Skull, Loudoun County, Virginia, probably ca. 1830–1860. Low-fired earthenware. H. 3/4". (All images, Christopher C. Fennell.)

Rear view of the clay skull illustrated in figure 1. This view shows the inscriptions on the sculpted surface.

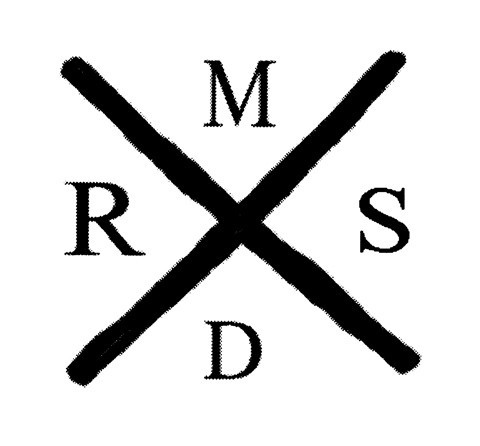

Diagram of the inscription on the back of the skull illustrated in fig. 2.

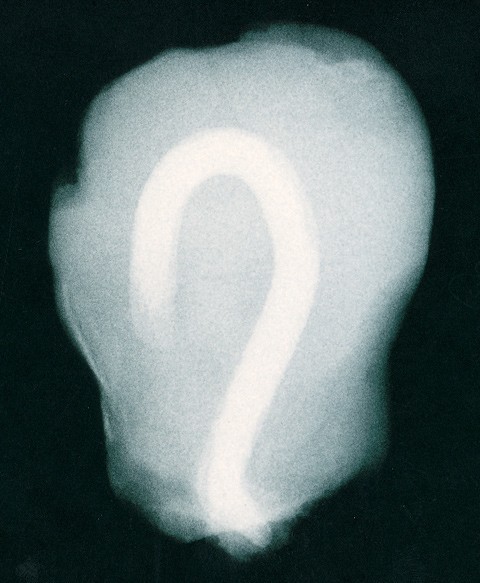

X-radiograph of the skull, revealing the iron wire used as base for holding the clay.

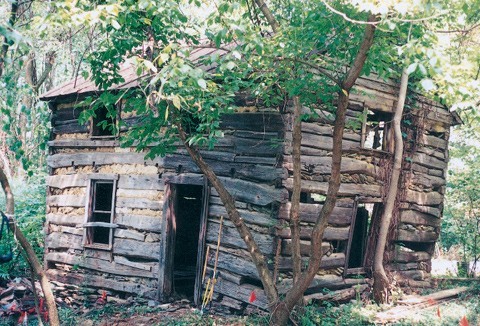

House site in Loudoun Valley, Virginia, where the clay skull was found.

Excavations at anearly-nineteenth-century house site in Loudoun County, Virginia, uncovered an artifact that was likely created and used as a material component of a malevolent curse. Such objects, which were typically created and deployed in secret, are rarely found. The artifact is a small clay likeness of a human skull (fig. 1), three-fourths of an inch in height, which was hand sculpted using the red-yellow clay available from the subsoils of the area. The anatomical features of the skull are very well defined and proportioned. On the upper back of the skull is a raised figure of crossed lines or a large “X” (fig. 2). The initials R, M, S, and D appear in raised clay between the arms of the “X” (fig. 3). The initial M is more eroded than the others and could be an H. X-rays reveal that the object has a small loop of iron wire as an internal core (fig. 4). The person who made this figure likely used the wire as a base to hold the clay, sculpting the material when it was partially hardened. This artisan shaped the single form of the skull with its raised inscription and then fired the unglazed figure at a relatively low temperature. The object was not made in a physical mold, but its complex design was likely influenced and shaped by particular religious beliefs and practices.

