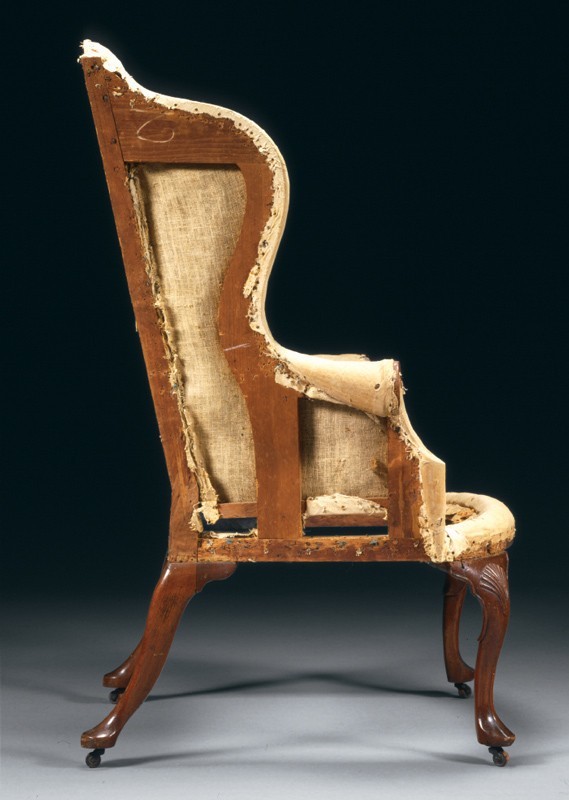

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple with oak and white pine. H. 49 3/4", W. 31 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Colonel and Mrs. Miodrag Blagojevich, 1977-336.) This chair retains part of its original wing rolls and foundation linen and has remnants of the original wool show covers. The current wool fabric was dyed to match those remnants and fitted with a nonintrusive upholstery system developed by Colonial Williamsburg conservator Leroy Graves. The upholstery and conservation of this chair will be featured in his forthcoming book, The Upholstery Craft in America and England, 1750–1820: Reading the Evidence.

Small wing chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1710. Maple and Linsey-woolsey. H. 47", W. 27", D. 33". (Collection of Shelburne Museum. 3.3-62. Photo, Sanders Milens).

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1710. Maple with cherry and white pine. H. 44 1/4", W. 25 3/4", D. 32". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

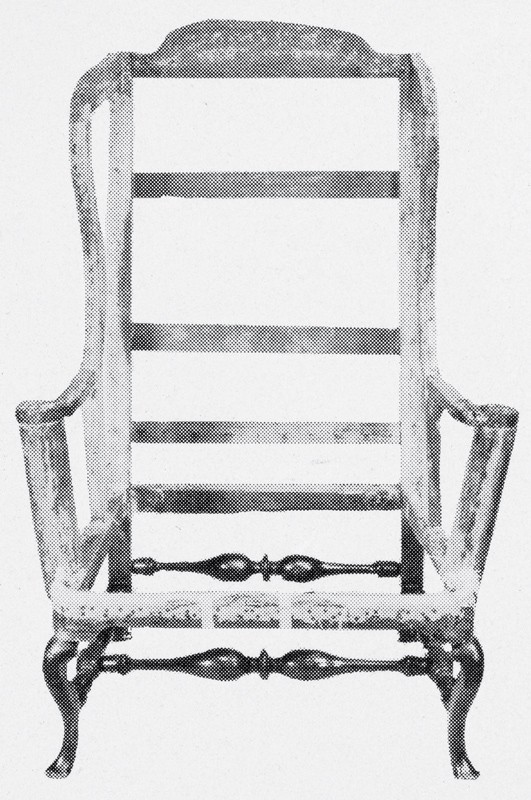

Overall of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 3, showing the frame stripped before upholstery. (Photo, Robert F. Trent.) This view shows the plywood prostheses added to the wings to compensate for later chamfers on the inside edges of the wings and for losses to the tops of the upper wing rails.

Detail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 3, showing the joint between the wing stile and the arm (Photo, Robert F. Trent.)

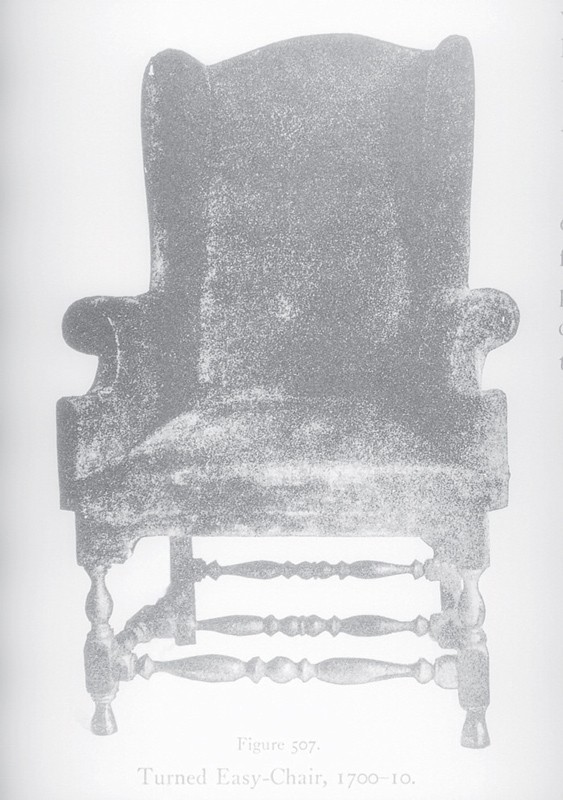

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1715. Maple with pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 3rd ed., 2 vols. [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926], 2: 65, fig. 507).

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple with maple and oak. H. 49 1/8", W. 29", D. 32 7/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Craig McDougal.) This chair has a nonintrusive upholstery system developed by Colonial Williamsburg conservator Leroy Graves.

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1740. Maple with white pine. H. 47 1/2", W. 35", D. 36". (Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, gift of Jane B. and Margaret C. Stearns, 1981.54.)

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 9.

Side view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 9.

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1735. Maple. H. 48", W. 33 3/4", D. 29". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, B58.104.) Conservators Christopher Shelton and Steve Pine executed this nonintrusive upholstery during the mid-1990s.

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1735. Maple with maple, oak, birch, beech, and white pine. H. 48 1/4", W. 30 11/16", D. 34 6/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III, 1999-62-1.) The deck appears to be an old replacement.

Side view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 13. The edge roll continues around the upper arm scroll. On most easy chairs, edge rolls diminish as soon as they pass toward the outside of the frame.

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 13.

Overall of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 13, showing the frame after the stuffing was removed.

Overall of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 1, showing the frame with original edge rolls and sackcloth on the wings.

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1740. Maple with white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (John Kenneth Byard Collection, Archives of American Art, Decorative Arts Photographic Library, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1735. Maple with oak. H. 48 7/8", W. 27 1/4" (seat), D. 22 1/2" (seat). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 50.228.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Conservator Nancy Britton executed this nonintrusive upholstery in 2000.

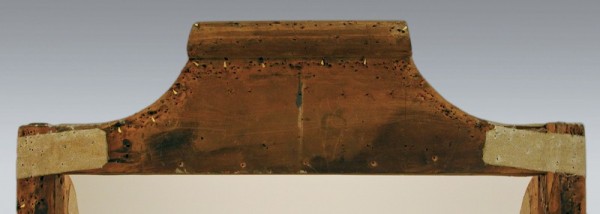

Detail of the crest of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Nancy Britton.)

