism, surprise, and female sexuality of Mondon’s illustration make it a visual manifesto of the rococo style. Its vibrancy and sensuality is all the more pronounced when contrasted with the depictions of dying nature and sexual impotency that emerged on the continent in the 1760s and 1770s, signaling the end of the rococo style. A notable example is Gottlieb Crusius’s engraving of a vacant, womblike, weed-covered grotto entrance, fronted with a flaccid phallus (fig. 13).[12]

The grotto entrance in Mondon’s engraving unmistakably reveals the original rococo meaning of the asymmetrical cartouche, perhaps the most widely recognized rococo motif and one that appears with great frequency on Philadelphia high chests (fig. 14). Stylistically, the rococo cartouche echoes seventeenth-century auricular cartouches, many of which are either graphically anatomical (fig. 15) or directly related to the vagina dentata (fig. 16). For example, a Dutch tazza or cup (fig. 17) in the auricular style is distinguished not only by its sexually suggestive, cartouche-shaped bowl but also by the actively disrobing lovers who sit on the rim. The word cartouche itself is rooted in the Italian word cartello or “little card,” which in turn implies that a cartouche literally sends a message. The message that emanates from the cartouche atop a Philadelphia high chest has nothing to do with peanuts, kidney beans, cabochons, or any of the other conventional decorative arts descriptions of the motif; rather, the rococo cartouche is a stylized grotto entrance, which serves as a metaphorical portal leading to an entirely new understanding of the style. Like the biblical serpent who tempted Adam, this seductive opening beckons the viewer to partake of the mysterious pleasures and wonders within (fig. 18). As Miller explains, “to enter [the grotto] is the significant act; for to enter is to acknowledge the distance between outside and inside, between reality and illusion, between nature and art.” The high chest cartouche attracts the viewer toward a place where conventional notions about order and morality give way to a series of chaotic dualisms that are intimately linked to the rococo: good (God) versus evil (Devil), sacred versus profane, order versus chaos, classical versus aclassical, symmetry versus asymmetry, beauty versus the sublime, Apollonian versus Dionysian, contemplation versus disorientation, comfort versus fear, and ultimately, male versus female. These dualisms—which arouse both fear and curiosity and create perceptual as well as emotional chaos—embody the fundamental appeal of the rococo style. E. H. Gombrich suggests that human delight is found on the edge of confusion, where certain truths are revealed that otherwise may not be reached by conscious effort. The radical asymmetry and grotto themes of the rococo create the same delightful confusion, and so, too, does the Philadelphia high chest of drawers.[13]

