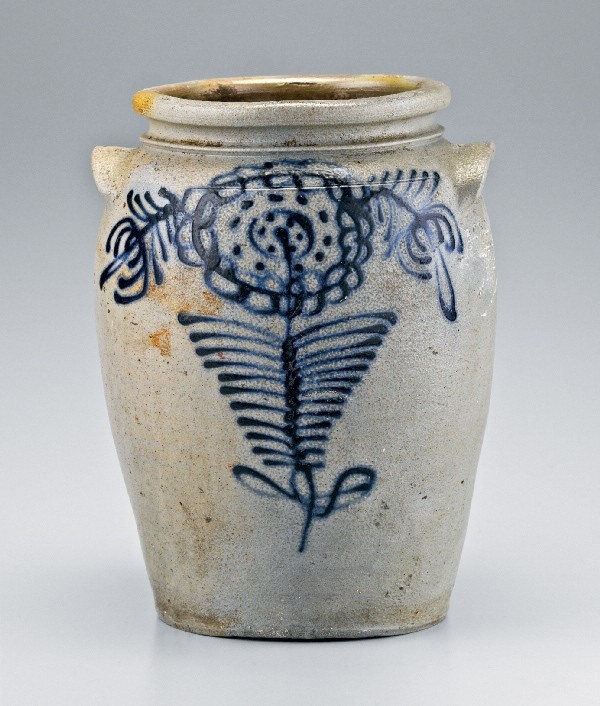

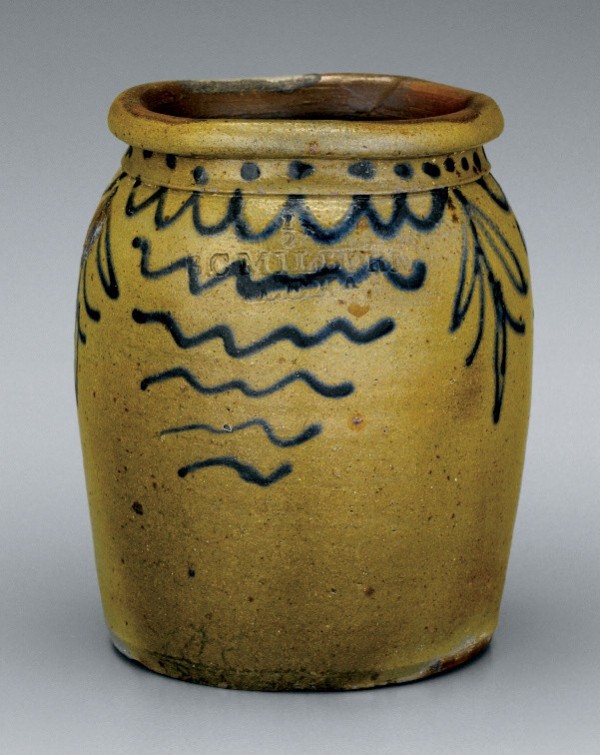

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 7 1/2". Capacity: Q÷@ gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini; photos by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted.) The central round flower is known as the Alexandria motif.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1851. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Encircling foliage is another common motif on Alexandria stoneware. Brushed-cobalt decoration was common until the Civil War. This piece was found in archaeological excavations on a residential property at 524 King Street.

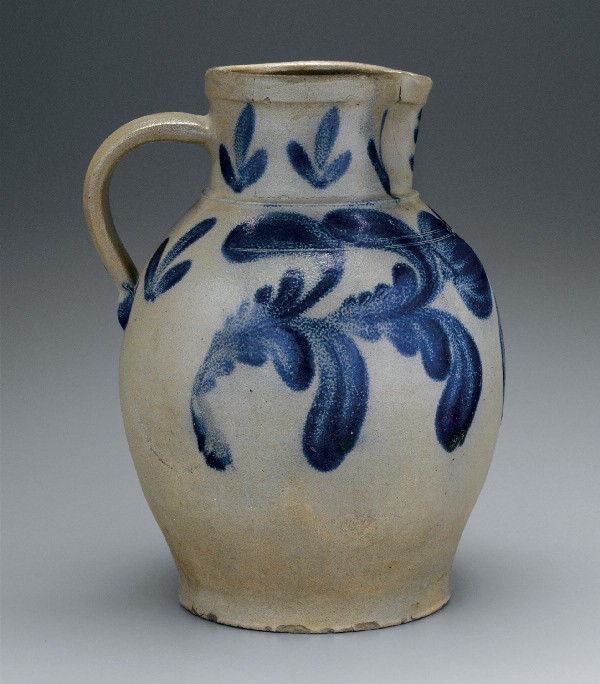

Pitcher, B.C. Milburn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 11". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Slip-trailed cobalt decoration is typical of the later Milburn period. The pitcher was found in a privy at 112 South Royal Street, in the midst of Alexandria’s commercial district.

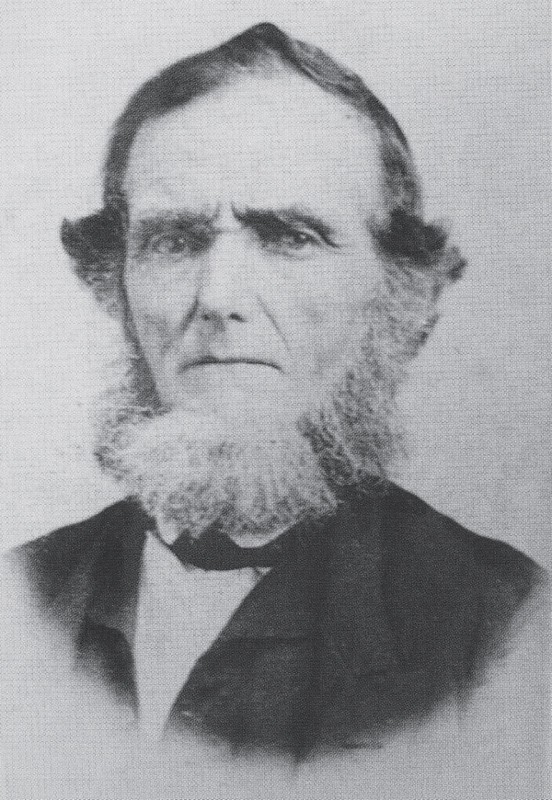

Benedict C. Milburn (1805–1867). (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.)

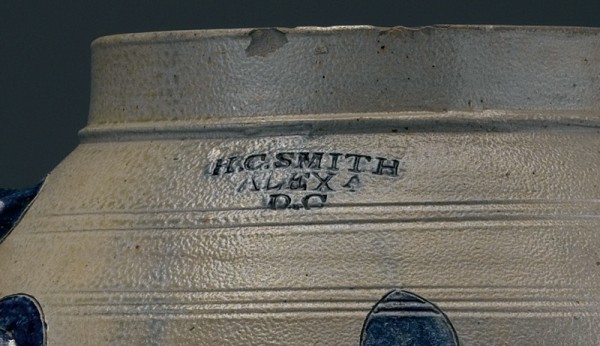

Detail of the “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” mark on the cooler illustrated in fig. 12. Although the stamp is found on many vessels of this period, this is the only known example in which it is highlighted with cobalt.

Detail of the cooler illustrated in fig. 68 showing capacity mark with “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” potter’s mark, 1847–1861. Whereas most capacity marks were made with impressed lead type, some 5- and 6-gallon capacity marks were drawn freehand on the leather-hard surface.

Detail of the cylindrical jar illustrated in fig. 27 showing capacity mark with “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” potter’s mark, 1847–1861. Some of Milburn’s 1- and 1 1/2-gallon capacity marks include a dashed circle, similar to marks used on some of the earliest Swann vessels.

Detail showing the potter’s mark of the cylindrical jar illustrated in fig. 19: “B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C.” This is the only mark in which the place name is executed in smaller, italic type. The city’s name is spelled out only on this mark and that made for Dubois & Reddick, illustrated in fig. 17.

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 51 showing the “S. C. MILBURN.” potter’s mark. This late mark is usually found on undecorated stoneware.

“W. LEWIS MILBURN.” potter’s mark, 1873–1876. D. of rim 7". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This is the only piece found at the Milburn kiln site with this mark.

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 11". Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.) Brushed cobalt is the most common form of decoration on Alexandria stoneware.

