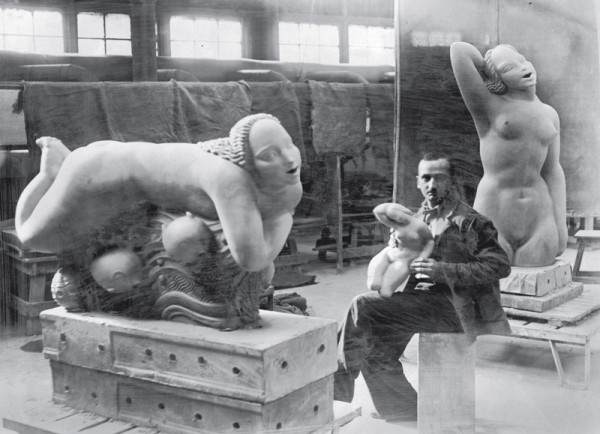

Waylande Gregory, The Swimmer, ca. 1933. (Photo, courtesy Waylande Gregory Archives.) Gregory is holding a female nude sculpture; behind him is The Bather, ca. 1933.

Lorado Taft and students boarding a plane from London to Paris, ca. 1928. Gregory is on the far left; Taft is fourth from the right. (Photo, courtesy Waylande Gregory Archives.)

Waylande Gregory, Light Dispelling Darkness, 1936–1938, installed in Roosevelt Park, in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Concrete. H. approx. 20'. (Photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Universal Peace, from Light Dispelling Darkness. (Photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Agriculture and Industry, from Light Dispelling Darkness. (Photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Pestilence, from Light Dispelling Darkness. Glazed terracotta. H. 3'. (Photo, Randl Bye.)

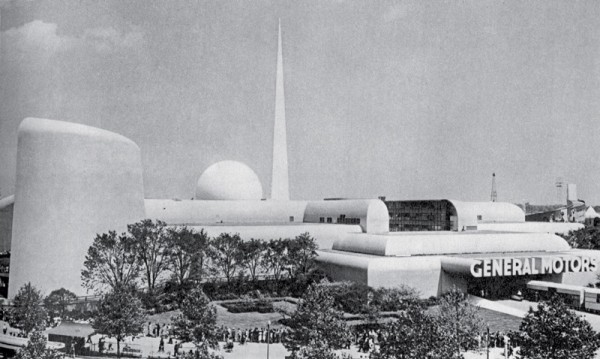

New York World’s Fair, 1939, with the Perisphere and Trylon by Wallace Harrison rising behind the General Motors Building, designed by Norman Bel Geddes.

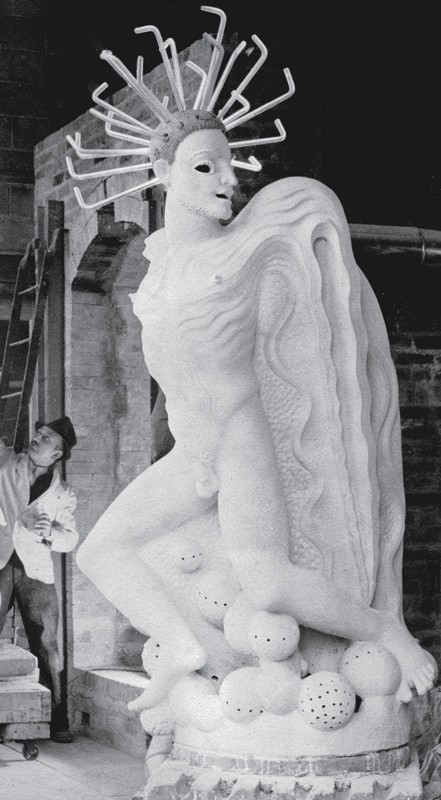

Waylande Gregory, Fountain of the Atom, 1939, installed at the World’s Fair, Queens, New York. Reproduced from Ross Anderson and Barbara Perry, The Diversions of Keramos: American Clay Sculpture, 1925–1950, exh. cat. (Syracuse: Everson Museum of Art, 1984), p. 3.

