Chest attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1660–1680. Oak and chestnut with pine and white cedar. H. 34 1/4", W. 52 3/16", D. 21 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest may be by John Savell. It appears to be one generation later than the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2 and the chest illustrated in fig. 9.

Fragment of a cupboard attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1640-1670. Oak. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cupboard and the chest illustrated in fig. 9 probably represent the work of William Savell, Sr.

Stool attributed to the Savell Shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1640–1680. Oak. H. 21", W. 18", D. 11". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909). (10.125.330) Photograph, all rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Detail of two pegs from the door frame of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

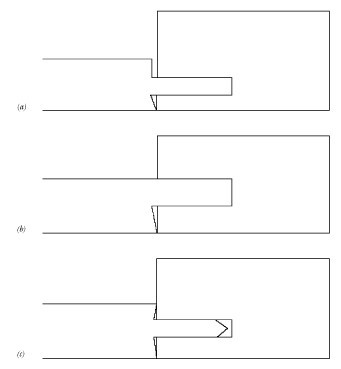

Diagram of (a) typical seventeenth-century New England mortise-and-tenon joint, (b) barefaced mortise-and-tenon joint, (c) Savell shop mortise-and-tenon joint. (Drawing, Peter Follansbee; art work, Wynne Patterson.)

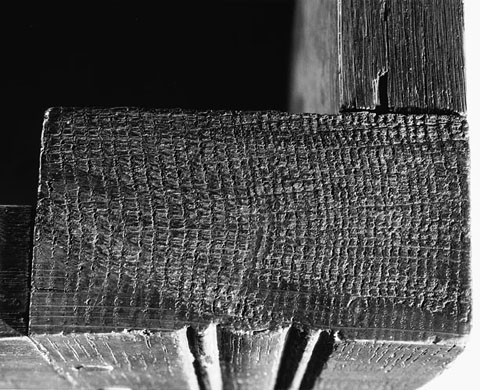

Detail of a mortise-and-tenon joint on the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1640–1670. Oak with pine. H. 20 3/8", W. 47 1/8", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, Greenwood Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest and the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2 probably represent the work of William Savell, Sr.

Detail of the hatchet marks on the inner face of the front rail of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2.

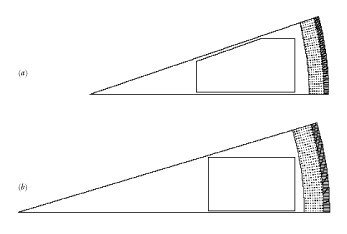

Approximate 1/2-scale drawing of (a) Plymoth Colony pentagonal stile and the billet it is riven from; (b) Savell shop rectangular stile and the larger billet required to produce it. (Drawing, Peter Follansbee; art work, Wynne Patterson.)

Detail of the layout lines of a mortise-and-tenon joint on the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The height of the mortise is indicated by the upper scribe line.

Detail of a door frame mortise and tenon on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The scribe lines from the mortise gauge are visible on the mortise member.

Detail of the board-and-frame construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hole cut by a piercer on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the door panel of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although a number of hands were involved in the carving of Savell shop pieces, there was virtually no attempt to try anything new.

Detail of a carved panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a carved panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a carved panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 20. The carving is less competent than that of figs. 16–18.

Chest attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Oak and chestnut with pine. H. 33 1/2", W. 56", D. 21 7/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. Gift of Charles Hitchock Tyler 32.270.)

Chest attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1660–1680. Oak with pine and cedar. H. 22 3/8" (without lid), W. 49 3/8" (case), D. 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.) This chest may be by John Savell.

Chest attributed to the Savell shop, Braintree, Massachusetts, 1660–1680. Oak with pine. H. 24 9/16", W. 51 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Dan Gair.)

Detail showing the floor framing of (a) the chest illustrated in fig. 1 (interior) and (b) the chest illustrated in fig. 22 (exterior). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth and Dan Gair.)

Detail showing the floor framing of (a) the chest illustrated in fig. 1 (interior) and (b) the chest illustrated in fig. 22 (exterior). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth and Dan Gair.)

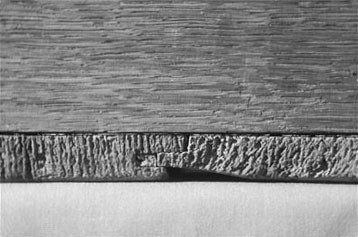

Detail of the modified tongue-and-groove joint used on the floorboards and the bottom of the drawer of the chest illustrated in fig. 1. The bevel on the underside is slightly concave.

Detail of the construction of the rear frame of the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The joiner slid the panel into the frame from below. See also fig. 23b.

