Left: Ivor Noël Hume and Michelle Erickson. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.) Right: Jacqui Pearce (photo, courtesy of the author).

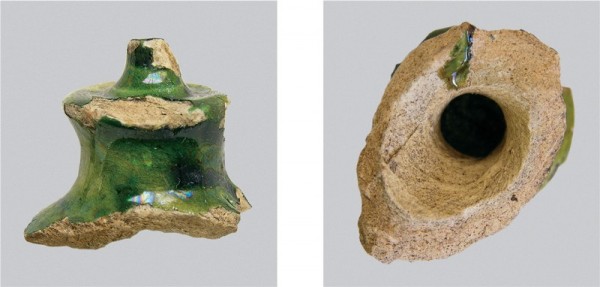

Money box, Surrey/Sussex, England, 1560–1620. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This shows the enigmatic hole in the shoulder of the green-glazed Border Ware money box. The lower side of the body has been restored.

Money boxes from London’s old Guildhall Museum Collection. Left: miter-shaped, probably from Cheam, Surrey, England, late medieval, lead-glazed earthenware; center, right: green-glazed Border Ware, Surrey/Sussex, England, 1560–1620. H. of money box on right 3 15/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Money box, probably Cheam, Surrey, England, ca. 1500. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) The coin slot of this miter-shaped money box measured 1 1/4 x 1/16" before it was widened.

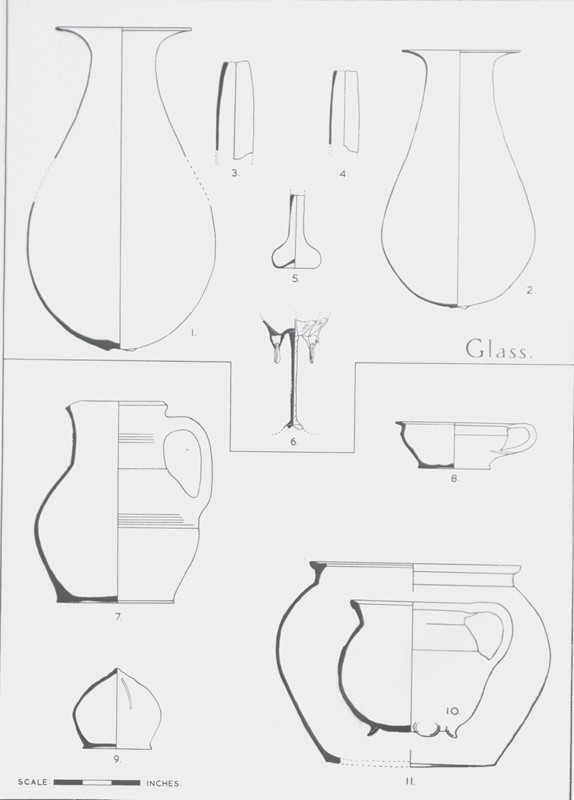

Drawing of a Border Ware pitcher and miter-shaped money box found in a closely datable London refuse pit, 1480–1510. (Courtesy, Guildhall Museum Collection; artwork by Ivor Noël Hume.)

Money box, Farnborough, Hampshire, England, 1565–1580. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Guildford Museum; photo, Jacqui Pearce.) This Border Ware money box is a waster found in a kiln flue (No. 3) on the Farnborough Hill site.

Button-knopped reproduction money box showing its documented method of suspension.

The shaft of an Elizabethan pin snuggly fits the mystery hole on the money box illustrated in fig. 2.

Piercing the hole into the wet clay and cutting the coin slot when leather hard.

Fired fragments show the different impacts of piercing the wet clay and cutting the slot at the leather-hard stage.

Lead-glazed knop fragment from The Theatre, Shoreditch (1576–1598), site reveals glaze bleeding through the concealed pinhole. (© Museum of London Archaeology; photo, Tim Braybrooke.)

Turning the button knop and trimming the base before drying.

One method of opening the (reproduction) box.

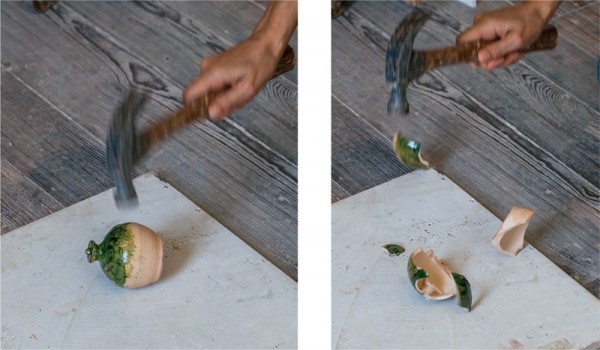

The hammer crew.

Unfired reproductions show concave (left) and flat (right) bases.

