Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1888. Terracotta. H. 34 1/2". (Photographs by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted. ) The Oluf Thulesen marker is made from a single piece of unglazed red terracotta. It is decorated with carefully sculpted oak boughs, complete with acorns. The marker is located in Alpine Cemetery, Perth Amboy.

Detail of the oak boughs on the gravemarker illustrated in figure 1. The tree of life cut down was a common Victorian gravemarker design. This snapped twig conveys the same idea, a life cut short. Oluf Thulesen was only eighteen when he died.

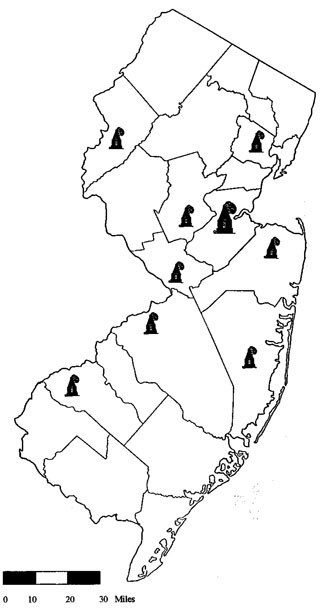

The kilns on this map show the approximate location of New Jersey’s major terracotta manufacturers. (Courtesy, IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology.) The Raritan Formation of Cretaceous clays runs transversely across New Jersey from northeast to southwest.

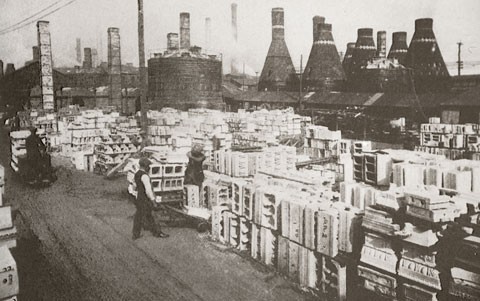

Photograph of the Atlantic Terracotta Company’s Perth Amboy factory. (Collection of Richard Veit.) This early-twentieth-century photograph gives a good idea of the size of typical pieces of architectural terracotta. Note that almost all of the blocks are hollow.

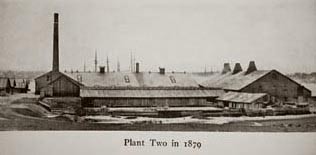

Photograph of the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company. (Courtesy, Collection of the Historical Society of Princeton.) This photograph shows Alfred Hall’s original brickworks/yellow ware pottery turned terracotta factory on Buckingham Avenue in Perth Amboy as it appeared in 1879.

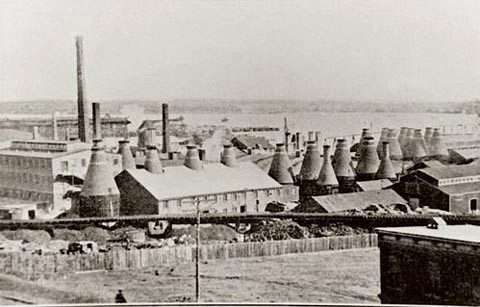

Photograph of the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company’s factory from Geological Survey of New Jersey, Vol. IV, Clay Industry, 1904. Notice the enormous kilns.

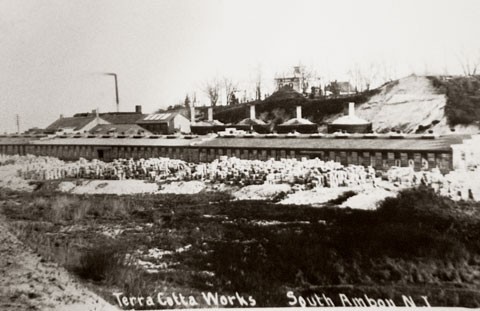

Postcard photograph of the South Amboy Terracotta Company, later part of the Federal Seaboard Terracotta Corporation. (Collection of Richard Veit.) Note the line of kilns and the extensive stock of finished ware

Asbury Park Convention Hall, 1928–1930, New Jersey. (Photo, Richard Veit.) The building features buff and polychrome terracotta details. The terracotta employed in it was produced by the Federal Seaboard Terracotta Corporation.

Gravemarker, Mount Holly, New Jersey, 1804. Terracotta. H. 18". (Photo, Richard Veit.) This early ceramic gravemarker marks the final resting place of William Price. Presumably it was produced by a local potter. Apparently it broke in two and was repaired, unsuccessfully, with some sort of adhesive. An accompanying footstone also survives.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1879. Terracotta and sandstone. H. 120". The Ellen Falvey Royle gravemarker is located in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Perth Amboy. It dates from 1879 and employs both buff and red terracotta. The core of the marker, which has survived less well than the terracotta, is sandstone. The roof and cross are yellow, unglazed terracotta; the columns are red, unglazed terracotta.

