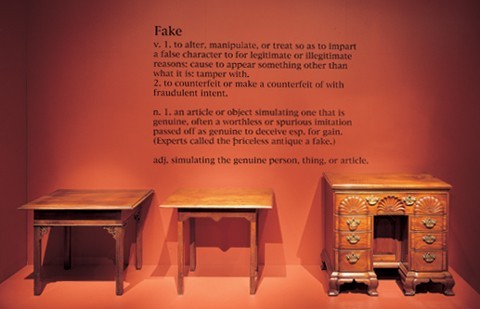

Detail of the Milwaukee Art Museum exhibition, Furniture Fakes from the Chipstone Collection, February 15, 2002–June 9, 2002. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth). The objects in this vignette are from left to right: Tea table, American, ca. 1958. Mahogany. H. 26 1/2", W. 32 3/4", D. 22 3/4"; Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Mahogany. H. 27", W. 23", D. 32" (private collection); Bureau table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1765–1780. Mahogany with white pine, chestnut, and tulip poplar. H. 32 1/2", W. 37", D. 20 3/4". The tea table on the left is a complete fake inspired by authentic examples like the one in the center. The bureau table is a period example with replaced feet and foot blocks that have been distressed and colored to make them appear original. Both of the fakes were sold as authentic with no major repairs or replacements.

Chest-on-chest, Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1780. Mahogany with chestnut, cherry, and white pine. H. 82 1/2", W. 42", D. 21 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1765–1780. Mahogany with chestnut and white pine. H. 32", W. 37 1/2", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the living room at Chipstone, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ca. 1975. (Chipstone Foundation.)

View of the living room at Chipstone, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ca. 1975. (Chipstone Foundation.)

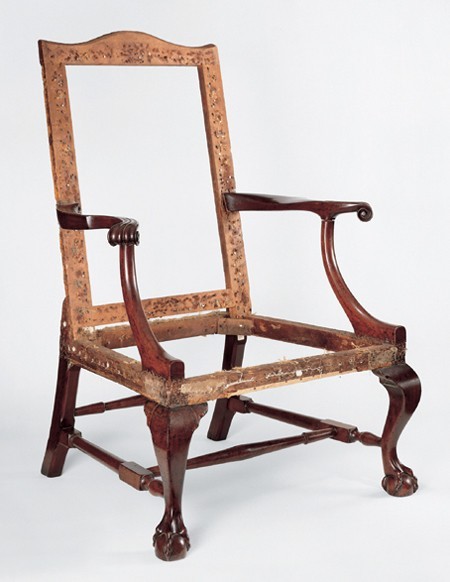

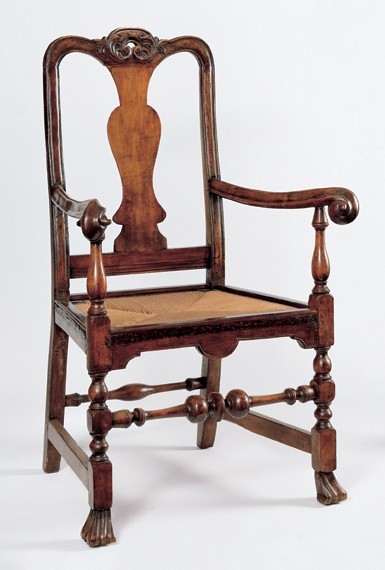

Upholstered armchair, American, ca. 1965. Mahogany with maple and pine. H. 43 3/4", W. 31 1/2", D. 31 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Lolling chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1800–1810. Mahogany and satinwood with birch and white pine. H. 45 3/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 30". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Stenger.)

Upholstered armchair, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, 1760–1770. Mahogany with maple. H. 35", W. 27 1/4", D. 25 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) With its low back and serpentine crest, this armchair is a Boston version of a “French chair.” In the second edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1755), Thomas Chippendale noted that the carving on such chairs “may be lessened by an ingenious workman without detriment.”

Detail of the artificial distressing on the surface of a leg of the armchair illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of nail holes under a knee block of the armchair shown in fig. 6.

Easy chair, American, ca. 1955. Mahogany with maple and pine. H. 49", W. 35 1/4", D. 29". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1745–1765. H. 46 1/2", W. 34 5/8", D. 21 3/8". Walnut and maple with white pine, birch, and maple. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum.)

Detail of the right front leg of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of the left quarter-round tenon of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of a ca. 1730 Boston backstool with quarter-round tenons similar to those of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 12.The tenon has a color and burnished appearance that differs markedly from the one shown in fig. 14.

Detail of the right rear leg of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the spliced joint.

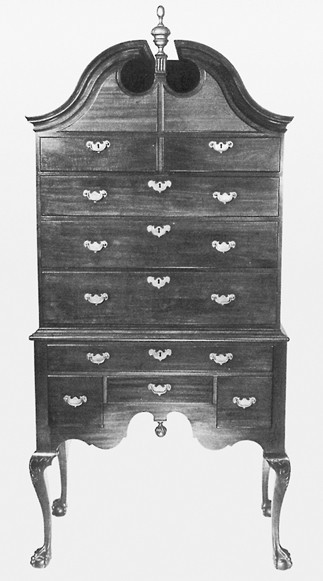

High chest illustrated in Ralph Carpenter’s The Arts and Crafts of Newport (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection).

Detail of the leg of the high chest shown in fig. 17. (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Easy chair, American, ca. 1958. Mahogany with tulip poplar, pine, and oak. H. 48 1/2", W. 33 1/2", D. 32 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

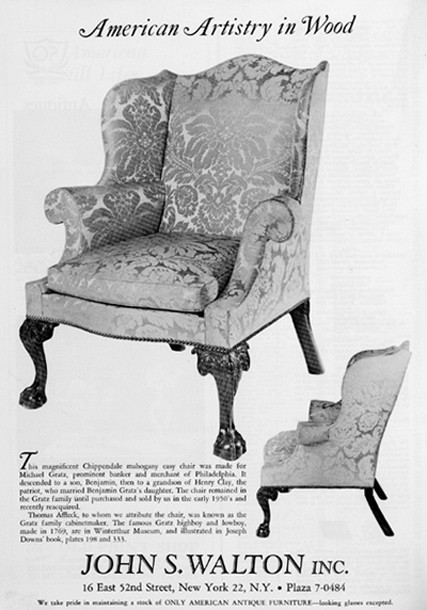

John Walton advertisement, Antiques 101, no. 4 (April 1971): 568. (Courtesy, Antiques.) The knee acanthus and feet of this chair are by the same hand that carved a dressing table and side chair that descended in the Gratz family. The latter examples are in the Winterthur Museum. www.themagazineantiques.com

Detail of the knee carving on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 19.

Detail of the right front leg and side rail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 19.

Armchair attributed to a member of the Gaines family, vicinity of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1745, with a crest rail dating ca. 1964. Maple with pine. H. 42 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 23 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 23.

