Cupboard head attributed to John Taylor, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1640–1670. Oak and pine with pine. H. 31", W. 51", D. 18 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Jim Schneck.) The panels have lozenges that were carved with a V-shaped parting tool, and rondels and scrolls carved with a gouge. This effective but simple carving has no exact cognate in New England joinery, even though incised lozenges were a common motif throughout the region.

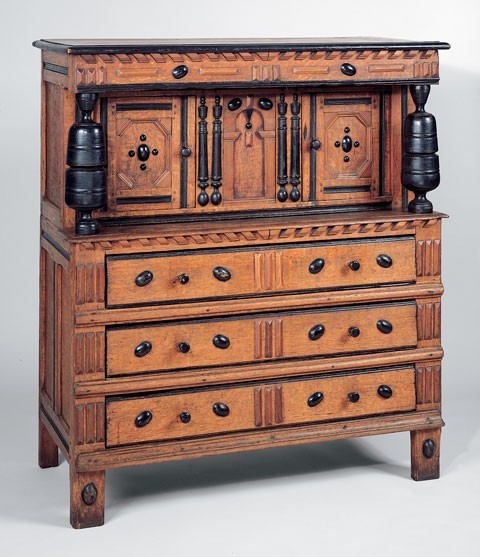

Chest of drawers with doors attributed to the Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger shop tradition, Boston, Massachusetts, 1635–1650. White oak, red oak, chestnut, maple, black walnut, cedar, cedrella, snakewood, rosewood, and lignum vitae with red oak, white oak, chestnut, and white pine. H. 49", W. 45 3/16", D. 23 3/8". (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.) The turnings on this piece are attributed to Thomas Edsall.

Cupboard attributed to the Harvard College joiners, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1660–1670. Oak and maple with pine. H. 51 5/8", W. 45", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Concord Museum.)

Rear view of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 3.

Side view of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 3. Some of the side panels are made of pine rather than oak.

Detail of the dovetailing of a drawer in the cupboard illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail of a pillar on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail of a pair of half-columns on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 3.

Joined cupboard with four drawers attributed to the Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger joinery tradition and the Thomas Edsall turning tradition, Boston, Massachusetts, 1675–1690. Oak, maple, cedar, walnut, and chestnut with oak and white pine. H. 55 5/8", W. 49 1/8", D. 21 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The frieze ornaments, top of the upper case, several small moldings, and the knobs are modern restorations. The original owners of the cupboard were Isaac (1650–1731) and Elizabeth (Tallman) (d. 1701) Lawton of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, who were married in 1673.

Detail of a pillar on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of a pair of half-columns on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 9. These small half-columns differ from those found on the Cambridge group, which are similar to those on the upper section of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of the dovetailing of a drawer in the cupboard illustrated in fig. 9

Joined cupboard, Boston or Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Oak and maple with oak and pine. H. 60", W. 49 3/4", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase funds provided by the Theta Charity Antiques Show.) Two corbels, some applied moldings and plaques, the knobs, and the bottoms of the posts are modern restorations. The pillars are slender versions of those on several cupboards that clearly are part of the Cambridge group.

Detail of the dovetailing of a drawer in the cupboard illustrated in fig. 13.

Rear view of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 13. On most of the cupboards in the Cambridge group, the rear façade of the lower case is sealed with nailed-on boards.

Side view of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 13. On most of the cupboards in the Cambridge group, the side frames of the lower case have one panel rather than two.

Chest of drawers attributed to the Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger joinery tradition and the Thomas Edsall turning tradition, Boston, Massachusetts, 1640–1670. Oak, cedrella, cedar, walnut, and ebony with oak. H. 51 1/4", W. 47 3/16", D. 23 1/16". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of Charles Hitchcock Tyler.)

Joined cupboard, Boston or Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. Oak, maple, and walnut with oak and pine. H. 61", W. 52 1/2", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The pillars, knobs, and some applied moldings and plaques are modern restorations. The cupboard was reputedly found in Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Rear view of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 18.

