Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. W. 8". (Courtesy, Frederick and Anne H. Vogel; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Gavin Ashworth.) Figures 1–8 demonstrate the consistency of the English Chinese Scholar pattern and suggest the types of plates and vessels on which it survives. The man wears a robe and unusual headgear—perhaps a feather, a floppy hat, a turban, or a single strand of hair. Sketchily painted in blue or purple on a white tin-glazed ground, he is surrounded by spiky bushes, budding branches, and craggy rocks. The horizon descends from one side or the other made up of jagged cliffs, clouds, or other indeterminate swaths of color.

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. W. 7 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. W. 8". (Courtesy, Frederick and Anne H. Vogel.)

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, John H. Bryan.)

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, John H. Bryan.)

Dish, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Private collection.)

Cistern, England, 1675–1695. Bleu persan tin-glazed earthenware. L. 10". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Candlestick, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Dish fragments, probably England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.) Excavated at the William Finnie House Site, Williamsburg, Virginia.

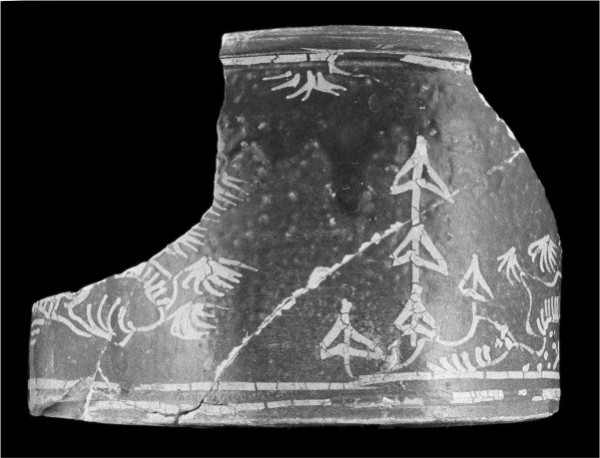

Meat pot fragment, England, 1680–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.) Excavated at the domestic site adjacent to the Chiswell-Bucktrout House Site, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Dish fragment, the Netherlands, 1670–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, New York State Museum, Albany, NY, New York State Department of Education; photo, Joseph Levy.) Excavated at Fort Orange, New York.

Dish fragment, the Netherlands, 1600–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware (majolica). (Courtesy, New York State Museum, Albany, NY, New York State Department of Education; photo, Joseph Levy.) Excavated at Fort Orange, New York. This dish is tin-glazed on the front but features a lead glaze on the back. The edges of this large fragment have been carefully ground down, suggesting that early owners discarded the rim, perhaps after part of it broke, and salvaged the central circular reserve as wall decoration.

Dish fragments, England, 1675–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Berwick Historical Society.) Excavated at the Lt. Humphrey Chadbourne Jr. Site, South Berwick, Maine, by Emerson W. Baker. The extensive Chadbourne estate was destroyed in 1690 by French and Native forces in the Salmon Falls Raid, an early encounter in King William’s War.

Lobed dish, England or the Netherlands, 1675–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Saco Museum.) Excavated at the Richard Hitchcock Homestead at Biddeford Pool, Maine, by Emerson W. Baker. Discolored by fire during the Salmon Falls Raid of 1690, this dish was owned by a family who, though much less wealthy than the Chadbournes, also owned several pieces of tin-glazed earthenware, among other imported goods.

Dish, China, 1573–1619. Hard-paste porcelain, decorated in the so-called Wan Li or kraak pattern. D. 15". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Vase, China, 1635–1645. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Gift of J. G. Fontein, 1924.)

Dish, China, 1645–1650. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 6 5/8". (Private collection.)

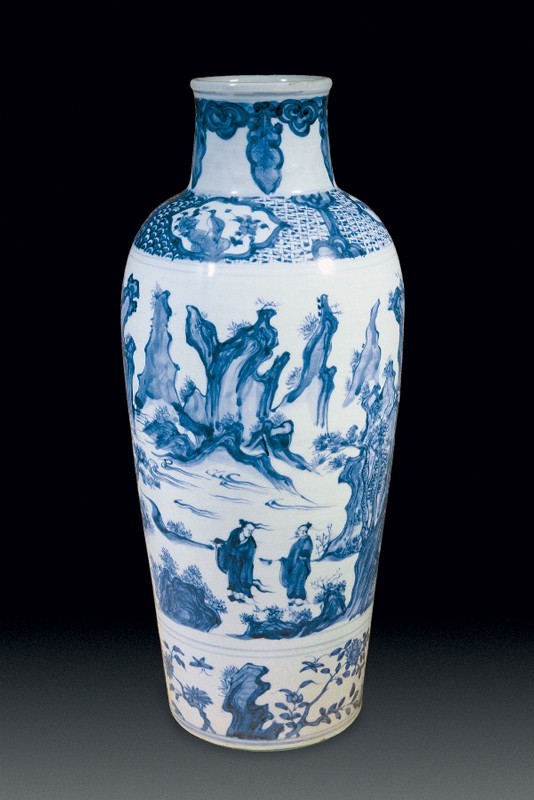

Vase, China, 1645–1660. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 15 3/8". (Private collection.)

Dish, China, 1650–1660. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 13 7/8". (Private collection.)

Dish, China, ca. 1670. Hard-paste porcelain, decorated in the Master of the Rocks style. D. 10 7/8". (Private collection.)

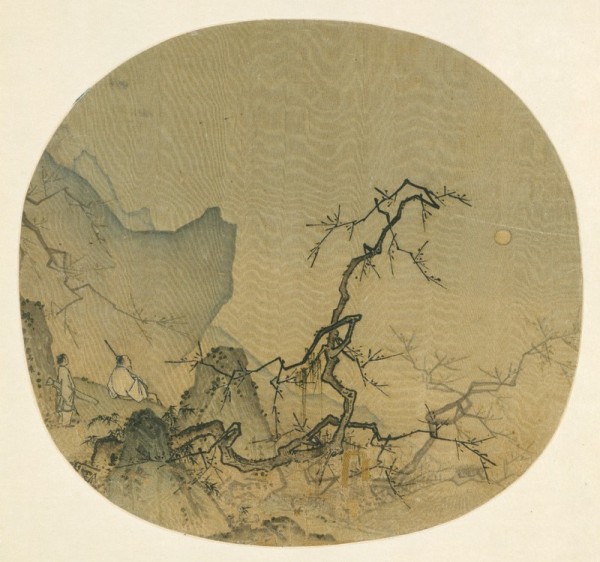

Ma Yuan (Chinese, active ca. 1190–1225), Viewing Plum Blossoms by Moonlight, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), fan mounted as an album leaf. Ink and color on silk. 9 7/8" x 10 1/2". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John M. Crawford Jr., in honor of Alfreda Murck, 1986 [1986.493.2].)

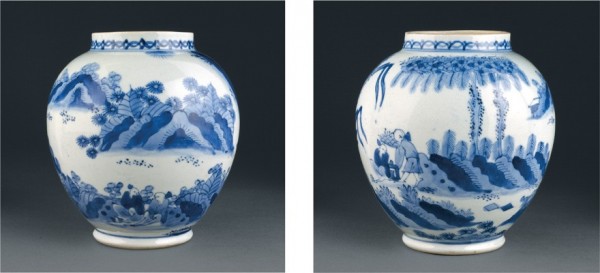

Jar, Arita, Japan, 1660–1680. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, Reitlinger Gift.)

Ewer, Japan, 1660–1680. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 10". (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, Reitlinger Gift.)

Dish, the Netherlands, ca. 1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Emmeline Reed Bedell for the Bradbury Bedell Memorial Collection.)

Dish, Nevers, France, 1670–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 16 1/8". (© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.)

Plate, probably Frankfurt, Germany, 1690–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Gabriele Flagg Pfeiffer.)

Jar, London, England, 1658. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, KAC/P1.) The reverse features the date, 1658, and the coat of arms of the Society of Apothecaries.

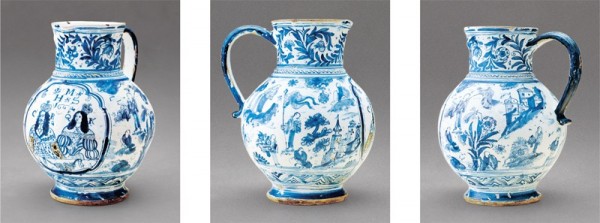

Jug, probably Southwark, London, England, 1662. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/2". Mark, inscribed on the shoulder: M / HS 1662. (Courtesy, Longridge Collection.)

