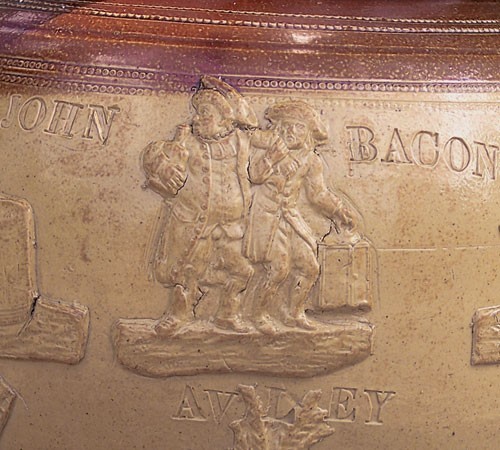

Jug, John Bacon, Bradley, Staffordshire, 1842. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. (Unless otherwise noted, all objects courtesy of the author’s collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the type-impressed “JOHN BACON” on the jug illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the inscriptions on the neck of the jug illustrated in fig. 1. Left: “Drink and Be merry / And Never be Sad / 1842.” Right: “Good luck to the Farmer /Augst 20th 18...2” [the third digit has been reinscribed, possibly a 5 overwritten by a 6].

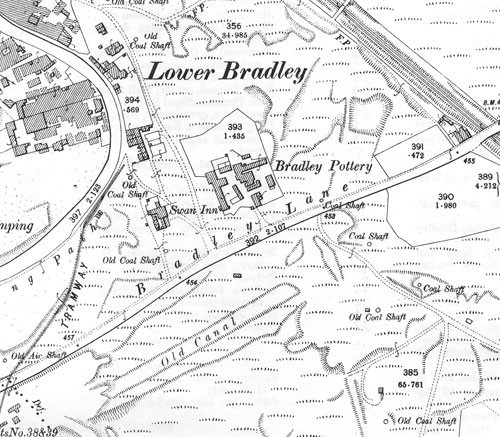

Survey map showing the Bradley Pottery in Lower Bradley. (Staffordshire Sheet 67.04, “Bradley, Coseley & Wednesbry Oak 1901,” repr. Alan Godfrey Maps, courtesy of The Trustees of the National Library of Scotland.)

Jug, ca. 1845–1850. Stoneware. H. 7". Impressed on the base of this molded brown stoneware jug with oriental motifs is “R * BREW / BILSTON.” (Courtesy, Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Museum.)

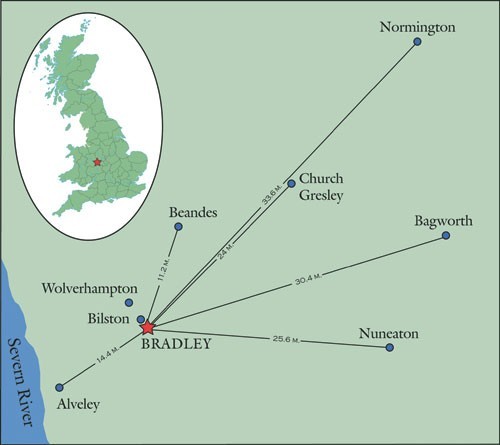

Diagram showing the relative distances between Bradley and other towns that are associated with John Bacon’s life and known products. (Diagram by Jamie May.)

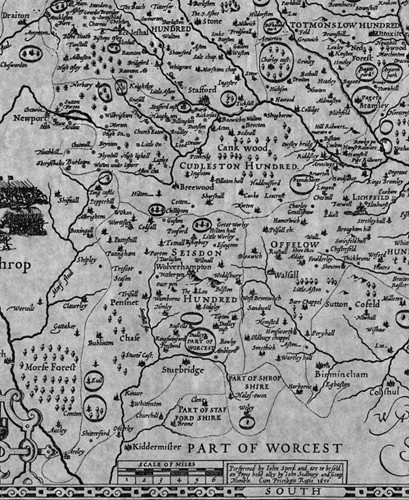

Detail from John Speed’s 1610 map of Staffordshire and the surrounding area, showing the locations of Avley (Alveley), Bilston, and Beandes (Beaudesert).

Photographs of Hall Close. Top: Ca. 1850.Bottom: 2005. (Photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

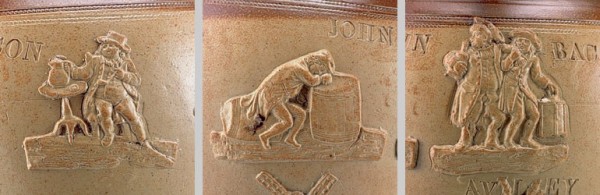

Details of sprigs on the jug illustrated in fig. 1. Left: Toby at his table. Center: Sleeping toper. Right: “The Vicar and Moses.”

