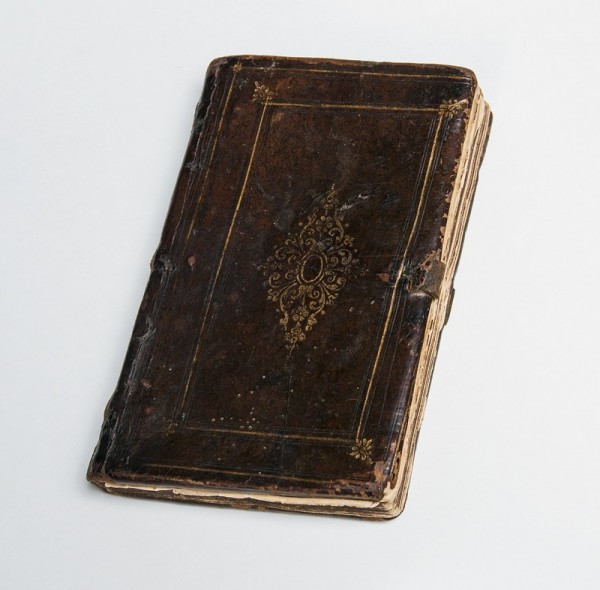

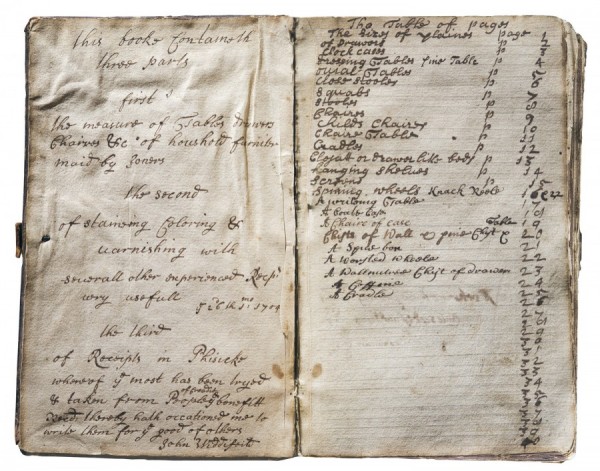

John Widdifield notebook, northern England and Philadelphia, ca. 1704–1720 with later inscriptions. Leather, paper, and ink. 6 1/2" x 4 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

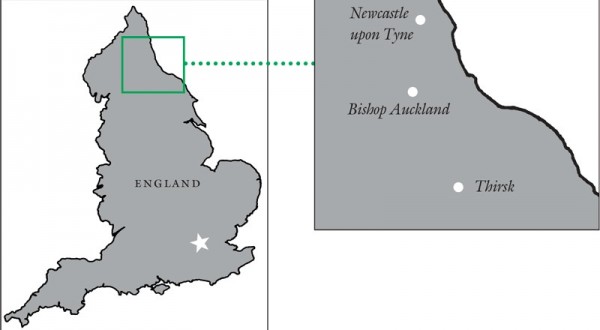

Map of England showing towns associated with Widdifield.

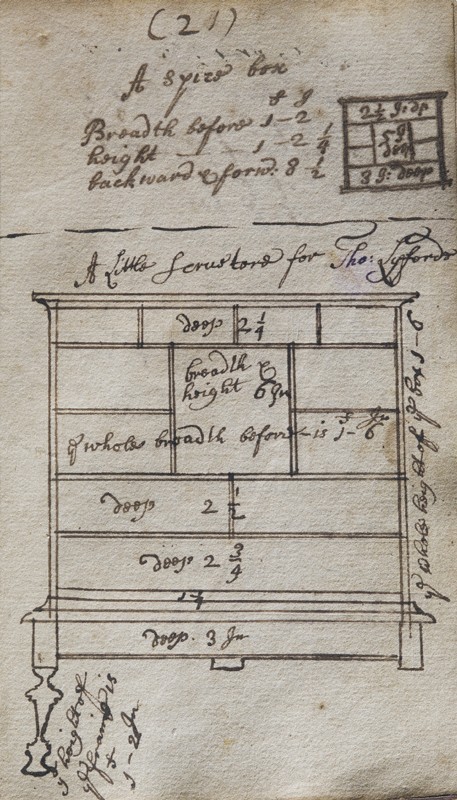

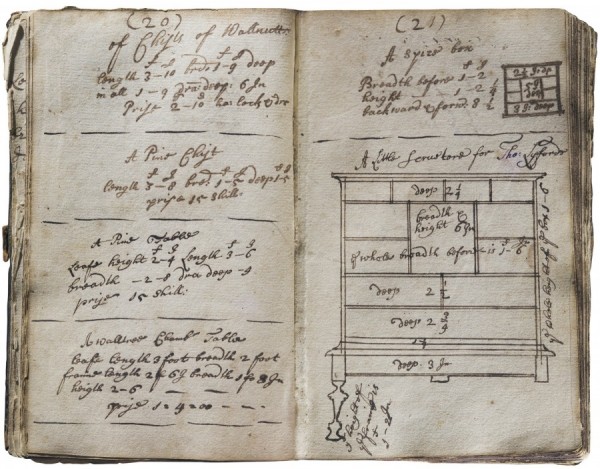

Designs and measurements for a spice box and scrutoire on p. 21 in John Widdifield’s notebook. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Spice box-on-stand, case and frame possibly from the shop of John Widdifield, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1715. Mahogany with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 25 1/2", W. 18 5/8", D. 9". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The spice box listed in Widdifield’s inventory was made of mahogany.

Spice box-on-stand, case and frame possibly from the shop of John Widdifield, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1715. Mahogany with white cedar, oak, and yellow pine. H. 26", W. 17", D. 9". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

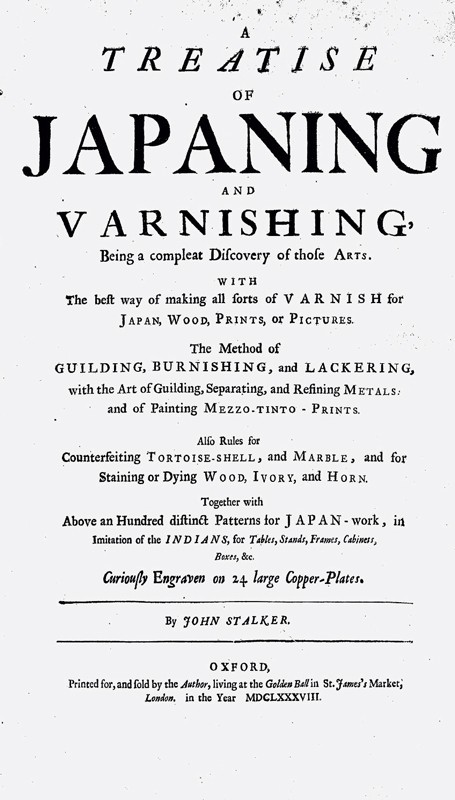

Title page of John Stalker and George Parker’s Treatise on Japaning and Varnishing, Oxford, England, 1688.

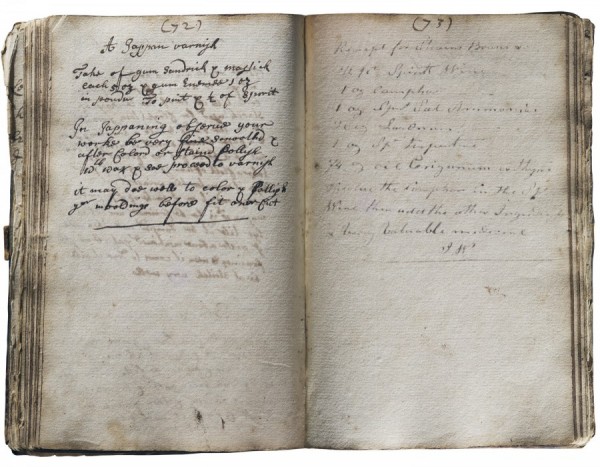

Left: Inside front cover. Right: Book block page 1.

