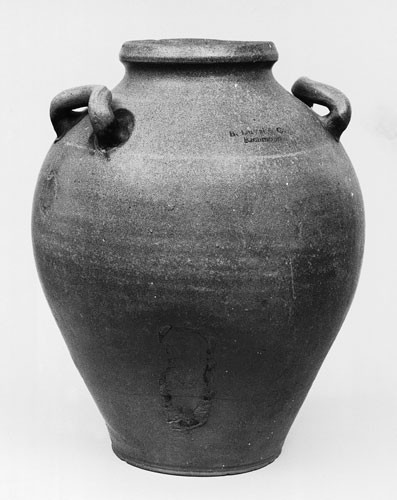

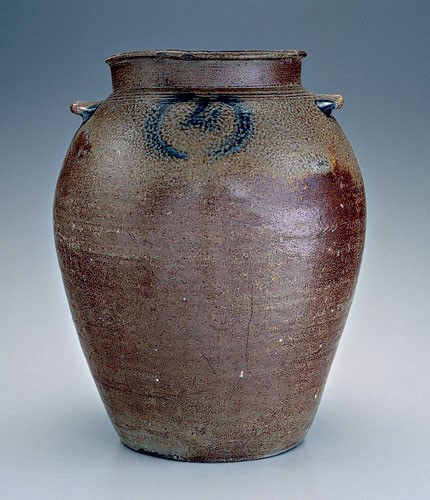

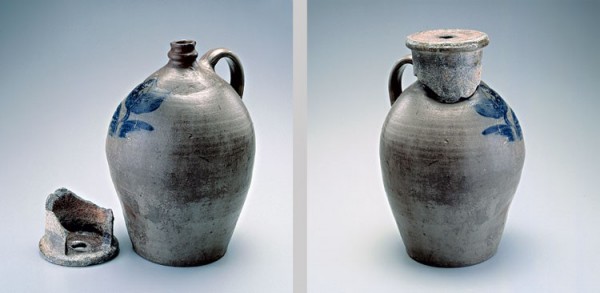

Storage jar, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This three-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “B. DuVal & Co./ Richmond.”

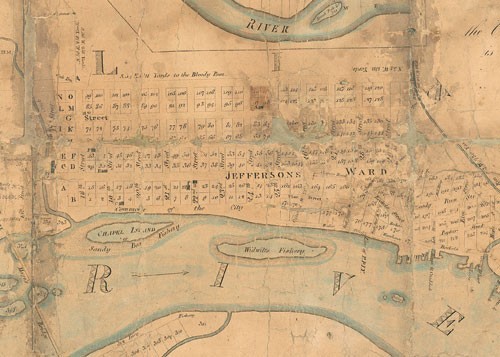

A Plan of the City of Richmond, Richard Young, 1809–1810. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.)

Detail of the Richard Young map showing lots 39, 40, 53, and 54. The approximate location of the DuVal kiln, based on recent research, is shown.

Fragments of DuVal stoneware that littered the construction site. (Photo, David Hazzard.)

Construction machinery on the site of the Benjamin DuVal Pottery. (Photo, David Hazzard.) Archaeologists had to retrieve artifacts while this machinery was in motion. The empty hole in front of the excavator is where the kiln foundation and a massive waster pit were uncovered.

Brickwork from the foundation of the DuVal kiln. (Photo, David Hazzard.) The majority of the rectangular kiln foundation appeared to be intact when first uncovered. Unfortunately, it was removed by grading machinery one afternoon, before any archaeological recording could begin. Other portions of the kiln were later found at the construction debris landfill.

Volunteers collecting sherds from a recently excavated part of the site. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Boxes of collected stoneware fragments and kiln furniture. (Photo, David Hazzard.) Far from an ideal archaeological recovery, this rescue eVort nevertheless resulted in the salvage of approximately forty boxes of artifacts.

John Kille and Marshall Goodman arriving at one of the construction landfills to see where the debris from the Benjamin DuVal Pottery site was being dumped. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

David Hazzard, Marshall Goodman, and John Kille examine one of the hundreds of fragments recovered from the dump site. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Archaeologist David Hazzard investigates a pile of clay roofing tiles. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments are undoubtedly associated with DuVal’s Richmond Tile Manufactory, which opened in 1807. No other information was recovered that shed additional light about that operation.

Jar or jug base fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (All artifacts courtesy Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment displays the characteristic wire marks that result when a wet vessel is cut from the wheel.

Jar and jug base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These bases show different methods of cutting wet pots from the wheel. The techniques may have varied among the individual potters.