Cooler, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, incised decoration. H. 18 1/2". Inscribed: J. W. SMITH; impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.) This is the only known piece of Alexandria stoneware with incised and cobalt-filled decoration. This unusual cooler appears to have been made for a tavern, with images of bottles and jugs around its base. Leafy branches appear on the reverse and under each handle. 12The most likely owner of this piece was James W. Smith, listed in an 1834 business directory as proprietor of the Globe Tavern on Cameron Street, opposite the Market House.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 12 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) Slip trailing, a technique seen much earlier on Baltimore, New Jersey, and New York stoneware, was not introduced in Alexandria until sometime between 1847 and 1854.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1867. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". Impressed mark: B C MILBURN (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Plain, utilitarian wares were made throughout the history of the Wilkes Street Pottery, but predominated after the Civil War. This jar was found in a privy behind 307 South Saint Asaph Street, an elegant house that was occupied, as were many Alexandria homes, by Union troops during the war.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C. (Courtesy, Toby and Oscar Fitzgerald.) Encircling foliage is the most common decorative motif on early Milburn stoneware.

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 15 1/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Private collection.) The Alexandria motif, consisting of a central round flower on a stem of graduated leaves, was introduced about 1820 by earlier Wilkes Street potter John Swann.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 7 1/4". Impressed mark: DUBOIS & REDDICK / ALEXANDRIA D C (Private collection.) This jar, made at Milburn’s pottery for an Alexandria merchant, is the only documented example with this mark.

Jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. Left: H. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Right: H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Private collection.) A modification of the Alexandria motif introduced on early Milburn stoneware includes pairs of longer, straight leaves near the base of the leafy stems.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C. (Private collection.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 15". Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) The thick leafy stem, found with both of the H. C. Smith marks, appears to be the work of one decorator. The more crowded, encircling foliage seen here is only on jars from the early Milburn period.

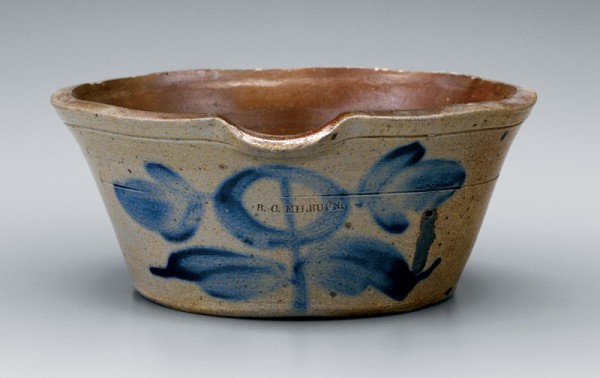

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. D. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) A design of pendant leafy fronds, sometimes called “swag and tassel,” first appeared with this mark. It is more common on the back of Alexandria stoneware, but on this piece, separate, shorter fronds appear on the reverse. The milk pan was discarded in a privy at 106 South Saint Asaph Street in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 14 1/4". Capacity: 5 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) Brushed and slip-trailed designs were used concurrently, and similar designs were executed with both techniques.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. Dimensions not provided. Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) Chains and pendant flowers encircle this jar. Similar designs were also executed in slip-trailed cobalt.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. D. 11 1/4". Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Chains and pendant flowers are more commonly seen on the back of vessels, as on this milk pan found in an excavation at 112 South Royal Street.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 14 1/2". Capacity: 4 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This elaborately decorated jar was found in excavations at Alfred and South Columbus streets, in a nineteenth-century free black neighborhood.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 10 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) This jar has a very primitive version of the central round flower. Large chain links with pendant branches appear on the reverse. The iron band is an old “make do” repair, probably from the nineteenth century.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) This mark was documented on nearly one hundred vessels, split evenly between those with brushed and slip-trailed designs. The Alexandria motif is the most common design on later Milburn stoneware.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. D. 9". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN. (Courtesy, Alan Darby.) Vessels with this mark have similar form and decoration as those stamped “B.C. MILBURN / ALEXA.”

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alan Darby.) Encircling foliage remains popular in the later Milburn period.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. D. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Encircling foliage is also common in slip-trailed designs. This milk pan was found in excavations on the 400 block of King Street, Alexandria’s main commercial district.

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 13 1/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) A sideways version of the round flower first appears in the later Milburn period, and is more commonly found on the back of vessels.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) The round flower is dotted to represent seeds.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 10 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) The sunflower was first depicted by Swann but was not used on early Milburn stoneware.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 12". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) This design includes a sunflower with seeds and petals, flanked by tulips.

Jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. Left: H. 10 3/4". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Right: H. 11". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) This flower, with petals within a circle, appears for the first time with this mark.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 12". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) The decorator combined two common elements in slip-trailed cobalt, the sunflower and the tulip.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. D. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.)

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 12 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) Tulips sprout from the edges of a large sunflower. The seeds are made up of a series of chain links.

Jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 8 1/4" and 7". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. [on both]. (Courtesy, Toby and Oscar Fitzgerald.) Tulips, first used by Swann, are more common in the later Milburn period.

Jar, attributed to B.C. Milburn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/4". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Unlike most of the decorated vessels from the Wilkes Street Pottery, this jar is not marked. The tulip was commonly used as the central flower on vessels with the “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” mark, and the primitive brushwork matches other vessels from this period. The jar was found in archaeological excavations on Alexandria’s Market Square.

Jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. Left: H. 10 1/4". Capacity: 1 gallon. Center: H. 11". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Right: H. 12 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) Milburn employed several decorators, who executed similar motifs in their own style.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 15 3/4". Capacity: 4 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) The tulip motif is also used with encircling foliage.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 10 1/2". Capacity: 1 1/2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, William and Jane Yeingst.) In the later Milburn period, pendant leafy fronds were usually combined with chains instead of plain swags. The reverse is decorated with two sideways tulip-like flowers.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. D. 12". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) The chains and pendant flowers continue on the reverse. This milk pan was found in excavations at 112 South Royal Street.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon: Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Al Marzorini.) Chains or wavy lines usually appear on the reverse of Milburn’s vessels, but they decorate both sides of this jar.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 7 1/2". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) A similar pattern of dots and wavy lines appears on the reverse of this jar, with the front and back separated by pendant fronds.

Jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) The graduated foliage at the shoulder is similar to that used by Shenandoah Valley potters.

Jar, attributed to B.C. Milburn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) The representative subject matter is unusual, but the clay, the shape of the vessel, and the use of slip trailing are similar to other Milburn pieces. This jar was found in excavations in Alexandria, at the site of a nineteenth-century restaurant and residence on the 400 block of King Street.

Milk pan, Alexandria, Virginia, 1867–1873. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". Impressed mark: S.C.MILBURN. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Despite the crack, this badly warped “second” was used at a residence at 307 South Saint Asaph Street.

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1867–1873. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 15 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: S.C.MILBURN. (Private collection.) This is a rare example of a decorated S. C. Milburn vessel.

Jars and bowl, Alexandria, Virginia. Salt-glazed stoneware. Jar, back left, 1865–1876. H. 13 1/4". Impressed mark: E.J.MILLER / ALEXA.. Jar, back right, 1847–1867. H. 9 1/2". Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.. (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Bowl, front, 1865–1876. D. 10". Impressed mark: E.J.MILLER / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.) E. J. Miller took over his father’s china shop in 1865, and jars with his mark are identical to ones with the marks of B.C. and S.C. Milburn. Five sherds marked E. J. Miller were found at the Milburn kiln site.

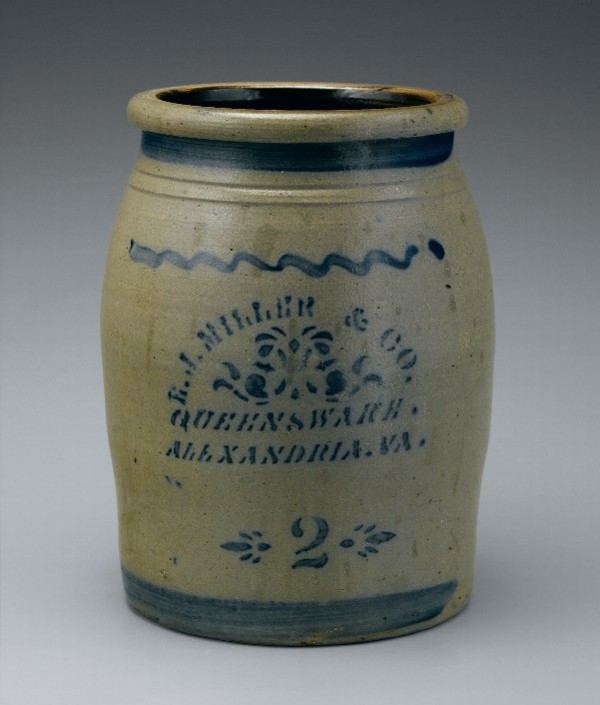

Jar, James Hamilton, Greensboro, Pennsylvania, after ca. 1876. Salt-glazed stoneware with Albany-slip interior, brushed and stenciled cobalt. H. 11 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Stenciling: E.J.MILLER & CO. / QUEENSWARE. / ALEXADNRIA.VA. (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Stenciled advertising is not found on stoneware manufactured in Alexandria. After the Alexandria Pottery closed, E. J. Miller & Co. purchased stoneware from this large Pennsylvania manufactory.

