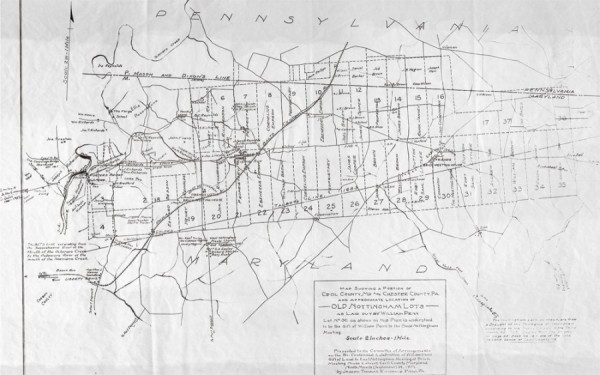

Map of Southeastern Pennsylvania, showing bounderies of Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey. (Artwork, Nichole Drgan.)

1901 reproduction of “A Draught of the Township of Nottingham according to a Survey made thereof in the third Month AD 1702.” (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society.)

Spice box, attributed to the shop of Thomas Coulson (1703–1763) and possibly to John Coulson (1737–1812), Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1740–1750. Walnut and red cedar, sumac, and holly inlay with white oak. H. 19 3/4", W. 16 1/4", D. 11". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

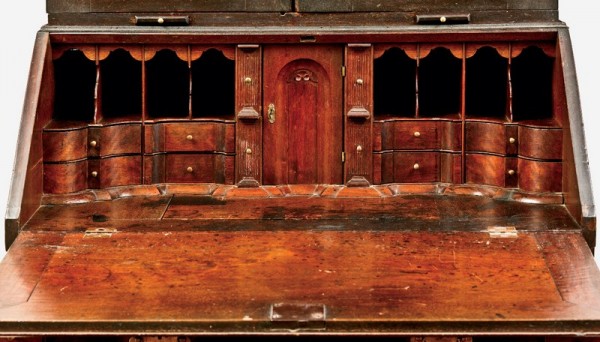

Desk attributed to Hugh Alexander (1724–1777), Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1745–1760. Walnut and red cedar, maple, holly and sumac inlay, with chestnut, tulip poplar, white cedar. H. 45 3/4", W. 39 1/8", D. 22 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The sides of the case extend down to form supports for the foot faces. This feature occurs on later desks from the Nottingham area (see figs. 36 and 37).

Desk, probably Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1740–1760. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 41 3/8", W. 40", D. 20 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A unique feature of this desk is the shallow secret drawer concealed by the medial molding above the small upper drawers.

Exterior of the John and George Churchman House, Rising Sun, Cecil County, Maryland, 1745 and 1785. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The three-bay stone addition was added to the west side in 1785.

Detail of the date stone on the Isaac and Mary Haines House, Rising Sun, Cecil County, Maryland, 1774. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of a built-in cupboard in the Isaac and Mary Haines House, Rising Sun, Cecil County, Maryland, 1774. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Corner cupboard, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1770–1800. (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)9

Detail of an interior doorway in the Isaac and Mary Haines House, Rising Sun, Cecil County, Maryland, 1774. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Corner cupboard, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, ca. 1770–1800. Walnut and lightwood inlay. H. 77 3/4", W. 43 1/2", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, gift of J. Gilman D'Arcy Paul, BMA 1970.45.3. Photo by Mitro Hood.) Since no early history of ownership survives for this cupboard, the possibility of extrapolating a name from the “IMW” initials on the upper door panel is remote.

Detail of the cornice of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of the right front foot of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 11. With its tall shallow cove and underscale ovolo, the base molding conforms to a common local pattern.

Clothespress, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar and maple. H. 85 5/8", W. 71 1/4", D. 25". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cornice of this press has Greek key and drilled dentil elements similar to those on the cupboard illustrated in figs. 11 and 12.

Detail of the right front foot of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 14. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

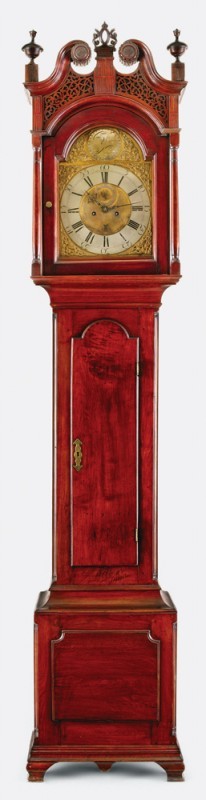

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1775. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 107", W. 22 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The carved appliqués on the plinth are rabbeted to overlap the square corners of the base panel, presumably to allow for seasonal shrinkage and expansion. The feet and base molding are restored.

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1775. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 99", W. 21 3/4", D. 12 1/4". (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The clock was photographed in the house of Susanna Brinton of Gap, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, before 1924. By that date the upper portion of the sarcophagus top had been removed. The short cabriole legs are visible in that image.

Susanna Brinton, Three Spring Farm, Leacock Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1855. Drawing on prepared tinted drawing paper. 9" x 11 3/4". (Courtesy, LancasterHistory,org, Heritage Center Collection (; photo, Leigh Mackow.) Susanna (1833–1927) was Moses Brinton’s great-granddaughter and the last family member to live in his home.

Detail of the left front foot of the clock illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the hood of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of a chalk sketch inside the clock illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1750–1775. Walnut with white pine. H. 103 1/4", W. 20 7/8", D. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the plinth panel of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

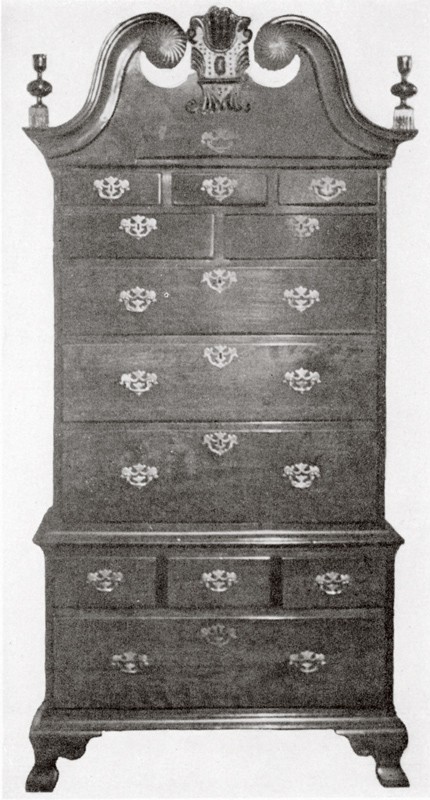

High chest of drawers, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1780. Walnut with tulip poplar, hard pine, white cedar. H. 92 3/4", W. 43 1/2", D. 25". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The pediment scrolls on this chest have a more exaggerated S-curve than those on the example illustrated in fig. 25, but both sets of moldings have oversize volutes with identical appliqués. Similar volutes occur on other furniture from the Nottingham area.

High chest of drawers, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1780. Walnut with tulip poplar and oak. H. 95 3/8", W. 43 3/4", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Jeffrey Tillou.) The center ornament is not original.

Detail of the pediment of the high chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of a stair bracket in the Isaac and Mary Haines House, Rising Sun, Cecil County, Maryland, 1774. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Cartouche attributed to the Garvan high chest carver, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Dressing table, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1780. Woods and dimensions not recorded, location unknown. (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques, Inc.)

