Advertisement of Samuel M. Dockum and Edmund M. Brown. (New-Hampshire Gazette [Portsmouth], December 11, 1827.)

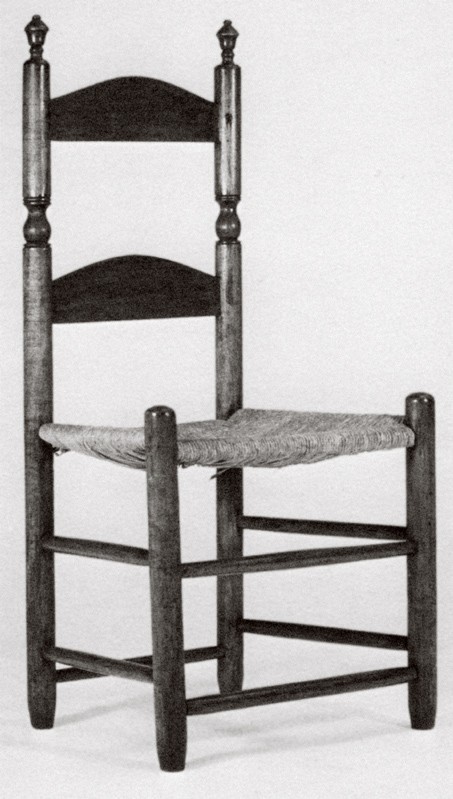

Slat-back side chair attributed to John Durand (1735–1780) or Samuel Durand I (1738–1829), Milford, Connecticut, 1760–1770. Maple, ash, and poplar; rush. H. 37 5/8", W. 18 7/8", D. 13 1/2. (Courtesy, Stratford Historical Society, Stratford, Connecticut, gift of Miss Martha Miles.) Surface finish not original.

Banister-back side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, area 1760–1800. Maple and ash; rush. H. 40 3/4", W. 19", D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, Boston, Massachusetts, gift of Joseph W. Hobbs; photo, David Bohl.) Surface paint not original.

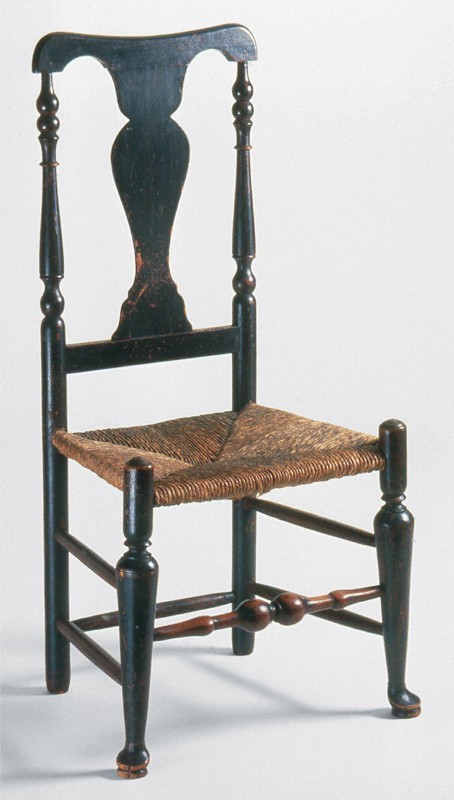

Fiddle-back side chair possibly made by John Durand or Samuel Durand I, probably Milford, Connecticut, 1760–1800. Maple; rush. H. 40 3/16", W. 18 1/8", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.) Black surface paint over a red primer; possibly original.

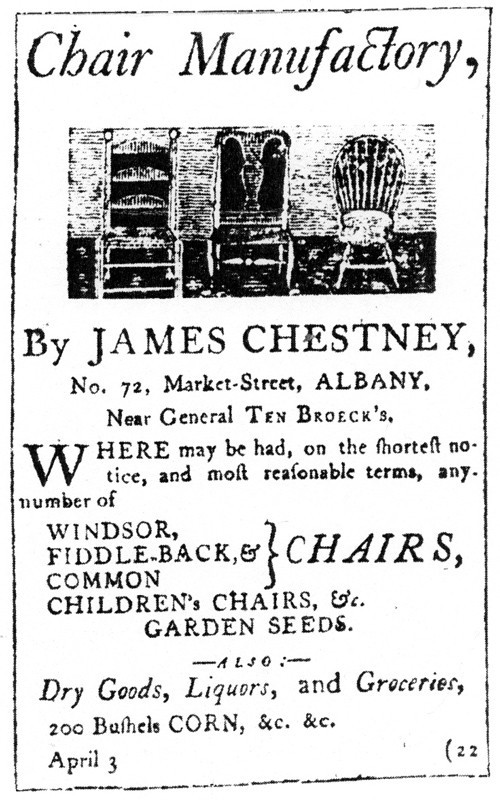

Advertisement of James Chestney. (Albany Chronicle [New York], April 10, 1797.)

Slat-back armchair, Delaware Valley, 1750–1775. Maple and hickory; rush. H. 43", W. 24 7/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Surface paint not original.

Detail, left arm post of sack-back Windsor armchair, Rhode Island, 1780–1800. White pine (seat) with maple, oak, hickory, and ash. H. 39 9/16", W. 23", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) An alligatored surface comprising multiple chipped layers of paint and resin. The “Windsor” green visible in chipped areas is the second coat of paint and probably predates 1815. This is the ubiquitous green made from the pigment verdigris, the color dulled owing to deterioration and yellowing of the protective resin coat.

Tall, braced fan-back Windsor armchair branded by Charles Chase (1731–1815), Nantucket, Massachusetts, 1790–1805. White pine (seat) with ash, birch, and oak. H. 42 3/4", W. 27 3/8", D. 20". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Present surface black; original surface verdigris green.

Shaped-tablet-top Windsor side chair with splat, branded by John Swint (act. ca. 1847 and later; chair one of four), Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1847–1855. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 33", W. 18 3/8", D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, Lancaster.History .org, Lancaster, Pennsylvania; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint approximating the olive green current by the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

Detail, slat-back Windsor side chair, southeastern central Pennsylvania, 1820–1830. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 35", W. 17 1/2", D. 15 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in bright yellow, the formula either the patent yellow or chrome yellow current in the early nineteenth century.

Slat-back (or triple-back) Windsor side chair branded by Silas Buss (chair one of four), Sterling, Massachusetts, 1820–1830. White pine (seat). H. 34 7/8", W. 16 1/2", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Marblehead Museum and Historical Society, Marblehead, Massachusetts; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in pale yellow termed either “straw” or “cane” color in the early nineteenth century.

Tablet-top Windsor side chair with stenciled identification of Cornelius E. R. Davis (one of six with a settee), Carlisle, Pennsylvania, ca. 1831–1835. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 32 7/8", W. 19 1/4", D. 15 1/8". (Courtesy, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in cream yellow.

Slat-back (or fret-back) fancy side chair, New York City or possibly central Connecticut, 1810–1820. Woods unknown; rush. Dimensions unknown. (Present location unknown; formerly in an institutional collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in white yellowed by a resin finish. A side chair of identical structure but different decoration has a nineteenth-century history in the Day family of Hartford, Connecticut.

Detail, slat-back (or ball-back) Windsor side chair, Hudson River valley, ca. 1820–1828. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 33 9/16", W. 16 1/4", D. 15". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York; photo, Winterthur Museum N0025.1954.) Original decoration and surface paint in medium gray.

Slat-back fancy side chair with “Cumberland spindles,” New York City or environs, 1810–1820. Maple, birch, and yellow poplar; rush. H. 35", W. 19", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in black.

Detail, Philadelphia fan-back Windsor side chair painted mahogany color, from John Lewis Krimmel, Quilting Frolic, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1813. Oil on canvas. 16 7/8" x 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top (or fret-back) fancy side chair, southeastern Pennsylvania or Maryland, 1825–1835. Woods unknown; rush. Dimensions unknown. (Present location unknown; formerly in an institutional collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in light stone color (drab).

Detail, slat-back Windsor rocking armchair with “flat sticks” (spindles), southern New Hampshire, 1820–1830. Maple and unidentified woods. H. 31", W. 19 3/8", D. 16 5/8" (seat). (Present location unknown; formerly in a private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in coquelicot red.

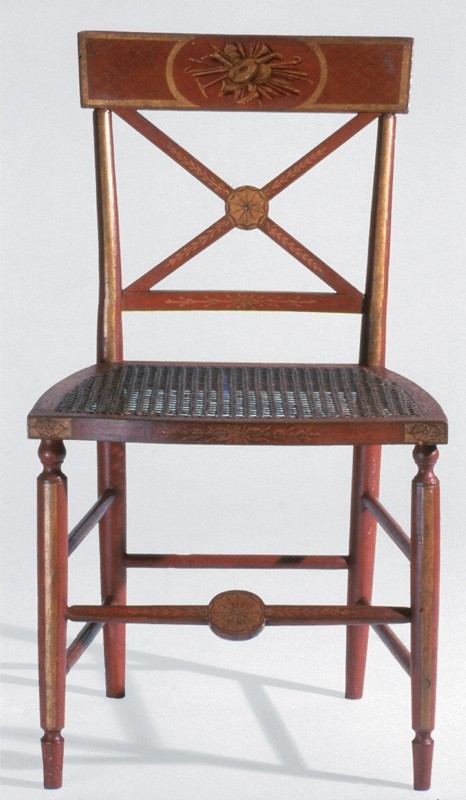

Tablet-top single-cross-back fancy side chair (one of five), Baltimore, Maryland, 1805–1815. Maple, butternut, and black walnut; cane. H. 32 1/2", W. 19", D. 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in coquelicot red.

