Wye House, Talbot County, Maryland, ca. 1787. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Circa 1896 photograph showing (left to right) Elizabeth Phoebe Key Howard, Charles Howard Lloyd, Joanna Leigh Lloyd, and Mary Lloyd Howard Lloyd.

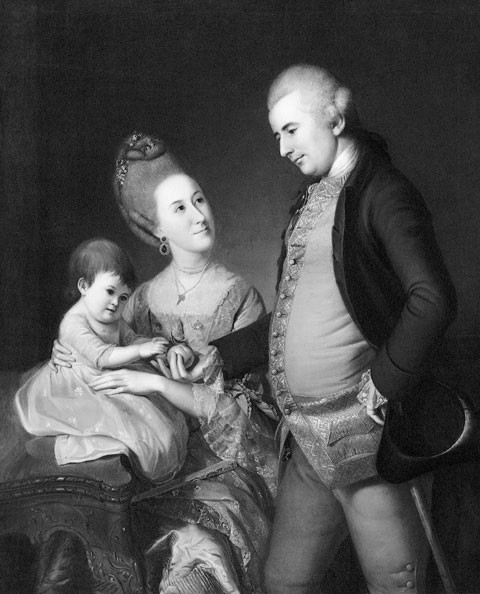

Charles Willson Peale, The Edward Lloyd Family, Maryland, 1771. Oil on canvas. 48" x 57 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Benjamin West, Richard Bennett Lloyd, London, ca. 1773. Oil on canvas. 36" x 28". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Charles Willson Peale, The Family of John Cadwalader, Philadelphia, 1771. Oil on canvas. 51 1/2" x 41 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Upholstered armchair, England, ca. 1760. Walnut with beech. H. 37 3/4", W. 28 1/4", D. 23". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock case, probably Easton, Maryland, ca. 1790. Walnut with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and oak. H. 91", W. 19", D. 10". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The movement is by Daniel Quare and Stephen Horseman of London and dates about 1715.

Salver by Jacob Marsh, London, 1754. Silver. H. 3 1/2", Diam. 28". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

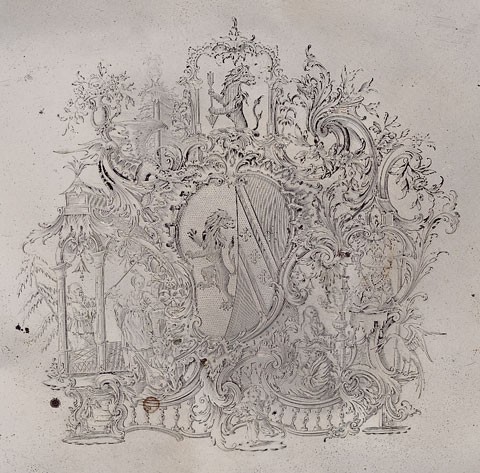

Detail of the engraving on the salver illustrated in fig. 8.

Bread basket by John Wirgman, London, 1754. Silver. H. 12 1/2", L. 13 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Platter, Chinese export for the British market, 1755–1760. Porcelain. 18" x 15". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cannon, England, ca. 1720. Bronze, iron, steel, and wood. L. 26". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Coat-of-arms of the Lloyd family, England, ca. 1785. Watercolor on paper. 12 3/4" x 15 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Coat-of-arms of the Lloyd family, England, ca. 1785. Watercolor on paper. 9 3/4" x 7 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

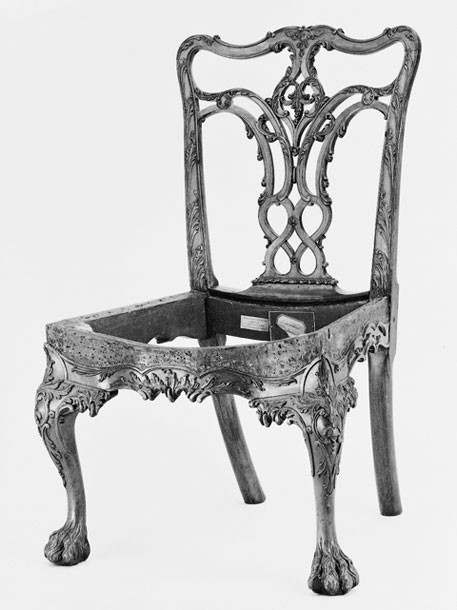

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 36 3/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 17 7/8" (seat). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Circa 1935 photograph showing part of the Wye House estate. The house, gardens, and greenhouse are oriented on a north-south axis.

Pier glasses, London, ca. 1755. Woods not identified. Left: H. 104" (not including appliqué), W. 41 1/2". Right: H. 104" (not including appliqué), W. 56 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the appliqué and guilloche on the left pier glass illustrated in fig. 17.

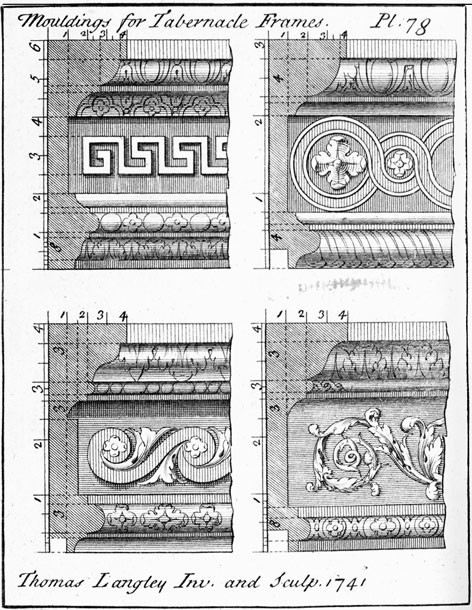

“Moldings for Tabernacle Frames” illustrated on pl. 78 of Batty and Thomas Langley’s The Builder’s Jewell, or Youth’s Instructor (1741). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Bedstead with foot posts dating 1755–1770. The mahogany posts are probably British, although similar examples were made in Philadelphia. The bed that the posts came from probably had a carved or molded cornice and elaborate curtains.

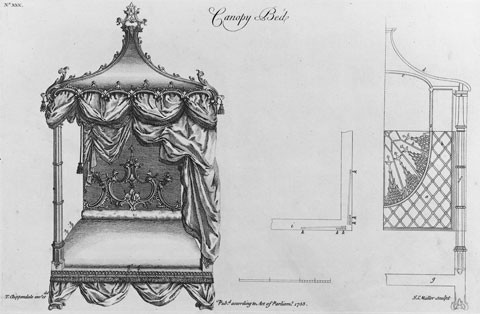

Design for a “Canopy Bed” with gothic posts illustrated on plate 30 in the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Chase-Lloyd House, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1773. Architect William Buckland was responsible for the interior and exterior design. He had previously worked on Mt. Airy, the home of Elizabeth Tayloe’s parents in Richmond County, Virginia.

“French chair,” London, ca. 1772. Beech with oak. H. 34 1/2", W. (seat) 24", D. 20" (seat). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bureau bookcase, London, 1750– 1760. Mahogany with cedrella, oak, and an unidentified conifer. H. 101", W. 47", D. 24". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The gilding is modern.

Bookstand, London, 1750–1760. Mahogany. H. 29", W. 24", D. 19". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing one of the doors in the principal first floor room of the Chase-Lloyd House. The carving is attributed to Thomas Hall.

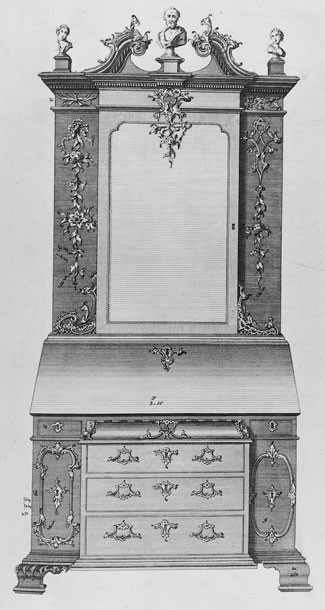

Design for a “Desk and Bookcase” illustrated on plate 78 in the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) This plate also illustrates leaves bound with ribbon as an optional frieze ornament on the left side. This motif, which occurs on the pier glasses ordered by Edward Lloyd III, was extremely popular in British furniture and architectural carving.

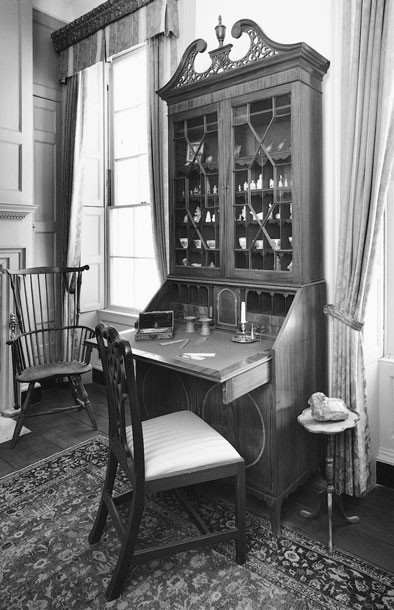

Desk-and-bookcase, Annapolis, John Shaw (active 1771–1819), 1797. Mahogany and light wood inlays with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 98 1/2", W. 41 1/4", D. 23 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The design of the pediment is based on plate 57 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1793).

