Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum. Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, attributed to John Swann, Alexandria, Virginia, 1810–1819. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 11". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Right: H. 9". (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.) The bulbous shape and brown neck and shoulder of both jars are similar to Swann’s jugs, and the rim forms match fragments of similar wares from the kiln site at the Wilkes Street Pottery. The shape is continued in Swann’s later cobalt-decorated jars. Archaeologists found the jar (left) in a privy on a residential site at 104 South Saint Asaph Street in Alexandria.

Impressed capacity mark, attributed to John Swann, 1810–1819. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) A round capacity mark with coggled border was found on a few pieces of Swann’s early stoneware, as well as on some post-1847 wares marked “B.C. MILBURN / ALEXA.” The reversed “3” on this fragment from a 3-gallon Swann jug from the Wilkes Street Pottery site is unusual.

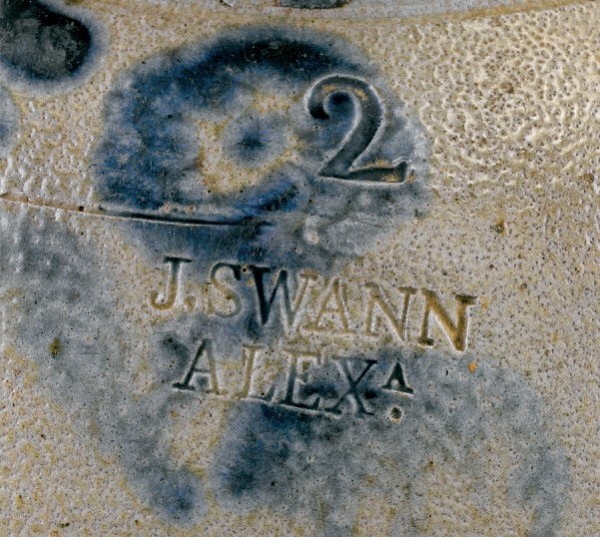

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 16, showing impressed potter’s mark: “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” Stamped in 24-point type. This stamp was found on a plain jug as well as on cobalt-decorated vessels.

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 26, showing impressed merchant’s mark: “HUGH SMITH & CO.” Stamped in 12-point type, this is the only Alexandria mark that employs a frame. Swann appears to have used this merchant mark starting in 1821, when he entered into an agreement by which Smith purchased all of his stoneware.

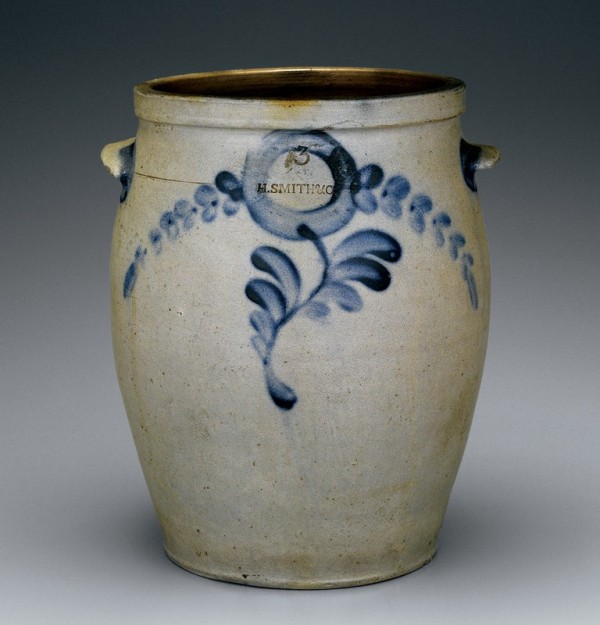

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 29, showing impressed merchant’s mark: “H.SMITH & CO.” Stamped in 26-point type. This mark appears on forty-two sherds from the kiln site, including cobalt-decorated pitchers, cake pots, churns, jars, milk pans, and plain jugs.

Jugs, attributed to John Swann, Alexandria, Virginia, 1810–1819. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left to right) 15", 12", and 15". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) The bulbous shape, ringed neck, and iron wash dipped to the shoulder and dripping down the vessel are all characteristics of Swann’s earliest pottery. The piece at right is a waster from the kiln site; the others were recovered from privies in downtown Alexandria.

Jug, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) The simpler neck form, absence of dipped iron oxide, and impressed mark all indicate a later date than for the objects illustrated in fig. 7. Examples of this neck form were also found at the kiln site.

Pitcher, attributed to John Swann, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This transitional piece, which combines Swann’s earlier brown wash with cobalt decoration, was recovered by archaeologists from excavations in a privy behind the historic Gadsby’s Tavern Museum.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Private collection.) Abstract designs such as this fish-scale pattern are less common than flowers on Alexandria stoneware.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) The three-petal tulip on the front (left) and the stylized round sunflower on the back (right) are the most common flowers depicted on Alexandria stoneware, although they rarely appear on the same vessel.

Churn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. to neck 12". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) The floral decoration extends to the back of the churn.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8 1/4". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) The sparse decoration, representing pairs of leaves, is repeated on the reverse. This vessel was found in a privy at 104 South Saint Asaph Street, along with the stoneware illustrated in figs. 19 and 29.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, Alan Darby.) Paired leaves made with small dabs of color are typical of Swann’s decoration. The design is repeated on the reverse.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Paired leaves made with small dabs of color are typical of Swann’s decoration. The design is repeated on the reverse. The jar was found in a privy on the 100 block of South Royal Street.

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/4". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Private collection.) This elaborate pitcher combines simple paired leaves with a repeated floral motif.

Detail of the decoration on the jar illustrated in fig. 10. As on many of Swann’s pieces, the design is composed of small dabs of color.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Private collection.) Variations of this round flower are used throughout the history of the Wilkes Street Pottery. On this early example, the flowers are made up of short brushstrokes.

Chamber pot, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8 1/4". Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Short dabs of color combine with longer brushstrokes in this leafy design. The chamber pot was found in a privy at 104 South Saint Asaph Street.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1821–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed “HUGH SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) The flower is flanked by branches of long and short leaves, similar to those on the chamber pot illustrated in fig. 19.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1821–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “HUGH SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Similar decoration appears on vessels with the later mark “H. SMITH & CO.” A simple sprig of three leaves appears on the reverse.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Donald Jenkins.)

Churn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) On the reverse is a five-leaf sprig. The wooden dasher and stoneware lid/dasher guide may not be original.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1819–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (Courtesy, Alan Darby.) Small foliate sprigs of three or five leaves are found on the reverse of many early Swann vessels. The front of this jar is decorated with a border of paired leaves at the neck (see fig. 14).

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1821–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed “HUGH SMITH & CO.” (Private collection.) This jar is one of the most elaborate with Hugh Smith’s mark, and a precursor to later vessels with foliage extending across the front of the vessel. The narrow contours of the flower petals reflect Milburn’s later use of the slip-trailing technique.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) The round-flower design becomes more elaborate during this period. Banded rims, on both ovoid and cylindrical jars, appear rarely.

Churn fragment, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. of rim 6". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This fragment was found at the kiln site. New potters or decorators employed by the Smith Company in the late 1820s began to make vessels with more exuberant decoration, such as this one.

Cake pot, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This is a fine example of the central-flower design known as the Alexandria Motif. Decoration during this period reached a new level of sophistication, with the addition of leaves and a more complicated design. This pot was found in a privy at 104 South Saint Asaph Street.

Jar (reverse of the jar illustrated in fig. 37), Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Private collection.) A wavelike design first appears on vessels with this mark.