Armchair attributed to a member of the Gaines family, vicinity of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1730–1745. H. 43", W. 29 1/4", D. 21 3/8". Maple and cherry. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 25.

Armchair, American, ca. 1962. Mahogany with pine and poplar. H. 43 1/2", W. 33", D. 24 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, 1750–1755. H. 39 1/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum.)

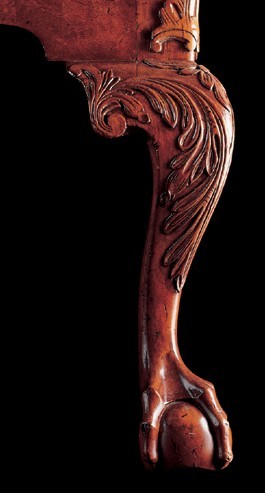

Detail of the knee carving on the armchair illustrated in fig. 27.

Detail of the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 28.

Card table, American, ca. 1959. Mahogany with white pine. H. 29", W. 32", D. 15 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table illustrated in the catalogue of the Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Furniture and Glass… for the Benefit of the National Council of Girl Scouts (New York: American Art Galleries, 1929), no. 627.

Detail of the underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 31. The undersides of the front and side rails have been colored with black stain.

Detail of the underside of a Newport card table dating 1765–1775. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The secondary surfaces of this card table are very diVerent from those of the fake illustrated in fig. 33. All of the components are the same color because they have been exposed to the same atmospheric conditions and level of light. The fine file marks on the undersides of the rail and knee blocks are typical of eighteenth-century Newport work.

Card table, American, ca. 1958. Mahogany with oak and tulip poplar. H. 26 1/2", W. 33 1/2", D. 16 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Illustration of a New York card table in Joseph Downs, American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods in the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (New York: MacMillan Co., 1952), nos. 340–41.

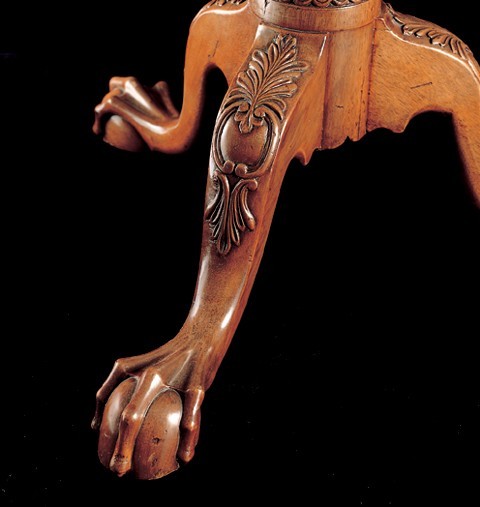

Detail of the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 35.

Detail of a pin securing a mortise-and-tenon joint on the card table illustrated in fig. 35.

Detail of a pin securing a mortise-and-tenon joint on a New York card table with carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle (active 1750–1755). All of the pins securing the mortise-and-tenon joints are slightly distorted, and they protrude just above the surface of the leg stiles. The fractures extending from the corners indicate that the maker drilled his holes with a spoon-bit.

Details of the underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 35 showing (from left to right) the drawer inserted and the drawer withdrawn. The drawer may have come from the interior of a desk or bookcase.

Oval table, American, ca. 1961. Walnut with maple and pine. H. 26", W. 26", D. 26". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

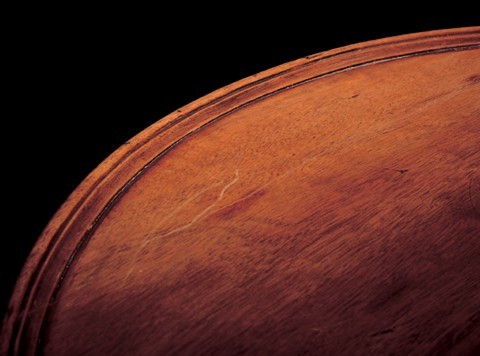

Detail of the top of the table illustrated in fig. 41.

Detail of the inner frame of the table illustrated in fig. 41.

Candlestand, American, ca. 1959. Mahogany. H. 27 3/8", Diam. of top: 22 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the candlestand illustrated in fig. 44.

Candlestand, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the candlestand illustrated in fig. 46.

Detail of the top of the candlestand illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of a plugged hole on the underside of the top of the candlestand illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail showing the edge molding of the candlestand illustrated in fig. 44. This molding was cut with a router and edge tools rather than being turned on a lathe.

Candlestand, Philadelphia, 1780–1800. Mahogany. H. 27 1/4", Diam. of top: 27 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the underside of the top, birdcage, and battens (removed) of the candlestand illustrated in fig. 51. The bearing surfaces on stands and tea tables of this form are: the underside of the top bearing on the top board of the birdcage; the uppermost tip of the pillar on the hole in the underside of the top board of the birdcage; the shoulder of the tip on the underside of the top board of the birdcage; the collar on the upper side of the bottom board of the birdcage; and the underside of the bottom board of the birdcage on the large shoulder below. The wear on all of these surfaces should be consistent if all of the components are original.

Candlestand, American, ca. 1961. H. 27", Diam. of top: 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table, American, ca. 1957. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 30 3/4", W. 34", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table attributed to the shop of Henry Clifton and Thomas Carteret, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1755. Mahogany with pine and white cedar. H. 30 3/4", W. 34", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This dressing table is a superb example of Philadelphia case furniture from the early 1750s. Its construction is nearly identical to that of a dressing table and matching high chest made by Clifton and Carteret in 1753 (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation). Like those objects and other comparable forms documented and attributed to their shop, this dressing table has dustboards below the lower drawers.

Detail of the carving on the lower center drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 55.

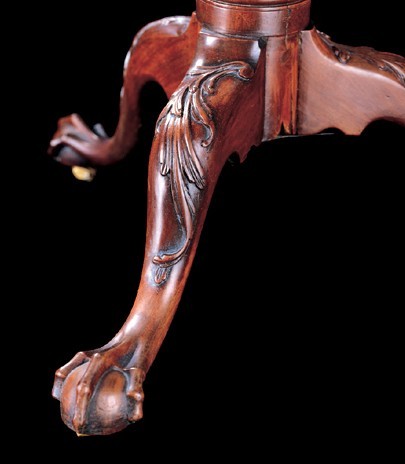

Detail of the knee carving on the dressing table illustrated in fig. 55.

Detail of the carving on the lower center drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 54.

Detail of the knee carving on the dressing table illustrated in fig. 54.

Detail of the bottoms of two lower drawers from the dressing table illustrated in fig. 54.

Detail of the underside of the top of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 54.

Dressing table, American, ca. 1958. Mahogany with maple, chestnut, and tulip poplar. H. 33 1/4", W. 35 1/8", D. 20 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the interior case construction of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 62. The undersides of the rails were finished with a rasp rather than a file as was common in eighteenth-century Newport shops.