Detail of the frieze on the south side of the gravemarker illustrated in fig. 10. The frieze depicts a menagerie of small animals, including flies, spiders, frogs, and birds. One wonders whether they were intended for the gravemarker or reused from some other project. The frog seen here is about to swallow a spider. The frog is approximately two inches tall.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, ca. 1870. Terracotta and marble. H. 88". The Sofield family memorial, located in Alpine Cemetery, is one of the larger surviving terracotta monuments. When erected it was ornamented with four marble plaques inscribed with personal information about the deceased. Only two of these remain: one for David Sofield, age 76, and another for his wife, Mary, age 70. David died in 1873, his wife in 1870. Either the marker is backdated or it was erected after other family members passed on, as there were no terracotta producers in Perth Amboy in 1870.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1878. Terracotta. H. 57". The C. Madsen marker, made from buff-colored unglazed terracotta, is located in Alpine Cemetery. Made for a six-month-old child, it shows amazing attention to detail.

Detail of the gravemarker illustrated in fig. 13. One of four clusters of roses applied to the faces of the Madsen marker. Note the similarities between the stippled background on this marker and that of the Thulesen marker (see fig. 1). Although neither piece is signed, one wonders if the same craftsman produced them.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, ca. 1880. Terracotta. H. 32". This uninscribed baluster, molded from red, unglazed terracotta, is a good example of the architectural pieces that were employed as gravemarkers. It is located in Alpine Cemetery.

Gravemarker, Woodbridge, New Jersey, 1913. Terracotta. H. 29". The Eni Egnac marker is located in St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Cemetery. This three-bar cross marker is made from white glazed terracotta.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1918. Terracotta. H. 75". The John and Mary Halbert marker is a good example of mass-produced terracotta gravemarkers with faux granite finish. The granite-like texture was produced using a sprayed on glaze and was marketed under the trade name Granitex. The marker dates from 1918 and is located in Alpine Cemetery.

Gravemarker, Metuchen, New Jersey, ca. 1920. Terracotta. H. 70". This is an uninscribed polychrome gravemarker from Hillside Cemetery. It incorporates deep blue tiles for the border and cross around a centerpiece shield that shows St. Christopher. These pieces may have been scavenged from other projects. Together they form a remarkable composition.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1900. Terracotta. H. 27". The Joseph Bauman marker is made of brick red terracotta and combines a cross motif with a golden Star of David. It is located in St. Mary’s Cemetery, and dates from 1900. This is the back of the marker.

Mausoleum, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1920. Terracotta. H. approx. 144". Karl Mathiasen was a motivating force behind the development of New Jersey’s terracotta industry. A Danish immigrant, he worked as a potter for Alfred Hall after coming to America. Later, he worked for terracotta manufacturer Robert Taylor in Boston, and subsequently at the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company. In 1888 he and his brother-in-law Otto Hansen founded their own firm. In 1893 it became the New Jersey Terracotta Company, later part of Federal Seaboard. His mausoleum, which appears to be made from granite is, of course, terracotta.

Detail of the gravemarker illustrated in fig. 17. This close up of the Halbert marker shows the terracotta body underneath the granite-like glaze.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1892. Terracotta. H. 29". This pastel colored terracotta gravemarker commemorates two children: Alfred Mortensen (1891–1892) and Niels Peter Mortensen (1888–1892). The inscription is in Danish. The gravemarker is located in Alpine Cemetery.

Gravemarker, Metuchen, New Jersey, 1905. Terracotta. H. 80". The Bruno Grandelis marker is arguably the most artistic terracotta monument produced. It is also the only marker that depicts an actual individual. The monument is located in Hillside Cemetery

Detail of the gravemarker illustrated in fig. 23.

Reverse of the gravemarker illustrated in fig. 23.

Fraternal marker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, ca. 1900. Terracotta. H. 14". These mass-produced ceramic gravemarkers were erected by members of the Danish Brotherhood and Sisterhood, a fraternal organization begun by Danish-American Civil War veterans. The gravemaker is located, as are many just like it, in Alpine Cemetery.

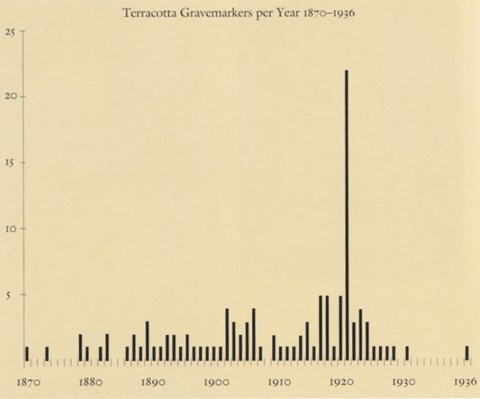

A bar chart showing dated terracotta gravemarkers and the years in which they were erected. (Courtesy, Richard Veit.) Notice the strong peak in 1918 that coincides with the influenza epidemic brought home by troops returning from World War I.

