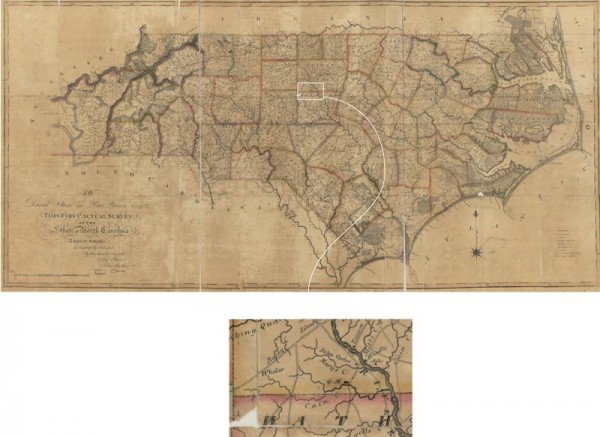

First Actual Survey of the State of North Carolina, Jonathan Price and John Strother (surveyors), W. H. Harrison (engraver), C. P. Harrison (printer), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1807. Ink on paper; 28 3/8" x 59 7/8". (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Washington, DC, G3900 1808 .P7 Vault.)

John and Rachel Allen House, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1782. (Courtesy, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.)

Table, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1780. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 27 7/8", W. 36 1/2", D. 30". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Armchair, Alamance or Chatham County, North Carolina, 1770–1780. Maple, hickory with split oak. H. 43 3/4", W. 24", D. 19". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gary Albert)

Armchair, Alamance or Chatham County, North Carolina, 1770–1780. Hickory with split oak. H. 43 3/4", W. 22", D.18 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Ats; photo, Dan Routh.)

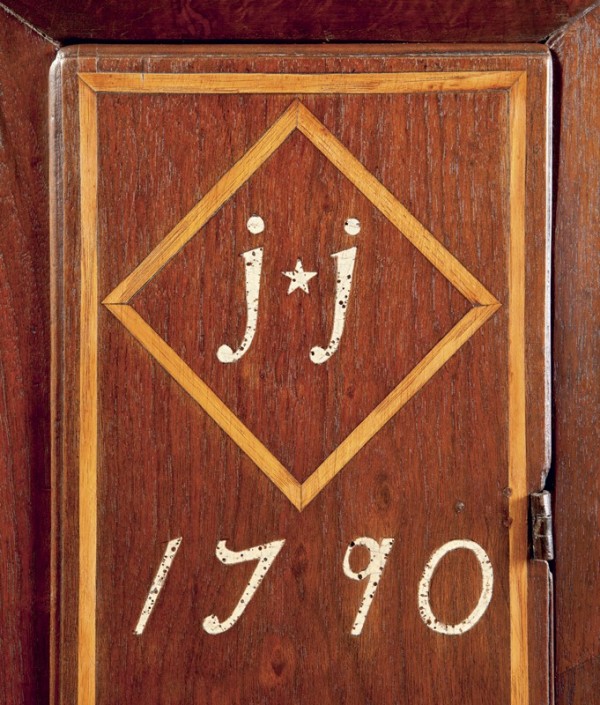

Tall case clock, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and light-wood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 98", W. 17", D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the scrolled pediment and fluted plinth block on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of the applied half columns on the door and hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of the wood and sulfur inlay on the door of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Tall case clock, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1799. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and light-wood with tulip poplar. H. 93 1/8", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the hood decoration on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left back foot of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790-1805. Walnut and light-wood inlay with yellow pine. H. 99", W. 19", D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail of the scalloped base panel on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the hood decoration on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a freestanding column on the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the brass clock face on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest, London Grove Township area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1746. Walnut and holly with white oak, white cedar, white pine, and sumac. H. 52 3/8", W. 40 3/4", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, The Dietrich American Foundation.)

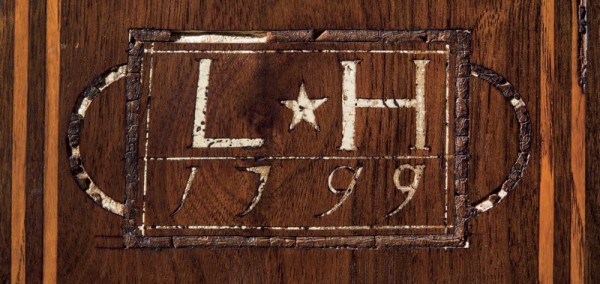

High chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1796. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 56", W. 41 1/2", D. 20 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the high chest illustrated in fig. 21.

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the high chest illustrated in fig. 21.

Detail of the cornice molding on the high chest illustrated in fig. 21.

Detail of the front left ogee foot and integral protruding base molding of the high chest illustrated in fig. 21.

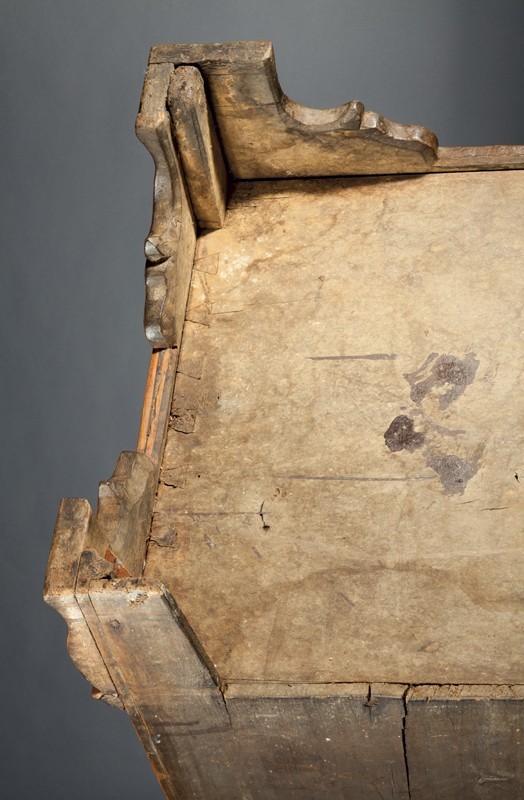

Detail of the underside of the high chest illustrated in fig. 21. The bottom board is dovetailed to the case sides, and the back edges of the feet are slightly chamfered.

Detail of a pinned drawer bottom from the high chest illustrated in fig. 21.

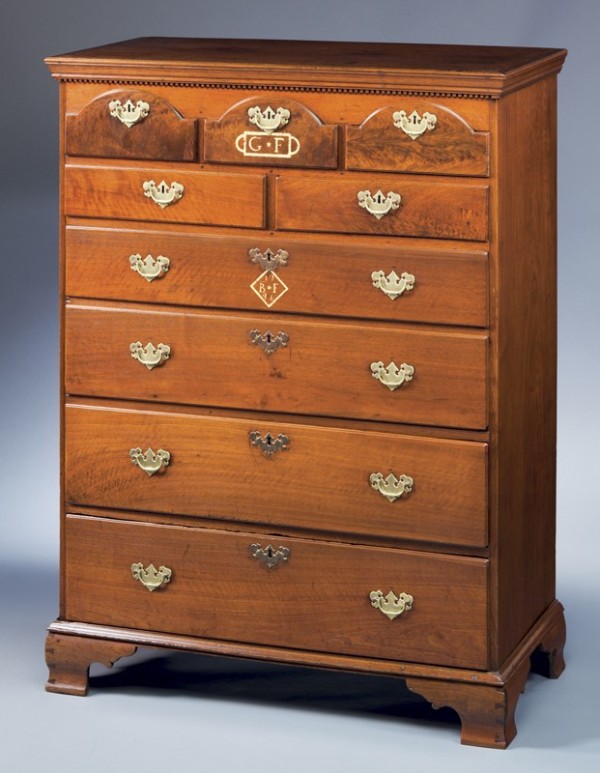

High chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 58 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the high chest illustrated in fig. 28.

Detail of the left front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 28. The bottom of the foot retains its beaded edge, a feature that is sometimes either worn or cut off.

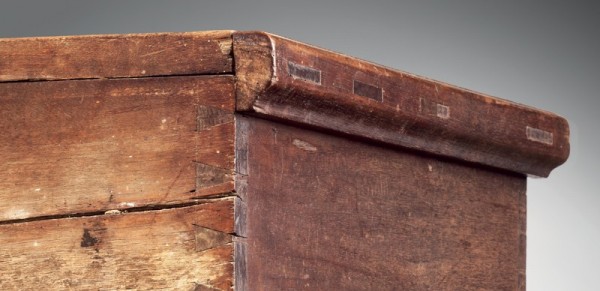

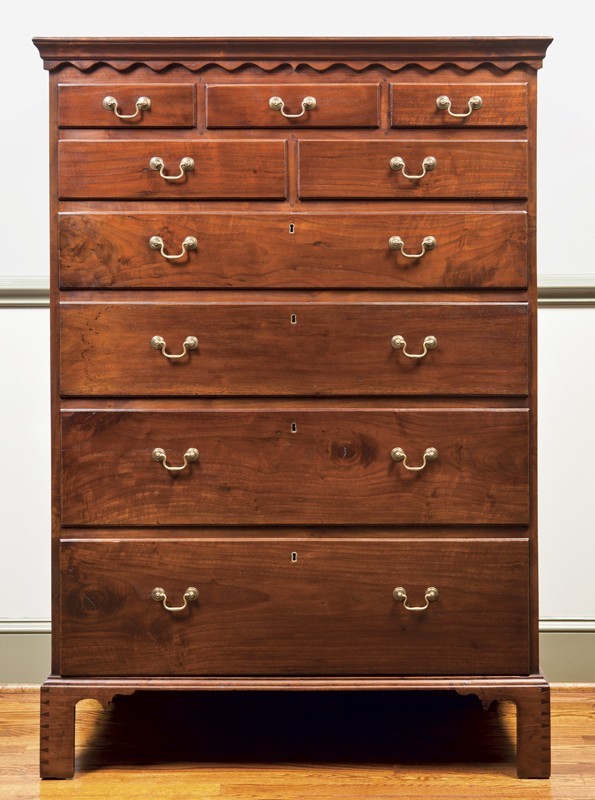

High chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1802. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and light-wood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 58 3/4", W. 43", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the high chest illustrated in fig. 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 55", W. 37 1/2", D. 20 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) One atypical construction technique used here is side boards that are splined together and pinned once on each side of the spline.