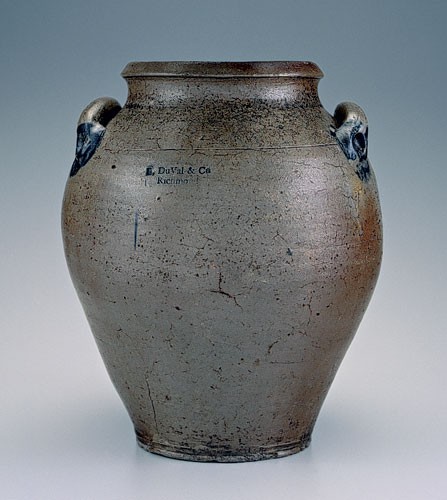

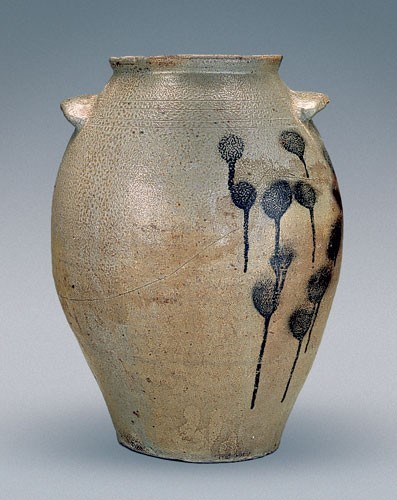

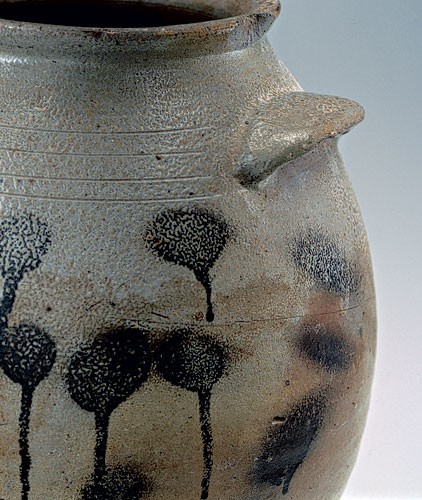

Storage jar, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This three-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond.”

Detail of the maker’s mark on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14.

Jar strap-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These were probably from two-gallon jars.

Jar strap-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This handle was part of a very large jar, possibly five gallons in size.

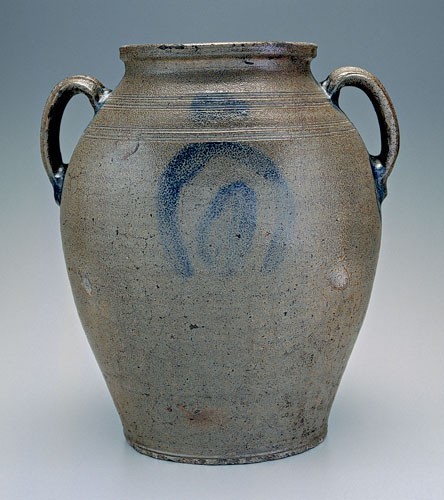

Storage jar, attributed to Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the vertically placed strap handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 19.

Jar lug-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 22.

Storage jar, attributed to Loudoun County, Virginia, ca. 1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the handle on the jar illustrated in fig. 24.

Jar rim fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These wide-mouthed, cylindrical jars are similar in shape to the one-gallon jar illustrated on the left in fig. 27 (note the brown iron oxide wash on that example).

Storage jars, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 12". (Private collection.) Right: H. 12". (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society; photo, Ron Jennings.)

Jar fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) These small jar fragments probably represent the 1/8-gallon (one pint) jars advertised by DuVal, which undoubtedly he used in his apothecary business.

Jug neck and mouth fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Dozens of these jug fragments were collected. The vast majority have similar reeding of the neck and placement of the handle terminals.

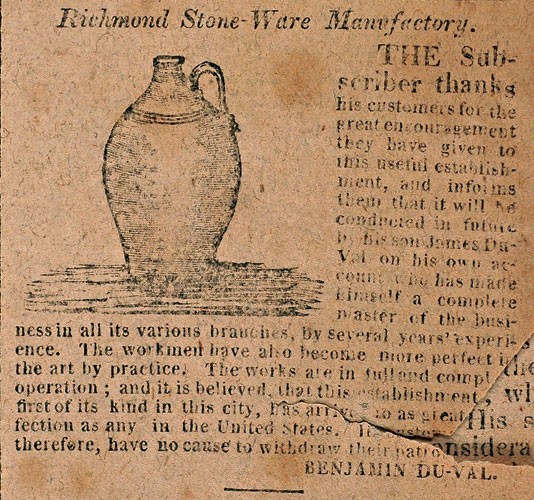

Detail of a newspaper advertisement for the “Richmond Stone-Ware Manufactory,” published in the Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.)

Jug, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the straight attachment of the handle to the shoulder in the detail above.

Jug, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the straight attachment of the handle to the shoulder in the detail above.