Lug handle. L. 4". Detail of 1819–1821 jar bearing “J.SWANN / ALEXA.” mark. A simple, straight handle with cut ends was first used by John Swann and continued to be used on jars, churns, cake pots, and milk pans throughout the history of the Wilkes Street Pottery.

Extruded lug handle. L. 5". Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 20. Extruded handles, in which clay was forced through a template, first appeared on Alexandria jars between 1831 and 1847; they became common on American stoneware in the mid-nineteenth century.

Strap handle. L. 5 1/2". Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 11. Vertical strap handles were used on pitchers, chamber pots, and coolers of all periods.

Extruded horizontal open-loop handle. L. 7". Detail of the cooler illustrated in fig. 12.

Lid, Alexandria, Virginia, 1825–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) Some lids are flat on the underside, but others, like this lid from excavations at 524 King Street, have a shallow flange one inch from the edge.

Flared rim. Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 73. Flared rims accommodated flat stoneware or wooden lids.

Flat rim. Detail of the butter pot illustrated in fig. 64. Flat rims supported a flanged lid, as shown in fig. 58.

Flared rim. Detail of the churn illustrated in fig. 66. Tall, flared churn rims allow a flat wooden or stoneware disk with a hole for the dasher to sit down inside the rim.

Round rim. Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 2. The round rim was used on jars throughout the history of the pottery.

Collared rim. (Detail; jar not illustrated.) (Courtesy, William and Jane Yeingst.) A collar below the rim was first used with the stamp “H. C. SMITH / ALEXA. / D. C” between 1831 and 1847.

Butter pot, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alan Darby.) Milburn’s 1859 trade card lists “butter jars” as covered wares. These would have had flat lids like that shown in fig. 58.

Chamber pot fragment, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. D. 7". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This fragment, found in excavations on the 200 block of North Union Street, is attributed to Milburn based on the familiar slip-trailed design.

Churn, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 12". Capacity: 2 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.)

Cooler, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 14". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, John and Lil Palmer.) The design and shape of this cooler are similar to pitchers of this period, but with two handles and a bunghole at the base instead of a pouring spout at the rim. On the reverse is a large chain on the neck and five-leaf clusters on the shoulder.

Cooler, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 17". Capacity: 5 gallons. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Private collection.) The round flower buds are unusual in Alexandria but similar to ones on jugs attributed to Emanuel Suter (ca. 1866–1880), a later Rockingham County, Virginia, potter.

Flowerpot, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1867. H. 7 1/4". Salt-glazed stoneware. Stamped near base: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.)

Master ink bottle, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1867. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alan Darby.)

Ovoid jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. Left: H. 9". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Right: H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.)

Straight-sided jars, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. Left: H. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.). Right: H. 8". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.) Jars with rounded rims are not quite true cylinders, with sloping shoulders and a narrower rim. This form was first made by John Swann.

Lidded jar with flared rim, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Alan Darby.)

Small-mouthed jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 9". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Private collection.) The shape of this jar, with a sharply angled shoulder and narrow mouth with rounded rim, is similar to that of earthenware jars made in Alexandria and Philadelphia in the late eighteenth century.

Cylindrical jar, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1851. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. (Private collection.) It is likely that an 1859 Milburn trade card listing “stone fruit jars filled with cork and cement” referred to jars of this shape. The jar was probably sealed with a small stoneware lid; a cone-shaped section protrudes down through a cork ring.

Jugs, Alexandria, Virginia. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left, 1847–1867. H. 12 1/4". Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Center, 1873–1876. H. 6 1/2". Impressed mark: W. LEWIS MILBURN. (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.) Right, 1867–1873. H. 8 3/4". Impressed mark: S.C.MILBURN. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.)

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 14 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. Impressed mark: H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C (Courtesy, William and Jane Yeingst.)

Pitcher, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. H. 10 1/4". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum.) The cylindrical shape of this pitcher is unusual in Alexandria, but was used in the Shenandoah Valley in the late nineteenth century.

Spittoon, Alexandria, Virginia, 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. D. 7". Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B C MILBURN (Private collection.)

Spittoon, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1867. D. 7". Salt-glazed stoneware. Capacity: 1/2 gallon. Impressed mark: B.C. MILBURN. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.) This spittoon was found in a privy at 524 King Street.

Stoneware from Alexandria, Virginia, is indeed of excellent quality, as Alexandria merchant Robert H. Miller advertised in 1841.[1] Alexandria’s best-known and longest-operating stoneware manufactory was located on the 600 block of Wilkes Street circa 1810–1876. While the business was referred to in some contemporary advertisements as the Alexandria Pottery or the Milburn Pottery, it is now commonly known as the Wilkes Street Pottery.[2]

In Part I of this study, published in the 2012 volume of Ceramics in America, I reviewed the period in which Milburn’s predecessor, John Swann, worked at Wilkes Street, circa 1810–1831.[3] In Part II, I focus on the period in which Benedict C. Milburn and his sons operated the manufactory, circa 1831–1876. I have examined approximately 150 Alexandria stoneware vessels of this period in museums and private collections, as well as extensive archaeological materials.

The earliest Milburn stoneware was stamped “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” for the china merchant from whom he rented the pottery. After Milburn purchased the pottery in 1841, just three months before Miller’s advertisement for his stoneware appeared in the Alexandria Gazette, much of his stoneware was stamped with his own name.[4] During the earlier Swann period, stoneware was stamped “J. SWANN / ALEXA.”, “HUGH SMITH & CO.”, and “H.SMITH & CO.”

Many of Milburn’s stoneware vessels still survive, decorated with elaborate brushed-cobalt or slip-trailed decoration (fig. 1). According to Mary Powell’s 1928 history of Alexandria,

Here all kinds of vessels were made of gray stoneware ornamented with blue leaves and flowers,—jugs, milk crocks, jars, pitchers and even little money jugs for children. Many are still owned and treasured by old families of the town. That kind of ware apparently is not now manufactured in this country, but a returned soldier from the great World War in France said it was frequently seen there, and made him feel almost homesick when he recalled the old potteries of his childhood at Alexandria.[5]

Some Alexandria stoneware is still owned by families in Alexandria and surrounding counties whose ancestors bought and used it in the nineteenth century. One family owned a house on Prince Street from 1817 until 2000, and pieces of Milburn’s stoneware remained in the outbuildings. Alexandria stoneware is now highly sought after by collectors and can also be found in a number of museums, including the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; the DAR Museum; the Brooklyn Museum; and The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum.

Vessels marked “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” (fig. 2), made circa 1847–1851, are common among Alexandria stoneware, although the most commonly collected bears the mark “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” and was made circa 1847 to 1867 (fig. 3). Other Milburn marks are seen less often, and rare pieces include those made at Wilkes Street with the marks of Alexandria merchants Dubois & Reddick and James P. Smith. While most of the extant pieces of Alexandria stoneware were made at Wilkes Street, a few marked examples made at the potteries of James Black, Tildon Easton, and James Miller also survive.[6]

Much of our knowledge of Alexandria stoneware comes from archaeological work conducted in the city over the past forty years. In 1977 a brief rescue excavation at the Wilkes Street Pottery yielded about 14,500 stoneware sherds, 1,500 of which had cobalt decoration. Fifteen stamped sherds from the Milburn period were among the finds.[7] Milburn’s stoneware was so widely used that it has been recognized at all of the Alexandria archaeological sites relating to his time period, and the distinctive slip-trailed decoration he employed has also been noted at archaeological sites in Fairfax County, Virginia, in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere in the region (see fig. 3).

B.C. MILBURN AND THE WILKES STREET POTTERY

Benedict Cuthbert Milburn came to Alexandria from St. Mary’s County, Maryland, in 1822 (fig. 4). During his first years in Alexandria, he may have worked with earlier Wilkes Street potter John Swann. The Swann and Milburn families both came from St. Mary’s County and had close ties there. By 1833 Milburn was running the stoneware manufactory, and purchased it from china merchant Hugh Charles Smith in 1841. After Milburn’s death in 1867, his sons continued to operate the pottery until 1876.

According to family records, the seventeen-year-old Milburn came to Alexandria to apprentice himself with a potter.[8] Milburn probably apprenticed at Wilkes Street with John Swann, but in 1822 there was at least one other pottery in town: Evans and Griggs, successors to Lewis Plum at Wolfe and South Columbus streets. Milburn could also have worked with potter James Black before Black’s first pottery failed in 1832.[9] According to the Alexandria Gazette, Milburn and Black were partners in a grocery business in 1828, close to the time Milburn would have finished an apprenticeship. Milburn purchased Black’s interest in the grocery in June of that year.[10] We do not know if he worked as a potter and grocer at the same time, nor do we know if his grocery business developed into the “family grocery store” advertised in 1865 by one of his sons, J. Clinton Milburn.[11]

Milburn was probably working for H.C. Smith at Wilkes Street at least by 1831, when he rented Swann’s old house. He was certainly there by 1833 when his name first appeared on tax rolls for the pottery. In an 1869 advertisement by his son, “Milburn’s Pottery” is said to be “Established 1833.”[12] B.C. Milburn was most likely managing the pottery from that date, either as an employee of H.C. Smith or renting the premises from him.