Detail of the cornice molding on the high chest illustrated in fig. 33.

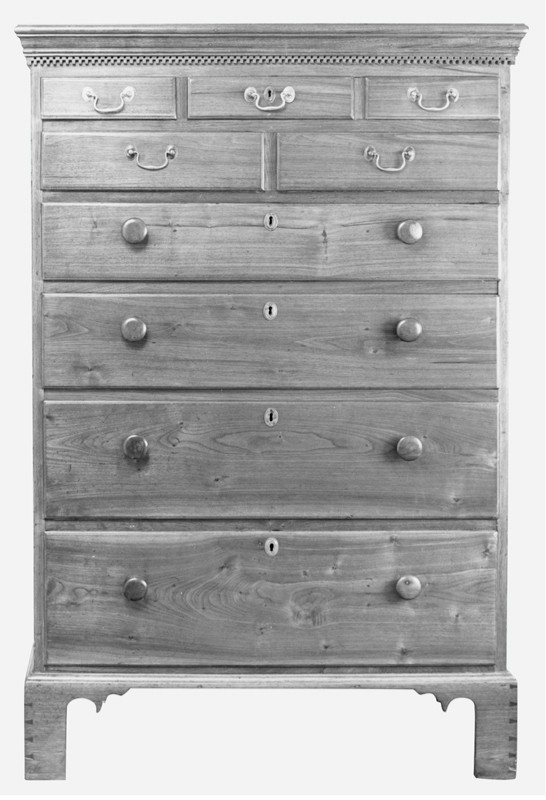

High chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 56 3/4", W. 42 1/4", D. 21 1/22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This high chest has a small hidden drawer above the upper left small drawer.

Detail of the cornice molding on the high chest illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 18 1/8", W. 15 7/8", D. 11 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart).

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and light-wood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 25 7/8", W. 47 7/8", D. 20 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gary Albert.)

Detail of the sulfur and wood inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 38.

Detail showing the pinned battens on the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 38.

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 27", W. 50", D. 21". (Courtesy, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources; photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pinned molding on the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bead on the back of the lid on the chest illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1805. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 28", W. 50", D 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart).

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 45.

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 25 1/2", W. 48 1/2", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

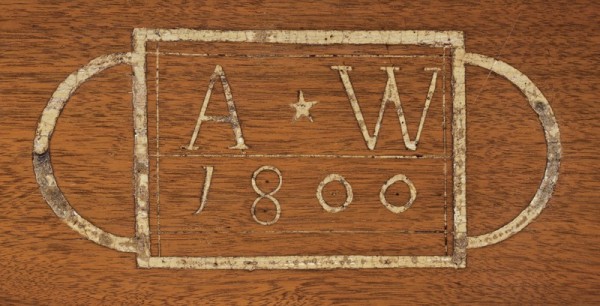

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 47.

High chest, Alamance or Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800–1815. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 59 1/2", W. 40", D. 21 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The sides extend to form foot supports, but the sides are dovetailed to the bottom in between the extensions; this same construction technique was used on the high chests illustrated in figs. 21, 28, 31, 33, and 35.

Detail of the cornice molding with a drilled dot and dentil band on the high chest illustrated in fig. 49.

Detail of the left front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 49.

High chest, Alamance or Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800–1815. Walnut and light-wood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 70 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.) Drawer bottoms on this example are nailed rather than pinned.

Detail of the cornice molding and upper left drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 52. All drawers have light-wood stringing.

Detail of the left front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 52. Instead of a beaded bottom edge, this example has a bottom edge decorated with string inlay.

Dish dresser, Alamance or Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800–1815. Walnut and light-wood inlay with tulip poplar and cherry. H. 85 1/4", W. 61 1/4", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The doors have raised panels which, along with the drawer fronts, are decorated with string inlay like that found on the high chests illustrated in figs. 31 and 52.

Detail of the frieze on the dish dresser illustrated in fig. 55. )

Detail of the cornice molding and frieze on the dish dresser illustrated in fig. 55.

Detail of the right front foot of the dish dresser illustrated in fig. 55.

Chest by Jeremiah Piggott and Joseph Cloud, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 28 3/4", W. 51 1/2", D 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the right front foot of the chest illustrated in fig. 59.

Detail showing the through tenons securing the side molding on the chest lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 59.

Details showing the removable board above the two drawers of the chest illustrated in fig. 59.

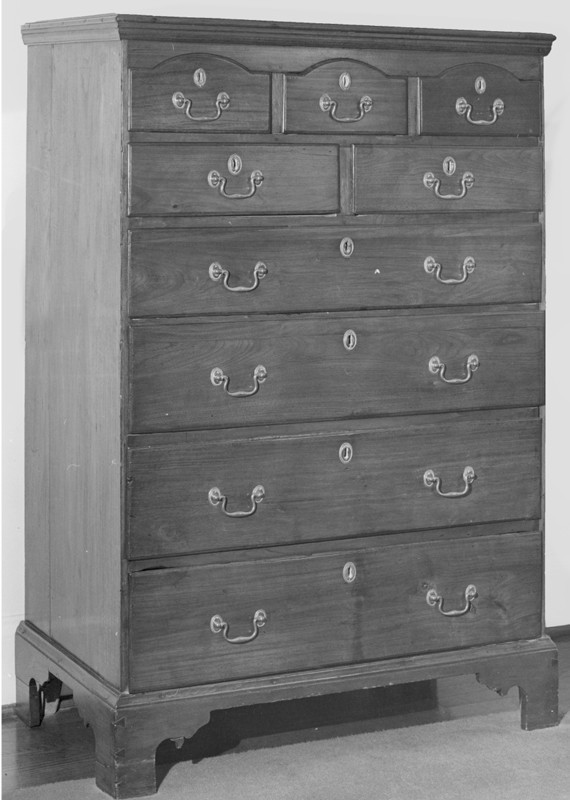

High chest by John Piggott, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1810–1835. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 59 3/8", W. 40 3/16", D. 22 5/16". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gary Albert.) The drawer bottoms, cornice molding, and backboards are attached with small wooden pins. The sides extend to support the case, but the bottom boards are nailed to the sides instead of being dovetailed.

Detail of the cornice molding on the high chest illustrated in fig. 63.

Detail of the left front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 63.

High chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1810–1835. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 59 5/8", W. 39 3/4", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

High chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1810–1835. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 60", W. 42", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the left front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 67.

Tall case clock, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 96 1/2", W. 20 1/2", D. 12 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the pediment of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 69.

Detail of the left front foot of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 69.

Tall case clock, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 96", W. 19 1/2 D. 12". (Courtesy, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably Randolph County, North Carolina, 1794. Walnut and sulfur with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 24", W. 45 1/4", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail of the left front foot of the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail of a foot support block on the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail showing a support block extending through the bottom of the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail showing the lid construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Chest, probably Randolph County, North Carolina, 1802. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 23 1/2", W. 41 3/4", D. 18 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 79.

Detail of the left front foot of the chest illustrated in fig. 79. This foot is attached to a coved glue block that extends through the chest bottom, a construction detail identical to that on the chest illustrated in fig. 73.

Chest, attributed to Moses Pyle, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1746. Walnut and mixed wood inlay with yellow pine. H. 11 3/4", W. 21", D. 13". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Chest, attributed to Moses Pyle, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1747. Walnut; sumac, maple, and holly inlay with white oak, white cedar, and tulip poplar. H. 14 1/2", W. 21 1/8", D. 131/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Cane creek is a gentle, pastoral waterway that runs approximately fifteen miles along the border between present-day Alamance and Chatham counties in central North Carolina. From 1752 to 1849 Alamance was part of Orange County, as was Chatham until 1770. The creek meanders eastward toward the swiftly flowing Haw River, part of the Cape Fear River Basin that empties into the Atlantic Ocean at the port of Wilmington (fig. 1). The alluvial soil and abundant forests located on the gently rolling hills and plateaus of the Haw River region lured settlers very early. In 1701 English explorer John Lawson described the area as one containing “plenty of good timber,” extraordinarily rich land, “stone enough” for building, and quantities of “fat bear and venison.” In contrast to the eastern part of the state, which he described as the “fag-end of that fine Country,” Lawson viewed the region along the Haw River and its tributaries as “the Flower of Carolina.”[1]

By the middle of the eighteenth century, when the Indian wars were over, John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville, began offering tracts of land from his vast Carolina holdings at bargain prices, enticing new inhabitants of varied ethnic and religious backgrounds to settle in the area, including the Haw River valley. Most immigrants made the roughly four-hundred-mile trek south from more crowded and expensive areas of southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Maryland and Virginia, often leaving behind fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters. German settlers, who typically founded Lutheran and Reformed churches, purchased most of the land northwest of Cane Creek, along Alamance and Stinking Quarter Creeks. Approximately fifteen miles northeast, along the Haw River, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians founded their own communities. The land on Cane Creek and its tributaries, known as the Cane Creek Settlement, was largely populated by a third group of settlers—English and Irish Quakers, who founded Cane Creek Meeting (see fig. 1). The furniture produced by Cane Creek woodworkers bears a striking resemblance to work from southeastern Pennsylvania, particularly the Chester County area, where many North Carolina families originated. Occasionally, Cane Creek furniture exhibits characteristics traditionally associated with non-Quaker groups, particularly Germans. This article will explore the transfer and subsequent melding of cultures in the Cane Creek Settlement as they are reflected in the furniture made and used there.[2]