Detail of the drawer construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 1. All of the Savell shop drawers are “side hung” and have one large dovetail nailed through the side. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

One of the most sophisticated joinery traditions in seventeenth-century New England flourished in Braintree, Massachusetts. Unlike most New England towns, Braintree was settled during the early seventeenth century by colonists from Boston rather than by a cohesive group of English immigrants. In 1634, the Massachusetts court ordered “that Boston shall have convenient inlargement att Mount Wooliston.” This section of Suffolk County, named for a short-lived expedition by Captain Richard Wollaston in 1624, became known as Braintree.[1]

The earliest references to the woodworking trades in Braintree are deeds involving sawyers Samuel Allen and William Penn during the late 1650s. Wood was an extremely important commodity in early New England. In 1646, the town officials approved:

A grant . . . that every man that is an inhabitant of the Towne shall have Liberty to take any timber off the Common for any use in the Towne [provided] . . . they make not sale of it out of the Towne and in case any shall make sale of it out of the Towne either in boards or bolts or any other wayes whole or sawne they shall pay for every tunne of timber five shillings a tunne to the Town.[2]

Surviving records suggest that the most active families of woodworkers were the Belchers and Savells. Gregory Belcher (b. 1606) settled in Braintree in 1639 and remained there until his death in 1674. He and his sons, Moses (b. 1635) and Samuel (b. 1637), were carpenters, as were Samuel’s son and grandson, both named Gregory. Moses Belcher’s inventory listed expensive furniture, but none of his possessions indicate that he was a joiner. It is, however, quite likely that he was both a furniture maker and a carpenter.[3]

The Savells are the most plausible makers of the furniture discussed in this article. William Savell, Sr., apparently immigrated to New England from Saffron Walden, Essex, England (probably during the early to mid-1630s), and married Hannah Tidd before settling in Braintree after 1639. Her father John was a tailor in Charlestown and, later, Woburn, Massachusetts. Savell remarried twice and had six children altogether. The names of his earliest apprentices are not known, but he probably had several before his son John (b. 1642) began his training.[4]

Savell never held any town position, and there is no record of him receiving a grant or being made a freeman; however, he owned a considerable amount of property when he died in 1669. The total value of his estate was £798.17, and his inventory listed a “house and barn & a bitt of meadow” valued at £90, “John’s house shop barn & land” valued at £120, “Tables stooles chayres chests & wooden ware” valued at £8.4, and “Cart wheels plow chaynes with joiners stuff [a reference to oak] & ceder boults” valued at £19.3.6. In his will, dated February 1668, William Sr. left John “the whole House & barn & shop & tooles, stuffe as Timber pertaining to his trade” and instructed that his “sonn William . . . live as an Apprentice with . . . John Savel . . . until hee bee 21.” An article of agreement attached to the will also specified that his wife, Sarah (Mullins Gannett), receive the “whole estate. . . she brought to [her husband] for her own use & to dispose of forever with a chest with drawers & a Cubbert.”[5]

John Savell was made a freeman in Woburn, Massachusetts, in 1684, but he apparently remained in Braintree all his life. Town records refer to the death of “John Savil Joyner” on November 19, 1687. Few references to trades occur in these records, suggesting that John was well regarded in his profession.[6]

William, Jr., was born in 1652 and apprenticed with his brother, John. The only reference to his work is a 7s payment by the town for “dimblebees cofin” in December 1694. William died on February 1, 1699/1700, possessed of “a green carpitt & covers for chairs” valued at £1.8, “a douzen painted chair & a sealskin trunk” valued at £1.18, “a wainscott chest and a box” valued at £1.1, “a square table a wainscott chest and a bedstead” valued at £2.12, tools valued at £2.10, and “timber and weare begun” valued at £3.[7]

Another joiner who was part of the Savell shop tradition is Joseph Allen (1672–1727). He probably trained with William, Jr., before marrying his master’s niece, Abigail, in 1701. Allen’s estate included “3 chists and one box,” two axes, a hand saw, and “joyner tools.”[8]

The furniture attributed to the Savell shop consists of ten joined chests, a fragment of a joined cupboard, three boxes, and a stool (see figs. 1–4, 9, 20, 21). All are distinguished by their fastidious stock preparation and meticulous joinery. The case pieces also have beautifully executed relief carving that features arches, palmettes, lunettes, and guilloches. The carving is extremely precise, and the designs vary little from piece to piece. The chests and cupboard are further ornamented with crease moldings, and at least three of the pieces have remnants of original paint.[9]

Furniture historian Henry Wood Erving attributed these pieces to Windham County, Connecticut; however; the provenance of two of the chests strongly suggests that they originated in Braintree. One (fig. 1) originally belonged to John (1630–1716) and Ruth (Alden) (1634–1674) Bass, who married in Braintree on February 3, 1657. John was born in Saffron Walden and immigrated with his parents, Samuel and Anne Bass, about 1633. Ruth Alden was the daughter of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins of Plymouth and Duxbury. Like the other chests in the group, this example is constructed of riven (split) and hewn stock. The frame and panels are oak, the original four-board lid is chestnut, and the floorboards are cedar—a wood listed in the inventory of William Savell, Sr.[10]

A similar chest (fig. 21) has an early recovery history in Braintree. Tradition maintains that Charles Hibbard French (1877–1919) received it as a wedding present from an uncle who found the chest in a barn there. The French family was in Braintree by 1640, when John French received a land grant near the Monatiquot River.[11]