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, London, ca. 1772. Mahogany, satinwood and mahogany veneer, ebony and other unidentified inlays with beech and an unidentified soft wood. H. 29 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 16 3/4". This table is one of a pair remaining in Wye House. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Shaving table, probably Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1777. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 29 1/4", W. 19 3/4", D. 19 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Writing table, probably Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1773. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 33", W. 36", D. 17 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk, Eastern Shore or Annapolis vicinity of Maryland, 1765–1780. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 38", W. 35 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

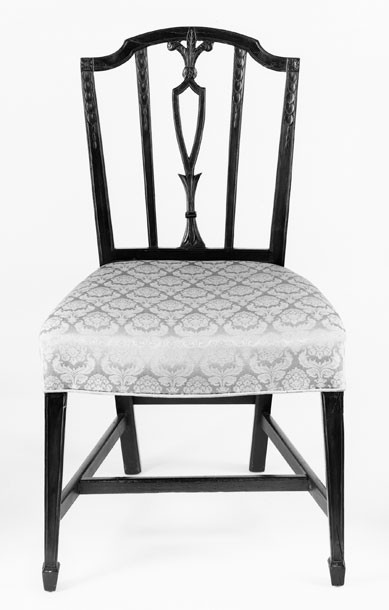

Side chair, England, ca. 1792. Mahogany with beech. H. 35 1/2", W. 21", D. 19". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Baltimore chair makers produced their own version of this splat design. Imported chairs like those ordered by Edward Lloyd IV probably influenced local production.

Side chair by Potthast Bros., Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1917. Mahogany. H. 40", W. 24", D. 19". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, England, ca. 1795, modified by J. W. Berry & Sons of Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1920. Mahogany. H. 37 1/2", W. 22", D. 20". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Silver and glass plateau by William Pitts and Joseph Preedy with alabaster figures, London, 1792–1793. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The three sections shown here are 52" long. With the two missing sections in place, the plateau measures 89 1/2".

Chest of drawers, England, ca. 1790. Mahogany and light wood inlay with oak and an unidentified soft wood. H. 35", W. 37", D. 22". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

John and Josiah Boydell, Richard III Act V Scene II, London ca. 1792. Etching and engraving on wove paper. Frame dimensions: 22 1/2" x 30 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the print illustrated in fig. 39. The inscription indicates that the print was part of a shipment to Edward Lloyd IV.

Balls for lawn bowling, England, 1785–1800. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the graveyard at Wye. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the graveyard at Wye. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Greenhouse at Wye, Talbot County, Maryland, 1740s and 1786. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Billiard table by John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1800. Mahogany and light and dark inlays with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 38", L. 139 1/2", W. 72 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Jonathan Fairbanks after Charles Willson Peale, The Edward Lloyd Family, 1959. Oil on canvas. 43 3/4" x 52". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

John Beale Bordley (1800–1882), Governor Edward Lloyd V, Maryland, 1828. Oil on canvas. 28 3/4" x 23 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Secretary, Baltimore, Maryland, 1790–1800. Mahogany and light and dark wood inlays with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 43", W. 42", D. 22". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Clothes press, probably by James Martin, Baltimore, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 82 1//2", W. 53 3/4", D. 24". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, Baltimore, Maryland, 1790–1800. Mahogany and light and dark wood inlays with white pine, oak, and yellow pine. H. 31 1/2", W. 42 1/2" D. 21" (closed). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, Baltimore Maryland, 1790–1800. Mahogany and light and dark wood inlays with white pine, oak, and tulip poplar. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One of the inlay woods is Botany Bay oak, an exotic from Australia.

Armchair attributed to William Singleton (active 1790–1803), Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1800. Mahogany and light wood inlays with tulip poplar, ash, and maple. H. 38", W. 21", D. 19". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Card table with decoration attributed to John and Hugh Finley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1808–1815. Tulip poplar with oak, white pine, and maple. H. 28 3/4", W. 36", D. 18". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornice by John and Hugh Finley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1828. Tulip poplar. H. 8", L. 59". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The festoon is missing.

End of a three-part dining table attributed to Edward Priestley (active 1801–1837), Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1812. Mahogany with tulip poplar and oak. H. 28 1/2", W. 56 3/4", L. 164" (with all sections assembled). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sofa attributed to Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1812. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 35", W. 96", D. 24 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1812. Mahogany with white pine, tulip poplar, oak, and beech. H. 28 3/4", W. 36", D. 17 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Circa 1915 photograph showing a sideboard attributed to Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1810–1815. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pair of knife vases, England, ca. 1800. Mahogany with oak and an unidentified conifer. H. 29", Diam. 12 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Writing table attributed to Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1810–1815. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine; blue baize writing surface. H. 36", W. 36", D. 17 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Section of handrailing by Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1826. Mahogany. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chamber table, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1825. Mahogany with cedrella, white pine, and tulip poplar. H. 33", W. 26", D. 22". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Mantle clock, France, 1810–1820. Bronze, brass, steel, glass, enamel, and silk. H. 14 1/2", W. 11", D. 4 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Baltimore, Maryland, 1795–1810. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 39 1/4", W. 39 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest is one of four that remain in Wye House.

Sideboard table and liquor case by Edward Priestley, Baltimore, Maryland, 1827. Sideboard table: Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine; Pennsylvania clouded limestone. H. 42 3/4", W. 62", D. 26 3/4". Liquor case: Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 20 1/4", W. 26 1/2", D. 17 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Carved heads like those on the table are illustrated on plate 57 of Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807).

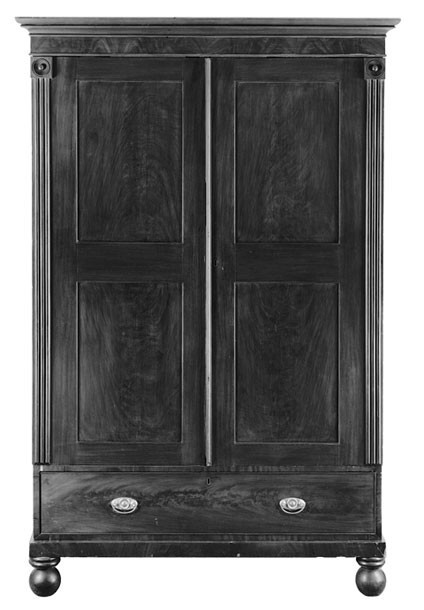

Wardrobe, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1835. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 82", W. 54", D. 23 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

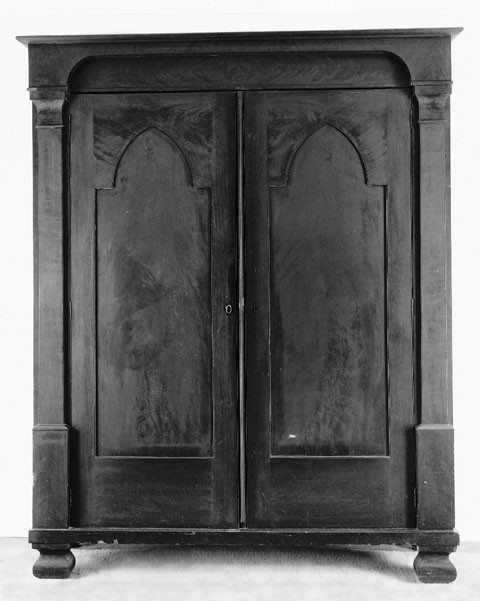

Wardrobe, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1825. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 80", W. 80", D. 20". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wardrobe, Baltimore, Maryland, 1835–1845. Mahogany and rosewood inlay with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 86 3/4", W. 57", D. 21 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wardrobe, Baltimore, Maryland, 1835–1845. Mahogany with white pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 84 1/2", W. 66 1/4", D. 21". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

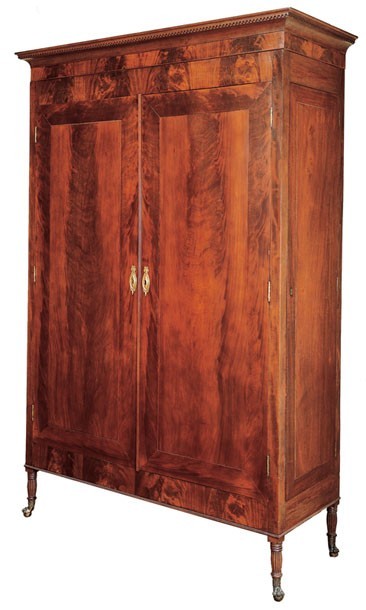

Armoire, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1825. Mahogany with cypress, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 90 1/2", W. 56 1/2", D. 21 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, possibly by Tweed & Bonnell, New York, 1835–1840. Mahogany. H. 34", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard table, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1835. Mahogany with tulip poplar, oak, and white pine; marble. H. 40", W. 56", D. 24 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rocking chair, probably Talbot County, Maryland, 1830–1840. Maple with oak. H. 46", W. 28 1/2", D. 33". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the north side of Wye House. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left arm of the rocking chair illustrated in fig. 73.

Detail of the right arm of the rocking chair illustrated in fig. 73.

Bedroom suite, Hart, Ware & Co., probably Baltimore, ca. 1855. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Hart, Ware & Co. maintained warehouses in Philadelphia from 1852 to 1854 and in Baltimore from 1855 to 1859. The suite has painted decoration in imitation of mother-of-pearl.

Objects are what matter. Only they carry the evidence that throughout the centuries something really happened among human beings.

—Claude Levi-Strauss

The survival of objects can be the result of either random or purposeful acts, whereas collections are by definition intentional. Most institutions have mandates and policies governing acquisitions, but their collections invariably reflect the interests and goals of successive curators, administrators, and donors. In contrast, private collections generally embody the tastes, interests, and aspirations of one or two individuals. Groups of objects acquired and preserved by consecutive generations of a single family are often described as “collections,” but they are actually assemblages because each generation reassesses and reorders objects and ephemera based on their own views regarding aesthetics, personal and family identity, historical significance, and sentiment. By revealing what specific consumers and their progeny deemed important and valuable, family assemblages often represent a more direct and more informative link with the past than do institutional and private collections.[1]

The furniture and furnishings of the Edward Lloyd family of Wye House (fig. 1) in Talbot County, Maryland, provide a unique opportunity to consider possessions that descended in an important American family. These objects raise several intriguing questions: Where, how, and why did their original owners acquire them? In what context were these objects used, and what do they say about the Lloyds’ wealth, tastes, social status, and self-perception? Why do these objects survive?