A photograph showing plaster models of proposed terracotta gravemarkers. (Courtesy, Columbia University, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York and the Friends of Terracotta Collection.) These were made by the New York Architectural Terracotta Company, working at the request of a Mr. Henry Hiss, from Woodlawn Cemetery, New York, and date from 1915. It is not clear that the New York company pursued the idea any further, though markers had long been made informally by many firms.

Gravemarker, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, 1912. Terracotta. H. 50". The Owen Revell marker is located in Alpine Cemetery. Made from unglazed tan terracotta, it is inscribed “Erected by his sorrowing relatives and friends of Lambeth England.” Lambeth was a center of ceramic manufacture, and one might speculate that Revell had learned his trade there.

Wall plaque, Perth Amboy, New Jersey, ca. 1928. Terracotta. H. approx. 36". A miniature polychrome Statue of Liberty adorns the façade of the former Greek Catholic Carpatho-Rusin Benevolent Association on Broad Street. It shows, on a small scale, the skill of the clayworkers. Note the interesting juxtaposition of the American flag, the three-bar cross, and the socket for an electric bulb in Liberty’s hand.

Victorian and early-twentieth-century urban cemeteries are generally filled with hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of gray granite and white marble memorials. In the cemeteries of central New Jersey’s Clay District, this rather homogenous picture is punctuated by nearly two hundred colorful red, green, blue, and brown ceramic gravemarkers (figs. 1, 2). Produced from architectural terracotta, they are reminders of a once thriving industry and the people who worked in it. At the same time, they provide a material record of the ceramicists’ skills, the potential of their material, and, even more importantly from an archaeological standpoint, dated examples of their work. Terracotta markers are found in a band running diagonally across New Jersey between Woodbridge in the north and Trenton in the south. A handful of examples are also found in nearby Staten Island, New York. The markers’ distribution reflects the presence of rich clay deposits associated with the Raritan Formation and, more specifically, the location of turn-of-the-century terracotta factories (fig. 3).

The terracotta these markers were made from is not simply the brick red stuff of flowerpots and utilitarian redwares; rather, it is architectural terracotta. This is a form of ornamental ceramic cladding used in architecture, made from sculpted and molded clay. The clay body has a fine texture that allows it to be molded, sculpted, and glazed. Terracotta was often made in the form of hollow blocks with internal webbing or supports that allowed it to be both strong and light (fig. 4).

The Rise and Fall of New Jersey’s Terracotta Industry

Although terracotta is an ancient material, used by cultures as distinct as the Romans and the Qin Dynasty Chinese, it fell out of use after the fall of the Roman Empire and was not revived until the Renaissance. The noted architect Andrew Jackson Downing introduced terracotta to Americans in the mid-nineteenth century. James Renwick and Richard Upjohn, Sr., also influential architects, seconded Downing’s call for terracotta in architecture. By the 1880s Charles Thomas Davis, an authority on the ceramics industry, was writing that:

The largest terracotta works in this country [the United States] are located at Perth Amboy in New Jersey. Woodbridge and Perth Amboy both owe their prosperity to the manufacture of terracotta, fire-brick and tiles, and the traveler journeying westward in New Jersey, from either of these thrifty towns, will find his way skirted by frequent hollows and excavations stretching irregularly on either hand . . . this section should become to us what the Staffordshire district is to England.[1]

Nineteenth-century architects viewed terracotta as a sort of wonder material. It was less expensive than stone; it could be mass produced to exacting specifications; it easily took a glaze; it was fireproof; it could be sculpted and molded; it was easy to clean; and it was billed as lasting forever. Moreover, it was associated with several innovative architectural tastemakers, ranging from the aforementioned Renwick and Upjohn to Stanford White, Cass Gilbert, and Henry Furness.

The first individual to attempt the manufacture of terracotta in New Jersey was Diedrich Winnter of Newark. A potter by training, Winnter and his associates made a terracotta cornice for the Corn Exchange Building in New York City in 1853. Sadly, it failed after only one winter’s frosts.[2] One wit later noted:

This company was owned and operated by several educated Europeans (Winnter, Haefeli, Huber, and Schrag) who during the hours of labor... used to sweeten their tasks by reflections upon the Renaissance—classical conversations in Latin, Greek, French, and German...and it is assumed that if they had been possessed of less mental culture, if they had been poorer scholars and better terracotta makers, success would not have eluded them.[3]

Despite this failure, other manufacturers in Trenton, Burlington, and Gloucester City began to manufacture architectural terracotta in small quantities.