Posset pot, London, England, 1669. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 5/8". Mark, inscribed on neck: 16 / S W / 69. (Courtesy, Castle Museum, Norwich.) The image on the right shows the Chinese Scholar motif.

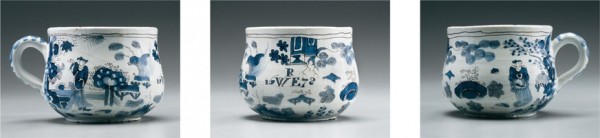

Caudle cup, London, England, 1678. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

Dish, England, 1673. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Longridge Collection.) Note the Chinese Scholar motif in every other reserve around the rim. A sherd that appears to have the same pattern around the rim was excavated in Williamsburg, Virginia, and is illustrated in Ivor Noël Hume, Early English Delftware from London and Virginia (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), p. 94, fig. XV.

Covered punch bowl, England, 1675–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection.)

Detail of the Chinese Scholar figure on the finial of the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 32.

Plate, London, England, 1675. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 3/8". Mark, inscribed on the reverse: C / TI / 1675. (Current location unknown.) Illustrated in Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Philip Wilson Publishers for Sotheby’s Publications, 1984), p. 34, no. 138.

Plate, England, 1679. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, John H. Bryan.) While the scene inside the central reserve of the Chinese Scholar plates is usually asymmetrical, the rims are generally symmetrical. Often one or two quickly painted lines mark the central horizon where the pattern of spiky foliage and amorphous rocks on the top rim meets the repeated pattern on the bottom rim. This plate is one in a set of three featured in Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware, p. 51, nos. 143a, b.

Mugs, London, Brislington, or Bristol, England, 1680–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. of mug (left) 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Longridge Collection.)

Porringer, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7". (Chipstone Foundation.) The Chinese Scholar, dipping his toe in the stream, wears a European-style shoe.

Plate, probably Southwark, London, England, 1630–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 11 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Charger, 1675–1700, England. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 15 1/4". (Private collection.) This large Transitional-style charger depicts a scholar’s rock, a dramatic geological formation traditionally used by Chinese thinkers to aid their contemplation of the beauty in natural chaos. This anglicized scholar’s rock has three symmetrical, graduated tiers with evenly spaced holes; this symmetry would have been an anathema to its original Chinese viewers. The overall composition of the charger is similarly hybrid. It features five sage figures whose details and composition capture the exotic feel of Chinese originals, but the overall arrangement of the scenes in relation to one another conforms to European conventions of symmetry. One figure occupies each of the four cardinal points, and the head of the fifth figure marks the exact center point of the whole plate. By applying imagery that would have been considered foreign and exotic by English observers onto the conventional four-pointed grid of European tradition, this charger and others like it offered newly fashionable chinoiserie in a format familiar to most consumers.

Flower vase, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Caudle cup, England, 1670–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4", D. 6". (Courtesy, Frederick and Anne H. Vogel.) The decoration on this caudle cup shows curious intercultural mixing. The scene derives from the Ming Transitional style and the figures are seated much like the Chinese Scholar, but they are dressed in English costume.

High chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1712–1725. Pine with japanning, probably by Nehemiah Partridge (case signed “Park”). H. 61". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Detail of a drawer on the high chest illustrated in fig. 42.

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, John H. Bryan.)

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, Inc.; photo, Amanda Merullo.)

Plate, London, England, ca. 1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of London.)

Plate, probably Brislington, England, 1675–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. W. 10 3/8". (Courtesy, Longridge Collection.) Plates with no rim decoration, like this one, tend to feature somewhat more individualized figures painted in greater detail. Allover patterns were relatively unfamiliar to English tastes and may have been influenced by Japanese imports.

Plate, England, 1696. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, John H. Bryan.)

Plate, England, 1699. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s, New York.)

Plate, England, ca. 1685. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Plate, England, 1675–1695. Tin-glazed earthenware. W. 7 7/8". (Courtesy, Longridge Collection.)

Jacobus Houbraken, after Sir Peter Lely, Sir William Temple, line engraving, published by J. and P. Knapton, 1738. Plate 14 5/8" x 9 3/8". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, London, given by Sir Herbert Henry Raphael, 1st Bt, 1916. NPG D19408.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1700. Maple and cane. 50 3/4" x 27". (Chipstone Foundation.)

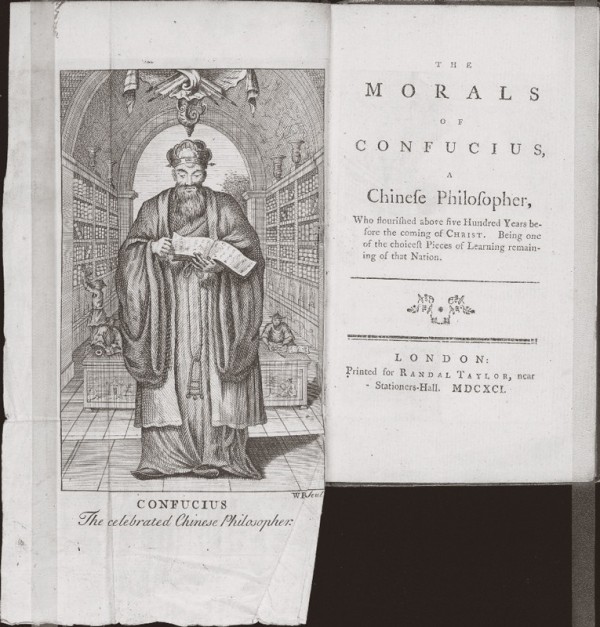

Frontispiece, The Morals of Confucius (London: Printed for Randal Taylor, 1691). (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Monteith, England, ca. 1690. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Chipstone Foundation.)

Monteith, George Garthorne, London, England, 1688. Silver with flat-chased decoration. D. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, purchase, Virginia Booth Vogel Acquisition Fund.)

Detail of the monteith illustrated in fig. 56.

The image of a robed figure seated in a scrubby landscape appears on hundreds of surviving English tin-glazed earthenware plates and vessels made between circa 1675 and 1695 (figs. 1-8). This exotic-looking pattern was created by potters in England to mimic the expensive porcelain imported from China and Japan and the similar Dutch copies flowing in from the Continent. No period term for the pattern is known, so historians traditionally have called it “Chinaman-in-grasses” and have recently updated the name to “Chinese-figure-in-grasses” or “squatting Chinese figure.”[1] A new, more precise name—“Chinese Scholar”—offers a better understanding of this pattern’s ultimate source in the narratives found on late Ming dynasty porcelain.[2] Spread by an extensive system of global trade, the image of a robed man in a wooded landscape originated in China and was then copied by potters in Japan, the Netherlands, and, ultimately, England. Through this process of visual translation, it was transformed into a hybrid pattern whose mixture of exotic novelty and subdued familiarity gained great popularity among seventeenth-century English consumers just becoming conscious of Asian aesthetics.

The Chinese Scholar pattern’s widespread popularity throughout English settlements on both sides of the Atlantic and its compositional consistency over a twenty-year period make it a particularly potent source for exploring the English imagination during a time of great cultural change. The last quarter of the seventeenth century saw not only dramatic turnover in the monarchy but also enormous population growth in London and the establishment of promising trading posts in India and the Americas. With high prospects in trade and empire, the British people began to see themselves as viable players on the global stage. This shifting worldview altered trade, class relations, and aesthetic tastes throughout England and its colonies. Ceramic wares with the Chinese Scholar pattern were among the most popular decorative items owned during this time and can offer important insights into the era when read in the context of three major cultural shifts.

First, the Chinese Scholar pattern’s free-flowing composition marks an early moment in the shift in English tastes from the order of the baroque toward the asymmetry and exotica of the rococo. Potters copied imagery from imported Asian porcelain as part of the pan-European fascination with Asian design that exploded in the late seventeenth century. Examined in relation to the writings of Sir William Temple, the first Englishman to praise Chinese asymmetry, the Chinese Scholar pattern emerges as an important early step toward creating the hybrid style known today as chinoiserie.[3] Ignorant of what the Chinese scholars and their accessories symbolized in their original contexts, English potters borrowed the images piecemeal, simplified them almost beyond recognition, and added them to conventionally Western forms such as drinking vessels, plates, candlesticks, and flower vases. Thus codified into a generic symbol of Eastern exoticism, this simplified image of a Chinese scholar spread throughout English settlements.[4]

Second, the Chinese Scholar pattern can be seen as part of a common visual language shared among English merchants and their customers all around the Atlantic Rim. Many of the merchants and the professionals who served the burgeoning port cities in North America and the Caribbean may have associated the Chinese Scholar wares—their blue-and-white decoration as well as the pattern’s content—with the English mercantile endeavor that was stretching not only east but also west. When considered in its American context, the Chinese Scholar pattern highlights both the extent of international communication around the Atlantic Rim and the shifting national allegiances of a quickly changing marketplace.

