Armchair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1723–1735. Maple. H. 46", W. 23", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Armchair, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1725–1735. Maple. H. 49", W. 23", D. 17 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and red oak. H. 53 1/4", W. 22 7/8", D. 17". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has its original Russia leather upholstery.

Plate 11 from William Macpherson Hornor, Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture (1935).

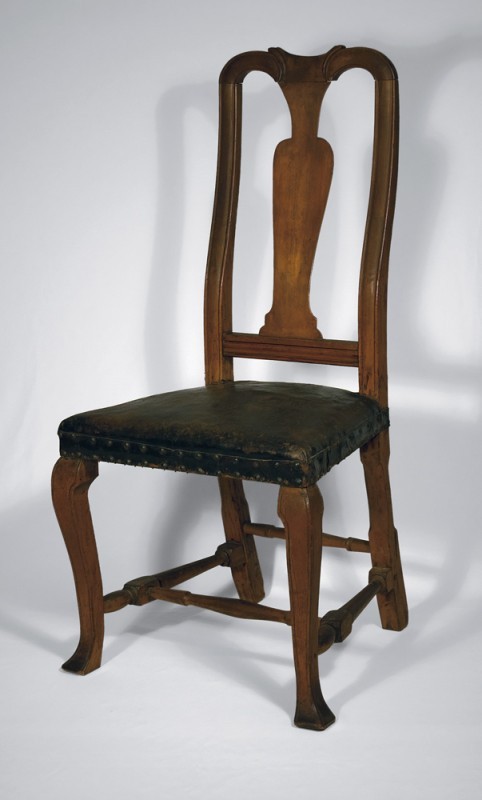

Side chair, Boston area, Massachusetts, 1728–1740. Maple. H. 41 1/2", W. 20 1/2", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Philip Zimmerman.) This chair has its original leather upholstery.

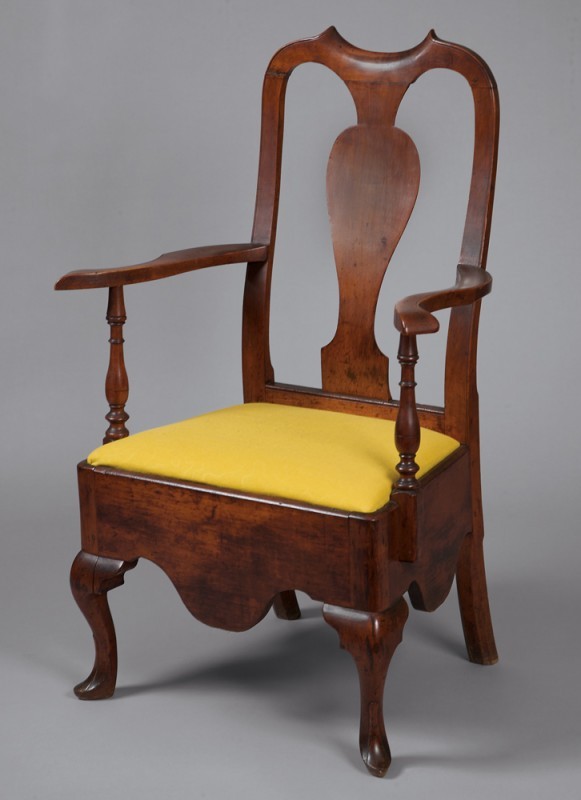

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1745. Maple with ash. H. 41 3/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The splint seat represented a modest savings in cost over leather.

Armchair, Boston area, Massachusetts, 1728–1740. Birch and cherry. H. 40 3/4", W. 22 7/8", D. 20 7/8". (Courtesy, Historic Odessa.)

