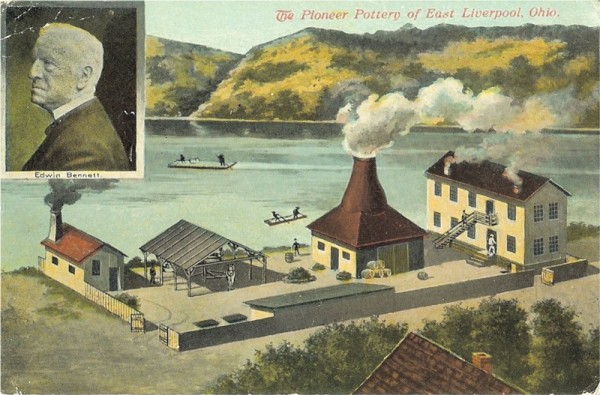

Postcard, The Pioneer Pottery of East Liverpool, Ohio, and Edwin Bennett (inset), ca. 1915. (Unless otherwise noted, objects courtesy of Barbara and Ken Beem; photos, the authors.) The “Pioneer Pottery” referred to in the title is, in fact, the Bennett Brothers Pottery.

Plaque depicting President Ulysses S. Grant, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. H. 11 15/16". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

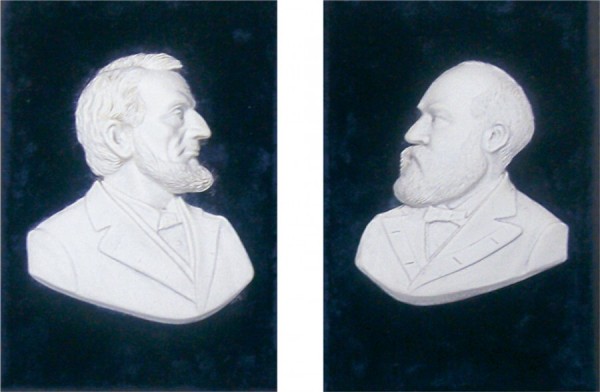

Pair of plaques depicting (left) President Abraham Lincoln and (right) President James A. Garfield, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian mounted on velvet. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Pair of vases, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1884–1886. Parian. H. of each 5". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) Each vase is in the form of a snail shell resting on a base of coral sprigs.

Pair of two-handled vases, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1884–1886. Parian. H. of each 8". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) The raised decoration is of stylized nature motifs.

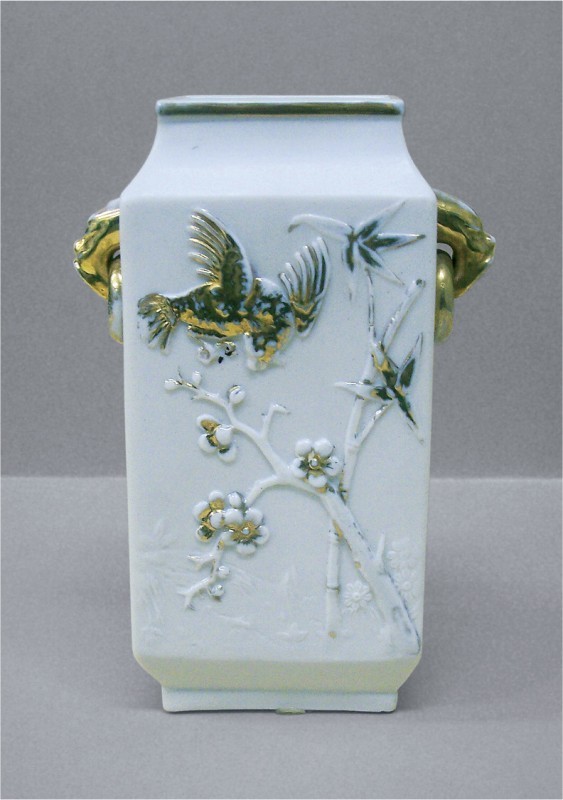

Two-handled vase, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1884–1886. Porcelain. H. 6". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) This rectangular vase is decorated with birds and flowering branches and has gold trim.

Vase, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1884–1886. Porcelain. H. 6 3/16". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) White-on-blue pillow vase depicting Venus on a half shell being pulled by dolphins. The vase rests on twig-shaped feet.

American Belleek tea set, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1886. Porcelain with hand-painted gold trim and honeycomb pattern. H. of teapot 6"; H. of covered sugar bowl 4 3/4"; H. of each creamer 3 3/4".

Bottom of one of the creamers illustrated in fig. 8, showing the letter “B” painted on one of the feet.

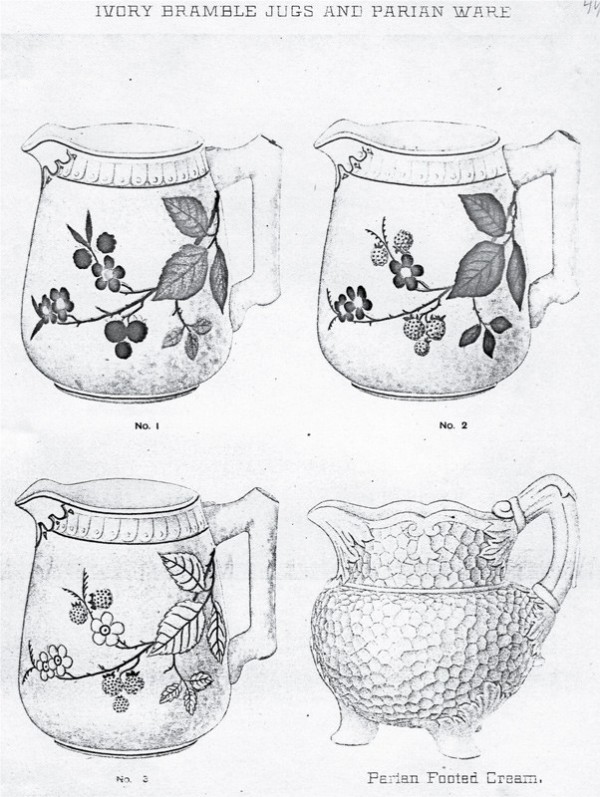

Page from Edwin Bennett Pottery catalog, Baltimore, Maryland, undated. Among the items on the page is a “Parian Footed Cream.”