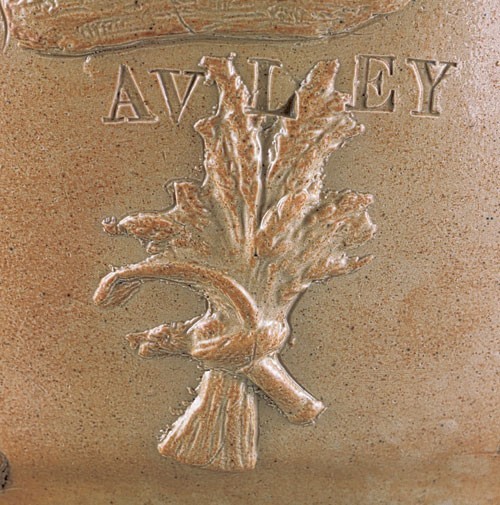

Detail of wheat sheaf and sickle sprig on the jug illustrated in fig. 1.

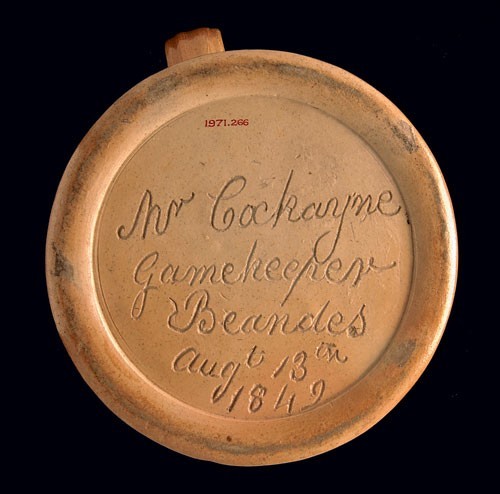

Mug, 1849. Stoneware. H. 5 3/4". This brown stoneware mug bears the inscription “Mr. Cockayne / Gamekeeper / Beandes / Augt 13th / 1849.” (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum.)

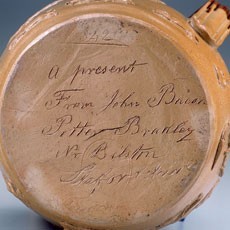

Left: Detail of the handwritten inscription on the mug illustrated in fig. 11. Right: Detail of the handwritten inscription on the jug illustrated in fig. 1: “1842 / A present / From John Bacon / Potter Bradley / Nr Bilston / Stafordordshire.”

Left: Detail of the handwritten inscription on the mug illustrated in fig. 11. Right: Detail of the handwritten inscription on the jug illustrated in fig. 1: “1842 / A present / From John Bacon / Potter Bradley / Nr Bilston / Stafordordshire.”

Engraving of Beaudesert Park, Staffordshire, nineteenth century. (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

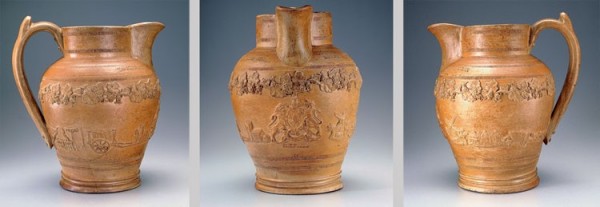

Jug, John Bacon, Bradley Pottery, Staffordshire, 1849. Brown salt-glazed stoneware H. 15 5/8". Type-impressed on one shoulder: “MRS : ROBERTS”; on the other shoulder: “BARREL INN”; on the front: “BAGWORTH / 1849.”

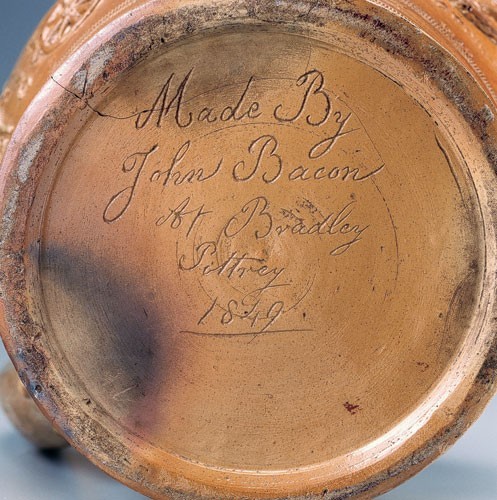

Detail of the inscription on the base of the jug illustrated in fig. 14. Incised in script: “Made By John Bacon / at Bradley Pottrey / 1849.”

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 14 showing sprig-applied farm implements—scythe, sickle, double harrow, rake, and hay fork.

Detail of sprigs on the jugs illustrated in figs. 1 (1842) and 14 (1849). Left: Church with birds on its roof from fig. 1. Right: Church similar in design but lacking birds from fig. 14.

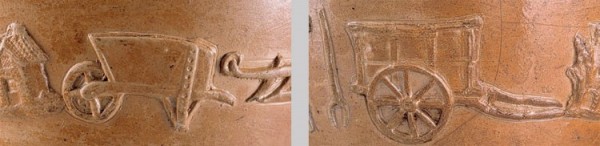

Detail of sprigs on the jugs illustrated in figs. 1 (1842) and 14 (1849). Left: Plow with broken wheel from fig. 1. Center: Spade and plow with intact wheel from fig. 11. Right: Plow and barrow details from fig. 14. (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum.)

Detail of sprigs on the jugs illustrated in figs. 1 (1842) and 14 (1849). Left: Windmill from fig. 1. Right: Windmill from fig. 14. Below: Another windmill from fig. 14 alongside a farm complex.