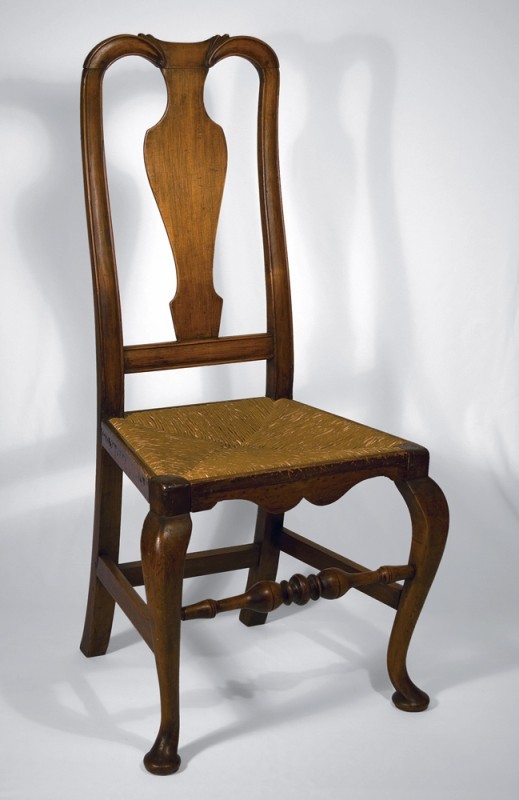

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Maple. H. 41 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Joe Kindig Antiques.)

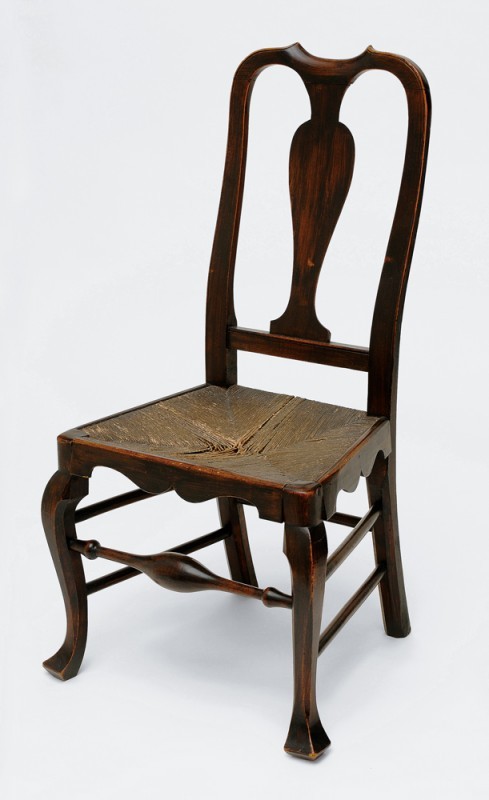

Side chair (one of a pair), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Maple with pine (seat). H. 40 3/4", W. 21", D. 19". (Courtesy, Wright’s Ferry Mansion.) The side and medial stretchers are similar to those on Boston chairs, but the plain rear stretcher on this chair and the example illustrated in fig. 8 is a Philadelphia convention.

Detail of the rear stay rail and seat rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 9.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1745. Cherry with white cedar. H. 42", W. 28", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton.)

Detail of the rear stay rail and seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11.

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730-1745. Maple. H. 42", W. 20 1/2", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Philip Zimmerman.)

Detail of the crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 13.

Detail of the splat and crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 5.

Detail of the splat and crest of a side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1730–1740. Walnut, walnut veneer. H. 40 5/8", W. 20 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton.) This chair was likely owned by James Logan of Stenton.

Detail of the splat and crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the right front leg of the chair illustrated in fig. 5.

Detail of the right front leg of the chair illustrated in fig. 8.

Side chair labeled by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Maple. H. 41", W. 19 1/2", D. 15". (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.)

Side chair labeled by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750.

Maple. H. 36", W. 19 1/2", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.)

Side chair labeled by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1760. Walnut with yellow pine (seat). H. 39", W. 21", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.) This chair is one of a pair.