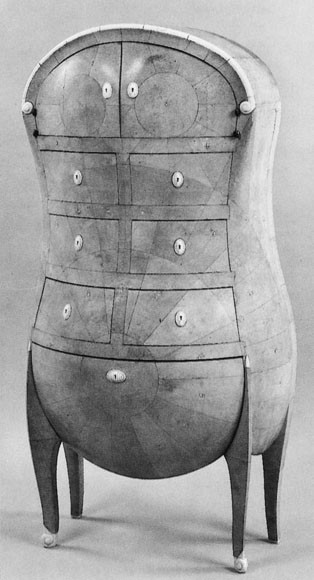

The complex, grotto-inspired character of the Philadelphia rococo high chest emerges most clearly when the form is analyzed in anthropomorphic terms. Although this strategy may appear unusual, the words used to describe the high chest suggest otherwise. The furniture term “chest” itself implies a connection to the human chest because both can be read as receptacles of essential human belongings: the human chest holds vital organs, whereas the high chest holds vital material possessions such as clothes, jewelry, and private papers. One eighteenth-century Virginia inventory meticulously details the use of the family high chest for the storage of children’s clothing. In this context, the high chest acts as a sort of nurturer or surrogate mother who provides essential family needs, a role also described by Gaston Bachelard. He noted that chests, with their diverse and ordered storage compartments, are “veritable organs of the secret psychological life” and that without them “our intimate life would lack a model of intimacy.” Other literal associations between the human form and tall chests of drawers include the innovative, early seventeenth-century drawings of Braccelli (fig. 19), as well as recent designs such as Salvador Dali’s Le Cabinet anthropomorphique (fig. 20) and a conspicuously feminized, early twentieth-century French high chest (fig. 21). Furthermore, eighteenth-century references to Philadelphia high chests, including the 1786 price list of cabinetmaker Benjamin Lehman, regularly employ anthropomorphic terms, among them “head,” “knees,” and “feet.” Modern analysts have added “toes,” “waist,” and “back,” as well as human-related terms like “skirt,” “apron,” and “bonnet.” In short, basic terminology and related figurative associations directly link the high chest to the human body.[14]

To be sure, this anthropomorphic reading of the rococo high chest radically diverges from traditional analyses and, as suggested at the start of this essay, demands a renewed appreciation for the power of metaphorical thought—the very key to understanding the rococo. The ability to think and see metaphorically characterizes most preindustrial cultures but is largely suppressed in modern society. Even highly rational and enlightened eighteenth-century culture, with all of its scientific and intellectual advancements, resounded with metaphorical thought. Birthing and mourning traditions, shared activities like dining and dancing, and private activities like bathing and sex all mirrored ancient ritualistic customs. The children of affluent eighteenth-century Europeans and Americans, for example, wore coral necklaces, not only for decorative purposes but also to keep alive an older way of warding off evil and “fascination.” The Philadelphia high chest similarly reflects an older way of seeing and perceiving. Some of its visual metaphors are easily read, whereas others are more elusive. Jules Prown suggests that the most obvious design elements on objects generally represent ideas so widely understood by makers and patrons that they are never fully explained. Less conspicuous design elements, however, often represent ideas that are not fully understood and that have been consciously or subconsciously repressed. An anthropomorphic reading of the high chest and a consideration of its subtle decorative motifs reveal an equally complex conceptual framework and further indicate the form’s fundamental rococo character. [15]

Consider a typical Philadelphia high chest (fig. 22) viewed from a distance of fifteen or twenty feet. From this perspective, the distinctive carved ornamentation starts to become secondary to the overall form; the high chest seems to lose much of its rococo character. In traditional terms, what remains is a baroque case. Something else appears as well, however. From the front, the appearance and stance of the high chest is quite human. Like us, the high chest can be seen as a bilaterally symmetrical biped with attenuated legs. The upper section of the form is reminiscent of a torso, which is demarcated from the lower section by a clearly defined waist. At the top are elements that suggest a head, with the scrolled pediment resembling rounded shoulders or flowing hair. Admittedly, these are visual parallels of the simplest sort, and similar human attributes appear on other artifacts, such as a mid-twentieth-century Virginia building (fig. 23) with a facelike facade; however, the highly symbolic and rococo character of the high chest is revealed in many other ways as well.