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1740. Maple with pine. H. 49", W. 31 3/4", D. 31 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The applied toes and scrolled portion of the crest are restored. This chair retains flanges on the back edges of its scroll feet, indicating that carved laminations were originally present. The scroll feet of all Boston baroque easy chairs were made in this manner.

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was made with a great deal of rake at the back.

Detail of a red wool fragment trapped under a wrought nail on the underside of a vertical arm cone on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Settee, London, England, 1700–1710. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Charles Latham, In English Homes, 3 vols. [London: Country Life, 1907], 2: 214.) This settee is in Lyme Park, Disley, Cheshire.

Settee and armchair, London, England, 1700–1710. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Charles Latham, In English Homes, 3 vols. [London: Country Life, 1907], 2: 90.) London cabinetmaker Philip Guibert made these objects, along with a more elaborate set of seating furniture, for Thomas Osborne, Duke of Leeds. The settee and armchair were originally used at Kiveton in Yorkshire.

Easy chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Walnut and maple with white pine. H. 47", W. 33 1/4", D. 28". (Courtesy, Colonel Daniel Putnam Association, Brooklyn, Connecticut; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair may have belonged to Godfrey Malbone, who moved from Newport, Rhode Island, to Brooklyn, Connecticut, in the late 1760s.

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26, showing the false crest created by cord and binding tape. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the diamond-and-snowflake, silk-and-wool binding tape behind an arm cone on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the seat rail on the right side of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26, showing the polished steel nails holding the flat tape. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of an arm roll and cone on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26, showing the edge roll on the front seat rail and the seat deck with the cushion removed. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the boxing and bound seams of the cushion on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the rounded outer edge of a rear post on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the walnut-color stain on the left rear foot of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The foot and post are cut from one piece of maple.

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1730–1740. Walnut and maple with white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Israel Sack, Inc., advertisement, Antiques 98, no. 2 [October 1970]: 472.)

Overall of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 36, showing the stripped frame with no stay rail and three original webbing strips.

Easy chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1730. Walnut with oak, pine, and tulip poplar. H. 47 1/2", W. 33 3/4", D. 28". (Courtesy, Christie’s.)

Rear view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 38.

Side view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 38.

Detail of the right front leg of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 38.

In the collecting history and literature of American furniture, Boston baroque easy chairs (fig. 1) have never received the acclaim of their later colonial equivalents. The high point of interest in early Boston easy chairs was during the 1950s, when collectors in the circle of Katherine Prentis Murphy (1882–1969) competed vigorously to acquire them. Owing to the notoriety of her famous checker-floored period rooms, most of which featured early seating, Murphy influenced the acquisition of easy chairs that eventually entered the collections of Bayou Bend, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Colonial Williamsburg; the Shelburne Museum; the Winterthur Museum; and the New Hampshire Historical Society. She seems to have favored covering easy chairs in Spanish nineteenth-century machine-woven hemp and wool tapestries, large quantities of which were acquired by American antique dealers in Spain and marketed to American collectors as seventeenth-century Irish stitch. Two chairs covered by Murphy in this sort of textile (Shelburne Museum and New Hampshire Historical Society) memorialize her treatments.[1]

More recent study of the twenty-five known easy chair frames has concentrated on original upholstery techniques and their replication, an exercise hampered by the rarity of surviving upholstery foundations; only four chairs have or retained fragments of original stuffing, webbing, sackcloth, or edge rolls into the twentieth century. This article will analyze the frames and summarize recent research on how these chairs were upholstered and trimmed. The author has upholstered three of the twenty-five known frames, and conservators Leroy Graves, Christopher Shelton, Steve Pine, Nancy C. Britton, and David de Muzio have formulated similar, albeit nonintrusive, treatments for easy chair frames conserved by them or under their supervision. One important goal is to establish period sources for how such chairs were upholstered. As this article will show, reconstructing period upholstery practices requires study of both English and Boston seating, and many questions remain about appropriate treatments.[2]

The latest research on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English upholstered seating by Adam Bowett and Lucy Wood suggests that American scholars and collectors have tended to date Boston baroque easy chairs too early. Heretofore the usual earliest date assigned to them was circa 1695. Bowett proposes that the earliest chairs of the advanced form date circa 1705. This observation is consistent with more recent American scholarship, which posits that Boston chairmakers began offering sawn cabriole legs as an alternative to turned forms by 1725, and that cabriole legs with turned feet and rounded contours modeled with shaves and files emerged as an option by 1730. The introduction of new leg designs did not mean that older types were immediately displaced. Indeed, easy chairs with cabriole legs and what were occasionally described as “scroll feet” during the period may have been made throughout the 1730s. That decade appears to have been a time of experimentation, during which Boston furniture makers adapted a wide variety of imported designs. What we consider the standard Boston easy chair—with compass seat, vertical arm scrolls, turned feet, and modeled cabriole legs—may not have come into widespread production until the mid- to late 1730s, when patterns for that form were distributed throughout the Boston joinery shops responsible for making them.[3]

The Earliest Boston Easy Chairs

Three easy chairs stand at the beginning of the Boston design tradition and are the earliest known Anglo-American examples. Although these objects have been regarded as idiosyncratic, their frames have many English cognates dating back to the 1670s. The two earliest frames are akin to early baroque English sleeping chairs, essentially open armchairs to which hinged back frames with cheeks or wings were attached. They also have an affinity with Cromwellian couches, some of which were fitted with squared, upholstered cheeks or wings hinged atop the arms. The two Boston examples have flat, squared arms supported by bracketed stumps set back from the front legs, balloon-shaped or single-curve wings, and turned front stretchers. The chair illustrated in figure 2 has colonial-revival upholstery with quilts used as the show covers; this ahistorical treatment is preserved as a memorial to the Shelburne Museum’s founder, Electra Webb. In 2000 the author partially de-upholstered the junction of one wing and one back post and probed the rest of the frame to confirm that the chair is period and virtually identical to the example shown in figures 3 and 4. The latter chair was owned for many years by Brentwood, New Hampshire, dealer Roger Bacon. Furniture historian Benno M. Forman examined and photographed the chair at Bacon’s shop circa 1970 and subsequently illustrated it in several publications. Upholstery components visible in Forman’s photograph are not original but probably date from the neoclassical period.

An image of the stripped Bacon frame taken before the author reupholstered it in 2000 reveals most of the construction details (fig. 5). At the time the image was taken, thin plywood prostheses had been added to the interior surfaces of the wings, to compensate for later chamfers on the inside lead edges of the wings, as well as losses to the top rails of the wings. Questions surrounding the junctures of the wings and rear posts on the Bacon chair prompted the author to investigate the example illustrated in figure 2. The maker of the Bacon frame simply nailed the wings to the rear posts from behind, in a manner that threw the authenticity of the wings into doubt. The mortise-and-tenon joints at those locations on the chair illustrated in figure 2 suggest that the nailed joints of the frame on the chair owned by Bacon likely resulted from an assembly error and that the maker may not have been familiar with conventional easy chair joinery. Another odd feature of the chair illustrated in figure 3 is the termination of the wings on the arms. Because the arms continue back to the rear posts, the maker chose to terminate the lower wing rails on the arms (fig. 6). Rather than using internal, pinned mortise-and-tenon joints at those locations, the maker employed through-tenons that pass below the arms and are secured by round, wedgelike, exposed pins.