Detail showing the interior case construction of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 62.

Detail showing the drawer fronts, skirt, and carved shell of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 62. The convex and concave lobes of the shell are poorly regulated, and the central palmette is clumsy and overwrought. The faker responsible for this object was simply not up to the task of replicating eighteenth-century carving, even that as simple as the ornament commonly found on Newport furniture.

Detail showing the interior case construction of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 62.

Detail of the right front foot of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 62.

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, Massachusetts, 1760–1770, with disguised repairs dating ca. 1956. Mahogany with white pine. H. 96", W. 41", D. 20 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left door of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the inner surface of the left door of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the foot and base construction of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 68.

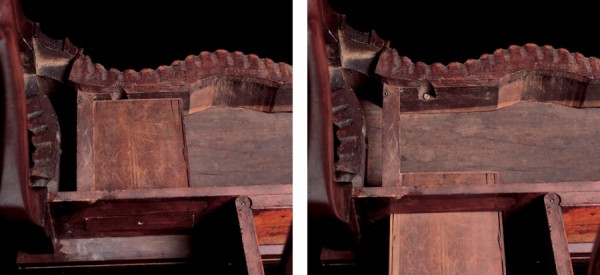

Detail of the back of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 68.

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1750. Mahogany with white pine. H. 97", W. 40 1/2", D. 23". The turned feet and finials, tromp l’oeil decoration inside the bookcase, and carving are the work of independent specialists contracted by the shop master. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Nearly every major collection of American furniture assembled during the last century has included objects that were intended to deceive. These pieces run the gamut from authentic furniture forms with carefully masked repairs, replacements, or embellishments to complete fakes. Although the subject of fraudulent objects can be a touchy one, everyone involved in collecting antique furniture has made mistakes. Reluctance among museums, dealers, and private collectors to discuss, let alone publish and exhibit fakes, contributes to their continued production and presence in the marketplace (fig. 1).

The prevalence and persistence of fakery are intimately linked to the demands and expectations in the marketplace. Few pieces of early American furniture survive in perfect condition, and even less are perceived as having the added qualities of artistic merit and/or historical significance. Although each of these considerations is important in assessing an object’s monetary value, museums, collectors, and individuals in the American furniture trade have traditionally placed an unreasonably high premium on condition. Fakers or individuals who knowingly sell fraudulent objects often attempt to make pieces with condition problems appear perfect in order to reap the benefits of this perspective.

Because scholarship has always been tied to the marketplace, unrealistic expectations regarding condition have distorted American furniture history. Mass-produced or poorly made objects in excellent condition often command higher prices and more attention than important pieces with replaced parts. This is even true of replacements that are minimally conjectural. Fakes also distort furniture history by promulgating the notion of non-existent forms or by making extremely rare forms appear relatively commonplace. Scholarship is always tainted when it is based on forged source material.

The Chipstone Collection

All of the fraudulent objects in this article are from the collection of Stanley and Polly Stone of Fox Point, Wisconsin. The Stones began collecting American furniture in 1946, when they purchased a Salem, Massachusetts, secretary from Israel Sack. Within four years, they had acquired twenty-eight additional pieces ranging in quality from simple stands to monumental case pieces. The Stones’ first opportunity to purchase a major piece of American furniture came in 1949 when New York antique dealers Benjamin Ginsburg and Bernard Levy offered them an eighteenth-century Rhode Island chest-on-chest (fig. 2). Like many beginning collectors, the Stones agonized over their decision for months but eventually decided to purchase the chest-on-chest because it had carved shells, a blocked facade, and a history of ownership by a prominent individual—Providence merchant Jabez Bowen. They felt that it would be economical to acquire a single object with all of these attributes because they would complete their Rhode Island collection in “one fell swoop.” The Stones’ reasoning began to unravel almost immediately. Four years later they purchased a Newport chest of drawers (fig. 3) with carved shells, blocked drawers, and a history of ownership by Rhode Island governor Joseph Wanton.[1]

In a newspaper interview, the Stones described themselves as “poor deluded victims” who failed to realize that they had been stricken with “virus antiquarium.” Their “affliction” prompted them to commission Boston architect Andrew Hepburn to design a house to display their rapidly growing collection. Chipstone was completed in 1950, and like several of Hepburn’s residential projects, it has details inspired by eighteenth-century buildings from the Chesapeake region of Maryland and Virginia.[2]

Although the Stones also collected early English pottery and American historical prints, they were primarily interested in furniture from the northeastern urban centers. During their collecting career, they acquired major works from Portsmouth, Boston, Newport, New York, and Philadelphia. Like nearly every major collector of their generation, they also purchased objects that were intended to deceive. In fact, nearly half of the furniture visible in figures 4 and 5 is fraudulent. These objects and other spurious pieces in the collection shed light on the techniques of a small group of fakers working from the 1940s to the 1980s.

A Rogue’s Gallery

Upholstered armchairs are one of the most commonly faked types of seating furniture. Two examples in the Chipstone collection (fig. 6) have frame components salvaged from neoclassical lolling chairs (fig. 7), which probably had legs that were cut off or severely damaged. The dealer who sold the Stones the chair illustrated in figure 6 attributed it to Boston and described it as “one of the finest...of this type we have seen.” Dozens of similar fakes, most with tall backs and either claw-and-ball or pad feet, have appeared on the market during the past eighty years, and many have found their way into important public and private collections. The Chipstone chair is one of the least sophisticated because it has incompatible design features such as Boston-style legs and stretchers and Delaware Valley-style arms. During the eighteenth century, Boston chair makers typically followed British precedent in the design and construction of upholstered seating forms (fig. 8).[3]

Evidence of wear on this chair is inconsistent with normal use. The undersides of the stretchers have the same dents, scuffs, and abrasion marks as the exposed surfaces, and all of the damage occurred at once rather than incrementally. In contrast, period objects typically have worn surfaces that reflect different patterns of use over many years. The faker used an object with an irregular surface to distress the arms, legs, and stretchers, then he applied a dark stain (fig. 9). The torn fibers absorbed the stain more than the undamaged surfaces; therefore, the dark color remained localized during the application of the finish coat.

The most compelling evidence that this chair is a fake is an old upholstery line for the neoclassical frame that extends under the present knee blocks (fig. 10). Some clever fakers used patches to remove this type of evidence. Because authentic chairs often have patches where repeated nailing has eroded the frame, care must be taken in evaluating such evidence. In some instances, it is necessary to plot all of the nail patterns to determine authenticity, especially in the case of complex fakes comprised of parts from more than one chair.[4]

To expedite and simplify their work, most fakers adapt parts from period objects. The individual who produced the fraudulent easy chair illustrated in figure 11 simply discarded the presumably damaged legs and stretchers on a mid-eighteenth-century Massachusetts easy chair (fig. 12) and dded new legs in the Newport style. The front legs show no evidence of wear or damage, even along the lower upholstery line where the surface typically has scars from nail heads, knife cuts, or hammer impacts inflicted during repeated applications of fabric (fig. 13). The faces of the knee blocks are equally pristine, and their undersides are finished with a coarse file. Although the faker soaked the quarter-round tenons in stain to make them appear old (fig. 14), their color and character differ significantly from those on period examples (see figs. 12, 15). More importantly, the wood surface and undersides of the front legs match those of the rear legs, which are obvious replacements. The original rear legs on this chair were probably extensions of the back posts like those on the chair shown in figure 12. There is no way these spliced joints (fig. 16) could be interpreted as original construction, even though the Stones received assurances that there were no major replacements or restorations.