The Art of Joinery

A basic knowledge of conventional seventeenth-century stock preparation and joinery techniques is essential for understanding the more distinctive practices utilized by the makers of this group. The most important technique for constructing joined furniture was the drawbored mortise-and-tenon. A fragment of a wall cupboard attributed to the Savell shop (fig. 2) has clear evidence of drawboring. The joiner drove the pegs through holes that were offset intentionally (the hole in the tenon is closer to the shoulder than is the hole in the mortise), which made the joints draw together tightly (fig. 5). The amount of offset required for drawboring was minimal. Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (1678) recommended a difference of “about the thickness of a shilling.” This process also caused the pegs to kink like the ones illustrated in figure 6.[12]

All seventeenth-century New England joiners utilized drawboring, but few were as meticulous as the tradesmen in this shop. Most joiners undercut the front shoulders of their tenons very slightly and cut the rear shoulders on or just inside the scribed layout line (fig. 7a). As a result, their joints fit tightly on the front of the piece of furniture, but the rear shoulders of their tenons fail to make contact with the mortised edge of the frame. Some New England joiners constructed their furniture with “barefaced” tenons, which have no rear shoulder at all (fig. 7b); however, the survival of numerous seventeenth-century case pieces built with joints that appear substandard to modern observers is testimony to the strength of drawboring. These joints were based on the use of green wood. Although the stiles distorted as they dried, the rear shoulders of the tenons were out of the way, or omitted altogether, so that the stiles could not press against the inside shoulder and shove the tenon out of the joint. By contrast, the Savell joiners took the time and trouble to square their stock, plane it clean and even, and cut two-shouldered tenons that fit tightly against the entire mortised surface (figs. 7c, 8). This standard of precise workmanship was instilled during their training, which must have been rigid given the consistent stock preparation, joinery, and carving of the furniture in this group.[13]

Most stock for seventeenth-century New England furniture was riven from green or unseasoned logs. Riving was an extremely fast, labor-efficient method of extracting wood from a log. One man could reduce a log into rough stock quite easily, whereas two were needed for sawing. This factor was important in seventeenth-century New England where labor was in short supply. In addition, riving allowed the artisan to see each piece as it came from the log, giving him more control over the selection of the wood.

All of the pieces attributed to the Savell shop combine riven and sawn stock. The joined chests typically have a sawn pine panel in the rear, and several examples have sawn floorboards and drawer bottoms. The board chest with joined front illustrated in figure 9 is extremely unusual because its end boards are mill-sawn oak. A 1661 deed between George Ruggles and his son, John, referred to “Woodland . . . within a mile or thereabouts of the Saw mill of or in the said Town of Braintree.” The occurrence of mill-sawn oak in seventeenth-century New England furniture is very rare.[14]

For optimum results, the joiner rived his stock shortly after felling a tree. Not only did green wood split more easily than dry wood, but reducing the log into more manageable sections made transporting it to the shop a simpler task. To make his initial splits, the joiner used a “beetle” (a large wooden mallet reinforced with iron rings to prevent the head from splitting) to drive in large iron wedges. As the sections of the log became more manageable, he used a froe (a tool with a flat blade and wooden handle) and a maul (a heavy wooden club) to rive out his stock quickly. After positioning the froe along the middle of the stock, he struck the back of the blade, burying the tool into the wood. At this point, he set the maul aside and pulled the handle to and fro. This levering action lengthened the split in the wood. The joiner could partially control the direction of the split by exerting pressure on the lower half of the breach while levering the froe. Therefore, a piece could sometimes be saved, even though the split began going astray.[15]

The joiner positioned his splits so that the radial surface of the log would become the working face of each piece. The working face was the reference for all stock dimensioning and layout, so it had to be flat and true. Because of its greater dimensional stability, the radial plane was less susceptible to distortion from moisture loss than the tangential (or growth ring) plane. The radial surface also planed and carved more easily than did the tangential surface.[16]

Most seventeenth-century woodworkers rived their stock slightly oversized, then dressed it with a joiner’s hatchet (a small version of a broadaxe). Using short, controlled strokes, a skilled tradesman could produce accurate, clean surfaces; however, the main function of the tool was gross removal of waste. The joiner used the hatchet and froe to bring the work piece to near-finished dimensions as quickly as possible, thereby reducing the amount of planing. The inner face of the front rail of the cupboard (fig. 10) has hatchet marks left from the hewing process. Here, the joiner neglected to plane the marks away because this surface is hidden from view.[17]

Like the splitting process, planing involved a progression from coarser to finer tools. The joiner used a “fore” plane (a plane with a convex blade and a wide throat for taking a heavy shaving) to remove any natural deviations in the stock, then he removed the resulting furrows with a smooth plane. If the riven stock was clear enough, he could omit the first step and go straight to the smooth plane. Unlike many New England joiners, the tradesmen in the Savell shop planed the front stiles of their case pieces to a rectangular cross-section rather than to a polygonal one (figs. 8, 11). The former process involved more time and labor.[18]