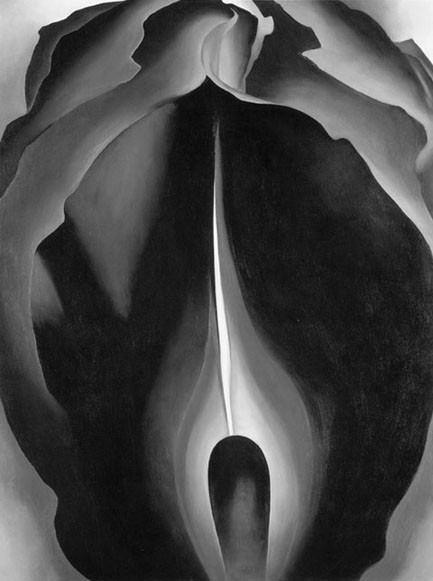

Echoing the ancient concept that the soul resides in the mouth and genitals, the carved decoration on the Philadelphia high chest is concentrated at the top and bottom, or in the head and groin. This carefully placed carving consists of flowers, shells, and foliage, all of which are common visual metaphors for sex, sexuality, and fecundity. Although some high chests have clearly delineated flowers and shells (fig. 24), many others have carved shells that are so raffled they are virtually indistinguishable from a flower (fig. 25). Like the enticing pink dress in Fragonard’s The Swing, high chest carving expresses visually and thematically the overt sexuality of the rococo style. The carved foliage on one Philadelphia dressing table (fig. 26), a form sold en suite with a matching high chest, is unmistakably vaginal in character—reminiscent not only of seventeenth-century auricular cartouches and Mondon’s dripping grotto entrance but also of more recent interpretations, like Georgia O’Keeffe’s sensual paintings of flowers (fig. 27). Both in placement and concept, the central floral motif on Philadelphia high chests emphatically announces the key rococo themes of eroticism and female sexuality.[16]

Just as symbolically charged are the carefully placed shells, which in true rococo fashion are often depicted from both the front and rear (fig. 28). This reversal simultaneously invites and excludes, reveals and conceals, and perfectly mirrors Boucher’s evocative front and rear juxtaposition of the two figures in his 1759 study, Two Nudes (fig. 29). Procreative and sexual allusions for the shell begin with the fact that many sea creatures gestate and live in shells. In western cultural traditions, the shell is associated with birth and fecundity, and its womblike quality is characterized in Bachelard’s observation that “an empty shell, like an empty nest, invites daydreams of refuge.” Furthermore, the mythological goddess Venus first emerged from a large shell, and her dolphin-driven chariot is in the form of a shell. As both the Goddess of Love and the Goddess of Lust, Venus epitomizes the essential rococo/grotto dualism between the Apollonian and Dionysian; she represents higher and more heavenly forms of love, but also baser and more earth-bound forms of sexuality. Long connected both with grottoes and erotic themes, the sexually assured Venus (fig. 30) is a primary rococo persona. Eighteenth-century terms like “delights of Venus,” “feast of Venus,” and “dance of Venus” were widely understood euphemisms for sex and sexuality. The highly influential early eighteenth-century Swedish taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus, in addition to cataloging flowers and plants in terms of human anatomy and sexual behavior, described clams—one of which he named the Venus Diane—in terms of female anatomy, from the internal “labia” and “vulva” to the adjacent “buttocks” and “anus.” A similar approach was taken by the French scientist Robinet, who graphically described the conch of Venus in terms of a woman’s vulva. Such evidence suggests that the owners of a carved, Philadelphia high chest not only confronted an anthropomorphic furniture form covered with a wide array of sensual visual metaphors but also perhaps engaged either consciously or subconsciously in an erotic tryst with Venus herself.[17]

The rococo character of the Philadelphia high chest is further revealed through its mixed sexual messages. Though most of the motifs on the high chest relate to the female body or to feminized themes, the massive size and imposing stance reflect classical and masculine attributes, which more often are associated with the forceful scale of baroque architecture and are invariably linked to British and American rococo furniture. Yet this contrast is perfectly in keeping with the playful spirit of the rococo. Even the rococo S-scroll alludes to both masculine and feminine ideals. The mid-eighteenth-century English artist and satirist William Hogarth illustrates women’s corsets and the Medici Venus to suggest the perfect S-scroll, but he also depicts the male calf muscle and the Farnese Hercules for the same purpose (fig. 31). Equally complex are rococo dances that begin with the men pursuing the women, only to reverse these roles. These dances are decidedly rococo with their wildly asymmetrical Z-shaped or S-shaped step patterns. Gender ambiguity even characterizes the letters that Philadelphia merchants wrote to one another during the late colonial period. In describing their business losses and vulnerability to risk in a credit economy, these merchants conspicuously adopted a feminine persona and spoke in feminized language. The dual sexual personae of the high chest, like eighteenth-century dances or the discourse between colonial merchants, is surprising, deceptive, subversive, and, in the end, quintessentially rococo.[18]