This changed in 1873 when Alfred Hall, a successful brickmaker and yellow ware potter from Perth Amboy, decided, at his nephew William’s suggestion, to start manufacturing terracotta. Alfred Hall sought the advice of James Taylor, former superintendent of a British terracotta factory, who had spent the last five years helping establish terracotta factories in Chicago, Boston, and New York. Taylor suggested his brother Robert as a technical advisor to Hall. With Robert Taylor on board, Hall reincorporated his firm as the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company.[4] Shortly thereafter, Hall bombastically claimed, “This new terracotta industry (of which I was the founder) brings into the state about three hundred thousand dollars per annum, and with proper aid from capital would soon bring in more than one million per annum, and eventually will bring in more wealth than all the crockery business in Trenton”(fig. 5).[5]

As Hall predicted, the industry continued to grow. He, however, left the company he had founded following a disagreement with his co-owners. Nevertheless, the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company rose to preeminence in the field. By 1898 it had forty-six kilns and dominated the Perth Amboy waterfront. Charles DeKay, writing for Harper’s Weekly, noted:

An early riser in the ancient village of Tottenville, Staten Island, glancing across the narrow Achter Kull, shall see on a misty morning the white low-lying sea fog pierced by singular yet picturesque forms. They are truncated cones of brick with lighter bands running around them. They stand near the water’s edge, and might readily be taken for something Egyptian or otherwise Oriental, for Indian tepes [sic] or saints’ tombs in some queer country of Indo-China.[6]

Early ceramic historian Edwin Atlee Barber described these kilns, as “among the largest of the kind on this continent, if not the world”(fig. 6).[7]

Other companies followed the lead of the Perth Amboy Company and established themselves in and around Perth Amboy. Noteworthy producers included the New Jersey Terracotta Company, the Standard Terracotta Company, the Excelsior Terracotta Company, and the South Amboy Terracotta Company (fig. 7). As competition increased, profits fell. In reaction, four companies—Atlantic Terracotta of Staten Island, the Perth Amboy Terracotta Company, the Excelsior Terracotta Company of Rocky Hill, and the Standard Terracotta Company of Perth Amboy—merged in 1906–1907 to form the dominant player in the marketplace, Atlantic Terracotta. All four plants remained in operation. In 1912 the company produced 7,500 tons of terracotta cladding for what was then the tallest building in the world, New York City’s Woolworth Tower. Later, in 1932, it produced the stunning polychrome terracotta façade for the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[8]

In 1909 Charles Geer, the first president of the newly reorganized Atlantic Terracotta, left and formed a competing firm, Federal Terracotta in Woodbridge. In 1928 Federal merged with the South Amboy Terracotta Company and the New Jersey Terracotta Company to form the Federal Seaboard Terracotta Corporation. During World War I, Federal Terracotta manufactured terracotta practice bombs for the Army Air Corps.[9] Later, the company became an important producer of extruded wall ashlars and swimming pool blocks. Their most famous buildings are the McGraw Hill Building in New York City and Asbury Park’s Convention Hall (fig. 8).

The Depression of the 1930s led to a contraction in the industry. Atlantic closed down its Rocky Hill plant, and by 1941 Federal Seaboard had shut down its Woodbridge Plant. During World War II, the number of local workers in the industry dropped below 800 for the first time since 1900.[10] After the war, architects turned to new, less expensive materials; by 1968 the last remaining company, Federal Seaboard, had closed its doors. The end had been a long time coming. In 1932 E. V. Eskesen, president of Federal Seaboard Terracotta, wrote with prescience, “The dream of the modern architect is to build houses entirely out of metal, glass, and cement. In this construction, brick, tile, or terracotta has no place.”[11]

Terracotta Gravemarkers

One little known product of the terracotta works was gravemarkers. Although gravemarkers are generally assumed to be made from stone, many other materials have been used for memorials. Wooden memorials have been used in the United States since colonial times. During the nineteenth century, iron gravemarkers were occasionally produced. Cast zinc markers, sold under the trade name Monumental Bronze, are common in late-nineteenth-century cemeteries. Homemade concrete gravemarkers are also common in twentieth-century ethnic cemeteries.

Even earlier, the Qin Dynasty Chinese (221–207 b.c.) buried a magnificent army of terracotta workers with their emperor, and the ancient Romans made gravemarkers out of terracotta. Later, in seventeenth-century England, enterprising potters were producing gravemarkers, and in the nineteenth century, a variety of monuments were made from a ceramic material called Coade’s Stone.[12]

The first ceramic gravemarkers in New Jersey date from the early nineteenth century and predate the terracotta industry. There is an 1804 redware marker in Mount Holly (fig. 9) and a pair of stoneware markers in Port Elizabeth. The latter are associated with a nineteenth-century glassworks and were apparently produced from the clay used to make crucibles. These early clay markers are, however, nearly unique and cannot be considered part of a larger local tradition of gravemarker production.