Creamers, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1886–1887. Left: American Belleek creamer. Porcelain with gold trim. H. 3 3/4". Right: Three-legged creamer. Parian. H. 4 1/2".

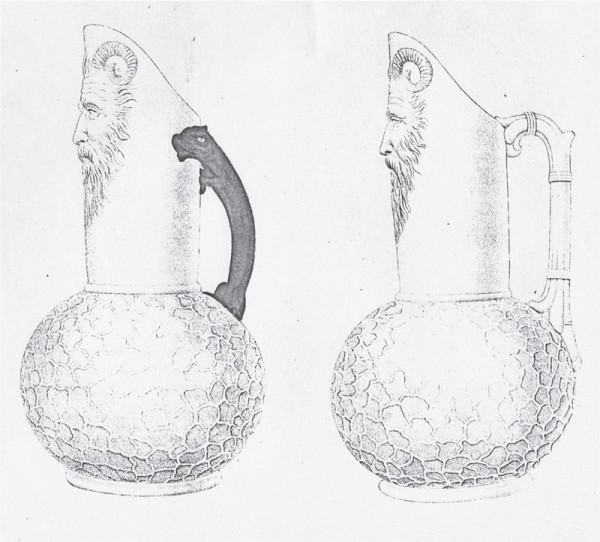

Page from Edwin Bennett Pottery catalog, Baltimore, Maryland, undated. The page illustrates two “Oriental Pitchers,” each of which bears the face of a satyr under the spout.

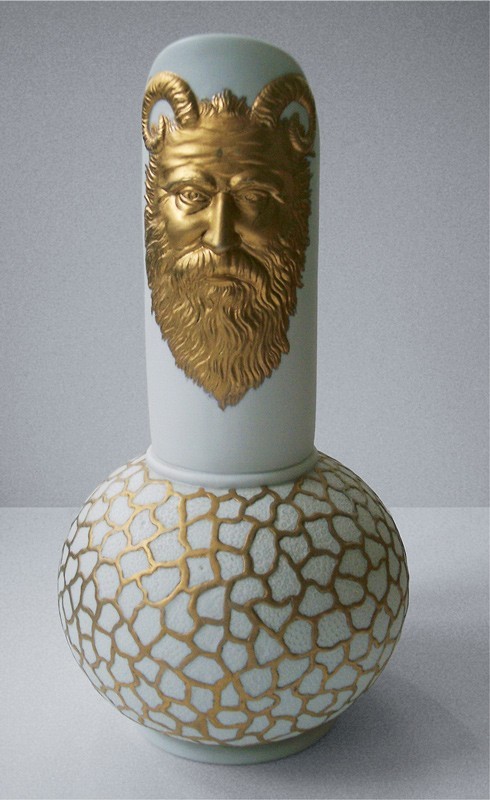

Pitcher, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1886–1887. Parian. H. 12 1/2". This gold-trimmed pitcher with a bamboo handle portrays the raised face of a satyr under the spout.

Front view of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 13, showing the front view of the satyr.

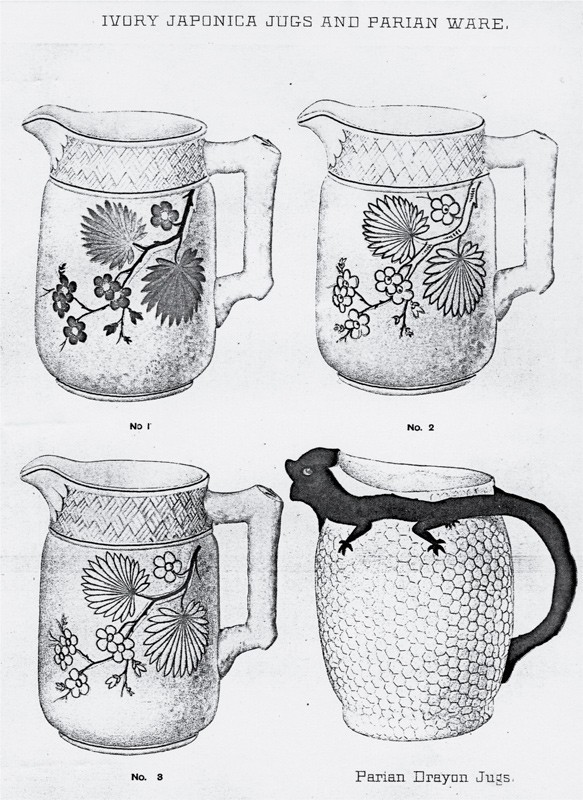

Page from Edwin Bennett Pottery catalog, Baltimore, Maryland, undated. In the lower right corner is an example of a “Parian Drayon Jug.”