Third, English opinions about Asia were changing rapidly with an influx of information and images. Travel accounts and trade goods exposed people to unfamiliar religions, philosophies, and aesthetics, and the English people began to reimagine themselves within an ever-expanding world. The Chinese Scholar pattern thus offers a glimpse into popular notions about China and suggests a simultaneous fascination with and condescension toward the far-off country. The Chinese Scholar pattern’s assimilation of Asian aesthetics into European conventions preserved the newness of the image but also created prejudices that presaged the cross-cultural interactions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Archaeological evidence of the Chinese Scholar pattern in American colonial contexts poses difficult questions related to production, distribution, and origin. Sherds with the Chinese Scholar pattern and related imagery have been excavated along the coast of Maine; at Fort Orange, New York; Williamsburg, Hampton, and Jamestown, Virginia; St. Mary’s City, Maryland; Port Royal, Jamaica; and other American merchant cities (figs. 9-14). While many of the sherds represent the products of English potteries in London and Bristol, others were made in the Netherlands, France, and German-speaking regions of northern Europe. Differentiating between English and Continental versions is extremely difficult, and future research might create typologies to identify the origins of similar pieces. This essay, however, traces the appearance of the specific Chinese Scholar pattern and suggests the initial insights that can be gained by thinking about why this pattern—whether made in London, Bristol, or the Continent—was of such interest to English consumers in the late seventeenth century. This particular configuration of a lone Chinese figure in a scrubby Walandscape played an important role in the perception of China in the English popular imagination.[5]

The Original Chinese Scholars

The Chinese Scholar pattern ultimately derives from Chinese porcelain of the early seventeenth century, but the pattern passed through several cultural filters before appearing, much altered, in England. During the first half of the seventeenth century, porcelain arriving in England mostly came through the Dutch East India Company (or VOC). The pattern most commonly imported at first featured blue-on-white hand-painted patterns with rectangular panels alternating in size decorating the rim, and foliage, birds, and other natural motifs in the center. Developed specifically for export, this pattern was called “Wan Li” after the sitting Ming emperor (1572–1620) (fig. 15). Many Europeans also called it kraak ware, after the Portuguese carrack ships that had first transported porcelain into Europe.[6]

Starting in the 1630s, the exported patterns began to change due to shifts in China’s pottery industry. For centuries, the potteries in Jingdezhen primarily had fulfilled porcelain commissions for the Ming imperial court. Facing threats of military attack from the northern Manchus, the emperor redirected funds earmarked for porcelain production toward defense. Forced to find new buyers outside the court, the Jingdezhen potters began producing for China’s educated elite and prosperous merchants. Their new porcelain featured landscapes with tall craggy mountains, streams, clouds, trees, and human figures from folk tales, novels, and legends (fig. 16). The potters largely copied these motifs from popular paintings and woodblock prints. Known today as Ming Transitional ware, this is the porcelain that was imported in great quantity into Europe and sparked the craze among the wealthy for collecting blue-and-white “china.”[7]

The change in taste for porcelain decoration was part of a larger cultural transformation in Chinese society that shifted power outside the imperial court system and opened up ancient aesthetic traditions to new audiences. Warring factions within the Ming imperial court were disrupting traditional power structures, creating a period of unprecedented socioeconomic fluidity. Due to inflation and expanded international trade, ambitious merchants and the educated elite were amassing large fortunes and gaining social power in the vacuum left by the weakened Ming court. To solidify their newfound status, many of these men began imitating the aristocratic lifestyle, often by collecting art that featured iconography formerly known only in higher cultural circles. Many developed special interest in the paintings of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), widely regarded today as the zenith of landscape realism. To fulfill demand for these ancient paintings, Ming painters and woodblock printers resurrected the old-style landscapes, often passing off their own work as antique. During the same period, painters also began copying more mundane scenes from folk tales, novels, and plays that featured recognizable characters in animated scenes. The porcelain painters responded to the changing tastes of their new clientele and began decorating their wares with similar landscapes and narrative scenes (figs. 17, 18).[8]

Another type of imagery that became popular in late Ming painting—on scrolls as well as on porcelain—portrayed the lifestyle of the Chinese scholar. For centuries the prestigious imperial education system had culminated in academic examinations that allowed those who passed to serve the government in positions that ensured a certain degree of comfort and power. The robed hermit-scholar alone in his pagoda-roofed study surrounded by accoutrements of learning had been a common trope in painting, poetry, and familiar lore for centuries. In most cases the scholars were anonymous, identified by recognizable motifs—scrolls, brushes, brush holders, and inkwells. Pine, prunus, and bamboo branches, collectively known as the “Three Friends of Winter,” also connoted the scholar’s lifestyle because they symbolized the revered traits of flexible strength, perseverance, and uprightness. In the 1630s, however, the civil-servant scholar-gentry educated in this system began to lose power as the late Ming emperors, threatened by Manchu uprisings in the north, were increasingly influenced by palace favorites and insider politicking. Many people lamented the loss of this long-standing tradition of academic rigor and worried about the future of the Ming dynasty. In this atmosphere of political uncertainty, iconography related to the scholar’s study took on additional meaning. In paintings as well as on porcelain, hermit-sages became not only a reference to the stability and tradition of bygone eras but also a political statement against the current imperial court (fig. 19).[9]

Among the many scholar motifs that appeared on Ming Transitional porcelain, one in particular may be the ultimate source of the Chinese Scholar pattern in England. Anonymous Ming porcelain painters often portrayed a single scholar seated on a cliff or outcropping, looking over a misty landscape with craggy rocks. Today the pattern is generally called “Master of the Rocks” (fig. 20). This popular image may have derived in part from the eighth-century poet Wang Wei, whose most famous verse reads: “I walk to the place where the water ends / and sit and watch the time when clouds rise.” Images of Wang Wei and other sages seated on the edge of a rock looking into an abstract emptiness appeared for centuries in Chinese art and were especially popular among the Song painters (fig. 21). As late Ming painters resurrected Song motifs, they generated renewed interest in Wang Wei’s ancient image, which may have helped inspire the Master of the Rocks pattern. During his lifetime, Wang Wei himself was a hermit farmer and remained closely associated with eremitic themes after his death. In the late Ming era, images of a lone seated scholar would have connoted not only the famous poet and the quality of Song painting but also the scholarly lifestyle that carried political resonance among the merchant elite. Some historians have also suggested that the image of a secluded natural retreat may have been especially appealing in a period of significant social upheaval.[10]

It is not entirely understood how Ming Transitional porcelain with the Master of the Rocks pattern and other scholar motifs came to be shipped to Europe by the VOC. Before the 1630s, Chinese merchants shipped only patterns developed specifically for export rather than patterns made for their own local market. It seems that as established trade networks broke down in the face of political turmoil, Chinese traders seized the opportunity to provide their wares—no matter their intended audience—to eager European shippers. Chinese traders already involved with inland networks of commerce, by which they supplied the domestic market, simply may have added the Dutch to their list of clients. The first shipment containing Ming Transitional wares left China for Amsterdam in 1634 and was described by a Dutch official in Taiwan as “a good lot of different porcelains of the old assortment and some new paintings with Chinese figures.” Ming Transitional porcelain proved highly profitable for the Dutch, who traded millions of pieces through their factories in Southeast Asia, India, and several regions in the Near East.[11]

Shortly after the first arrival of Ming Transitional wares in Europe, the supply was cut off. The northern Manchus finally toppled the Ming dynasty in 1644 and decades of civil war ensued. The imperial kilns at Jingdezhen and many other production centers were closed, and external trade dramatically decreased. Demand in Europe for blue-and-white had risen to such a frenzy, however, that the Dutch asked potters in Japan to imitate the “old Chinese porcelain” to which their customers had become accustomed. Prodigious scholarship over the last twenty years has revealed that most of the blue-and-white arriving in Europe in the middle decades of the seventeenth century was indeed Japanese rather than Chinese. At first the Dutch imported only small numbers of Japanese porcelain, but as the storehouses of Chinese wares became exhausted, the VOC encouraged the potters in Arita to expand production. Beginning in 1657 the VOC sent prototypes—Chinese Ming Transitional porcelain as well as their own delftware copies—to Japan to be re-created. In one shipment the Dutch also sent turned wooden vase forms for the Japanese potters to reproduce.[12]

