First-floor southeast parlor, Philipse Manor, Yonkers, New York, 1745-1755. (New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 1 (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

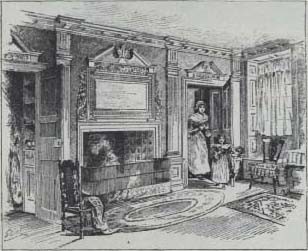

Engraving of the first-floor southeast parlor, Philipse Manor, from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (1882). (Collection of the Hudson River Museum of Westchester, Yonkers, New York; photo, John Kennedy.)

Detail of the rosette of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 1 (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the tablet of Diana on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 1. (Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site, Yonkers, NY. New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Second-floor southeast parlor, Philipse Manor. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Engraving of the second-floor southeast parlor, Philipse Manor, from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (1882). (Collection of the Hudson River Museum of Westchester, Yonkers, New York; photo, John Kennedy.)

Detail of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 6. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left side bracket of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 6. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze applique and ornament of the right door in fig. 6. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze applique of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 6. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a carved stair bracket, Philipse Manor. (Courtesy of Philipse Manor; Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

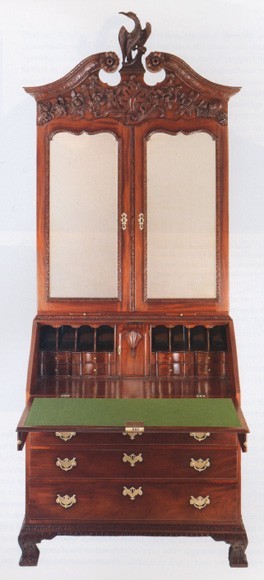

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1745-1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar and gum. H. 99 1/2", W. 45 1/2", D. 25". (Chipstone Foundation, acc. 1991.5; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The heron, plinth, and applied carving flanking the outermost roses (approx. 6") were restored based on the carving in Philipse Manor.

Detail of the applique on the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the applique on the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of left front foot and base molding of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1745-1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar, gum, oak, and mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; courtesy, Walton Antiques.)

Detail of the prospect door of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 18. (Private collection; courtesy, Walton Antiques.)

Bedstead with carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1750-1755. Mahogany with red oak and white pine (nineteenth-century lath frame and headboard). H. 89 1/2", W. 54 1/8", D. 78". (Courtesy of Historic New England/SPNEA, bequest of Janet M. Agnew, acc. 1975.152; photo, Richard Cheek.) During the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, the bedstead was reduced in width by 4-6 inches.

Detail of the knee carving on the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the carving on a side rail of the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the urn acanthus on a foot post of the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. )

Detail of a basket capital on the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

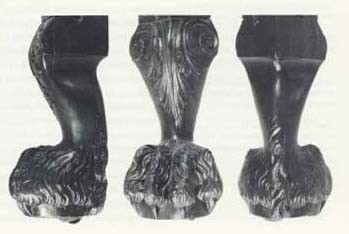

Front view of a paw foot of the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Side view of a paw foot of the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Back view of a paw foot of the bedstead illustrated in fig. 20. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

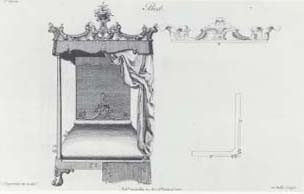

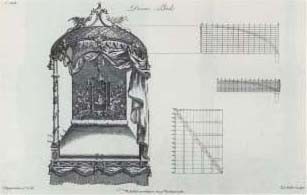

Plate 27 from Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754, 1755). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Fragment of a footpost with carving attributed to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1745-1755. Mahogany. H. 44 1/2" (Private collection; photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Side, front, and back views of the paw foot of the footpost illustrated in fig. 29. (Private collection; photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

