For the Ohio, tile overmantel formerly in a Woburn, Massachusetts, house, ca. 1888. Tin-glazed earthenware. 20 1/2" x 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Henry Ford Museum.)

Charles Sullivan, View of Fort Harmar from the Virginia Side, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1835. Oil on canvas. 20" x 28". (Courtesy, Peter Tillou Works of Art.)

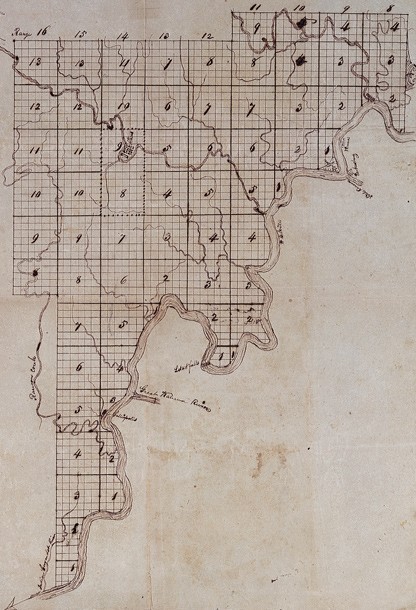

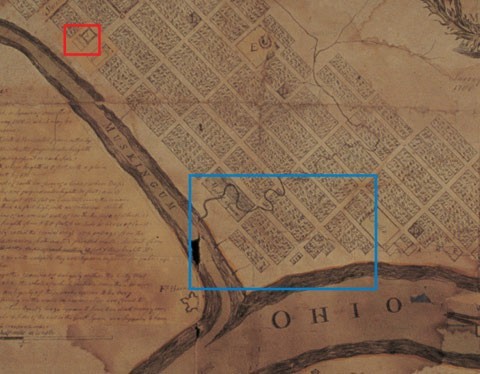

Map of the Ohio Company purchase, ca. 1787. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Ohio Company Papers, Slack Research Collections, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College.)

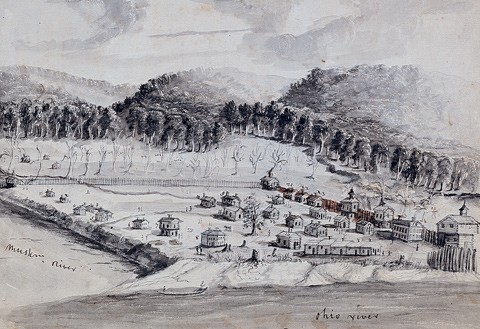

Marietta in 1792, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1848. Watercolor on paper. 7 1/2" x 10". (Courtesy, Hildreth Collection, Slack Research Collections, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College.)

Sawbuck table attributed to Truman Guthrie, Washington County, Ohio, 1790–1800. Tulip poplar and oak. H. 26 1/5", W. 35 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

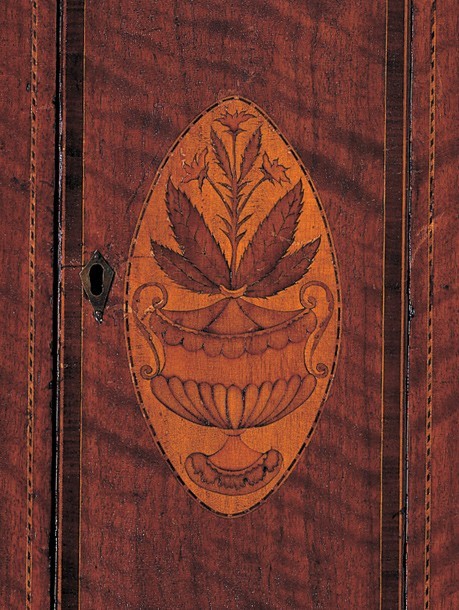

Jonathan Sprague, corner cupboard, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1788. Walnut. H. 70", W. 41 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

Detail of the upper shelves of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

Clock case attributed to Isaac Washington with movement by D. B. Anderson, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1823. Painted tin (case); brass (movement). H. 25 1/4", Diam. 9". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society.)

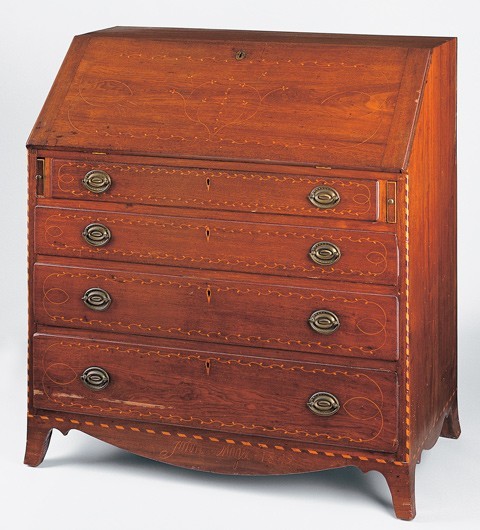

William Mason, desk, Lowell, Ohio, 1800–1810. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 53 1/2", W. 42", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

E. Ruggles, Plan of the City of Marietta, 1788. Engraving on paper. 16 3/4" x 20". (Courtesy, Ohio Company Papers, Slack Research Collections, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College.)

Portrait of Joshua Shipman from Mary Walton Ferris, Dawes-Gates Ancestral Lines: A Memorial Volume (Milwaukee, Wis.: Privately printed, 1931), pl. 21.

Salt box, Marietta, Ohio, 1788–1800. Unidentified wood. H. 12 5/8", W. 6 1/2", D. 3 5/8". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

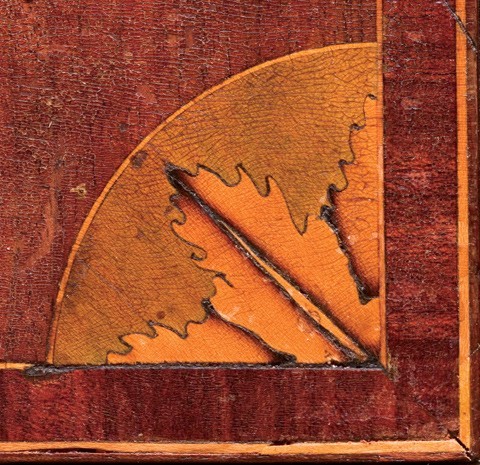

Chest of drawers, Washington County, Ohio, 1810–1820. Cherry and various wood inlays with tulip poplar, pine, and oak. H. 44 3/4", W. 41 5/8", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

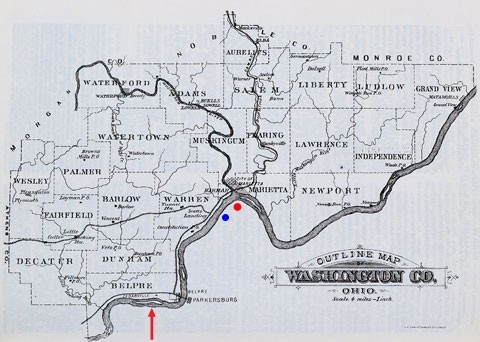

Outline map of Washington County, Ohio, 1881. Lithograph. (Courtesy, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College.) Williamstown is marked in red, Henderson Hall is marked in blue, and the arrow shows the location of Blennerhassett Island.

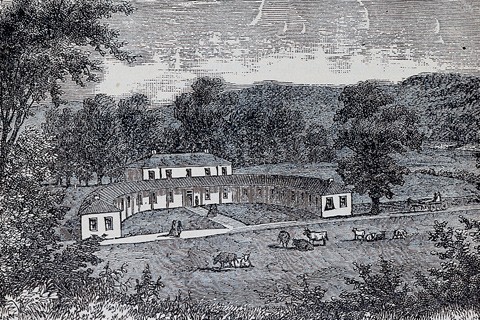

Contemporary image of Blennerhassett Mansion from Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio (Norwalk, Ohio: Laning Printing, 1896). (Courtesy, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College.)

Portrait of John Richardson, Marietta, Ohio, 1800–1820. Oil on canvas. 31 7/8" x 27 1/2". (Courtesy, David O. Richard.) The inlaid frame is original.

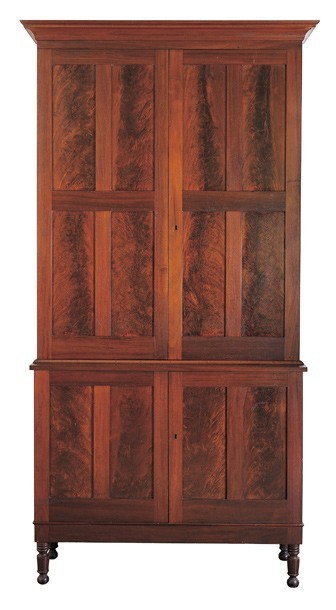

Library bookcase attributed to Richard Rood, Washington County, Ohio, 1810–1820. Cherry and burled walnut with pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Henderson Hall.)