Detail, bow-back Windsor side chair (one of six), Connecticut–Rhode Island border region, ca. 1797–1805. White pine (seat) with birch and ash. H. 38", W. 16 3/4", D. 16 3/16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original surface paint in Prussian blue on turned work, spindles, bow, and spindle platform; original “grained” paint on seat top in Venetian red and medium-light umber, with glazes of red and brown forming a looping pattern.

Shaped-slat-back Windsor side chair with flat sticks, northern Worcester County, Massachusetts, 1820–1830. White pine (seat). H. 34 1/8", W. 17 3/8", D. 15 1/4". (Present location unknown; formerly in an institutional collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in grained maple exhibiting a bird’s-eye figure on the crest and a striped figure on the turnings and spindles.

Detail, shaped-tablet-top Windsor side chair with stenciled identification of George Washington Bentley (b. ca. 1814; chair one of four), West Edmeston, New York, 1850–1860. Basswood (seat). H. 34 5/8", W. 15", D. 15". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York; photo, Winterthur Museum N0256.1959.) Original pinstriping and surface paint in grained rosewood exhibiting a “streaked” figure on the seat, crest, and mid-back slat and a daubed figure on the turnings.

Shaped-tablet-top Windsor side chair with splat and scroll seat, Baltimore, Maryland, or adjacent southern Pennsylvania, 1840–1850. Woods unknown. H. 33 1/4". (Courtesy, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.) Original decoration and surface paint in mahogany graining.

Detail, shaped-tablet-top Windsor side chair with splat (one of six), Pennsylvania, 1850–1870. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 32 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 1/2". (Present location unknown; formerly in a private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint, probably in satinwood graining.

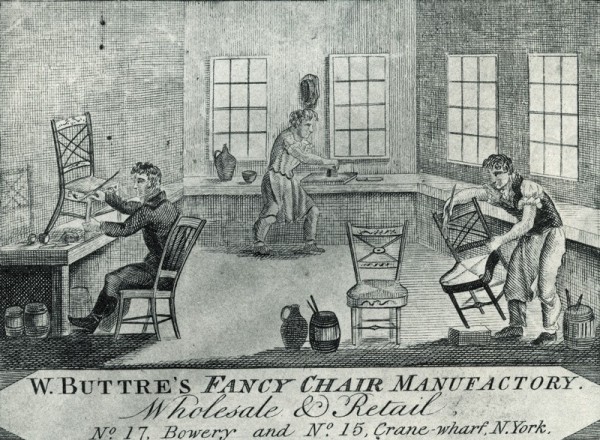

Detail, trade card of William Buttre (1782–1864), New York City, ca. 1813. Engraving. 5 7/8" x 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) The scene is a painting room such as that found in a large manufactory producing painted vernacular seating furniture. Note the abundance of windows to admit natural light to the workplace.

Slat-back (or ball-back) Windsor side chair with “organ spindles,” New York City, 1810–1815. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 32 5/8", W. 17 7/8", D. 15". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in pale blue.

Detail, roll-top Windsor side chair, Philadelphia or eastern Pennsylvania, 1830–1840. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 34 7/8", W. 17 3/8", D. 15 5/16". (Present location unknown; formerly in a private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in creamy white.

Shaped-tablet-top Windsor side chair with pierced splat and stenciled identification of George Nees (act. 1850 and later), Manheim, Pennsylvania, 1850–1860. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 32 1/4", W. 19 1/2", D. 14 1/4". (Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Donald M. Herr; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in bright green.

Tablet-top fancy side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 1820–1830. Woods unknown; rush. H. 33 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 15 7/8". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, gift of Stephen C. Clark, Sr.; photo, Winterthur Museum N0372.1955.) Original decoration and surface paint in dark rosewood graining. The paired-swan motif of the chair back was copied from an ornament in plate 21 of Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807).

Ornamental design with squirrels from page 12 of a drawing or copy book kept by Christian M. Nestell (1793–1880), when a student at an unknown school in New York City, 1811–1812. Pencil and watercolor on laid paper. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Detail, slat-back (or ball-back) Windsor armchair (one of two), New York City, 1814–1820. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple. H. 34 1/2", W. 19 1/4", D. 16 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in yellow.

Ornamental design with feathers from page 79 of the Nestell drawing or copy book. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Detail, slat-back (or fret-back) fancy side chair, New York City, 1815–1825. Woods unknown; cane. Dimensions unknown. (Present location unknown; formerly in an institutional collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in light stone color (drab). The transfer-printed profile of Benjamin Franklin is based on a terracotta medallion cast in France in 1777 by Giovanni Battista Nini.

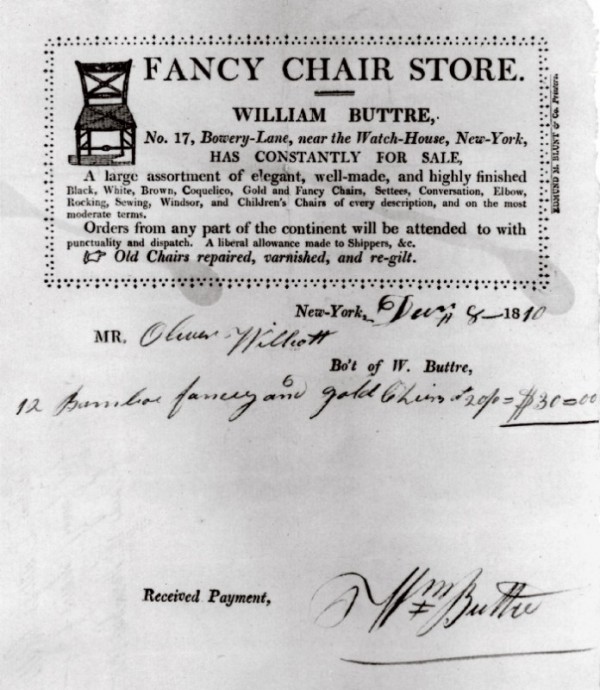

Printed and inscribed bill from William Buttre of New York City to Oliver Wolcott of Connecticut, December 8, 1810, for a large set of fancy chairs ornamented in gold. (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.) The text of the billhead enumerates a selection of chair colors and seating forms.

Shaped-slat-back Windsor rocking armchair, southern New Hampshire, 1820–1830. White pine (seat). H. 35", W. 20 1/4", D. 17 7/8" (seat). (Present location unknown; formerly in a private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in light stone color (drab).

Detail, roll-top Windsor settee with scroll arms, south-central Pennsylvania, 1835–1845. Woods unknown. H. 33 1/8", W. 76 1/2", D. 21". (Present location unknown; formerly in a private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in light stone color (drab).

Windsor cricket, or low stool, northern New England, 1825–1840. Basswood (top) with birch. H. 7 1/8", W. 13", D. 8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Original decoration and surface paint in yellow.

Child’s sack-back Windsor armchair, New York City, 1785–1795. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and oak. H. 25", W. 18", D. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) A multilayered surface with coral red on the outside over white over a deteriorated dark color. Given the date and origin of this chair, the original surface paint probably was verdigris green. As demonstrated here, in the absence of an exposed original surface or the presence of a surface cleaned to the bare wood, a surface that retains many layers of paint (and resin) reflecting various surface renewals over time is typical.

Almost every shop that produced furniture in the late colonial and federal periods finished the surfaces of its products with some type of protective coating—wax, oil, varnish, color in varnish or size, stain, or paint. Color, stain, and paint also masked the natural color of the wood. The application of ornament further enhanced the aesthetic experience.

The material presented in this study is drawn from a large body of documents, consisting of craftsmen’s account books and sheets, clients’ business records, court and shipping records, probate records for general households and those of craftsmen, a manuscript price book, newspapers, technical books and articles published in the period under study, and selected primary references from recent publications. The geographic coverage is broad: New England, the Middle Atlantic region, the South from Maryland to Georgia, and Kentucky and Ohio in the “West.” Within these political boundaries, the culture varied from rural to urban economies. Material originating in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania is the most plentiful.

The most popular furniture form in the late colonial and federal periods was the chair, beginning with common woven-bottom utilitarian styles constructed with slats, splats, or banisters, followed by the Windsor chair, and culminating in the fancy chair. Some material used for this study contains information pertaining to the purchase and cost of raw materials, tools, and accessories used in painting and other surface coatings. Recipes for paint colors provide further insight on period practice.

