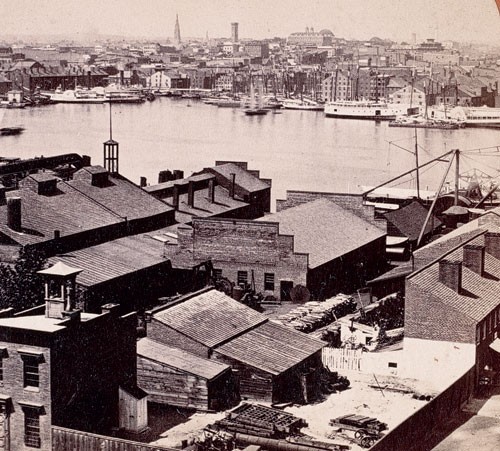

Late-nineteenth-century view from a stereoscope card of the Baltimore Basin (present-day Inner Harbor) looking north from historic Federal Hill toward the city’s commercial center.

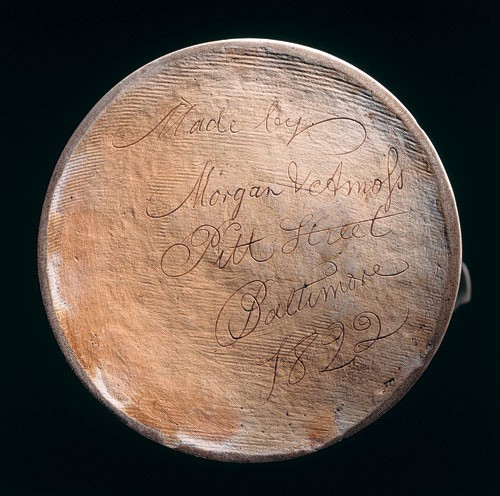

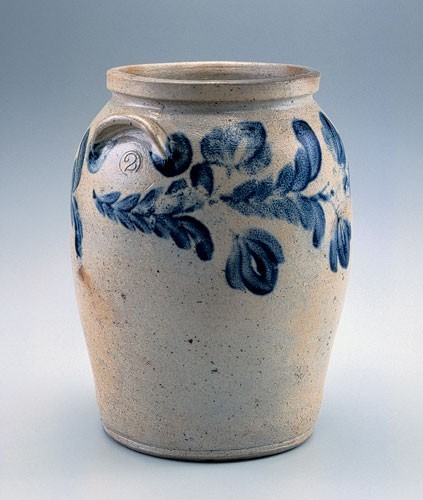

Jar and milk pan, Baltimore, ca. 1819–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 8 1/4". Likely made 1819–1825 by William H. Morgan when he was associated with Morgan and Amoss, or later, during “Morgan Maker” period. Right: H. 6". Incised in freehand on bottom: “Made by Morgan & Amoss Pitt Street Baltimore 1822” (see detail, fig. 3). (Unless otherwise noted, all objects are from the author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos are by Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bottom of the milk pan illustrated at right in fig. 2.

Jars, Baltimore, ca. 1819–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Right: Incised, in freehand, “Pitt St. Baltimore.” These one-gallon vessels are similar in form, and their distinctive slipped floral decorations are characteristic of patterns on vessels marked “Morgan & Amoss” and “Morgan Maker.”

Detail of the bottom of the jar illustrated on the right in fig. 4.

Jars, Baltimore, ca. 1830s–1840s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2" and 10". The placement of the inscription “Baltimore” on these two jars highlights the random manner with which potters inscribed vessels.

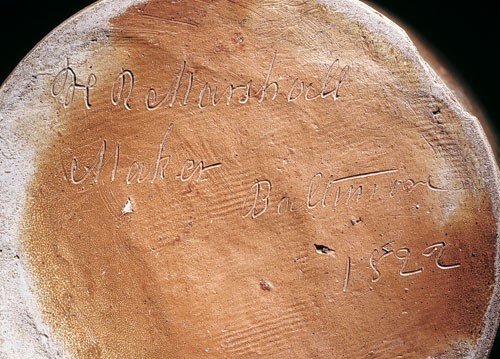

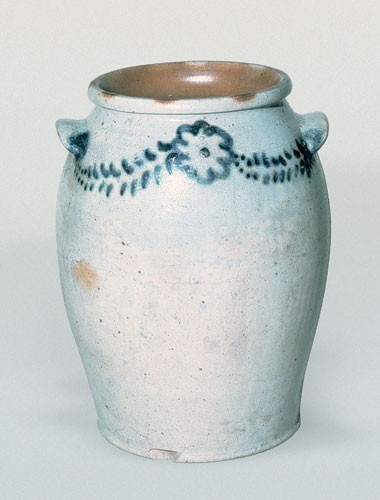

Jars, Hugh R. Marshall, Baltimore, 1822. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 15 1/2". Incised in freehand on bottom: “H. R. Marshall Maker Baltimore 1822.” Right: H. 13". The jars have identical rims and similarly impressed gallon-capacity numbers outlined in cobalt decoration.

Bottom of the jar illustrated on the left in fig. 7.

Jar, H. R. Marshall, Baltimore, probably 1820s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2".

Jars, Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, ca. 1860s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2" and 8 1/4". These plain one-gallon jars are marked “P. Herrmann.”

Teapot, Baltimore, 1826. Earthenware. (Courtesy, National Park Service.) This partially mended vessel was excavated at City Point, Virginia.

Fragment of incised base from teapot illustrated in fig. 11. (Courtesy, National Park Service.)

Jars, Baltimore. Salt-glazed stoneware, ca. 1819–1825. Left: H. 13 1/4". Attributed to either the Morgan and Amoss or “Morgan Maker” periods. Right: H. 12". Incised on bottom: “Morgan & Amoss Makers Pitt Street Baltimore 1821.” The jars are similar in form and share repeating floral decoration and looped or coiled handles.

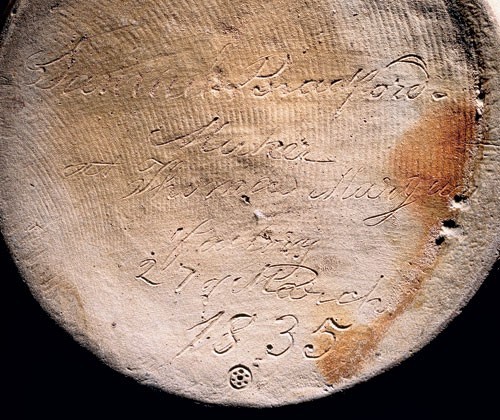

Jar, Thomas Morgan Factory (Samuel Bradford), Baltimore, 1835. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Two-gallon capacity. Inscribed on bottom: “Samuel Bradford Maker at Thomas Morgan’s factory, 27 March 1835.”

Bottom of the jar illustrated in fig. 14.

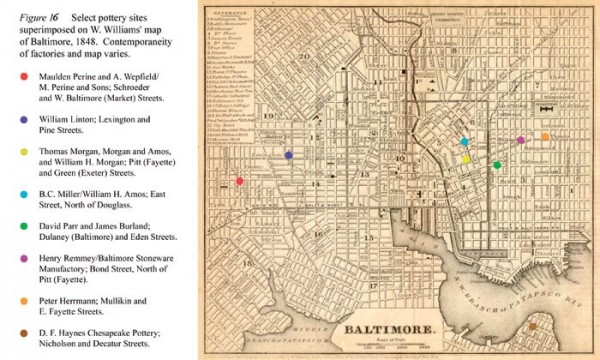

Select pottery sites superimposed on W. Williams’s map of Baltimore, 1848. The contemporaneity of the factories on the map varies..

Jar, Baltimore Union Stoneware Manufactory, Baltimore, nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". Impressed “BALTIMORE UNION STONEWARE MANUFACTORY.”

Jar, Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, 1860s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". This two-gallon jar, marked “P. Herrmann,” is decorated with unusual repeating tulips.

Jar, Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, ca. 1860s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Impressed with “P. Herrmann” maker’s mark.

Container, William Linton, Baltimore, ca. 1849–1877. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 24 3/4". Impressed “WILLIAM LINTON'S POTTERY AND SALESROOM Corner of Lexington and Pine Streets, BALTIMORE, MD.” A sweeping pattern of brushed flowers enhances this rare oversize vessel.

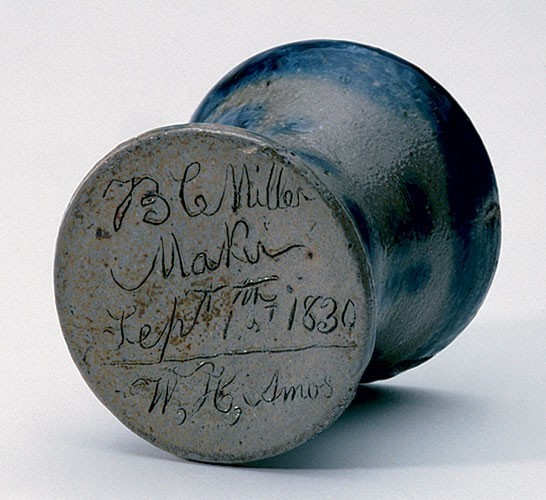

Sand caster, Benjamin C. Miller, Baltimore, 1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2 7/8". Inscribed on bottom: “B.C. Miller Maker September 1st 1830 William H. Amos.” (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Sand caster, Benjamin C. Miller, Baltimore, 1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2 7/8". Inscribed on bottom: “B.C. Miller Maker September 1st 1830 William H. Amos.” (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

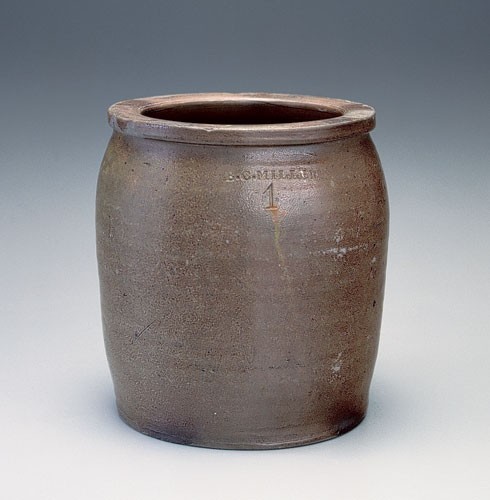

Jar, Benjamin C. Miller, probably Baltimore, ca. 1830–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". Impressed on the shoulder with the maker’s mark “B. C. MILLER.”