Cane Creek Quakers: Establishing a Community

Although Quakers had settled in coastal North Carolina by the mid-1670s, their arrival in the Cane Creek region dates from the mid-eighteenth century. By 1750 a sufficient number of families lived in that area of the piedmont to justify the establishment of a monthly meeting. At the Quarterly Meeting held at Little River in Perquimans County (northeast North Carolina) on the “31st of the 6th month 1751—Several Friends from them Parts [Cane Creek] appeared... & acquainted Friends that there is Thirty Families and upwards of Friends settled in them Parts and desire still in behalf of themselves & their Friends to have a Monthly Meeting Settled amongst them.” Most of the thirty families that populated the region were widely scattered and, like almost all of the region’s early settlers, lived in small, windowless log cabins, probably very similar to the circa 1780 house of Quakers John and Rachel Allen (fig. 2). Theirs is one of the few regional examples to survive intact, although it was moved from its original site on the banks of Cane Creek in 1967. Farming was the primary occupation of most local men, but many also practiced trades including blacksmithing, wagon making, tanning, and woodworking. Records pertaining to John Allen suggest that, in addition to being a farmer, at various times he was a storekeeper, woodworker, day laborer, and teacher.[3]

Ironically, the pacifist Quakers of Cane Creek Meeting had only about fifteen years to establish their wilderness settlement in peace before regional conflict arose and they were drawn into the fray, not as participants but as bystanders to violence. By 1765 rumblings that presaged the War of Regulation were audible in the region. The goal of this prerevolutionary, inland movement was to ensure that the colonial economy was fair for backcountry farmers, not just for the eastern Carolina government officials whom many considered corrupt. Hostilities culminated in 1771, when local farmers and the New Bern militia of Royal Governor William Tryon fought at the Battle of Alamance. The short but deadly skirmish took place approximately fifteen miles northwest of Cane Creek Meeting House. Many Quakers knew men who were directly involved, such as local resident Herman Husband, one of the reputed leaders of the group.[4]

Cane Creek Quakers and their neighbors also suffered during and after the American Revolution. In February 1781 North Carolina patriot and loyalist troops met in a bloody battle known as Pyle’s Massacre, fifteen miles northeast of Cane Creek Meeting House. The following March, as Lord Cornwallis was heading toward Wilmington after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, he and his troops camped at Quaker Simon Dixon’s gristmill and stone house just one mile south of the meeting house, killing large numbers of local residents’ livestock and taking any other food they could find. Six months later, deadly skirmishes fought between Carolina patriots and loyalists at the Battle of Lindley’s Mill (also known as the Battle of Cane Creek) occurred just a few miles east of the meeting house.[5]

Furniture Made Before Circa 1790

The upheaval, conflict, and devastation of property in the Cane Creek region in the years leading up to and during the Revolutionary War may explain why so little furniture made there before 1790 survives. The only known candidates are an oval-top stretcher table and two armchairs. The table (fig. 3) is problematic because its nondescript leg turnings are virtually impossible to date. Simple turned and joined tables of this type were made by a variety of craftsmen, including cabinetmakers, house joiners, turners, and wheelwrights. The most distinctive feature of the Cane Creek example is its maker’s use of wooden pins to secure all the components, including the drawer bottom and drawer supports. The pins for the supports are relatively large and visible on the outer faces of the side rails. The Cane Creek table descended through the Hornaday family of Alamance County. Although there is no evidence that John Hornaday (1725–1807), the progenitor of all the Hornadays in the region, was ever a Quaker, at least one of his sons, Lewis (1755–1837), became a member of Cane Creek Meeting. John appeared as a “tythable” in the Orange County Tax List for 1752–1753. In June 1757 he bought property on Mud Lick Creek in what is today northern Chatham County, approximately two miles southwest of Cane Creek Meeting House, and presumably raised his family there. By 1788 John and his wife, Christian, had moved to South Carolina, but they left behind several children. Simon Hornaday (1765–after 1850) was the son through whose family the table descended. He married Esther (maiden name, birth date, and death dates unknown), and it was through their daughter Ruth Hornaday Lowe (1803–1875), wife of Weston Lowe (1801–1845), that the table descended to Miley Melinda Lowe (1845–1927), their daughter. According to a note attached to the table, Miley remembered that it “was her Grandmother’s dining table,” and that it was made in the Cane Creek region circa 1765. Since that date is too early for the table, it was more likely made for Simon and Esther Hornaday.[6]

The slat-back armchairs (figs. 4, 5) are similar to southeastern Pennsylvania examples made from the 1730s into the early nineteenth century. Like their stylistic antecedents, the Cane Creek chairs have concave arched slats, simple rear posts with turned finials, front posts with vasiform turnings, and graceful arms shaped on both the top and bottom. Local lore suggests that Quaker Simon Dixon brought the chair illustrated in figure 4 with him when he moved from Pennsylvania to North Carolina in 1751, but that object was almost certainly made in the Cane Creek region about thirty years later. Tradition maintains that it was “occupied by Lord Cornwallis, March 1781 on his retreat from Battle of Guilford.” Simon Dixon’s great-grandson Thomas owned the chair in 1871. In 1887 he wrote a brief family history that detailed Cornwallis’s encampment at Simon’s house, but he did not mention the chair. The second armchair (fig. 5) was found in northwestern Chatham County, three miles west of Siler City. Its turnings are slightly different from those on the Dixon family chair, but both have graduated slats, plain stretchers, and similarly shaped arms.[7]

Furniture made in the Cane Creek settlement from 1790 to 1835 is much more plentiful. Several pieces have strong histories of ownership in the region or maker’s signatures. This large group of interrelated objects probably represents the work of masters and their journeymen and apprentices and reflects the preference for certain forms, designs, and ornamental details within the Quaker community and its non-Quaker periphery.

Early Furniture from the Cane Creek Group

The earliest furniture from the Cane Creek school consists of clocks and a variety of chest forms made between 1790 and 1805. Every example is made of walnut, and tulip poplar is the most common secondary wood, followed by yellow pine. Several pieces are decorated with sulfur inlay, which, as Lisa Minardi’s encyclopedic article in the 2015 volume of American Furniture has shown, first appears in Pennsylvania-German furniture from Lancaster County, and some have sulfur and wood inlay combined. Most of the Cane Creek pieces have pinned mortise-and-tenon joints and drawer bottoms and wedged dovetails. All of the high chests have sides that extend to the ground and support the case, and all of the examples with original, applied bracket feet share the same inner foot profile, consisting of an ogee element, a slightly rounded spur, and an arch.[8]

The earliest piece in the Cane Creek group is a tall case clock dated 1790 (fig. 6), one of three examples likely made in the same shop. It exhibits the single most distinguishing characteristic of locally made cases: scroll moldings with very shallow cyma curves and concave volutes (fig. 7). A fluted plinth block surmounted by a finial separates the volutes, but there is no evidence of plinths for the corner finials. Unlike other clock cases in the group, this example has an unusually tall hood, suggesting that it was designed to house an elaborate German movement similar to the replaced one currently installed. The door is attached to the side of the case, and its corners are decorated with applied half-columns matching those at the back of the hood (fig. 8). Wide light-wood inlay outlines the rectangular waist door and creates a diamond enclosure for a small, sulfur-inlaid star and the original owner’s initials, “jj.” The maker also used sulfur to inlay the date directly below (fig. 9).

Although the identity of “jj” is unknown, the clock was once owned by J. George Hanner (1846–1916), who lived in northwestern Chatham County, approximately twelve miles south of Cane Creek. Judge Walter D. Siler, a local historian, purchased the clock for $40 at Hanner’s estate sale in 1916. The names and life dates of Hanner’s parents, John Gillespie Hanner (1806–1849) and Ann Palmer Goldston (1824–1889), exclude them as being the original owners, and no known ancestors in either the Hanner or Goldston lines had the initials “jj.” Regardless of who its original owner was, the clock made an impression on early viewers. In the July 31, 1890, issue of the Chatham Record, a correspondent from Siler City reported that “Mr. J. Geo. Hanner has in his possession an old long clock made in 1790, thereby being 100 years old this year. It is quite wonderful in mechanism and will be a great curiosity at the world’s fair in 1892, there being only two or three of that make in existence.” Whether the clock was actually exhibited in Chicago in 1893 is unknown, but this brief newspaper description indicates that the clock was considered a novelty in the region more than 125 years ago.[9]

A second clock with both wood and sulfur inlay (fig. 10) has another typical sulfur design—initials separated by a five-pointed star, a date, and narrow bands forming rectangles that separate the numbers and letters, all enclosed in a rectangle with astragal ends (fig. 11). Its scroll moldings are identical to those on the 1790 clock, but directly beneath them is a combination of closely spaced wooden pins, along with a light-wood astragal bead, that follows the shape of the hood door and continues across the frieze and around each side (fig. 12). The clock originally had finials above the plinth and on each side of the pediment. The most distinctive feature of this object is its pseudo-cabriole front legs, which are decorated with stylized leaves that emanate from small, tightly wound volutes and terminate in small claw-and-ball feet (fig. 13). The back legs are more akin to ogee feet, and their inner profiles match those of straight bracket feet in the Cane Creek group (fig. 14). Of all the objects from that group, this clock is the most ambitious in design. It has no history, but its “LH” initials and 1799 date make Lewis Hornaday (1755–1837) a likely candidate to have been its original owner. He was a very prominent resident of the Cane Creek community and could easily have afforded an expensive tall case clock like this example.[10]

