Unknown artist, Sir Thomas Dale, England, ca. 1615. Oil on canvas. 80" x 45". (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Art, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund; photo, Ron Jennings.)

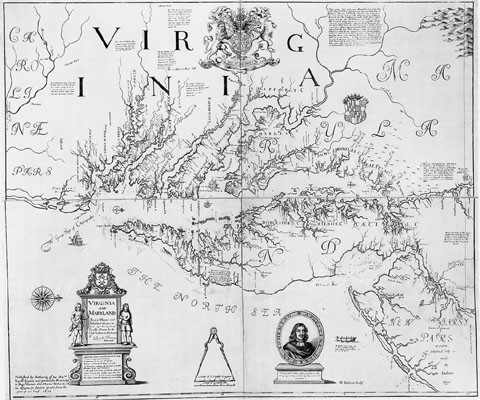

Augustine Herrman, Virginia and Maryland, 1670. Engraving on paper. 32" x 37". (Courtesy, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.)

Medallion of Prince Maurice of Orange, Holland, 1615. Cast brass. 1 3/4" x 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Flowerdew Hundred Museum.)

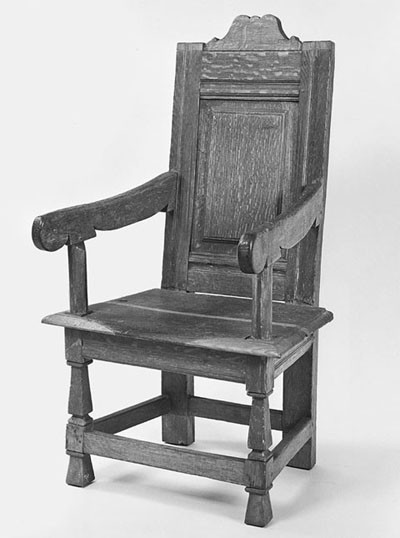

Court cupboard, possibly Virginia, 1620–1680. Oak. (Illustrated in Antiques 24, no. 9 [October 1938]: 216.)

Clothes cupboard, Virginia, 1650–1690. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 61 1/2", W. 61 3/4", D. 20". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

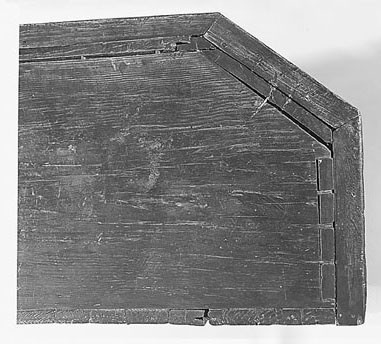

Detail of the back of the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

Kast, New York, 1650–1700. White and red oak. H. 70", W. 67", D. 25". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Millia Davenport, 1988 (1988.21) Photograph ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pieter de Hooch, Portrait of a Family Making Music, Holland, 1663. Oil on canvas. 39 3/4" x 46". (Courtesy, Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of the Hanna Fund.)

Detail of a turned foot on the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of the mitered joinery and raised panels on the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

Drawing of a (a) mitered mortise-and-tenon joint and (b) flat-faced mortise-and-tenon joint. (Adapted from a drawing in Peter M. Kenny, Frances Gruber Safford, and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten: The Dutch-Style Cupboards of New York and New Jersey 1650–1800 [New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991], p. 12; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Detail of the dovetailed top and splined backboards on the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of the pegboard in the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

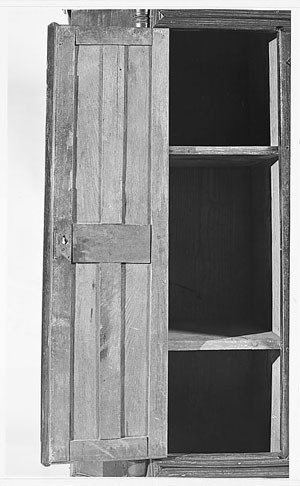

Detail of the interior shelving on the clothes cupboard illustrated in fig. 6.