The history of the Lloyd family of Maryland began in 1659, when Edward Lloyd I (ca. 1610–1696) acquired 3,500 acres of land in Talbot County with the intention of establishing a tobacco farm. He named the property and the river adjacent to it Wye, after the Wye River in his native Wales. Edward I and his descendants accumulated power and money through political positions, the establishment of lucrative trade routes, and politically and socially advantageous marriages. By the 1770s, the Lloyds were one of the wealthiest and most powerful families in America.[2]

Built in 1787 by the fifth proprietor, Edward Lloyd IV (1744–1796), the present Wye House is presumably the fourth house built on the property. The previous ones fell victim to their proprietor’s desire to build a newer and more current residence. Just as Edward IV’s Wye house is the only dwelling surviving on the estate, the furniture that remains there is merely a fractional representation of what each proprietary family owned. For at least four generations (1718–1834), elder sons rose to power in the wake of their father’s death. They dispersed possessions to siblings, purged vast quantities of household goods, and bought anew. Successive generations used the cultural criterion of their own time to decide what to save and what not to save from the patrimony of previous generations. Throughout this period, the old furnishings preserved by the Lloyds and the new objects acquired by each patriarch served as vehicles for conveying power and social status and defining respective proprietorships.

Financial reversals contributed to the survival of some furnishings and the loss of others. By the 1850s, income from agricultural products grown at Wye had declined, reducing the family’s ability to maintain the house and outbuildings and acquire new furnishings and interior decorations. Although the Lloyds were less active consumers during the mid-nineteenth century, they remained intensely interested in their family’s legacy. These sentiments continued long after the Centennial, propelled by the colonial revival and the Lloyds’ awareness of their place in local and national history.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, debts at Wye were mounting, and many buildings on the property were in dire need of repair. The Lloyds had sold thousands of acres of land since the Civil War, but the proceeds were quickly exhausted. In 1906, Wye ceased to pass from father to eldest son when Edward Lloyd VIII (1857–1948), a commodore in the United States Navy, realized that he could not afford the taxes due upon the death of his father Edward VII (1825–1907). To maintain family control of the estate, Mary Donnell Lloyd (1865–1943)—the wife of Edward VIII’s younger brother Charles Howard Lloyd (1859–1929) (fig. 2)—purchased Wye House, its outbuildings and contents, and several thousand acres of land from Edward VII for $2,726.80 with money she had inherited from her family. Charles and Mary lived in Baltimore, residing at Wye House only seasonally. In 1943, their daughters Joanna Leigh Lloyd Singer (1895– 1972) and Elizabeth Key Lloyd Schiller (1897–1993) inherited the property, and Elizabeth and her husband Morgan B. Schiller moved there. Joanna’s daughter, Mary Donnell Tilghman (neé Singer) (b. 1919), inherited Wye in the 1990s and has used the latest and most careful methods of conservation to preserve the house, its outbuildings, and its furnishings.[3]

Although early proprietors routinely sold household goods through auctions and direct transactions, Charles Howard Lloyd, his wife Mary, and their daughter Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller were the most aggressive. Their efforts to preserve and restore Wye House were strongly influenced by colonial revival attitudes, which tended to romanticize the past. Charles, Mary, and Elizabeth made significant strides in improving the appearance of Wye House and oversaw the division of objects to Charles’ seven siblings after Edward VII died and sold unwanted furnishings as well. To re-create a semblance of the house’s colonial grandeur, they kept only what they perceived to be “true antiques” and replaced objects not fitting this criteria with colonial revival reproductions made by the Potthast brothers in Baltimore. The fact that the furnishings surviving at Wye House endured so many generations of taste and perception makes them even more rare, more evocative, more iconic.[4]

A strong tradition of patriarchy and primogeniture allowed Wye to descend from father to eldest son into the twentieth century—when ownership passed to the second son, and then to his two daughters—and the property remains in the possession of the eleventh generation today. Because furniture and other decorative arts associated with the Lloyd family have not entered the public domain, they have not captured the attention of scholars to the same degree as those that descended in many less influential families. It was, after all, the Lloyd family’s wealth that purchased the lavish and well-documented furnishings of John (1742–1786) and Elizabeth (Lloyd) (1742–1776) Cadwalader.[5]

Edward Lloyd III

Edward Lloyd III (1711–1770) is often remembered today as the wealthy father-in-law of Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader (1742–1786), but in the eighteenth century he was a prosperous planter and a stalwart member of the Maryland General Assembly and Governor’s Council who supported Tory politics with diehard fortitude. Edward III’s death in January 1770 spared his family from the political, financial, and social demise that befell other Maryland loyalists after the revolution. His will, written eighteen years earlier, left half of his considerable estate to his eldest son Edward IV (1744–1796) (fig. 3) and divided the remaining half equally beween his youngest son Richard Bennett (1750–1787) (fig. 4) and his daughter Elizabeth or her husband (fig. 5). This document conflicted with Edward III’s verbal, bedside instructions that his estate be divided in equal thirds. The discrepancy between the written and oral mandates ignited a major quarrel, which played itself out in heated correspondence between Edward IV and John Cadwalader, who represented Elizabeth’s and Richard’s interests as well as his own. By early 1771, Edward IV succumbed to his angry siblings and agreed to divide the estate equally between the three heirs. The only documents pertaining to the house and furnishings of Edward III are two inventories, though neither may be complete. His probate inventory lists objects room by room and notes their values, and a private inventory designated who inherited what by the initials “JC” (John Cadwalader), “EL” (Edward Lloyd IV), and “RL” (Richard Bennett Lloyd).[6]

Both of Edward III’s inventories begin by listing his lavish silver equipage, all procured through London agents and lending a palpable reminder of the Lloyds’ London-based wealth. The rooms are designated by function, color, and location, except for the bedrooms, which are identified by the names of family members who traditionally slept there. It is clear that furniture had been shuffled and removed by the heirs since the parlor contained no chairs and the dining room contained no table.[7]

John Cadwalader received most of the furnishings in the large bedroom over the passage, designated “The Colonel’s” (Edward III’s). This room contained a high-post mahogany bedstead with blue silk furniture, matching window curtains, a bottle stand and basin, two Wilton bedside carpets, prints, a settee bed, a dressing table with a cover and corresponding glass, and a pair of andirons with shovel and tongs. The only object that Edward IV received from his father’s bedroom was a close stool easy chair valued at £4.8.[8]

Richard Lloyd inherited the contents of the small passage, two bedrooms, and the dressing room over the dining room. The passage furnishings included two settees with covers, a large round table, a tea table, a breakfast table “eight square,” two floor mats (one large and one small), a large old map, and thirteen paintings. A small mahogany bedstead with furniture, two dressing tables with glasses, a japanned tea table, six chairs, a bottle stand, and two pairs of andirons with shovels and tongs were in the bedroom over the parlor and the dressing room over the dining room. The other bedroom, formerly occupied by Richard’s mother Anne Rousby Lloyd (1721–1769), had a variety of expensive furnishings: a mahogany bedstead with yellow silk furniture, two matching window curtains, six chairs with yellow silk damask “bottoms,” two armchairs, a chimney glass, a japanned cupboard, two brackets with porcelain pots painted with flowers, a print of John Wilkes, a mahogany stand, and a fire screen. Richard subsequently sold the settees with covers from the passage and the side chairs and one armchair from his mother’s bedroom to Edward IV.[9]

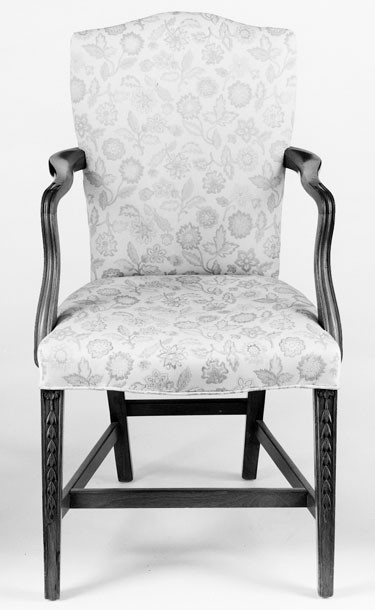

An English walnut armchair (fig. 6) in Wye House may be the latter seating form. It appears to date about 1760, which is too early to have been commissioned by any of Edward III’s children. Edward Lloyd III’s inventory lists an armchair valued at £10, an amount sufficient for an example with an upholstered back, seat, and arms. This armchair may also be the “large” one valued at £2.5 in the 1796 inventory of Edward IV. Referred to as “cabriole,” “French,” or “elbow” chairs in English design books, such armchairs were considered appropriate for both parlors and bedrooms.[10]

With the exception of the silk window curtains, which went to Edward IV, all of the parlor furnishings passed to the Cadwaladers. The couple received a large looking glass, a chimney glass and two sconces, a marble slab (presumably with a wooden frame), an old carpet, and a pair of andirons with shovel and tongs. Edward IV inherited the contents of the dining room and “Great Passage.” The dining room furnishings included two large gilt pier glasses, two silk damask window curtains, twelve chairs with silk bottoms and covers, four paintings, two fire screens, a tea table, a japanned tea table, a card table, four flower pots on brackets, and a pair of andirons with shovel and tongs; and the passage had a large and a small painted and gilt screen and eight flag bottom chairs.[11]