Jug fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments represent typical jug necks.

Jug fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This large fragment belongs to a four- or five-gallon jug. Note the handle attachment on the shoulder of the pot, well below the neck.

Jug or jar base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These base fragments provide evidence of the graduated vessel sizes produced at the pottery. The range of colors on these fragments illustrate the variations possible in the firing process.

Pitcher fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Fragments of pitcher collars showing the profile of the pinched spouts. The small pitcher fragment on the right shows the upper handle attachment.

Bottle neck fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments are typical bottle neck profiles recovered from the pottery site.

Bottle neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This bottle neck shows the unusual addition of cobalt highlights.

Bottle fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This bottle fragment with the impressed “R. Adams.” may have been custom-produced for Richard Adams, one of Richmond’s wealthiest citizens and a leading real estate developer. Adams’s home was located just a few blocks north of the DuVal kiln site.

Flasks or tickler fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) DuVal’s advertisements list small pocket or “tickler” flasks. Fragments of numerous oval-shaped flasks were recovered at the pottery site. The body fragment on the left is unusual, as it has been flattened on both sides, possibly to fit into a wooden case.

Chamber pot fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These handled chamber pots are similar in shape to others that were being produced in Alexandria and Baltimore in the early nineteenth century. Note the dimple beneath the lower handle attachment on the body fragment on the right.

Jar or churn neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Unusual throwing rings remain on the exterior of this large jar neck. A shelf or flange inside the lip suggests that a lid was associated with this vessel, possibly making it one of the churns listed in DuVal’s advertisements.

Milk pan or shallow bowl fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This unusual bowl-like fragment may represent one of the milk pan forms listed in DuVal’s advertisements.

Jug stackers, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jug stackers were one of most common forms found during the salvage recovery. Note the graduation of sizes to accommodate the wide variety of jug capacities produced at DuVal’s pottery. The cutouts are for jug handles.

Jug and stacker collar, John P. Schermerhorn, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although it was not produced at the DuVal pottery, this Richmond-made jug illustrates the placement of the stacker collar over the mouth and neck of the jug. The stacker is designed to provide a level surface on which to place another jug. The hole in the stacker allows the gases to escape from the jug’s interior. Note the indentations on the jug’s shoulder where the stacker made contact.

Jug neck fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These large jug necks show the differential coloration resulting from uneven distribution of the airborne salt gases due to the placement of the stacking collars. The jug on the left collapsed from the weight and extreme heat during firing.

Kiln furniture, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) A variety of kiln furniture was employed in the stacking and firing of DuVal’s kiln. The specially prepared circular and angular pads on the right served to separate vessels, whereas the clay strips and globs offered an expedient way to level pots and seal gaps in the kiln.

Fused jar fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These jar fragments, which partially melted during a firing, provide direct evidence of the stacking methods used in the kiln. Note the fire-clay spacers used between the jar mouths. Jars were stacked base to base and mouth to mouth.

Jar base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the fused spacers adhering to the bottoms of these over-fired jar bases.

Jar and jug fragments with impressed marks, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Out of the thousands of fragments collected during the DuVal salvage recovery, fewer than a dozen had impressed marks. The historical documentation suggests that the “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond” mark was used from 1811 until 1817, when Benjamin DuVal’s son James took over the operation of the pottery.

Jar or jug fragments with impressed marks, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1818. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These marks may have been used by James DuVal when he took over his father’s stoneware manufactory in 1817. The full impressed mark might have read “duval stoneware manufactory/ richmond va.,” but no intact vessel with this mark has been found.

Jar or jug fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These incised fragments were the most enigmatic artifacts found during the DuVal salvage recovery. They suggest very high quality incised decoration previously unassociated with the DuVal operation or, for that matter, any Richmond-area stoneware.

Jar fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment, which is from a large four- or five-gallon jar, has a wavy incised line on what would have been the shoulder.

Incised body fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) While seemingly rudimentary, this incised sherd may be part of a larger design.

Jug neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This simple incised leaf filled with cobalt must have been produced in some quantity, though no extant examples have been identified.

Jar fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment is from the shoulder of a large, probably five-gallon, storage jar. The five cobalt "fingerprints" might signify the jar's capacity.

Pitcher handle fragment, Benjamin Duval Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware, (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This delicate strap handle probably belonged to a quart-sized pitcher. Note the "fingerprint" decoration on the handle.

Jar Fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The site of the Benjamin DuVal Stoneware Manufactory in Richmond, Virginia, was first identified in 1978 through historical research conducted by Brad Rauschenberg.[1] Rauschenberg initiated his research when the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), with which he was associated, acquired a large salt-glazed stoneware jar marked “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond” (fig. 1).[2] Preliminary archaeological investigation directed by Dr. Norman Barka of the College of William and Mary subsequently confirmed the identity of this important historical site’s physical remains.