“BOSTON CHAIRS” conveyed specific meaning to mid eighteenth-century Philadelphians. They used the term, sometimes expressed as “New England chairs,” in personal estate inventories and in advertisements beginning in 1739 or earlier. The best-known references are two advertisements placed by upholsterer Plunket Fleeson in the early 1740s in which he expressed frustration about the public’s preference for imported chairs over his own. Despite numerous other references, the historical record does not define what constituted a “Boston chair.” Furniture historian Richard Randall argued in a brief 1963 article that the term denoted leather-upholstered, rectilinear chairs with curved backs made in Boston and elsewhere in New England since the 1720s (figs. 1, 2). Randall’s definition and broader interpretation of “Boston chair” exports strongly influenced subsequent furniture scholarship. Yet significant problems with the evidence and findings remain and demand further examination. Foremost among them—but not the only one—is the troubling conclusion that these imports into the energized and influential city of Philadelphia were old-fashioned by the time they were first mentioned in historical sources.[1]

Boston chairs coexisted in Philadelphia with several other chair types. The 1774 estate inventory of local mariner James Taylor listed four “Boston Chairs” valued at three shillings apiece, in addition to eight “Square bottom walnut chairs” at one pound each, seven “compass bottom chairs” at ten shillings each, and four “green Windsor Chairs” given the same value as the Boston chairs. Time has obscured these once familiar descriptions. Only the term “Windsor” has retained its meaning, although the specific chair type Taylor owned requires knowledge of the styles available at that time and place, tempered by informed speculation. Furniture scholarship over the last four decades has retrieved the meaning of “square-” and “compass-bottom” chairs. The modern reader can now imagine a joined walnut chair with cabriole legs and a trapezoidal seat as the former and a similar chair with a rounded seat frame as the latter. Randall’s definition adds a William and Mary form to Taylor’s otherwise more fashionable seating.[2]

Furniture historians Brock Jobe, Benno Forman, and others have clarified much about the curved, leather-back chairs, which evolved from straight-back versions with turned rear posts that had already been in production for some twenty-five years (fig. 3). The earliest reference to the updated chair form is a February 27, 1722/23, entry in the account book of prosperous Boston upholsterer Thomas Fitch (1669–1736), recording the sale to Boston merchant Edmund Knight of “1 doz crook’d back chairs.” Fitch worked at the center of the largest furniture-making community in the early-eighteenth-century American colonies and was a major supplier of these chairs. He used several London upholsterers and factors to provide Bostonians and more distant clientele with fashionable textiles as well as the services of his thriving upholstery shop. Among several illuminating refer- ences mined from the Fitch Papers, Forman cited a 1709 letter from Fitch to Benjamin Faneuil of New York, “I wonder the chairs did not sell; I have sold a pretty many of that sort to Yorkers since, and tho some are carv’d yet I make Six plain to one carv’d; and can’t make the plain so fast as they are bespoke, so yo may assure [them] that are customers that they are not out of fashion here.” At once, the letter documents the two leather-back chair designs (namely those with carved crests and front stretchers and those with straight crest rails and turned front stretchers) preceding the crook’d-back version, confirms regular export of such chairs to New York, and suggests that Boston was an arbiter of colonial fashion.[3]

Manuscripts and shipping records document a steady stream of Boston- made chairs shipped to New York from 1700 through the 1730s. Despite rich anecdotal troves, evidence brought to light is still too fragmentary to quantify regional production. Fitch, furniture maker Nathaniel Holmes (1703–1774), and others also had regular trading relationships with Nova Scotia, Philadelphia, Charleston, and the West Indies during this period. Here again, robust numbers are unknown, but the historical record conveys a compelling sense of the enormous geographic range of this trade in Boston-made chairs. Twentieth-century dealers report finding Boston leather-back chairs in places that reinforce the pattern of widespread distribution, although specific provenances and other historical details have not been quantified or recorded, leaving this evidence largely unsubstantiated.[4]

Randall’s Boston chair analysis addressed circumstances in the 1740s as they were described in two frequently cited newspaper advertisements placed by Philadelphia upholsterer Plunket Fleeson (1712–1791) and first republished in 1929. As with the Fitch letter citation, each advertisement is densely descriptive and warrants replication in its entirety.