After preparing the stock, the joiner laid out his work with a square and an awl. He used a mortise gauge to scribe the thickness of the mortise-and-tenon joints. The incised lines left from these tools often extend beyond the edges of the mortises and tenons, enabling us to measure the joints accurately (figs. 12, 13). This information is helpful in linking related pieces together and in making distinctions between the individual members of one shop tradition. The furniture attributed to the Savell shop also has alignment marks—triangles and arrows—on the inside faces of the stock.[19]

Conventional shouldered tenons could be cut very quickly. The saw cut that defined the shoulder was the most critical (see figs. 7 a–c). If the stock was straight-grained, the joiner simply split the cheeks off the tenon using a wide chisel or a small cleaver. Alternately, he sawed them down to the shoulder. If the tenon was too thick, the joiner pared the cheeks with a wide chisel. Although some seventeenth-century tenons are flat-ended, those of the cupboard door frame are pointed to allow them to seat in the torn fibers in the bottom of the mortise (fig. 13).[20]

To chop the mortises, the joiner used a mallet and a mortise chisel—a deep-bladed chisel made to withstand heavy blows and to function as a lever for prying out the waste. Often the ends of the mortises were crushed by the levering action. The joiner could work aggressively because green wood cut more easily than did drier timber.

Although it was advantageous to fabricate certain parts of the chest from green wood, during assembly some components needed to be drier than others. Pegs had to be bone dry. If they shrank from moisture loss after assembly, the joints could fail. The tenons needed to be dry enough to resist the pegs being driven into them; otherwise, the peg would deform the tenon instead of drawing it into the mortise. Chest panels and floorboards also needed drying. If a joiner installed the panels wet, subsequent shrinkage would cause them to slip from side to side. Likewise, excessive shrinkage across the width of floorboards would cause gaps. By contrast, the moisture content of the stiles had no effect on the joint.

Generally, the sizes of the parts of a joined object conform to their priority in the drying scheme. Pegs, which need to be the driest, were the smallest in cross-section and, therefore, dried very quickly. Tenons, which were typically about 5/16" in thickness, also dried quickly owing to their dimensions and the fact that wood loses moisture more rapidly through the end grain.[21]

Savell Shop Joinery

Two of the pieces attributed to the Savell shop have structural features that are rare in New England. The cupboard and chest illustrated in figures 2 and 9 have joined fronts whose stiles are rabbeted to the board sides and attached with three, 3/8"-square wooden pegs at each side (fig. 14). Seventeenth-century New England furniture with joined fronts and board cases is extremely rare. The joiner used a piercer (a fluted reaming bit with a lancet point) to bore the holes for the pegs. The counterclockwise direction of the boring is indicated by the pattern of the torn fibers in the hole. Piercers do not cut end grain as well as long grain. As the bit made the transition from the long grain to the end grain, it dug in and left cusps at diagonally opposite “corners” of the hole (fig. 15). All of the smaller peg holes on the Savell shop pieces were bored clockwise. The best explanation for the counterclockwise boring of the larger peg holes is that the 3/8" piercer had one defective lip, and was simply used the other way. The compression of the fibers around the holes reveals that the wood had a high moisture content when the joiner drove in the square pegs. Drier wood is less compressible and would have split long before deforming to this degree.[22]

The joined fronts and board cases of the cupboard and chest provide another link to William Savell, Sr. Chests from Saffron Walden, his probable birthplace, feature this type of construction but have different decoration. A more detailed study of the construction of Saffron Walden chests would be necessary, however, to establish a definitive connection to the Braintree group.[23]

The cupboard and chest share other features that suggest they are by the same hand. Their carving (figs. 16, 17) is more assured, more modeled, and more elaborate than that of the fully joined chests in the group (see figs. 1, 20). Although the latter have essentially the same design elements (figs. 18, 19), the execution of the carving is somewhat “mechanical.” Presumably, the better carving is that of the shop master, who probably trained in England. The narrow panels flanking the door on the cupboard and the front panels on the chest are concave (figs. 2, 17). The carver probably hollowed them to heighten the illusion of depth in his relief work. This feature may have been an option, since some of the chests in the group have flat panels (figs. 1, 18–20).

Although the chests attributed to the Savell shop can be divided into two distinct groups based primarily on the execution of their carving, their layout and joinery are remarkably consistent (see chart]). All have mortise-and-tenon joints cut so that the inside shoulders of the tenons make contact with the mortised members and all have alignment marks to orient components and prevent them from getting inverted during assembly. Seven chests vary less than 3/4" in width across the front. Although this degree of precision and attention to detail is unusual for seventeenth-century New England joinery, the methods used to achieve it provide insight into the work habits of the joiners in the Savell shop.