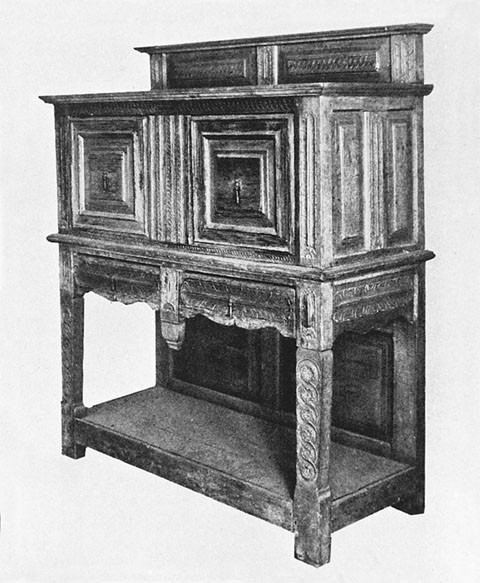

Armchair, southeastern Virginia, 1680–1700. Cherry. H. 41 3/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Armchair, Virginia, 1680–1700. Cherry, hickory, and white oak. H. 43 1/2", W. 25", D. 22 3/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Turned Great Chair, unidentified maker, New York or New Jersey, 1700-1728. Maple, ash, and cherry; painted black. H. 50", W. 23", D. 18". (Courtesy, Albany Institute of History & Art, Rockwell Fund.)

Stretcher table, eastern Virginia, 1690–1720. Walnut with cedrela. H. 26", W. 46 1/4", D. 32 1/4". (Courtesy, H. L. Chalfant Antiques.)

Draw-bar table, New York City, 1690–1710. Red gum with tulip poplar and pine. H. 29 3/4", frame dimensions: 35 7/8" x 20 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

During the 1930s, American furniture historians first began to speculate on the surprising “Continental” features found on seventeenth-century Chesapeake furniture. To the discriminating eye, this furniture appeared different from contemporary New England work, while displaying a closer affinity to furniture from the Dutch colonial regions of New York and New Jersey. Material culture and documentary evidence strongly suggest that Dutch traders and artisans were the principal source of Continental influences in the seventeenth-century Chesapeake. Archaeological evidence of extensive Dutch trade in tobacco has been found at Jamestown and Flowerdew Hundred Plantation in Virginia, St. Mary’s City and Providence in Maryland, and other sites throughout the region. Dutch trade in the Chesapeake is also well documented in the historical record. By the third quarter of the seventeenth century, the term “Dutch” was applied to chairs, tables, chests, cupboards and other forms in Chesapeake inventories; however, it is extremely unlikely that all of these objects were imported from Holland. Given the extent of Dutch involvement in the region’s early history, it was inevitable that their styles would influence furniture making in the Chesapeake.

The seventeenth century is universally considered the golden age of Dutch culture. After the ten northern provinces of the Habsburg Lowlands united in 1579 under the Union of Utrecht, a bloody war for independence against the Spanish ensued. By 1609, the Spanish had withdrawn from the Netherlands, and almost immediately the new nation—the “Lands of the United Netherlands”—became the preeminent maritime and commercial power of western Europe. The Dutch established colonies in South Africa, Indonesia, Formosa, Japan, North and South America, and the Carribean. In North America they controlled New York, New Jersey, and Delaware; in South America they controlled Surinam; and in the Carribean they controlled Curacao and St. Eustatius. With colonies to the north and the south of the Chesapeake, the Dutch were strategically positioned to exploit the market for Chesapeake tobacco.[1]

By the first quarter of the seventeenth century, Dutch traders had established a close relationship with the English settlers of Maryland and Virginia, who considered them former political and religious allies. During the Dutch wars for independence against Roman Catholic Spain, England and Holland had formed a powerful military alliance. By the 1580s, Queen Elizabeth I was allowing English troops to fight with the Dutch, and in 1595 she dispatched an army under the command of the Earl of Leicester. Many of the English soldiers who served in the Netherlands later became prominent leaders in Virginia. Sir Thomas Dale (fig. 1), for example, fought with the Dutch from 1588 to 1609, when he departed for Virginia under the auspices of the Virginia Company of London. He became the first marshal of the new colony and served as the deputy governor from 1611 to 1618. As a reward for his former service, the States General of the United Netherlands granted seven years back wages to Dale in 1618 and expressed their appreciation for his “service . . . in Virginia.” In their grant, the Dutch authorities noted that Dale had “sailed . . . to Virginia . . . to establish a firm market there for the benefit and increase of trade [for the Dutch].” Other Virginia leaders who served in the Netherlands were Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Yeardley, and Nathaniel Littleton. These men were part of a powerful pro-Dutch faction who influenced Virginia’s political and commercial affairs.[2]