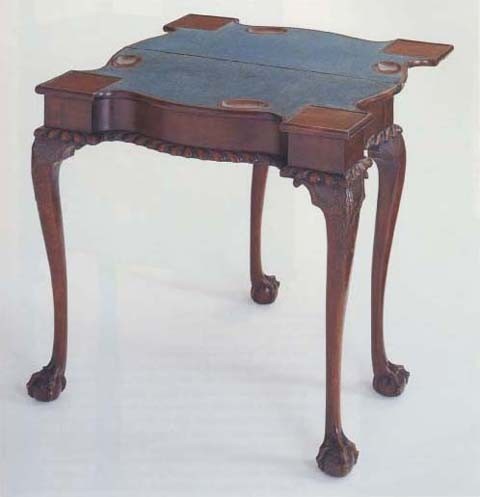

Card table with carving attributed to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1750-1755. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 28", W. 30", D. 15" (closed). (Chipstone Foundation, acc. 1965.5; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving and fluted and gadrooned molding of the card table illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers with carving attributed to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1750-1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 33", W 35 1/2", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. G54.86.)

Detail of the left foot carving and fluted and gadrooned molding on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 35. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

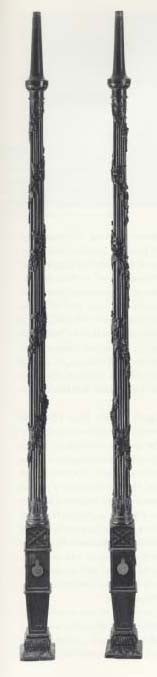

Footposts of a bedstead with carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York, 1750-1755. Mahogany. H. 94". (Chipstone Foundation, acc. 1991.4; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the footposts illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the footposts illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Plate 31 from Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754,1755) (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the mortises for a rail and spring rod on the footposts illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair with carving attributed to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, Charleston, South Carolina, 1755-1756. Mahogany with sweet gum. H. 53 3/8", W, 37 5/8" (at arms). (Collection of The McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the knee carving on the armchair illustrated in fig. 42. (Collection of The McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Front view of a paw foot of the armchair illustrated in fig. 42. (Collection of The McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Side view of a paw foot of the armchair illustrated in fig. 42 (Collection of The McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Rear view of a paw foot of the armchair illustrated in fig. 42. (Collection of The McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

During the third quarter of the eighteenth century the rococo style emerged in New York furniture and architectural carving. Like many British designers of the mid-1740s, New York cabinetmakers, carvers, and master builders were slow to accept the rococo style. Although rococo details are discernible in New York carving from the early 1750s, they typically are restrained and confined within a classical framework. This modified style was particularly well-suited to New York's Anglo-European aristocracy who were accustomed to the strong architectural overtones of baroque classicism.[1] The rococo style matured during the mid-1750s, coincident with the publication of British design books such as Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754). Several examples of New York furniture and architectural carving were based on published designs and some appear to have been executed almost immediately after the corresponding patterns were issued. The finest work reflects an awareness of London fashions and a level of technical competence that was rarely equaled in colonial America.

As in every colonial city, artisans in New York were dependent on a wealthy style-conscious patronage. The origins of this aristocratic society can be traced to the Dutch West India Company's establishment in 1629 of large land grants called patroonships. The patroons, or owners, were given land on the condition that they settle at least fifty persons at their own expense. Although only one patroonship survived the period of Dutch rule (1609-1664), the British, following their conquest of New Netherland, introduced a manorial system based on large land holdings. Like the earlier patroonships, the manorial system created a pronounced social hierarchy that gave the landlords wealth, prestige, and a considerable measure of political power.[2]

