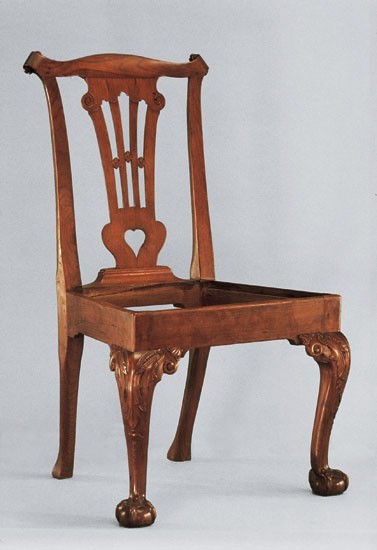

Robert Walker, side chair, King George County, Virginia, 1746. Mahogany with beech. H. 38 7/8", W. 21 3/8", D. 17 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the Rappahannock River valley in John Henry, cartographer, Thomas Jefferys, engraver, A New and Accurate Map of Virginia, Wherein most of the Counties are laid down from Actual Surveys (London, 1770). Engraving and watercolor on paper. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.) This map highlights and identifies the sites associated with Robert and William Walker.

1. Beverley–Blandfield

2. Brent–Richland

3. Carter–Cleve

4. Carter–Nomini Hall

5. Carter–Sabine Hall

6. Fitzhugh–Bedford

7. Fitzhugh–Boscobel

8. Fitzhugh–Eagle’s Nest

9. Fitzhugh, Lewis-Marmion

10. Jett–Walnut Hill

11. Lee–Stratford Hall

12. Lee–Bellview

13. Mercer–Marlborough

14. Spotswood–Newpost

15. Tayloe–Mt. Airy

16. Thornton–Fall Hill

17. Turner–Walsingham

18. Washington–Ferry Farm

19. Washington–Wakefield

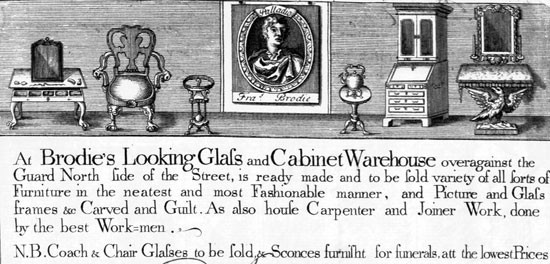

Billhead used by Francis Brodie, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1739. Engraving on paper. (By permission of the trustees of the Goodwood Collection.)

Armchair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1735–1745. Walnut. H. 40", W. 25". (National Art Galleries, XVII and XVIII Century American Furniture, New York, December 3–5, 1931, lot 483.)

Detail of the carved crest and splat on the armchair illustrated in fig. 5.

Corner chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1755. Walnut with beech. H. 34", W. 23", D. 26". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the carving on the front leg of the corner chair illustrated in fig. 7.

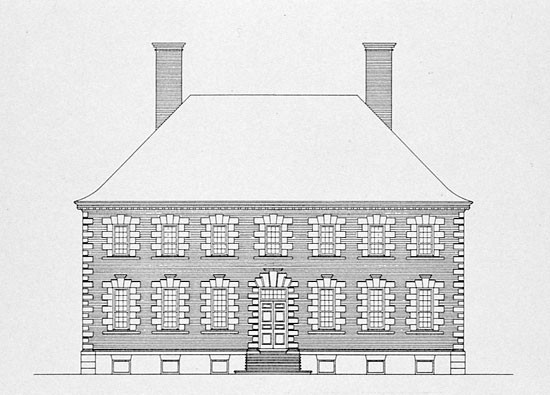

Christ Church, Lancaster County, Virginia, 1728–1735. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

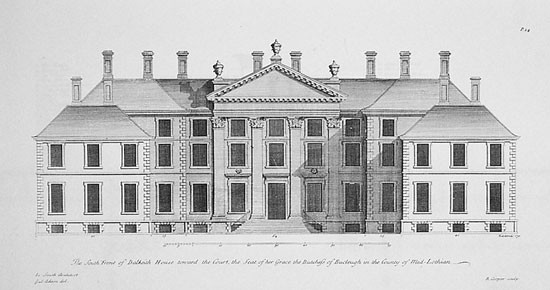

Dalkeith Palace, Midlothian, Scotland, 1702–1711. (Country Life, October 7, 1911).

Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia, ca. 1740. (Courtesy, Stratford Hall Plantation, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association, Stratford, Virginia; photo, James R. Dunlop.)

Kinross House, Kinross-shire, Scotland, 1685–1693. (Country Life, July 13, 1912).

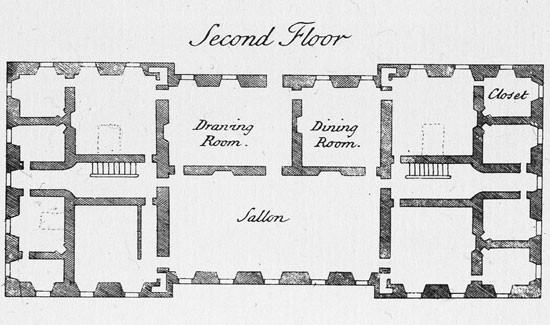

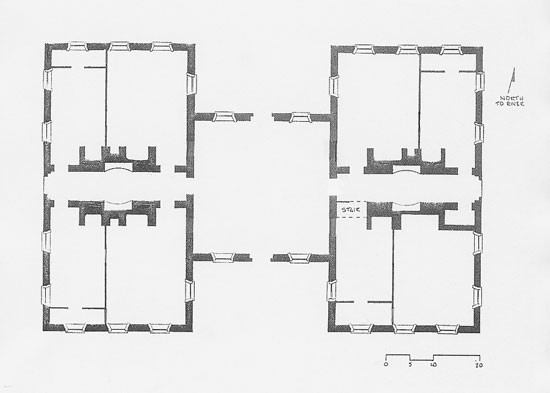

Second-floor plan of Kinross House illustrated on pl. 61 of William Adam, Vitruvius Scoticus (1812).

Second-floor plan of Stratford Hall. (Courtesy, Stratford Hall Plantation, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association, Stratford, Virginia.)

Tea table attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1740–1750. Mahogany. H. 28 3/4", Diam. of top: 32 13/16". (Stratford Hall Plantation, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association, Stratford, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pillar and legs of the tea table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1755. Woods and dimensions unrecorded. (Edward Wenham, The Collector’s Guide to Furniture Design [New York: Collectors Press, 1928], p. 216.) The top is virtually identical to that on the Lee family table illustrated in fig. 15. The guilloche-and-flower motif between the legs of the table shown in fig. 17 is common in eighteenth-century architecture, but less so in furniture of the period.

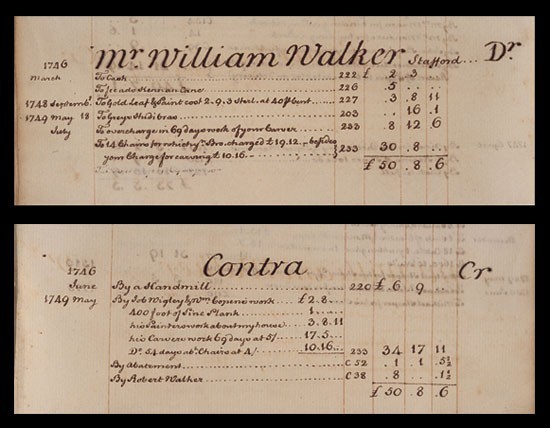

Account of William Walker with John Mercer, John Mercer Account Book, 1741–1750, fol. 36. (Courtesy, Mercer Museum, Bucks County Historical Society.) This account records the May 1749 charges for carving the Mercer-Walker chair illustrated in fig. 19 and Mercer’s subsequent sale of the set of fourteen chairs back to William Walker in July 1749.

Robert Walker, armchair, King George County, Virginia, 1749. Mahogany. H. 38 1/2", W. 28 1/2", D. 18". (Courtesy, Mary Washington House, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail of the back of the chair illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chair illustrated in fig. 19, showing the attachment of the gadrooned molding and (missing) knee blocks. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chair illustrated in fig. 19, showing the undercut gadrooned molding. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chair illustrated in fig. 19, showing the attachment of the arms to the stiles. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chair illustrated in fig. 19, showing the attachment of the arms to the side rails. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail of the left arm terminal of the chair illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1755. Walnut with oak and yellow pine. H. 37 7/8", W. 22 3/4", D. 20 3/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

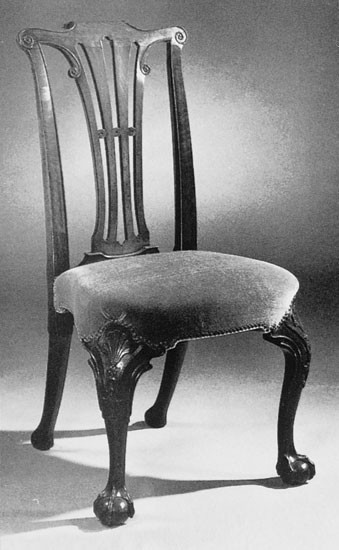

Patrick Strahan, side chair, London, 1735–1740. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (Christopher Gilbert, Pictorial Dictionary of Marked London Furniture, 1740–1840 [Leeds: Furniture History Society, 1996], p. 442.) Like many of the chairs documented and attributed to Robert Walker, this example has a scroll in the center of the crest rail, three lobate piercings in the splat, rounded and molded rear legs, shell and bellflower carving on the knees, and compressed claw-and-ball feet with prominent rear talons.