Random furniture not considered as part of a suite or for a specific room appears separately in the inventories. Cadwalader received ten mahogany side chairs and two mahogany armchairs with carpet bottoms, a Wilton carpet, and a shagreen case with silver handled knives and forks. Richard Bennett Lloyd inherited six chairs with damask bottoms, a broken mahogany card table, a broken tea table, a broken round table, mattresses, and a Wilton carpet. Edward IV received a sideboard table, a sideboard, a bureau, two leather armchairs, eight chairs with yellow damask bottoms, two fire screens, two sets of silk window curtains, an old clock, a Wilton carpet, and a shagreen case with silver mounts and five bottles. The three heirs divided twenty “common” and “low mahogany” beds and mattresses.[12]

A tall clock case at Wye House (fig. 7) has an eight-day movement by English clockmakers Daniel Quare and Stephen Horseman, who were in partnership from 1709 to 1720. This movement probably came from the “old clock” inherited by Edward IV, who replaced the original case with a more up to date, locally made one. The date range attributable to the movement suggests that the original owner was Edward II (1670–1718). Family photographs indicate that the clock has been secured to the passage wall since at least the late nineteenth century.[13]

The proceeds from two auctions recorded in Edward III’s estate ledger reveal that his heirs sold unwanted household furnishings. Each heir received £478.8.11 from a sale held in Philadelphia on September 6, 1770, and Edward IV and Richard received £113.9.2 from a sale of their unwanted goods held in Annapolis a year later. The Annapolis auction included textiles, kitchen utensils, chinaware, foodstuffs, and furniture, although only “a looking glass” was specified. Buyers from various social and economic strata vied for these goods. Among the successful bidders were royal governor Robert Eden (1728–1804), architect William Buckland (1734–1774), silversmith William Farris, ship captain, merchant and cabinetmaker Joseph Middleton, cabinetmaker Archibald Chisholm (d. 1810), cabinetmaker William Tuck, the Lloyds’ agent Arthur Bryan, merchant Richard McCubbin, and Thomas, “the servant man at the Middleton’s.”[14]

Many of the furnishings retained by the heirs document Edward III’s patronage of London tradesmen and his and his progeny’s familiarity with mid-eighteenth-century, European court styles. Silver served as one of the most potent symbols of the Lloyds’ wealth, social status, and taste. Much of the equipage listed in Edward III’s inventory was given to later generations of Lloyds, most often as wedding gifts. Of the silver that survives, two pieces are remarkable for their ownership and survival in an American context. The large tea waiter, or salver, valued at £242 features a cast rim with decorative allusions to the Lloyds’ wheat farming and an elaborately engraved “shield” with the arms of Lloyd impaling Rousby (figs. 8, 9). London silversmith Jacob Marsh made the waiter in 1754, but the name of the engraver is not known. The appraiser’s assessment of this monumental waiter was more than twice what Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck charged John Cadwalader for making eighteen major pieces of furniture, two window cornices, and two knife trays, and performing sundry repairs and services between October 13, 1770, and January 14, 1771. Maryland and Pennsylvania currency had almost equal value during the early 1770s. Besides effectively conveying the Lloyd family’s wealth, the waiter is steeped in lore. Family tradition maintains that during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries newborn Lloyd children were placed on the salver and presented to their father.[15]

Edward III’s inventory also notes that Richard Bennett Lloyd sold Edward IV a bread basket for £88. Made by John Wirgman in 1754, this imposing object (fig. 10) also has trophies pertaining to wheat farming. The reticulated nautilus shape alludes to fertile ground—the source of Edward III’s immense wealth—and the handle depicts the goddess of the harvest, Demeter (Greek) or Ceres (Roman), holding a shield engraved with the Lloyd coat of arms. John Cadwalader and Richard Bennett Lloyd divided a set of four large candelabra, each of which held twelve candles and had sixteen “savealls.” None of these objects are known to have survived, nor did they appear on any of the inventories of Edward III’s heirs. Given the fact that they were valued £118 each, the candelabra must have rivaled the magnificence of Edward III’s surviving silver.[16]

Numerous English, French, and Chinese porcelain dining services complemented Edward III’s silver, but only the tobacco leaf set remains at Wye (fig. 11). Comprised of several hundred pieces, this service was described as “Ribbd,” “Enameld,” and “Enameld china” in his inventory. Edward IV inherited one-third of the tobacco leaf porcelain and purchased the remaining two-thirds from Cadwalader and Richard Bennett Lloyd. No other porcelain, either useful or ornamental, survives from the elder Lloyd’s proprietorship.[17]

Unlike most of his peers, Edward III controlled every facet of his business—thousands of acres of land, hundreds of slaves, several mills and drying houses, and a fleet of schooners that transported wheat and tobacco from Maryland to London. The family’s connection to the water and involvement in transatlantic commerce may have prompted Edward III’s heirs and their progeny to preserve a pair of deck cannons (fig. 12) from his private schooner. Edward III used the cannon to “thunderously report” his arrival in port as did Edward IV, V, and VI, the latter having transferred the two pieces of artillery to their own private schooners. According to family tradition, the cannons were last discharged in 1865 when Admiral Franklin Buchanan (1800–1878), who was married to Edward V’s daughter Anne Catherine Lloyd (1808–1892), repelled Union deserters attempting to burglarize Wye House.[18]

The dispersal of Edward III’s estate and redecorating by generations of his extended family has left only a small amount of furniture that can be associated with his proprietorship. At present, it is unclear where the furniture inherited by Richard Bennett Lloyd and the Cadwaladers ended up. It is possible that John and Elizabeth decorated their Kent County, Maryland, estate—Shrewsbury Farm—with some of her father’s furnishings. At the very least, Edward III and Anne’s interiors inspired those that the Cadwaladers created in the Philadelphia townhouse Edward III urged them to purchase. The silk curtains and upholstery fabrics in John and Elizabeth’s principal first floor rooms were yellow and blue like those in Wye House. Edward III and Anne’s color choices may have been inspired by the Lloyd family coat-of-arms, which is azure and gold (figs. 13, 14). These colors would also have resonated with John Cadwalader, whose crest features a gold cross formé fiché against an azure ground. The Cadwaladers also had the ten mahogany side chairs and two armchairs they inherited recovered by Philadelphia upholsterer Plunkett Fleeson, and they augmented the Wilton carpets from Wye House with others purchased through their London agent Mathias Gale. Although the side chairs and armchairs are not known to have survived, it is conceivable that they served as models for the well-known ribbon-back set that the Cadwaladers commissioned about 1769 (fig. 15).[19]

The Wye House of Edward Lloyd IV

After the revolution, Edward IV became less active in politics and moved from Annapolis to Wye in hopes that country life would remedy the gout that debilitated him. Like other enlightened men of his era, he studied art and architecture and amassed a large and useful library. Many of the architectural design books he acquired remain in his house today. In fact, entries in Edward IV’s ledgers suggest that he designed and supervised the construction of the surviving residence at Wye.[20]

In 1781, Edward IV instructed his overseer James Burke to move the contents remaining in his father’s house to Forrest Plantation, a neighboring Lloyd plantation. These items included a writing desk with papers, several mahogany chairs, a large mahogany couch with a check cover, a mahogany stand, two large gilt pier glasses, two “fincured” knife cases, window blinds, tea china, glass, chimney-piece ornaments, andirons, fender grates, shovels and tongs, bird cages, a drum and a pair of drum sticks, six guns and six barrels, and nine pieces of flagstone. The following year, Edward IV demolished his father’s residence and commissioned engineer Charles Gardiner to survey the site to establish a perfect north-south axis for his new Wye House (fig. 16). Entries in Edward IV’s ledgers from 1781 to 1788 document expenditures for building materials—wood for the framing and weather boarding and brick (some fired at Wye) for wall filler. On March 13, 1787, joiner William Eaton received £9.3.4 for “shifting the studs of the main house to prepare for weatherboarding.”[21]

Construction must have been nearing completion the following year. A docket from Edward IV’s Baltimore agent dated March 1788 lists furnishings and other goods shipped aboard the former’s schooner to Wye. Included were powder yellow, boiled oil, raw oil, whiting, turpentine, fat oil, vitriol, litharge of gold, twenty books of gold leaf, twelve paint brushes, and nine other paint tools, presumably for re-gilding the pier glasses moved from Forrest Plantation to Wye House. Formerly thought to date from the late eighteenth century, these remarkable glasses (figs. 17, 18) show how profoundly Edward III’s furnishings influenced the material world of his children.[22]

The large north parlor in Edward IV’s residence was designed specifically to accommodate the pier glasses, which are the same height, but differ in width (fig. 17). Although earlier scholars believed that these objects were neoclassical imports, documentary evidence and microscopy suggest that they are the two pier glasses Edward IV inherited from his father’s dining room and that the materials listed in the docket were for re-gilding them. Leaf and ribbon appliqués similar to those on the Lloyd examples are illustrated in architectural design books such as William Jones’ Builders Companion (1739) and occur on British looking glass frames from the second quarter of the eighteenth century. The guilloche borders of the pier glasses also have architectural parallels. Plate 78 of Batty and Thomas Langley’s The Builder’s Jewell (1741) shows a popular variant in the upper right corner (fig. 19).[23]

As centerpieces of the most prominent room in Wye House and unable to be closeted, the pier glasses survived the purges of Edward IV and seven consecutive generations of his family. From the late 1780s to the present, the Lloyds have referred to this room as the “parlor,” but Edward IV and his descendants also used it for large dinner parties. With the dining table placed on the north-south axis and the pier glasses reflecting the candlelight, the room undoubtedly made a dazzling impression. The glasses hung just above the chair rail with their tops canted forward until 1823 when Edward V installed a wider cornice and lowered them. The distance between the two sets of screw holes on each frame equals the amount that they were lowered and the amount they presently hang below the chair rail (see figs. 17, 18). Neither glass appears to have been moved since 1823.[24]

A third pier glass presumably obtained by Edward IV to complement the two he inherited from his father does not survive, but it is described in the younger Lloyd’s inventory as “a gilt frame looking glass...£15.” The value of this object and its listing adjacent to the “pair [of] large Gilt frame looking glasses...£100” suggests that all three were in the same room. Edward V’s account and subsequent dispute with the London mercantile firm Thomas Eden, Christopher Court & Company also confirms the use of a third looking glass in the north parlor. In 1810, the former ordered “three” pairs of cut crystal girandoles to stand in front of the parlor glasses (see fig. 17).[25]

Edward V may have displayed the girandoles on tables in front of the pier glasses. The 1861 inventory of his son Edward VI documents this practice, as do later photographs of the north parlor of Wye House. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the D-shaped ends of a large classical dining table (see fig. 55) supported the girandoles while the other sections remained assembled for dining in the adjacent “withdrawing room.” Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller replaced the D-ends with elliptical table sections (see fig. 17) she rescued from a barn loft. These sections may comprise all or part of one of the seven dining tables belonging to Edward IV.