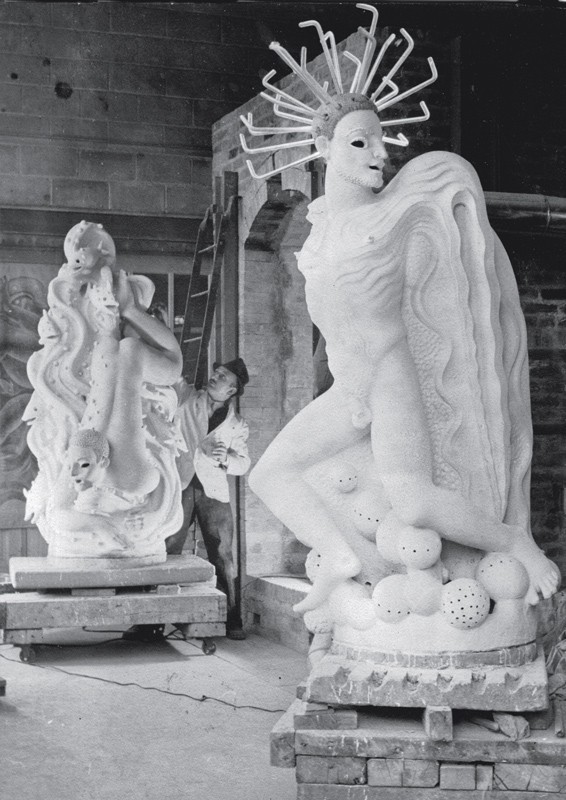

Waylande Gregory, Water (background) and Air (foreground), ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware. H. 72". (Courtesy, Cranbrook Academy [Water] and private collection [Air]; photo, courtesy Waylande Gregory Archives.) Installed at the 1939 World’s Fair; note the artist alongside Water in this studio photograph.

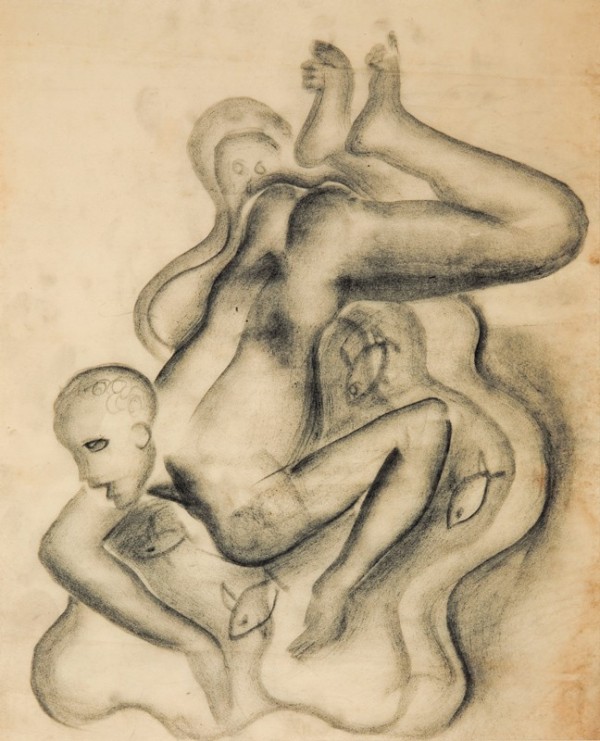

Waylande Gregory, preliminary drawing for Water, ca. 1938. Charcoal on paper. 15" x 13". (Courtesy, private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, maquette for Water, ca. 1938. Glazed earthenware. H. 22". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, maquette for Earth, ca. 1938. Glazed earthenware. H. 22". (Courtesy, Lea Allen Gebauer collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Earth, ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware. H. 77". (Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Air, ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware. 65" x 35" x 39". (Courtesy, private collection; photo, Waylande Gregory Archives.)