Admittedly, no concrete evidence has surfaced to prove that educated rococo patrons looked at the carved flowers, shells, and foliage on high chests and directly associated them with the wild themes of the rococo. On the other hand, patrons in Philadelphia or any other western cultural center did not encounter rococo objects and ideas in a void. Europeans and Americans alike participated in a rococo culture, and essential rococo themes resounded not only in the arts but also in Enlightenment literature, science, and philosophy. Texts from Pope’s Rape of the Lock (1714) to John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748) and Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1769) were openly erotic and explored the rococo concepts of reversal and transformation. The same is true of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1741) and Clarissa (1748), the former being the first novel published in America, printed in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin. The novel, a new and distinctively rococo literary form, provocatively explored libidinous themes within a domestic framework and frequently criticized the aristocracy and traditions of the royal court. In Great Britian, where the anti-monarchical Whigs were the most ardent supporters of the rococo, the novel, with its thematic focus on reversal and transformation, was played out in repeated thrusts for liberty—not only sexual liberty but also social and political liberty. In fact, the political rather than the sensual character of the rococo appears to have been the style’s primary appeal in Great Britain. Ironically, the political character of the rococo might also have been paramount in America, a liberty-seeking colony that was acutely aware of the increasing political and psychic distance between it and British governmental policy.[19]

Eighteenth-century patrons also were steadily reminded of key rococo concepts through their knowledge of classical mythology. Ovid’s Metamorphoses and works by Horace, Juvenal, and Lucretius revealed fundamental thematic linkages to the rococo; so, too, did the widely popular and overtly sexual poems attributed to the fourth-century Gaelic warrior Ossian. During the eighteenth century, a familiarity with mythology was more than just an integral part of daily intellectual life. As Jean Starobinski argues, it was “a condition of cultural literacy, essential if one wanted to enter in those conversations in which every educated man would sooner or later be invited to participate.” Certainly this condition was true in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, where Benjamin Franklin and other influential social leaders extolled the virtues of classical mythology and where surviving inventories of personal libraries and retail book vendors document the local interest in classical learning. A small number of Philadelphians—mostly orthodox Quakers—denounced the classics, whose questionable characters and themes were “shocking to every system of Morality.” Even so, supporters and opponents alike recognized the ideological parallels between classical mythology and the grotto-inspired rococo.[20]

One of the most widely recognized examples of Philadelphia furniture with a carved mythological panel is the “Madame Pompadour” high chest (fig. 32), so named because of the carved female bust that surmounts the pediment. From an anthropomorphic standpoint alone the presence of a woman’s head at the top of a high chest is highly meaningful and thoroughly in keeping with the rococo spirit of the form. Equally significant is the suggestively placed hole on the center of the skirt, a gesture that brings to mind the sexual character of the grotto entrance, the asymmetrical cartouche, and other female-associated rococo motifs. The carved image of two swans on the bottom drawer (fig. 33), inspired by a chimneypiece design in Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments (London, 1762), may relate to the mythological love story of Leda and Jupiter, or more likely to the common depiction of paired swans as an allegory of love. Here again, the traditions of classical mythology are linked to essential rococo themes.[21]

Classically educated Philadelphians also had a heightened understanding of the high chest’s architectural features, which reveal additional rococo themes. Although commonly associated with rationality, order, logic, and mathematical precision, classical architecture is rooted in traditions that are decidedly non-rational and imperfect. In The Lost Meaning of Classical Architecture, George Hersey describes the forgotten origins of classical architecture and, while doing so, uncovers much about the lost rococo character of the Philadelphia high chest. Hersey fundamentally questions why modern western cultures continue to use classical designs and concepts:

Why do architects erect columns and temple fronts derived ultimately from ancient Greek temples, when ancient Greek religion has been dead for centuries, when the temples themselves were not even buildings in the sense that they housed human activities, and when the way of life they expressed is extinct?