Cleve, King George County, Virginia, ca. 1740–1747

Detail of Dalkeith Palace illustrated on pl. 24 in William Adam, Vitruvius Scoticus (1812).

Armchair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1750. Cherry with beech. H. 39 5/16", W. 24 5/8", D. 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Shirley Plantation, Charles City County, Virginia; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 31.

Tea table attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Mahogany and cherry. H. 28 1/2", Diam. of top 30". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, gift of Mr. and Mrs. John T. Warmath in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Worsham Dew; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the carving on the pillar and legs of the tea table illustrated in fig. 33.

Detail of the top of the tea table illustrated in fig. 33.

Kettle stand attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Mahogany. H. 31 3/4", Diam. of top: 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the legs of the stand illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Like the tea table illustrated in fig. 33, this example originally had knee carving featuring a broad, flat leaf scrolling up and turning over where the top of each leg joins the pillar.

Detail of the top of the stand illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Easy chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1755. Mahogany with beech. H. 46", W. 32", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This is the only American easy chair with cabriole rear legs that end in claw-and-ball feet.

Side chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Walnut with beech. H. 39", W. 22 5/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 40. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. H. 39 3/4", W. 24", D. 21". Mahogany. (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The crest rail and splat were replaced in the nineteenth century.

Detail of the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 42. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Walnut. H. 37 1/4", W. 22 5/16", D. 17 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Hans Lorenz.) Like other seating attributed to Walker’s shop, this chair has laminated triangular glue blocks at the corners of the seat frame, a splat with beveled rear edges and piercings related to those on earlier seating in the group, an arched rear rail that is integral with the shoe, and arms that are attached to the side rails with a coped joint and four screws and joined to the rear stiles with an exposed dovetail reinforced with a screw. The chair originally had a slip seat, but it was replaced with plank boards during the nineteenth century.

Side chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1760–1775. Walnut with beech. H. 37 1/2", W. 22 5/8", D. 17". (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two chairs from this set are at Mount Vernon and two are at Kenmore.

Side chair attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1760–1775. Walnut with beech. H. 37 1/2", W. 22 1/2", D. 17". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.) This chair retains its original leather covering and linen under upholstery.

Clothespress attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 84 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The feet are incorrect replacements.

Detail of the interior of the press illustrated in fig. 47.

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1750–1760. Yellow pine; remnants of original blue paint under later blue paint. H. 91 1/2", W. 48 5/8", D. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk-and bookcase illustrated in fig. 49. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

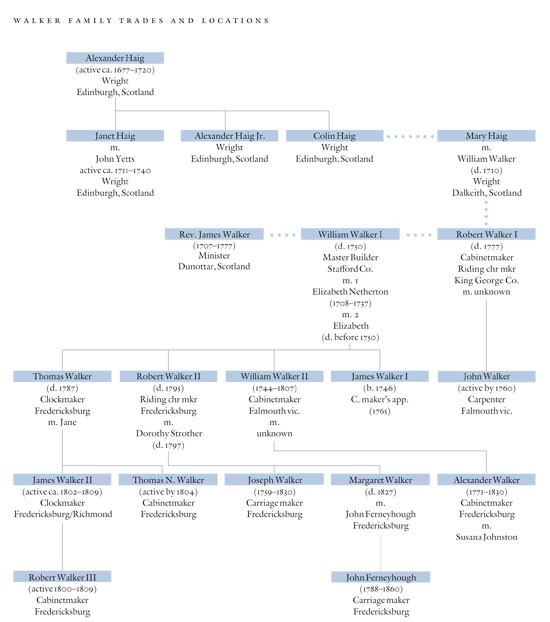

Chart of Walker family members and their respective trades, illustrating four generations of furniture-related artisans in the Rappahannock River valley and their likely Scottish ancestry.

“The Thomas Lord Fairfax Chairs” attributed to William Walker Jr., Stafford County, Virginia, 1771–1772. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Samuel T. Freeman, Executor’s Sale, Antique and Modern Furniture, Collected by the Late George W. Childs, Philadelphia, November 20–23, 1928, lot 291.)

Robert Cockburn, side chair, Orange County, Virginia, 1773. Walnut. H. 34", W. 20 1/4", D. 17". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum, gift of Mrs. Whitfield Cobb.) The crests and splats of Madison’s chairs identify them as products of the Walker shop tradition, and their construction features separate shoes and rear rails—a trait differentiating William Jr.’s work from that of his uncle.

Detail of the back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 53.

In the 1720s English pamphleteer and novelist Daniel Defoe (1660–1731) commented on the rising tide of Scottish migration to Britain’s North American colonies. Fearing for Virginia in particular, he noted, “if it goes on for many years more, Virginia may be rather called a Scots than an English plantation.” At the time of Defoe’s writing, the crown’s highest-ranking offical in the colony was Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood (1676–1740), a Scotsman descended from an illustrious line of lairds and bishops who had been active in seventeenth-century Scottish affairs. Similarly, the rector of Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, the founder and first president of the College of William and Mary, and the commissary (delegate) of the bishop of London to Virginia was James Blair (1656–1743), a clergyman born in Crombie, Scotland, and educated at the universities in Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Together, Blair and Spotswood stood at the apex of a wide and diverse network of Scots in Virginia. By 1790 Caledonians and their progeny constituted at least 10 percent of the overall population.While the Scots have been long recognized for their contributions to Virginia’s economic, political, and religious history, new research pertaining to Robert Walker (ca. 1710–1777), a Scottish-born cabinetmaker in King George County, Virginia, and his brother William (ca. 1705–1750), a joiner turned architect and master builder, sheds light on the profound Scottish influence on America’s eighteenth-century decorative arts.[1]

Nearly all of the furniture formerly attributed to Williamsburg cabinetmaker Peter Scott (ca. 1695–1775) is actually the work of Robert Walker (figs. 1, 2). In his groundbreaking book, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790, Wallace Gusler used shared construction techniques, design elements, and materials to demonstrate that many of Virginia’s most elaborate examples of eighteenth-century furniture were the product of a single cabinet shop and a skilled carver. Earlier scholars had considered much of this furniture British. In Furniture of Our Forefathers (1922), Esther Singleton described a chair in the group as possibly “by Thomas Chippendale.” In many ways, the research presented in this article does not change Gusler’s analysis of the identifying characteristics of this furniture group; rather, it strengthens it by providing a more particular historical and cultural context and identifying the Scottish origins of these features.[2]

Scottish migration to Virginia began in the seventeenth century, but on remarkably unfriendly terms. Although England and Scotland shared a common monarchy, they remained separate countries. Because Virginia was a decidedly English colony, few Scots went there willingly. Many of Virginia’s early Scottish settlers were convicts, banished to the colonies as part of their punishment. The passengers aboard the ship Phoenix of Leith, owned by Edinburgh merchant Robert Learmonth, may have been typical. Bound for Virginia in 1666, its human cargo included Charles Davidson and James Ogilvy, described as “vagabonds and thiefes,” and Katherine Laird, “a thief and whore.” Other Scottish settlers had been prisoners of war ensnared by the civil and religious conflicts that roiled Scotland throughout the seventeenth century and racked the nation’s economy. Most were indentured servants in search of better economic conditions who exchanged several years of labor for food, clothing, shelter, and free passage to North America.[3]

In 1707 Parliament passed the Act of Union that forged England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales into the United Kingdom of Great Britain, and Scots began to arrive in the colonies on somewhat friendlier terms. Cementing the role of Presbyterianism as the offical Scottish religion, the Act of Union left many of Scotland’s Anglican clergymen in a desperate search for parishes. Virginia opened its door. As early as 1697 Reverend Nicholas Moreau complained to English bishops that Virginia’s clergy was “composed for the most part of Scotchmen.” He disparaged the colony’s Scottish-born priests as “people so basely educated, and as little acquainted with the excellency of their charge and duty, that their lives and conversation are fitter to make heathens than Christians.” But with James Blair firmly ensconced as the bishop of London’s commissary, the Virginia church proved a safe harbor for Scottish Episcopalians.[4]

The Act of Union also opened Virginia’s tobacco market to Scottish merchants who were eager to capitalize on the new environment. They moved quickly to establish stores in all of the colony’s major port towns—Norfolk, Petersburg, Richmond, Fredericksburg, Port Royal, Yorktown, and Alexandria—trading consumer goods for tobacco, particularly with small planters. With stores came a small army of Scottish-born factors and clerks, many of whom settled permanently in Virginia and, through marriage and business deals, formed lasting alliances with the local planter families.[5]

As a group, these Scottish settlers were frequently distrusted and viewed by the English in Virginia as “uncouth, self-seeking, secret Presbyterians.” Reverend Jonathan Boucher (1738–1804), an English-born tutor in the household of Captain Edward Dixon (ca. 1702–1799) of Port Royal, illustrated the anti-Scots prejudice when he wrote:

Captain Dixon’s house was much resorted to, but chiefly by the toddy drinking company. Port Royal was inhabited by factors from Scotland and their dependents. . . . There was not a literary man, for aught I could find . . . nor were literary attainments, beyond mere reading and writing, at all in vogue or repute.

