Pier table attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration by John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1809. White pine and white ash; brass mounts. H. 34 1/2", W. 48", D. 23". (Courtesy, Nichols House Museum, Boston; photo, David Bohl.)

Detail of the pier table in fig. 1. At least two other tables by Thomas Seymour have two pairs of similarly shaped supports.

Taylor Greer, Rose Standish Nichols, Massachusetts, ca. 1912. Watercolor on paper. 4 3/4" x 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Nichols House Museum.) Nichols was forty when she sat for this miniature. She probably acquired the pier table illustrated in fig. 1 after 1930.

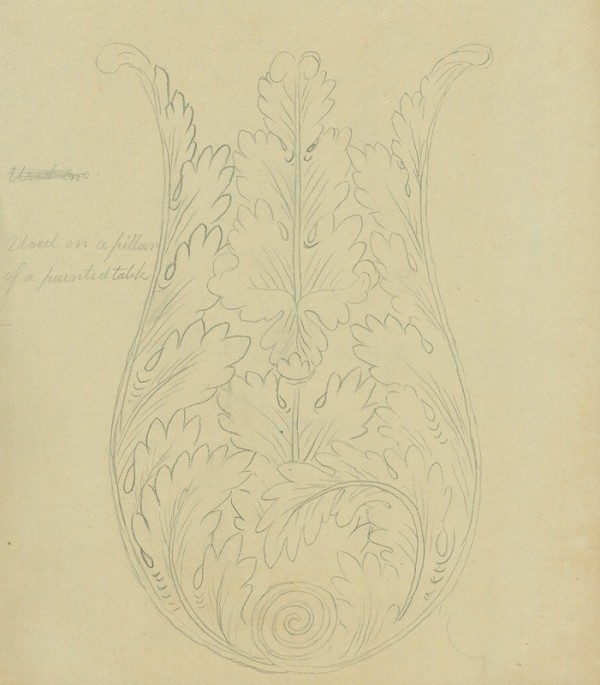

Lyman White, tracing, Boston, Massachusetts, probably before 1835. Graphite on paper. 9 15/16" x 8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) White probably traced one of the supports on the pier table illustrated in fig. 1 when he repainted the top.

Ornament for a Frieze or Table illustrated on pl. 56 in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Makers and Uphosterer’s Drawing-Book (1793; reprinted, 1802). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The identical design in Thomas Seymour’s copy of the first edition was Penniman’s source for the decoration on the frieze on the pier table illustrated in fig. 1.

Églomisé and gilt glass panel on the frieze of a card table, Baltimore, Maryland, 1805–1815. (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey Associates.)

Ornament for a Tablet & Various Leaves illustrated on pl. 2 in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Makers and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1802). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) Penniman may have used the leaf decoration at the bottom of this plate as inspiration for the decoration on the supports of the pier table illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the gilt and glazed leafage on the right front support of the pier table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Robert Mussey Associates.) Penniman built up several layers of transparent oil glaze, beginning with the palest color, with successively darker layers applied at an angle or at right angles to the previous one.

Detail of the gilt and glazed leafage on the right front support of the pier table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Robert Mussey Associates.)

Card table attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1815. Maple and white pine with white pine. H. 30 3/8", W. 35 3/4", D. 18 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey.) This card table is one of the earliest examples with a top that rotates around a threaded iron pivot rod to reveal an inner well for cards and game pieces. The interior wells are repainted with a pale “sky blew.” The upper edges of the rails are faced with thin undyed morocco leather instead of the customary wool baize.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1815. Mahogany. H. 20 3/4", W. 19", D. 25 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the right front leg of the card table illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the decoration on the front legs and seat rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 11. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The decoration is not as refined as that on the pier table illustrated in fig. 1. Its incorporation of pale gray shadowing, rounded leaf tips, faux reeding, and several tints of transparent brown glaze over gold-leaf designs suggest that the work is by Penniman or one of his apprentices or 13journeymen.

Detail of the center panel on the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the kerfed and bent glue blocks on the underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 10.

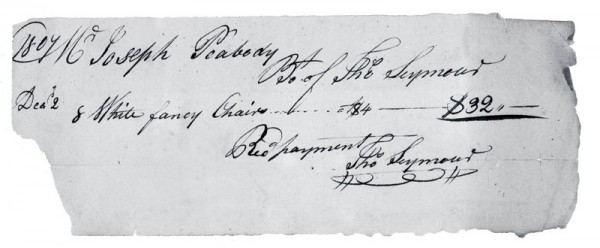

Joseph Peabody’s receipt for white fancy chairs from Thomas Seymour, Boston, Massachusetts, 1807. (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey Associates.) Peabody was a successful Salem ship captain who became a merchant.

Card table attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1810–1815. Rosewood and rosewood veneer with white pine, birch, ash, and mahogany; brass mounts, stringing inlays, and moldings. H. 29 3/4", W. 36", D. 17 9/16". (Courtesy, Historic New England; photo, David Bohl.)

Detail of the lyre support of the card table illustrated in fig. 17.

Detail of the painted decoration on the top of a commode chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1809. (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the M. and M. Karolik Collection of Eighteenth-Century American Arts, 23.19.)

Workbox attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration by John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1814. Satinwood and bird’s-eye maple veneer, with mahogany and satinwood. H. 3 1/2", W. 8", D. 10 5/8". (Private collection.)

Dressing table attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1814. Mahogany, bird’s-eye maple and satinwood veneers, with white pine, mahogany, ash, and soft maple. H. 73", W. 45", D. 25". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The table reputedly descended from Elizabeth Derby (West) of Salem.