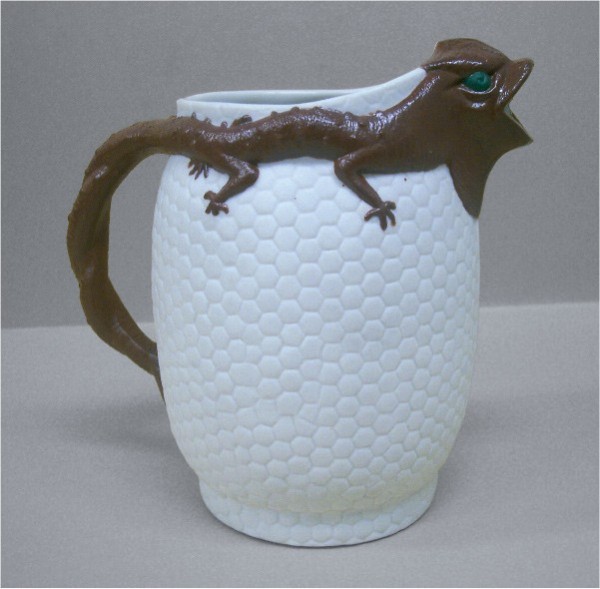

Pitcher, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1885–1887. Parian. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) A reddish brown lizard forms the handle and pour spout of this “Drayon” jug.

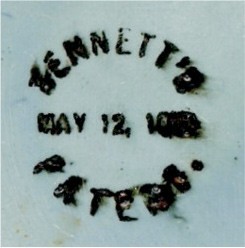

Stamp on bottom of white earthenware “Drayon” jug, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1885. Mark: BENNETT’S / MAY 12, 1885 / PATENT.

Pitcher, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1884–1887. Porcelain. H. 7". This decorative ale pitcher has gold trim and an intricate street scene in low relief.

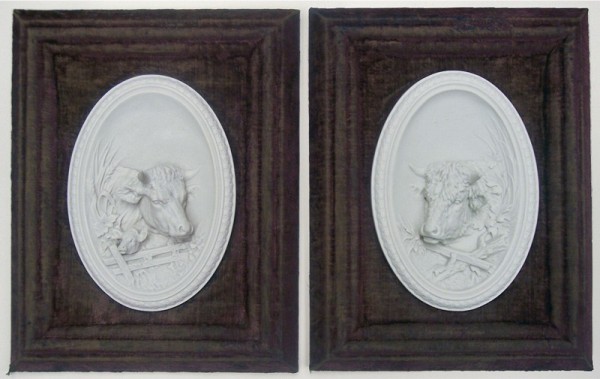

Pair of mounted and framed bovine plaques, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883. Parian. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.) These plaques depict the heads of a cow and calf (left) and a bull (right) and are mounted on velvet.

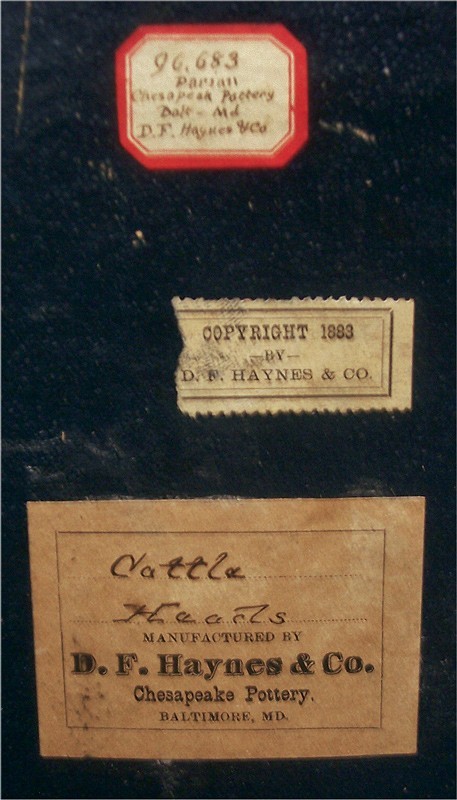

The back of one of the plaques illustrated in fig. 19, with a label showing a copyright date of 1883.

“Winter” plaque, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. D. 9".

“Summer” plaque, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. D. 8 3/4".

“Fall” plaque, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. D. 7 15/16". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

“Day” (left) and “Night” (right) plaques. Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. White classical figures on parian plaques painted greenish brown. D. 6". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

“Old Age”(left) and “Childhood” (right) plaques, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. White classical figures on parian plaques painted greenish brown. D. 5 1/4". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

“Maturity” (left) and “Old Age” (right) plaques, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. D. 5 1/4".

Flowers and flower parts, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Flowers and flower parts, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

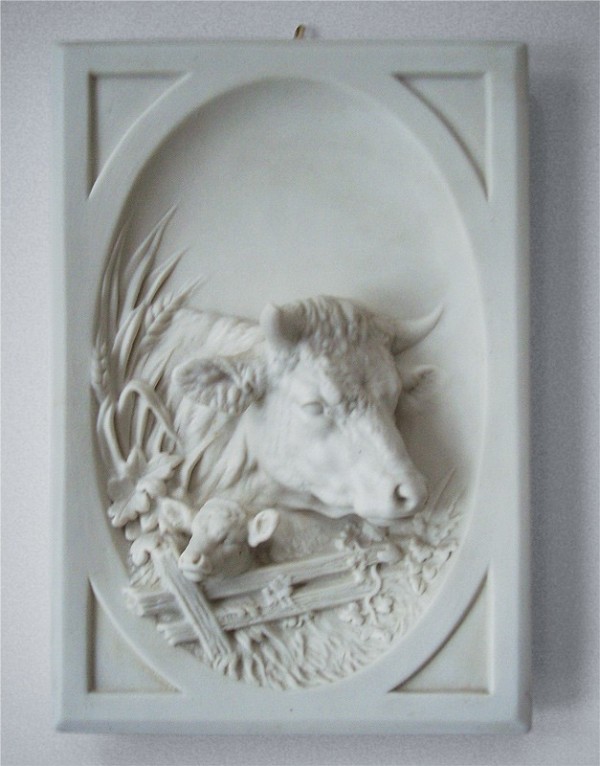

Heads of cow and calf plaque, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1887. Parian. H. 9".