The third tall case clock (fig. 15) has no sulfur or wood inlay, but its considerable height; pleasing proportions; arched, paneled waist door; and scalloped base panel make it one of the most aesthetically successful objects in the early group (fig. 16). This clock has scroll moldings like those on the preceding examples, as well as decorative wooden pins and light-wood beading (fig. 17) like that on the hood of the LH case (fig. 10). The clock illustrated in figure 15 is also the only one with freestanding columns on the hood (fig. 18). Its movement appears to be original and has a brass face engraved with stylized flowers encircling the name “Joseph Pyle” (fig. 19).[11]

Two men named Joseph Pyle lived near Cane Creek in Chatham County during the period when the clock was made. In 1792 a Joseph Pyle purchased a tract of land from Hezekiah Clark in Chatham County. A Joseph Pile, probably the same man, was also listed in the 1800 Chatham County census. Samuel Pyle, also of Chatham County, mentioned a brother and son both named Joseph in his 1801 will. Samuel’s brother was probably the Joseph Pyle who bought land from Clark. Unfortunately, the parents of Samuel and his brother are not known, but either Joseph could have been the tall case clock’s owner or its movement’s maker.[12]

If the Joseph Pyle whose name appears on the dial of the clock was its maker and trained locally, his master almost certainly was Thomas Dixon (1753–1824), the only early clockmaker documented in the Cane Creek Settlement. Thomas was the eldest son of Simon Dixon, who is reputed to have owned the chair illustrated in figure 4. According to T. C. Dixon’s family history, “Thomas was sent to Philadelphia to learn his trade as a silversmith and clock making, and after his return kept a shop for the repair of clocks, watches, etc.” In 1779 Thomas bought 300 acres on Cane Creek bordering John Allen’s land and the following year married Abigail Stuart. After his father’s death in 1781, Thomas inherited a 640-acre tract on the South Fork of Cane Creek in Chatham County. He was identified as a “Clock Maker” in deeds in 1784 and 1785, and surveyed land in Orange County in 1794. The estate inventory of Thomas’s father listed one clock appraised at £11.8s, the highest value placed on any piece of furniture, including “beds and furniture,” which were typically more expensive. Presumably, Thomas would have provided the movement for his father’s clock, as well as most of those in cases made in the Cane Creek Settlement.[13]

Four high chests with an upper rank of three, equal-sized, arched drawers have survived from the Cane Creek group. The form of these chests relates directly to those made by Quakers in Chester County, Pennsylvania, as early as 1745 (fig. 20). The most successful of the Cane Creek high chests (fig. 21) was probably made by a North Carolina Quaker who served his apprenticeship in southeastern Pennsylvania or trained with a master who did. George and Barbara Foust (also spelled Faust), whose initials are inlaid in sulfur on the façade (figs. 22, 23), commissioned the chest in 1796. In addition to having decorative details similar to those on the clocks illustrated in figures 6 and 10, the Foust chest exhibits other characteristics of the Cane Creek group: a drawer configuration of three over two over four, a cornice molding composed of an ogee with astragal above and below (fig. 24), feet with exposed, wedged dovetails (fig. 25), case sides extending to the ground (fig. 26), and drawer bottoms that are pinned to the drawer backs (fig. 27). Less common characteristics are the dentil band beneath the cornice molding, the protruding base molding, and the shallow ogee shape of the feet, although the latter two features are not unlike those on the clock illustrated in figure 10.[14]

The history of the Foust high chest illustrates ethnic interaction and influence in the Cane Creek Settlement. Seven-year-old George Foust (1756–1836) moved to North Carolina with his parents, who were members of a German Reformed church in Berks County, Pennsylvania. In 1763 his father, John (1719–1789), bought property from John Johnes on the “waters of Cane Creek,” in the heart of the Quaker community. When John Foust made his will in 1786, his witnesses were members of Cane Creek Meeting: brothers Joseph and Samuel Stout. When John Foust deeded his Cane Creek property to his youngest sons, Peter and Daniel, a month before he died in 1789, the witnesses—Jacob Marshall and James Neal—were also members of Cane Creek Meeting. Considering his parents’ interaction with members of the Quaker community, one can assume that young George followed suit as a child and as an adult. In September 1778 George bought his first piece of property, “300 acres Land lying on both sides of Wills’s [Wells] Creek bounded on the south by Land of Josh. [Joseph] Wills [Wells].” Wells Creek was a tributary of Cane Creek, presumably named for Joseph Wells Sr., one of the earliest Quakers to settle in the area. The following month, George married Barbara Kivett, whose parents lived in a German community about fifteen miles southwest in Randolph County, and the newly married couple began their lives as residents of the Cane Creek Settlement. George and Barbara raised nine children and prospered. He was a blacksmith and very successful farmer. By 1830 George owned thousands of acres as well as twenty-three slaves, a very large number for a resident of backcountry North Carolina. Despite the fact that he and his family lived in the heart of a Quaker community, they routinely traveled ten miles to worship at Stoner’s (Steiner’s) (German Reformed) Church, which his father helped found. The couple may have moved later in life. Nearly all of the property George purchased after 1786 was north of the Cane Creek Settlement, closer to Germans living along Alamance Creek. As slave owners, he and Barbara may have become uncomfortable living among the abolitionist Quakers. If the Fousts did move, they apparently maintained contact with members of the Cane Creek Settlement and continued to do business there. George was listed as a buyer at local sales during the late eighteenth century, and he and his wife evidently commissioned a member of the Cane Creek community to make their high chest in 1796. His two youngest bothers, Peter and Daniel, inherited their father’s property and never left the area. Daniel was also a slave owner, but he requested that the slaves be freed at his wife’s death. The interactions between the German Fousts and their Quaker neighbors suggest that before 1800, marriage and worship within one’s own ethnic, cultural, and religious group were the norm, but business transactions were much more fluid. The Foust high chest can be viewed as a physical manifestation of those patterns.[15]

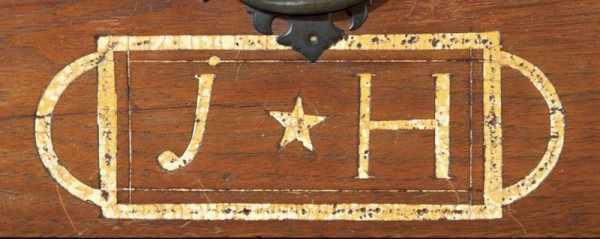

Quakers Joshua and Ruth Hadley commissioned a similar high chest with the sulfur-inlaid initials “jH” (figs. 28, 29). The chest does not have a date or dentil course in the cornice, and its straight bracket feet and more traditional base molding are integral. However, the cyma and cusp elements of the feet (fig. 30) are essentially the same as those on the ogee feet of the Foust chest (fig. 25). Joshua Hadley (1743–1813) was born in New Castle County, Pennsylvania, and went to the Cane Creek Settlement with his family from New Garden Monthly Meeting in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1756. He married Ruth Lindley (1745–1798) circa 1761. Ruth was reported to have married out of unity, but the births of thirteen of her and Joshua’s children were recorded in the Minutes of the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting. Joshua’s properties were located a few miles south of Cane Creek Meeting House in Chatham County on South Fork, Rocky River, Little Cain Creek, and Pine Hill Creek. He appears to have been a successful farmer, although he also owned property with a mill site in Randolph County. Joshua and his family began attending Spring Monthly Meeting shortly after it was founded in 1793. That meeting was located about two miles east of the Cane Creek Meeting House, and both Joshua and Ruth were buried there. Joshua married twice after Ruth’s death in 1798, but the high chest was probably made while she was alive. According to Anna Lois Dixon, a local Cane Creek historian, the piece descended to her husband, James Thomas Dixon (1888–1962), the son of Peter Dixon (1857–1917). Peter was the son of Caleb Dixon (1816–1884), whose parents were Jesse Dixon (1784–1873) and Catherine Hadley Dixon (1785–1862), the daughter of Joshua and Ruth Lindley Hadley. Peter confirmed to his wife, Anna, that the chest had been made for his great-great-grandfather Joshua Hadley.[16]

Two other high chests with arched upper drawers are known, but neither has a history. The first (fig. 31) is nearly identical in form to the Hadley chest, but its central upper drawer is decorated solely with the sulfur-inlaid date “1802” (fig. 32), and all of its other drawers are outlined with light-wood stringing. The other high chest (fig. 33) has a simpler cornice molding (fig. 34) and no inlay.[17]

Two high chests with rectangular upper drawers are also part of the early Cane Creek group. The example illustrated in figure 35 has an atypical cornice molding composed of a large astragal with a cove below (fig. 36). The other chest has a typical cornice—large cyma element with astragals above and below—but the elements are slightly compressed. That example also has three large drawers rather than the usual four.