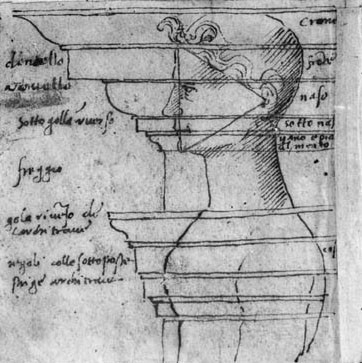

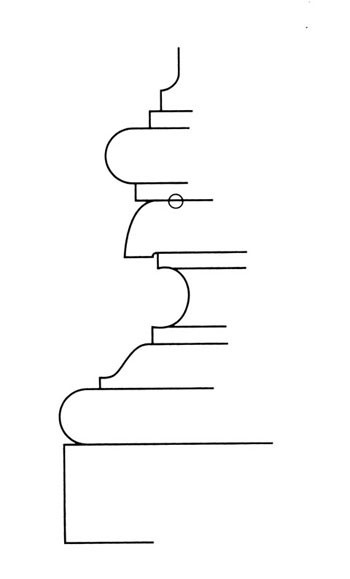

One answer is that classical architecture survives because its basic precepts remain intact. Knowingly or unknowingly, allusions to classical architecture keep alive ancient ways of seeing and perceiving. A latter-day interpretation of these ancient motifs, the Philadelphia high chest is specifically based upon the classical column. Both the high chest and the classical column are vertically oriented, tripartite compositions. The column has a base, shaft, and capital; the high chest has legs, a main case, and a pediment. The typical dimensions of a Philadelphia high chest reveal a strong understanding of classical systems of proportion. Most importantly, both the high chest and the classical column are literally connected to the human form (fig. 34) and metaphorically tied to basic rococo themes.[22]

Hersey unveils the lost rococo meaning of the classically inspired high chest through his consideration of original Greek architectural terms, many of which must be understood as tropes, or words used in a figurative sense. An example is the Greek word for foliage, which alludes not only to leafage but also to hair, specifically to the coils of hair used in sacrificial offerings. Revealingly, the foliage on the body of the Philadelphia high chest is most highly concentrated in what can be seen as the head and groin (see figs. 24–26). Other descriptive terms for specific parts on classical columns reveal additional human connections. The Greek word for the column base means both foot and footwork, the latter a reference to the dances performed at sacrificial rituals; cavetto and torus moldings on the bases of columns allude to the ropes that bound the feet of sacrificial victims; flutes signify both the bunched shafts traditionally gathered by the victorious warrior and the folds in a Grecian sacrificial gown; capital represents the Greek word for head, whereas volutes allude to both hair and sacrificial horns; dentils come from the word for teeth and recall the ornaments on sacrificial trees. The deep, shadow moldings on the bases of columns are called scotia—the Greek goddess of darkness and the underworld—and symbolize the ancient concept of darkness or shadow as not just the absence of light but as “a vapor that was dark because it was dense with the tiny mote-like souls of the dead” (fig. 35). Finally, the swelling of the classical column shaft is called entasis, a Greek word that means tension or straining and alludes to the essential human and sacrificial themes of the column (fig. 36). The highly symbolic meanings of these ancient motifs survived into the eighteenth century through the study of Greek and Latin, through the reading of classical mythology, and through the strong influence of architectural treatises by Vitruvius and others who recounted the origins of the classical orders. Because rococo patrons thought in metaphorical and mythological terms, they necessarily regarded the column as more than just a type of building support. Instead, the symbolic nature of the classical column and, by extension, the classically inspired Philadelphia high chest paralleled perceptions about the grotto and the rococo.[23]