Despite Boucher’s disdain, thousands of Scots came to Virginia, and many were successful. In 1729 Roderick Gordon, a physician from Banff, Scotland, who lived in King and Queen County, Virginia, wrote home to his brother, “Pity it is that thousands of my countrymen should stay starving at home, when they can live here in peace and plenty.” By the 1720s Scotsmen filled important posts in the colonial government, manned stores in the major port towns, and delivered sermons from the local pulpits with a decidedly Scottish brogue. It was in this receptive environment that the Walkers began their American careers. Indeed, William Walker’s own parson, Reverend David Stuart (ca. 1690–1749) of St. Paul’s Parish in Stafford County, Virginia, was a Scotsman from Inverness-shire.[6]

William Walker was in Virginia by at least 1730; Robert arrived by 1743, and perhaps much earlier. Their Scottish background is highlighted by an unusual advertisement placed by “friends” in the Virginia Gazette on July 13, 1775:

If one Robert Walker, a native of Scotland, who resided in Toeks, in the parish of Dunotter, In that country, until the time of his departure for this colony, which, as nearly as his friends can recollect was 44 or 45 years ago, and, by the only accounting they received concerning him, lives on the Rappahannock river, be still living, he may, by applying to the printer of this paper, hear of something greatly to his advantage.

The subscribers added: “if he [Robert Walker] is dead, or has removed out of the colony, it is most humbly requested of any person acquainted therewith to make known every material particular concerning him . . . and whether he left any legitimate children, how many, and their respective places of residence and vocations.” This advertisement suggests that Robert was entitled to some sort of inheritance, possibly from Reverend James Walker (1707–1772), recently deceased rector of Dunottar Parish. For nearly forty-five years, the brothers had enjoyed the patronage of a wealthy clientele that stretched from Westmoreland to Spotsylvania counties on both sides of the Rappahannock (fig. 3). Soon after their arrival, Robert became northern Virginia’s cabinetmaker of choice and William the region’s leading builder.[7]

The Walkers’ immigration coincided with Scotland’s emergence as a fountainhead of the late baroque style. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries Scottish architects Sir William Bruce (ca. 1630–1710) and James Smith (ca. 1645–1731) ushered in the northern kingdom’s appreciation for classical taste, sweeping away the nobility’s and gentry’s desire for castellated tower houses built for defense as much as for beauty and replacing it with admiration for academically inspired houses based on Italian Renaissance designs. By the second quarter of the eighteenth century, Scottish architects had entered the vanguard of Great Britain’s artistic circles. Scottish-born expatriates James Gibbs (1682–1754) and Colen Campbell (1676–1729) moved to London and became leading lights of the neo-Palladian movement. Through the publication of their pattern books, they spread the gospel of design inspired by Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). In Campbell’s introduction to his major, three-volume work, Vitruvius Britannicus, or the British Architect, he paid tribute to the source of his inspiration:

We must in Justice, acknowledge very great Obligations to those Restorers of Architecture, which the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centurys produced in Italy. . . . But above all, the great Palladio, who has exceeded all that were gone before him, and surpass’d his Contemporaries, whose ingenious Labours will eclipse many, and rival most of the Ancients. And indeed, this excellent Architect seems to have arrived to a Ne plus ultra of his Art.

By placing Palladio on a pedestal and capitalizing on the “ne plus ultra” of his designs, Campbell and Gibbs garnered patronage from the British nobility and disseminated the neo-Palladian style throughout Great Britain and her colonies.[8]

These architectural changes fostered new concepts for furniture deemed appropriate for Palladian-style houses. During the early eighteenth century furniture designers and architects looked to Italy for inspiration and crafted a style that featured zoomorphic figures—eagles, lions, dolphins—drawn heavily from classical and Italian Renaissance furniture. Englishman William Kent (d. 1748) is frequently considered the best exemplar of this design movement, but in Scotland, Edinburgh cabinetmakers Francis Brodie (active 1725–1779) and Alexander Peter (active 1728–1764) were its chief practitioners. At his cabinet shop, appropriately called Palladio’s Head, Brodie produced furniture in the latest neo-Palladian taste. His engraved billhead featured a bust of the Italian architect adapted from Giacomo Leoni’s The Architecture of A. Palladio (1715) (fig. 4) and copied by Colen Campbell for his own Andrea Palladio’s First Book of Architecture (1728). Featuring a dressing table with cabriole legs and claw-and-ball feet and a pier table with an eagle support, the billhead advertised Brodie’s expensive, high-style wares. Most important for the subject of this article, the billhead included an armchair with a solid, vase-shaped splat, cabriole legs with shell carving on the knees, claw-and-ball feet, and eagle-head arm terminals. Brodie was not, however, the sole purveyor of fashionable baroque furniture in Edinburgh. Peter produced similar chairs that he described to customers as having “a clam shell carved in the knee” and “Carved feet with Lyons Claw.”[9]

This was the Scottish environment from which the Walkers emerged, and the timing of their arrival in Virginia was particularly auspicious. The second quarter of the eighteenth century witnessed a significant building boom in Virginia as the wealth generated by tobacco and trade spurred a desire for new dwellings and public buildings that reflected the colony’s rising status. With buildings came the need for new furniture, the more up-to-date the better. Imbued with experience in both the architectural and furniture trades, the Walker brothers constituted a unique partnership. As missionaries of the Scottish late baroque style, William offered houses with many of the stylistic features of Bruce’s and Smith’s buildings while Robert provided furniture that resembled Brodie’s and Alexander Peter’s fashionable wares. In hindsight we can see that the Walkers came at an opportune moment, rose into the top ranks of the colony’s artisans, and can be substantially credited with bringing to Virginia the Scottish late baroque version of their respective arts.

The earliest chair attributed to Robert Walker’s shop bears an uncanny resemblance to the armchair illustrated in Brodie’s billhead. Regrettably, the current location of the Walker armchair is not known, but it was photographed and advertised for sale in New York City in 1931 (figs. 5, 6). According to the auction catalogue, the chair had belonged to “Mr. Fenton Fitzhugh, a member of the Fitzhugh family of ‘Marmion’ and Fairfax Co., Virginia.” Actually, Fenton Mercer Fitzhugh (1818–1890) was a descendant of Captain Henry Fitzhugh (1687–1758) of Bedford Plantation in King George County, one of the Walkers’ closest known associates. Fitzhugh’s son-in-law Reverend Robert Rose (1704–1751), one of Virginia’s Scottish-born clergymen, recorded many of the personal interactions that transpired between the two families. In his diary on September 8, 1747, Rose noted that he “Breakfasted at Mr. [William] Walker’s with Col. [Henry] Fitzhugh who agreed to give me Cash for one of Mr. Spotswood’s Bonds £500—and returned to Capt. [Henry] Fitzhugh’s,” and on October 31, 1749, he recorded that he “went with Robert Walker to Capt. Henry Fitzhugh’s.”[10]

Described as an “Important Walnut Arm Chair” of American manufacture, the Fitzhugh family example has cabriole legs with scrolled feet and shells on the knees, a vase-shaped splat with carved acanthus leaves, a shoe with a gadrooned molding, leaves on the crest and stiles, and a crest, arms, and knee blocks decorated with eagle heads. As will be seen, the eagle-head arm terminals are precursors to dog-head variants associated with Walker’s most elaborate seating.

The Fitzhugh armchair shares several features with an early corner chair attributed to Robert Walker (figs. 7, 8). Both objects have vase-shaped splats, and the front leg of the corner chair has a small shell and bellflower surrounded by acanthus leaves that appear to be by the same carver responsible for those on the back of the Fitzhugh chair. Most of the acanthus carving associated with Walker’s shop has similar overlapping elements and major leaves with long, hooked tips (figs. 6, 8). Instead of scrolled feet, the front leg of the corner chair terminates with a compressed claw-and-ball foot with a notched rear talon, a feature associated with other seating attributed to Walker. The slip seat frame of the corner chair is made of beech, a wood commonly found in Scottish furniture, used extensively by Walker, and readily available in the Rappahannock River valley. The corner chair descended in the family of Thomas Fitzhugh (1725–1768) of Boscobel Plantation in Stafford County, then passed into the Ficklen family of neighboring Belmont Plantation. Thomas’s father was Captain Henry Fitzhugh of Bedford, who may have been the original owner of the armchair (fig. 5).

The Walkers and the Fitzhughs were connected through patronage and family. Captain Henry Fitzhugh was a close relative of William Walker’s first wife, Elizabeth Netherton (1708–1737). William Walker first appears in Virginia records in 1730, when he repaired a “Scrutore” for Stafford County lawyer John Mercer (1705–1768) in exchange for legal services. Charging each other one pound, Walker repaired Mercer’s furniture while Mercer represented Walker in a legal matter against “Carter.” Mercer’s ledger book records an incident recalled many years later by Landon Carter (1713–1778), son of Robert “King” Carter (1663–1732) of Corotoman Plantation in Lancaster County, the colony’s largest landholder and a member of the Governor’s Council. In the settlement of a land dispute, Landon Carter deposed that circa 1730 he and his brother Robert Jr. (1704–1732) had journeyed to Stafford Courthouse to acknowledge a deed, and while they were there an argument occurred. According to Landon,

Robert Carter the younger, unfortunately had a quarril at the said Courthouse with one William Walker a Joyner and undertaker of buildings, which produced a battle, that gave the said Walker much uneasiness by a letter which he wrote to the deponent’s father, with much submission upon the occasion.