During the first three quarters of the seventeenth century, Dutch trading ships sailed regularly through the waters of the Chesapeake, exchanging household and luxury goods for tobacco. In 1619, these traders left an indelible mark on Virginia history when they sold “20 and odd Negroes”—the first African slaves brought to the colony. Thirty years later, a promotional pamphlet on Virginia’s economy noted that there were twelve Dutch ships anchored in the Tidewater region on December 25, 1646. The most detailed account of Dutch trade in the Chesapeake is the journal of Captain David Peterson DeVries. Between 1633 and 1637, he made four voyages up the James River to purchase tobacco. In 1635, DeVries discovered four other Dutch ships, which “make a great trade here every year.” On his voyage to Jamestown in 1633, DeVries visited the home of Governor John Harvey, who entertained him with “a Venice glass” of sherry. With Harvey’s permission, DeVries traded openly for tobacco at Newport News, Kicotan, Flowerdew Hundred Plantation, and Jamestown. During his trips, DeVries made several important observations on the Dutch tobacco trade; in 1635, he wrote that for a Dutch trader to succeed in the Virginia tobacco market, “he must keep a house here, and continue all the year, that he may be prepared when the tobacco comes from the field, to seize it.”[3]

With the support of the colonial governments of Virginia and Maryland, Dutch traders established permanent trading posts at strategic points along the Chesapeake waterways in order to maximize their access to the tobacco market. In 1641, merchants Derrick and Arent Corsen Stam built a trading post in Accomack County on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Their clients included Nathaniel Littleton, the former English soldier who had fought in the Netherlands. Littleton leased the Stams land, a sloop, and a barge. Six years later, Rotterdam merchant Simon Overzee settled in Lower Norfolk County, Virginia. After two financially advantageous marriages (the first to Sarah Thoroughgood and the second to Elizabeth Willoughby), he moved to St. Mary’s City, Maryland, where he traded during the 1650s. In 1649, a group of Rotterdam merchants established a trading post at Kicotan, midway between Jamestown and Flowerdew Hundred Plantation on the James River. Other Dutch trading posts in Virginia during the 1640s and 1650s were William Moseley’s in Lower Norfolk County and Derrick Derrickson’s in York County. By 1660, there were at least five Dutch settlements established solely for the purpose of trading for Chesapeake tobacco.[4]

Chesapeake planters depended on Dutch traders for many of their household and luxury goods. In 1623, the governor and council of Virginia reported that the Dutch “take away much [of] our Tobacco . . . [b]ecause many of their commodities [such] as Sacke, sweete meates and strong Liquors are soe acceptable to the people.” When Puritan leader Richard Ingle seized the Dutch ship Speagle at St. Inigoe’s Creek in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, in 1643, he found her holds laden with “strong waters,” sugar, lemons, shirts, hats, stockings, frying pans, and other household goods. The “Goods brought from the Dutch Shipe” had a value equal to twelve hundred pounds of Maryland tobacco. Dutch cargoes typically included “all sorts of domestic manufactures, brewed beer, linen cloth, brandies, or other distilled liquors, duffels, coarse cloth, and other articles for food and raiment.”[5]

During the English Revolution, Dutch trade in the Chesapeake expanded as commerce between Britain and her colonies deteriorated. In 1650, however, the emboldened English government under Cromwell passed the first Navigation Act to prohibit Dutch trade and to require that all Virginia tobacco be shipped directly to England aboard British ships. The colony’s governor, Sir William Berkeley, attacked the new law and lamented its economic effect on the colonists:

The Indians, God be blessed round about us are subdued; we can onely feare the Londoners, who would faine bring us to the same poverty, wherein the Dutch found and relieved us; would take away the liberty of our consciences, and tongues, and our right of giving and selling our goods to whom we please.