Waylande Gregory, Fire, ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware. 76" x 41" x 41". (Courtesy, private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Female Electron, ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware. 50" x 25" x 25". (Courtesy, Marty and Judy Stogniew Collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory, Male Electron, ca. 1938, from Fountain of the Atom. Glazed earthenware, 48" x 26" x 26". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

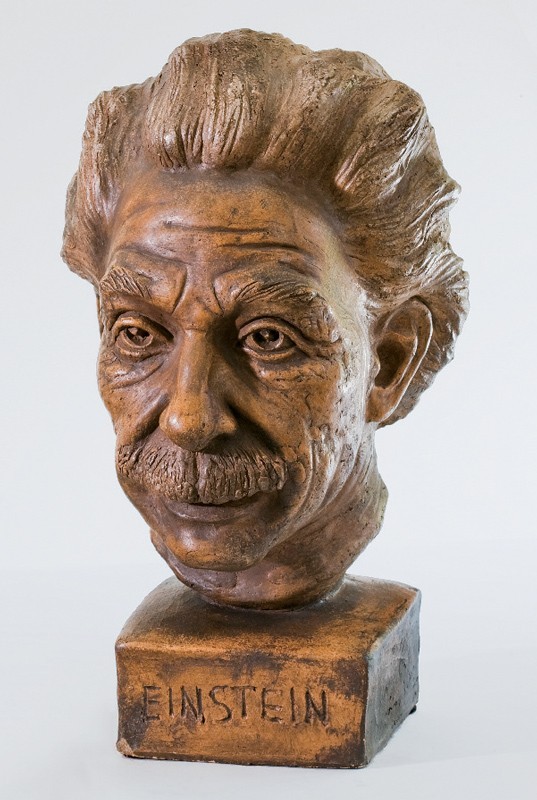

Waylande Gregory, Portrait of Einstein, ca. 1940. Glazed terracotta, 15" x 5" x 6". (Courtesy, Marty and Judy Stogniew Collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Gregory’s use of his “honeycomb technique” on Mother and Child, ca. 1936. (Photo, courtesy Waylande Gregory Archives.)

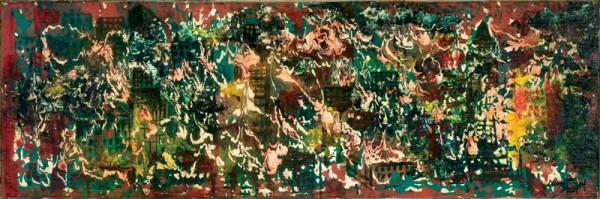

Waylande Gregory, Atomic Holocaust, ca. 1950. Oil on wooden panel. 17" x 47". (Courtesy, Ron Wei; photo, Randl Bye.)

Waylande Gregory is regarded by many as a leading figure in twentieth-century American ceramics. A retrospective exhibition, sponsored by the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia, will be at the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, from November 16, 2013, to March 23, 2014. The presentation and an accompanying biographical book by the author shed new light on this revolutionary, innovative and, at times, controversial artist (fig. 1).

Gregory was born in 1905 in Baxter Springs, Kansas, and grew up on a ranch near a Cherokee reservation. He was something of a prodigy, and became interested in ceramics when as a child he witnessed their use during a Native American burial. He was also musically inclined and took lessons from his mother, who had been a concert pianist. At eleven, he was enrolled at Kansas State Teacher’s College, where he studied carpentry and crafts, including ceramics.

Gregory’s early development as a ceramic sculptor was shaped by the encouragement and instruction of Lorado Taft, a leading American sculptor who worked primarily in bronze and marble, and by Guy Cowan, a leading American ceramist. Gregory had caught the attention of Taft after moving to Chicago in 1924. Taft was known to mentor important American sculptors, among them Janet Scudder, and he invited Gregory to study with him privately for eighteen months and to live and work with him at his famed Midway Studios, a complex of thirteen rooms overlooking a courtyard. Taft may have been responsible for getting Gregory interested in creating large-scale sculpture.