All early baroque easy chairs lack stay rails (lower back rails) and tacking struts in the draw-throughs (sometimes called “tuck-aways”) of the wings and arms. The absence of these features makes laborious bast tacking (temporary tacking) necessary when webbing, lining, and stuffing the frame. None of the draw-throughs can be tacked permanently until the show covers have been applied. New England chairmakers began incorporating stay rails in the 1730s, but, unlike their Philadelphia counterparts (figs. 38–41), they neglected to use tacking struts in the draw-throughs until the neoclassical period.

In the absence of any comparable Boston easy chairs, the author studied early English easy chairs, as well as open armchairs with wings that survive only in aristocratic contexts in Britain but may have been more widely used in the period. The original upholstery techniques and contours of that sample group informed the stuffing, tailoring, and trimming devised for the Bacon frame (fig. 3). These English treatments mandated not only stuffing the wings and arms as a single unit but also rendering the padding on top of the arms as a separate unit. Neither of these decisions seem to be controversial; however, nineteenth- and twentieth-century commercial upholsterers often stuffed the wings and arms of such chairs as separate units. They might also have elected to carry the arm panel up and over the top of the arm. This is perhaps less obviously ahistorical, given the preservation of shaped wooden arms on two Boston Cromwellian couches and a Salem Cromwellian armchair, in which the arms received no stuffing and covers were applied directly on the wood. A final detail of the author’s treatment that was considered odd at the time was the extensive use of tape over cord to trim many of the seams, in addition to flat-sewn tape running around the front and sides of the bottom of the frame. This treatment reflects period usage but must be inferred in these earliest Boston chairs from English chairs and from later Boston seating with original upholstery.

Design problems are evident in the two earliest frames (figs. 2, 3). First, the front stretcher inhibits the sitter from drawing his or her heels under the frame. Many contemporary English easy chair frames have a carved and pierced front stretcher, which seems even more dysfunctional. Second, the balloon profile of the wings prevents the sitter from drawing his or her elbows back on the arms. While these two features swiftly passed from the design tradition, others did not. All these easy chairs are made with continuous back posts and rear legs. Inevitably, this usage imposed several limitations on the makers. They did not provide the frames with adequate heels to prevent them from tipping backward, choosing, rather, to give the frames dramatic layback, sometimes as much as eleven or twelve inches (figs. 21, 22). In other words, the rear edges of the crests are set back eleven or twelve inches beyond the rear seat rails. The results are obvious to modern historians and conservators: a great many of these chairs flipped over backward, and several of them have repaired or replaced crests. A final problem with these frames is that they are remarkably narrow, barely twenty-four inches wide in the rear elevation. Undoubtedly, this dimension derived from open armchairs, which are usually twenty-four inches wide at the front. However, the wings of the easy chairs are always stuffed such that the combined thickness of the wooden wing components and the edge rolls is 1 7/8", the same dimension as the stock used to fabricate the posts of chair frames from the mid-seventeenth century until the 1740s. As a result, the sitter’s shoulders are effectively confined within a twenty-inch space at the back, assuming that the stuffing of the wings did not have considerable loft or crown. While progressive modifications of these easy chairs eliminated some compositional problems, all the early baroque chairs illustrated here are painfully narrow for modern sitters.

The third early Boston easy chair, which belonged to Boston collector Hollis French, incorporates some progressive features (fig. 7). It has flat-headed arches on the undersides of the front and side seat rails, double-scroll arms that are tangent with the forward corners of the frame, and countercurved wings. The arched crest rail is a relatively generic detail, although it does not rise as high as those on later Boston baroque easy chairs and is chamfered on the upper lead edge to aid in fairing the stuffing. This arched form presents quite a contrast when compared with the rudimentary, raised crests of the chairs illustrated in figures 2 and 3, which do not have half-round responds glued to the rear surfaces to complete the roll.

The turnings of these early easy chairs have an obvious and pertinent relation to those of Boston leather chairs, but one hesitates to deem such ornament standardized. In the evolution of the easy chair between roughly 1705 and 1735, makers experimented with a number of ornamental schemes, some of which defy ready explanation. The same master upholsterers who designed leather chairs also designed easy chair frames, the same turners provided requisite components, and the same joiners fabricated and assembled their frames. London easy chair frames must have influenced the turned vocabulary, and, in the case of abstract Doric columnar turnings, the influence of English and Boston cane chair frames cannot be discounted.[4]

Mature Boston Easy Chairs of the Blocked Leg and Square Cabriole Types

American furniture collectors have always coveted a particular model of Boston baroque easy chair, epitomized by an example acquired by Miodrag and Elizabeth Blagojevich in the 1950s and subsequently donated to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (fig. 1). This chair has a raised crest (partially restored) with a half-round appliqué used to form part of the scroll on the back; double-scroll arms; a scalloped front seat rail, medial and rear stretchers with turnings like those on contemporaneous and earlier Boston leather chairs; and turned front legs terminating in carved scroll feet with applied toes. Despite the purported desirability of this combination of elements, only four other Boston easy chairs have all these features: an example formerly owned by Luke Vincent Lockwood (fig. 7), a chair in the collection of the Winterthur Museum (58.538), and the examples shown in figures 12–15. Only about thirteen easy chairs with turned front legs survive, while about nine with squared cabriole legs (most terminating in scroll feet) survive. Between these two groups, certain traits are mixed in unpredictable ways. One might assume that the chairs with squared cabriole legs, formerly considered a rudimentary “Queen Anne” feature, date after those with turned front legs and scroll feet, but the shared traits suggest that the popularity of both leg forms overlapped for a considerable time.

The elements to analyze in these chairs are the form of the crest, the design and arrangement of turned elements on the stretchers, the placement of the medial stretcher, the design of the front legs and front feet, and the shape of the front skirts. In most analyses, the overall cohort of chairs is initially sorted into turned front legs versus square cabriole legs, although this methodology is based on an antiquated bias in favor of turned front legs.

Crest variants include scrolled (figs. 1, 18), high or medium arched (fig. 7), flattened arched, swept (fig. 17), and saddled (fig. 8), although only one chair with the latter type is known. Formerly, the raised, scrolled crest was assumed to be the earliest variant, but of the nine chairs with what appear to be original raised crests, five have turned front legs, while four have squared cabriole legs. One might also think that arched crests are a later feature, but five of the chairs with turned front legs have arched crests, as do five of the chairs with squared cabriole legs. Also, it is worth recalling that the chair illustrated in figure 7, traditionally thought to predate most of the other Boston baroque examples, has an arched crest.

The turned ornament on the medial and rear stretchers displays a similarly wide range of treatments: the Boston vasiform formula, a ball-reel-ball design; and a modified ball-reel-ball design, wherein the balls almost take the form of vases. The easy chair illustrated in figures 9–11 has a medial stretcher with an elongated central knop, or barrel, of the sort seen on stylistically later seating with modeled cabriole legs and pad feet (fig. 26). Among chairs with turned front legs, twelve have vasiform stretchers, while two have some version of the ball-reel-ball decoration. Among chairs with squared cabriole legs, almost all have ball-reel-ball stretchers, with a few odd variants. Ball-reel-ball stretchers are, therefore, a progressive feature.