Detail of the left door of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1. Each door hinges on 1/2" pins set into holes in the top and bottom of the stile. These pins engage holes in the case. The joiner clearly drilled the holes to make the doors recessed on the hinge side and flush with the façade on the other.

Photos showing how the joiner ran the groove for the panel in the outer stile of the left door of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1.

Photos showing how the joiner ran the groove for the panel in the outer stile of the left door of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1.

Photos showing how the joiner ran the groove for the panel in the outer stile of the left door of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the chamfering on the right upper post of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1. The slight chamfer at the juncture of the top rail and the suspended posts is unusual, but it appears to be the result of a mistake rather than a stylistic conceit. This detail is barely discernible and may represent the joiner’s attempt to dress up the posts adjacent to the mistakenly inverted frieze rail.

Detail of an open mortise-and-tenon joint on the underside of the upper right post of the cupboard fragment illustrated in fig. 1.

Joined cupboard with drawers attributed to the Harvard College joiners, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1670–1690. Oak, maple, and cedar with oak and pine. H. 52", W. 46", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, David Stansbury.)

Joined cupboard attributed to the Harvard College joiners, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Oak and maple with oak and pine. H. 53 7/8", W. 46 5/8", D. 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the left corbel of a Cambridge cupboard (overall not illustrated). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The corbel is decorated with the carved letter “I”.

Detail of the middle corbel of a Cambridge cupboard. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The corbel is decorated with the carved letter “M”.

Detail of the right corbel of a Cambridge cupboard. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The corbel is decorated with the carved letter “B”.

Cupboard head illustrated in figure 1 with its restored lower case and upper pillars. The reproduction base and pillars made to display the cupboard fragment are somewhat conjectural, but many features were not difficult to infer; the Stone cupboard (fig. 3) provided the basic design. Decisions about construction and ornament were based on the assumption that the fragment was made before Boston styles influenced the Harvard College joinery tradition. The lower case was decorated with chamfers and carving matching that on the upper case; the drawer front was decorated with planed moldings; and the pillars were based on English examples of comparable date rather than the tapered urns seen on later Boston and Cambridge cupboards. The rear of the lower case was sealed with nailed-on, chamfered boards, and the front corners of the drawer were joined with one large dovetail.

The upper case or head of a seventeenth-century New England cupboard (fig. 1) illuminates a thorny interpretive problem in American furniture history, documenting the transition from an early carved phase of mannerism to a later one characterized by the use of applied ornament. A major stumbling block in this quandary is identifying the precise date at which the applied-ornament style was transmitted from London to Boston. Building upon the pioneering research and attributions of Benno M. Forman, Robert F. Trent has asserted that London-trained joiners Ralph Mason (arrived 1635, d. 1678) and Henry Messinger (arrived 1641, d. 1681) and London-trained turner Thomas Edsall (arrived 1635, d. 1676) introduced the style during the mid-1630s. Some scholars have expressed doubt that the earliest Boston pieces with London-style appliqués (fig. 2) date before the 1650s, but more recent research by Trent supports his hypothesis.[1]

Setting aside this dating controversy, an additional problem resides in assessing the influence of the Boston style on joiners working in surrounding towns in eastern Massachusetts. Many of them came from provincial areas in England and probably were working in the carved style when they arrived in New England in the 1630s or 1640s. Were they or their apprentices influenced by the applied-ornament style in the form of London or Boston case furniture, and if so, when? Answers to these questions may not be forthcoming in every instance. Third-generation colonists commissioned the vast majority of surviving New England mannerist furniture in the heyday of applied ornament. Insofar as many Massachusetts joinery traditions are concerned, no case pieces in this hypothetical earlier carved manner may survive. The cupboard fragment illustrated in figure 1 is a significant exception, expanding both the chronology and vocabulary of the Cambridge joinery tradition.