Japanese copies of Ming Transitional wares included robed figures and rocky landscapes similar to those on the Chinese originals but in a freer painting style and with several telltale adaptations (fig. 22). Vertical bushes painted with spiky V-shaped strokes, sometimes described by modern historians as “bottle-brush” trees, seem to have been a Japanese interpretation of Chinese foliage. Japanese-style karakusa scrolls appear alongside European-looking floral borders. The forms of the Japanese vessels generally adhere to Dutch tastes for Western jars, ewers, bowls, and plates (fig. 23). Some examples survive, however, with distinctively Chinese forms, such as the tall and thin rolwagen vase and the double-gourd-shaped vase. For about twenty-five years, the trade between the VOC and Arita potters created a distinctive aesthetic, filtering Chinese imagery through the tastes of Dutch merchants and the artistic impulses of Japanese potters.[13]

While the Dutch merchants were distributing Asian porcelain throughout northern Europe, their local potters responded quickly to the rising popularity of blue-and-white ceramics by creating copies of their own. Potters in Haarlem, Delft, and Rotterdam had been copying Italian maiolica for decades by applying an opaque white tin glaze and colorful oxides to their local earthenwares. In the second quarter of the seventeenth century, they began to shift their decorative schemes from baroque imagery rendered in blue, yellow, orange, and green to Asian-inspired scenes painted primarily in cobalt-blue underglaze. These approximations of imported porcelain boasted playful mixes of kraak and Ming Transitional patterns such as the dish illustrated in figure 24. Dutch manufactories grew in size and number and began supplying chinoiserie tin-glazed earthenware to the middle-class burghers as well as to customers outside the Netherlands.[14]

Potters in other parts of Europe quickly followed suit by copying the Dutch “delftwares.” By the 1650s French potters in Nevers turned their attention to Holland’s Asian-inspired designs (fig. 25). In 1666 a French potter set up a pottery in Frankfurt, and the taste for chinoiserie spread to potters in Hamburg as well (fig. 26). All of these European pottery-making centers copied Ming Transitional wares in much the same way. They all featured robed figures with unusual headware wandering in exotic landscapes. Many have distinctively abstracted clouds made from horizontal swaths of alternating color curling up on one end. Europeans also generally copied the Japanese “bottle-brush” tree design.[15]

Immigrants and imports from these Continental production centers took to England the technology and inspiration for tin-glazed earthenware decorated after Ming Transitional patterns. London enjoyed unprecedented expansion in the last quarter of the seventeenth century thanks to England’s developing trade networks and its role as a refuge from increasing hostility toward Protestants on the Continent. Among the many skilled artisans who helped make London the largest city in Western Europe were potters from Holland, an influx that contributed to the sudden appearance of chinoiserie in English pottery. Continental potters set up shops in London in the early seventeenth century and quickly copied the kraak patterns they had been making at home, often onto such traditional European forms as the wine bottles and jugs attributed to immigrant potter Christian Wilhelm. By the late 1670s, potters in Southwark and Lambeth were all making chinoiserie wares using the techniques they learned in Europe and copying the Dutch imports arriving in London. Immigrant potters in Bristol and Brislington were exposed to similar wares and created patterns very similar to those made in London.[16]

Chinese Scholars in England

Potters in England derived their techniques and decorative schemes from Dutch and Continental sources, but they adapted the Chinese aesthetic quite differently from their European counterparts. They copied the various landscapes and figures taken from Ming Transitional wares, but they also developed a single simple image—the Chinese Scholar pattern—and replicated it over a twenty-year period starting about 1675. The plates and vessels in figures 1–8 demonstrate the remarkable consistency with which English pottery painters reproduced this pattern. The single robed figure appears again and again seated by a stream or rock looking into an abstracted landscape. On many plates, he appears again on the top and bottom of the rim. While Dutch and other Continental potters also simplified Chinese imagery and created figures and compositions similar to the English Chinese Scholar pattern, their compositions did not have the same degree of consistency from piece to piece as the English versions.

In England, Ming Transitional–type decoration was copied, modified, and then codified into the Chinese Scholar image that gained considerable popularity—a process that makes its meaning among English consumers especially potent. The earliest English-made Ming Transitional–type scenes seem tentative and secondary. They appeared first as backdrop decoration for large central armorials or commemorative reserves. A large drug jar dated 1658 features the coat of arms of the Society of Apothecaries, large blue-and-white floral sprays, and several standing Chinese figures on the walls of the jar (fig. 27). A jug dated 1662 features similar Transitional-type figures surrounding a portrait commemorating the marriage of King Charles I to Catherine of Braganza (fig. 28).[17]

In the 1660s and 1670s the Transitional style became more deliberate and primary, appearing as the dominant decoration on posset pots and caudle cups. Several posset pots survive with Transitional-type figures and the early date of 1669 (fig. 29).[18] Still meant as a backdrop to the commemorative monogram, the chinoiserie decoration dominates these pieces to a greater degree than on the earlier drug jar or jug (see figs. 27, 28). Many similar examples were made in the 1670s and 1680s (fig. 30). This emergence of Transitional-type decoration as a backdrop for commemorative armorials and initials helps identify chinoiserie from its first moments as a style used for public display.

The solitary seated figure that eventually became the Chinese Scholar pattern first appeared as small details within more elaborate Ming Transitional–style decoration. An enormous dish dated 1673 features the coat of arms of an unidentified London city livery company in the central reserve and a rim with eight oval reserves in a pattern somewhat similar to the earlier kraak patterns (fig. 31). Every other oval reserve bears a landscape scene featuring bushy slopes with two-tone highlights, tall, spiky “bottle-brush” trees, and an abstracted Chinese figure who seems to be dipping his toe into a brook.

A very similar Chinese figure was painted on the finial of an enormous covered punch bowl made in London about the same time (figs. 32, 33). While nearly one quadrant of the punch bowl features the heraldry of another London city livery company (possibly the Company of Leatherers), all of its other surfaces feature intricately painted scenes of Ming Transitional–style figures in an exotic landscape. The figure on the finial (see fig. 33) appears to be dipping his toe into a stream in much the same way as the figures on the charger in figure 31. Again, this simple image has a marginal role in the overall decorative scheme and appears more sketchily painted than the more central figures. While the punch bowl is not dated, its painting style and heraldic imagery are similar to those of the 1673 charger. Both objects feature simplified imagery inside the armorial shield, knight masks with the same two-tone twist above, and nearly identical floral spirals on either side of the shield. Further research might determine a link between the painter of these two pieces and those with similar motifs.[19] Regardless, the charger and punch bowl attest that in the 1670s one or several English pottery decorators painted the same image of a Chinese scholar-fisherman dipping his toe into a stream.[20]

Within a few years this toe-dipping Chinese scholar began making solo appearances as the primary decorative image on plates, mugs, and other vessels. The underside of a small plate is inscribed “1675” under the initials “C / T I” (fig. 34). On the plate’s face is depicted a seated figure dipping his toe into a stream surrounded by ill-defined rock outcroppings and plants with spiky foliage growing in every direction. This is the earliest known dated English plate featuring the codified Chinese Scholar pattern as the central decoration. The figure is repeated in miniature at the top and bottom of the rim, a composition that appeared regularly in the following twenty-five years except that the year and initials generally appeared on the front of the plate (fig. 35).

From the late 1670s through the 1690s the Chinese Scholar pattern appeared on huge numbers of undated plates and vessels made in London as well as Bristol and Brislington. Many painters simplified the toe-dipping scholar-fisherman even further, into an inactive seated figure in profile. In some cases it looks as if the figure is extending his foot but the painter omitted the stream. In others, the figure makes no overtures toward being a fisherman at all and merely sits cross-legged on a ledge, much like Wang Wei’s cloud-viewing scholar. Given the convoluted route by which the imagery came to England, it is likely that any associations with the poet Wang Wei, or even with the academic success and morally upright hermeticism associated with these images in China, would have been lost on English viewers (figs. 36, 37).[21]

Because of this lack of understanding, the Chinese Scholar pattern as well as the ceramic objects on which it appeared should be considered cultural hybrids. From the first moments that English potters began to copy imported porcelain, they did not understand the symbolism of the Chinese designs and tended to mangle meaning and borrow motifs at random (fig. 38). Likewise, throughout the century Chinese narrative content generally was lost in the English versions, leaving only the decorative details that so fascinated Western consumers: anonymous Chinese people dressed in loose, flowing clothing and unusual headdresses wandering through alien landscapes.[22] In addition to decontextualizing Chinese symbols into generically exotic motifs, potters anglicized them further by incorporating them into familiar conventions of domestic design. On many pieces, potters worked Asian motifs into traditional European systems of symmetry (fig. 39) and often applied these foreign images onto familiar European ceramic forms. Instead of throwing Asian-inspired double-gourd vases or other shapes, potters continued to make conventional caudle cups, tankards, meat pots, and flower vases (figs. 40, 41). By combining exotic imagery (however altered or tamed) with familiar forms and systems of decoration, these potters created hybrid objects palatable to most English consumers. Silversmiths and furniture makers employed similar tactics, and all of their products helped build a market for chinoiserie (figs. 42, 43, 56).[23]

The composition of the Chinese Scholar pattern seems to have been most consistent on plates, remaining remarkably formulaic whether the plates were circular, octagonal, or lobed. The scholar sits in the central reserve and two miniature versions appear at the top and bottom of the rim, at twelve and six o’clock. The posture and details of the seated figures vary from piece to piece, but the miniature versions always replicate the central figure. Rarely are the miniature versions reversed (fig. 44). At least one known plate with four miniature scholars around the rim survives (fig. 45). The first potters to add miniature scholars to the rim decoration may have been looking at the scholar-fishermen inside the oval reserves on large chargers like the 1673 example in figure 31, a suggestion supported by a small plate whose miniature scholars are outlined as if inside Wan Li–type oval reserves (fig. 46).