Between 1652 and 1674, England and the Netherlands fought three successive wars, largely over restrictions against Dutch trade in the colonies. In 1664, England took control of the Dutch colonies in New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. As trade restrictions in the Chesapeake increased, a pro-Dutch political faction consisting of Governor Berkeley and members of the Yeardley, Littleton, Thoroughgood, and Custis families intervened. Not only did trade continue, but a small number of Dutch families migrated to the Chesapeake from former Dutch colonies, perhaps seeking congenial ground among old friends and trading partners. Among these immigrants was Augustine Herrman, a merchant and surveyer who had been involved in the tobacco trade between New Netherland and the Chesapeake since the 1650s. Herrman moved to Cecil County, Maryland, in 1660 and later published one of the most important maps of Maryland and Virginia (fig. 2). The Dutch population in the Chesapeake remained small, however, and assimilated quickly into the English-speaking community.[6]

Numerous artifacts associated with the Dutch trade have been excavated at seventeenth-century archaeological sites throughout the Chesapeake region. Dutch pottery and other ceramics—German stoneware and Chinese export porcelain—bartered for tobacco are relatively commonplace. At Kicotan, over half of the tobacco pipes excavated were made in Holland. Similarly, large quantities of Dutch tin-glazed earthenware (including fireplace tiles), lead-glazed earthenware, and bricks (which arrived as ballast) were recovered at Jamestown. Excavations at Flowerdew Hundred Plantation have produced one of the most emblematic symbols of the Dutch presence—a cast brass medallion depicting Maurice, Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau, dated 1615 (fig. 3). The medal commemorates Maurice’s induction into the English Order of the Garter in 1612, in honor of his service in the war against Spain. One of Maurice’s soldiers in the Dutch war for independence was Sir George Yeardley, the founder of Flowerdew Hundred Plantation in 1619. After excavating the home site of Dutch merchant Simon Overzee at St. Mary’s City, Maryland, archaeologist Henry Miller noted that “the evidence strongly implies that the Dutch, rather than the London merchants, dominated the tobacco trade during the first decades of settlement in Maryland.” Miller’s findings were amplified by archaeologist Al Luckenbach, whose recovery of Dutch trade materials at Providence in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, revealed “an unsuspected connection of such strength that a reevaluation of this historic period is required.”[7]

The inventory of Captain William Moseley (d. 1671) reveals a great deal about the impact of Dutch trade on the material culture of the early Chesapeake. Moseley lived in a large (by seventeenth-century Chesapeake standards), two-and-a-half-story house with an entry, a hall, and a master bedchamber on the first floor, three additional chambers on the second floor, and a study and storeroom in the garret (see Appendix A]). Furnishing “Mr. Moseley’s Study in the garrett” were a little table, a small case of drawers, and “a parcell of Books some french dutch Latten & English.” In the “hall chamber” on the second floor were eight chairs, a close stool, a small table, a looking glass, “a little frame to putt a bason on,” and “one greate dutch trunck & what linnen is in it” valued at 3,470 pounds of tobacco. Moseley’s best furnishings were reserved for the “hall” on the first floor. The hall was generally the most elaborate room in seventeenth-century households, and it served a variety of social functions. Moseley’s hall furniture included a bed, a couch and two cushions, six chairs, five stools, a “side Borde & Cloath,” a table and carpet, six pictures, a looking glass, and “a greate dutch Cash,” or kast, valued at 500 pounds of tobacco. This value was more than twice that of any other case piece in his house. Moseley’s inventory also lists the contents of the kast, which were valued at 2,300 pounds of tobacco: “his woolen waring apparrell . . . 1300, a parcell of Linnen . . . 500, one old Cloaths Suite . . . 300, a small parcell of Buttons & thread a small Remnant of Sewing a Capp & a paire of topps . . . 200.” Used for the storage of linens and other expensive household textiles, kasten were the most important furniture forms in seventeenth-century Dutch homes. The use of Moseley’s kast differed significantly from the standard Dutch pattern, since it housed his personal clothing as well as linen and household textiles.[8]

Similar patterns of usage are revealed in a court case involving Simon Overzee. According to depositions taken in 1658, Overzee’s plantation near St. Mary’s City consisted of a kitchen, a dairy, a quarter for his indentured servants, and his main residence. Overzee’s house contained a hall and a master bedchamber, with additional sleeping space for guests in the loft. In the Overzees’s bedchamber was a closet for the storage of “meate & other necessaries of household” and a “Greate Dutch Trunk” for Mrs. Overzee’s wardrobe. Her dresses and larger garments were kept in the top compartment, and her bodices, aprons, neck pieces, and other small items were kept in “the Under Drawers.”[9]

