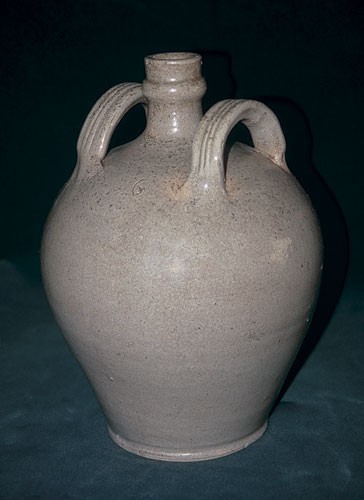

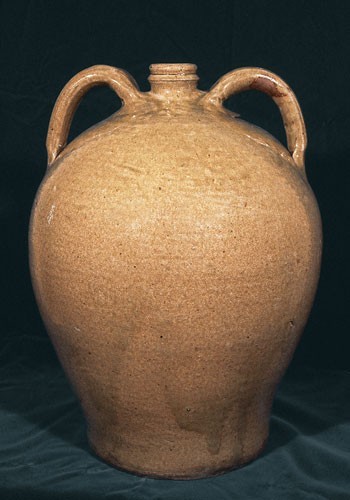

Two-handled vessel, probably American, possibly nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by author.) This small mystery vessel, which can be traced only so far as the Chicago antiques trade, shows indications of an early Southern stoneware jug (bulbous form, feldspathic alkaline glaze, foot ledge, collared neck), but the peculiar horizontal loop handles, reeded along their flat tops, depart from the vertical handle that defines a jug.

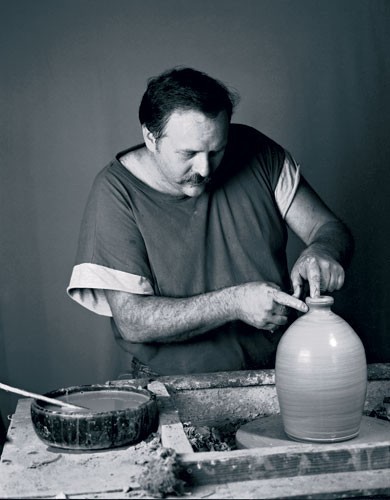

Dwayne Crocker of Gillsville, Georgia, shapes the neck of a jug on his electric wheel, 2001. (Photo, Chris Swanson.) The vertical loop handle that also defines the form will be added once the clay dries a bit.

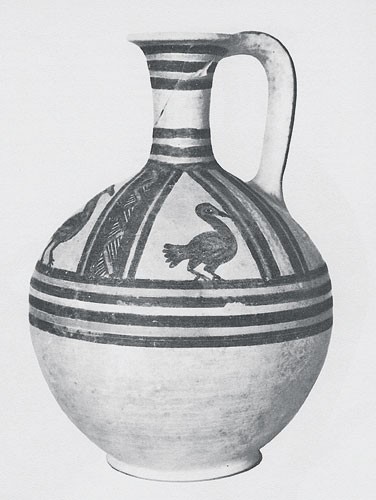

Bichrome wheel-made jug, Gaza, Plestine, ca. 1500 B.C. Earthenware. H. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem.)

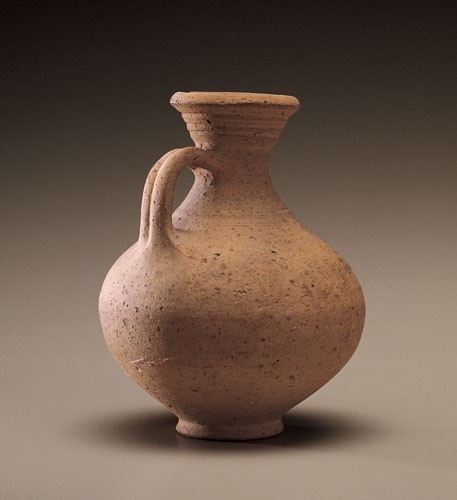

Romano-British jug, first half of second century a.d. Unglazed earthenware. H. 5 1/8". Noël Hume Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This locally made jug was recovered by a fisherman off the tidal Upchurch Marshes, Kent, England.

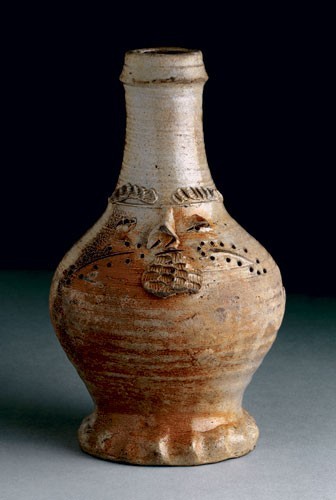

Jug, Raeren or Aachen, Germany, ca. 1475–1525. Stoneware. H. 8 3/8". (© The Trustees of The British Museum.) This salt-glazed jug has an applied face, strap handle, and thumbed base.

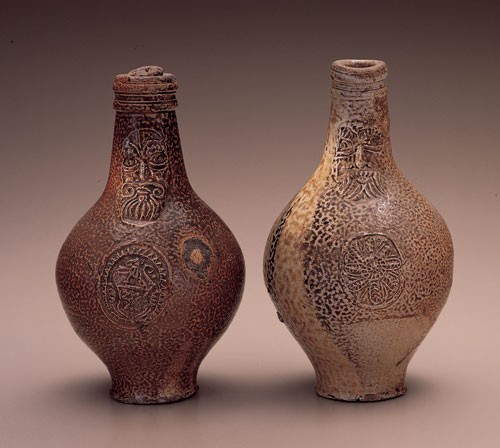

Graybeards, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1660–1665. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Noël Hume Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The vessel illustrated on the left was recovered from the Thames at London. The one on the right was found beneath the hearth of a cottage at Stratford St. Mary, Suffolk. Both were used as “witch bottles.”

The author, with a modern monument in Höhr-Grenshausen, Germany, featuring a cobalt-decorated jug atop the town arms. (Photo, Linda Carnes-McNaughton.) Such emblems of occupational identity are found throughout the Westerwald’s Kannenbäckerland (mug-baking district), where the salt-glazed stoneware tradition is still active.

Reproduction jugs, John Hudson, Mirfield, West Yorkshire, late twentieth century. Left: Claret jug, after a London delftware example. H. 6 3/4". Right: Slip-trailed owl jug after one attributed to Thomas Toft of Staffordshire, with its top beside it. H. 8 3/4". (Author’s collection.)

Jug, County Down, Northern Ireland, early to mid-1800s. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. approx. 12". (Courtesy, Museum of Country Life, Castlebar; photo, National Museum of Ireland.) Little has been published on Irish country pottery; this example of the jug form is the only one known to the author.

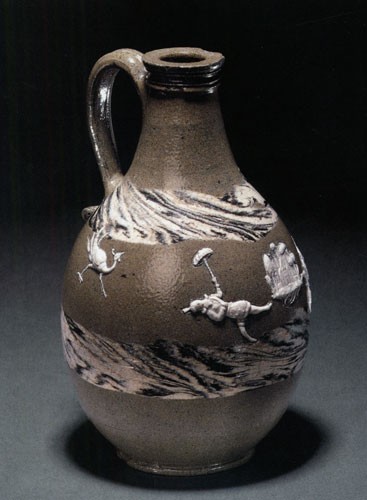

Rhenish-style jug, workshop of John Dwight, Fulham, England, last quarter of seventeenth century. Gray salt-glazed stoneware, with varicolored clay and sprig-molded figures. H. 7 1/2". (Willett Collection; © The Trustees of The British Museum.)

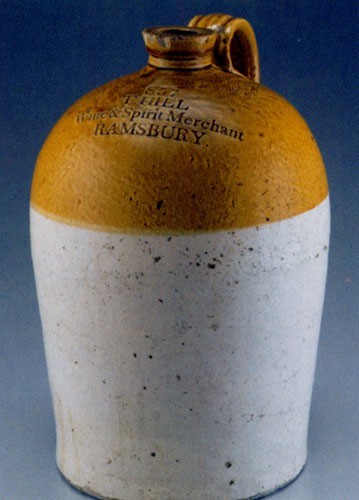

Two-tone jug, Bristol (Avon County), England, late 1800s. Stoneware, with Bristol glaze over partial iron wash. H. 15 1/2". Marks: POWELL + BRISTOL; “857 / T HILL Wine & Spirit Merchant / RAMSBURY.” (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Developed in 1835, Bristol glaze contains feldspar, whiting (as a flux), and often zinc oxide (as a whitener and opacifier). The jug was made for a merchant at Ramsbury, a village in the adjacent county of Wiltshire. The Powell of the mark probably refers to the firm of William Jr. and Septimus, descendants of William Powell, who codeveloped Bristol glaze. The firm was sold to Charles Price in 1906.