European-born colonists like the Philipses were among the most successful and influential land owners under the British system. In return for political allegiance, Frederick Philipse received a patent granting manorial status to his estate in 1693. Through land speculation, slave trading, and two financially advantageous marriages, he amassed a fortune that enabled him to maintain residences at Philipseburg Manor and in Manhattan. In 1716, Frederick Philipse II became the second lord of Philipseburg Manor. Educated in England, he pursued a legal career culminating in his appointment to the New York Supreme Court in 1755. His principal residence was a grand country house built (or enlarged from an earlier structure) on his estate during the second quarter of the eighteenth century. With its hipped roof and five-bay brick facade, Philipse Manor is one of the most important New York houses of the colonial period. It reflects a series of ambitious building campaigns culminating in the installation of a luxurious interior about 1750.[3]

The southeast parlor on the first floor has a stucco and papier-mache ceiling and a monumental chimneypiece flanked by engaged stop-fluted ionic columns and doors with classical entablatures (fig. 1). Recalling the style of Palladian architects, such as William Kent, the chimneypiece has a compressed broken-scroll pediment with bold floral rosettes, carved moldings and frets, and a swelled oak-leaf frieze with a central tablet depicting Diana (figs. 2-5). The side brackets are incorrect, late nineteenth-century replacements based on those in the southeast parlor on the second floor. The original brackets had additional acanthus inside the S scrolls and heavy husk (bellflower) drops rather than garlands (fig. 3).[4]

The corresponding parlor on the second floor is even more detailed. Although the architectural arrangement of the two parlors is basically the same, the chimneypiece on the second floor is flanked by fluted pilasters and doors with pitched pediments, carved frieze appliques, and central ornaments (figs. 6-12). As fig. 7 shows, the ornaments of the door pediments have been missing since the late nineteenth century; however, surviving fragments of the carving indicate that they were large birds perched on the crest of a rococo plinth (fig. 10). They may well have been more sculptural renditions of the small bird in the frieze applique of the chimneypiece (fig. 11) or prospect door of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 19 later in this article. Together with the abstract shells of the door friezes and playful asymmetrical scrollwork framing the small bird on the overmantle frieze, these ornaments are among the earliest manifestations of the rococo style in America (figs. 10, 11).[5]

Although tremendously important as documents of an emerging style, these ornaments appear almost as intrusions in the classical fabric of Philipse Manor. Colonial conservatism was not entirely the reason for Philipse's tenuous embrace of the rococo style. As late as 1759, architects in England also were looking back to the designs of first generation Palladians. In his Treatise on Civil Architecture, Sir William Chambers wrote: "I believe we may justly consider Inigo Jones as the first who arrived at any great degree of perfection [in the design of chimneypieces]. . . . Others of our Architects, since his time, have wrought upon his ideas; and some of them, particularly the late Mr. Kent, have furnished good inventions of their own."[6]

The artisan who executed the carving in Philipse Manor probably trained in London (or another large urban center in England) during the 1730s or early 1740s when architects, such as James Gibbs, Batty Langley, and William Kent, published their designs and executed important commissions. A marble chimneypiece designed by Kent for the dining room in Houghton Hall, Norfolk, has a central tablet with a bust and garlands with large clusters of grapes and grape leaves that closely resemble those on the chimneypieces in Philipse Manor. The scale and the sculptural quality of the carving in Philipse Manor suggests that the artisan intended his work to resemble stone.[7]

During the Palladian era (1715-1745), architects and cabinet makers often designed furniture to complement interior architecture. A New York desk-and-bookcase made about 1750 has carved details that are virtually en suite with those in Philipse Manor (fig. 13). The bookcase has a low, broken-scroll pediment with bold floral rosettes and intricate moldings like the overmantle in the first-floor parlor (figs. 2, 4, 14). Similarities in the design and execution of the major carved elements indicate that they are by the same hand. Except for differences in size, the rosettes are practically interchangeable. Each has four small petals closed in the center, three large convex petals with deeply fluted and veined depressions, and flat half-petals in the background (figs. 4, 14).