Tall case clock, Washington County, Ohio, 1810–1820. Cherry with tulip poplar. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Henderson Hall.) The dial bears the mark of Ohio clockmaker William Green, but the movement is English.

Sideboard, Washington County, Ohio, 1790–1810. Walnut and various wood inlays with tulip poplar and pine. H. 35 1/2", W. 67 3/4", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society.)

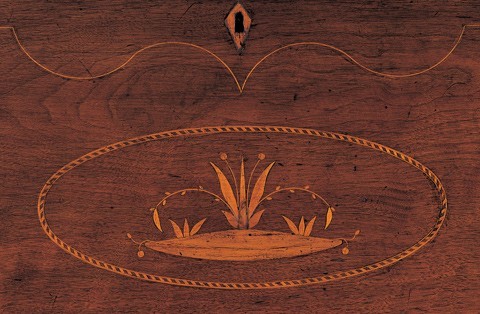

Detail of an inlaid flower on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 19.

Desk, Washington County, Ohio, dated 1819. Walnut and various wood inlays with tulip poplar. H. 47 5/8", W. 41", D. 25 3/8". (Courtesy, Dayton Art Institute.)

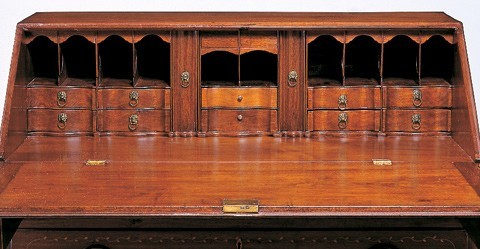

Detail of the interior of the desk illustrated in fig. 21. The lion-head pulls appear to be original.

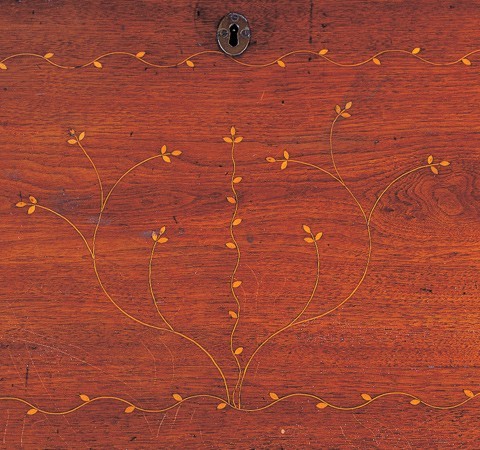

Detail of the inlay on the fallboard of the desk illustrated in fig. 21.

Detail of the inlay on the lower drawer and skirt of the desk illustrated in fig. 21.

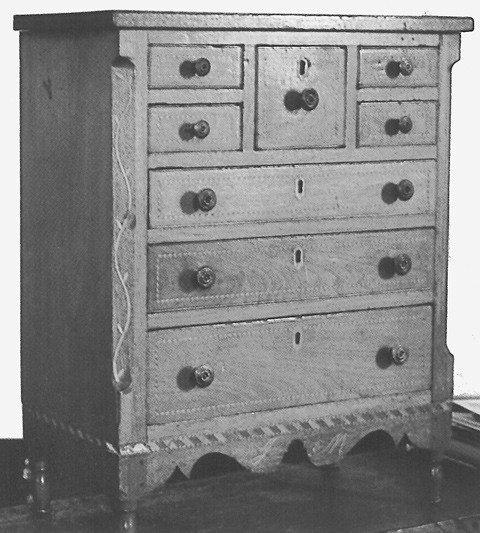

Miniature chest of drawers, Ohio Valley, possibly Washington County, 1815–1830. Walnut and various wood inlays. Dimensions and secondary woods not recorded. (Private collection.)

William Patton, desk-and-bookcase, East Tennessee, or possibly Virginia, 1805–1815. Cherry, walnut, and light wood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 86", W. 41", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Tennessee State Museum Collection: Photo, Bill LaFevor.)

Tall case clock, probably Pulaski County, Virginia, ca. 1810. Mahogany, cherry, walnut, holly, maple, bone, and horn with tulip poplar. H. 108", W. 24", D. 15". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Chest of drawers, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1715–1750. Walnut and light wood inlays with pine. H. 49 1/8", W. 41 1/2", D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 10 showing the Point. Joseph Buell’s tavern is highlighted in red and his home in blue.

Desk-and-bookcase, Washington County, Ohio, 1800–1812. Walnut and various wood inlays with pine. H. 88 3/8", W. 39 3/8", D. 20 5/8". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum.)

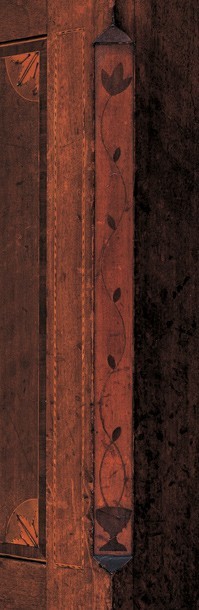

Tall clock case, Washington County, Ohio, 1800–1812. Mahogany and various wood inlays with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 100 1/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 11". (Courtesy, Ohio Historical Society, Campus Martius Museum)

Detail of the inlay on the fallboard of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30.

Detail of the inlay on the hood of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of a corner leaf inlay on the base plinth of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 31.

Tall case clock with movement by John Reynolds, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1800–1820. Mahogany with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 107 7/8", W. 20 3/4", D. 10 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the urn-and-flower inlay on the plinth of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 31.

Tall case clock with movement by Joseph Graff, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1800–1820. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 92", W. 19 1/4", D. 11 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the inverse vine-and-leaf inlay on the base plinth of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 10 showing the population centers. The Point is in blue and Campus Martius is in red.

No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices as that which has just commenced at the Muskingum. If I was a young man, just preparing to begin the world, or if advanced in life and had a family to make provision for, I know of no country where I should rather fix my habitation.

— George Washington, 1788

The colony to which Washington referred was Marietta, the first organized settlement in the Northwest Territory. Established by New Englanders in 1788, it quickly became a bustling frontier town full of merchants, artisans, land speculators, laborers, and, of course, squatters. Despite the primitive living conditions in the early years, residents soon began to refine their homes by purchasing new and fashionable furniture. Not only were the residents buying elaborate and expensive furniture, many were choosing furniture that did not bespeak their origins. In fact, the inlaid furniture so popular with these earliest Ohioans displays a noticeably Southern influence and thus provides a wonderful lens through which to view what became a very complex community composed of a geographically, socially, economically, and politically diverse population. This furniture reflects the choices that life on the Ohio frontier prompted the settlers to make and how these choices shaped both their individual and collective self-images.[1]

"For the Ohio"

As icy winter winds howled through King Street in early March 1786, a group of eleven men gathered in a dimly lit corner of the noisy, crowded Bunch of Grapes Tavern in Boston. Led by Rufus Putnam, who had risen to the rank of brigadier general during the American Revolution, these men formed the Ohio Company of Associates for the purpose of settling the land northwest of the Ohio River (fig. 1). Only recently ceded to the United States, this land included what would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. The company, made up mostly of New Englanders, successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which allowed for the sale of land in the Northwest Territory. Potential settlers could purchase shares of the company at the price of $1,000 per share. Manasseh Cutler of Connecticut arranged the company's purchase of 1,781,760 acres of land for an initial payment of $500,000, with the balance due after the land was surveyed. Because the company paid in depreciated Continental Certificates, the land cost them less than 10¢ per acre.[2]

The settlement was centered on the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers on the western edge of the Appalachian Mountains (figs. 2, 3). It was less than a week's journey down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, and the river offered navigable access beyond what would become Cincinnati, to the Mississippi River, then south to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. The land in the settlement was hilly and broken by numerous creeks and small tributaries feeding into the Muskingum and Ohio. Manas-seh Cutler's 1787 promotional pamphlet, titled An Explanation of the Map of Federal Lands, described the Ohio Company lands as "vastly valuable" with "as rich a soil as can be imagined, and may be reduced to proper cultivation with very little labor." He claimed it would be "difficult . . . to give a just description of the territory under consideration, without the hazard of being suspected of exaggeration."[3]

The first group of settlers arrived in the Ohio Company lands in April 1788 aboard the flatboats Adventure Galley and, appropriately, the Mayflower. They immediately commenced building houses and laying out a town in a grid pattern parallel to the Muskingum River, with town lots and out lots for each settler, as well as several public commons and a fortification. They numbered the roads running north-south, and the roads stretching east-west received the names of Revolutionary War heroes, such as Washington and Marion. They preserved many of the ancient Adena and Hopewell mounds as commons and gave them classically inspired names like Quadra-naou, Capitolium, and Cecilia, and the fortification was christened Campus Martius. The town itself was initially named Adelphia but was changed to Marietta in honor of Marie Antoinette.[4]