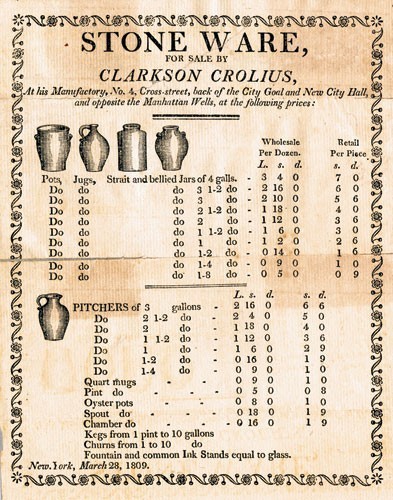

Price list of Manhattan stoneware potter Clarkson Crolius, 1809. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) Early illustrations of jugs associated with the word help establish when the American meaning came about.

Hardin E. Taliaferro (“Skitt”), Fisher’s River (North Carolina) Scenes and Characters (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1859), pp. 266–67. This image shows the American notion of a jug.

Jugs. Lead-glazed earthenware. Left: New England (Massachusetts provenance), ca. 1800. H. 7 3/4". The lead glaze is accented with copper over shoulder tooling. Right: Pennsylvania, early to mid-1800s. H. 6 1/2". Iron or manganese-colored lead glaze and extruded handle. (Author’s collection.) Both vessels have a foot-ledge and pronounced lip but are distinguished by characteristic regional handle placements.

Jugs. Manhattan. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Thomas Commereau, ca. 1815. H. 11 3/4". Right: Clarkson Crolius Jr., ca. 1840. H. 11". (Author’s collection.) Both vessels are in the Germanic tradition, with maker’s marks, handle terminals, and floral designs highlighted with cobalt blue.

Jug, attributed to Abner Landrum’s Pottersville stoneware manufactory, 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/8". Date incised under feldspathic alkaline glaze. (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank; photo, courtesy McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.) This vessel is the earliest dated Edgefield District, South Carolina, jug. Its double-collared neck became the norm for antebellum Edgefield jugs.

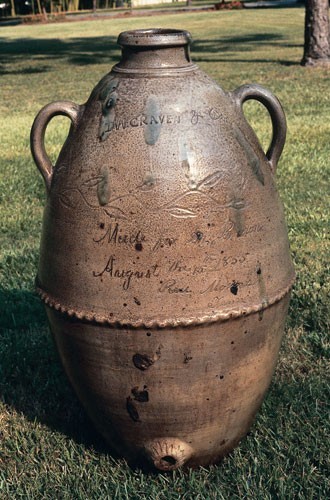

Two-handled jug, attributed to Abraham Massey, Washington County, Georgia, 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 18". Date incised under alkaline glaze. (Courtesy, Collection of Levon and Elmaise Register.) This is the earliest known dated Georgia pot. Associated with Abner and John Landrum back in South Carolina, Massey and Cyrus Cogburn introduced alkaline glazes and the Edgefield-style double-collared neck to middle Georgia.

Jugs. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Nicholas Fox, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1840. Center: retailed by Luther Funkhouser, Strasburg, Virginia, 1890s. Right: Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, Maryland, 1890s. (Ex-collection of Charles G. Zug III; photo, Charles G. Zug III.) These vessels illustrate the general shift in America from curved to straight sides.

Stoneware jug, F. M. Warrick, Sand Mountain, Alabama, 1878. H. 16". (Courtesy, Collection of Ron Countryman.) This jug bears a rare stamped date and combed decoration under the ash glaze. The moderately curved shape and incised lip are typical for the period.

Stoneware jug, Randolph County, Alabama, ca. 1900. Salt-glaze over Albany slip. H. 13 1/2". (Author’s collection.) By this time the typical American jug had become straight-sided and lost its lip.

Jugs, White County, Georgia. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Left: David Dorsey, ca. 1850. “Flint” subtype of lime glaze. H. 9 1/4". (Private collection.) Center: Cheever Meaders, 1950s. Flint glaze. H. 9 3/4". (Author’s collection.) Right: Lanier Meaders (who maintained his father’s accenting lines at shoulder), 1972. Ash glaze. H. 9 3/4". (Author’s collection.) These jugs illustrate continuity in shape at some Southern workshops. Except for their lack of a lip, ovoid Meaders jugs could be mistaken for antebellum ones.

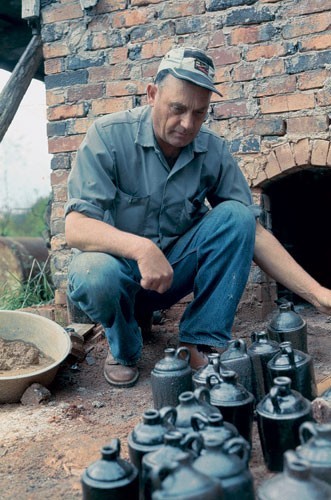

Lanier Meaders, Mossy Creek, White County, Georgia, 1974. Meaders unloads small, ash-glazed “shoulder” jugs from his wood-fueled, rectangular “tunnel” kiln. He and his father, Cheever, both made this cylindrical style of jug alongside the earlier ovoid shape.

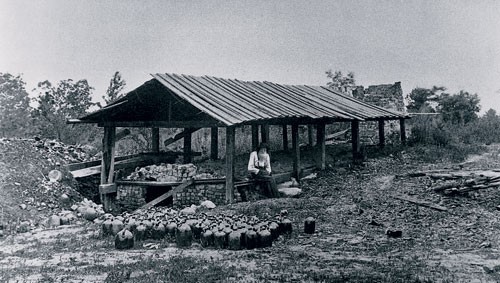

Eddie Averett’s Crawford County, Georgia, “groundhog” kiln, 1890s. (Photo, courtesy Georgia Geologic Survey.) The photograph shows whiskey jugs ready for sale to local moonshiners or licensed distilleries in nearby Macon, ranging in shape from squatty “beehive” to ovoid to cylindrical.

Moonshine still, Savannah, Georgia, ca. 1890. (Photo, William O. Wilson, Vanishing Georgia Photographic Collection, Georgia Division of Archives and History, geo139-86.) The “shoulder” jug at center, with two-tone Bristol and Albany-slip glazes, is machine-molded; the salt-glazed jugs on either side are hand-thrown.

Cider jug, Halifax, West Yorkshire, England, late 1800s. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. approx. 14 1/4". (Courtesy, Shibden Hall and Folk Museum, Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council—Museums and Arts, England.) Leaving the lower wall unglazed is said to have caused the cider to “roll,” accelerating fermentation; the hole beneath the neck held a loose stick that allowed gas to escape.

Four-gallon jug, Liverpool area, Merseyside, ca. 1830. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". When found on the East Coast such vessels frequently are misidentified as American. This example was photographed at an antiques shop in England.

Water cooler, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Stoneware. H. 31 1/4". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Purchase in honor of Audrey Shilt, President of the Members Guild, 1996–97, with funds from the Decorative Arts Endowment and Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust; photo, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.) The toasting slave couple was brushed under the alkaline glaze in iron-stained and kaolin slips within incised outlines, whereas the sow below (facing a similar pot), the handle terminals, and the leafy vine encircling the other side were painted freehand.

Water cooler, Tinsley Craven, Henderson County, Tennessee, 1855. Salt-glazed stoneware, with incised vine design and fluted joint reinforcement. H. 26 1/8". (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank.) With its wide mouth, this piece approaches fountain-type coolers but could still be considered a jug.

Syrup jug, attributed to Nathaniel Ramey pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, late 1830s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Author’s collection.) The bulbous shape of this four-gallon example is typical of these vessels.