Although much of the detail in the architectural carving is obscured by layers of paint, the carver clearly used similar techniques to outline and model the scrolling leaves on the cove molding of the bookcase and the acanthus on the overmantle fret and stair brackets (figs. 2, 12, 15). Deep vertical cuts made with large flat gouges created strong shadow lines and (with minimal modeling) multiple levels that simplified the shading process. Nearly all the leaves and flowers of the scrollboard applique were duplicated in the bracket garlands in the second-floor parlor (figs. 9, 15, 16). The roses have laminated centers and flat, overlapping petals that the carver shaded with short gouge cuts made within larger flutes. Similar shading cuts are on the tattered shells in the door friezes (fig. 1O) and the body of the bird illustrated in figures 11 and 19. Many aspects of this carver's style are individualistic, but none are more distinctive than his veining and shading. He used a very small gouge or veiner (U-shaped gouge) to cut shallow diverging flutes on the serrated leaves in the bookcase applique and on the small flat leaves and grape leaves in the frieze appliques and bracket garlands in Philipse Manor (figs. 9-11, 15, 16). Most eighteenth-century carving is representational rather than sculptural, but the grape leaves, fruit, and large blooms carved by this artisan are naturalistic and botanically accurate. He used diverging and converging flutes to shade the large acanthus leaves on the feet and scrollboard of the desk-and-bookcase and the side brackets in the second-floor parlor (figs. 9, 16, 17). He also occasionally used perpendicular fluting, or cross-cutting (cuts made perpendicular to the overall flow of the design), on curled leaf ends and on broad convex surfaces.[8]

Another desk-and-bookcase, this one with a history of ownership by Peter and Margaret (Livingston) Stuyvesant, appears to be by the same cabinetmaker and carver (fig. 18).[9] It has mirrored doors with double ogee-shaped rails, a writing compartment with a central prospect door flanked by tiers of serpentine blocked drawers and pigeonholes with shaped brackets, and a cyma reversa base molding. The relief-carved bird on the prospect door of the Stuyvesant desk-and-bookcase compares closely to the bird in the overmantle applique in Philipse Manor (figs. 11, 19). Both have prominent crests, slightly curled beaks, and protruding eyes. To carve the body feathers, the carver used a small gouge to cut short paired flutes within a larger shallow flute. The long tail feathers were simply rough modeled with gouges and chisels.

The construction of the two desks-and-bookcases is consistent with New York work of the mid-eighteenth century. Both pieces have large drawers with fully paneled bottoms and interior drawers with rabbeted bottoms and serpentine fronts that are splayed on the top and side edges. Paneled-drawer construction occurs frequently on New York furniture made between 1700 and 1770. The desk illustrated in figure 13 has thin dustboards with broad beveled edges (front and sides) that are set into grooves ploughed in the drawer blades and drawer runners. In typical early New York fashion, the runners are notched and nailed to the sides. Because nailed runners restrict the movement of case sides, causing the wood to split, London cabinetmakers began using full-bottom dustboards (dustboards that are the full thickness of the drawer blades and that are dadoed to the case sides) during the early 1720s. By the late 1730s, progressive cabinetmakers like Giles Grendey used thin dustboards that they wedged into the dadoes with strips of wood whose grain ran in the same direction as the dustboards. This produced a strong, dust-proof case that could respond to changes in humidity. In contrast, although the dustboards of figure 13 are thin and able to expand and contract, the case sides are rigidly bound by the nailed runners. Slightly later in the century, New York cabinetmakers improved this system significantly by making the runners out of oak and by dadoing them to the case sides.