Despite a prime geographic location and orderly development, the early years of the Ohio Company were hard. Money was exceedingly scarce, and agriculture was a struggle except along the rivers, where the land was reasonably flat. Efforts to produce cash crops, such as cotton in 1788 and rice in 1789, all failed. As a result, the early settlers depended heavily on the assistance of numerous local squatters, who mostly hailed from Virginia and were of Scots-Irish descent. For example, Isaac Williams, a native of Virginia, generously sold corn at a reduced price during the famine of 1790, and his wife, Rebecca, saved the life of a young Marietta boy who had been bitten by a copperhead snake.[5]

The new settlement grew slowly. By 1789 there were only four hundred residents in Marietta, and by 1791 there were only twenty buildings erected at Campus Martius (fig. 4) The organizational structure of the Ohio Company was partly to blame for the sluggish development. Land sales required the approval of the entire company, and because some of the associates remained in New England, those representatives in Ohio were prohibited from selling additional lands to incoming settlers who had not made prior arrangements. As a result, thousands of immigrants passed by Marietta because they could not buy land and headed farther west, often to Kentucky. Company director Rufus Putnam quickly recognized their plight. "It soon became evident," he wrote, "that some new plan must be adopted to divide lands or the settlement would come to naught." Thus, in February 1789, the Ohio contingent of the Ohio Company passed a resolution granting one hundred acres of land to anyone willing to clear it, erect a house with a brick or stone chimney, plant pear and peach trees, and provide for its defense for five years.[6]

Some immigrants took advantage of this new offer, but settlers were still slow in coming. Manasseh Cutler's pamphlet piqued the interest of many New Englanders, but he had not actually been to Ohio when he published it. Reports from the settlement rapidly countered his claims and diminished interest in the western lands. Timothy Flint of Massachusetts published some of the settlers' experiences in his book Indian Wars of the West: "The country was admitted to be fertile, but was pronounced excessively sickly, and poorly balancing by that advantage all these counterpositives of sickness, Indians, copper-headed and hoop snakes, bears, wolves and panthers."[7]

The rumors of hostile natives probably frightened potential settlers the most. In early 1791 these fears were reinforced by an attack on the Big Bottom settlement thirty miles up the Muskingum from Marietta. Immediately, the residents of many smaller settlements abandoned them to move into Fort Harmar, Campus Martius, or the fortification at the rivers' convergence, called Picketed Point, or simply the Point. Hostilities ensued for the next four and a half years, and immigration virtually stopped. Many settlers even returned to the East. By 1793 there were fewer than five hundred settlers left on the Ohio Company lands. When General Anthony Wayne signed the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, the bloodshed ended, but at a great price. Thirty-eight settlers had been killed and ten taken captive, while the war had cost the company eleven thousand dollars - money it could ill afford to lose.[8]

Immigration resumed after the settlement became secure, but the opening of the Connecticut Western Reserve in 1795 prompted most New Englanders to take up land there. Many of those who ventured west down the Ohio River also bypassed the hilly terrain of Washington County and headed farther downriver into southwestern Ohio and Kentucky, where the flatter bottomlands were better suited to agriculture. By 1800 the population of Marietta numbered approximately 500 and that of the entire county 5,427, compared with Hamilton County's (Cincinnati) population of 15,692.[9]

To friends and family in the East, the Ohio Company settlement must have seemed extremely remote and isolated. At a time when many people never traveled more than a few miles from home during his or her entire lifetime, the journey to the Ohio Country was especially daunting. It took four to six weeks to travel from New England to Simeval's Ferry at the head of the Ohio River in western Pennsylvania. From there, it took six days to descend the river to Marietta. All told, the trip of more than seven hundred miles typically took about two months.

Coupled with this isolation, early reports of wild animals and native hostilities created in the minds of those back East an image of the frontier family living in a log cabin, wearing buckskin, and using beaver pelts as currency. For the earliest settlers, this was not far from reality. Cabinetmaker and architect Joseph Barker described the early homes as "laid up of learge Beech Logs & rather Open" with "puncheon floors & stairs, &c." Thus the earliest furniture was purely utilitarian, as demonstrated by a sawbuck table attributed to Truman Guthrie (fig. 5).[10]

Yet despite the primitive living conditions and economic hardships, even the earliest residents of Washington County craved material goods. This is readily apparent in the corner cupboard illustrated in figure 6. Built by Jonathan Sprague shortly after his arrival, the walnut cupboard appears, at first glance, as crude and utilitarian as the Guthrie table. A glimpse inside the top section, however, reveals finely shaped shelves, clearly meant for the display of ceramics, pewter, or perhaps brass (fig. 7). The desire to own and display elegant objects may seem incongruent with frontier life, but these settlers were not backwoods ruffians - they were educated and worldly, and some were quite wealthy. Many were the sons of prominent New England families who had moved west to make their own fortunes or recoup them after the Revolution, and they brought with them strong intentions of maintaining their accustomed style of living.

The early residents of Washington County did not identify with the local population of squatters, whom they thought vulgar and boorish. Rather, they considered themselves refined citizens bringing some semblance of civility to the "western country." They resisted the frontier stereotypes propagated by eastern travelers and their scathing publications and strove to decorate their homes with whatever "outward symbols of gentility" they could acquire. They also wrote to family and friends back East, praising the state of their society, despite the hardships of frontier life:

The progress of the settlement is sufficiently rapid for the first year. . . . Our first ball was opened about the middle of December, at which were fifteen ladies, as well accomplished in the manners of polite circles as any I have ever seen in the old States. I mention this to show the progress of society in this new world; where, I believe, we shall vie with, if not excel, the old States, in every accomplishment necessary to render life agreeable and happy.[11]

Fueling the settlers' desires for refinement and civility were the goods readily available from local merchants, who were among the earliest and most successful settlers. Account books from the period indicate the availability of a wide range of luxury items. In 1789 the firm of Backus and Kindall sold "japand tinware," as well as cookware, window glass, combs, spices, and a wide variety of foodstuffs, and early newspapers advertised textiles such as calico, printed cotton, silk, and lace, as well as ceramics, paper, quills, perfumes, and pictures.[12]

To acquire these goods, Marietta merchants relied on the Ohio River, which greatly facilitated the transportation from eastern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore. The river quickly became the foundation of the local economy because it provided a crucial trade route from the East to the West (all the way to New Orleans and beyond). Hoping to capitalize on this, a group of investors hired master shipbuilder Stephen Devol to build the St. Clair. In 1801 they loaded the brig with flour and pork, and sailed it down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers into the Gulf of Mexico. The ship stopped in Havana, where it sold its cargo "at advantageous terms," and then sailed north to Philadelphia. There, Captain Abraham Whipple sold the St. Clair and returned to Marietta. Between 1800 and 1808 more than twenty oceangoing vessels were built in Marietta, ranging from 110 to 400 tons. The sale of the ships' cargoes in the South and the sale of the vessels themselves in the East produced huge profits. The settlement was finally beginning to enjoy financial prosperity, but, once again, the community would experience bad luck. President Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 dealt a severe blow to merchants throughout the nation, including Marietta. The suspension of international trade eliminated the need for oceangoing ships, and shipbuilding in Marietta ceased. The economy and the population slumped. Prosperity had increased Marietta's population in 1806 to 1,500, but by the 1820s it had fallen once again to 1,000.[13]

Though Washington County's economy suffered from the loss, the short-lived shipbuilding industry still managed to establish the region as a vital economic link between East and West. It provided the capital necessary for local farmers to expand beyond subsistence to the larger-scale cultivation of livestock, and local entrepreneurs began numerous small manufacturing enterprises, such as distilleries and tanneries. The relative ease of moving surplus livestock and manufactured goods down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers fostered a brisk trade throughout the Ohio Valley, with Marietta as its hub. The Ohio River teemed with flatboats carrying flour, pork, salt, whiskey, and other foodstuffs, as well as lead, lumber, and hardware. "Store boats" flying flags made of calico brought the household goods that local consumers so fervently desired.[14]

The high demand for quality household goods also attracted numerous artisans to the Ohio frontier. William Moulton III and his daughter Lydia were among the earliest settlers in 1788. They emigrated from Newburyport, Massachusetts, and were part of the silversmithing dynasty their family would maintain in Marietta until the late nineteenth century. Other early craftsmen were David Anderson, a clockmaker, and Azariah Pratt, a blacksmith; both men were also silversmiths and were working in Marietta before 1800 (fig. 8). By the 1820s Sala Bosworth was painting landscapes of the Marietta area and portraits of its citizens.[15]

Furnishing the Frontier

Of all the early craftsmen who migrated to the Ohio Valley, the woodworkers were among the most important. The latter literally built Marietta and the smaller settlements on the Ohio Company lands. Cabinetmaker and architect Joseph Barker recalled that "Four surveyors & forty six Mechanics & labourers" went west as part of the earliest groups of settlers, and many of these were probably woodworkers. Between 1788 and 1825 Washington County was home to at least thirty-five carpenters, joiners, and cabinet-makers identified by newspaper advertisements, probate records, contemporary accounts, and surviving furniture. Twenty-seven of the thirty-five worked regularly as cabinetmakers or chairmakers, and two others worked as clockmakers. The remaining six performed various other woodworking tasks, such as house carpentry and joinery, and they may well have produced some furniture. Certainly other craftsmen produced furniture but left no clear record of their work. These artisans were critical in the furnishing of the Ohio frontier. With the exception of basic storage forms, such as chests, little furniture went west with the settlers. Moreover, there is scant evidence that furniture imported from eastern urban centers was present except in the households of a few very wealthy individuals.[16]