Since the proprietorship of Edward Lloyd III, the pier glasses have defined the most important room in Wye House. Given their presence and the fact that they dictated the placement of other furniture forms and lighting devices, it is remarkable that these fragile objects endured the refurnishing and redecorating of subsequent generations. For the Lloyd family, these pier glasses have always represented a tangible connection with the grandeur of their eighteenth-century past.

In the Wye Houses of Edward III and Edward IV, bedsteads also provided a framework for lavish displays of wealth, primarily in the form of imported textiles. Edward III and his wife Anne both had bedsteads with silk furniture that matched the window curtains in their respective bedrooms. Edward IV and Elizabeth had comparable fabrics. In 1780, they paid £720 for eighteen yards of pink silk ordered from France. In the early twentieth century, Charles and Mary Lloyd sold a large quantity of furniture including several bedsteads. Only one early bedstead (fig. 20) remains in Wye, having been rescued from a tenant house by Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller in 1950. Related to both British (fig. 21) and Philadelphia examples from the third quarter of the eighteenth century, it has gothic footposts and large Marlborough feet.[26]

Edward IV: Conspicuous Consumption

The inventories of Edward IV’s houses at Wye and Annapolis paint a picture of a man who proudly earned the appellation his descendants bestowed upon him—“Edward the Magnificent.” Excluding real estate, the value of his personal effects totaled £38,785.12.6, £11,000 of which were household furnishings (almost exactly ten percent of his entire wealth). Many of his possessions reflected personal interests, intellectual pursuits, and leisure activities. He had a library comprised of 2,500 volumes and owned a camera obscura, a mahogany compound microscope, surveying instruments, spy glasses, physics scales, a mahogany case of instruments for the recovery of drowning persons, several pairs of silver mounted pistols, 640 bottles of Madeira, 1822 bottles of sweet wine, sixty-nine pints of port wine, three demi-johns of apple brandy, a case of gin and brandy in cut glass bottles, and a cask of whiskey. He also maintained a park with sixty-one fallow deer and a small personal fleet consisting of barges, phaetons, and a schooner. The furniture in his residences included 103 side chairs, twenty-two armchairs, six settees, a sofa, nine Pembroke tables, seven card tables, six dining tables, five dressing tables, three writing tables, six washstands, three fire screens, eight bureaus, six desk-and-bookcases, six desks, one secretary bookcase, two bookcases, four clothes presses, and three sideboards. Although Edward V sold £10,956 worth of his father’s household goods at auction in Baltimore in 1797, many of the finest furnishings acquired by Edward IV remain in Wye House along with more utilitarian objects that served the needs of Lloyd descendants’ daily lifestyles.[27]

Immediately after his father’s death, Edward IV and his wife Elizabeth (Tayloe) (1750–1825) set up residence in Annapolis, a town noted for “the quick importation of fashions from the mother country.” The couple purchased a house that Annapolis lawyer Samuel Chase (1741–1811) had begun to build and hired London-trained, house joiner William Buckland to design their new home (fig. 22). Buckland had previously worked on Mount Airy, the home of Elizabeth’s parents in Richmond County, Virginia. To augment Buckland’s workforce, Edward IV imported carvers and plasterers from London. The result was the first three-story structure in Annapolis—an imposing residence with interiors that combined late baroque massiveness with the delicacy of the new neoclassical style. Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Edward IV’s distant cousin, estimated that the interior details and furnishings comprised a substantial portion of the total cost. The townhouse “has cost ye Colonel upwards of £3000 cury and I think when the offices are finished and the house compleatley furnished it will cost him £6000 more.”[28]

Although Edward IV was loyal to the revolutionary cause and the first member of his family to sell agricultural products to American markets, his cultural and economic ties to London spurred his desire to decorate his townhouse, and later residence at Wye, like the homes of English nobility. Unlike his brother-in-law John Cadwalader, who procured fashionable furnishings from Philadelphia artisans, Edward IV ordered most of his furniture and interior decorations from London agents. Because Elizabeth Tayloe Lloyd retreated to Annapolis shortly after her husband’s death, the furnishings in the townhouse were not dispersed until her death in 1825.[29]

Edward IV ordered twelve British armchairs (fig. 23), often referred to during the period as “French chairs,” for his Annapolis townhouse. Sets of armchairs were ubiquitous in the homes of English and French nobility and were intended to subordinate issues of precedence. The wooden elements of the Lloyd chairs, as well as those of the settee that once accompanied them, were originally painted white with gilt decoration, and each piece in the suite had its seat, arms, and back (both front and rear) covered in silk. These seating forms are described in Edward IV’s 1796 inventory as “12 Arm Chairs with silk damask lining...£45” and “1 large Settee with do. do. do....£25.” Thirteen “stuff covers” valued at two pounds protected the upholstery on the chairs. Edward IV moved the suite to Wye in 1791, but Elizabeth took it back to Annapolis five years later. After Elizabeth’s death in 1825, her son Edward V returned the chairs to Wye House, where they remain today. Although the rococo style of these chairs was in many respects the antithesis of the late classical taste that held sway during Edward V’s proprietorship, he clearly appreciated the historical and family associations of these important seating forms. The same can be said of his son Edward VI (1798–1861), who hired Baltimore cabinetmakers John and James Williams to make a new settee (see fig. 17) in 1844. The original must have been damaged or destroyed earlier.[30]

The London bureau bookcase and bookstand illustrated in figures 24 and 25 were also among the original furnishings of Edward IV and Elizabeth’s Annapolis residence. Dating from the 1750s or early 1760s, these imposing objects were probably wedding gifts from Edward’s parents, who gave a London silver tea service (Philadelphia Museum of Art) to Elizabeth and John Cadwalader when they married. With its scrolled pediment and lavish rococo carving, the bureau bookcase would have complemented the door friezes (fig. 26), chimneypieces, and other architectural details in the Lloyds’ townhouse. Edward’s ledger indicates that Buckland received £62.0.6 for ornaments in the large first floor parlor, which included bold, gadrooned door and window surrounds, carved trusses, and frieze appliqués with bird heads and leafage based on designs by British architect Abraham Swan. Buckland’s London-trained carver, Thomas Hall, was probably responsible for both the design and execution of this work. The practice of integrating furniture and interior architectural details was over a century old by the time the Lloyds began furnishing their townhouse.[31]

Like the silver and pier glasses commissioned by Edward Lloyd III, the bureau bookcase is one of the most extravagant and expensive London imports associated with an American owner. Although the leaves that rose from the scroll volutes are missing, the pediment design is related to that of a desk-and-bookcase illustrated on plate 78 in the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) (fig. 27). No piece of Chippendale furniture with an American provenance is known, but the design, construction, and carving on the Lloyd bureau bookcase suggest that it came?from the upper echelon of London’s cabinetmaking trade.

Like the aforementioned French chairs, the bureau bookcase and bookstand were physical manifestations of the Lloyd family’s wealth and taste. Edward IV moved both objects from Annapolis to Wye House, and his widow left them there when she returned to live in their townhouse. Later inventories and photographs of Wye indicate that during most of the nineteenth century, the bureau bookcase stood either in the “withdrawing room” to the left of the front door or in the “passage.” Edward V may have used this case piece primarily for display after receiving the desk-and-bookcase he ordered from Annapolis cabinetmaker John Shaw (1745–1829) in 1797 (fig. 28). Shaw made the latter example specifically to fit between the windows of the office to the right of the front door. It is forty-one inches wide, a dimension narrow in proportion to the overall height. Although Shaw used one of his shop patterns to lay out the pierced tympanum, he reduced the width to accommodate his patron’s specifications. This resulted in a somewhat awkward juncture of the cornice and scroll moldings (fig. 29).[32]

From the late eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century, the Shaw desk-and-bookcase functioned as the nucleus of business at Wye House. During that period, each proprietor used the desk for corresponding and record keeping, as indicated by the words “Bills” and “Receipts” written on two of the pigeonhole valances. Later members of the Lloyd family preserved the desk-and-bookcase as an heirloom and as an example of the refined work of an important Annapolis cabinetmaker. Shaw’s illustrious reputation emanated not only from his skill, but also from his frequent use of labels, a practice that ensured his notoriety among early antiquarians and regional historians.[33]

Few objects purchased by Edward IV and preserved by his progeny have received attention from decorative arts scholars. Between 1770 and 1788, Edward IV ordered a relatively restrained pair of London neoclassical card tables (fig. 30) for his Annapolis townhouse. Although the light and dark inlays and flat surfaces of these tables contrast with the asymmetrical carving and sweeping curves of the bureau bookcase and bookstand that Edward IV received from his father (see figs. 24, 25), these stylistically disparate forms complemented the interior architecture of the younger Lloyd’s townhouse. Most of the period carving in Edward IV’s townhouse is rococo, but the plaster ornaments made and installed by John Rawlings and James Barnes are predominantly neoclassical. These two London emigrés received £603.1.6 1/2 for their work, which was one the earliest expressions of neoclassicism in the colonies.[34]

The card tables stayed in fashion during the decade following Edward IV’s death. His 1796 inventory lists “2 elegant fincerd card tables” valued at £21. Both remained at the Annapolis townhouse in the same room as the French chairs (see fig. 23) until Elizabeth Tayloe Lloyd’s death in 1825 and were among the furniture Edward V chose to keep and return to Wye House.[35]

Like his father, Edward IV clearly imported most of his formal furniture from London. Both men sold their agricultural products in England, thus a good deal of their wealth was based there. Although most of the surviving furnishings associated with Edward III and Edward IV are British, the sheer quantity of furniture listed in their inventories indicate that they also patronized American artisans. Edward IV probably purchased a higher percentage of American-made objects than his father. The younger Lloyd was the first proprietor to exploit the colonial market by selling tobacco and grain in Annapolis beginning in 1770 and eventually adding Baltimore by the late 1770s as it eclipsed the capitol in economic, social, and cultural importance.