State seal of North Carolina plaque, Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, John Collier collection.)

State seal of North Carolina plaque, Chesapeake Pottery or Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1883–1886. Parian. H. 9 1/2".

“Innocence” plaque, Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1887. Parian. D. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Baltimore, Maryland, once a major industrial center, also played a short-lived but significant role in ceramics history in America. For a few years, the city’s now-defunct potteries were energized by a cross-town competition, but more than a century later, as with so many stories of this sort, few people know what really happened. The tale has been obscured, eyewitnesses are long dead, and bits of the story are lost. What remain are threads of information buried in dusty files and, of course, the porcelain.

In the forefront of the production of ceramics in Baltimore were two men, Edwin Bennett and David Francis Haynes. Their career paths, while not parallel, led them to challenge each other professionally and personally to attain a higher level of artistry and, in the end, reach the highest level of porcelain production.

Edwin Bennett

Edwin Bennett was born in 1818 in the English town of Newhall, Derbyshire.[1] His father, Daniel Bennett, supported his large family as the principal bookkeeper for a local coal-mining company. Edwin inherited his father’s business sense and exhibited brilliant acumen throughout his career.

Young Edwin received what he termed to be a “common” education in his local school and then went on, with three of his brothers, to learn the pottery trade. It was not an unusual choice, considering the fact that the Bennett family lived in the heart of Britain’s ceramics industry. Edwin served an apprenticeship with the firm of Harrison and Cash in the nearby village of Wooden Box (renamed “Woodville” in 1845) and subsequently found employment near his home. Then, in 1841 he and two of his brothers, Daniel and William, immigrated to America.

They were not the first members of the family to make the transatlantic journey. Six years earlier, in 1835, their older brother James had come to the United States, where he soon found employment at the Jersey City Pottery.[2] In 1837 James joined a group of fellow British potters at James Clews’s newly constructed Indiana Pottery Company in Troy, Indiana, just across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. In the following year, James and his wife, Jane, decided to leave the area because of widespread malaria in the swampy lands where the pottery was located.

Traveling by steamboat up the Ohio River, James found clays suitable for making ceramics at East Liverpool, Ohio, and decided to establish a pottery works there. His timing was good: the area had a new generation of consumers who could afford increasingly sophisticated household wares of all kinds. James lacked sufficient resources to fund his enterprise, but he was able to borrow enough money from local residents Anthony Kearns and Benjamin Harker to construct a single-kiln pottery in 1839. He was the first to do so in a town that would later become an important center for ceramic production (fig. 1). In 1840 James’s initial firing of yellow ware and Rockingham ware was so successful that he sent word to his brothers to join him. That same year Harker, impressed with Bennett’s success, constructed his own small pottery nearby, which over the years evolved into the well-known Harker Pottery Company.

The brothers heeded the call and made the five-week ocean voyage to meet James in Ohio. Within three years of the Bennetts joining forces, they decided to relocate in order to be free from growing competition and to seek a broader market and better shipping facilities for their products. James sold his factory to Thomas Croxall and Bros., and the Bennetts moved on, traveling eastward via the Ohio River.

Pooling their talents, the four potters—Edwin, James, Daniel, and William—erected a new plant in Birmingham, now part of South Pittsburgh, in 1844.[3] This newly established company, Bennett & Brothers, continued to produce the same lines that James had developed so successfully back in Ohio. Two years later Edwin decided to move to Baltimore, Maryland. The reasons for this are not clear, but Baltimore was an important railroad and shipping hub at the time, so possibly he wanted to facilitate distribution of the Pittsburgh factory’s products.

Once in Baltimore, though, Edwin discovered that the native clays were highly suitable for making pottery, there was an ample supply of cheap immigrant labor in the city, and the coal necessary for firing kilns could be brought in by train. In 1847 Edwin began producing primarily utilitarian wares at his new pottery located in East Baltimore, at the corner of Canton Avenue (now Fleet Street) and Canal Street (now Central Avenue).[4] Starting with one kiln, he made his own designs and, for a short time, produced his own ceramics without assistance, trading under the name Edwin Bennett Queensware Manufactory. Although there were other potters in the city, none of them exhibited interest in producing the kind of wares to which Bennett aspired. He knew his trade, had a keen business sense, and was able to market his products effectively.

Success came rapidly as the company expanded into a multi-kiln operation. In 1848 Edwin was joined by his younger brother William and they formed a new partnership, E & W Bennett. They quickly expanded their lines, adding colored stonewares and majolica. They began experimenting with the development of parian ware, a generally unglazed hard-paste porcelain meant to resemble marble from the island of Paros.[5] On the other end of the spectrum, the development of the Rockingham ware teapot known as “Rebekah at the Well,” modeled by Charles Coxon in 1851, brought the pottery public acclaim and increasing financial success. When William returned to Pittsburgh in 1856 to help run the Birmingham pottery after James’s retirement, the company was renamed the Edwin Bennett Pottery.[6]

At the outset of the Civil War, however, Edwin, a staunch Unionist, found himself in a city that did not share his sentiments. The first pitched battle of the war occurred on April 19, 1861, in the street directly in front of his business, an attack by a pro-Southern mob on federal troops passing through Baltimore on their way to Washington, D.C. Fearing for the safety of his family, he moved them to Philadelphia.[7] His pottery remained open during the war, though, and he made regular visits back to Baltimore to oversee its progress.

Edwin was not idle while in self-imposed exile in Philadelphia: he joined with William T. Gillinder to form the Franklin Flint Glass Works, later to be called Gillinder & Sons.[8] He developed new designs for tableware using pressed glass instead of ceramics. In 1867, after the war, Edwin moved back to Baltimore and picked up where he left off, developing white-bodied earthenware ceramics to conform to changing public demand. There were other potteries in the city, but his was the largest and the only one to make something other than the most basic of stoneware pieces. That would all change, however.