The Cambridge Paradigm

The furniture attributed to this tradition consists of a small group of cupboards in the applied-ornament style. Trent has asserted that these objects represent the work of three successive Harvard College joiners: John Taylor (arrived 1638, d. 1683), John Palfrey (m. 1664, d. 1689), and Zechariah Hicks, Jr. (1651–1752). As the only group of joiners with an official institutional affiliation, the Harvard College masters were undoubtedly important workmen. According to Taylor’s gravestone, he worked as both a joiner and college butler until his death in 1677. At his death, he owned two pounds ten shillings worth of “Joyners Tools” as well as fifty-eight pounds in cash that he kept in a “great cupboard.” Taylor and Braintree, Massachusetts, joiner William Savell (arrived ca. 1639, d. 1669) worked on the first college building from about 1638 to 1641. The cupboard illustrated in figure 18 has unusual back construction that is related to work attributed to Savell.[2]

The second joiner, John Palfrey, married Rebecca Boardman, whose father William was college cook. Palfrey subsequently trained his brother-in-law William Boardman (1657–1696), who later lived in and may have built the Boardman house in nearby Saugus. Palfrey assumed the oYce of college joiner by 1679, when he made “1 doz. Stooles for College Library.” Later records confirm his status as the institutional joiner in 1683. Palfrey’s inventory taken in 1689 lists “Joyners Tools” and “Timber for Joyner Worke.” His daughter Rebecca married carpenter Joseph Hicks whose brother Zechariah Jr., was the third college joiner. Palfrey’s other daughter Martha married joiner Benjamin Goddard (1668–1748), and the couple moved to Charlestown in 1712.[3]

Hicks was born into a woodworking family in Cambridge. In 1690, he became the college joiner, and his father Zechariah became the college carpenter. After the elder Hicks died in 1702, Zechariah Jr. assumed responsibility for several building projects in Cambridge including the prison (built ca. 1701–1703) and the courthouse (built ca. 1721).[4]

A cupboard that reputedly belonged to Gregory Stone (arrived 1637, d. 1672) of Cambridge (fig. 3) is the cornerstone of this attribution. Like all of the cupboards in this group, it displays a curious mix of retrograde and avant-garde construction and ornamental traits. The upper and lower cases are sealed on the rear surfaces with large, chamfered pine boards nailed to the framing members (fig. 4), a less formal alternative to sealing the cases with feathered panels held in grooves. In addition, the sides of each case have one large panel rather than two or more—a conservative feature in seventeenth-century joinery (fig. 5). The drawer construction of the Cambridge cupboards is similar, although not identical, to that of Boston case pieces in the London style. The front corners of the drawers are joined with one large dovetail (fig. 6), and the rear corners are secured with wrought nails. Each drawer bottom is one large chamfered pine board set into a groove in the front and nailed on the sides and back.[5]

Like their Boston counterparts, the Cambridge cupboards also display a full panoply of accomplished turned pillars and applied ornaments such as half-columns and bosses (figs. 7, 8). Although these components could have been purchased from local tradesmen such as John Gove (m. 1658, d. 1704), who had family and professional ties to all three Harvard College masters, the pillars and appliqués are probably the work of Boston turners.[6]

The Boston cupboard illustrated in figure 9 has pillars (fig. 10) and half-columns (figs. 9, 11) similar to those on case pieces attributed to the Harvard College joiners, but its construction is quite different. This distinctive object has a trapezoidal storage compartment flanked by turned pillars and a lower case with drawers. The edge and base moldings of the lower case relate directly to those on the earliest Boston chests of drawers, although the cupboard probably dates from the 1670s. The drawers of the cupboard have two dovetails at each front corner (fig. 12), a standard feature on Boston drawers of this height (deeper drawers in related case pieces sometimes have three dovetails at each front corner, and shallow drawers occasionally only have one).[7]

The Boston/Cambridge Quandary

Given the proximity of Cambridge and Boston, it should come as no surprise that metropolitan furniture influenced Cambridge work. In most instances, the products of the Harvard College joiners are easily separable from those of their Boston counterparts. Two cupboards formerly attributed to Cambridge are exceptions because they have construction details that differ significantly from those of other case pieces in the group. The example shown in figure 13 has a drawer with one dovetail at each front corner, but the bottom has a shallow chamfer along the back edge (fig. 14). Other atypical details include the framed panels that seal the rear facade of the lower case (fig. 15) and the use of two panels on the side frames of the lower case (fig. 16). The frieze of the upper case, which features three corbels separated by dentil courses, relates most closely to that of an early Boston chest of drawers (fig. 17).[8]