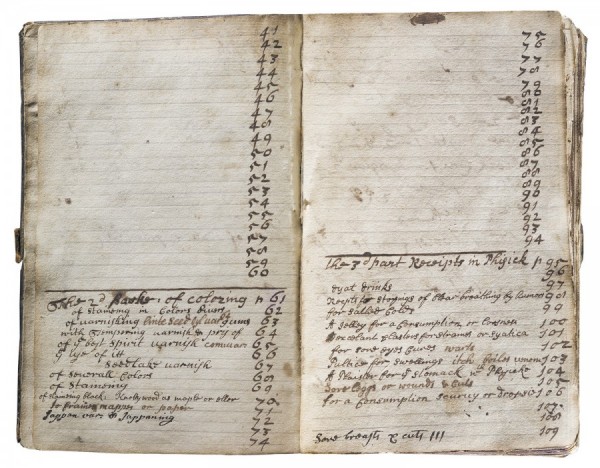

Left: Book block page 2. Right: Book block page 3.

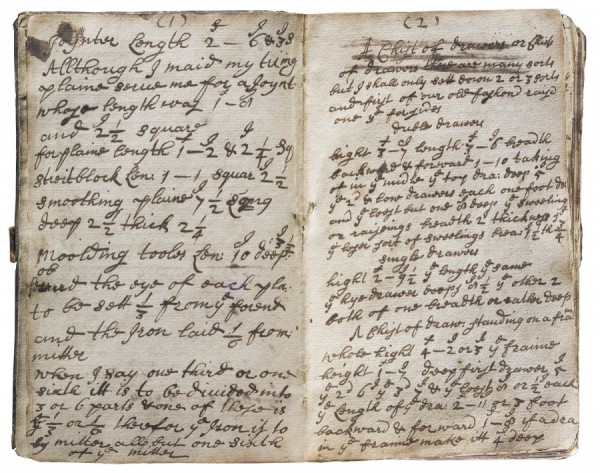

Left: Book block page 4, numbered (1). Right: Book block page 5, numbered (2).

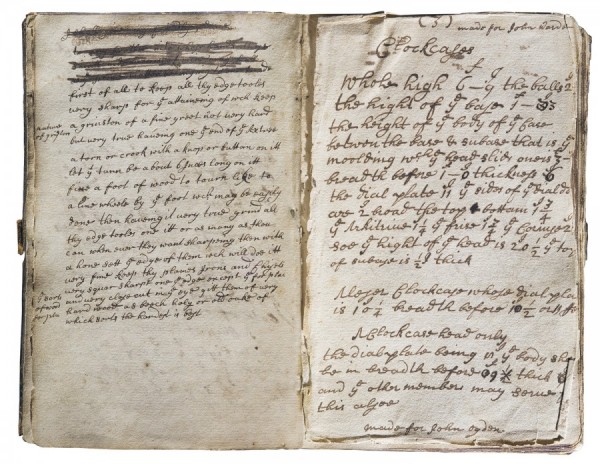

Left: Book block, page 6. Right: Book block page 7, numbered (3).

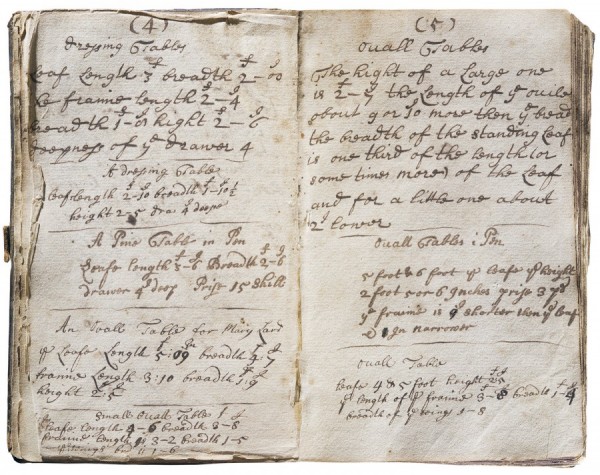

Left: Book block, page 8, numbered (4). Right: Book block page 9, numbered (5).

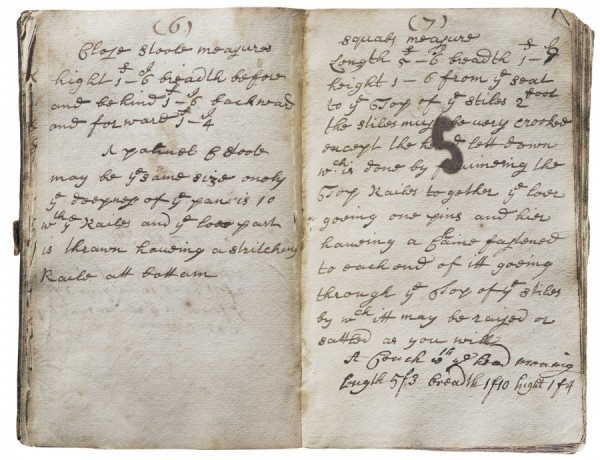

Left: Book block, page 10, numbered (6). Right: Book block page 11, numbered (7).

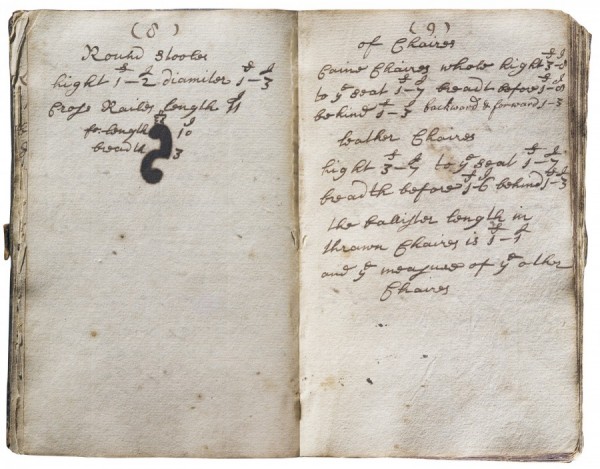

Left: Book block, page 12, numbered (8). Right: Book block page 13, numbered (9).

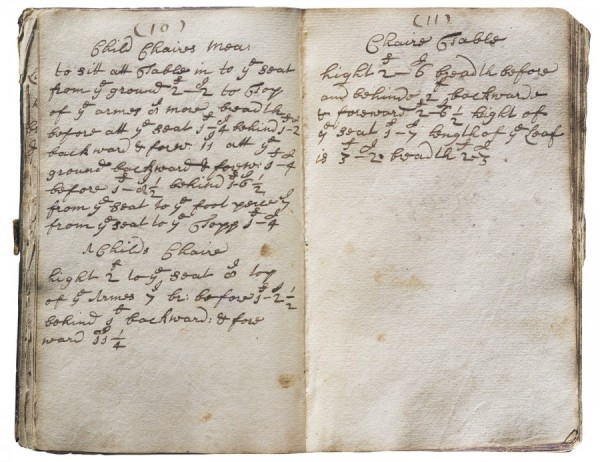

Left: Book block, page 14, numbered (10). Right: Book block page 15, numbered (11).

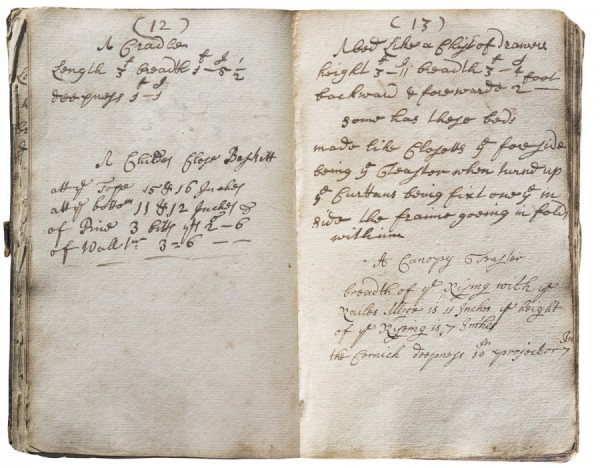

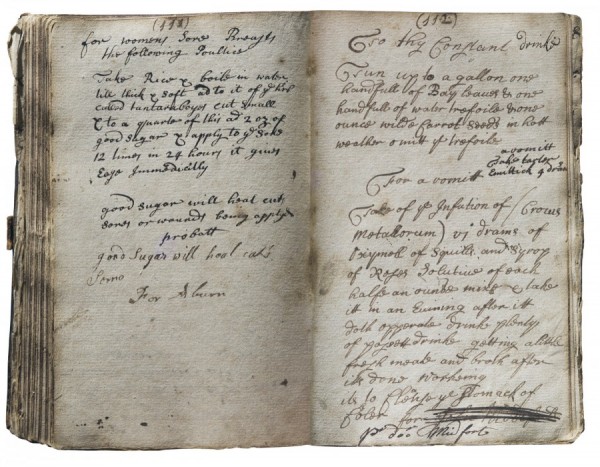

Left: Book block, page 16, numbered (12). Right: Book block page 17, numbered (13).