Made and to be sold by Plunket Fleeson, at the easy Chair, in Chestnut- Street. Several Sorts of good Chair-frames, black and red leather Chairs, finished cheaper than any made here, or imported from Boston, and in Case of any defects, the Byer shall have them made good; an Advantage not to be had in the buying Boston Chairs, besides the Damage they receive by the Sea; Good live Geese Feathers, Sea beds, bed-bottoms of good Duck at 20s, and all kinds of Upholsterers Work done after the best manner. N.B. He has a neat japan’d Chest of Drawers to be sold Cheap. (Pennsylvania Gazette, September 23, 1742)

Plunket Fleeson, Upholsterer, at the Easy-Chair, in Chestnut-Street, Philadelphia, Knowing that People have been often disappointed and impos’d upon by Master Chair Makers in this City, to the Prejudice of his Part of that Business, by Encouraging the Importation of Boston Chairs, Has ingaged, and for many Months, employed several [of] the best Chair makers in the Province, to the End he might have a Sortment of Choice Walnut Chair Frames; Gives Notice that he now has a great Variety of the newest and best Fashions, ready made, whereby all Persons who want, may be suppl’d without Danger of Disappointment or Imposition, at the most reasonable Rates; and Maple Chairs as cheap as from Boston. Also Feathers; Feather Beds, Bed Bottoms, Sea Beds, &c.–Ready Money for Horse Hair and Cow Tails. (Pennsylvania Gazette, June 14, 1744)

In addition to the two advertisements, Randall’s evidence included the dozen Philadelphia manuscript references to “Boston” and “New England” chairs, ranging in date from 1754 to 1773, that William Macpherson Hornor published in Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture (1935). Although Hornor quoted the 1744 advertisement at length and illustrated a crook’d-back leather-upholstered Boston chair, he did not connect the two, noting only the prevalence of “secondary rooms . . . still furnished with northern chairs” and captioning a conventional New England Queen Anne side chair with turned legs and stretchers as the chair type that challenged Fleeson (fig. 4). Randall’s third body of evidence was Boston customs records for 1744, which listed 299 chairs shipped to Newfoundland; Louisburg, Nova Scotia; New York; Philadelphia; Maryland; Virginia; North Carolina; and the West Indies. No features of any chairs listed were described except for the upholstery on “18 leather chairs” bound for Philadelphia. Randall combined his interpretation of the evidence with possible chair types and drew—what was for him— an unambiguous conclusion: it “reveals only one type of New England chair, and its variants, that was made of maple and covered with leather.”[5]

Furniture historians readily adopted Randall’s Boston chair term to describe Boston-made leather-back chairs in the baroque style, but their acceptance of dating was less consistent. Some, like Patricia Kane, noted his argument but dated the chairs no later than 1740, thus undermining the Fleeson connection. Others, like those at Historic Deerfield, dated the general chair form from 1710 to 1770, adding that thousands were made in Boston for export. Still others hedged their bets: Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye illustrated two examples of the same chair type yet assigned different date ranges to each. Despite the lack of specificity in the historical record, furniture historians have regularly maintained that these chairs were made for export. Jobe and Kaye stated that Boston chairs were “exported in great number from the port of Boston.” Forman concurred.[6]

More recently, scholars have upped the interpretative ante, although without benefit of additional evidence. Neil Kamil wrote, “Fitch and others flooded the affluent New York market with Boston leather chairs.” Fitch was “overwhelmed with orders from New York” in 1706, but by 1709 “there was a glut of leather chairs on the market for the first time.” Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown wrote of “the vast quantity of seating imported by [New York] merchants” that “evidently stifled the competition in New York.” Their vocabulary evokes images of large-scale, modern manufacturing, rather than the few dozen chairs that were shipped out of Boston from time to time. In the absence of supportable estimates of regional production, this profile remains impressionistic. Also reflecting modern sentiments, Kamil described Boston leather chairs as “shoddily made,” but without further explanation, leaving the reader to presume shoddiness was an inherent characteristic of export goods. Goods for sale, whether imported or not, were consistently represented as cheap. Indeed, Fleeson proclaimed that his chairs were as cheap or cheaper than Boston imports. Today, “cheap” is often a term of contempt. It can evoke the inexpensive, poorly made products of post–World War II Japan or several third- world manufacturers now. The Oxford English Dictionary, however, lists numerous pre-eighteenth-century references to “cheap” as meaning a bar- gain or good value, which is in keeping with the obvious intentions of advertising. Fleeson advertised because he believed his products were better, not shoddier, than others.[7]