Jar (reverse of the jar illustrated in fig. 34), Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) A three-petal tulip rotated 90 degrees, as seen on this jar, marks another new design element on the reverse of vessels.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) The well-executed brushstrokes and graduated, curving leaves are typical of the more exuberant style found on vessels with this mark. The chainlike design on the shoulder continues on the reverse. This jar was found in excavations of a privy at 112 South Fairfax Street.

Jar fragment, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. of rim 7 1/4". Capacity: 4 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Vines sometimes encircle an entire vessel or, as on this example, appear just on the front. A five-leaf cluster is on the reverse of this waster from the kiln site. A piece of kiln furniture, used to separate vessels during firing, adheres to the rim.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) The encircling flowers and foliage appear in mirror image above and below a nearly straight line, in an arrangement that continued to be used on vessels with later marks.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1826–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 22". Capacity: 10 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Private collection.) This is one of the most elaborately decorated pots from Wilkes Street. The straight central stem with leafy branches that extend at a 45-degree angle from the base is found only on a signed Jarbour pot (fig. 42) and on jars and churns with the “H.SMITH & CO.” mark. The reverse is completely covered in three-leaf sprigs, with a tulip-like flower at the top.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, William and Jane Yeingst.) This jar combines diagonally arranged branches with a chain border. Chains first appear on the more elaborately decorated vessels of this period and commonly appear on later Milburn vessels.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1826–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Private collection.) In a much simpler version of the Jarbour style, a central flower is again combined with branches extending at 45-degree angles from the base of the stem.

Churn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1826–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, William and Jane Yeingst.) This churn combines elements of the other vessels decorated in the Jarbour style. The design on the neck is also seen on the reverse of a jar from this period (see fig. 30).

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Alan Darby.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed “H.SMITH & CO.” (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1831. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Toby and Oscar Fitzgerald.) While most Alexandria vessels were marked, a few unmarked pieces can be attributed to the Wilke Street Pottery based on form and decoration. The diagonal branches extending from the base and the foliate elements on this piece are similar to other jars of the “H.SMITH & CO.” period.

Jar, David Jarbour, Alexandria, Virginia, 1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 27 3/4", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This exceptionally large pot is the only signed and dated vessel known from Alexandria and may have marked a significant achievement in Jarbour’s career.

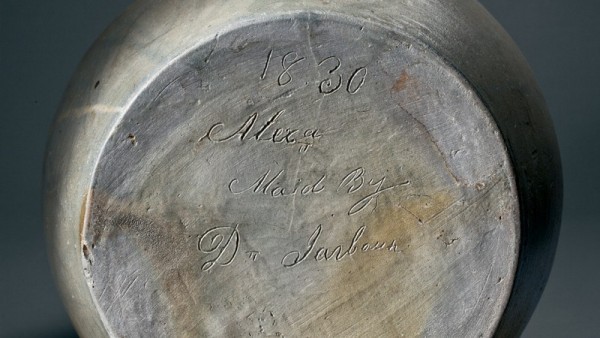

Detail of the base of the jar illustrated in fig. 42. Signed in script on base: “1830 / Alexa / Maid by / D. Jarbour.”

Alexandria, Virginia, is well known for its beautiful nineteenth-century stoneware, often decorated with elaborate designs in brushed or slip-trailed cobalt (fig. 1). It has been said that this stoneware is “among the best-documented and most recognizable of American ceramic products.”[1] Alexandria’s best-known potter is Benedict C. Milburn, who began work at the Wilkes Street Pottery in the early 1830s and purchased the business in 1841.[2] An article on the story of Milburn and his stoneware is slated to appear in the next volume of Ceramics in America. As way of prologue, this article examines the early years of Alexandria stoneware as well as the life of John Swann, the founder of the Wilkes Street Pottery.

Alexandria’s pottery tradition started in 1792, when Henry Piercy came to the city to make earthenware “in the Philadelphia style.”[3] Swann’s introduction to pottery production came a decade later, in 1803, when he was apprenticed to Alexandria potter Lewis Plum. Although Plum made Philadelphia-style earthenware similar to Piercy’s, a few sherds of salt-glazed stoneware have also been found at each of Plum’s manufacturing sites. When Swann opened his own manufactory, he concentrated on the production of stoneware, which was more difficult to make but more desirable to the American public.

The opening of Swann’s “Stone-Ware Manufactory” took place close to one hundred years after stoneware was first produced in America, and more than twenty years after American potters began to use cobalt decoration.[4] American production of stoneware increased in the early nineteenth century, as the ill effects of lead-glazed earthenware became better known. Stoneware gained in popularity with consumers not only because of its safe glaze but also because of its durability, its imperviousness to liquids, and the appeal of its cobalt designs.

Archaeological investigations have shown that in the late eighteenth century many Alexandria households and taverns used some English and German stoneware, primarily jugs and tankards. Only small quantities of these more expensive imported wares have been found on Alexandria archaeological sites, alongside the more common earthenware. While American stoneware does not appear to have reached Alexandria from northern cities in the late eighteenth century, archaeological investigations indicate that a very small quantity of Baltimore stoneware might have reached Alexandria in the early years of the nineteenth century. Thus, Swann was certainly fulfilling an unmet local need when he began the production of stoneware in Alexandria, and the Wilkes Street Pottery continued to do so for three quarters of a century. Very few stoneware imports from Baltimore, the Shenandoah Valley, and elsewhere have been found on Alexandria sites dating to the period in which the pottery was in operation. After it closed in 1876, stoneware was imported from Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley, and industrially produced wares became more prevalent. Swann’s stoneware, and later that of B. C. Milburn, was sold throughout the region, successfully competing with stoneware from Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia.

Swann, Smith, and Milburn at the Wilkes Street Pottery

The Wilkes Street Pottery was owned first by potter John Swann (ca. 1810–1825), then by china and glass merchants Hugh Smith and his sons (1825–1841), and finally by potter Benedict C. Milburn and his sons (1841–1876). Most Alexandria stoneware is stamped with variations of these names, suggesting a neat chronological division of the wares. However, the issue is not so simple, as John Swann and Benedict Milburn both made stoneware stamped for the Smith company. A clearer distinction can be made among stoneware made by Swann and his employees from circa 1810 to 1831, stoneware made under Milburn’s direction from circa 1831 to 1867, and the later wares of Milburn’s sons, from circa 1865 to 1876. The earliest wares were unmarked, but three stamped marks are associated with the period when Swann worked at the pottery: “J.SWANN / ALEXA.,” “HUGH SMITH & CO.,” and “H.SMITH & CO.” Other Alexandria marks, including variations of the names H. C. Smith and B. C. Milburn, were used on stoneware made by Milburn and other employees of the Wilkes Street Pottery after Swann left Alexandria.

Alexandria stoneware can be divided stylistically into five decorative types.

1. Wares with iron wash on the upper portion of the vessel

2. Wares with simple, sparsely brushed cobalt decoration

3. Wares with more exuberantly brushed cobalt decoration

4. Wares with slip-trailed decoration

5. Undecorated wares

The first two types are identified exclusively with the Swann period. The third type is transitional, with the more exuberant decoration first appearing in the late 1820s and continuing, under Milburn’s influence, until the Civil War. This stylistic change may reflect the influence of potters or decorators employed by H. Smith & Co. who worked alongside Swann. The “H.SMITH & CO.” mark, used from circa 1825 to 1831, is found on vessels with simple, sparse decoration as well as on those with more elaborate decoration. The fourth type, slip-trailed decoration, was introduced after 1847 and corresponds only to the Milburn period. Undecorated wares were produced by all of the Wilkes Street potters but predominated in the later years, under Milburn’s sons.