Thousands of acres of old-growth forest provided these early furniture makers with an ample supply of wood. Cherry and walnut were the most plentiful primary woods. Probate inventories frequently describe the more expensive furniture as being made of those species, and Joshua Shipman's daybook records the use of cherry and "Black walnut" in higher-end furniture.[17] Mahogany was available in Washington County very early, though it was rarely used. In 1809 Alexander Hill advertised "a stock of the first rate mahogany and other suitable materials for carrying on the Cabinet business effectually."[18]

Tall, straight tulip trees grew in huge numbers and served as the most common secondary wood, although white pine appears to have been preferred by many of the eastern-trained cabinetmakers as a secondary wood in much of the early furniture because of its familiarity to them. Though little pine grew locally, its abundance upriver in western Pennsylvania allowed for very inexpensive importation. In 1808 L. S. Parmelee advertised "For Sale, One Hundred and Twenty THOUSAND FEET of SEASONED WHITE PINE BOARDS and PLANK, By the Large or Small Quantity." John Brophy also advertised pine shingles and boards for sale at Point Harmar, suggesting that he purchased them from one of the numerous flatboats floating down the Ohio. In 1790 James Backus noted in his journal that, along with walnut and tulip, oak, hickory, beech, elm, maple, and ash were growing along the river.[19]

For furniture hardware, these artisans relied on local merchants. It was not until 1829 that the firm of Dobbins and McElfresh advertised the opening of the region's first foundry. Although they specialized in "ALL KINDS OF CASTINGS" in iron, virtually all hardware was imported from the East. J. B. Regnier advertised "A small Assortment of HARDWARE" in 1808. Dudley Woodbridge's daybooks record numerous sales of cabinet hardware, especially chest locks, hinges, and nails. On September 9, 1793, he sold cabinetmaker William Mason of Lowell sixteen knobs, one brass desk lock, two pairs of brass hinges, two cupbord locks, and two and a half dozen screws.[20]

Mason frequently purchased furniture hardware from Woodbridge, who often accepted the cabinetmaker's wares as payment. In November 1789 Woodbridge received a bedstead, for which he credited Mason twelve dollars.[21] Absent these references, Mason remains one of the most readily identifiable of the early craftsmen simply because he described himself in his will as a "Cabinetmaker." He also specified that "all my Cabinet Tools be appraised . . . and one of the boys as they shall choose take them." According to Mason's inventory, his tools consisted of thirty-three "plains of different kinds," twenty-nine chisels, five saws, six files or rasps, three squares, three gauges, one "Oil Stone," seven bits, one stock, one bevel, and one adze. Probate records indicate the widespread ownership of basic woodworking tools such as saws and chisels. Mason's sizable collection, however, suggests that he made relatively complex furniture forms, such as the desk illustrated in figure 9.[22]

Although Mason lived and worked in the outlying settlement of Lowell, most of the early furniture makers established their shops on or near Third, Ohio, Greene, and Front Streets, in the part of Marietta known as the Point (fig. 10). Situated at the intersection of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers, the Point was ideally suited to serve as the commercial center of town. Here, merchants opened their stores and many craftsmen set up their shops, all with easy access to the river traffic.

The output of these craftsmen was significant. A survey of probate records reveals that between 1788 and 1825 the amount and type of furniture in the typical household grew dramatically. During the first years of settlement, the average household contained 1.8 pieces of furniture. By 1800 this number increased to 3.1, and it doubled by 1805 and again by 1810. Between 1821 and 1825 the average household had twenty-six pieces of furniture, which included 3.4 tables, 13.4 chairs, and 2.6 pieces of case furniture. By 1815 approximately one-third of Washington County probate inventories list complex case forms such as bureaus and desks.[23]

More interesting is the considerable increase of furniture forms appearing in probate records. The earliest inventories include only the furniture of necessity: plain tables, common chairs, bedsteads, and stools. Shortly before the turn of the century, case pieces, such as chests of drawers and clothespresses, begin to appear. The opening decade of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of specialized forms, such as breakfast and dining tables, and more complex forms, such as desk-and-bookcases. Estate inventories after 1810 contain a veritable smorgasbord of sophisticated furniture: sofas, card tables, tea tables, "pillar and claw" tables, desk-and-bookcases, tall case clocks, clothespresses, and sideboards.

The daybook of cabinetmaker Joshua Shipman (fig. 11) provides further evidence of the increasing quantity and sophistication of furniture present in early Washington County. A native of Connecticut, Shipman arrived in Marietta in 1790 and set up shop along the Muskingum near Campus Martius. With the coming of peace in 1795, he moved his home and shop down the Muskingum to Front Street, between Washington and Sacra Via. Though Shipman's daybook covers only a few years (August 1796 through November 1803), it provides a record of the furniture he made during the crucial period following the Indian war, when Marietta's shipbuilding industry began to expand. During this period, the economy flourished and residents actively sought stylish furniture to fill the larger homes they were building.

Early on Shipman recorded the construction of complex furniture forms. In February 1797 he charged Charles Greene £5, or $16.67, for "A Beaurow." The term "bureau" was first used in the United States about 1792 and typically described a four-drawer chest with French or straight bracket feet. The high price Shipman charged indicates that the chest was probably of cherry or walnut and may have had inlaid or veneered decoration. Later that same year he sold Harman Blennerhassett a clothespress valued at £6, or $20.00. Shipman's daybook also refers to his production of specialized furniture forms. He made breakfast tables as early as 1796, and dining tables and chairs by 1797.[24]

Shipman’s daybook clearly illustrates the significant contribution local artisans made to the refinement of early Ohio frontier life. Between August 1796 and January 1799, the period the daybook records most completely, Shipman produced seventy-three pieces of furniture, ranging from a three-shilling common chair to a dining table priced at £2.8, or $8.00. Since he was only one of at least eleven carpenters and cabinetmakers working in Washington County before 1800, one can surmise that the quantity of furniture produced during this period must have been considerable. More important, however, is that the daybook of Joshua Shipman and the evidence provided by probate records portray a frontier settlement where sophisticated, stylish furniture was produced and owned much earlier than has been traditionally believed.[25]

The Southern Influence

The surviving furniture of early Washington County reflects the demands of a community concerned not just with function but also with fashion. For example, the shell carving on the hanging salt box illustrated in figure 12 elevates it above mere utility. Further, it draws the expected stylistic connection to the community's New England origins.

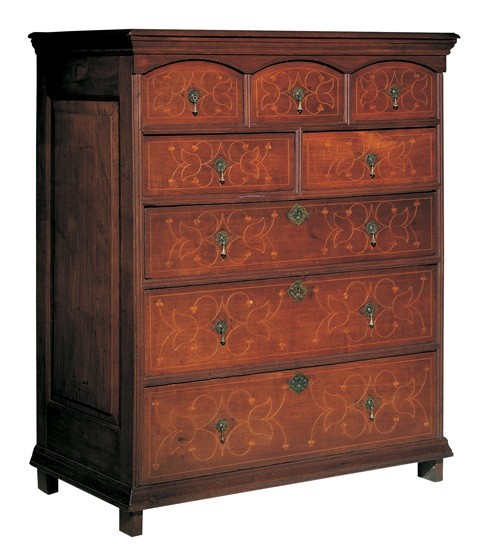

Similarly, while the bureau or chest of drawers shown in figure 13 served the practical purpose of storing clothing and other textiles, the elaborate inlay enlivened the chamber in which it stood. This chest, however, seems stylistically out of place. The rich variety of inlays—stringing, multiwood banding, quarter fans, a half fan, compass stars, and ivory escutcheons — and the exuberance with which it was applied have closer precedents in furniture from western Maryland and the Southern backcountry than that from New England. Moreover, the somewhat exaggerated trilobed profile of the skirt has parallels on Southern chests. By the time this chest was made, the population of Washington County had changed significantly from its founding and now included a very strong Southern contingent.