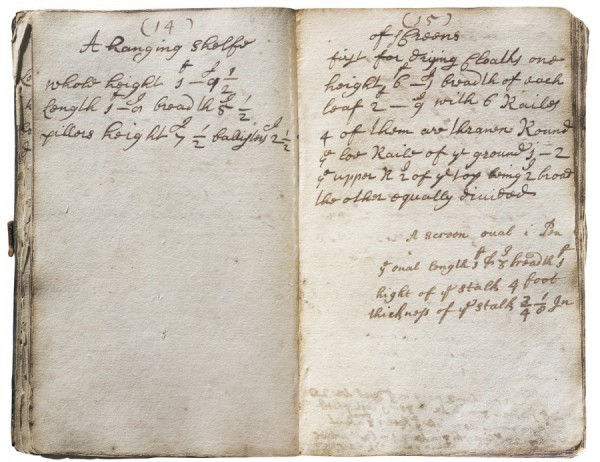

Left: Book block, page 18, numbered (14). Right: Book block page 19, numbered (15).

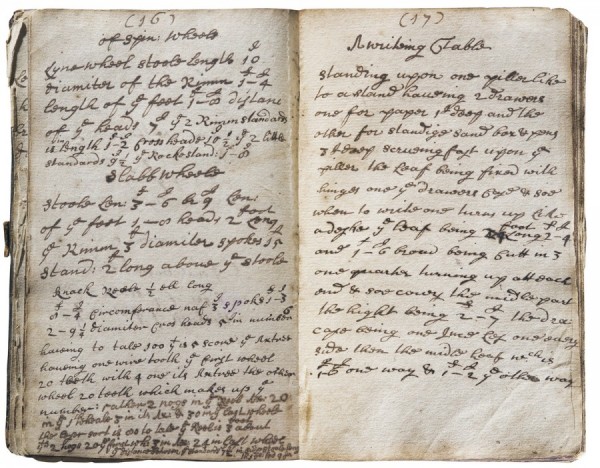

Left: Book block, page 20, numbered (16). Right: Book block page 21, numbered (17).

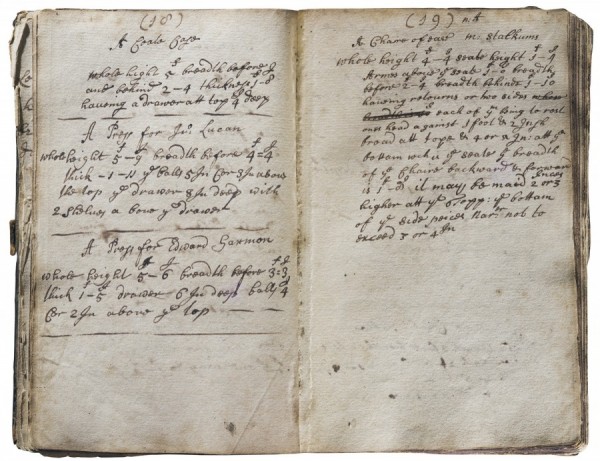

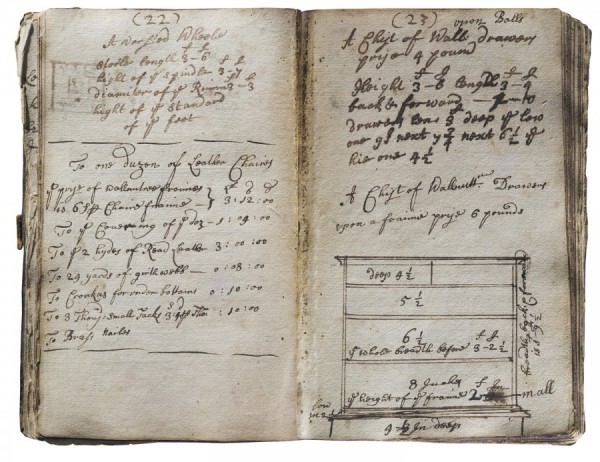

Left: Book block, page 22, numbered (18). Right: Book block page 23, numbered (19).

Left: Book block, page 24, numbered (20). Right: Book block page 25, numbered (21).

Left: Book block, page 26, numbered (22). Right: Book block page 27, numbered (23).

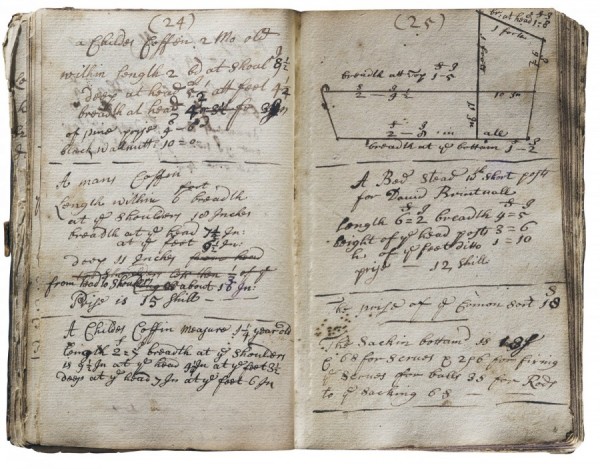

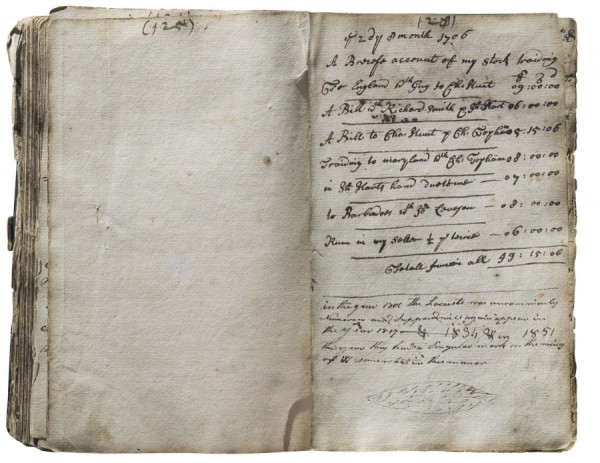

Left: Book block, page 28, numbered (24). Right: Book block page 29, numbered (25).

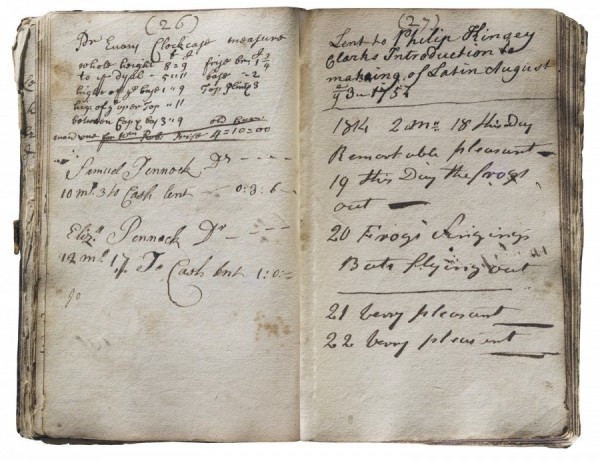

Left: Book block, page 30, numbered (26). Right: Book block page 31, numbered (27).

Left: Book block, page 34, numbered (30). Right: Book block page 35, numbered (31).

One leaf torn out presumably (33) and (34). Following this spread are twenty-four pages each with the numbers in parenthises at the center top of the page beginning at (36) ending at (59). The numbering is consecutive.