The white arrow points to the scar on the period money box, which provided a clue to the method of kiln stacking.

Tiny lumps on the base of the period money box showed that it had stood on top of another, separated by a trivet-style stilt.

Money box, Donyatt, Somersetshire, England, 1828. Slipware. H. 4", slot length 1 1/2", slot width 3/16". Inscription: E B R / May 21 / 1828. (Courtesy, Jacqui Pearce.) This pin-pierced Donyatt sgraffito slipware money box is the earliest dated example yet recorded from that Somersetshire factory.

Pinhole revealed on the interior of the ca. 1800 brown stoneware money box illustrated in fig. 27.

Money box, London, England, ca. 1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Alan Tabor, Robert Woolley Ceramics & Works of Art.)

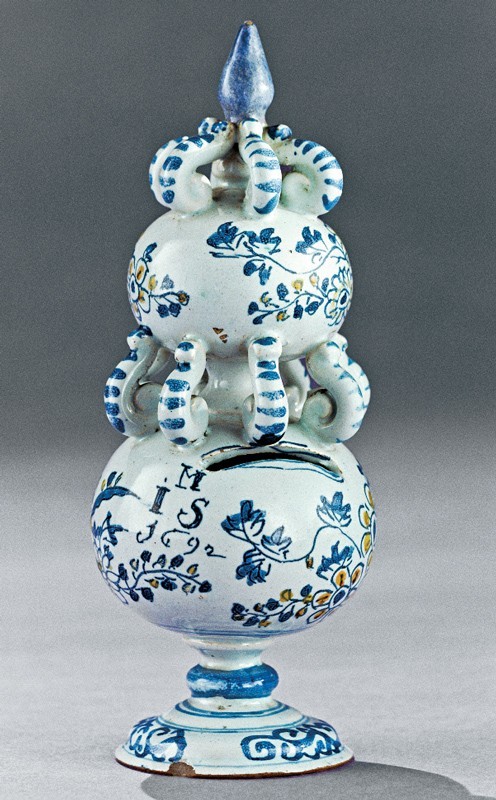

Money box, London, England, 1692. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

Money box, Donyatt, England, 1905. Slipware. H. 6"; slot 1 3/4 x 1/4". Sgraffito inscription: “Ralph Coles / Xmas / 1905.” (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.)

Money box, northern Netherlands, 1600s–1700s. Lead-glazed and white-slipped redware. H. 3 1/2"; slot 1 1/2", width damaged. (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This pedestal-based money box has been restored.

Money box, Normandy, France, 1600s. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/8"; slot 1 1/4 x 1/8". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This button-knopped, green-glazed, white-bodied money box has a pedestaled foot and vertical coin slot. It is believed to be Norman French in the English style.

Testing coin receptivity of the money box illustrated in fig. 2 shows that its slot will accept neither a 1607 James I shilling nor a 1566 Elizabethan sixpence.

An undated Elizabethan silver penny is of the size that the money box illustrated in fig. 2 will accept, which was the price of admission to The Rose, where most of London’s boxes were found.

Money boxes, Derbyshire, England, 1800s. Brown stoneware. Left: H. 6 1/4"; slot 1 3/4 x 1/4"; right: H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) The slots of these examples were made to receive George III twopences (left) and pennies (right), which were issued only at the Soho mint in 1797.

The 1806 return to numismatic normalcy inspired a century and more of turned and molded but nonpinholed money boxes. H. of Staffordshire dog 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.)

EDITOR’S NOTE This study of early money boxes is the product of three individuals, each approaching an obscure subject from different directions: the potter, the collector, and the museum ceramics specialist (fig. 1). Michelle Erickson, the internationally respected potter, put her contribution into clay rather than on paper. Ivor Noël Hume, the collector, and Jacqui Pearce, ceramics specialist with the Museum of London Archaeology, put theirs in writing, albeit in entirely different styles. One might argue that as a collaborative work of scholarship the texts should blend seamlessly into a single entity, which was certainly possible. The authors agreed, however, that beyond money boxes this contribution demonstrates how different elements of ceramic research can come together. The apparent superficiality of collecting had posed questions that opened the door to scholarly research of enduring value.

The thrill of research at any level is that we never know where it will end. Who, for example would have thought that examining a pinhole in a pot could lead to a nut-cracking, apple-chewing audience in London’s Elizabethan theatre The Rose?

SO WHY THE HOLE? My wife and I had been collecting money boxes for about thirty years before I asked that question and came up with the wrong answer (fig. 2). It became, however, the genesis of this study, and converted the old adage “it takes one to know one” into “it takes one to throw one.”