Detail of the plinth of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of a chalk sketch in the high chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the leg carving on the high chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

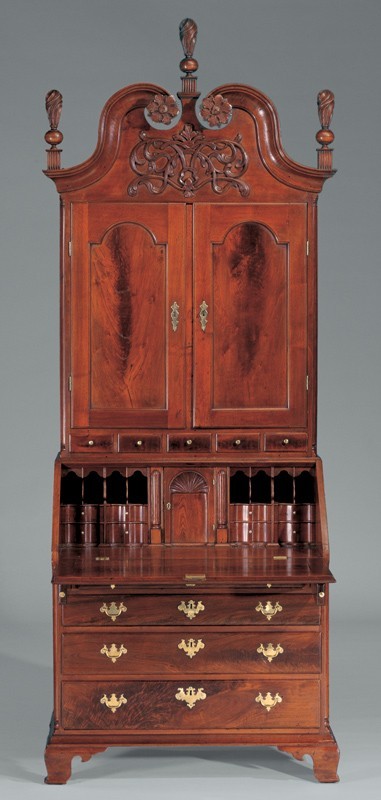

Desk-and-bookcase, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1780. Walnut with tulip poplar, white oak, white cedar. H. 96 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This rosette pattern occurs on one other case piece from the Nottingham area (see figs. 53, 54).

Detail of the right front foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker drilled out the circular piercing in the feet. Marks from the wing cutter of the bit are visible on the inner edge.

Desk, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1770–1800. Walnut with oak, chestnut, and tulip poplar. H. 47", W. 43", D. 22 7/8". (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The drawers that support the fallboard have appliqués with convex spiraling like that on the rosettes of the high chests illustrated in figs. 24 and 25 and chest-on-chests shown in figs. 42 and 43.

Desk, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1770–1800. Walnut with oak, chestnut, and tulip poplar. H. 45 1/2", W. 42", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right front foot of the desk illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

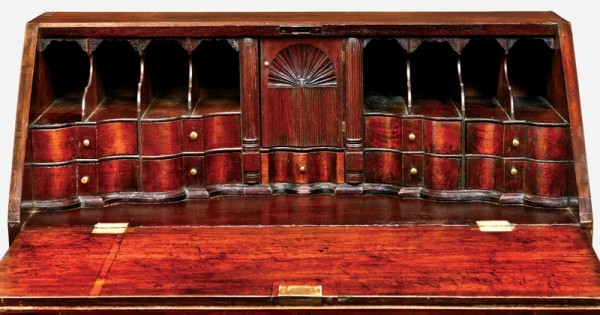

Detail of the prospect door and document drawers in the writing compartment of the desk illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carving on the prospect door is stylistically related to that on the ornament of the Coudon desk (fig. 33). Most desks from the Nottingham area have document drawers with fluted faces.

Desk-and-bookcase, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1770–1790. Walnut with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 102 3/4$", W. 37", D. 24". (Courtesy, Sumpter Priddy Antiques.)

Chest-on-chest, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1780. (Antiques 41, no. 1 [January 1942]: 8.) The cartouche on this example is similar to that on the Coudon desk-and-bookcase, with the exception of having gouge work on the flat surfaces around the cabachon.

Chest-on-chest, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1760–1790. Walnut with white oak and tulip poplar. H. 90 1/2", W. 43", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.) The feet and base moldings are integral.

Detail of the upper carved drawer of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 43. No other work by this carver has been identified.

Chest-on-chest with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1800. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 97", W. 42 1/2", D. 24". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a Dutchman on the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 43. Dovetail layout lines scribed across the Dutchman prove those components were part the original construction.

Chest-on-chest, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1770–1800. Walnut with oak and tulip poplar. H. 87 3/4", W. 46 1/8", D. 24 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest-on-chest and the chest illustrated in fig. 48 are made of water mill–sawn boards just over one inch in thickness. The oak backboards of the chest-on-chest are original, but extraneous nail holes and remnants of plaster suggest they are reused architectural components. The sides of the chest-on-chest are paneled, a feature occurring on other case pieces from the Nottingham area. The molding on the face of the thin upper drawer differs from that of the example illustrated in fig. 48. Chests with an upper row of three arches are relatively common in Chester County, particularly the areas around New Garden, London Grove, West Fallowfield, and West Marlborough Township.

Tall chest of drawers, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1770–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 69 1/4", W. 44", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cornice fret is similar to those on tall-clock cases from the Nottingham area.

Detail of the left front foot and base molding of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet and base moldings are integral.

Detail of the right front foot and base molding of the tall chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet and base moldings are integral.

Chest-on-chest, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar and white oak. H. 100 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The backboards of the pediment are joined with Dutchmen like the side and top boards of the chest-on-chest illustrated in figs. 43, 44, and 46.

Detail of the pediment of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, or Cecil County, Maryland, 1765–1790. Walnut with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 96 1/8", W. 21 1/2", D. 10 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hood of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., and case by Jacob Brown, Nottingham area, Cecil County, Maryland, 1788. Walnut with tulip poplar and hard pine. H. 107 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The sides of the plinth extend to the floor to support the case and feet, which are integral with the base molding.

Detail of the hood and movement of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The rosettes, which are similar to those on other locally made pieces, have stippling in the concave areas. The latter technique is repeated on the drawer shells of the chest-on-chest illustrated in figs. 43 and 44. Although the fabric behind the spandrel fret is replaced, evidence of the original textile survives.

Detail of the plinth of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., case attributed to Jacob Brown, Nottingham area, Cecil County, Maryland, 1780–1802. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 99 3/8", W. 22 1/4", D. 12 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Details shared by this clock case and the McDowell example (figs. 55 and 56) include spiral rosettes, a corbel on the plinth of the tympanum, drilled dentil molding, and gouge-carved plaques above the colonnettes.

Detail of the hood, movement, and secret drawer of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 58. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) No other American clock with a secret drawer is known.

Tall-case clock with movement by Ellis Chandlee (1755–1816), case attributed Jacob Brown (d. 1802) or William Brown (d. 182?), Cecil County, Maryland, 1800–1815. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 94", W. 21", D. 11". (Private collection; photo, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

Detail of the hood and movement of the tall-case clock illustrated in fig. 60.

For decades furniture collectors and dealers have used the word “Octoraro” to describe several distinctive groups of furniture made in southern Chester County, Pennsylvania, and northern Cecil County, Maryland, in the vicinity of the Octoraro Creek. The broad eastern branch of this creek forms the boundary between southern Chester County and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, continuing south into Maryland (fig. 1). One group, comprising various case forms, is distinguished by the use of ogee feet with bracket cusps that scroll around to form a circle or stop just short of a circle. Another group, largely consisting of high chests, has short cabriole legs dovetailed to battens that attach to the case bottom with large wooden screws. However, to date this latter group cannot be firmly associated with the Nottingham area through any well-documented examples. Research by the authors has identified many additional structural and stylistic features used by cabinetmakers and house joiners working in this area, which was settled primarily by English Quakers and Scots-Irish Presbyterians.[1]

Early Settlement

Part of William Penn’s original land grant, the southernmost portion of Chester County was noted by the late seventeenth century for its valuable natural resources. Soils were fertile, timber of all sorts was abundant, and numerous rivers and creeks provided transportation and power for saw mills, gristmills, and other industrial enterprises. However, in 1680 Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore, gave his nephew George Talbot “Susquehanna Manor,” a thirty-two-thousand-acre tract that extended from the Susquehanna River to the Delaware River and included a portion of southern Chester County, which gave rise to disputes that continued for the next eighty years.