In 1839 the editor of the Alexandria Gazette wrote:

As soon as our Canal is completed we shall be abundantly supplied with water for manufacturing purposes; nor, in truth, do we see the reason, why this should not become, at once, a MANUFACTURIING TOWN, having the means already of a flourishing commerce to rid us in the transportation of goods, and Ship Yards where the finest merchant vessels are yearly turned off the stocks. . . . Let us, then, by all means, commence early with our MANUFACTORIES.[13]

It was in this hopeful economic climate that Milburn purchased the pottery in 1841. He appears to have been an immediate success, with his beautifully formed and decorated stoneware.

Milburn faced only brief competition from other Alexandria potters. Milburn’s one-time partner in the grocery business, James Black, worked at Wilkes Street under Milburn in 1834. Before then, Black operated his own stoneware manufactory in Alexandria, which ended in failure. He was confined briefly in a debtors’ prison before declaring bankruptcy in 1832 and, according to the Alexandria Gazette, endured a court-ordered sale of “burned ware, clay, wheelbarrow etc.”[14] In 1836 Black was again working on his own as a potter, at the northwest corner of Wolfe and Patrick streets. This site has not been excavated, but a few extant pots are known, with the stamps “J. A. BLACK / ALEXA. / D. C.” and “J. A. BLACK / ALEX”.

Tildon Easton opened a manufactory on the 1400 block of King Street in 1841, the same year that Milburn purchased the Wilkes Street Pottery. Only one extant piece is known—marked “TILDON EASTON”—but fragments of more than 650 vessels were found in the archaeological excavation of his kiln site. Easton produced salt-glazed stoneware and earthenware for a short period of time, before declaring bankruptcy in 1843.[15] Perhaps Black and Easton were unable to compete with the well-established Wilkes Street Pottery, which had been operating since 1810.

Additional competition known from the 1840 Census of Manufactures included two potteries in neighboring Washington, D.C., and nine in nearby Baltimore. No stoneware sherds with Washington or Baltimore marks have been found on Alexandria’s archaeological sites, though unmarked pieces would be difficult to distinguish from Alexandria wares. A few early-nineteenth-century unmarked vessels from Baltimore have been identified in the archaeological record. Many potters worked in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in the second half of the nineteenth century, and some of their wares were used in Alexandria and are recognized on archaeological sites in the city.

A few of Milburn’s employees are known from tax records. The tax assessor recorded names of workers who were employed on the day of his yearly visits, but others were most likely employed at other times. B.C. Milburn himself was first listed in 1833. Michael Morris was first listed in 1828 and in 1833 was listed alongside Milburn. Kitty Marshall, the first known female employee, was listed in 1832 and again in 1842. Two additional women worked with Milburn, perhaps as decorators: Milly Jackson (1834–1838) and Sylvia Rogers (1834–1847). John Simms was listed on the tax rolls for 1839, and Alfred Merrick in 1840 and 1841. After Milburn purchased the pottery in 1841, a few additional names appear: Chas. Richardson (1842), Wm. Nickens (listed as Colored, 1842–1848), Milburn’s twelve-year-old son, Stephen (1845), Thos. Grant (1849), Dennis Hasket (also listed as Colored, 1847 and 1850), and John Payne and James Shemick (both in 1850).[16]

Milburn’s business continued to expand during the late 1840s and 1850s. The Alexandria Canal opened at the end of 1843, connecting the Alexandria waterfront with Georgetown and the C&O Canal, which by 1850 reached all the way to Cumberland, Maryland. The canal opened trade to the west, enabling better transport of both raw materials and manufactured goods. The period following Alexandria’s retrocession to Virginia in 1847 brought economic growth. The city fought long and hard for retrocession, as the town’s tenure as a part of the federal district had stifled economic growth. In particular, banking restrictions imposed by Congress on the District of Columbia had affected the town’s economy. Following retrocession, the town ranked ninth in the U.S. in overall trade, following New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Richmond, Petersburg, and Cleveland.[17] Milburn and Hugh Smith were among those Alexandrians who voted for retrocession, and presumably they were happy to discontinue the use of “D.C.” in their pottery marks.

Baltimore’s early adoption of railroads helped that city eclipse Alexandria as a center of manufacturing and trade. In 1847 Baltimore potter Edwin Bennett built a more industrialized pottery, producing yellow wares and Rockingham wares using molds and jigger/jolly machines in place of the potter’s wheel. These wares are common on Alexandria’s archaeological sites, along with Milburn’s stoneware.

During the 1840s and early 1850s, Milburn continued to make stoneware with the stamp of his former employer, H. C. Smith. Hugh Charles Smith was the senior partner in his family’s retail business until his death in 1850, and the partnership was dissolved the next year.[18] His brother James P. Smith then ran the retail shop, and the Milburn Pottery made stoneware stamped with his name until September 1854, when the business was sold out of the Smith family.[19]

Stoneware with the impressed marks of another Alexandria merchant, Dubois and Reddick, was also made at Wilkes Street sometime between 1841 and 1847. After the Civil War, Milburn and his sons made undecorated stoneware with the mark of prominent china merchant Elisha Janney (E. J.) Miller, with vessel forms identical to those with the Milburn’s own stamps. From the early 1820s Robert H. Miller had been a prominent china merchant and a rival to Hugh Smith, with a store on the 200 block of King Street. Although Robert H. Miller and his son Elisha Janney Miller both advertised Alexandria stoneware,[20] the ware was not stamped with the company name until after Elisha took over the business in 1865, upon his father’s death. The marked pieces may date from E. J. Miller’s advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette in 1869: “Alexandria Pottery being again in full operation, I am prepared to furnish my customers and the public generally with stoneware of all kinds and of first quality.”[21] After the Wilkes Street Pottery closed, E. J. Miller imported stenciled stoneware made by James Hamilton in Greensboro, Pennsylvania.

Milburn also supplied stoneware without merchant’s marks to druggist William Stabler. An invoice in the collection of the Stabler-Leadbeater Apothecary Museum, dated July 10, 1848, shows a sale from Milburn to Stabler of 100 two-inch pots and 100 three-inch pots, possibly for Stabler’s wholesale seed business.

Milburn’s first advertisement, for flowerpots, appeared in the Alexandria Gazette on September 1, 1845:

ALEXANDRIA POTTERY

Those who have never witnessed the operations of shaping and finishing Earthenware will be gratified by a visit to the manufactory of Mr. Milburn, on Wilkes Street, of this city. The material employed is a species of bluish white clay, found in various parts of the country, and composed of such proportions of alumina and other ingredients as to make it very tenacious and plastic when moistened. The clay used at Mr. Milburn’s factory is brought from the vicinity of Baltimore City. After the clay is thoroughly kneaded and prepared, a certain portion, according to the size of the vessel to be made, is placed upon a circular board fixed horizontally and connected with a treadle by which a rotary motion is given to it. While the clay is revolving in common with the board on which it lies, the operator shapes it with his hands, into whatever vessel it is designed to make.

The judgment shown in choosing just the proper quantity for the vessel designed, and the skill and regularity with which it is brought to the shape and size desired, by the aid of machinery so simple, excite the admiration of the beholder. The vessels thus prepared are dried a while in the sun; after which they are placed in the kiln where the process of burning and glazing complete the work.[22]

In 1855 there was enough interest in the Wilkes Street Pottery that a reporter for the Alexandria Gazette toured the premises and offered a description of the process of making stoneware. The author mentions turning, drying, and firing, but not decorating, although this practice most likely continued until the Civil War. The most surprising statement from this article is that Milburn used clay brought in from the Baltimore area. At least some Alexandria stoneware is chemically consistent with clay samples taken locally, within a few blocks of the kiln site. In 1851 a rail line opened in Alexandria that ran right past Milburn’s Pottery, and this may have made it cost-effective to import clay. Baltimore clays were also exported to industrial potteries in New Jersey and Ohio into the early twentieth century.[23]

Business remained strong throughout the 1850s, but like all Alexandria businesses, the Wilkes Street Pottery was severely affected by the Civil War. The day after the first shots were fired, federal troops occupied Alexandria. The town housed a major supply depot and other support services. Anthony Trollope wrote:

We landed also on this occasion at Alexandria, and saw as melancholy and miserable a town as the mind of man can conceive. . . . All trade was at an end. In no town at that time was trade very flourishing; but here it was killed altogether—except that absolutely necessary trade of bread.[24]