David F. Haynes

David Francis Haynes was born in Brookfield, Massachusetts, in 1835.[9] At age sixteen he left the family farm to work at a crockery store in nearby Lowell, Massachusetts. While employed there, he was sent to England to develop relationships with the British ceramics industry. During his trip, he visited the major Staffordshire potteries, where he garnered practical insight into pottery production. More important, he was introduced to the tenets of a concept that would become known as the aesthetic movement. He loved the natural, flowing form that resulted from the fusion of Eastern and Western influences. He agreed that beauty should be evident in even the most mundane household goods, to promote a spirit of harmony and general well-being.

With these newly developed aesthetic sensibilities, Haynes returned to America, ultimately settling in Baltimore. He was employed by the Abbott Rolling Mills, one of the country’s largest iron foundries at the time, and during the Civil War was placed in charge of the production of armor plating for the U.S. Navy’s ironclad warships. In 1871 he took a position with Ammidon and Company, a wholesaler of oil lamps, crockery, and hardware. He became a partner the following year and sole proprietor in 1877, at which time the name of the firm was changed to D. F. Haynes and Co.[10]

In 1879 Haynes became the sole distributor for the Maryland Queensware Factory, a newly established Baltimore pottery that produced whiteware. The factory was located at Fawn and President Streets, just a few blocks west of the Bennett pottery.[11]

Shortly thereafter, in 1880, three Englishmen with extensive potting experience—Isaac Brougham, Henry Brougham, and John Tunstall—formed the Chesapeake Pottery, constructed in an area of South Baltimore called Locust Point, at the corner of Decatur and Nicholson streets.[12] The three tried to replicate the Rockingham ware that Bennett had marketed successfully for more than thirty years from a site just across the harbor. Unfortunately, those wares were considered primitive and countrified by that time and, to make matters worse, the output of the new company was clearly inferior in quality to that of the Bennett factory.

When the floundering Chesapeake Pottery was offered for sale in 1882, David Haynes saw an opportunity to realize his artistic ambitions. He bought the two-building, single-kiln operation in the spring of that year, while abandoning all attachments to the Maryland Queensware Factory.[13]

Haynes wasted little time in revamping his new acquisition. He expanded the facilities and hired two experienced English potters to help run the facility. Lewis Taft, formerly of William Brownfield & Son of Cobridge, Staffordshire, was put in charge of glazes, bodies, and kilns, making him responsible for the pottery’s production. Frederick Hackney, a majolica specialist who had left Wedgwood to found the Railway Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, was hired to oversee modeling, essentially becoming the chief designer.[14] With these changes in place, the factory immediately stopped producing Rockingham ware and turned to white earthenware, jasperware, “majolica,” and a refined stoneware. Haynes, however, had his sights set higher. He wanted to make porcelain.

“White Gold”

A hard, white, nonporous, translucent variety of ceramic, porcelain is the finest of the fine, representative of high achievement on the part of its maker. Seen in China by Marco Polo on his thirteenth-century journey along the Silk Road, porcelain was so named because Marco Polo thought it resembled porcellana, the Italian name for the translucent-surfaced cowry shell. This treasured ceramic so caught the imaginations of connoisseurs in the West that it sparked a centuries-long effort to replicate this “white gold.”

It was not until 1708 that Johann Friedrich Boettger, a German alchemist, abandoned his futile attempts to produce gold from base metals and turned his attention to cracking the code for the manufacture of porcelain. Boettger made his breakthrough discovery when he fired a paste composed of kaolin, quartz, and alabaster at an extremely high temperature.[15] What he produced was true porcelain, what is known as hard-paste porcelain, not unlike that of the Chinese but developed independently of the Far Eastern potters’ formulas and techniques. It was later found that porcelain could be made at a lower temperature by substituting feldspar for alabaster. Not only was this an easier process, but feldspars are the most abundant family of minerals at the earth’s surface. Meanwhile, by the mid-eighteenth century other forms of porcelain were being developed in America and Europe, including soft-paste porcelain (a mixture of kaolin and ground glass) and bone china (composed of kaolin and ground animal bone).

David Haynes wanted to create hard-paste porcelain, not unlike the unglazed parian ware that his chief competitor, Edwin Bennett, had attempted nearly three decades earlier. Haynes was not interested in mere experimentation, though. He meant to succeed on both a commercial level and an aesthetic one.

Although he had been in the business of producing ceramics for only a year, Haynes was well-positioned for this venture. Taft, the man Haynes had placed in charge of his factory’s production, brought with him much experience in the making of porcelain. The William Brownfield factory, among the six largest potteries in Staffordshire in the second half of the nineteenth century, was noted primarily for its parian ware. With a staff exceeding five hundred workers, this single pottery produced in excess of seven thousand different porcelain patterns and more than four hundred shapes of porcelain figures before it closed in 1900.[16]

Bringing his own marketing and business experience to his company, Haynes relied on a carefully chosen group of highly talented artisans to translate his artistic concepts into sellable wares. He wasted little time in going after his primary competition, the Edwin Bennett Pottery, which by then had been in business for about thirty-five years. Utilizing local sources of clay, Haynes, in 1882, began with the production of a transfer-decorated cream-colored earthenware he called “Real Ivory.”[17] This was well received by the buying public.

Almost immediately thereafter, Haynes introduced “Baltimore Majolica”—not majolica in the strictest sense but, rather, a line of yellow ware decorated by enameling under the glaze. This was followed by “Severn Ware,” a decorative fine stoneware enhanced with designs characteristic of the aesthetic movement. And then there was the porcelain.