Detail of sprigs on the jug illustrated in fig. 14 showing a wheelbarrow (left) and a farm cart (right).

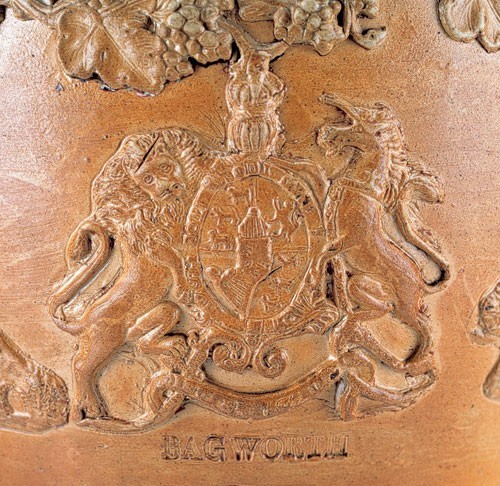

Detail of a sprig on the jug illustrated in fig. 14 showing a version of the British royal arms with a shell substituting for the cap of Hanover. Note the off-center treatment of the scroll below the garter.

Detail of the handle on the jud illustrated in fig. 14 featuring triple faux at the top and at the bottom.

Mug, possibly John Bacon, Bradley, Staffordshire, ca. 1840s. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Photo, Lance Mytton.) This updated, uninscribed mug displays sprigs paralleling those on the jugs illustrated in figs. 1 and 14.

Ceramic research is always a castle built on the sands of what we think we know, yet out there somewhere lurks the great incognitum of unrecognized ignorance. That certainly is true of my own study of nineteenth-century English brown stonewares, the vast majority of which are unmarked. We compare shapes, clays, firing techniques, and the applied sprigged decoration, and on the basis of what we consider reasonable reasoning assign this piece to Bristol and that to Derbyshire. Sometimes we go further and identify the factory itself, and assign dates within brackets, with fingers crossed in the hope that we are right. We do so in the conviction that there can be no proof that we are wrong. Then all of a sudden the sands shift and the castle leans.

In the spring of 2004 London dealer Garry Atkins acquired a massive, two-gallon jug bearing around and under itself more information than one could ever hope to find (fig. 1). On the base, in cursive lettering, is incised “1842 / A present / From John Bacon / Potter Bradley / Nr Bilston/ Stafordordshire.”[1] On the front is type-impressed “JOHN BACON/ AVLEY” (fig. 2), and in cursive script on one side of the neck appears “Drink and Be merry / And Never be Sad / 1842.” On the other, the inscription reads “Good luck to the Farmer / Augst 20th 1842”; however, the 4 is smeared and could be a 5 or even a 6 (fig. 3).[2]

Llewellynn Jewitt’s The History of Ceramic Art in Great Britain (1878), the primary source for mid-nineteenth-century factories, contains no reference to John Bacon or to the Bradley Pottery.[3] Research by Frank Sharman shows that one Robert Bew ran a pottery at Bradley between 1827 and 1851,[4] but there is no evidence that Bacon was employed by him, although there is reason to suspect that he served his apprenticeship under Bew.

By the second quarter of the nineteenth century the potteries of North Staffordshire had long since advanced from a cottage craft to a steam-mechanized industry operated by managers rather than practicing potters. Canals and railroads were making distribution infinitely easier; the packman with his horse and baskets selling wares at village and county fairs was becoming a rarity. Whether the smaller factories of South Staffordshire had advanced at a similar pace, however, is uncertain, and the products of their stoneware potters were heavier and cheaper than were the tea wares that had become the bread-and-butter of the northern factories. Consequently, in considering John Bacon of Bradley the axioms of the great Industrial Revolution might not be applicable.

In his History of Bilston, in the County of Stafford (1893), George T. Lawley mentioned a factory operated by the Myatt Pottery Co. that had moved there after being located in Bradley for half a century.[5] Wolverhampton ceramic historian Frank Sharman notes that a 1901 Ordnance Survey map of the district shows one large site to the south of Lower Bradley, identified as the Bradley Pottery, and another in the town of Bilston itself, listed as the Bilston Pottery (fig. 4). It seems likely that it was Bew who moved the business to Bilston, there being two items in the Wolverhampton Museum, one marked “R * BEW / BILSTON,”[6] and the other, “BEW POTTER / BILSTON.” Neither bears any similarity to the other, the first being a molded jug with relief decoration and the second a rather poorly proportioned Toby spirit flask. Both are likely to date to about 1845–1855; had Bew still been at Bradley when his factory made these pieces, it is unlikely that he would have attributed them to Bilston.

The Bew jug is mold-decorated with a well-executed Asiatic scene involving a camel and an elephant (fig. 5). However, the jug’s most striking feature is the size and shape of its spout, which mirrors that of John Bacon’s 1842 product.[7] Does this suggest, one might ask, that Bacon worked for Bew and took over the Bradley Pottery when the master moved to Bilston?