Despite uncertain biographical details, Fleeson’s motivations shine through several other advertisements. In the earliest, published in the August 1, 1739, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, the aspiring twenty-seven- year-old identified himself as an upholsterer “lately from London and Dublin . . . [who] makes all Kinds of Upholsterers Work after the best Manner.” In fact, Fleeson was born in Philadelphia and probably did not travel to London and Dublin for work experience or for any other purpose. Instead, his advertisement made extravagant, self-aggrandizing claims (in keeping with eighteenth-century advertising practices in general) that underscored his ambition to impress. A 1755 advertisement reiterated this theme, stating that he “continues to make all Kinds of Upholsterers Work, Chairs and Joyners work, in the best manner and newest fashion.” Twenty years later he “Continues to carry on the Upholsterers business in the most fashionable and useful manner.” If this portrait is remotely accurate, it raises the compelling question of what conceivable advantage Fleeson saw in advertising out-of-date chairs—unless what he advertised were not those old-fashioned leather-back ones. Whether he was a true arbiter of style or merely self-appointed is immaterial because the differences between the two styles of chair were so apparent. The leather crook’d-back chairs looked angular, vertical, stiff, and simply old-fashioned when compared with the rounded, more organic lines of the prevailing style.[8]

Merchant Peter Baynton was the first person to advertise Boston chairs in Philadelphia. He offered “New England red Leather Chairs” for sale on February 8, 1739, and “red Leather Chairs” on November 19, 1741. Advertisements placed by at least seven other merchants suggest a composite picture of the kinds of chairs offered in Philadelphia between 1738 and 1748. The most detailed was William Reed’s 1738 advertisement for “walnut and maple fram’d Chairs with red and black leather Seats, common rush bottom’d ditto,” which captures all the essential features mentioned by Flee- son. Similarly, Evan Morgan’s “red Leather Bottom Chairs” (1738) and his “large Sortment of red and black Leather Chairs” (1743) as well as Abraham Shelley’s “walnut leather bottom chairs” (1747) were likely the same type of chair. Andrew Reed advertised “New England chairs” in 1752, indicating continued viability.[9]

The defining feature of the many references to Boston and New England chairs is the use of leather on “bottoms” only. Even Peter Baynton’s 1731 advertisement for “Red Leather Chairs” (with no geographic modifier) makes no reference to leather backs. When upholstery schemes differed from this standard and uniform practice, the wording was clear. Thus, chandler John Johnston and merchant Stephen Carmick left in their 1774 estate inventories “leather bottom & back chairs” and a “leather & leather back cher,” respectively, along with “6 Leather Bottom Chairs and 1 arm Chair” in Johnston’s house and “6 Mahoy. Chairs Furniture Damask Bottoms & Check Covers,” “8 Mahoy. Chairs Claw Foot worsted Bottoms,” several leather-bottom walnut chairs, and “1 Old Leather Bottom Arm Chair wh. Cushn.” in Carmick’s.[10]

Furniture scholars have searched for Philadelphia leather-back chairs in the Boston style with only limited success. Forman identified a crook’d- back armchair at Winterthur as having been made in Philadelphia (see fig. 2), which Randall, by contrast, published as a Boston product. For- man claimed two other examples were also from Philadelphia, although recent publication of one of them again assigns its origin to the Boston area. A privately owned crook’d-back armchair made of walnut is a fourth candidate. Given the vitality of the furniture-making trade in Philadelphia at mid-century and the prevalence of Boston and New England chair terms in Philadelphia’s written record, the survival rate seems implausibly low. Rejecting the premise that the Boston chairs in question were baroque examples with leather backs redirects the search to more fashionable forms (fig. 5). All share features described in contemporary documents and represent the “newest and best” in Boston and Philadelphia seating of their time. Moreover, the Philadelphia examples have structural and stylistic features different from their New England prototypes and show how artisans there responded to competitive products from another region (fig. 6).[11]