References in late colonial and federal period records to surface coatings on furniture, especially paint, are relatively frequent; actual color identification is unusual. Jacob Bigelow in his two-volume The Useful Arts noted that the object of “common painting” is “to produce a uniform and permanent coating upon surfaces, by applying to them a compound, which is more or less opaque.” He further noted that “in many cases painting is applied only for ornament, but it is more frequently employed to protect perishable substances from the changes to which they are liable when exposed to the atmosphere, and other decomposing agents.” Bigelow concluded by stating, “The effect and durability of different coverings employed in this way, depends upon the kind of pigment used, and still more upon the vehicle, or uniting medium, by . . . which it is applied.”[1]

SIDE CHAIRS AND ARMCHAIRS

GENERAL COMMENTS ON SURFACE EMBELLISHMENT

General references to paint and other surface coatings on chairs describe a substantial body of data that includes all constructions and styles. A few references note the number of finish coats applied to surfaces, new or refurbished. That number varies from one to four, one coat likely identifying the inexpensive utilitarian chair, higher numbers pointing to more sophisticated seating enhanced with ornament. For instance, work done by Silas E. Cheney at Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1821 for Orin Judd involved “Painting 9 Chairs 4 Coats.” The first coat was a primer. The three remaining coats may have included the pigment of choice, although since these chairs also were ornamented, the fourth coat likely was a varnish finish designed to protect the embellished surfaces.[2]

“Old Chairs” are among the large group of refurbished seating itemized in craftsmen’s accounts. Artisans in urban centers regularly solicited this type of work in local newspapers as a complement to new production and structural repairs. Early-nineteenth-century craftsmen who advertised this service include Joseph Very of Portland, Maine; George Dame of Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Reuben Sanborn of Boston. Another Boston craftsman described the expectations of consumers: “Chairs repaired and repainted to look as good as new.” James Always of New York perhaps offered the ultimate service: “He has good accommodations for drying old chairs when re-painted, and he will take them from any part of the town, and return them in good order.”[3]

The basic utilitarian chair ubiquitous to households had several names, one being “Common chair.” After leaving Massachusetts in 1809, Allen Holcomb worked as a journeyman in the shop of Simon Smith at Troy, New York, where he recorded “painting 6 Common chairs 2 C[oa]ts.” By 1813 Holcomb had resettled in Otsego County. Just as familiar to householders was the term “kitchen chair,” describing the chair’s principal place of use. True Currier of Deerfield, New Hampshire, recorded selling “seven kitchen chair frames painted” in 1828 at a charge of 50¢ apiece. Emphasis on the term “frame,” one with cross slats in the back, suggests that the seats were open, or without woven “straw” or “flag” (rush) to provide a solid bottom for sitting. An earlier account from the Amherst, Massachusetts, shop of Nathaniel Bangs addresses that feature in charging Captain Oliver Allen 60¢ apiece for “five Chair fraims and for painting and bottoming.”[4]

Two alternative surface coatings for the common slat-back, or kitchen, chair were color in size (a gluelike material) and stain, both priced about the same for similar construction. From the early eighteenth century these finishes were in use on chairs constructed with three to five slats, often identified as three-, four-, and five-back chairs. Two New England shop accounts highlight the variable terminology: Joseph Brown of Newbury, Massachusetts, sold “4 Culler’d Chairs 4 backt” in 1741, followed by Isaiah Tiffany’s sale of “6 Chairs 4 Slats Colour’d” in 1756 at Norwich, Connecticut. Solomon Fussell of Philadelphia sold both colored and stained (“dyed”) chairs during the late 1730s and 1740s, the slats numbering from three to five. Fussell’s basic price for his three-slat side chair was 4 shillings. Each additional slat added a price increment: four-slat chairs cost 4s. 6d. to 5s.; five-slat chairs fetched 5s. 6d.; and Fussell’s “best” five-slat chairs cost 6s. or 6s. 6d. In the prevailing barter economy, several individuals found Fussell’s products useful for settling debts. In 1741 Joseph Marshall ordered “1/2 Duz best 5 Slat Chairs Dyed dd [delivered to] walter Coal [Cole]” and “1/2 Duz: three Slat Coular’d Chairs dd to ye plasterer.” Whereas delivery of finished chairs to a customer or his creditor may have been routine for Fussell, the practice had changed by the end of the century, and it was the customer’s responsibility to fetch furniture from the woodworker’s shop. Unusual events elicited comment, as noted in 1797 by Jacob Merrill Jr. of Plymouth, New Hampshire, in a client account: “going to your house & Colouring Six frames.”[5]

The Windsor chair became an important market commodity in the post-Revolutionary period, catapulted to the forefront in the mid-1780s by the introduction of the bow-back side chair, also known as a “dining Windsor chair.” With its oval back, the bow-back Windsor required little space at the dining table, a boon in the large families typical of the period. Consumers had been aware of the basic benefits of Windsor seating since its introduction to American vernacular furniture in the mid-1740s: Windsor chairs were economical, the price somewhat more than slat-back seating but within range of middle-class pocketbooks; the construction was durable and practical; wooden seats were not subject to constant repair and replacement as were woven bottoms of straw, rush, or cane; and scuffed surfaces could be refreshed with a coat of paint. Bright-colored paint on furniture and walls had the power to bring life to dark and drab interiors. By 1800 Lawrence Allwine of Philadelphia offered “the best windsor chairs . . . painted with his own patent colours,” cited for their “brilliancy and durability.” A varnish finish protected painted surfaces, whether plain or ornamented. In April 1801 Oliver Goodwin, a Charleston, South Carolina, merchant, announced his receipt from New York of “300 Fancy Windsor Chairs . . . executed . . . with permanent and lasting varnishes to exceed anything . . . ever introduced in the southern States.”[6]

Windsor chairs sent to the local woodworker for a fresh coat of paint might also need repair. Silas E. Cheney recorded a job at Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1820 that required “giting out nails out of 8 . . . Chair Seat[s] & Smothing Out Seats” before he could paint. Many chairmakers did their own painting; others, particularly proprietors of large shops, employed painting specialists as needed. Edward Jenner Carpenter, apprentice to Miles and Lyons at Greenfield, Massachusetts, noted in his journal on May 16, 1844, the shop visit of Mr. Wilson “to paint chair[s].” Wilson departed eight days later for his home in Colrain, a rural village nine miles northwest of Greenfield. Nelson Talcott of Portage County, Ohio, recorded similar activity in that decade, although his interaction with journeymen painters often was formalized with a contract. Typical, perhaps, was Talcott’s arrangement with William B. Payne, who began working on contract in February 1841 “at painting chairs”: “He [Payne] is to paint the Grountt work . . . of comon [Windsor] Chairs at three cents pr chair and be Bourded, or at three and three fourths cents each and Bourd himself—if he Bourds himself and Bourds with the said Talcott he is to have his Bourd for one dollar thirty seven 1/2 cents per Week.” Whichever boarding plan Payne chose, his piecework arrangement required that he paint approximately 167 chairs during a six-day work week to earn an average journeyman wage of 83.3¢ per day (5s.), or 200 chairs during the same period to earn a high wage of $1.00 per day (6s.). His profit depended on his skill and proficiency at the job.[7]

Records indicate that journeymen led itinerant lives on occasion, picking up work where they could. Of relevance is an itinerancy recorded by Jacob S. Van Tyne, a sign and ornamental painter who left Cayuga County, New York, in January 1836 for a sojourn of more than three years, which took him as far afield as Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio. The itinerant life bred uncertainty and anxiety, as Van Tyne noted in his journal in May 1838: “Arrived at Union Town, Pa, With my spirits very much cast down being out of money and in a strange place among total strangers.” He related how, while walking in town, “I happened to cast my eye up and saw a sign of a House, sign, and Ornamental Painter by the name of W. Maquilken. I immediately went in and applied for work and was successful. O! How thankful aught I to be for this interposition of Gods providence in thus snatching me from the immediate jaws of want and poverty and placing me out of the reach of either.” Van Tyne’s work pleased his employer, who within eleven days raised the painter’s wages to $16 per month, which, as Van Tyne noted, “Encouraged me very much and put me more in mind of the goodness of God in thus turning the scale of fortune in my favour.”[8]

Fancy chairs represented a step up from Windsor seating in cost and sophistication, especially those with seats of woven cane rather than rush. Many shops that made Windsor chairs also framed fancy chairs, and the same specialists painted either type of seating. Among those painters were men who worked at times in Portage County, Ohio, for Nelson Talcott, who probably supplied the painting materials used by his workmen. A charge against Sylvester Tyler Jr. in 1840 for “Paint for 1 2/6 Set Fancy chairs,” or eight chairs, suggests that Taylor occasionally took on outside jobs on his own time while working in Talcott’s shop. A similar circumstance is suggested in the accounts of James Gere of Groton, Connecticut, who often employed area workmen to paint chairs. In 1824 John Ashley Willet, who resided independently at Norwich, was credited with painting and ornamenting fancy and Windsor chairs. On two occasions he was debited for “paint & Varnish &c. for Chairs,” the charges appearing to have occurred at a time when he was boarding with Gere.[9]

Unlike the surface coatings on Windsor chairs, those on fancy chairs also employed materials other than paint. An early record of “12 Chairs Making & Japanning” dates to 1794, when William Lycett of New York produced seating for Chancellor Robert R. Livingston. In japanning, paint pigment was mixed with varnish and applied in layers over a special ground coat. The object of the process, which was imported from Europe, was to imitate oriental lacquer. Somewhat cheaper was the practice of staining fancy chairs. In 1819 at the death of Benjamin Bass, a cabinetmaker and chairmaker of Boston, appraisers itemized three groups of stained fancy seating in the shop: thirty-six chairs were “partly stain’d,” twelve more frames were fully stained, and a third group consisted of “12 Stain’d Chairs Flagg’d,” that is, coated frames with rush seats in place.[10]

Fancy chairs and, in particular, Windsor chairs became important products of commerce in the post-Revolutionary period. Many chair shops, large and small, marketed seating furniture to customers beyond the local area in overland, coastal, and overseas locations. Because chairs were vulnerable to surface damage in transit, some craftsmen took steps to turn this situation to their advantage. The Wilmington, North Carolina, firm of Vosburgh and Childs whose business, like that of most Southern craftsmen, was compromised by Northern imports, advertised: “How far preferable chairs must be manufactured in the state, warranted to be both well made and painted with the best materials, to those that are imported, which are always unavoidably rubbed and bruised.” Thomas Henning Sr. of Lewisburg, West Virginia, addressed the hazard of overland transport, stating, “He would like to deliver chairs unpainted, and paint them where they are to be used, as hauling always injures the appearance of chairs that are painted.” Still other strategies were employed. Silas Cooper of Savannah, Georgia, traveled to “the north” to purchase “fashionable CHAIRS,” which on his return he “finished on the spot,” ensuring the paint was “not injured by transportation.” When Dockum and Brown, chair retailers at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, “received ONE THOUSAND CHAIRS, of various kinds and colors,” from Boston in 1827, they engaged “first rate workmen from Boston” to paint and gild the chairs at Portsmouth (fig. 1).[11]

COLOR REFERENCES TO PAINTED SURFACES:

COMMON-CHAIR PRODUCTION

References to surface color are relatively common for chairs, unlike other furniture forms, a situation that permits an investigation of some depth by actual color group. First to be considered are “common” chairs with woven bottoms. In the seating hierarchy, they were first in the market and lowest priced. Among consumers, the most popular color choice in woven-bottom common seating probably was black, with white chairs and red chairs coming in second and third. White chairs were the cheapest, however, and this is where the discussion begins. The term “white” in this instance did not identify a paint color but instead denoted the absence of color, or chairs left “in the wood” without a surface coating. Later in the century the term came to identify a surface actually painted white.