The technological advances in case construction made by New York cabinetmakers during the early 1750s coincided with a shift to a more mature rococo style. A bedstead with hairy-paw feet, knees ornamented with ruffled C scrolls and vines, balusters with finely detailed acanthus, and basket-capitals with fruit and flowers attests to New York artisans' and patrons' style consciousness (fig. 20). The original owner is not known; however, the bedstead has a nineteenth-century Massachusetts history in the Cambridge-based family of Ersastus Forbes Brigham (b. 1807) and his wife Sophia De Wolf Homer Brigham (d. 1881), who married in Troy, New York, in 1832.[10]

Although certain elements of the carving are rooted in baroque design, the abstract panels and whimsical vines on the side rails and tattered foliage on the knees are clearly rococo (figs. 21, 22). The small carved bells capping the diapered reserves above the knees appear to be a concession to Chinese fancy. It would be difficult to find a closer parallel between furniture and architectural carving than the acanthus on the balusters of the bedstead, on the feet and scrollboard of the desk-and-bookcase, and on the side brackets and frieze appliques in the second-floor parlor of Philipse Manor (figs. 9-11, 15, 17, 23). All of these leaves have similar profiles, converging and diverging veining flutes, and perpendicular crosscuts in the same contexts. In virtually every instance, the carver used a very small gouge (approximately equivalent to a modern 2-mm #8 or #9) to execute the veining. On the grape leaves in the bracket garlands and on the capitals and knees of the bedstead, the flutes are so delicate that they are barely discernible (figs. 9, 24). The carver used large "quarter-round" gouges to rough out the toes and pad segments of the feet (figs. 25-27). To carve the fetlocks, he used relatively small gouges to make angled converging cuts that removed crescent-shaped sections of wood and delineated the individual tufts. After contouring the surfaces with inverted or backbent gouges, he fluted the tufts to accentuate the downward spiral and make the hair appear to roll over against the leg. These techniques are essentially the same as those used to carve the hair of Diana in Philipse Manor (fig. 5).

The footposts of the bedstead are made in two sections and joined with a round mortise and tenon between the stop-fluted and spiral elements. Each post has two cloak pin holes indicating that the bedstead had festooned curtains and a tester frame with pulleys similar to those on a bedstead illustrated in the first edition of the Director (fig. 28). The original curtains probably were nailed to the tester frame and raised with a cord that passed through the pulleys and tied off on the cloak pins. The present headboard and tester frame are nineteenth-century replacements. The original headboard may have been intricately carved or rough modeled and covered with fabric.

Evidence for the form and attachment of the base valences is sketchy; however, they possibly hung beneath the rails so the carving could remain visible. Unlike many bedsteads that have bed bolts to tighten the mortise-and-tenon joints, the Brigham family bedstead has a key-and-eye system. The tenons were locked into the mortises by a large two-pronged key (now missing) that fit into the eyes of wrought iron staples on the rails. Although the rails are altered (shortened at the ends), remnants of wooden pins in the rabbeted edges indicate that the bedstead had a canvas or "sacking" bottom.

The foot rail and lower sections of the footposts are all that survives of the bedstead illustrated in figure 29; however, the two-part post construction, knee carving, and bold hairy-paw feet associate it with the Brigham example. On both objects, the feet have toes with three distinct joints, spiraling fetlocks, and hair that is carved in essentially the same fashion (figs. 25-27, 30-32). In relying on sculptural form rather than surface detail, these resemble smooth-paw feet more than conventional hairy-paw feet. It is difficult to determine whether the feet of these bedsteads are by the same hand or simply products of the same shop (or school). Those of figure 29 are laminated rather than cut from the solid and are less competently carved than the Brigham examples; however, this discrepancy may have been the result of time constraints or cost.[11]

An early serpentine card table with an oral tradition of descent in the Vreeland and Gautier families of New Jersey and New York has carving from the same shop as the preceding pieces (fig. 33). Although it predates the vast majority of New York serpentine card tables by nearly a decade, its construction and carved details are remarkably sophisticated. The rails are dovetailed together and slip-tenoned to the legs at the front corners. The fluted and gadrooned molding glued beneath the rails and rabbeted onto the knees is virtually identical to that on the first desk-and-bookcase (figs. 17, 34). On both, the gadrooning is broad and flat, and the flutes have precisely cut fillets terminated with a gouge cut just short of the molding edge. Several of the elements of the knee carving on the card table are also on the cove molding of the desk-and-bookcase, on the overmantle fret and stair brackets in Philipse Manor, and on the feet of a commode chest of drawers that descended in the Van Rensselaer family of New York (figs. 2, 12, 15, 34-36).[12]