Benjamin DuVal Jr. was a Richmond pharmacist and entrepreneur who in 1791 posted a help-wanted ad for a potter “who understands working at the wheel” to supply wares for his business.[3] Nothing else is recorded about DuVal’s clay working enterprises until 1808, when he began manufacturing clay roofing tiles.[4] In 1811 he announced the production of salt-glazed stoneware.[5]

The DuVal pottery plays a significant role in the story of American ceramics. The pottery was not only Richmond’s first stoneware manufactory, but also one of the earliest salt-glazed stoneware operations in the South.[6] The surviving historical documentation, which includes detailed price lists and descriptions of the available forms, offers a ready and rich source of information for research. And while very few marked examples of DuVal’s stoneware have been recorded, the fragments from the site illustrate the remarkable variety of forms and decorative treatments employed by DuVal’s workforce. Such primary evidence is crucial for ceramic historians and collectors, who otherwise would be limited to surviving marked examples and those attributable through connoisseurship.

The study of the DuVal pottery also permits insights into the developing mercantile economy of early-nineteenth-century Richmond and the surrounding region. Growing Virginia businesses, including pharmacies, distilleries, dairies, and other commercial operations, created a demand that encouraged pottery manufacture. DuVal’s early advertisement for potters may have served as the catalyst for what was to become a burgeoning Richmond stoneware trade. By the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century, more than a half-dozen stoneware potters were working in the area.[7] Local production of wares equal or superior to those previously imported from England, Germany, or the New York–New Jersey region allowed Virginia’s potters to successfully expand their enterprises by offering competitive pricing and to eventually dominate the market. Based on his early association with John P. Schermerhorn, a New York potter who relocated to Richmond to ply his craft, DuVal appears to have hired workers trained in the New York–New Jersey stoneware tradition. As a result, the DuVal stonewares are similar in style to those of the New York area.

At the time of its 1978 discovery the DuVal pottery site was situated in a partially vacant lot in Richmond’s downtown warehouse district on East Main Street (figs. 2, 3). Over the years local archaeologists had sampled the site, but no full-scale excavation had been attempted. Registered on the Virginia state inventory system, the pottery had remained undisturbed in this historic, but neglected, part of Richmond for over two decades—that is, until the commercial development of the property in early 2002.[8]

Salvage Recovery

I [Hunter] made a habit of driving by the DuVal site whenever I traveled to Richmond, to see whether urban renewal threatened the property. For the most part I trusted the historical preservation protections offered by both federal and state mandates to keep the site safe. However, on a cold Sunday in February 2002 my worst fears were realized. Instead of seeing the familiar large vacant warehouses, yellow grading machinery was parked on the rubble-strewn lot. Initially, I double checked my bearing to make sure I was in the right place. Sadly, I was. Construction was underway for a new neighborhood grocery center intended to serve the residents of nearby historic Church Hill and the growing community living in converted warehouse condos and apartments.

In the center of the property, partially enclosed by a chain-link fence, I could already discern mounds of pottery sherds and brickbats. Worse, several of Richmond’s weekend “archaeologists”—artifact collectors who routinely scavenge the areas’s unprotected sites for bottles and related Civil War artifacts—were on the scene.[9] Despite a high fever brought on by the flu, I joined them and began picking out jug handles, jar bottoms, and assorted kiln furniture from the debris (fig. 4). Fortunately, potter Michelle Erickson had accompanied me and joined in the rescue.

Within minutes I developed another type of fever. Standing amid the mounds of stoneware fragments I spotted a fragment bearing the stamp “B. DuVal &Co./Richmond, Va.” Quickly hiding it in my pocket to avoid attracting further attention, my feelings oscillated between excitement and dismay. I gathered several discarded cardboard boxes and filled them with as many fragments as space permitted. Given my physical condition and the bitterly cold weather, I had to leave the piles of fragments to the other souvenir hunters. It was very difficult to do so, and even harder to accept the failure of the historical preservation community to prevent such unnecessary destruction.

I vented these feelings on HISTARCH, an internet-based posting service used by the archaeological community. I also called David Hazzard, director of the Threatened Sites Program for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, to plead the case for the site. David responded immediately and initiated an investigation into why the site had not been flagged prior to construction, and, more importantly, into the possibility of salvage. Construction could not be halted at this late date, but he convinced the construction foreman to permit access provided participants followed certain safety precautions, such as wearing hard hats.