The accounts of two craftsmen, Solomon Fussell of Philadelphia and John Durand of Milford, Connecticut, best amplify this point. Fussell produced “white” chairs between 1738 and 1748. Durand’s construction of unpainted chairs, which he referred to as “plain” chairs rather than white chairs, extends from 1763 to 1776 in this study. Together the accounts exhibit price variations for this basic chair from 1s. 4d. to 3s. 8d., an indication that customer options existed. When supplied, woven rush was the common seating material of both craftsmen’s chairs.[12]

Durand’s product probably took the form of an open-frame chair with plain cylindrical front legs, back posts with minimal turned ornament, and two cross slats uniting the posts. Chairs of this type have family or other histories in Milford. Durand’s sale to Deacon Joseph Treat of “half a Dozen plain Chair[s]” in 1776 priced at 1s. 4d. each describes side chair frames without “bottoms,” or woven seats, and little turned work other than back-post finials (fig. 2). Plain chairs priced by Durand between 3s. and 3s. 8d. likely included one or more structural options beyond a basic frame: woven rush seats, turned work in the legs and posts, and possibly a third cross slat in the back.[13]

Fussell’s “white” chair production at Philadelphia may have paralleled Durand’s work. His cheapest “white” frame, as sold to Abraham Linkcorn in 1743 for 2s. 3d., is described as “one white Chair w[ith] out armes.” This chair and Fussell’s white chairs priced at 3s. possibly had only two back slats, and both probably lacked rush seats. The difference between the two likely was in turned work. Fussell’s accounts further suggest that by increasing the white-chair price by 3d., the customer could acquire chairs with woven bottoms, as recorded for Richard Tyson, who bought “6 white Chairs & Mating” for 3s. 3d. apiece. Again, these chairs may have had only two cross slats in the backs because three-slat chairs sold to William Moss cost 3s. 6d. the chair, an indication that a third slat raised the price by at least 3 pence. Moss’s further purchases of “4 Reed [red] 3 Slat Chairs” and “4 Black 3 Slat Chairs” priced individually at 4s. and 4s. 6d., respectively, reinforces this reasoning. The greater pricing of the three-slat red and black chairs reflects the addition of paint to the wooden surfaces and possibly the introduction of more turned ornament.[14]

Several decades later, in 1770, Fussell’s former apprentice William Savery sold “Eight white Rush bottom Chairs” priced individually at 4s. to the prominent Philadelphian General John Cadwalader, whose residence stood in Second Street between Spruce and Pine. The unit price of the chairs and their placement in a richly appointed town house, albeit in a service area, suggests the frames were painted white rather than left “in the wood.” Cadwalader’s purchase suggests that a new era sometimes requires a new interpretation of terminology.[15]

Entries in the accounts of other craftsmen confirm the information gleaned from the records examined above: white chairs priced under 3s. usually had two back slats, and those priced at about 3s. to less than 4s. probably had three back slats. Supporting this conclusion are the early-eighteenth-century records of Miles Ward of Salem, Massachusetts, and John II and Thomas Gaines of Ipswich. Isaiah Tiffany penned similar midcentury records in eastern Connecticut, followed by accounts kept by David Haven at Framingham, Massachusetts. Two items from a list of “goods and things” given by John Baker of Rehoboth, Massachusetts, to his daughters Rebecca and Bathsheba in the 1760s serve to sum up: each received “six three-backs Black chairs” valued at 3s. apiece and “2 two-backs white chairs,” probably unpainted, that cost 2s. apiece.[16]

Date and price are the criteria in interpreting common “black” chairs listed in craftsmen’s eighteenth-century accounts. If the date is early and the price low, slat-back chairs seem indicated. That style constituted Solomon Fussell’s entire black-chair production at Philadelphia during the late 1730s and 1740s. The chairmaker’s records describe his price structure for the slat-back models in black offered at his shop: a three-slat chair varied from 4s. to 4s. 6d.; the four-slat chair was 4s. 6d. or 5s.; and the five-slat model stood at 5s. to 5s. 6d. Thus, with the addition of each slat, the basic chair price increased by 6 pence. The cost of wood was negligible. The real expense of adding a slat was the labor: sawing the back piece to shape, shaving it to thickness and bending it to a lateral form, then cutting two mortise holes in the back posts, fitting the slat into the mortises, and pinning it in place. Special requests added an increment to chair cost. A customer who ordered a four-slat armchair paid about 6d. for the elbow pieces. Another customer who bought six new five-slat chairs substituted a “turn’d frunt” with thick double-vase turnings separated by a central disk (see fig. 6) for the basic cylindrical stretcher at an extra cost of 4d. or 5d.[17]

Several New England craftsmen recorded the production of black slat-back chairs. In the 1720s and 1730s Miles Ward of Salem, Massachusetts, charged 4s. 6d. to 5s. for black “4 back” (slat) chairs. Elisha Hawley still made black chairs late in the century at Ridgefield, Connecticut, the price ranging from 2s. 8d. to 4s., suggesting that he sold two-, three-, and possibly four-back common chairs in the local market. Ward also recorded a somewhat more expensive set of black chairs purchased in 1737 by John Low at 6s. apiece. These may have been banister-back chairs with relatively plain crests and somewhat more ornate turnings than those usual on the slat-back chair. A “Great black Chair” priced at 8s. by Jacob Hinsdale, a contemporary of Ward at Harwinton, Connecticut, likely describes a banister-back armchair (fig. 3). At Milford John Durand possibly identified banister-back seating in 1774 in the sale of “half a Dozen black Chairs” priced individually at 6s. The banister-back style was especially popular along the Connecticut coast.[18]

Some significance may be associated with the absence of a red chair from the production of three craftsmen who framed both black and white chairs before 1740. The records of Miles Ward and the Gaines family of Massachusetts and Jacob Hinsdale of Connecticut are silent on the subject. In contrast, the records of Solomon Fussell, who framed common chairs at Philadelphia from 1738 to 1748, indicate that he constructed “red” chairs with three to five back slats in addition to his white (“in the wood”) and black slat-back production. Fussell priced red and black chairs the same, although his red chairs appear to have been less in demand than his black or white chairs. As usual, payment was flexible; Isaac Knight Sr. paid for his “6 Reed 5 Slat Chairs” with “a Hog.”[19]

What was the red paint used on chairs made by Fussell and other craftsmen at various locations, including New Hampshire, upstate New York, Nantucket Island, and Connecticut? Two nineteenth-century authors, Hezekiah Reynolds in Directions for House and Ship Painting (1812) and Nathaniel Whittock in The Decorative Painters’ and Glaziers’ Guide (1827), identified the principal pigments available for making red paint: vermilion, red lead, Venetian red, Spanish brown, and red ochre. A review of several dozen records dating between the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries indicates that craftsmen, based on their possession of these pigments, overwhelmingly favored Spanish brown and red lead as ingredients for red paint. Taking the analysis a step further, Spanish brown likely was the popular choice for painting “red” chairs in the eighteenth century because it is mentioned more frequently in records and because some red lead in the possession of craftsmen was destined for use as a drier in the preparation of linseed oil and varnish rather than as a pigment for exterior, interior, or furniture paint. Spanish brown, as known in the eighteenth century, was a reddish brown earth containing iron oxides that was processed for use as a pigment. The color probably was akin to the barn red known today.[20]

As early as 1750 James Claypoole, a painter and glazier of Philadelphia, listed Spanish brown among a selection of imported pigments and related material offered for sale at his shop. The trade in this commodity expanded, and when Kenneth McKenzie, a fellow artisan in the craft at New York City, died in 1804, appraisers itemized among the painting materials on the premises forty “Kegs Spanish brown g[roun]d in oil 900 lb” valued at 4d. per pound. Already by 1800 it was not uncommon for purveyors of painting materials to stock products of demand, including Spanish brown, in quantities of one ton or more, as advertised by John McElwee at Philadelphia.[21]

Beyond the Philadelphia shop of Solomon Fussell, red chairs were made in more northerly locations. John Durand of Milford, Connecticut, who constructed white (“plain”) chairs and some black chairs, had a substantial production of red chairs in the 1760s and 1770s. Unit costs of 4s. 6d. to 8s. suggest that several styles were represented, a circumstance supported by known production in coastal Connecticut. Durand’s “red” chairs priced in the lower range probably included banister-back and splat-back (“york”) chairs of basic turned side-chair form. The price increased with the selection of special options: arms, an ornamental crest, or embellished turnings. A red chair produced by Durand in the mid-price range of 6s. or 7s. had a splat back and distinctive turned front supports with trumpet-shaped legs and pad feet, a seating type probably referred to locally as a “fiddle-back” chair (fig. 4). Supporting this reasoning are the accounts of Titus Preston of the inland town of Wallingford. For a customer whose daughter was setting up housekeeping in 1804, Preston supplied a quantity of furniture, including Windsor chairs for the dining parlor (7s. 8d. each) and “6 red fiddle back chairs” for other household use (6s. apiece).[22]