Haynes decided to produce a series of parian porcelain plaques to be used to beautify the homes of his fashionable customers. To create the designs for these plaques, he hired James Priestman, an English sculptor who worked with the firm from 1883 to 1886. Little is known about Priestman, although his arrival in Baltimore from Boston was noted in the Crockery and Glass Journal in 1883.[18] Priestman modeled every parian ware plaque made by the Chesapeake Pottery, though it is difficult to be certain whether artistic decisions were made unilaterally by Haynes or by Priestman or in collaboration. It would appear, however, that Haynes charted the company’s overall course on his own.

Among the first porcelain products to be offered to the public were plaques in high relief depicting the heads of short-horned cattle, modeled by Priestman “from studies of typical animals in the noted herd of Mr. Harvey Adams.”[19] Contemporary reports said that the plaques were considered “praiseworthy.” Bovine subjects aside, Priestman then turned to botanicals for inspiration. The resulting products were parian tea roses, which were sold mounted on velvet. Like the cow plaques, they were intended as wall hangings.

Haynes had hit upon a popular formula. Though not a potter himself, he understood the fashion trends of the time, and he knew how to please consumers who had the means to update and decorate their homes. What followed was a wide array of porcelain pieces designed to be hung on walls and admired.

The Chesapeake Pottery’s output of porcelain included a set of four large wall plaques, one for each season, depicting the bust of an agrarian woman with seasonal crops. Other parian products included plaques adapted from a series of famous marble medallions by Bertel Thorvaldsen, a well-known Danish sculptor of the early part of the nineteenth century. A series of plaques featuring the profiles of political figures of the day was offered as well (figs. 2, 3). All of these items were produced within a short time frame, from 1883 to 1886.

However, it was not all smooth sailing at the Chesapeake Pottery. Labor unrest, the sudden death of George H. Miller (the chief financial backer of the pottery), and Haynes’s overextension of the capabilities of his company at a time of downturn in the local economy led to a major financial crisis.[20] Haynes was left with little choice but to find a buyer for his floundering enterprise.

He did not have to look far. On the other side of the harbor, Edwin Bennett had been forced to react to the numerous innovations that the upstart Chesapeake Pottery had been introducing to the market. Bennett was well aware of the advances Haynes had made in the line of porcelain and felt compelled to try to match what the rival pottery was turning out. Bennett had some disadvantages. He did not have the depth of talent at his disposal that Haynes did. His factory, which occupied a whole city block, had little room for physical expansion. A recent decision to develop a tile works on the land just south of his pottery had absorbed much capital and space, not to mention his own energy. To refit his pottery to include the sorts of kilns necessary for producing porcelain would be a strain on his resources.

Bennett did the best he could. He realized that to keep his company solvent, he had to strive to move forward at all times. Without increased production, the entire operation would fold under its own weight. And so, seizing on Haynes’s misfortune, Bennett bought the Chesapeake Pottery in 1887 while retaining Haynes as general manager, a situation that surely left the man who had been considered the rising star of the industry in a compromised position.[21] At this point, James Priestman, the man who had fashioned the models for the porcelain pieces produced by the Chesapeake Pottery, disappeared from the scene. His subsequent activities remain a mystery.

With his purchase of the Chesapeake Pottery, Bennett had the capability of making the sort of wares that Haynes had been producing. The factories and kilns were his, the existing talent was in his employ, and he no longer had to look across the harbor at a competitor.

At this time, Bennett produced a very small quantity of American Belleek tête-à-tête tea sets in what he called “eggshell porcelain.” According to Bennett family tradition, these rare, experimental pieces were made for the enjoyment of family members only. Although these tea sets were not offered to the public, they were among the most sophisticated ceramics made in America to date.[22] He also continued the line of parian wares begun at Chesapeake, adding pitchers and vases to the offerings (figs. 4-7).

Bennett soon realized, however, that as artistically and professionally satisfying as these porcelain pieces must have been to him, they were not going to be a commercial success. Ireland was flooding the American market with affordable Belleek at this time, and several competing New Jersey potteries had discovered ways to produce the same kinds of wares in a more financially viable way. Besides, his own customers were less interested in such high-end products than in everyday household wares like teapots, dinnerware, and toilet sets. Bennett understood that this was where his fortune lay. He could not allow himself to lose sight of what his customers demanded. He needed to check his own competitive spirit and stay the course.

Being an able businessman as well as a master potter, Bennett did just that. He exhibited a level of restraint that had eluded his competitor. Although he had been anxious to keep up with Haynes, Bennett knew better than to make the same mistakes that his former rival had made. Producing highly artistic wares was prestigious, but it was not particularly profitable. Furthermore, Haynes had attempted to introduce a very diverse line in a short time frame, a move that had contributed to his demise. Bennett’s cool business head overruled his artistic urges. Porcelain was not to be the key to business success in Baltimore. Within a year, porcelain production ceased. The chapter was over.

Because of the financial strain of running two potteries, Bennett sold public stock in his company in 1890, changing the name to the Edwin Bennett Pottery Company.[23] At the same time, he divested himself of the Chesapeake Pottery, giving his son, Edwin Huston Bennett, joint control with Haynes of the business. Trading under the name of Haynes, Bennett & Co., the new management team once again began producing a great diversity of products, but this time in white earthenware alone. Five years later, Huston Bennett sold his shares to Haynes’s son, Frank R. Haynes, and the company was renamed D. F. Haynes & Son in 1896.[24]

Except for a few forays into the creation of art pottery, Bennett continued to make only utilitarian earthenwares. Coincidentally, Edwin Bennett and David Haynes died in the same year, 1908. Bennett’s elder son continued to operate the family pottery, but the quality of the product decreased. A victim of the Great Depression, the Edwin Bennett Pottery Company closed its doors in 1936.[25] The Chesapeake Pottery, under the leadership of Frank Haynes, also went into artistic and financial decline after the death of his father. The entire business was dissolved in 1914, and the property was sold to the American Sugar Refinery Company, producers of Domino Sugar.[26]

For collectors, locating examples of Baltimore porcelain is challenging, as the production of these pieces was always extremely limited. Occasional pieces might be offered on Internet sites, but the seller usually has little or no knowledge of the origin of the objects. Because both the Chesapeake Pottery and the Bennett Pottery had sales outlets in major cities across the country, their porcelain products may be found in regions far from Baltimore.