By the 1920s, however, Taft’s brand of academic sculpture was no longer considered progressive. Gregory, who visited Europe with Taft and other students late in the decade (fig. 2), was increasingly drawn to the latest trends of the United States and Europe, and his career in the 1930s mirrored the changing focus of American ceramics from art pottery to studio pottery.

“Kid Gregory,” as he was known, was hired circa 1928 by Guy Cowan, the founder of the Cowan Pottery in Cleveland, Ohio. Cowan’s family had been in the pottery business for generations, and he was one of the first graduates of the New York State School of Clay-working and Ceramics (now the New York College of Ceramics at Alfred University), which was founded in 1900 and had one of the first programs in production and studio pottery. Cowan, who may have known about pottery production but lacked training as a sculptor, hired Gregory to be the pottery’s sole full-time employee, and from 1928 to 1931 Gregory served as its chief designer and sculptor. The focus of the Cowan Pottery was on limited-edition, tabletop ceramic sculptures, the majority of which Gregory designed, including the well-known Nautch Dancer and Burlesque Dancer. These sculptures referenced Gilda Grey, a popular entertainer of the 1930s who posed for Gregory in the creation of these works.

The shift away from art pottery is reflected in Gregory’s next career move when, in 1932, he left the Cowan Pottery, which had fallen victim to the Great Depression, and became the instructor of ceramics at Cranbrook, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Colleges with emerging ceramics programs were instrumental in creating a new role for ceramists. At Cowan, Gregory had enjoyed an able staff to assist him in all phases of production, which is typical of an art pottery. As a studio potter at Cranbrook, however, Gregory directly handled all phases of production—from modeling to glazing to firing. Although he remained at Cranbrook for only a year and a half, it was an extremely productive period for him. He was part of the school’s illustrious faculty, which included the architect Eliel Saarinen and sculptor Carl Milles, and he created two of his finest ceramic sculptures, Kansas Madonna and Girl with an Olive.

In the summer of 1933, Gregory moved to Metuchen, New Jersey, and became very involved in the government-sponsored Works Progress Administration (renamed Work Projects Administration in 1939), better known as the WPA. His mentor, Lorado Taft, had created several fountains and may have inspired Gregory to work on fountain themes. In 1936 Gregory began to plan Light Dispelling Darkness (fig. 3), a fountain to be constructed in Menlo Park in part as a tribute to Thomas Edison, who had developed the incandescent light bulb there. The installation, which is still in place today, was financed by the WPA and the Middlesex County Board of Freeholders.

By 1937 Gregory had been appointed the state head of the sculpture division of the WPA. In an effort to revive interest in commercial terracotta production, which by this time was starting to lose public interest, he selected ten men to assist him in the construction of Light Dispelling Darkness at the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company in nearby Perth Amboy; the terracotta elements were sculpted from local Amboy clay. Although the assistants had no previous knowledge of ceramics, it was hoped that the experience they gained could help them find future employment in the ceramics industry.[1]

The overall theme of Light Dispelling Darkness was the triumph of mankind over evil, achieving universal peace through science, industry, and education (fig. 4). Although the fountain is dedicated to Edison, the inventor is not directly represented or suggested in any of the figures. One of the three reliefs on the central pillar depicts Science and Achievement as a group of professionals at work in their fields of electrical and medical sciences. A figure with a dynamo symbolizes the power available to man through knowledge and perseverance; a man looking through a microscope symbolizes scientific research.

The fountain’s circular basin, constructed of concrete aggregate, is forty feet in diameter; its central, bas-relief pillar, also of concrete, is ten feet in diameter and fifteen feet high. The pillar, which is surmounted by a brightly glazed terracotta globe, bears relief figures representing man’s achievements in science, industry, medicine, the arts, and other areas. In the relief depicting Agriculture and Industry (fig. 5), for example, Gregory shows some of the marvels of technology of the time: skyscrapers, zeppelins, and ocean liners. In the basin surrounding the pillar, fleeing the “light” of science and knowledge, are six three-foot-tall glazed terracotta figures depicting the evil forces that prey on mankind—Greed (intertwined octopi), Materialism (spewing a ribbon of stock-market ticker tape), and Famine, Pestilence, War, and Death (presented as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse).[2]

Pestilence (fig. 6), the first of the Four Horsemen, is shown as a diseased figure with a flowing cape, its body colored blue with bright yellow dots suggesting open sores. The figure almost has a Pop Art quality.