The shaving table illustrated in figure 31 may be from the shop of Archibald Chisholm, an Annapolis cabinetmaker patronized by Edward IV during the late 1770s, when he and Elizabeth lived in town. Were it not for its yellow pine and tulip poplar secondary woods, this object could easily be mistaken for a British shaving table from the 1760s or 1770s. Chisholm immigrated to Annapolis in the early 1760s and may have trained fellow Scot John Shaw, with whom he formed a partnership in 1772. Although no documented furniture by Chisholm is known, it is likely that he introduced some of the urban British designs and construction details now associated with Shaw’s work. The shaving table and two chamber stands remained in use in Wye House until Charles Howard Lloyd installed plumbing in 1917. Clearly, these objects survived because they were useful.

The same can be said of the writing table shown in figure 32, which later generations of the Lloyd family used for storing silver flatware. Edward IV’s inventory lists a “mahogany writing table with six drawers” valued at £4.10 between a “Mahogany [bureau] with glass doors and bookcase a little out of repair...£25” (fig. 24) and a “reading table stand” valued at £4.10 (fig. 25). The sequence of entries suggests that this relatively simple writing table stood in the same room with two overtly rococo forms. Although this may seem unusual from a modern perspective, eighteenth-century patrons often combined the lavish with the simple. Many wealthy patrons from the Chesapeake Bay region ordered “neat and plain” furniture from British merchants as well as from local tradesmen. The “neat and plain” style is best understood as restrained, structurally sound, and correct in proportion and adaptation of classical detail. Even leading British designers like Thomas Chippendale illustrated and produced forms in this mode.

Edward IV’s inventory also listed several walnut desks. A Maryland example (fig. 33) in Wye House probably dates from his proprietorship and relates to other desks found on the Eastern Shore. Although the Lloyd desk could have been made on the Eastern Shore, it is also possible that Edward IV purchased it from a cabinetmaker in the Annapolis area and subsequently brought it to Wye. With its old-fashioned interior, this desk would most likely have served as “backstairs furniture.” Edward IV’s brother-in-law, John Cadwalader, commissioned simple walnut furniture from Philadelphia cabinetmaker William Savery for secondary spaces in his townhouse. The Lloyd desk fits perfectly in a small niche in a second floor bedroom once occupied by several members of the Wye House community, in particular a children’s tutor. Edward IV’s gardener, whom they brought over from England, may also have used the desk. It has resided in the same bedroom for more than a century.[36]

Beginning in the 1790s, Edward and Elizabeth became much more active in furnishing Wye House. In orders placed with their London agents, Edward specified furniture “procured of the best and most fashionable Materials.” Correspondence survives for several large orders, six in 1791, six in 1792, and one in 1793. On August 6, 1791, he requested that Thomas Eden send a variety of foodstuffs, medicines, furnishings, and objects and animals associated with the leisurely activities of a wealthy planter:

| 2 best Pastelion Velvet Caps wth Gold Band and Tassels | |

| 14 handsome Mahogany Chairs for a Dining Room Covered wth the best black Morocco leather. NB. two of these chairs to be Armed Chairs | |

| Small Skiff wth two sets of Oars and Rudder to the Skiff. See Capt. Dunnes as to this Boat | |

| 2 dozen Sets of the best Guitar Strings | |

| The Works in English of Emmanuel Swedenburg | |

| 2 doz. Hills Pictorial Balsome | |

| 2 do. Papers of Dr. James’s Powders—NB None must be sent but that are Warranted genuine | |

| 2 dozen finest handsome coloured bordered Cambric Hankerchiefs | |

| 2 Pieces of Cambric cash Sterling 3 Pr Yds | |

| 2 Do finest Linen Cash Sterling 4/ Yard | |

| 2 Do Do Do " 5/ Pr do | |

| 100 Wt. of best and Choicist Pickle Beef | |

| 2 Dozen best do do Tongues | |

| 1 Pot Bird Lime | |

| 1 Puk of fresh Canary Bird Seed and graval do do do | |

| 4 Canary Birds Paired | |

| a small Collection of the best English Birds | |

| 1 double Gloucester Cheese} | |

| 1 do Cheshire D} Send none but of the finest Quality | |

| 12 dozen finest old Porter in Casks of four dozen each well secured NB. Attend to this Porters being of the best Quality | |

| 2 Thorough broke springing Spaniel Dogs — NB They must be under perfect Command as none others will do ~ Collars with my Name Must be sent with them. | |

| a handsome fashionable Mahogany Settee covered with the black Morocco leather six feet long and the width in Proportion—with two cushions or Pillows at each end of black Morocco leather to suit the 14 chairs ordered above—NB. The Pillows to be filled with the Softist and finist Materials, the Settee and bottoms of the Chairs Neatly Stuffed with the best Curled hair and it is hoped that Particular Attention will be paid in executing this order as will the whole of the above Articles inclosed in this invoice | |

| 2 Chests of the finist Sweet Oranges from Lisbon well and securely put up | |

| 1/2 dozen dog Leather Collars Strongly fitted for Padlocks with my Name Thereon | |

| 1/2 dozen good Strong Padlocks and Keys for do[37] |

When Edward VIII conceded his birthright and sold Wye to Charles Howard Lloyd in 1906, he took the dining room chairs ordered from Eden (fig. 34). Charles replaced the twelve English neoclassical side chairs with two sets of six chairs (fig. 35) made by Potthast Brothers (active 1892 to 1975) of Baltimore. The Potthast chairs were based on a Philadelphia example from the 1760s formerly in the collection of Dr. William Crim, a famous Baltimore antiquarian. This model, commonly referred to as the “Crim chair,” was the most popular reproduction in the Potthast’s line. Not only were these Potthast chairs sturdier than the neoclassical ones they replaced, they were, in the eyes of Charles Howard Lloyd, more “colonial.”[38]

Numerous sets of six or more chairs are listed in Edward IV’s inventory, and while the set of twelve armchairs and one of the sets of dining chairs with morocco leather seats survives, parts of others were also preserved. Charles Howard Lloyd paid Baltimore furniture restorers J. W. Berry & Sons to modify several English chairs from Wye House for his daughter, Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller. One chair from an altered set has period arms, arm supports, legs, and stretchers. Its twentieth-century upholstered back and seat suggest that J. W. Berry & Sons replaced a damaged back and the seat rails with components that were more comfortable to modern sitters (fig. 36). An insurance inventory taken by Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller in 1948 describes the chairs as “made into usable chairs by Berry & Sons in 1920.”[39]

Other furnishings imported by Edward IV and Elizabeth fared better over the years. On January 17, 1792, they placed an order with Oxley Hancock & Co. of London that included a large quantity of furniture, clothing, and foodstuffs:

| 1 Handsome Mahogany Bedstead and Cotton Furniture Compleat of a drab or dark Coloured ground. The Cornice to be Painted Wood with two Window Curtains to Do The Chamber about 13 feet Pitch ready fixt with Cornice Pr" Pr" Pr" to the Window Curtains... } | |

| 1 Bed Bunt Bolster and two Pillows to fit this Bedstead. | |

| 1 Mattrass for Do of the best Materials:~ | |

| 1 Pair of the best and Softist Blankets for Do — NB. Send those Blankets of Extraordinary quality | |

| 1 best Counterpane for—Do ~~ | |

| 1 Dressing Table. Do Glass with drawers wth best Locks & Keys to Do~ | |

| 1 1/2 dozen Strong Mahogany Chairs to Do | |

| 1 1/2 dozen Cotton Covers for the Chairs to suit the Bed furniture and ramp; to take off and on — NB. Send as much of the Cotton as will cover a Chair seat & back} about 10 Yards with trimmings will be sufficient} | |

| 2 Chamber dressing Table Glass’s wth drawers | |

| a Handsome Mahogany Side Board Table Complete in every Respect | |

| a Sett of fashionable Elegant Ornaments to Place over Mantel of a Chimney Piece to Cost about 20 Guineas | |

| 1 ditto ditto to Cost about 6 Guineas | |

| Fashionable Ornamental decoration to set off a Dining or Supper Table, that will accomodate 20 People wth a Sketch of the Table with the Images Pr" Pr" Pr" thereon Plain and full Directions showing how the Ornaments are to be Placed there—NB. These decorations not to exceed 100 Guineas |