In early 1701 a small group of Quakers from the settlement of New Castle on the Delaware River (then part of Penn’s lands) moved to the rich watershed of the Octoraro Creek and the North East River. At a meeting of the Commissioners of Property in Philadelphia, Cornelius Emerson represented “twenty families, chiefly of the county of Chester” in requesting twenty thousand acres “to make a Settlmt. on a tract of land about half-way between Delaware and Susquehannough, . . . on Otteraroe river.” The following year the commissioners granted the families an eighteen-thousand-acre tract “between the main branch of the North East river and Octorara creek.” The tract was quickly surveyed and divided into thirty-seven parcels, each containing a little less than five hundred acres. Those desiring to purchase land drew lots, which resulted in the entire area being called Nottingham Lots (after Penn’s birthplace) (fig. 2). This grant was a clever move on the part of the commissioners, for it secured the southern boundary of Pennsylvania for more than sixty years. Both Quakers and Scots-Irish Presbyterians were encouraged to settle there. By 1709 the Quakers built their first meetinghouse, presumably of logs. In 1724 that structure was replaced with a brick meetinghouse that became known as the Brick Meeting in East Nottingham Township. The same year the New Castle Presbytery directed two pastors to serve the Nottingham community, thus accommodating the Scots-Irish settlers. Among the first families who settled there were Browns, Englands, Chandlees, Churchmans, Haineses, Gatchels, and Kirks.[2]

Between 1701 and the early 1760s the boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland was constantly in dispute, which resulted in angry battles and occasional bloodshed among the inhabitants. It was not until 1763 that the proprietors of both colonies petitioned the Royal Astronomer at Greenwich, England, for help with a new survey. Anglican Charles Mason (1738–1786) and Quaker Jeremiah Dixon (1733–1779) arrived in America on November of that year and spent fifty-eight months establishing boundaries between Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Although the line they drew determined that approximately 16,700 acres of the Nottingham Lots were in northern Maryland, the inhabitants were culturally and religiously more closely linked to Philadelphia than to any other commercial or style center. Some of the objects discussed in this article were undoubtedly made in Cecil County, Maryland, but most craftsmen from the Nottingham area drew their inspiration from Philadelphia styles during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[3]

Seminal Clockmaking and Cabinetmaking Traditions

The sophistication of furniture made in the Nottingham area in the second half of the eighteenth century is best understood against the backdrop of earlier craftsmanship. Members of the Chandlee family of clockmakers were among the earliest artisans to settle on the Nottingham Lots. Benjamin Chandlee (1685–1745) emigrated from County Kildare, Ireland, in 1702, apprenticed with Philadelphia watchmaker Abel Cottey, and married his master’s daughter Sarah in 1710. Following Abel’s death in 1712, Benjamin, Sarah, and her mother, Mary, moved to Nottingham Lot number fifteen, which Cottey had purchased in 1706. Chandlee trained his fifth child, Benjamin Jr. (1723–1791), in the clock and instrument making trade, and Benjamin Jr. worked with his father until 1741, when Benjamin Sr. and his wife sold their property and moved to Wilmington, Delaware. At that date Benjamin Jr. and his brothers, Cottey and William, moved to Nottingham Lot number thirty, which their grandfather had purchased in 1703.[4]

Although none of the artisans who made cases for Chandlee movements before the late 1780s has been identified, several pieces of furniture can be attributed to early Nottingham makers. A spice box with line-and-berry inlay and distinctive herringbone banding is attributed to the shop of Thomas Coulson (1703–1763), who emigrated from Derbyshire, England, probably before his marriage to Mary Wiley in 1725 (fig. 3). The box descended in the Hartshorn (Hartshorne) family of West Nottingham and bears the partial signature of Coulson’s son John (1737–1812). When Thomas died in 1763, he left John all his “Utensils of Husbandry,” two horses, two cows, and half of his joiner’s tools.[5]

Two desks attributed to Scots-Irish cabinetmaker Hugh Alexander (1724–1777) also attest to the high level of workmanship available in the Nottingham area (fig. 4). These pieces have complex interiors with numerous secret drawers and line-and-berry inlay and herringbone banding on the exterior drawers. In October 1757 a man named James Brown bound his son William to Alexander for eighteen months “to learn the Arts, Trades or Mysteries of a Carpenter & Wheel Wright.” Since Brown was one of the most common names in Nottingham, it is difficult to determine exactly who these men were. A plain walnut desk with an interior similar to the two attributed to Alexander is inscribed “James Brown” in chalk on the bottom of a valance drawer, but it is unknown whether this James was a maker or an owner, or possibly the father of Alexander’s apprentice William Brown (fig. 5). The cleverly concealed drawer in the medial molding of this desk is consistent with Nottingham makers’ penchant for hidden and unusual drawers.[6]

Architectural Contexts and Connections

Architecture in the Nottingham area was strongly influenced by Philadelphia styles. By the second quarter of the eighteenth century, stone and brick had replaced logs as the preferred building materials. Architectural features like glazed brick dates, date stones, pent roofs, and second-storey doors and balconies became hallmarks of sophistication. Among the most aspiring examples of extant early Nottingham architecture are houses built by Quakers William Knight (1745), Mercer Brown (1746), Jeremiah Brown (1757), and John (1745) and George Churchman (1785) (fig. 6). The interior woodwork and built-in furniture in all these houses has precedent in classical architecture, but local characteristics are apparent in the form and detail of paneled doors, stair brackets, keystones, and moldings.[7]

The three-bay stone house of Isaac and Mary Haines is distinguished by its deep, pent eaves and a 1774 date stone with two intertwined hearts and the initials “I H M” (fig. 7). The built-in cupboard in the main parlor has a distinctive keystone-shaped upper panel, a local variant on an arch-headed tombstone panel (fig. 8). The proportions of the cupboard are also unusual, owing to the upper section being almost twice as high as the lower—a proportional arrangement similar to that on certain freestanding furniture forms from the region. Another built-in cupboard, likely by the same maker, was removed from an unidentified house in the Nottingham area during the 1970s (fig. 9). The paint on that object is modern, although based on remnants of the original blue. The keystone device in these cupboard panels may have classical precedents, as seen in the arched cornice above a door in the Haines House and a number of other buildings in the Nottingham area (fig. 10).[8]

As was the case in many rural areas, house joiners occasionally made freestanding furniture, and cabinetmakers periodically received commissions for architectural work. The corner cupboard illustrated in figure 11 has an upper keystone panel almost identical to those on the preceding examples (figs. 8, 9), suggesting that the same person may have made them all, whether he was a cabinetmaker, a house joiner, or both. Additionally, the cupboard has an elaborate cornice featuring Greek key and drilled dentil moldings and a guilloche fret (fig. 12)—details that occur on other locally made case pieces and architectural components. The lower part of the feet on the cupboard are restored, but the bracket cusps survive and are articulated with a shallow drilled hole (fig. 13). On other Nottingham-area case pieces, like the massive clothespress illustrated in figure 14, the cusps were either drilled all the way through or the cusps were sawn and finished with gouges and files (fig. 15).[9]

The Nottingham School and Philadelphia Influence

Furniture made in the Nottingham area was strongly influenced by contemporaneous Philadelphia work. The career of Quaker “shop joyner” John Mears (1737–1819) offers one possible path of stylistic transfer. The son of William Mears “late of Georgia, deceased,” John may have served his apprenticeship in Philadelphia before 1760, when he married Susanna Townsend. Among the Quakers who witnessed their marriage were cabinetmakers Solomon Fussell, William Savery, Jacob Shoemaker, Samuel Mickle, and Thomas Sugars, suggesting that Mears had apprenticed with one of these men or was working with them. Susanna’s parents, Charles and Abigail, moved to Nottingham in 1766, and she and John received their transfer to the Nottingham Monthly Meeting the following year. Mears’s name appears on the Nottingham tax list in 1768, and in 1767–1768 and 1773 he made furniture for noted Lancaster lawyer Jasper Yeates. In 1767 Yeates paid Mears £8 for a walnut bookcase and walnut “Dressing Drawers.” The following year Mears supplied Yeates with a walnut dining table, a small walnut corner(?) table, a plain card table, and an “Elbow Chair.” He later worked in Reading, Berks County, and eventually was among the first settlers in Catawissa, Columbia County. Mears was no doubt familiar with Philadelphia stylistic details and may have introduced them to the Nottingham area.[10]

One group of closely related Nottingham furniture has distinctive Philadelphia-inspired features and consists of two tall-case clocks, two high chests of drawers, a matching dressing table, and a desk-and-bookcase (figs. 16, 17, 24, 25, 29, 33). Both clocks have movements by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. and histories of ownership confirming that their cases were made locally. The original owners’ ages and marriage dates suggest that the clocks date between 1760 and 1775.