The joiner’s goal was to produce a chest 52" wide, but to do so he had to adjust the dimensions of individual components. In the riving process, the most difficult pieces of wood to extract were the wide panels. The joiner split them from radial bolts, which were usually an eighth or a sixteenth of the whole log. The amount of straight, clear wood found between the twisted, knotty juvenile wood at the center of the tree and the sapwood just under the bark varied depending on a number of factors. Though the joiner might have had a panel width in mind when he rived his stock, he often had to settle for whatever size panels the tree would yield. In seventeenth-century joinery, close enough was good enough. On these chests, the widths of the visible panels (not including the feathered edges that fit into the grooves in the frame) vary from 8" to 87/8", so the joiners adjusted the width of the muntins to maintain an approximate overall width of 52" (see chart, P. 104).[24]

Three of the surviving chests fall short of the “standard” size. Two have narrow panels about 8" wide (figs. 9, 21). To produce a 52" chest the joiner would have had to make the muntins over 4" wide, which would be architecturally disproportionate. The third chest, which is illustrated in Luke Vincent Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in America (1901), probably represents the work of a joiner somewhat removed from the main shop tradition. This tradesman could have made a standard 52" chest with only a half-inch alteration to the muntin width, but instead he chose to produce a chest 501/4" wide. Other aspects of his dimensioning depart from the shop norm; the drawers of his chest are only 5" high, and the panels are only 12" tall. Both of these deviations could be attributed to this chest being a two-drawer example, were it not for another two-drawer chest with standard dimensioning (see chart]). In addition, some of the facade moldings and the layout and execution of the carving differ from the rest of the group.[25]

On all of the Braintree chests, the framing of the floors and configuration of the rear rails is distinctive. The neatly planed, pentagonal floor rails (front and side) are grooved to receive the feathered edges of the floorboards, which are nailed down onto the lower rear rail (fig. 23a). Floorboards supported by the rear rail are unusual in New England joined furniture. Typically, they are nailed up to a higher rail. On some of the chests attributed to the Savell shop, the floorboards are joined with a modified tongue and groove. Many tongue-and-groove joints were cut with matching planes, but the joiners in the Savell shop cut the groove with a plow plane and formed the tongue by running a rabbet on the top edge of the adjoining board and bevelling its underside (fig. 24).[26]

The construction of the rear frame also distinguishes the Savell chests from other New England work (fig. 25). The most distinctive feature is the lack of muntins. All of the chests have one large, horizontal pine back panel with feathered edges at the sides and top. The edges fit into grooves in the rear stiles and top rail, both of which have their flat faces inside the chest. The lower rail (or rails when drawers are used) is positioned under the floor and in front of the panel, and the panel is nailed to the rear rail (figs. 23b, 25). Another New England case piece with this unusual structure is a cupboard attributed to the John Taylor shop of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Taylor (d. 1683) was described as the “College Joyner” in 1638. The existence of only one Taylor cupboard with rear framing like the Braintree group suggests that William Savell, Sr., may have worked in Taylor’s shop.[27]

Both shops also employed dovetail drawer construction. The Savell joiners used a half-blind dovetail to join the drawer sides to the front (fig. 26), rabbeted the drawer back to receive the sides, and secured both joints with nails. They also rabbeted the front to receive the bottom boards and nailed them to the lower edges of the drawer sides and back. Most seventeenth-century New England drawers are simply rabbeted and nailed. Dovetail construction is generally thought to indicate London or continental influence.[28]

In a 1641 petition, William Savell, Sr., stated that he was a “Cambridge joyner” and that he had worked for Nathaniel Eaton, the first professor at Harvard. Eaton had been instructed to oversee the construction of “such edifices as were . . . necessary for a college & for his own lodgings.” Unfortunately, there is no record of the work Savell did for him. Eaton was dismissed from his position in September 1639, and when Henry Dunster took over as president of the college in 1641, the interiors were unfinished. Savell probably left Cambridge shortly after filing his petition, for his first son, John, was born in Braintree in 1642.[29]

Although the rear framing of the Braintree chests and the Taylor cupboard is unusual in Anglo-American furniture, it is relatively common on kasten from the Netherlands and areas of Dutch cultural influence. Two early New York examples (Winterthur Museum acc. 52.49 and 57.87.1) have rived clapboard backboards, feathered into grooves in the stiles and nailed to interior rails that are tenoned into the rear stiles. The joinery of these kasten is also more precise than that of most contemporary English work. These connections suggest that Savell or his master trained with or were influenced by northern European joiners in England.[30]

The objects attributed to the Savell shop are among the most carefully made examples of seventeenth-century New England furniture. Others are more elaborate, but none demonstrate comparable stock preparation and joinery. Minor variations in the execution of the carving indicate different hands; however, the framing of comparable forms is virtually identical. This consistency in construction reflects the restrictive nature of apprenticeship in the Savell shop. Given William Savell’s probable training in Saffron Walden, the furniture attributed to his shop may represent one of the “purest” English vernacular traditions that flourished in the colonies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their assistance with this article, the authors thank Joyce Alexander, Luke Beckerdite, Tara Cedarholm, Edward S. Cooke, Jr., Ted Curtin, Mary Follansbee, the late Benno M. Forman, Debra Hamilton, H. Hobart Holly, William Hosley, Charles Hummel, Rodris Roth, Robert Tarule, and Malcolm Walker. Special thanks are due Robert Trent for his unflagging support and critical review.