Many examples of the work of Swann and Milburn have survived in private collections, in museums, and even in the homes of descendants of their original owners. Interest in Alexandria stoneware increased after the brief rescue excavation at the pottery in 1977 and the subsequent publication of The Potter’s Art: Salt-glazed Stoneware of Nineteenth-Century Alexandria, produced by the Alexandria Archaeology Museum in conjunction with a 1982 exhibition of the same name.[5]

More recently, articles have been published on the stoneware of two lesser-known Alexandria potters, Tilden Easton and James Miller, but a new analysis of the work of the Wilkes Street potters is, after more than twenty-five years, long overdue.[6] For the current study, digital photography was used to record more than two hundred pieces of Alexandria stoneware in museums and private collections, as well as all of the decorated sherds excavated from the Wilkes Street kiln site and that of Alexandria potter Tilden Easton.[7] The resulting photographs provided a knowledge base from which to reconsider the formal and stylistic characteristics of Alexandria stoneware. By examining hundreds of photographs of whole pots and potsherds, it was possible to recognize a clear progression of vessel forms, rim shapes, and decorative styles and motifs; to correlate these with makers’ marks; to provide more precise dates for the use of the marks and for some of the forms and styles; and to assign more certain attributions to unmarked vessels. Based on this study, it has also been possible to determine which marks first accompany specific designs and formal attributes. There is much variation in the stoneware, however, and the examination of just a single additional pot could challenge some of these assumptions.[8]

Archaeologists have found locally produced stoneware on all of the nineteenth-century sites excavated in the city of Alexandria. Some pots, discovered in deep features such as wells, cisterns, and privies, are nearly complete. At most sites, however, only small sherds have been recovered. Nevertheless, many of these can be firmly attributed to the Wilkes Street potters based on stylistic elements or makers’ marks. Archaeologists have considered additional sherds to be of probable local origin based upon general characteristics of the paste, glaze, and decoration, but potters elsewhere in the region, including Baltimore, the Shenandoah Valley, and other parts of Virginia, may have produced some of the unmarked sherds.

The Beginnings of the Alexandria Stoneware Industry

John B. Swann was born in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, and began his career as a potter on December 20, 1803, when as a fourteen-year-old orphan he was apprenticed to Alexandria potter Lewis Plum.[9] During his seven-year apprenticeship, Swann learned the techniques of both earthenware and stoneware production from Plum, but he concentrated on producing the newer, sturdier stoneware when he opened his own business on Wilkes Street.

Although Plum was primarily a manufacturer of earthenware, he was among the first to experiment with the production of stoneware. Small quantities of stoneware wasters were recovered along with earthenware at the sites of Alexandria’s earliest potters, Henry Piercy and James Fisher. Plum first worked at the Piercy site in 1797 and, with partner Thomas Hewes, took over both the Piercy and the neighboring Fisher potteries in 1799.[10] Plum and James Miller then opened a new pottery, at Prince and Saint Asaph streets, in 1803. This site, which has not been excavated, is where Swann apprenticed. By 1814, Plum had constructed another pottery, on South Columbus Street, where he produced earthenware and, again, a small amount of stoneware.[11] Most of the stoneware sherds from these sites resemble the earliest pottery produced at Wilkes Street by John Swann, with a brown iron-oxide wash, but a few pieces exhibit cobalt decoration.

The Swann Period at the Wilkes Street Pottery

Swann first rented the Wilkes Street property sometime between 1810, when his apprenticeship ended, and 1812, when tax records show “Pot Houses” on the property.[12] In January 1813 Swann purchased the pottery from Jonathan Scholfield.[13] Remarks in the 1820 Census of Manufactures noted that the manufactory had been in operation for ten years.[14] Swann’s first advertisement, for “a large assortment of stoneware,” appeared in the Alexandria Gazette on March 2, 1815.

The business operated on a small scale during its early years. Swann’s second notice in the Alexandria Gazette, on January 28, 1817, complained that “his business will not admit of the employment of many hands, and consequently” he found it necessary “to do the greater part of the work himself. . . .” In the first few years of Swann’s pottery, he manufactured stoneware with glaze that was gray or brown, depending on firing conditions, and usually dipped to the shoulder in an iron-oxide wash (fig. 2).

In August 1819 Swann advertised that “he has been able lately to make a great improvement in his ware, although it has been at considerable expense and labor and he looks to a generous public for support.”[15] The improvement is thought to be the use of cobalt decoration. Just before this announcement was made, the Alexandria deed book recorded that Swann added a third story to his workshop, perhaps for use by the decorators.[16] The same advertisement mentioned “a large assortment of ware, equal to any made in the U.S.” and that “he will warrant his ware to be of good quality which has been acknowledged by the very best judges of those articles.” Swann also stated that his prices were substantially lower than those for Baltimore stoneware.

The 1820 Census of Manufactures describes a potting house with four wheels and two kilns, a warehouse, and a millhouse. With a $60,000 capital investment and $2,000 in expenses for materials and wages, the pottery produced stoneware with a market value of $8,000. Swann is listed as employing six men and two boys, including three slaves and two apprentices.[17] One of the slaves was probably Thomas Valentine, who was emancipated in 1829 by Hugh Smith, a subsequent owner of the business. In Valentine’s emancipation papers, he is listed as a potter by trade, formerly owned by John Swann.[18] David Jarbour may have been another of the men listed in the census. A free black potter, Jarbour was born circa 1788 and was living in Alexandria at least by 1813, when he was first recorded in the Free Negro Registers.[19] One of the apprentices was Thomas Kelley Diment, who was bound to Swann from April 1815 to August 1821.[20] Joshua Farr, who like Swann was formerly bound to Lewis Plum, was bound to Swann from July 1813 until May 1819.[21] His period of indenture would have ended before the census was taken, but he may at that time have been one of the adult male employees. In 1822, Swann advertised for “two journeymen stone ware potters that are good workmen on the wheel.”[22] In that year, B. C. Milburn arrived in Alexandria and may have apprenticed with Swann.

Swann chose an unfortunate time to expand his business, as the Panic of 1819 brought an end to the economic expansion that followed the War of 1812. Banks failed, prices fell, and unemployment rose. Swann was just one of many manufacturers to experience severe business problems during the ensuing depression.

An advertisement on May 3, 1820, again mentioned “the great improvement in his ware,” and listed prices for various sizes of jugs, pots, pitchers, milk pans, churns and chamber pots.[23] But two months later, on July 13, Swann advertised his pottery itself for sale, asking his debtors to come forward so that he could pay his creditors.[24] Some of his larger wholesale customers must have headed his plea, as less than two weeks later Swann thanked his customers in Washington and Georgetown and withdrew the property from sale.[25] However, the property was offered for sale again the following year, on August 22, 1821. “Intending to remove to the western country,” Swann offered “his STONE-WARE MANUFACTORY, together with all its appurtenances, which are in complete order. This Manufactory has been in constant operation for the last ten years, and is as well established as any other of the kind in the United States.” He also offered a nearby building, household and kitchen furniture, and “a large quantity of STONE WARE.” The next day—two days before the public sale was to take place—Swann once again withdrew the property, “having made arrangements, satisfactory to myself, without selling the property advertised in your paper.” In the same notice, Swann goes on to say, “I am also determined to quit ‘Rowing Up sad River,’ and mean to stick close to my business, and will always be happy to serve my customers, on the shortest notice, and with Ware of the best quality.”[26]

These “arrangements” were probably made with Hugh Smith, a customer and prominent china merchant. In November 1821, H. Smith & Co. advanced Swann $500 for the purchase of “all of the sound and merchantable stoneware which the said John Swann should manufacture . . . until the first day of January, 1824 not exceeding a supply equal to their current demands.” The loan was secured with a mortgage on the manufactory.[27] Swann failed to meet the terms of the loan, and on March 22 announced that he had “disposed of his stoneware manufactory to Mssrs. Hugh Smith & Co., with all his stock,” and that Hugh Smith & Co. had “started the business on a large scale.”[28] It was not until March 1825, after Swann had spent a short time in prison as an insolvent debtor,[29] that H. Smith & Co. formally foreclosed on the loan, forcing a sale of Swann’s property at auction. The buyer was James Douglas Jr., a commission agent, who may have been acting as an agent for Smith, as he conveyed the property to him six months later for $200.[30]

While Swann’s business had fallen on hard times, his stoneware must have been well known and considered to be of good quality, because Hugh Smith & Co. mentioned him by name in an 1823 advertisement for “a general assortment of excellent Stone Ware, made by John Swann.”[31] Following the 1821 agreement and the 1822 “disposal of his stoneware manufactory to Mssrs. Hugh Smith & Co.,” most or all of Swann’s wares were probably stamped “HUGH SMITH & CO.”