The first 47 Ohio Company settlers were of New England origin, as were 606 of 663 land purchasers between 1788 and 1792; however, the Indian war and the opening of the Connecticut Western Reserve dramatically altered immigration patterns by curtailing the influx of New Englanders. Many of the new settlers in the Ohio Company lands came from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, and the deeds recorded in 1799 indicate that non-New Englanders acquired almost half of the land sold to immigrants. By 1810, when Paul Fearing enumerated the county for the federal census, the multiregional makeup of the population was clear. He identified 1,001 heads of household, and though the census would not record birthplace until 1850, historian Wayne Jordan drew on other sources and identified the probable origins of 627 of these heads of household. Jordan's research showed that only 367 heads of household were of New England origin, while 86 came from Pennsylvania, 75 from Virginia, 23 from New Jersey, 16 each from New York and Maryland, 2 from Delaware, and 42 from foreign countries. Using an average of 6 persons per family, Jordan then calculated that only 2,202 of the 5,991 residents of Washington County were from New England, while 1,308 were from other states, and 252 were from foreign countries. Of the 374 unidentified heads of household (2,244 persons), most were probably farmers and laborers from Pennsylvania and Virginia whose lives were not as well documented as the earlier New England settlers, who created most of the historical record.[26]

Washington County, however, was more than merely a melting pot of immigrant settlers. It was a central point in a vast web of economic and social relationships connecting southeastern Ohio to western Pennsylvania, western Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and beyond. The account books of Marietta merchant Dudley Woodbridge record business transactions with customers throughout western Virginia, Kentucky, and as far away as Tennessee and Missouri (fig. 14).[27]

Closer to home, Marietta had strong ties to the communities on the Virginia side of the river, such as Williamstown and Parkersburg. The Virginian squatters had proven critical to the survival of the earliest Ohio Company settlers, and later, residents on both sides of the river would participate in what was, for all intents and purposes, a joint economy; farmers and merchants north and south of the Ohio mutually engaged in the river trade. Early newspapers of the area catered to settlements on both sides of the river. With names like the Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald and simply the Western Spectator, these newspapers carried advertisements for craftsmen and merchants in Marietta, Belpre, Williamstown, Parkersburg, and throughout Washington and Wood Counties. In the March 19, 1819, issue of the American Friend, A. Walters advertised that he had "established himself in Parkersburgh, Va. near the public square where he carries on the [cabinetmaking] business in all its various branches." As a result, cabinetmakers north and south of the Ohio frequently had customers who lived on the opposite shore.[28]

One such customer was Harman Blennerhassett, the wealthy Irish immigrant who, in 1798, moved to an island in the Ohio River between Belpre, Ohio, and Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). Though they lived on the boundary between the two states, Harman and his wife, Margaret, were technically Virginians, and their home was a monumental plantation mansion. Built between 1798 and 1800, their house measured 186 feet from side to side and encompassed a central structure, with two wing buildings connected by piazzas, and more than seven thousand square feet of living space (fig. 15). Access to the property was provided by a ferry operated by one of the Blennerhassetts' slaves, Moses, between Parkersburg and the island's formal north shore entrance. The lavish estate also included a stately English garden. Harman Blennerhassett claimed, "The houses and offices I occupy stand me in upwards of $30,000, not mentioning the gardens and shrubbery, in the English style, hedges, post fences, and complete farm-yards, containing barns, stables, overseers' and negro houses."[29]

The Blennerhassetts spent money just as liberally furnishing their island home. They filled rooms with Turkey carpets, European curtains, oil paintings, and printed wallpapers. Mr. Blennerhassett's library consisted of thousands of volumes. The drawing room included black walnut paneling from floor to ceiling, and many doors were also made of walnut and adorned with silver knobs. Although the Blennerhassetts imported some furniture from the East, such as a set of twelve side chairs and two armchairs made by the Findlay brothers of Baltimore, they also patronized local artisans, including Marietta cabinetmakers Joshua Shipman and John Richardson (fig. 16). In 1806 Mr. Blennerhassett sent a letter to Dudley Woodbridge Jr.: "Tell Mr. Richardson I wish him to bring down the chair backs as soon as he can come. I shall try then to engage him to furnish us with a bedstead and a small chest of drawers."[30]

The Henderson family also patronized local cabinetmakers in furnishing their house, which was located a few miles upriver from Blennerhassett Island, near Williamstown on the Virginia shore. A library bookcase attributed to Richard Rood (fig. 17) and a tall case clock with a dial signed "Wm. Green Marietta, Ohio" (fig. 18) are among the original furnishings used in Henderson Hall. The presence of Ohio-made furniture south of the river is significant, as is the appearance of a "sugar stand," a distinctly Southern form, in the 1823 estate sale of Abigail Demmings of Marietta. Traditional history has portrayed the Ohio River as the barrier separating the slave South and the free North, but clearly the story is more complex. This oversimplified dismissal of geography belies the level and depth of interaction between river families. The river acted as a unifying force between these settlements, providing both with a vehicle to acquire what they needed and to sell what they cultivated or manufactured. However, a deeper relationship evolved between the residents of southeastern Ohio and western Virginia that transcended their economic integration. Documentary evidence indicates that settlers engaged in frequent and intimate social interaction. Residents of both Washington and Wood Counties participated in joint hunts for wolves and other predators that endangered their livestock, and Manasseh Cutler recorded that he saw New Englanders from Marietta and Virginians worshiping side by side at Campus Martius. Clearly, the river settlements formed an economically and socially cohesive community, and this, in combination with the growing numbers of Marylanders and Virginians relocating to Washington County, resulted in furniture with a strong Southern accent.[31]

As exemplified by the aforementioned chest (fig. 13), the Southern influence on Washington County furniture is most clearly visible in inlaid decoration. The sideboard illustrated in figure 19 dates to about 1800 and is one of the earliest examples made in Washington County; the form does not appear in the probate records surveyed for this study until after 1810. The case is walnut rather than mahogany, the wood typically used for sideboards, and its unusual design and drawer configuration suggest that the maker had little experience in making this furniture form. The end bays consist of a single drawer with pulls at either end surmounted by a smaller drawer flanked by knife drawers. Although simple in design and provincial in execution, the sideboard displays a variety of inlays, including stringing, cut-corner inlay on the drawers, and short vines that curve up from the tops of the half ovals on the legs. Each vine has a bud, fine leaves, and a stylized flower (fig. 20). The fan inlays in the spandrels of the center section, small size, and overall proportions of the sideboard point to a possible Maryland influence.[32]

Other examples of early inlaid furniture provide further evidence of a significant Southern influence in locally made furniture. The desk illustrated in figure 21 is one of the most sophisticated pieces of early Washington County furniture. Its gracefully curved skirt and French feet were almost certainly laid out with patterns, and its joinery and proportional formulas are the product of a very competent individual or shop. The four drawers, for example, are graduated in one-inch increments and their corners are joined with finely cut dovetails. As one might expect, the number of dovetails securing the frames increases with the size of drawers; the top has four at each corner, the second five, the third six, and the bottom seven.

The interior of the desk is also constructed with considerable precision (fig. 22). The writing compartment contains a central prospect with two serpentine drawers topped by pigeonholes, flanking document drawers with toed-back molded faces, and two bays with two pigeonholes over stacked serpentine drawers. The right and left bays are 6 1/2 inches wide, and the inner bays are 6 3/8 inches wide. The upper drawers in each bay measure two inches from top to bottom and are one-quarter inch higher than those below. Although the maker of this desk remains unknown, he may have trained in Pennsylvania or the Southern backcountry. Similar interiors are found in desks made in Philadelphia, western Maryland, the Shenandoah Valley, and the Piedmont and western regions of the Carolinas.

The most striking feature of the desk, however, is the very bold use of inlay, including the light and dark wood banding and the meandering vine and leaf decoration that covers the entire façade of the case and the drawer fronts. The fallboard has similar ornament as well as a large foliate sprig at the center (fig. 23). Such enthusiastic use of inlay again defies the New England origins of the settlement. Recalling the elaborate foliate inlay used in Maryland and Virginia, the desk instead speaks to the growing number of Southerners settling in the region.

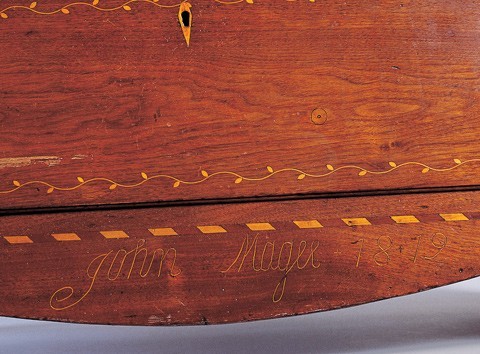

Inlaid on the front of the skirt is "John Magee—1819" (fig. 24). Although the desk has often been attributed to him, Magee was more likely the owner. The tradition of inlaying owners' names on case forms is relatively common on furniture from Pennsylvania and the Southern backcountry. Little is known of Magee, aside from that which can be culled from census and tax records and a few references in local histories. He was a farmer of Irish descent who settled in Washington County very early. In 1793 he was present during the capture of Major Nathan Goodale by local Indians, and during the war he served at the garrison in Belpre. In 1810 his name appears on the tax lists in Marietta Township, and the 1820 federal census lists him as a farmer in Salem Township, where in 1825 he taught Sunday school. Magee may have been a stonemason; in 1832 he was hired to prepare a millstone for the steam-powered gristmill of S. N. Merriam in Salem.[33]

Magee may also have owned the miniature chest of drawers illustrated in figure 25. The two lobes of the skirt are inlaid with the letters "J" and "M," which may be for John Magee. Clearly by a hand different from that which made the desk, the miniature chest is made of walnut and has turned feet and an elaborately shaped skirt, bold banding, and vine and leaf inlay running up the canted corners.