Syrup jug, Catawba Valley, North Carolina, late 1800s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/8". (Author’s collection.) The decorative technique of placing broken bottle glass on handles and rim before firing to melt in contrasting streaks is found mainly on North Carolina stoneware. The neck was widened to facilitate pouring the cane syrup, requiring a carved wooden plug to fit it.

Buggy jug, attributed to Billy Bryant, Crawford County, Georgia, late 1800s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/4". Mark: stamped “BB” on top of handle; presentation inscription “J. E. Bryant.” (Courtesy, Museum of Southern Stoneware at River Market Antique Mall, Columbus, Ga.)

“Flower jug,” James Jones, Union County, Georgia, 1870s. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Marks: signed by the maker; inscribed “Miss L. A. Wilborn.” (Author’s collection.) A previous owner’s oral history claims that the five spouts of this mountain “wedding jug” were meant for the minister, bride, groom, best man, and maid of honor to drink from at the ceremony.

Ring jug with lion mask, Westerwald, Germany, third quarter of seventeenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt and manganese. H. 17 5/8". (Courtesy, Hetjens-Museum Düsseldorf/Deutsches Keramikmuseum, Düsseldorf, Germany.)

Ring jugs, attributed to Crawford County, Georgia, late 1800s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Museum of Southern Stoneware at River Market Antique Mall, Columbus, Ga.) Although this pair of jugs was made by the same potter, the handles on each appear to be the work of different hands.

Monkey jug, central North Carolina, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware, with melted-glass decoration and corncob stoppers. H. 12". (Courtesy, Mary Frances Berrier Collection.) According to oral history, a slave drank from one spout and his master from the other.

Monkey jug, Ekoi people, Nigeria, West Africa, probably early 1900s. Unglazed earthenware. H. 13 3/8". (© The Trustees of The British Museum.)

Botijo, Felix Perez workshop, Cuenca, Spain, mid-nineteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 14". (Author’s collection.) Made as a tourist souvenir, the monkey-jug form of this vessel is elaborated with vertical loop handles, button finials, and a sgraYto bird and foliage with copper-green highlighting.

Two-face monkey-form jug, attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. or his son Richard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1858. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank; photo, Tony Shank.) Highlighted with cobalt blue, this dated jug might represent an Americanization of the German graybeard tradition.

Face jugs, attributed to slave potters at Thomas Davies’s Palmetto Fire Brick Works, Bath, South Carolina, early 1860s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, with inset kaoline eyes and teeth. (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank.)

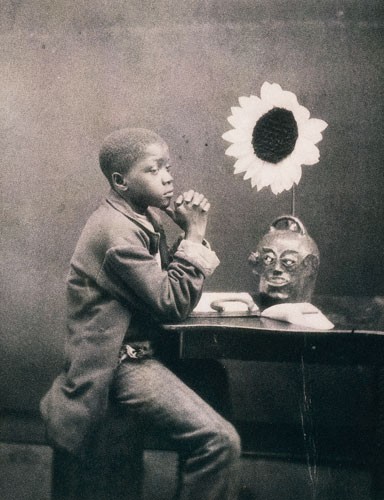

“An Aesthetic Darkey,” from a series of stereoscopic cards by photographer J. A. Palmer of Aiken, South Carolina, 1882. (Courtesy, J. Garrison Stradling.) This earliest known published image of an American face jug has a monkey form and probably was made by a local (Edgefield District) African-American potter.

Figurative jar, Mambila culture, Cameroon, twentieth century. Earthenware with polychrome decoration. H. 20". (Photo, courtesy Douglas Dawson.)

Monkey-form face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Mark: stamped “CHANDLER / MAKER.” (Private collection; photo, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.) The happy countenance on this jug contrasts with the angry ones of a decade later by slave potters in the same area.

Face jugs and wheel-thrown “wig stand,” Lanier Meaders, White County, Georgia, 1968–1974. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. (left to right) 9 3/4", 8 3/4", 9". (Author’s collection). With these items Meaders displayed his sculptural skill, creativity, and sense of humor.

Examples of modern functional jugs, made of glass and plastic rather than clay.

Fifth-generation potter Bobby Ferguson of Gillsville, Georgia, with one of his face jugs in 2004, a year before his death. An ancestor of his may have introduced face jugs to north Georgia from antebellum Edgefield District, South Carolina.

Sixth-generation potter Matthew Hewell of Gillsville, Georgia, sculpts face jugs, 1992. Lanier Meaders’s success influenced Matthew’s father, Chester, to revive the Hewell face-jug tradition.

Jugs, late twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Left: David Stuempfle. Right: Ben Owen III, Seagrove, North Carolina. (Author's collection.) Both vessels have pronounced lips, tooled decoration, and drips caused by dumping the salt directly over the pots through holes in the kiln arch, although each has a very different handle, and the jug on the left has an ash underglaze. Seagrove is a community of about one hundred shops, a dozen of which are rooted in local tradition.

On a sunny Saturday in the fall of 1997, Hewell’s Pottery in the north Georgia countryside was in the midst of its annual Turning and Burning festival, a homegrown celebration of traditional pottery-making. The guest of honor was Lanier Meaders, arguably America’s most famous folk potter, who had made it to the age of eighty. This was his big birthday party, with hundreds of well-wishers on hand. Lanier had kept alive Georgia’s old alkaline-glazed stoneware tradition virtually single-handed until others, inspired by his success, picked it up and carried it on, and our meeting many years earlier, in 1968, had inspired me to research and write the first in-depth survey of a Southern state’s ceramic heritage.[1]

The Hewell and Meaders “clay clans” of northeast Georgia (the country’s last stronghold, along with North Carolina and Alabama, of Euro-American folk pottery) have maintained ties for nearly a century. William J. Hewell of Gillsville in Hall County did much of his potting at Mossy Creek, fifteen miles to the north, in the Appalachian foothills of White County. It was there, in about 1920, that he introduced the concept of the face jug to Lanier’s father, Cheever Meaders. Hewell probably had acquired the concept from his in-laws, the Fergusons, north Georgia’s first known makers of jugs with modeled faces, who likely had brought the idea from antebellum South Carolina. When face jugs became Lanier’s specialty in the 1970s, earning him a national reputation—and the nickname “Jughead”—his young friend Chester Hewell was prompted to revive his own family’s making of them, bringing the local tradition full circle.

The county-fair atmosphere of Lanier’s birthday bash was tinged with sadness, for he was gravely ill (and would die four months later). Under the big tent the Hewells had set up for the occasion, I was asked to say a few words over the public address system about Lanier and his importance in American ceramics history, after which I fed him a slice of his birthday cake. When he clutched my sleeve from his wheelchair, indicating he had something to tell me, I leaned down to catch his barely audible whisper: “John, you’re Jughead now.” In what otherwise might have been taken as an insult he was conferring on me the honor of his nickname, knowing that soon he would have no need for it.

Belying the stereotype of the isolated country craftsman who never ventured beyond his home community, Lanier Meaders served as a U.S. Army paratrooper in World War II, returning to Mossy Creek from his air base in Britain and combat in Germany. The jug with which his career as a potter was to become inextricably bound took much the same route in its journey to America, some three centuries earlier. I have written about jugs in the context of Georgia’s ceramics history, but the Turning and Burning festival led me to ponder more broadly, as the newly anointed “Jughead,” a clay artifact type that became the quintessential American pot form—even giving rise to an American musical idiom, the jug band—and to attempt to write its life history, much as I had Lanier’s.[2]

Semantic Juggling: What’s Pot-Bellied, Skinny-Necked, One-Armed, Yet Full of Spirit?

In tracing the travels of this seemingly ubiquitous ceramic form, the first order of business is to clarify just what a jug is,[3] a task complicated by different meanings for the term in American and British English. As George Bernard Shaw wryly put it, “England and America are two countries separated by the same language.”[4] In Britain, the word jug can mean either a small pitcher (as in a cream jug for tea) or a wide-mouthed drinking vessel, which, in reference to medieval wares, is tall and often baluster-shaped (really an early tankard).[5] In the United States, however, the term has come to mean a narrow-necked (so it can be stoppered), flat-bottomed (freestanding) vessel for keeping and transporting liquids (although certainly one could drink from it), with one or two vertical loop handles for grasping and pouring (figs. 1, 2). In Britain such a vessel is called a flagon or bottle; what we Americans call a bottle normally lacks a handle. Thus, the subject of the eighteenth-century English poem “The Brown Jug” is an ale mug, whereas the American song “The Little Brown Jug” of a century later refers to a narrow-necked container for distilled spirits.[6] It is the American meaning that this essay addresses.