Inkwell, Phillip Miller, Baltimore, 1838. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2'', D. 4''. Incised on base: “P. Muller / Present fur die / Sontag Schule der 2 / Deutchen Luterishen / Kirche”; incised on top: “Phillip Miller / Juli 4th 1838.” (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.)

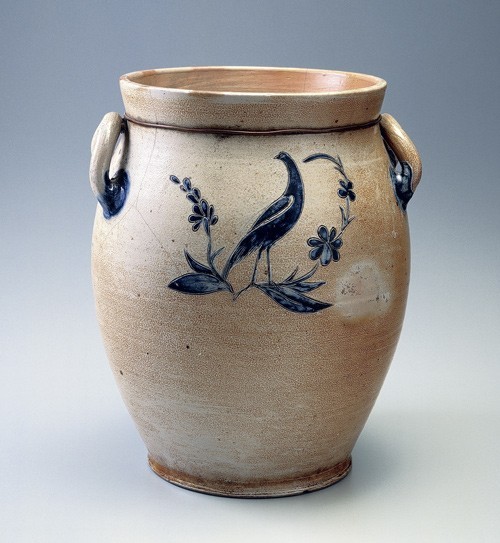

Jar, Morgan and Amoss, Baltimore, 1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". Inscribed in freehand on bottom: “Morgan & Amoss Makers Baltimore 1820.” This rare jar is incised with two large, fanciful birds—one looking forward, the other looking behind—surrounded by graceful floral designs. The vessel has been reinforced with an old piece of copper wire placed under the rim. The decorative style and elements match those on an unsigned flowerpot previously attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. (see Zipp, Ceramics in America [2004], p. 154). The fact that both vessels show a backward-looking bird with slanted eyes standing on pointed leaves next to seven-petaled flowers and rounded flowering shoots suggests that both pieces were made by Morgan and Amoss, or perhaps both makers used the same decorator.

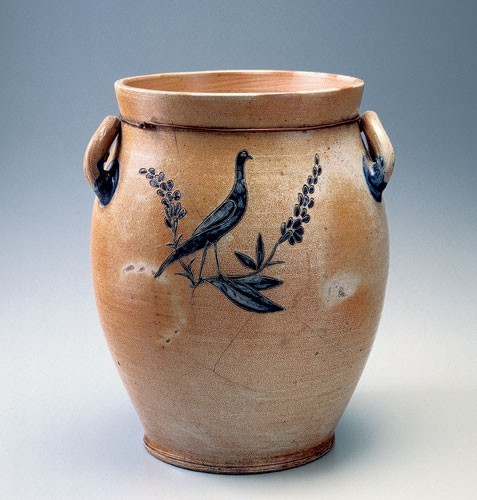

Reverse view of the jar illustrated in fig. 24.

Detail of the bottom of the jar illustrated in fig. 24.

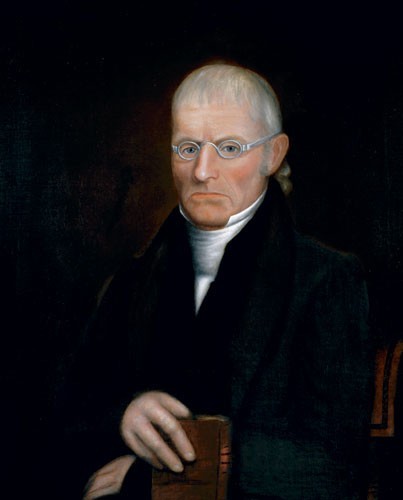

Portrait of Thomas Morgan, ca. 1830. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.)

Jar, Morgan and Amoss, Baltimore, ca. 1819–1822. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Incised on one side: “Morgan & Amoss Makers.”

Pitcher, William H. Morgan, Baltimore, Maryland, 1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 5/8". Inscribed on the side and bottom: “Morgan Maker Pitt Street Balto 1823.” (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Jar, William H. Morgan, Baltimore, ca. 1823–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 5/8". This three-gallon jar with slipped floral decoration is incised “Morgan Maker Balto.” (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Jug, William H. Morgan, Baltimore, ca. 1823–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8". Incised on one side: “Morgan Maker.”

Jug, William H. Morgan, Baltimore, ca. 1823–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". This three-gallon ovoid jug is incised “Morgan Maker” below its neck.

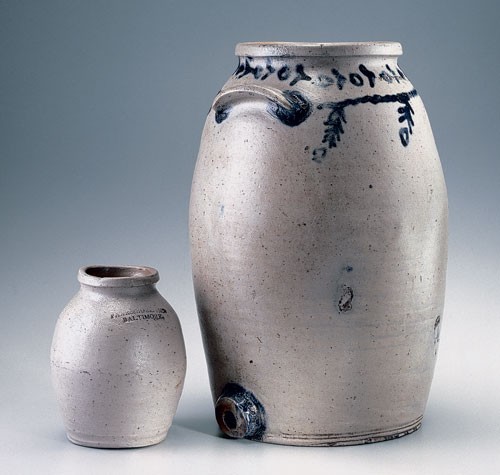

Jar and cooler, David Parr and James Burland, Baltimore, ca. 1815–1828. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7" and 16 1/2". Both vessels are impressed “PARR & BURLAND BALTIMORE.” The misalignment of the cooler’s bunghole in relation to its handles is intriguing. Was the positioning intentional or an oversight of the potter?

Churn, Maulden Perine, Baltimore, 1851. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". This distinctive hanging flower pattern is characteristic of those found on wares made by Perine. Incised in freehand on bottom: “Baltimore Md 1851 711 Market St.” Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1851 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1851), p. 210, lists Maulden Perine at this address.

Bottom of the churn illustrated in fig. 34.

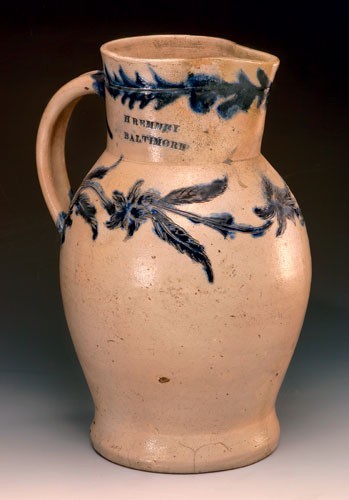

Pitcher, Henry Remmey, Baltimore, ca. 1812–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". Incised flowers and leaves distinguish this exceptional pitcher marked “H. REMMEY BALTIMORE.” (Courtesy, Henry Ford Museum.)

Pitcher, M. Perine and Sons (Adam Wipfield), Baltimore, 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 27". This profusely decorated oversize pitcher is dated “1870” and incised “A. Wipfield.” (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.)

Chamber pots, probably Baltimore, ca. 1820s–1860s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/8", 5 5/8" (shown on pedestal), and 6 1/2". Whereas different decorative styles and techniques indicate different periods of manufacture—left, ca. 1820s; right, ca. 1830s; top, ca. 1860s—these chamber pots share the same enduring form.

Milk pan and jar, Baltimore, ca. 1819–1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 3 3/4". Incised on bottom: “Pitt Street Baltimore 1824.” Right: H. 8". Both vessels are decorated with undulating and repeating slipped floral designs, motifs that are also associated with examples marked “Morgan & Amoss” and “Morgan Maker.”

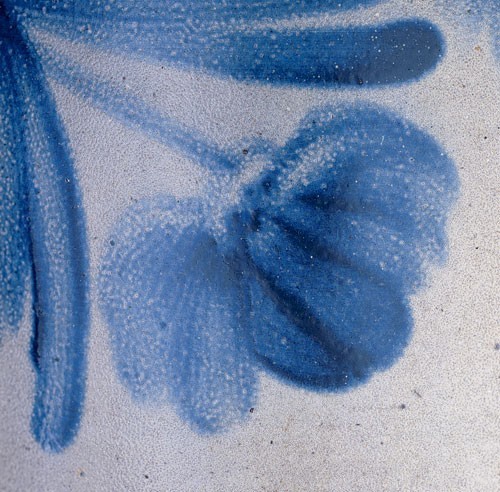

Detail of the decoration on the milk pan illustrated in fig. 2, right.

Detail of the decoration on the ca. 1820s chamber pot illustrated in fig. 38.

Detail of the decoration on the reverse side of the jar marked “H. R. Marshall” illustrated at left in fig. 7.

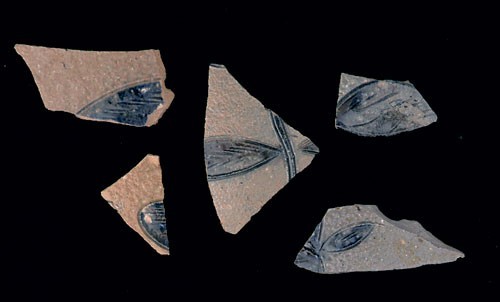

Stoneware sherds excavated at the site (18ANBC1) of the Thomas Morgan factory at Pitt and Exeter (Green) Streets in 1961 by the members of the Archeological Society of Maryland. Dr. Gregory Stiverson, director of the Historic Annapolis Foundation, discovered this archaeological collection, which was placed in storage several decades ago and subsequently forgotten.

Bottles, Baltimore, ca. 1830s– 1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2" and 6 1/2". Left: Impressed “BEST COLOGNE GIN FROM ERSKINE & EICHELBERGER BALTIMORE.” Right: Impressed “F. SANDKUHLER.”

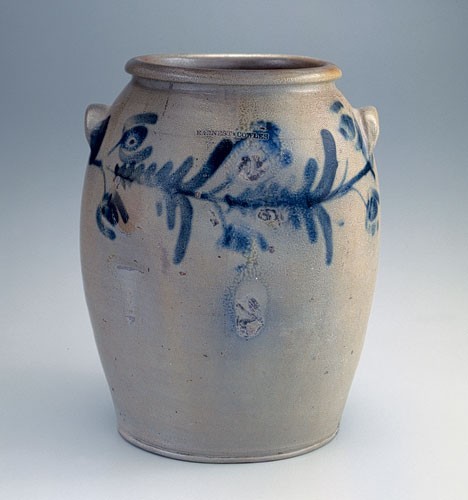

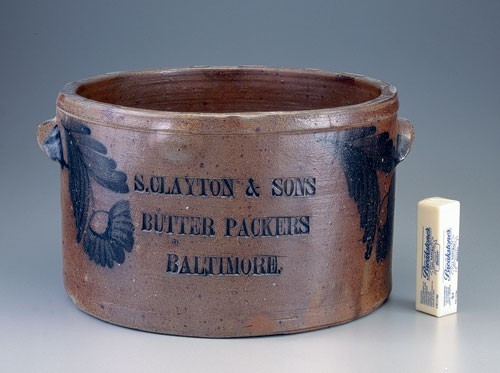

Crock, probably Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1851. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Stenciled “Clayton & Hewes Butter Dealers Baltimore.” City directories reveal the firm of Clayton and Hewes existed in 1851, a partnership that lasted just one year. (Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1851, p. 56.) A similar example was made for S. Clayton and Sons Butter Packers (see fig. 59). Both vessels share similarly applied ears and brushed decoration characteristic of Baltimore manufacture.