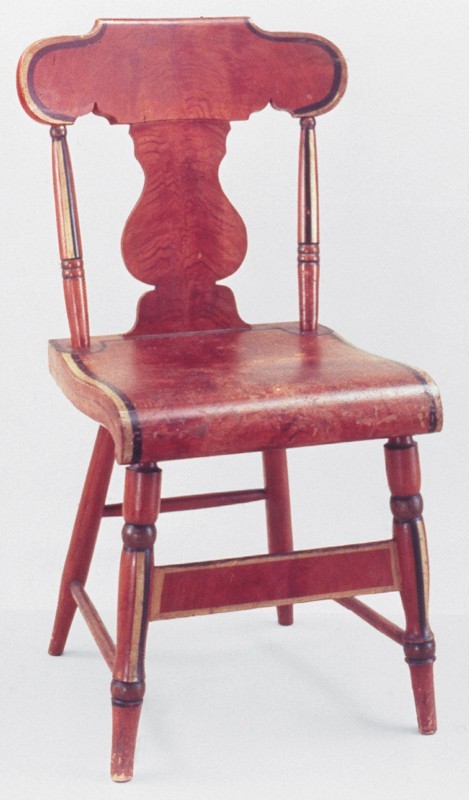

The slat-back style was part of red-chair production in other areas. For Ezekiel Robinson of Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Moody Carr made “a red Chaire for your Pew” in 1800, identified as a slat-back chair by its 3s. price. Three-back and four-back chairs painted red were popular on Nantucket Island in the late eighteenth century, judging by the numbers listed in inventories, which well exceed those painted black. Another back style may be represented by the “8 Red Common Chairs” purchased for 5s. each in 1793 from James Chestney of Albany, New York, by Madame Schuyler. Chestney’s advertisement for his “Chair Manufactory,” published in a local newspaper in 1797, illustrates the three chair styles he framed (fig. 5). The 5s. price best describes Chestney’s “fiddle-back” chair with a back splat and trumpet-style legs.[23]

Craftsmen’s accounts identify several other paint colors used for common-chair surfaces, although their occurrence is infrequent. Most references focus on the color brown. The Gaines family of Ipswich, Massachusetts, produced at least one set of brown four-slat chairs. Between 1738 and 1748 their contemporary at Philadelphia, Solomon Fussell, sold brown chairs with three, four, and five slats priced from 4s. to 5s. Fussell’s customers may have favored brown chairs over red seating, although the numbers do not equal those of the shop’s black or “white” slat-back production. Other evidence of slat-back seating occurs in a list of furniture in the home of merchant Benjamin H. Hathorne at Boston, where “3 Brown Kitchen [Chairs]” valued at 5s. 3d. apiece probably were new and likely had arms. “5 new Brown Chairs” each valued at 4s. in 1793 also stood in the Nantucket home of widow Mary Pease, a trader. It is not known whether the “6 Chocolate coloured rush bottom’d Chairs” in the Chester County, Pennsylvania, household of William Jones in 1789 duplicated the brown color of other rush-bottom chairs.[24]

The more expensive fiddle-back chair also figures in a discussion of brown seating. At his death in 1794, John Avery Sr., a Preston, Connecticut, silversmith and clockmaker, possessed “Six brown Fiddle back [Chairs]” still valued at 5s. each. These and the red fiddle-back chairs described above are complemented in records analyzed for this study by two additional color choices for similar seating. At least one set of green chairs, among several sets listed in the late-eighteenth-century accounts of Elisha Hawley of Ridgefield, Connecticut, was constructed in the fiddle-back style. The 7s. unit price is comparable to that of two unidentified sets of green chairs produced in the shop. “Seven blew fiddle back chairs,” possibly with arms, constructed in 1781 by James Wheeler Geer for a customer at Preston were more expensive at 8s. 8d. the chair.[25]

The remaining common-chair production identified by color in craftsmen’s accounts appears to describe chairs with slat backs. Oliver Moore, a craftsman of rural East Granby, Connecticut, constructed “six citching chairs painted green and varnished @ 6s.,” or $1.00 apiece, in 1820 for Erastus Holcomb. The unit price seems high until one takes into account the fact that the surfaces received paint and varnish, two separate tasks, and the chairs may have had arms. Several inventories describe “rush bottom chairs painted blue” with low evaluations, including two estates probated at Baltimore in the 1770s. Among several inventories from Chester County, Pennsylvania, that list blue rush-bottom chairs, two name locations. In the home of Thomas Pim, who died in 1786, the chairs stood in a back room over the parlor. In 1823 appraisers located blue chairs in the south room of the upper storey at the home of Elijah Funk. Other records describe yellow chairs. In 1824 Captain Nathaniel Kinsman bought “4 yallau Chairs” with rush seats from Samuel Beal of Boston for 4s. 6d. apiece. At the death of James Chapman of Ellington, Connecticut, appraisers identified an alternative seating material: “6 yellow split [splint] bottom chairs.” Splints for weaving chair seats (or baskets) were harvested from the inner bark of selected trees, frequently the hickory tree.[26]

An unusual color reference to common seating in early records is “orange,” a word that may identify paint, stain, or pigment in varnish or size. If the coating was paint, a recipe in the accounts of William Fifield of Lyme, New Hampshire, may apply. The basic pigment was stone yellow, a mixture of white lead and yellow ochre proportioned at fourteen parts to five, with a tiny amount of ivory black, followed by the addition of red lead to increase the mixture by half. In 1789 William Jones of Chester County, Pennsylvania, owned “3 Rush bottom Chairs Orange color” in a home filled with rush seating in black and chocolate color, probably all with slat backs. Another record describes “6 Orange Coular chairs” purchased at Philadelphia in 1747 from Solomon Fussell at 6s. 6d. apiece. The pricing was unusual for common chairs made by Fussell, although two other sets of similar price shed further light on the appearance of these orange chairs. One set is identified as “6 Best Dyd [stained] 5 Slat Chairs.” The description of the second set appears to define the word “best”: “6 turned frunts archback Dyd Chairs.” These are the iconic Delaware Valley chairs with bold double-baluster front stretchers and back slats arched along both edges, as further confirmed at the death in 1766 of Daniel Jones, another Philadelphia chairmaker (fig. 6). Whereas appraisers itemized a varied stock of slat-back seating, of relevance here are chairs described as “6 five Slats arch’d & turn’d fronts, Blue.” Other shop stock had “plain Backs & turn’d fronts.” Of further interest is the inventory item “About half a pound of Prusia Blew at 1/3 an Oance.”[27]

COLOR REFERENCES TO PAINTED SURFACES: WINDSOR-CHAIR AND FANCY-CHAIR PRODU TION

In terms of mainstream production and price structuring, Windsor seating and fancy-chair work followed common-chair production as the popular focus in household seating. Of the many Windsor and fancy chairs listed in documents of the late colonial and federal periods, only a fraction is identified by color and/or decoration. Nonetheless, this small body of material is sufficiently sizable to allow a discussion of the various color choices individually, although the line between the two construction forms often is blurred in records. The discussion proceeds from the most to least common consumer options in surface color, as indicated by the material gathered for this study. Green heads the list of solid color grounds; blue was the least favorite choice. An investigation of grained surfaces, principally those in imitation of wood, forms a separate topic at the end of this section, followed by a discussion of ornament, the focus principally on post-1800 production, when chair styles offered broad, flat surfaces for decoration.

Green Chairs

Green was a color choice for Windsor-chair surfaces from the time this construction form was introduced until well into the nineteenth century. In 1730, little more than a decade after Windsor seating was made in England, John Brown, a chairmaker of London, offered for sale “ALL SORTS OF WINDSOR GARDEN CHAIRS, of all Sizes, painted green or in the Wood.” As most early Windsor production was destined for garden use, green paint was an obvious choice. This was the color introduced to America through early imports of Windsor furniture, and it was the color adopted by American craftsmen when domestic production began in the 1740s at Philadelphia. John Fanning Watson, a chronicler of early life in that city, stated in the early nineteenth century, “When the first windsor chairs were introduced, they were universally green.”[28]

Because green was the single color choice for Windsor seating through the Revolution, most documents relative to early production are silent on the subject of color. Shipping records are the first sources to identify green surfaces. In 1775 James Bentham of Charleston, South Carolina, announced the arrival of a vessel carrying “Green Windsor chairs” from Philadelphia, the principal center of Windsor chairmaking in America. Several references originating at Newport, Rhode Island, a community whose initial Windsor production followed that of Philadelphia, date earlier. Aaron Lopez, a merchant with international shipping interests, ventured Newport-constructed “round back wooden bottom Green Chairs” (low-back Windsors) in 1767 and 1768 to several markets in his business sphere: Savannah, Georgia; coastal Maryland; the Bay of Honduras; and Surinam. The American ports also received green chairs “with high backs.” In the postwar years Stephen Girard, a rising Philadelphia merchant, launched his shipping enterprise. “Green windsor Chairs,” including dozens of fan backs with scroll-carved crests and bow-back side and armchairs, were marketed in the late 1780s at Charleston, South Carolina, and Cape Français, Haiti.[29]