Peregrinating Pots: Old-World Origins and Diffusion

The jug form, as defined above, seems to have arisen in the ancient world as a response to technological advances. As practiced in the Near East by 2500 b.c., the fermentation of date and grape juice into wine and the extraction of oil from olives and aromatic and medicinal plants, along with a growing trade in these liquids, required inexpensive containers to store and transport them. At the same time the potter’s wheel, beginning as a low turntable in Mesopotamia and later improved with added flywheel and raised headblock as a kickwheel in Greece and Egypt, offered the speed to support large-scale production and facilitated the continuous drawing in and up of the jug neck.[7] The Far East experienced similar advances, but the loop handle that helps to define the jug never caught on as an addition to the bottle form favored there.

The jug first appeared in Palestine during the second phase of the Early Bronze Age, about 2800 b.c. (fig. 3), then was adopted in Greece (where it was called a lekythos), Egypt, and Persia by 1500 b.c., migrating west, with Phoenician trade, to the Etruscans and Romans.[8] The Roman Empire helped to spread the form beyond the Mediterranean into Germany and Britain, where it became part of the Romano-British ceramic repertoire (fig. 4).[9]

Some German earthenware jugs were indeed made in the Middle Ages, although published references to them are scant.[10] The form came into its own there, however, after the emergence of stoneware in the fourteenth century, perhaps to support the expanding trade in Rhenish wine.[11] German stoneware jugs were most notably manifested as the Bartmannkrug, or graybeard, with a sprig-molded face mask on the neck and medallion on the belly, thousands of which were shipped to Britain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (figs. 5, 6).[12] Salt-glazed stoneware jug production remained robust in Germany through the nineteenth century, and continues in some areas today (fig. 7).[13]

The jug form’s link to the potter’s wheel is especially evident in the ceramic history of England. When Roman withdrawal and Saxon invasion ushered in the Dark Ages, the wheel fell out of use and shaping technology reverted to hand-building, with open-mouthed forms such as cooking pots and cremation urns dominating as in the prehistoric period.[14] Reintroduction of the wheel in the seventh to twelfth centuries by later Saxons and Normans set the stage for the jug’s revival in the Middle Ages, although the form was less common than the baluster-shaped drinking vessel known to British ceramics historians as a jug.[15] Beer, the chief alcoholic beverage for ordinary medieval folk, was brewed locally and consumed as fresh as possible, hence there was little need to store and transport it. The upper class drank wine, but England’s climate was not conducive to viticulture, and most wine was imported in containers that also were made on the Continent.

Some British earthenware jugs of the Early Modern period were a domestic answer to imported German stoneware, with London delftware potters of the 1620s–1670s producing tin-glazed examples inscribed “sack,” “claret,” and “Renish [sic] wine” as potables became affordable to the growing middle class (fig. 8).[16] Country potters maintained production of lead-glazed jugs through the nineteenth century, along with other coarsewares still needed for storing and processing food and drink (fig. 9).[17] The earliest British stoneware (1640s–1670s)—made by German immigrants and John Dwight in the London area—included Rhenish-style jugs (fig. 10), whereas salt- and later Bristol-glazed stoneware jugs continued to be made in England and Scotland through the nineteenth century, eventually mass-produced in urban factories (fig. 11).[18]

The Jug Comes to America

Documentation for the colonial period, especially the first century of settlement, is too sparse to know what role jugs played in early American life. Again, semantics contribute to the problem, for early written references to jugs would have carried over the English meaning as a wide-mouthed drinking vessel. By the early nineteenth century, however, the American meaning of the word was established (figs. 12, 13).[19]

The foremost Old World influences on Euro-American ceramics were England and Germany, whose immigrant potters transplanted earthenware and stoneware traditions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. England provided precedents for the colonial redware of New England and the Tidewater South, while mid-Atlantic earthenware exhibits a mix of British and German ideas.[20] Influential settlers of these three East Coast regions can be traced to specific areas of Britain, theoretically making it possible to compare early American earthenware jugs with those of key source areas. Thus, for New England one would look to East Anglia, for the mid-Atlantic to northern England and Wales, and for the coastal South to southwest England.[21] Complicating such an approach, however, is the role London played in the settlement of all three American regions, and the difficulty in finding large enough samples of reasonably intact wares from both sides of the Atlantic that were made when influence would have been strongest.

Lura Woodside Watkins, pioneer scholar of New England ceramics, noted that “[j]ugs of redware were . . . not so common in the eighteenth century as in the years that followed.”[22] Surviving American earthenware jugs of the eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries are ovoid or turnip-shaped and often have a narrow foot extending around the base. Decoration normally was limited to incised circumferal lines (tooling) and use of a metallic oxide (copper or manganese) to color the lead glaze. As for regional distinctions, handle placement is typically lower on mid-Atlantic and Southern examples, with the upper end applied to the jug’s shoulder or shoulder-neck juncture, whereas the upper handle terminal on New England examples often was attached to the neck at or near the mouth (fig. 14).[23] This regional handle placement also applies (with exceptions, of course) to American stoneware jugs.

Salt-glazed stoneware technology was introduced to the East Coast in the early eighteenth century from both Germany and England.[24] Many of the oldest surviving American stoneware jugs have a reeded or cordoned (tooled) neck, a feature carried over from German and English stoneware. Those in the Germanic tradition have cobalt blue (or, less common, manganese purple) brushed within an incised design, around handle terminals, and highlighting a stamped maker’s mark (fig. 15); a partial iron-oxide dip created a two-tone effect for those in the English tradition.[25] Both salt- and alkaline-glazed antebellum stoneware jugs made in the South often have a pronounced lip; in the Edgefield District of South Carolina a collar was thrown around the middle of the neck as well (figs. 16, 17, 29).[26] These early neck and lip treatments apparently served both as a design element and as an aid in securing a stopper with a cord or wire.

American ceramics historians have noted a general shift in the shape of stoneware jugs from sensuous to severe that began about 1860.[27] Bulbous and ovoid jugs tended to give way to those with straighter sides (figs. 18-20), culminating in the development of a distinctly American type: the cylindrical “shouldered” or “stacker” jug, with a shoulder ledge to support a production collar so that jugs could be stacked in a column to make efficient use of kiln height.[28] This shift to less curvaceous forms sacrificed graceful proportions for greater volume, making the clay jug more competitive with factory-made glass and metal containers. The change also may reflect a decline in throwing skills as pottery manufacture became more industrialized, although in conservative, family-run shops like those of the rural South, earlier styles sometimes were maintained alongside later ones. Cheever and Lanier Meaders, for example, made both ovoid and cylindrical jugs in the mid- and late twentieth century (figs. 21, 22). Dating estimates for jugs therefore should not be based on shape alone, as each workshop had its own history of form variation.

Permutations: Form Follows Functions

The generic jugs described so far might have been used to contain any liquid, depending on the needs of the owners. Since the form’s origins, however, the emphasis has been on fermented or distilled spirits. In the United States, especially, jugs with the capacity of one quart to two gallons normally were meant for rum or whiskey, sometimes being made to order for distillers (both illicit and licensed). The medieval technology for converting grain to whiskey was brought from Ireland and Scotland in the eighteenth century and adapted to the New World grain, maize, for moonshine and bourbon.[29] As Annie Becham Long, who was born into one middle Georgia “clay clan” and married into another, put it, “Half the people in our part of Crawford County were making jugs and the other half were making liquor to put in ’em.”[30] The form’s importance in the South is underscored by the frequent occupational identification of potters as “jug makers” in the federal censuses, the nickname “Jug” being used by several potters,[31] and the name “Jugtown” identifying at least six pottery-making communities.[32] Southern potters specializing in whiskey jugs (figs. 23, 24) saw their trade decline in the early twentieth century due to Prohibition and the availability of affordable glass and metal containers. Long before that, though, the basic jug had been modified to serve a number of other, more specialized needs.