The other cupboard with a related frieze (fig. 18) has a lower case with two doors that are not separated by a muntin; the side frames have one horizontal panel over two vertical ones. The construction of the backs of the upper and lower cases is also unusual. The upper case has one horizontal, feather-edged board that engages grooves on the top and sides and is nailed to an internal rail at the bottom. The lower case has multiple horizontal boards, the outer of which engage grooves in the posts and are nailed to internal rails at the top and the bottom (fig. 19). These nailing rails also function as bearing surfaces for the top of the case and floor of the storage compartment under the drawer. Although the back of this cupboard has no Boston parallel, it relates to the vertically-oriented “clapboard backs” on early oak kasten made in the vicinity of New York City and to the backs of chests attributed to the Savell shops of Braintree, Massachusetts. Given their unusual structural and ornamental details, this cupboard and the example illustrated in figure 13 could be Boston products or late Cambridge pieces influenced by that Boston work.[9]

A Piece of the Puzzle

The cupboard fragment (fig. 1) provides new information on the Cambridge school and the succession of Harvard College joiners responsible for that tradition. It is in remarkably good condition and appears to have an undisturbed surface with accumulated grime but no later resin coatings. Most of the joints have never been disassembled or re-glued, and all the pins and nails are intact.

The fragment is the upper case of a two-part cupboard, and the front posts of its frieze have holes, presumably for the round upper tenons of large, turned pillars. It is unlikely that the posts had pendants because there is no imprint for them, nor is there any glue residue in the holes. The front edge of the top board has a scratch-stock molding resembling two quarter-rounds and a fillet. This same molding appears on the upper edge of the frieze rail, although it is barely discernible because of the shadow created by the top (fig. 22). The maker may have intended this molding to be on the bottom edge and accidentally inverted the frieze rail during assembly. The frieze rail, the two façade muntins, and the lower front rail have a second scratch-stock molding resembling astragals separated by a flat groove—a profile favored by early joiners in Windsor, Connecticut, and later joiners in the Connecticut River towns of western Massachusetts. The scratch-stock-generated quirked bead on the stiles and rails of the doors and framing members of the sides also has parallels in Connecticut River Valley work.[10]

The chamfering of various structural components is even more distinctive. The stiles and rails of the doors and the side and top edges of the framing members around the central panel have chamfers that taper out at each end, rather than those that terminate in ogee-shaped “lamb’s tongues” or shallow V-shaped cuts known as “pips.” Seventeenth-century case pieces with chamfers treated exclusively in this manner are rare. Later cupboards in the Cambridge group differ in having framing members with a combination of edge details including tapered chamfers, stopped chamfers, and scratch-stock moldings. They also have applied mitered moldings on the drawer fronts and the doors and central panels of the upper cases. Whether this departure is the result of Boston influence or indigenous stylistic evolution is not immediately apparent, but simple tapered chamfers are associated with the carved phase of mannerism. This supports the theory that the cupboard fragment represents an early phase of the Harvard College joinery tradition.[11]

Several features of the cupboard fragment link it with later examples in the group. The tenons for the frieze rail and upper side rails are exposed at the top and bottom of each joint (fig. 23). Although these open joints are not visible once the top is nailed in place and the pillars are installed, they are one of the more coarse construction details shared by most of the Cambridge cupboards. Jettied corner posts usually extend below the frieze and side rails, but there is no evidence that the ones on the fragment were shortened at a later date.