Although no other reference to this matter exists, the incident places William among the most influential families in Virginia very shortly after his arrival from Scotland.[11]

In the late 1720s and early 1730s “King” Carter was finalizing plans for the construction of Christ Church (fig. 9) near his plantation in Lancaster County. Robert Carter Jr. was equally involved with the completion of his late baroque, two-storey brick house, Nomini Hall, in Westmoreland County. Was William Walker involved with either the design or the construction of Christ Church or Nomini Hall? Did the Carters play a role in bringing him to Virginia? Unfortunately, there is no evidence to answer these queries, but within ten years William Walker was intricately involved with both the design and the construction of major baroque-style buildings throughout Virginia and patronized by such prominent families as the Carters, Lees, Mercers, and Fitzhughs.

Just one year after his dispute with Robert Carter Jr. and without any apparent harm to his reputation, William Walker cemented his relations with Virginia’s governing gentry. On November 23, 1731, William married Elizabeth Netherton, whose deceased father, Henry, was a “gentleman” and former surveyor for Westmoreland County. Through her mother’s aunt Sarah Tucker Fitzhugh, Elizabeth was related to one of northern Virginia’s most important and prolific families. Elizabeth’s cousins at the time of her marriage included the previously mentioned Captain Henry Fitzhugh of Bedford, who was a burgess for Stafford County; Major John Fitzhugh (d. 1733) of Marmion; and Colonel Henry Fitzhugh (1706–1742) of Eagle’s Nest, a burgess for Stafford County who was married to Robert “King” Carter’s daughter Lucy (1715–1763).[12]

The benefits to Walker were immediate. Having married into a politically connected family, he began to receive commissions for public buildings and other structures, particularly in northern Virginia. In 1740, with Landon Carter acting as his security, Walker agreed to build two “good and substantiall” bridges over Totoskey and Naylor’s Hole creeks, the waterways immediately adjacent to Landon’s newly completed mansion, Sabine Hall. In the minutes of the Richmond County Court, Walker is described as an “undertaker and Architeck,” one of the earliest known uses of the term “architect” in colonial Virginia. Four years later, with Henry Fitzhugh of Bedford as his security, Walker contracted with Westmoreland County for the design and construction of an even more substantial bridge over Maddox Creek, described as

A Good Strong bridge the arches to be Thirty foot Asunder and of Such height that flats or boats may pass without Masts Erect and Twelve foot Clear passage on Top, Railed on Each Side at least three foot high, also a sufficient Causeway from the End of the Said Bridge through the Said Marsh unto the Next firm Land.

From 1740 to 1750 William Walker consolidated his position as one of colonial Virginia’s leading builders of public works. In 1741 his commissions included a new brick steeple and a meeting room for the vestry of St. Peter’s Church in New Kent County. Indicative of his ongoing involvement with furniture production, Walker agreed to provide the vestry room with a table and three benches.[13]

Walker received his most prestigious commission in 1749, when he was selected to redesign and rebuild the recently burned capitol building in Williamsburg. On March 1 of that year, Scottish-born parson Robert Rose wrote that he had “returned to Mr. Walker’s who had got Home from Williamsburg where he had undertaken the Capitol for £2600.” Walker may have been ill at the time. Rose’s diary entries in February and March of the following year note that he “went to Overwharton Church where heard of Mr. William Walker’s death which will . . . delay building the Capitol” and attended “Mr. W. Walker’s Funeral who was buried with his wife in one grave.”[14]

In a hasty will witnessed by his brother Robert, William Walker provided for his children and attempted to settle his tumultuous business affairs:

Whereas I have many buildings now on hand, many workmen, many tools & many Materials for carrying on the same & many more I daily Expect from London & other parts of Great Britain, I give them all to my Executors with full power to Compact with other Workmen they whatsoever think proper toward finishing & compleating the same in as full & ample manner as I could do were I living & the profits to be divided among all my Children.

William’s slaves and indentured servants, his 465-acre plantation in St. Paul’s Parish, and the plantation he leased from Scottish-born Reverend John Moncure in Overwharton Parish were to be sold or held in trust by his executors for the benefit of his children.[15]

Described as “worthy friends,” William Walker’s executors included Nathaniel Harrison (1703–1781), Lucy Carter’s second husband; her brother Charles Carter (1707–1764) of Cleve; John Tayloe (1721–1787) of soon-to-be built Mount Airy; Thomas Lee (1690–1750) of Stratford Hall; and his eldest son, Philip Ludwell Lee (1727–1775). Walker had chosen from the colony’s most illustrious families, men from counties that stretched along both sides of the Rappahannock River and who were associated with some of the finest houses and furniture in eighteenth-century Virginia.[16]

Walker’s rise in Virginia society was nearly unprecedented. Within twenty years, he had gone from “Joyner and undertaker of buildings” to “architeck” to “gentleman” and “Major.” His probate inventory, compiled by three of his fellow justices—Philip Alexander, Richard Foote, and Henry Fitzhugh—listed twenty-one African American slaves and ten white indentured servants. His personal property included all the accoutrements appropriate for a man of his status: a library with works by Addison, Pope, and Swift; a teaboard; porcelain teacups and saucers; a set of fourteen carved chairs; a desk-and-bookcase; a tall case clock; a looking glass; silver teaspoons; and a silver pocket watch.[17]

William Walker’s training undoubtedly contributed to his success as an architect and builder in colonial Virginia. It is likely that he (b. ca. 1705) was the son of Mary Haig and William Walker (d. 1710) and began training with Edinburgh wright John Yetts (or Yates) on November 18, 1719. Assuming that his apprenticeship lasted the customary seven years, William would have been approximately twenty-five years old when he came to Virginia in 1730. Both Yetts and his father-in-law, Alexander Haig, were members of the Incorporation of Wrights and Masons and part of a significant clan of Scottish artisans. Alexander Haig Jr. and Colin Haig were also members of the incorporation, and Mary Haig Walker may have been their sister, making John Yetts the young William Walker’s uncle (fig. 51). The elder William Walker was a successful craftsman who attained the enviable position of “Joyner to her Grace the duchess of Buccleugh.” Anne Scott (1651–1732), duchess of Buccleuch, was a major benefactor of Scottish baroque architecture. In 1701 she engaged James Smith to design and build her palace at Dalkeith, considered one of the most ambitious baroque buildings in Scotland (fig. 10). Three years later, the duchess’s chamberlain contracted with William Walker for all the window sash, doors, and wainscoting needed for the new building at Dalkeith, and in December of that year the chamberlain and joiner traveled to London to meet with James Moore, the duchess’s cabinetmaker, and to conduct a survey of London staircases and furniture. Dying six years later, William Walker could not have trained any of his young children, but his reputation and connections would have given them entrée to Scotland’s early-eighteenth-century artisan community.[18]

Robert and William Walker’s experiences in Virginia underscore their training. The Incorporation of Wrights and Masons included both builders and cabinetmakers, and Scottish wrights were expected to be competent in both trades. In 1737 the incorporation selected John Yetts, William Walker’s probable uncle and master, to design and build a new classical façade for its old headquarters at St. Mary’s Chapel. Completed with a triangular gable with urn finials, a Palladian window, Doric pilasters, and a rusticated door surround, the building’s entrance sported details first seen in Scottish architecture through Sir William Bruce’s and James Smith’s designs and later echoed in many of William Walker’s Virginia buildings. Robert Walker’s training remains a mystery, but his and William’s collaboration as architects and furniture makers can be firmly established.[19]

Thomas Lee and Stratford Hall

By 1739 construction had begun on Stratford Hall (fig. 11), Thomas Lee’s new house overlooking the Potomac River in Westmoreland County. That year William Walker reported that two convicts trained as carpenters and joiners—Richard Kibble and Samuel Vlin—had run away from the work site and stolen a sailing vessel that belonged to Lee. Based on these connections, Walker is now considered the most likely candidate for architect and builder of Lee’s mansion.[20]

In appearance and floor plan, Stratford Hall differs from most contemporary Virginia houses of similar stature, but it has clear Scottish antecedents. Its H-plan resembles that of several late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century houses built in Scotland by Bruce and Smith. Bruce’s personal residence, Kinross House (figs. 12, 13), is considered one of the most influential buildings in classical Scottish architecture. Described by Scottish architectural historians as a “double-depth and corridor plan . . . confined to the sides: at the centre, a more formal and grandiose effect . . . achieved by channeling cross-communication through a . . . great, double-height Salon . . . with flanking bedroom suites,” Kinross House can be seen as a larger, and grander, ancestor of Stratford Hall. In designing Stratford Hall, Lee and Walker chose not to have a second floor and put the dining room and drawing room in one of the flanking cells (fig. 14). Otherwise, the two floor plans are remarkably similar.[21]

In light of William Walker’s involvement with Stratford Hall, it seems logical that one of the most elaborate and expensive pieces of furniture attributed to Robert Walker descended in Thomas Lee’s family. The tea table illustrated in figures 15 and 16 reputedly belonged to Lee’s son Thomas Ludwell Lee (1730–1778) of Bellview Plantation in Stafford County. The table descended in the family of his daughter Anne Fenton Lee and her husband, Daniel Carroll Brent (1759–1814) of Richland Plantation, also in Stafford County. Made of mahogany, the table is a tour de force of mid-eighteenth-century carving. Its scalloped top resembles contemporary silver salvers, including one owned by the nearby Carter family at Corotoman. The pillar has a plain column above a vase-shaped section enhanced with C-scrolls and leaves, and the base, or “claw” as it was called during the period, has an applied turned pendant. The carving on the legs of the Lee table is similar to that on the seating illustrated in figures 5–8, and the toes of the claw-and-ball feet were modeled like those on the Fitzhugh family corner chair (fig. 8).