Seventeenth-century Chesapeake inventories are replete with references to a variety of furniture forms specifically identified as “Dutch” (see Appendix B]). The majority of these references are from areas where the Dutch tobacco trade flourished, such as Norfolk County, Virginia, and the Eastern Shores of Virginia and Maryland. In 1657, Edward Dowglas of Northampton County on Virginia’s Eastern Shore bequeathed to his daughter “one Dutch cupboard,” and in 1673, John Fawsett of neighboring Accomack County left his son a “greate Dutch chest.” Similarly, the 1676 inventory of John Carr of Cecil County, Maryland, lists “6 turn’d dutch chairs” valued at 360 pounds of tobacco. Unfortunately, most of these inventories fail to specify whether the objects were imported from Holland or made by local tradesmen in a style perceived as being “Dutch.” The August 18, 1696, inventory of Thomas Teackle of Accomack County, Virginia, appears to be an exception. Although it includes ambiguous references to a “Round Dutch Table” and “an old Dutch cupboard,” his inventory also lists “a pokomoke wheele of the Dutch fashion.” The term “pokomoke,” which refers to the creek (Pocomoke) dividing Virginia’s and Maryland’s Eastern Shores, suggests that Teackle’s spinning wheel was made by a local tradesman in what his appraisers considered “the Dutch fashion.” Evidently, some early Chesapeake joiners were capable of replicating Dutch forms.[10]

Homer Eaton Keyes was one of the first American furniture historians to speculate on the Continental aspects of seventeenth-century Chesapeake furniture. In an article on American joined chairs, Keyes illustrated a rare example “discovered by Mr. Goodwin in Virginia” (fig. 4). The chair’s fielded, molded back panel and sawn legs differed from the New England examples he illustrated, prompting him to write: “It is perhaps significant that these features occur in a chair . . . from a part of the country . . . [with] settlers from the Continent.” Keyes reasserted the argument for Continental influences in seventeenth-century Chesapeake furniture when he published a photograph of an oak court cupboard found “amid squalid surroundings” in Virginia (fig. 5). Keyes wrote:

There seems no reason to doubt that it hails from the 1600’s. But what was the nationality of its author? On that point we can say only that the cupboard shows not a trace of English tradition. The backboard along the top, the rectangular posts and the central drop, the closed back of the lower compartment and the double fielding of the panels recall renaissance cupboards of the European continent . . . Was this massive article of furniture made somewhere in Virginia by a European immigrant, or was it brought from across the ocean? . . . If the cupboard may be given clear title to an American birthright, it will occupy an important place in the domain of our earliest furniture.[11]

Despite previous misconceptions, the Chesapeake’s artisan community was never uniformly English (see Appendix C). As early as 1608, the Virginia Company of London sent “eight Dutchmen and Poles” to work as glass blowers at Jamestown, and recent archaeological excavations have uncovered numerous examples of their work. Four of the “Dutchmen” in this group were later dispatched to work as carpenters for the purpose of building a “castle” for the local Indian chief, Powhatan. In 1621, the Virginia Company instructed Governor Francis Wyatt to “take care of the Dutch sent to build saw mills” and to ship lumber down the James River for export to Europe. Six years later, the Council and General Court of James City County, Virginia, noted that “Derrick the Dutch Carpenter” had agreed to build a boat for a local Englishwoman. After the English conquest of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, a small number of Dutch families moved to the southern colonies, particularly Maryland. Many of these emigrés were carpenters, such as Matthias Peterson, Peter Mills, and Thomas Turner, whose naturalization records specify their Dutch origins. Turner reported that his birthplace was “Middleborough, Province of Zealand” when he applied for naturalization in Anne Arundel County in 1671. Also among the carpenters who emigrated from New Netherland to Maryland were Remy Lefer, Nicholas Fontaine, and Joseph Deserne, whose names appear more French than Dutch. From the outset, New Netherland was an ethnic polyglot of Dutch, Swedes, Finns, Germans, Walloons, and French Huguenots. The 1681 inventory of Dutch carpenter Henricke Cloystockfish lists tools appropriate for his trade, including nine old chisels, ten caulking irons, seven old planes, three old hammers, one old axe, three old adzes, two old saws, “an old Chest with some old Tooles,” and “a parcell of old Dutch Bookes.”[12]