In the 1690s the Chinese Scholar pattern began to change as the pottery painters’ repertoire widened. After the new Qing dynasty was firmly established in China, the Jingdezhen kilns reopened in 1683 and both the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Company began importing vast amounts of Chinese porcelain again. These new wares, with Chinese scholars and popular characters painted in bright green, yellow, and red enamels, offered many new scenes to copy. Robed scholars continued to appear on English ceramics, but the imagery became less formulaic (fig. 47). This shift was gradual, which makes it difficult to pinpoint when the pattern stopped being produced. Three floral-bordered plates bearing the year 1687 have been cited as the final dated versions known, but several plates with later dates bear variations on the pattern, suggesting its influence continued well into the 1690s. One surviving plate features the miniature scholar figures at the top and bottom of the rim, but the traditional central figure has been replaced with the prominent date of 1696 and the initials “B / I M” (fig. 48). A number of plates dated 1699 feature less animated seated figures, geometric borders unrelated to the chinoiserie aesthetic, and plants painted with dabs instead of spiky lines (fig. 49).[24]

Filtered through an elaborate international system of trade and manufacture, the Chinese Scholar pattern that appeared in England barely resembled its original Chinese source. Many of the English potters never saw the Chinese models but were copying Japanese versions or Dutch delftware copies. Their unfamiliarity with Chinese costume, artistic conventions, and symbolism caused many English potters to create Chinese Scholars that are barely decipherable as human figures (figs. 50, 51). These distorted translations of Ming Transitional motifs are examples of what art historian George Kubler called “historical drift.” Replications of any object made over a long period of time or in locations distant from the source inevitably become different from the originals. Kubler argued that such drift would cause “diminishing quality” in any series of replicas, and, by conventional aesthetic standards, the Chinese Scholar wares do pale in comparison with the Chinese originals. The clay bodies are thick, the glaze is lumpy, and the imagery less precise. Today’s historians, however, can regard the Chinese Scholar wares not as lesser copies of the Chinese originals but rather as manifestations of the frenzied excitement about international discovery and communication that overtook the English public in the late seventeenth century.[25]

The Chinese Scholar and Sharawadgi

In this time of great change the Chinese Scholar pattern can offer cultural insights when studied through three cultural lenses. First, the asymmetry of the Chinese Scholar pattern—however hybrid or tentative—suggests an early role in the aesthetic shift toward the rococo. In the 1670s the rectilinear rigors of Palladian design were just beginning to give way to more playful curvature and whimsy, a shift that eventually led to eighteenth-century rococo styles. Among the first English theorists to write about the allure of asymmetry was Sir William Temple, a retired diplomat and gentleman-botanist who published Upon the Gardens of Epicurus in 1685 (fig. 52). While his treatise primarily provided suggestions for organizing the long allées of trees and carefully trimmed parterres in most of the formal gardens in this period, his final paragraphs praised a completely different kind of beauty. He conceded that natural beauty in gardens might be increased by emphasizing the pleasing irregularity inherent in nature. Temple had heard that this agreeable lack of order characterized Chinese gardens and he introduced the Chinese word for it to his English readers:

[Their] greatest reach of imagination [among the Chinese] is employed in contriving figures, where the beauty shall be great, and strike the eye, but without any order or disposition of parts that shall be commonly or easily observed: and, though we have hardly any notion of this sort of beauty, yet they have a particular word to express it; and, where they find it hit their eye at first sight, they say the sharawadgi is fine or is admirable, or any such expression of esteem.[26]

Sharawadgi, according to Temple, refers to the pleasant surprise enjoyed when the beauty of a natural scene appears unexpectedly and creates a moment of serendipity in the landscape. The word is as mysterious as its effect. Linguists have not convincingly linked sharawadgi to any Chinese or Japanese homonym. Temple either anglicized a genuine Asian word beyond recognition or made it up to represent a foreign idea.[27]

Temple’s writing is generally regarded among landscape historians as the first philosophical seed of what was to grow into the romantic English garden. The term sharawadgi became used widely throughout the eighteenth century to refer to the meandering paths and faux-natural tree groves that characterized the gardens designed by Lancelot “Capability” Brown and others for aristocratic country houses as well as public grounds. A close look at Temple’s text reveals that he wrote about sharawadgi not only in Chinese gardens but also as a quality in other Asian artifacts. Few design historians have considered the significance of Temple’s observations about man-made objects. After defining his foreign-sounding word, Temple continued: “And whoever observes the work upon the best India gowns, or the painting upon their best screens, or porcelains, will find their beauty is all of this kind; that is, without order.”[28] According to Temple, sharawadgi appeared not only in Chinese gardens but also in the designs on cotton textiles painted or printed in India, lacquer from China and Japan, and porcelain of all kinds. Certainly Ming Transitional porcelain boasted a beauty “without order”; diagonal lines made by tree limbs, craggy mountains, and flowing streams led the viewer’s eye wandering over the surface of the vase or bowl in the footsteps of the Chinese sages. This composition placed them wholly outside the regular conventions of European Palladianism.[29]

Like the authentic Chinese porcelains, the English Chinese Scholar pattern also captured sharawadgi in its descending cliffs, curving stream beds, and ambiguous swaths of color in the sky. The two scholars sitting at the top and bottom of the rim on many Chinese Scholar plates might not be readily apparent until the viewer’s eye stumbles onto them after meandering the plate’s surface. This curving and serendipitous gaze is not unlike the “wanton kind of chase” that aesthetic critic William Hogarth praised in his influential 1753 work, The Analysis of Beauty. The perfectly swooping “line of beauty” that he advocated in painting as well as objects characterized eighteenth-century rococo in the English taste. Even though Temple had defined sharawadgi in 1685, his ideas about asymmetrical garden design were not manifested until Alexander Pope built his gardens at Twickenham in 1714. Likewise, the asymmetry and hybrid exoticism that appeared on the Chinese Scholar wares coincident with Temple’s essay predate by several decades the playful expression and exotic content that characterized Hogarth’s era. Perhaps the early popularity of the Chinese Scholar pattern opened the door not only to exotic imagery but also to the S-curves, gathered ruffles, and asymmetrical floral sprays found on ceramics, wallpapers, textiles, and other rococo-style objects of the eighteenth century.[30]

The Chinese Scholar and the English Merchant

While the emergence of Chinese Scholar plates and vessels marks an early moment in the shift toward the rococo style, it also suggests a shift in the marketplace. These objects are among the earliest in a group of relatively inexpensive goods newly produced for the growing numbers of successful English merchants. England’s greater concentration on shipping and packing raw materials as well as London’s population growth allowed a great number of people to support themselves by turning over capital in the cities rather than working the land in the countryside. A new group of merchants created significant wealth for themselves and their nation by moving domestic and imported goods between English ports around the world. These merchants and the professionals who served them constituted a “middle station” or “middling sort” who not only produced profitable goods but also themselves became a new market for fashionable housewares and luxuries previously reserved for the aristocracy.[31]

The growing demand among the middling sort for relatively affordable stylish housewares contributed to growth in tin-glazed earthenware manufacture. Like professional weaving operations and book printers, English potteries had first appeared in the early seventeenth century and then expanded enormously to fulfill the demand from new markets. This increase in tin-glazed earthenware potteries is not remarkable for any particular technical innovation (they relied on Renaissance traditions of maiolica). Their growth instead suggests the shifting attitudes at this time toward ceramics among the nonelite. No longer seen as exclusively utilitarian, ceramic housewares were regarded as items for display and the articulation of taste.[32]