Other diagnostic details can be observed in the joinery and orientation of the two doors. Rather than hanging completely in plane with the façade, each door is recessed on the hinged side and is flush on the other (fig. 20). The hinged side is set into a rabbet approximately three-eighths of an inch deep, and the doors rotate on wooden pins. The opposite stile is rabbeted on the back to mate with the rabbet on the adjacent muntin. Three other cupboards attributed to the Harvard College joiners have doors framed and hung in a similar manner (figs. 3, 24). The panels of the doors are trapped in a conventional manner, but the grooves in the stiles do not extend through the ends as they often do in seventeenth-century New England joinery. Evidently, the joiner chopped the mortises in the stiles and then cut the grooves with a conventional plow plane (fig. 21). He started the groove at the surface at one end and slowly worked the nose of the plow down into the groove, ending the stroke in the opposite mortise. Repeated passes of the plane produced a full-depth groove at the far end of the stroke but left some bulk at the beginning which had to be removed with a chisel. The joiner used the same tool to cut one shoulder of each of the door rabbets, but he appears to have used a grooving plane with a deeper setting to cut the other shoulder.[12]

The use of wide pine boards for the top, back, and bottom of the case is ambiguous in an Anglo-American context, but it does attest to the availability of sawn lumber in New England. More significant is the use of nails to attach the backboards to the rear framing members, a quicker and cheaper alternative to trapping them in grooves in the rear stiles and rails.

Ultimately there is little doubt that this fragment is a carved predecessor of the Cambridge cupboards with applied ornament. Although most of the intact examples resemble the Stone cupboard (fig. 3), there are two important and intriguing variants. The first is represented by a cupboard formerly owned by early Boston collector Dwight Blaney (fig. 24) and a similar one in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Both pieces have drawers with planed moldings on their upper and lower edges. It is possible that planed moldings preceded applied ones in the development of the Harvard College joiners’ vocabulary. The cupboard illustrated in figure 25 represents the second variant and is the only Cambridge example with a trapezoidal storage compartment in the upper case and an open shelf below. This design permitted the use of two different pillars—tapering vases above and straight-sided ones below. The use of large panels with V-shaped mitered break-outs and plaques along the centers of all sides is another detail not found on other case pieces in the Cambridge group.

The framing of the storage compartment is also distinctive. To allow the rails to meet the posts at ninety-degree angles, the joiner made the corner posts pentagonal, a technique common on cupboards and trapezoidal joined tables from northern Essex County, Massachusetts. In contrast, the maker of the Boston cupboard shown in figure 9 toe-nailed the rear ends of the horizontal side rails to rectangular rear posts, a crude technique that is surprising in an urban object.

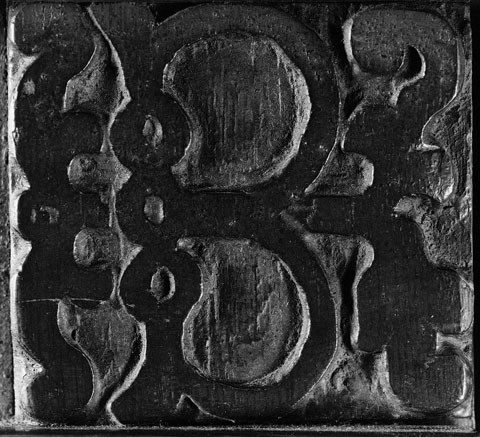

One other Cambridge cupboard conforms to the format of the Stone example (fig. 3) but has three frieze corbels carved with floriated initials (figs. 26-28). These initials resemble mortised initial blocks used in printing, but they also have leafage that relates to the carving on the cupboard fragment (fig. 1). Further analysis of this carving may assist in the identification of other Cambridge case pieces that may surface in the future.