Reverse of the crock illustrated in fig. 45.

Detail of the decoration on the marked Perine churn illustrated in fig. 34.

Detail of the decoration on the jar made at the Thomas Morgan factory illustrated in fig. 14.

Miniature jug, probably Baltimore, mid-19th century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3". Ambrotype photograph mounted in case, ca. 1855–1858.

Jugs, Baltimore, ca. 1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware and copper. Back: H. 13". Impressed “JM KAVANAGH.” Front: H. 7 1/2". Impressed “STRUVEN & WACKER GROCERS & SHIP CHANDLERS COR, CHESTER & ALICE ANN ST BALTIMORE.”

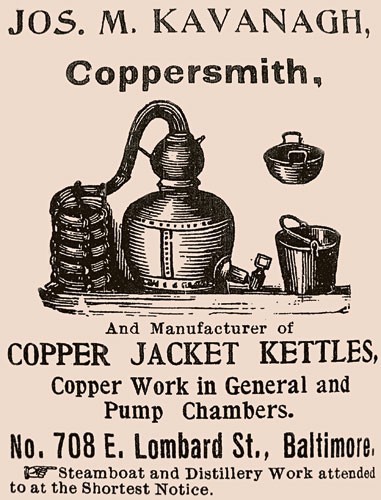

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1895 advertisement for coppersmith Joseph M. Kavanagh.

Pitchers, Baltimore, ca. mid-19th century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9" and 15 1/2". These pitchers are decorated with a characteristic three-petaled flower design that is associated with wares made in Baltimore.

Mug, Baltimore, ca. late 1880s–early 1890s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". Impressed “A MEINECKE 2834 BOSTON STREET BALTIMORE.”

Reverse of the mug illustrated in fig. 53. Gold paint and daisies were added at a later date.

Jar, Baltimore, ca. late 1830s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". “MYERS & BOKEE” is impressed with precision on the outer rim of this one-gallon jar, an unusual location.

Jar, Baltimore, ca. 1830s–early 1850s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". This three-gallon jar is impressed “EARNEST & COWLES.”

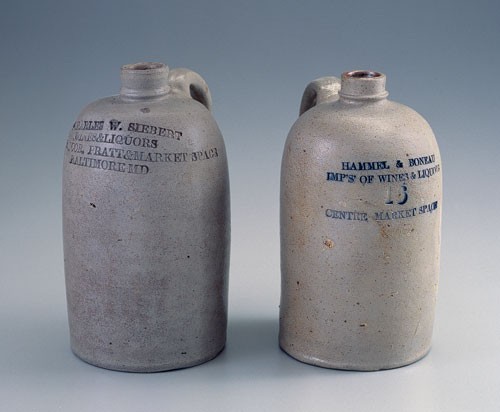

Jugs, Baltimore, ca. mid-1870s–early 1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 7 3/4". Impressed “CHARLES W. SIEBERT WINES & LIQUORS N.E. COR. PRATT & MARKET SPACE BALTIMORE MD.” Right: H. 7 1/2". Impressed “HAMMEL & BONEAU IMP’S’ OF WINES & LIQUORS 16 CENTRE MARKET SPACE.”

Coolers, Baltimore, ca. 1870s. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 16". Impressed “DR. B. BATES, WINE CIDER.” Right: H. 13 3/8". Impressed “MEETER & BRO.”

Butter crock, Baltimore, ca. 1845–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Impressed “S. CLAYTON & SONS BUTTER PACKERS BALTIMORE.” The stick of butter highlights the unusually large size of the crock.

Jug, Baltimore, ca. 1870s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". Impressed “NUMSEN’S YACHT. CLUB VINEGAR.

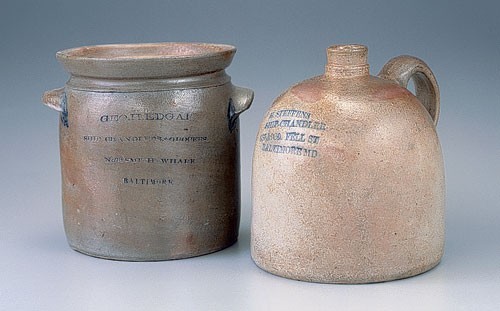

Jar and jug, Baltimore, ca. 1870s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 7". This jar once had a lid and is impressed “GEO. H. EDGAR SHIP CHANDLERS & GROCERS NO. 73 SMITH'S WHARF BALTIMORE.” Right: 7 1/2". Impressed “H. STEFFENS SHIP-CHANDLER 987 & 989. FELL ST BALTIMORE MD.”

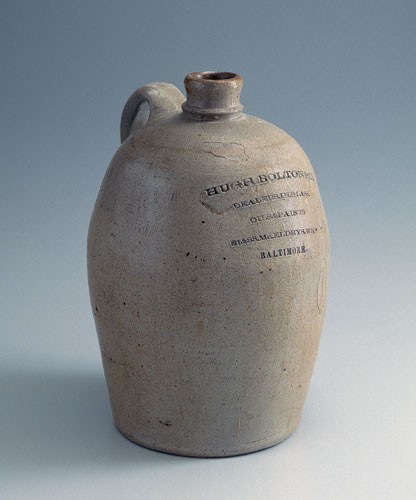

Jug, Baltimore, ca. 1870s–1880s Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Impressed “HUGH BOLTON & CO. DEALERS IN GLASS, OILS & PAINTS, 81 & 83 MCELDRY’S. WHF BALTIMORE.”

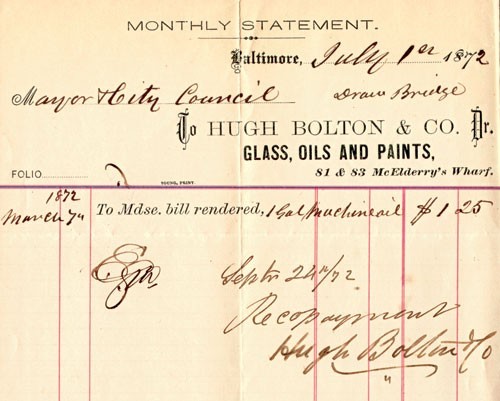

Billhead receipt from Hugh Bolton & Co., July 1, 1872.

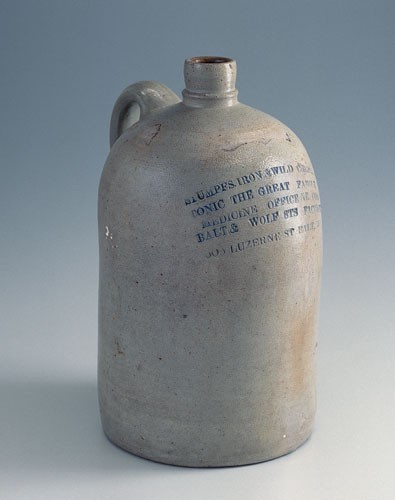

Jug, Baltimore, ca. 1870s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". Impressed “STUMPFS. IRON & WILD CHERRY TONIC THE GREAT FAMILY MEDICINE, OFFICE N.E. COR BALT, & WOLF STS FACTORY 605 LUZERNE ST BALT MD.”

Jar, probably Baltimore, ca. 1860s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Impressed “BS HOOPER DEALER IN GROCERIES & LIQUORS FARMVILLE VA.”

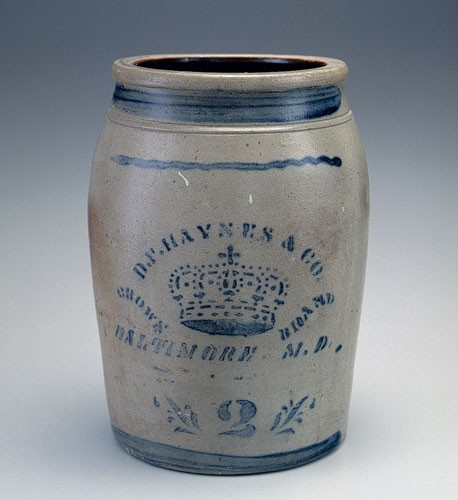

Jar, Western Pennsylvania, ca. early 1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". This two-gallon jar is stenciled “D. F. HAYNES AND CO. CROWN BRAND BALTIMORE M.D.”

Postcard detail of D. F. Haynes & Sons Chesapeake Pottery at Nicholson and Decatur Streets, dated October 2 (20?), 1905. The handwritten inscription on the front—“A remembrance of the old place to show you that you are not forgotten. [signature illegible]”—suggests that this card was sent to a former employee at the factory.

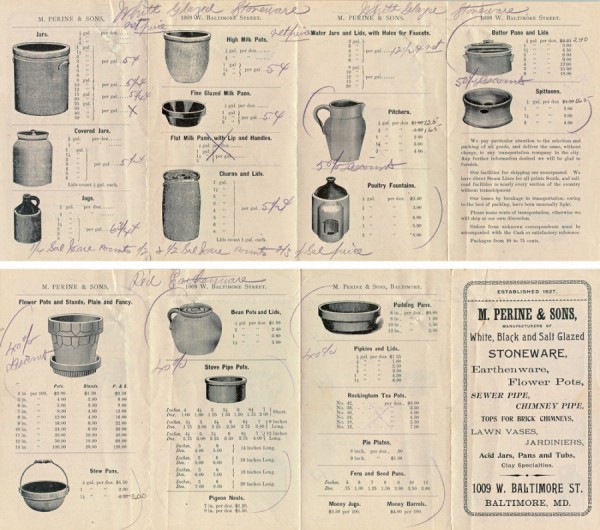

Price list, M. Perine & Sons, 1895. Top: “White Glazed Stoneware.” Bottom: “Red Earthenwares.”