Appendix

Woodworking Craftsmen in Braintree

Samuel Allen (d. 1699) Allen arrived in Braintree by 1639 and was referred to as a “sawier” in a 1658 deed. He died in Braintree in 1669. His widow and son Joseph sold his son Samuel of Bridgewater “twelve Acres of Land . . . within the township of Brantry . . . neere the sawmill.” His grandsons, Joseph, Samuel, and Benjamin Allen, were all woodworkers. (Sources: Suffolk Deeds, bk. 1, p. 90, bk. 8, p. 23; Waldo C. Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree, Massachusetts, 1640–1850 [microfilm collection of index cards published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society in cooperation with the Quincy Historical Society].)

Samuel Allen (1674–1725) Samuel was a shipwright and a wheelwright. His inventory listed four lots of cedar swamp, several pieces of furniture, and a variety of tools and materials associated with his trades:

| one chest with drawers large square table a little table with draw two little tables seven chests six chairs half a dozen chairs in the kitchen 3 spinning wheels one hatchet ten dozen of spokes for cart wheels two saws one broad axe two adzes and other carpenters tools two narrow axes and two hammers one grindstone ship timber |

03-00-00 01-10-00 00-14-00 03-10-00 00-18-00 00-12-00 01-00-00 00-15-00 01-00-00 02-12-00 00-12-00 03-00-00 00-06-00 00-12-00 03-00-00 |

Samuel’s brother Benjamin was also a wheelwright, and his brother Joseph was a joiner. (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; Suffolk County Registry of Probate [hereinafter cited as SCRP], no. 5139.)

Joseph Allen (1672–1727) See text.

Joseph Bass (1665–1733/34) Joseph was the son of John Bass and Ruth Alden and the husband of Mary (Belcher). He may have apprenticed with his father-in-law, Moses Belcher, a Braintree carpenter. Joseph Bass was also related to the Savells. His grandmother, Anne, was the sister of William Savell, Sr. Joseph moved to Boston about 1705 and became a “wharfinger.” Assuming that he completed his training about 1686, Joseph could have worked in Braintree for approximately twenty years before moving. (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; Suffolk County Registry of Deeds, no. 90, p. 256.)

Samuel Bass (d. 1726) Samuel was the son of Samuel Bass and Mary Howard and the grandson of Deacon Samuel Bass and Ann Savell. Town records referred to him as “Samuel Bass-carpenter” to differentiate him from his cousin Samuel Bass (1660–1751), son of John Bass and Ruth Alden. (Sources: Charissa Taylor Bass and Emma Lee Walton, Descendants of Deacon Samuel & Ann Bass [Freeport, Ill.: Wagner Printing Co., 1940], pp. 13–15; Samuel A. Bates, ed., Records of the Town of Braintree, 1640–1793 [Randolph, Mass.: Daniel H. Huxford Printer, 1886], pp. 28, 29, 31, 37–39.)

Deacon Gregory Belcher (1664–1727) The son of Samuel Belcher, Gregory was referred to as a wheelwright, carpenter, shipwright, and ship carpenter in Braintree records. He died on July 4, 1727, “in the 63 year of his age being killed with a plough.” His estate included barrels, tubs, wooden ware, five “low chairs,” six “black chairs,” a “great chair,” three chests, a “case of drawers,” a “square table,” “sundry tools,” and a “glew pot and kettle.” The Selectmen’s Records document work done by Gregory Belcher, but it is unclear whether they refer to Deacon Gregory or his son, Gregory:

| 1713/14 Gregory Belcher mending the school house 1714/15 Gregory Belcher for a table for the school house and 1715/16 Gregory Belcher mending the school house 1724 Gregory Belcher for G. Welly coffin |

00-14-00 00-06-00 00-10-00 00-10-00 |

Gregory Belcher (1691–1727/28), who was described as a ship carpenter in an administration bond, died shortly after his father, on January 20, 1727/28. (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; SCRP, no. 5475; Selectmen’s Records for the Town of Braintree, 1688–1757, microfilm, Genealogical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah [hereinafter cited as Selectmen’s Records].)

Gregory Belcher (1606–1674) Gregory Belcher was a carpenter. He was born in County Warwick in 1606 and received a land grant in Braintree in 1639. His inventory listed a few tools, furniture—“3 chests, 2 boxes, 2 hanging cupboards, 3 tables 6 stools six chairs 6 cushions”—and a “servant” Henry, who was probably an apprentice. Belcher’s earlier servant was “Andrew Rounsimon, . . . a Scotish man dyed 8th 31 1657.” Belcher’s widow Katherine died in 1680. Presumably, much of the furniture listed in her inventory was her husband’s: “the cupboard with the lock and some small things 5s,” “6 cushions 10s another cupboard 4s,” “a great press 20s, 2 chests 2 boxes 20s,” and “a press and chairs 45s 6 tables 2 stooles.” (Sources: Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, p. 636; SCRP, no. 720; SCRP Misc. Docket; Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree.)