In 1833 Bridgen’s Directory of the Borough of Wolverhampton listed Benjamin Myatt as a “manufacturer of brown and yellow earthenware, canal side, Bradley.” By 1845, three years after John Bacon threw his Avley jug, Robert Bew is twice listed in the Post Office Directory, first as “Bew, Robert, chemist and druggist, Swan Inn,” then as “Bew, Robert, manufacturer of stone and yellow ware, Bradley Potteries.” The absence of the Myatt name in 1845 might be construed as Bew having taken over Myatt’s factory. But being primarily a chemist and druggist, it seems likely that he would have put a practicing potter in charge of his investment. If the young John Bacon had served his apprenticeship under Benjamin Myatt, it would make sense for him to continue in the factory whose operation was well known to him. Two 1851 directories (Kelly’s and Melville’s) show Robert Bew still at “Bradley Potteries” as a “stone and yellow ware” manufacturer. Frank Sharman’s thorough and invaluable research reveals that a third 1851 directory failed to mention Bew as an earthenware manufacturer but instead lists “Myatt. John, Bradley Potteries” and “Turner, Alexander (and stone), Bradley Potteries.”

What to make of all this? The answer may be that Bew had leased the Bradley Pottery from the Myatt family, which took it back when Bew gave up early in 1851. Perhaps, therefore, John Bacon was the hands-on link between the Myatt and Bew eras. The son of Derbyshire collier Daniel Bacon, he was born in 1818 at Normington (Normanton), southwest of Derby.[8] He would have been twenty-four when he made the 1842 Bacon/ Avley jug, which by any standard was a highly accomplished creation, both in its shaping and in the evenness of its firing. Had he served a seven-year apprenticeship under the Myatts, he could have been a seasoned journeyman potter by the time he was twenty, and a master potter at twenty-four. Being an employee-manager rather than an owner, however, his name might not figure in the local directories. One may argue, too, that in this role Bacon would have been prompted to indulge in a degree of self-promotion throughout a radius of, say, thirty or forty miles around Bradley (fig. 6).

On August 19, 1860, at the age of forty-two, John Bacon married Hannah Buckler, a forty-one-year-old spinster and the daughter of Thomas Buckler, a ribbon manufacturer of Nuneaton. The marriage took place at Church Gresley, approximately twenty-four miles northeast of Bilston. John Bacon was listed as a resident there, and while that could have been merely a temporary step needed for parish eligibility, it is possible that he had moved to the village after Bew relinquished his Bradley Pottery in the early 1850s. There had, in fact, been a pottery in Church Gresley as early as 1790; at the time of Bacon’s marriage it was owned by Henry Wileman, who in 1864 was said to be “getting on in years and was wishful of selling his Pottery works and retiring.”[9]

In the 1881 British census John and Hannah Bacon were living in Swan Lane, Nuneaton, a town wherein lived several ribbon-weaving Bucklers. John Bacon’s occupation was cited as “Potter (Earth Mfr),” indicating that as an earthenware manufacturer he was self-employed or a factory owner. Did he, perhaps, leave Church Gresley for Nuneaton at the time of, or soon after, his marriage?[10]

Turning again to the 1842 jug and its type-impressed inscription, it is clear that it was made for a namesake living at Avley, or so John the potter would have us believe. Chasing this place-name around England led to Avley in distant Essex, in whose church in the late sixteenth century Bacons were buried. However, that promising lead thereupon dried up, as our potter was not among them.

There is now no doubt that in writing “Avley,” John Bacon meant Alveley, a village located fourteen miles southwest of Bilston.[11] There, at Hall Close, lived one John Bacon, Esq., born in 1778 and buried in the Alveley churchyard in 1857. Local historian Margaret Sheridan has stated that “John Bacon was very rich by the standards of the time.” In the 1851 British census he is listed as being seventy-three years of age, unmarried, a “Freeholder Farmer of 147 acres, and employing 3 labs.” He was born at Stanton, Leicestershire, and employed as housekeeper his thirty-five-year-old niece Catherine Fisher and as housemaid another relative, seventeen-year-old Harriot Monks.

A surviving daguerreotype of Hall Close taken about 1850 is believed to show John Bacon beside his gate, flanked by Catherine Fisher to his right and Harriot Monks to his left. The circa 1610 house, though derelict for a time, has been restored by its present owner, James Rowley, and differs hardly at all from its appearance in John Bacon’s day (fig. 8).

That John Bacon of Hall Close was the beneficiary of potter John Bacon’s gift is further indicated by the jug’s “Good Luck to the Farmer” inscription (fig. 3), suggesting that he was himself a farmer, while the “Esq.” places him among the gentry and not necessarily any kin to John the potter. Documentary confirmation of his status comes from his will, written on April 4, 1854, which lists assets amounting to £4,000, including “the ferry, ferry boat and rights of passage over the river Severn situate at the Hall Close, Townsend, Potters Load and elsewhere. . . .”[12]