Less than two dozen pieces of seventeenth-century Chesapeake furniture are known, but nearly a quarter have stylistic and structural features more closely associated with the Dutch-influenced furniture of New York than with the predominantly British-influenced products of New England. The clothes cupboard illustrated in figure 6 provides the strongest evidence of Dutch influence on early Chesapeake joinery. Although its walnut primary wood, fielded panels, and dovetailed construction caused scholars to date the cupboard between 1690 and 1710, Dutch-trained joiners in the Chesapeake produced “close Cupboard” forms by the 1660s. Documentary and physical evidence strongly suggest that this piece was made in Virginia during the third quarter of the seventeenth century.[13]

Although the seventeenth century is generally considered the age of oak furniture, Virginia walnut was shipped to England for “waynscot, tables, cubbordes, chairs and stooles” during the 1630s. The joiner who made the clothes cupboard used walnut for the front, canted corners, sides, moldings, and spindles, and yellow pine for the top, bottom, and back. The top and bottom boards are dovetailed to the sides, and the backboards are nailed to the top and bottom and pinned to the sides (fig. 7). Joiners in the Netherlands began using dovetail construction during the early sixteenth century.

The design of the clothes cupboard is unique. Although other colonial case pieces such as Germanic schranken and French armoires were used for storing clothes and household textiles, the form most closely associated with the clothes cupboard is the kast from Dutch-settled areas of New York and New Jersey (fig. 8). By extension, the Virginia cupboard may be interpreted as a vernacular version of the magnificent Amsterdam kast depicted in Pieter de Hooch’s, Portrait of a Family Making Music (fig. 9). At first, this comparison may seem absurd; however, both pieces employ similar frame-and-panel construction (figs. 6, 9); both rest on separate turned feet (fig. 10); both have raised panel doors (fig. 11); and both have canted corners. The kast in de Hooch’s painting has carved baroque pilasters at the corners, whereas the Virginia-made example has long, mannerist spindles.

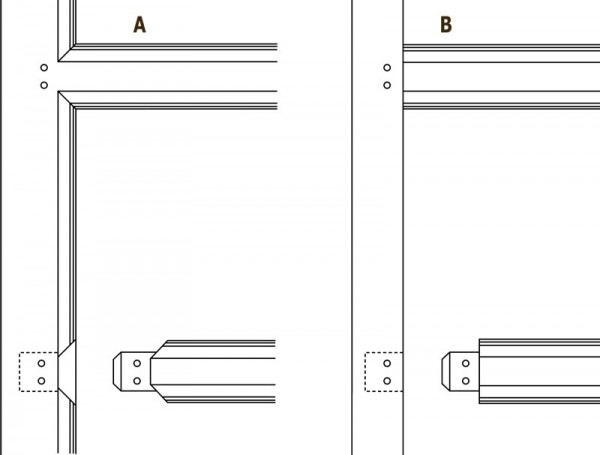

The clothes cupboard has at least four structural details associated with Dutch or Dutch colonial kasten—fielded panels, moldings run directly on the frame, mitered mortise-and-tenon joints, and dovetails. The panels on the cupboard have distinctive, concave fields that were cut with a large hollow plane, whereas those on New York kasten (fig. 8) were typically formed with a panel plane. The fielded panels on the Virginia piece, nevertheless, almost certainly emanate from a Continental tradition, since fielded panels rarely occur on English work before the 1660s or on New England work from the seventeenth century. Such panels do occur, however, on New York kasten by the middle of the seventeenth century.[14]

The panel-and-frame construction of the clothes cupboard also relates more closely to Dutch joinery practices than to English ones. As on many New York and Dutch kasten, the doors of the cupboard have directly molded stiles and rails and mitered mortise-and-tenon joints (see figs. 6, 8, 11, 12). In English panel-and-frame construction, stile and rail moldings are typically applied, or they are planed on only one of the adjoining framing members (fig. 12). As might be expected, no seventeenth-century New England furniture displays mitered mortise-and-tenon joinery. Other northern European details on the clothes cupboard are the diamond-shaped pins used to secure the mortise-and-tenon joints and backboards and the splines between the backboards (figs. 7, 13).