Similarly, chinoiserie also underwent a shift in this period from being available only to the wealthy to being produced for the nonelite. Design historian Dawn Jacobson argues that chinoiserie arose in England primarily outside elite settings in part because of its cool reception within the antiluxury Commonwealth government, which ruled England during the style’s early influential years (1649–1660). Even though Charles II was comparatively decadent, the English court did not commission outrageous chinoiserie monuments like the porcelain palace that King Louis XIV of France built for himself in 1670 on the grounds of Versailles. Without strong royal patronage, English chinoiserie at this time offered a distinctly midlevel appearance.[33]

One of the most popular types of chinoiserie tin-glazed earthenware in England, the Chinese Scholar pattern expresses the mercantilist trade system that revolutionized the economy of seventeenth-century Europe. At the core of the mercantilist system was the realization that nonelite desires for luxury goods could be exploited for economic gain. Any nation could succeed by regulating tariffs and exporting more than it imported, a tactic pioneered by the Dutch. Design historian Glenn Adamson has demonstrated that English- and American-made caned chairs, introduced in the 1660s and popular into the eighteenth century, can be read as mercantilist objects because of their novelty, formal emphasis on surface display, relative impermanence, and their similarity to Dutch imports (fig. 53). Much the same can be said of Chinese Scholar plates and vessels.[34]

Similar to the caned-chair makers, potters copying Dutch products thus reduced the number of goods imported from the Continent. Despite calling the tin-glazed earthenwares “delft”—hence emphasizing the Continental source of the tradition—the English may well have seen the success of their burgeoning pottery industry as beating the Dutch at their own game. Another similarity between the Chinese Scholar pattern and caned chairs was their shared emphasis on façade and artificial display. The carved crests of caned chairs could be read clearly only straight-on. The visual power of the Chinese Scholar plates also derived entirely from the frontal views of their surface decoration. While that emphasis was by no means new—decorative plates had been used for interior display for centuries—the quantity of their manufacture and the new distribution within the middling sort suggest an important new emphasis on façade and direct display within a burgeoning consumer culture.[35]

In some ways, the Chinese Scholar pattern may have emblematized mercantilism even more overtly than caned chairs. Its novelty stemmed not just from its similarity to Dutch goods or its formal emphasis on surface but also from its exotic content. By the success of the English East India Company, the prime agent responsible for British mercantilism itself, English eyes were offered intriguing new views of an unfamiliar culture. Like the caned chairs that suddenly began to appear in large numbers in the homes of the nonelite, chinoiserie tin-glazed earthenware—Chinese Scholar items especially—can be considered harbingers of a new era, made in the spirit of England’s new identity as a rising mercantilist power.

When considered in the American context, the Chinese Scholar pattern can be seen as part of a common visual language shared among English merchants and their customers throughout their geographically distant settlements. Since the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660, the government had renewed its interest in its North American colonies as potential trade centers. With a growing emphasis on maritime trade, the Atlantic economy offered considerable opportunity in these years and attracted investors as well as immigrants. Even New England, a region originally settled for religious idealism rather than trade, had a distinct merchant class by the 1670s. The thousands of English people who settled on Atlantic coastlines in North America and the Caribbean shared a common mercantilist identity with their counterparts back in England. Studied in recent years as members of a transatlantic community tied together by the solidarity of intercoastal trading, English merchants purchased new goods and developed a specific aesthetic that affiliated them with a nation mining the world—from China to Virginia—for fashionable and profitable commodities. Chinese Scholar wares owned in North America, then, can be seen as visually linking merchants not only to English tastes but also to their country’s trade ambitions in the East.[36]

These merchant allegiances among colonial settlers in North America become more complex when the archaeological evidence of the Chinese Scholar pattern is considered. Late seventeenth-century colonial sites rarely yield Chinese export porcelain sherds, but they do contain large quantities of Ming Transitional tin-glazed earthenware. Sherds have been found not only from England but also from the Netherlands; it is reasonable to assume that examples from France, Germany, Italy, and Spain also arrived in North America. A number of intact Ming Transitional–style pieces also survive, including a charger probably made in the Netherlands or Germany with an associated history of belonging to Joseph Waterman of Marshfield, Massachusetts. While the large volume of chinoiserie-style tin-glazed earthenware found in the colonies suggests open international exchange of ceramic goods, in reality the English Parliament progressively limited the trade of foreign goods among English-run ports in North America with a series of Navigation Acts in 1650, 1661, and 1672. Despite these regulations, Continental luxuries appeared in American cities, usually smuggled by merchants from all over the Atlantic world. Consumers in the Americas probably did not care about (or even necessarily know) in which country their Chinese Scholar wares were made. Trumping their ties to the English government’s rules were their own identities as participants in a growing global network of trade now stretching all the way to Asia. Perhaps many English settlers who bought Chinese Scholar pattern wares from the Netherlands and Germany identified more strongly with their colonial neighbors and their shared commitment to trade than with the Parliamentary protectionism of their own government.[37]

The Chinese Scholar in the English Imagination

Even as the Chinese Scholar pattern contributed to the stylistic shift toward Asian-inspired asymmetry and a shared visual language among merchants, it can also be seen as part of England’s widening worldview. The last quarter of the seventeenth century saw a dramatic resurgence in the English economy, rebounding after the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674). The English East India Company was now expanding its trade of Indian textiles, successfully securing factories in South Asia. At the same time, more merchants were venturing westward to North America to trade in lumber and furs. As the merchant class became wealthier, more well traveled, and better respected within its own communities, the English public began to see themselves as powerful players in a suddenly expanding world. They envisioned the Dutch, French, and Portuguese as long-standing rivals. The Chinese, by contrast, remained an unknown people about whom the English imagination was quickly piqued. This period of rapid change was the beginning of what historian Joseph Rykwert has called “the domestication of the marvelous.” Rising to popularity during this important time of change, the Chinese Scholar pattern helps reveal the English public’s complex and ambiguous outlook on Chinese culture.[38]

Throughout the seventeenth century, cultural interactions between Europe and Asia were driven by economic aspirations but also by a certain degree of popular curiosity. Twentieth-century postcolonial theorists led by Edward Said have critiqued the discourse by which the British and French devalued the people in colonized regions in order to bolster their political might with cultural power. More recent writers have suggested that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the early interactions between East and West were far less prejudicial than in later years and involved considerable give-and-take. In the 1670s most British people had little understanding of the geography of China, India, Japan, and other Asian regions let alone the cultural traditions. Most British consumers entertained wildly imaginative (and mostly ignorant) ideas about far-away “Cathay.” “India,” “China,” and “Japan” were often used interchangeably to describe anything even vaguely exotic, whether a genuine import or a locally made imitation. The attitudes of colonialist superiority criticized by Said had not yet fully taken hold, and most people pursued their curiosity more than a sense of imperialism.[39]

Within this early period of relative openness came great admiration among some Europeans for Chinese culture, and especially for Confucius (551–479 B.C.) (fig. 54), the most prominent Chinese personage in the minds of the English people in the late seventeenth century. In London, for example, booksellers in St. Paul’s Churchyard advertised Jesuit descriptions of China, including Father Couplet’s 1691 publication, The Morals of Confucius, a Chinese Philosopher, alongside other popular publications such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dr. Busby’s Greek Grammar.[40] The robed sage featured in the Chinese Scholar pattern may have evoked associations with this famous figure.

While some viewers might have connected the seated figure on the Chinese Scholar pattern with the religion and philosophy of Confucius, others could have regarded him as a symbol of ancient China’s progressive government and ethics. Chief among European proponents of Chinese thinking was German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who believed in the shared humanity of all people. Influenced by publications of Confucius’s writings in the 1680s, Leibniz praised the “social order” and “public tranquility” in China. Confucian emphasis on the thinking individual, Leibniz argued, enabled the Chinese to “surpass us . . . in practical philosophy” and to set up a society in which “men shall be disrupted in their relations as little as possible.”[41] For European observers who followed the progressive thinking of Leibniz and other humanists, China’s ancient civilization seemed to offer early modern Europe appealing traditions of equality and order. The hermit-sages in the Chinese Scholar pattern may have recalled for some viewers the disciplined vigor of China’s imperial examination system and its orderly, educated society. Seen in any English parlor or tavern, the image of a tranquil Chinese figure dressed in scholar’s robes might have signaled an awareness of, and respect for, Chinese ethics and government and, by association, the broad humanist cause.