The armchair illustrated in figure 6 was attributed to New England until Forman correctly argued that it was made in Philadelphia. He pointed out that the turnings were atypical of New England, citing the scribe lines cut into the widest part of the arm support balusters and the flared cones at each end of the front stretcher as Philadelphia features. Other pertinent details that Forman neglected to mention for a chair of this kind and time include the plain, double side stretchers, unarticulated yoked crest, and mortise- and-tenon joints of the seat rails. The Boston armchair shown in figure 7 represents the type of chair that inspired the Philadelphia example. It was likely made in the 1730s and could have been loaded onto a boat for sale in some distant port.[12]

Design anomalies and redundancies in several maple side chairs reflect the market forces that Fleeson alluded to in his advertisements. The side chair illustrated in figure 8 resembles contemporary New England examples in having molded stiles and columnar side stretchers with rectangular blocked elements. On a New England chair, the blocks would have captured the ends of a medial stretcher, but the boldly turned front stretcher on the chair shown in figure 8 eliminated the need for that component. Although the maker imitated Boston chairs and chair parts, he made his seating with stretchers that joined leg to leg. Boxed stretchers were a strong tradition in modest Philadelphia seating and pointedly not a feature of Boston exports.

Boston side chairs of the period typically have H-stretchers. The maker of the chair illustrated in figure 9 followed that precedent but added a bulbous—and redundant—Philadelphia front stretcher. Unlike most con- temporary chairs, which have a shoe nailed atop the larger rear seat rail, this example has a large and redundant rectangular stay rail above the rear rail (fig. 10). The maker of the chair shown in figure 9 slavishly copied the distinctive Boston H-stretchers and splat without integrating them into the structure of the chair. The result was an inefficiently conceived object that must have been more expensive than its imported prototypes, but its existence underscores the competitive spirit within the Philadelphia chair- making community.[13]

The “closed” armchair illustrated in figure 11 also has a stay rail over the rear seat rail (fig. 12), but this object and the side chair illustrated in figure 9 are clearly by different hands. The maker of the armchair modeled the front legs and feet, whereas the artisan responsible for the side chair simply removed the tool marks from their sawn cabriole form. Other differences can be observed in the exaggerated peaks of the yoked crest and more bulbous splat of the armchair.[14]

Another maple side chair, illustrated in figure 13, embodies yet other reactions of Philadelphia chairmakers to Boston imports. Although the volute terminations at the juncture of the splat appear somewhat flattened, this chairmaker unambiguously replicated Boston treatments of the rear stile moldings and crest rail (fig. 14). The broad splat ending in a tapered base, however, and the cabriole legs ending in sharply angled feet with oversize pads were his own invention. The turned front stretcher incorporated scored rings around the balusters and flared cones at the ends, as seen in the armchair illustrated in figure 6. Variations in the design and construction of these chairs indicate that several Philadelphia chairmakers produced seating with Boston details, although Fleeson is the only one identified by name in the historical record.

Imports influenced Philadelphia chair design visibly—perhaps even broadly—but only in the lower end of the market. The archetypal Boston splat of this period was a simple, vasiform shape that lacked the ears, volutes, cusps, and complex curved edges of its Philadelphia counterpart (figs. 15–17). Philadelphia makers simplified the imported design further by eliminating the ogees at the base of the splat and allowing it to resolve in a rectangular mass. Philadelphia makers also simplified the ubiquitous Boston yoked crest by omitting the carved ridges at the termination of the rear stile moldings, a practice followed in many areas of New England at about the same time. Regardless of the specific timing and influences associated with this simplification, which blur in the absence of adequate evidence, Philadelphia yoked crests typically had more pronounced peaks than their New England counterparts. Scratch beads usually decorated the outside edge of Philadelphia rear stiles and crest shoulders, whereas those edges were unembellished in New England work. Perhaps the most visible borrowing from Boston imports was the square-section cabriole leg (figs. 18, 19). Local alteration included omitting the scratch bead from the arris or outer corner of the leg and usually softening it with a chamfer.

Side chairs attributed to William Savery (1721/22–1787) represent the largest group of Philadelphia seating influenced by Boston imports (fig. 20). Although made with rush seats rather than leather upholstery, these chairs featured decoratively shaped seat casings applied to the outsides of the seat front and sides. This extra bit of work imitated the more substantial joined seat frames of leather-upholstered chairs. Because Savory trained in Philadelphia under turned-chairmaker Solomon Fussell, Savery’s early products, including all of the rush-seat chairs, used the prevailing turned-chair construction of boxed stretchers composed of double side rungs and a swelled front stretcher that joined the front cabriole legs.