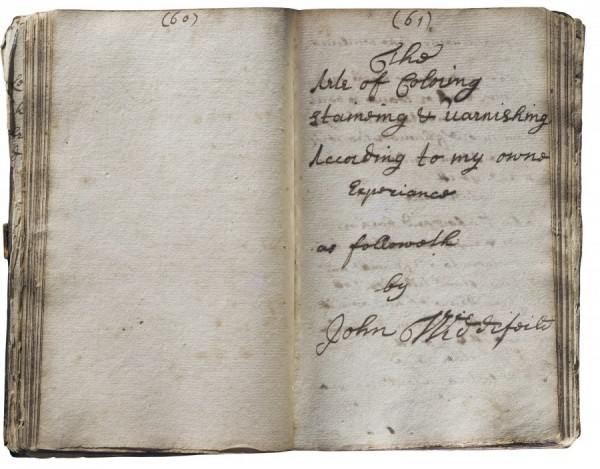

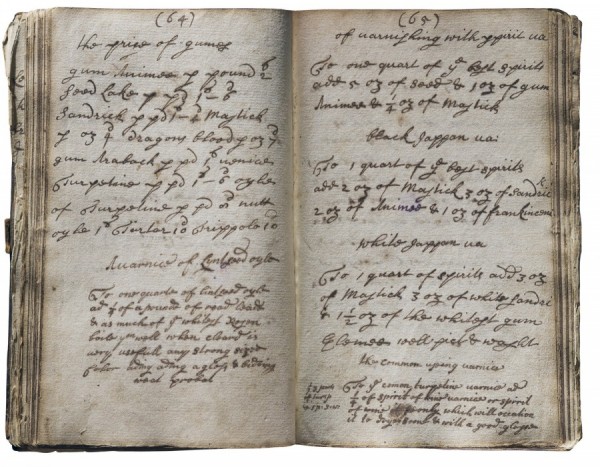

Left: Book block, page 64, numbered (60). Right: Book block page 65, numbered (61).

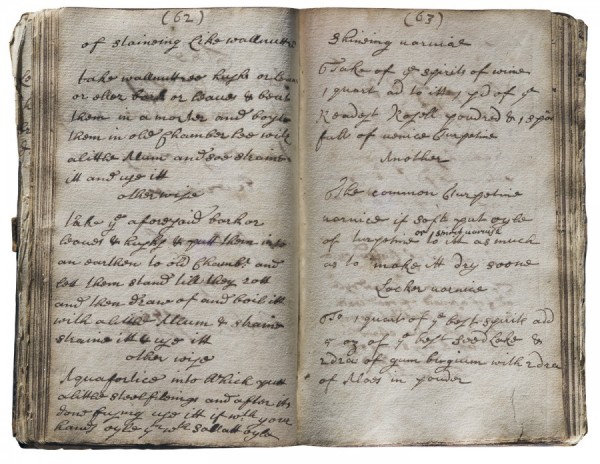

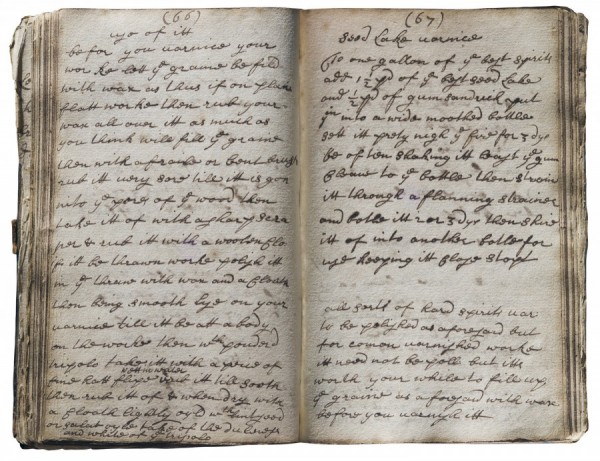

Left: Book block, page 66, numbered (62). Right: Book block page 67, numbered (63).

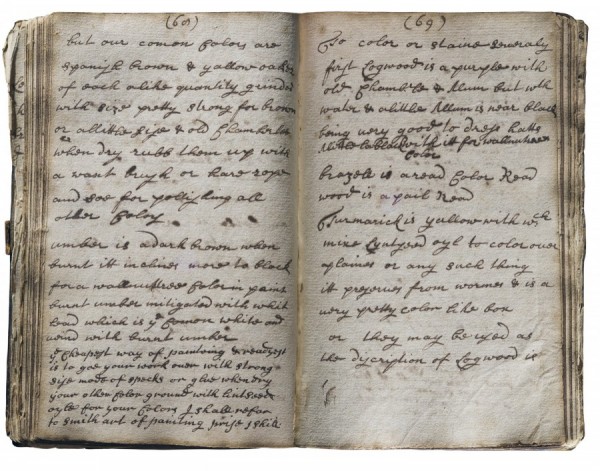

Left: Book block, page 68, numbered (64). Right: Book block page 69, numbered (65).

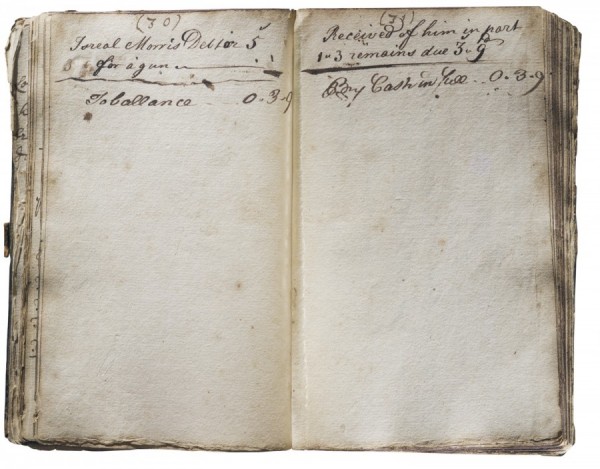

Left: Book block, page 66, numbered (70). Right: Book block page 67, numbered (71).

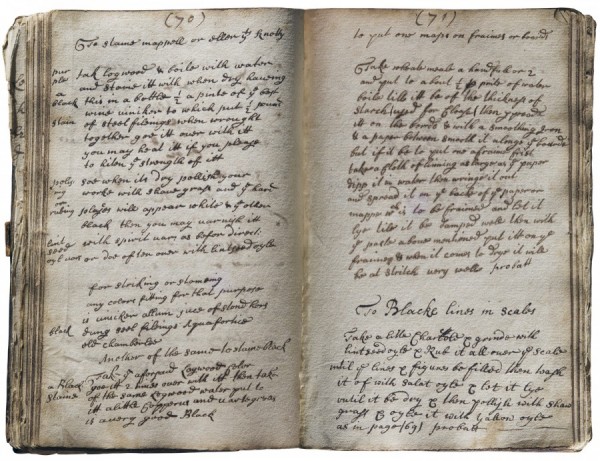

Left: Book block, page 72, numbered (68). Right: Book block page 73, numbered (69).

Left: Book block, page 74, numbered (70). Right: Book block page 75, numbered (71).

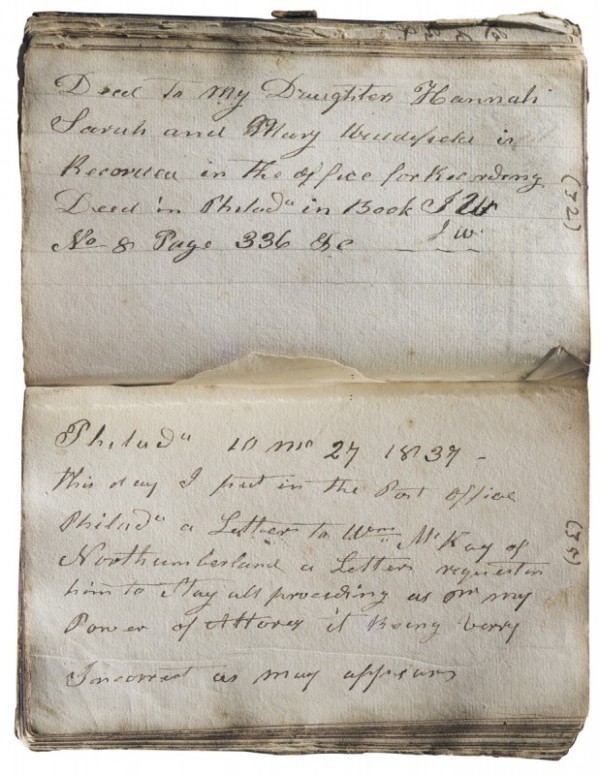

Left: Book block, page 76, numbered (72). Right: Book block page 77, numbered (73).