Ceramic memorials made up only a small portion of the terracotta plant’s products. To date 175 have been found in New Jersey and adjacent parts of New York State. Other examples have been reported from upstate New York, near the site of a terracotta factory, as well as from California, Louisiana, and Ireland. The markers were produced in a variety of forms, most of which fall within the standard canon of Victorian mourning art. They include crosses, tablets, pedestals surmounted by urns, obelisks, and statues. Some were simply made, while others are quite elaborate. This variation is intentional. In the words of Edmund Gillon, “The Victorians, with their great sense of the personal, felt that individual achievement should be recognized. It did not seem to them that a child should have the same stone [or in this case terracotta] as a war veteran, or that the minister or ship captain should lie, as they do today, under nearly identical markers.”[13] Size and ornamentation were particularly important. Kenneth Ames has pointed out that “Most planners of America’s rural cemeteries apparently accepted social class and hierarchy as a fact of nineteenth-century life. The major rural cemeteries are graphic registers of social significance and status.”[14] Rural cemeteries were not, in fact, located in rural areas, but were products of the rural cemetery movement, which advocated situating cemeteries outside urban centers and designing them so that they presented a pleasing, park-like setting. Most of the gravemarkers discussed here are found in small Roman Catholic cemeteries associated with new eastern and southern European immigrants, but some are found in Alpine Cemetery, a local example of the rural cemetery movement, located in Perth Amboy.

The markers vary considerably in size. Some are less than six-inches tall, while others reach seven or eight feet in height. One of the largest and most impressive is for Ellen Royle, who died in 1879 (figs. 10, 11). The marker’s central core was made from brown sandstone used to support a large terracotta cap with columns. The effect is stunning. Another fine composite marker is the Sofield family memorial (fig. 12). It is dated 1873 and was made from several pieces of yellow terracotta. Spaces where small marble tablets were once attached with personal information about the deceased are clearly visible; unfortunately, some have eroded and others are missing.

The earliest terracotta gravemarkers date from the 1870s and 1880s. The latest examples date from the 1930s. Crosses were the single most popular style of gravemarker, making up forty-two percent of all dated examples. Markers in the form of urns, tablets, columns, obelisks, and sculpture or statuary were also made (figs. 13, 14), and in a handful of cases, architectural elements were recycled as gravemarkers (fig. 15). The greatest variability in gravemarker forms occurred in the 1890s.

Although crosses as a generic category are quite common, the form of the crosses varies tremendously (figs. 16, 17). Some are in the form of Orthodox crosses, a few resemble tree trunks, and others imitate carved granite. Several show the cross bar of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Many of the markers use color to good effect. This is true of both glazed and unglazed examples. Glazed terracotta came into widespread use after 1894.[15] On some of the later markers, the lettering was accentuated with color, and white or gray markers were ornamented with gold, black, blue, or red details. Particularly colorful markers include an unusual cruciform marker in the Hillside Cemetery, Metuchen, which sports a shield showing St. Christopher surrounded by a band of azure blue tiles and a cross in the same color (fig. 18). Another colorful marker commemorates Joseph Bauman who is buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Perth Amboy. It is a simple one-piece cross and tablet in red terracotta with a golden Star of David. The question of Herr Bauman’s religion remains unresolved (fig. 19).

The simplest markers recorded, and presumably the least expensive, were the aforementioned recycled architectural elements, and simple, uninscribed one-piece memorials. However, elaborate mausoleums were also made of terracotta. Appropriately enough, Karl Mathiasen (died 1920), the first president of the New Jersey Terracotta Company, had one erected to his memory (fig. 20) as did the Hansen family, who were associated with the same company.

In the second decade of the twentieth century, mass-produced, standardized markers with granite finishes, produced in three basic forms, crosses, obelisks, and tablets, became popular. These markers employed a finish known as Granitex, which has the look and appearance of granite. Unless chipped, they can be very hard to distinguish from real stone. They show just how closely terracotta could mimic other materials, and they are much less conspicuous than the colorful earlier markers (fig. 21). They probably reflect an attempt at commercial production by the factories.

The gravemarkers highlight the ethnic diversity of Perth Amboy and the Clay District. The 1910 census reveals that seventy-seven percent of Perth Amboy’s inhabitants were foreign born or the children of foreign-born parents. This figure correlates well with what we know of the terracotta industry. In 1881 Alfred Hall noted that he had “Men of all nations familiar with working clay in his employ.”[16] Although most of the lettered gravemarkers have English inscriptions, epitaphs in Danish (fig. 22), German, Italian, Hungarian, and Russian were also noted. Factory documents indicate that expatriate Englishmen provided the technical know–how that got the fledgling industry off the ground. Danish émigrés rapidly assumed management positions in many of the companies, and Italians and some Danes came to dominate the modeling departments. Hungarians, and in later years Puerto Rican immigrants, also figured prominently in the factories. Arguably the most moving memorial is that of Bruno Grandelis. It dates to 1905 and was sculpted from white glazed terracotta by a highly skilled craftsman. The marker depicts, just smaller than life size, a casket with its lid ajar set between two truncated pillars topped by lit torches. From the casket an angel is rising carrying in her arms a young boy, probably four-year-old Bruno, dressed in a sailor’s suit (figs. 23, 24). Inscribed on the marker’s reverse (fig. 25) is a single line in Italian, Tuo padre fece, which translates as “your father made this.” It represents the height of Victorian mourning iconography realized in terracotta. Unfortunately, Mr. Grandelis has yet to be identified in factory or census records. He was clearly an extraordinarily talented craftsman.