Meanwhile, my HISTARCH posting caught the eye of Eric Powell, the online editor of Archeology magazine, who ran a story on the site’s destruction.[10] The local Richmond newspaper also ran stories, which led to contact with the DuVal Family Association, Inc., the membership of which includes hundreds of descendants.[11]

While the media did its work, members of the community did theirs. A number of volunteers from the archaeological world, stoneware buVs, neighbors, and friends pitched in for several days during the salvage operation.[12] In particular, long-time Richmond antique dealer Marshall Goodman took an active role in the recovery and initial study of the fragments. Marshall also spent time tracking down extant examples of DuVal stoneware and related material. As well, John Kille, author of “Distinguishing Marks and Flowering Designs: Baltimore’s Utilitarian Stoneware Industry” in this volume of Ceramics in America, drove down from Annapolis and spent several days collecting and washing artifacts.

During the field work, while dodging heavy excavating machinery, the volunteer crew retrieved thousands of sherds (fig. 5). Unfortunately, in the few days it took to organize the effort, the remains of the pottery kiln—along with a huge waster pit—were carted off to the local landfill (fig. 6). Undeterred, the volunteers followed the dump trucks and picked through the spoil (figs. 7-10). They recovered what they could, including several portions of the kiln (fig. 11).

History and Background

Prior to Brad Rauschenberg’s investigation, little was known about the DuVal pottery or its products. Rauschenberg’s research quickly revealed, however, that the DuVal documentation is among the best available for any early American pottery.[13] The chronological history of the pottery is summarized in Table 1.

A series of DuVal’s newspaper advertisements illustrate the range of vessel forms produced at his factory. They also give vessel sizes and provide prices for the goods listed in Table 2.

The Collection

The weeklong flurry of activity resulted in the collection of approximately 2,000 pounds of material. Once again, a number of volunteers, over the course of several months, accomplished the first daunting task at hand: washing and sorting sherds by the bucketful.[14] Once the initial sorting was complete, the most obvious diagnostic fragments—rims, handles, marks, and unusual vessel forms—were separated out. While the archaeological value of the site had been compromised, the salvaged collection provides an amazing record of DuVal’s stoneware products and manufacturing process.

Some care, however, is necessary when evaluating the material. Firing stoneware is a difficult and risky endeavor, and “wasters” are a natural part of the process. Success rates for an individual kiln load can vary greatly. As reported in his December 16, 1815, ad, DuVal’s kiln(s) had failed on at least one occasion:

THE RICHMOND STONEWARE MANUFACTORY is now in full operation. The works, (which have been much impeded some time past, by the failure of one of the kilns,) are in complete repair, and will turn out Ware in future to the amount of one thousand dollars per month, at the least.[15]

It should be remembered that the collected sherds represent the unsuccessful production of pottery, pots that failed at some point during the production and firing process and were summarily discarded. Accordingly, the retrieved sample might not be representative of the full range of pots that actually entered the marketplace. In spite of this limitation, the collection is invaluable as hands-on evidence, providing parallels to help identify unmarked antique specimens.

Analysis of the material also demonstrates the need for caution when interpreting individual traits. For example, many collectors might view the finish of a pot’s base as characteristic of a particular factory or potter. Although the entire composition of DuVal’s workforce is not known, there were a number of workers involved. His inventory suggests that a number of slaves might have been employed in the operation. The production in any large-scale factory is no different than the modern assembly line, where individuals traditionally have specific tasks such as throwing, handle making and attaching, decorating, and loading and firing the kiln. An examination of DuVal stoneware base fragments shows a great deal of variation in how the pots were removed or cut from the throwing wheel (figs. 12, 13). Even though they were unmistakably made at DuVal’s, outside the context of the site one might ascribe different origins to these pots.

The biggest limitation of the project was the destruction of discrete archaeological deposits that would have provided many more answers to questions about the DuVal site. The controlled excavation of such deposits often helps distinguish earlier artifacts from later ones. In addition, excavation of the stratigraphic layers could have revealed specific episodes of firings and discarding. Since the recovery was basically at the mercy of construction machinery, these important controls were lost forever.

Initial Analysis of DuVal Stoneware

The following discussion speaks to the preliminary study of the recovered fragments. However, a thorough understanding of the material will require more analysis. It is hoped that some eager graduate student will eventually rediscover the DuVal artifacts in their new repository at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in Richmond.[16]

Storage Jars (Pots)

Based on the number of these pots listed in his advertisements as well as the quantity of recovered fragments, the most common vessel form produced at the DuVal pottery was the storage jar, although the ads indicate DuVal used the term “pot” instead of “jar.” By whatever name, the ads also note that he made them in graduated capacities, from one to five gallons.

The best evidence for the overall shape and finish of this vessel form comes from known antique examples (figs. 14-16), although only a handful of marked or attributable examples survive. The archaeological material provides additional evidence concerning the variation of shapes and sizes, including a wealth of information about such specific attributes as handles, rim types, and decorative attributes.