The reference to Potters Load immediately raises questions whose answers might provide the link that resulted in Bacon of Bradley making the gift jug to Bacon of Alveley. The term load is interchangeable with lode, meaning a mineral source, and one might deduce that, as Bacon’s will also cited mines and quarries, the term extended to embrace clay pits. In 1829 Simeon Shaw wrote that “clay from Shale . . . occurs abundantly in all collieries.”[13] However, it has not been established that Potters Load was a clay source. Load can also be interpreted as a landing place and might relate to Bacon’s ferry dock. If that be so, Potters Load could be a place where clays were landed or loaded from vessels plying the Severn River. That both clay and coal were being transported over considerable distances is recorded by Simeon Shaw, who told how one driver would carry baskets of finished wares astride his packhorse from Burslem to Bridgnorth, a town that straddled the navigable Severn only five miles above Alveley. Having sold his wares, the packman returned with panniers laden with balls of clay, each weighing as much as sixty pounds.[14]

Unfortunately, weaving together disparate historical strands can result in a tapestry of lies. Potters Load almost certainly defined a track leading to John Bacon’s Severn-crossing ferry from the town of Kinver 4 1/2miles to the east, at a point named Potter’s Cross.[15] As for the reading of Lode, Load, or Loade, 1 1/2 miles upriver lies the village of Hampton on the west bank with Hampton Loade opposite it on the east bank, where there is still a ferry crossing. In short, therefore, John Bacon of Alveley’s Potters Load connection to his namesake in Bradley can be dismissed as one of my more putrescent red herrings. Regardless of the true interpretation of the Potters Load location, it nonetheless seems reasonable to deduce that potter Bacon of Bradley’s gift relates to a clay-associated service provided by gentleman farmer Bacon of Hall Close, Alveley.

The jug’s sprig-applied decoration further reflects the recipient’s agricultural association. Along with three windmills, a church, and a farmhouse are a spade, a scythe, and a plow. Dogs chase a stag but without any huntsmen to urge them on. Three fairly standard figure sprigs provide the people: a Toby-like man seated at a pedestaled table, a mug in one hand and a pipe in the other; the figure I have dubbed “the sleeping toper”; and two men tottering homeward, one carrying a lantern and the other a bottle (fig. 9). This vignette is usually referred to as “The Vicar and Moses,” a design attributed to Ralph Wood, and is to be found on Staffordshire pearlware as early as circa 1790.[16] All three occur on a brown stoneware puzzle jug attributed to Derbyshire by 1825 or 1830.[17] The sleeping toper continued into the 1880s.

Front and center on the Bacon/Avely jug is a wheat sheaf bound beltlike at its midsection through which is hooked a reaper’s sickle (fig. 10). Renditions of the “farmer’s arms” are relatively common on mid-

nineteenth-century mugs and jugs, but the sickle is usually treated as a separate unit, along with scythes, sieves, and the like. Not so, however, on a three-pint mug in the Ashmolean Museum whose wheat sheaf and sickle mirror that of the Bacon/Avley jug and on the base of which, in a cursive hand, is the inscription “Mr Cockayne / Gamekeeper / Beandes / Augt 13th 1849” (fig. 11).

On the Ashmolean Museum’s “PotWeb” site the mug is attributed to Bristol,[18] and hitherto there has been no reason to question that conclusion. In 1971, however, when the mug was donated to the museum by the late antique dealer Cyril Andrade, it was accessioned as “perhaps Fulham, Mortlake or Lambeth.”[19] The ambivalence reflects the state of British stoneware knowledge at that time. The way in which the identification came about is itself a demonstration of the thinness of the ice on which ceramic historians are prone to tread. When the Ashmolean Museum put the Cockayne mug on its website as a representative example of nineteenth-century English brown stoneware, an American collector advised his contact at the Victoria and Albert Museum that the use of agricultural sprigs pointed to Bristol, not to London. In consequence, the suggestion was passed to the Ashmolean as “definitely Bristol,” whereupon the website provenance citation was changed to reflect that certainty.[20]

Evidence to the contrary has to be taken one step at a time, beginning with my sense that the lettering of the Cockayne mug was strikingly similar to John Bacon’s writing on his 1842 jug (fig. 12). Although several individual letters and groups of letters are alike (for example, the er in “Gamekeeper” and the Aug of “Augt”), it is the capital B and G that go beyond village-school copybook writing to suggest what might be termed a unity of singularity. If this is true, it follows that Mr. Cockayne lived within a radius familiar to John Bacon of Bradley—and closer to Bilston than to Bristol.

Cockayne is a name relatively well known in the vicinity of Derby and one remembers that John Bacon was born there. That, of course, is insufficient to place the gamekeeper in Derbyshire. The key, therefore, is to identify the place the potter wrote as “Beandes.” No gazetteer lists it. But fellow stoneware collector Nicholas Johnson of Boston was the first to cull one John Cockayne from an Internet chat room.[21] Cockayne was there said to have been born about 1811 and lived “in Cannock Wood as Gamekeeper by 1841.” He had three sons and a daughter, the last of them born in 1840. Cannock Wood and Cannock Chase lie only eleven miles northeast of Bradley—well within John Bacon’s product radius. But what of the elusive “Beandes”?