Given the dates of advertisements for Boston chairs in Philadelphia, con- current production of the Savery chairs seems fitting. Savery reached his majority in 1743, in the middle of the span of Fleeson’s advertisements for maple chairs “as cheap as from Boston.” Savery may have begun making chairs similar to the documented examples in the 1740s, but independent evidence suggests that the young craftsman probably did not begin using labels until after 1750. Another inconvenient finding supporting the later date lies in the chairs themselves. Of the five labeled maple chairs with splats and rush seats, three have eared crests and two have urn-shaped splats— details similar to those on Savery’s walnut examples (figs. 21, 22).[15]

The five documented Savery rush-seated chairs are remarkably consistent in their stylistic and structural details. These features separate his work from that of other chairmakers who produced similar Boston-inspired seating. The front legs of Savery’s chairs are chamfered below the edged arris, whereas those on comparable seating forms by at least one other maker have a chamfer that runs all the way down the outer corner of the front leg. The rear legs of Savery’s chairs also have lightly chamfered edges, while those on some related examples are octagonal in cross section. Savery cut a bead molding into the front face of the stay rail at the top edge, but other makers cut the bead on the corner of the top and front faces. Similarly, the vasiform section of Savery’s splats is noticeably higher than other designs, and his crest rail peaks are more pronounced in comparison. Although the historical record names only Savery and Fussell as makers of this type of chair, several other craftsmen must have been responsible for the many visually related examples that remain largely indistinguishable today. Fussell’s account book, for example, records several other artisans who worked for him or supplied him with chair parts.[16]

References to “Boston” and “New England chairs” can be found in Philadelphia estate inventories into the third quarter of the eighteenth century, but these terms disappeared from advertisements after about 1760, suggesting that the leather-seated, solid-splat chair form lost marketability. Windsors, which cost about the same, replaced them, at least in part. Yet persistent use of the term in estate inventories indicates how deeply ingrained and broadly recognized the distinctive chair form was in Philadelphia life. What did eighteenth-century Philadelphians see when they identified a chair as “Boston” or “New England”? A leather bottom was not the key. Extensive references after 1760 to leather-bottom chairs of walnut or mahogany, some “with claw feet and two shells on each,” demonstrate that leather was a cheap, durable option for framed chairs of many fashions. For example, a 1755 advertisement in the South-Carolina Gazette of May 15 advertised “black walnut, neatly carved, Spanish leather bottoms, lately imported per Capt. Ball, from London.” The minutiae of regional differences in construction or decorative details did not hold the key either. If they did, we should be able to find Philadelphia references identifying furniture of other regions. Two features stand out as likely candidates: square cabriole legs and simple vasiform splats, and possibly the urn variant as well. From a Philadelphian’s perspective, these features originated in Boston or New England. They were fashionable in the 1730s and 1740s, and they were used only on relatively inexpensive chairs of the kind that were widely exported. In addition to the Boston-made chairs, a large body of Philadelphia-made examples exists that reinforced widespread understanding of the term in that locale. The last piece of evidence is this: among the many splat-back maple chairs made in the late 1730s and 1740s and listed in the accounts of Philadelphia chairmaker Solomon Fussell were his “best,” which he sold for twelve or thirteen shillings in 1748. They were cheaper and better than Boston imports.[17]

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Joe Kindig III, Jenifer Kindig, Jay R. StieVel, and Lu Bartlett for their help in the preparation of this article.

Richard H. Randall Jr., “Boston Chairs,” Old-Time New England 54, no. 1 (Summer 1963): 12–20.

Inventory dated April 28, 1774, transcribed in Alice Hanson Jones, Colonial American Wealth: Documents and Methods, 3 vols. (New York: Arno Press, 1977), 1: 137–38.

Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730: An Interpretive Catalogue (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), p. 285 n. 15. Brock William Jobe, “The Boston Furniture Industry, 1725–1760” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1976), pp. 29–39, 42–45. Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 283.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 283–85; Jobe, “The Boston Furniture Industry,” p. 39.