The Smith Period at the Wilkes Street Pottery

Hugh Smith was a prominent Alexandria merchant, importing goods as early as 1796.[32] He opened a retail shop on the north side of the 200 block of King Street by 1803, specializing in china and glass. In 1815 he took his nephew Thomas Smith as partner in a venture called Hugh Smith & Co.[33] Robert H. Miller opened another china and glass shop on the 300 block of King Street in 1822, and three years later advertised “Stoneware of Alexandria manufacture, of excellent quality.”[34]

In January 1825, a few months before Smith foreclosed on Swann’s Pottery, a new business partnership was formed, known as H. Smith & Co. and consisting of Hugh, his nephew Thomas, and his sons Hugh Charles and James P. Smith. The Smiths enlarged and improved the manufactory, and its tax assessment rose from $600 to $2,000 between 1825 and 1826. The stoneware produced there became more exuberantly and elaborately decorated in this period, suggesting the work of specialized decorators and perhaps the business acumen of the Smith family. Production also expanded in the late 1820s to include the manufacture of earthen furnaces.[35] Thomas left the company in 1830, and in 1831 when the elder Smith, age sixty-two, dissolved the partnership, Hugh Charles took over management of the business. Stamped merchant marks were used on most, if not all, of the wares produced during the time that the Smith Company owned the Wilkes Street Pottery. Based on documentary and stylistic evidence, it appears that the “HUGH SMITH & CO.” mark was used from circa 1821 to 1825, and “H.SMITH & CO.” from 1825 to 1831.

The names of two additional employees appear in tax rolls from the late 1820s: David Jarbour, 1826–1833 and 1841, and Michael Morris, 1828–1833. The role of each worker at the pottery is unclear, although Jarbour, a free black man, is known to have been a potter. Morris and others listed in later tax rolls may have also been turners, or they may have worked as laborers, helping to mill the clay, stack the kiln, and so forth. Swann, Jarbour, and other turners may have decorated their own pots, or the pottery may at times have employed specialized decorators, possibly women, as was the practice elsewhere. The first female employees are listed in the tax rolls of 1832, but earlier records may be incomplete.

Swann appears to have remained an employee of the pottery even after 1825, when Smith foreclosed on Swann’s loan and purchased the property, but whether Swann worked there continuously or only periodically between 1825 and 1831 is unknown. He had also lost his nearby home in the foreclosure, and Smith rented it to others for a few years. Swann himself rented this house in 1830 and during part of 1831, but at some point that year it was rented to his replacement, potter B. C. Milburn.[36]

Milburn is first listed in tax rolls for the Wilkes Street Pottery in 1833, and an 1869 advertisement stated that “Milburn’s Pottery” was “Established 1833.”[37] It appears that Swann left Alexandria and the pottery around 1831, but certainly by 1833 he was gone. His later whereabouts are unknown. Milburn worked for H. C. Smith until 1841, when he purchased the business.

Archaeology of the Wilkes Street Pottery

Archaeological knowledge of Alexandria stoneware comes largely from brief rescue excavations conducted in the spring of 1977 at the site of the Wilkes Street Pottery, before the construction of the Tannery House condominiums. Alain C. Outlaw of the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology (now part of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources) directed the excavations, working with a group of volunteers on four weekends. Unfortunately, the site was extensively disturbed by construction and by pothunters who looted the site during the intervening weekdays. Excavating three areas of the site, archaeologists recovered thousands of stoneware wasters, kiln furniture, bricks from the kiln, and a small portion of a brick kiln arch that was no longer in situ. Near the front of the lot the excavation revealed one corner of a nineteenth-century brick foundation, which may have belonged to the pottery workshop. Around 1,350 potsherds were recovered from this portion of the site. More than 14,500 sherds were recovered from three areas at the back of the lot, where portions of large waster piles had been exposed by construction activities. One area contained mostly stoneware with an iron-oxide wash on the neck and shoulder, indicative of Swann’s early wares. The other two areas contained primarily cobalt-decorated wares. About 1,500 sherds from this site have cobalt decoration, representing more than 100 distinct vessels. Most of the sherds are of salt-glazed stoneware, but more than 400 of them were from earthenware flowerpots and milk pans.[38]

Alexandria possessed a good source for clay, a large population, and a well-functioning transportation network, so it was only natural that potters would settle there. In 1785 an early Italian visitor to the United States, Count Luigi Castiglioni, described the city: “Alexandria then had various factories for the manufacture of bricks, which as the surrounding land was of soft, strong clay, could be made very cheaply.”[39] Clay sourcing and firing experiments have shown that the same local clay was suitable for both earthenware and stoneware. A large cretaceous clay formation stretches across the edge of the Chesapeake Bay region and includes Alexandria and Baltimore. Local potters could have obtained their clay anywhere in this region, and an 1855 newspaper account records that Milburn later acquired clay from Baltimore.[40] Most Alexandria stoneware is of a medium brownish-gray color, but Swann’s earliest decorated wares are a lighter, clearer gray color, probably indicating the use of imported clay. Cobalt-decorated wares with the marks “J.SWANN / ALEXA.,” as well as some of the vessels marked “HUGH SMITH & CO,” are made of the lighter clay.

Pottery Stamps

The collection from the kiln site includes sixty-three stamped sherds. The only “J.WANN / ALEXA.” mark is on an unidentified vessel form, probably a jug or jar. Five “HUGH SMITH & CO.” sherds represent fragments of pitchers and a jug. The most common stamp, “H. SMITH & CO.,” appears on forty-two sherds, from pitchers, cake or butter pots, jars, milk pans, jugs, and a churn. Eighteen of these were from stratified deposits associated with the excavated kiln fragments,[41] while the other marked sherds were from surface collections. The remaining fifteen stamped sherds had later marks, dating to the Milburn period.[42]

Swann did not use a maker’s mark on his earliest wares, which were decorated with an iron wash between circa 1810 and 1819. Some, however, do carry a capacity mark in a round stamp with a cogged border. This style of stamp is found as a reversed “3” on a jug sherd from the kiln site (fig. 3), and as “1 1/2” on a sherd from the kiln and a jar in a private collection. The same style of a 1 1/2-gallon mark is used later on some Milburn pots.

All or most of Swann’s cobalt-decorated stoneware was stamped with makers’ or merchants’ marks. Plain capacity marks, without the round border, were also sometimes used on these decorated wares. The maker’s mark “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (fig. 4) might have been used only from 1819 until November 1821, when Hugh Smith began to purchase all of Swann’s “sound and merchantable stoneware,” or until March 1822, when Smith took over the business. Twelve cobalt-decorated vessels with Swann’s stamp were examined for this study, including seven ovoid jars and one straight-sided jar, a churn, a pitcher, a milk pan, and a chamber pot. The same stamp also appears on a plain jug (see fig. 8). Only a single Swann mark was found at the kiln site.