The lower portion of the Lee table pillar has carved fish scales, or imbrocation—a motif commonly used on neo-Palladian bolection moldings and trusses for mantelpieces and door surrounds. Not surprisingly, architects like William Kent also specified imbrocated carving for furniture designed for their patrons’ homes. It is possible that architectural components in Stratford Hall had imbrocated details, but almost none of the interior woodwork from this period survives.

Edward Wenham illustrated a very similar tea table in his book The Collector’s Guide to Furniture Design (1928); however, the location of this object is not known (fig. 17). The scalloped top, claw-and-ball feet, and turned pendant are virtually identical to those on the Lee family example, and the knees have scrolling and overlapping leaves similar to those on other furniture attributed to Robert Walker’s shop. With its exceptionally complex acanthus and carved guilloche-and-flower motif between the legs, the Wenham table may have been more expensive than the Lee table and undoubtedly belonged to a patron of similar stature.[22]

John Mercer and Marlborough

John Mercer’s ledger books provide information on Robert and William Walker’s carver and identify many of the other artisans with whom they collaborated. As early as 1742 William’s attorney began amassing supplies for the construction of his new brick house at Marlborough, on the Potomac River in Stafford County. Over the next eight years Mercer hired many of Virginia’s most accomplished craftsmen: David Minitree (d. 1774) of James City County for brickwork; William Copein (active ca. 1740–1780) of Prince William County for stone masonry; William Walker for the interior finish; and Robert Walker for furniture. For the basic carpentry, Mercer contracted separately with William Monday (d. 1782) whose charges, to Mercer’s irritation, totaled £129.10 and were not “of near the value as by Major Walker’s Estimate . . . yet to avoid Disputes & as he is worth Nothing I give him Credit to make a full Ballance.” To complete the residence, Walker used his own painter, and his carver worked for sixty-nine days at a rate of five shillings per day for charges that totaled £17.5.[23]

As the house neared completion in 1749, Mercer commissioned a set of fourteen chairs from William Walker to be made by his brother Robert (fig. 18). Walker charged £19.12 (approximately £1.8 each) for the uncarved frames and an additional £10.16 for the carver’s work, which amounted to fifty-four days at four shillings per day. Mercer’s bill for the set of fourteen chairs totaled £30.8, or nearly £2.4 each, and the carving represented more than one-third of the cost. Although the carving is not described, it must have been either extensive or exceptionally demanding.[24]

Three months after purchasing the chairs, Mercer sold them back to William Walker for £30.8. Mercer’s ledger entry does not specify why he returned the chairs, nor does it explain why Walker accepted them at cost. The appraisers of Walker’s estate, probated in July 1763, described the set as “12 Carved chairs” and “2 Arm’d chairs.” Although none of the side chairs is known to have survived, the armchair illustrated in figure 19 is almost certainly one of the pair commissioned by Mercer. The chair descended in the family of William’s granddaughter Margaret Walker Ferneyhough, and it is clearly from the same shop that produced the armchair, corner chair, and tea tables illustrated in figures 5–8 and15–17.[25]

Because of its history and documentation, the Mercer-Walker armchair represents a benchmark for identifying furniture from Robert Walker’s shop. Structural details associated with Walker’s seating are distinctive.

• Crests with heavily scrolled ears.

• Splats with three lobate piercings over a heart-shaped piercing. The most expensive models have a lozenge-shaped ribbon interlaced within the vertical ribs.

• Splat edges beveled at a forty-five-degree angle at the rear (fig. 20).

• Rear rails that are arched and integral with the shoe (fig. 20).

• Knee blocks glued to the face of the seat rails. On the most expensive models gadrooned molding is attached in the same manner (fig. 21).

• The gadrooned molding is undercut at the bottom (fig. 22).

• Rail and leg joints reinforced with glue blocks, typically laminated and triangular in shape.

• Rounded rear legs that end in a square foot.

• Arms that are attached to the stiles with dovetails visible from the rear and reinforced with a screw (fig. 23). The arms are attached to the side rails with a coped joint and secured with four screws aligned two over two (fig. 24). The two upper screws are countersunk in the rabbet for the slip seat.

• The most elaborate armchairs typically have dog-head arm terminals (fig. 26).

Walker worked for nearly thirty years, but there is very little variation in the construction of his seating. He offered patrons a narrow range of forms and decorative options including cabriole legs with carved acanthus leaves, shells, and husks (figs. 2, 25); gadrooned moldings; knee blocks with leafage and scrolls; animal- and bird-head arm terminals; and claw-and-ball and scrolled feet. Most of these options came under the purview of Walker’s carver, whose working dates appear to be almost the same as his master’s. In fact, all of the carving associated with Walker’s shop appears to be by the same hand (figs. 8,16, 25, 32, 34).[26]

A side chair (fig. 1) made in 1746 for John Spotswood (1722–1758) of Newpost Plantation in Spotsylvania County is similar to the Mercer-Walker armchair but has simpler carving. The chair’s date of manufacture is confirmed by a lawsuit that Spotswood filed against Walker in 1756. The plaintiff maintained that Walker owed him £5.11.15 for “divers goods and iron wares” purchased between 1748 and 1750. Walker countered “that in the year 1746 one Mr. Elliott Benger who was one of the executors of the late Alexander Spotswood, Esqr., bought of the defendant twelve chairs which by account under Benger’s hand he says were for the plaintiff.” Although Spotswood did not deny commissioning the chairs, he argued that he was “an infant under the age of 21 years” in 1746 and therefore not liable. The court ruled in Spotswood’s favor, requiring Walker to pay the entire £5.11.15 despite an outstanding balance for the set of twelve chairs. Ironically, Spotswood died shortly after winning his suit, and his probate inventory lists “12 Chairs” valued at £24 “In the best Room” of his house. These chairs were only slightly less expensive than those commissioned by Mercer three years earlier.[27]

The side chair illustrated in figure 27 is closely related to the seating from the Spotswood and Mercer-Walker sets. All of these objects share details with a side chair made by Patrick Strahan, a London cabinetmaker of Caledonian extraction whose clientele seems to have been primarily Scottish (fig. 28), including the Scottish dukes of Montrose and Gordon. Between 1737 and 1741 Gordon patronized Francis Brodie of Edinburgh and Strahan simultaneously. While there is no known link between Walker and either Strahan or Brodie, the seating documented and attributed to these men suggest that they trained in similar Scottish furniture-making traditions.[28]

In 1734 a Scottish chair maker named Robert Walker made “6 elm chairs” for George Burnett (1714–1780) of Kemnay in southern Aberdeenshire, not far from Dunottar. Regrettably, Burnett’s household accounts neither describe the chairs nor give their price, but in all likelihood this Robert Walker was the émigré who came to Virginia and specialized in making chairs.[29]

Robert Walker established his shop in Virginia by 1743. In that year the King George County Court prosecuted a thief named William Jones for stealing “sundry Joiner’s Tools” from Walker. William Monday, the carpenter who would later work at John Mercer’s house, was a witness. Also in 1743 Walker leased property from Thomas Turner (d. 1758) of Walsingham Plantation, a prominent landowner, justice of the court, and burgess for King George County. From 1743 to 1752 Walker paid Turner rent in the amount of £7.10, frequently settling his debts with “Smith’s” and “Joyner’s Work” instead of cash. Finally, in 1743 Walker expanded his labor force and took as an apprentice Spence Monroe (d. 1774), the recently orphaned son of a prominent Westmoreland County family. Walker agreed to train Monroe and the young man’s slave in the “trade of a Joyner” and to provide Monroe with “a suit of good Devonshire . . . Two Check Shirts & Two pair Trousers . . . Shoes & Stockings Every year with Sufficient good meat, Drink, Washing and Lodging.” The slave was to receive “warm Sufficient Cloathing & Victuals” and work “in no other Business than in the way of sd. Trade and Shop.” Only under “Emmergent Occasions” could the slave spend “a Day or two at Planting or gathering Corn.” Due to Monroe’s social status, he was allowed “to Eat in Company with Walker or the Chief of his Journeymen.”[30]