Worktable attributed to Thomas Seymour with top decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1814. Maple and bird’s-eye maple veneer, with eastern white pine and cherry. H. 29", W. 20 1/2", D. 15 1/4". (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.) The decoration of the drawer fronts and side rails appears to be by a schoolgirl. This table is one of five with similar floral decoration on the top.

Detail of the top of the worktable illustrated in fig. 22. (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey.)

Dressing table, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1815. Soft maple with eastern white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.)

Side chair from the shop of Samuel Gragg with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1812. Birch, white oak, and beech. H. 34 3/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 25 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The chair is branded “S.GRAGG / BOSTON” under the front rail and “Patent” under the back rail. Gragg and John Penniman both leased space in Thomas Seymour’s Boston furniture warehouse in 1809.

Detail of the decoration on the front legs and seat rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 25. The use of faux-fluted panels with “mitered” corners, four colors of sienna and umber brown glazes, and faux-shadowing from the upper left resemble Penniman’s work on the pier table illustrated in figs. 1, 2, and 8.

Side chair from the shop of Samuel Gragg, Boston, Massachusetts, 1808–1812. White oak with unidentified woods. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey Associates.) The chair is branded “S.GRAGG / BOSTON” under the front rail. It has been repainted to match evidence from pigment analysis and microscopy of related chairs.

Hood of a clock attributed to Thomas Seymour with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1809-1812. Mahogany, bird’s-eye maple, and mahogany veneers, with white pine. H. 111 3/4", W. 22 1/4", D. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Peabody Essex Museum.) The movement is by Scottish immigrant clock maker James Doull. He worked for Aaron Willard from 1807 to 1808 before establishing his own shop in Charlestown in 1809. The brass finials are replaced.

John Penniman, Aaron Willard Jr., Boston, Massachusetts, 1804. Oil on canvas. 28" x 23". (Willard Clock Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Willard became a clockmaker like his father, Aaron Sr. Penniman painted at least six members of Willard’s extended family between 1804 and 1810. Although the artist’s shading of the face and hands displays subtle gradation, the background foliage is similar to that on Penniman’s furniture painting.

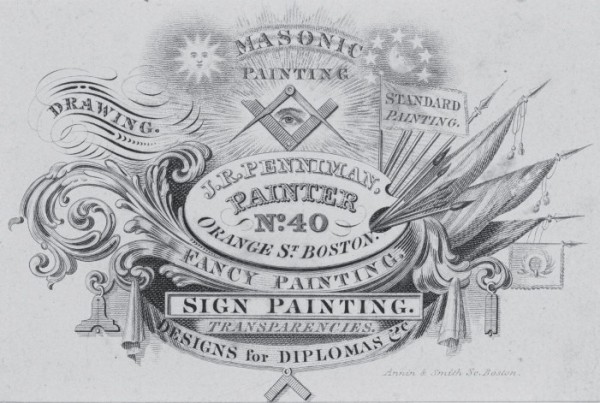

Trade card of John Penniman, Boston, Massachusetts, 1822. Engraving on paper. 3" x 4". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) William B. Annin and George Girdler Smith based this engraving on a painted design by Penniman.

John Penniman, preparatory painting for a membership certificate for the New England Society for South Carolina, Boston, Massachusetts, 1820. Pen, ink, and wash on paper. 11 5/8" x 15 5/8". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) The painting is inscribed at the lower left “Design’d & Drawn by J. R. Penniman. Boston.” Much of Penniman’s known work between 1815 and 1830 consists of preparatory drawings and paintings for Boston’s publishing industry.

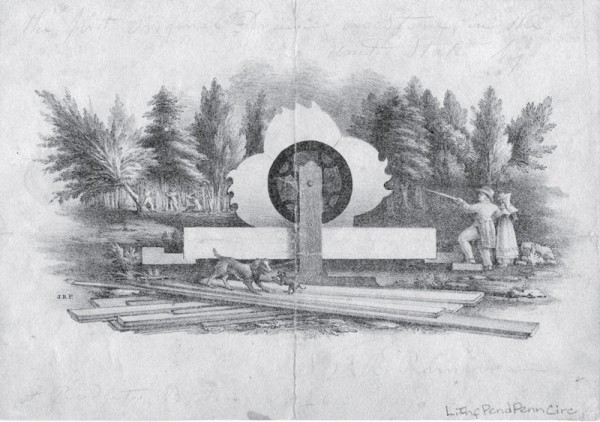

John Penniman, Circular Saw, Boston, Massachusetts, 1826. Lithograph on paper. 3 1/2" x 7". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) The lithograph is inscribed “the first original Drawing on Stone, in the United States by / J. Pendleton Boston J. R. Penniman / 1826.” The earliest documented lithograph in the United States was done in 1819.

John Penniman, Pianoforte in the Shape of a Bentside Piano, Boston, Massachusetts, 1829–1834. Watercolor on paper. 17" x 12". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) The painting is inscribed “Drawn by Jn.o R. Penniman.” He may have painted the watercolor to accompany a patent application by Boston pianoforte maker Alpheus Babcock. The fly is a reference to Mary Howitt’s popular poem “The Spider and the Fly,” published in 1829.

John Penniman, Unquety House, Milton, Massachusetts, 1827. Watercolor on embossed French writing paper. 7 1/2" x 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Milton Historical Society; photo, Robert Mussey.) Penniman’s name is written on the reverse.

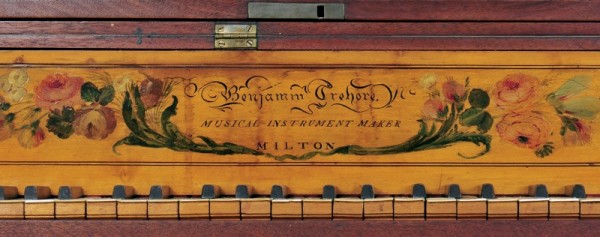

Detail of a name board on a pianoforte by Benjamin Crehore with decoration attributed to John Penniman, Milton, Massachusetts, 1815–1830. (Private collection; photo, Robert Mussey.)