In sum, a wide range of literal and metaphorical evidence strongly suggests that the Philadelphia high chest is more than just a stylish, eighteenth-century case furniture form. Instead, the high chest can be seen as an active rococo player whose essential rococo character is revealed through its overt sexuality, its blurred gender signals, its evocative classical allusions, and its expressed liberty from baroque, Apollonian, masculine ideals. Even the larger-than-life scale of the otherwise feminized Philadelphia high chest is perfectly in keeping with rococo ideology. Early critics of the rococo regularly denounced the style’s perversion of realistic proportions. They were offended, for example, that an ornate rococo tureen might have an accurately sized insect next to a lobster or rabbit of identical size. As with the nonhuman scale of the high chest, however, this type of variation epitomizes the subversive and contradictory spirit of the rococo. An identical strategy appears in Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a fully developed rococo text that manipulates the existing world order by contrasting the giant with the minuscule. As with Swift’s Brobdingnagian giants, the otherwise human-looking Philadelphia high chest similarly distorts reality and expresses the form’s inherent rococo nature. Like the Renaissance grotesque style from which it emerged, this rococo expression suspends conventional western patterns of belief and order and instead exists as a visual and emotional experience unburdened by dogma.[24]

Whether this alternative reading of the Philadelphia high chest expands our understanding of other American furniture forms remains to be seen. Do the provocatively placed open hearts on Delaware Valley high chests (fig. 37), for instance, suggest a parallel type of gendered object? Or do the diverse skirt designs on New England high chests indicate both male (fig. 38) and female (fig. 39) attributes? The broader understanding of rococo ideology presented in this essay additionally points toward alternative ways of reading other kinds of eighteenth-century artifacts, including some not currently thought of as rococo. Among these is Charles Willson Peale’s painting of Nancy Hallam, which depicts the actress performing a scene from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (fig. 40). Hallam is situated in front of a grotto entrance, dressed like a man to fool an unwanted courtier. Peale’s direct grotto allusion as well as his thematic focus on deception, surprise, and maybe even eroticism suggest a conscious attempt to paint in a rococo style, a designation rarely applied to eighteenth-century American painters but perhaps appropriate for Peale, William Williams, John Singleton Copley, and others. These and many other avenues of research remain open, but the anthropomorphic characteristics of the Philadelphia high chest explicitly reflect mythological, metaphorical, and cultural conditions.[25]

This essay has followed an unconventional path. Ultimately, it agrees with the traditional rococo categorization of the Philadelphia high chest, but for very different reasons. The primary difference lies in a reading of the rococo as an amalgamation of deeply rooted human concepts and as a formal and thematic expression intimately linked to earlier ways of seeing and perceiving. More than a frivolous style centered around lighthearted eroticism, and more than an ephemeral stylistic whim, the rococo represents an important manifestation of enlightened eighteenth-century thought. The rococo themes that resonate from the Philadelphia high chest may shock our post-Victorian sensibilities and our carefully crafted understanding of colonial life, which remain the ideological foundation of traditional analyses of American rococo furniture; but these themes are readily comprehensible when considered in an eighteenth-century cultural context. There, the Philadelphia high chest emerges as a mythic rococo figure—one directly connected to the ancient idea of the grotto and to the traditions of classical mythology. Much as rococo paintings communicate the innate character rather than the literal appearance of a given subject, the high chest clearly expresses its own rococo character.[26]

In the end, the symbolic importance of the high chest remains as vital today as it was two centuries ago. Joseph Campbell reminds us that modern culture retains virtually all of the essential myths and concepts of the past, and that ancient ways continue to “line the walls of our interior system of belief like shards of broken pottery in an archaeological site.” The Philadelphia high chest is one such “shard” that connects past to present and that suggests surprising parallels to other, seemingly unrelated cultural expressions (fig. 41). Certainly, the high chest has yet to reveal all of her innate mysteries.[27]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to Susan Shames and the staff at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, to the staff at the Bryn Mawr University Library, and to Jim Green of the Library Company of Philadelphia for their generous research assistance. Similar research help was provided by Martha Halpern and Jack Lindsey of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and by Luke Beckerdite of the Chipstone Foundation. Thanks also to the curatorial staff at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for their suggestions and to Albert Sack, Colin Bailey, and Naomi Miller for providing photographs. This essay was read by William Park of Sarah Lawrence College, George Hersey of Yale University, Barbara Carson of the College of William & Mary, Robert Blair St. George of the University of Pennsylvania, Graham S. Hood of Colonial Williamsburg, and Jules D. Prown of Yale University. Their thoughtful suggestions are deeply appreciated. Finally, our deepest gratitude goes to Katherine Hemple Prown of the College of William & Mary, whose technical and intellectual contributions to this work are immeasurable.