Several types of handles were used on DuVal jar forms, the most distinctive of which is a rolled, or extruded, strap handle horizontally placed above the shoulder with well-formed dimples at the terminals (fig. 17). Displaying a decorative touch, these dimples, many brushed with cobalt, occur from thumb or finger pressure applied to the wet clay handles when attached to the body. Most of the strap handles close on the shoulder, although several open examples are known, including the example in the MESDA collection (see fig. 1). One unusual open handle was recovered, which appears to be associated with a very large storage jar, perhaps the five-gallon size (fig. 18).

A different type of strap handle is found on the large storage jar illustrated in figure 19. Although unmarked, this large jar is attributed to the DuVal pottery based on several characteristics, including the well-formed rim and cordations on the shoulder. These vertically placed strap handles have a finger-impressed dimple at the lower terminal highlighted with cobalt (fig. 20). Acquired in the 1980s, the antique jar turned up in a home only a few blocks from the DuVal pottery site.

In contrast to the open strap handles, a number of flat lug, or eared handles, were also recovered (fig. 21). This type of handle, rectangular in plan and cross-section, attaches high on the shoulder close to the rim. Many of the handles are accented with cobalt slip. Only one antique example has been identified that might be attributed to the DuVal pottery (figs. 22, 23). Handles of this general type are common on stoneware from Alexandria, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland (figs. 24, 25), but previously have not been associated with Richmond-area stoneware of this period.

Careful excavation might have identified a functional or chronological distinction between the strap and lug handle types, or determined instead that they simply represent the working styles of different potters. Since this was not possible, further clarification awaits the discovery of more documented DuVal jars.

A number of smaller jars were found that correspond to DuVal’s advertisements, among them a cylindrical one-gallon jar without handles and a handled ovoid form (figs. 26, 27). In addition, fragments from smaller cylindrical jars advertised as "1/8 gallon” (or one pint) were recovered (fig. 28).

Jugs

Based on the tremendous quantity of jug fragments recovered, we know that this form figured prominently in Benjamin DuVal’s business (fig. 29). He apparently was proud of his jug and incorporated it into his trade sign. Generally ovoid and graceful, the jug form corresponds to one illustrated in DuVal’s 1817 newspaper advertisement (fig. 30).[17] It also conforms to the style in vogue with other nineteenth-century American stoneware potters. Remarkably, only one antique example of this form by DuVal is known (fig. 31).

Within the large archaeological sample, there was apparent consistency in the form and finish of the jug necks. Reeded necks mimicked a threaded fitting and featured a sharply beveled finished lip. As with all stoneware jugs, a cork or wooden plug held in place with a wire or string tied around the neck would have sealed the jug.

The upper handle typically terminated at or near the lip (fig. 32). On larger jugs, the upper handle terminal was located farther down, at the juncture between the neck and body (fig. 33). There were few examples of lower handle terminals; most handles appear to attach directly to the shoulder without the characteristic dimple seen on the jar handles. Many examples had brushed or daubed cobalt highlights at the terminals. A variety of sizes, corresponding to the range indicated in DuVal’s advertisements, was noted (fig. 34).

Pitchers

According to his newspaper advertisements, DuVal made pitchers in at least five sizes: one quart, one-half gallon, one gallon, two gallon, and three gallon, a range that corresponds with other manufacturers of the period. Regrettably, only a handful of fragments were found to help understand this finished DuVal product (fig. 35).

The fragments indicate the pitchers had a broad collar accented with incised lines. Shapes were probably similar to the ovoid lines of DuVal’s jugs, which displayed a well-formed shoulder. A simple pinched spout was expediently formed while the pitcher was in its wet state. Handles were pulled and attached directly to the lip or collar. No information about the lower handle terminal has yet been identified.

Bottles

Quart- and pint-sized stoneware is listed in DuVal’s newspaper advertisements. Bottle neck fragments were fairly common among the recovered sherds, demonstrating that these were an important production item and possibly associated with DuVal’s apothecary practice (figs. 36-38).

“Ticklers” or Pocket Flasks

DuVal’s advertisements listed pint-sized “Ticklers” for sale, referring to small personal liquor flasks typically carried by men.[18] These pocket vessels had flattened sides, similar to the glass liquor flasks of the period. Numerous flask fragments were recovered (fig. 39). These small vessels were thrown as cylinders and then pressed while wet into a flat oval form. Suitable for drinking, the flasks had small, rounded-off mouths. No evidence of embellishment or decoration was found on these forms.

Chamber Pots

Chamber pots were readily identifiable by the rim profiles and the attachment of a strap handle at the lip (fig. 40). Although stoneware chamber pots rarely survive to become antiques, both archaeological and historical evidence suggests they were common production items at the DuVal pottery. Similarly shaped stoneware chamber pots were produced in Alexandria, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland.[19]

Many of the chamber pot fragments have cobalt highlights. The strap handles appear to have been pulled or extruded. Notably, the lower handle terminal has the DuVal dimple at the point of attachment.