Famine is shown as an emaciated old figure with flowing blond hair riding an equally emaciated horse. The figure is nude, and carries an unbalanced scale in its left hand, symbolizing inequality.

War is depicted as a Roman centurion or soldier clinging to his fallen horse. He wears a contemporary gas mask and a shield adorned with a skull.

Death, a skeleton wearing a flowing black cape and emitting a jagged lightning bolt, is astride a frantic horse.

These figures, arguably the most interesting part of the fountain, are among Gregory’s first large-scale ceramic works.

In 1938 Gregory began construction of his new house at 16 Mountain Trail, in the Watchung Mountains of Bound Brook (now Warren), New Jersey. The house, completed in 1939, was constructed of concrete and almost had a California, rather than a New Jersey sensibility, reflecting the influence of Gregory’s architectural hero, Frank Lloyd Wright. It does not relate to Wright’s Prairie School houses of Chicago, however, but rather to his concrete California houses of the 1920s. The enormous custom kiln was probably included in the initial construction of the house.

The year 1939 also marked a major point in Gregory’s professional life, with continued public recognition of his work, specifically his Fountain of the Atom, commissioned by the World’s Fair Corporation and his most important work. The 1939 World’s Fair, situated historically between the Great Depression and World War II, proved to be a microcosm of the rapid changes occurring in the larger world. The theme of the fair was “Building the World of Tomorrow” and it was opened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 30, 1939 (and closed two years later), offering its 44 million visitors an optimistic view about new technology. The two iconic white buildings most associated with the fair were the Perisphere (200 feet in diameter) and the Trylon (more than 700 feet tall), both designed by Wallace Harrison (fig. 7). Within the Perisphere, visitors witnessed a diorama of the city of tomorrow called “Democracity.”

The most popular exhibit was “Futurama,” designed by Norman Bel Geddes and installed in the General Motors Building (also designed by Bel Geddes). This is where Gregory exhibited two additional groupings of ceramic sculptures, Imports and Exports. New means of transportation were also very evident at the fair, including the futuristic Chrysler Airflow automobile, a transport plane, and the world’s fastest train—the 6100—a sleek steam locomotive designed by Raymond Lowey.

The World’s Fair, for which Gregory served as an adviser, proved to be the most significant display of art and design in America since the opening of Rockefeller Center in the early 1930s. In addition to the design contributions of Harrison, Bel Geddes, and Lowey, the fair displayed a significant number of works by American sculptors—Malvina Hoffman, Paul Manship, Carl Milles, William Zorach, and others—many of whom worked in bronze; Gregory was the only sculptor to produce monumental outdoor ceramic sculptures.

Gregory’s interest in atomic energy was vividly demonstrated by his Fountain of the Atom (fig. 8), on display at the entrance of the newly constructed railway entrance at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Composed of twelve large-scale nude and seminude ceramic figures—eight electrons (illustrated in the March 13, 1939, issue of Life magazine) and four elements—this major work was fanciful, artistic, and compelling. The installation visualized the growing international interest in atomic energy and may be seen as Gregory’s crowning achievement, as well as the culmination of his interest in monumental ceramic sculpture.[3] To help him move these huge sculptures, Gregory hired an African-American father-and-son team, Tyson and Ralph respectively, who resided on the third floor of Gregory’s new house. Unfortunately, their last name has been lost to time.