In England, ceramic containers for saved coins have long been known as “money boxes” or “Christmas boxes,” whereas in America they are called “piggy banks.” The latter term is included in Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary but, surprisingly, cites its first use as 1941, far later than one might have supposed. Equally surprising (at least to an Englishman) is the American dictionary’s omission of the term “money box.” Perhaps in retaliation, the Oxford English Dictionary includes no “piggy bank.” It does note that in northern England in the mid-sixteenth century a pig could be a small earthen pot, but fails to associate it with money.

What may be the earliest bank shaped like a pig was in the collection of London’s Guildhall Museum (now Museum of London) and cataloged as “in the form of a Sussex pig, reddish glaze with yellow patches, imperfect, XVII cent., perhaps made at Rye.”[1] However, a standard British ceramics encyclopedia attributes the beginning of Rye pottery making to the late eighteenth century, but adds that in such factories jugs were made in the form of a pig.[2] It seems, however, that this pig is more than likely a red herring and dates from the nineteenth century.[3]

There is, however, contributing evidence from Amsterdam, where two green-glazed earthenware money boxes in pig form have been found in contexts attributed to 1550–1575 and 1650–1675.[4] Nevertheless, I am leaving English pigs in their sty and focusing, instead, on globular clay banks or boxes. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, they were known as long ago as 1585 and described as “A box for money; especially a closed box into which coin is dropped through a slit.” But was that a pottery box? It could have been describing another type, mentioned in a Tudor chronicle, which recorded in 1538 that “the boxes that they have to gather the devotions of the people were taken away first.”[5] Those were being removed from religious houses at the time of the Reformation and almost certainly were made of wood.

There are, of course, numerous kinds of boxes, from iron nave boxes on the hubs of wheels to prestigious cubicles in theaters, but as a rule one thinks of boxes being cardboard or, in previous generations, wood. Alms boxes, poor boxes, and ballot boxes were all of wood and their contents received through a narrow slot and carefully locked. In short, they had nothing to do with pottery banks, whose contents were far less secure. A ceramic money box in the collection of London’s old Guildhall Museum was cataloged as being “of green glazed ware with slit on shoulder; fractured beneath to extract the money. XVth century.” Another of allegedly similar date was described as “red and yellow glaze in the form of a toad (?).” The catalog entry having been penned prior to 1908, there is no assurance that the frog was not a poorly rendered pig.[6]

One has to remember that early museum catalog dating was based on curatorial guesswork, there having been no money-box fragments recovered from sealed archeological contexts. Those that are intact were dug up by London construction workers who had learned that “old stuff” taken to the museum could be worth a beer. Thus, each acquisition has had to speak only for itself and not for the unrecorded context in which it was found. Those shown in figure 3 are typical of the type, but serve to illustrate that they came in sizes large and small.

In Britain, the first day after Christmas has long been known as Boxing Day, but few of us now remember or care that it relates to the tradition of masters giving money in pottery boxes to their apprentices—hence the variant term Christmas box. In 1615 a man of the cloth wrote, “It is a shame for a rich Christian to be like a Christmas-box, that receives all, and nothing can be got out until it is broken in pieces.”[7] Clearly, therefore, the box was not of wood but of smashable pottery. But why, one might ask, were Christmas gifts of money not openly handed out to employees with a smile and an assurance of a year well spent?

One of the common traits of apprentices was a lack of politeness or gratitude. While they would look with ill-concealed scorn at a handful of farthings, the same coins bestowed in a clay box deferred the expletives until it was broken and the miserly master unmasked. In 1642 essayist Humphrey Browne wrote of such a master that he “doth exceed in receiving, but is very deficient in giving; like the Christmas earthen boxes of apprentices, apt to take in money, but he restores none until he be broken like a potter’s vessel into many shares.” Another essayist had a similar thought: “Like a swine, he never doth good till his death: as an apprentice’s box of earth, apt he is to take all, but to restore none till hee be broken.”[8] Doubtless, it was a fortuitous choice of words that likened the miser to a pig.

In 1714 the eccentric historian John Aubrey noted the discovery of a Roman pot containing silver coins (denarii) and declared that “it resembles in appearance an apprentice’s earthen Christmas-box.”[9] It is true that pigs (wild boar) frequently appeared on red, molded Roman pottery, but there is no evidence that their potters made clay pigs or that any known type of Roman pot looked like the kinds of earthen Christmas boxes known to Aubrey. He was born in 1626 and would have been most familiar with round pots, green or yellow glazed, tapering to a disc on top and having a narrow slot in one side.