Swann used the merchant’s mark “HUGH SMITH & CO.” at least from late 1821 or early 1822 until 1825, while he was supplying all of his stoneware to Smith. This mark may also have been used earlier, alongside “J. SWANN / ALEXA.,” as Hugh Smith was already Swann’s customer before they entered into the agreement of 1821. The “HUGH SMITH & CO.” stamp is the only one from Wilkes Street within an elaborate frame and uses much smaller type than the other stamps (fig. 5). Capacity marks are stamped, or sometimes scratched freehand, into the surface. While few pieces survive today with the mark “J.SWANN / ALEXA.,” even fewer are marked “HUGH SMITH & CO.” For this study, just three decorated pieces with this early Smith mark were examined, including two jars and a milk pan. The mark was also recorded on a plain jar and on five sherds from a jug and pitchers, all found at the kiln site.

The “H.SMITH & CO.” stamp, seen on twenty-two decorated vessels, was probably first used in 1825 (fig. 6), when the new partnership assumed that name. In the same year, the company foreclosed on Swann’s Pottery. This mark was likely in use until 1831, when the company took the name of Hugh’s son, H. C. Smith.

Decoration

Swann’s stoneware made before 1819 was usually embellished with an iron wash. Most of the stoneware produced between 1819 and 1831 was decorated with brushed cobalt, first with simple, sparse decoration and later with more exuberant designs. Undecorated jugs, and a smaller number of other plain utilitarian wares, were made throughout the manufactory’s history. Alexandria stoneware is noted for its distinctive and beautiful cobalt decoration, although the latter was never mentioned in contemporary advertisements. Instead, the decorated wares themselves served as advertisements for the potter or merchant whose name was stamped on the vessel.

IRON WASH

Swann’s earliest stoneware was dipped to the shoulder in a brown iron-oxide wash, which was often allowed to drip down the sides of the pot (fig. 7), in a surface treatment that was common in Germany and England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[43] Among Swann’s pots, iron-washed surfaces are seen on ovoid jugs and jars, and on pitchers and chamber pots. Most of these vessels are unmarked but attributed to Swann because of the numerous examples found at the kiln site.

The color of this early stoneware ranges from a light orange-tan to a medium gray, due to poorly controlled firing conditions. Many of Swann’s early vessels have uneven coloration, but his production techniques improved considerably in later years. The intended color was gray, caused when oxygen is drawn out of the clay in the reducing atmosphere of the hot stoneware kiln.[44] These early wares were not stamped with a maker’s mark, but some surviving heirloom pieces have been identified in museums and private collections, as they are quite distinct from stoneware produced by other Virginia and mid-Atlantic potteries.

Iron-oxide wash was phased out with the introduction of cobalt decoration circa 1819, but undecorated utilitarian wares were manufactured, to a lesser extent, throughout the history of the Wilkes Street Pottery. A grayish-brown jug, probably from the 1820s, is stamped “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” beneath an incised line at the shoulder. This jug has a narrow neck with a rounded rim (fig. 8), rather than the ringed neck found on earlier examples. The vessel might correspond to Swann’s 1820 advertisement, which offered jugs in seven sizes, from one-third of a gallon to three gallons.[45]

One unmarked pitcher, found in excavations at Gadsby’s Tavern, appears to be a transitional piece, incorporating brown wash with use of the newer cobalt decoration (fig. 9). This pitcher, the only piece known to combine the two techniques, is probably an Alexandria pot made by John Swann or his mentor, Lewis Plum.

COBALT DECORATION

In 1819, when Swann advertised “a great improvement to his ware,”[46] he replaced his earlier decorative style with simple but attractive floral and foliate designs in brushed cobalt. While American stoneware was manufactured at least by the 1720s, blue decoration was probably not used much before 1787, when cobalt pigment was first commercially produced in this country.[47] The blue cobalt pigment is a fine powder ground from smalt glass, which is produced by combining cobalt ore with potash and sand. The powder was mixed with water and brushed onto the surface of the vessel.[48]

Another improvement during this period was in the quality of the clay. A lighter, more even gray color is found on decorated stoneware with the marks “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” and “HUGH SMITH & CO,” probably indicating the use of nonlocal clay as well as better control of the firing temperature. This finer clay was used only for a brief period of time and is not seen in vessels with later marks.

Flowers and foliage adorn nearly all decorated Alexandria stoneware. A few pieces of marked Alexandria stoneware have designs that are more abstract, including wavy lines and fish-scale patterns (fig. 10). Swann did not use other representational designs, although a pitcher depicting a face was possibly made by Plum, and a jar with a ship and tree is attributed to B. C. Milburn.[49]

Stylized round sunflowers and three-petal tulips are the most common flowers depicted on the earliest Swann vessels through the latest decorated Milburn pieces. Decorations generally consist of a central stem and flower, facing directly outward (fig. 11). The stylized sunflower, consisting of a plain round circle on a stem with leaves, is a distinctive Alexandria design commonly referred to as the “Alexandria Motif.”[50] Small decorative elements are usually found on the back of the vessel, although occasionally full-scale floral designs are used on both the front and back.

Some vessels, from the earliest Swann to the latest Milburn wares, have foliage that winds around the shoulder of the vessel (fig. 12) on the front, with small foliate sprigs on the reverse; less commonly, the decoration on the front may continue around the vessel. The foliage is generally combined with tulips but occasionally with other flowers.

SPARSE DECORATION

The earlier style of cobalt decoration, employing simple designs, is found with all of the marks from the Swann period: “J.SWANN / ALEXA.,” “HUGH SMITH & CO.,” and “H.SMITH & CO.” This last mark is associated most often with the later, more elaborate decoration, indicating a shift in style while this mark was used, between 1825 and 1831.

Very short dabs of cobalt make up the designs on much of the earliest decorated stoneware. The simplest decoration is seen on a Swann milk pan with pairs of blue dabs (fig. 13). It becomes more obvious that the short strokes of color represent leaves as the designs become more complex and the paired leaves form a garland (figs. 14-16). Short brushstrokes also merge to form linear patterns (fig. 17), and even circular flowers (fig. 18). This use of small dabs of color to create longer lines appears only on vessels with the “JSWANN / ALEXA.” mark, and is an unusual form of stoneware decoration. On some vessels, short strokes are combined with floral and other elements executed with longer brushstrokes (see figs. 1 and 19). A few marked Swann vessels are decorated only with long brushstrokes (fig. 11) and may have been decorated by a different employee of the pottery.

On some vessels there is no central floral element, but the stems of branching foliage meet at the midpoint of the pot. The branches of long and short leaves on a marked Swann chamber pot (fig. 19) are similar to those on a Hugh Smith milk pan (fig. 20). On the latter, the central round flower resembles a sunflower or daisy, with small petals around a large circle. While less common than the plain round flower, this version of a blossom continued to be used on Alexandria stoneware from the Smith and Milburn periods.

Nearly identical versions of the central round flower motif are found on ovoid jars marked “HUGH SMITH & CO.” (fig. 21), and on ovoid and cylindrical jars and a churn marked “H.SMITH & CO.” (figs. 22-24). In this early version of the Alexandria Motif, a round flower is on a short stem with two leaves, flanked by curving branches of short dabbed leaves. In a variation, short leaves are replaced with a trio of longer leaves. These vessels are decorated on the reverse with one small foliate sprig of three or five leaves (fig. 25).

EXUBERANT DECORATION

Sometime around 1825 the decoration reached a new level of sophistication, with more abundant leaves and more complicated designs. This more elaborate style appears on at least one jar with the “HUGH SMITH & CO.” mark (fig. 26) but is common on those marked “H.SMITH & CO.” During this period, the Alexandria Motif reached its most mature form, with graduated leaves on a curving stem and branches springing from the sides of the flower (figs. 27-29). This style continued to be used in later periods, when the Wilkes Street Pottery was managed, and later owned, by B. C. Milburn.