Detail of the painted peacock feathers on the back of a side chair from the shop of Samuel Gragg. (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.)

A recently discovered pier table bearing the inscription “Painted in M ____ 1809 by John P___niman” is the only piece of furniture signed and dated by John Penniman (1782/83–1841), Boston’s most important decorative painter of the federal period (figs. 1, 2).The table is attributed to the shop of cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour (1771–1848) and is also the only Boston example with painted and gilded decoration in the “antique taste.” It may have been part of a suite that included at least one other identical table, a card table, and a set of chairs decorated by Penniman or a craftsman associated with him. The table’s ornament is based on two plates in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (1793), but its unique form and novel adaptation of published designs reflect the penchant of both Seymour and Penniman for experimentation. The sophisticated application of the decoration indicates that Penniman was at the height of his abilities at the age of twenty-seven. Based on the distinctive style and painting techniques manifest in this work, several other pieces of Boston furniture with painted and gilded decoration can now be tentatively attributed to him.[1]

Furniture Painting and Painters

At a time when Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York painters led the new nation in the production of fancy furniture, their Boston counterparts tended to focus on clock dials, reverse-glass tablets, carriages, Masonic regalia, military banners, shop signs, floor carpets, window shades, transparent illuminations for public celebrations, and fire buckets—the “thousand etceteras” of decorative painting. In 1823 Boston painter Charles Hubbard advertised “coach and chaise Bodies ornamented with Arms, Initials, Borders, &c.” as well as “Military Standard Painting, Sign Painting, Masonic and fancy Painting, Landscape and marine do, Clock and Timepiece Do, Gilt and painted ornaments for ships.” Boston craftsmen did produce fancy-painted seating but in lesser quantity than chair makers and decorators in most other urban centers. In addition, most Boston fancy chairs are stylistically conservative in comparison with contemporary examples made in the Middle Atlantic region and the South.[2]

Boston newspapers from the first decade of the nineteenth century document the importation of thousands of fancy-painted chairs. In the February 23, 1805, issue of the Columbian Centinel, furniture warehouseman William Leverett reported that he had just received as “great a variety of Furniture as was ever offered for sale in the United States; fancy japanned Chairs, and other Furniture to match, suitable for a Room, constantly arriving from Philadelphia. Orders executed for any article in the fancy Japanned line, from the first Japanners, in Philadelphia, by the above.” Two years later, he advertised chairs “in the latest styles, as good as may be had in Philadelphia.” In 1807 the furniture warehousing firm Nolen & Gridley imported three hundred fancy chairs “of different patterns” from “one of the first manufactories in New-York.” It claimed that aside from a surcharge for shipping, the prices were the same as those of the manufacturer. Among the fancy seating forms mentioned in Nolan & Gridley’s advertisement were chairs with “white and gold double shells and green Tops, cane color Scroll Back[s], coquilico and gold Grecian border[s], green and gold double Cross Backs, Tulip tops, white and gold double cross do. Bronzed Tops, Coquilico do. Eagle Tops, Salmon do. Grape leaf, Orange and Red.”[3]

Although imported fancy furniture set a standard for style and quality in Boston, painted and gilded seating, tables, and case pieces were less popular there than in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, where immigrant artisans appear to have contributed to the taste for fancy furniture. In Baltimore, Irish émigrés John (1777–1851) and Hugh Finlay (1781–1831) dominated the market for painted objects in the neoclassical, or “antique,” taste. English immigrant George Bridport (b. England before 1794–d. 1819) worked in a similar style for prominent Philadelphia patrons like William Waln. A few British painters and gilders were active in Boston during the federal period. “J. White” advertised chair japanning and ornamental painting of signs, architecture, and furniture from his shop “near the Common” at 45 Pleasant Street: “He having been employed in the first professional houses, both in England and India—the latter of which exceeds every other country, in the art of japaning; and he flatters himself capable of adducing work equal in point to any yet imported; and with greater dispatch than any other person in this State. . . . N.B. Bamboo and fancy chairs re-painted, as new.” White’s career in Boston was brief, however, possibly owing to lack of demand for sophisticated neoclassical painted decoration and the economic decline following President Thomas Jefferson’s embargo on trade with Britain from 1807 to 1808.[4]

Fifteen or fewer immigrant decorators are known to have worked in Boston during the federal period. Moreover, several of these craftsmen were principally gilders and looking-glass makers who occasionally did reverse glass–painted tablets for looking glasses and clocks. James Sharp is the only one who achieved success as a furniture decorator but not until the 1820s. Prior to that, Jefferson’s embargo and the War of 1812 ruined the local market for luxury goods. Most of the immigrant decorators who went to Boston left after a short period, seeking greater opportunities in New York, Baltimore, Norfolk, Charleston, Savannah, or other coastal Atlantic urban style centers whose economies were less adversely affected by the embargo and the war. There is no evidence that an ornamental painter as skilled as Bridport or the Finlays ever worked in Boston, and that city’s apparent aversion to the French taste precluded the introduction of verte antique and decorative gilt finishes like those associated with New York cabinetmaker Charles Honoré Lannuier.[5]

Boston Painted Furniture in the Antique Style

Although the pier table illustrated in figure 1 may have been part of a suite of paint-decorated furniture, its early provenance remains unclear. Boston landscape designer and women’s rights advocate Rose Nichols (1872–1960) probably purchased the table during or after the 1930s (fig. 3). There is no documentary evidence that she inherited it from her parents, Arthur and Elizabeth Nichols, whose house on Beacon Hill was one of five buildings that architect Charles Bulfinch designed for Massachusetts and United States Senator Jonathan Mason and his four daughters. A late-nineteenth-century pencil sketch by Boston decorative painter and varnisher Lyman White (1800–1880) was traced directly from one of the pier table supports (fig. 4) and bears the penciled notation “used on a pillar of a painted table.” White may have done the sketch while the table was in his shop for repainting of worn and stained top surfaces. If so, this work would probably have occurred before 1838, when he became foreman for the Chickering Piano Company.[6]