Though no two are exactly alike, the button-knopped form became common in London during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Unfortunately the Guildhall Museum’s catalog illustrated only one example and was lackadaisical in its descriptions of others, for example Number 400, which is described as “buff ware, ordinary type; XVI century.” However, the cataloger did think it worth mentioning that the box had been found in 1897 while building the Central London Railway’s Bank Station. That was a reference to the Bank of England, which could well be described as the British nation’s ultimate piggy bank.[10]

It is assumed that all the button-knopped money boxes unearthed in London were made in southeastern English kilns along the borders of Surrey and Hampshire counties. Known today as “Border Wares,” the industry was in production by the mid-sixteenth century, as Jacqui Pearce discusses in her essay in this volume. The oldest example in my collection (fig. 4) was attributed by a previous collector to a date in the sixteenth century. How his (or her) dating was arrived at has not been ascertained. The type is likened to a bishop’s miter and is said to have its origins in the thirteenth century. The shape is spheroid, rising to a point, with a vertically aligned coin slot in one side, barely one millimeter in width. As is true of many of the early surviving boxes, the slot had been roughly widened to extract the contents. The box’s yellow lead glaze dappled with copper is undeniably akin to that of jugs made at Cheam in Surrey in the second half of the fifteenth century. However, looking like is no more authoritative than descriptions in the old Guildhall Museum catalog. Not having access to any archeological ceramic groups from the fifteenth century, it seemed as though I would have to leave the bishop’s box undocumented—until along came one of those coincidences to be found in bad novels.

In May 2013 I received a request from Ian Blair at the Museum of London to remember a Roman wall I had excavated in the city sixty-three years earlier. My memory being what it has become, I had to dig out a booklet on the Roman remains that I had written in 1950. For no apparent reason I turned to its closing paragraph and found this summery of later finds: “One such pit, dating from the late fifteenth century, yielded cooking pots, jugs, and a pottery money box. With them were the bones of two large dogs, three cats, and three mice.”[11] This could be the evidence I needed, but I could not recall the pit. I knew I had excavated it before I had established a numerical system of recording, and I knew that the Guildhall Museum where I worked had long since been absorbed into the new Museum of London, meaning that in all likelihood those long-ago discoveries had been scattered and their evidence lost. But I was wrong again. In my files of 1950s negatives, I found a page of my drawings of that pit group along with a note attributing it to circa 1480–1510 (fig. 5).

The long-forgotten group included a rare German wine-glass stem and two glass urinals.[12] I suspect that there is food there for another bad novel that puts the money box amid dead dogs, cats, and mice, but this is not the place to pursue it.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the pointed top of the miter-shaped boxes had been replaced by a decorative button with a central nipple (fig. 6). A primary source for the new style was found to be the kilns of Farnborough in Hampshire, where the whiteware date range proved to be 1550–1580. The cracked waster excavated from one of the kiln flues has a knop typical of the form. As in most Elizabethan country potting, however, style changes had a practical purpose. In his The Collector’s Book of English Country Pottery, Peter Brears quotes a reference of 1585 that described a “mony box made of potters clay, wherein boyes put their money to keepe, such as they hang in shops etc., towards Christmas.”[13] That explains the need for the collared finial, but does not confirm that the boxes were given to the apprentices only on Boxing Day. Instead, it would appear that they were given earlier, to be suspended in stores, perhaps by the boys themselves, and in locations where customers could be talked into a donation (fig. 7).

The button knop, therefore, allowed a cord to be tied around it just as string-rims secured corks around the necks of glass wine bottles. The button is a small detail but one with significant social implications, as it pointed to the treatment and status of apprentice boys in the reign of Elizabeth I. The shape’s demise also heralded the apparent end of the box-breaking tradition, indicative, perhaps, of a yet-to-be-explained societal change—perhaps prompted by the rise of Puritanism that took the fun out of boys’ Christmas. Be that as it may, it was not the finial that intrigued this collector, it was that tiny hole (fig. 8).

About the diameter of a Tudor pin, it pierced the shoulder of the collection’s box (see fig. 2). A study of similar boxes published in archeological reports yielded no parallels. A quick check with Jacqui Pearce caused her to reply that she had never seen pinholes in money pots—which was not surprising, as I had owned my example for decades without noticing the hole. A few days later Jacqui reported that she had subsequently located six pinholed examples in the Museum of London collection, all similarly green-glazed, all of approximately the same dates, and all from the same potting area of southeast English counties. The hole, therefore, was not a “one off” anomaly. But what was its purpose?

Knowing that pots shrink about ten percent between throwing and firing, I deduced that the narrow coin slot might close up during the shrinking and that a spacer had to be inserted into the slot to keep it open; but having done that, air could not escape from the ball unless there was a vent—hence the pinhole.[14]

Michelle Erickson, a highly skilled practitioner of reproductive historical ceramic techniques, agreed to go back to square one and reproduce Tudor money boxes with and without pinholes. Her preliminary conclusion was that I was wrong about the slit closing but half right about the vent.

