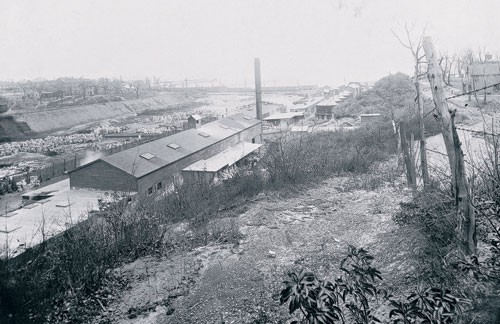

Photograph, South Amboy Terra Cotta Company, South Amboy, New Jersey, early twentieth century. This view faces east; note the kilns and the stacked blocks of architectural terracotta. Unfortunately, the “Great Wall of Terracotta,” which supports the sand hill from which the photograph was taken, is not visible. (Courtesy, Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission.)

A small portion of the “Great Wall of Terracotta” showing dozens of stacked blocks of architectural terracotta. These pieces were laid flat during the construction of the wall. They display a lime-green glaze and were made in a storefront Gothic style. The entire facade of the building might have been stacked here. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Richard Veit.)

View of the retaining wall showing the carefully stacked blocks. A luxuriant growth of brambles and poison ivy helped protect the wall and hide it from the prying eyes of visitors.

Two terracotta blocks like those shown stacked in fig. 2. Each is three feet high. Note the hollow back of the piece at right, which displays marks left by the modeler’s hands during manufacture.

Two examples of polychrome-decorated red terracotta. Each is three feet high. Note the uneven glazing on the piece at left, perhaps the flaw that led to these pieces being discarded. The design, intertwined vines, looks vaguely Celtic.

The Studebaker emblem discovered during salvage excavations. Presumably it was made to grace the showroom of a Studebaker dealership and is an exceptional example of polychrome terracotta. (Photo, Peter A. Davis.)

From April 14, 2002, to May 30, 2003, the Cornelius Low House Museum, Piscataway, New Jersey, hosted a landmark exhibit, “Uncommon Clay: New Jersey’s Architectural Terra Cotta Industry.”[1] Through artifacts and interpretative text, the exhibition examined New Jersey’s role in the terracotta industry. While preparing for the show, museum staff visited a number of sites of former terracotta factories that in their heyday had produced vast amounts of architectural terracotta. It was hoped that these sites would yield equally vast quantities of artifacts to enrich the museum’s displays. Many of the properties contained a great deal of discarded terracotta, and surface collections were gathered. These wasters had been reused by frugal factory owners to construct bridge abutments, culverts, retaining walls, and a variety of everyday structures. The greatest find, an enormous retaining wall of terracotta wasters, was made at the site of the South Amboy Terra Cotta Company in South Amboy, New Jersey. We have chosen to call this discovery the “Great Wall of Terracotta.”

The South Amboy Terra Cotta Company was located near Raritan Bay and the rich Cretaceous clay deposits of the Raritan Formation. The company began operation in 1903 and was managed by two brothers, Christian and William Mathiasen, and their colleague Peter Olsen.[2] Initially the firm worked out of the leased buildings of the former Swan Hill Pottery, an important manufacturer of yellow ware and Rockingham,[3] and in 1906 purchased the property outright. The operation seems to have been an immediate success, and by 1911 it employed two hundred people (fig. 1). In 1927 the South Amboy Terra Cotta Company merged with the Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Corporation, which had plants in Perth Amboy and Woodbridge. By the late 1930s, with a shift in architectural styles, many terracotta factories shuttered their doors. Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Corporation closed its South Amboy and Woodbridge plants in 1941 and shifted all its production to Perth Amboy. Some of the factory buildings in South Amboy survived under a variety of different uses, most recently as warehouses.

In the fall of 2001 the authors explored the factory grounds. Parts of the factory complex, minus the kilns, were standing but in poor condition. While exploring a wooded and heavily overgrown portion of the property, the authors discovered a wall—approximately four hundred feet long and ranging from ten to roughly twenty feet in height—made from discarded architectural terracotta. It was composed of hundreds of pieces of architectural terracotta stacked one on top of another (figs. 2, 3). These included polychrome pieces, hollow terracotta wall tiles, glazing samples, ashlar blocks, and several half-buried fifty-five-gallon metal drums filled with discarded pyrometric cones. It was immediately apparent that the site contained an important collection of New Jersey terracotta. Moreover, the wall appeared to be an undisturbed historic feature of the property.

Unfortunately, the tract was slated for development. Abby Hoffman, a ceramist whose tile work was used as an educational component of the “Uncommon Clay” exhibit, knew the property owner and made arrangements to salvage select samples of the terracotta. Under the direction of Abby and her partner, Robin Rosen, a group of volunteers photographed and disassembled portions of the wall. A number of exciting finds were uncovered, including numerous architectural elements such as egg-and-dart moldings, swags, recessed panels, molding profiles, and rope moldings. Pieces of swimming-pool coping and examples of ashlar block were also salvaged. Some of the terracotta was stamped “Federal Seaboard,” indicating a post-1927 date, or “Sample.” Other pieces bore various color glazes or were experimental. All predate the factory’s closure in 1941.

In some instances entire building facades appear to have been recycled as part of the retaining wall. The reasons for this are not clear. Some pieces show evidence of manufacturing problems: uneven glazing, slumping, and chipping. Other pieces, however, appear to be unblemished (figs. 4, 5). Perhaps they were discarded when orders were canceled, a common problem during the Great Depression.[4]

The largest and most spectacular item uncovered was a blue-and-white glazed Studebaker logo about three-and-one-half-feet square and weighing approximately three hundred pounds. The logo consists of a sculpted automobile wheel with a balloon tire and wooden spokes, with details such as lug nuts and an air valve carefully molded into the terracotta. The word Studebaker is emblazoned in bannerlike fashion across the wheel (fig. 6).

The artifacts uncovered in South Amboy add to our knowledge of the terracotta industry in New Jersey. They help us to understand the range of items the factory produced, the glazes and manufacturing techniques employed, and some of the things that went wrong in the production process. While many of the pieces are mundane blocks of extruded wall tile, the unusual items such as the Studebaker logo highlight the workers’ skills and the possibilities of terracotta as a medium for artistic expression.

The story has a happy ending. Through the initiative of Friends of Terra Cotta and the gracious help of volunteers, several of the more spectacular finds have been targeted for a permanent home in a public institution.

Mark Nonestied, Assistant Curator, Middlesex County Museum, Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission; mmn4444@aol.com

Richard Veit, Director, Monmouth University Center for New Jersey History, Department of History and Anthropology, Monmouth University; rveit@monmouth.edu

Hillary Murtha, Uncommon Clay: Exhibit Catalog for New Jersey’s Architectural Terra Cotta Industry (New Brunswick, N.J.: Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission, Cornelius Low House Museum, 2004).

Walter Geer, The Story of Terra Cotta (New York: T. A. Wright, 1920).

M. Lelyn Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware in Central and Southern New Jersey (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1988).4. Andre S. Dolkart and Susan Tunick, George and Edward Blum: Texture and Design in New York Apartment House Architecture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).

Andre S. Dolkart and Susan Tunick, George and Edward Blum: Texture and Design in New York Apartment House Architecture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).