Fakers often incorporate details from authentic published objects to make their work more believable. At first glance, the fake Newport easy chair (fig. 11) appears to be related to a Rhode Island high chest in the Yale University Art Gallery (fig. 17). Both pieces have knees with cut-card scrolls and husks and claw-and-ball feet with exaggerated knuckles and long talons (figs. 13, 18). The Stones would have recognized these features because the high chest appeared in Ralph Carpenter’s The Arts and Crafts of Newport a year before they were offered the chair. The individual who sold the Stones this chair knew that they were avid collectors and students of Rhode Island furniture and close personal friends of Mr. Carpenter.[5]

In assessing furniture, most collectors of the Stones’ generation focused more on style, form, and ornament than on construction. Fakers often exploited this perspective by producing objects that were ostensibly from well-known suites or groups. The easy chair illustrated in figure 19 is one of three virtually identical fakes based on a period example commissioned by Michael and Miriam Gratz, probably just after their wedding in 1769. Antique dealer John Walton owned the original twice—once during the early 1950s and again in 1971 (fig. 20). The individual who sold the Stones their chair described it as a “mahogany claw-and-ball foot upholstered easy chair with fine carving similar to that on the Gratz Wing chair which was attributed to Thomas Affleck, the Gratz family cabinetmaker. This chair can reasonably be given the same attribution.” The dealer knew that this history would appeal to the Stones because they had purchased a tea table with the same history in 1953 and were undoubtedly familiar with the Gratz high chest and dressing table at the Winterthur Museum.[6]

Each of the fake Gratz chairs has poorly executed carving that, aside from its basic design, has almost nothing in common with period workmanship (fig. 21). The sharp spines separating the leaves and divergent veining have no precedent in Philadelphia carving, and the work is contrived and overwrought. The seat rails provide conclusive evidence that the legs are modern replacements. Holes for wooden pins are present on the tenons, but absent on the corresponding faces of the front legs (fig. 22). This indicates that the seat rails are salvaged components from another chair that had pinned joints.[7]

Some of the most difficult fakes to identify tend to be period objects with carefully disguised restorations or replacements. The armchair illustrated in figure 23 is attributed to a member of the Gaines family of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but it has a replaced crest rail (fig. 24) carved by the same faker who made the fraudulent Gratz easy chair (figs. 19, 21). Like many period chairs, the Gaines example sustained damage when it fell over—probably with the user sitting or standing in it—thus breaking the crest rail and upper portion of the stiles.[8]

The dealer who sold the Stones this armchair described it as “one of only three or four...known,” and noted that an example in the Winterthur Museum had nearly identical carved details. The Stones probably recognized these similarities since they supported that museum and received information on new acquisitions. Winterthur published the authentic chair (figs. 25, 26) in a report titled Accessions, 1960, four years before the Stones purchased their example.[9]

Unlike the preceding fakes, which have component parts salvaged from period seating, the armchair illustrated in figure 27 is entirely new. Its basic design and carved details were derived from a well-known set of side chairs (fig. 28) reputedly used by George Washington in the presidential house in Philadelphia. The Washington chairs date about 1755, and are part of a large group of Philadelphia furniture with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard.[10]

The carving (fig. 29) is by the same hand that produced the fake Gratz easy chair and the crest rail on the Gaines armchair (figs. 19, 21, 23, 24). Although the design of the ornament on the two pieces is different, the leaves on both examples have excessively deep flutes and shading cuts that intersect at the tips of the leaves in an unconventional manner. The fraudulent nature of this work becomes even more apparent when compared with the period carving that inspired it (fig. 30). The leaves on the knees of the Washington chair have precisely cut edges, carefully regulated convex and concave surfaces, and crisp shading cuts. Bernard’s style was fully developed; his designs, tools, and techniques were perfectly integrated; and he worked intuitively, efficiently, and quickly. In contrast, the carving on the Chipstone chair has a tedious quality, indicating that the faker struggled to mimic period work. His curled leaves are stiff and truncated, whereas those on the Washington chair have a more naturalistic flow and appearance.

As the fraudulent Philadelphia armchair suggests, the most convincing whole cloth fakes are made from old wood. Armchairs, side chairs, bedsteads, stands, and tea tables are the preferred forms for this type of chicanery because they have a minimal amount of secondary wood. Conifers and other softwoods are very difficult to color and age without the use of oxidants and stains, which are red flags to most collectors. To overcome this problem, fakers frequently use parts from damaged or undervalued period pieces, often of the same form as the object they intend to produce.

The faker responsible for the card table illustrated in figure 31 based his design on an example illustrated in the 1929 catalogue of the Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition (fig. 32) and incorporated a rear rail and fly rail from a period card table. The undersides of the front and side rails have deep striations produced by a rasp, a tool rarely used in the eighteenth century (fig. 33). Period tables with shaped rails occasionally have file marks in similar contexts, but the striations are invariably finer, more intermittent, and concentrated in areas where the maker had to remove saw kerfs or undercut his work (fig. 34). The maker of this fake used glue blocks to conceal discontinuous surfaces and fresh saw cuts like those at each end of the shortened rear rail.[11]

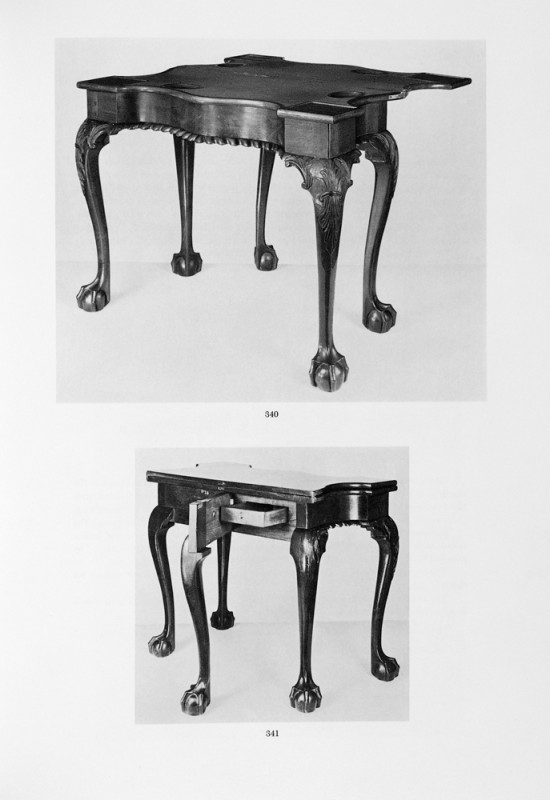

Another fake card table in the Chipstone collection (fig. 35) also has a rear rail and fly rail from a period example. Like the preceding table, its design is based on a published form. Winterthur curator Joseph Downs illustrated the prototype in 1952 (fig. 36), eight years before the Stones acquired their fake. The text and views shown in his catalogue American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods provided basic information about the size, woods, and construction of the rear rail and drawer. The faker knew that a potential buyer would probably consult this publication and tailored his work accordingly.[12]