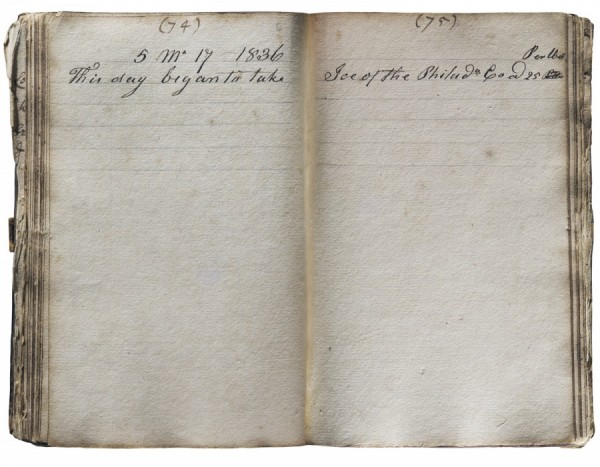

Left: Book block, page 78, numbered (74). Right: Book block page 79, numbered (75).

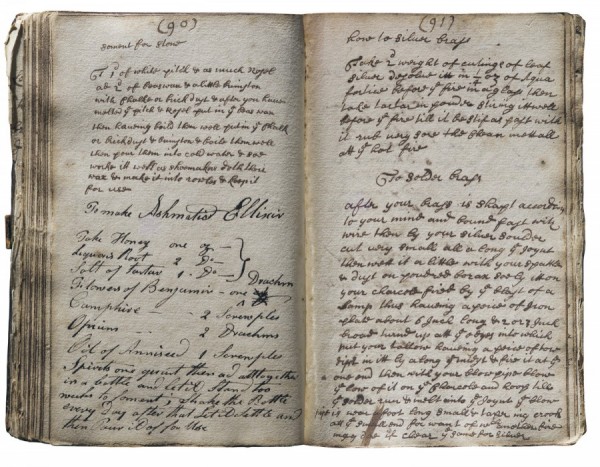

Left: Book block, page 94, numbered (90). Right: Book block page 95, numbered (91).

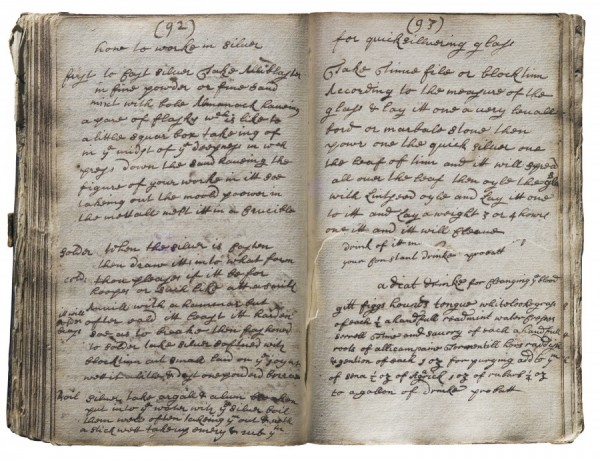

Left: Book block, page 96, numbered (92). Right: Book block page 97, numbered (93).

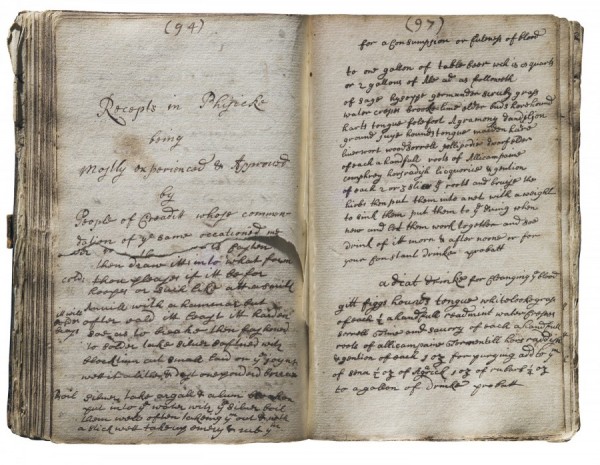

Left: Book block, page 98, numbered (94). Right: Book block page 101, numbered (97).

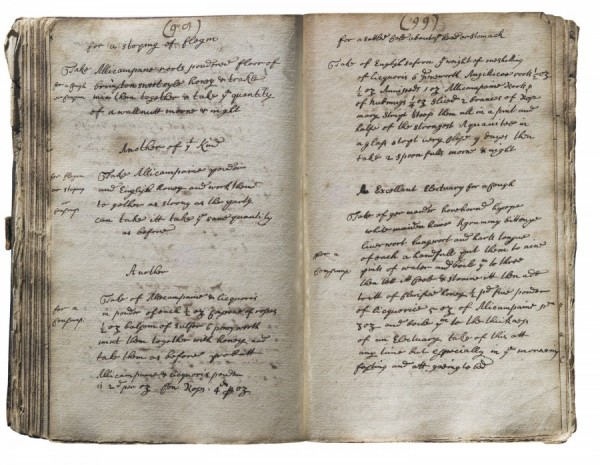

Left: Book block, page 102, numbered (98). Right: Book block page 103, numbered (99).

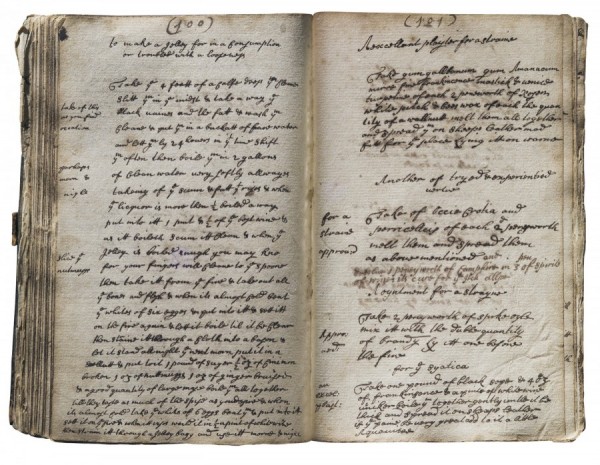

Left: Book block, page 104, numbered (100). Right: Book block page 105, numbered (101).

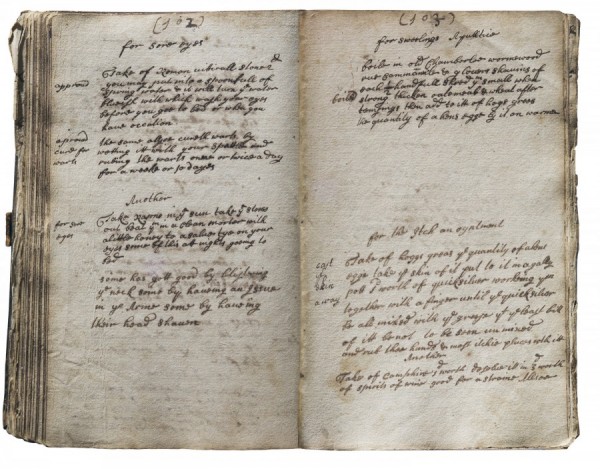

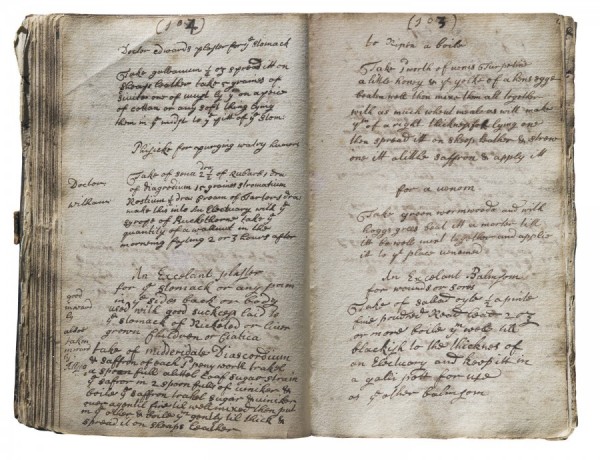

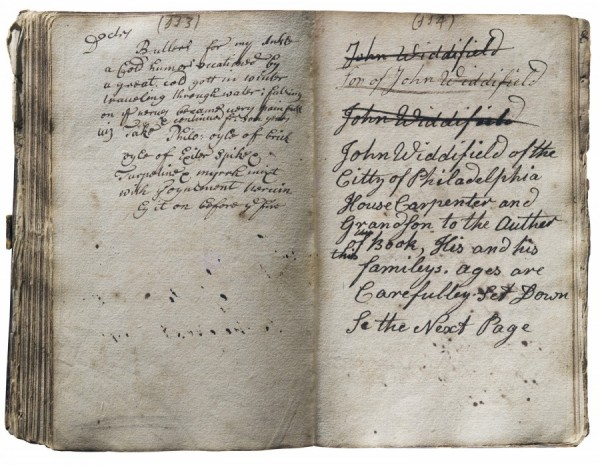

Left: Book block, page 106, numbered (102). Right: Book block page 107, numbered (103).