Cannock and the woodlands around it were part of the vast estate of the Paget family, made marquises of Anglesey after the Battle of Waterloo. William Paget, born in 1506, was elevated to the peerage in 1549 as Baron Paget de Beaudesert. Henceforth, the Paget mansion built in the late sixteenth century (and demolished 1930–1935) was named Beaudesert Hall (fig. 13). “Beaudesert” translates as “good undeveloped land,” and it stretches one’s imagination scarcely at all to read the u as an n and to drop the last three letters to arrive at Beaudes[ert], the truncation resulting either from local usage or from lack of lettering space on the bottom of the Cockayne mug. However, as Nicholas Johnson discovered, on John Speed’s 1610 map of Staffordshire, an enclosed estate southeast of Cannock (spelled Cank) was identified as Beande Sartt (see fig. 7). It therefore seems highly likely that as late as the mid-nineteenth century the Paget acreage was known colloquially as Beandes.[22]

In sum, therefore, there seems little doubt that the Ashmolean Museum’s “Bristol” mug was actually made by John Bacon in 1849. It also says a good deal about the potter himself. It was not enough to put the gamekeeper’s name on the bottom, but the wall had to depict him in the act of shooting at birds (see fig. 11). While further research may prove that the figure was a stock sprig, on the basis of available evidence Bacon may have ordered or made the mold for this specific mug. Either way, it suggests that some thought went into the selection of images. Unfortunately, or so it seemed, Bacon failed to identify either himself or where the 1849 mug was made. Had he, perhaps, left Bradley for another factory?

The answer to that key question was provided by the sudden appearance of another John Bacon jug, this time on an auction block in Boston in July 2004 (figs. 14, 15). Of four-gallon capacity and five inches taller than the already large 1842 jug, this one is marked on its bottom, “Made By John Bacon / at Bradley Pottrey / 1849.” Type-impressed on one shoulder is “MRS ROBERTS” and, on the other, “BARREL INN.” On the front are the sprig-applied British royal arms and, below, “BAGWORTH / 1849.” Bagworth lies in Leicestershire, approximately thirty miles east of Bradley. Maria Roberts is listed in the 1851 census as a sixty-year-old widow and both an innkeeper and a butcher.[23] The Bagworth date leaves no doubt that John Bacon was still at the Bradley Pottery in 1849 and continuing to produce monumental “one-off” pieces.

The type used to print “JOHN BACON” on the 1842 vessel proved to be the same Bacon would employ for “MRS. ROBERTS” and “BARREL INN” seven years later. The similarities in cursive letter formation in 1842 and that seen on the 1849 jug retain the characteristics displayed in the Cockayne mug in the latter year. Thus the capital M in “Mr.” is paralleled by that in the word “Made.” There is, however, one obvious difference: Bacon’s oversize a in 1842 had matured to A by 1849 (fig. 14).

Around the girth of the Roberts jug, beginning to the left of the handle, runs a series of agricultural sprigs: spade, plow, wheelbarrow, farmhouses, windmill, British royal arms, church, cart, hay fork, rake, double harrow, sickle, and scythe (figs. 16-21). The wheelbarrow, sickle, and scythe are paralleled on the Cockayne mug. So, too, are the wheat sheaf and sickle from the front of the 1842 jug.

Having the two signed jugs to compare one to the other and having them made seven years apart provides a hitherto rare opportunity to study how casts from a single mold can change over time. Common to both jugs is a church, which in 1842 had two small birds on its roof and in 1849 had none (fig. 17). However, the plow in 1842 has two small and previously unexplained projections at its lead end whose identity becomes apparent in 1849 as part of a small wheel that had broken in the earlier casting (fig. 18). The Cockayne mug’s plow has a similarly broken wheel, evidence of the fragility of that detail (fig. 18). Three windmills were applied to the 1842 jug, two from one mold and the third from another (fig. 19). The single windmill used in 1849 appears as a sprig from a worn mold very similar to that used for the pair in 1842 (see fig. 19).[24]

But here is a caveat: few sprigs are ever exactly alike. Even when they are from the same master mold, shrinkages occur. Distortions can result from uneven pressure in application, finger work at the edges,[25] and from post-application trimming. In all the Bacon sprigs from 1842 and 1849 the similarities are striking and clearly the work of the same matrix maker. But, like all handwork, no two are identical to the last millimeter. (fig. 20)

The 1849 harrow is made from two square and abutting sprigs, one of which was used for the Cockayne mug (see figs. 16 and 18 right). The jug’s frontal coat of arms (fig. 21) has attributional problems, being a correct rendering of neither the Hanoverian arms of the kings George and William nor that of Victoria, who had been on the throne for twelve years when Bacon made his 1849 jug.

George IV and William IV were both kings of England and electors of Hanover. Consequently, their arms included in their center a shield containing those of Hanover topped with its electoral bonnet. After the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, Hanover became a kingdom separate from the old Holy Roman Empire, whereupon the bonnet was replaced by a crown. When, in 1837, William IV died and his niece Victoria became queen of Great Britain, it was determined that, being a woman, she could not also be ruler of Hanover. Consequently, the Hanoverian shield was removed from the British royal arms.