New Insights on Cambridge Joinery

The cupboard fragment with carved decoration probably dates from the working career of John Taylor, the first Harvard College joiner. Presumably, it embodies the style in which he had been trained in England. It also seems likely that the Cambridge school’s transition to a Boston-influenced, applied-ornament style occurred when John Palfrey took over as college joiner about 1670–1675. This coincided with similar stylistic shifts in Essex County, notably in the Symonds shop tradition based in Salem and the Ipswich-Newbury tradition responsible for numerous cupboards and other case pieces. With these dating guidelines in place, a more firm chronology for the development of certain Massachusetts joinery styles can be established. One must keep in mind, however, that some shop traditions persisted in making carved mannerist furniture until well into the eighteenth century and that a stylistic shift in eastern Massachusetts does not necessarily provide a model for Connecticut or western Massachusetts.[13]

Benno M. Forman, “Urban Aspects of Massachusetts Furniture in the Late Seventeenth Century,” in Country Cabinetwork and Simple City Furniture, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Winterthur Museum, 1969), pp. 1–33. Robert F. Trent, “Furniture in the New World: The Seventeenth Century,” in American Furniture With Related Decorative Arts, 1660–1830 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991), pp. 25–26. Doubts about the early date of this object were raised in Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1988), pp. 125–28.

Robert F. Trent, “The Joiners and Joinery of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, 1630– 1670,” in Arts of the Anglo-American Community in the Seventeenth Century, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Winterthur Museum, 1969), pp. 126–33. Peter Follansbee and John D. Alexander, Jr., “Seventeenth-Century Joinery from Braintree, Massachusetts: The Savell Shop Tradition,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 81–104.

Trent, “The Joiners and Joinery of Middlesex County,” pp. 40, 65. Abbott Lowell Cummings, Massachusetts and Its First Period Houses (Boston, Mass.: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1979), pp. 184–86.

Trent, “The Joiners and Joinery of Middlesex County,” pp. 40–41.

Ibid., pp. 127–30.

The Concord Museum—Decorative Arts from a New England Collection, edited by David Wood (Concord, Mass.: Concord Museum, 1996), pp. 1–2.

Robert F. Trent, “The Lawton Cupboard: A Unique Masterpiece of Early Boston Turning and Joinery,” Maine Antique Digest 16, no. 3 (March 1986): 1c–4c.

For more on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 13, see David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston, Tx.: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998), p. 19.

Peter Kenny, Francis Safford, and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), p. 43. Follansbee and Alexander, “Seventeenth-Century Joinery from Braintree,” pp. 81–104.

For more on Connecticut River Valley joinery, see The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut River Valley, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward and William N. Hosley (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985), pp. 192–206; and Philip Zea and Susan Flynt, Hadley Chests (Deerfield, Mass.: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1992).

For a convenient summary of chamfering, scratch-stock moldings, and intersecting framing members, see Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1984), pp. 112–14, 183. When used in combination with more elaborate scratch-stock or planed moldings, chamfers on framing members can intersect in mason’s miters, in true miters, or with biased tenon shoulders. When chamfers are supplanted by combinations of edge moldings, the ends of framing members can have run-out moldings that butt against unmolded sections of complementary framing members achieved by run-outs of scratch-stock moldings that are the equivalent of stopped chamfers.

A cupboard formerly in the collection of Elizabeth and Miodrag Blagojevich and now owned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation also has doors framed and hung like those of the fragment and examples shown in figs. 3 and 25. It is conceivable that the joiner was concerned about the structural integrity of the door stiles, which are 1ž÷¢ inches thicker than the upper and lower rails (see fig. 21). He may have been reluctant to rabbet the back edges of the hinge stiles due to the large pin holes and mortises in those framing members. He may also have intended to chop a lock mortise in the jamb stile. Nevertheless, the layout and hanging of the doors in the earlier cupboards is unusual by period standards. Most joiners used a plow plane to cut grooves for panels. The grooves generally run the entire length of the framing members and are visible as voids on the ends of the stiles. Later cabinetmakers often plugged the voids for cosmetic purposes, but most seventeenth-century workmen left them open. Most grooving planes were used in a plow with an adjustable fence. Although this makes it impossible to prove that the workman used two grooving planes with dedicated depths to cut the rabbets, the uniformity of the two shoulder depths throughout the piece suggests that he did.

Trent, “The Joiners and Joinery of Middlesex County,” pp. 127–28. Michael Podmaniczky conserved the fragment and made the pillars and base.