Fountain of the Atom was located on Bowling Green Plaza, very close to the subway that had been renovated for the fair. Partly because of its location, the fountain received considerable attention, including the photographs in Life magazine and even a review in the international press.[4] The fountain itself had a steel frame and was constructed of glass bricks. It consisted of a bluish green pool, sixty-five feet in diameter, beneath two concentric, circular tiers, or “terraces” as Gregory called them, the first of which was wider than the second. In the first terrace, relating to the valence shell of an atom, were eight electrons: four male and four female terracotta figures, each approximately 48 inches tall. Above them, on a narrower terrace representing the nucleus of an atom, were four much larger and heavier terracotta figures depicting the Elements, each averaging about 78 inches in height and weighing about one and a half tons: Water and Air (fig. 9) are portrayed as male in gender; and Earth and Fire are portrayed as female. All of the figures were fired in Gregory’s new kiln in Warren.

In the center of the fountain, above the elements, was a central shaft of sixteen glass tubes from which water tumbled down, from tier to tier. At the top, a bright flame burned constantly. The glass-block tiers were lit from within, and this, combined with the flowing waters, created a glowing, gurgling effect. Since the fair was temporary, the figures could be removed after its closing. Credit for the design of the structure of the fountain belongs to collaborator Nembhard Culin, who was responsible for several other structures on the fairgrounds as well.[5]

Since so much of the fair focused on new technology, Gregory was very much on target with his design showing the new science of the atom. According to what is known as the “octet rule,” atoms tend to combine in such a way that they each have eight electrons in their valence shells, typical of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. Molecules tend to be most stable when the outermost electron shells contain eight electrons. But Gregory interpreted this theme artistically using nude figures rather than atomic models, with the elements and the electrons depicted as allegorical figures that represent scientific ideas. The use of allegorical subjects relates to the sculpture of Lorado Taft and the Beaux Arts use of such figures in art, though Gregory’s figures are very modern, not Beaux Arts. Paul Manship’s bronze figures for the fair, equally allegorical although Art Deco in style, offered fairgoers his Time and the Fates Sundial (now at Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina) and Four Models of Time. At the time Gregory sculpted Fountain of the Atom, he had gone beyond Art Deco stylization and was working in a more personal style. The rounded, fleshy nudes had already appeared in some of his monumental works, for example The Swimmer and The Bather, both of which were created circa 1935. This trend culminated in the female nudes for Fountain of the Atom.

Perhaps the most popular of the four elements was Water, ca. 1938 (see fig. 9). In a preliminary drawing for it (fig. 10), Gregory captured the movement of the nude male figure diving down surrounded by fish. Although Gregory never specifically mentioned the ethnicity of Water’s swimmer, he appears to be an African-American, and studio photographs suggest that Gregory’s assistant Ralph might have been the model. The pose is untraditional and unclassical, as the diver seems weightless and is depicted upside down. The finished version of Water was the most colorful of the four elements, with yellow bubbles and pink fish. The glaze is particularly glassy and watery, as Gregory was attempting to interpret the transparent nature of water. The maquette for Water (fig. 11) may be one of the artist’s most successful; indeed, he had exhibited it independently of the others.

Another popular representation was Earth, for which Gregory modeled a highly detailed and beautifully glazed maquette (fig. 12); however, the finished version (fig. 13) has harsher features and a more primitive quality. Gregory admitted that Earth, conceived as a “proud earth woman with a great shock of hair and wrapped in a mantle of green,” was his favorite.[6] Her torso is exposed and she sits, goddess-like, on a throne of minerals. Gregory said that he had visualized Earth as “agelessly young, fecund, and virginal, engrossed in the mysteries of evolving.”[7] Traditionally, however, earth goddesses in Western art are represented with maternal, not virginal, qualities.

Perhaps the strangest of the four elements was Air (fig. 14), represented by an alien, somewhat like Milton’s Lucifer, “a heroic, angel-like demon male figure, naked, winged, swift in movement and evanescent in coloring.”[8] The figure, standing on bubble-like clouds, had a mischievous smile and many rods protruded from his head, creating a bizarre halo.[9] Gregory created a self-portrait bust of himself as the devil when he was residing in Cleveland; Air might have been a self-portrait as well.