Another common gravemarker form, though never dated, was the “DBS” tablet (fig. 26). Although many of the markers discussed so far are unique, these tablet markers were quite literally stamped from the same mold, or, at most, a couple of very similar molds. They are associated with the Danish Brotherhood in America, a fraternal order founded in 1882 by Danish veterans of the American Civil War.[17] In 1893 an accompanying Danish Sisterhood was founded, hence the initials DBS for Danish Brother and Sisterhood. This organization provided its members with an array of benefits including life insurance, help in old age and sickness, and burial aid. The mass-produced DBS terracotta gravemarkers are associated with the local chapters of these organizations. In truth they are not gravemarkers but fraternal markers, sometimes used with and sometimes in place of regular gravemarkers.

Graphing the markers by decade reveals an interesting distribution. The first inscribed markers bear dates in the 1870s, around the time the first factories were formed. They gradually grew in popularity from the 1870s until roughly 1910. Then, they exploded in popularity. After 1920, they rapidly fell to their nadir (fig. 27). Breaking down the distribution by year reveals the cause of this newfound popularity. More gravemarkers were produced in 1918 than in any other year. This was the year that a devastating influenza epidemic struck the nation. In New Jersey, 300,000 cases were reported in October, November, and December, and over 17,000 people died. Although exact statistics are unavailable, deaths from the flu occurred so rapidly in Perth Amboy that mass graves were dug to hold the bodies. The catastrophe was compounded by an explosion at the nearby Morgan munitions factory, which left hundreds of individuals homeless at the height of the epidemic. Lacking adequate shelter and provisions, they were even more susceptible to the flu. Alpine Cemetery set aside land for burial of these victims. Many of the gravemarkers in this section of the cemetery were made from terracotta, although other graves have small numbered marble markers. The undulating landscape, largely devoid of gravestones, probably indicates that many graves were never marked at all.

In the 1920s and 1930s the markers decreased in popularity. The latest one recorded dates from 1936. Although it might seem that more, not less, terracotta gravemarkers should have been made during the Depression, many terracotta workers were laid off and therefore in no position to make gravemarkers or anything else.

Manufacture

For a roughly sixty-year period, terracotta gravemarkers were made in New Jersey and New York. Although we have documented their distribution and cataloged their forms and inscriptions, questions remain. How were the markers made? Who produced them? Why did they make them and why did they stop?

The manufacture of architectural terracotta is well understood and continues today at a handful of factories: Gladding McBean in Sacramento, California; the Boston Valley Terracotta Company in Orchard Park, New York; and Ibstock Hathenware in Normanton-on-Soar Loughborough, England, are the industry leaders. A basic overview of how terracotta was made is provided below; however, the process varied from place to place and changed over time. Presumably the process employed to make gravemarkers was similar.

As mentioned earlier, central New Jersey is rich in clays. In Middlesex County, where the Amboys and Woodbridge are located, the Raritan Formation, a rich Cretaceous deposit suitable for stoneware and terracotta, is found close to the ground surface.[18] Easily mined, it was considered the best clay available for terracotta. In fact, Charles Davis felt it necessary to add the following caveat to his 1884 volume A Practical Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks, Tiles, Terracotta, etc., “In devoting so much space to the description of New Jersey terracotta clays, no slight is intended to the terracotta productions of other sections of the country as ... they seem to take great care in the execution of all architectural terracotta.”[19]

The clay was generally mined by hand in open pits, using shovels and carts. It was then allowed to weather and oxidize. Then it was washed or mixed down with water until it was the consistency of cream.[20] It was then strained and allowed to settle in a drying pan. Next grog, generally “scrap terracotta, fire brick, saggers, scrap pottery, sanitary ware, hollow tile, or specially calcined terracotta clays,” was added.[21] Up to thirty percent of the final mixture might be grog, which helped eliminate shrinkage in the kiln. The clay was then put through a pug mill and aged. Now it was ready for molding. Architects supplied drawings to the factories, which would be interpreted in clay or plaster (fig. 28).

The modelers and sculptors used a thirteen-inch long ruler in their work to make up for shrinkage in the kiln. The clay body was either sculpted or pressed into a plaster mold. In 1913 Harry Lee King, an oYcer with several New Jersey companies, wrote:

The modeling shop is a component part of the plant with a pervading atmosphere scarcely akin to inert clods of clay and dull plastic forms ... . Here the pliant modeling clay, under the skillful manipulation of artists, takes on many forms, perhaps ... the graceful sweep of some festooned panel, a stately caryatid, a graceful capital, or ... a fanciful grotesque.[22]

Our only contemporary description of the manufacture of a terracotta gravemarker comes from an 1895 newspaper article, where a journalist described seeing a “boy carving in the soft brown clay the inscription for a memorial plaque.”[23]