Jar and pitcher, late nineteenth century. Bristol white-glaze stoneware. Left: H. 10". A three-petal motif appears on both sides of this jar of unknown origin. Right: H. 6 1/2". Cobalt stenciling reads “SNOW, KNOX & CO. WHOLESALE GROCERS & FLOUR MERCHANTS 103 & 105 CHEAPSIDE BALTIMORE, MD.” This type of pitcher has also been seen with the impressed maker’s mark of the Burley and Winter Pottery, located in Crooksville, Ohio.

Pitcher, possibly Thomas Haig, Philadelphia, late ninetheenth century. Bristol white-glaze stoneware. H. 10".

An assemblage of marked vessels and related documentary evidence provide the basis for conducting a broad survey of utilitarian stoneware produced by Baltimore potters during the nineteenth century. This sizable study collection illustrates the types of wares made in the city during this period, the functional qualities associated with their use, and their relationship to cultural, economic, and technological forces.

The thriving stoneware industry that once existed in this important port city warrants this type of examination. Workers benefited from native clay sources,[1] a solid manufacturing base, and proximity to overland travel and coastal trade routes (fig. 1). These highly skilled artisans—family members, immigrants, and trained apprentices—practiced distinctive craft-making traditions, and, as elsewhere, Baltimore’s potters eventually saw their world transformed by industrialization.[2] Mechanization and mass production increased competition from regional factories and manufacturers of glass and metal containers and presented them with enormous challenges.

Over the last half century several scholars have conducted research on Baltimore’s stoneware industry. John N. Pearce’s master’s thesis, “Early Baltimore Potters and Their Wares, 1763–1850,” was a largely historical account of stoneware production.[3] In 1984 Susan Myers published an insightful marketing case study based on the 1839–1840 daybook belonging to Maulden Perine, a prolific Baltimore potter.[4] Most recently, Luke Zipp provided a detailed account of the connections between the Myers family of china merchants and wares attributed to potter Henry Remmey.[5] However, no attempt has been made to analyze a large assemblage of stoneware vessels associated with Baltimore manufacture.

The need for this type of broad overview is underscored by a 1998 archaeological report that documented excavations at the nineteenth-century kiln site owned by Baltimore china merchant James Pawley Sr.[6] In evaluating artifacts recovered from the site, the authors of the report had little choice but to compare decorative motifs and forms against similar stoneware made by regional potters, notably from Alexandria, Virginia, because, as they pointed out, “no collections from other Baltimore potters have been analyzed systematically, and no comparative data was readily available without extensive research and analysis.”[7]

There are a number of reasons why documenting the material culture associated with Baltimore’s stoneware industry has proven challenging. The city’s potters rarely and intermittently marked their wares. Also, many of the stoneware forms and motifs produced in Baltimore are similar in some respects to wares that originated in other areas. As a result, many misconceptions and general confusion surround the identification and attribution of these wares. Compounding this situation is the city’s sketchy archaeological record, with historic contexts disturbed by urban development, an absence of governmental oversight, widespread looting for profit, and limited opportunities to conduct scientific salvage excavations.

The study collection examined here is by no means intended to be wholly representative of individual Baltimore potters, the wares they made, or the stoneware industry itself throughout the nineteenth century. However, these artifacts contain valuable information that can be used for making positive identifications, comparisons, attributions, and general typologies. In addition, they provide glimpses into the past—snapshots in time—which, when viewed together, help to bring this industry into clearer focus. This study will look specifically at the utility and limitations of Baltimore stoneware maker’s marks, characteristic types of decoration, functional aspects of utilitarian wares, different forms of marketing, and the mechanization of what was once a craft industry.

Baltimore Maker’s Marks: Utility and Limitations

Nineteenth-century Baltimore stoneware potters are known to have used several different types of maker’s marks such as freehand incising, stamps, and impressed typeset lettering, sometimes filled or underlined with cobalt for heightened visibility. For instance, the underside of one item, a milk pan (figs. 2 [right], 3), identifies the maker (Morgan & Amoss), street (Pitt), city (Baltimore), and date (1822), whereas the underside of another, a jar (figs. 4 [right], 5), is incised with just a street (Pitt) and city (Baltimore). Other unidentified potters specified only the city of origin (Baltimore) (fig. 6). The potter Hugh R. Marshall signed his wares with freehand incising (figs. 7, 8) and impressed typeset (fig. 9). A much later factory, run by Peter Herrmann, identified wares with impressed stamps bearing his name and the item’s capacity (fig. 10). Some makers also used individual numerical gallon-capacity stamps, which can be helpful in identifying factories.

Certainly there are many more potters and shops for which identifying marks have never been documented. However, the range of marks used by the Baltimore makers represented here raises the question, what motivated factories to add yet another labor-intensive step to production? Possible answers might include a reaction to intense local competition, a desire to add a lasting legacy to a “presentation” piece made for a special occasion, or a need to identify the place of manufacture, especially for exported wares. In fact, Baltimore potters regularly exported wares to Southern markets, and archaeologists in Virginia recently excavated an earthenware teapot with “Baltimore 1826” inscribed on the bottom (figs. 11, 12).[8]

Marked stoneware vessels are particularly useful for making cautious attributions that otherwise would be impossible. For example, a comparison of unmarked vessels and marked wares made by the firm of Morgan and Amoss (see figs. 2, 13) and Hugh R. Marshall (see fig. 7) clearly illustrates the utility of using maker’s marks to compare similar vessels. However, making definitive attributions to specific potters and factories is sometimes difficult for several reasons. For instance, the unsigned jars in figures 2 and 13 could have been produced by William H. Morgan between 1819 and 1822, while he was associated with the firm Morgan and Amoss, or between 1823 and 1825, when he presumably worked by himself and is recorded signing wares “Morgan Maker.”[9] Further, while we know that Hugh R. Marshall made the vessel on which he inscribed his own signature (see fig. 7, left), we do not know for certain whether he made it in his own shop or at a factory owned by someone else. Conversely, another vessel impressed “H. R. Marshall” (see fig. 9) could have been made in Marshall’s own shop but by another potter, if he had one working for him. Taking this one step further, if Samuel Bradford had left his own name off the inscribed jar he made in the shop of Thomas Morgan (figs. 14, 15), one could be left with the impression that Thomas Morgan himself had made this particular piece.

Potters operated shops and kilns throughout the city—near populated urban areas, residential neighborhoods, commercial districts, and transportation outlets (fig. 16). What follows is an overview of Baltimore stoneware potters and factories that are known to have used various types of maker’s marks.[10]

BALTIMORE UNION STONEWARE MANUFACTORY

A one-gallon jar marked “BALTIMORE UNION STONEWARE MANUFACTORY” is an extremely rare vessel, for which definitive supporting documentation has yet to be found (fig. 17). Another operation with a similar name, the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, was established in 1812 by china merchant William Myers and later owned by Jacob Myers and his son Henry. However, no connection between the Myers family enterprise and the Baltimore Union Stoneware Manufactory has been established.

SAMUEL BRADFORD, FOR THOMAS MORGAN

The inscription on the underside of an extremely rare two-gallon stoneware jar made in Thomas Morgan’s factory at Pitt and Green Streets (see figs. 14, 15) provides an unusual amount of information: “Samuel Bradford Maker at Thomas Morgan’s factory, 27 March 1835.” This example identifies the work of the potter, who ordinarily would remain anonymous. It also records the type of decorated stoneware that the Morgan pottery produced just before its demise about 1839.[11]

Thomas Morgan produced stoneware at Pitt and Green Streets in Baltimore over a period of five decades, starting perhaps as early as 1795 (see fig. 27).[12] He and Joel Morgan (probably a relation) and Peter Perine are named in a 1798 petition—signed by a group of fourteen neighbors and filed with city officials—expressing serious concerns about their stoneware operation. The document provides a rare firsthand account of the perils of locating firing kilns in close proximity to residential neighborhoods:

To the Hon.ble the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore.

The Memorial and Petition of the Subscribers, inhabitants of a part of the City of Baltimore, lying East of Jone’s Falls,

HUMBLY REPRESENT,

That some of your Memorialists reside opposite, adjoining and near to a Stone-Ware Pottery, owned by Thomas and Joel Morgan and Peter Perine, situate(d) at the corner of Pitt and Green streets, which they conceive to be truly dangerous and alarming, owing to the prodigiously large fires kept up during the whole of the day, and particularly throughout the following night, in burning off their Ware, close to a board fence which has often taken fire, and old wooden buildings containing straw, shavings, &c. for packing, as well as large quantities of wood piled up, and scattered over the yard, inasmuch as some of your Memorialists are kept in continual dread of fire being communicated to their dwellings, as also suffocation in their houses by emission of vast bodies of strong, black smoke.

Your Memorialists come forward rather reluctantly than otherwise, against any of their neighbours, with their present respresentation of facts; but are under the necessity of doing so for their own security, (more especially at this time, when alarming and distressing fires so frequently happen) which they hope your honourable body may take into serious consideration, and grant such relief to the concerned as may seem just and reasonable; and your Petitioner, as in duty bound, will ever pray, &c.[13]

The city’s nuisance laws affecting potters grew increasingly restrictive throughout the nineteenth century, particularly with regard to kiln stack emissions and formal approval of kiln designs and construction plans.

PETER HERRMANN

On September 16, 1844, nineteen-year-old Peter Herrmann, his parents, Richard and Catherine, and his sister, Christian, arrived in the port of Baltimore on the ship Prentiss, having emigrated from Bremen, Germany.[14] In 1852 Herrmann became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[15] In 1855 he is identified as a potter at 149 North Caroline Street, and is later working as the proprietor of the Jackson Square Pottery fronted by Mullikin and East Fayette Streets.[16]

After 1880 Herrmann is known to have set up shop in the Middle River area of outlying Baltimore County. However, he apparently returned to Baltimore City in 1888–1889; city directories identify him as a clerk in his son Albert’s short-lived pottery on 704 Ensor.[17] By 1894 he had again left the city, to operate a pottery in Brooklyn in nearby Anne Arundel County, where he worked for the next two years.[18] The remaining years of his life were spent in Baltimore, and he is listed as a potter in city directories as late as 1899, two years before his death.[19]

Over the years Herrmann produced an extensive line of wholesale utilitarian stoneware for local and regional retailers. While collectors generally associate his work with a brushed three-petaled flower design and impressed advertising jugs and crocks, he also made undecorated wares and used other floral motifs as well (see figs. 10, 18, 19).