In Fountain of the Atom, atomic energy became a metaphor for sexual energy. Fire (fig. 15) was all about sexual passion; the nude female figure had exaggerated, upward-pointing nipples that underscored her sexuality. Gregory described Fire as “an aquiline female figure being consumed in endless arabesques of flame.”[10] As with Water, openings in the sculpture enabled the viewer to see inside the flames.

In the end it was the electrons, rather than the elements, that received the most attention. Also sculpted from Amboy clay and constructed in the same manner as the elements, these brightly colored figures had a charged sensibility. Gregory described them as “elemental little savages of boundless energy.”[11] Two of the four female electrons were fierce and played with bolts of electrical energy; one had strange prominent eyes, mounted forward of their orbits (fig. 16). Two of the four male electrons were like Water in that they were depicted upside down. Whereas Water focused on the side and rear of the male figure, these two focused the viewer’s attention on the front and genital area. Surprisingly, the figures were publically displayed yet apparently caused no controversy. One of the electrons had fins and wore a finned crown (fig. 17). The male electrons seemed to be modern interpretations of putti from Renaissance art, boy angels symbolic of erotic love.

Albert Einstein and his entourage had visited the fair and viewed Fountain of the Atom. Einstein was very much impressed and is said to have told Gregory, “Young man, I wanted to meet the artist who gave honor to the atom.”[12] The two men struck up a friendship, and Gregory went to Princeton to make studies so that he could sculpt Einstein’s portrait in terracotta (fig. 18). Gregory had sculpted the terracotta portraits of several celebrities by then, including two of actor Henry Fonda, a personal friend. Gregory made studies of Einstein from the back of his classroom while the scientist was lecturing to his students, and the final sculpture is an accurate likeness. It is significant that Gregory’s Fountain of the Atom was somewhat playful in nature; by the end of World War II, many people would look at technology and the machine in a much more negative light.

Always interested in helping other Cleveland artists, in October 1938, as an advisor to the fair, Gregory asked Cleveland ceramist Viktor Schreckengost to submit a proposal for four ceramic heads also depicting the four elements of Earth, Water, Fire, and Air. After some initial confusion, the noted industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague accepted Schreckengost’s heads for his interior design in the United States Building.[13] Another Cleveland ceramic artist, Edris Eckhardt, exhibited a single head, representing Earth, at the fair. It is clear that Gregory continued to exert a strong influence on the Cleveland School for several years after he left the Cowan Pottery.

Gregory was the first modern ceramist to create large-scale ceramic sculptures. Similar to the methods developed by the ancient Etruscans, he fired his monumental ceramic sculptures only once. But the new technologies in ceramics of the twentieth century were rapidly changing the industry, and Gregory was at the cutting edge of new developments. To create his monumental works (some measure more than seventy inches in height and weigh well more than a ton) the artist developed a “honeycomb technique” (fig. 19), in which an infrastructure of interlaced compartments was covered by a ceramic “skin.” These works were fired by Gregory himself in the huge kiln he had constructed at his home and studio. Gregory described his process in 1944:

Because great thickness of clay cannot be dried and fired successfully, and for other reasons as well, the ceramic work must be constructed hollow, somewhat in the spirit of architectural engineering. Due to shrinkage, no support other than clay can be used. The intense heat of 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, and more, would burn away all metal or wooden supports or armatures, even if they could be used. Therefore, the structure of the sculpture itself must be entirely of clay, self-supporting from within the sculpture and plan of the sculpture. The sculptural form sequence must be so conceived that it is possible to construct and engineer the work to enable it to survive the stress and strains of drying shrinkages, fire shrinkage, and chemical changes without collapsing or developing cracks. This is not a thing that can be achieved by short cuts. It has taken me many years to acquire this knowledge and experience that it requires to build the massive monumental scaled sculptures that I am now creating. . . . Such sculptures are highly permanent, retain all the texture and veracity of the direct modeling, have great color and distinction over other sculptural mediums.[14]