Building on the Form: Big Jugs, Squatty Jugs, Multi-Neck Jugs

It required no great leap of imagination for American potters to increase jug size to accommodate other uses, just the skill and strength to throw such “bigwares.” A capacity of five gallons was the upper limit of most potters’ normal range, but examples as large as twenty gallons are known.[33] Jugs of four and more gallons often had a second loop handle on the other side of the neck, creating a graceful, amphoralike symmetry while making them easier for two people to lift and carry when full. There are northern English precedents for such large, two-handled jugs (figs. 25, 26), but the form could have arisen independently in response to New World conditions.[34]

One use for big jugs in the United States was as a watercooler or cistern before indoor plumbing, typically with a spigot hole in the lower wall (figs. 27, 28). Decorated examples might also have been used in taverns as beer, wine, or punch dispensers, since nonporous stoneware would have been more sanitary (easier to clean) than wooden kegs.[35] In the antebellum South, sugar, in the form of solid cones, was affordable mainly to the upper class and, as a precious commodity, was locked in an item of furniture known as a sugar chest.[36] Ordinary folk used honey and cane syrup as their chief sweetenings, making syrup jugs of three or more gallons a mainstay of the Southern potter’s repertoire (figs. 17, 29, 30).[37] Kept in the kitchen or nearby smokehouse, the syrup would be handy for cooking or table use. Some potters widened the mouth to facilitate pouring the thick liquid, but this required the owner to fabricate a wooden plug, as the usual corncob stopper would not have made a tight fit.

Another approach to adapting the basic form to specialized uses was to compress it, creating a jug with a low center of gravity. In the late nineteenth century the Norton Pottery of Bennington, Vermont, produced squatty molasses jugs glazed with Albany slip, adding a well-like drip-catcher lip with a pinched pour-spout.[38] Southern potters made even squatter “buggy jugs” (proportionately, the top half or third of a regular jug), which were designed to keep that special stock of “antifreeze” from tipping over on a bumpy buggy or wagon drive (fig. 31).

Localized to northern Georgia and North Carolina’s Catawba Valley, alkaline-glazed “flower jugs” (for displaying cut flowers) elaborated the basic jug form by adding necks (usually four, separately thrown “off the hump”) around the central one.[39] Made as presentation pieces—an inscribed Georgia mountain example has an oral history as a “wedding jug” (fig. 32)—in the mid- to late 1800s and revived by folk potters a century later, they seem related to English and Dutch quintals that were based on a vase type introduced to Europe from Persia along with the tulip in the 1600s. Old World examples, however, lack the loop handle that helps to define a jug.

Further Mutations: Water Jugs for the Field

Two types of “harvest jugs” are known in the United States, each with different Old World roots. Although occasionally made in the North, their concentration in the South can be attributed to the region’s agrarian economy and warm climate; hours of field work in the heat of the day could produce a powerful thirst. Unlike the jug types discussed above, these designs involved major alteration of the basic form.

The ring jug, built from a hollow ring, is a European form that can be traced to ancient Greece[40] but its inspiration in America most likely was the German stoneware tradition (fig. 33).[41] Its wheel-thrown production is something of a potter’s secret: starting with a clay disk, the potter scoops out the center with a rib, leaving a solid ring. A trough is created by pulling up the outer and inner edges, which are then curved toward each other and joined.[42] After cutting the circular tube off the wheel and drying to leather hard, the flat (headblock) side is trimmed to the round and a separately thrown neck is attached over a hole cut in the arch. It is at this stage that the potter has the option of creating a jug or a bottle; if the former, one or two loop handles, and a thrown or solid-block base, are added (fig. 34).

A functional explanation for the donut shape is that it could lie flat for easier transport. The center hole allowed placement on a saddle horn, the hame knob of a plow-animal’s collar, or a tree branch; in some cases this opening was large enough for the insertion of an arm, for carrying on the shoulder. Twentieth-century Southern ring jugs and bottles were made as novelties. Georgia-born Javan Brown glazed his “old-time” ring jugs on one side only (that side faced out so that the sun reflected off the shiny glaze, while the porosity of the unglazed side allowed limited evaporation of the water, to keep it cool). Marie Rogers of Jugtown, Georgia, calls them “Confederate jugs,” having heard from her husband, Horace (from whom she learned to make them), and his father, Rufus, that they sometimes were used as canteens by Rebel soldiers in the Civil War.[43] Bill Gordy of Cartersville, Georgia, added a mushroom-shaped stopper to his ring jugs, which he coated with his signature “Mountain Gold” glaze.[44]

The “monkey” (an Afro-Caribbean term for thirst) jug is distinguished by a stirrup handle across the top and a tubular, canted (off-center and angled) spout. A second neck (which could have a widened mouth for filling) or airhole would cause the water to stream into the drinker’s mouth (fig. 35). The separately thrown necks are located either below the handle terminals in the plane of the handle or on opposite sides of it. This form, also traceable to ancient Greece, is concentrated in Africa and Mediterranean Europe (figs. 36, 37); in Spain, where it is known as a botijo, it is virtually a national emblem, with three museums devoted to its seemingly infinite variety in shape, glaze, and ornamentation.[45] In America, imports from Europe may have inspired Northern monkey jugs; in the South, where the form was made by slave potters, a West African source is probable.[46]

Craft into Art: Making Faces on Jugs

Working in such a malleable medium day in and day out, it is not surprising that potters the world over have seen their clay as a kind of mirror and accepted its challenge to model a human likeness on a pot, pushing utilitarian craft into plastic art. This anthropomorphizing impulse is stronger in some clay-working societies than in others; in England, for example, it surfaced several times, first with Romano-British burial urns, then with medieval “face-on-front jugs,” and finally with the “Toby jugs” of late-eighteenth-century Staffordshire, which initiated an industrial tradition of slip-cast character mugs continuing to this day.[47] Evidently, however, England was not the source of America’s face-jug traditions.

In reviewing what is known of those traditions, three points should be made by way of introduction. First, although many humanoid vessels made in the United States are indeed jugs, some are pitchers, cups, jars, or bottles. Second, not all depict just faces or heads; some are full figures. Third, Native Americans of the South made “people pots” during the Mississippian era (a.d. 800–1540), too early to have influenced the Southern face jugs discussed here.[48]

As with other adaptations of the jug form in the United States, face vessels—as both a historical and a living tradition—have been concentrated in the South. However, the oldest known Euro-American examples are from the early-nineteenth-century Philadelphia workshop of Henry Remmey Jr. (fig. 38), whose great-grandfather, stoneware potter John Remmey, had immigrated to Manhattan from the Rhineland in the 1730s. John would have been familiar with the graybeard jugs still being made in Germany, and if he made them in New York and passed the concept to his descendants, then Henry’s face vessels are Americanizations of the German tradition.[49]

A substantial group of early Southern face vessels was made between 1863 and 1865 by enslaved African-American potters at Colonel Thomas Davies’s Palmetto Fire Brick Works at Bath, in the old Edgefield District of west-central South Carolina.[50] Distinguished by bulging eyes and bared teeth of kaolin inset into the stoneware clay body, the iron-based mineral that darkened the alkaline glaze on some, along with the wax resist used to keep the glaze off the white eyes and teeth to maximize contrast, leave little doubt that they were meant to represent their makers’ race (figs. 39, 40). Pioneer ceramics historian Edwin AtLee Barber, after corresponding with Davies, was the first to discuss them in print: “These curious objects . . . possess considerable interest as representing an art of the Southern negroes. . . . The modeling reveals a trace of aboriginal art as formerly practiced by their ancestors in the Dark Continent.”[51] Barber says nothing, however, of the makers’ motivations. Sixty years later, Yale University art historian Robert Farris Thompson advanced Barber’s suggestion of African origins, arguing that later white face-jug makers such as Cheever Meaders appropriated the “Afro-Carolinian” tradition.[52]

Germany and Africa, then, are two possible sources for American face jugs, with a third possibility that they arose independent of any Old World influence. Can we come any closer to resolving this historical dilemma? Anthropomorphic clay vessels were indeed made in West Africa (the chief source area of the Atlantic slave trade), perhaps early enough for the idea to be brought by slaves. The Yungur of Nigeria, for example, made portrait pots called wiiso to honor ancestral spirits at shrines,[53] and the Mambila of Cameroon made similar figural vessels (fig. 41). The angry expressions of some Afro-Carolinian face vessels, which could be interpreted as a nonverbal protest against enslavement, and a few tantalizing hints that these vessels may have been used in magico-religious or mortuary practices, at least suggest that they had a meaning distinct from face jugs by white potters. This raises the question whether white potters in the South made face vessels as early as the slave-made ones.