In the late 1820s, the work of different potters and decorators appears more clearly. Also in this period, new elements of design appear on the reverse of vessels, including chains, waves, and three-petal tulips as well as combinations of these elements (figs. 30, 31). The more exuberant decoration and novel designs may reflect new ideas incorporated by Swann or innovations by Smith, who was interested in the commercial success of the manufactory, or they may reflect the ideas of new potters who came to work in Alexandria in the 1820s. B. C. Milburn may have worked at Wilkes Street as early as 1822; David Jarbour joined the pottery in 1826; Michael Morris began work in 1828; and unnamed decorators might have worked alongside these potters. Although women may have been employed as decorators, women are not listed in tax rolls until later, in the 1830s.

The straight-sided “H.SMITH & CO.” jar in figure 32 has well-executed brushstrokes and graduated, curving leaves typical of this period. These elements are repeated in the encircling foliage illustrated in figure 33.

In figure 34, the flowers and foliage are arranged in mirror image above and below a more or less straight line and extend all the way around the shoulder of the vessel. This arrangement continued to be used with later marks.

THE JARBOUR STYLE

In a variation of the more exuberant style, a central flower appears on a straight stem, with straight branches springing from the stem’s base at a 45-degree angle (figs. 35-41). A variety of flowers and foliage is used as the central design feature, and the central stems may be plain or flanked by graduated leaves. The straight stem with angled branches design was used only with the “H.SMITH & CO.” mark, between circa 1825 and 1831.

This substyle is intriguing in that it includes a rare dated vessel signed by a black potter, David Jarbour. He left just one signed example of his work, but it is an exceptional piece (fig. 42). At nearly twenty-eight inches tall, this may be the largest Alexandria pot. On the base is the freehand inscription “1830 / Alexa / Maid by / D. Jarbour” (fig. 43). This pot shows that Jarbour was a skilled craftsman, and that the role of African Americans in the potting industry was in no way limited to menial labor. Any sort of inscription is rare on Alexandria pots, and this is the only piece that uses the words “Maid [sic] by,” indicating, along with the large size, a milestone in Jarbour’s career, perhaps recognition as a master potter.[51] It cannot be said for certain whether Jarbour actually decorated this jar in addition to throwing the pot, or whether a specialized decorator worked with him. In any case, there appears to be a definite Jarbour style, as the same person appears to have decorated not only the inscribed Jarbour pot but also several other vessels with the “H.SMITH & CO.” stamp.

Born enslaved in 1788, David Jarbour purchased his freedom from Alexandria merchant Zenas Kinsey in 1820, for the sum of $300. Potter Lewis Plum is listed as a witness to this manumission.[52] It was not uncommon in Alexandria and other urban areas for slaves to be hired out, and Jarbour may have worked for Plum, learning the pottery trade from him alongside John Swann. Jarbour’s name is listed in the tax records below Hugh Smith each year from 1826 to 1833 and again in 1841, indicating that he worked with both Swann and Milburn.

Vessel Forms

Eight vessel forms are known from this period. Jars are the most common, followed by pitchers and jugs, while churns, milk pans, chamber pots, and cake and butter pots are less common forms. Earthen furnaces were advertised but have not been found. Banks, chimney pots, coolers, cups, bowls, flowerpots, spittoons, and stovepipe collars were apparently not made at Wilkes Street until after Swann left in 1831, according to documentary and physical evidence.

CAKE POTS AND BUTTER POTS

Cake pots and butter pots are two names given to wide-mouthed, cylindrical, lidded jars. According to illustrations on an 1862 price list from another American pottery, cake pots are wider than they are tall, while butter pots are taller than they are wide.[53] An 1895 Baltimore price list, however, illustrates the shorter form as a butter pan. Only a few extant examples were recorded, but rim fragments from twenty-eight pots were recovered from the kiln site, including seven rims stamped “H.SMITH & CO.” An “H.SMITH & CO.” cake pot (fig. 29) and fragments of a butter pot from the kiln site both have well-executed versions of the round flower motif in its mature form. Cake pots were designed to store long-lasting fruitcakes, while butter pots were intended for the storage of butter or lard, but in reality these pots were probably used to store a variety of foodstuffs.

CHAMBER POTS

Chamber pots from the Wilkes Street Pottery have flat, everted rims. A chamber pot marked “J.SWANN / ALEXA.,” with sparse leafy decoration, was found at an archaeological site in Alexandria (fig. 19). In 1820 Swann advertised wholesale prices for two sizes of chamber pots, charging $2.33 per potter’s dozen for large pots and $1.50 for “less” or child-sized pots.[54] Six chamber-pot rim fragments, representing small and large sizes, were recovered from the kiln site, and unmarked chamber-pot fragments have been identified at other Alexandria sites. Some unmarked chamber pots, with Swann’s typical iron-oxide wash covering the rim and shoulder, have also been found.

CHURNS

Churns from Wilkes Street are tall and cylindrical, with lug handles. They have shallow or deep cup-shaped rims, or in some instances flared rims that form a ridge at the neck to support the dasher guides. The lid or dasher guide, made of stoneware or wood, had a hole in the middle to support the handle of the cross-shaped dasher used to churn the butter (fig. 24). Pieces of four churns were found at the kiln site, including a fragment of an early Swann churn with an iron wash and a deep cup-shaped rim and a fragment marked “H.SMITH & CO.” Among the extant stoneware vessels, one churn was recorded with the “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” mark (fig. 12), and three with the “H. SMITH & CO.” mark (figs. 24, 28, and 38). Swann’s 1820 advertisement offered churns in two-, three-, and four-gallon sizes.

JARS

Jars, the most common form of Alexandria stoneware, show the greatest variation in shape and in the treatment of handles and rims. The earliest jars have an ovoid form and an iron wash. Archaeologists found fragments of at least sixty-three jars at the kiln site, including some with Swann’s iron wash and nine sherds marked “H.SMITH & CO.” Although most of the decorated jars continued to be ovoid in form, cylindrical jars have also been found with the “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” and “H.SMITH & CO.” marks (figs. 23 and 32).

Both the ovoid and cylindrical forms are wide-mouthed jars, with an opening about the same size as the base. Cylindrical jars and the smallest ovoid jars do not have handles, while ovoid jars of one-gallon or larger capacity have lug handles with square, cutoff ends. Capacity marks range from one half to six gallons, with the smaller sizes more common.

Most jars from Wilkes Street have the plain round rim that continued to be used from Swann to Milburn, although a few of the early ovoid jars with iron wash have a flat rim with an angled profile (fig. 2). A banded rim was recorded on both ovoid and cylindrical jars (figs. 18 and 27). When used in the kitchen or pantry, the jars were probably covered with muslin, which was tied with string around the neck. Tall, slightly flared rims, which may have supported stoneware lids, were used on a few squat ovoid jars produced in the years the pottery was operated by Swann and Milburn (fig. 11).

JUGS

Made to hold liquor and various other liquids, jugs have strap handles and narrow necks. Swann’s early jugs are unmarked, ovoid in shape, and dipped to the shoulder in iron wash. They have ringed necks in one of two forms: with the widest ring at the top, or with the widest ring at the center of the neck (fig. 7). The necks of these jugs are similar to examples found at the earlier Piercy and Fisher sites and attributed to Swann’s mentor Lewis Plum.

After about 1819 Swann made both plain and cobalt-decorated jugs, marked “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” (fig. 8). A marked “H.SMITH & CO.” jug (not illustrated) has a narrow, straight neck and the typical Alexandria round flower with pairs of small dabbed leaves, similar to the design shown in figures 21 through 24.[55] Although decorated jugs are quite common in the Shenandoah Valley and elsewhere in America, they are rare in Alexandria. These later jugs have longer necks with one ring at the lip.