Knowledge, production, and use of Windsor seating spread rapidly in the post-Revolutionary years. In 1779 Samuel Barrett of Boston requested his brother-in-law at Worcester, Massachusetts, to purchase at auction “6 Green Chairs (if made at Philadelphia).” Philadelphia Windsors were the standard by which similar seating was measured, although Boston craftsmen had yet to develop a local industry. The situation changed quickly, as indicated in April 1786 by Ebenezer Stone, who solicited custom at his shop on Moore’s Wharf, where he sold “WARRANTED Green Windsor Chairs . . . painted equally as well as those made at Philadelphia.” Three years later David Haven of Framingham sold “6 Dining Chairs Partly Painted,” or with a priming coat only. Haven also supplied “1/4 lb of Verdegrees & 2 oz of Wt [white] Lead” to make green paint, enabling his client to finish the chairs himself and reduce the cost. As indicated by Haven, verdigris, a copper acetate, was the pigment that produced the light green or light bluish green paint of early Windsor production (fig. 7). James Claypoole, a painter of Philadelphia, imported verdigris along with a variety of painting materials by 1750. Verdigris was still current for compounding green paint at the end of the century, as indicated in the records of Samuel Wing, a furniture craftsman of Sandwich, Massachusetts, whose papers contain a recipe for green paint signed by Obed Faye, a Windsor chairmaker of Nantucket. This recipe, like others, directed the preparer to begin with linseed oil boiled with a drying agent, such as rosin, litharge, or red lead, which was added to measured amounts of verdigris, finely ground in a drying oil, and white lead to achieve the desired intensity of color. Wing may have used Faye’s recipe to fill an order for chairs received in 1799 from Ebenezer Swift of Barnstable, who requested the craftsman to “give them chairs a good Green coler as you can.”[30]

By 1800 New York had been a center of Windsor chairmaking for at least three decades. As early as 1772 Elizabeth Rutgers’s household contained a green low-back Windsor chair, although whether a New York product or a Philadelphia import is uncertain. Like Philadelphia, New York developed a significant export trade in Windsor seating, which began to flourish in the 1790s. The “8 dozen green WINDSOR CHAIRS” from New York received in 1797 by merchant John Curry at Charleston, South Carolina, were a mere prelude to the explosion of activity that followed in that city. By the late 1790s Windsor furniture had long furnished East Coast homes, and some householders already engaged local craftsmen to repair or refurbish their seating. Stephen Girard of Philadelphia employed William Cox in 1787 for “Mendding and Painting 3 Old Windsor Chairs.” Shortly thereafter, Joseph Stone completed a repair for William Arnold at East Greenwich, Rhode Island, by putting “one post in a green Chair.” Business was brisk at the shop of Daniel Rea Jr., a painting specialist of Boston, who charged 2s. or 3s. for repainting a Windsor chair green.[31]

Green Windsors were prominent in the chair production of two generations of the Tracy family of eastern Connecticut from the late 1780s into the nineteenth century. Records identify a range of chair styles and describe several special customer options. Ebenezer Tracy Sr., the family head, trained three young men of the second generation who followed in his footsteps—a son, a nephew, and a son-in-law. The “Green Arm’d Chair” that Tracy exchanged for goods in 1788 with Andrew Huntington, a merchant of Norwich, is the earlier of two armchair styles listed in family records. A price range of 8s. to 12s. for this sack-back chair describes structural options beyond the basic frame. These included stretchers with embellished tips, three-dimensional knuckle arm terminals, and an extension headpiece above the back bow. More popular when introduced from New York after 1790 was the smaller, continuous-bow armchair, described by Amos D. Allen, Tracy’s son-in-law, as a “fancy” chair. Prices from 8s. to 15s. 6d. again dictated customer options: bracing spindles to strengthen the chair back; a fixed “cushion,” or stuffed seat, to cover the chair bottom; “edging,” or narrow painted lines, to accent and define structural features.[32]

The Tracy family produced two side chairs often finished in green paint, fan-backs and bow-backs. The bow-back Windsor often served as seating around a dining table, its compact design maximizing seating space. Appropriately, Amos D. Allen identified his bow-back Windsors as “dining chairs,” pricing them from 6s. 6d. to 14s., depending on customer selection of special features, as described above. Allen’s comprehensive order book also identifies another option in his side-chair production. Seat tops could be painted to contrast with the green or other principal color. The accounts identify “bottoms” of black and “mahog[an]y colour” contrasted with green. Ebenezer Tracy’s eldest son, Elijah, and his nephew Stephen also produced dining chairs, called simply “green chairs.” Elijah, like his father, did business with John Avery Jr., a clockmaker and metalworker, acquiring in 1799 and 1800 metalwork for turning lathes. Avery received a bed press (bedstead storage case) and two sets of “12 green Chairs,” at a unit price of 6s. 6d. Avery passed along eighteen of the chairs in sets of six to three customers at the same price.[33]

Information from household inventories provides another perspective on the green Windsor chair by identifying its geographic spread, the social level of its owners, and its disposition in the home. Inventories originating from New Hampshire to Georgia and westward to Kentucky describe the broad acceptance of Windsor furniture in early American life. As to who used this type of seating, the social spectrum is broad. Individuals with basic occupations included farmers and storekeepers. Artisan trades are described, in part, by furniture makers, metalworkers, millers, a shoemaker, and a butcher. Doctors and lawyers represented men of the professions. Records provide particular insight into the ownership and use of green Windsor chairs in the closely knit society on Nantucket Island during the three decades from the Revolution to the War of 1812, when forty-three inventories list chairs of this construction and color. Occupations relating to seafaring are prominent. Twelve decedents were “mariners.” Five individuals were merchants, and five more were “traders” engaged in the coasting trade. Several coopers, a ship’s carpenter, and a block maker also owned green Windsor chairs. Several owners were termed “gentlemen” at their deaths.[34]

Many green chairs listed in Nantucket households appear to have been used on the first floor—a few in parlors but many in a room reserved for dining. “Table chair,” an alternative term for “dining chair,” appears in some records. When Oliver Spencer, a “trader” of Nantucket, died in 1794, appraisers listed “6 Green Table Chairs” among his furnishings. Several records describe a distinctive Windsor chair with a tall, reclining braced back that originated on the island or nearby (fig. 8). Henry Clark, a mariner, owned a “Great Green Chair & Cushion [Green]” in 1801, the cushion suggesting that his chair was designed for taking his ease. Two other chairs, one belonging to Jonathan Burnell, a merchant, and one to Peter Coffin, a yeoman, are each described as a “Mans Green Chair,” suggesting the chairs had distinct, identifiable features linking them with the head of a household. Tall chairs of this type appear to have been located on the first floor, placing them near the principal hearth to which they could be drawn for warmth in cold weather. A few Nantucket inventories locate smaller green Windsors in upstairs chambers.[35]

Bedchambers also were the choice of off-islanders for the placement of green Windsor chairs. Elias Hasket Derby, a wealthy merchant of Salem, Massachusetts, furnished his southwest and southeast chambers in this manner. Another group of “6 Green Chairs” was located in his counting room “on the wharf.” Upper and lower hallways, or passages, were depositories for a total of fourteen green Windsors in the New York home of Johannah Beekman before 1821. The “large entry” in the Newburyport, Massachusetts, home of Captain Jonathan Dalton was the site of a “high green [arm] Chair” two decades earlier. Windsors placed in entrance halls served as repositories for outer clothing when individuals entered the house. The chairs also provided supplemental seating for the adjacent dining room and parlor. The garret in many homes, including that of Beekman, served as storage for surplus seating and “old” chairs. Some New England inventories list a “keeping room,” a family sitting room, or parlor, whose function at times was expanded to include dining. In the home of Daniel Danforth, a shopkeeper of Hartford, Connecticut, “6 Green dining chairs” stood in the “Lower Keeping Room” in company with a “Breakfast Table.”[36]

Other inventories describe special options in green Windsor seating. William Chappel, a farmer of Lyme, Connecticut, owned “1/2 Doz Green Chocolate bottom windsor Chairs.” Rufus Porter in “The Art of Painting” described chocolate as a mixture of lampblack with Venetian red. At New Haven Eneas Munson, a physician, who like Chappel died in 1826, owned “10 Green & Black Chairs.” Whether black described the seat color or the ornament is unclear. Seven years later at Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, the inventory of chairmaker Thomas Devor itemized “2 Green Strip[e] chairs.” That the chairs were ornamented is clear, but was green the color of the chairs or the decoration? Other inventory data suggest green was the ground color. Stuffed seats were a more expensive option. To the construction and painting costs of the wood-seat chair was added a charge for stuffing materials, a finish cover (leather or cloth), and labor. Stuffing a seat, on average, almost tripled the price of a Windsor. An inventory drawn about 1816 for the estate of Gerrit Wessel Van Schaick, a resident of Albany, New York, describes an unusually large set of stuffed Windsor chairs as “1 3/12 Dozen Green Chairs with Stuffed bottoms.” Insight on suitable cloth covers for Windsor chairs can be found in the estate records of General George Mason of Rockland County, Virginia: “Eighteen Windsor chairs with green Moreen bottoms” and “Two armed ditto covered with ditto.” Moreen, a worsted woolen, was popular for upholstery in the period of this study.[37]

Chairmakers’ inventories from the second quarter of the nineteenth century illuminate new options available in green Windsor seating late in the period under study. Ebenezer P. Rose, a craftsman of Trenton, New Jersey, had a dining room furnished with “10 Sage Col[or] Chares” still valued at $1.00 apiece in 1836 at his death. Sage color is defined as a gray-green, although records are silent on how to compound paint of this hue. Thomas Sheraton offered a clue in his Dictionary, when identifying green pigments suitable for use in oil. One choice besides the ubiquitous verdigris was “terra verte,” a green earth that was refined to produce a soft grayish green pigment.[38]