In 1995 a piece in a private collection surfaced that addresses this question (fig. 42). An alkaline-glazed, happy-faced jug with the monkey form, it is stamped “CHANDLER / MAKER,” the mark of Thomas Chandler, a white potter who worked in Edgefield District from 1838 to 1852.[54] Made about 1850, it preceded the slave-made face vessels from the Davies workshop by over a decade. Before moving to South Carolina, Virginia-born Chandler may have worked as a potter in New York State; it is remotely possible that in his Northern sojourn he met and learned of face vessels from one of the Remmeys.[55] Did Chandler then introduce the concept to Edgefield slave potters, or were they working in a separate, perhaps African-based, tradition? We now know that the face jugs of Cheever and Lanier Meaders were part of a continuous Anglo-Southern tradition, but whether ultimately inspired by slave-made examples, as Thompson suggests, might never be learned (fig. 43).

The Jug Today

Jugs are still indispensable for keeping liquids, from bleach to milk and larger volumes of wine. Now, though, they rarely are made of clay; glass and plastic containers are less expensive to produce, and the latter has the further advantage of being less breakable (fig. 44). In recent years, a few whiskey companies have used mold-made clay jugs to reinforce the old-fashioned image of their product, and school-trained studio potters may occasionally throw a jug to demonstrate that they are not embarrassed to make a useful form despite the current trend of pottery as Art.[56]

In the 1980s and 1990s it seemed as though every potter in the South, folk and otherwise, was trying his or her hand at face jugs, which had become something of a regional art icon (for which Lanier Meaders deserves much of the credit).[57] Today, however, the handcrafting of jugs, with or without faces, is largely the prerogative of a small number of traditionally trained potters, and the domain of a form that once dominated utilitarian American ceramics has shrunk to rural North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama (figs. 45-47). The market has become one of collectors and home decorators, and the everyday uses of these fluid vessels have all but dried up.

Green or brown alkaline glazes used on folk stoneware of the lower South may have been developed about 1810 by Dr. Abner Landrum of Edgefield District, South Carolina, inspired by Jesuit missionary Père d’Entrecolles’s account of Chinese high-firing woodash- and lime-based glazes, first published in 1735. The new glazes were then carried westward by Edgefield-trained potters, reaching Texas by 1850. See John A. Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983), pp. 58–62; Daisy Wade Bridges, Ash Glaze Traditions in Ancient China and the American South (Robbins, N.C.: Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society, 1997); Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stonewares, The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1981), pp. 202–10; and Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), pp. 16–20, 144–47.

Bengt Olsson, Memphis Blues and Jug Bands (London: Studio Vista, 1970); Laurie Wright and Fred Cox, The Jug Bands of Louisville (Chigwell, Essex, Eng.: Storyville Publications, 1993).

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word jug was in use by 1538 but its etymology is uncertain. Josiah Wedgwood suggested that it came from the pet name for Joan or Judith, but that is inadequate as an explanation.

This quote is first attributed to Shaw in “Picturesque Speech and Patter,” Reader’s Digest 41 (November 1942): 100, but I have not been able to trace it to a specific work of his.

E.g., R. K. Henrywood, An Illustrated Guide to British Jugs: From Medieval Times to the Twentieth Century (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1997).

“The Brown Jug” was composed in 1761 by Francis Fawkes. It describes the corpse of corpulent toper Toby Filpot (inspired by real-life big drinker and fellow Yorkshireman Henry Elwes, who died that same year) moldering into clay, to be recycled by a potter into “this brown jug, / Now sacred to friendship, to mirth and mild ale.” The poem, along with printed images, is thought to have inspired, in turn, Staffordshire’s Toby character mug.

“The Little Brown Jug” was composed by Philadelphian Joseph Eastburn Winner in 1869, later becoming a Glenn Miller jazz standard: “Me and my wife live all alone / In a little log hut we call our own; / She loves gin and I love rum, / And don’t we have a lot of fun! / Ha, ha, ha, you and me, / Little brown jug, don’t I love thee!” The narrator’s diction suggests that Winner intended the song as a spoof of Quaker support for temperance.

Henry Hodges, Technology in the Ancient World (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), pp. 114–17, 156–57, 179–81, 185–87.

Charles A. Burney, The Ancient Near East (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977), p. 107; Ruth Amiran, Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land: From Its Beginnings in the Neolithic Period to the End of the Iron Age ([New Brunswick, N.J.]: Rutgers University Press, 1970), pp. 58V.; World Ceramics, edited by Robert J. Charleston (London and New York: Paul Hamlyn, 1968), p. 23 (no. 32); Trudy S. Kawami, Ancient Iranian Ceramics from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections (New York: Arthur M. Sackler Foundation and Harry N. Abrams, 1992), pp. 94, 110, 217–18; A. D. Lacy, Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age (London: Methuen, 1967), pp. 75 (e), 178 (a); James Whitley, Style and Society in Dark Age Greece: The Changing Face of a Pre-Literate Society 1100–700 B.C. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pl. 11; Meisterwerke Altägyptischer Keramik: 5000 Jahre Kunst und Kunsthandwerk aus Ton und Fayence (Höhr-Grenzhausen: Rastal-Haus, 1978), pp. 179 (no. 298), 182 (no. 311).

John W. Hayes, Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), pp. 22 (pl. 5 left), 25 (pl. 7), 55 (fig. 20, no. 9), 56 (fig. 21, no. 3), 61 (fig. 25, no. 7), 75 (pl. 28), 93 (pl. 39, top); Val Rigby and Ian Freestone, “Ceramic Changes in Late Iron Age Britain,” in Pottery in the Making: Ceramic Traditions, edited by Ian Freestone and David Gaimster (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), p. 61 (fig. 6); Vivien G. Swan, Pottery in Roman Britain (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 1975), pp. 38 (pl. 30 center), 43 (no. 21); K. J. Barton, Pottery in England from 3500 B.C.–A.D. 1730 (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1975), p. 96 (nos. 26–27); Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 20, 28. Greek and Roman potters also made amphoras, related to jugs but often larger and with two loop handles and an elongated, tapering body.

World Ceramics, p. 116 (no. 339b); Bernhard Beckmann, “The Main Types of the First Four Production Periods of Siegburg Pottery,” in Medieval Pottery from Excavations, edited by Vera I. Evison et al. (New York: St. Martin’s, 1974), pp. 194, 209–10 (nos. 44–52). The German language adds to semantic confusion: while certain vessel types are given very specific names, what Americans call a jug is referred to variously as a Krug, Flasche, or Pulle. The latter two terms translate as “bottle,” while the more generic Krug can mean “jug,” “tankard or mug,” “jar or crock,” and “pitcher.”

E.g., David Gaimster, German Stoneware 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), pp. 85V.; Peter Seewaldt, Rheinisches Steinzeug (Trier: Rheinischen Landesmuseums, 1990), pp. 37ff.

Called Bellarmines by English writers, these anthropomorphized jugs were thought to be caricatures of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino (1542–1621), an opponent of Protestantism in central Europe. However, the earliest dated example was made in 1550, while some with hand-modeled faces predate 1500 (Anthony Thwaite, “The Chronology of the Bellarmine Jug,” Connoisseur 182 [April 1973]: 255–62; Margaret Thomas, German Stoneware: A Catalogue of the Frank Thomas Collection of German Stoneware [Woodbridge, SuVolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2003]). Another theory is that the bearded face represents the Wild Man of the Woods, a northern European folklore figure (Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 209). In England, graybeard jugs were recycled as charms to ward off witches, for which see Ralph Merrifield, The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), pp. 163–75, and Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, pp. 118–26. Some sixteenth-century Bartmanns have a wider mouth than jugs as we are defining them herein, and probably were for drinking, not storage (e.g., Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 67 [no. 3.21] and color pl. 12).

Wilhelm Elling’s Steinzeug aus Stadtlohn und Vreden (Vreden: Hamaland-Museum, 1994), for example, documents a tradition of salt-glazed jug-making near the Dutch border, west of Münster, continuous from the seventeenth century to the present.