The pottery may have closed during the war, as did many of Alexandria’s businesses. If Milburn did supply stoneware to the U. S. military, it would have been under duress. Three of Milburn’s sons enlisted in the Confederate Army. A 1912 obituary for his son James Clinton Milburn refers to his father, “who previous to the Civil War conducted a pottery on the north side of Wilkes Street.”[25] The pottery was in full operation once again by November 1866, when the Alexandria Gazette reported:

The old established Pottery of Mr. Milburn, in this place, is, we are glad to see, in successful operation, turning out the best ware from the best materials. This establishment has obtained a well-merited reputation for earthenware, which it keeps up to this day.[26]

Following Milburn’s death in 1867, a notice in the Alexandria Gazette referred to the success and prominence of the pottery:

THE POTTERY of the late Mr. Milburn, which he carried on, with so much credit to himself, for many years, will be continued under the control of his son. This is another of the old and successful manufacturing establishments of this place. Its wares are well known throughout the country, and considered the very best of their kind.[27]

MILBURN’S SONS

At least three of Milburn’s seven sons were trained as potters, and two of them managed the pottery in its later years.[28] Stephen Calvert Milburn, who first worked at the pottery in 1845 at the age of twelve, already had a major role there before his father’s death in 1867. His name appears beneath his father’s in the 1860 Census; both men are listed as potters.[29] Stephen advertised in the local paper in 1869, stating that he was the successor to B.C. Milburn and was continuing the manufacture of stoneware and of earthenware flower and chimney pots.[30] The 1870 Census shows S.C. Milburn as having four male employees, one clay mill, three lathes (potter’s wheels), and one kiln.

Although Stephen’s brothers John and W. Lewis both trained in their father’s business, they were both listed as apothecaries in the 1860 Census and W. Lewis Milburn was listed in an 1870 city directory as “druggist.”[31] An 1873 city directory lists W. Lewis Milburn as proprietor of the pottery,[32] and Stephen had moved away from Alexandria by 1875.

Court records from 1874 provide some insight into the pottery’s financial difficulties in its last years. Henry D. Wolff, a journeyman potter, filed a mechanic’s lien against W. Lewis Milburn for twenty-three days’ work. The lien was for $46 in back wages, with $16.30 deducted for three weeks’ board, cracked pots, and cash. The lien lists an inventory of 904 stoneware vessels: 356 jugs, 169 pots, 336 pans, and 43 churns.[33] The sizes produced are also enumerated, with one-half, one-, and two-gallon jugs; three- to six-gallon pots; one- to three-gallon pans; and three- and four-gallon churns.

The pottery closed sometime before April 1876, at which time the land was sold to the Smoot tannery across Wilkes Street and a bark shed was constructed on the site.

MAKERS’ AND MERCHANTS’ MARKS

At least ten distinct marks were used during the Milburn period. Milburn and his sons made stoneware with their own marks at the same time they were producing stoneware with the stamps of Alexandria merchants. Dates attributed to each mark are based on historical records, the 1847 date of Alexandria’s retrocession to Virginia, and formal characteristics of the stoneware.

Marks were impressed into the clay vessel using a stamp consisting of lead type, probably set into a wood frame. The lettering ranges from 14- to 28-point type. In one example, a large cooler made for J. W. Smith, the lettering was highlighted with cobalt (figs. 5, 12).

Capacity marks were usually made with impressed lead type in larger type than the maker’s mark. On some of the five- and six-gallon vessels, however, marks were incised into the leather-hard surface (fig. 6). Some 1- and 1 1/2-gallon capacity marks on “B.C. MILBURN” and “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” vessels were stamped within a dashed circle, similar to marks on some of the earliest Swann vessels (fig. 7).

The marked Milburn stoneware can be divided into three periods. The first (1841–1847) begins with Milburn’s purchase of the pottery, and includes the time in which Alexandria is part of the District of Columbia. The second period (1847–1861) begins when Alexandria was retroceded to Virginia, and includes stoneware decorated with slip-trailed cobalt. Most of the stoneware produced by Milburn’s sons after the Civil War, in the third period (1865–1876), is undecorated.

EARLY B.C. MILBURN MARKS

H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D. C 28 pt. ca. 1831–1847

B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C. 12 pt. / 8 pt. ca. 1841–1847

DUBOIS & REDDICK / ALEXANDRIA D C 18 pt. ca. 1841–1847

H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. 26 pt. ca. 1847–1851

Four marks were stamped on Milburn pottery prior to his use of slip-decorated cobalt decoration. Three of these marks were used during the period when Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia, prior to the city’s retrocession to Virginia in 1847.

The mark “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” came into use sometime between 1831, when Hugh Smith dissolved an earlier partnership and left his son Hugh Charles Smith to manage the company, and 1833, when Milburn leased the pottery. After Milburn became owner of the pottery in 1841, vessels with B.C. Milburn and H.C. Smith marks were probably made concurrently. The “B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D.C.” mark is unusual in that the place name is executed in smaller italic type (fig. 8).

While the history of Alexandria merchant Dubois & Reddick is not known, the mark probably dates to the same era as the Milburn mark in which the city name is also spelled out. The only documented jar with the Dubois & Reddick mark is similar in appearance to others from the Wilkes Street Pottery dating from 1825 to 1847 (see fig. 17).

The “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA.” mark was used after Alexandria’s 1847 retrocession until 1850, when Hugh Charles Smith passed away, or perhaps 1851, when company ownership passed to his brother James P. Smith.

LATER B.C. MILBURN MARKS

J.P.SMITH 26 pt. ca. 1851–1854

B. C. MILBURN. 16 pt. ca. 1847–1867

B C MILBURN 14 pt. ca. 1847–1867

B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA. 26 pt. ca. 1847–1867

B.C. Milburn and J. P. Smith marks have been found on vessels with slip-trailed cobalt and with brushed-cobalt decoration.

The mark “J.P.SMITH” was used for a few short years, from July 1851 to September 1854. During this period, the company was owned by James P. Smith, Hugh Smith’s son and former partner.

Most of Milburn’s vessels of the post-retrocession period are stamped “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.”, but the mark was probably used concurrently, for at least a part of this period, with the marks “B.C. MILBURN.” and “B C MILBURN”. The “B.C. MILBURN.” mark includes a period after the name, as do the marks of Milburn’s sons, but it is executed in 16-point type, whereas the unpunctuated mark is stamped with 14-point type, like that of Milburn’s sons. These marks were documented on both decorated and plain vessels, and were most likely in use before the Civil War.

MARKS USED BY MILBURN’S SONS

S.C.MILBURN. 14 pt. ca. 1867–1873

W. LEWIS MILBURN. 14 pt. ca. 1873–1876

E.J.MILLER / ALEXA. 24 pt. ca. 1865–1876

Stephen C. Milburn took over the business after B.C. Milburn’s death in 1867, and by 1873 his brother W. Lewis Milburn had succeeded him. The S.C. Milburn mark is found on a few vessels with brushed-cobalt decoration, but both marks appear mostly on plain, undecorated wares (figs. 9, 10). On one plain, two-gallon storage jar the small stamped mark “S.C.MILBURN.” appears above his father’s larger “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” stamp. The “S.C.MILBURN.” stamp was also used together with that of china merchant E. J. Miller and with the stamped initials “SDS”—possibly the mark of another local merchant. Stoneware stamped with Miller’s name is dated after 1865, when he took over his father’s King Street store.

TECHNIQUES OF DECORATION

Most pieces of early Milburn stoneware made between circa 1831 and 1851 were decorated with brushed cobalt. Somewhat surprising, only one piece with incised decoration is known. Slip-trailed decoration was added to the pottery’s repertoire sometime between 1847 and 1854. After the Civil War, the pottery made mostly undecorated wares.

Brushed Cobalt. Brushed cobalt is the most common form of decoration on American stoneware, widely used after the late 1780s when cobalt pigment was commercially produced in this country. Milburn’s predecessor, John Swann, first used brushed-cobalt decoration around 1819. By the early 1830s, this method of decoration had already reached its mature form in Alexandria, with exuberant flowers and foliage covering a large portion of the pot (fig. 11). Milburn continued to use Swann’s earlier motifs, including forward-facing designs with a round flower (known as the Alexandria motif), and foliage encircling the vessel, often combined with tulips. Brushed-cobalt decoration was common on Alexandria stoneware until the Civil War.