Some gravemarkers appear to have been sculpted, whereas others were molded. The latter were made in plaster molds, reinforced with strap iron or wires, which could be reused over and over. Pressing the clay into the molds took great strength. After a mold was filled, the pressers would set it aside to dry. The piece was then removed and allowed to sit for several days. Next it was finished by rubbing and trimming. It was then taken to a drying room heated to about eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit. After two days of drying, glazes and slips were applied to the hardened unfired body. Red, buff, and gray was the triumvirate of colors on which the industry initially built its strength. In the 1880s a variety of new colors were introduced. White, a popular color for gravemarkers, was first produced in 1889.[24] A correspondence-school textbook on the manufacture of terracotta, printed in the early twentieth century, noted “...granite, with its mottled or speckled coloring [and] limestone and sandstone with various toolings of the surface can be closely copied” .[25]

The ware was then stacked in the kiln, with sandy clay wads known as bearings placed between the pieces, forming compartments. These bearings served to distribute the weight of the wares and also helped contain explosions within the kiln. MuZe kilns, which kept the hot gases separate from the ware, were particularly common. Many New Jersey manufacturers preferred updraft kilns. At first, charcoal was the fuel of choice; later, coal, oil, and even gas were employed. The firing process itself lasted between one and two weeks. Peter C. Olsen, president of the Federal Seaboard Terracotta Corporation, accurately described terracotta as “a piece of granite that’s been made in two weeks.”[26] Temperatures inside the kilns reached 2300 degrees Fahrenheit, and were measured using Seger or pyrotechnic cones, which melted once the desired temperature had been reached. After cooling, sometimes for as long as five days, the ware was removed from the kilns and shipped to its final destination. Pieces were assembled using wooden dowels, iron bars, and metal anchors, all of which tend to decay and cause failure. After installation, the terracotta was cleaned using a dilute solution of oxalic or sulfuric acid.[27]

Very few specifics can be added regarding the production of terracotta gravemarkers. Out of those examined, only a handful of gravemarkers were marked. One in Trenton is marked Lamberton, a pottery manufacturer; another in Alpine Cemetery is marked with the logo of the South Amboy Terracotta Company; and a third, found in South Amboy, is stamped with the mark of the Excelsior Terracotta Company, South Amboy. This last marker is curious, as there is no record of an Excelsior Terracotta Company in South Amboy. Many of the markers in Perth Amboy are believed to have been the work of Nels Alling, a talented Danish émigré sculptor.[28] Sadly, Mr. Alling also failed to sign his work.

Interpretations and Conclusions

Terracotta gravemarkers, much like the glass chains and canes made at day’s end by glassblowers, seem to have been a natural byproduct of the industry. They were inexpensive to manufacture, colorful, and personal. Writing in the 1920s, a cemetery superintendent in Bridgeport, Connecticut, decried the gravemarkers chosen by new immigrants and complained of the “weird taste of the foreign element for freakish monuments and such.”[29] He undoubtedly would have been appalled by the colorful ceramic gravemarkers of the Clay District. Nevertheless, they provide us with an unusual material avenue for understanding this industry and the people who worked in it. Given the steps in the manufacturing process, the workers could not have produced the markers without management’s tacit approval at the least. Interestingly enough, attempts to formalize their production under the trade name Tanagras seems to have failed. The markers appear to be a form of small-scale craft production occurring within and taking advantage of the larger industrial setting.

Many of them are incredibly elaborate (fig. 29), true showpieces of the sculptor’s talents. The terracotta industry produced a highly visible product in architectural elements and was a source of considerable pride for the people of the Clay District. Buildings throughout Perth Amboy display some of the finest and most imaginative terracotta in the United States. Ornaments as diverse as race cars, dancing pastries, and a miniature Statue of Liberty decorate local buildings (fig. 30). This pride seems to have spilled over into the cemeteries as well.

At the same time, many of the gravemarkers are associated with new immigrants and the children of immigrants, individuals who may have been quite poor. Except for the most skilled workers, wages in the Clay District were low. A ceramic gravemarker may have been an economical substitute for a granite or marble memorial.

As previously noted, many of these gravemarkers are located in ethnic cemeteries and are often associated with inexpensive plots. Their neighbors are often wooden, metal, and concrete gravemarkers, all homemade. Terracotta was an improvement on all these materials as it was much more long lasting. However, in one instance, we found evidence that a terracotta gravemarker had been discarded when the family could afford a more traditional granite memorial.

During the influenza epidemic of 1918, ceramic memorials stood in for stone. However, later in the 1930s they petered out and eventually disappeared. Again, no single factor seems to account for their decline. During the 1930s the factories were declining, and there may have been fewer opportunities to make gravemarkers. Companies may also have looked askance at using up raw materials and time on the job for personal items. Skilled workers lost their jobs, reducing the opportunity to make anything from terracotta. At the same time, some of the older markers may have been showing their age, as the dowels that held them together failed and urns toppled off obelisks. Similarly, more acculturated immigrants may have disapproved of the colorful memorials of their predecessors.