Many sophisticated examples of rococo furniture survive with histories of ownership in the Beekman, Van Cortlandt, and Van Rensselaer families, but none reflects modish London style more clearly than the chest of drawers illustrated in figure 34. Commode (serpentine or "swelled") forms became popular in England during the late 1740s and remained so throughout the eighteenth century. Chippendale, for example, illustrated a variety of commode chests, dressing tables, and clothespresses in rococo and neoclassical styles in all three editions of the Director (1754, 1755, 1762). The Van Rensselaer chest appears to have been made about 1755, one of the earliest completely rococo American case pieces. The sole concession to New York style is fluted and gadrooned molding between the front feet. While the molding is virtually identical to that of the desk-and-bookcase and card table, it is unusual in being nailed directly under the case rather than to a base molding. The case and foot construction also match that of the desk-and-bookcase. On both examples the feet are supported by large vertical blocks that were shaped with gouges and nailed to the bottom of the case.

A pair of footposts by the same carver as the preceding pieces are the most sophisticated American examples in the rococo style (fig. 37). The posts have cascading vines with leaves, fruit, and a variety of naturalistic blooms that literally quote elements on the side brackets in Philipse Manor, knees and "basket capitals" of the Brigham bedstead, and applique of the first desk-and-bookcase (figs. 9, 14-16, 21, 24, 38, 39). In all, relatively simple ornaments like flat chip-carved flowers and leaves are juxtaposed with fully rendered blooms and foliage. Several of the more detailed leaves have diverging veining and deep offsets to create a strong shadow line and divide the surface into two planes for easy fluting. Although many artisans used gigs for fluting and reeding, this carver cut the reeding entirely by hand, a laborious process, particularly in the areas around the leaves and flowers.

The design of the posts appears to derive from a bedstead illustrated in the first edition of the Director or a style that was current at that time (fig. 40). The bedstead probably had an ornate carved cornice, perhaps even a domed example similar to the Director engraving. Unfortunately, the posts retain only partial evidence of how the bedstead was hung. Although the absence of cloak pin holes on the footposts suggests that the curtains were straight-hung from a "compass rod" or from the cornice, the evidence is not conclusive. In the eighteenth century there were intricate pulley systems for drapery curtains that were tied off at the headposts, thus eliminating the need for cloak pins at the foot. Such a system would allow the curtains on a bedstead like this to be "tied up in drapery," as Chippendale described them.[13] Unlike the Brigham bedstead, on which the carved rails were apparently left exposed, the rails of this example were completely covered by the base valences. The bases were suspended from a flexible spring rod that mortised into the legs just above the rails (fig. 41).

An imposing ceremonial armchair made for the State House in Charleston, South Carolina (built 1752-1756), provides strong circumstantial evidence for attributing all of the above-mentioned carving to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, the only New York carver known to have moved to Charleston before the Revolution (fig. 42). As mentioned in reference to the carving in Philipse Manor, Hardcastle probably trained in London. Although there is no documentation for his arrival in New York, he was listed as a freeman there in 1751. On June 30, 1755, the New York Mercury printed a notice by Hardcastle for a runaway apprentice named Stephen Dwight. That Dwight established his own business the following month suggests that the term of Dwight's indenture had nearly expired or that Hardcastle was no longer in the city and able to contest his apprentice's actions. Hardcastle apparently moved to Charleston sometime between July 1755 and his death in October 1756.[14]

