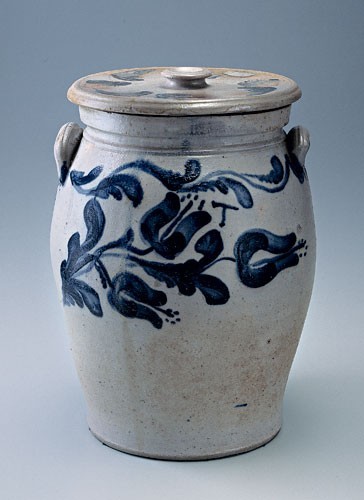

Storage jar, Solomon and John Bell, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, 1874. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17". (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) This six-gallon presentation piece is impressed “John Bell, Waynesboro” under its handle and matching lid.

Detail of the inscription on the base of the jar illustrated in fig. 1, which reads: “January the / 1 1874 / Made by Solomon Bell / for Tillie Bell / Waynesboro / Pa.”

Detail of the T in cobalt decoration on the jar illustrated in fig. 1.

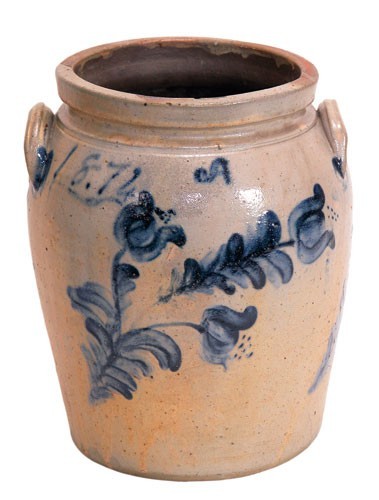

Storage jar, Solomon and John Bell, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, 1874. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Dr. Robert Steiner; photo, James Smith.)

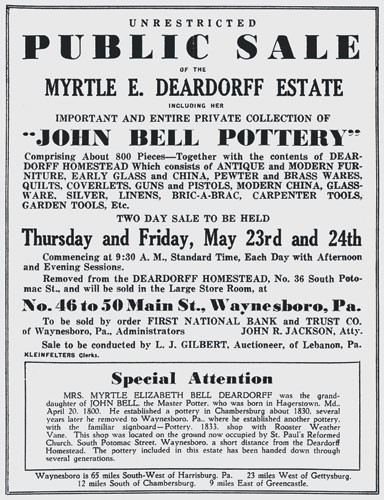

Auction catalog cover for 1935 public sale of Myrtle E. Deardorff estate. (Courtesy, Alexander Hamilton Memorial Free Library.)

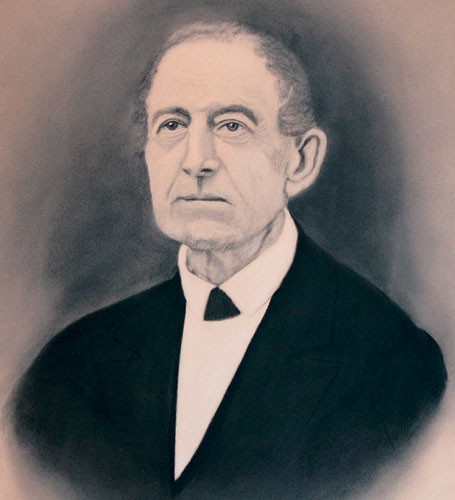

Attributed to Tillie Bell, Portrait of John Bell, late nineteenth century. Pastel on paper. 32'' x 24''. (Courtesy, Renfrew Museum; photo, James Smith.)

A newly discovered six-gallon stoneware presentation jar reflects the close, personal relationships that existed within the legendary Bell family of potters of the Shenandoah Valley (fig. 1). The lives of five family members intersect with the creation of this elaborately decorated and historically important vessel.

We know from the inscription on the base that the jar was made by master potter Solomon Bell, who, with his brother Samuel, operated a prolific factory in Strasburg, Virginia, for more than four decades.[1] However, Solomon made this particular piece for his niece Matilda Catharine Bell (known as Tillie) on New Year’s Day, 1874, while visiting the pottery owned by his brother John in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania (fig. 2).

Tillie Bell, the daughter of John and Mary Elizabeth Bell,[2] lived her entire life in the family house on the southwest corner of West Main Street, in close proximity to her father’s shop on Leitersburg Street (now South Potomac Street). The youngest of three daughters who survived into adulthood, Tillie appears to have been devoted to her family and popular in her community. She and her father were actively involved in the local Lutheran Sunday school, which the latter organized.[3] Their combined service as Bible class teachers extended over a half-century. Like her Uncle Solomon, Tillie never married. According to a 1901 obituary, however, she had a “bright disposition and numerous friends” and was renown for “her unostentatious charity and the many good deeds of her hands.”[4]

Family concerns were quite literally matters of life and death for both Tillie and Solomon Bell. Following a fire that destroyed the Bell pottery, Tillie experienced a “severe nervous shock which resulted in heart affection”[5] and she died at the relatively young age of sixty-three. Solomon himself expired following an illness brought on by the heat of a kiln firing he was rushing to finish so he could attend the wedding of his nephew Richard Franklin Bell.[6]

A brushed cobalt J and T appear separately on either side of Tillie’s stoneware jar (fig. 3). The year 1874 was also brushed in cobalt underneath each handle for added emphasis. An intertwined floral and leaf pattern, which appears on both sides of the jar, is one of the most extensive examples of cobalt decoration seen on Bell stoneware. This distinctive design was probably executed by Tillie’s brother Victor Conrad Bell, who became a decorator in his father’s shop rather than a potter because as a child he reputedly severed an artery in his wrist, making it difficult for him to turn pottery on a wheel.[7] However, it is unclear exactly to whom the initial J refers; it could be that John Bell, or perhaps his son John W. Bell, played some role in the production process.