Meandering vine-and-leaf inlay appears on late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century furniture from a very wide geographic area. Several desks and bureaus made in southwestern Pennsylvania have vines and leaves running up canted corners, but the motif appears more often on Southern case furniture, particularly that from central and eastern Kentucky and eastern Tennessee (fig. 26). Moreover, slight variations of the pattern, most of which include flowers, also appear in western Maryland, the Shenandoah Valley, western Virginia, western North Carolina, and as far south as the Georgia Piedmont and Louisiana (fig. 27).[34]

Side-by-side comparisons of vine-and-leaf inlay from Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee suggest they are more closely related than the vine-and-leaf inlay of Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, and Louisiana, though those regional variations are undoubtedly related as well. Differences in the fullness and spacing of the leaves and the length of the vine curves indicate the hands of numerous craftsmen. Without a common source for the purchase of vine-and-leaf inlay, just how this pattern pervaded such a wide geographic area is not entirely understood. The appearance of the pattern throughout the upper Ohio River Valley suggests that river trade between western Pennsylvania, southern Ohio, and northern Kentucky played a vital role. The migration of cabinetmakers may also have transmitted this motif from one region to another. One possible origin of the vine-and-leaf is the line-and-berry inlay so popular in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in the middle of the eighteenth century (fig. 28). It is possible that as the line-and-berry migrated west via the Ohio River and south through western Maryland and the Valley of Virginia, it evolved into the two variations of the meandering vine-and-leaf.[35]

Reflecting the changing demographics, a widespread trade network, and close social ties to communities south of the Ohio, the inlaid furniture of Washington County shows a clear Southern influence. This fact, alone, begins to chip away at the long-held myth that Marietta was a transplanted New England village. The plot thickens, however, because not just Southern émigrés purchased inlaid furniture. In fact, two significant pieces of surviving inlaid furniture both have a history of ownership by a New England family—that of Joseph Buell.

Joseph Buell and the Politics of Furniture

After Sergeant Joseph Buell completed his three years of military service in the West in the fall of 1788, he returned home to Killingworth, Connecticut. Before his departure from Fort Harmar, where he had served most of his enlistment, he made plans to return to the newly settled lands north of the Ohio River. In August he noted in his journal: "27th. Judge Symmes, of New Jersey, landed here, on his way to Miami [Cincinnati], with a number of families. I purchased four hundred acres from him, lying in the reserved township, at fifty cents an acre. Paid him one hundred dollars, the balance in a year."[36]

During Buell's six months in New England, he married Siba Hand and prepared for his new family to return to the Symmes settlement in southwestern Ohio with the family of cabinetmaker Joshua Shipman. Both men's plans changed, however, and the twenty-eight-year-old Buell set out for Ohio with his brother, Timothy, and his friend and military associate, Levi Munsell. They arrived in Marietta and, after a brief stay, began their journey to the Symmes settlement, only to return for fear of an Indian attack. Buell and Munsell abandoned plans of going farther west and instead erected a large frame building at the corner of Front and Greene Streets, which they opened as a tavern called the Red House.[37]

Life in Marietta proved good for Buell. His wife joined him in 1790, and the tavern prospered. Its location at the Point made it the favorite watering hole of local artisans and merchants as well as the flatboatmen with whom they did business. In 1801 Buell built his family a brick home, allegedly the first in the settlement, near the Red House at the corner of Greene and Second (fig. 29). The tavern became even more successful when shipbuilding began in Marietta in 1800, as the Point evolved into the commercial center of Marietta. While the end of shipbuilding seriously affected business, Buell had, by this time, invested his growing fortune in thousands of acres of Washington County land. On his death in 1812, Buell owned seventeen lots in Marietta, containing more than twenty buildings, and thirty-eight lots outside the city.[38]

Because of his military service and his financial success, Joseph Buell quickly became a leading citizen in the young city. He received an appointment of major general in the local militia and served as an Ohio state senator from 1803 to 1805 and as an associate judge in the Court of Common Pleas from 1803 to 1810. His most famous public role was his seizure of boats belonging to Harman Blennerhassett, which were to be used in his alleged conspiracy with Aaron Burr to incite revolution in the far West.[39]

In addition to large tracts of land and a host of public honors, Joseph Buell also amassed a sizable estate valued at more than $22,000. According to his inventory, the vast majority of his wealth was tied up in land (nearly $9,500) and in notes (nearly another $9,500). Buell had less than $100 in cash at the time of his death. In the years before he died, Buell lent thousands of dollars to dozens of people, and seemingly few paid him back. In March 1809 Buell published a notice in the Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald: "PAY OR BE SUED THE LAST TIME FOR ASKING I am under the necessity of calling on all persons indebted to me, to call and make payment; those who do not comply with this request will be introduced to the sheriff or constable, without respect to persons." Such attempts to recoup lent money met with little success. Between 1799 and 1801 not a court term passed without Buell's suing at least one person for money owed him.[40]

Land speculation, as well, did not prove very fruitful for Buell. He expressed the sentiment in a letter to his son, Daniel, whom he had sent to Connecticut for schooling. Daniel responded, "I am well aware of the difficulty of turning property into money in the western country, and also of its very great scarcity." For the Buell family, cash was tight, and despite their wealth, Joseph feared they would be unable to send Daniel to college.[41]

Regardless of the Buell family's lack of specie, Joseph managed to accumulate an impressive array of household goods. Along with a large collection of books, silver, chinaware, glass, and bedding and other textiles, Buell's 1812 inventory lists more than 180 pieces of furniture. Included were 3 clocks, 15 case pieces, 13 tables (5 of which are dining tables), and 109 Windsor chairs (in light brown, dark brown, "chocolate," green, black, and yellow). Nearly all the case furniture is described as being of cherry or walnut and their value ranged from eight to fifty dollars. That Buell invested so much money in furniture certainly suggests that he relied on his credit with others just as much as they relied on their credit with him. It also indicates his very strong desire to create an orderly, comfortable, and genteel home for his family.[42]

While Buell's large collection of expensive furniture advertised his wealth and gentility, it also signified that he was knowledgeable about the latest furniture trends. He owned Windsor chairs in a range of colors, but more important, in different shapes. Most of Buell's Windsors were probably bow backs, and some were described as such. For example, "5 Brown Windsor Chairs (round backs)" were valued at $5.00. However, also listed were "6 Brown Windsor Chairs square Tops" valued at $7.50 and "1 Great Windsor Chair square top" at $1.75. Square-backed Windsor chairs achieved popularity in Philadelphia at the end of the eighteenth century, and by the early nineteenth century they had reached Pittsburgh. Buell's new Windsors would have been considered very fashionable in southeastern Ohio by 1810.[43]

Buell was also well aware of the local taste for inlaid furniture. His inventory lists "1 Walnutt Bureau (inlaid)" valued at eighteen dollars. Fortuitously, the desk-and-bookcase and tall case clock listed in his inventory survive, and both are covered with elaborate inlay (figs. 30, 31). The desk-and-bookcase is made of walnut and burled walnut veneer. Its ornament features stringing and banding on the drawers, doors, and desk fallboard, several paterae including large ones on the bookcase doors, numerous geometric motifs, and meandering vine-and-leaf. On the fallboard, the use of round termini, rather than leaves or flowers, may represent a connection, albeit distant and somewhat filtered, with furniture traditions from Chester County, Pennsylvania (fig. 32).[44]

The inlay on Buell's tall clock case (fig. 33) is just as complex, but it is far more sophisticated. Several of the inlaid ornaments are likely from Baltimore, Maryland, or, at the very least, closely related to those produced in that city. The rosettes and the bird on the hood are similar to those on furniture associated with the shop of Baltimore cabinetmakers John Bankson and Richard Lawson. The foliate motifs in the corners of the case door and the front panel of the base also resemble those used by that firm, as well as those on a tall clock case with a movement signed "John Reynolds, Hagerstown" (figs. 34, 35). Further, the central urn-and-leaf motif on the door is nearly identical to that used on a clock signed by Joseph Graff, also of Hagerstown (figs. 36, 37).[45]

The ornament on the clock includes meandering vine-and-leaf inlay, but the maker of the case added a twist by creating an "inverse" vine-and-leaf running up the canted corners of the case and base. He achieved this effect by veneering a light-colored wood on the canted corners and then inlaying the vine-and-leaf in walnut (fig. 38). A similar feature is found on a group of Norfolk, Virginia, furniture, but there the makers merely incised the lightwood veneer to reveal the dark wood beneath.[46]

In a small frontier community where cabinetmakers and patrons interacted economically and socially on a daily basis, the desk-and-bookcase and clock must have been the result of a significant collaboration between Buell and the maker or makers. The question then arises, why did Joseph Buell, a settler from Connecticut, commission multiple pieces of expensive furniture with such strong Southern influence? The simplest answer is that such furniture was the most fashionable in the area. Widespread trade throughout the Ohio River Valley and the influx of settlers from Maryland and Virginia who came to Washington County after 1795 may have completely transformed local fashions.