Over the next thirty years, Robert Walker took at least three other apprentices—Abraham Farrow, Robert Bagge, and Richard Tankersley—and employed at least two indentured servants—Alexander Aaron and Alexander Scott. In 1745 Walker paid taxes for nine persons older than sixteen in his household; thus it is possible that his workforce included artisans yet to be identified. His accounts with a Port Royal store operated by Thomas Turner and Turner’s son-in-law Edward Dixon mentioned a housekeeper named Jenny Moore, which suggests that Walker was a widower. The cabinetmaker’s purchases included household supplies; a variety of cabinetmaking tools such as chisels, gouges, and plain irons; brass upholstery nails; and leather.[31]

One artisan associated with Walker had special status and may have been the “Chief” referred to in Monroe’s apprenticeship agreement. Alexander Cowley began charging goods to Robert Walker’s account with Turner and Dixon in 1744. Five years later, “Robert Walker of King George County, Joiner” leased one hundred acres on Gingoteague Creek to “Alexander Cowle . . . Joiner” for eight years. Walker received thirty-eight pounds and agreed to share with Cowley the cost of setting up a small house on the property, the price not to exceed eight pounds. In the deed, Walker reserved the “Liberty of cutting what Timber he may have occasion for his Shop’s use.” No other artisan allied with the Walkers is known to have received such personal treatment. Considering the dates of Cowley’s association with the Walkers, one wonders if the former might have arrived as an indentured servant, become a highly valued freeman and journeyman, and even been the unnamed carver who worked for both Robert and William.[32]

Charles Carter and Cleve

The Walker brothers’ most potentially important collaboration was Cleve, the two-storey brick mansion built for Charles Carter, on the north side of the Rappahannock River, just a few miles from Robert Walker’s cabinet shop (fig. 29). The son of Robert “King” Carter, Charles was a trustee for the towns of Port Royal and Falmouth and a burgess for King George County. Construction for the house probably began in the early 1740s. Seven years later, William Walker accepted a final payment of £200 for “building and finishing” Charles’s new house. Unlike Stratford Hall, Cleve’s floor plan resembles more typical Virginia houses with two rooms on each side of a large entrance hall. Yet Cleve’s exterior is unusually elaborate and has obvious Scottish precedents. In many ways, the façade resembles an elongated version (with seven bays instead of three) of the side pavilions at Dalkeith Palace (figs. 10, 30). At Cleve, Walker used locally made brick instead of ashlar stone (the preferred Scottish building material) for the exterior walls and aquia stone (a creamy white sandstone that was plentiful in northern Virginia) for the quoins, doors, and windows.[33]

Not surprisingly, Carter patronized his architect’s brother for furnishings for his new home. Indeed, many of Robert Walker’s most interesting pieces descended in Charles’s family, particularly through the line of his daughter Mary Walker Carter (1736–1770) who married her cousin Charles Carter (1732–1806) of Corotoman and Shirley. In his 1762 will Charles Carter of Cleve appointed his son-in-law and namesake as one of his executors empowered “to sell and dispose of all supernumerary furniture, and Stocks of horses, Cattle, sheep, and swine, from time to time as they shall see occasion for the benefit of my estate.”[34]

A pair of cherry armchairs that descended in the family of Charles and Mary Carter may have been among the original furnishings of Cleve (figs. 31, 32). Her father’s probate inventory listed “2 arm’d chairs” valued at three pounds. Dating circa 1747, the chairs have heavily scrolled ears, dog-head arm terminals, compressed claw-and-ball feet with prominent rear talons, and splats similar to those on other seating documented and attributed to Robert Walker’s shop. The husks on the splats represent an additional option available on his most elaborate chairs. Although no side chairs from the Carter set are known, two other cherry side chairs have nearly identical carved details. These side chairs were donated to the Virginia Historical Society during the nineteenth century, but no history was given.[35]

The tea table illustrated in figure 33 is the most elaborate object with a Carter family provenance and attribution to Robert Walker. Probably made around the time of Mary Walker Carter’s marriage to Charles Carter in the mid-1750s, the table descended in the family of their daughter Mary Walker Carter (1764–1836) who, in 1781, married George Braxton (1762–1801) of Hybla Plantation in King William County. The table subsequently passed through several generations of Carter-Braxton descendants. Although clearly by the same turner and carver responsible for the Lee table (figs. 16, 34), the Carter example has a more elaborate scalloped top (fig. 35). The rim has eight repeats of leaf clusters flanked by C- and S-scrolls. The S-scrolls retain their outer volutes, which are missing on all other pillar-and-claw tea tables attributed to Robert Walker’s shop. As the Lee and Carter tables suggest, contemporary British salvers may have provided inspiration for Walker’s scalloped tops. A salver made by London silversmith John Swift in 1753/54, probably for a member of the Spotswood family, has a rim similar to that on the Carter table. The carving on the knees of the Carter table flows in two directions rather than simply cascading down the legs as on the Lee example (figs. 16, 34). On the former example, a broad flat leaf scrolls up and turns over where the top of each leg joins the pillar. The leg carving also reverses direction above the small C-scrolls on the side of each leg.[36]

A mahogany kettle stand that descended in the Semple family has carved decoration nearly identical to that on the Carter table (figs. 36-38). It was probably made in the mid-1750s, around the time that Reverend James Semple, a Scottish-born minister who later became rector to St. Peter’s Church in New Kent County, was a member of the Kilwinning Cross Masonic Lodge in Port Royal, just across the river from Robert Walker’s shop. As Scotsmen living in Virginia, Semple and Walker would have had much in common. One can easily imagine the two men reminiscing with the “toddy drinking company” at Captain Edward Dixon’s nearby.[37]

The histories, scale, and design of Walker’s pillar-and-claw forms suggest that the Carter table and the Semple stand are later than the Lee and Wenham tables. The carving on the former objects is also lighter and more open and may reflect Walker’s growing awareness of the rococo style. Similar changes can be observed in the ornament on seating furniture associated with his shop, but there is no evidence that this reflects the work of a second carver.

Robert Walker’s Other Patrons

Thomas Lee of Stratford Hall, John Mercer of Marlborough, and Charles Carter of Cleve represent three of Robert and William Walker’s best-known clients, three prominent men who engaged the brothers to design and build houses and to make furniture for themselves and other members of their families. Despite William’s death in 1750, Robert Walker’s career in furniture making continued. From the early 1750s until shortly before his death in 1777, Robert enjoyed steady patronage from many northern Virginia families—the Washingtons, Thorntons, and Jetts, to name only a few.

One of the rare examples of stuffed and upholstered furniture produced in colonial Virginia is an easy chair attributed to Walker and owned by Mary Ball Washington (ca. 1708–1789) (fig. 39). Since the chair is not listed in her husband’s probate inventory, Mary must have acquired it after 1743. The chair’s shell-and-husk knee carving relates most closely to that on the Spotswood family side chair, which was made in 1746 (figs. 1, 2). During Mary’s long years as a widow, her easy chair would have resided at Ferry Farm Plantation on the north side of the Rappahannock River, nearly opposite Fredericksburg. It is probably the “1 Easy Chair” included in the written memorandum of Mrs. Washington’s effects not specifically bequeathed in her will. Like the Lee and Carter tea tables, the easy chair also descended in a matrilineal line through the family of Mary’s daughter Betty Washington Lewis (1733–1797) of Kenmore Plantation.[38]

The Washington family may have been among Robert Walker’s best customers. George Washington’s half brother and Mary Ball Washington’s stepson, Augustine Washington (1720–1762) of Wakefield Plantation in Westmoreland County, was the likely owner of the side chair illustrated in figure 40. Oral tradition maintained that it came from Mount Vernon and belonged to a Mrs. Bushrod Washington around the time of the Civil War. Augustine’s grandson Bushrod Washington (1785–1831) and the latter’s wife Henrietta Spotswood (1786–1860) lived near Mount Vernon at Mount Eagle Plantation in Fairfax County.[39]

Typical of later seating from Walker’s shop, the crest on the Washington family side chair has rounded ears rather than scrolled ones. In contrast, the design of the knee carving is essentially the same as that on the Mercer-Walker armchair made in 1749 (figs. 19, 25, 40, 41). The only indication that the carving on the Washington chair is later is the asymmetrical termination of the acanthus at the bottom of the design. This leg carving is identical to that on an armchair fragment with a somewhat murky Washington family history (figs. 42, 43). The armchair is important in being one of two objects with paw feet attributed to Walker’s shop. Like the Washington side chair, it originally had gadrooned molding glued to the face of the front rail. Given the similarities in their knee carving and comparable use of applied molding, it is tempting to speculate that the chairs are from two sets commissioned by the same patron. If so, they might represent the “1 dozn. Walnut Chairs” and “1 Dozn. Mahogany Chairs & 2 Arm Do.” listed in Augustine Washington’s 1764 probate inventory.[40]

While Robert Walker is best known for carved chairs, they were not his sole production. In 1764 he charged Port Royal merchant Edward Dixon six pounds (twenty shillings per chair) for a set of twelve chairs. That was half the amount Walker charged Mercer for his set, which suggests that Dixon’s chairs were either simpler or not carved. It is possible that Walker’s carver was no longer active when Dixon commissioned his chairs, since most of the latter tradesman’s work appears to date from the mid-1740s to circa 1760.[41]

One of the latest carved chairs attributed to Walker’s shop entered the Meriwether family of Cloverfields Plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia, during the late nineteenth century (fig. 44). Its structural details, scrolled ears, and dog-head arm terminals are similar to those on Walker’s earlier chairs, but the crest is simpler and the undercarriage differs in having chamfered, Marlborough legs and rectangular stretchers. Although considerably less ornate than much of the seating associated with Walker, the Meriwether armchair represents an important link to several plain northern Virginia chairs that may represent offshoots of his shop tradition.[42]

The Thornton family of Fall Hill Plantation near Fredericksburg appears to have ordered two sets of chairs from Walker. Four chairs from one set survive (fig. 45), and the numbers cut into their seat rails indicate that there were originally a dozen. The crests have simple, rounded ears and the splats have interlaced strapwork above vertical ribs—a design popularly referred to by modern collectors as “owl pattern.” For later seating in the neat and plain style, Walker offered a variety of crest and splat options. Another side chair with a Thornton family provenance (fig. 46) has a splat like the example shown in figure 45 but retains the earlier crest style with scrolled ears. Like the previous Washington family chairs, the Thornton chairs’ provenance suggests they may have been commissioned simultaneously and designed with subtle differences for sets that would have been used in different rooms.