The location of the medial stretcher on the side stretchers and the turned ornament behind the junction of the medial and side stretchers constitute one of the most striking aspects of Boston easy chair design. In theory, chairs with the abutment set midway on the side stretchers should be somewhat earlier, while those with the abutment set forward should be later. This seems evident, given the fact that Boston easy chairs like the examples shown in figures 12 and 26 have medial stretchers set forward. Of the thirteen chairs with turned front legs, ten have the medial stretcher set in the middle position, but three have the stretcher positioned closer to the front. Of the nine chairs with square cabriole legs, one has the stretcher set in the middle, while eight have the stretcher set forward. Overall, stretchers set forward may be a progressive feature, but not overwhelmingly so. Again, the chair illustrated in figures 9–11 displays a puzzling mix of features, with a frame that seems very progressive but with the medial stretcher set in the middle of the side stretchers.

The side stretchers on six easy chairs have simplified Doric columnar turnings—a common detail on Boston cane chairs and an occasional feature on leather chairs. Of this group, five chairs have turned front legs and one has squared cabriole legs. Why this element occurs on some chairs and not on others is unclear. Presumably, Boston chairmakers maintained stocks of turned components acquired as piecework from specialists. Makers may have used different patterns of side stretchers depending on availability, client preference, and other factors. As long as the side stretchers were of a prescribed length and design to accommodate the structure of the frame and accept the medial stretcher, the form and sequence of turned elements were inconsequential. Oddly, some easy chairs and backstools with smooth cabriole legs and pad feet have turned vases on the side stretchers, when most Boston joined side chairs, armchairs, and easy chairs made after 1740 display abstract columnar turnings.

Traditionally, scholars assigned the earliest dates to easy chairs with turned front legs, a block for the side stretcher joint, and either a turned foot or a carved scroll foot with applied toes. Chairs with squared cabriole legs, which typically have an incised border and scroll feet with applied toes, were considered to date later. Rigid acceptance of that chronology has influenced the marketplace, and for many years, museums and collectors pursued chairs of the “earlier” type more aggressively. Today, easy chairs with cabriole legs are equally prized, which seems fitting, given the fact that the production of both leg forms overlapped from 1725 until circa 1740. Neither of these types of leg was immediately displaced when turned and shaved cabriole legs first came into production, likely during the early to mid-1720s.[5]

The last feature formerly used to date these chairs was the shape of the front seat rail. Scalloped rails, typically featuring S-scrolls separated by a short straight section or a filleted arch, were considered earlier than less elaborate variants, although the former design does not appear to have emerged until about 1710 (fig. 1). The simplest front and side rail design consists of nothing more than integral brackets separated by a wide, flat-headed arch (fig. 7).

Many Boston easy chairs exhibit a mixture of conservative and progressive features and highly variable ornamental schemes within a consistent structural format. Standardized framing patterns appear to have been used throughout the period when easy chairs with turned legs and square sawn legs were fashionable. These patterns may have been shared by a number of joiners working on a subcontract basis for master upholsterers.

Upholstery Evidence on Boston Frames

Only four Boston baroque easy chairs retain or retained original upholstery components into the mid-twentieth century, and of those, two subsequently lost those components, which are now known only from photographs. The chairs that have remnants of original upholstery are in the collections of the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; those for which photographic evidence survives are at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and in a private collection.

The chair illustrated in figures 9–11 retains a significant amount of foundation upholstery. Although the covers, top linen, and stuffing are missing, the surviving components explain much about how such chairs were shaped. These frames were not provided with stay rails, nor did they have tacking struts at the draw-throughs between the wing-arm units and the rear posts and between the wing-arm units and the side seat rails. For these chairs, the heavy sackcloth was folded to create the draw-throughs. The views of the chair illustrated in figures 9–11 demonstrate that this was the case. The rear view reveals that the back had only three side-to-side strips of torn sailcloth as webbing. In the absence of a stay rail, there was little reason to provide vertical webbing. On the wings and crest, the chair has heavy edge rolls. The rolls on the crest are a rare feature not known from other chairs; however, the chair illustrated in figures 9-11 is also idiosyncratic, in that it has no applied half-round on the rear surface of the crest. These rolls are stuffed with hair rather than grass, another unusual treatment. An immigrant upholsterer may have stuffed this frame before he was indoctrinated in the economical practices of Boston shops. The manner of straining the sackcloth between the vertical second posts of the wings and the fore edges of the arm scrolls is the standard practice even today; undoubtedly, scraps of sackcloth were strained on the outside of the frame to complete the cone shape. Not until the 1730s did frame makers routinely provide complete, sculpted cones for upholsterers to work from (figs. 12, 26).[6]

Four photographs of another chair were taken at the time it was acquired in the 1970s by Jewett City, Connecticut, dealer John Walton (figs. 13-16). These images constitute the most thorough record of foundation upholstery on Boston baroque easy chairs. Unfortunately, Walton removed and discarded the components before he offered the frame for sale.[7]

The front view shows the wings, arms, and back with what appears to be most of the stuffing and top linen intact (fig. 13). The wings and arms are tailored as single units; no seam exists at the top of the arm to indicate that the covers were seamed horizontally to make the stuffing and basting procedure easier, as is often the case in modern work. An immense diagonal slash in the top linen where the lower arm begins to pass around the lower arm cone may indicate an extremely rough solution to ticklish basting of the top covers at that point. It seems to be present on both sides. However, the slashes may reflect the well-known proclivity of old-time dealers to cut into old upholstery foundations to examine the frames.[8]

A side view of the easy chair illustrated in figure 13 shows an outer linen liner that is sewn in place (fig. 14). Although one might assume that this liner is an eighteenth-century addition, the brass nail pattern at the lower edge of the seat rail indicates that the liner was part of the original foundation upholstery. The decorative brass nails, which were removed from the front seat rail by a later upholsterer during replacement of the seat deck, were spaced about 1 1/2" apart, and both the author and conservator David de Muzio believe that they were original. One might think that outside liners would be more appropriate in instances where the show cover was silk damask or another fine material, but this easy chair was upholstered with a plain-woven, yellowish wool that may have been a New England product. The outside linen comes up and over the rear portions of the upper arm scroll, which may indicate that this seam was also rendered on the show covers and covered by a continuation of the binding tape coming off the outer edge of the wing.

The rear view of the chair illustrated in figure 13 shows remnants of an outside liner pushed to one side and brass nails going up the sides of the rear posts, details that support the theory that the liner was part of the original foundation upholstery (fig. 15). Loose quilting stitches passing through the coarse base linen or sackcloth of the back suggest that the stuffing, which seems to have been curled horsehair, was quilted in place to prevent it from sagging. The sackcloth extends down to the rear seat rail and obviously was used to create a draw-through during the stuffing and covering process. A three-quarter frontal photograph taken after the chair had been stripped of its top linen and stuffing reveals that the three horizontal webbing strips of the back were retacked on one side (fig. 16). The rear view shows how they were tucked to one side and not visible (fig. 15).