The sideboard table listed above does not survive, but a five-part plateau and twelve classical figures “to set off a Dining or Supper table” remain part of the Wye House furnishings (fig. 37). Described in Edward IV’s inventory as “1 Case with silver and glass Ornaments for a Table & 29 Alabaster Images...£75,” these objects show how he and his family emulated the most sophisticated European dining fashions. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, various members of the Lloyd family continued to use these decorations like their ancestors, arranging the figures to depict scenes from classical mythology.[40]

A chest of drawers with a linen slide under the top (fig. 38) may be the “dressing table” that Edward and Elizabeth purchased from Oxley Hancock & Co. in 1792. George Hepplewhite illustrated “dressing drawers” with linen slides and French feet in the first edition of The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788), but all of his designs included “a top drawer [with compartments for]...the necessary...equipage.” Edward IV’s inventory lists “1 mahogany dressing table with drawers inlaid” valued at £8.15; however, he may have owned more than one example since Oxley Hancock & Co. furnished him with “2 Chamber dressing Table Glass’s wth drawers.”[41]

In April 1792, Edward IV instructed Thomas Eden to send “Broderips finest tuned Organized Pianoforte,” an expensive instrument and a conspicuous symbol of wealth and refinement. Valued in the proprietor’s inventory at £75 with its music and chair, the piano survived until the twentieth century. Along with the piano, he requested a subscription:

For Boydells Prints of Shakespeare which have handsomely framed in Glass and forwarded as Published ~ Send also a Collection of the best Coloured and most approved Prints in elegant frames sufficient for a Withdrawing Room of about 20 feet square ~ It is particularly requested that some person of Judgement be employed in Selecting this Collection as none but the most pleasing and best impressions will answer ~ NB. Coloured Prints are Meant those that have a variety of Tints in the same Print in Water Colors.

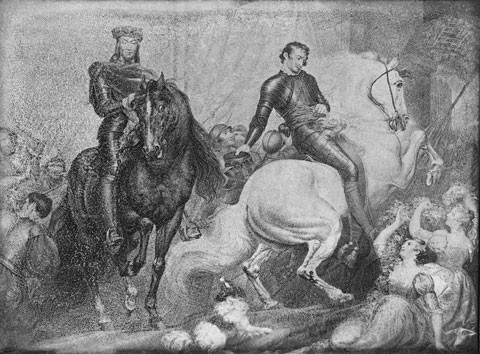

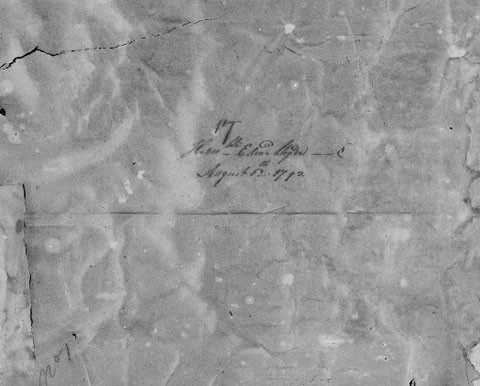

Both Edward IV and V ordered several sets of the Boydell brothers’ immensely popular prints. Ten prints depicting scenes from Shakespeare’s plays survive in their original gilt and paper lined frames, including one from Edward IV’s 1792 order (figs. 39, 40), whereas portfolios of loose prints remained in a large pine bookcase in the library at Wye House until the early twentieth century. Loose and framed prints are listed in the inventories of several members of the Lloyd family taken during the nineteenth century, and some are visible in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs of Wye House.[42]

Although Edward IV and Elizabeth were diligent in their efforts to build and furnish Wye, they found ample time to indulge their passion for formal gardening and outdoor leisure activities. Edward, for example, owned several sporting guns and pistols, badminton shuttle cocks, backgammon boards, lawn bowling balls, and a barn full of race horses that he imported from England and raced in Annapolis and at his own track along the Wye River. In 1792, he ordered from Thomas Eden:

a Marquis Sufficiently large to hold a dozen People and...[private] appartments for lodging sufficient for half a dozen People ~ Bedsteads and Beding Complete in every article Tables and Seats to accommodate a dozen People all of which to be so constructed as to be capable of packing up into as Small a Compass as Possible ~ it is intended to be used occassionally on Fishing Parties on the Shores of the Chesapeake Bay.

Out of all of Edward IV’s sporting equipment, only a few guns and the lawn balls (fig. 41), rolled on the green between the house and the greenhouse, survive.[43]

For Edward III, IV, and V the pursuit of leisure activities was a sign of refinement, gentility, and an enlightened mind—qualities the Lloyds were bred to possess and those that helped propel them to their social and political positions. The family’s private graveyard (figs. 42, 43) and greenhouse (fig. 44) define the boundaries of the garden, which evolved during the proprietorships of the aforementioned men. In the 1740s, Edward III built the central pavilion of the greenhouse, oriented on the north–south axis of the Wye House he built and his son later razed. Edward IV enlarged the greenhouse in 1786, when he paid William Eaton £148 for “repairing the G House and adding hot house wings.” The wings (or furnaces) kept his fruit trees warm during the winter.[44]

Although the greenhouse remained in use for decades, it eventually housed one of the most expensive and important pieces of furniture that descended in the Lloyd family—a billiard table that Edward V purchased from John Shaw for $150 on December 29, 1800 (fig. 45). Two weeks later the young proprietor paid Baltimore merchant James P. Maynard for balls and cue sticks—the first and only set that accompanied the table. This costly sporting equipage suited the lifestyle of Edward V, whose orders to London in the early years of his proprietorship included sterling silver cock spurs and “a fashionable sattin cloak with silver bear or any other most fashionable fur with a muff and toppet to suit.”[45]

The billiard table also speaks to the genteel tradition of gambling—a pastime at which all of the Lloyds excelled. In 1777, John Adams (1735– 1826) described Maryland as a place where “planters and Farmers...hold their Negroes...Convicts...[and] laboring People and Tradesmen, in such Contempt, that they think themselves a distinct order of Beings. Hence they never will suffer their Sons to labour, or learn any Trade, but they bring them up in Idleness or what is worse in Horse Racing, Cock fighting, and Card Playing.” Although Adams’ comments seem harsh, Chesapeake planters were imminently conscious of their place in society. Unrestrained by the prudish attitudes maintained by many of their northern counterparts, the scions of the elite participated in all sorts of gambling activities. In fact, gambling was so ingrained in Edward V’s lifestyle that he kept records of his opponents’ scores and registered the winnings from his billiard games in his ledgers as legitimate income.[46]

Billiard tables were present in the homes of other wealthy Americans in the early nineteenth century, but no example comparable to Edward V’s is known, much less one commissioned for use in a greenhouse. The fact that the billiard table was located there—away from the center of activity—during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may have contributed to its survival. By 1861, it had fallen into disrepair. Edward VI’s inventory taken in that year valued the billiard table at only $5. Later generations of Lloyd children, many of whom inscribed their names on the window surrounds and panes of the greenhouse, reminisced about playing underneath the relic. The table remained in the greenhouse until 1958 when Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller decided that the microclimate was destroying it and that it would never be restored. When Henry Francis du Pont, founder of the Winterthur Museum, expressed his interest in purchasing the table, Elizabeth Schiller negotiated for the return of Charles Willson Peale’s painting of Edward Lloyd IV and his family (fig. 3). The painting had descended to Edward’s daughter Anne (Lloyd) Lowndes (1769–1840), whose great, great grandson sold it to du Pont in the 1940s. Although du Pont refused to sell the original, he acquired the billiard table for cash and commissioned a copy of the painting (fig. 46) from Jonathan Fairbanks, at that time a student in the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture. To prevent Fairbanks’ painting from being confused with the original, the reproduction is eleven inches narrower and thirteen inches shorter. Much to the pleasure of Mrs. Schiller and her descendants, the copy is deceivingly fine and lends an air of ancestral presence to the interiors of Wye House. Other paintings that survive at Wye House include a Benjamin West portrait of Richard Bennett Lloyd (fig. 4) and four Dominc Serres marine paintings dated 1776.[47]

Edward V: Patriarch and Agriculturist

At the death of his father in 1796, seventeen-year-old Edward V (fig. 47) inherited over 20,000 acres of land, 320 slaves, the Annapolis townhouse, Wye House, and part of the furnishings of both residences. As the new family patriarch, Edward V also assumed responsibility for his mother and two unmarried sisters, Elizabeth (1774–1849) and Mary (1784–1859). Elizabeth subsequently married Henry Hall Harwood (1774–1839), and Mary married Francis Scott Key (1779–1843). On October 30, 1797, Edward V married Sarah (Sally) Scott Murray (1775–1854) of Annapolis, and fourteen months later the couple had their first child, Edward VI. During the same time frame, Edward V sold nearly £11,000 worth of his father’s household furnishings and undertook a major redecoration of Wye House.