WILLIAM LNTON

An oversize stoneware jar with exuberant floral decoration bears the maker’s mark of William Linton (fig. 20). After emigrating to Baltimore from England, Linton began working for Maulden Perine in 1840 and the two eventually formed a partnership.[20] In 1849 Linton received the approval of the Baltimore City Council to reconstruct a kiln on the northwest corner of Lexington and Pine Streets, the location of Perine’s earlier factory.[21] The new factory was referred to as William Linton and Co. By 1853 Linton was manufacturing “Stone and Earthenwares of every description; also, Chemical Stoneware, such as receivers, to hold from ten to thirty gallons, with or without spigots, with connecting pipes of all shapes, and Plain and Ornamental Chimney Pots, Tobacco Pipe Heads, &c. &c.”[22] Sometime after 1866 Linton and his son William G. Linton operated it as Linton & Co.[23] William G. carried on the business until 1877.

HUGH R. MARSHALL

Fifteen-year-old Hugh Robbins Marshall signed an apprenticeship to potter Thomas Morgan in 1810.[24] Curiously, no mention of him is found in Baltimore directories between 1810 and 1840. The jars illustrated in figures 7 and 9 are exceedingly rare; the inscribed three-gallon one shown in figure 7 would have been made when Marshall was twenty-seven.

BENJAMIN C. MILLER, FOR WILLIAM H. AMOSS

City directory listings for Benjamin C. Miller identify him as a potter situated at Low Street near Aisquith Street in 1831 and at Douglas Street near Forest Street in 1833.[25] He is best known for a decorated stoneware sand caster (fig. 21), which now is preserved in the collection of the Winterthur Museum. Miller made this involved piece at William H. Amoss’s East Street shop, although an undecorated one-gallon jar has surfaced with Miller’s own maker’s mark (fig. 22)—an extremely rare find.

PHILLIP MILLER

A stoneware inkwell made by potter Phillip Miller in 1838 for the Sunday school of a German Lutheran church is in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society (fig. 23). This unusual presentation piece is decorated with a cobalt floral design and is inscribed in German, reflecting the large numbers of immigrants who lived and worked in Baltimore during this period. It is not known whether Phillip Miller was related to the potter Benjamin C. Miller. However, on two separate occasions Phillip did share an address with Lewis Miller, who potted for a very brief period and may have been a relative.[26] Also, it is possible that Phillip Miller worked in Maulden Perine’s stoneware factory in 1840, as both are listed at “Schroeder Street south of Baltimore” in the city directory for that year.[27]

MORGAN AND AMOSS (WILLIAM H. MORGAN AND THOMAS AMOSS)

In 1812 Thomas Morgan and his brother-in-law William H. Amoss formed a pottery and began producing stoneware at Pitt and Green Streets.[28] The enterprise, known as Morgan and Amoss, lasted until 1815.[29] Subsequently, Thomas Morgan and another of his brothers-in-law, Thomas Amoss, established Thomas Amoss and Co., which produced stoneware at the same location until 1819. The dissolution of this firm provided an opportunity for a new set of partners, William H. Morgan (Thomas Morgan’s son) and Thomas Amoss, to reestablish Morgan and Amoss.[30] A central figure in each of these business ventures is Thomas Morgan, owner of the works at Pitt and Green Streets.[31]

The second firm of Morgan and Amoss regularly marked its wares with freehand inscriptions, and several examples in this study are dated: 1820 (fig. 24), 1821 (fig. 13, right), and 1822 (fig. 2, right). An undated marked jar is illustrated in figure 28. In addition to his involvement with Morgan and Amoss, Thomas Amoss also operated a stoneware factory in Henrico County, Virginia. According to 1820 census records he owned one kiln and three wheels, employed four men, and used fifty tons of clay, eighty cords of wood, and fifteen sacks of salt.[32] Thomas Amoss died in 1822, and his Virginia factory was included in his will.[33]

MORGAN MAKER (WILLIAM H. MORGAN)

After the demise of the Morgan and Amoss partnership, William H. Morgan began incising stoneware with “Morgan Maker” (fig. 29), a practice he is known to have continued until at least 1825, and possibly 1827, the last year he is listed as a potter in city directories.[34] In 1824 he took out an ad to remind customers that he “still continues to manufacture STONEWARE OF SUPERIOR QUALITY, at the old stand, corner of Pitt and Green Streets.”[35] The ad refers to the old stand or factory belonging to his father, Thomas Morgan, but does not mention his former partner Thomas Amoss.

Stoneware vessels inscribed “Morgan Maker” share the same characteristics as wares signed “Morgan & Amoss,” including vessel form and incised and slipped floral designs. Moreover, the style of writing that appears on these inscribed vessels (see figs. 2–5, 24–26, 28–32) is identical, indicating a clear connection to William H. Morgan.

DAVID PARR AND JAMES BURLAND

The impressed maker’s mark "PARR & BURLAND BALTIMORE” on a small, undecorated jar and a decorated cooler refers to the partnership of David Parr and James Burland (fig. 33). Their pottery was located at Eden and Dulaney Streets. In 1815 the new firm of Parr and Burland, as well as the firms Thomas Amoss and Co. and Myers and Parr, joined to establish a uniform price structure for the sale of their wares.[36] By 1823 the partnership of Parr and Burland appears to have dissolved, and Burland, who was also a grocer, ran the following newspaper ad to sell off a large inventory of stoneware:

25 per cent Discount. STONEWARE. The subscriber having retired from the stoneware business offers for sale 2600 pieces of STONEWARE, of Baltimore manufacture consisting of JUGS, PITCHERS, JARS, MILK AND BUTTER PANS, CHAMBERS, & c. & c. The above deduction will be made from the Baltimore printed prices, on application being made at his grocery store, corner of Eden and Dulaney sts., near Harford Run, where the ware can be examined.

James Burland[37]

After 1822 city directories list David Parr running the operation at Eden and Dulaney Streets on his own. However, another newspaper ad, placed by Parr and Burland in 1828, indicates that the partnership was active at this point, if only temporarily, and lists a factory on Market Street (also known as Baltimore and formerly Dulaney) as well as a warehouse at 64 South Street.[38]

MAULDEN PERINE

A churn incised with the date of manufacture and the address of M. Perine and Company (figs. 34, 35) is extremely rare and can be used to attribute other unmarked wares. In 1840 Maulden Perine built a new factory at West Baltimore (also known as Market) and Schroeder Streets while continuing to operate the factory he had established in 1827 at Lexington and Pine. Perine belonged to a long line of Baltimore potters, including his father, Peter Jr., an uncle Maulden, and his sons Thomas P. and Maulden David. Census records from 1850 detail Perine’s production capabilities the year before his shop made the incised churn. Perine invested $2,500 to operate a business that employed eleven men, paid average monthly wages of $330, and produced $9,000 in stoneware and $2,000 in “clay ware” annually. Other costs included $1,500 for wood, $500 for clay, and $500 for other materials.[39]

HENRY REMMEY

A well-executed pitcher bearing the impressed maker’s mark “H. REMMEY BALTIMORE” (fig. 36) is located in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum. An attractive pattern of incised flowers and leaves along its shoulder is further enhanced by cobalt decoration. Luke Zipp in the 2004 issue of Ceramics in America concludes that wares with this mark were probably made between 1818 and 1821, when Henry Remmey Sr. and his son Henry Jr. worked at Jacob Myers’s Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory. It is possible that this mark could date earlier, however, as Remmey Sr. is associated with William Myers’s ownership of this factory beginning in 1812 and the former’s whereabouts between 1815 and 1818 are uncertain.[40]

Henry Remmey’s entry in the 1820 census offers additional insights into his involvement in Baltimore stoneware manufacture.[41] This enumeration lists eight members of his household: four white males, two white females, one male slave under age fourteen, and a free black male between the ages of fourteen and twenty-five. It also contains a column that records three persons “engaged in Manufactures,” possibly suggesting that one or both of the black males may have been involved in the manufacture of stoneware in some capacity.

ADAM WIPFIELD, FOR M. PERINE AND SIBS

Following the death of Maulden Perine in 1865, subsequent generations continued to carry on the family business as M. Perine and Sons. An extraordinary oversize pitcher with elaborate floral decoration and dated 1870 (fig. 37) was made by Adam Wipfield, a journeyman who is documented working at this factory from 1865 through 1872.[42] In 1879 Wipfield established his own business on Harford Road, eventually partnering with his son John and working as a potter until 1896.[43]

Decorating for Success

Baltimore’s stoneware industry mirrors many emerging ones in the mid-Atlantic and Southern regions that had begun to decorate utilitarian wares as local and regional marketplaces grew increasingly competitive. The city’s factories used distinctive floral and bird designs executed in cobalt to enhance the appearance of utilitarian wares. Many of these patterns are rooted in a Germanic potting tradition and typically are associated with an influx of immigrant potters during the nineteenth century (see fig. 23). Similar but stylistically different floral motifs were also prevalent on contemporaneous stoneware produced in Philadelphia, Alexandria, and the Shenandoah Valley.

Decoration, like stoneware forms, changed over time, making it useful for temporal evaluation (fig. 38) as well as for cautious attributions (see figs. 2, 4, 39). A qualifier is often necessary when attempting to attribute decorative styles to specific factories and individuals. A case in point is a three-petaled flower motif that several Baltimore makers are known to have used, notably Peter Herrmann, M. Perine and Sons, William Prince, and “Myers and Bokee” (see figs. 37, 52, 55). Other shops in the city probably used this characteristic design as well. Furthermore, it was not always the hand of the master potter that decorated stoneware; this task may have been performed by others, such as journeymen, apprentices, and even female workers.[44] In most cases there is no solid evidence to show who decorated utilitarian wares.

TTECHNIQUES

Baltimore stoneware factories used several different decorative techniques to great effect, among them brushed, incised, slip-dipped, slip-trailed, and stenciled. Slip-trailing and incising, which require great skill to execute properly, are perhaps the earliest and certainly the most labor-intensive decorative methods. Slip-dipped and stenciled wares, in use by the mid-nineteenth century, are very rare. Brushed decoration was used extensively up until the end of the century.