Two other frames have or had remnants of edge rolls and sackcloth on the wings. The example illustrated in figure 1 has edge rolls that were later reinforced with checked linen (fig. 17). The easy chair illustrated in figure 18 also retained sackcloth and edge rolls on the wings, as well as webbing and sackcloth in the back. Both frames confirm that the total width of the wing components plus the edge rolls was intended to be about 1 7/8", the standard size for the stock of which the front and rear legs were made. The partially loosened rolls on the chair illustrated in figure 18 were stuffed with grass.[9]

Most of the surviving Boston baroque easy chairs have crests with filed upper edges, which allowed upholsterers to feather the stuffing and create a crisp line for piping and applied tape. An exception is the chair illustrated in figure 9, which has a square upper edge and no filing. Most of the chairs with scrolled crests have replaced sections at the top, but one example survives full height with its scroll appliqué intact (figs. 19, 20). As the detail shown in figure 20 reveals, the rear of the crest and adjacent posts had rose-headed tacks around the edges. These tacks once held the original back cover in place and were likely covered by applied tape. All of the show covers were tacked in place without liners like those used on the chair illustrated in figures 13–16. Later upholsterers began sewing the outside backs in place, perhaps to conserve on tacks and the expensive binding tape.[10]

Even frames that were stripped in the past sometimes retain fragments of original covers under tacks (figs. 21-23). Two chairs had red covers, two had blue, two had green, and one had yellow. All these covers were wools, although most of the fragments are too small to determine if they were plain or watered and calendered moreens and harrateens.

English Baroque Easy Chairs

With the publication of Lucy Wood’s The Upholstered Furniture in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in 2008, the study of English historical upholstery reached new levels of precision and detail, although still little is known about mid-market upholstered furniture in London. The problem resides in the fact that most of the surviving documented English upholstery consists of extravagant treatments for royal or aristocratic commissions. The implications of such work for colonial upholstery are even less clear. What can be derived from the study of high-end English work are questions surrounding bulk, tailoring, and the amount and positioning of trims.

Not all chair wings of the 1700–1725 era were stuffed with edge rolls and provided with panels. Some wings were stuffed leaner and were carried with a soft, slumping shape over the outer wing edge. This styling occurs on a number of important seating forms, notably the Chastleton chair at the Victoria & Albert Museum, an unusual chair with wings and low arms at Boughton, a settee at Drumlanrig Castle, a settee from Chevening, and an easy chair from Clandon. No Boston baroque easy chair examined for this study has original chamfering on the wings, but several have crests with chamfers on the lead edge. The wings of some chairs were chamfered later, possibly in the neoclassical period, when wings without panels became almost universal. All of the available evidence suggests that Boston baroque easy chairs had wings with edge rolls and panels.[11]

It is also apparent that some variety of arm treatments existed in the aristocratic level of seating frames. While many chairs have the same C-scroll panels seen on most Boston frames, some had rudimentary arms, or arms that cantilevered over the side seat rails without a supporting stump (rather in the manner of surviving eastern Massachusetts bed rests), and others had only a single vertical scroll (fig. 26) or a single horizontal scroll (as in many neoclassical easy chairs). At the same time, surviving middle-class English frames of the 1710–1730 era look very much like the Boston baroque frames. While variety was a positive virtue when designing for discriminating high-end clients, it may have been a detriment in middle-class frames that were produced in quantity.[12]

Many aristocratic English seating frames were not provided with cord under tapes on the arms, wings, and crests. The probable explanation is that the covers and trims of such things were extraordinary and expensive, and the use of cord under trims was associated with a middle-class impulse to protect the covers from wear, an attitude inimical to aristocratic ease. Also, most aristocratic furniture rarely was sat on and was protected by loose covers much of the time; hence, there was no reason for the concern for wear implicit in cords under trims. However, these same aristocratic seats almost all have bound edges on the cushions. As seen on the easy chair illustrated in figure 26, the bag for down was sewn with the seams facing outward, and the covers were cast directly on the bag, followed by the binding tape. While it is now considered normative for the down cushion to have a deep boxing and to be level with the lower scrolls on the arms, some of the English cushions are noticeably lower in height (fig. 24). In some instances, wear to the boxing or even burst seams may have prompted repairs and a reduction in height of the cushions over the years.[13]

How the flat tape running around the base of upholstered seating was treated is unclear. In some English examples, it simply follows the scalloped contour, with pleating or mitering where needed to conform to the outline. In other cases, the tape is brought up into pleated whorls or rosettes on the skirts and arm panels, an extravagant gesture that overtly calls to mind the scrolls on Ionic capitals as well as nautilus shells (fig. 25). The brass nailing on one of the Boston frames may have been associated with this type of elaboration, whereas that ornamenting the front seat rail of the chair illustrated in figure 1 is geometric in design. Several English seats have spaced brass nailing on straight runs of tape, as well. Closer inspection of Boston frames may reveal that brass nailing was more prevalent than we now think.[14]

Continuities in Upholstery on Later Boston Easy Chairs

Upholsterer Andrew Passeri and the author conserved and published the easy chair illustrated in figures 26–35 in 1983 and pointed out its strong affinity to an example inscribed “Gardner Junr / Newport / May / 1758 / W” (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Both chairs appear to have been upholstered in the same manner, with vestigial, false raised crests created by cord and binding tape (fig. 28). These easy chair frames, which may have been made in Boston, shipped to Rhode Island, and covered soon after arrival, shed light on the upholstery of earlier examples.[15]

Unlike some Boston easy chairs with rounded cabriole legs, the chair illustrated in figure 26 is stuffed mostly with grass, which contributed to the lean contours of all the upholstered panels. No undercovers or liners are beneath the covers of the outside arms and outside back. This lack of concern for the integrity of the covers is consistent with upholstery evidence on the chair illustrated in figures 19 and 20, where original nail sites indicate that the covers were tacked directly on the frame without an intervening liner. No cotton wadding or tow (crushed flax stems) was placed between the top linen and the covers of the interior of the chair. In modern practice, cotton wadding is almost always used under the covers to prevent the ends of the horsehair from poking through. However, some portions of the grass stuffing of the chair illustrated in figure 26 may have received a tow skimmer on top of the grass stuffing and under the top linen, to smooth the contours of the grass. One outside arm of the chair has pieced-out covers, and no attempt was made to match the pattern. A similar lack of interest in pattern matching, undoubtedly influenced by the cost of the textiles, is seen even at the highest levels of European patronage at this period.[16]

Binding tape (fig. 29) covers most of the seams on the covers of the easy chair illustrated in figure 26. The long seams of the wing and arm panels and the crest were provided with applied cords before the binding tape was attached. Again, using cords under binding tapes raised the binding so that most of the wear was on it, rather than on the covers. Flat-sewn tape around the base is decorated with widely spaced polished steel nails about 1/4" in diameter (fig. 30). The chair inscribed “Garnder Junr” has similar steel nails, and two Boston rococo easy chairs have evidence of decorative brass nailing. At this juncture, such use of brass nailing has been documented only in two Boston baroque easy chairs (figs. 1, 13). Because the side seams of the outside back of the chair illustrated in figure 26 were sewn, they did not receive binding tape; however, tacking evidence on the examples illustrated in figures 9 and 19 indicate that the vertical seams of the outside backs must have received binding tape (see fig. 1).