J. N. L. Myres, Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969); Cathy Haith, “Pottery in Early Anglo-Saxon England,” in Freestone and Gaimster, eds., Pottery in the Making, pp. 146–51. Globular-bodied, narrow-necked bottles—jugs minus a handle—from Kent burial sites, if English-made, may mark the reintroduction of the potter’s wheel from the Continent as early as the seventh century; see Vera I. Evison, “The Asthall Type of Bottle,” in Evison et al., eds., Medieval Pottery from Excavations, pp. 77–92 and pls. ii–iv.

Barton, Pottery in England, p. 109; Michael R. McCarthy and Catherine M. Brooks, Medieval Pottery in Britain A.D. 900–1600 (Leicester, Eng.: Leicester University Press, 1988), pp. 231 (no. 667), 248 (no. 782), 261 (no. 861), 278 (no. 983), 279 (no. 985), 383 (no. 1615), 384 (no. 1623), 397 (nos. 1700, 1706).

E.g., Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, p. 166. For English non-delft earthenware jugs of the 1600s, see R. Coleman-Smith and T. Pearson, Excavations in the Donyatt [Somerset] Potteries (Chichester: Phillimore, 1988), pp. 80, 148, 156, showing jugs that are actually called jugs!

Peter C. D. Brears, The English Country Pottery: Its History and Techniques (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971), p. 70; Andrew McGarva, Country Pottery: The Traditional Earthenware of Britain (London: A and C Black, 2000), pp. 24–26, 29; John Manwaring Baines, Sussex Pottery (Brighton: Fisher Publications, 1980), pp. 15, 45. Puzzle and West Country “harvest jugs” were not jugs by our definition but drinking vessels, the former a trick mug, the latter essentially a pitcher.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, pp. 309–17; Jonathan Horne, “John Dwight, ‘The Master Potter’ of Fulham,” Antiques 143 (April 1993): 562–71; Adrian Oswald et al., English Brown Stoneware 1670–1900 (London: Faber and Faber, 1982); Robin Hildyard, Browne Muggs: English Brown Stoneware (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985).

One way of determining when the American meaning arose is to find early illustrations of jugs associated with the word, for example in the potters’ price lists reproduced in: Harold F. Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery (Philadelphia: Chilton, 1971), p. 41 (Clarkson Crolius pottery, Manhattan, 1809); William C. Ketchum Jr., Early Potters and Potteries of New York State (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1970), p. 179 (John Burger pottery, Rochester, 1857); and Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 147 (Norton pottery, Bennington, Vermont, 1856), 149 and 151 (Farrar pottery, Fairfax, Vermont, 1840 and 1851); as well as in literary publications such as “Ham Rachel, of Alabama,” in Hardin E. Taliaferro (“Skitt”), Fisher’s River (North Carolina) Scenes and Characters (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1859), pp. 266–67.

Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, in editing The Art of the Potter (New York: Main Street/Universe, 1977) from Antiques, organized the articles on American redware into two sections, “The Germanic Influence” and “The English Influence.”

David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh, “Imitation, Innovation, and Permutation: The Americanization of Bay Colony Lead-Glazed Redwares,” in Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, 1625–1850, edited by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1985), pp. 209–28.

Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, p. 235.

Ibid., figs. 13, 37, 39–41, 73, 84; Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, color pl. [11], pp. 155, 228; Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, pp. 43, 47, 51, 57, 65, 66–69; Regional Aspects of American Folk Pottery, introduction by William C. Ketchum Jr., exh. cat. (York, Pa.: Historical Society of York County, 1974), figs. 1, 3, 56, 57, 59, 60; Brian Cullity, Slipped and Glazed: Regional American Redware (Hyannis, Mass.: Patriot Press for Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, 1991), pp. 31 (no. 48), 32 (no. 51), 37 (no. 63), 50 (no. 99), color pls. 1, 2, 4, and 6; Arthur E. James, The Potters and Potteries of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer, 1978), p. 88; Jeannette Lasansky, Central Pennsylvania Redware Pottery 1780–1904 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press for Keystone Books, 1979), p. 42; Anthony W. Butera Jr., “‘Informed Conjecture’: Collecting Long Island Redware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 214, 219; Barbara H. Magid and Bernard K. Means, “In the Philadelphia Style: The Pottery of Henry Piercy,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), p. 56 (fig. 25); Don Horvath and Richard Duez, “The Potters and Pottery of Morgan’s Town, Virginia: The Earthenware Years, Circa 1796–1854,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 103 (fig. 5), 113–14 (figs. 28–32); H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), pp. 72 (figs. 3.14–.15), 89 (fig. 4.13), 104 (fig. 4.60), 119 (fig. 4.109), 204 (fig. 5.14); John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, 1972), p. 124; Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), color pl. 3; Two Centuries of Potters: A Catawba Valley Tradition, edited by Bill Beam et al. (Lincolnton, N.C.: Lincoln County Historical Association, 1999), front cover and p. 14 (fig. 1). Perhaps due to its emphasis on decorated pieces, there are no jugs in the catalog of the finest public display of Pennsylvania redware, Beatrice B. Garvan’s The Pennsylvania German Collection (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982).

Early American stoneware potters working largely in the German tradition include members of the Crolius and Remmey families, Thomas Commereau, and David Morgan of Manhattan, James Morgan of South Amboy and Old Bridge, New Jersey, and Jonathan Fenton of Boston. Those working more in the English tradition include William Rogers of Yorktown, Virginia, Frederick Carpenter of Charlestown, Massachusetts, and Branch Green of Philadelphia. English-born Anthony Duche of colonial Philadelphia made stoneware in both the German and English styles (Robert L. Giannini III, “Anthony Duche, Sr., Potter and Merchant of Philadelphia,” Antiques 119 [January 1981]: 198–203).

Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, pp. 237, 249, 252, 255–56, 260; Greer, American Stonewares, pp. 155–56, 182, 225; Donald Blake Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971), pp. 65–66, 98, 160; Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, pp. 81–90, 106–7, 114–16, 119–22; James R. Mitchell, “The Potters of Cheesequake, New Jersey,” in Ceramics in America, Winterthur Conference Report 1972, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), pp. 319–38; Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 318 (fig. 6.6); Norman F. Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory: The Kilns and Ceramics of the ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 16, 32; Quincy J. Scarborough Jr., North Carolina Decorated Stoneware: The Webster School of Folk Potters (Fayetteville, N.C.: Scarborough Press, 1986).

E.g., Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 35, 37, 39, 40, 45, 53, 100, 147, 150, 153, 154–56, 159, 169, color pls. 2–4, 6, 12; Greer, American Stonewares, pp. 170, 173. The double-collared neck sometimes migrated west on jugs made by Edgefield-trained potters (e.g., Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 64, by J. S. Nash of Texas; Burrison, Brothers in Clay, p. 123, attributed to Cyrus Cogburn of Georgia).

Greer, American Stonewares, p. 76; Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, p. 83; Cornelius Osgood, The Jug and Related Stoneware of Bennington (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971), p. 116.

A glaring historical inaccuracy of certain films portraying the colonial or frontier era is the inclusion of these late-nineteenth-century shouldered jugs. The earliest examples are two-toned, with salt-glazed wall and Albany slip-glazed shoulder, neck, and interior, as the stacking dish blocked the salt glazing. Later examples, often molded on a jolly machine rather than thrown, either carried on the two-tone effect with Bristol glaze replacing the salt or were fully Bristol glazed. For a sample of such jugs, see Lyndon C. Viel, The Clay Giants: The Stoneware of Red Wing, Goodhue County, Minnesota, 3 vols. (Des Moines, Ia.: Wallace-Homestead, 1977–87).

John McGuffin, In Praise of Poteen (Belfast: Appletree Press, 1978); Joseph Earl Dabney, Mountain Spirits: A Chronicle of Corn Whiskey from King James’ Ulster Plantation to America’s Appalachians and the Moonshine Life (New York: Scribner, 1974).

Quoted in Burrison, Brothers in Clay, p. 132.

Jim Broom in North Carolina and Horace Brown and Norman Smith in Alabama, besides the previously mentioned “Jughead” for Georgia’s Lanier Meaders.

Shelby County, Alabama; Upson and Pike Counties, Georgia; Catawba, Lincoln, and Buncombe Counties, North Carolina; Greenville County, South Carolina; and White County, Tennessee.