Representative Examples from the Bennett Factory

Arguably the most significant achievement by Baltimore potteries working in porcelain is the American Belleek tête-à-tête tea set produced in 1887 by the Edwin Bennett Pottery (fig. 8). Three pieces from one of the known surviving tea sets—a teapot, creamer, and sugar bowl—rest on four splayed feet. Also included in the set are two cups and saucers and a 16-inch serving tray. All of these pieces are decorated with an overall honeycomb pattern that is accentuated by hand-applied gold trim. One foot of the creamer and the bottom of the tray are marked with a handwritten “B” in gold, the only known factory markings on any piece of Baltimore porcelain from this period (fig. 9). What makes these pieces particularly desirable is the delicacy of their construction: “eggshell” is an accurate description of the thickness of the walls of the serving pieces. When compared with other wares the pottery was making contemporaneously, most notably Rockingham “Rebekah at the Well” teapots, the differences could not be more stunning.

Bennett also produced parian cream pitchers with honeycomb decoration on the bodies. Intended for retail sale, they are represented in an undated catalog presumed to be from the same time as the tea sets (fig. 10). These pitchers are nearly identical in design to the eggshell creamers; the major difference, aside from the fact that they are about an inch taller, is the fact that they have but three splayed feet (fig. 11). There is no evidence that any other components of tea sets were made in parian.

Found in the same catalog as the cream pitchers are the largest pieces of Baltimore porcelain from the period, what are referred to as “Oriental” pitchers (fig. 12). Made of parian, they stand 12 1/2 inches tall, with a raised crackle pattern on the globular base. The cylindrical neck is remarkable for its decoration, a raised face of a bearded satyrlike figure with horns. An elongated handle was worked in either a bamboo or a lizard motif. These pitchers are decorated with a heavy application of gold (figs. 13, 14).

Also figured in the catalog is a parian “Drayon” jug (fig. 15). Measuring 6 1/2 inches tall, its most distinctive feature is a lizard handle, the design of which stretches across the open top to form the spout, which is the lizard’s mouth (fig. 16). The body of the pitcher bears a honeycomb pattern. Bennett reused this design, employing the molds for white earthenware pitchers as well as those done in parian. The base of an example fashioned in white earthenware is marked “BENNETT’S / MAY 12, 1885 / PATENT” (fig. 17).

Dating from approximately the same time is a 7-inch-tall decorative ale pitcher with a glazed porcelain finish with gold overlay on the handle, pour spout, and top rim. Its handle has a twig design, and the body of the pitcher is decorated with an intricate street scene, including an assemblage of musicians and dancing children, all worked in low relief. The chimney of a house is incorporated into the pour spout (fig. 18).

Representative Pieces Produced by D. F. Haynes at the Chesapeake Pottery

Haynes introduced his line of porcelain plaques during his pottery’s second year of operation. Copyrighted in 1883, one plaque displays the heads of a cow and a calf; its matching piece bears the head of a bull. The plaques are oval in shape, measuring 9 1/4 inches high and 6 1/2 inches wide. Around the edge of each plaque is a garland of leaves. The plaques were sold mounted in a burgundy-colored velvet matting, which extends into a self-frame (figs. 19, 20).

Representing the Chesapeake Pottery’s highest level of known artistic achievement are four parian plaques, one for each season of the year. Some things about them are similar: each is in high relief, and a plain banded border frames each of the four. The central motif is that of a bust of a woman holding items representative of the season. The plaques are all circular in shape. In addition to the different seasonal depictions, there are some variances: the plaques differ in size and do not picture the same woman.

The most commonly found of the quartet is “Winter” (fig. 21), which features a woman looking over her left shoulder, hair held in place with a crown of holly but still blowing in the breeze. In her right hand is a bundle of kindling. This plaque is the largest of the set, measuring 9 inches in diameter. Haynes bought this design from Priestman in 1883 and soon after commissioned him to create “Summer” (fig. 22), followed by “Spring” and “Fall” (fig. 23).[27] Priestman’s models for “Winter” and “Summer” were also subsequently used on hand-painted iron flue covers produced by the firm of Bradley & Hubbard.

Another acclaimed pair of parian plaques produced under Haynes’s direction was a reproduction of Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen’s “Day” and “Night” designs. “Day” portrays Aurora, a winged figure of a woman scattering flowers. She carries a torch-bearing cherublike creature on her shoulders. “Night” also illustrates a winged woman, this one carrying her two infants, Sleep and Death. She is accompanied by an owl. These plaques measure 6 inches in diameter and are quite similar to parian plaques of the same design made by other manufacturers with one noted exception, that being a circle of acanthus leaves around the outer edges of the plaques. The pair was originally mounted on silk plush mats. Interestingly, the examples in the holdings of the Smithsonian were subjected to a personalization of sorts, when someone post-production painted the backgrounds of the plaques a greenish brown (fig. 24).[28]

The Chesapeake Pottery also reproduced Thorvaldsen’s The Four Ages of Man in a series of round plaques 5 1/4 inches in diameter. Classical figures depict “Childhood,” “Youth,” “Maturity,” and “Old Age.” All are ringed on the outer edge by a band of acanthus leaves, serving as a distinguishing marker for the plaques made by Chesapeake. Again, the examples held by the Smithsonian were hand-painted after production (figs. 25, 26).