The knee acanthus (fig. 37) is by the same modern carver responsible for most of the fraudulent pieces in the Chipstone collection. The design of this individual’s work varies a great deal, but his techniques and lack of skill remained relatively consistent. In contrast, the acanthus on the period table that inspired the fake is competent and relates to a large group of New York carving from the 1760s and 1770s.

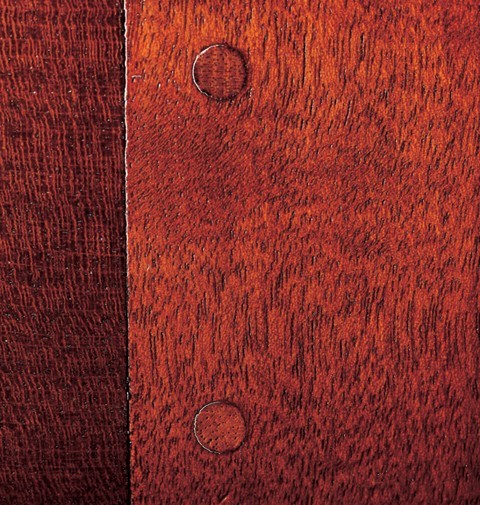

The construction of the Chipstone table provides several clues that it is fraudulent. The pins on the fake table are perfectly round and flush with the surface (fig. 38) because the holes for the pins were drilled with a twist bit rotating at a very high speed and the maker used modern, kiln dried lumber. In contrast, the pins on authentic examples are slightly out-of-round and often protrude just above the surface (fig. 39). Most eighteenth-century cabinetmakers drilled their pin-holes with a spoon bit, a U-shaped tool that typically damaged the end-grain in the upper right or lower left corners if the bit rotated clockwise or in the opposite corners if it rotated counter-clockwise. The disturbances became more pronounced as the maker rotated his brace and bit to ream the mouth of the hole and provide a wedged fit for the tapered pin. Although the process of driving in the pins often created fractures emanating from the damaged end-grain, the pin distorted the hole much less than the shape of the hole distorted the pin.

To make the interior surfaces of the card table appear more convincing, the faker used old boards for the top and the side and front rails (figs. 40 a, b). He stained the areas sawn out in the process of forming the serpentine curves and used a drawer and drawer supports salvaged from one or more period pieces. Fortunately, the faker did not expend much effort integrating the old and new components. For example, there is no shift in the color of the top above the drawer. Given the fact that the table is supposed to be nearly 250 years old, one would expect a discernible difference.[13]

Although most of the spurious objects in the Chipstone collection date between 1950 and 1970, the practice of faking American furniture was well established by the early twentieth century. Small folding-leaf tables like the one shown in figure 41 are among the most commonly faked forms, owing to their rarity and long-standing popularity with collectors. Most are assembled from parts of larger tables.

The top of this piece (fig. 42) is made from boards with different histories. There is almost no wear from rotation of the swing legs, and the rule joints between the top leaves were cut with a modern table saw. The color of the undersides of the leaves and center section of the top is very different when it should be similar, and the surface under a supposedly ancient wrought iron bracket is identical to that surrounding it when it should be different.

The ends of the inner rails have fresh saw kerfs indicating that they were cut from older boards (fig. 43). The dealer who owned this table also sold the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation a similar example during the 1950s. Although no correspondence concerning the Chipstone table survives, the Stones probably knew of the Williamsburg table and felt fortunate to acquire a comparable object.[14]

Of all the fake forms in the Chipstone collection, candlestands are the most numerous. The dealer who sold the Stones the stand illustrated in figure 44 noted that only three or four Philadelphia examples with “carving as rich” were known and assured them that the object was authentic and in good condition. In reality, nearly all of its components are new, and the knee acanthus (fig. 45) and feet are by the same carver responsible for many of the aforementioned fakes (see figs. 19, 23, 27, 31). Several stands and tea tables by this individual are known, most of which have unconventional and poorly regulated compressed ball turnings, badly designed and ineptly carved leaves, and exaggerated claw-and-ball feet. This work differs significantly from period Philadelphia carving like that on the candlestand illustrated in figures 46 and 47.[15]

The faker knew that collectors often checked circular tops to verify that they had shrunk across the grain, so he cut the top of the stand slightly out of round (fig. 48). Because this prevented him from turning the top, he used a router and edge tools to produce the molded rim. To fabricate period turning evidence, the faker drilled and plugged holes in the back of the top (fig. 49). He clearly understood that Philadelphia “dish” tops were usually turned on a lathe faceplate or turner’s cross—an outboard set-up for turning objects with diameters too large to be shaped over the bed of the lathe. What he failed to understand, however, is that the edge moldings on any object turned in this manner are both regular and congruent. Because these moldings are produced in a single axis of rotation, they cannot wander in or out of their proscribed arcs; the individual elements cannot deviate in distance from the center or from each other nor can they vary in depth from each other (figs. 48, 50). The edge of a turned top will distort if the top shrinks, cracks, or warps, but the moldings and the relationship of one element to another remains constant.

A late eighteenth-century Philadelphia candlestand (fig. 51) in the Chipstone collection exemplifies period design and workmanship. It demonstrates how the moving parts of such forms imprint evidence of rotation and bearing wear over time. The inner surfaces of the battens have rotation marks around the pentil holes. This wear occurred as the upper board of the birdcage rubbed against the battens when the top was raised and lowered. The underside of the top also has a clear imprint from bearing on the birdcage, and the birdcage has predictable wear from bearing and revolving on the pillar (fig. 52).

The plugged holes on the back of the top and congruent moldings on the face indicate that the maker turned the top on a lathe. The top shrank about three-eighths of an inch, requiring the owner to reset the screws securing the battens (fig. 52). Obviously the amount of shrinkage and adjustment of the screws should be proportional. Most period tops have shrunk since their manufacture, although the amount can be minimal on those produced during the driest months.