According to family history, Rowland (Roland) Rogers (1717–1787) of West Nottingham commissioned the clock illustrated in figure 16. He married Rachel Oldham circa 1760. Judging from Rogers’s will, he owned a considerable amount of land. When he died in 1787, much of his estate—presumably including his clock—passed to his eldest son, Elisha, who received “all that Part of my Plantation I now live upon.” Moses Brinton (1725–1789), born in Thornbury Township, Chester County, was the original owner of the other clock (fig. 17). In 1747 he married Elinor Varman (Varmon) (1724–1788) at Leacock Meeting in Lancaster County, and in 1748 his father gave him two hundred acres in Leacock Township. In 1761 the couple built presumably their second house on land given them by Elinor’s father (fig. 18). Although the precise date when they purchased the clock is unknown, it is mentioned in Moses’s will. He left his son Joseph (1754–1809) the plantation on which he lived along with his “Eight Day Clock, Desk, & the Sum of twenty five Pounds together with one . . . third Part of my Mechanical or Carpenter Tools.”[11]

Moses Brinton was connected to Nottingham through several marriages. His mother was a Pierce, and his maternal grandmother was a Gainer, both surnames common in that area. The most direct link was through Moses’s father, Joseph, whose second marriage was to Mary Elgar, widow of Joseph Elgar, at the East Nottingham Meeting in 1748. Witnesses at this marriage included members of the Churchman, Chandlee, Pierce, and Brown families. An important additional bond to the Nottingham area was through Mary’s daughter, who also in 1748 married William Chandlee, brother of clockmaker Benjamin Jr.[12]

The Rogers and Brinton clock cases share numerous structural and stylistic details (figs. 16, 17). Both have similar cornice, arch, and waist moldings, engaged quarter-columns that are not fluted, and a medial groove on the face of the hood door. The Brinton example retains its original cabriole legs and claw-and-ball feet (fig. 19), a detail rarely encountered on colonial American clock cases. A square tenon is integral with the head of the cabriole foot. On the front feet this tenon simply fits into the square pocket left behind the base molding when the quarter-column plinth stock stops short. On the rear feet the tenon fits into a pocket created by notching the side board behind the base molding. Although the feet of the Rogers clock are replaced, there is no reason to doubt that the originals differed from those on the Brinton case.[13]

Other clock cases from the Nottingham area survive, but none is as elaborate as the Rogers and Brinton examples. The Rogers case has carved appliqués on the tympanum and hood spandrels (fig. 20), above the waist door, and at the corners of the base panel (fig. 16). On the Brinton clock, the maker used fretwork in place of the tympanum and spandrel appliqués and omitted the ornament above the waist door (fig. 17). The carving on these cases is distinctive in that it has leaves with raised outer edges and broad, concave depressions in the center (fig. 20). To produce this effect, the carver used gouges to make deep, hollowing cuts—an idiosyncratic technique not usually associated with urban work. In addition to foliate motifs, this artisan’s vocabulary included scrolls, fluted corbels, flower heads, shells, and fanlike devices. Chalk sketches inside the hood of the Rogers clock indicate that the carver worked out some of his designs freehand rather than transferring them with patterns (fig. 21).[14]

Another case with a movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. has a closed ogee cornice that is stylistically earlier than the broken-scroll variants on the Rogers and Brinton clocks (fig. 22). The hood of this case is further distinguished by having a corbel-shaped keystone, a central fluted pilaster interrupted by a large ovolo-shaped element and capped with a standard plinth and ball-and-spire finials. The colonnettes are not fluted, but they display slight entasis and have small rings below the capital molding. Similar rings also occur on the waist and plinth columns. The most noteworthy feature of this case is its deeply fielded and carved plinth panel (fig. 23). As the cupboards illustrated in figures 8, 9, and 11 suggest, unconventional panel designs are common on furniture and interior architecture details from the Nottingham area.

Two high chests of drawers and a dressing table have carving closely related to and possibly by the same hand as that on the Rogers and Brinton clocks. The high chest illustrated in figure 24 descended in the family of Wilmington, Delaware, physician Dr. James Avery Draper (1835–1907). When his daughter Cornelia died in 1942, her inventory listed “1 Highboy in walnut, Chippendale” valued at $100.00 and “1 Walnut Low Boy, Chippendale” valued at $75.00. There is no evidence that the Drapers were connected to Nottingham, but it is possible that they may have acquired the high chest and dressing table from Wilmington friends or neighbors. For instance, Margaret Churchman Painter Pyle (1828–1885), mother of illustrator Howard Pyle, was a neighbor and patient of Dr. Draper and a descendant of John and George Churchman of Nottingham. The other high chest has no family history but was in Port Deposit, Cecil County, Maryland, in the late nineteenth century (fig. 25).[15]

Both high chests have extremely tall upper cases with bold broken scroll pediments and a shallow drawer in the tympanum (figs. 24-26). The pronounced cusps on the skirt of the high chest and dressing table (figs. 24, 29)—missing on the high chest illustrated in figure 25—are similar to those on the stair brackets of the Haines House (fig. 27). On the Draper example, the pediment is detachable, but on the other high chest it is integral. Despite these differences, it is obvious that the two high chests are from the same shop. Their cabriole legs were laid out with the same patterns, and their two-part waist moldings (small molding, deep cove, ovolo, and cyma attached to the upper case, and shallow cove and small molding attached to the lower case) are identical. The Draper high chest retains its original cartouche, which was likely inspired by Philadelphia examples (figs. 26, 28). The cartouche is not laminated for thickness, like many of its urban counterparts, but does have leaf clusters nailed into notches at either side. This allowed the maker to cut his cartouche from a narrower board, a material- and labor-saving technique duplicated on the skirt appliqués of both high chests and the dressing table (figs. 24, 25, 29) and related to the fabrication and carving of the plinth panels on the Rogers and Brinton clock cases (fig. 30). As on the Rogers clock, the carver of the Draper chest sketched designs on interior surfaces of that object. There is a rudimentary drawing of a cartouche on the rear top board of the lower case (fig. 31).[16]

The design of the high chests and dressing table is primarily frontal, as indicated by the exposed framing of the pediments and orientation of the carving. On all three pieces, the rear legs and sides of the front legs are unadorned (fig. 32). Contemporaneous Philadelphia case pieces occasionally have rear legs that are plain or carved only on the sides, but there is no urban precedent for the treatment of the front legs in this Nottingham group.