Alfred Coxe Prime, comp., Arts and Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland and South Carolina, 1721–1785 (1929; reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1969), pp. 201–2. Pennsylvania Gazette, September 23, 1742, and June 14, 1744. William Macpherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture: William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), pls. 11, 16, pp. 17, 191. Randall, “Boston Chairs,” p. 13. The customs records were taken from Mabel Munson Swan, “Coastwise Cargoes of Venture Furniture,” Antiques 55, no. 4 (April 1949): 278, although she omitted “2 dozen chairs made here [i.e., Boston]” and destined for New York.

Patricia E. Kane, 300 Years of American Seating Furniture: Chairs and Beds from the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1976), cat. no. 40. Eleanor Gustafson, “Museum Accessions,” Antiques 117, no. 5 (May 1980): 1032. Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton MiZin, 1984), fig. III-31 (chair dated 1725–1740), cat. no. 91 (chair dated 1724–1750), pp. 11, 339. Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 281.

Neil D. Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in Colonial New York,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite and William N. Hosley (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1995), p. 196. Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown Jr., “Boston and New York Leather Chairs: A Reappraisal,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1995), pp. 175–94. Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” p. 192.

For Fleeson’s birthdate, see Norris Stanley Barratt, Outline of the History of Old St. Paul’s Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1898 (Philadelphia: Colonial Society of Pennsylvania, 1917), pp. 30–31, 239. Pennsylvania Gazette, August 7, 1755; Pennsylvania Packet, February 20, 1775.

For Baynton’s advertisements, see Pennsylvania Gazette, February 8, 1739, and November 19, 1741. Merchants who advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette included William Reed (April 20, 1738), Jonathan MiZin (August 17, 1738), Evan Morgan (October 5, 1738, and December 29, 1743), Richard Pitts (July 22, 1742), Edward Shippen (December 21, 1742), Abraham Shelley (July 30, 1747), and Isaac Jones (August 18, 1748). Reed advertised “New England” chairs in the Pennsylvania Gazette on August 17, 1752; September 21, 1752; December 14, 1752; and January 16, 1753.

Pennsylvania Gazette, September 23, 1731. Inventories of John Johnston, dated November 12, 1775, and Stephen Carmick, transcribed in Jones, Colonial American Wealth, 1: 127, 245.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 348; Frances Gruber SaVord, American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 1, Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), cat. no. 34, pp. 93–95.

Benno M. Forman, “Delaware Valley ‘Crookt Foot’ and Slat-Back Chairs: The Fussell- Savery Connection,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 62–63. Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1997), cat. no. 5.

The chair is discussed in Philip D. Zimmerman, “Philadelphia Queen Anne Chairs in the Collections of Wright’s Ferry Mansion,” Antiques 149, no. 5 (May 1996): 742–43.

Discussed in Philip D. Zimmerman, “Eighteenth-Century Chairs at Stenton,” Antiques 163, no. 5 (May 2003): 126. For another armchair of this general type, see Sotheby’s, Important Americana from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. James O. Keene, New York, January 16, 1997, lot 199.

Philip D. Zimmerman, “Early American Furniture Makers’ Marks,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 136–37. Examples illustrated in Hornor, Blue Book, pl. 314 (privately owned); Helen Comstock, American Furniture: Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century Styles (New York: Viking Press, 1962), fig. 176 (owned by Colonial Williamsburg).

Labeled chairs include one privately owned and illustrated as pl. 462 in Hornor, Blue Book, one of a set of six at the Pennsylvania State Museum, one in the Dietrich American Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and one sold at Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 16–17, 1999, lot 766. Forman recognized the existence of the non-Savery examples but assumed all chairs of this general type were by either Savery or Fussell. Forman, “Chairs,” pp. 45, 48–52.

Jacob Schreiner advertised the loss of “four leather bottom ditto [chairs], New England make” among many other household articles in the Pennsylvania Packet, November 21, 1778. Pennsylvania Packet, November 21, 1778. Fussell Ledger, quoted in Forman, “Chairs,” p. 43.