The same individual who sold the Stones the preceding fake stand offered them the example illustrated in figure 53 three years later. He clearly understood the appeal of having two similar stands from the same city, one with a dish top and carving and another with plain knees and a scalloped top. The turning evidence on the pillars of both objects is at odds with period work. Eighteenth-century turners shaped their stock on relatively slow moving lathes using shearing cuts that removed wood in much the same manner as peeling an apple. Although woodworkers had access to rudimentary sandpapers and other abrasives, they rarely used them to finish turnings. By contrast, the pillars on the fake stands were turned and finished on a modern high-speed lathe. Both have fine concentric abrasion marks perpendicular to the axis of their pillars.[16]

As one might expect, the most complex fakes in the Chipstone collection are case pieces. At first glance, the dressing table illustrated in figure 54 appears to be contemporary with one that descended in the Biddle family of Philadelphia (fig. 55). Both pieces have a molded top with shaped front corners, broad fluted chamfers, a deep skirt, and a long drawer over three smaller ones—details common on Philadelphia dressing tables made between 1730 and 1760.

The carving on the authentic dressing table (figs. 56, 57) is attributed to Nicholas Bernard. Unlike many Philadelphia carvers, Bernard was a locally trained artisan. He probably apprenticed or worked as a journeyman with Samuel Harding whose shop provided most of the architectural carving for the Pennsylvania State House, known today as Independence Hall. The maker of the Chipstone dressing table attempted to mimic Bernard’s naturalistic style (figs. 58, 59), but was not up to the task. His acanthus appliqués consist of awkward clusters of deeply hollowed leaves similar to those on other fakes discussed here. The fake knee carving, for example, is virtually identical to that on the fraudulent armchair shown in figures 27 and 29.[17]

The construction details and materials used to fabricate this dressing table also identify it as a fake. All of the lower drawers are assembled from drawer parts from another case piece. Two appear to have been cut down from the upper drawers of a high chest, which typically have pulls placed near the top of the front. In contrast, the brasses on corresponding drawers of period Philadelphia dressing tables are usually centered. The faker pieced out the drawer sides and stained the bottoms (fig. 60) to hide reworked surfaces and color discrepancies resulting from the use and alteration of period components. Similarly, he used stain to obscure the newly scalloped lower edge of the backboard. The leaf of a dining table provided a reasonably convincing board for the top of the dressing table. Fortunately, the faker neglected to remove the scribe line (fig. 61) that originally denoted the position of the hinge joints.

A fake Newport dressing table (fig. 62) purchased by the Stones one year after they acquired the fraudulent Philadelphia example is related in being made of old boards, salvaged drawer parts, and a table top. The dealer’s invoice described the piece as a “lowboy made by the Goddard-Townsends” and noted that its “legs are the typical Newport removable type.” He also called attention to other features characteristic of that town’s production including the carved shell on the skirt and the object’s chestnut and tulip poplar secondary woods.[18]

Given their interest in Newport furniture, the Stones would have recognized these features. Although they undoubtedly realized that dressing tables from that town with claw-and-ball feet were extremely rare, they would have been familiar with the authentic example exhibited at the 1950 loan exhibition of Rhode Island furniture. Ralph Carpenter illustrated the period dressing table four years later in Arts and Crafts of Newport.[19]

The faker responsible for the fraudulent dressing table knew that it had to satisfy certain expectations about design, construction, and materials, but he was not concerned that his fabrication would be carefully scrutinized or partially disassembled because standards for authentication were minimal at the time. Rather than distressing and staining new lumber, he assembled a variety of old boards to make the top, case sides, front skirt, and drawer fronts. The large front board of the top appears to have come from the top of a drop-leaf table. Its underside has marks from a water-powered saw, but the corresponding surface of the other top board does not. To create a visual link between these disparate surfaces, the faker painted the undersides with a grey wash. He used an electric rotary router to produce the edge molding, which has irregularities from the tool’s vibration. To discourage removal of the top, the faker secured the boards with thirteen cut nails, two modern screws, and sixteen glue blocks. Many of the glue blocks vary considerably in age, color, and shape, but collectively they helped conceal the juncture and different surfaces of the case frame and top (fig. 63). After attaching the top, the faker painted the underside with a grey wash to make the surface uniform.

In a similar manner, the faker stained the underside of the modern chestnut drawer divider to make it appear that the center section was exposed to more light than the flanking areas above the drawers and had darkened over time (fig. 63). He also painted a dark wash on the back of the front rail but allowed the stain to bleed under the area covered by the lapped edges of each drawer guide. Surprisingly, the faker used glue and modern cut nails rather than forged ones to secure each joint.

The joinery of the case also provides indisputable evidence that it is fraudulent. Between the two boards of the back rail, the faker inserted thin strips of wood to make it appear that they had shrunk over time (fig. 64). However, the frame is essentially a dovetailed box with nothing to restrict the movement of the back or sides for that matter. The boards and their dovetail joints are at different heights and would not align without the strips, although they were ostensibly added after construction. Furthermore, the faker chopped the mortises for the drawer dividers after the strips of wood were in place.

Realizing that chestnut was a common secondary wood in eighteenth-century Newport furniture, the faker used it for the back of the case. Although the section below the shrinkage strips appears to be a single board with a crack, it is actually two pieces. The faker undoubtedly had a chestnut board with nail or screw holes that may have caused a potential buyer concern, so he removed the troublesome holes by sawing out a half-inch section with a band saw then glued the remaining sections together. He employed the same technique to remove marks on the chestnut boards used for the drawer bottoms.

The reuse of period parts created several problems for the faker. The top drawer has little figure and witness marks for two different escutcheon plates (the current escutcheon is a converted pull plate) whereas the lower drawer fronts are clearly modern, have stripe figure, and were only recently fitted with brasses, which may have been salvaged from the piece of furniture that provided the upper drawer front. The faker used a lip patch on the lower left drawer to make it appear as though it was damaged through use. Other attempts to misdirect a potential buyer are evident in the intentional “repairs” to the toes of the claw-and-ball feet and “replaced” knee blocks, all of which are part of the original fabric of the fake.

The feet of the dressing table provide one of the strongest visual and stylistic clues that it is fraudulent. They appear to be an amalgam of two types of Newport feet, although neither of the period varieties have flat, concave passages in the ankles. The feet on the dressing table do, however, resemble those on several other fakes including the easy chair illustrated in figure 11. The faker’s inability to simulate the passage of time by modulating color and wear are evident on the feet of both objects. The finish is one-dimensional and does not vary even on the undersides and edges of the toes. Similarly, the only wear is a series of small, unconvincing dents all done at the same time.

The bombé desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 68 differs from the dressing tables in being a period object with significant repairs, all of which were intended to deceive. In his introduction to Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque’s, American Furniture at Chipstone, Mr. Stone wrote:

In March 1956, we went to Europe, and when we returned we dropped into [a dealer’s shop] and there we saw a truly outstanding Massachusetts bombé secretary of great quality. Coincidentally, Maxim Karolick came in while we were there [and] rapsodized about the secretary until any doubts that we might have had about it, and I hasten to say they were minor, vanished.