Hardcastle's move coincided with the completion and furnishing of Charleston's first State House. Shortly before moving into the new State House, the Commons House of Assembly appointed a committee to "provide such furniture as will be necessary for the service of [the] House." On March 13, 1756, the House resolved to appropriate funds for "such furniture as his Exty. the Governor &. His Majty's Council shall think fit to order for . . . the New Council Chamber." The committee apparently wasted little time in placing orders. On July 6, 1756, the Commons House directed the public treasurer to advance "as much money as will be sufficient to pay the Tradesmen's Bills for . . . Furniture." Although the journals of the upper and lower houses fail to identify these artisans or describe their work, the armchair, which most likely served as the royal governor's chair during sessions of the Commons House of Assembly, may have been one of the first items commissioned for use in the State House.[15]

To create a sense of majesty and formality, the governor's chair probably was placed on a plinth and draped with a canopy similar to the throne of George II in B. Coles's engraving, A View of the House of Peers. Like the king's throne, the stance and seat height mandated the use of a footstool. Although the stool for the royal governor's chair does not survive, it undoubtedly was made en suite with the chair. A royal coat of arms may have been mounted on the crest rail of the governor's chair. Mortises and screw holes there indicate that it was secured with three wooden or wrought iron braces.[16]

The carving on the chair is closely related to that of the bedsteads and probably represents the work of a journeyman associated with Hardcastle in Charleston. Like the Brigham bedstead, the chair has C scrolls with tattered leaves and trailing vines of fruit and flowers on the knees. Both designs feature overlapping flowers, grape leaves with diverging veining, and curled leaves with short, perpendicular shading cuts (figs. 21, 43). The feet of the chair are less competently carved than those of the bedsteads. However, they clearly emerge from the same shop tradition: they have fetlocks with thick, spiraling tufts of hair, toes with three distinct knuckles, and outward-flaring pad segments (figs. 25-27, 30-32, 44-46). The patterns of gouge and chisel cuts used to outline and rough-model the pad segments on the feet of the chair and bedstead are also remarkably similar. So is the basic approach to fluting the hair and carving the retracted claws.

Although the royal governor's chair is a keystone for understanding the development of the rococo style in New York, it has almost no relation to extant Charleston work. Hardcastle's career in Charleston lasted scarcely a year; thus it is doubtful that he significantly influenced local styles. When he died he left a meager estate valued at £84.10.0, including two silver watches, a pair of silver buckles, a gold ring, a crosscut saw, a musket, clothing, a lot of books and "1 Gross & half of Carving Tools with Grindstone."[17]

The architecture and furniture associated with Hardcastle exemplifies forces that governed stylistic change in eighteenth-century New York. The convergence of European and English culture is reflected in the transformation of Philipse Manor from a modest Anglo-European baroque dwelling to an aspiring country seat marked by Palladian interior details and ornate architectural carving. Its owners epitomize the New Yorkers of English and European descent who looked to Britain for the latest customs and fashions. The stylistically advanced carving that can now be attributed to Hardcastle attests to New Yorkers' acute awareness of the flow of British design. As in the earliest rococo designs of William Kent, there are strong baroque overtones in much of Hardcastle's work. This is particularly true of the carving in Philipse Manor and on the two desks-and-bookcases and two paw-foot bedsteads where large-scale, naturalistic ornaments embellish architectural elements and furniture of classical form. The commode card table, chest of drawers, and Director-inspired bed posts (fig. 37) represent a purer interpretation of the rococo style. On these pieces, Hardcastle had successfully integrated rococo form and ornament five to ten years before the style emerged in most other American urban centers. Hardcastle was clearly a pioneer in the early development of the rococo style in New York. However, his shop could not have flourished without parallel advances in the cabinet trade and wealthy, style-conscious patrons.

ACKNOWEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the author thanks Gavin Ashworth, Deborah Gordon, Morrie Heckscher, Ned Hipp, Frank Horton, George and Linda Kaufman, Joe Kindig, Joe Lionetti, Alan Miller, Sumpter Priddy, Brad Rauschenberg, Karol Schmiegel, Peggy Scholley, Cindy Siebels, Wes Stewart, and Joseph Tanenbaum.