Incised Decoration. On one cooler stamped “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” the potter incised the outline of the letters and decorative elements and then filled the designs with cobalt (fig. 12). This technique was used on early-nineteenth-century American stoneware from Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York. Incised decoration is not known on other Alexandria stoneware, but the maker might have been influenced by stoneware from the Baltimore pottery of Morgan and Amoss (1812–1822)[34] or by Richmond, Virginia, potter John Poole Schermerhorn. Schermerhorn was originally from New York State, where this technique is more common, and he might have introduced the filled incised decoration at Richmond’s DuVal Pottery circa 1813. The technique continued to be used in Richmond as late as 1856.[35] The Alexandria cooler’s extruded, horizontal, open-loop handles and straight neck are also reminiscent of New York stoneware from the early nineteenth century.[36] While Benedict C. Milburn and some of the other known employees of the Wilkes Street Pottery came to Alexandria from St. Mary’s County, Maryland, perhaps one of the potters had worked with Schermerhorn or another potter in the New York area—or Milburn might have been influenced directly by examples of their wares or by German stoneware, which is found on early Alexandria sites.

Slip-Trailed Cobalt. Slip trailing was done concurrently with brushed decoration, but the two techniques are not found together on the same vessel. Instead of using a brush, the potter blew through a slip-cup, dripping a thin line of blue cobalt from a quill onto the surface of the vessel (fig. 13). This produced a finer line, but similar motifs and arrangements of decorative elements were used with both brushed and slip-trailed cobalt. Both techniques are found with the marks “B. C. MILBURN.” and “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” (both dated circa 1847–1867), and “J.P.SMITH” (1851–1854), indicating a date between 1847 and 1854 for the introduction of slip trailing.

This technique was used by Baltimore potters James Burland, William H. Morgan, Morgan and Amoss, and David Parr in the early 1820s, but their designs are less elaborate than Milburn’s work. Their small dabbed leaves are reminiscent of Swann’s brushwork of that period.[37] There is also one known example of slip-trailed cobalt decoration on a jar with a simple floral design, made circa 1824–1826 by another Alexandria potter, James Miller.[38]

Undecorated Stoneware. Plain, utilitarian wares, such as jugs and flowerpots, were made prior to the Civil War alongside decorative wares. In the period following the war until 1876, when the Wilkes Street Pottery closed, Milburn and his sons mostly made undecorated utilitarian wares (fig. 14).

DECORATION ON EARLY MILBURN STONEWARE

The “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” mark is the most common from this period, documented on thirty vessels, followed by “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA.” on eight vessels. The “B.C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D.C.” mark was documented on only five vessels, as most stoneware of this period was probably marked with the Smith Company name. Only one “DUBOIS & REDDICK / ALEXANDRIA D C” pot is known. Vessels with all of these marks bear similar decorative motifs.

Encircling foliage (fig. 15) is the most frequent decoration in this period, followed by the so-called Alexandria motif, consisting of a central round flower on a stem with graduated leaves (fig. 16). Some vessels of this period closely resemble those made by Swann before 1831. For instance, the execution of the Alexandria motif on the Dubois & Reddick jar (fig. 17) is similar to that on Swann-period vessels marked “H.SMITH & CO.” (1825–1831) and on Milburn-period vessels marked “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C”.

In some vessels of this period, longer straight leaves appear near the base of the leafy stem. The decorators used from one to three pairs of leaves (figs. 18, 19). The same design is found with later marks, executed in brushed and slip-trailed cobalt.

In another variation, the encircling foliage is much more crowded than on earlier and later jars. Yet another variation, likely the work of one particular decorator, is a thick stem, seen on a few jars with each of the H. C. Smith marks (fig. 20).

A new design of pendant leafy fronds, sometimes called “swag and tassel,” was first used on stoneware with the “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” mark, and continued to be used in the later Milburn period. The fronds are used as the main design on pitchers and a milk pan (fig. 21), but are more commonly found on the back of Alexandria stoneware vessels.

DECORATION ON LATER MILBURN STONEWARE

The later period of B.C. Milburn’s stoneware is marked by the introduction of the technique of slip-trailed decoration. Slip trailing is found only with specific marks—“B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.”; “B.C. MILBURN.”; and “J.P.SMITH”—and so was used from circa 1847/54 until about 1861, the start of the Civil War. Slip trailing was used concurrently with brushed-cobalt decoration, and similar patterns were executed with both techniques (figs. 22-25). Decorators may have specialized, but it is possible that some workers were proficient in both techniques. Although slip-trailed stoneware was made in Alexandria for only about ten years, extant examples are fairly common because by the 1850s Milburn had increased production at the pottery.

While many vessels marked “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” have beautifully executed and elaborate artwork (fig. 26), others have designs executed in a surprisingly primitive style (fig. 27). The Smith Company merchant marks are not found on the more primitive artwork, which might indicate that it was produced after the company closed, in 1854.

In this period, the central round flower or Alexandria motif was the most common design (figs. 28, 29), followed by encircling foliage (figs. 30, 31). Foliage branching from a central stem was also common, and pendant fronds or foliate sprigs continued to be used.

Several new design elements were used in this period, in both brushed and slip-trailed cobalt. While the forward-facing flower continued to be common, flowers appeared sideways on the backs of vessels or in a variant of the encircling foliage motif (fig. 32). Milburn used a variety of flowers in addition to the simple round flower introduced by Swann. The round flower was sometimes embellished with seeds (fig. 33). The sunflower was common in this period (figs. 34, 35).

Although sunflowers were depicted on Swann’s pottery, they were not documented in the early Milburn period. A new flower, with petals inside an open circle, may be a depiction of a cabbage rose or simply the artist’s fancy (fig. 36). In odd juxtapositions, the round flower with petals encircles a tulip-like flower on a slip-trailed jar and milk pan (figs. 37, 38), and tulips sprout from the edges of a large sunflower on a jar (fig. 39). Tulips, first used by Swann, become more common in this period and are used in forward-facing designs (figs. 40-42) and also in ones that encircle the pot (fig. 43). Encircling foliage continues to be popular in this period and is similar to that seen on earlier Alexandria pots.

Pendant leafy fronds (or swags and tassels) were first documented in the early Milburn period. In the later period, pendant fronds or tulips are usually combined with chains instead of plain swags (figs. 44, 45). New designs of chains and scalloped or wavy lines also commonly appear on the reverse of vessels but sometimes surround the rim (figs. 46, 47).

Some vessels of this period resemble Shenandoah Valley stoneware, with graduated foliage at the rim (fig. 48). Often, the graduated foliage is combined with pendant tulips. The exchange of ideas between potters from Alexandria and the Shenandoah Valley may have gone in both directions. The decoration on a salt-glazed stoneware pitcher produced circa 1866–1867 and marked “IRELAND / & / DUEY. / MT. CRAWFORD / VA.” bears a striking resemblance to the work of the Milburn pottery made between 1847 and 1861, with chains, pendant flowers, and graduated leaves.[39]

The marked Alexandria stoneware vessels show no representational motifs apart from flowers and foliage. However, a wonderful jar depicting a sailing ship and tree has long been attributed to Milburn (fig. 49). This intriguing find is from archaeological excavations undertaken on Alexandria’s King Street in the early 1970s, at the site of a nineteenth-century restaurant. As with most unmarked pieces, we cannot make a definite attribution, but this jar does bear a significant resemblance to other Milburn pieces. The clay is similar in appearance to Alexandria stoneware, and the shape of the straight-sided jar and its square rim with collar are typical of jars of the Milburn period. The ship and the tree are both common nineteenth-century motifs.

Stoneware decoration was common at least through the J. P. Smith period (1851–1854), and probably until the Civil War. As Alexandria recovered from its long occupation by Union troops, businesses struggled to survive. The use of cobalt may have been discontinued due to the costs of materials and labor. Undecorated jars, jugs, and other forms with the “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” mark are similar to those with the marks of Milburn’s sons.

STONEWARE BY MILBURN'S SONS

S. C. Milburn, 1867–1873

The “S.C.MILBURN.” stamp appears primarily on undecorated utilitarian wares, including jars, jugs, and milk pans with forms similar to those with his father’s mark (fig. 50). A spittoon (not illustrated) and a pitcher have sparse cobalt decoration (fig. 51).[40]

W. Lewis Milburn, 1871–1876

The mark “W. LEWIS MILBURN.” is found on just one rim sherd from the kiln site, from a one-gallon straight-sided jar with a square rim and collar (see fig. 10). Other surviving examples with this mark include similar jars and a squat, straight-sided, half-gallon jug with a straight rim (see fig. 76), which is similar to others marked “E.J.MILLER/ALEXA.” Milburn descendants were known to have had a pitcher marked in script “Mrs. W. L. Milburn / 1871,”[41] but even this special presentation piece was undecorated.[42]

E. J. Miller, 1865–1876

The Miller mark appears on five undecorated sherds from the kiln site, from vessels that include milk pans and jugs or bottles. While some of the Miller stoneware may have been made before B.C. Milburn’s death in 1867, S.C. Milburn probably manufactured most of the Miller pots between 1867 and 1873. Identical jars bear marks for B.C. Milburn, S.C. Milburn, and E. J. Miller (fig. 52).