Even though chairs appear to have been the mainstay of Robert Walker’s business, his shop also produced case furniture. As is the case with Walker’s seating, his case work has distinctive construction features.

• The top and bottom boards of the case are joined to the sides with blind dovetails.

• Drawer dividers are half-dovetailed to the sides and covered with a vertical strip of wood glued to the front edge of the case.

• Vertical backboards are rabbeted to the sides and top and secured with nails.

• Dustboards are full depth and engage dadoes in the sides. The dustboards are thinner than the dadoes, and have long strips of wood glued to the ends to provide a tight fit. The grain of the strips runs perpendicular to the grain of the dustboards.

• Base and cornice moldings are glued to rectangular blocks on the bottoms and the tops of the cases.

• Cornices typically have dentil or wall-of-Troy molding separating an upper cyma molding from a deep cove below.

• Carved feet (claw-and-ball or hairy paw) are tenoned into large blocks nailed into the bottom of the lower case. Ogee feet have a primary wood face and a secondary wood core. The grain of the laminates is parallel. Stack-laminated glue blocks and flankers provide support for cases with ogee feet.

• Drawer bottoms are rabbeted at the front and sides and nailed in place. The front joint is reinforced with segmented glue blocks, and the side joints are reinforced with thin strips of wood that extend from front to back and are cut off at a forty-five-degree angle at the rear.

• Door stiles and rails are assembled with blind mortise-and-tenon joints. Some doors have panels with indented upper corners and small complimentary blocks glued into the upper corners. Panels are set into rabbets and secured with small strips of molding nailed along all four sides.

• Bookshelves are secured with ledger strips nailed to the sides of the case.

• Pigeonhole brackets and prospect doors frequently have Gothic arches.

Several desk-and-bookcases and presses attributed to Walker survive, but only one documentary reference to his production of case furniture is known. In 1760 he made a desk valued at £5.7.6 for Reverend Jonathan Boucher, the outspoken anti-Scottish bigot.[43]

Two linen presses and a clothespress made for Landon Carter’s son-in-law Robert Beverley (1740–1800) of Blandfield Plantation, on the south side of the Rappahannock River in Essex County, exhibit the telltale signs of Walker’s case construction. They are probably the “1 black walnut Press” and “1 press” valued at $12 each and “1 Wardrobe” listed at $30 in Beverley’s probate inventory. About 1760 Walker also made the clothespress illustrated in figure 47 for the Lewis family of Marmion Plantation. While the indented upper corners of the paneled doors are prototypical, it is the only known example of Walker’s casework without a dentil or wall-of-Troy molding applied to the cornice. The astragal-paneled prospect door with stop-fluted document drawers in the bottom shelf of the upper case is also distinctive (fig. 48). Other case pieces attributed to Walker’s shop include a mahogany press that descended in the Taylor-Galt family of Orange County, Virginia, and Williamsburg, and a walnut desk-and-bookcase that descended in the Carter-Lewis-Bassett family of King George, Spotsylvania, and Hanover counties.[44]

A desk-and-bookcase discovered in the early twentieth century near Leedstown, in present-day Westmoreland County on property that had once belonged to the Jett family, is one of the most distinctive case pieces attributed to Walker’s shop (fig. 49). Its astragal-panel doors resemble the prospect door on the interior of the Lewis family clothespress (fig. 48). The desk has compressed claw-and-ball feet identical to those on chairs from Walker’s shop, and the bookcase cornice has a fine dentil course separating the upper cyma from the large cove below. This architectonic composition may reflect Robert’s familiarity with the classical conventions employed by his brother William.

The upper section of the Jett desk-and-bookcase has an interior fallboard, twenty-four small drawers, and shelves flanked by pigeonholes above (fig. 50). Behind the doors of the lower section are openings for two missing drawers and twelve vertical compartments for bound ledgers or letter books. This interior arrangement suggests that the desk-and-bookcase was used in a counting room, perhaps that of merchant Thomas Jett (d. 1785) of King George and Westmoreland counties. In 1758 Robert Walker’s former landlord, Thomas Turner, appointed Jett to serve as one of the executors of his estate. Turner allowed the merchant “to live on . . . [his] Dwelling plantation” for ten years after his death and gave Jett “full liberty . . . [to use his] old store house.” If Jett acquired the desk-and-bookcase from Turner’s estate, that object might represent part of the nearly fifty pounds of “Joyners Work” that Walker gave Turner in lieu of cash for rent in 1744 and 1745.[45]

Robert Walker’s involvement with Thomas Jett continued for several decades. In 1774 Robert mortgaged to Jett a combination of livestock and household furniture in exchange for £111.17.4. The furniture listed in their agreement included three bedsteads, one chest, two cupboards, one square table, and eight chairs. Walker may have remained heavily indebted to Jett, for when Robert died intestate in 1777, the King George County Court appointed Jett one of his estate’s administrators.[46]

The Walker Family Influence

Robert and William Walker had a profound influence on northern Virginia decorative arts and architecture. Their associates and apprentices established their own businesses and, in all likelihood, produced objects similar to those from William’s and Robert’s shops. William had four children who practiced woodworking trades: Thomas (d. 1787), a clockmaker; Robert (d. 1795), a riding chair maker; William Jr. (1744–1807), a cabinetmaker; and James (b. 1746), a cabinetmaker’s apprentice. Robert’s son John worked as a house carpenter in Falmouth during the 1760s and early 1770s. The descendants of William and Robert Walker dominated the furniture trade in and around Fredericksburg for three generations (fig. 51). Indeed, William Sr.’s grandson Alexander Walker (1771–1830) was the most prominent cabinetmaker in that town in the early nineteenth century.[47]

At least two of Robert’s apprentices—Spence Monroe and Richard Tankersley—established their own shops and spent a significant portion of their time making chairs. When Tankersley died in 1764, his probate inventory listed unfinished wares including eighteen black walnut chair frames valued at eight shillings each, black walnut and pine plank, two turner’s lathes, three joiner’s benches, a black walnut table frame, and three sets of walnut table legs. Spence Monroe’s shop in Westmoreland County appears to have been of comparable size. In 1765 he took William Walker’s nineteen-year-old son James as an apprentice “to learn the trade of a joiner.” When he died only nine years later, Monroe’s probate inventory listed eighteen newly completed chair frames valued at five shillings each, “6 Back frames & 4 Pieces for the fore parts . . . 2 Dozen and 4 Black walnut Do. Not quite compleat,” and “leather for Chair Bottoms.” Judging from assigned values, the seating in Tankersley’s and Monroe’s inventories must have been much simpler than most of the chairs associated with Robert Walker.[48]

The best indication of Robert Walker’s influence comes from recent discoveries related to his nephew William. By 1763 William Walker Jr. had established his own cabinetmaking business in the Falmouth area and opened an account with Scottish merchant William Allason under the heading “Mr. William Walker, Joiner and Cabinet Maker.” In 1770 and 1771 William Jr. received commissions for two sets of walnut chairs from Thomas (1693–1781), Lord Fairfax, of Greenway Court in nearby Frederick County. Each set included one armchair priced at thirty shillings and six side chairs priced at twenty shillings. In 1928 Samuel T. Freeman and Company of Philadelphia sold a set of chairs—one arm and four matching sides—that reputedly belonged to Fairfax (fig. 52). Although the location of these chairs is unknown, an armchair identical to the pictured example (George Washington’s Fredericksburg Foundation) serves as a benchmark for separating Robert Walker’s work from that attributed to his nephew. The design of the armchair has clear antecedents in Robert’s work, but the shoe and rear seat rail are separate and the arms are secured to the stiles with mortise-and-tenon joints and screws.[49]

The most important craftsman associated with William Walker Jr. was Robert Cockburn (d. 1810), a Scottish immigrant who arrived in Virginia as an indentured servant and worked as a journeyman in Walker’s shop before moving west to Orange County in 1773. An account book maintained by Cockburn records his work in the Falmouth area from 1767 to 1772. For the first five years, he made furniture with no apparent compensation, including a set of chairs (a Marlborough-leg armchair and six matching sides) for William Walker Jr.’s brother Robert, the riding chair maker. Cockburn began receiving a salary of twenty-five pounds a year in 1772, but after settling all of his debts he took home less than six pounds.[50]