A desk-and-bookcase likely commissioned by educator and Anglican clergyman Joseph Coudon (Cowden) (1742 –1792) represents a different stylistic interpretation for furniture from the Nottingham area (fig. 33). Although the design of its cartouche is unique (fig. 34), the scroll volutes extending horizontally from the shoulders are applied in a manner similar to the leaf clusters on the aforementioned skirt appliqués (figs. 24, 25, 29) and cartouche of the Draper high chest (fig. 26). The stylized leaves on the tympanum of the desk-and-bookcase also relate to other Nottingham work in having deeply fluted lobes with thin, high ridges (fig. 20). However, the carving on the Coudon example lacks the foliate gouge carving seen on the previously discussed group of clock cases, high chests, and dressing table.[17]

Of all the case pieces from the Nottingham area, the Coudon desk-and-bookcase is the most architectural. Monuments and overmantels with similarly shaped tops and bold applied moldings appear in numerous eighteenth-century design books, including Batty Langley’s The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1st ed., 1740). At least nine copies of that book were in Philadelphia during the eighteenth century. Similarly, plate 3 in Abraham Swan’s The British Architect (1st ed., 1745) illustrates a Greek key as the lowest element in a cornice molding. This detail occurs on a number of case pieces from the Nottingham area but is relatively rare in furniture made elsewhere.[18]

The Coudon desk-and-bookcase rests on ogee feet with the standard profiles seen on other Nottingham-area pieces. The outer edge is a conventional ogee, but the inner face has an exaggerated drilled cusp that nearly touches the other side and points toward a small fillet above (fig. 35). A small fillet appears in almost the same position on the stair brackets from the Haines House (fig. 27). On most objects with this foot design, the sides of the case extend to the floor and act as supports, and the desks illustrated in figures 36 and 37 share that detail. The latter desk has a history of descent in the Reynolds and Barclay families of Rising Sun in Cecil County, Maryland. As was the case with the feet on the Coudon desk-and-bookcase, the maker of the desk illustrated in figure 36 used a drill to define the inner edge of the cusps (fig. 38). On the desk feet, the tips of the cusps are integral with a cyma-shaped element of the bracket rather than being separate and more fully defined (fig. 35). The desk illustrated in figure 37 has another foot variant typical of the Nottingham region.[19]

All these desks have a central prospect door with flanking letter drawers and tiers of drawers surmounted by pigeonholes with valances on either side, but no interiors from this region are identical. The Coudon interior is the most elaborate and individualistic, featuring a well, serpentine blocked drawers in the outer tiers, concave blocked drawers in the inner tiers, and four document drawers (one stacked over the other at each side) with moldings and reeded fluting simulating pilasters (fig. 39). The prospect door of the desk illustrated in figure 37 is unique in having a reeded, serpentine section surmounted by a lobed shell; additionally, the document drawers depart from local convention in having applied, reeded columns that are rounded at the top (fig. 40). The presence of similar columns on the document drawers of a Lancaster County desk-and-bookcase suggests that craftsmen or furniture from that town may have influenced production in the Nottingham area, or perhaps John Mears took this creative approach to Lancaster from Nottingham (fig. 41).[20]

Other structural and stylistic details typical of Nottingham-area furniture can be observed on four chest-on-chests. All have upper cases that are unusually tall in relation to their lower sections, and the one in figure 42 has an ornament likely carved by the hand responsible for the Coudon example (figs. 33, 34). This chest-on-chest also has a broken-scroll pediment with spiral-carved rosettes like those on other pieces from the region (figs. 24, 25) and a narrow drawer in the tympanum similar to the one in the high chest illustrated in figure 25. Unfortunately, the location of this piece is unknown, and the only existing image of it was so poorly silhouetted that it is impossible to determine if the feet are original and represent a common local pattern.

Another chest-on-chest has similar proportions, moldings, and pinwheel rosettes but different drawer organization (fig. 43). With three carved shells and two sets of idiosyncratic foliate appliqués, this object is one of the more highly embellished case pieces from the Nottingham area (fig. 44). Although no other example has comparable appliqués, the stippled grounds of the drawer shells and placement of the examples in the upper case have precedents in Philadelphia and Lancaster work (fig. 45). Several construction details on this chest-on-chest also occur on other locally made case pieces. The waist molding is virtually identical to that on the cabriole leg high chests illustrated in figures 24 and 25, and the feet are supported by extensions of the case sides. The case sides and top are joined with dovetail splines, or Dutchmen (fig. 46). Although normally used for repairs or later reinforcements, Dutchmen are original features on many examples of Nottingham-area furniture.[21]

A chest-on-chest and related tall chest of drawers have additional features associated with Nottingham-area work (figs. 47, 48), the most distinctive being long, thin drawers below the cornice. Like the preceding chest-on-chest, this example (fig. 47) has a tall upper case and lower section that is proportionally fairly short. The cornice features a Greek key molding like those seen on the corner cupboard and clothespress illustrated in figures 11 and 14, as well as the upper case of a related chest-on-chest (not illustrated). The feet of the chest-on-chest and tall chest of drawers represent other Nottingham-area variants. They are relatively tall, but the feet of the chest-on-chest have brackets that are drilled through, whereas those on the tall chest of drawers are not, similar instead to those on the desk illustrated in figure 37 (figs. 49, 50). As is expected of furniture from this region, the case and feet are supported by extensions of the sides. Another chest-on-chest combines details found on the preceding pieces, including fretwork and a shallow molded drawer (fig. 51). The applied molding outlining the tympanum and stop fluting of the keystone are unusual features (fig. 52), although keystones with different decorative treatments are common on clock cases and interior details from the region.[22]

A keystone with interrupted fluting graces the tympanum of a tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. (figs. 53, 54). This detail relates stylistically to the reeded fluting on the document drawers of the Hugh Alexander desk (fig. 4) and Coudon desk-and-bookcase (fig. 39). Other features linking the clock case and Coudon desk-and-bookcase are the boldly reeded edges of their scroll volutes and applied rosettes.

Several design elements on the chest-on-chest and the tall clock case have parallels in clock cases attributed to the shop of Quaker Jacob Brown (1746–1802), a West Nottingham joiner. Almost all of the movements found in Brown’s cases are by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. or his sons, Ellis (1755–1816) and Isaac (1760–1813). One case, likely also from the Brown shop, has a movement by Duncan Beard of Appoquinimink, Delaware.[23]

The Shop Tradition of Jacob Brown

Jacob Brown’s trade has been known for approximately twenty-five years, owing to the publication of a tall-clock case he made in 1788 for James McDowell (1742–1815) of Lower Oxford Township in southern Chester County (figs. 55, 56). Exactly when McDowell commissioned the clock movement and case is unknown, but on August 11, 1788, Chandlee had completed his part and wrote to McDowell:

I should take it very kind, if thee would please to send me the price of the Clock, by Stephen Yarnall, as I have some money to make up this week, & that makes me stand in Very great need of it, I am Sorry I have to trouble thee so soon for it, but it is not in my pwer to make out without it., please to inform me when thee expects the case home, & I will Come up & sett up the Clock.