Fragments of ninety-seven jugs were found at the kiln site, mostly with earlier ringed-neck forms from the Swann period. Seven jug fragments with the “H.SMITH & CO.” mark and later neck forms were also found at the kiln site.

MILK PANS

Milk pans have a wide opening and a pouring spout designed for milk separation, but these pots could have been used for many purposes. All Alexandria stoneware milk pans were probably decorated with cobalt. They have steeply sloping sides and either a square rim defined by an incised line or a flat rim that protrudes only slightly from the vessel wall (figs. 13, 20). The earliest mention of milk pans appears in Swann’s advertisement of May 9, 1820, which offered half-, one-, and two-gallon sizes. Lead-glazed earthenware milk pans were also made at Wilkes Street. Three stoneware milk-pan rims and one of black-glazed earthenware were found at the kiln site with the “H.SMITH & CO.” mark.

PITCHERS

Alexandria pitchers of this period have a baluster shape, with an ovoid bottom and a straight or slightly flaring neck, and a pouring spout that extends the full height of the neck (figs. 1, 9, and 16). All of the known examples have cobalt decoration. Fourteen pitcher-rim fragments with the “H.SMITH & CO.” mark were found at the kiln site.

PORTABLE EARTHEN FURNACES

An 1829 advertisement by H. Smith & Co. for “a large assortment of earthen furnaces just finished of their own manufacture and at the lowest prices” refers to charcoal-burning furnaces that typically had iron hoops and, sometimes, iron bale handles. Similar items made by Philadelphia potter Andrew Miller had been advertised in Alexandria five years earlier. Furnaces of this type were intended for use in summer so that cooking could take place in the yard and the house would remain cool. They were also noted for using very little fuel.[56] Robert H. Miller advertised a “case of cooking furnaces, for preserving, assorted sizes” in the Alexandria Gazette in 1840.[57] Furnaces were probably not marked and were unlikely to be kept as heirlooms. No recognizable fragments have been found at the kiln site or on other archaeological sites in Alexandria.

John Swann struggled with his business but set the stage for the Wilkes Street Pottery to become the most successful stoneware manufactory in the region under the management of his successor, Benedict C. Milburn.

The earlier wares with iron wash and those with simple cobalt decoration, are clearly the work of Swann and distinguishable from other stoneware of the Virginia/Maryland region and from the later works of Milburn. Therefore, unmarked sherds from the period prior to 1825 can be recognized as Swann’s products when found on archaeological sites in Alexandria and surrounding areas.

The more exuberant and sophisticated brushed-cobalt decoration used after 1825 on some of the stoneware marked “H.SMITH & CO.” continued to be produced in the Milburn period through the 1850s. The forward-facing flower of the Alexandria Motif might be unique to Alexandria. However, the brushwork of this later period is similar to that used by other potters in the region, so the attribution to Alexandria of small unmarked stoneware fragments from this period is problematic.

Recent illustrated articles in Ceramics in America and elsewhere, and the ability to view stoneware from many regions on internet auction sites, have helped place the wares of John Swann and the Wilkes Street Pottery in a broader context. Future illustrated publications on American stoneware will continue to shed further light on Swann’s place in manufacturing history.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the staff of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and the volunteers who helped to excavate, wash, and catalogue many of the stoneware fragments examined for this article. I am grateful for the earlier research on Alexandria potters conducted in the 1960s and 1970s by Suzita C. Myers, C. Malcolm Watkins, John K. Pickens, Dennis Pogue, and Robin Ruffner. Last, I am indebted to the many collectors who shared their collections and their expertise.

Robert Hunter, Kurt C. Russ, and Marshall Goodman, “Stoneware of Eastern Virginia,” The Magazine Antiques 167, no. 4 (April 2005): 126–33. In the 1960s, C. Malcolm Watkins, then a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History), undertook a study of Alexandria’s potters. As part of this study, Richard J. Muzzrole excavated test pits at several pottery sites (although not at Wilkes Street), and Betty J. Walters assisted Watkins in researching the history of the potters. In 1977, Alain C. Outlaw of the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology directed brief rescue excavations at the site of the Wilkes Street Pottery. In the late 1970s, Suzita Myers, Robin Ruffner, and others conducted additional research on Alexandria potters. Watkins and Jack Pickens, the first chairman of the Alexandria Archaeological Commission, each produced unpublished manuscripts, now in the files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and the Alexandria Library, Local History/Special Collections. Myers went on to write The Potters’ Art and a master’s thesis based on the finds from the Wilkes Street Pottery excavation (see note 5 below).

American potteries in the early nineteenth century often did not have names themselves but were referred to by the potter’s name. Advertisements for the Wilkes Street Pottery (the name given by archaeologists and commonly used today) in the Alexandria Gazette refer generally to the “Stone-Ware Manufactory” (March 2, 1815) and the “Alexandria stone ware manufactory” (January 28, 1817).

Alexandria Gazette, November 1, 1792. Barbara H. Magid and Bernard K. Means, “In the Philadelphia Style: The Pottery of Henry Piercy,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 69–71.

Alexandria Gazette, March 2, 1815.

Suzita Cecil Myers, The Potters’ Art: Salt-glazed Stoneware of Nineteenth-Century Alexandria, 2nd ed. (1983; Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Archaeology Publications, 2003); Suzita Cecil Myers, “Alexandria Salt-Glazed Stoneware: A Study in Material Culture, 1813–1876” (master’s thesis, University of Maryland, 1982); and Dennis J. Pogue, “An Analysis of Wares Salvaged from the Swann-Smith-Milburn Pottery Site (44AX29), Alexandria, Virginia,” Archaeological Society of Virginia Quarterly Bulletin 34, no. 3 (1980): 149–59. An overview of Alexandria earthenware and stoneware potters appears in Barbara H. Magid, “An Archaeological Perspective on Alexandria’s Pottery Tradition,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 21, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 41–82.

Barbara H. Magid, “A New Look at Old Stoneware: The Pottery of Tildon Easton,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 249–52; and Brandt Zipp and Mark Zipp, “James Miller, Lost Potter of Alexandria, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 253–61.

Alexandria stoneware examined for this article is in the collections of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum; The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum; National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, N.C.; the DAR Museum, Washington, D.C.; and in nine private collections. Photographs from online auctions have also been examined.

Eddie Wilder, Alexandria, Virginia Pottery, 1792–1876 (Marceline, Mo.: Walsworth Publishing Company, 2007), published some months after the completion of this article, provides a comprehensive history of the Wilkes Street Pottery and illustrates several hundred examples of Alexandria stoneware. Additional stoneware examples illustrated in Wilder’s book appear to confirm the analysis provided here.

Wilder, Alexandria, Virginia Pottery, p. 30; and Apprenticeship Indenture, Levy Court for Alexandria County, December 20, 1803, records of the Alexandria Circuit Court.

C. Malcolm Watkins, “The Pots and Potteries of Alexandria, Virginia, 1792–1876,” pp. 13–16, unpublished manuscript, files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum; and Magid and Means, “In the Philadelphia Style,” pp. 47–86. Richard Muzzrole, under the direction of Smithsonian Institution curator C. Malcolm Watkins, excavated test pits at the Piercy and Fisher Pottery sites in the 1960s. Collections from the Piercy and Fisher sites are divided between the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution and the Alexandria Archaeology Museum. The latter institution conducted further excavation at the Piercy Pottery in 1999 and holds these collections.