On the Bacon version the central shield survives but is topped by what appears to be a tassel, or perhaps a shell. Visible around the lion and unicorn supporters is evidence of knife trimming to remove excess clay, a process which in this instance cropped off most of the lion’s crown. This error applied to that specific casting, but there are other permanent peculiarities, notably the off-center scrolling below the Order of the Garter and a frondlike element to the left of the unicorn’s chain, here shown looking more like a rope. These details are important because the royal arms were widely used to decorate cylindrical stoneware jars and cisterns and may serve to identify unmarked products of the Bradley Pottery.

On the 1849 jug shallow rouletting created cordons at both the shoulder and above the slightly elevated base, but much more prominent is a skillfully applied garland of grapes and vine leaves at the shoulder. Applied in high relief, the foliate decoration dominates the wall, and this, too, may serve as a clue to identify other Bacon products.

There remains one more distinctive feature, namely the three faux screws “anchoring” the handle at top and tail (fig. 22). The application of this device, its screws usually in pairs and securing a lateral strip, became commonplace by about 1820 and first occurred (so I believe) on a Nelson commemorative jug I have attributed to Fulham, circa 1805.[26] Fulham later went to three screws, but only at the lower terminal, and to my knowledge no London-area factories applied triple screws within the handle’s upper attachment. However, two screws both below and above occur on some mugs attributed to Derbyshire.[27] The 1849 Cockayne mug has its lower handle terminal secured by a strap and two screws in the manner popular in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, particularly in Derbyshire.

With two jugs and a mug now safely attributed to John Bacon at the Bradley Pottery between 1842 and 1849, one immediately asks: Where are all the rest of his unmarked wares produced there in that seven-year span? That they do exist was demonstrated in December 2004, when Sussex collector Tom Poucher found another in a local auction (fig. 23).[28] Though unmarked, its harvest-related sprigs include a harrow, plow and rake, and the wheelbarrow from the same mold as that used on both the 1849 Bagworth jug and the 1849 Cockayne mug (see fig. 20). The wheat-sheaf and sickle sprig is different, and so may be the church. Unique to the Poucher mug, however, is the central water-driven mill with its adjacent garden kiosk, representing sprig design at its best, as does the fenced haystack (fig. 23, left).[29] That the strapped foliate handle terminal is different from that of the Cockayne mug is clear evidence that John Bacon’s Bradley Pottery was supplied with a wide range of high-quality sprigs, which makes it unwise to accept any one of them as the identifier of a Bacon product. Both the grandeur of the dated jugs and the quality of the Cockayne mug and now the Poucher mug, however, strongly suggest that John Bacon’s run-of-the-kiln output was the equal of anything then being made by competitors at Mortlake, Lambeth, Fulham, Bristol, or Derbyshire, and his best ennobles him as a prince among stoneware potters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to my friend and sounding board Nicholas Johnson in Boston, as well as to Curator Timothy Wilson at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Frank Sharman of Wolverhampton; Alveley historian Margaret Sheridan; and Robert Hunter, editor of Ceramics in America. I am further indebted to James Rowley, owner of Hall Close Farm, for his hospitality and for sharing with me the contents of the John Bacon papers. My thanks also go to London stoneware collector Philip Mernick and to Lance Mytton, editor of ABC Antique Bottle Collector UK. I am grateful to Jamie May, who so kindly created the diagram for figure 6. Last, but by no means least, my appreciation to London dealer Garry Atkins, who led me to both Bacon jugs

Unaware that the 1842 jug would later be dwarfed by another, I felt comfortable in referring to it as massive. Indeed, a two-gallon pitcher is undeniably larger than most beer jugs. A long ode entitled “The Praise of Yorkshire Ale,” probably from the late eighteenth century, contains the following lines: “This moved Bacchus presently to call / For a great Jug which held above five Quarts, / And fillng ’t to the Brim. . . .” Quoted in André Louis Simon, Drink (London: Burke Publishing Co., 1948), p. 165.

All references to the jug’s front or back refer to left or right of the held handle—remembering always, of course, that no antique ceramic vessel should ever be held by its handle!

Llewellynn Jewitt, The History of Ceramic Art in Great Britain: From Pre-Historic Times down through Each Successive Period to the Present Day..., 2 vols. (New York: Scribner, Welford, and Armstrong, 1878).

Frank Sharman, “Bilston and Bradley Potteries,” available at www.localhistory.scit.wlv. ac.uk/ BCMC/pottery/pottery01.htm (accessed July 12, 2005).

Research by the Wolverhampton Museum’s Francesca Cambridge suggests that there was a glass factory at Bradley in the late seventeenth century. As such an operation would have required siege pots (crucibles), it is reasonable to deduce that the ceramic side of the glasshouse would provide the continuum to locate a ceramic manufactory there in the eighteenth century. There is some evidence that in the 1760s the area became known as Glassborough. An advertisement published in the Birmingham Gazette, April 12, 1762, showed that on April 12 the glasshouse was to be sold, its assets then including “about 100 pots.”

This jug is illustrated in Adrian Oswald, R. J. C. Hildyard, and R. G. Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, 1670–1900 (London: Faber and Faber, 1982), pp. 196–99. Also pictured is an unmarked brown stoneware money box “reputedly made in Bilston.”