Two months later McDowell received a letter from Brown apologizing for his delay in completing the case:

Friend James Mc Dowel I am Sorry That I have Disapointed you So much About your Clock Case if I had thought I Could knot Served you Beter I would knot under took for to have Done it I am Sorry for to inform you that 3 of my Boys have all got the feaver and cant Work one Stroke for me and 3 of my own Chil Dren is onwell Likewise But we will Lay all those maters aside If I keep my own health you Shall Have your Clock Case Some Day Next Week from your Disapointed friend to Serve[24]

Scholars originally believed that Jacob Brown the joiner was born in 1724, but that would have made him sixty-eight and the father of three young children when he wrote McDowell in 1788. A more likely candidate is the Jacob Brown who was born in 1746 and died in Cecil County, Maryland, in 1802 and whose estate inventory identified him as a joiner and listed unfinished furniture, woodworking tools, “291 feet of cherrytree plank,” “931 feet of walnut plank,” and “375 feet of 1/2 inch walnut.”[25]

Less than three weeks after Brown’s death, his widow Elizabeth and son William sold all Jacob’s personal property to “pay off the before mentioned Legacies” (see appendix). Among the “goods and chattels” were unfinished furniture and piecework, including several sets of table legs, a walnut chest, a cherry corner cupboard, two heads for bookcases, two table frames, and three clock cases. Samuel Cother, John Porter, and William Graham bought woodworking tools, cherry and walnut lumber, and unfinished furniture, which suggests they were either journeymen in Brown’s shop or established local joiners. Family members also bought much of the stock-in-trade, indicating that they intended continuing Jacob’s business, which apparently also included undertaking. Elizabeth purchased her husband’s hearse, along with the unfinished table frames and clock cases. Presumably she acquired the furniture for one of her sons to complete. As Jacob’s executor, William was undoubtedly old enough to take over his father’s business. Probably the younger Brown trained with his father along with other siblings and apprentices.[26]

The design and construction of the clock case that Jacob Brown made for McDowell indicate that he was one of the Nottingham area’s most creative and capable joiners. The hood is capped with a graceful, broken-scroll pediment with drilled dentil moldings; a carved, keystone-shaped appliqué on the tympanum; spiral rosettes with a pronounced central button; and a center plinth with an applied, reeded corbel surmounted by a Greek key. The turned and uniquely carved finials (two of which are original) represent a creative alternative to the standard ball and sphere form. Parallels with other Nottingham pieces can be seen in the fret under the hood (fig. 56), which is similar to that on the tall chest and chest-on-chest illustrated in figures 48 and 51, and the design of the base plinth (fig. 57), which has clear antecedents in the Rogers and Brinton clock cases (figs. 16, 17, 30). Another closely related clock case with a movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. has a similar plinth, frieze fret, keystone surmounted by a reeded corbel, and spiral rosettes but differs from the McDowell example in having a hood that is more typical of those with arched dials and broken-scroll pediments (fig. 58). A unique feature in the hood is the reeded corbel that is the face of a diminutive drawer, exactly large enough to conceal the key to the case (fig. 59).[27]

Jacob Brown, his son William (d. 1826), or other craftsmen trained in his shop were probably responsible for numerous tall clock cases that housed movements not only by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. but also by his sons Ellis and Isaac, all working in Nottingham. Many of these cases are simpler in design but continue to employ a central fluted keystone and spiral-carved rosettes. The top edge of their plinths echoes the shape of the door, and many have white-dial movements. A particularly refined example from this group has a movement by Ellis Chandlee (figs. 60, 61).[28]

Conclusion

Closely reliant on architectural traditions, Nottingham-area joiners and cabinetmakers creatively employed a variety of stylistic motifs influenced by Philadelphia design. This is most evident in a small pre-Revolutionary group of clocks and high chests with monumental proportions and distinctive carving. A group of desks, tall chests of drawers, chest-on-chests, and clock cases share similar construction techniques (full-height sides and the use of Dutchmen) while using various ornamental details such as fretwork, Greek key moldings, drilled dentil moldings, spiral-carved rosettes, and central keystone motifs. Secret and unusual drawers are also a mark of the creativity in this artisanal community. Almost all the casework features extra thick boards, often highly figured walnut, resulting in massively built pieces. The variety of ogee bracket feet with pronounced cusps—sometimes closed and occasionally blind—is a prominent feature of this regional group. The most characteristic hallmark of this work is the originality with which makers mixed and matched ornament, never exactly repeating a form or combination of details. The shop of Jacob Brown (1746–1802) and his followers was likely responsible for many of the later clock cases and possibly some of the other casework.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following colleagues and friends for their invaluable assistance with this article: Mr. and Mrs. Steve Adams, Alan Andersen, Gavin Ashworth, Joseph Bearden, Luke Beckerdite, Laszlo Bodo, Philip Bradley, Skip Chalfant, Edward Coudon, Sarah Coulson, Heather Coyle, Ellen Endslow, Richard Englander, Thére Fiechter, Jim Gergat, Lee Ellen Griffith, Jim Guthrie, Lowell Haines, Erin Harrington, Ed Hinton, Leigh Keno, Jennifer Kindig, Mary Kirk, Sasha Lourie, John and Marjorie McGraw, Leigh Mackow, Lisa Minardi, Richard Mones, Scott Moran, Susan Newton, Patricia O’Donnell, Edward Plumstead, Barry Rauhauser, Margaret Schiffer, Katharine Schutt, Roy Smith, John J. Snyder Jr., Peggy Sprout, Susan Stautberg, Jeffrey Tillou, Floyd Warrington, Fran Wilkins, Wendell Zercher.

“Octoraro,” occasionally spelled “Otteraroe” on early maps, is derived from the Native American word Ottohohaho. According to nineteenth-century Lancaster County historian Jacob Mombert, it translates: “Where money and presents are distributed” (Jacob Isidor Mombert, An Authentic History of Lancaster County in the State of Pennsylvania [Lancaster, Pa.: J. E. Bakk & Co., 1869], p. 386). For further discussion of the Nottingham school, see Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725–1850 (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 2011), pp. 108–13. For an extensive survey of tall chests with feet attached with wooden screws, see Laura Keim Stutman, “‘Screwy Feet’: Removable Feet Chests of Drawers from Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Frederick County, Maryland” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1999). The furniture discussed in this article will more correctly be referred to as from the Nottingham area, not “Octoraro” furniture.

George Johnson, History of Cecil County, Maryland (Elkton, Md., 1881; reprint, Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1989), p. 147. For more on the settlement of the Nottingham Lots and East and West Nottingham Townships, see J. Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope, History of Chester County (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881), pp. 195–98. Also Pamela James Blumgart, ed., At the Head of the Bay: A Cultural and Architectural History of Cecil County, Maryland (Crownsville, Md.: Maryland Historical Trust Press, 1996), pp. 31–35; and East Nottingham Trustees, The Nottingham Lots: A Tercentenary Celebration, 2001 (Xlibris Corporation, 2006).

A. Hughlett Mason, The Journal of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1969), pp. 4–8. See also Edward E. Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1943), pp. 21–30. Today the geographic area under discussion extends south from the borough of Oxford, Chester County, Pennsylvania, through East and West Nottingham Townships (Pa.) and into northern Cecil County, including the areas in and around Calvert and Rising Sun, Maryland. The Brick Meeting is in Calvert, and a number of the earliest surviving dwellings are near Calvert and Rising Sun. Early maps of southeastern Pennsylvania often denote the post road southward as the Nottingham Road, further supporting the strong relation between Philadelphia and the Nottingham Lots.

For more on the Chandlee family and their work, see Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers; and Frank Hohmann, Timeless: Masterpiece American Brass Dial Clocks (New York: Hohmann Holding, 2009), pp. 198–99, 325–26. It is important to note that throughout his entire career, Benjamin Chandlee Jr. (as well as his sons Ellis and Isaac) inscribed “Nottingham” on both their brass dials and white-painted dials. This suggests that even after the Mason-Dixon Line was drawn, by 1768 Chandlee still considered his home to be Nottingham.