In both the Anglo and continental European furniture traditions, strong baroque details persisted well into the 1750s. For mid-eighteenth-century furniture with classical baroque details, see Dean F. Failey, Long Island Is My Nation: The Decorative Arts &. Craftsmen, 1640-1830 (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1976), pp. 123, 127, 128, 131. Illustrated on these pages are a cabriole-leg high chest with fluted chamfered corners capped with heavy baroque shells, dating from 1740-1760; a corner cupboard from the 1725-1745 period, with engaged pilasters, arched doors, a stylized carved interior shell and geometric raised panels (multiplicity of panels being a baroque characteristic); a slightly later corner cupboard (1725-1750) with a carved shell; and a desk-and-bookcase with a double arched head dating from 1740-1760. With their bold architectural cornices and baroque proportions (approx. 1:1 height to width), New York kasten document the taste for early classical details in the Continental traditions. During the seventeenth century, immigrants came from the provinces of North Holland, Gelderland, Utrecht, South Holland, Friesland, and at least eleven provinces of the United Province. They also came from Germany (East Friesland and Oldenburg), Belgium (both the Walloon and Flemish provinces), France, the Schleswig-Holstein region, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. See Nan A. Rothschild, New York City Neighborhoods: The Eighteenth Century (New York: Academic Press, 1990).

Frederick Philipse I. (also "Ffrerick Vlypse" and "Flypsen") was born in Friesland. See John T. Faris, Historic Shrines of America (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1918), pp. 91-94 and Esther Singleton, Dutch New York (1909, reprinted, New York: Benjamin Blom, 1968), p. 46. For more on the Philipse family, see Harold Donaldson Eberlein, The Manors and Historic Homes of the Hudson Valley (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1928), pp. 82-98. The renovations and additions are discussed in John G. Waite, The Stabilization of an Eighteenth Century Plaster Ceiling at Philipse Manor (New York: New York State Historical Trust, 972), pp. 1-16.

Chipstone Foundation acc. file 1965.5. Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), p. 316. Charles F. Hummel, A Winterthur Guide to American Chippendale Furniture: Middle Atlantic and Southern Colonies (New York: Crown, 1976), pp. 26-27.

The Dictionary of English Furniture Makers lists only two eighteenth-century furniture makers named Hardcastle-Aaron, a cabinetmaker and joiner in Fewston, Harrowgate, York (1724-1755) and Robert, a carver "on the sunny side of Westminster Bridge," London (1763). All other furniture makers by that name were nineteenth-century tradesmen from Yorkshire (Geoffrey Beard and Christopher Gilbert, eds., Dictionary of English Furniture Makers, 1660-1800 [Leeds: Furniture History Society and W.S. Maney &. Son, 1986], p. 395). In execution, the carving resembles work associated with the shop of William Hallett (d. 1781) (see The Samuel Messer Collection of English Furniture, Clocks and Barometers, December 5, 1991 [London: Christie's, 1991], lot 63). The author thanks Morrison Heckscher for the reference to Hardcastle's inclusion in the list of freemen. In 1754 Hardcastle sued Thomas Davis for assault. In his petition to the court, Hardcastle described himself as a carver from New York (Henry Hardcastle vs. Thomas Davis, Court of Common Pleas of the City and County of New York, January 22, 1754, Municipal Archives of the City and County of New York). The advertisements by Hardcastle and Dwight are cited in Rita S. Gottesman, The Arts and Crafts in New York, 1726-1776 (1938, reprinted, New York: Da Capo Press, 1970), p. 127. Hardcastle was buried in Charleston on October 20,1756 (D. E. Huger Smith and A. S. Salley, Jr., eds., Register of St. Philip's Parish, Charles Town, or Charleston, S.C., 1754-1810 [Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971], p. 282). The author currently is researching a group of architectural carving that may be by Dwight or another apprentice or journeyman associated with Hardcastle.