Though often thought of as a creation of the Victorian period, the term highboy, along with tall boy, can be documented in an eighteenth-century British context, most often in reference to a tall chest of drawers. The term’s use in America, and in particular in Philadelphia, is not recorded. For insight into the possible cultural and phrenological significance of the terms “highboy” and “lowboy,” see Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988). The foliated carving that adorns the tympana and drawers on many Philadelphia high chests is often associated with a rococo sense of delicacy and flow; however, this type of ornamentation is usually symmetrical and mirrors sixteenth- and seventeenth-century published designs. For examples, see Rudolf Berliner and Gerhart Egger, Ornamentale Vorlageblätter: Des 15. Bis. 19 Jahrhunderts (Leipzig: Klinkardt & Bierman, 1926). Morrison Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo: Elegance in Ornament, 1750–1775 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), pp. 191–93, fig. 129. Another well-known Philadelphia slab table (Metropolitan Museum of Art) is more in line with conventional continental rococo expression. Its rococo character is also revealed in the central carved figure on the skirt, a figure recently described by Heckscher and Bowman as a “plump-cheeked girl, indefinably oriental in character” (Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, p. 192). Though the unacknowledged prototype for the girl holding a bird, found on a pier glass design in the 1st edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Furniture and Cabinet Maker’s Director (pl. 146), does appear to be Oriental, the Philadelphia interpretation clearly depicts a Caucasian. Moreover, she is dressed in common mid-eighteenth-century theatrical garb, which this essay will argue is more in keeping with the prominent rococo use of costume as a means of attaining role reversal, deception, and surprise. Although some British objects directly reflect the continental rococo style, the vast majority reflect the tempered British taste.

For a full analysis of the metaphorical themes of The Swing, see Donald Posner, “The Swinging Women of Watteau and Fragonard,” Art Bulletin (March 1982): 75–88. Dore Ashton, Fragonard in the Universe of Painting (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988), p. 15. Mary D. Sheriff, Fragonard: Art and Eroticism (Chicago: University Press of Chicago, 1990), p. 109. This suggests alternative meanings for the English word “rake,” for example as used by William Hogarth in his widely distributed series of engravings titled The Rake’s Progress.

Geoffrey Galt Harpham, On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 23–30. Miller, Caves, pp. 7, 59. Barbara Walker, The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1983), pp. 355–57

Bailey, Loves of the Gods, pp. 422–27, pl. 50 and fig. 5. Male costumes during the Renaissance often included a codpiece in the form of a shell. Bachelard, Poetics, p. 107. Miller, Caves, p. 20. Sheriff, Fragonard, p. 190. Boucé, Sexuality, p. 9. Roy Porter, “The Secrets of Generation Display’d: Aristotle’s Masterpiece in Eighteenth-Century England,” in Unauthorized Sexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, edited by Robert P. McCubin, a special issue of Eighteenth-Century Life 9 (May 1985): 7. Stephen Jay Gould, “The Anatomy Lesson,” Natural History 104, no. 12 (December 1995): 10–15. The authors thank Michelle Erickson for calling this reference to their attention. Robinet saw this as but one of the many examples of how nature “has multiplied models of the generative organs, in view of the importance of these organs” (J. B. Robinet, Philosophical Views on the Natural Gradation of Forms of Existence, or the Attempts Made By Nature While Learning to Create Humanity [Amsterdam, 1768], cited in Bachelard, Poetics, p. 114).