For more on Nottingham-area line-and-berry furniture, see Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, pp. 70–78. For the 1763 will and inventory of Thomas Coulson, see Chester County Archives, West Chester, Pa., no. 2087. Also see Lee Ellen Griffith, “Line-and-Berry Inlaid Furniture: A Regional Craft Tradition in Pennsylvania, 1682–1790” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1988); and Lee Ellen Griffith, “The Line-and-Berry Inlaid Furniture of Eighteenth-Century Chester County, Pennsylvania,” Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1202–11. The distinctive light and dark herringbone inlay appears to be a hallmark of Nottingham work and sometimes is seen on drawer fronts without any line-and-berry inlay; for an example, see Margaret Berwind Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), figs. 136, 137. Recently Dr. Harry Alden identified by microanalysis the light yellowish wood in this banding as sumac.

The attribution of the two desks to Hugh Alexander is based on the fact that one of them is said to have been made by him for his brother James and is still in the possession of descendants of James Alexander. The straight bracket feet on the Winterthur desk (fig. 4) are replacements copied directly from the original ones on the James Alexander desk. A related desk with herringbone inlay surrounding the drawers is illustrated in an ad for the House with the Brick Wall, Antiques 15, no. 1 (January 1929): 11. The interior is almost identical to that of the Alexander desk. For more on the Alexander family, see Rev. E. John Alexander, A Record of the Descendants of John Alexander, of Lanarkshire, Scotland, and His Wife, Margaret Glasson, Who Emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland, to Chester County, Pennsylvania, A.D. 1736 (Philadelphia: Alfred Martien, 1878), pp. 16–26. The light yellow wood on five interior drawer fronts and framing the prospect door of the attributed Alexander desk are sumac.

The Churchman House was built on lot 16 of the Nottingham tract by the son of John Churchman, one of the original settlers and first owner of that lot. John Churchman (1705–1775) was a prominent Quaker minister who traveled widely in the colonies and abroad. A built-in corner cupboard in the 1745 part of the Churchman House exhibits the same characteristic as later cupboards, with the upper section being extremely large in comparison to the lower portion. For more on John and his son George, see Futhey and Cope, History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, pp. 497–88; and The Nottingham Lots, pp. 28–33. For more on the Churchman, Knight, and Brown Houses, see Blumgart, At the Head of the Bay, pp. 187, 214–15, 464–67. In most instances the craftsmen who built these houses are not known, but in the case of the Mercer Brown House a number of initials are incised in the bricks identifying local artisans like William White, who sold Brown five hundred bricks, and Samuel England, who also supplied bricks. The initials of Hezekiah Rowls (1729–1802), a local joiner, are incised into bricks in both the Mercer Brown House and the Churchman House. When Rowls died in 1802, his inventory listed “To all the carpenter tools of all kinds . . . $53.33” and “To sundries of Boards in shop and out of Doors . . . $10.” See Cecil County Register of Wills (Inventories), Annapolis, Md., vol. 13, pp. 398–402, MSA C 620-17. In his will, which was finally probated in 1807, all of his carpenter’s tools were given to his son Elihu; see Cecil County Register of Wills (Wills), vol. 6, pp. 252–55, MAS 646-5. We thank Sasha Lourie for providing this information on Rowls. For more on the Knight House, see Elizabeth B. Reynolds, “‘The Planters Wisdom’: Four Eighteenth-Century Houses in Maryland’s Nottingham Lots Region” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2002), pp. 20–22. Additional information and images of these houses can be accessed through the Maryland Historical Trust’s Inventory of Historic Properties in Cecil County: www.mdihp.net/dsp_county.cfm?criteria2=CE.

For a detailed examination of the Haines House, see Reynolds, “‘The Planters Wisdom,’” pp. 22–27, 39–41, 144–47. Isaac Haines’s affluence is demonstrated in his 1805 inventory, in which the most costly item was his eight-day clock valued at $32.00.

The corner cupboard in figure 11 was given to the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1970 by J. Gilman D’Arcy Paul, who had a house in Harford County and a great interest in northern Maryland architecture and furniture. Where he acquired the cupboard is unknown, but it is reasonable to question the originality of the inlaid initials, since a female first name beginning with “W” is almost unheard of in eighteenth-century Nottingham. Perhaps it was inlaid later and meant to be “WMI,” in which case there would be a wide possibility of original owners. The cornice molding over a corner fireplace on the second floor of the Haines House is deeply molded with a drilled dentil lower portion; see www.mdihp.net/dsp_county.cfm?search=county&criteria1=W&criteria2=CE&criteria3=&id=6557&viewer=true. The Cross Keys Tavern in Chrome, Pennsylvania, has keystone motifs over the doorway of the central room similar to the molding in the Haines House. For images, see http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer/. Another Nottingham-area freestanding painted cupboard in a private collection has an upper paneled door of a related but simpler design, lacking the keystone shaping beneath the circular top portion.

In John G. Freeze, History of Columbia County, Pennsylvania, from the Earliest Times (Bloomsburg, Pa.: Elwell & Bittenbender, Publishers, 1883), p. 104, Mears is described as “born in Georgia about 1737 and came to Philadelphia with his mother, then the wife of John Lyndall, about 1754. He followed the business of ship-joining and cabinet-making. . . . He was the virtual founder and patriarch of the town of Catawissa. . . . Through the difficult country . . . he laid out and built the first carriage road, connecting the valleys of the Susquehannah and the Schuylkill, a great and laudable achievement in those times . . . . he was a Quaker preacher and physician, and though his methods were vigorous and rude, his manly presence, his patriotic services and sufferings, his integrity and enterprise won him universal respect, and embalmed his memory in the community. He died in the year 1819. . . .” There are no probate records for Mears in the Columbia County Court House, Bloomsburg, Pa., simply a record of his death. Marriage certificate (recorder’s copy), John Mears and Susannah Townsend, “5 mo 8 1760,” in Philadelphia Monthly Meeting Marriages, 1759–1814, MR-Ph359, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore, Pa. For Mears’s and Townsend’s transfer to the Nottingham Meeting, see William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Edwards Brothers, 1938), 2:595, 669. For additional references to Mears, see John J. Snyder Jr., “Carved Chippendale Case Furniture from Lancaster, Pennsylvania,” Antiques 107, no. 5 (May 1975): 964, 973; also Richard S. Machmer et al., Berks County Tall-Case Clocks, 1750 to 1850 (Reading, Pa.: Historical Society Press of Berks County, 1995), pp. 16, 29. See Jasper Yeates’s Account Book, p. 34, Lancaster Historical Society, Lancaster, Pa., and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Yeates Papers, Business Papers, Bills, Receipts, 1740–1768, Box 1, Collection #740. We thank Jim Gergat for calling the latter reference to our attention.

In 1793 Elisha Rogers sold John Price “that part or parcel of land and premises bequeathed by Rowland Rogers to the said Elisha Rogers.” Presumably that tract included his father’s house and contents, including the clock illustrated in figure 16. When Price died in 1815, he left to his grandsons Hiland and Jacob “all the personal property . . . except the Clock which I desire to Stand in the Rum She is now in” (Will of John Price, May 8, 1816, Cecil County Register of Wills, vol. 7, p. 160). The clock then descended from Hiland to Millicent (Melicent) R. Price, who married Judge James McCauley in 1849. It remained in the McCauley family until acquired by Winterthur Museum in 2003. Moses’s parents were Joseph Brinton (1692–1751) and Mary Peirce (b. 1690). In 1748 Moses moved to Lancaster County after his father gave him two hundred acres in Leacock Township. Brinton was an educated, wealthy, well-respected Quaker. From 1773 to 1777 he served as one of five trustees of the General Loan Office of Pennsylvania, frequently going to the printing office to have paper currency printed for loans. See Moses Brinton Account Book, 1774–1798, no. 250, Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, Pa.

For references to the Brinton and Elgar marriages and who witnessed them, see Alice L. Beard, Births, Deaths and Marriages of the Nottingham Quakers, 1680–1889 (Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books, 2006), p. 147.