For roughly sixty years, terracotta gravemarkers were made and used in the Clay District of New Jersey and New York. These colorful markers provide a glimpse of the incredible craftsmanship found in the terracotta industry, commemorate some of the individuals who worked there, and highlight the potential of this ceramic medium. Today, New Jersey’s terracotta industry is a memory, but the gravemarkers remain to remind us of its glory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Rob Hunter for the opportunity to include this article in Ceramics in America. Gavin Ashworth’s photographic skills helped bring the markers to life. Two institutions have supported our research on terracotta and gravemarkers in particular: Monmouth University and the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission. Numerous individuals at local historical societies in New Jersey and New York, as well as Susan Tunick, the dean of terracotta studies, have shared their knowledge, photographs, and artifacts with us. The title of this article was inspired by her New York City walking tour, “Terracotta: Don’t Take It For Granite.” Robert Schuyler, from the University of Pennsylvania, greatly encouraged Richard Veit’s initial research on terracotta in Perth Amboy.

Charles T. Davis, A Practical Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks, Tiles, Terra-Cotta, Etc. (Philadelphia: Henry, Carey, Baird, and Co., 1884), p. 310.

Walter Geer, The Story of Terracotta (New York: Tobias A. Wright, 1920), p. 37.

Anonymous, The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey (Newark, N.J.: Newark Museum, 1947), p. 3.

William C. McGinnis, History of Perth Amboy, 1651–1958, 4 vols. (Perth Amboy, N.J.: American Publishing Company, 1962), 4: 13.

Alfred Hall of Perth Amboy to the organizers of an exposition in Louisiana, October 1, 1884, Special Collections and Archives, Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick, N.J.

Charles DeKay, “What Terra Cotta May Do,” Harpers Weekly 39 (1895): 655–58.

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 2d ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1901), p. 386.

Michael Stratton, The Terracotta Revival: Building Innovation and the Image of the Industrial City in Britain and North America (London: Victor Gollancz, 1993), p. 203.

Richard Veit and Mark Nonestied, “Bombs Away! Unearthing a Cache of Terracotta Practice Bombs From the First World War,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002): pp. 227–31.

Richard Veit, Skyscrapers and Sepulchers: A Historic Ethnography of New Jersey’s Terracotta Industry (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1997), pp. 31–43.

Gary F. Kurutz and Mary Swisher, Architectural Terracotta of Gladding McBean (Sausalito, Calif.: Windgate Press, 1989), p. 10.

Allison Kelly, Mrs. Coade’s Stone (Upton-on-Severn, Eng.: Self Publishing Assoc., 1990), pp. 243–45.

Edmund V. Gillon, Victorian Cemetery Art (New York: Dover, 1972), p. ix.

Kenneth L. Ames, “Ideologies in Stone: Meanings in Victorian Gravestones,” Journal of Popular Culture 14, no. 4 (1981): 651.

DeKay, “What Terracotta May Do,” p. 655.

John P. Wall and Harold Pickersgill, History of Middlesex County, New Jersey in Three Volumes (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1921), p. 393.

Varick A. Chittenden, The Danes of Yates County: The History and Traditional Arts of an Ethnic Community in the Finger Lakes Region of New York State (Penn Yann, N.Y.: Yates County Art Council, 1983).

J. Volney Lewis and Henry B. Kummel, Geological Survey of New Jersey. Bulletin 14. The Geology of New Jersey (Union Hill, N.J.: Dispatch Printing Company, 1915), p. 126.

Davis, A Practical Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks, Tiles, Terra-Cotta, Etc., p. 310.

Frank G. Matero, Elizabeth A. Bede, and Albert Tagle, “An Evaluation of the Effects of Cleaning Methods on Unglazed Architectural Terracotta: With Notes on the Manufacture and Characterization of Nineteenth-Century American Production” (Architectural Conservation Laboratory, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1995), pp. 8–9.

Hewitt Wilson, “Monograph and Bibliography on Terracotta,” American Ceramic Society Bulletin 5, no. 2 (1926): 98.

Harry Lee King, “A History of Architectural Terracotta,” Architecture and Building 45, no. 1 (1913): 311–15.

DeKay, “What Terracotta May Do,” p. 657.

Walter Geer, Terracotta in Architecture (New York: Gazlav Brothers, 1892), p. 56.

William S. Lowndes, Plastering and Architectural Terracotta (Scranton, Pa.: International Text Book Company, 1920), p. 29.

“Federal Plant was Organized 60 Years Ago,” Perth Amboy Evening News, December 4, 1948.

Matero, Bede, and Tagle, “An Evaluation of the Effects of Cleaning Methods on Unglazed Architectural Terracotta,” p. 18.

McGinnis, History of Perth Amboy, p. 43.

John Matturi, “Windows in the Garden: Italian-American Memorialization and the American Cemetery” in Ethnicity and the American Cemetery, edited by Richard E. Meyer (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1993), p. 30.