When Charles Riley of Philadelphia died in 1842, appraisers itemized an estate with a shop in full production. Olive green, an important color, covered fifteen six-chair sets in two styles—“ball backs” and “Baltimore backs.” The ball-back chairs had bent backs with short ball-centered spindles at the lower back. The Baltimore-style chairs had large tablet tops set on turned posts or rabbeted to sawed Grecian posts (fig. 9) (see fig. 29). Rufus Porter provided two recipes in his Scientific American article for duplicating this dull yellowish green color. One is a mixture of blue, red, and yellow, the other a combination of lampblack and chrome yellow. The forty-three pounds of chrome yellow in Riley’s shop suggests his choice of recipe. Also in the shop was “1 Sett Pea Green [Chairs].” Each of two recipes indicates this color was little different from the light green that had been used on Windsor chairs for almost a century. Each recipe calls for white lead with the addition of verdigris or Paris (French) green. Of the two pigments, verdigris is more common in records.[39]

Painted fancy chairs with woven seats of rush or cane were introduced in America before 1800 through English imports and immigrant craftsmen. Two London chairmakers, Samuel Claphamson and William Challen, settled at Philadelphia and New York, respectively. Claphamson advertised “fancy” and “bamboo chairs” in January 1785. When changing addresses in 1797, Challen assured his New York customers he was prepared to supply “every article in the fancy chair line, executed in the neatest manner, and after the newest and most approved London patterns.”[40]

Like other vernacular seating, fancy-chair construction frequently is unidentified in records. Unit price, pattern, and decorative treatment, if indicated, can provide insights. Cane seats were less common than rush seats and also more expensive. The green of the fancy chairs discussed here is without further description except for “3 Pea green cane seat chairs” in the household of Lambert Hitchcock in 1852 at Unionville, Connecticut. As stated, pea green could have been prepared using the pigment verdigris, although, according to Sheraton, green paint made with verdigris might be manipulated to vary the color: “In painting chairs with a green ground, common verdigrise may be used. . . . The green may be compounded to any shade by means of white lead, and king’s yellow, both of which must first be ground in turpentine out of the dry colours.”[41]

In general, fancy chairs were priced higher than Windsors. Thomas Howard, a Providence, Rhode Island, craftsman, noted the price range in 1822, when advertising a new shipment of seating furniture from the New York City area: “4000 Fancy and Windsor Chairs, of a superior quality, new and handsome patterns, from 50 cents to five dollars.” Windsor chairs priced at $2.00 or more and fancy chairs from $3.00 usually represented high-end seating, often distinguished by special structural features, elaborate decoration, and/or extensive gilding. Fancy green chairs made in 1816 at Newark, New Jersey, by David Alling had cross backs (see fig. 19), slat backs, or ball backs, the last-named pattern notable for a horizontal ball-accented fret across the back (see fig. 26). Earlier, in 1810, Nolen and Gridley, warehousemen of Boston, advertised imported New York chairs of green and gold with “double Cross Backs.” Top-of-the-line fancy seating might exhibit extensive hand-painted ornament or complex bronzework (stenciling), either accented with gilding.[42]

Yellow Chairs

Yellow was a new color available for the surfaces of Windsor seating at Philadelphia in the post-Revolutionary period. Its appearance in the market in the 1780s coincided with the introduction of a new side chair having a back bow anchored in the seat, a pattern also described at Philadelphia as an oval-back Windsor, and turned work simulating the jointed character of bamboo. Providing inspiration for the new chair back was formal seating furniture constructed locally after neoclassical oval-back designs current in England. Six new bow-back chairs painted yellow and valued at 9s. ($1.50) each stood in the shop of John Lambert at his death in 1793 during a yellow fever epidemic that raged in Philadelphia. The bow-back Windsor quickly became the popular chair for dining.[43]

The common yellow pigment of the period was patent yellow, a bright chloride of lead (fig. 10). Formula improvements about 1800 using additives such as antimony and bismuth enhanced the color’s “brilliancy and durability.” This likely was the “new discovery in the preparation of Paints” advertised by chairmaker Lawrence Allwine in 1800 at his Philadelphia “Patent Paint Ware House.” By 1804 Harmon Vosburgh retailed “Patent Mineral Yellow” of his “own manufacture . . . warranted equal to any ever imported, and 50 per cent cheaper” at his New York varnish and patent yellow manufactory. Patent yellow remained the standard for a decade or more, until the bright new chrome yellow, a lead chromate, seized the market. By 1818 William Palmer, a fancy chairmaker of New York, “succeeded in making this new and beautiful PAINT a permanent color.”[44]

The fashion for yellow dining chairs was disseminated from Philadelphia. James Chase of Gilmanton, New Hampshire, sold “Six Dining Chars painted yallow” in 1804 to Reuben Morgan of Meredith for 7s. 6d. ($1.25) the chair. Earlier, Amos D. Allen had sold six yellow chairs to Dr. Samuel Lee, a neighbor at Windham, Connecticut. When Lee died in 1815, the dining chairs were still in his home. Yellow dining chairs trimmed in blue were perhaps more popular than plain ones at Solomon Cole’s Glastonbury shop near Hartford, where the chairmaker priced his ornamented seating about 25 percent higher than plain chairs. New York estates of the late 1790s and early 1800s that describe yellow Windsors, some trimmed in green or white, provide information on the broad socioeconomic background of the owners of yellow Windsor seating: two decedents were “gentlemen”; other owners included a merchant, lawyer, silversmith, shipmaster, and blacksmith. At Boston Daniel Rea Jr. used more descriptive language when recording two groups of chairs painted “Patent yellow”: one group was “Creas’d in Green,” highlighting the “bamboo” grooves, while the other was “Strip’d.” Providing additional insight into the range of decorative options is a notice by Ephraim Evans at Alexandria, Virginia, in 1802 following the theft of a set of chairs from his shop: “STOLEN . . . Six round back Chairs, painted yellow, tip’d with black, the seats painted mahogany colour.” At Saybrook, Connecticut, the estate of cabinetmaker Samuel Loomis contained yellow Windsor chairs with painted “black bottoms.” Another option, available at the shop of Amos D. Allen, was stuffed seats, or “green cushions,” probably covered in moreen.[45]

Yellow paint on Windsor chairs was not limited to the bow-back style. Captain John Derby of Salem, Massachusetts, purchased yellow fan-back chairs in 1802 for $1.39 apiece. Solomon Cole’s chair production at Glastonbury, Connecticut, included yellow fan-backs embellished with green ornament. The order book of Amos D. Allen of Windham describes another chair style in 1799: “6 Fancy [continuous-bow] Ch[air]s without braces, Edged [pinstriped] . . . Yellow.” Cargo lists of the early nineteenth century provide insights on yellow chairs in the new square-back patterns and the scope of the export trade in seating furniture. Itemized in a mixed cargo shipped in 1801 to Havana, Cuba, by Philadelphia chairmaker Anthony Steel are “One Dozen yellow Double back Square tops,” a pattern with curved double rods, or “short bows,” forming the crest. When the ship George and Mary left Providence, Rhode Island, in 1810 with a cargo from New York for sale at Buenos Aires, Argentina, the invoice of furniture included “12 [Bent Back] Yellow [Winsor Chairs]” valued at $1.25 apiece. New York patterns also were part of a chair consignment containing yellow Windsors shipped to Nathan Bolles of New Orleans in 1819 by David Alling, proprietor of a chair manufactory at Newark, New Jersey. Itemized are Windsors with slat backs and plain spindles or organ spindles, the last-named feature a distinctive New York pattern (see fig. 26).[46]

Supplementing bright yellow seating in the market were Windsor chairs painted in paler tones of yellow (fig. 11). “Straw” and “cane” were terms in use, although both probably identified the same color, the terminology a matter of individual shop practice or preference. Sheraton, who provided a recipe for straw-colored paint in his Cabinet Dictionary (1803) but none for cane color, intimated the yellows were the same, when describing the canes used in fancy-chair seats as “of a fine light straw colour.” The base for formulating straw color was white lead, the pigment varying, depending on recipe date. Sheraton recommended king’s yellow, a yellow orpiment. In Directions for House and Ship Painting of 1812, Hezekiah Reynolds named spruce yellow, whereas Rufus Porter, writing in 1845, preferred chrome yellow. Chrome yellow is bright, whereas the other recipes produced a light brownish yellow. Reynolds’s spruce yellow is an ochre, or earth, and Sheraton recommended as an additive to his formula “a little Oxford ochre.”[47]

References to straw- and cane-colored paint occur in documents originating in both New England and Philadelphia, although use of one or the other term appears to have been shop specific, based on limited evidence. Straw color in reference to paint was a viable term from the 1790s, whereas the first use of cane color dates after 1800. Both terms were current until almost 1850. The popularity of straw- and cane-colored paint is explained indirectly by Sheraton in defining the word “BAMBOO”: “A kind of Indian reed, which in the east is used for chairs. These are, in some degree, imitated in England, by turning beech into the same form, and making chairs of this fashion, painting them to match the colour of the reeds or cane.” Simulated bamboowork appeared in America in the mid-1780s with the introduction of the bow-back Windsor at Philadelphia. Yellow paint helped to promote the exotic background of the new turned style, although craftsmen soon offered a broad palette of color choices for “bamboo” seating.[48]