The 1809 date on the pier table is significant, for in that year Penniman rented shop space in Thomas Seymour’s warehouse on Common Street. Other facts and features supporting the theory that Seymour’s shop made the table include his and Penniman’s collaboration on other furniture in that year, the table’s distinctive stamped sheet-brass hardware, and the use of ash as a secondary wood. John and Thomas Seymour are the only Boston cabinetmakers known to have used ash before circa 1817. Also typical of Thomas’s work are scrolled feet that form a slightly asymmetric, flattened oval; the use of two pairs of supports; and a thick front-to-back medial rail that is dovetailed to the front and rear rails and secured to the tops of the supports with wedged mortise-and-tenon joints. Although “lyre base” is the term commonly used to describe tables of this type, Boston newspaper advertisements of the period occasionally refer to examples with a “harp base.”[7]

The decoration on the front rail of the pier table depicts a pair of classical griffins and arabesques of scrolling leafage flanking a burning pyre. It was copied from a design on pl. 56 in Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (fig. 5). Similar motifs occur on several Baltimore painted tables with églomisé painted-glass tablets, attesting to the popularity of that engraving among American furniture makers and their patrons (fig. 6). Penniman almost certainly had access to Thomas Seymour’s signed copy of the Drawing-Book, but it is impossible to determine which craftsman actually chose the design for the decoration on the pier table. The painted acanthus leaves on the baluster-and-pillar supports may have been inspired by the “Ornament for a Tablet & Various Leaves” shown on pl. 2, no. 43 (fig. 7) as well as other engravings in Sheraton’s book. Being largely self-taught, Penniman adapted techniques and borrowed designs from many sources.[8]

Penniman’s painting style is distinctive. The acanthus leaves on the supports have organic, rounded tips, and some curl as they terminate, leaving “eyelets” along their edge. The leaves were articulated with five different shades of brown oil glaze, ranging from very pale, transparent sienna to a very dark, opaque brown umber (fig. 8). Layers of glaze were built up with parallel, curving brushstrokes, with each layer oriented roughly at right angles to the previous layer. These techniques, which create the illusion of shadows, depth, and flow, are related to cross-hatching used by contemporaneous engravers. It is conceivable that engravers’ techniques, which were manifest in the Drawing-Book and other period sources, influenced Penniman’s handwork as much as his designs. He is the only Boston decorator known to have used short, fluid brushstrokes to apply layers of glaze at right angles to one another. This idiosyncratic technique is also used in his signed watercolor depicting a stringer of three fish.[9]

To give his work volume and dimension, Penniman used shades of pale or drab gray paint to simulate shadows on the right and below his leafage, figures, and panel bordering. This technique, which gives the illusion of a light source at the upper left, is manifest in all his work (fig. 9). The primary components of the pier table are highlighted with stripes of the same pale gray, a darker gray, and a separating line of dark reddish brown. On the top, the stripes are graduated in depth of color and “mitered” at the corners to simulate the applied beaded moldings on English Regency furniture.[10]

A card table and set of four painted and gilded fancy chairs—one bearing the stenciled name “Holden”—display similar techniques and can tentatively be attributed to Penniman or one of the workmen in the decorator’s shop (figs. 10, 11). The decoration on this suite is also related to that on the pier table, although the leaf designs on the card table and chairs are somewhat less refined (figs. 12, 13). All have moldings simulated with sienna and umber striping and detailed with layers of brown glaze. The seating was formerly attributed to New York chair maker Asa Holden, but it is more likely that they are from the shop of Joshua Holden, a Boston chair maker and chair painter.[11]

The card table has several painted and gilt designs that are virtually identical to those on the chairs: a stylized shell surrounded by leafage (fig. 14), acanthus leaves with prominent central veins, roundels, and shadowing in two shades of gray (fig. 12). The shading of the leaves and shell and the use of several hues of brown glazing provide further evidence that the same hand decorated these objects. Attribution of the table to Thomas Seymour’s shop is supported by its fastidious construction, square shaping of the legs, paneled therm foot design, and distinctive use of kerfed and bent glue blocks on the underside (fig. 15). Small beaded moldings are set into precisely cut grooves around the ankles and below the cyma-shaped elements of the legs—another feature associated with Seymour’s furniture (fig. 12).

Joshua was probably the son of David Holden, born April 3, 1781, at Townsend, Massachusetts. The younger Holden first appeared in Boston tax records in 1807, when he was described as a chair maker in partnership with Asa Jones in Ward 12. Assessments from 1808 to 1811 listed Holden as an independent craftsman on Washington Street, which was just over a block from Seymour’s furniture warehouse.[12]

Newspaper advertisements and other primary documents pertaining to Thomas Seymour reveal that he frequently hired other artisans to make furniture that he sold under his own name. From 1804 to 1805, he was in partnership with Samuel Tuck, a chair maker and painter who probably supplied the showrooms with fancy seating. Tuck may have made the set of “8 White fancy chairs” for which Seymour charged Salem merchant and shipowner Joseph Peabody $32.00 on December 2, 1807 (fig. 16). Tuck left the partnership in 1807 and opened a “Paint Warehouse.” That business prospered until the financial decline preceding and during the War of 1812 forced him out of business. From 1808 to 1809, Seymour was in partnership with James Cogswell, a cabinetmaker who is not known to have made chairs. It is plausible that they turned to Joshua Holden to provide fancy seating like that previously furnished by Tuck.[13]