Like their counterparts in southeastern Pennsylvania, cabinetmakers in the Cane Creek community made miniature chests, which were most likely for children. Two virtually identical examples are known, and both have straight bracket feet; exposed, wedged dovetails; and cusp and cyma shaping like that on the feet of full-sized chests (fig. 37). Although the miniature chests do not have early histories, they were collected within ten miles of Cane Creek Meeting House.[18]

The most common furniture form from the early Cane Creek group is the lidded chest. Of the six known examples, five have two drawers at the bottom and one has none. All of the chests with drawers have straight bracket feet with cusp and cyma shaping, either sulfur or sulfur-and-wood inlay in typical Cane Creek designs, an astragal molding separating the drawers from the chest, and an interior till, three with hidden compartments. Large rose-head nails secure the chest bottom to the sides, front, and back. The construction of the lids on the chests varies. The two chests that are probably the earliest have two-board lids with ovolo-molded edges and battens secured with wooden pins (fig. 40). The example illustrated in figure 38 has an inlaid wooden band outlining the drawers and the sulfur-inlaid initials “SS” separated by a five-pointed star inside the typical rectangular panel with astragal ends. It is the only piece, however, with a wooden-inlaid diamond surrounding this particular sulfur design (fig. 39). The other example is the plainest of all the chests, with no drawers and the sulfur-inlaid initials “jC” separated by a star and enclosed in a wooden-inlaid diamond. Neither of these chests has a family history.[19]

The remaining four chests have lids composed of two boards with moldings pinned to the front and sides (fig. 43) and a bead on the top back edge (fig. 44). None has wood inlay. The example illustrated in figure 41 has the inlaid initials “ET,” but the identity of its original owner is not known (fig. 42). This chest descended in the family of John Allen (1749–1826) and his wife, Rachel Stout Allen (1761–ca. 1840), builders of the log house illustrated in figure 2. John went to North Carolina with his family circa 1762, when his mother, Phebe, presented a certificate of removal from New Garden Monthly Meeting in Chester County, Pennsylvania, to the Cane Creek Meeting. In 1779 he married Rachel Stout, daughter of Peter and Margaret Stout, who had moved from York County, Pennsylvania, also in 1762. Although John and Rachel were both dismissed from Cane Creek Meeting for marrying out of unity, in 1781 they were condemned for their “misconduct” and taken back into the fold. Eight of their thirteen children’s births were recorded in the minutes of Cane Creek Monthly Meeting between 1780 and 1794.[20]

Fortunately, many of John Allen’s estate papers and his store account book survive, giving scholars a glimpse into what life was like in the Cane Creek Settlement from circa 1775 to 1826. John appears to have operated a small store from the shed addition of his home and provided a variety of services for his neighbors, including making doors, laying floors, sawing and riving boards, mending stills, and making a small amount of furniture: coffins, a cradle, a “cubert,” and a press. He also was a schoolmaster for many of the children in the region. In addition to being a wife and mother, Rachel appears to have acted as the local physician, dispensing a variety of medicines for various ailments. When John died in 1826, “2 chists” were listed as having been willed to Rachel, but it is impossible to determine if the ET chest was one of them. The only known family member with the initials “ET” was Elizabeth Thomas, wife of Rachel’s uncle Samuel Stout. Even though Samuel Stout lived roughly fifteen miles southwest in Randolph County and does not appear in the Quaker records (not to be confused with Rachel’s brother Samuel who lived nearby and was a member of Cane Creek Meeting), John Allen was an executor of his will, so the two families must have been close. The letters “Th” in script, written with what appears to be a brown stain, are on the side of one drawer of the chest. It is possible that they refer to the surname “Thomas” and are shop inscriptions used to identify Thomas family ownership. Japanners often inscribed the names of clients on their pieces to keep them from being confused with work for others. When the Allens acquired the chest is not known. Miss Beulah Oyama Allen, the great-great-granddaughter of John and Rachel Allen, donated the ET chest to the Allen House Museum in 1965. She maintained that the chest was original to the house.[21]

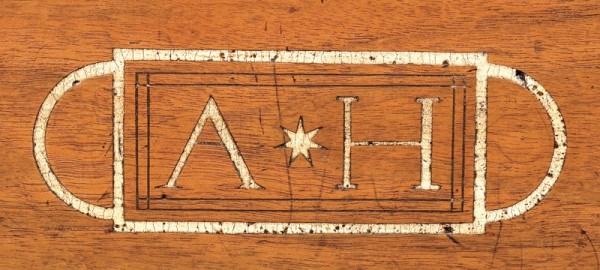

A nearly identical chest with drawers is decorated with the sulfur-inlaid initials “SF,” and a very similar example is marked “AH” (fig. 45). On the latter chest, delicate inlet lines, from which nearly all of the sulfur is missing, frame the initials (fig. 46). Those lines were probably cut with a chisel, knife, or marking gauge and are unusually shallow for sulfur-inlaid work, but they appear on several pieces in the Cane Creek group. The AH chest was collected about fifteen miles southwest of Cane Creek Meeting. It has a history of ownership in the Hadley family (as does the high chest in figure 28), but its original owner and line of descent are not known. Another closely related chest also has fine, sulfur-inlaid lines framing the initials “AW” and date “1800” (figs. 47, 48). The design of the sulfur inlay is very similar to that on the LH clock (fig. 10).[22]

The craftsmen most likely to have made the Cane Creek furniture are Joseph Wells Jr. (1729–1804) and male members of his immediate family. He owned a sawmill approximately one mile west of Cane Creek Meeting House, and his 1804 estate inventory listed various sorts of lumber, a glue pot, a horse shave, “one peace of brass,” a workbench, a “Case of Drawers part made,” and “joiner’s tools.” Among the tools were seventeen planes, three handsaws, two gouges, two pairs of compasses, a turning lathe, three hammers, a cutting box, two axes, a drawing knife, a miter box, seven files, three bits, a square, a joiner’s screw, a vice, a jointer, a chisel, a hatchet, and a compass saw. Wells also had more furniture than typically found in the inventories of other Cane Creek residents: a desk, two chests of drawers, four chests, an oval table, a looking glass, a knife box, a “box and bottles,” one armchair, seven side chairs, and one eight-day clock valued at £7.10.7, an unusually high amount.[23]

Wells was reputed to have been born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, but moved south with his family to Prince George’s County, Maryland, by 1743. His parents were Joseph Wells Sr. (1697–ca. 1752) and Margaret Swanson Wells (1693–ca. 1752). They called their Maryland tract Boiling Springs, and they were active members of Monocacy Meeting while living there. By 1746 Joseph and Margaret had become members of Fairfax Monthly Meeting in Loudoun County, Virginia, and it was here that Joseph Jr. married Charity Carrington (ca. 1730–1803) in 1750. Joseph Jr. and his new bride arrived at the Cane Creek Settlement a month later, placing them among the earliest settlers in the region. They were charter members of Cane Creek Meeting when it was established in 1751 and appear in the meeting minutes until their deaths. Over the next fifty years, Joseph and Charity acquired hundreds of acres along Cane Creek and its tributaries. One of those tracts was purchased in 1799 from Thomas Dixon, the clockmaker. The couple raised five daughters and six sons, and documentary evidence suggests that their boys Jesse (1762–1794) and William (1766–1851) were also woodworkers. When Jesse died in 1794, his estate inventory included “sundrie Joyners tools,” a table frame, and a workbench. In his will, Joseph Wells Jr. left William “all my tracts of land on both sides of Cane Creek, and my part of the [saw]mill seat and water courses.” In addition, at his father’s estate sale, William purchased more of his father’s woodworking tools than any other person. Joseph’s sons Isaac, John, and Nathan, and Joseph’s son-in-law James McDaniel also purchased enough tools to suggest that they, too, were probably involved in the family woodworking business.[24]

The Wells family’s connections to owners of furniture in the Cane Creek group support the theory that Joseph Jr. and his sons were the principal makers. The first piece of property George Foust, the owner of the chest illustrated in figure 21, bought in 1778 was contiguous to Joseph Wells’s property, leading one to assume that Joseph, his wife, and the Fousts raised their families in the same neighborhood. George Foust’s youngest brothers, Peter and Daniel, were also acquainted with Wells and purchased items from his estate sale in 1804. Joshua and Ruth Hadley, the owners of the jH high chest (fig. 28), were early members of Cane Creek Meeting, along with Joseph and Charity Wells, and lived about three miles from them. John and Rachel Allen, owners of the ET chest, attended the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting during the same period and lived less than two miles from the Wells family. In 1781 Allen sold Joseph Wells 2 1/2 bushels of rye and credited him for “170 feet of oak Boards . . . and 150 feet of poplar.” Given the limited number of furniture makers in the area, no other members of the Cane Creek Settlement emerge as better candidates for the makers of this early furniture than Joseph Wells Jr. and the male members of his family.[25]

Transitional Furniture

Two high chests and a dish dresser represent the work of a related but slightly later shop tradition. None of these objects has sulfur inlay. The first of the two high chests (fig. 49) has an astragal and cyma cornice molding very similar to that on the Foust, Hadley, and 1802 high chests (figs. 21, 28, and 31), but the drilled dentil element below is unique (fig. 50). The central drawer in the upper tier is wider than the flanking drawers, rather than being equal-sized like those on high chests from the early group, and the front edges of the case are beaded. Another significant departure can be noted in the shape of the feet. Those on the chest illustrated in figure 49 are more slender than feet from the early group, and they have an unusually wide arch that descends into a straight, pointed cusp (fig. 51).[26]

The second high chest has three arched upper drawers, but, again, the middle one is slightly wider than the drawers on either side (fig. 52). Its unusually robust cornice molding is composed of an astragal, a series of fillets, a cove, and another series of fillets, above a frieze with dentil-and-dot inlay (fig. 53). The latter element echoes the drilled dentil frieze on the preceding high chest (fig. 50). The chest illustrated in figure 52 has a molded bead on the front edges of the case and feet that differ from those on the chest in figure 49 only in having inlaid stringing at the bottom (fig. 54). That stringing is reminiscent of the molded bead on straight bracket feet in the early group.[27]