After moving to Orange County, Cockburn married, bought land, and acquired prominent clients like Colonel James Madison (1723–1801) of Montpelier Plantation. Madison hired Cockburn to make several household items including a dozen walnut Marlborough-leg chairs (figs. 53, 54). Priced at only 10 1/2 shillings each, this seating was significantly less expensive than William Walker Jr.’s. Ultimately, Cockburn’s chair shows how Robert Walker established a style that gained a foothold in northern Virginia, evolved into a vernacular design, and moved westward with members of his family and their journeymen.[51]

Colonial Virginia cabinetmakers have long been regarded as generically “British,” hailing from undifferentiated realms within the empire and introducing a neat and plain style. Robert and William Walker present a very different picture. They arrived as emigrants from Scotland and achieved acclaim through the patronage of many of Virginia’s richest and most politically prominent families. With a background steeped in Scottish baroque style, they produced elegant furniture for fashionable buildings that reflected their Caledonian origins. Through an expanding circle of family and associates, chair designs introduced by Robert Walker became the “ne plus ultra” of good taste in the Rappahannock River valley and beyond.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their generosity and assistance with this article, the author thanks Gavin Ashworth, Sara Lee Barnes, Luke Beckerdite, Jennifer Bean Bower, Carol Borchert Cadou, Mr. and Mrs. Hill Carter, Tara Gleason Chicirda, Catherine Dean, Ian Gow, Wallace Gusler, Ron Hurst, Judith Hynson, David Jones, Christine Joyce, Carl Lounsbury, Marilyn and Jim Melchor, Sumpter Priddy III, Sebastian Pryke, David Voelkel, Camille Wells, and Jon Zachman.

As quoted in John K. Nelson, A Blessed Company: Parishes, Parsons, and Parishioners in Anglican Virginia, 1690–1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), p. 93. William R. Brock, Scotus Americanus: A Survey of the Sources for Links between Scotland and America in the Eighteenth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1982), pp. 13–14.

Wallace Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1979), pp. 25–57. See also Wallace Gusler, “The Tea Tables of Eastern Virginia,” Antiques 127, no. 5 (May 1989): 1238–57. The author, Ron Hurst, and Tara Chicirda examined the Dunmore seating furniture illustrated in figures 30–34 of Gusler’s Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia. Comparison of these objects with furniture documented and attributed to Walker revealed subtle but important differences in construction, style, and scale. This led to the conclusion that the Dunmore seating is by another, yet-to-be identified Virginia cabinetmaker. Similarly, a detailed genealogical study of the provenances for pieces that appeared to be outliers quickly identified matrilineal connections to the Rappahannock River valley. The Bassett family desk-and-bookcase, for example, belonged in the nineteenth century to George Washington Bassett (1800–1878) of Hanover County whose wife, Elizabeth Burnett Lewis (1808–1886), was a direct descendant of Charles Carter of Cleve and Mary Ball Washington, two of Walker’s patrons discussed in this article (see Bassett Family Papers, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond). This study emphasizes the importance of matrilineal descent when considering the history of American furniture. Esther Singleton, Furniture of Our Forefathers (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1922), p. 137.

David Dobson, Scottish Emigration to Colonial America, 1607–1785 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994), p. 56.

Nelson, A Blessed Company, p. 94.

For more on Scotland and the tobacco trade, see T. M. Devine, The Tobacco Lords: A Study of the Tobacco Merchants of Glasgow and Their Trading Activities, c. 1740–90 (Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, 1975); and A Scottish Firm in Virginia, 1767–1777: W. Cuninghame and Co, edited by T. M. Devine (Edinburgh: Clark Constable, 1984).

Nelson, A Blessed Company, pp. 94, 375. Marshall Wingfield, A History of Caroline County, Virginia (Baltimore: Regional Publishing Company, 1975), p. 18. Dobson, Scottish Emigration to Colonial America, p. 103.

Virginia Gazette, July 13, 1775. Hew Scott, Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae: The Succession of Ministers in the Church of Scotland from the Reformation, vol. 5, Synods of Fife, and of Angus and Mearns (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1925), p. 460.

Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, or The British Architect (1715–1725; reprint, New York: Benjamin Blum, 1967), p. i.

Francis Bamford, A Dictionary of Edinburgh Wrights and Furniture Makers, 1660–1840 (London: Furniture History Society, 1983), pp. 46–48, 94–100. Sebastian Pryke, “The Extraordinary Billhead of Francis Brodie,” Regional Furniture 4 (1990): 81–99.

National Art Galleries, XVII and XVII Century American Furniture, New York, December 3–5, 1931, lot 483, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The Diary of Robert Rose: A View of Virginia by a Scottish Colonial Parson, 1746–1751, edited by Ralph Emmet Fall (Verona, Va.: Augusta-Heritage Press, 1985), pp. 52, 68.

John Mercer Ledger Book, 1725–1732, p. 82, bound MSS, d-13, Mercer Museum, Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Deposition of Landon Carter, August 2, 1770, Carter Family Papers, Sabine Hall Collection, Special Collections, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

The Register of Saint Paul’s Parish, 1715–1798, edited by George Harrison Sanford King (Fredericksburg, Va.: American Society of Genealogists, 1960), p. 146. Originally located in the cemetery of her cousin Henry Fitzhugh of Bedford, Elizabeth’s tombstone is now in St. Paul’s churchyard. The stone is inscribed “Here lies the body of Elizabeth, wife of William Walker of Stafford County and daughter of Henry Netherton, gentleman, deceased, who departed this life August the 26th, 1737, aged 29.” Margaret C. Klein, Tombstone Inscriptions of King George County, Virginia (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1979), p. 20. For the Fitzhugh and Tucker families, see Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 1 (1894): 269–70, and 7 (1900): 196–99, 317–19, 425–27.

For more on Walker’s architectural career, see Carl R. Lounsbury, The Courthouses of Early Virginia: An Architectural History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), pp. 176, 210–15, 238. Richmond County, Virginia, Order Book 11, 1739–1740, p. 96, Library of Virginia (hereafter cited as LOV), Richmond. Westmoreland County, Virginia, Order Book, 1739–1743, p. 123a, LOV. The Vestry Book and Register of St. Peter’s Parish, New Kent and James City Counties, Virginia, 1684–1786, edited by C. G. Chamberlayne (Richmond, Va.: Library Board, 1937), pp. 339–40.

Marcus Whiffen, The Public Buildings of Williamsburg, Colonial Capitol of Virginia (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 1958), pp. 134–36, 217. The Diary of Robert Rose, pp. 52 (February 11, 1750), 73 (March 15, 1750).

Stafford County, Virginia, Will Book O, 1748–1767, pp. 83–84, LOV. In June 1750 Nathaniel Harrison, who “alone took upon himself the Burthen in the Execution,” sold Walker’s 465-acre plantation for £349.8.3 to John Fitzhugh, son of Henry Fitzhugh of Bedford. Six years later, Harrison and Fitzhugh sold the same land to John Stuart of Stafford County (Stafford County, Virginia, Deed Book P, 1755–1764, pp. 95–97, LOV).

Stafford County, Virginia, Will Book O, 1748–1767, pp. 83–84, LOV.

Stafford County, Virginia, Will Book O, 1748–1767, pp. 523–27, LOV.

Bamford, A Dictionary of Edinburgh Furniture Makers, pp. 68–69, 123, 128. There are no other records for William Walker Jr. in Scotland after 1719. For William Walker Sr.’s estate papers, see Edinburgh Commissary Court, Reference CC8/8/85, National Archives of Scotland. This material can be accessed electronically via the website of Scotland’s People at www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk. John G. Dunbar and John Cornforth, “Dalkeith House, Lothian I: A Property of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry,” Country Life 175, no. 4522 (April 19, 1984): 1062–65. See also Miles Glendinning et al., A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 88–90. The author thanks Ian Gow and Sebastian Pryke for their assistance with theories on the Walker brothers’ Scottish origins.

Sebastian Pryke, “The Eighteenth Century Furniture Trade in Edinburgh: A Study Based on Documentary Sources” (master’s thesis, University of St. Andrew’s, 1995), pp. 11–12.

South Carolina Gazette (Charleston), October 27, 1739. Dendrochronology has confirmed that Stratford Hall was built during the late 1730s, placing William Walker in proximity at the time.

Glendinning et al., A History of Scottish Architecture, pp. 95–96. Smith’s Melville House also has an H-plan.

Edward Wenham, The Collector’s Guide to Furniture Design (English and American) from the Gothic to the Nineteenth Century (New York: Collectors Press, 1928), p. 216. The author thanks Luke Beckerdite for bringing this illustration to his attention.

For Mercer’s house construction accounts, see John Mercer Ledger Book, 1741–1750, pp. 32, 36, 48, 56, 63, 86, 115, Mercer Museum, Bucks County Historical Commission, Doylestown, Pennsylvania. See also C. Malcolm Watkins, The Cultural History of Marlborough, Virginia (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968), pp. 34–39.