Chesapeake or Bennett?

An absence of marks and a shortage of catalog documentation make it difficult to determine at which factory, Chesapeake or Bennett, some pieces of Baltimore porcelain were made. A prime example is a number of intricately worked flowers, pieces that originally were displayed on factory-supplied silk backings but many of which have subsequently become dismounted. It is known that Chesapeake began making such pieces as early as 1883, and that Bennett followed suit by the following year. Today, these flowers remain curious examples of decorative artwork from their era (figs. 27, 28).

In a similar vein, rectangular plaques measuring 9 by 6 inches using the same cow and bull heads as in the earlier Chesapeake plaques have been found. A smooth oval band and a beveled outer self-frame differentiate them from the typical Chesapeake examples (fig. 29). These were probably not marketed with plush silk mats. Because Bennett is known to have produced cow-head plaques in both parian and terracotta, it could be surmised that this rectangular style was a product of the Bennett firm after it absorbed the Chesapeake Pottery in 1887, but currently there is no way to verify this assumption.[29]

Another plaque of questionable origin is that bearing an adaptation of the state seal of North Carolina. With an identifying raised caption on its otherwise plain surround, this plaque was probably made as an advertising premium for Marburg Brothers’ “Seal of North Carolina Smoking Tobacco.” The design bears all the hallmarks of Priestman’s work, and the original was almost surely produced by the Chesapeake Pottery (fig. 30). There is at least one known example on which the identifying caption in the mold has been deliberately filled in, evidently in an attempt to eradicate the wording (fig. 31). This suggests that the mold might have been reused by Bennett after he acquired the Chesapeake holdings, although not as an advertising piece; once again, there is no way to be certain.

Finally, there is a pink-tinted parian plaque, entitled “Innocence,” portraying two cupidlike children washing their pet (fig. 32). Here, the hand of Priestman is clearly present. We know that Bennett made the plaque in 1887, but whether production took place at the Chesapeake Pottery in Locust Point or across the harbor at the Bennett Pottery cannot be verified.[30]

Final Thoughts

Because most Baltimore porcelain pieces were never marked, identifying them is difficult. Verification of individual pieces can be made using illustrations in the few surviving examples of company catalogs or by using a reference piece as a standard. The Division of Home and Community Life at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History is the repository of a number of porcelain items that were donated by both the Chesapeake Pottery and members of the Bennett family, although the collection is no longer on display. Another extensive collection is held by the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore.

When Edwin Bennett purchased the Chesapeake Pottery in 1887, he assumed ownership of the entire inventory of unsold wares. As a result, pieces that had been made by Haynes were later donated to museums by the Bennett family, making it impossible in many cases to determine which factory actually produced them.

Today, the pottery sites are unrecognizable. A bakery warehouse fills the space that was once Bennett’s, and a new highway has been constructed atop the site that was once the Chesapeake Pottery. With both sites completely destroyed, the only tangible items that remain from a few glorious years are some yellowing scraps of paper and a dwindling number of porcelain treasures.

W[illiam] P[ercival] Jervis, The Encyclopedia of Ceramics (New York: Blanchard, 1902), p. 44.

Edwin AtLee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 2nd ed., rev. and enl. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1901), p. 192.

Ibid., p. 195.

Eugenia Calvert Holland, “Edwin Bennett (6 March 1818–3 June 1908) and the Early Products of His Baltimore Pottery 1845–1936,” The Maryland Historical Society (February 1983): 40.

John Spargo, Early American Pottery and China (New York: Century Co., 1926), p. 334.

Marcia Ray, Collectible Ceramics: An Encyclopedia of Pottery and Porcelain for the American Collector (New York: Crown Publishers, 1974), p. 16.

Holland, “Edwin Bennett,” p. 41.

Susan H. Myers, “Gillinder & Sons Cameo Glass,” The Glass Club Bulletin, no. 161 (Spring 1990): 7, 8.

Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 320.

Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, “Dictionary of Architects, Artisans, Artists, and Manufacturers,” in Doreen Bolger, In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986), p. 436.

Ibid.

Nancy FitzPatrick, “The Chesapeake Pottery Company (Baltimore, Md., 1882–1914),” The Spinning Wheel (September 1957): 14.

Edwin AtLee Barber, Marks of American Potters (1904; reprint, Southampton, N.Y.: Cracker Barrel Press, 1971), p. 148.

Voorsanger, “Dictionary of Architects, Artisans, Artists, and Manufacturers,” p. 436.

Warren E. Cox, The Book of Pottery and Porcelain, 2 vols. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970), 2: 643–46.

For more about the Brownfield pottery, see www.brownfield.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/ (accessed March 5, 2012).

Barber, Marks of American Potters, p. 148.

Susan H. Myers, “Aesthetic Aspirations: Baltimore Potters and the Art Craze,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 8 (1992): 38–39.

Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, pp. 324–25.

Myers, “Aesthetic Aspirations: Baltimore Potters and the Art Craze,” p. 36.

Ibid., pp. 38–39.

Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 197.

Myers, “Aesthetic Aspirations: Baltimore Potters and the Art Craze,” p. 49.

FitzPatrick, “The Chesapeake Pottery Company,” p. 18.

Myers, “Aesthetic Aspirations: Baltimore Potters and the Art Craze,” p. 49.

FitzPatrick, “The Chesapeake Pottery Company,” p. 18.

Voorsanger, “Dictionary of Architects, Artisans, Artists, and Manufacturers,” p. 436.

Myers, “Aesthetic Aspirations: Baltimore Potters and the Art Craze,” pp. 36–37.

Ibid., p. 38.

Ibid.