Slip-Trailed. Baltimore wares from the early nineteenth century display intricate designs created by trailing thin lines of slip through the nozzle of a slip cup (figs. 40, 41). Characteristic designs include flowers, vines, leaves, wavy lines, swags, and undulating and repeating patterns.

Incised. Incised designs are also found on early examples of Baltimore stoneware (figs. 42, 43). This decorative technique involves the use of a sharp tool to etch designs in the surface of vessels before firing. Cobalt was sometimes added to enhance the effect of this technique.

Slip-Dipped. Dipping stoneware vessels in brown slip ensured that they would be impermeable to liquids and enhanced their exterior surface. Slip glaze is found on bottles made for the grocers and wine dealers Erskine and Eichelberger (fig. 44, left), and for F. Sandkuhler, a brewer of beer (fig. 44, right). Those made for Sandkuhler could very well be a product of M. Perine and Sons, as a surviving daybook from the pottery documents that his brewery regularly ordered beer bottles by the gross.[45]

Stenciled. A storage vessel of about 1851, made for the butter dealers S. Sutton Clayton and James E. Hewes, features large cobalt stenciling on one side (fig. 45) and curving C-scroll vines with graduated leaves on the other (fig. 46). The presence of this decorative motif, lug handles, and the color and texture within its clay body all strongly suggest a Baltimore manufacture. It is somewhat surprising to discover that Baltimore potters might have used stenciling in conjunction with brushed decoration, since stenciled wares are more typical of western Pennsylvania manufacture. Moreover, the fact that stenciling is associated with mass-produced wares made later in the nineteenth century would make this butter crock one of the earliest examples of American stoneware with this type of standardized lettering.[46]

Brushed. Brushed cobalt decoration is the most common type seen on Baltimore stoneware. Factories applied an array of popular floral designs throughout the nineteenth century, even to handles of vessels (figs. 47, 48).

Functional Forms

The range of Baltimore stoneware featured in this study reflects the extensive storage and preservation needs of nineteenth-century consumers. The city’s potters produced the same utilitarian wares as were being produced in other regions: “jugs for holding cane syrup, whiskey, vinegar, and water; churns for making butter and buttermilk; crocks and pitchers for cooling milk; and jars for keeping vegetables, fruit, meat, lard, butter, homemade soap, and also for fermenting wine and liquor.”[47] Cultural analysis of the utilitarian stoneware forms made in Baltimore—and their functional aspects—helps to understand how the materials, construction, and design of Baltimore wares relate to the intended uses of these vessels, as well as the intriguing ways in which they sometimes were later modified.[48]

CHARACTERISTIC JUGS

Jugs made in the second half of the nineteenth century are one of Baltimore’s most distinctive stoneware forms. These vessels have tooled spouts and large, graceful handles applied to rounded shoulders; they were often impressed with typeset merchant advertising and held a wide range of commodities, especially whiskey, wine, and other types of spirits. In figure 49, an unmarked miniature jug and a one-gallon jug held by a man posing in a period photograph share elements characteristic of Baltimore manufacture. Whether this unusual photograph was intended to be an occupational advertisement for a potter or merely captured the excessive consumption of alcohol in the city at the time is open to speculation. With regard to the latter, Baltimore moved to the forefront of the temperance reform movement in 1840 with the creation of the Washington Temperance Society, which met in a city tavern.

MODEL FORMS

The discovery of a copper jug made in Baltimore demonstrates the degree to which one craftsman can influence another; in this case, a coppersmith named Joseph M. Kavanagh went to great lengths to imitate the work of a stoneware potter (fig. 50). Both jugs are similar in form, handles, spouts, and impressed typeset lettering. An advertisement for Kavanagh (fig. 51) promotes his skill in the manufacture of copper jacket kettles, as well as handled pans and buckets.[49] The daybook of Maulden Perine documents several metal artisans, including a brass founder, purchasing stoneware vessels in limited quantities, perhaps for use in their shops.[50] Kavanagh may have chosen to create his own, more durable metal container in an effort to improve on an already successful design.

VERSATILE FORMS

The stoneware pitcher was another popular form made in Baltimore throughout the nineteenth century. The two unmarked examples in figure 52 share general form and decoration yet probably served very different functions. The uncommon pitcher on the left retains an original metal lid that may have been made by a local tinsmith. The hinged lid is secured through two small holes located below the back of the rim, placed there by the potter who made it. The enormous four-gallon pitcher on the right retains a residue of white brine on its interior, indicating that it was once used for pickling rather than pouring.

SECOND-QUALITY GOODS

The frequent imperfections found on nineteenth-century stoneware reflect the challenges and uncertainties associated with operating kilns. Yet the inherent functional value of even imperfect vessels speaks to the needs of users during this period. A badly misshapen four-gallon crock made by Peter Herrmann (fig. 19), for example, was still useful and likely was offered at a reduced price. (The pronounced asymmetrical slump on this example probably occurred when a stacked load shifted during a kiln firing.) Baltimore consumers were provided substantial discounts for this type of stoneware, depending on the extent of the damage incurred.[51]

AESTHETIC REFINEMENTS

As tastes changed it was not uncommon for owners to redecorate outdated and obsolete wares rather than simply discard them. A case in point is an unusual stoneware advertising mug (fig. 53) made for Antonius Meinecke, the proprietor of a saloon in a waterfront neighborhood east of the Basin (what is now Canton). The construction and finish of this mug are of high quality, with thin flaring walls highlighted by simple bands of cobalt under its rim and along its foot, now hidden beneath a layer of gold paint. By the twentieth century the forces of industrialization had supplanted the once-flourishing stoneware craft tradition. Ironically, the Baltimore potter who made this fine mug likely witnessed his talent becoming increasingly obsolete, as mass production fed consumer demands. The artistically inclined person who at some later date added the striking and pleasing pattern of painted daisies not only enhanced the vessel’s appearance but also helped to ensure its survival (fig. 54).

Forms of Marketing

Baltimore potters used several means to market their wares. Regular newspaper advertisements placed in outlying regions, particularly in the South, reflect an active effort to export wares, and wholesale dealings with merchants, tradesmen, and other retail businesses became an increasingly common business practice. Later in the century Maulden Perine and Peter Herrmann dealt primarily in wholesale wares.[52] Perine relied on this type of marketing almost exclusively,[53] selling 90 percent of his wares within the city; he also shipped stoneware, by steamboat, to places as far away as South Carolina.[54] Establishments specializing in china, glass, and queensware were important wholesale clients of many stoneware potters. Some china merchants even operated their own stoneware kilns, making utilitarian items to sell in their retail establishments as well as to offer at wholesale prices. Surviving marked wares illustrate the complexities of marketing stoneware manufactured in Baltimore.

SELF-PROMOTION

While period newspaper advertisements usually reference product lines, they sometimes offer insights on potters and factory production. For instance, in 1820 William H. Morgan and Thomas Amoss, partners in the firm Morgan and Amoss, ran an ad in three different newspapers—in Baltimore, Richmond, and Fredericksburg—that serves to document not only the marketing of wares outside Baltimore but also the purchase of native clays and the challenges involved in providing customers with the highest-quality stoneware:

COME & SEE.

To Dealers in Stone Ware

Those who wish to purchase the above article of a very superior quality, will call on MORGAN & AMOSS, at their factory, corner of Pitt and Green Streets, Old Town, who will (as usual) deliver it safe to any part of the city on terms to suit the times.M. & A. have the satisfaction to inform their old customers, as well as all others who purchase STONEWARE, that they have lately purchased the exclusive privilege of two pits of fine clay, which upon trial has been found to make ware, which excels in beauty any thing of the kind now made, or perhaps ever was made in this country, out of which they intend to manufacture the most of their ware, as long as the pits will hold out.

Some have declined the purchase of this article on account of having so much broken on hands, “which,” they say, “takes away the profit.” Those who have been troubled by this description of stone ware, are informed that this is caused by using materials which are liable to (what we call) air or wind cracks, and all stone ware made of such materials (which we are happily rid of) is subject to this kind of cracking, weeks and months after it is manufactured, which nasty trash, every one ought in justice to himself and the public, to discard from his manufactory as soon as it is discovered to possess such DESTRUCTIVE qualities.

Those who purchase from us may rest assured of being supplied with the very best quality, and will at all times be put up agreeable to the sample shown.—It would always be a satisfaction to us, if country merchants could at all times make it convenient to call at the factory and examine the quality of the ware, whether they intend to purchase at present or not, they will then be able to judge between ours and any other that they have ever seen. Those who cannot call or have not friends in town to do it for them can leave their orders at the following places:—Geo. C. Smith, No. 60 Market street—Keyser & Schaeffer, on the square above Barnum’s (late Gadsby’s)—D. Keyser, Howard st.—James Armstrong, jr. Cheapside—either of whom will pay necessary attention to the same.