Gregory fired his monumental sculptures in cone 7 (a level of kiln firing). While working on them, the inner core had to remain moist enough so new wet clay could be added to the sculptures but dry enough so they would not sag. The figures then had to dry before being glazed and fired. After they were placed in the kiln, the entrance to the kiln was walled in with bricks, and the sculptures were fired for two to three weeks. This brick wall was removed after firing, at which time the artist would examine his finished work.[15]

About 1950 Gregory returned to the subject of the atom, although this time in an oil painting rather than a ceramic sculpture. Atomic Holocaust (fig. 20) shows a city on fire, evaporating in a blaze of color. Although the painting shows the negative effects of nuclear energy—by the end of World War II most people shared a fear of nuclear annihilation—Gregory focused on the expression of color rather than the human tragedy.

Clearly, the 1939 World’s Fair was Gregory’s day in the sun. Although he continued to produce a great variety of artwork in ceramics, metal, glass, and paintings, he never again approached the success he had enjoyed with Fountain of the Atom. By the same token, even though other sculptors—Robert Arneson, Viola Frey, and Peter Voulkos, for example—tried their hand at monumental ceramic sculpture, no one has attempted Gregory’s very personal, sophisticated technique.

The exhibition “Waylande Gregory: Art Deco Ceramics and the Atomic Impulse” was organized by the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia, and travels to the Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, November 16, 2013– March 23, 2014, then to the Canton Museum of Art, Ohio, May 1–July 27, 2014.

The men who worked on Light Dispelling Darkness included John Corollo, William Deuel, Joseph Kalik, Dominick di Lorenzo, Amadeo Lovi, Henry Lovi, Adolph Maffei, Ned Monti, Andrew Petrovits, and Alfred Rossi.

Gregory’s description of the iconography he used in Light Dispelling Darkness is recorded in an undated letter to the Newark Museum, Newark Museum Archives. I would like to thank Jeffrey Moy, the museum’s librarian, for his assistance.

For more on Gregory, see his first monograph, Waylande Gregory: Art Deco Ceramics and the Atomic Impulse, exh. cat. (Richmond, Va.: University of Richmond Museums, 2013). See also Thomas Folk, “Waylande Gregory,” Ceramics Monthly 42, no. 9 (November 1994): 27–32; Gene DeGrusin, “No Greater Ecstasy: Waylande Gregory and the Art of Ceramic Sculpture,” Kansas Quarterly 14, no. 4 (Fall 1982): 65–82; and Elaine Levin, “Monumental Ambitions: Waylande Gregory,” American Ceramics 5, no. 4 (1987): 40–49.

See “World’s Fair, Surprise! Surprise! Surprise! They Will Lurk at Every Turn. These Little Savages are Electrons,” Life 6, no. 11 (March 13, 1939): 37; and “The Octet Theory of the Atom in Terra Cotta: The Fountain of the Atom at the New York World’s Fair,” The Illustrated London News, April 29, 1939, p. 719.

Waylande Gregory, cited in Margaret Lindsay, “Unique Sculpture for World’s Fair Created in Bound Brook Studio of Waylande Gregory, Ceramic Artist,” The Sunday Times (New Brunswick, N.J.), March 5, 1939, p. 1.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Bianca Brown, a personal friend of Waylande Gregory and his wife, Yolande, related Gregory’s experiences with Einstein and Gregory’s subsequent portrait bust of him in a telephone conversation with the author, November 4, 1999.

Gregory’s interest in Schreckengost’s submission of his The Four Elements in the 1939 World’s Fair is related in Henry Adams, Viktor Schreckengost and 20th-Century Design, exh. cat. (Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2000), pp. 72–73.

Waylande Gregory, cited in Ernest W. Watson, “Waylande Gregory’s Ceramic Art: Interview,” American Artist 8, no. 7 (September 1944): 14.

Lorraine Hoogs discusses the techniques Gregory used in the monumental sculptures he fired in his New Jersey home, in Ross Anderson and Barbara Perry, The Diversions of Keramos: American Clay Sculpture, 1925–1950, exh. cat. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Everson Museum of Art, 1983), pp. 19–22.