Michelle Erickson’s early experiments showed that when first thrown, the wet clay ball contains moisture that has to be released during the drying process, requiring the tiny vent. The coin slot cannot be cut until the box is in its leather-hard, prefiring condition—by which time the pinhole served no further purpose (fig. 9). In some cases the pinhole was left open, being in no way detrimental to the box’s appearance; in others, potters would smear the hole shut before glazing, causing it to disappear. The same production sequence would be applied to any air-sealed vessel, but when ready for firing the hole’s prior presence would be visible only on the inside (fig. 10). The illustrated fragment shows a London example whose green glaze had sealed the outside but had run through the pinhole into the interior (fig. 11).

To demonstrate that there was a time difference between the pinholing and the slitting, it was necessary to make a good copy of the box and then break it in order to study the inside. A tiny ridge around the hole showed that the clay was still wet when the pin had pushed it aside and thus had not punctured it cleanly. In contrast to the softness of the pinhole edges, with the box in its leather-hard stage the cutting of the slot neatly removed the displaced clay, leaving a sharp ridge alongside the interior of the cut. Although the powder disappeared, in some instances displaced clay fragments remained loose inside the boxes.

Pursuit of the enigmatic pinhole led Michelle to study other details, such as the way in which the coin slot was cut, and with what. It was slightly wider at the bottom than at the top, and the left side had a rough exterior edge while the right was smooth and slightly depressed. She found that it took a single slash with a knife from a right-handed potter to reproduce it. She also found that the button knop, which has sometimes been described as molded, was, in fact, reproducible by a skilled finger and thumb (fig. 12). We may not have discovered what the Elizabethan potter was thinking when he threw the little box, but we had learned how he did it!

Although a prodding pin may have been the genesis of this study, like the opening of any door, surprises can be waiting on the other side. We had not realized that globular Tudor money boxes preferred to bounce rather than break. After one of Michelle’s reproductions was thrice thrown down onto a stone slab without breaking, it took a hammer to do the job (fig. 13). Here was graphic evidence that when a customer’s ordering instruction was to make a product that could be broken (or not), the thickness (or rather the thinness) of the wall had to be a determining factor. One learned, too, that when smashing money boxes with a hammer, protective goggles are a wise investment (fig. 14).

In her contribution to this study, Jacqui Pearce notes that some Tudor boxes exhibit “concentric or fan-shaped marks” on their flat bases caused by the wire employed to cut them from the wheel. However, our pin-pierced example has a gently domed bottom rather than a flat base.

Michelle’s explanation goes like this: Open-mouthed vessels would not trap air inside them when being thrown, but money-boxes shaped without pinholes or coin slots would become clay balloons from which the air could not vent. As the clay shrank during the drying process, the volume of trapped air remained the same, and thus could thrust a flat base into becoming convex and unstable. To address that potential problem, some of Michelle’s boxes were thrown atop a shallow dome and so emerged from the wheel with concave bottoms—or, as apprentices would have said, “Bottoms up!” (fig. 15).

Michelle notes that her first attempts to make air-sealed boxes did cause the bases to bulge, and that the tendency was countered by the mound. However, she is clear that the reasoning associated with the reproduction boxes does not imply any connection with open-mouthed vessels that have similarly concave bases.

Although we have established that the pinhole was an intentional step in our box’s manufacture, another visible feature was not. A small vertical scar atop the glaze on one shoulder said that the box had abutted against something else while in the kiln. As the scar did not extend to the box’s girth, its neighbor could not have been a jar or other straight-sided vessel. I suggested, therefore, that the companion pot had to have had a projecting spout or handle that touched the wall of the money box. Again I was wrong.

In her experiments Michelle had made several trial boxes and was able to show convincingly that when a second tier was set in the kiln, an inverted box sat precisely where the scar had been (fig. 16). However, the scar appears not to have been caused by the abutting box but by a small clay spacer placed between them.

Further support for the kiln-stacking interpretation comes from the base of our tell-tale box. On it are scars left by its contact with a triangular clay spacer used to separate it from the inverted base of the box in the stack’s previous layer (fig. 17). The evidence is saying, therefore, that our original box was not a single item popped into the kiln to fill up space. Instead, it was showing that the potter had fired several at a time, and might even have thrown enough to fill a small kiln.

That raises an entirely different question: How many potters were involved? The wide variations among both the knop finials and base widths suggest that there had been almost as many potters involved as there are surviving examples. With that said, one has to add that there is no proof of the numbers made at any one establishment or their dates of manufacture.