Churns

DuVal advertised three sizes of churns: two, three, and four gallon. Several large rim fragments were tentatively classified as churns since they have a shelf, or flange, that might have supported a churn lid (fig. 41). Further analysis might reveal definitive evidence of the churn form.

Milk Pans

Milk pans are among the most common forms produced by earthenware potters in the eighteenth century.[20] Archaeological fragments of the form were notably absent from the DuVal assemblage, although one bowl-like fragment possibly represents a milk pan (fig. 42).

Inkstands

This small form is listed in several of DuVal’s advertisements at three dollars per dozen. The relatively low price suggests a simple container designed to hold ink and only a pen or two. Although stoneware potters are known to have produced more elaborate inkstands, typically they would have been special-order or presentation pieces.[21] No archaeological evidence of DuVal’s inkstands was noted, although some might come to light in the bulk of the fragments not fully analyzed.

Kiln Furniture

In addition to the thousands of jug fragments recovered, many jug “stackers” were found (fig. 43). These cylindrical devices were used to cover the jug necks during kiln loading to keep the stacks of pots level. Stackers had a central hole to allow for the release of kiln gases from inside the jugs, as well as a cutout to accommodate the jug handles (fig. 44). They provided evidence of multiple firings and heavy deposits of the salt-glaze and embedded sand grains that were used to keep them from fusing to the pots. The graduated sizes of the stackers reflects the size range of the jugs. All finished jugs bear the stacker’s signature contact marks and, in some cases, a distinctive two-tone finish (fig. 45).

Other recovered kiln furniture can be grouped into two general types (fig. 46): spacers and pads, and lumps of clay. Spacers and pads have a consistent form and were reusable for multiple firings. They had minimal contact with the pots in order to avoid sticking, although many examples of fused spacers were evident in the recovered wasters (fig. 47). Hand-formed clay lumps were used to seal cracks in the kiln or to serve as leveling devices in the stacking process and subsequent firing. Since these objects were hurriedly fashioned while wet, the fired examples often contain finger impressions of the workers. Once fired, this expedient kiln furniture probably was not reused.

Marks

At least two types of impressed marks were used on DuVal stoneware (figs. 49, 50). The most common, found both on extant and archaeological examples, is the “B. DuVal & Co. / Richmond.” Based on the historical evidence, this mark was probably used from the inception of the stoneware manufactory in 1811 and continued until 1817, when Benjamin’s son James took over the pottery business.[22] Upon this transfer of ownership, a new factory mark may have been used as evidenced by several examples recovered from the site. Based on the incomplete specimens found, the impressed mark may read “DUVAL STONEWARE MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND Va.” This mark in large block letters is similar to styles used by the Crolius and Remmey potting families in New York and by John P. Schermerhorn on his Richmond-made stoneware.[23] No intact vessel has been found that has this mark.

A surprising absence from the recovered fragments is capacity marks or stamps on any of the fragments. Fairly common on other American stoneware of this period, it seems unusual for DuVal not to have placed capacity stamps on his wares. No surviving DuVal vessels have impressed capacity marks, although a four-gallon jar attributed to the pottery has a brushed cobalt 4 on the shoulder (see fig. 22).

Finish and Decoration

In general, the DuVal stoneware forms are well thrown, having thin walls and even coverings of salt glaze. With the exception of the cobalt application to handle terminals, little decoration was added to the pots. One of the investigation’s most exciting discoveries was the recovery of a handful of sherds displaying sophisticated incised and cobalt-filled decoration (figs. 51-54). No extant DuVal vessels have yet been identified with this decorative technique, which was used more commonly on Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York stoneware of the period. Given that DuVal’s workforce was recruited from northern potting areas steeped in this tradition, a greater number of incised sherds might have been expected.

The use of minimal brushed cobalt on the handle terminals of both storage jars and jugs was prevalent. Other body fragments had traces of cobalt, although no discernible patterns could be determined. The jar illustrated in figure 19 and attributed to DuVal displays an abstract horseshoe-shaped cobalt decoration.

Another unusual use of cobalt was a “fingerprint” decoration appearing on jugs, jars (fig. 55), and at least one pitcher handle (fig. 56). This decoration type has not been noted on any other Virginia stoneware. One recovered jar clearly shows fingerprint impressions deliberately left behind, both a personal and permanent testament to the decorator (fig. 57).

Summary

The salvage investigation at the Benjamin DuVal pottery was an unexpected opportunity to examine in detail the products from one of the South’s earliest stoneware factories. Although the loss of the site was a blow for the historical preservation process, a relatively large sample of stoneware fragments and kiln furniture was preserved for posterity. Perhaps the greatest loss was the destruction of the kiln foundation(s), which surely would have provided details of architectural form and function. Also lost was the opportunity to examine the spatial relationship of the pottery’s kiln(s), workshop, and other features.