NB.—M. & A. do not authorize any stone or earthenware potters to sell ware for them, the public will take due notice thereof.[55]

Baltimore potters also made oversize stoneware vessels that promoted the skills of stoneware potters in a highly visible manner, much like the commercial trade signs that were common throughout the nineteenth century. Two rare examples from Baltimore are known to exist. The first is an enormous straight-sided container made by William Linton, which is decorated with an elaborate floral design and features four lines of impressed typeset lettering advertising his pottery and salesroom at the corner of Lexington and Pine Streets (see fig. 20). The other oversize vessel, made by Adam Wipfield in 1870, reportedly functioned as an advertisement in the window of Bowers Pharmacy at 1001 West Baltimore Street (see fig. 37).[56]

CHINA MERCHANT OPERATIONS

Baltimore has a long history of china merchants hiring skilled potters to manufacture wares that were then sold wholesale or in the merchants’ retail establishments. Important research has been carried out regarding the relationship between Baltimore china merchants and potters, notably archaeological testing at the circa 1838–1845 kiln site of china merchant James Pawley Sr., which recovered a sizable collection of stoneware sherds, kiln furniture, and wasters.[57] In addition, Luke Zipp has conducted research on a stoneware operation owned by various members of the Myers family of china merchants discussed in the 2004 issue of Ceramics in America.[58]

A rare decorated jar marked “MYERS & BOKEE” (fig. 55) documents china merchant Henry Myers’s involvement in stoneware production through a partnership he established with John C. Bokee as early as 1835.[59] In 1839 the firm advertised

China, glass, and queensware, as cheap as the cheapest. The subscribers ask the attention of wholesale and retail purchasers to their well assorted stock of china, glass, and queensware, as they are determined to sell for cash, as new as any house in the city. Purchasers will consult their interest by giving them a call before purchasing elsewhere....[60]

Myers and Bokee continued to market imported wares and glass at 53 Baltimore Street through at least 1840.[61] By 1843 J. C. Bokee ran his own shop at 61 West Pratt Street, suggesting that the partnership had ended.[62]

Another decorated stoneware jar, marked “EARNEST & COWLES” (fig. 56) further illustrates the involvement of Baltimore china merchants in the manufacture of utilitarian wares. George Earnest and Wesley Cowles were partners in a china shop located at 25 and 29 South Calvert Street as early as 1829 and through at least 1852.[63] According to census records for 1850, the firm invested $3,000 in capital, employed three and a half men, paid $120 in monthly wages, and produced $5,000 in stoneware annually. Additional annual costs included $450 for 150 tons of wood, $137 for 100 tons of clay, and $200 for other materials.[64] The two-story brick pottery, measuring 131 feet by 22 feet, fronted the west side of Wilkes Street between Washington and Chester Streets.[65]

Overall, the city’s china merchants were surprisingly organized in protecting their interests from competitors. In 1847 a group of them submitted a petition to the Second Branch of the City Council in opposition to the unregulated selling of wares in the city’s streets:

We the undersigned, dealers in china, glass, and queensware, would respectfully call your attention, to the fact, that large quantities of goods in our line of business, are sold daily, in the streets, in the immediate vicinity of the several markets, on the respective market days of each, to the manifest injury of the undersigned, who transact a regular business, and pay liscence, taxes and c., for the privilege. We therefore; respectfully request, your honourable body, to take such measures as shall clear the streets, of all persons engaged in selling goods in the said line of business; if such, in your judgment, should appear just and expedient, and your petitioners will ever pray and c.[66]

MERCHANT ADVERTISING WARES

Locally made stoneware advertising vessels with the impressed names and addresses of Baltimore merchants provide ample evidence of the flourishing commercial trade that existed in the city. The use of stoneware for advertising was especially prevalent in the second half of the nineteenth century, and a wide range of products was sold regularly in market areas, liquor stores, butter depots, wharves, grocery stores, and many other outlets. A small sample of these wares illustrates these marketing venues and also reflects the degree to which the city’s potters served the needs of local businesses.

Stoneware advertising was particularly well suited to merchants dealing in spirits, tonics, and cider. For example, Baltimore potters made a convenient quart-size jug for wine and liquor dealers such as Charles Siebert and Hammel & Boneau Importers, who set up shop in Centre Market, one of the city’s largest market areas, north of the Baltimore Basin (fig. 57). By contrast, Dr. Benjamin Bates, a confectioner who specialized in tonic beers, required a much larger cooler to hold the wine cider he also sold at Centre Market (fig. 58, left). An identical cooler made for George and William Meeter, brothers who operated a liquor store in the city, suggests that they dealt with the same local stoneware factory as did Bates (fig. 58, right).

Not surprisingly, the city’s potters made storage vessels for merchants dealing in various foodstuffs. A highly decorated storage crock with cobalt flowers provided an attractive advertisement for S. Clayton and Sons, who operated butter depots within the city (fig. 59). Small stoneware jugs were also made to hold name brand items from Baltimore, such as Numsen’s Yacht Club Vinegar (fig. 60). The need for stoneware containers eventually disappeared once metal and glass containers, more suitable for mass production, could be made more cheaply and efficiently.

Stoneware vessels also advertised merchants situated along waterways, a tangible reminder of Baltimore when it was still an active seaport. Ship chandlers and merchants such as George H. Edgar (fig. 61, left) and Hugh Bolton (fig. 62) sold stoneware to the many ships that docked along wharves in the Baltimore Basin, while a jug from H. Steffens (fig. 61, right) was available in Fells Point, to the east, along the North West Branch of the Patapsco River. Hugh Bolton, a merchant who specialized in glass, oil, and paints, is known to have placed orders with potter Maulden Perine for dozens of stoneware jugs.[67] Whether the stoneware jugs Bolton sold contained liquor or other commodities is not known. However, a rare billhead receipt from Hugh Bolton & Co. (fig. 63) records the sale of one gallon of machine oil.

Grocery stores were another ready outlet for the sale of items requiring stoneware containers. For instance, Richard Stumpf sold his “Iron & Wild Cherry Tonic, the Great Family Medicine” at his grocery store on Baltimore Street, north of Fells Point (fig. 64). This excellent example of nineteenth-century advertising necessitated five lines of impressed typeset lettering. Baltimore potters distributed advertising vessels to merchants in Maryland, areas of Pennsylvania, and the South, including Benjamin S. Hooper, a dealer in groceries and liquors in Farmville, Virginia (fig. 65). Hooper also served as a Confederate veteran and a member of the United States House of Representatives.

The Mechanization of a Craft Tradition

Industrialization transformed stoneware production, as mechanization and mass production gradually replaced skilled potters with a semiskilled workforce. Stoneware that was ovoid in shape in the first half of the nineteenth century typically became straight-sided, and an extruded process replaced the hand-pulling of handles. Craft traditions were cast aside with the advent of mechanized pull-down molds—called jiggers and pressed and slip-cast molds—which standardized production and increased the efficiency of workers. Furthermore, the city’s utilitarian potters were beset by a shifting marketplace increasingly dominated by firms involved in the automation of metal cans and glass canning jars. By 1883 Baltimore alone had at least twenty-eight can manufacturers, and the city’s southeast section became known as “Cannery Row” for its concentration of companies specializing in can-making and can-making machinery.[68]

A storage jar made by a stoneware factory in western Pennsylvania for the Baltimore firm of D. F. Haynes and Co. (fig. 66) underscores the highly competitive nature of stoneware production toward the end of the nineteenth century. This jar was probably made for the crockery jobbing house at 347 West Baltimore Street, which Haynes established in 1879. In 1882 he purchased the Chesapeake Pottery on Nicholson and Decatur Streets, located in Locust Point along the waterfront southeast of the Basin.[69] A rare view of the plant, which produced decorated majolica and refined wares, is seen on a postcard dated 1905 (fig. 67). By that time the venerable pottery had gone through several owners: David F. Haynes, Edwin Bennett, a partnership between D. F. Haynes and Bennett’s son E. Huston, and a partnership between D. F. Haynes and his son Frank.

Several rare documents from M. Perine and Sons further illuminate the radical changes that had taken place in Baltimore’s stoneware industry by the late nineteenth century. Although many stoneware operations closed their doors, M. Perine and Sons implemented mechanization and adopted new product lines in response to a changing marketplace, consumer demand, overwhelming competition, and new industries.

A letter written in 1895 to a Virginia customer documents the firm’s outsourcing of stoneware production to an Ohio factory while retaining a limited production line of utilitarian earthenwares:

In reply to yours of May 1st we enclose [a] Price List of Stone and Earthenware with net prices and discounts marked. We can ship Stoneware in Lots from our Factory at White Cottage, Ohio, and Earthenware from Baltimore, Md. All Ware F.O.B. our Factory. Earthenware can be shipped in Packages. Stoneware in Lots of 6000 Sale and over. Awaiting reply we remain, Yours truly, M. Perine & Sons.[70]

A price list enclosed with the letter provided detailed information on the firm’s two separate product lines (fig. 68). A penciled notation on the price list describes Ohio stoneware as “white-glazed,” referring to a Bristol glaze first developed in England that by the late nineteenth century was used extensively by industrialized potteries throughout America.[71]

Another rare letter of inquiry sent in 1897 by M. Perine and Sons to a pottery supplier in Canton, Ohio, further documents the mechanization of earthenwares produced in the Baltimore factory: “Gentlemen, Enclose please find Check for Bill for Rib Plates. Please send us a list of your make of Jiggers, with price including Rings and Pull-down. Yours truly, M. Perine & Sons.”[72]

In light of the Perine correspondence, the discovery of two unmarked stoneware vessels with distinctive brushed cobalt Baltimore motifs over Bristol white-glaze raises intriguing questions about their origin. The first, a storage jar (fig. 69), left), displays a familiar three-petaled design seen almost exclusively on earlier Baltimore-made salt-glazed stoneware. The appearance of this motif on white-glazed stoneware suggests that the city’s potters may have experimented with or briefly used this type of glaze or that the piece was made at another regional pottery.

In fact, a Philadelphia attribution is possible for another unusual white-glazed vessel, a pitcher (fig. 70) with two floral sprays identical to the type used to decorate the oversize container made by William Linton (see fig. 20). Thomas Haig’s Northern Liberty Factory in Philadelphia is known to have produced white-glazed stoneware and used this two-spray decoration on marked wares.[73] How and why a factory in another city adopted this distinctive and earlier Baltimore motif warrants further study.

Summary

This broad overview, which has documented a wide range of marked utilitarian stoneware vessels associated with Baltimore’s nineteenth-century stoneware industry, has also illustrated how these wares reflect various technological, economic, and cultural changes. An analysis of maker’s marks and decoration provides new insights on production and demonstrates the utility and limitations of using them to attribute unmarked wares. Baltimore’s characteristic stoneware forms reveal how potters attempted to meet the demands of consumers, some of whom later adapted these functional wares to suit their own needs. Further, marked wares reflect different marketing practices and the wholesale distribution of wares within the city and outlying regions. Finally, mechanization, new product lines, and the inroads of outside competitors highlight the manner in which industrialization eclipsed the city’s craft-making traditions by the end of the nineteenth century.

While this study is not intended to be representative of an entire stoneware industry, it does attempt to identify, compare, attribute, and construct general typologies for Baltimore wares. These vessels can help bring the past into focus, shedding light on the city’s forgotten working-class artisans and providing new avenues for historical interpretation. It is hoped that these findings will prove useful to scholars in related fields and continue a dialogue that will spur additional research on this subject.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to extend special thanks to Rob Hunter for the opportunity to present this research, Gavin Ashworth for his remarkable photographic skills, and Mary Gladue for her exceptional editorial assistance. I am very grateful for the scholarly guidance and insights of my doctoral committee: Professors Mary Corbin Sies, Nancy Struna, and Paul Shackel of the University of Maryland College Park; Dr. Al Luckenbach, Director of the Lost Towns Project; and Dr. Greg Stiverson, Executive Director of the Historic Annapolis Foundation. I am also appreciative of help from Baltimore City Archivist Rebecca Gunby, historians Ethel Story White and Jane McWilliams, and, especially, my wife, Joanna.