One thing is certain, however. The pinhole technique was not an anomaly limited to one potter, to one factory, or to one century. Jacqui Pearce owns a money box with the telltale hole that she had never previously asked to explain itself (fig. 18). Her box is dated May 21, 1828, and carried the pinholing forward across two centuries. By that time, money boxes were no longer for smashing. In consequence, the majority of survivors had their contents carefully extracted and so provided no opportunity to study their interiors. The exception illustrated in figure 19 had been subjected to the smash-and-grab technique that revealed the pinhole inside yet remained invisible on the exterior. Its companion (see fig. 27), which dates to about 1800, may have been made at the same Derbyshire stoneware factory, its pinhole showing externally as a hitherto unrecognized dark dot. Thus, as Michelle Erickson has demonstrated, when air is trapped in a sealed space, no matter what the date, it has to be vented.

Jacqui’s box, though globular in shape, was personalized in sgraffito style but clearly was not to be smashed on Boxing Day.[15] So when did that practice cease? I suggested earlier that the rise of the Puritan ethic and the virtues of frugality may have been a factor, as might the upheavals of the English Civil War (1642–1651). Jacqui’s archeological timeline (see p. 161, fig. 2, in this volume) would seem to support that conclusion, but so, too, does the scarcity of documentary references.

A Christmas carol published in 1653 carried the line “Our kitchen-boy hath broke his boxe,” and a caption for an earlier woodcut (1634) reads, “Both with the Christmas boxe may well comply; It nothing yields till broke; they till they dye.”[16] It is clear, therefore, that the practice of using breakable ceramic boxes continued until the mid-seventeenth century. However, it seems equally clear that boxes for breaking had been the virtual monopoly of the Border Ware potters. Boxes for saving, on the other hand, were intended for a better-quality market and seem to have been made to be sufficiently attractive to discourage owners with hammers. Two London delftware examples are known, the earlier from circa 1650, manganese stippled, and piled high with destruction-defying scrolls and curlicues (fig. 20). An even more elaborate testimony to the Southwark delftware potters is in the Colonial Williamsburg collection, helpfully dated 1692 (fig. 21). The dearth of other such examples prompted curator John Austin to note, “The rarity of money boxes may be explained by the fact that it was necessary to break them to retrieve the coins.”[17] It can be argued, however, that the “break me” and “keep me” boxes had no evolutionary relationship one to the other.

By the later years of the seventeenth century, the concept of bestowing minimal largesse concealed in pottery boxes had run its course. However, the Christmas gift itself, stripped of its pottery packaging, survived to be described as “formerly the bounty of well-disposed people.” By the nineteenth century it had become entrenched much as, in our time, executives expect an end-of-year bonus regardless of whether they deserve it. By the 1850s one of the hitherto well-disposed people complained, “The gift is now almost demanded as a right, and our journeymen, apprentices, &c. are grown so polite, that instead of reserving their Christmas for its original use, their ready cash serves them only for pocket money; and instead of visiting their friends and relations, they commence the fine gentlemen of the week.”[18]

It is evident, therefore, that the Christmas box was no longer a clay ball or pig needing to be cracked open, but a metaphor for a hand-out passed with minimal merriment from palm to palm. Christmas of 1773 at Nomini Hall in Virginia found tutor Philip Fithian carefully recording the gifts handed out to his master’s servants.[19] In the morning Fithian had received his clean clothes “sent in with a message for a Christmas Box, as they call it; I sent the poor Slave a Bit, & my thanks.” A bit, Fithian explained, was a “pisterene bisected, or an English sixpence, and passes here for seven pence Halfpenny.”[20] He added that the total of his Christmas donations to the servants amounted to five bits, or three shillings, one penny, and a halfpenny.[21]

Accepting a bisected Spanish silver pistole as a bit, the poor slave would not have received enough to rattle a ceramic money box. It is clear, however, that Fithian’s limited largesse was not presented in a box, either wooden or ceramic. He ascribed the Christmas box term to some formless “they,” and evidently was content to pursue neither their identity nor their box any further. Not so author and publisher John Dunton, who in the early eighteenth century posed the question in his weekly periodical, the Athenian Mercury. “From whence comes the custom of gathering of Christmas-box money?” he asked. “And how long since?”

Dunton’s answer was convoluted and quaint, as one might expect from a man whose mind was compared by contemporaries to “a table where the victuals were ill-sorted and worst dressed.”[22] “It is as ancient as the word mass,” he wrote, “which the Romish priests invented from the Latin word mitto, to send, by putting the people in mind to send gifts, offerings, oblations; to have masses said for everything almost, that no ship goes out to the Indies, but the priests have a box in that ship, under the protection of some saint.” What that had to do with Christmas boxes is not entirely clear.

After further discourse Dunton came to the point, namely that the “box” referred to the money box given to servants to enable them to pay the priests for masses. Dunton explained to his readers that “a priest will not say a mass or anything to the poor for nothing; so charitable they generally are.”[23] It is scarcely necessary to add that Dunton’s family were Presbyterians.