Left: Book block, page 108, numbered (104). Right: Book block page 109, numbered (103).

Left: Book block, page 110, numbered (105). Right: Book block page 111, numbered (106).

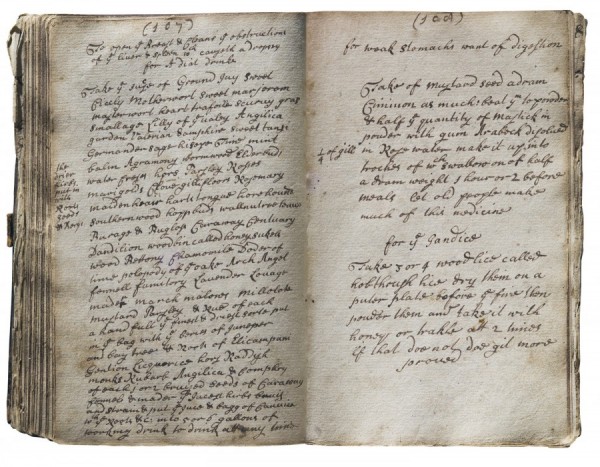

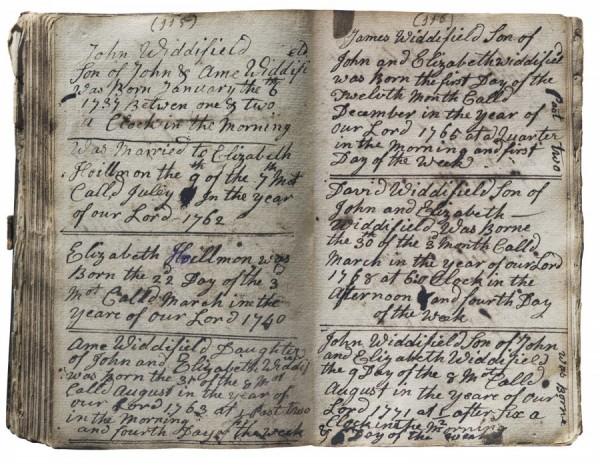

Left: Book block, page 112, numbered (107). Right: Book block page 113, numbered (108).

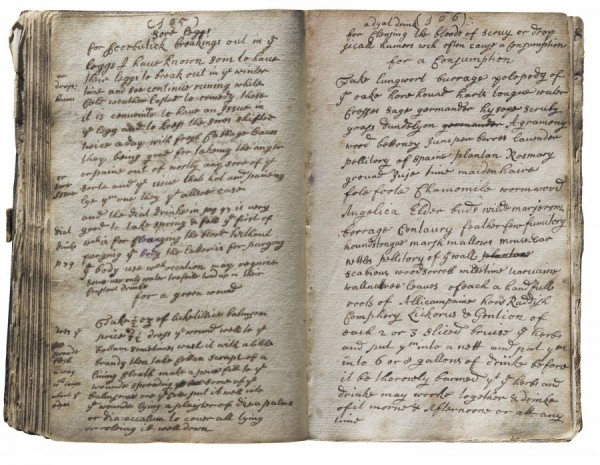

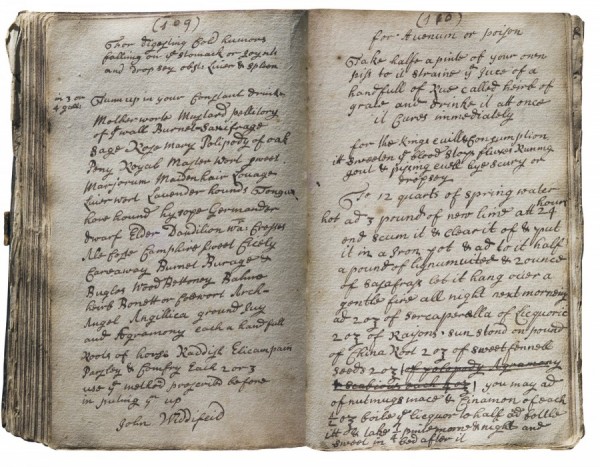

Left: Book block, page 114, numbered (109). Right: Book block page 115, numbered (110).

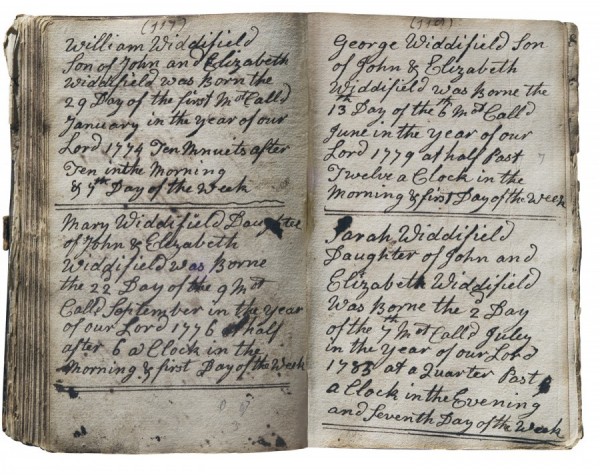

Left: Book block, page 116, numbered (111). Right: Book block page 117, numbered (112).

Left: Book block, page 118, numbered (1?3). Right: Book block page 119, numbered (114).

Left: Book block, page 120, numbered (115). Right: Book block page 121, numbered (116).

Left: Book block, page 122, numbered (117). Right: Book block page 123, numbered (118).

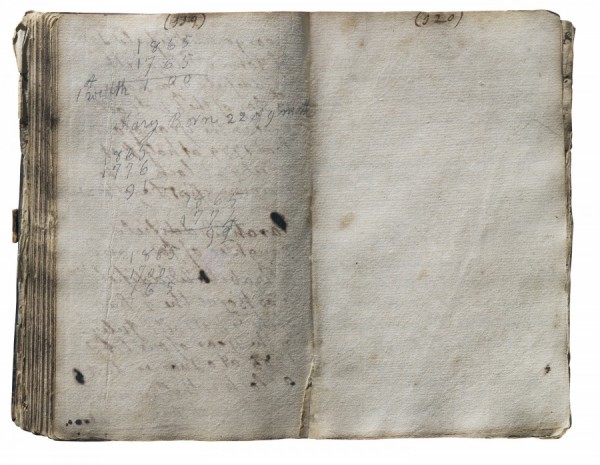

Left: Book block, page 124, numbered (119). Right: Book block page 125, numbered (120).

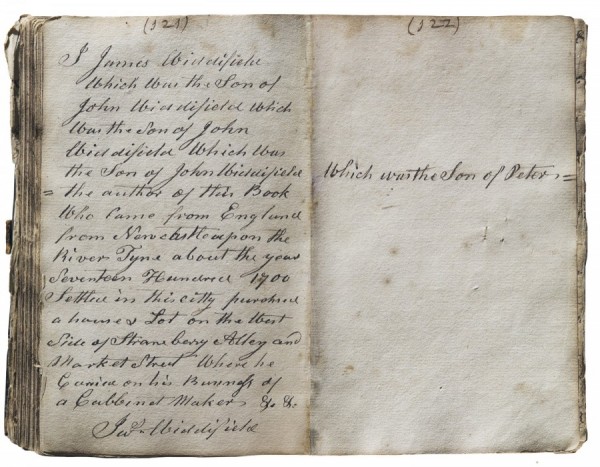

Left: Book block, page 126, numbered (121). Right: Book block page 127, numbered (122).

Left: Book block, page 130, numbered (125). Right: Book block page 131, numbered (12?).