The edge rolls on the wings, arms, and front seat rail of the chair illustrated in figure 26 are stuffed with grass. Those on the wings and the seat rail are slightly less than 1" in diameter, and the upholsterer adhered to the rule of thumb that the combined thickness of the wing rails and the edge roll would be about 1 7/8". Far more significant is how the edge rolls on the arm panels taper as they pass around the vertical arm cones (fig. 31). These diminishing edge rolls were the accepted practice throughout the eighteenth century. Since there was no need for stuffing in areas away from the sitter, it diminished until there was none on the outsides of the frame. This differs considerably from modern upholstery, where many artisans persist in the Victorian practice of carrying edge rolls all around the arm scrolls. The edge roll on the front seat rail has no counter-stuffing behind it (fig. 32). The flat deck begins immediately behind the edge roll, although the deck has a grass skimmer under the covers to distribute the stress from the sitter’s weight more evenly. Otherwise, the sitter may have felt the seat webbing, even through the thick down cushion.

The cushion has a boxing of about 4 1/2" (fig. 33) and is stuffed with a mixture of down and quills. If the mixture had had too much down, the sitter would have sunk through the cushion. The bag or casing for the stuffing is made of bed ticking. Other cushions may have had leather or glazed linen bags. The bag was sewn with the seams out. The cushion covers were not made into a case into which the down bag was inserted; rather, the covers were cast directly onto the down bag in separate pieces. All the resultant raised seams were then bound with binding tape sewn through and through. This practice went back to the seventeenth century and persisted until the neoclassical period. The raised seams correspond nicely to the raised binding tape over cord on the wings and crest.

Two final details of note on the chair illustrated in figure 26 are the rounded outer corners of the rear posts (fig. 34) and the stained feet of the maple rear posts (fig. 35). Not all Boston easy chairs of this standardized type have rounded rear posts, but a great many do. This structural detail may have facilitated stitching the long seams running up the posts, as opposed to tacking them and covering them with tape. Almost all Boston easy chairs with rounded cabriole legs and turned feet have walnut front legs and continuous maple rear posts, which required makers to color the rear foot sections with a penetrating stain so that they matched the rest of the undercarriage. The evidence on the chair illustrated in figure 26 begs the question of how the walnut was finished. Most likely the front legs and stretchers were coated with a paler stain to unify all the visible wooden components. Additional evidence for stains used on maple can be found on stair balusters associated with a mahogany bombé pulpit made by Abraham Knowlton (1699–1751) of the First Church in Ipswich, Massachusetts, circa 1749 to 1751. The balusters, which may have been subcontracted to another local artisan, were coated with a red stain followed by a brown-tinted resin.[17]

The implications of the upholstery of the easy chair illustrated in figure 26 to Boston baroque examples are clear. Most of the earlier examples would have been covered with wool and trimmed with silk-and-wool tapes on the seams, their edge rolls would have diminished as they passed toward the outsides of the chair, and their cushions would have been of approximately the same height, if not somewhat higher.

The tailoring and trimming of certain details will always remain speculative. Raised crests present a number of trimming challenges. Because the face tacking of the crest runs under the applied roll on the back, those tacks should be covered by tape. In their treatments, conservators Leroy Graves and Nancy Britton have provided additional tape along the seams going up to the roll on the crest in front and additional tape detailing. The exact treatments of the flat tapes running around the bases are also a subject of debate. Some brass nailing may have been associated with tape zigzags or pleated rosettes, as seen in English chairs (fig. 25). Textile conservators who have studied the minutely shirred and flat-sewn tape on bed valances might cavil about the relatively crude pleating of tapes to conform to the scrolled skirts of easy chairs, but a great divide always existed between flat-sewing executed on tables with straight needles and sewing on upholstered frames executed with curved needles.

Conclusion

Some might find the theory that the 1725–1740 period was one of stylistic turmoil in Boston easy chair design to be forced, but American furniture historians have become so accustomed to citing the well-known 1728 and 1729 entries from Boston upholstery accounts, where the first references to compass seats and cabriole legs are found, that they assume an abrupt stylistic transition from squared to rounded cabriole leg forms took place. This theory began to be challenged in the 1990s by Luke Beckerdite, Joan Barzilay Freund, Leigh Keno, and Alan Miller. These scholars made note of some of the stylistically anomalous easy chairs and related seating discussed here, but their interpretation centered on the introduction of new styles and experimentation with designs rather than the process of standardization and the period when that occurred.[18]

The easy chair illustrated in figure 36 suggests that stylistic transitions in mainstream Boston seating were more gradual than previously assumed. This chair has many features not typical of the more standardized easy chair form with modeled cabriole legs and pad feet that came into production in the 1730s. This chair has the expected single, vertical scroll arms that are continuous with the wings, but it also has an odd crest with a central raised arch, a straight front seat rail, and small cabriole legs with a more exaggerated curve than is seen in later models. A side chair probably made by the same joiner has applied turned bosses on the knees; the bosses are missing on the easy chair. The most striking feature of the easy chair is the bilaterally symmetrical vase stretcher. Although complete vases on side stretchers appear on many forms of “transitional” Boston seating, they are quite rare on medial stretchers. The vases on the easy chair recall the “modified” ball-reel-ball turnings on the medial stretchers of earlier Boston baroque examples. In this particular instance, the turner pushed the modification of a ball turning with a vase-like neck to its logical conclusion, a fully articulated vase. A stripped view of the chair (fig. 37) reveals simplified framing for the vertical arm cones, which are rendered as solid, sculpted cones, rather than as vertical struts to which portions of a cone are applied. Further, the back frame lacks a stay rail, certainly the least progressive trait on what appears to be a fairly progressive seating design.[19]

The standard Boston easy chair with modeled cabriole legs and pad feet—one of the most abundant upholstered forms to survive from the mid-eighteenth century—did not simply spring into being in 1728. During the late 1720s and 1730s, chairmakers experimented with details observed on imported British seating, adapting some features and discarding others. Some of the extremely rare chairs noted in Freund and Keno’s 1998 article in American Furniture may, in fact, have been experimental models concocted by the upholstery shop masters and their joiner subcontractors, perhaps in response to the latest imported frames. These prototypes call into question the caricature of Boston upholstered seating as having rough, mass-produced frames.

Another factor to bear in mind regarding this Boston seating, much of which was aggressively marketed in other colonial ports, was the rise in the 1730s of competing chairmaking and upholstery traditions in Philadelphia. James Logan (1674–1751), a wealthy merchant and politician, may have acquired one of the earliest surviving Philadelphia easy chairs about 1730 (fig. 38). The frame is intricately joined and was probably made by an immigrant Irish craftsman. It has heavy, flat-oriented front and side seat rails in a compass-shaped plan. The front corners are lapped and accept the round tenons of the legs, which are reinforced with wooden pins. The cabriole rear legs are attached to the frame by a complex double-tongued V-splice (figs. 39-41). Most noteworthy are the three vertical posts that form each wing. The outer stiles of the back frame are vertical, but the second and third posts moving forward are cocked at progressively greater angles, to create the inviting, splayed form for which Philadelphia easy chairs are famous. The frame has fully articulated tacking struts, as do all later Philadelphia easy chair frames.[20]

The stuffing of the Logan chair is equally significant. All Philadelphia easy chairs of the colonial period have heavy, curled hair stuffing that is thin at the fore edges and grows progressively thicker as it moves toward the draw-throughs. This makes the chair more comfortable and emphasizes the splay of the structural members. This quality of joinery and stuffing was not seen in New England frames until the neoclassical period. Furthermore, New England frames retained the continuous rear-post-leg structure until the 1780s, so those easy chairs could not have the pronounced heels and layback of Philadelphia versions. All told, the Logan chair is an extraordinarily important document. It demonstrates that the complex framing and heavy, curled horsehair stuffing of the many Philadelphia rococo frames that survive with original foundations were established by the early 1730s and were not a development of the 1750s and 1760s. The Logan chair also proves that by the 1730s, the squarish, cheaply upholstered chairs produced in Boston until the 1780s were outdated by English standards. Little is known about contemporaneous New York frames, and the emergence of a documented example with original upholstery foundations would be extremely useful to colonial upholstery history.[21]

Comparing Boston and Philadelphia easy chairs and their upholstery suggests that many models of frames emanated from shops in London and other British urban centers and influenced American production in highly variable ways. How and from whom imported prototypes were ordered had a strong impact on what was ultimately adapted for colonial models, and the process did not necessarily involve a neat succession of transitional steps. After all, the master upholsterers, shop joiners, and their clients did not perceive themselves as living through a transition, despite promotional statements proclaiming new fashions, nor did tastes in furniture design change as quickly as they did in such media as silver and ceramics. Furniture historians today need to exercise caution when interpreting certain rare models of seating, because rarity can suggest a short production span in the period, as well as an experimental dead-end.