E. J. Miller & Co. (also called E. J. Miller & Son) survived until sometime between 1907 and 1917. After the Wilkes Street Pottery closed, James Hamilton in Greensboro, Pennsylvania, supplied stoneware for E. J. Miller (fig. 53). Hamilton’s stoneware was sold to merchants in several states and is fairly common in Alexandria. It is easily distinguished from that made at the Wilkes Street Pottery, with a shiny brown Albany-slip interior and elaborate stenciled-cobalt advertising. Stenciling was never done at the Alexandria potteries, but is typical of the wares of southwestern Pennsylvania. The pots made for Miller were stenciled with various advertising for E. J. Miller & Co. or E. J. Miller & Son. The business was located at 65 King Street (now 317 King Street) until sometime between 1900 and 1907, and some of the stenciling includes this address. The design sometimes includes stenciled foliage, or may have wavy lines or a capacity mark and leaves in brushed cobalt.

HANDLES

A simple, straight lug handle with cut ends is found on pots with all of the marks used at Wilkes Street, beginning with Swann, and is found on ovoid jars, churns, cake pots, milk pans, and some coolers (fig. 54).

Extruded lug handles were introduced before 1847 on vessels marked “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C”. They are also found on ovoid jars with the later marks “B.C. MILBURN.” and “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” (fig. 55). Extruded handles were made by putting clay into a tube and using a plunger to force it through a template, in a way similar to a cookie press. This technique became more common on American stoneware, including that of the Shenandoah Valley, in the mid-nineteenth century.

Extruded strap handles were used in all periods. Vertical strap handles are found on pitchers, chamber pots, and coolers (fig. 56), while horizontal open-loop handles are found on larger coolers (fig. 57).

Throughout the history of the pottery, cylindrical jars and some smaller ovoid jars and milk pans were made with no handles.

RIMS

At least six distinct rim forms were used on stoneware from the Milburn period. Within these forms are numerous minor variations, such as small differences in size and angle. The most variation is seen in jar rims. Certain rim shapes were specifically designed to be used with stoneware or wooden lids (fig. 58). These include flared rims used on some jars and coolers (fig. 59), flat rims used on butter or cake pots (fig. 60), and tall, flared churn rims that allow a wooden or stoneware guide for the dasher to sit down inside the rim (fig. 61).

The round rim is the most common form on jars made throughout the history of the pottery (fig. 62). A new collared-rim form was introduced by Milburn sometime between 1831 and 1847 (fig. 63). This innovation was first seen, along with extruded lug handles, with the “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA. / D.C” mark, and the square rim with collar was documented with all of the marks from the Milburn period. The round rim with collar may have been limited to jars with post-retrocession B.C. Milburn marks. Collared rims are common on both ovoid and cylindrical jars. They appear on some jars with brushed-cobalt decoration and on all of the jars recorded with trailed-slip decoration. Collared rims were also common on Shenandoah Valley stoneware by the mid-nineteenth century.

VESSEL FORMS

Milburn expanded the repertoire of vessel forms produced at Wilkes Street. While eight vessel forms are known from the Swann period, fifteen forms were recorded for the Milburn period. Milburn continued to make butter pots, chamber pots, churns, jars, jugs, milk pans, and pitchers, but there is no evidence that he continued to make the portable earthen furnaces advertised by H. Smith & Co. in 1829. Additions in the Milburn period include banks, chimney pots, coolers, cups or bowls, flowerpots, spittoons, and stovepipe collars.

Banks. In her 1928 history of Alexandria, Mary C. Powell wrote that the Milburn Pottery made “little money jugs for children.”[43] No bank fragments were found at the kiln site, but Suzita Myers recorded a bank with a squat bottle form and tapered finial, made for B.C. Milburn’s son James Clinton Milburn (b. 1844), which was decorated with encircling leaves and buds.[44]

Bowls. A deep, straight-sided bowl was made for E. J. Miller after 1865 (see fig. 52).

Butter Pots. Butter pots are tall, straight-sided jars with lug handles and plain rims that are flat on top to support a lid.[45] Milburn’s 1859 trade card lists “butter jars” as covered wares.[46] A butter pot marked “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” has slip-trailed decoration (fig. 64). Rim fragments of twenty-eight butter or cake pots were found at the kiln site, but most if not all were from the earlier Swann period.

Chamber Pots. Only one chamber pot is known to have an Alexandria mark, from the earlier Swann period. However, several unmarked chamber-pot fragments, with flat everted rims and brushed or slip-trailed decoration typical of Wilkes Street, have been found on Alexandria archaeological sites (fig. 65).

Chimney Pots. An 1869 advertisement by S. C. Milburn mentions earthen chimney pots.[47] No fragments were found at the kiln site. Chimney pots would most likely be unmarked. If small fragments of cylindrical unglazed earthenware chimney pots have been found archaeologically in Alexandria, they have probably been misidentified as flowerpots or drainpipes. Some Milburn chimney pots probably still sit atop Alexandria houses.

Churns. Churns are tall and cylindrical with lug handles and flared or cup-shaped rims to support the stoneware or wooden disk holding the handle of the dasher. One churn recorded with the mark “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA.” and two with the mark “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” have brushed-cobalt decoration and flared rims (fig. 66). Milburn’s 1859 trade card listed churns under the heading of covered ware. Henry Wolff’s 1874 mechanic’s lien against W. Lewis Milburn mentions that he made three- and four-gallon churns.[48]

Coolers. The four coolers recorded from Alexandria are from the Milburn period. Coolers have an ovoid shape, a bunghole near the bottom, and a variety of rims and handles. Also known as fountains or kegs, these vessels could have held water, cider, or liquor. Two coolers are marked “H.C.SMITH /ALEXA. / D.C” (ca. 1831–1847), and two are marked “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” (after 1847).

The Smith mark is found on the simplest cooler, shaped like a pitcher but with two strap handles and a bunghole (fig. 67). The mark is also found on the most elaborate cooler, with extruded horizontal handles, a straight rim, and unusual decoration with filled incised lines.

One of the Milburn coolers with slip-trailed decoration (not illustrated) is shaped like a jar, with a slightly tapered body, lug handles, and a flared rim. The bunghole identifies it as a cooler. The other, with a brushed-cobalt design, has a square rim with collar like that used on jars, and strap handles of the type usually seen on pitchers (fig. 68).

Cups. A 1945 article in Antiques illustrates a “Brown Stoneware Whimsey,” a small mug made at the Milburn Pottery for James McCormick Eaches and bearing his initials; it is dated 1867 on the reverse. The cup was an heirloom of the author, Nancy Lee Tackett. The small brown stoneware cup has a flat bottom, no handle, three incised lines below a slightly flaring rim, and the initials JME written in script.[49]

Flowerpots. Milburn advertised in 1845 that he had “just finished burning a kiln of flower pots of all sizes—from 11 inches to 2 inches.”[50] Flowerpots are also listed on his 1859 trade card and in his son S. C. Milburn’s 1869 advertisement. Unglazed earthenware flowerpot fragments were found at the kiln site, in four- to eight-inch sizes. Flowerpot trays were also found. The pots have either a slight bulge at the rim or a double flange. Most of the trays are plain with a flat or rounded rim, but some have an incised line just below the rim. One stoneware flowerpot was found archaeologically with the mark “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.”; it is undecorated, light brown in color, and has a plain rounded rim (fig. 69). Swann does not appear to have made flowerpots, but they were made by earlier earthenware potters Henry Piercy and Lewis Plum, and by Tildon Easton, who made them in both earthenware and stoneware.

Ink bottles. One master ink bottle was documented, with the “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” mark. This cylindrical bottle has a flat top and rounded rim (fig. 70).

JARS

Jars, the most common form, were made in many shapes and sizes. Jars have been found with each of the impressed marks from the Wilkes Street Pottery. The stamps of merchants Dubois & Reddick and J. P. Smith were found only on jars. Jars usually have capacity marks, ranging from one-half gallon to six gallons. Jars are one of the forms itemized in the 1874 lien against W. Lewis Milburn.

Ovoid jars. There is considerable variation in the shape of ovoid jars, from rounder to more tapered forms, but there are many gradations and no clear trends over time (fig. 71). These are wide-mouthed jars with an opening at least as large as the base. Half-gallon jars have no handles, whereas larger ones have lug handles.

Cylindrical jars. Cylindrical jars have no handles and range from one-half gallon to three-gallons. They are straight sided, and may be truly cylindrical or slightly wider at the shoulder. These jars mostly have rounded shoulders, with rims nearly the same size as the base (fig. 72).

Lidded jars with flared rims. Squat, ovoid, lidded jars with tall, flared rims come in sizes from one-half gallon to one-and-one-half gallons, and even the smallest jars of this shape were made with lug handles (fig. 73). The earliest jars of this form have Swann’s mark, but they are more common with the “B. C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C.” and “B.C.MILBURN /ALEXA.” marks. A small ridge is sometimes found at the neck, beneath the flared rim.