E.g., Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, p. 94 (twenty gallons, Vermont); Greer, American Stonewares, p. 107 (twelve gallons, Ohio). Stoneware “fountain” and keg forms also were used as coolers.

Earthenware “cider jars” were a specialty of Halifax-area, West Yorkshire, potters. They typically have a spigot hole in the lower wall; some were lead-glazed only halfway down the outside so the temperature differential would hasten fermentation of the hard cider. The same basic shape in brown salt-glazed stoneware, as made in the Liverpool area, apparently was used in transatlantic trade. Dating from the late eighteenth through the nineteenth century, these large English jugs rarely have been published, but see Graham Wilkinson, A History of Local Potteries (Bradford, W. Yorkshire, Eng.: Bradford Art Galleries and Museums, 1981), p. 11 (b); Zug, Turners and Burners, p. 31; Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, p. 154 (center); John A. Burrison, Handed On: Folk Crafts in Southern Life (Atlanta: Atlanta Historical Society, 1993), p. 41 (no. 4).

E.g., Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, p. 131 (fig. 1, New York); Greer, American Stonewares, p. 107 (Ohio); Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America, pp. 67 and 165 (New York State), 94 (Ohio); Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 172, 149 (South Carolina).

Anne S. McPherson, “‘That Article of Household Furniture Peculiar to Earlier Days in the South’: Sugar Chests in Middle Tennessee and Central Kentucky, 1800–1835,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 23 (winter 1997): 1–65; Robert Hicks and Benjamin H. Caldwell Jr., “A Short History of the Tennessee Sugar Chest,” Antiques 164 (September 2003): 128–33; Neat Pieces: The Plain-Style Furniture of Nineteenth Century Georgia, exh. cat. (Atlanta: Atlanta Historical Society, 1983), p. 126.

Greer, American Stonewares, pp. 42–43, 178; Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 37, 45, 49, 150–51, 153, 155–56, 169, color pls. 3–4; Zug, Turners and Burners, pp. 46, 48, 77, 87, 307, color pls. 7, 16; Beam, Two Centuries of Potters: A Catawba Valley Tradition, pp. 14–15, 33, 36, 39, 75, 80–81, 87, 90; Burrison, Brothers in Clay, pp. 23, 65, 123–25, 127, 145, 175, 268.

Osgood, The Jug, pp. 96, 106.

Burrison, Brothers in Clay, color pl. 6 and pp. 66 (pl. 35), 116–17, 255; Zug, Turners and Burners, p. 368 (fig. 12-14).

Lacy, Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age, p. 218 (fig. 90d), a Mycenaean example dating to 1200 b.c.

See, e.g., Otto Von Falke, Das Rheinische Steinzeug, 2 vols. (Osnabrück: Otto Zeller, 1977), 1: 89, and 2: 59–61, 109, for examples dating to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Zug, Turners and Burners, pp. 375–77; “Lin Craven Making a Ring Jug,” in John A. Burrison, “Folk Pottery,” Folklife Section, New Georgia Encyclopedia (video clip, available online; www.georgiaencyclopedia.org).

Burrison, Brothers in Clay, pp. 184–85.

Lindsey King Laub, Evolution of a Potter: Conversations with Bill Gordy (Cartersville, Ga.: Bartow History Center, 1992), cover, color pl. 10.

See Lacy, Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age, p. 259 (fig. 102e), for an example of 1800 b.c. Museo del Botijo in Toral de los Guzmanes, León; Museo del Botijo in Villena, Valencia; Museu del Càntir d’ Argentona, Cataluña. For recent Spanish jugs, “monkey” and otherwise, see J. Llorens Artigas and J. Corredor-Matheos, Spanish Folk Ceramics of Today (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1974).

E.g., Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, p. 193 (left, Vermont); Cullity, Slipped and Glazed, p. 26 (no. 34, Massachusetts); Lasansky, Central Pennsylvania Redware Pottery, p. 43; Greer, American Stonewares, pp. 162 and 196 (Ohio). Nigel Barley, Smashing Pots: Works of Clay from Africa (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), pp. 27, 50, 118, 122; John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), pp. 86–90. Monkey jugs were not made in England, with the exception of the “Sarum kettle” manufactured by Doulton of Lambeth about 1900, based on an African example in the Salisbury Museum.

Barton, Pottery in England, p. 99; Griselda Lewis, A Collector’s History of English Pottery (New York: Viking Press, 1969), pp. 15 (fig. 9), 18 (figs. 18, 20, 21), 57 (fig. 106), 123 (fig. 227); McCarthy and Brooks, Medieval Pottery in Britain, pp. 229, 269, 337, 367; Jacqueline Pearce and Alan Vince, Surrey Whitewares (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1988), pp. 24, 78, 127, 129–31; Desmond Eyles, “Good Sir Toby”: The Story of Toby Jugs and Character Jugs through the Ages (London: Doulton, 1955); Vic Schuler, Collecting British Toby Jugs . . . 1780 to the Present Day (London: Francis Joseph, 1997); Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, p. 310.

Roy S. Dickens Jr., Of Sky and Earth: Art of the Early Southeastern Indians (Atlanta, Ga.: High Museum of Art, 1982), pp. 28, 52–53, 58, 82–84; Michael J. O’Brien, Cat Monsters and Head Pots: The Archaeology of Missouri’s Pemiscot Bayou (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994), pp. xxxiv, xxxix.

A face pitcher attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. is dated 1838; a two-faced monkey jug likely by him or his son Richard is dated 1858. Both are salt-glazed stoneware, with cobalt-blue–highlighted facial hair as seen on some German graybeards. For the Remmeys, see Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, pp. 114–18; Ketchum, Early Potters and Potteries of New York State, pp. 30–32; Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), pp. 22–25.

For discussions of antebellum and later African-American face vessels from South Carolina, see Vlach, Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, pp. 81–92, and Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 79–87, 108–9, color pls. 12–13.

Edwin AtLee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1909), p. 466. Stereoscopic cards issued in 1882 by photographer J. A. Palmer of Aiken, South Carolina (in Edgefield District) depict a Negro boy and girl pondering a monkey-form face jug, the earliest known illustrations of a locally made face vessel; titled “An Aesthetic Darkey,” the images likely were inspired by W. H. Beard’s painting, The Aesthetic Monkey, published that year in Harper’s Weekly (Making Faces: Southern Face Vessels from 1840–1990, exh. cat. [Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, 2000], pp. 15–16).

Robert Farris Thompson, “African Influence on the Art of the United States,” in Black Studies in the University, edited by Armstead L. Robinson et al. (New York: Bantam Books, 1969), p. 141.

Marla C. Berns, “Pots as People: Yungur Ancestral Portraits,” African Arts 23 (July 1990): 50–60 and front cover. The Mangbetu of Zaire made juglike figural pots with vertical loop handles, but too late (late 1800s) to have influenced South Carolina slaves (Barley, Smashing Pots, pp. 148–49).

Making Faces, pp. 6–7; Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 47, 51–54.

This scenario is not so far-fetched; a later potter, Charles Decker, began his career at the Remmey Pottery in Philadelphia before establishing northeast Tennessee’s Keystone Pottery in 1871, where he and his son William made Remmey-style face jugs (The Pottery of Charles F. Decker: A Life Well Made [Jonesborough, Tenn.: Jonesborough/Washington County History Museum, 2004], pp. 52–53, 58).

A review of recent issues of Ceramics Monthly, Studio Potter, Ceramics Art and Perception, and American Craft suggests that the jug is not among the forms privileged by contemporary studio potters.

Making Faces; William W. Ivey, North Carolina and Southern Folk Pottery (Seagrove, N.C.: Museum of North Carolina Traditional Pottery, 1992); Robert C. Lock, The Traditional Potters of Seagrove, North Carolina (Greensboro, N.C.: Antiques and Collectibles Press, 1994), pp. 184–90; Barry G. Huffman, Catawba Clay: Contemporary Southern Face Jug Makers (Hickory, N.C.: A. W. Huffman, 1997); Michael A. Crocker and W. Newton Crouch Jr., The Folk Pottery of Cheever, Arie, and Lanier Meaders: A Pictorial Legacy (Griffin, Ga.: C and C Productions, 1994).