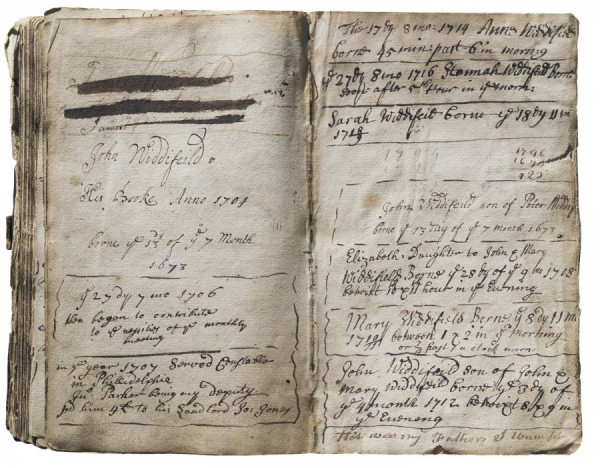

Left: Book block, page 132. Right: Inside back cover.

On September 17, 2015 Swann Galleries of New York sold a rare manuscript notebook kept by John Widdifield, an English furniture maker who immigrated to Philadelphia by 1705. The collector who acquired the book has generously allowed the Chipstone Foundation to publish it in this volume of American Furniture and make it, along with a keyword searchable transcription, available on the foundation’s website, www.chipstone.org, and that of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Widdifield’s notebook will also be designated as an ongoing research project on Chipstone’s website, thus allowing scholars, students, and others to publish work related to that manuscript. This introduction to the book is intended to begin that dialogue.

John Widdifield was born on September 13, 1673, or “ye 13 dy of ye 7 mo,” as recorded in the Julian calendar in his notebook. The notebook also states that his father was Peter, which, with the aforementioned inscription, contradicts several online sources giving his father’s name as John and the joiner’s birth date as 1676. The joiner’s father may have been Peter Widdifield of Bishop Auckland, a market town in County Durham in northeastern England. Bishop Auckland is about thirty miles south of Newcastle upon Tyne, where John lived at some point before immigrating to Philadelphia (fig. 2). His will indicates that he kept his “messauge” (dwelling house with outbuildings) in Newcastle upon Tyne, and that it was located “between Pilgrim Street and Upper Draw Bridge.” John’s mother may have been Elizabeth Marlys of Sadberge, a town about fifteen miles southeast of Bishop Auckland. She and Peter married on May 12, 1663.[1]

John Widdifield may have moved to Newcastle upon Tyne by early adulthood. His residence appears to have been on the western side of present-day Pilgrim Street near its intersection with Highbridge Street. According to R. J. Charleton’s A History of Newcastle-on-Tyne (1887), that location was near the meetinghouse of the Society of Friends, which was built in 1698. Earlier meetings were held at Gateshead, just outside the city limits. Assuming that Widdifield began his apprenticeship at the customary age of fourteen he would have completed his training about four years before the meetinghouse was erected.[2]

Throughout the seventeenth century, Newcastle upon Tyne had a guild for joiners (as well as separate guilds for several other woodworking trades), but a 1656 order denied membership to Quakers, Scots, Dutch, and Catholics: “No popish recusant, quaker or any who shall not attend duly on his maister at the public ordinances . . . be taken into apprentice on pain of being fined two marks.” If John converted to Quakerism after completing his apprenticeship, he could have served his term with a member of the joiners’ guild and possibly been a member himself. Widdifield was described as having been a Quaker for a “few years” in 1705.[3]

It is unclear when joiner John Widdifield immigrated to the colonies. On “4 mo. 29, 1705” (June 29, 1705), “John Widowfield” was received by the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, where he was described as a young man “who has been Conversant amongst a few also Since he came Among friends” and presented a letter of removal from “Mo. Mtg. at Thirsk” (Yorkshire) dated “7 mo. 14, 1703” (September 14, 1703) and a letter dated “4 mo. 12, 1705” (June 12, 1705) certifying that he “was unmarried when he left England”.[4]

Widdifield wrote that he “began to contribute to ye writings” of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting in 1706. The following year, he served as constable in Philadelphia and married Mary Lawrence (1687–1737), whose father, William, was a tailor. Together the couple had seven children: John (1712), Hannah (1716), Sarah (1718/1719), Ann (1714), Elizabeth (1708), Mary (1710/1711), and Peter (1720). John Jr. inherited the notebook, which has numerous genealogical inscriptions made by later generations of his family.[5]

Aside from the information in his notebook, details regarding the elder John’s career are scarce. He attained freeman status in 1717 along with joiners Robert Hubbard and Thomas Stappleford and carver Robert Mullard. The following year he witnessed the will of mariner Jacob Warren in which hatter Jacob Warder and brewer Anthony Morris were listed as trustees. Widdifield must have attained a measure of financial success by 1718. On September 10 he took John and Mary Usher as indentured servants, and on September 11 he and Mary paid joiner William Branson £51.10 for two parcels of land on High Street and Strawberry Alley. The deed for that property mentioned a “House & Office now intended to be built . . . by the said Widifield and . . . Branson,” which suggests that the joiners may have intended to form a partnership. The following day, Widdifield secured two adjacent lots and sold a lot on which he had built a brick dwelling house.[6]

A few references to Widdifield making furniture survive in addition to those in his notebook. James Logan’s account book has an August 7, 1717, debit to “John Widdowfield” for an “Oval Table” valued at £2.5 and a “Walnut Screen &c” at £10. Furniture historian William McPherson Hornor reported that in 1720 Widdifield made a “black Pine Screwtore,” had half ownership of two parcels of walnut logs (one “Lying near the Draw Bridge in Philadelphia valued at £25” and one “Lying at Perkiomen valued at £3”), and owned a “Cedar Chest of Drawers” and a “Small red Cedar Table”. Although Hornor neglected to provide citations, his source for all those references was Widdifield’s inventory. Taken on February 2, 1720, the inventory lists all of the “Goods &. chattles” in his shop and house as well as livestock and materials elsewhere:

|

his Wearing apparel |

13.10.0 |

|

Cash |

20.0.0 |

|

Goods in his Shop Amounting in the whole to |

209.10.0 |

|

One Clock & Case |

10.0.0 |

|

One black Pine Screwtore |

4.0.0 |

|

One Chest of Drawers |

5.0.0 |

|

Two Ovel black Walnut Tables |

3.0.0 |

|

One Large Looking Glass |

3.0.0 |

|

One Small Do. & other Glass on the Mantle piece |

2.10.0 |

|

Seven Rush bottom Chairs & other odd things in the Middle room below |

2.10.0 |

|

One Bed & bedste[a]d with the furniture |

20.0.0 |

|

One black Walnut Chest of Drawers |

6.0.0 |

|

One Small Walnut Table |

2.0.0 |

|

Two more Looking Glas[s]es |

2.10.0 |

|

Seven black Chairs & other furniture in the front Chamber |

4.10.0 |

|

Two other beds & bedste[a]ds with the furniture |

20.0.0 |

|

One Cedar Chestof Drawers a Small red Cedar Table |

6.0.0 |

|

One other Chest of Frawers looking Glass Chairs & other furniture in the upper front Chamber |

4.0.0 |

|

Two black walnut Chest of Drawers |

10.0.0 |

|

One Large black walnut table & Two Small Do. and a Mahogany Spice Box |

6.0.0 |

|

One Trunk & 4 old Chairs |

0.10.0 |

|

Two beds & bedste[a]ds with furniture & Other things in ye Garret |

5.0.0 |

|

One pair of Mahognay Drawers unfinished |

2.0.0 |

|

Sundry Joyner’s Tools Amounting to |

16.0.0 |

|

Two work benches |

1.0.1 |

|

Carrys Over |

£393.0.0 |

|

Brought Over |

£393.0.0 |

|

one other black walnut Chest of Drawers |

4.0.0 |

|

one hogshead of Mallasses & part of Another |

9.0.0 |

|

Two hogsheads of Tobacco |

4.0.0 |

|

One barrel of rosin |

1.10.0 |

|

Sundrey other Lumber in the Cellar |

3.10.0 |

|

Iron Pots brass Kettle & pewter in The kitchen |

8.10.0 |

|

One Large Ovel Walnut Table & A Small Do. in the Kitchen |

2.0.0 |

|

One Couch four Old Chairs |

1.0.0 |

|

Two Casks of Salt |

1.4.1 |

|

one Cask of Pipes |

2.0.0 |

|

a parcel of walnut boards Scantling & Plank in the yard |

6.0.0 |

|

Four Grind stones |

2.0.0 |

|

one Cow and Calf |

2.10.0 |

|

his half part of a parcel of Walnut Loggs Unsawn Lying near the Draw Bridge In Philadelphia |