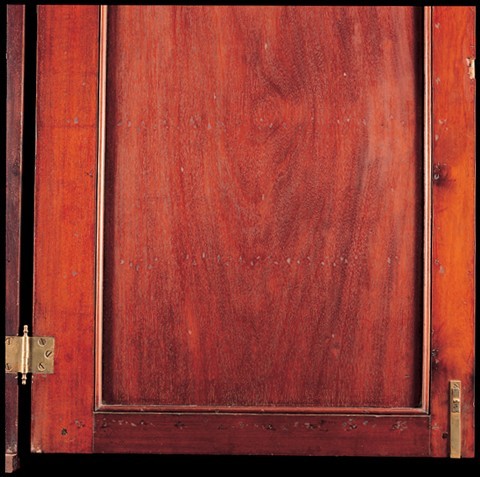

When the Stones and Karolick examined this piece, it probably appeared more convincing than it does today. The modern door panels, fallboard, and feet would not have had their current greenish cast that has resulted from the use of a fugitive red dye.[20]

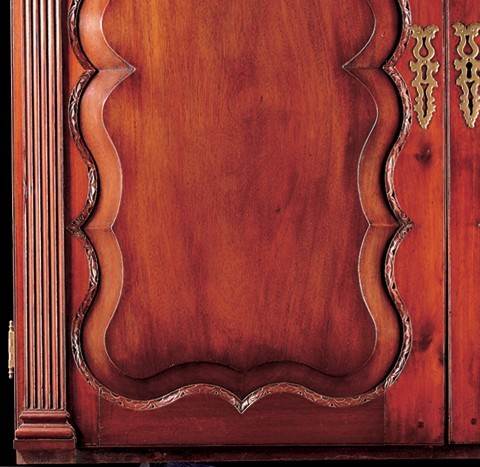

The doors were clearly constructed for mirrors rather than panels (figs. 69, 70). Scalloped, fielded panels are almost always trapped in grooves in the door stiles and rails, and the inner edges of the stiles and rails have the same outline as the panels. The doors on this example have rectangular rabbeted openings, indicating that they were made for either mirrors or flat panels. Remnants of glue blocks on the edges of the rabbets suggest the former.

Damage to the lower edge of the base molding provides the first clue that the feet are replaced. Although the current feet are reasonably accurate interpretations of contemporary Boston examples, their stained inner edges, braces, and glue blocks identify them as modern replacements (fig. 71). The maker evidently used some old glue blocks from another case piece, but had to modify and color them to match the height, width, and shape of the feet.

The boards used to make the tympanum are from very different grades of stock, and the section behind the scrolls has end-grain laminations that deviate radically from eighteenth-century cabinetmaking practices (fig. 72). In a misguided attempt to create a period tool history, the faker used a rasp and a quarter-round gouge to shape the upper edge of the scroll board; however, he neglected to remove the modern mill marks on the pediment braces and glue blocks. To disguise new and inconsistent secondary surfaces, the faker used black paint and dark stain. All of the backboards, for example, are painted to match the exposed areas of the pediment.

The faker expended little effort on the fallboard of the desk, other than using an old mahogany board. Unlike many of his peers, he did not attempt to duplicate the water and ink stains on the floor of the writing compartment or the number and position of screw holes in the original hinge mortises. Most clever fakers either match the screw evidence or remove it by inserting patches that make it appear as though the floor of the writing compartment and fallboard have honest conforming repairs.

An authentic Boston desk-and-bookcase purchased by the Chipstone Foundation in 1991 stands in sharp contrast with the fake (fig. 73). The former is part of a large group of furniture made in Boston between 1735 and 1755. The most elaborate examples have blocked or bombé desk sections, three or four engaged pilasters or columns, applied and relief carving, and tromp l’oeil decoration. Although the master of this shop has not been identified, he appears to have been the first American cabinetmaker to produce blockfront and bombé forms. He was clearly familiar with a broad range of stylistic details, some of which were fashionable during the late seventeenth century. The gadrooned ball feet on the desk-and-bookcase, for example, are similar to those shown in engravings by Huguenot designer Daniel Marot.[21]

As this desk-and-bookcase suggests, the many important pieces of American furniture collected by the Stones greatly overshadow the small number of fraudulent objects illustrated here. Much of the credit for rebuilding the collection must be given to Mrs. Stone, who insisted that the fakes be used for educational purposes and that pieces of comparable quality and historical significance be added to those that she and Mr. Stone assembled. Mrs. Stone acted bravely and responsibly in not allowing their mistakes to become someone else’s mistakes, which could have occurred had these fakes re-entered the marketplace. She understood that fakes must be exposed and published to insure that American furniture scholars have reliable source material to study and interpret.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank the staff of the Chipstone Foundation and the collectors who allowed them to illustrate authentic objects from their collections.

Stanley Stone, “Life Begins at Fifty,” in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), vii, viii. Stanley Stone lecture notes, Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wis.

Milwaukee Journal, undated clipping, Chipstone Foundation. The Chesapeake details reflect Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn’s experiences with the restoration and reconstruction of Colonial Williamsburg.

Invoice, April 22, 1964, accession files, Chipstone Foundation. All subsequent references to invoices are from these files.

Eighteenth-century designs for chairs with upholstered backs and open arms are shown in Pictorial History of British Eighteenth-Century Design, compiled by Elizabeth White (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collector’s Club, Ltd., 1990): 100–104. The earliest manifestations of this form have their origins in seventeenth-century seating commissioned for the courts of Paris and Versailles. Made with tall, upholstered backs and open arms, these fauteuils subsequently attained a measure of popularity in Britain where they were referred to by various names including “grand chairs” and “elbow stools.” Daniel Marot illustrated the archetypal late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century French model in Second Livre d’Apartements and Nouveaux Livres di Licts de differentes penseez (ca. 1703 and 1713), pls. 5, 7 (p. 98). These chairs and their later variants often had accompanying seating forms referred to today as “backstools.” Gaetano Brunetti’s Sixty Different Sorts of Ornament (1736) illustrates two upholstered armchairs and two similar backstools. The armchairs are essentially baroque forms with Italianate undercarriages and nascent rococo details (p. 99). These are the only published British designs for high-back upholstered chairs with open arms and cabriole legs known to the authors, and surviving examples of this form are extremely rare. Most eighteenth-century upholstered chairs with open arms and cabriole legs had low backs. British architect William Kent designed several types in his distinctive Palladian style, examples of which are shown in J. Vardy, Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones & William Kent (1744), pl. 43 (p. 99). Although rococo versions probably became fashionable in Britain by the late 1740s, they were not represented in design books prior to the publication of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754). Chippendale called this form a “French chair” (pp. 100-101). Related seating forms described as “French chairs” and “French Back Stools” are also illustrated in William Ince and John Mayhew, The Universal System of Houshold Furniture (1762), pls. 55, 56, 58, 59 (p. 103); the Society of Upholsterers, Genteel Houshold Furniture in the Present Taste (1765), pls. 26–28 (p. 102); and Robert Manwaring, The Cabinet and Chair-Maker’s Real Friend and Companion (1765), pls. 16, 17, 21–23 (p. 104). Plate 10 of George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1794) illustrates designs for “cabriole chairs,” which have upholstered backs, open arms, and a gap between the seat and back (p. 105). His designs for “state chairs” are similar but they do not show a gap in the back (p. 106).