Changing fashions undoubtedly played a significant role in Buell's choice of furniture, as his purchase of new square-backed Windsor chairs indicates. But the ornamentation on his tall case clock and desk-and-bookcase represents such a dramatic departure from his Connecticut origins that one wonders if this furniture reflects something deeper than just the latest taste. It may be that Buell used this furniture to construct a new image of himself, one separated from his New England roots and much more connected to his new home along the Ohio River.

Buell's choice of where to live in Marietta reinforces this idea. Rufus Putnam and other older members of the community, most of whom were conservative New Englanders, built their homes in Campus Martius along the Muskingum, one mile up from the Ohio. By contrast, younger men like Buell often settled at the Point, among the working class, and at the center of the business district (fig. 39). Thus in early Marietta, the population split geographically, and this geographic schism occurred very nearly along generational lines.[47]

This physical divide quickly developed into an ideological rift. For the older settlers, such as Putnam, the "western country" provided an opportunity to rebuild lives that had been greatly disrupted economically, politically, and socially by the American Revolution. They looked to the new settlement for order and stability, and to this end, they embraced the federalist vision of an American empire expanding westward, but rooted in the East. The early settlers considered the early American West, and especially the Ohio River Valley, as a crucial part of the growing national economy, and they wanted to stake their claim. Moreover, they saw their settlement as a chance to shape the future of all western settlement. In An Explanation, Cutler professed that Ohio was to be a "wise model for the future settlement of all the federal lands." To accomplish this, they believed they must remain under the auspices of a strong federal government, and as surveyor general, Putnam was the government's local representative.[48]

Most of the younger generation of settlers had little connection to the Ohio Company and its grandiose vision. These men were the artisans, tavern keepers, merchants, and laborers who formed the economic backbone of the settlement. They viewed the Ohio Company settlement as simply an opportunity to make their own way in the world and as a place to build a home and raise a family. They were a socially and economically diverse group that largely distrusted the federalist (and probably paternalistic) leadership of the older generation at Campus Martius. The postwar influx of Southerners, most of whom were Jeffersonian Republicans or backcountry settlers with a general suspicion of the federal government, caused the diverging ideals of those at Campus Martius and those at the Point to rend the community in what historian Kim Gruenwald dubs "the revolution of 1800." As a result, Putnam was replaced as surveyor general and local control was established with Ohio statehood, both in 1803.[49]

Amazingly, many New Englanders, like Buell and future Ohio governor Return Jonathan Meigs Jr., sided with the Republicans, despite owing much of their political success to Rufus Putnam. Although Buell's wealth and landholdings rivaled those of anyone at Campus Martius, he must have felt a stronger connection to his friends and neighbors at the Point, who, like himself, had worked hard to make something of themselves in the vast wilderness. Perhaps his pride in his own accomplishments in the "western country" outweighed his loyalty to the antiquated system of patronage that the older generation of settlers embodied. Buell's political realignment may have been only one symptom of a much more dramatic shift in his self-image.[50]

Though he may have been born and raised in New England, after 1803 Joseph Buell was technically an Ohioan and may have begun to view himself as such. His abandonment of his New England patron and his participation in the push for Ohio statehood certainly seem to indicate this. More tangible evidence, of course, covers the surface of his desk-and-bookcase and tall case clock. Certainly, the location of Buell's home, within sight of the Virginia shore, and his constant business and social interaction with people from Virginia, Maryland, and other regions of the South may have shifted his stylistic reference point away from the fortified walls of Campus Martius, where a puritanical conservatism still held sway. It seems, though, that Buell's stylistic shift was a more conscious one and, along with his political conversion, was indicative of his burgeoning Ohio identity. He may have commissioned the inlaid furniture as external props to reinforce this new identity. Likely situated in his front parlor and in his office, these objects reminded Buell and his fellow settlers who saw them that, despite their origins, their home was Ohio.[51]

Although not to the degree that Frederick Jackson Turner proclaimed, the Ohio frontier did have a democratizing effect on those who settled there. On arrival, everyone faced the difficult task of clearing land and building a home, but after years of hard work and entrepreneurial efforts, the social hierarchy had been somewhat rebuilt. Now, in the place of lineage and patronage stood wealth and status, embodied in material goods. Men like Joseph Buell could cast off the yoke of aristocracy and assert their own position in society through the purchase of stylish furniture. It is no accident that the political revolution of 1800, which sounded the death knell of the old guard of the Ohio Company, coincided with the increased appearance of elaborately inlaid furniture. Perhaps to some, such furniture became the weapon of choice in the cultural revolution that marked the beginning of an Ohio identity.[52]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am extraordinarily grateful to numerous people who helped during the course of my research, including John Briley, Charles Carroll, Wendy Cooper, Hollie Davis, Cliff Eckle, Katherine Hunt, Brock Jobe, Sally Kurtz, Rebecca Poe, Sumpter Priddy III, Bill Reynolds, Linda Showalter, Ray Swick, and Katherine White. This article is dedicated to the memory of Jane Sikes Hageman, a pioneer in her own right, who laid the groundwork for all future research into Ohio furniture and its makers.

Jared Sparks, The Writings of George Washington, 12 vols. (New York: Harper Brothers, 1848), 9: 385.

The Ohio Company was unable to raise the necessary money for the second installment on the purchase. They therefore retained only the land that had already been paid for, which amounted to about 750,000 acres.

Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D, edited by William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler, 2 vols. (Cincinnati, Ohio: Robert Clarke and Company, 1888), 2: 396–97 (An Explanation of the Map which Delineates that Part of the Federal Lands Comprehended Between Pennsylvania West Line, the Rivers Ohio and Scioto, and Lake Erie).

History of Washington County, Ohio (Knightstown, Ind.: H. Z. Williams and Brothers Publishers, 1881), pp. 47–54.

The struggles of the Ohio Company are detailed in Andrew R. L. Cayton and Paula R. Riggs, City into Town: The City of Marietta, Ohio, 1788–1988 (Marietta, Ohio: Marietta College Dawes Memorial Library, 1991), pp. 47–79. For Williams, see S. P. Hildreth, Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examination of the Ohio Valley (Cincinnati, Ohio: H. W. Derby and Company, 1848), p. 354. Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, pp. 64–65.

For more on the growth of the settlement, see Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, pp. 58, 30. Hildreth, Pioneer History, p. 224. For Putnam, see History of Washington County, p. 54. The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, edited by Archer Butler Hulbert, 2 vols. (Marietta, Ohio: Marietta Historical Commission, 1917), 1: 76–77.

Timothy Flint, Indian Wars of the West (Cincinnati, Ohio: E. H. Flint, 1833), as quoted in History of Washington County, p. 49.

Fort Harmar was established at the juncture of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers (opposite the Muskingum from the site of Marietta) in 1785, in an attempt to oust squatters from the area. Kim M. Gruenwald, “Marietta’s Example of Settlement Pattern in the Ohio Country: A Reinterpretation,” Ohio History 105 (autumn 1996): 134

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Decennial Census of Population, 1800–2000, by County, ONLINE, Ohio Department of Development, 2001, http://www.odod.state.oh.us/research/ files/p009110001.pdf (accessed April 2004).

Joseph Barker, Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, edited by George Jordan Blazier (Marietta, Ohio: Marietta College, 1958), p. 68. Guthrie went west with his brother, Stephen, also a woodworker, and his father, Joseph.

Quoted in Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), pp. xv–xvi, 384–87. Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio (Columbus, Ohio: Henry Howe and Son, 1888), pp. 779–80.

Account Book, Backus Woodbridge Collection, Ohio Historical Society (hereafter cited OHS), Columbus, Ohio.

History of Washington County, p. 376. Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, p. 58.

Kim M. Gruenwald, River of Enterprise: The Commercial Origins of Regional Identity in the Ohio Valley, 1790–1850 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), p. 43. Michael Allen, Western Rivermen, 1763–1861: Ohio and Mississippi Boatmen and the Myth of the Alligator Horse (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), p. 63.

Ohio Valley Furnishings, 1788–1830 (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Historical Society, n.d.), pp. 1–2. See also Jane Sikes Hageman, Ohio Pioneer Artists: A Pictorial Review (Cincinnati, Ohio: Privately printed, 1993), pp. 24–29.

Barker, Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, p. 25. In a search of the extant newspapers of the area, only one advertisement indicated the availability of imported furniture. The advertisement was placed by Harmar chairmaker and retailer, Augustus Stone, and appeared in the American Friend and Marietta Gazette in August 1822. He reported having recently received a shipment of Windsor chairs from Pittsburgh.