These separately attached spouts are sometimes referred to as “snips,” the V to insert them having been snipped out of the mouth when the clay was still in the plastic state. The specialists who applied handles and spouts were known as stoukers. See John Thomas, The Rise of the Staffordshire Potteries (Bath, Eng.: Adams and Dart, 1971), p. 6.

U.K. Public Record Office Ref.: RG11, Piece/Folio 3060.81, p. 35.

Kenneth Stanley Green, “The History of T. G. Green Pottery, 1790–2000,” available online at www.zyworld.com/tggreen/Pottery%20History.htm (accessed August 12, 2005). Church Gresley marriage records show that there were twenty potters in the parish in 1841–1845, seven in 1860, and ten in 1861–65, many of them following in their fathers’ craft. Overall these numbers suggest a declining business at Henry Wileman’s factory toward the end of his ownership.

There being no references to Robert Bew as a Bradley pottery owner after 1851, it is possible that John Bacon left at the same time. On the other hand, if he had previously worked for the Myatts, John Myatt’s return could have been reason enough to stay on, at least through the transition.

The village is spelled “Aueley” on John Speed’s 1610 maps of Shropshire and Staffordshire, but elsewhere on the maps he used u and v interchangeably.

Townsend Farm stands adjacent to Hall Close Farm and has extensive quarries, or borrow pits, immediately to the east of it. The will was transcribed by Margaret Sheridan in September 2004.

Simeon Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries (1829; facsimile repr. Newton Abbott, Devonshire, Eng.: David and Charles, 1970), p. 99.

Ibid., p. 149. Bridgnorth was described as “a place of great trade both by land and water” and included three barge owners among its tradesmen; Universal British Directory of Trade Commerce, and Manufacture, 5 vols. (London, 1791–1798), vol. 5, appendix, pp. 30–33. Clays from the Shropshire Valley of the Severn had been centers of potting since the Roman era, and in 1790 china repairer John Lawrence was to be found at “the China Works near Bridgnorth.” Jewitt, History of Ceramic Art in Great Britain, vol. 2, p. 111.

A farm of the same name lies a short distance to the west, along what is presumed to have been the Potters Load road.

John Lewis and Griselda Lewis, Pratt Ware: English and Scottish Relief Decorated and Underglaze Coloured Earthenware, 1780–1840, rev. ed. (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club in association with Leo Kaplan Ltd., 1994), p. 193.

See Ivor Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go! From Vauxhall to Lambeth, 1700–1956,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), p. 203, figs. 12b, c, g. So alike are they that it is reasonable to deduce that all six sprigs are derived from the work of a single master matrix maker.

For additional information, including images, go to http://potweb.ashmol.ox.ac.uk/PotChron7-56.html (accessed July 12, 2005).

Ashmolean Museum, acc. no. 1971-203. I am indebted to Timothy Wilson of the Ashmolean Museum for this catalog information.

The basis for the Bristol identification rested on the evidence of two jugs, illustrated in Robin Hildyard’s Browne Muggs: English Brown Stoneware (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985), p. 80, nos. 204, 205, whose sprigs include the Bacon wheat sheaf, spade, plow, and harrow. The author identifies both as being from Bristol, ca. 1800, but offers no documentary evidence for either assertion. The illustrations are too poor to be sure that the tools are from Bradley molds, and the shapes (one pinched spouted and the other a puzzle jug) are unrelated to the few known Bradley forms. Although the master sprig molds could have been made and used at Bristol long before gravitating to Bradley, I am reluctant to preclude the possibility that both jugs are John Bacon products. Unfortunately, their whereabouts are unknown.

Personal communication, September 25, 2004.

As Frank Sharman has commented, “in 1840 the spelling of place names was not all that settled. What is now thought of as the correct spelling was often something which was gradually determined by the Ordnance Survey or the Post Office. And pronunciation is sometimes surprising: Bradley is pronounced Braydley!” Personal communication, July 19, 2004.

Trade directories in 1846 and 1849 list Maria Roberts as a butcher and victualler at the “Barrel Inn,” Bagworth. The 1851 census cites her as household head, aged sixty-two, and an innkeeper born in Bagworth. Her daughter, Maria, was unmarried, aged twenty-four, and also born in Bagworth. Her son, John Roberts, aged twenty-one, was listed as a butcher and presumably ran that side of the business. Also resident at the inn were two agricultural laborers and a visiting farmer’s son. This information was kindly supplied by Leicester Archives Assistant Lois Edwards.

The windmill on the Cockayne mug is entirely different, having away-facing sails and a tiered structure akin to another I have attributed, perhaps unwisely, to Mortlake or Lambeth. See Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go!” p. 234, fig. xii.8.

Thumb smearing can be seen at the left rim of the barrel in fig. 9, center.

Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go!” p. 207, fig. 15a, and p. 237, table xv.1. Jack Howarth and Robin Hildyard included a photograph of this jug in their recently published book Joseph Kishere and the Mortlake Potteries (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2004), p. 43, pl. 31. They have identified it as “Probably Mortlake,” although offer no support for their reasoning.

Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go!” p. 237, table xv.

“Around the Shows,” ABC, Antique Bottle Collector, UK 23 (2005): 36, ill.

This sprig was used by several factories.