Despite her widespread influence and an abundant documentary and photographic record, no major monograph on Katherine Prentis Murphy has been written. A useful summary of her activity is in Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), pp. 248–51. Alice Winchester, the editor of Antiques, admired Murphy and published many notices about her, beginning with Alice Winchester, “Living with Antiques—the Connecticut Home of Mrs. Katherine Prentis Murphy,” Antiques 58, no. 4 (October 1950): 430, 432–36. Murphy’s house and cottage at Westbrook, Connecticut, dubbed by her Candlelight Farm, were her testing ground for decorative and entertaining styles. Like many of her generation, Murphy seems to have emulated Henry David Sleeper in employing entertaining as a means of enhancing her reputation. Other brief articles with references to Murphy include Alice Winchester, “Three American Rooms,” Antiques 58, no. 4 (October 1950): 281–84; Alice Winchester, “Period Rooms for New Hampshire,” Antiques 74, no. 6 (December 1958): 532–33; Alice Winchester, “The Prentis House at the Shelburne Museum,” Antiques 71, no. 5 (May 1957): 440–42; Lauren B. Hewes and Celia Y. Oliver, To Collect in Earnest—The Life and Work of Electra Havemeyer Webb (Shelburne, Vt.: Shelburne Museum, 1997), pp. 36, 48, pls. 10, 11; Richard Lawrence Greene and Kenneth Edward Wheeling, A Pictorial History of the Shelburne Museum (Shelburne, Vt.: Shelburne Museum, 1972), pp. 48, 49, 56–59; Ralph Nading Hall and Lilian Baker Carlisle, The Shelburne Museum (Shelburne, Vt.: Shelburne Museum, 1960), pp. 83–85; David B. Warren, Bayou Bend—American Furniture, Paintings and Silver from the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1975), pp. 2–5; David B. Warren, Bayou Bend—The Interiors and the Gardens (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1988), pp. 9, 12, 14–17; David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Princeton University Press, 1998), pp. xviii–xix; and Philip N. Guyol, “The Prentis Collection,” Historical New Hampshire 14 (December 1958): 9–16, fig. 7. In 1982 and 1983 the period rooms Murphy and her brother donated to the New Hampshire Historical Society and the New-York Historical Society were, with the exception of a few objects, dismantled and deaccessioned. The New Hampshire Historical Society objects were sold at Robert W. Skinner, Inc., The Katherine Prentis Murphy Collection, Bolton, Massachusetts, September 24, 1983. The New-York Historical Society collection was sold to Bernard and S. Dean Levy, New York. Other period rooms by Murphy survive with a few modifications at Bayou Bend, the Shelburne Museum, and the Buttolph-Williams House, Wethersfield, Connecticut, Connecticut Landmarks.

Robert F. Trent, Robert Walker, and Andrew Passeri, “The Franklin Easy Chair and Other Goodies,” Maine Antique Digest 7, no. 11 (December 1979): 26B–29B. One of the chairs upholstered by the author sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art, and Decorative Arts, New York, October 8, 1998, lot 38. For an earlier image of the same chair, see Harry Arons advertisement, Antiques 83, no. 4 (April 1963): 371. The most recent image is in Robert F. Trent and David F. Wood, “The Earliest American Easy Chairs,” Catalogue of Antiques & Fine Art 4 (Autumn 2003): 161, fig. 1. The writer upholstered the Bacon chair (figs. 3, 4) in 2000. The chair is illustrated in Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730—an Interpretive Catalogue (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), p. 358, fig. 186; and in Joan Barzilay Freund and Leigh Keno, “The Making and Marketing of Boston Seating Furniture in the Late Baroque Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), p. 8, fig. 11. The Bacon chair is illustrated with the author’s upholstery in Trent and Wood, “The Earliest American Easy Chairs,” p. 162, fig. 3.

Thirteen mature Boston baroque easy chairs with turned front legs are known, including the first example cited as having been upholstered by the author, above. Three examples were published in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 363–66. The Blagojevich chair (fig. 1) has been illustrated repeatedly: Helen Comstock, “West St. Marys Manor, the Maryland Home of Lieutenant Colonel and Mrs. Miodrag Blagojevich,” Antiques 83, no. 2 (February 1963): 186–89; Karin M. Jones, “The Blagojevich Collection of William and Mary Furniture at Colonial Williamsburg,” Antiques 123, no. 1 (January 1983): 196–201; and David Donnelly, “Highlights of American Period Furniture, Part II: The Baroque Period,” American Woodworker, October 1990, p. 59. For the latest scholarship on the Blagojevich chair, see Leroy Graves, The Upholstery Craft in America and England, 1750–1820: Reading the Evidence (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, forthcoming). The chair illustrated in fig. 13 was featured in two advertisements by John S. Walton: Antiques 105, no. 4 (April 1974): 652; and Antiques 120, no. 2 (August 1981): 206. A chair collected by Mrs. J. Insley Blair and donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art is illustrated in Frances Gruber Safford, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art—I. Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), pp. 105–7. A chair in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1976.727), was published in Trent, Walker, and Passeri, “The Franklin Easy Chair,” figs. 1–3. A chair formerly belonging to George A. Goss sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver & Chinese Export, New York, January 19–23, 2012, lot 103. The chair illustrated in fig. 8 has not been published. A chair in the Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, was published in John Kenneth Byard advertisement, Antiques 57, no. 6 (June 1950): 401; Israel Sack advertisement, Antiques 73, no. 6 (June 1958): 500; Warren, Bayou Bend, pp. 5, 11; and Warren, Brown, Coleman, and Neff, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection, pp. 9–10. Other chairs are illustrated in Robert W. Skinner, Inc., American Furniture & Decorative Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, January 6, 2004, lot 265; and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, Fine Americana, New York, April 27–29, 1978, lot 921.