Scottish folklorist and publisher Robert Chambers took up the quest in 1862, dismissing Dunton’s explanation as “an ingenious conjecture.” The Boxing Day gift giving was not to be ascribed to the Roman Catholic clergy, he said, but dated back to the Roman feast of Saturnalia, which included a ritual of exchanging New Year’s gifts. Contradicting Dunton, Chambers declared that the early Christian church denounced it on the grounds of its pagan origin. He added that regardless of clerical admonitions Christmas giving continued and grew into a “universally recognized institution.” Being a frugal Scotsman, Chambers complained that “This custom of Christmas-boxes, or the bestowing of certain expected gratuities at the Christmas season, was formerly, and even yet to a certain extent continues to be, a great nuisance.”[24]

Here again, as with Fithian in Virginia, the deed is emphasized, not its packaging. In spite of the fact that Boxing Day continues to be marked on the calendars of many English-speaking people, the day of gifting can be at any time from Christmas Day to New Year’s Day. In the Victorian era, however, when social distinctions separated master from man, the family exchanged its large gifts on the 25th and gave its little ones to the servants on Boxing Day. That is not to say that gifts of ceramic money boxes had been abandoned. Some were made for specific people and inscribed as being intended for the festive Yuletide occasion. This continued into the twentieth century, as a Donyatt hen-and-chickens example marked “Ralph Coles / Xmas / 1905” testifies (fig. 22).

The Coles “box” is not shaped like a pig but rather as a pedestaled ball surrounded by chickens and topped by a sitting hen. It was made in the previously cited Somerset village of Donyatt, whose potting industry had continued through six hundred years. The applied techniques had changed through the generations, but the known Donyatt money boxes are all of a pink-bodied ware coated with white slip spattered with copper oxide and incised in sgraffito style with names, initials, and dates, all under a yellowing lead glaze.

Jacqui Pearce’s globular example of 1828 is the earliest known, and the incised chicken on one side might be symbolic of a “nest egg,” a description in use by 1700 as “a sum of money put by as a reserve or serving as the nucleus of a fund.”[25] Although there is no assurance that the money-box decorator had that in mind, the three-dimensional hen-and-chickens design was established at Donyatt by 1836. Another, like the much later Coles box, is dated 1893 and incised “Wishing Edith / A merry Xmas.”[26]

Money-box collecting, like any other antique-hunting pursuit, has pitfalls larger than pinholes. Twentieth-century copies of nineteenth-century originals are common, but so, too, are genuine early examples imported from Europe masquerading as English. Large-scale construction projects in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Delft as well as others in Belgium have yielded quantities of late-medieval and sixteenth-century earthenwares found in wells and cesspits that have survived more or less intact.

An example, a cross between the miter style and the button-knopped English boxes, was excavated at Utrecht and attributed to 1450–1500.[27] Like the Cheam-style box, this has a narrow vertical slot, a detail not found on later Dutch money boxes. It would seem, therefore, that European and English money-box potters shared the same evolutionary trends.[28]

The Dutch export trade in restored ceramics recovered from construction sites is extensive. Once cleaned and repaired, they beguile novice collectors from the shelves of British antique shops. Worse, they regularly turn up on eBay, where one must take the seller’s (no returns please!) word for what one is buying. I should add that the Dutch are extremely versatile with plaster and paint, as was found with the box in figure 23, bought on eBay. The small, pedestal-based, thick redware box, coated with lead glaze dappled with yellowish clay slip, rises to a point. Unlike earlier examples, the slot is lateral and has evidently been widened to extract the contents. Taken at face value, such a pot might pass for Metropolitan (Essex) slipware of the late seventeenth century, though careful (if belated) examination shows that it had been broken apart at its girth and skillfully restored. A shape parallel for it has been found in Amsterdam and attributed to circa 1675–1700.[29]

Another money box in the Noël Hume Collection bears no resemblance to the Dutch slipware and is thought to be French (fig. 24). With olive-green glaze over white-slipped buffware, its form resembles the English Tudor types but, instead of having a sharply defined disc-and-nipple knop, the top of this one lacks sharp contours, resulting in a more clumsy profile that does not safely lend itself to suspension. Nevertheless, the coin slot is vertical and, though shorter than the English example, could readily receive the French copper double tournois of the first half of the seventeenth century.[30]

The slot length on Tudor button-knopped boxes might be misleading. On the box illustrated in figure 2, it is too short to take a silver shilling (unless heavily clipped) and too narrow to take a sixpence. The inference, therefore, is that in spite of the slot’s length it could only accommodate coins of very low denomination, such as an Elizabethan penny (fig. 25). However, as Jacqui Pearce reminds us, most of the archeologically discovered boxes came from The Rose theatre (1587–1606), where the standing-room-only crowd could get in for a penny (fig. 26).