The high chest illustrated in figure 52 descended in the family of Roy Alton Cox, whose great-great-great-grandparents were Charles (1762–1840) and Amy (Barker) Cox (1764–1839), both members of Cane Creek Meeting. Amy’s uncle was John Allen, owner of the ET chest (fig. 41). Allen’s sister Hannah (1741–1834) married Amy’s father, Nicholas (1737–1826), in 1764. Nicholas Barker was not a Quaker at that time, as indicated by the minutes of Cane Creek Monthly Meeting, which reported that Hannah wed out of unity. Apparently the couple raised their daughter in the Quaker faith, however. By 1818 Amy and Charles were described as elders of the Holly Springs Meeting, located about twenty-five miles southwest in Randolph County. They worshipped at that meeting until their deaths and were buried in the Holly Springs cemetery. Amy and Charles’s residence in Randolph County may explain why the chest was found there rather than in Chatham or Alamance County.[28]

The dish dresser illustrated in figure 55 is the only extant example of that form from the Cane Creek area, but local inventories occasionally listed such objects, and one mentions a “pair of dressers.” A significant connection between this dish dresser and furniture from the early group is the use of decorative wooden pins (figs. 12, 17), which accentuate the vine-and-husk inlay on the cornice frieze (fig. 56). The cornice relates most closely to that on the Cox family high chest, particularly in its use of large astragal and cove elements as well as filetted bands (figs. 53, 57). The feet of the dresser have a wide arch and their replaced cusps (fig. 58) probably resembled those on the chests illustrated in figures 49 and 52.[29]

Furniture Made Between 1800 and 1835

Another group of furniture from the Cane Creek area also has bracket feet with wide arches and variations of the straight, pointed cusp. Among the known examples are a chest with two drawers and several high chests. The feet of the chest illustrated in figure 59 have unusually narrow cusps that point straight down (fig. 60). Unlike earlier chests from the Cane Creek group, the lid on this piece has battens attached with four through tenons (fig. 61) and a beefy applied molding nailed to the front. One of the most unusual features is the removable bottom of the chest compartment (fig. 62). On most chests, that board is permanently attached. The underside of that board is signed in white chalk, “Joseph Cloud, his hand and pen, 1800.” Two drawer sides are also signed in white chalk, but with the name “Jeremiah Piggott.”[30]

The related high chests appear to have been made a few years later. Of the two nearly identical examples (figs. 63, 66), the one illustrated in figure 63 bears the white chalk inscription “John Piggot” on the underside of the top boards. Both have beaded case sides, cornices composed of an astragal element surmounting a cove with a tiny ovolo and fillet below (fig. 64), and unusually tall, narrow feet (fig. 65). A third chest (fig. 67) has even taller feet (fig. 68) and an additional cornice element: a wavy molding that comes to a point in the center front. A fourth similar example has slightly wider feet and two hidden drawers that slide in directly below the chest top from the back; the very narrow, uppermost horizontal backboard must be removed before the drawers can be accessed. This high chest has a strong family history indicating it was made for Cane Creek Quaker Hugh Woody (1770–1825), who married Ruth Hadley (1773–1810), the daughter of Joshua and Ruth Hadley, owners of the high chest illustrated in figure 28.[31]

The families of the men who signed the chest illustrated in figure 59—Jeremiah Piggott and Joseph Cloud—had been residents of the Cane Creek Settlement almost from its beginning. Siblings William (1726–1770), Jeremiah (1730–1778), Benjamin (1732–1818), and Margery (1736–1828) Piggott came from Cecil County, Maryland, where they had been members of East Nottingham Monthly Meeting. William arrived in North Carolina by 1751, followed by Jeremiah in 1752, Margery in 1753, and Benjamin in 1754. William ran a tannery, Jeremiah was a saddler, and Benjamin appears to have been a farmer. Margery married Joseph Buckingham in 1754. The Piggott families who lived on Cane Creek tended to have many children and used the same names, but the Jeremiah Piggott who signed the chest was undoubtedly the son and namesake of the Jeremiah who arrived in 1752.When Jeremiah Jr. (1773–1825) died, his estate inventory included thirty-seven planes, a set of turning tools, six augers, a glue pot, fourteen chisels, three drawing knives, five gouges, three drawer locks, two lots of hinges, a workbench, walnut plank, one set of table legs, and one “clock case timber,” among other cabinetmaking-related items.[32]

The design of the chest illustrated in figure 59 and Jeremiah Jr.’s birth date indicate that he served his apprenticeship in the Cane Creek community. By the time he was five years old, both his mother and father were dead (Rachel [Mayner] Piggott, d. 1773; Jeremiah Sr., d. 1778). Jeremiah Sr.’s will named his “trusty friends” Benjamin Piggott and John Piggott as executors. Benjamin was Jeremiah Sr.’s younger brother, and John was his nephew, the son of his older deceased brother, William. Jeremiah Sr. left Jeremiah Jr. a tract of land lying at the headwaters of Cane Creek in Chatham County. That parcel was in the extreme northwestern part of the county on the southern side of the creek, approximately two miles southwest of Cane Creek Meeting House. Jeremiah Sr. also requested that his executors “bind out my sons to trade if it can be come at among friends [Quakers].” Joseph Wells Jr. and his sons are the craftsmen most likely to have trained Jeremiah Jr. Wells and Jeremiah Piggott Sr. were both early members of Cane Creek Meeting, and in 1764 the two men, along with Piggott’s brother William, served as executors of the estate of Quaker Joel Brooks, who requested their aid in freeing his “Negro Major.” John Piggott, who was responsible for arranging Jeremiah Jr.’s apprenticeship, owned land adjoining that of Joseph Wells Jr. in 1794 and 1799. Jeremiah Piggott Jr. purchased “sundrie Joiner’s tools” at the 1794 estate sale of Joseph Wells Jr.’s son Jesse. Almost all of the other buyers were the sons and sons-in-law of Joseph Wells Jr. Jeremiah Jr. would have been twenty-one in 1794, close to completing his apprenticeship and possibly working as a journeyman in a Wells shop. In 1800 he married Sarah Hadley (1762–1827), whose parents Joshua and Ruth owned the jH high chest (fig. 28). Jeremiah Jr. was listed as a resident of Chatham County in the 1800 census and by then was probably operating his own cabinetmaking establishment. Four years later, he purchased one plane, six files, and some plank at Joseph Wells Jr.’s estate sale.[33]

The chests and dish dresser illustrated in figures 49, 52, and 55 could have been made in either a Wells or a Piggott shop, and Jeremiah Jr. must be considered as a possible maker of the 1802 high chest (fig. 31). His 1825 estate sale listed “brimstone,” the period term for sulfur. Jeremiah Jr. and Sarah had three sons—Jeremiah (1801–1880), Jonathan (1802–1833), and David (1807–1834). The 1833 and 1834 estate inventories of Jonathan and David listed numerous woodworking tools, suggesting that they, too, were cabinetmakers and likely trained with their father.[34]

Assigning later Cane Creek furniture to specific shops is problematic because Jeremiah Piggott Jr. likely trained with Joseph Wells Jr., and at least one journeyman—Joshua Buckingham—may have been involved in the production of furniture in both the Wells and Piggott shops. Joseph Buckingham (ca. 1726–1795), who had been a member of Newark Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania, married Margery Piggott, Jeremiah Jr.’s aunt, at Cane Creek in 1754. Other members of Buckingham’s family also went to North Carolina. His nephew Joshua (1769–1853) was received into Cane Creek Monthly Meeting on certificate from Wilmington Monthly Meeting, Delaware, in 1792, and married Rachel Piggott, sister of Jeremiah Piggott Jr., in 1793. Joshua’s father, James, was a joiner whose will was probated in New Castle County, Delaware, that same year. Unfortunately, no furniture made by James Buckingham is known, but it appears that his son followed him in the cabinetmaking trade. Joshua purchased a glue pot at Joseph Wells Jr.’s estate sale. Joshua’s family was listed in the 1820 Orange County census, and one member in the household was identified as being engaged in manufactures. The latter was probably Joshua, since the only other male in the household was fifteen years old or younger. In 1823 Joshua Buckingham and his family moved to Indiana, where Rachel and the children received a certificate to Lick Creek Monthly Meeting. He died in Indiana in 1853, and his estate sale included a variety of woodworking tools—chisels, handsaws, a circular saw, jointers, planes—and a glue pot, possibly the same one he purchased from Joseph Wells Jr.’s estate sale.[35]

When Joshua Buckingham joined the Cane Creek Settlement in 1792, he was twenty-three years old and presumably already trained by his father. Exactly how this newcomer interacted with and influenced the Wells and Piggott shops can only be speculated. When Buckingham first arrived, he probably worked with Joseph Wells and his sons, along with his future brother-in-law, who, at the time, would have been serving his apprenticeship in the Wells shop. With his more urban training, he could have influenced the design and construction of the clock illustrated in figure 15. Its shaped base panel, shaped waist door, and disengaged hood columns make it the most sophisticated of all the clocks to have survived from the region. He also might have had a hand in designing and making the dish dresser (fig. 55). It is so reminiscent of Pennsylvania examples that for many years it was considered to be from that state by the museum that owns it.