Nine Boston William and Mary easy chairs with square cabriole legs, most of which have Spanish feet, are known. The example illustrated in fig. 21 sold at Blackwood/March Auctioneers, Essex, Massachusetts, October 15, 2008, lot 29. A chair in the Historic Deerfield collection is illustrated in Dean A. Fales Jr., The Furniture of Historic Deerfield (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1976), p. 40, fig. 69. The New Hampshire Historical Society chair is illustrated in Wendy A. Cooper, In Praise of America: American Decorative Arts, 1650–1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf for the Girl Scouts of the United States of America, 1980), p. 64, no. 81. A chair in the Currier Museum of Art is illustrated in Andrew Passeri and Robert F. Trent, “More on Easy Chairs,” Maine Antique Digest 15, no. 12 (December 1987): 3B, figs. 6A, 6B. The John Kenneth Byard chair is illustrated in the Archives of American Art, John Kenneth Byard Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Library, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden, Winterthur, Delaware (66.1774); and Christie’s, American Furniture and Decorative Arts, New York, January 23, 2009, lot 157. The Winterthur Museum chairs, acc. nos. 58.576, 58.1504, and 58.537, are illustrated in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 367–70. The chair illustrated in fig. 19 is illustrated in Safford, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum, pp. 108–10.

For two chairs considered by the author to be out of period or modern rebuildings, see H. and R. Sandor advertisement, Antiques 97, no. 3 (March 1970): 305; and American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Highland House Publishers, 1981), p. 65, no. 207. The latter chair reappeared on the market at Sotheby’s, Selections from Israel Sack, Inc., New York, January 20, 2002, lot 1360.

Adam Bowett, English Furniture, 1660–1714, from Charles II to Queen Anne (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002), pp. 244–59; Adam Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, 1715–1740 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2009), pp. 144–96; and Lucy Wood, The Upholstered Furniture in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with National Museums Liverpool, 2008), 1: 44–80.

For more on Boston leather chairs, see Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown Jr., “Boston and New York Leather Chairs: A Reappraisal,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 175–94.

Documentary evidence for the introduction of shaved cabriole legs and compass or horseshoe seat plans in the late 1720s was initially presented in Brock Jobe, “The Boston Furniture Industry, 1720–1740,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Muir Whitehill, Jobe, and Jonathan Fairbanks (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1974), pp. 3–48. More detailed treatments of early upholsterers’ accounts appeared in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 281–88; and Freund and Keno, “The Making and Marketing of Boston Seating Furniture in the Late Baroque Style,” pp. 1–40.

Andrew Passeri and the author upholstered the chair illustrated in figs. 9–11 in the 1980s (Passeri and Trent, “More on Easy Chairs,” p. 3B, figs. 6A–6E).

The author was unable to examine all the frames included in this study, so it is possible that original upholstery survives under the show cloth of other examples.

David de Muzio, furniture conservator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, has questioned the age of the upholstery visible in the photographs of the chair illustrated in figs. 13–16, but the author is convinced that all the components other than the seat deck are original.

The easy chair illustrated in fig. 18 sold at auction in 2009 (Christie’s, American Furniture and Decorative Arts, New York, January 23, 2009, lot 157).

The conservation of the easy chair illustrated in figs. 19 and 20 is discussed in Nancy Britton with Mark Anderson, “The Evolution of American Upholstery Techniques: 1650 to 1900,” in The Forgotten History—Upholstery Conservation, edited by Karin Lolm (Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University, 2011), pp. 48–49.

For the Chastleton chair, see Peter Thornton, “Upholstered Evidence: Or How the Members of the Furniture History Society Came to Assist in Saving the Remains of a Queen Anne Wing Chair,” Furniture History 10 (1974): 17–19, pls. 6A, B; and Trent, Walker, and Passeri, “The Franklin Easy Chair,” p. 28B, figs. 6A, B. The Boughton easy chair is illustrated in Francis Lenygon, Furniture in England from 1660 to 1760 (London: B. T. Batsford, 1924), p. 31, fig. 23. The Drumlanrig Castle settee and the Chevening settee are illustrated in Wood, The Upholstered Furniture in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, pp. 80, 81, figs. 89, 90. The Clandon easy chair is illustrated in John Fowler and John Cornforth, English Decoration in the 18th Century (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1974), p. 153, fig. 142.

One of a pair of unusual easy chairs with wings and rudimentary low arms is illustrated in Lenygon, Furniture in England from 1660 to 1760, p. 31, fig. 23. A settee with cantilevered arms oversailing T-cushions is illustrated in ibid., p. 79, fig. 128. A settee with vertical scrolls only is illustrated in Fowler and Cornforth, English Decoration in the 18th Century, p. 134, fig. 116. A settee with horizontal scrolls is illustrated in Peter Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration in England, France & Holland (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 214, fig. 204.

Among the many examples of published seating with binding tape, especially outward seams bound with tape on the seat cushion, is an easy chair from Clandon illustrated in Fowler and Cornforth, English Decoration in the 18th Century, p. 153, fig. 142. Also of great interest is a complete set of loose easy chair covers at the Victoria & Albert Museum, with all seams sewn outward and bound with tape. Similar sets of embroidered, fixed easy chair covers, now removed from their original frames, are at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Winterthur Museum.

Nancy Britton identified brass nailing on a Boston baroque easy chair in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The nailing on the chair illustrated in figs. 13–16 is discussed in Rian Deurenberg, “Technical Examination of a Boston Easy Chair 1999-62-1” (2005), with additions by David de Muzio (2009), Furniture Conservation Department, Philadelphia Museum of Art. For steel nails on Boston late baroque easy chairs, see Andrew Passeri and Robert F. Trent, “Two New England Queen Anne Easy Chairs with Original Upholstery,” Maine Antique Digest 11, no. 4 (April 1983): 26a–28a. For two Boston rococo easy chairs with brass nailing, see Edward S. Cooke Jr., “The Nathan Low Easy Chair: High Quality Upholstery in Pre-Revolutionary Boston,” Maine Antique Digest 15, no. 11 (November 1987): 1C–3C; and William Voss Elder III and Jayne E. Stokes, American Furniture, 1680–1880, from the Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1987), pp. 52–54, no. 34.

Passeri and Trent, “Two New England Queen Anne Easy Chairs,” pp. 27A–28A. Opinion is divided as to whether the easy chair illustrated in fig. 26 and the related needlework easy chair at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc. no. 50.228.3) were made in Boston or in Newport.

For a French aristocratic chair with similar rough piecing-out of covers, see Xavier Bonnet, “Chanteloup: Un moment de grâce autour du duc de Choiseul—tête-à-tête de la galerie de Chanteloups,” unpublished MS, 2010.

For the First Church pulpit and balusters, see Peter Benes and Phillip D. Zimmerman, New England Meeting House and Church: 1630–1850 (Boston: Boston University and Currier Gallery of Art for the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 1979), pp. 42, 136–37, nos. 74 and 78. On p. 136, the balusters are incorrectly described as “stripped of paint.” See also Robert Mussey and Anne Rogers Haley, “John Cogswell and Boston Bombé Furniture: Thirty-Five Years of Revolution in Politics and Design,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), p. 99n2; and Susan S. Nelson, “Capt. Abraham Knowlton, Joiner, and the Seminal Woodworkers of Ipswich, Massachusetts,” in Rural New England Furniture: People, Place, and Production, edited by Peter Benes (Boston: Boston University for the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 2000), pp. 46–53, figs. 5A, B. Erik Gronning and the author examined the six surviving balusters in 2010.

Freund and Keno, “The Making and Marketing of Boston Seating.”

For the side chair, see ibid., p. 12, fig. 17.

The author thanks furniture scholar Alan Miller for his observations on the geometry of the Logan chair’s frame.

Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Silver, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, New York, June 21, 1995, pp. 116–19, lot 217; and Mark Anderson and Robert F. Trent, “A Catalogue of American Easy Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 212–34.