It is also possible that the chairs and matching card table (figs. 10, 11) were actually decorated by one of the many painters whom Penniman either trained or employed over his long career. Alvan Fisher (1792–1863), who began his term in 1810, recalled his attempts to learn academic landscape painting techniques: “In consequence of this determination to be an artist I was placed with a Mr. Penniman who was an excellent ornamental painter. With him I acquired a style which required many years to shake off—I mean a mechanical ornamental touch and manner of coloring.” Other Penniman apprentices included Thomas Badger, Charles Bullard, Thomas Cunningham, Charles Hubbard, Henry Loring, Nathan W. Munroe, Nathan Negus, Henry Nolen, Asa Parks, and Moses Swett. Several of these men were working independently during the period when the chairs and card table were made, but except for clock dials, none of their furniture work is documented.[14]

If Penniman did not decorate the suite himself, a leading candidate would be Nathan W. Munroe, who was nearing the end of his apprenticeship in 1809. In the August 25, 1810, issue of the Columbian Centinel, Munroe reported: “[Munroe] . . . has taken the Shop in the North end of the Boston Furniture Warehouse, near the bottom of the Mall, lately occupied by Mr. John R. Penniman, with whom he served his apprenticeship. . . . He offers his services as Painter of Standards, Signs, Window and Bed Cornishes, Chairs, Toilets, tables, and articles in the Furniture Line.” These dates and qualitative differences between the painting on the pier table and chairs suggest that Penniman may have assigned decoration of the seating to the less-skilled Munroe.

A group of Boston card tables has gilt acanthus leaves with multiple brown glazes applied in a manner almost identical to that on the signed pier table (figs. 17, 18). These painted motifs echo the carved leaves on other card tables attributed to Seymour as well as the English Regency examples that inspired them. Furniture historian Edwin Hipkiss established the connection between Penniman and Seymour when he discovered a receipt for a demilune commode chest the cabinetmaker made for Elizabeth Derby of Salem, Massachusetts. Dated the same year as the pier table, the receipt lists Seymour’s charges for making the chest, English immigrant Thomas Wightman’s charges for carving leaves and moldings, and Penniman’s charges for painting a panel depicting shells and seaweed at the rear of the top (fig. 19). The exceptional artistry evident on the panel of the commode and on the ornament on the signed pier table suggests that Penniman was Seymour’s decorator of choice for the finest work.[15]

A small lady’s workbox bearing the painted initials “J R P” is the only other piece of furniture known that is marked by Penniman (fig. 20). Reputedly made for Elizabeth Derby, the box is decorated on top with a painted shell that is closely related to that on the panel of the commode chest. The refined construction, mahogany lining, and bird’s-eye maple and curly satinwood veneers suggest that Seymour’s shop made the box, possibly in the same year as the commode. All other documented, signed, or initialed examples of Penniman’s work are either clock dials, painted-glass tablets for clocks, landscape or portrait paintings, heraldry panels, engravings, or prints.[16]

Several pieces of furniture attributed to Seymour’s shop have painted decoration that was probably executed by Penniman or, at the very least, influenced by his work. Included in this group are a number of lady’s dressing tables with elegant gilt leafage and striping (fig. 21). He also appears to have been responsible for the decoration on at least six lady’s worktables with refined flower and leaf painting (figs. 22, 23) and a set of quartetto, curly-maple side tables with bamboo-turned legs and elaborate tops. The painter’s naturalistic representation of the flowers, which he probably observed from life, allows for the identification of fifteen different species, all of which were grown contemporaneously in New England.[17]

A dressing table bearing the label of Boston looking-glass maker Stillman Lothrop (1780–1853) features a gilt version of the shell and seaweed motif associated with Penniman (fig. 24). The painter’s use of silver leaf and gold-tinted glazing on the looking-glass balls complements the gilt shell and gives the decoration a bold yet idiosyncratic appearance. Penniman may have first met Lothrop while doing minor decorative painting for Dorchester cabinetmaker Stephen Badlam, in whose shop Stillman and his younger brother Edward apprenticed. In 1822 Penniman’s shop was directly above Stillman Lothrop’s, providing easy opportunity for their collaboration.[18]

Samuel Gragg, who patented “elastic” bentwood chairs, was another important Boston furniture maker who appears to have contracted work to Penniman (fig. 25). As is the case with the Nichols pier table (fig. 1), many of Gragg’s chairs have fluting simulated with multiple lines of shadowed striping (fig. 26). Some Gragg chairs also have gilt leaves and scrolls similar to those associated with Penniman. Others display spectacular peacock feathers composed of layers of three colors of gold powder applied in opposing directions (fig. 27).[19]

Other Painting Associated with Penniman

John Penniman began painting on a wide variety of surfaces during his teens and early twenties. He was born in the small rural town of Milford, Massachusetts, and claimed to have been self-taught. Penniman’s earliest known work is a painted clock dial, which he signed and dated 1794. Fewer than a dozen of his documented dials are known, and the highest number he recorded next to his signature is sixteen. Since these numbers do not appear to have been chronological, they may have referred to account book entries.[20]

Penniman’s use of relatively pale, unsaturated colors on moon dials and the style of his signature and numbering have cognates in the work of John Minott (1772–1826) and William Trescott. Since Penniman and Trescott were about the same age, it is possible both men trained or worked with Minott, who was one of the leading decorative painters in Boston and Roxbury. Several of Penniman’s painted dials also incorporate thick foliage branches or twigs as part of the fruit-painted decoration on dial corners, a feature found occasionally on English dials but not on those of other Boston painters. His favorite subject, however, was the Four Seasons (fig. 28).[21]