The diameter and thickness of coins in relation to the length and breadth of slots can be clues to dating boxes. Thus the thinness of Elizabethan and Stuart silver dramatically contrasts with the heavy copper pence briefly issued by Birmingham’s Soho mint in 1797 (fig. 27). Made with penny and twopenny slots, it is likely that these stoneware boxes came into use because the unwieldly coins were better stored than spent. Not until 1806, when George III’s new copper coinage was issued, did the sizes again become manageable. That seems to have coincided with a new age of money-box manufacturing that ranged from Staffordshire dogs’ heads to old men, funny faces, and Victorian villas that cried “Keep me!” rather than “Break me!”

But that is another story (fig. 28).

Catalogue of the Collection of London Antiquities in the Guildhall Museum, 2nd ed. (London: Corporation of the City of London, 1908), p. 208, no. 557.

Wolf Mankowitz and Reginald G. Haggar, The Concise Encyclopedia of English Pottery and Porcelain (1957; repr. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1968), p. 214.

Contrary evidence is suggested by a pig-like bank recorded from the northern Netherlands, but as it closely resembles others attributed to ca. 1875–1900, I am prompted to dismiss it. E. M. Ch. F. Klijn, Loodglazuuraardewerk in Nederland (Lead-glazed Earthenware in The Netherlands) (Arnhem: Nederlands Openluchtmuseum, 1995), p. 281, top.

Jerzy Gawronski, Amsterdam Ceramics: A City’s History and an Archaeological Ceramics Catalogue, 1175–2011 (Amsterdam: Lubberhuizen, 2012), p. 173, no. 339 (thought to be German), and p. 235, no. 701 (attributed to the western Netherlands).

Charles Wriothesley, A Chronicle of England during the Reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559, edited by William Douglas Hamilton, 2 vols. ([Westminster]: Printed for the Camden Society, 1875–1877), 1: 75.

Catalogue of the . . . Guildhall Museum, p. 189, no. 201.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Christmas-box,” 1612–1615, Joseph Hall, Contemplations on the New Testament, pp. iv, xi.

John Brand, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, 3 vols. (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849), 1: 495.

Catalogue of the . . . Guildhall Museum.

Ibid., p. 198, no. 400.

Noël Hume, Discoveries on Walbrook, 1949–50 (London: Guildhall Museum, 1950), n.p.

Erwin Baumgartner and Ingeborg Krueger, Phönix aus Sand und Asche: Glas des Mittelalters, exh. cat. (Munich: Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1988), p. 249, no. 257, where it is attributed to the fourteenth century.

Peter C. D. Brears, The Collector’s Book of English Country Pottery (Newton Abbot, North Pomfret, Vt.: David & Charles, 1974), p. 56.

Jacqui Pearce cites a waster from a pottery site at Kingston upon Thames that did just that. Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire: Excavations at Farnborough Hill Convent 1968–72 ([Guildford, Eng.]: MoLAS/Guildford Borough Council, 2007), pp. 64–72.

The inscription suggests a christening rather than a birthday, and was made before the exact date was set.

Brand, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, pp. 489, 494. Information about his source can be found online at www.gutenberg.org/files/19979/19979-h/19979-h.htm.

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), p. 288, no. 719.

Brand, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, p. 494.

Philip Fithian, Journal and Letters of Philip Vickers Fithian, 1773–1774, edited by Hunter Dickinson Farish, new ed. (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 1957), p. 40 (entry for December 25, 1773).

A pisterene is described in the Oxford English Dictionary as a small coin used in America and the West Indies; 1774 is cited as the earliest recorded date of its use. Fithian’s references were at least a week earlier.

In 1777 there was no English penny, requiring it to be created from halfpennies.

Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities, 2 vols. (1862–64; repr. Detroit: Omnigraphics, 1990), 1: 626.

John Dunton (1659–1733) published the Athenian Gazette, renamed the Athenian Mercury, from 1691 to 1697.

Ibid.

Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest edition describing false eggs to promote laying, dates from 1606.

Richard Coleman-Smith and T. Pearson, Excavations in the Donyatt Potteries (Chichester: Phillimore, 1988), pp. 273–75. A similar hen-and-chicken box in my collection is in blue-dotted gray stoneware and inscribed “WALTER JAMES MASON 1877”.

Klijn, Loodglazuuraardewerk in Nederland, p. 282.

Slip-decorated money boxes in elongated pig forms were being made in the northern Netherlands in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Ibid., p. 281.

Gawronski, Amsterdam Ceramics, p. 234, no. 700 (buff body, yellow lead-glazed).

Joe Cribb, Barrie Cook, and Ian Carradice, The Coin Atlas: The World of Coins from Its Origins to the Present Day (New York: Facts on File, 1990), p. 38, nos. 26, 27.