While the Chinese Scholar pattern gained popularity from this widespread admiration of Confucian morality and society, it also reflected European prejudice and propagated some of the degrading caricatures that came to dominate eighteenth- and nineteenth-century chinoiserie. Conceding that Chinese philosophy was once far ahead of European thinking, only now being selectively mined by Western philosophers, many Europeans saw China as a culture in decline, left to bask in its once and lost glory. The Chinese Scholar image bolstered that view. The figure sits alone, perhaps pondering the natural world. Hanging his head in noble thought or silent despair, the figure could have been seen as a symbol of China’s great past captured now by European pottery painters. The hybrid nature of the pattern, which presents an Asian scene through the eyes of European artisans, is an early example of the cross-cultural visual discourse that created the national and racial identities criticized by Said and other postcolonial theorists.[42]

The perception that Chinese people were passive, which became common later in the eighteenth century, may have gained an early foothold with the Chinese Scholar wares. Design historian Stephen Parissien has argued that passive representations of Asian men arose in the 1680s just as the immediate threat of Eastern enemies began to dwindle. The Ottoman Turks, who had posed a threat to landholdings and Christianity in Eastern Europe for generations, began to lose power. Defeated at Vienna in 1683 and again in Hungary in 1687, the Turks finally lost Belgrade in 1688, beginning several decades of military success for the Europeans in the Middle East. As reflected in visual imagery as well as in characters on the London stage, Asian peoples in the English imagination changed from being threatening—if somewhat intriguing—distant aggressors to being subdued, somewhat effeminate inheritors of an ancient civilization in decline. In keeping with this larger trend, the Chinese Scholar sits passively, calmly observing a stream or rock. Missing are the tall mountains and looming tree boughs that lent genuine Ming Transitional scholars their intellectual and moral authority. Instead of resembling a powerful warrior or mythical hermit-sage engaged in active study, the anonymous Chinese Scholar figures suggest no imminent action.[43]

In addition to passivity, eighteenth-century stereotypes about Chinese trading practices and effeminacy also could be seen in the Chinese Scholar pattern. Literary historian David Porter has argued that China’s unwillingness to open its borders to international trade led to a widespread “perception among English observers that an unnatural tendency toward blockage and obstructionism was an integral, defining feature of Chinese society as a whole.”[44] The inactivity of the Chinese Scholar could have been read as laziness or boredom related to China’s seeming disinterest in trade with the West. Less critical observers might have taken the scene simply to suggest that China was a land of leisure, another common assumption in the eighteenth century that promulgated the stereotype of Chinese men being unmanly.

A more complex suggestion about gender can be made by exploring the use and social context of Chinese Scholar wares. Later commentators in the eighteenth century generally associated chinoiserie with women. The delicate porcelain teapots, fantastical imaginary settings, and overall domestic emphasis of the “tea table chat” that took hold in the 1740s were regarded as intrinsically feminine. The link between Asian imports and women in fact had been made as early as 1675, when William Wycherly’s play The Country Wife first likened the lust for “china” to female lasciviousness. Despite garnering criticism for lewd jokes, the play enjoyed a successful first run on the London stage and influenced such eighteenth-century works as Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and William Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress series: both use broken porcelain to symbolize the loss of feminine virginity.[45]

The Chinese Scholar wares, however, do not seem initially to have evoked the same powerful associations with women, female sexuality, or feminized social rituals. Many objects decorated with the pattern were used either for display or drinking liquor and imported hot drinks: plates, chargers, wine bottles, caudle cups, posset pots, gorge mugs, tankards, and monteiths (fig. 55). In the 1680s and 1690s, however, imbibing liquors and tea and coffee still remained an activity associated with men and public teahouses and taverns.[46] This same association between early chinoiserie and male-related objects appears on the flat-chased chinoiserie decoration that appeared on a large number of silver monteiths and tankards made in London in the late seventeenth century (figs. 56, 57).[47] A larger study of early chinoiserie might confirm that the style did not begin as the feminized fashion that it became in the eighteenth century but rather as a style linked to men involved in the burgeoning mercantilist trade.

These speculations about how the Chinese Scholar pattern could have reflected and influenced opinions about China might also suggest some deep conflict in the English imagination. The years between 1675 and 1695 marked a significant turning point in the history of England’s empire. With increasing success in India and on the seas, many set their sights on Chinese ports—long dominated by the Dutch—as the next trading frontier, engendering a healthy interest in and admiration of Chinese culture. The excitement of this mercantile ambition was tempered by the fear of rejection from the vast and misunderstood civilizations in Asia. Such insecurities, along with general ignorance about Chinese culture, may have contributed to the condescension seen in the Chinese Scholar pattern and elsewhere. Admiration and condescension often coexist but are more easily projected onto subjects that are especially malleable. Because of its lack of specificity in the eyes of most English people, the Chinese Scholar pattern itself, having been radically simplified and removed from its original context, could absorb and embody different, even contrasting, viewpoints. The faceless, anonymous figure featured in scenes of stylized exoticism could be the great Confucius at one moment and a degrading caricature the next.

Returning to Sir William Temple’s treatise can offer a final resonance for the Chinese Scholar pattern. Temple followed Epicurean thought. His biographer wrote that while Temple never publicly embraced the philosophy, “he based his own mature life on the Epicurean precepts that freedom is the most precious fruit of independence and plain living and that the private citizen lives more calmly and safely than the public man.”[48] The final paragraphs of Temple’s treatise, which celebrate the independent appreciation of nature, may have been an attempt by the aging statesman to encourage his readers, faced with a new question of royal succession, to embrace the sober ideals of Epicurus.

In many ways, the Chinese Scholar pattern might have resonated with Temple and other like-minded thinkers. This robed figure sat in his own personal garden engaged in calm contemplation, much like Epicurus suggested. He seems to embody what literary historian Rose Zimbardo has called the “new feeling about feeling” that arose in the last two decades of the seventeenth century.[49] Writers and theologians began to suggest that they could better understand human behavior through careful self-observation. In 1681 Bishop Samuel Parker explained this new emphasis on individual sentiment: “All men feel a natural Deliciousness consequent upon every exercise of their good-natur’d Passions; and nothing affects the mind with greater Complacency than to reflect upon its own inward Joy and Contentment.”[50] When Parker or Temple gathered with companions to drink in a tavern or a private parlor, they might have passed around libations in a cup or posset pot decorated with the Chinese Scholar pattern. Parker might have appreciated the Chinese scholar’s inward reflection and speculated about the “natural Deliciousness” he might be enjoying. Temple might have remarked on the pattern’s sharawadgi. And both men might have noticed that the anonymous seated figure simultaneously evoked Epicurus, Confucius—and also themselves. All were seen as proponents of personal introspection and individual thought, ideas just coming to the forefront of late-seventeenth-century humanist thinking. The visual hybridity of the Chinese Scholar pattern opened itself to multiple readings because it appeared at once foreign and familiar, generic and specific. Indeed, for Englishmen in this era, the Chinese Scholar pattern could have inspired conversation about the curious merits of asymmetrical design, their own prospects for new trade in Asia, Confucian philosophy, and even the ancient garden of Epicurus—a combination of ideas as mixed and provocative as chinoiserie itself.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This essay grew out of research undertaken for a 2005 exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum called “Enter the Dragon: The Beginnings of English Chinoiserie, 1680–1710.” The exhibition can be viewed on the Chipstone Foundation website at www.chipstone.org. I wish to thank Glenn Adamson, the late Tracey Albainy, Ellenor Alcorn, Michael Archer, Gavin Ashworth, Emerson W. Baker, Mary Beaudry, Ellen Berkland, John H. Bryan, Edward S. Cooke Jr., Julia Curtis, Michelle Erickson, George Fayen, Ron Fuchs, Philippa Glanville, Constance Godfrey, the late Dudley Godfrey, Leslie Grigsby, Suzanne Findlen Hood, the late Jonathan Horne, Paul Huey, Robert Hunter, Nigel Jeffries, Amanda Lange, Ethan Lasser, Ann-Eliza Lewis, Ann Smart Martin, Wynne Patterson, William Pittman, David Porter, Jonathan Prown, Haun Saussy, Timothy James Scarlett, and Fred and Anne Vogel.

Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles: A Catalogue of the Collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: The Stationery Office, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), p. 257.

For updated names, see Leslie B. Grigsby, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, 2 vols. (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 2000), 2:140, d105; and John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), p. 140.

William Temple, “Upon the Gardens of Epicurus; or, of Gardening in the Year 1685,” in Miscellanea, The Second Part, In Four Essays (London: Printed by J. R. for Ri. and Ra. Simpson at the Sign of the Harp, St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1690), pp. 75–141. A widely available reprint is Albert Forbes Sieveking, Sir William Temple upon the Gardens of Epicurus, with Other XVIIth Century Garden Essays (London: Chatto and Windus, 1908).