The scarcity of Penniman’s signed dials suggests that he did clock work only early in his career, probably to support himself while endeavoring to become a portrait and landscape painter. His apprentices Alvan Fisher and Charles Codman followed a similar career path. Penniman’s earliest known painting is a miniature self-portrait dated 1796 and inscribed “John R. Penniman age 14 years.” An early photograph of the miniature bears the notation “From John R. Pennimans First Portrait age 14 years From a boys first Portrait taken from a looking glass age 14—the work of John R Penniman, Hardwick, Mass.”[22]

Eight years later and with considerably more skill, Penniman painted at least four portraits of the Willard family. Aaron Willard Jr.’s portrait is signed, dated 1804, and inscribed with the sitter’s age (fig. 29). Willard is shown sitting in a painted, bamboo-turned Windsor side chair wearing a high-collared, ruffled shirt and formal waistcoat. Although Penniman’s portrait is reasonably realistic, the treatment of leafage in the background retains the distinctive hard-edged style of a decorative painter. Similar portraits of Aaron Sr., his daughter Nancy, and his house and clock-manufacturing complex also date circa 1804. The following year Penniman painted a portrait of Aaron Sr.’s wife, Susan (Bartlett), and in 1806 he provided a likeness of Willard’s son-in-law, painter Spencer Nolen.

Between April 1803 and April 1805, Penniman purchased at least eight gilt picture frames from Boston gilder John Doggett. The latter’s account books show that in return he received at least seventeen reverse glass–painted tablets from Penniman. The painter is not mentioned in subsequent entries, which suggests that he found another source for his frames. Penniman reputedly took instruction from Gilbert Stuart after the portraitist returned from England. Although there is no documentation for Penniman’s training, he clearly admired Stuart and named his first son Gilbert Stuart Penniman (1811–1812).[23]

Penniman’s oeuvre widened in the following years to include copies of portraits by artists such as Gerritt Schipper, classical and biblical scenes derived from printed sources, landscapes, and family groups. As Boston’s printing and publishing industry expanded to become the city’s fourth-largest employer by 1840, Penniman did paintings for engravings and lithographs (figs. 30, 31). One of his images, which served as the basis for a giant early sawmill blade, bears the pencil inscription “the first original Drawing on Stone, in the United States by / J. Pendleton Boston J. R. Penniman / 1826” (fig. 32). Penniman anticipated the importance of stone lithographic reproduction, which soon became dominant in printing. Like other Boston artists, he also produced paintings for patent applications, such as “Pianoforte in the shape of a Bentside Spinet,” possibly an invention of innovative Boston piano maker Alpheus Babcock (fig. 33).[24]

Penniman painted a variety of subjects in Milton. In one of his landscapes, he pictured that town’s most famous house, Unquety (Unquity) (fig. 34), originally the summer home of loyalist governor Thomas Hutchinson. The latter’s property was seized when he fled Massachusetts during the Revolutionary War and subsequently sold to James and Mercy Otis Warren. According to Milton historian Albert Teele, Penniman, with his plein air painter’s tools, accompanied Boston’s Light Infantry when it encamped on Hutchinson’s Field (then the pasture of wealthy Boston merchant Barney Smith who had since bought Unquity) opposite Unquity in 1827. The artist also appears to have painted name boards for pianos made by Benjamin Crehore, who lived on Adams Street just four houses down (fig. 35).[25]

In 1827 Penniman advertised that he was auctioning his stock-in-trade, tools, and art supplies and retiring to “follow his inclination in the higher branches of his art.” The sale also included his “Sportsman’s Basket containing a great variety of Marine Shells.” By the mid-1830s he had moved his studio to West Brookfield, Massachusetts, west of Boston, evidently to be near his or his wife’s family. His tendency to alcoholism had caught up to him. In the next few years, he apparently wandered the countryside soliciting work as a portrait and heraldic painter. Penniman’s portraits from the early 1830s may be his finest work, but he never became successful enough as a fine art painter to support himself exclusively with that prestigious and better-paid genre. Throughout his career, he was forced to fall back on decorative painting.[26]

It is hard to escape the conclusion that the greatest achievements in Penniman’s diverse career occurred during his collaboration with Thomas Seymour, James Cogswell, and Samuel Gragg (fig. 36). The Nichols pier table is a testament to his tremendous skill. The discovery of Penniman’s signature and date on that table should allow scholars to identify other examples of his work and significantly broaden the identifiable body of his oeuvre.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Carol Damon Andrews, Gavin Ashworth, Georgia Barnhill, David Bohl, Flavia Cigliano, Wendy Cooper, Stuart Feld, Paul Foley, Rebecca Garcia, Linda Kaufman, Alexandra Kirtley, Darcy Kuronen, Johanna McBrien, Bill Pear, Sumpter Priddy III, Albert Sack, Anthony Sammarco, John Stephens, Page Talbott, Gerald W. R. Ward, and Gregory Weidman.

The pencil inscription was discovered by furniture conservator Christopher Shelton when the table was in the studio of Robert Mussey Associates for conservation under a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Portions are extremely difficult to read, and some small areas are worn from abrasion. Infrared photography and manipulation of a mosaic of enlarged image sections with various filters and enhancements with Photoshop© software allowed us to transcribe most of the script. Enough of Penniman’s name remains to allow him to be clearly identified as the signer. Penniman frequently signed or initialed and often dated his paintings. His Portrait of a Man (Worcester Art Museum) is inscribed on the reverse “Painted by / John Ritto Penniman / Boston Jan.y 30 / 1804.”