Native Baltimore clays provided exceptionally suitable material for the manufacture of stoneware. Clays from this area even supplied Alexandria potter B. C. Milburn; see Barbara H. Magid, “An Archaeological Perspective on Alexandria’s Pottery Tradition,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 21, no. 2 (1995): 72.

Susan Myers’s landmark Handcraft to Industry (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980) documents the effect of industrialization on the Philadelphia ceramics industry.

John N. Pearce, “Early Baltimore Potters and Their Wares, 1763–1850” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1959).

Susan H. Myers, “Marketing American Pottery: Maulden Perine in Baltimore,” Winterthur Portfolio 19, no. 1 (spring 1984): 51–66.

Luke Zipp, “Henry Remmey & Son, Late of New York: A Rediscovery of a Master Potter’s Lost Years,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: Chipstone Foundation in association with the University Press of New England, 2004), pp. 143–56.

Suzanne L. Sanders and Martha R. Williams, Archeological Mitigation of the J. S. Berry Brick Mill (18bc89) and Pawley Stoneware Kiln (18bc88), at the Proposed Ravens Stadium, Baltimore, Maryland (Frederick, Md.: R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, February 1998).

Ibid., p. 14.

This teapot was among an assemblage of dozens of redware and stoneware vessels that archaeologists with the National Park Service recovered from a burned, pre–Civil War site, possibly a store or a tavern, in City Point, Virginia, at the confluence of the James and Appomattox Rivers.

A stoneware milk pan incised “Morgan Maker Pitt Street Baltimore 1825” establishes that William H. Morgan used this maker’s mark as late as 1825. This vessel is illustrated in Carmen A. Guappone and Marie A. Guappone, America’s Cobalt Decorated Stoneware (McClellandtown, Pa.: Guappone Publishers, 1992), p. 92.

An identical map (#348w5) is in the collections of the Maryland State Archives, whose website states: “The source of this map has not yet been found. However, there was a W. Williams who was an engraver for the firm of S. A. Mitchell, prominent atlas publisher of the mid-19th century. It is quite likely that the publisher of this map is the same person.” www.mdarchives.state.md.us/msa/speccol/1399/reports/html/348w5.html (accessed March 30, 2005).

1837 is the last year Morgan appears in city directories as a potter; Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1837–38 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1837), p. 235. He might have manufactured stoneware beyond this date, however, because in 1839 he received the approval of the mayor and city council to remove his kiln located at the northeast corner of Pitt and Exeter (Green) Streets and relocate it to another part of his lot. City Council Records #1333, 1839, Baltimore City Archives.

Records show that in November 1794 and 1795 Morgan bought two parcels of land in proximity to Pitt and Green Streets; Baltimore County Deeds, 1794, Liber W. G. #R.R., folios 81–82, and 1795, Liber W.G. #S.S., folios 403–404. It is possible his factory was operational at some point in 1795, although he does not appear in city directories as a potter until 1796. See Baltimore Town and Fell’s Point Directory for 1796 (Baltimore, Md.: William Thompson and James L. Walker; Printed by Pechin and Co.), p. 56.

City Council Records #153, 1798, Baltimore City Archives.

National Archives Microfilm Publications, 1829–1891 Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Baltimore, Microcopy 255, Roll #4, September 16, 1844.

Baltimore City Criminal Court, Naturalization Records, 1851–1854, 11, cr75, 546-1, p. 55.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1855–56 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1855), p. 154; Baltimore City Directory for 1859–60 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Sherwood and Company, 1859), p. 178; Woods Baltimore City Directory for 1879 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by John W. Woods, 1879), p. 1049.

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1888 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Nichols, Killam, and Moffitt, 1888), p. 519; R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1889 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Nichols, Killam, and Moffitt, 1889), p. 537.

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1894 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Nichols, Killam, and Moffitt), p. 636; R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1896 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Evening News Publishing Company, 1896), p. 1994.

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1899 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Thomas and Evans, 1899), p. 674.

Original Schedules for Maryland, Seventh Census of the U.S., 1850, Schedule 5, Baltimore City, Ward 19, p. 279. William Linton is recorded as thirty-five years old and born in England.

City Council Records #1029, 1849, rg 16, s1, Box 85, Baltimore City Archives.

Baltimore Wholesale Business Directory and Business Circular for 1853 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Sherwood and Co., 1853), p. 133.

Woods Baltimore City Directory for 1867–68 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by John W. Woods, 1867), p. 695.

Baltimore County Register of Wills, Indentures, 1808–1811, October 10, 1809, p. 257.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1831 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1831), p. 263; Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1833 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1833), p. 131.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1833, p. 131; Matchett’s Directory for 1840 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1840–41), p. 257.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1840, p. 257.

American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, January 16, 1812, p. 3.

Ibid., March 15, 1815, p. 3.

Ibid., March 30, 1819, p. 3.

The various partnerships between these family members with similar names understandably has resulted in confusion as well as erroneous attributions.

1820 Census of Manufactures, Virginia, Henrico County.

Henrico County, Virginia, Will Book No. 6, 1822–1827, August 7, 1822, p. 137.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1827 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1827), p. 190.

American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, October 6, 1824, p. 1.

Ibid., October 21, 1815, p. 3.

Ibid., December 15, 1823, p. 3.

Ibid., April 24, 1828, p. 1.

Original Schedules for Maryland, Seventh Census of the U.S., 1850, Schedule 5, Products of Industry, Baltimore City, Ward 18.

Zipp, “Henry Remmey & Son, Late of New York,” pp. 144–45.

Population Schedules of the Fourth Census of the U.S., 1820, p. 97. Henry Remmey is listed as “Henry Remmy.”

Perine family workbooks, 1859–1872 (microfilm), MS 654, Maryland Historical Society, 1865, p. 111, and 1872, p. 281. (ms 654 comprises a special collection of business records relating to the Perine family that span the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.)

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1896 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Evening News Publishing Company), p. 1671.

Laura Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Boston: Archon Books, 1969), p. 32.

Perine family daybook, 1882–1885 (microfilm), ms 654, Maryland Historical Society, 1884, p. 120, and 1885, p. 225.

Phil Schaltenbrand, Big Ware Turners: The History and Manufacture of Pennsylvania Stoneware, 1720–1920 (Bentleyville, Pa.: Westerwald Publishing, 2002), pp. 84–85. According to Schaltenbrand, stenciled decoration grew in popularity after 1875.

John Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1995), p. 15.

E. McClung Fleming, “Artifact Study: A Proposed Model,” Winterthur Portfolio 9 (1974): 153–73.

R. L. Polk and Co.’s Baltimore City Directory for 1895 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Nichols, Killam, and Moffitt, 1895), p. 1682.

Myers, “Marketing American Pottery,” p. 61.

Ibid., p. 65. Perine offered discounts of between 7 and 35 percent of wholesale price for second-quality goods.

Woods Baltimore City Directory for 1865–66 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by John W. Woods, 1865), p. 193. Herrmann refers to himself as a manufacturer and wholesale dealer in all kinds of stoneware.

Myers, “Marketing American Pottery,” p. 52.

Ibid., p. 53.

American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, August 25, 1820, p. 3; Richmond Enquirer, October 10, 1820, p. 3;Virginia Herald, September 6, 1820, p. 3. The same advertisement ran in all three newspapers.

“Maryland Antiques Show and Sale” [booklet] (Baltimore: Museum and Library of Maryland History/Maryland Historical Society, 1986), p. 86.

Sanders and Williams, Archeological Mitigation, p. 50.

Zipp, “Henry Remmey & Son, Late of New York,” pp. 143–56.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1835 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1835), p. 25.

Baltimore Clipper, October 16, 1839.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1840, p. 68.

Craig’s Business Directory and Baltimore Almanac for 1843 (Baltimore, Md.: Daniel H. Craig, 1843), p. 59.

Matchett’s Baltimore Directory for 1829 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1829), p. 96; Baltimore Wholesale Business Directory and Business Circular for the Year 1852 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by Daniel H. Craig, 1852), p. 93.

Original Schedules for Maryland, Seventh Census of the U.S., 1850, Schedule 5, Products of Industry, Baltimore City, Ward 1. “Three and a half men” refers to the average number of workers employed by the pottery in one year; Carroll D. Wright, History and Growth of the United States Census (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900), p. 313.

In 1843 the Baltimore Equitable Society insured the firm; Earnest’s seven-year plan included $1,750 of coverage for the building and $250 worth of fixtures. Baltimore Equitable Society Record of Policies, ms 3020, Maryland Historical Society, 1843, p. 5.

City Council Records #493, 1847, rg 16, s1, Box 79, Baltimore City Archives. This petition contains the following signatures: H. J. and C. J. Baker; Hammond and Porter; J. R. and F. W. Marston; J. C. Bokee and Co.; David Ball; D. Preston Parr; W. Cowles; James Pawley Jr.; Henry Bayley; H. P. Black; C. Levering and J. Clark; Thomas H. Stephens; Smith and Sharkey; John Wonderly; and Jacob Myers. Although William F. Bokee did not sign the petition—owing to a “private objection”—he wrote at the bottom of the document that he was “opposed to persons having the privilege of selling goods in the streets.”

Perine family daybook, 1855–1859 (microfilm), ms 654, Maryland Historical Society, 1857, p. 190, and 1859, p. 416

Woods Baltimore City Directory for 1883 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by John W. Woods), p. 1137; Dennis M. Zembala, ed., Baltimore: Industrial Gateway on the Chesapeake Bay (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Industry), pp. 24–25.

Nancy R. Fitzpatrick, “The Chesapeake Pottery Company,” Maryland Historical Magazine 52, no. 1 (1957): 65–66.

M. Perine and Sons to T. J. Elsorn, May 5, 1895 (private collection).

Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stonewares: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1981), p. 210.

M. Perine and Sons to the Barnet Company, June 18, 1897 (private collection).

On February 19, 2005, Cottone Auctions, Mt. Morris, New York, sold a rare stoneware poultry feeder impressed “Thomas Haig 975 2nd S., Phila.” that was decorated with the identical spray motif seen in figures 20 and 70.