Moses Belcher (1635–1691) Moses Belcher was the son of immigrant Gregory Belcher. Braintree records refer to Moses as a carpenter, and the quantity and values of furniture in his inventory suggest that he was relatively successful.

| seven chests five boxes one trunk two chests in parlour one cupboard four tables three joint stools 13 chairs 2 dozen cushings for Richard Russel’s time one cradle two cupboards axes saws beetle and wedges saws augers old iron other lumber |

01-00-00 01-00-00 02-00-00 03-00-00 02-05-00 00-16-00 02-00-00 08-00-00 00-14-00 00-10-00 03-00-00 |

The cupboard valued at £3 is one of the most expensive listed in Braintree inventories. Richard Russel was probably an apprentice. (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; SCRP, no. 1875.)

Samuel Belcher (1637–1679) Samuel was a younger son of Gregory Belcher. Although his inventory does not list any tools, both Samuel and his son, Deacon Gregory Belcher, were carpenters. Perhaps Samuel’s tools went to Gregory, who had yet to finish his training at the time of his father’s death. (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree.)

Samuel Hayden (ca. 1630–1676) Samuel was born in Dorchester and moved to Braintree with his father, John, by 1640. When Samuel died in 1676, his inventory included planes and “toules” worth £1.16. Although Samuel’s trade is unknown, two of his brothers may have been carpenters. A 1676 deed mentions a “wharfe to bee set down . . . by Jonathan Hayden & Nehemiah Hayden of Brantrey.” No inventories survive for Jonathan (1640–1718) or Nehemiah (1647/48–1717), although the Selectmen’s Records list some payments made in 1716/17 to Nehemiah Hayden, Sr., for “nails and work done” and to Benjamin Hayden for “boards for schoolhouse.” Another brother, John (1635–1718), received £4 in 1688 “for plastering the meeting house and whiting of it.” (Sources: Suffolk Deeds, bk. 10, p. 121; Selectmen’s Records; Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; SCRP, no. 829.)

John Mills (1674–1749) John was a carpenter who received £3 for “repaireing the meeting house” in Braintree in 1701. (Sources: Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, p. 50.)

Stephen Paine (1652–1690) Stephen was the son of Stephen Paine and Hannah Bass. His death is mentioned in the town records: “Steven Paine a devout Christian a cunning artificer, and ingenious to admiration died in the flower of his age of the small pox May 14, 1690.” Unfortunately, his trade is not indicated in any surviving documents. His inventory included:

| a great chest and box fower chests a great table and two little ones and 4 joynt stooles fower great chayrs and ten little ones log chaine draught chaine and a payre of horse chaines two axes drawing knife and fork tines hewd timber and slitt work for a frame |

01-00-00 00-12-00 02-00-00 01-12-00 00-12-00 00-10-00 00-06-06 00-03-00 03-00-00 |

His wife was Ellen Veasey, daughter of William Veasey. They had a son, Stephen Paine (1682–1720?), who may have been a joiner in Boston. (Sources: Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, p. 658; SCRP, no. 1952.)

William Penn (d. 1688) Penn was a “sawyer” who owned property in Braintree by 1647. A 1684 deed refers to the sale of his “upper landing place where the Saw pitts are.” The deed also gave the purchaser the right to set up a mill, suggesting that Penn had not done so. Penn died in Boston about 1688. (Sources: Suffolk Deeds, bk. 1, p. 299, bk. 10, p. 29.)

Martin Saunders (1631–1706) A 1675 deed refers to Saunders as a “howse carpenter.” (Sources: Suffolk Deeds, bk. 9, p. 240.)

John Savell (1642–1687) See text.

William Savell, Sr. (d. 1669) See text.

William Savell, Jr. (1652–1699/1700) See text.

John Shepard (d. 1650) Shepard’s inventory lists “carpenter tooles” worth £4.8.3 and a grindstone. (Sources: SCRP, Misc. Docket.)

Robert Taft (d. 1724/25) “Robert Tafft of Braintree” is first mentioned in an August 20, 1679, building contract with John Bateman of Boston. Bateman agreed to pay “for the transportation of the sd frame of the sd Cellar and house from Brantrey the place where it is to bee framed to Boston.” Taft died in Mendon in 1724/25. Mendon records refer to him as both a joiner and a housewright. (Sources: Abbott Lowell Cumings, “Massachusetts and Its First Period Houses: A Statistical Survey,” in Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Architecture in Colonial Massachusetts [Boston: by the Society, 1979], pp. 196–99.)

Robert Twells (Twelves, Tweld) (ca. 1620–1696/97) Twells first appears in Braintree records in 1645. He was part of a committee that met in 1674 “about the rebuilding of the corne mill being demolished by fier.” Twells’s inventory included woodworking tools, and his death notice in the town records stated that: “Robert Tweld who erected the South Church at Boston died March 9th 1696/97 aged 77 or thereabout.” (Sources: Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, pp. 17, 693; SCRP, no. 2369.)

Peter Webb (ca. 1650–1717/18) Webb was a joiner and a miller (his father, Christopher, and brothers John and Samuel, were also millers). Peter’s wife was Ruth Bass (1662–1700), whose brother, Joseph was a Braintree joiner. Probate records for Webb refer to him as a “joyner,” and his inventory included “2,030 foot of boards.” (Sources: Bass and Walton, eds., Descendants of Deacon Samuel & Ann Bass, p. 15; SCRP, no. 3998.)