25.0.0 |

|

his half of a parcel of Walnut Do. Lying at Perkasmey |

3.0.0 |

|

|

£470.4.0 |

Presumably Widdifield made much of the furniture listed above, and all of the forms are included in his notebook.[7]

The intent of Widdifield’s notebook is unclear, but its descent in his family indicates that he created it for his personal use as well as that of his heirs. A page devoted to sharpening shows that the purpose of the book was instructional, since Widdifield undoubtedly knew how to maintain his tools. His son John inherited the book, but he was born in 1712 and was only eight years old when his father died. It is possible that the elder Widdifield had planned to train his son and pass along the book when young John reached his majority. John Jr. is described as a “joyner” in two 1737 deeds, but his master’s identity and the precise nature of his trade remain unknown. Some craftsmen referred to as “joiners” limited their work to architecture. Later generations of the Widdifield family clearly treasured the notebook, as evidenced by their entries of births and other genealogical information more commonly inscribed in Bibles.[8]

The notebook contains entries that appear to have been made before Widdifield immigrated along with annotations and additions made after his arrival. The earliest date in his hand is “ye 26 th d 1 mo: 1704” (March 26, 1704), and it occurs on the first page, which states that “this book contains three parts”: “the measure of Tables drawers Chaires &c of household furniture maid by joners”; “staining Coloring & Varnishing with several other experienced Recp.s very useful”; and “Recepts in Physicke . . . for ye good of others.” The presence of several blank pages at the end of the adjacent “table of pages” and in the notebook itself reveals that Widdifield intended to add information as his career and experiences developed.

The furniture forms measured, described, and, occasionally, sketched in the notebook provide a glimpse of the range of English vernacular designs émigré joiners brought to the colonies during the early eighteenth century. Among those listed are a variety of seating forms (cane and leather chairs, armchairs, chair tables, child’s chairs, easy chairs, and stools), bedsteads (conventional as well as closatts [a bed made like a chest with an optional canopy]), tables (pine, oval, dressing, and chair), chests (single, double, on frame, and table), coat cases, presses, writing desks, clock cases, spice boxes, screens, hanging shelves, coffins, and clothes baskets. Most of the entries are not very descriptive, an exception being “A Writing table standing upon one pillar like a stand having two drawers.” The notebook also contains sketches of a spice box, a scrutoire, a chest-on-frame, and a “coffin mojaure” (which resembles a cradle) as well as prices Widdifield charged for certain types of objects.

Some of the entries in the notebook were clearly made after Widdifield arrived in Philadelphia. A page with the heading “spice boxes” has a sketch with the notation, “A little Scruetore for Thomas Lyfords” (fig. 3). His patron was probably the same Thomas Lyford who was received by the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting a few days before “John Widowfield” and produced a certificate of removal from the Meeting at Bull and Mouth in London dated “11 mo. 22, 1704” (January 22, 1704). Similarly, David Britnall Jr., for whom Widdifield made a bedstead, became a member of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting on “12 mo. 27, 1707/8” (February 27, 1707/1708). Other patrons mentioned in the notebook included Mary Lard (oval table), Jonathan Lucan (press), Edward Garmon (press), and William Rob (clock case).[9]

Widdifield’s sketch of Lyford’s scrutoire resembles two Philadelphia spice boxes (figs. 4, 5), one of which reputedly descended in the Morris family (fig. 4). Although the original owners of the boxes are unknown, brewer Anthony Morris, like Lyford, was a member of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting. The cases and frames of both boxes are constructed as a single unit, which is the impression given by Widdifield’s design. Their legs differ from the one shown in Widdifield’s sketch, but joiners often purchased lathe-generated components from different turners. The dimensions and drawer arrangement of Lyford’s scrutoire suggest that it was a tabletop form—possibly having a fall front—patterned after a spice box.[10]

The sections on coloring, staining, and varnishing and “Recepts in Physicke” were probably completed before Widdifield immigrated and contain few, if any, subsequent entries. His recipes and instructions for “Coloring Staining & Varnishing According to [his] . . . own Experience” are among the most comprehensive manuscript compendiums surviving from the early-eighteenth century. The closest published equivalent is John Stalker and George Parker’s Treatise on Japaning and Varnishing (1688) (fig. 6). Widdifield’s notebook is much more than a collection of recipes, measurements, and prices; it is a deeply personal creation that was a guide and an heirloom for his family and will be a resource for scholars in the years to come.[11]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their assistance with this introduction, the Chipstone Foundation thanks Gavin Ashworth, David Haugard, Alan Miller, Rick Stattler, Jay Stiefel, and Martha Willoughby. The Foundation is particularly grateful to Joseph P. Gromacki for his support of this publication and the digital initiatives associated with it.

John Widdifield notebook, last two pages (not numbered), private collection. http://www.myheritage.com/names/john_widdifield is one of several online sources citing John as the first name of Widdifield’s father and 1676 as the joiner’s birth date. The man who is identified incorrectly as the joiner’s father may have been the John Widdiwfield listed in the electoral roll of County Durham in 1675 (Ancestry.com. UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538–1893; Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 12012. Original data: London, England, UK, and London Poll Books. London Metropolitan Archives and Guildhall Library). Several online sources also note that émigré John Widdifield married Margaret O’Bourne (born in Dublin, Ireland) circa 1704 (http://www.myheritage.com/names/john_widdifield). Therefore, it is possible that two men by that name arrived in Philadelphia about the same time. Will of John Widdifield, written January 10, 1720, and probated January 21, 1720, Philadelphia County Wills, 1682–1819, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, available at Ancestry.com. Marriages, Darlington District, record no. 452513; www.durhamrecordsonline.com/ViewRecord.php. Peter and Elizabeth were married at St. Andrew’s [Anglican] Church. Joiner John Widdifield’s firstborn daughter was named Elizabeth, and his second son was named Peter (Widdifield notebook, last two pages). Although those are relatively common names, they support the theory that joiner John Widdifield was the son of Peter and Elizabeth.

R. J. Charleton, A History of Newcastle-on-Tyne (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: W. H. Robinson, 1887), pp. 188, 191, 421, 425–26.

Ibid. pp. 425–426. Quaker Arrivals at Philadelphia, 1682–1750, p. 36, https://archive.org/stream/quakerarrivalsa00myergoog/quakerarrivalsa00myergoog_djvu.txt.

Quaker Arrivals at Philadelphia, 1682–1750, p. 36.

Widdifield notebook, last two pages, lists six of his seven children and their birthdates. Peter was described as the joiner’s unborn child in Will of John Widdifield.

http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/j-thomas-john-thomas-scharf/history-of-philadelphia-1609-1884-volume-v1-ahc/page-51-history-of-philadelphia-1609-1884-volume-v1-ahc.shtml. See also Minutes of the Common Council of the City of Philadelphia, 1704–1776, pp. 122–23, available at Ancestry.com. Will of Jacob Warren, Philadelphia County Wills, 1682–1819, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1900, vol. D: 78, available at Ancestry com. For the land transactions and indentures, see Philadelphia County Deed Book H13, p. 86; Philadelphia County Deed Book F1, City Hall, Philadelphia, microfilm, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, pp. 327–30 (new numbering, pp. 361–65).

James Logan account book, 1712–1720, Logan Family Papers (collection 379), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. William Macpherson Hornor, Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture, William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: by the author, 1935), pp. 41, 42, 46. The inventory is filed with will of John Widdifield. Chipstone thanks Jay Stiefel for providing the location of the inventory.

Philadelphia County Deed Books F9, p. 123; and F10, p. 18.

Lyford was received on “4 mo. 29, 1705” (June 29, 1705) and described as “unmarried.” Quaker Arrivals at Philadelphia, 1682–1750, pp. 35, 36, https://archive.org/stream/quakerarrivalsa00myergoog/quakerarrivalsa00myergoog_djvu.txt. For David Britnall, see p. 40.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Morris_(I).

Widdifield’s section on finishes also includes directions for finishing, silvering, and soldering brass.