The classic texts on chinoiserie are Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay (New York: Harper & Row, 1961); Oliver R. Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration (London: Oxford University Press, 1977); and Madeleine Jarry, Chinoiserie: Chinese Influence on European Decorative Art, 17th and 18th Centuries, trans. Gail Mangold-Vine (New York: Vendome Press, 1981). More recent noteworthy studies are Dawn Jacobson, Chinoiserie (London: Phaidon, 1993); and Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer, eds., Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500–1800 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2004).

For references and photographs of sherds found in Maine, see Emerson W. Baker, “The Archaeology of 1690: Status and Material Life on New England’s Northern Frontier,” paper presented at “Fields of Vision: The Material and Visual Culture of New England, 1600–1830,” held at the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, November 9, 2007. For photographs of Chinese Scholar dishes from the Hitchcock site, see “Virtual Norumbega: The Northern New England Frontier,” online at http://w3.salemstate.edu/%7Eebaker/hitchcock/hitchartifacts.html. For sherds found in New York, see Charlotte Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), p. 61, pl. 12, and fig. 12. For sherds found in St. Mary’s City, Maryland, and Jamestown, Hampton, and Williamsburg, Virginia, see Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg, pp. 144, 146. The St. Mary’s City sherd is illustrated in Silas D. Hurry, “—once the metropolis of Maryland”: The History and Archaeology of Maryland’s First Capital (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City Commission, 2001), p. 23. A white-on-blue bleu persan sherd with the Chinese Scholar pattern also appeared in Williamsburg; see Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg, p. 201. The Hampton plate is detailed in Thomas F. Higgins III, Charles M. Downing, and Donald W. Linebaugh, Traces of Historic Kecoughtan: Archaeology at a Seventeenth-Century Plantation (Williamsburg, Va.: William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research, 1999), p. 89. For photographs of sherds with the Chinese Scholar pattern found in Port Royal, see Madeleine J. Donachie, “Household Ceramics at Port Royal, Jamaica, 1655–1692: The Building 4/5 Assemblage” (Ph.D. diss., Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, 2001), pp. 70, 127, 160–61, 164. The findings from excavated sites of this period in New England have not been published. For sherds found in Lambeth, see F. H. Garner, “Lambeth Earthenware,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 1, pt. 4 (1937): pls. 12b, 13a; see also Brian J. Bloice, “Norfolk House, Lambeth: Excavations at a Delftware Kiln Site, 1968,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 5 (1971): 130, drawings 13 and 14. For sherds found in Lambeth and Southwark, see Excavations in Southwark 1973–76, Lambeth 1973–79, Joint Publication No. 3, edited by Peter Hinton (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society and Surrey Archaeological Society, 1988), p. 326, fig. 139, nos. 1382 and 1383 (maybe), and pp. 331–32, figs. 142–43, nos. 1314, 1316, 1400, 1402, 1403, 1404. For a sherd excavated in Belfast, see Peter Francis, Irish Delftware: An Illustrated History (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 2000), p. 26, fig. 25. For a discussion of the physical similarities between English and Dutch tin-glazed earthenware and the inter-trade that makes them difficult to differentiate, see Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America, pp. 78–79, 92–93.

Christiaan J. A. Jörg and Jan van Campen, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: The Ming and Qing Dynasties (London: Philip Wilson, in association with the Rijksmuseum, 1997); Christiaan J. A. Jörg, Fine and Curious: Japanese Export Porcelain in Dutch Collections (Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2003), pp. 9–10; Christiaan Jörg, “Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century: Trading Networks and Private Enterprises,” in The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia No. 16, edited by Rosemary E. Scott (London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 1993), pp. 183–205; Christiaan J. A. Jörg, Interactions in Ceramics: Oriental Porcelain & Delftware, exh. cat. (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Museum of Art, 1984); John Carswell, Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World, exh. cat. (Chicago: University of Chicago, David and Alfred Smart Gallery, 1985), pp. 45, 165; Michael Archer, “Oriental Influence on English Delftware,” in The Potter’s Art: Contributions to the Study of the Koerner Collection of European Ceramics, edited by Carol E. Mayer (Vancouver: Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, 1997), pp. 52–67.

Jörg, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, pp. 74–87; see also Julia B. Curtis and Stephen Little, Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century: Landscapes, Scholars’ Motifs, and Narratives, exh. cat. (New York: China Institute Gallery, 1995); Julia B. Curtis, “Markets, Motifs, and Seventeenth-Century Porcelain from Jingdezhen,” in Scott, ed., Porcelains of Jingdezhen, pp. 123–49; Stephen Little, Chinese Ceramics of the Transitional Period, 1620–1683, exh. cat. (New York: China House Gallery, China Institute in America, 1983); Duncan Macintosh, Chinese Blue and White Porcelain (Newton Abbot, Eng.: David & Charles, 1977).

For cultural life in late Ming China, see Craig Clunas, Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China (1991; reprint, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2004), pp. 141–65, esp. 155–56; Haun Saussy, Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China, Harvard East Asian Monographs 212 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001), pp. 15–34, esp. 22–23. On Ming painting, see James Cahill, The Distant Mountains: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Dynasty, 1570–1644 (New York: Weatherill, 1982), pp. 6–9; and Curtis and Little, Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century, pp. 15–16.

Saussy, Great Walls of Discourse, p. 23; Chu-tsing Li and James C. Y. Watt, eds., The Chinese Scholar’s Studio: Artistic Life in the Late Ming Period; An Exhibition from the Shanghai Museum, exh. cat. (New York: Thames and Hudson, in association with the Asia Society Galleries, 1987). For more in-depth readings of the landscape and “scholar’s study” imagery, see Curtis and Little, Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century, pp. 15–34, 43–88, and Ireneus László Legeza, A Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Malcolm MacDonald Collection of Chinese Ceramics in the Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art and Archaeology, School of Oriental Studies, University of Durham (London: Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 65.

For the influence of Wang Wei’s poetry on Chinese painting, see Robert E. Harrist Jr., “Watching Clouds Rise: A Tang Dynasty Couplet and Its Illustration in Song Painting,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 78 (1991): 301–23. I would like to thank Haun Saussy and George Fayen for this reference. The translation of Wang Wei’s poem “Zhongnan Retreat” comes from Harrist, who cites Pauline Yu, The Poetry of Wang Wei: New Translations and Commentary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), p. 171.

Jörg, “Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century,” pp. 186–87; Jörg, Fine and Curious, p. 9. For a specific shipment of Chinese porcelain to the Netherlands, see C. L. van der Pijl-Ketel, ed., The Ceramic Load of the “Witte Leeuw” (1613) (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1982).

The most thorough and up-to-date presentation of Japanese imports is Jörg, Fine and Curious. Jörg’s work builds on John Ayers, Oliver Impey, and J. V. G. Mallet, Porcelain for Palaces: The Fashion for Japan in Europe, 1650–1750, exh. cat. (London: Oriental Ceramic Society, 1990), pp. 17–24. The period quote and a discussion of the prototypes sent to Japan for copying can be found in Jörg, Fine and Curious, p. 23.

For Japanese-made Chinese forms, see Ayers, Impey, and Mallet, Porcelain for Palaces, p. 97, no. 38, p. 191, no. 180. For discussion of the V-shaped strokes, ibid., pp. 37, 91; and Jörg, Fine and Curious, p. 24. Stephen Little disagrees with Oliver Impey and suggests that V-shaped strokes also appeared on Chinese originals. See Little, Chinese Ceramics of the Transitional Period, p. 11.

An excellent narrative of Dutch tin-glazed earthenware production has been translated into English. See Jan Daniël van Dam, Delffse Porceleyne: Dutch Delftware, 1620–1850 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2004). The class associations of chinoiserie tin-glazed earthenware in the Netherlands are discussed in Jörg, “Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century,” pp. 193–94. For more on Dutch tin-glazed earthenware in this period, see H[enri]-P[ierre] Fourest, Delftware: Faience Production at Delft, trans. Katherine Watson (New York: Rizzoli, 1980).

Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay, pp. 48–49; Carswell, Blue and White, pp. 40–42; and Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America, pp. 53–54. Michael Archer suggests that the French were copying Ming Transitional patterns before the Dutch. See Archer, “Oriental Influence on English Delftware,” p. 57. For a general source on French tin-glazed earthenware, see Danielle Maternati-Baldouy, Faience et porcelaine de Marseille, XVIIe–XVIIIe siècles: Collections du Musée de la Faïence de Marseille (Marseille: Musées de Marseille, 1997).