This skull was uncovered six inches below the soil surface underlying the floorboards of a small house (fig. 5), roughly halfway between the north and south doorway entrances. The object was located in association with other artifacts dating to the period of approximately 1780–1860. The house is located several miles to the south of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in a heavily wooded, upland area to the east of the Shenandoah Valley. The surviving structure is one and one-half stories tall, one room deep, two rooms wide, with a central chimney for stoves, and it was constructed of thick, hand-hewn timbers interwoven in a cross-notch fashion. German settlers in this region were primary users of this type of floor plan and building method. However, the region was inhabited by a diverse population, including settlers of Scots-Irish, English, African, German, and Irish heritage. Census, tax, and land ownership records indicate that an Anglo-American family named Demory acquired and settled this property in the early 1800s. An unrecorded occupancy of the site by a family of German heritage may have preceded the Demory family settlement.

A variety of possible explanations for the artifact’s design includes its creation and use as a toy or gaming piece, an icon of a family’s armorial crest, an icon of a guild or secret society, or a form of memento mori. However, these interpretations prove unconvincing because none of them can account for all of the object’s attributes. The most persuasive explanation is that this object was part of a malevolent curse created pursuant to the beliefs and practices of an African-American or German-American folk religion.

Within certain African-American folk religion beliefs dating to this time period, one would invoke spiritual powers with an instrumental symbol of crossed lines to signify the intersection of the spiritual world with the land of the living. The purpose of the invocation would be communicated by the use of the accompanying symbol of the skull to signify death. The initials would be used to identify the person targeted by the curse. Placing the object in a pathway frequently traversed by the targeted person would facilitate the activation of the curse. Recently discovered documentary evidence indicates that in the 1840s the Demory family owned two enslaved African-American men named Joseph and Henry, one of whom may have been knowledgeable about such beliefs and practices. The initials of “MD” or “HD” also match the names of members of the Demory family. However, the initials “RS” cannot be explained as identifying a targeted person. Detailed census and tax records reveal no one with those initials living in the area during the relevant time periods.

Persons of German-American heritage possessed similar beliefs and practices, often called hexerei or “powwowing,” which were the product of a separate history and independent development. Here, too, the crossed lines invoked the summoning of spiritual powers, and the skull figure would communicate a focus on death. The name of the targeted person would be inscribed onto the object, again providing an explanation for the “MD” or “HD” initials. An object with such imagery related to a targeted person could be buried in the ground to symbolize the demise of that individual.

Notably, this German-American tradition also provides an explanation for the “RS” initials. A palindrome square of rotas or sator was a prominent form of written charm within this belief system, as were inscriptions employing Latin initials, such as “INRI,” in geometric patterns. This invocation was created by writing or inscribing a square of five-letter words in Latin:

S A T O R

A R E P O

T E N E T

O P E R A

R O T A S

This translates roughly as “the sower Arepo holds steady the wheels,” thus invoking a creative force that controls the wheels of the cosmos and the vicissitudes of fortune. In emphasizing the symmetrical quality of this magic square, inscriptions would often place the word rotas first and sator last. Protective uses of this charm date back to the late Roman Empire’s expansion throughout western Europe and were included in folk religion traditions used by German-Americans in the nineteenth century. The “RS” initials on the clay figure therefore could represent an abbreviation of the rotas palindrome, set within a geometric inscription, to provide a further invocation of spiritual forces. This explanation of the purpose and use of the clay skull remains the most persuasive at this juncture because it best accounts for all of the attributes and context of the artifact.[1]

Christopher C. Fennell, Ph.D.

Historical Archaeologist

Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia

<cfennell@alumni.virginia.edu>

An extended analysis and related bibliography concerning this subject are available in the author’s article entitled “Conjuring Boundaries: Inferring Past Identities from Religious Artifacts,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 4, no. 4 (2000): 281–313. Additional details concerning the history of the Loudoun Valley house site and its occupants over time are presented in the author’s dissertation, “Consuming Mosaics: Mass-Produced Goods and Contours of Choice in the Upper Potomac Region” (Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 2003).