The second signature on the chest in figure 59 is that of Joseph Cloud. His family arrived in the Cane Creek area from Chester County, Pennsylvania, circa 1764. The births of the children of Joseph Cloud Sr. and his wife, Mary Underwood Cloud, are all recorded in the minutes of Cane Creek Monthly Meeting, including Joseph Cloud Jr., born in 1775. The original Cloud property was just west of the Chatham County line in Randolph County on Rocky River. Joseph Sr., a “traveling minister” who visited South Carolina, Georgia, and Ohio, is unlikely to have been the man who signed the chest. His wife Mary died in 1789, and the following year, he received a certificate to Center Monthly Meeting, twenty-five miles due west, in Guilford County, North Carolina. There he married Hannah Beals. His son Joseph Jr. would have been fifteen in 1790. Since apprenticeships often began at the age of fourteen, it is possible that the younger Cloud remained in the Cane Creek area to complete his term and that he trained in the same shop as Jeremiah Piggott Jr., who was only two years older. Approximately ten years later, when they both signed the chest, one can assume they were working together in Jeremiah’s shop. In the 1800 Chatham County census, twenty-seven-year-old Jeremiah Piggott’s household included one free white male, aged sixteen to twenty-five, and that person was most likely Joseph Cloud Jr.[36]

Determining which John Piggott signed the high chest illustrated in figure 63 has proven much more difficult because at least four John Piggotts of approximately the same age lived in the region when the high chest was made. The John Piggott who was named an executor of Jeremiah Piggott Sr.’s estate does not appear to have had any connection to woodworking and can be excluded. However, his son and namesake (1780–1817) might have worked with Jeremiah and been the signer. The signature could even be the shortened name of Jeremiah Jr.’s son Jonathan, a documented cabinetmaker. Suffice it to say that the John who signed the high chest was related to Jeremiah Piggott Jr. and his family and worked with them at some point. What is most important about the signature is that it strengthens the connection between the Piggott shop and the tall, narrow bracket foot with the wide arch and straight, pointed spur.[37]

Five tall case clocks with scroll moldings and a central plinth block related to those from the early Cane Creek group might also be products of the later Piggott shop. The clock illustrated in figure 69 is typical. It descended in the Ward family, some of whom were members of Cane Creek Monthly Meeting, and was found in a home located about seven miles south of Jeremiah Piggott Jr.’s property. Other than its pediment (fig. 70), the most distinctive detail of the clock case is its foot—an applied bracket with two rounded spurs (fig. 71). Another of the five clocks (fig. 72) descended in the family of John and Rachel Allen, owners of the ET chest (fig. 41). At John’s 1826 estate sale, Rachel purchased the clock for $17.75. Since Jeremiah Piggott Jr.’s 1825 estate inventory included one “clock mettal,” “l wooden clock,” and “1 clock case timber,” he and his workmen must be considered as possible makers of the five related cases, despite the fact that the foot profiles of those objects differ significantly from those associated with the Piggott shop. Regardless of who made these cases, Thomas Dixon almost certainly made or sold their movements. His daughter Elizabeth Dixon married John and Rachel Allen’s son Peter, and his daughter Hanna married the Allens’ son Solomon.[38]

Sulfur-Inlaid Chests on the Periphery of the Cane Creek Group

Three chests that share design features with furniture from the Cane Creek group were probably made in nearby Guilford or Randolph County. The earliest is dated 1794 (fig. 73) and the latest 1807. All have sulfur-inlaid initials and dates separated by a star and enclosed in a rectangular panel with astragal ends, but the letters and numbers occur in one long row and are not as precise as those on Cane Creek examples (fig. 74). Two of the chests have two sets of initials separated by dots and the letter “B” adjacent to their dates, presumably designating “birth.” The feet on the chests also differ from those on Cane Creek examples, in having a simpler inner profile without a cusp and coved glue blocks that extend through the bottom (figs. 75-77). The lids have pinned-on moldings on the front and sides and through dovetails at the front corners, a very unusual construction detail found nowhere else in the region (fig. 78). The 1794 chest reputedly descended in the Parrish family, who lived near Pleasant Garden in southern Guilford County, North Carolina. The chest dated 1802 has a vague history of having come out of the John and Rachel Allen family, but no children or grandchildren with the initials “N.A.” were born in that year (figs. 79-81).[39]

The latest chest decorated with sulfur inlay reading “E. S. B. 1807 J. * L. + 15” was collected in the small town of Sophia in north-central Randolph County, North Carolina, and was part of the Floyd Lewis Hayes estate. According to family genealogists, Hayes was the great-great-great-grandson of John Matthew Kivett (ca. 1755–1843), brother of Henry Kivett (1760–1806), Jacob Kivett (d. 1810), and Barbara Kivett Foust, whose high chest is illustrated in figure 21. Henry Kivett’s 1806 estate inventory listed “200 feet of walnut plank,” “a chest lock,” and a small number of saws, augers, chisels, and planes, items that suggest he may have been a woodworker. Similarly, Jacob Kivett’s 1810 estate inventory listed two jointers, three planes, three augers, three drawing knives, two chisels, one pair of door hinges, and one set of table legs. Jacob and Henry owned adjoining tracts in western Randolph County on Mount Pleasant Creek and might have worked together in the same shop. The connection of the 1807 chest to the Kivett family may point to this group having been made by the Kivett brothers. Henry’s death in 1806 precludes him from making the 1807 chest, but Jacob, or any other men working with the brothers, could have continued the tradition. The Kivetts were also connected to John and Rachel Allen. When Rachel’s uncle Samuel Stout died, her husband John was the executor of Samuel’s estate, and he paid Henry Kivett for making the coffin and Jacob Kivett for helping settle the estate.[40]

Transfer and Melding of Styles

Approximately 60 percent of the founding members of Cane Creek Meeting emigrated from southeastern Pennsylvania, 11 percent from northern Maryland, and 11 percent from northern Virginia. Sixty-five percent of the Pennsylvania migrants came directly from Chester County. These settlers brought with them memories of slat-back armchairs, dish dressers, chests, and chests of drawers they had seen or owned, and in some instances they may have brought the furniture itself. The miniature chest with arched drawers illustrated in figure 82 was made in 1746 probably by cabinetmaker Moses Pyle for his daughter Hannah, who married Henry Piggott in 1760 at London Grove Meeting in Chester County. Although that couple remained in Pennsylvania, the chest represents the type of object that might have been taken to the Cane Creek area by a relative (Henry’s uncles William, Jeremiah, Benjamin, and aunt Margery were founding members of the Cane Creek Meeting) and influenced local styles. The same can be said of another chest made for the sister of Pyle’s first wife, Mary Darlington (fig. 83). That object is decorated with the initials “HD,” for Hannah Darlington, and the date “1747” enclosed in inlaid adjoining rectangles, similar to the sulfur-inlaid lines enclosing the initials “LH” and date “1799” on the clock illustrated in figure 10 and the “AW” and “1800” on the chest illustrated in figure 47.[41]

A settler of Germanic descent almost certainly introduced the technique of sulfur inlay to the Cane Creek community. The earliest Pennsylvania furniture with sulfur inlay is from Lancaster County, where Rachel Allen’s father lived briefly before moving to North Carolina in 1762; however, the use of that decorative technique spread to other areas of Pennsylvania. Southern Alamance County had a large population of Germans who settled along Stinking Quarter and Little Alamance Creeks, and any of them could have been familiar with sulfur inlays. Sulfur was available in the Cane Creek area, as indicated by the brimstone listed in Jeremiah Piggott Jr.’s estate inventory. Philip Snotherly, father of the two sisters who married George Foust’s two youngest brothers, Daniel and Peter, also had sulfur listed in his estate inventory. Why Quaker cabinetmakers adopted this Germanic technique is not known, but it is a perfect example of how the melding of cultures in the North Carolina backcountry is manifest in the region’s material culture.[42]

Although only two pieces of furniture from the Cane Creek Settlement are signed, the histories of the objects illustrated and discussed in this article, as well as biographical and genealogical information pertaining to local woodworkers, allow us to draw conclusions about cabinetmaking there. What seems probable is that the following craftsmen produced the majority of pieces that have surfaced in the Cane Creek region: Joseph Wells Jr. and his sons Jesse and William, and possibly his sons John, Isaac, Nathan and son-in-law James McDaniel; Jeremiah Piggott Jr. and his sons Jonathan and David, brother-in-law Joshua Buckingham, and relative John Piggott; and Joseph Cloud Jr. The Kivett brothers Henry and Jacob may have been influenced by sulfur-inlaid pieces made in the region. Thomas Dixon and possibly Joseph Pyle emerge as the most likely providers of movements for locally made clock cases. Because no apprenticeship indentures exist, exactly how many shops were involved, who trained with whom and when, and which pieces were made in which shops can, in most cases, only be surmised.

The investigation of furniture production and use in the Cane Creek Settlement also allows one to draw other conclusions about the Carolina backcountry. Early settlers went to the region in groups that shared a geographic, ethnic, and religious heritage, and part of that heritage was remembered furniture forms and styles that were then replicated in their new home. The cabinetmaking trade was primarily a family business, often including fathers, sons, and sons-in-law as craftsmen in a particular shop. If an individual apprenticed to someone who was not a family member, his master would most likely be of the same ethnic and religious background. Because settlement patterns sometimes resulted in people of one ethnic background living close to people of another, objects sometimes reflect a creative synthesis of styles from both cultures. A cabinetmaker’s customer base typically lived within approximately ten miles of his shop. Although most craftsmen married and attended church services with those of a similar ethnic background, they were very practical when conducting business and would interact with all of their neighbors, regardless of ethnicity. Of course, as with all generalities, these do not apply in every instance, but they do represent what appears to be true for the majority of cabinetmakers and consumers in the Cane Creek Settlement, an area with a rich furniture-making tradition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks John Allen, historian of Cane Creek Meeting, and the staff of Alamance Battleground Historic Site.