William Veasey (1616–1681) Born in Gumley, England, Veasey arrived in Braintree by 1643. His inventory listed “a thousand of board” valued at £1.15 and £15.8 “due from several persons upon the sawmill account.” (Sources: Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree; SCRP, no. 1182.)

H. Hobart Holly, Braintree, Massachusetts, Its History (Braintree, Mass.: Braintree Historical Society, 1985), pp. 29–30. Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, ed., Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England (Boston: Press of William White, 1853), vol. 1, 1628–1641, p. 119. Seventeenth-century Braintree included the present-day city of Quincy (except North Quincy) and the towns of Braintree, Holbrook, and Randolph.

Waldo C. Sprague, Genealogies of the Families of Braintree, Massachusetts, 1640–1850. This microfilm collection of index cards is published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society in cooperation with the Quincy Historical Society. Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, p. 640.

James Savage, A Genealogical Dictionary of the First Settlers of New England, 4 vols. (1860–1862; reprint ed., Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1965), 4:27, 28. The Woburn reference may have to do with the will of John Savell’s grandfather, John Tidd. Tidd left John 20s (Middlesex County Probate Records, vol. 1, no. 2258, p. 78). Bates, ed., Records of Braintree, p. 664.

Joseph Moxon, Mechanick Exercises; or the Doctrine of Handyworks, 3d ed. (London, 1703; reprint ed., Mendham, N.J.: Astragal Press, 1994), p. 88.

For more on the use of the various planes, see Moxon, Mechanick Exercises, pp. 64–74; Charles F. Hummel, With Hammer in Hand (1968, reprint ed., Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1982), pp. 105–24; and W. L. Goodman, The History of Woodworking Tools (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1964), pp. 56–84. The whole issue of how a seventeenth-century joiner held his stock for planing is one for further study. Moxon recommended: “To plane this Square, lay one of its broad Sides upon the Bench, with one of its ends shov’d pretty hard into the Teeth of the Bench-hook, that it may lie the steddier” (Moxon, Mechanick Exercises, p. 81). With its irregularly tapered cross-section, riven stock often required shimming to steady it. For an excellent illustration of a late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century English woodworking shop, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 45, fig. 13.

Erving, Random Notes on Colonial Furniture, pp. 22, 23. This chest is also illustrated in Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), p. 24, fig. 9. Two chests attributed to the Savell shop do not have drawers (figs. 21, 22). The latter reportedly belonged to Jonathan Fiske (1774–1864) of Medfield, Massachusetts, and his wife Sally Flagg (1772–1865). In 1798, Fiske bought a house, land, and tannery from Oliver Adams (1777–1848) of Medfield. Oliver’s grandmother was Jemmima Morse (1709–1785). Her father, Joshua, married Elizabeth Penniman (1675–1705) of Braintree. Joshua’s second wife and Jemmima’s mother was Mary Paine, who was also from Braintree. It is possible that the chest entered the Adams family through one of these marriages and that it was included in the sale from Oliver Adams to Jonathan Fiske (George M. Fiske, The Migration of Jonathan Fiske and Sally Flagg [Auburndale, Mass.: privately printed, 1923], n.p.; Irving P. Lyon to Cornelia B. Fiske, March 15, 1938, private collection; Andrew Adams, A Genealogical History of Henry Adams of Braintree, Massachusetts and His Descendants, 1632–1897 [Rutland, Vt.: Tuttle Company Printers, 1898], p. 21). William S. Tilden, History of the Town of Medfield, Massachusetts, 1650–1886 (Boston: George H. Ellis, 1887), pp. 392, 441.

The most notable exception is a group of chests from Plymouth colony (see St. George, Wrought Covenant, p. 28, fig. 1a, p. 38, fig. 20a).

Edward Everett Hale, ed., Note Book kept by Thomas Lechford, Esq. Lawyer, in Boston, Massachusetts Bay, from June 27, 1638 to July 29, 1641 (Camden, Me.: Picton Press, 1988), pp. 410–11. Savell’s petition is undated but seems to fall about 1641. Josiah Quincy, The History of Harvard University, 2 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: John Owen, 1840), 1:452. This material is also discussed in Harvard College Records, Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 15 (Boston: by the Society, 1925), pp. xvii–xxii. Although no new lodgings were built for Eaton, repairs were possibly made to his house, which was formerly William Peyntree’s. In a ca. 1650 letter, Dunster described conditions when he took over as president:

They had finished ye Hall yet wthout skreen table form or bench. . . . No floar besides in & above ye hall layd, no inside sepating [separating?] wall; made nor any one study erected throughout the hous. Thus the work fell upon mee 3d 8ber 1641 wch by ye Lords assistance was so far furthered yt ye students dispersed in ye town & miserably distracted in their times of discourse came into commons into one house 7ber 1642. (Harvard College Records, p. 7)

Records of several towns returned to Boston, New England Historic Genealogical Register, vol. 3, p. 247.