An early reference to straw-colored chairs can be found in the shipping records of Stephen Girard of Philadelphia, who in 1791 purchased two dozen Windsors of this color from William Cox at $1.67 each, probably for shipment to Haiti in the Caribbean. Later, between 1818 and 1832, Luke Houghton of rural Barre, Massachusetts, framed five sets, comprising six or twelve straw-colored chairs, each chair priced from 83¢ to $1.50, suggesting there were options in structural pattern and decoration. Philemon Robbins of Hartford, Connecticut, noted the sale of six straw-colored chairs in 1836, although his customers appear to have favored bright yellow seating.[49]

In the 1810s Stephen Girard, formerly a customer of William Cox (d. 1811) for straw-colored chairs, patronized the shop of Joseph Burden, who on one occasion supplied him with “4 Dozen Cane couloured Chairs” at $17.00 the dozen and four matching settees, each priced at $10.00. The furniture was placed on board the ship Rousseau bound for China via South America, where it was sold. The firm of Verree and Blair of Charleston, South Carolina, identified a less successful waterborne venture in announcing the sale of cane-colored Windsors in 1807 from the ship Thomas Chalkley, which “put into . . . port in distress, on her passage from Philadelphia to St. Thomas.” Chair manufacturer David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, also identified cane-colored chairs as a popular commodity during the 1810s, when Moses Lyon was his painter and ornamenter. Itemized in Lyon’s work are cane-colored Windsors of three spindle types: “plain” (cylindrical), “organ,” and “flat.” Organ spindles, located in the lower backs of chairs, are cylindrical with thick rounded tops and slim lower tips like organ pipes (see fig. 26). The common flat spindle is of so-called arrow shape. Lyon also “tipped,” or pinstriped, several sets of cane-colored Windsors.[50]

Cream color, a pale yellow tint that equaled the popularity of straw- and cane-colored paint, was selected occasionally for Windsor seating in the early nineteenth century (fig. 12). The closeness of cream color to the yellow palette is demonstrated in the accounts of Philemon Robbins of Hartford, Connecticut, who in 1834 sold Thomas C. Perkins “3 yellow Chairs plain colour to border on a cream colour.” In his recipe for cream-colored paint, Hezekiah Reynolds combined spruce yellow (an ochre) with white lead in the proportion of one part to thirty to achieve a “yellow tinge.” Reynolds used the same ingredients in straw-colored paint, altering the proportions to one part to ten. Elijah Eldredge recommended the addition of stone yellow, an ochre, to white lead in compounding cream-colored paint, resulting in a tint similar to that achieved by Reynolds.[51]

Six “Cream Color’d Chairs” stood in the Danbury, Connecticut, home of furniture maker Ebenezer Booth White in 1817. Sales of similarly painted Windsors at the Connecticut shops of Thomas Safford and Silas E. Cheney further describe a modest interest in this light color. Titus Preston of Wallingford provided more detail in 1801, when Polly Scovel acquired two six-chair sets of cream-colored Windsors. Both groups had striped decoration, and one set had painted “green bottoms” that likely reflected the color of the striped ornament. Preston’s price of $1.17 a chair was the same as that recorded by Safford and Cheney. Within two years, David Russell recorded the sale of cream-colored chairs with mahogany-colored seats at Winchester, Virginia. Later, in 1842, Charles Riley’s probate record describes an extensive shop inventory at Philadelphia that lists “1 Sett Cream Col’d Ball Back [Chairs].” The pattern probably identifies Windsors with tablet tops (crests) in the Baltimore style and short ball-centered spindles in the lower back below a cross rail.[52]

Supplementing Windsor seating, many chairmakers framed fancy chairs to satisfy a market that preferred higher-end painted and decorated furniture. Records collected for this study include references to yellow, cane-colored, and cream-colored fancy seating, colors available at one time or another at David Alling’s New Jersey chair manufactory. During the late 1810s, when Alling made yellow and cane-colored seating, he also produced fancy chairs and a few Windsors in a painted finish he called “Nankeen.” The term possibly can be equated with Alling’s later use of “cream color” in the 1830s. Nankeen was a popular cotton cloth of pale, light brownish yellow produced originally at Nanking, China, and exported through the port of Canton, where after the Revolution American merchants purchased the textile directly. Although Alling is the only person in this study to identify Nankeen-colored paint, the term also may have had currency at New York, where Alling had frequent contact by water with suppliers and craftsmen. Nankeen-colored seating available at Alling’s shop included slat-back and ball-back fancy chairs; the Windsors had organ spindles.[53]

When Elizur Barnes of Middletown, Connecticut, charged Arthur W. Magill 67¢ in 1822 for “Painting 8 Seats yellow,” he identified rush-bottom fancy chairs. Sheraton advocated painting rush seats because, as he explained, it “preserves the rushes and hardens them.” Sheraton commented, alternatively, on the use of canework in furniture, noting that it introduced “lightness, elasticity, cleanness, and durability.” The light straw color of cane further interested him because it provided “the most agreeable contrast to almost every colour it is joined with.”[54]

Fancy chairs painted yellow, among other colors, were available in the mid-1830s at the Hartford, Connecticut, manufactory of Philemon Robbins and partners, whose accounts describe an active business association with suppliers of seating furniture, among them Lambert Hitchcock. Hitchcock shipped hundreds of chairs to Robbins from his factory in Hitchcocksville (Riverton), and other stock was available in the mid-1830s at Hitchcock’s chair store in Hartford. In September 1835 a Mr. Churchill purchased “2 cane seat yellow Hitchcock ch[airs]” from Robbins for $3.00. A previous order for another customer had required that Robbins “send to M[essrs] Hitchcock for 18 cream color Roll top cane seat chair[s] . . . with out gilt but d[ou]ble . . . bl[ack] stripe.”[55]

Like Windsor furniture, fancy seating was a commodity of waterborne commerce, albeit a more modest one. Yellow-painted chairs are named in several records dating to the 1810s. On June 1, 1814, the New York shop of Alexander Patterson prepared “12 Yellow & gilt chairs” priced at $5.25 the chair for shipment up the Hudson River on the sloop Columbia to Gerrit Wessel Van Schaick, a resident of Albany. Packing the chairs for shipment cost an additional $1.50, although no further detail is provided. With woven seats already in place (as per chair cost), the chairs probably were nested in bundles of two, the seats in contact, vulnerable surfaces wrapped with sheeting or haybands, and the exterior wrapped with straw matting tied in place.[56]

David Alling, a manufacturer of Newark, New Jersey, from about 1800 until 1855, derived considerable income from his export business in seating furniture. In 1819 and 1820 he sent four large consignments of fancy chairs of mixed pattern, color, and ornament to his agent in New Orleans. Among the shipments were three sets of handsome yellow fancy chairs, each one-dozen set priced at $50.00. Gilt decoration enriched all three sets, and one set also had “bronsed” ornament. Alling’s records also describe the structural features of the chairs: one set had “dimond front rounds,” or front stretchers centered by a small, diamond-shaped tablet (fig. 13); another set had slat-style front stretchers (see fig. 23) and legs flaring outward at the base; the third set had distinctive New York ball backs, with narrow cross rods anchoring two rows of small beads (see fig. 31). Stephen Girard’s maritime pursuits carried his vessels well beyond North America, and his Philadelphia suppliers provided a variety of seating furniture to meet the tastes of his markets. In July 1816 the ship North America left the city carrying 128 fancy chairs, including twenty-two side chairs and six armchairs described as “[Fancy chairs] bent [back] Cane colour.” A principal destination was Port Louis on the Isle de France (Mauritius), east of Madagascar, where the entire cargo of chairs was landed. The vessel then proceeded to India and the East Indies.[57]

White Chairs

White, along with black, green, red, and blue, was a paint color identified as suitable for Windsor chairs in an invoice book kept by Joseph Walker, supercargo on the sloop Friendship in 1784 on a voyage to Savannah, Georgia. Aside from green, all the colors were newly fashionable. The principal ingredient in white paint was white lead, a lead carbonate, known in its pristine and brightest form as flake white. Spanish white, or whiting, an alternative pigment made from clay, was sold as a finely powdered chalk. Painters sometimes used Spanish white as an adulterant in lead paint, if, indeed, they did not employ a more common chalk.[58]

Other references to white paint followed. In the mid-1780s Benjamin Franklin furnished his home in Philadelphia with two dozen white Windsor chairs. The purchase likely occurred in 1785, on his return from national service in France, or in 1786, when he enlarged his residence on Market Street. The chairs were inventoried at his death in 1790. Other records from the 1790s describe increasing local interest in white Windsor seating. General Henry Knox, secretary of war in the new federal government located at Philadelphia during the 1790s, patronized William Cox in 1794 for twelve white bow-back, or oval-back, side chairs at $1.87 apiece and “12 Oval back’d white color’d Arm chairs with Mahogany Arms,” the $3.12 unit price a reflection of the use of mahogany in the construction. Knox’s purchase of similar seating from Cox the following year for triple the number of side chairs and armchairs was made at price increases of 11 1/4 and 6 3/4 percent, respectively. Six settees accompanied the seating; two were priced at $7.50 apiece, the remaining four at $15.00 apiece. The dual pricing suggests the long seats accommodated two and four people, respectively.[59]

By 1796 the price of Windsor chairs at Philadelphia had increased again by 16 3/4 percent for side chairs and 11 3/4 percent for armchairs. William Meredith, a lawyer and banker of the city, purchased white oval-back Windsors from John Letchworth that year at $2.50 and $3.75 apiece, probably to furnish a dining parlor. Something beyond plain white seating is suggested in the prices of all these groups of Philadelphia chairs. Although the dates are too early for gilt ornament, the “creases” of the bamboowork and the grooves of the seats and bows probably were “picked out” in a contrasting dark color using a slim brush called a pencil.[60]