The term “Cane Creek Settlement” was found in a deed of sale from Daniel Foust to John McDaniel, January 20, 1790, Orange County Wills, 1787–1795, vol. B, p. 81, North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735–1970, accessed January 29, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1951-20308-22054-43?cc=1867501&wc=10922976. Michele Vacca and Benjamin Briggs, History of Alamance County: Alamance County Architectural Survey Update, 1670–1945, p. 4, accessed January 29, 2014, http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCkQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.hpo.ncdcr.gov%2Fsurveyreports%2FAlamanceCountySurveyUpdate%28Historic%2520Contexts%29-2002.pdf&ei=JibpUrvNOMTnkAebgIHADw&usg=AFQjCNEpUvpoT7wmy_HKT4kn1QQXrSRSYg&sig2=PMG83XNCZEKFlWxCRWIoQA&bvm=bv.60157871,d.eW0). David Leroy Corbitt, The Formation of the North Carolina Counties, 1663–1943 (Raleigh, N.C.: Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1987), pp. 1, 61. John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina, edited by Hugh Talmage Lefler (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967), pp. 60–61.

Bobbie T. Teague, Cane Creek: Mother of Meetings (Greensboro, N.C.: Friendly Desktop Publishing, 1995), pp. 10–11. An overview of the settlement of Alamance County can be found in Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), pp. 239–54.

The earliest recorded birth at Cane Creek Meeting was that of Thomas Brown on October 28, 1749, as noted in William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 6 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1978), 1: 347. Seth B. Hinshaw, The Carolina Quaker Experience, 1665–1985 (Dexter, Mich.: Thomas Shore, 1984), pp. 24–26. Information on the Allen House and family can be found at North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, Office of Archives & History: North Carolina Historic Sites, accessed January 29, 2014, http://www.nchistoricsites.org/alamance/allhou.htm. The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) Research Center (MRC) has a microfilm copy of the John Allen Family Papers: John Allen Collection 1756–1877, NC.M MFm.23, original at North Carolina Department of Archives, Raleigh.

Information on the Battle of Alamance can be found at North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, Office of Archives & History: North Carolina Historic Sites, accessed January 29, 2014, http://www.nchistoricsites.org/alamance/.

George Troxler, Pyle’s Massacre (Burlington, N.C.: Alamance County Historical Association, 1973). Thomas Baker, Another Such Victory: The Story of the American Defeat at Guilford Courthouse That Helped Win the War for Independence, 2nd. ed. (Fort Washington, Pa.: Eastern National, 2005). Algie I. Newlin, The Battle of Lindley’s Mill (Greensboro: North Carolina Friends Historical Society, 1975).

MESDA Research File (MRF) S-11093. Mr. and Mrs. L. S. Hornaday, Jr., Piedmont North Carolina Cemeteries, vol. 1, Cane Creek Friends Meeting (1981; reprint, Burlington, N.C.: L. S. Hornaday, 2001), p. 52. Lewis Hornaday’s grave is in Cane Creek Meeting Cemetery, Row E, grave 8. Les Lindley’s website, “History of Lindley, Councilman, and Associated Families,” accessed January 29, 2014, http://woodlin.net/lindley/888.htm. Simon Hornaday was buried at Bethel United Methodist Church Cemetery near Graham, North Carolina. His wife’s and parents’ names are listed at “Find a Grave,” accessed January 29, 2014, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=32856202. Simon’s daughter Ruth Hornaday Lowe was also buried at Bethel United Methodist Church Cemetery. Her parents’ and husband’s names are listed at “Find a Grave,” accessed January 29, 2014, http://www.findagrave.com/cgibin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=32907781. In the 1850 census, Miley Lowe, age four, was listed in the same household as her grandfather, eighty-five-year-old Simon Hornaday, in the southern district of Alamance County. Her mother, forty-seven-year-old Ruth Lowe, was listed in the household next door (“1850 Alamance County, N.C., Census,” Ancestry.com).

Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725–1850 (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 2011), pp. 62–64. Greensboro Historical Museum, Greensboro, N.C., accession file 1952.023.0001. Thomas C. Dixon, “Genealogy of the Dixon Family on Cane Creek in the Counties of Alamance and Chatham, State of North Carolina: Collected from Old Family Records and Traditions as Far Back as Five Generations,” as quoted in Steven R. Shook, “Silverdale/Shook Genealogy,” accessed January 29, 2014, http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=shook&id=I9027. MESDA accession file 4492.

Lisa Minardi, “Sulfur Inlay in Pennsylvania German Furniture: New Discoveries,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2015), pp. 86–199. Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern, & People, pp. 80–86.

MRF S-14570. Administrator of J. George Hannah Sr. vs. Harry B. Hannah, Chatham County Superior Court, October term, 1916, North Carolina, Estate Files, 1663–1979, image 13, accessed January 29, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1951-21379-13956-26?cc=1911121&wc=M9W7-BXB:2075578507. Chatham Record, July 31, 1890, accessed January 29, 2014, http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/newschatham/id/2087/rec/1.

MRF NN-362. Lewis Hornaday was the brother of Simon Hornaday, whose family owned the table illustrated in figure 3. Lewis owned property very near Cane Creek, became a member of Cane Creek Monthly Meeting in 1819, was buried in Cane Creek Meeting Cemetery in 1837. In addition, his daughter Ruth married Joseph Wells, the son of William Wells, who was the son of Joseph Wells Jr., the probable cabinetmaker of this group. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:399. Les Lindley, “History of Lindley, Councilman, and Associated Families,” accessed January 30, 2014, http://woodlin.net/lindley/900.htm. Lewis was one of only two men with the initials “LH” in the 1800 Orange County, North Carolina, census. Further, his estate inventory suggests he was a man of means and could have afforded a clock like the example illustrated in figure 10. Lewis Hornaday Will, signed August 25, 1837, Orange County Wills, 1822–1838, vol. E, pp. 217–19, North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735–1970, accessed January 30, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/DGS-004770553_00221?cc=1867501&wc=10922979. Although no clock was mentioned in Hornaday’s will, he left his wife Dinah (Battick) “all my household furniture.” “Account of the Sale of. . . the Estate of Lewis Hornaday,” “9th Month the 19th 1837,” Orange County Inventories, 1837–1843, pp. 86–87, North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735–1970, accessed January 30, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/DGS-004770558_00071?cc=1867501&wc=10922631.

MRF NN-2482.

Chatham County, North Carolina Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions Minutes, August 1792, p. 209, accessed June 28, 2016, http://www.ncgenweb.us/chatham/chatct92.htm. Samuel Pyle Will, signed August 13, 1801, Orange County Wills, 1800–1822, vol. D, pp. 73–74, North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735–1970, accessed January 30, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/DGS-004770552_00490?cc=1867501&wc=10922978.

Hornaday, Piedmont Cemeteries, p. 65. T. C. Dixon as quoted in Shook, “Silverdale/Shook.” A. B. Pruitt, Abstracts of Land Entries: Orange Co., NC, 1778–1795 (N.p.: A. B. Pruitt, 1990), p. 100. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1: 351, 386. Marilyn Poe Laird and Vivian Poe Jackson, Chatham County North Carolina Deeds, 1783–1788 (N.p.: Poe Publishers, n.d.), pp. 6, 49. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 11, Deed Books 6 & 7 (Raleigh, N.C.: privately published, 1993), p. 27. “An Inventory of the Personal Estate of Simon Dixon, 1782, Chatham County, D., n.p., North Carolina, Estate Files, 1663–1979, accessed January 30, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1942-21405-57797-81?cc=1911121&wc=M9W7-TC3:443294074. As a cost comparison, Simon Dixon’s estate inventory lists his desk as valued at £4 and his case of drawers at £5.

Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, pp. 76–79. MRF S-15061; MESDA accession file 5568.

Dr. Howard M. Faust, Faust-Foust Family in Germany & America (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 1984), pp. D152–54. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 4, Deed Book 4, Abstracts (Raleigh, N.C., 1990), p. 48. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1: 364–65. John Foust Will, signed January 20, 1790, Orange County Wills, 1787–1795, vol. B., pp. 79–81, North Carolina, Probate Records, 1735–1970, accessed January 31, 2014, https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1951-20308-22265-90?cc=1867501&wc=10922976. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1: 360, 411. N. C. Secretary of State, Transcripts of the Entry Takers Book for the County of Orange, Recd. 29th of Novr. 1798, # 680, North Carolina Department of Archives and History. Faust, Faust-Foust Family, pp. D251–252. S. W. Stockard, The History of Alamance (Raleigh, N.C.: Capital Printing, 1900), pp. 8–9. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 4, Deed Book 4, p. 29. 1830 U.S. Census, Orange County, N.C., p. 252, NARA Series: M19; Roll Number 123, Family History Film 0018089. George William Welker, History of German Reformed Church in North Carolina, p. 737, accessed February 1, 2014, http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr08-0371. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 4, Deed Book 4, pp. 29–30, 127, 129. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 8, Deed Book 5, Abstracts, (Raleigh, N.C., 1991), p. 63. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 11, Deed Books 6 & 7, pp. 26, 83. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 12, Deed Books 8 & 9, (Raleigh, N.C., 1993), p. 10. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 14, Deed Books Ten & Eleven (Raleigh, N.C., 1994), pp. 6–7, 10, 112. William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 19, Deed Books 15 & 16 (Raleigh, N.C., 1997), p. 10. At Quaker William Lindley’s estate sale in 1784, George Foust bought a grindstone (William D. Bennett, ed., Orange County Records, vol. 13, Inventories & Accounts of Sales, 1758–1785 [Raleigh, N.C., 1994], p. 203). A legal document proving Daniel Foust’s desire that his slaves be freed after his wife’s death can be found in his loose estate papers: “North Carolina Estate Files, 1663–1979,” database with images, FamilySearch, accessed May 21, 2014, (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1951-35515-3093-7?cc=1911121, Orange County > F > Foust, Daniel (1827) > image 4 of 29; State Archives, Raleigh.