It is possible that future archaeologists excavating Richmond landfills may be surprised by discovering previously unrecorded specimens from the DuVal pottery. Until then, the fragments illustrated in this article can be used as a guide by curators and collectors for positively identifying DuVal stoneware. Of particular importance will be the search for the incised examples that the DuVal pottery produced. Perhaps extant pieces have simply been labeled as New York examples.

There is no doubt that the DuVal stoneware manufactory is just one of many sites forgotten and buried in the central Virginia area. Can these other sites be spared the same fate? Only if archaeologists or ceramic historians receive the necessary funding. Unfortunately, few institutions and academic organizations are in the business of supporting research projects of this type. It is ironic that the sums collectors pay for a single documented piece of stoneware could pay for months of archaeological research. Perhaps a new approach is needed, to encourage interested collectors—rather than institutions—to become involved in such worthy endeavors.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “‘B. DuVal & Co/Richmond’: A Newly Discovered Pottery,” Journal of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts 4, no. 1 (May 1978), pp. 45–75.

Throughout Rauschenberg’s article the large jar is inexplicably referred to as a “jug.”

Virginia Gazette and General Advertiser, February 23, 1791, p. 3.

Virginia Argus, March 18, 1808, p. 3. Benjamin DuVal served as president of the Mutual Assurance Society and probably entered into the roofing tile manufacture as he saw the need for fireproof tiles. Rauschenberg, “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond,” p. 51.

The Enquirer (Richmond), August 9, 1811, p. 3.

Richmond’s first stoneware manufactory and among the earliest such operations in the entire South. The major exception is William Rogers’s ca. 1720 stoneware factory in Yorktown, Virginia. See Norman F. Barka, Edward Ayres, and Christine Sheridan, “The ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown: A Study of a Colonial Pottery Factory,” vol. 1: History, Yorktown Research Series no. 5 (Williamsburg, Va.: College of William & Mary, 1984); Norman F. Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory: The Kilns and Ceramics of the ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.:University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 15–47.

Listed in the 1820 Census of Manufacturers, Henrico County, Virginia, are: “Thomas Amos, stoneware manufactory”; “Samuel Frayser, Stoneware manufactory &c.”; “John P. Schermerhorn, Stoneware of all kinds”; and “Samuel Wilson, stoneware of all kinds.” Also see Robert Hunter, Kurt C. Russ, and Marshall Goodman, “Eastern Virginia Stoneware,” Antiques 167, no. 4 (April 2005), pp. 126–33.

The site was recorded in the Virginia Department of Historic Resources files as 44HE592 on March 18, 1985.

The DuVal site was adjacent to several ca. 1850 warehouses that had served as Confederate hospitals during the Civil War. Relic hunters reported finding dozens of uniforms buttons on the property.

See www.archaeology.org/online/news/duval.html (accessed June 17, 2005).

Holly Clark, “The Past in Pottery,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 10, 2002, p. B1.

I am grateful for the efforts of the many volunteers who joined the eVort to recover material from the sites. Initial help was provided by Marshall Goodman and Larry Lindberg; individuals from several archaeological institutions and consulting firms volunteered their time, among them Jerry Blake, Michelle Brumfield, Robert Clarke, Jason Cline, Brad Duplantis, Harry Jaeger, John Kille, Brad McDonald, Melissa Money, John Mullin, Merry Outlaw, Tony Opperman, Joe Parfitt, Al Pfeffer, and Chris Stevenson. Special thanks to David Hazzard and Madison Washburn.

For a full account of this history, the reader is referred to Rauschenberg, “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond.”

Assisting in the washing and sorting of the material were Sally Greenbaum, Stan Greenbaum, Ruth Hunter, Bob Hunter, Julie Hunter, John Kille, and Merry Outlaw.

Richmond Enquirer, December 16, 1815, p. 3.

Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 2801 Kensington Avenue, Richmond, VA 23221 (www.dhr.virginia.gov/).

An advertisement noted the “Richmond Stone Ware Manufactory, at the sign of the Jug.” Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817, p. 3.

Harold Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery (Philadelphia, Pa.: Chilton Book Co., 1971).

See John E. Kille, “Distinguishing Marks and Flowering Designs: Baltimore’s Utilitarian Stoneware Industry,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 93–132.

Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory,” p. 32.

See Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stoneware: The Art & Craft of Utilitarian Potters, 3rd rev. ed. (Atglen, Pa.: SchiVer Publishing Ltd., 1999), p. 139.

Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817.

See Greer, American Stoneware, p. 139; Kurt C. Russ and W. Sterling Schermerhorn, “Rocketts’ Red Glare: John P. Schermerhorn and the Early Richmond Area Stoneware Industry,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 61–92.