For more on Boston-area painters, see Alice Knotts Cooney, “Ornamental Painting in Boston, 1790–1830” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1978). Among the artisans she identified were Daniel Bartling, Charles Bullard, Charles and William Codman, Robert Cowen, Benjamin B. Curtis, George Davidson, Samuel Gore, Charles Hubbard, Spencer Nolen, Rea & Johnston, and Aaron Willard Jr. Irving W. Lyon, The Colonial Furniture of New England (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1891), pp. 53, 110, as cited in Cooney, p. 10.

Columbian Centinel, February 23, 1805; April 13, 1807; December 5, 1810.

For the Finlays, see Gregory R. Weidman, Furniture in Maryland, 1740–1940: The Collection of the Maryland Historical Society (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1981), nos. 53–57, 122, 133, 134, 150, 171, 172; and Lance Humphries, “Furniture, Patronage, and Perception: The Morris Suite of Baltimore Painted Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 138–212. For the Waln furniture, see Jack Lindsey, “An Early Latrobe Furniture Commission,” Antiques 139, no. 1 (January 1991): 208–19. Beatrice B. Garvan first attributed the Waln furniture and woodwork to Bridport in Federal Philadelphia, 1785–1825: The Athens of the Western World (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), pp. 90–93. For more on Bridport, see Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “The Painted Furniture of Philadelphia: A Reappraisal,” Antiques 169, no. 5 (May 2006): 134–45. Columbian Centinel, December 19, 1807.

Immigrant painters include Robert Cowen, William Cunnington, George Graham, Francis Lloyd, John McDuell, James McGibbon, James Sharp, Joseph Stokes, William Tolman, and John Worrall. Painters possibly of British origin include Thomas Benson, William Bittle, Nathaniel Bodge, William Dearborn, and Samuel Hastings. The authors compiled these names from Boston tax assessors’ taking records, newspaper advertisements, Suffolk County Court dockets, and Paul J. Foley, Willard’s Patent Time Pieces: A History of the Weight-Driven Banjo Clock (Norwell, Mass.: Roxbury Village Publishing, 2002), pp. 178–98.

The authors thank Bill Pear and Flavia Cigliano for providing access to the Nichols House archives and collection. “Inventory of Furniture, Rugs, Paintings, Tapestries, Etc. / [Arthur] H. Nichols Boston 1906”; Inventory of the Nichols House prepared after his wife Elizabeth’s death in 1929; Inventory of the Nichols House prepared by Miss Rose Nichols, ca. 1930; Inventory of the Nichols House by Helen Homer, caretaker and wife of Rose’s executor, 1960. In this latter inventory, the table illustrated in fig. 1 is identified as “painted and stencil decorated Empire console table that once belonged to John Hancock.” Although the latter history is implausible because Hancock died in 1793, the table could have belonged to his widow, Dorothy (Quincy), and her second husband, Capt. James Scott, and sold at one of three sales of Hancock House objects. The drawings are included in White’s papers at the Winterthur Library and Museum. The authors thank Wendy Cooper for bringing these drawings to their attention. For more on White, see Rebecca Garcia, “Pigments and Pianos: Painter and Varnisher Lyman White” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2007). White became a member of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in 1837. His stencils, designs, sketches, and pricked patterns indicate he was a competent artisan, although his designs were occasionally mechanical and geometric; Garcia, “Pigments and Pianos,” p. 9.

Boston Tax Taking Records, Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Division. After circa 1817, ash began to appear as a secondary wood in the furniture of other leading craftsmen including (George) Archibald & (Thomas) Emmons and Isaac Vose. The mounting of the top assembly to the base assembly was modified somewhat during an earlier repair. The net effect was to lower the overall height of the top by 1". The reason for this change is not clear, but it resulted in making the signature more accessible to us once the top was unscrewed and removed.

Seymour’s copy of the Drawing-Book is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Carol Damon Andrews, “John Ritto Penniman, 1782–1842: An Ingenious Artist,” Antiques 120, no. 1 (July 1981): 159, pl. 10.

The top was overpainted in the nineteenth century, possibly by Lyman White. The restorer approximately replicated the original colors and striping pattern.

Furniture scholar Wendy Cooper first noticed that the painting on these chairs was similar to that on the Nichols House pier table and generously shared her research with the authors. Four chairs from this set are known. Israel Sack, Inc. sold them to a private collector who subsequently lent the chairs to the New York State Museum. Sack later bought back two examples from the set. One of the privately owned examples remains in the New York State Museum, and the other was donated to the Winterthur Museum. The chairs are cited in Israel Sack, Inc., American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 10 vols. (New York: Highland House, 1988), 7: 1818, no. 5011; 9: 2439, no. 5011; 10: 2705, no. 6341. Another chair with an upholstered seat is pictured in Kinnaman & Ramaeker’s advertisement in Antiques 78, no. 3 (March 1985): 506. The Winterthur chair is marked “I” on both the underside of the chair and on the caned seat frame and has “$6” written in pencil on the inner surface of the rear seat rail. The chair at the New York State Museum, which bears the inscription “Holdens,” is marked with “II” in the same locations as the numeric marks on the Winterthur chair. Both chairs are made of birch, a wood more commonly used in Boston than in New York.

Joshua Holden married Mary Armstrong Mitchell (1782–1863) on April 27, 1802, and died at Westminster, Vermont, on December 17, 1852. The authors thank John Scherer of the New York State Museum for this genealogical information. According to the 1850 census, Holden’s eldest son, Joshua, was a “painter” in Gardner, Massachusetts. Joshua Holden worked on Orange Street in Boston from 1813 to 1818. Tax assessments indicate that he occupied space in a building owned by cabinetmaker Isaac Vose. Holden employed several journeyman chair makers and chair painters. His tax valuations rose steadily, suggesting that he ran a successful shop; Boston Tax Taking Books, Ward 12, Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Holden was on Orange Street in 1821 and Washington Street after 1824; Page Talbott, “The Furniture Industry in Boston, 1810–1835” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1974), p. 213.