Edward V was a celebrated equestrian, the youngest man ever elected Governor of Maryland (1809–1811), and a United States congressman (1805–1809) and senator (1819–1826). More than twice as much furniture survives from his proprietorship than that of his father and grandfather. Because the industrial revolution fostered an economy less conducive to slave-based wheat farming, Edward V left his son and six siblings an estate that was proportionally smaller than those received by earlier proprietors. Consequently, Edward VI did less redecorating and continued to use a large percentage of the furnishings acquired by his father along with the heirlooms of earlier generations. In 1836, Edward VI’s wife died prematurely, and his mother Sally resumed the role of proprietress. Sally was less inclined to make drastic changes to the home she and her husband had made, and she lived in Wye House until her death in 1854. By the time Edward VI died in 1861, the plantation economy that had fueled the Lloyd family’s lifestyle was one month away from its demise. In the wake of Edward VI’s death, his descendants’ concern about the consequences of the impending war eclipsed any desire to sell furnishings and redecorate.[48]

No public inventory of Edward V’s estate is known. A September 19, 1834, notation in the docket book of the Register of Wills for Talbot County stated that Edward V’s administrators posted a $500,000 bond in lieu of paying the taxes due on his estate and that “No inventory is to be returned in this case.” A small, private inventory of Wye House taken about 1834 describes some of the objects he owned, but it is skeletal at best.[49]

Unlike his ancestors, Edward V conducted most of his business in Baltimore, a city with a thriving cabinetmaking community capable of producing furniture that rivaled the finest imported wares. Edward V only purchased from London those items he deemed unobtainable from American craftsmen—silver cutlery, silk hose, shoes, certain flower seeds, subscriptions to Boydell’s Shakespeare prints, and the three crystal girandoles mentioned earlier.[50]

Because neoclassicism was popular during the proprietorships of Edward IV and Edward V, it is often difficult to determine who was the original owner of certain pieces in that style. Nevertheless, the neoclassical furniture in Wye House documents the Lloyds’ patronage of Maryland artisans and the family’s retention and appreciation of these objects as heirlooms. A mahogany secretary (fig. 48), or “bureau” as the form was called in Edward IV’s inventory, is part of a group of related Baltimore examples that mimic contemporary English furniture. This object may have been used by the many scribes, accountants, and clerks that Edward IV and V hired to manage their accounts, ledgers, and correspondence. The secretary stood in the office opposite the Shaw desk-and-bookcase (fig. 28) during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most recently, the secretary stored seventeenth-century maps and deeds.[51]

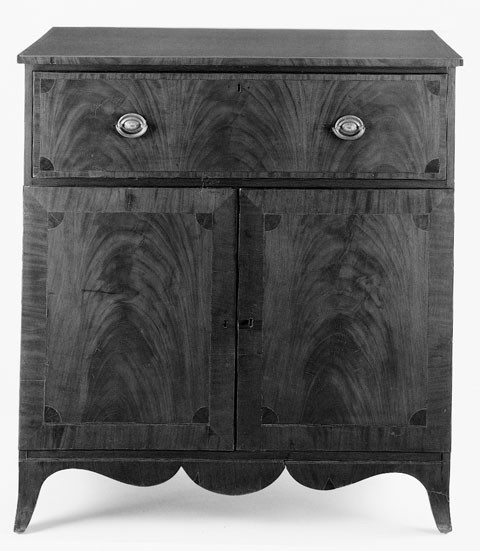

In 1797, Edward V began redecorating Wye House by purchasing vast quantities of textiles from Annapolis merchant Lewis Neth and commissioning a new desk-and-bookcase from John Shaw. Shortly thereafter, Edward paid Baltimore cabinetmaker James Martin (active 1790–1816) £22.12.6 for “a mahogany clothes press” (fig. 49). Unable to closet all their clothing, table linens, and bedding, presses and wardrobes were an essential part of the Lloyds’ furnishings. Seven examples of this form survive at Wye House, but this is the only one from the eighteenth century. Because of the broad width of the case, the cabinetmaker used central muntins to support the bottoms of the linen trays and two lower drawers. This technique made the drawer frames more rigid, allowed the bottom boards to expand and contract seasonally, and enabled the drawers and trays to support more weight without sagging or coming apart. Richard Folwell’s The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair-Maker’s Book of Prices (1796) lists a clothes press at £4, less than a quarter of the cost of the Lloyd example. The expensive mottled mahogany of the latter object and Maryland’s inflated currency probably account for much of the price difference.[52]

Several card tables in Wye House are roughly contemporary with the clothes press. Circular tables like the one illustrated in figure 50 were popular in Baltimore during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, although the Lloyd example is unusually wide—a trait more in keeping with British work. The original top must have been lost or severely damaged, for in September 1930 Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller paid the exorbitant sum of $198.90 to have it restored and fitted with a new top made of old wood. The fact that the table survived in its dilapidated state is significant, since most families discarded damaged relics.

Another card table from the same era has a square top with an elliptical front (fig. 51). It is distinguished by having a secret drawer concealed on the straight section of the front rail adjacent to right leg. Of the seven card tables listed on Edward IV’s 1796 inventory and the untold number purchased by Edward V, a pair of English card tables and these two Baltimore examples are all of the neoclassical pieces that remain in Wye House. Given the number of tables the Lloyds acquired throughout the nineteenth century, that level of survival is remarkable.[53]

Only one armchair (fig. 52) remains from the set (ten sides and two arms) Edward V purchased from Baltimore cabinetmaker William Singleton for $108 in 1801. The Lloyds used these seating forms as occasional chairs during the last half of the nineteenth century because they were no longer fashionable. The splat, which is almost identical to those on chairs made by Gillows & Co. of Lancaster, England, has an inherent weakness that likely contributed to the loss of other chairs from the set. After this example had broken several times, Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller gave it to Baltimore furniture restorer Harry Berry in exchange for work.[54]

In 1808, Edward V paid Baltimore fancy furniture painters John and Hugh Finlay for unspecified work commissioned by his mother. Although Edward V placed six additional orders between 1809 and 1833, only a fragment of a card table (fig. 53) and a window cornice (fig. 54) survive at Wye. Edward V ordered the latter on April 3, 1828. Painted furniture was used indoors and outdoors, and it served as a fashionable and less expensive alternative to comparable mahogany, walnut, maple, and rosewood forms. By the late nineteenth century, neoclassical painted furniture had passed out of fashion, and many pieces had suffered significant losses to the decoration. Given its condition, it is not surprising that the table was relegated to the barn. In fact, it is remarkable that the table survives at all.[55]

Because no original textiles remain in Wye House, the window cornices that Edward V ordered from Hugh Finlay in April 1828 and the card table are the only objects that allude to interior color schemes during the proprietorship of Edward V. The black and gold decoration on the table is sophisticated but restrained when compared to the color palette available on other fancy furniture produced in Baltimore during the 1810s. It is possible that other objects commissioned by Edward V were more vivid. The cornice, for example, has a guilloche with red and green leaves and a frieze with an Etruscan red ground. This somewhat capricious composition is in keeping with the less academic style of classicism prevalent in Baltimore in the late 1820s.

Edward V returned to Wye House after living in Annapolis while he was governor from 1809 to 1811. In 1812 and 1813, he paid Baltimore cabinetmaker Edward Priestley (1778–1837) a total of $793.87 for furniture. During the 1810s, urban cabinetmakers in Maryland and their patrons began to embrace a later phase of neoclassicism, referred to today as “classical” or “empire.” Priestley’s furniture replaced many objects purchased for Wye House by Edward V shortly after his father’s death. Later generations saved this furniture because it remained functional and relatively stylish, and large-scale household makeovers had become too expensive.[56]

Referred to in inventories as an “extension dining table,” the size of the three-pedestal dining table (fig. 55) likely dictated its survival more than its dramatically figured mahogany top. Family tradition maintains that the table accommodated as many as twenty guests when used in the large parlor, but that it more often stood in the small parlor with the center section removed and the ends pushed together. Late nineteenth-century photographs show that the sections were used to support the girandoles underneath the pier glasses in the large parlor. In the 1940s, Elizabeth Lloyd Schiller sold the table, which she disliked, to her niece, the current proprietress, who returned it to Wye in the 1990s.[57]

In early twentieth-century photographs, the Grecian sofa (fig. 56) and swivel-top card table (fig. 57) attributed to Priestley are pictured in the passage. The word “sofas” on the abbreviated 1834 inventory and the phrase “pair of sofas” in the 1861 inventory suggest that the surviving example had a mate. Similarly, the design of the radiating veneer on the top leaf of the card table suggests that it was one of a pair.[58]

The sideboard Edward V ordered from Priestley does not survive, but it is visible in a circa 1915 photograph (fig. 58). Soon after the picture was taken, Charles Howard Lloyd replaced the sideboard with a nearly identical reproduction made by Potthast Bros. During the colonial revival era, sideboards with tall tapered legs were more popular evocations of the form than those with pedestal ends, but Charles chose to duplicate the family heirloom. As decorative arts scholar Catherine Rogers Arthur has shown, the Potthast firm took pride in reproducing furniture from Maryland’s most illustrious families and, given the similarity of the original to the reproduction, it is possible that they copied the Priestley example exactly. In contrast, Charles Howard Lloyd chose to repair the knife vases (fig. 59) that sat on the sideboard rather than discard them. However, the vases were in such deplorable condition that the restorer essentially remade them. Edward IV’s meticulous inventory includes knife cases, but does not list knife vases. The examples illustrated here are British and may have been ordered by Edward V after he received two dozen table spoons and dessert spoons (engraved “ELL”) from London agent Thomas Eden & Co. in 1798. Knife vases were appropriate for a pedestal sideboard, whereas knife cases often accompanied earlier forms.[59]

A writing table (fig. 60) in Wye House has feet similar to those visible in the photograph of the sideboard. It is one of eight attributed to Priestley’s shop, all of which have similar construction features and bear a resemblance to contemporary New England examples. Priestley used the term “portable desks” to describe this form. Like most of the writing tables and desks in Wye House, its survival is attributed to its serviceability and versatility, both of which transcended fashion in some instances. Today the writing desk is used as an occasional table.[60]

Like many of his contemporaries, Priestley furnished his clients with architectural components as well as furniture. In September 6, 1826, he billed Edward V $7.60 for two feet of planed mahogany, five unturned mahogany newels, three unturned poplar newels, and “30 feet Mahogany for a Hand Rail.” Installed in the central passage at Wye House, Priestley’s handrail (fig. 61) undoubtedly replaced an older one. Perhaps the old rail had candle arms that became redundant when Edward V purchased a “passage chandelier” from Baltimore merchant R. A. Campbell. Priestley’s handrail is another Lloyd article that, given its proven service, has not required replacement.[61]