To ascertain that the feet on the Brinton clock were original, they were carefully removed and extensively examined. For an illustration of the Brinton tall clock before 1924 (retaining its feet but having lost the sarcophagus top) pictured in the home of Susanna Brinton (1833–1927), see Gilbert Cope, comp., and Janetta Wright Schoonover, ed., The Brinton Genealogy (Trenton, N.J.: Press of MacCrellish & Quigley Company, 1924), opp. p. 161. The presence of the ball-and-claw feet on the clock in this photo gives further credibility to their originality. A typed note inside the door of the case states that Susanna “willed it to her nephew Moses Robert Brinton, of Drexel Hill, Pa., who after having the clock completely overhauled set it up in his home. . . .” For an illustration of the Rogers clock when it had been dropped through the floor of the Macauley homestead, see Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, p. 78.

Another Nottingham-area sarcophagus tall-case clock in a private collection with an early Benjamin Chandlee Jr. movement also has chalk drawings on the inner topmost surface of the backboard that echo rococo design motifs.

We thank Philip Bradley Jr. for calling our attention to the dressing table, which appears to have brasses identical to those on the Draper high chest and may have been made as a companion piece. Joana S. Donovan, Alexander Draper (1630–1691) Early Settler of Delmarva & His Descendants (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 2002), p. 82. When Margaret Churchman Painter Pyle died in 1885, it was reported in Every Evening the following day that Dr. James Avery Draper said the cause of death was “cancer of the stomach”; http://howardpyle.blogspot.com/2010/11/howard-pyles-mother-died-125-years-ago.html. Possibly artist Howard Pyle (1853–1911) inherited family furniture, as well as collecting some, for when his estate was sold at auction, it contained numerous pieces of antique furniture. See Philadelphia Art Galleries, Estate Sale of Howard Pyle, 1912. For the “Inventory and Appraisement of Cornelia Draper late of 1303 Rodney Street, Wilmington, Delaware . . . ,” see Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Probate 22523. We thank Jennifer Kindig for supplying the history of this high chest.

Chalk drawings and indecipherable script appear several places on the interior surfaces of the Draper high chest. The most fascinating yet puzzling inscriptions are on the inner surface of the backboard of the removable pediment; it appears to have the word/name “gatchel” (a Nottingham surname) but, in addition, a large cojoined script that appears to be the initials “B C.” Other script on the top of the upper case appears to be the name “Lydia.”

The Coudon desk-and-bookcase sold at Sotheby’s, Important American Folk Art, Furniture and Silver, May 19, 2005, lot 256. According to family history, Coudon was born in southern Chester County or northern Cecil County, and by 1765 he was a schoolmaster in the Cecil County Free School. We thank Edward Coudon for sharing information on his ancestor with us. For more on Coudon and his desk-and-bookcase, see Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, p. 112.

Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 180–83.

The desk illustrated in figure 37 sold at William H. Bunch Auctions, Chadds Ford, Pa., February 26, 2008. Inscribed on one of the document drawers are the names Barclay Reynolds, Amanda Reynolds, Eugene Reynolds, and Sophie C. Reynolds, with Rising Sun written below each name. Cite Keno desk sold to Nusrala – coming.

For the Lancaster desk-and-bookcase, see Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Silver, Prints, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, New York, January 18–19, 2001, lot 75.

For a complete discussion of this chest-on-chest, see Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), pp. 189–91. For a Lancaster example of carved shells with stippled grounds, see Winterthur’s desk-and-bookcase originally purchased by wealthy iron-forge owner Michael Withers; see Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, pp. 103–5. Like the shells on the Withers desk-and-bookcase valance drawers, the shells on the prospect doors of figures 36 and 37, as well as several tall chests with “bonnet” drawers with carved shell fronts, have stippling between the lobes. For a tall chest with this feature, see Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania, nos. 149, 150.

For another tall chest of drawers with a Greek key motif and signed by Hiett Hutton (1756–1833), see Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, pp. 13–14, 232. Hutton was born in Nottingham and married Sara Pugh in East Nottingham Meeting in 1792. He died in New Garden Township (see Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania, p. 124); to date it is not known where or with whom he apprenticed, but there is no question that his work exhibits characteristics of Nottingham-area furniture. For another tall chest with a Greek key design likely from the Nottingham area, see Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers, figs. 149, 150. The surviving upper portion of a chest-on-chest (now on a separate frame) has a Greek key beneath the cornice molding and a narrow drawer with molded face at the top identical to the one on the tall chest illustrated in figure 48. Another group of tall chests with characteristics related to the Nottingham furniture, though with a different ogee foot profile but having drilled cusps, can be attributed to Adam Glendenning on the basis of a high chest signed by Glendenning (private collection) of West Fallowfield Township north of Oxford and bordering Lancaster County. For the signed Glendenning example, see Philip H. Bradley Co. ad, Maine Antiques Digest (June 1993): 50. This tall chest has drilled dentils in the cornice, and, though the feet are replacements, they were based on a related example in the Chester County Historical Society (1997.42). For another tall chest from the same group, see Pook & Pook Auction, Downington, Pa., April 25, 2009, lot 464.

The clock with Duncan Beard movement is privately owned but presently on loan to the Biggs Museum, Dover, Delaware.

Quoted in Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, p. 109.

For the first reference to Brown, see Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania, p. 40. For the inventory and vendue of Jacob Brown, see Cecil County Register of Wills (Inventories), vol. 12, pp. 481–86, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis. Jacob Brown had a wife named Elizabeth, four daughters (two married), and seven sons (at least two under twenty-one). His inventory lists a “Mullato Girl now in our Possession . . . [to] be . . . manumitted . . . and set free at the age of twenty-one Years.” While Brown may have been born in what was then Chester County, Pa., when he died he was living in Cecil County, Md. The failure over time of scholars to look in Maryland probate records for Brown is responsible for perpetuating the belief that he had to be the Jacob Brown born in 1724. For a clock and case closely related to the Jacob Brown example illustrated in figure 55 but having a Greek key at the top of the waist instead of a fret and an applied central ornament on the plinth panel, see Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, p. 90.

Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, p. 90. Some of the boards listed among Jacob’s “goods and chattels” were one-inch thick, a dimension often encountered in furniture from the Nottingham region. No workbenches were listed among the effects sold. If Jacob intended for his family to continue his business, the benches may have passed directly to William or one of his other sons.

The timber used in this clock is very heavy, often measuring 1 1/8" thick. For whatever reason, Brown used 1/8"-thick plating on the tympanum, a feature that has been observed on another tall-case clock with movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. that is probably from Brown’s shop. A clock case closely related to the one in figures 58 and 59 was shown by Philip Bradley Antiques at the 2011 Philadelphia Antiques Show, though the plinth panel was of the simpler variety seen on the clock case illustrated in figure 60, and the movement was by Ellis and Isaac Chandlee with a white dial as shown in Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, pp. 198–99.

For additional cases with movements by Benjamin Chandlee Jr., Ellis Chandlee, Ellis and Isaac Chandlee, and Isaac Chandlee related to the one in figures 60 and 61, see Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, pp. 84–88, 92, 100, 102, 154–58, 160, 164, 172, 174, 214–19. The Chester County Historical Society has an Ellis Chandlee clock and an Isaac Chandlee clock with Brown-type cases; the Isaac Chandlee is illustrated in Chandlee, Six Quaker Clockmakers, pp. 218–19. While many of these later clocks do not have histories of ownership, a white-dial Isaac Chandlee example recently given to the Lancaster Historical Society does have a history of descent through a branch of the Brown family.