Small-mouthed jars. A few small-mouthed jars have more sharply angled shoulders (fig. 74), similar in shape to glazed earthenware preserve jars made in the 1790s in Alexandria and earlier in Philadelphia.

Fruit jars with cork and cement. Milburn’s 1859 trade card lists “fruit jars, with cork and cement” (fig. 75). The “cork and cement” may refer to small, flat stoneware lids found on an Alexandria archaeological site. These have a pointed protrusion that would fit down into a cork ring. In 1868 china merchant E. J. Miller advertised glass fruit jars and “Also, stone jars, of all sizes, pint to 6 gal. Stone fruit jars, quart and half gallon, just as good for putting up tomatoes as the best glass jars, and about one half the cost of glass.”[51]

JUGS

Jugs, made to hold liquids, have a narrow neck and a strap handle springing from the shoulder. Milburn’s jugs were straight-sided or slightly ovoid, while Swann’s were ovoid. The rims also changed over time, from Swann’s ringed necks to Milburn’s straight narrow necks with collars, which look like the tooled lips with string rings used on nineteenth-century glass liquor bottles (fig. 76). In a variation, a plain square rim sits above a thin, slightly wider ridge. Jugs are often marked with their capacity, with the smallest size a half-gallon. Jugs are listed in advertisements and on the 1859 Milburn trade card. Wolff’s 1874 lien lists half-, one-, and two-gallon sizes. No decorated jugs were recorded from the Milburn period.

MILK PANS

Milk pans were made throughout the years of production at Wilkes Street, though none has been recorded with the “B. C. MILBURN, / ALEXANDRIA D. C.” or “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA.” marks. Milk pans are mentioned on Milburn’s 1859 trade card and in Wolff’s 1874 lien.

The Alexandria milk pans range from deep and narrow to wide with more steeply sloping sides, but there appears to be no significant change in shape over time. They were made both with and without lug handles. Milk pans have flat rims with a square band, or just an incised line to separate rim from body (see figs. 45, 50). The Milburn marks were used on milk pans with brushed-cobalt and slip-trailed decoration. Undecorated milk pans were also made with this mark and with the stamps of S.C. Milburn and E. J. Miller.

PITCHERS

Pitchers have been documented with all of the various marks. Most Alexandria pitchers are a baluster shape with an ovoid bottom and a cylindrical or slightly flaring neck (fig. 77).[52] Most of the pitchers have a plain rim, or a small rounded ridge at the top. A pitcher marked “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA./ D.C” has a flat, square rim, similar to one on jars and milk pans. Another, marked “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” has a rim with three ridges. A pitcher in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum bearing the same mark, has a cylindrical body with a sharply defined shoulder (fig. 78). In the second half of the nineteenth century, the baluster and cylindrical shapes were both used in the Shenandoah Valley as well.

SPITTOONS

All of the recorded spittoons were manufactured after 1847. One decorated example has the typical round flower in brushed cobalt and the mark “B C MILBURN” (fig. 79). This vessel has an incised line below the angled shoulder and another at the waist. Another decorated spittoon, originally used at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and now in a private collection, is most unusual in that it is marked S.C.MILBURN”. Decorated with three-leaf sprigs, it has a grayish brown glaze, a double incised line below a rounded shoulder, and another line above the base.[53]

Alexandria’s Beth El Hebrew Congregation had at least eight Milburn spittoons in the nineteenth century, and still owns two plain ones.[54] One plain, “B.C. MILBURN.” spittoon found on an archaeological site in Alexandria is of light-brown stoneware with a rounder shoulder and no incised lines (fig. 80). A plain, gray stoneware spittoon marked “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA.” has incised lines at the shoulder and just above the base. One stamped for merchant E. J. Miller is similar, but with a double-incised line at the shoulder.

STOVEPIPE COLLARS

Stovepipe collars are listed on Milburn’s 1859 trade card, but no fragments were found at the kiln site; such an object would not have had a maker’s mark. As with chimney pots, fragments might not be identifiable in the archaeological record.

Summary

B.C. Milburn established his place in the history of American stoneware—and in the hearts of collectors—with his business acumen and his beautifully decorated wares. He built on the work of his struggling predecessor, John Swann, putting the business on a firm footing so that it served a regional market. Archeological excavations indicate that while Milburn’s pottery was in operation very little nonlocal stoneware was used in Alexandria.

By the time the Wilkes Street Pottery closed, nearly a decade after B.C. Milburn’s death, small manufactories were being replaced by larger ones and by more industrialized technologies. Railroads transformed the landscape in the 1850s and 1860s and made it profitable for larger industrial potteries to develop in the Ohio Valley and to transport yellow ware and ironstone to eastern destinations such as Alexandria. Yellow ware and ironstone replaced old-fashioned stoneware chamber pots, pans, and baking dishes. Glass screw-top canning jars, first manufactured in 1858, were sold alongside Milburn’s stoneware canning jars in an 1868 ad, and had replaced them a decade later. The preference for lower-priced and more uniform industrial goods increased as the century passed, dooming the smaller stoneware manufacturers. After the local manufactories closed, larger stoneware manufacturers such as James Hamilton in Greensboro, Pennsylvania, supplied the more limited needs of Alexandria and other towns for stoneware jars and jugs.

Milburn’s manufactory closed in 1876, but many examples of his beautiful stoneware live on, more than 130 years later. Today the Tannery House Condominium sits on the property, and a plaque marks the site of the old Wilkes Street Pottery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to collectors of Alexandria stoneware who shared their expertise and were so willing to allow their precious pieces to be examined and photographed for this article. I also thank Kristen Lloyd of The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum and Bonnie Lilienfeld of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, for the loan of stoneware for this project. I am indebted to the late Suzita C. Myers as well as C. Malcolm Watkins, and John K. Pickens for their research on the history of the Alexandria potters, and to Alain Outlaw, who organized rescue excavations at the Wilkes Street Pottery in 1977. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of my colleagues and volunteers at the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.

The author would appreciate learning about additional collections of Alexandria stoneware and, in particular, about pieces that are different in appearance from those described in this article.

The quotation is from an advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette, September 15, 1841, for merchant Robert H. Miller, whose King Street shop sold “China, Queensware and Glass.” Alexandria stoneware manufactured by Benedict C. Milburn, and Miller’s imported goods, were marketed to a wide area. The advertisement indicates that the notice was also to be published in the National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown Advertiser, Warrenton Times, Winchester Republican, Leesburg Genius of Liberty, and Williamsport Banner.

In the nineteenth century, Alexandria stoneware was advertised widely in Virginia newspapers—in Fredericksburg, Falmouth, Leesburg, Winchester, Warrenton, and Williamsport—as well as in Georgetown and Washington, D.C.

Barbara H. Magid, “‘Stoneware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture,’ Part 1: The Pottery of John Swann,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2012), pp. 111–45.

Alexandria Deed Book B-3, pp. 228–29, Alexandria Circuit Court Record Room.

Mary G. Powell, The History of Old Alexandria, Virginia, from July 13, 1749 to May 24, 1861 (Richmond, Va.: William Byrd Press, 1928), p. 305.

Brandt Zipp and Mark Zipp, “James Miller, Lost Potter of Alexandria, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 253–61; Barbara H. Magid, “A New Look at Old Stoneware: The Pottery of Tildon Easton,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 249–52.

Magid, “‘Stoneware of excellent quality,’” pp. 118–19.

Suzita Cecil Myers, The Potters’ Art: Salt-glazed Stoneware of 19th-Century Alexandria, Alexandria Archaeology Publications 91 (1983; 2nd ed., Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Archaeology, 2003), p. 23, citing Ann Hebb Wintzer family papers.

Alexandria Gazette, July 16, 1832.

Alexandria Gazette, June 16, 1828. According to the notice, Milburn purchased Black’s interest on June 1, 1828, and continued to operate the grocery business.

J. Clinton Milburn advertised a family grocery store on the northeast corner of Royal and Cameron streets in 1865 and remained in the grocery business until his death in 1912. John K. Pickens, “B.C. Milburn and the Alexandria Pottery” (n. d.), files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and the Pickens Papers box 57, Alexandria Library, Special Collections.

Alexandria Gazette, February 19, 1869.

Alexandria Gazette, December 20, 1839.

Alexandria Gazette, July 16, 1832. Court documents list Black’s personal property as “about two tons of clay for making stoneware and a small quantity of stoneware”; see Arlington County Insolvent Debtors: 1826–1833, pp. 379–82, Alexandria Library, Special Collections, microfilm reel 00548.

Magid, “A New Look at Old Stoneware,” pp. 249–52. Bankruptcy announcement in the Alexandria Gazette, February 20, 1843.

Papers of Suzita C. Myers, in the files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.