Joshua Shipman Daybook, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College, Marietta, Ohio. The disorganized nature of Shipman’s daybook makes specific page or date references difficult. All future references to Shipman’s daybook refer to the single volume owned by the Dawes Memorial Library at Marietta College.

(Marietta) Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald, February 6, 1809.

(Marietta) Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald, November 17, 1808. American Friend and Marietta Gazette, May 16, 1827. James Backus Journal, Backus Woodbridge Collection, OHS.

(Marietta) Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald, August 11, 1808. Account Book, Backus Woodbridge Collection, OHS.

Account Book, Backus Woodbridge Collection, OHS.

Probate file, William Mason, February 22, 1814, Washington County Courthouse (hereafter cited WCC), Marietta, Ohio.

Ten inventories were randomly selected from each of the following time periods: 1788–1795, 1796–1800, 1801–1805, 1806–1810, 1811–1815, 1816–1820, and 1821–1825.

Throughout his daybook, Shipman recorded prices in pounds, shillings, and pence. A few transactions in dollars and cents, including two loans in December 1797, provide a conversion rate between the two currencies: $1.00 equals six shillings. Charles Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period (1966; reprint, Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2001), p. 179.

Shipman Daybook.

Albion Morris Dyer, First Ownership of Ohio Lands (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1978), pp. 56–82. Deed Book, 1799, WCC: 193 deeds recorded, 122 sold locally, 40 to New Englanders and 31 to Virginians, New Yorkers, Marylanders, and Pennsylvanians. Wayne Jordan, “The People of Ohio’s First County,” Ohio History 49 (January 1940): 36–38. See also Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, and R. Douglass Hurt, The Ohio Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996). It should also be noted that southern Ohio, particularly the Virginia Military District just to the west of the Ohio Company lands, was flooded with Virginian settlers after 1800.

Account Book, Backus Woodbridge Collection, OHS. See also Gruenwald, River of Enterprise, p. 94.

(Marietta) American Friend, March 19, 1819.

Ray Swick, An Island Called Eden: The Story of Harman and Margaret Blennerhassett (Parkersburg, W.Va.: Blennerhassett Island Historical State Park, 2000), p. 20. The Blennerhassett Papers, edited by William H. Safford (Cincinnati, Ohio: Moore, Wilstach, Keys, and Company, 1861), p. 46.

Harman and Margaret Blennerhassett entertained frequently. By the end of 1800 Blennerhassett Island had become one of the social centers of the Ohio River Valley, on both sides of the river, and the Blennerhassetts themselves had become leading figures in Washington and Wood Counties. Because of their standing in the community, it is likely that the eastern furniture they imported, such as the Findlay chairs, had an impact on local fashions, but this impact would have only furthered the influences of the growing numbers of Southerners living in Washington County and the trade network. Harman Blennerhassett (Blennerhassett Island) to Dudley Woodbridge Jr. (Marietta), January 8, 1806, Backus Woodbridge Collection, OHS.

Inventory of Abigail Demmings, December 12, 1823, probate file, WCC. Gruenwald, River of Enterprise, pp. 103, 14.

See Baltimore Furniture (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1947), particularly nos. 41–42; Gregory R. Weidman, Furniture in Maryland, 1740–1940 (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984); and William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw, Cabinetmaker of Annapolis (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983), particularly no. 38.

History of Washington County, pp. 81, 587, 586.

Pennsylvania furniture with this type of vine-and-leaf decoration is primarily from Fayette, Washington, Westmoreland, and Greene Counties, all in the southwestern part of the state, very near the (West) Virginia and Maryland border. See Made in Western Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1982). Because of the large number of Pennsylvania settlers, as well as the close economic ties to Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and other parts of the state, Washington County furniture has similar details. Andrew Richmond, “The Fashionable Frontier: Thomas Ramsey, Windsor-Chairmaker in Marietta, Ohio,” Antiques 165, no. 5 (May 2004): 136–43. The discussion of the vine-and-leaf inlay here is only preliminary and is the focus of the author’s current research. See Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830 (New York: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Harry N. Abrams, 1997); Kentucky Furniture (Louisville, Ky.: J. B. Speed Art Museum, 1974); Fancy Forms and Flowers: A Significant Group of Kentucky Inlaid Furniture (Lexington, Ky.: Headley-Whitney Museum, 2000); Derita Coleman Williams et al., The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture and Its Makers through 1850 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society and Tennessee State Museum Foundation, 1988); Weidman, Furniture in Maryland; and Henry D. Green, Furniture of the Georgia Piedmont before 1830 (Atlanta, Ga.: High Museum of Art, 1976). The vine-and-leaf inlay motif does occur on furniture from the shop of Providence, Rhode Island, cabinetmaker Thomas Howard, but it is limited to a pair of crossed vines, most often on the skirts of diminutive sideboards. Howard’s work does not seem to be related to the meandering vine-and-leaf seen in figs. 21, 23–27. See cat. no. 48 in The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1965).

See Lee Ellen Griffith, “Line and Berry Inlaid Furniture: A Regional Craft Tradition in Pennsylvania, 1682–1790” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1988).

Joseph Buell, “Journal,” in Samuel P. Hildreth, Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley, and the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory (1848; reprint, Athens, Ohio: E. M. Morrison, 1968), p. 163.

History of Washington County, pp. 466–68.

Inventory of Joseph Buell, November 5, 1812, probate file, WCC.

History of Washington County, pp. 466–68.

(Marietta) Ohio Gazette and Virginia Herald, March 20, 1809. Register, Court of Common Pleas, 1799–1801, WCC.

Daniel Buell to Joseph Buell, January 4, 1811, Buell Family Papers, OHS.

Inventory of Joseph Buell, November 5, 1812. The Windsor chairs probably included those at Buell’s tavern, the Red House.

Ibid. Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs and American Windsor Furniture: Specialized Forms (New York: Hudson Hill Press, 1996), p. 133.

Inventory of Joseph Buell. While the crossed vine-and-leaf on the skirt resembles that used by Thomas Howard of Providence, the similarity is almost certainly coincidental, especially when taken together with the strong Southern character of the other inlaid decoration on the desk.

Information courtesy of Sumpter T. Priddy III. James Biser Whisker et al., Maryland Clockmakers (Cranbury, N.J.: Adams Brown Company, 1996), pp. 161–62, 196. The use of white pine, rather than yellow pine, along with tulip poplar as the secondary wood suggests that the inlay, but not the case, was imported from Maryland. Unfortunately, the dial and movement are missing and thus cannot provide any identifying marks. Beyond the use of indigenous woods, other evidence supports the theory Buell acquired his furniture from a local maker. There is little evidence that anyone but the exceptionally wealthy (i.e., Harman Blennerhassett) imported furniture. While Buell relied heavily on his credit locally, his lack of ready money may have made it difficult to import furniture from centers where he had few business contacts. Living and running a tavern at the Point would have put Buell in touch with people capable of importing furniture; however, it is far more likely that he purchased his furnishings from craftsmen who patronized his establishment. Among the debtors listed in Buell’s inventory were cabinetmakers Joseph Barker, Stephen Guthrie, Alexander Hill, and Joshua Shipman (Inventory of Joseph Buell). Hill, who owed Buell’s estate $74.20, advertised his use of mahogany in 1809 (Ohio Gazette, February 6, 1809). Buell clearly patronized Shipman, who sold him a dining table and two bedsteads in May 1798 (Shipman Daybook). Buell also had a close personal relationship with Shipman, as the two men planned their journey from Connecticut to Ohio together (Mary Walton Ferris, Dawes-Gates Ancestral Lines: A Memorial Volume [Milwaukee, Wis.: Privately printed, 1931], p. 740).

This technique seems to have Scottish origins, and typically, the light wood veneer is colored. Information courtesy of Sumpter T. Priddy III.

Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, pp. 67–68.

Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, p. 20. See Gruenwald, “Marietta’s Example of Settlement Pattern,” pp. 125–44; and Timothy J. Shannon, “The Ohio Company and the Meaning of Opportunity in the American West, 1786–1795,” The New England Quarterly 64, no. 3 (September 1991): 393–413. Cutler and Cutler, eds., Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, 2: 399.

Cayton and Riggs, City into Town, pp. 21, 87. Andrew Cayton’s numerous works finely detail the politics of settlement in the Ohio territory, particularly The Frontier Republic: Ideology and Politics in the Ohio Country, 1780–1825 (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1986).

Gruenwald, “Marietta’s Example of Settlement Pattern,” pp. 140–41.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, “Why We Need Things,” in History from Things: Essays on Material Culture, edited by Steven Lubar and W. David Kingery (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1993), p. 22. Philip Zea, “Rural Craftsman and Design,” in New England Furniture: The Colonial Era, edited by Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984), p. 47.

See Ann Smart Martin, “Makers, Buyers, and Users: Consumerism and a Material Culture Framework,” Winterthur Portfolio 28 (1993): 141–57; Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities; and Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Cary Carson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994).