The earliest publication showing an American chair with an upholstered back, open arms, and cabriole legs is Luke Vincent Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1921), 2:109 , no. 582. Although not examined by the authors, this chair appears to be a period example. It has extremely upright rear post/legs that extend almost straight down below the seat rails and small knee blocks that relate to corresponding elements on an authentic Rhode Island easy chair in a private collection (David Conradson, Useful Beauty: Early American Decorative Arts From St. Louis Collections [St. Louis, Mo.: St. Louis Art Museum, 1999], pp. 42–43). The absence of other illustrated examples in the major furniture compendiums of the 1920s and 1930s (i.e. Francis Clary Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time [1902; reprint, New York: MacMillan Co., 1917]; Esther Singleton, Furniture of Our Forefathers [New York: Doubleday, 1913]; Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 3 vols. [Framingham, Mass.: Old America Co., 1928]; Edgar G. Miller, American Antique Furniture, 2 vols. [1937; reprint, New York: Dover, 1966]) suggests that the form was extremely rare. Two chairs of this general form, but with turned stretchers and arms attached to the face of the side seat rails, are shown in Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Furniture and Glass...for the Benefit of the National Council of Girl Scouts (New York: American Art Galleries, 1929), nos. 577, 605. Following that publication, similar chairs began to appear in the advertisements of dealers. Most of the chairs of this type that have appeared in the marketplace are fakes. Like the example in the Chipstone collection, they tend to include parts salvaged from neoclassical lolling chairs and details that are either overstated or incorrectly adapted. These chairs represent a genre of fakes that continue to be bought by collectors, exhibited by museums, and published by furniture historians.

Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., The Arts and Crafts of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640–1820 (Newport, R.I.: Preservation Society of Newport County, 1954), p. 68. For more on the high chest, see Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1988), pp. 268–70, no. 141. The feet of this high chest are very unusual and resemble those on Irish furniture more than Newport work. The authors have not examined this chest. The easy chair shown in fig. 11 illustrates one avenue through which fakers exploited flaws in scholarship. During the middle of the twentieth century, regionalism was a major theme in the American furniture field, and many scholars and collectors ascribed to the theory that all major urban centers produced a similar range of case, table, and seating forms. Often overlooking channels of trade and commerce, this perspective tended to maintain that furniture used or found in a given region was made there. Recent scholarship has refuted this approach in many areas. Leigh Keno, Alan Miller, and Joan Barzilay Freund have demonstrated that Boston chair makers and merchant upholsterers dominated the market for seating furniture in New England and parts of the middle colonies prior to the Revolution (Leigh Keno, Alan Miller, and Joan Barzilay Freund, “The Very Pink of the Mode: Boston Georgian Chairs, Their Export, and Their Influence,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N. H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996], pp. 266–306). Because of this dominance, few Newport easy chairs were made. The authors know of only three authentic examples: one illustrated in Conradson, Useful Beauty, pp. 42–43; one in the Rhode Island Historical Society (Carpenter, Arts and Crafts of Newport, p. 54); and one illustrated in Christie’s Important American Furniture, Silver, Prints, Folk Art, and Decorative Arts, New York, January 18–19, 2001, lot 59.

Michael and Miriam Gratz were prominent members of Philadelphia’s Jewish community. Michael was born in Lagersdorf, Silesia. In 1759, he emigrated from London to Philadelphia, where he joined his brother Bernard in the mercantile business. A decade later, Michael married Miriam Simon. Her father, Joseph, was a Lancaster, Pennsylvania, merchant and business associate of Michael and Bernard (Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone, p. 208.) The couple may have purchased the original easy chair, a set of side chairs, and a dressing table shortly after their wedding in 1769. All of these objects were intended to match an elaborate high chest that Michael may have purchased soon after arriving in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia easy chairs with cabriole legs and arms shaped like those of a sofa rather than the more common double c-scroll variety are rare. Like the fake Gratz chairs, most fraudulent forms are built around the frames of straight-leg chairs. A few authentic Philadelphia easy chairs with sofa-form arms survive including one commissioned by John and Elizabeth Cadwalader (private collection on loan to the Philadelphia Museum of Art); one in the Winterthur Museum; one in a private collection in Milwaukee, Wis.; and one formerly in the Robb Collection (Israel Sack, Inc., American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 10 vols. [Alexandria, Va.: Highland House, 1974], 5: 1208–9).

For more on chairs attributed to members of the Gaines family, see Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks of the New Hampshire Seacoast, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1993), pp. 295–300, nos. 77, 78; and Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Winterthur Museum, 1997), pp. 31–36, nos. 17–19.

Invoice, February 14, 1964. Richards and Evans, New England Furniture, p. 35.

The attribution to Bernard is based on unpublished research by the authors. See J. Michael Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 26, 27 for one of the chairs reputedly used by Washington.

Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Furniture and Glass...for the Benefit of the National Council of Girl Scouts, no. 627. Although the authors have not examined the table from the Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition, it too may be a fake. The shaped beaded skirt is similar to those on many straight-leg Newport card tables. It is possible that an early faker married thin, Boston-style legs to a Newport frame. If so, this would not be the first instance when one fake inspired another. Few eighteenth-century cabinetmakers had rasps, which were difficult and time-consuming to make. First-cut files produced most of the coarse striations found on the interior surfaces of early American furniture. Cabinetmakers typically owned several files ranging from coarse to fine.

Joseph Downs, American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods at the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (New York: MacMillan Co., 1952), nos. 340, 341.

The histories of wear and use manifest on reused components are often inconsistent with their position and use on fakes. Visible discrepancies of this type are useful in identifying fakes.

Barry A. Greenlaw, New England Furniture at Williamsburg (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), p. 152, no. 132.

Invoice, April 15, 1959.

For a description of the traditional “peeling” technique of spindle turning, see F. Pain, The Practical Woodturner (1956; reprint, New York: Drake Publishers, 1974). Modern turning on a high-speed lathe is more akin to scraping than peeling.

For more on Harding, see Luke Beckerdite, “An Identity Crisis: Philadelphia and Baltimore Furniture Styles of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” in Shaping a National Culture: The Philadelphia Experience, 1750–1800, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the Winterthur Museum, 1995), pp. 243–81.

Invoice, November 25, 1958.

Carpenter, Arts and Crafts of Newport, p. 88, no. 60.

Stone, “Life Begins at Fifty,” ix.

For more on this shop, see Alan Miller, “Roman Gusto in New England: An Eighteenth-Century Designer and His Shop,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N. H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 160–211.