Two other extant stoneware vessels dated 1874 and marked “John Bell Waynesboro” provide further context for the vessel made for Tillie Bell. The first is a four-gallon jar that, although it lacks an inscription by Solomon Bell, does display a brushed 1874 date under each handle, identical floral decoration, and the initial J on one side and B on the other.[8] It is possible that these letters stand for “John” and “Bell” or, perhaps, the first name of another family member beginning with B.

A second jar, a smaller two-gallon vessel, was made by Solomon for another niece—Annie Bell, the wife of John’s son Victor—on the same day he made the jar for Tillie. This example is inscribed “Made by Solomon Bell for Annie Bell January 1, 1874.”[9] The presence of “V.C. Bel[l]” brushed on one side and the initial A on the other provides definitive proof that it was decorated by Victor (fig. 4).

In May 1935 an astounding assemblage of nearly eight hundred pieces of Bell pottery belonging to Mrs. Myrtle E. Deardorff, the deceased daughter of Victor and Annie Bell, was sold in a two-day estate auction of the contents of her home on South Potomac Avenue (fig. 5).[10] The special presentation jars made for Tillie and Annie Bell, however, were not among the many crocks, jugs, and animal forms listed in the auction catalog, indicating a different chain of ownership for these vessels. A front-page newspaper article did mention that another item of Tillie’s was in the possession of the Deardorff estate—“crayon” or pastel portraits she had sketched of John and Annie Bell that reportedly were donated to the Waynesboro Public Library.[11] Although the library has no record or knowledge of the portraits, the Renfrew Museum in Waynesboro owns an early pastel likeness of John Bell by an unidentified artist, which is most likely Tillie’s rendering (fig. 6).

This presentation jar, made for Tillie Bell, is historically important for several reasons. In addition to affording a rare opportunity to document the convergence of Strasburg and Waynesboro stoneware traditions, it also illuminates the lives of women who actively supported the Bell potters and who, until now, have remained in the background of history. The vessel also serves as a lasting reminder of the strong bonds that were the hallmark of this extended family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to James Smith, executive director of the Nicodemus Center for Ceramic Studies, Penn State Mont Alto, and Dr. Al Luckenbach for their expertise and guidance with this article. James Ross, executive director of the Renfrew Museum, and Dr. Robert Steiner of Waynesboro were also very helpful.

John E. Kille, Assistant Director, The Lost Towns Archaeology Project; jkille@aacounty.org

H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, N.C.: The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), p. 373.

John Bell’s wife is referred to as Elizabeth A. L. Bell (in her obituary notice, Village Record, June 12, 1868, p. 2), as Mary Elisabeth Fry Bell (A. H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery [Strasburg, Va.: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929], p. 31), and Mary Elizabeth Fry Bell (H. E. Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 369).

Rice and Stoudt, Shenandoah Pottery, p. 37; Waynesboro Record, January 24, 1901, p. 8.

Waynesboro Record, January 10, 1901.

Ibid.

Rice and Stoudt, Shenandoah Pottery, pp. 57, 59.

Ibid., p. 38.

This jar is illustrated in a recent stoneware auction; see American Pottery Auction, sale cat. (Clarence, N.Y.: Vicki and Bruce Waasdorp, March 21, 2004), lot 206.

This vessel is illustrated in a study of Pennsylvania stoneware with an assigned date of 1879; see Phil Schaltenbrand, Big Ware Turners: The History and Manufacture of Pennsylvania Stoneware (Bentleyville, Pa.: Westerwald Press, 2002), p. 48. However, the jar was made in 1874, a date given in its inscription and applied in cobalt on its shoulder and beneath one handle. This piece descended through three generations to its present owner, Dr. Robert Steiner of Waynesboro, and is on loan to the Renfrew Museum.

The auction of the contents of the Deardorff residence—called the “mystery house” by the auctioneer, L. J. Gilbert—received widespread attention for the sheer magnitude of the collection and the many rare examples it contained. Record Herald, May 27, 1935, p. 1. Approximately three hundred people attended the opening of the sale, which attracted dealers, “both professional and amateur,” from as far away as Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Record Herald, May 23, 1935, p. 1; Record Herald, May 24, 1935, p. 1.

Record Herald, May 27, 1935, p. 1. Although traditionally identified as a portrait of John Bell, it is possible that this likeness is of his son John William Bell, who managed the family pottery business after his father’s death, in 1880. This 1935 newspaper article notes that the portraits of John and Annie Bell “are at least forty years old,” a time frame that implies an association with John W. Bell and his death, in 1895.

Also worth noting are two undated, unattributed newspaper clippings in the special collections of the Alexander Hamilton Memorial Free Library, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. Each article features the same photograph, of a bearded man of advanced years identified as John W. Bell, who resembles the clean-shaven subject of Tillie’s portrait. The brief biographical sketches accompanying these photos, however, center not on John W. Bell but on his father, whose seldom-used middle initial is B. See H. E. Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, pp. 368–69. It is not unusual to encounter identity confusion when a father and son have very similar names and are in the same profession. An inadvertent interchange of these names is also found in the obituary notice for Tillie’s sister Henrietta, or Hettie, which referred to her parents as John William and Mary Elizabeth Bell (Daily Record and Blue Ridge Zephyr, November 10, 1916, p. 1).