Columbian Centinel, July 31, 1805. Joseph Peabody receipt, private collection. Columbian Centinel, September 12, 1809.

Columbian Centinel, August 25, 1810. As quoted in Mabel Swan, “John Ritto Penniman,” Antiques 39, no. 5 (May 1941): 247.

Mabel Swan, “A Seymour Bill Discovered,” Antiques 51, no. 4 (April 1947): 244. The receipt is illustrated in Vernon Stoneman, John and Thomas Seymour: Cabinetmakers in Boston, 1794–1816 (Boston: Special Publications, 1959), p. 248, fig. 159.

Wendy A. Cooper, Paul Revere’s Boston, 1735–1818 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1975), p. 171, no. 207.

One dressing table is painted white, but the paint appears to be new, and the current location of the object is unknown; Dean A. Fales Jr., American Painted Furniture, 1660–1880 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972), p. 106, fig. 177. Other examples of the form have mahogany exteriors but with beautifully developed gilt leafage, scrollwork, and striping ornamenting the lyre supports for the mirrors. Dressing tables with gilt leafage on mirror brackets are in the collection of the Newark Museum and illustrated in Sack, Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 8: 2130, no. 5581. For a dressing table owned by the Peabody Essex Museum and two worktables, see Robert D. Mussey Jr., The Furniture Masterworks of John & Thomas Seymour (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Essex Museum, 2003), pp. 258, 314, 315, nos. 62, 90, 91. For the quartetto tables, see ibid., pp. 370–71, cat. no. 118, collection of Mrs. Linda Kaufman.

The table illustrated in fig. 24 may be the same example shown in Page Talbott, “Boston Empire Furniture, Part II,” Antiques 109, no. 5 (May 1976): 1004, fig. 1. Stephen Badlam, “Remarkable Occurrences,” private collection. This diary mentions the names of thirty-one of Badlam apprentices, including both of the Lothrops and John Doggett, and the dates of their terms. Eastern Argus (Portland, Maine), July 9, 1822, as cited in Andrews, “John Ritto Penniman,” p. 161, n. 19. The address was 73 Market Street at the “Sign of the Red Cross Knight directly over the Gilding Manufactory of Mr. Stillman Lothrop.” This article was republished with additional information and illustrations by the Worcester Art Museum in 1982. See also Carol Andrews, “The Penniman Coat-of-Arms Painted by John Ritto Penniman,” typescript, 2003, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston.

Gragg was a tenant in Thomas Seymour’s Boston furniture warehouse from 1808 to 1811; Boston Tax Taking Books, Boston Public Library. The former was listed in the 1801 tax records as “journeyman to Samuel Tuck,” who was one of Seymour’s business partners in the warehouse from 1804 to 1805; Mussey, Furniture Masterworks, p. 53. Several scholars have suggested that Penniman may have painted some Gragg chairs. See Michael Podmaniczky, “The Incredible Elastic Chairs of Samuel Gragg,” Antiques 163, no. 5 (May 2003): 138–45. Advertisements in the Columbian Centinel (Boston) indicate that white furniture became fashionable for parlors and bedchambers beginning circa 1805. In the April 22, 1807, edition of that paper, the “Broad-Street Cabinet and Chair Manufactory” advertised “White and Gilt fancy Chairs, with cane seats, very elegant.” Three years later (April 11, 1810) an auction at the house of “the late Charles Paine” included “white and gilt Settees and chairs.” The most detailed account of white-painted furniture was in the November 21, 1810, edition, which listed “articles of rich Furniture, viz. White and gilt Bedsteads, with Cornices to match; white and gilt Bureaus; do do Toilet Tables; do do Wash Stands; do do fancy Chairs, various patterns and fabrics. The above are painted by a finished workman.” Two years later (January 29, 1812), the paper reported on a sale featuring “white Bureaus,” presumably for a bedchamber. White and gilt fancy chairs were the most commonly advertised forms.

Foley, Willard’s Patent Time Pieces, p. 296. David Wood, “Concord, Massachusetts, Clockmakers, 1811–1831,” Antiques 159, no. 5 (May 2001): 762–69. All of the information on Penniman’s painted dials comes from Foley’s book or personal communication with him.

Foley, Willard’s Patent Time Pieces, pp. 178–79, 283–84, 300. This source lists Trescott incorrectly as Prescott.

Penniman’s first shop was next to Simon Willard’s (1803) and his second was at the rear of Aaron Willard’s; Andrews, “John Ritto Penniman,” p. 161 n. 18. The portrait is illustrated and discussed on p. 149, fig. 2.

John Doggett Account Books, Winterthur Library. Doggett had recently completed his apprenticeship with Stephen Badlam; Badlam, “Remarkable Occurrences.” Quoted in Andrews, “John Ritto Penniman,” from William Dunlap, The History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, 3 vols. (New York: George P. Scott, 1834), 2: 215. Andrews also cites James Flexner, Gilbert Stuart: A Great Life in Brief (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955), p. 165, who states that Penniman was Stuart’s favorite drapery painter.

The painting includes the anomalous image of a small fly, and its companion painting includes a spider. These are visual references to Mary Howitt’s 1829 poem “The Spider and the Fly.” The painting was reputedly found in the attic of a house built by Samuel Crehore on Adams Street in Milton. Samuel’s house was across the street from the shop and house of his brother Benjamin, a pianoforte maker.

Albert K. Teele, The History of Milton, Massachusetts, 1640–1887 (Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1887), pp. 134–44. The watercolor is executed on a fine French paper with floral embossed border and with French poetry quotations in the corners, each transcribed on the reverse in pencil; frame is not original. The house was destroyed in the 1950s.

Columbian Centinel, April 12, 1827. Andrews, “John Ritto Penniman,” p. 156.