John K. Pickens, “Early Alexandria Craftsmen: Lewis Wilson Plum, the Potter in the Dip” (1979), files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and the Pickens Papers, box 57, Alexandria Library, Local History/Special Collections; and Magid, “An Archaeological Perspective on Alexandria’s Pottery Tradition.” In 1975 pottery and sections of kiln flooring from the Lewis Plum site, located on South Columbus Street between Wolfe and Wilkes streets from 1814 to 1828, were discovered six to seven feet below the present ground surface in a twenty-foot-long backhoe trench, and additional finds were collected in 1979 and during construction in 1983. These are in the collections of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.

Watkins, “The Pots and Potteries of Alexandria,” p. 20.

Alexandria Deed Book Z, pp. 146–50, January 28, 1813, records of the Alexandria Circuit Court. The deed specified that “Scholfield will accept $500 for the property and rent shall cease.”

Census of Manufactures, original schedules of the Fourth Census, 1820, National Archives, Record Group 29, Washington, D.C.

Alexandria Gazette, August 6, 1819. The same advertisement appeared in several other papers, including the Alexandria Herald, August 11, 1819, and the Palladium of Liberty, September 3, 1819.

Alexandria Deed Book S-2, p. 229, July 29, 1819.

Census of Manufactures, 1820.

“Be it known to all men that we the subscribers have this day manumitted and set free and by those present do manumit and set free a certain slave named Thomas Valentine, a potter by trade, formerly owned by John Swann, as witnessed on hands and sealed this 12th day of Nov. 1829. Hugh Smith, Hugh A. Smith, Thos. Smith.” Alexandria Deed Book R-2, p. 466.

Alexandria County: Virginia Free Negro Registers, 1797–1861, abstracted and indexed by Dorothy S. Provine (Bowie, Md.: Heritage Books, 1990). Jarbour is listed in vol. 1, p. 57, register no. 72, February 21, 1821, as “a black man, about 33 years old, who has a slight scar on the forefinger of the right hand.” He was living in Alexandria at least by March 21, 1813, when the register records him as the husband of Rebecca Dover.

Alexandria County, Virginia Apprenticeship Indentures, 1808–1817, April 8, 1815, original Orphans Court ledger, pp. 252–53, compiled by Wesley E. Pippenger and reprinted in The Virginia Genealogist 39, no. 2 (April–June 1995): 117–26, and no. 3 (July–September 1995): 171–80. “Ordered that Thomas Kelley Diment an orphan boy who will be fifteen years old the fifth of August must by the advice and consent of Elizabeth Diment—his mother be bound and he is hereby bound an Apprentice to John B. Swann until he arrives to the age of twenty one years to learn the Art trade and Mystery of a Potter. During all which time the said Apprentice his said Master doth agree faithfully to serve his secrets keep his lawful commands gladly obey, he shall do no damage to his said Master nor willingly see it done by others without letting or giving notice thereof to his said Master he shall not waste his said Masters goods nor lend them unlawfully to others but in all things and in all respects behave himself as a good and faithful Apprentice ought to do during the said term. And the said John B. Swann on his part doth obligate and oblige himself to instruct the said Apprentice in the Art trade and Mystery of a Potter, during the said term to furnish him with good and sufficient meat drink apparel washing and Lodging and teach him or cause him to be taught to read write and Cypher through the Rule of three and at the end separation of the said term pay him twenty dollars for freedom dues.”

Apprenticeship Indentures, July 13, 1813, original Orphans Court ledger, pp. 173–74.

Alexandria Gazette, March 7, 1822.

Alexandria Gazette, May 9, 1820. The prices per dozen are listed as follows, with a liberal discount for cash:

3 gallon jugs, pots & pitchers $6.00

2 do do do 4.50

1 1/2 do do do 3.25

1 do do do 2.50

1/2 do do do 1.75

1/4 do do do 1.00

1/3 do do do .50

2 gallon milk pans 4.00

1 do do 2.25

1/2 do do 1.50

4 gallon churns 9.50

3 do do 8.00

2 do do 6.00

Large chamber pots 2.33

Less do do 1.50

Alexandria Gazette, July 13, 1820.

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), July 25, 1820.

Alexandria Gazette, August 23, 1821.

Alexandria Deed Book L-2, p. 374, November 27, 1821.

Alexandria Gazette, March 22, 1822.

Wilder, Alexandria, Virginia Pottery, pp. 34–35.

Alexandria Deed Book P-2:55, August 1, 1825; and Alexandria Gazette, March 21, 1825.

Daily National Intelligencer, May 1, 1823.

Alexandria Gazette, April 14, 1796.

Alexandria Gazette, June 3, 1815.

Alexandria Gazette, July 14, 1825.

Alexandria Gazette, October 15, 1829.

John K. Pickens, “Master Potters or Merchant Princes,” files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and the Pickens Papers, box 57, Alexandria Library, Local History/Special Collections.

Alexandria Gazette, February 19, 1869.

Myers, “Alexandria Salt-Glazed Stoneware,” pp. 57–61.

Howard R. Marraro, “Count Luigi Castiglioni: An Early Italian Traveler to Virginia (1785–1786),” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 58 (Richmond: The Virginia Historical Society, 1950), p. 483.

In the early 1980s, Suzita C. Myers successfully fired some local Alexandria clay at stoneware temperatures. Allison Stenger of Portland State University’s Ceramics Analysis Laboratory tested a potsherd from each of Alexandria’s earthenware and stoneware pottery sites using spectrographic analysis. This preliminary study found the clay from all of the fired pottery to be similar to the local clay. A 1978 U.S. Geological Survey map of regional geology in the Middle Atlantic states shows a region of cretaceous sediments known as the Potomac Group outcrop belt, which stretches along the outer Chesapeake Bay region, through Alexandria and Baltimore. The map identifies clay deposits, predominantly kaolinite and illite, in the areas of both cities. The map is reproduced in Myers, “Alexandria Salt-glazed Stoneware,” p. 55. Milburn obtained at least some of his clay from Baltimore, according to an account in the Alexandria Gazette, January 10, 1855.

Pogue, “An Analysis of Wares,” p. 149.

Myers, “Alexandria Salt-Glazed Stoneware,” pp. 136–43. Myers provides a list of marks, along with the vessel form on which they were found.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), p. 40; and Jonathan Horne, A Catalogue of English Brown Stoneware from the 17th and 18th Centuries (London, 1985), p. 4.

Some late, undecorated Milburn pieces were deliberately fired to an even, light golden-brown color, but it is likely that all of the Swann-period stoneware was intended to have a gray salt glaze.

Alexandria Gazette, May 9, 1820.

Alexandria Gazette, August 6, 1819.

Howard F. Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1971), p. 85.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 41.

The pitcher is illustrated in Magid and Means, “In the Philadelphia Style,” fig. 51.

Myers, The Potter’s Art, p. v.

An entry in the card catalogue of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts indicates the pot was collected from a Greek revival house called Westview Farm, in Fauquier County, Virginia, where it sat in the front hall. A county surveyor named Henry Smith owned this home until his death in 1884, but no relation to the Alexandria Smiths is known.

Alexandria Deed Book K-2, p. 205, December 15, 1820. In various records, David Jarbour’s name appears as Tarbour and Jarbo.

Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, p. 53. Covered butter and cake pots are illustrated in an 1862 price list from O. L. & A. K. Ballard, in the collection of the Shelburne (Vt.) Museum.

Alexandria Gazette, May 9, 1820.

This unusual jug was consigned for auction by Crocker Farm in fall 2006.

Alexandria Gazette, October 15, 1829. Andrew Miller’s earthen furnaces were advertised in the Alexandria Gazette on August 14, 1824. Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), pp. 21–22; and idem, “Alexandria Salt-Glazed Stoneware,” p. 33.

Alexandria Gazette, September 19, 1840.