Most importantly, the clothes cupboard is the earliest piece of southern furniture with dovetail construction (fig. 13). In the colonies, dovetail joinery first appears on furniture associated with a small group of London-trained artisans who arrived in Boston and New Haven during the 1630s and early 1640s. In their work, and in most New England furniture of the seventeenth century, dovetailing is limited to the drawers of joined case pieces. Furniture historian Robert Trent has shown how dovetail technology could have arrived in London as early as the 1540s through the importation of chests from Danzig, Prussia, the Netherlands, Cologne, France, Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula. These chests, which featured board and dovetail construction, were favored by merchants and lesser gentry in England’s major ports. On the clothes cupboard, dovetails are used to attach the top and bottom boards to the sides. The early appearance of board and dovetail joinery on the Continent and its scarcity in Anglo-American furniture support the assertion that the clothes cupboard was made by a joiner trained in a northern European tradition.[15]

The clothes cupboard has a number of features that differentiate it from related Continental forms, such as the kast, schrank, and armoire. Its asymmetrical facade is the most obvious anomaly. The large compartment on the right is fitted on three sides with a pegboard for hanging clothes (fig. 14), and the smaller compartment on the left has two shelves for storing folded textiles (fig. 15). William Moseley’s “greate dutch Cash” may have been outfitted in a similar fashion, for it contained suits of clothes, “woolen waring apparrell,” and linens. No Continental precedent for this interior arrangement is known, although Moseley’s inventory suggests that it could be a regional adaptation.

Like the clothes cupboard, many early Chesapeake chairs (figs. 16, 17) have features that differentiate them from contemporary New England work and also link them to New York examples (fig. 18). Virginia chairs typically have turned arms that project beyond the front post rather than being tenoned into them, as on most English and New England examples. Overpassing arms are relatively common on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century chairs from Holland and France. The Chesapeake had a small Dutch and French population during the seventeenth century, but between 1700 and 1710 the French population increased dramatically owing to the emigration of Huguenot refugees to southeast Virginia. The armchair illustrated in figure 17 has another detail found on chairs from the Netherlands and France—a row of small turned finials tenoned into the crest rail. Three other Chesapeake chairs share this distinctive feature.[16]

One of the clearest manifestations of Continental influence in the Chesapeake is the stretcher table illustrated in figure 19. The table was purchased earlier this century by dealer Bessie L. Brockwell of Petersburg, Virginia, who discovered many of the surviving examples of seventeenth-century Chesapeake furniture. Made of black walnut and cedrela, a tropical hardwood probably imported from the West Indies, the table has a dovetailed frame and legs that are braced into the corners and pinned. Although the braces wedging the legs have no known parallel, some early New York City draw-bar tables have exposed dovetail frames (fig. 20). Furniture historian Peter Kenny has attributed these tables to Dutch joiners and shown how their dovetail frames relate to the base construction of contemporary New York kasten. The Virginia table could have been made by a Dutch tradesman who immigrated to the Chesapeake region after the English conquest of New Amsterdam.[17]

The most compelling evidence that Dutch styles had a lasting influence on Chesapeake furniture centers around George Hack, a Dutch physician who died in Accomack County, Virginia, in 1665, and his indentured servant John Rickards. Hack’s widow, Anna, subsequently moved to Maryland with her two sons and was granted citizenship by a special act of the colonial legislature. Maryland records describe her as “born in Amsterdam, Holland,” and her sons, George and Peter, as “born at Accomacke, Virginia.” The Hack family was granted citizenship on the same day as Augustine Herrman and his family.[18]

Although Rickards is referred to as a “carpenter” in Accomack records of 1668, the tools that were at his disposal during his indenture were more varied than that trade required. Hack’s inventory listed “1 Crosscut Saw, 2 old whipsaws, 1 rest & a file, 1 old broad ax, 1 hatchet, 1 Pr. Iron compasses, 13 plaines small & great, 1 handsaw, 3 small saws, 2 percer Stocks & 5 percer bitts, 1 glue pott, 3 gowdges, 7 Chissells & 5 gimletts, 1 hamer, 1 pr. of pincers, 1 drawinge knife & 1 coopers adds, 1 howell, 5 turning tools, 2 broken holdfasts & 1 bench hook.” The thirteen planes, turning implements, and glue pot suggest that Rickards was both a turner and a furniture joiner.[19]

In 1668, Rickards signed an indenture with Anne Boote of Accomack County, in which he agreed to make fifty-four pieces of furniture.

These presents bindeth mee John Rickards . . . to pay or cause to be paid unto Mrs. Anne Boote . . . These followinge works, Eight bedsteads, Nine tables & ten formes, five close Cupboards, five Courth Cupboards, one Courth Cupboard very handsome according to Mrs. Boote her directions, one close Cupboard also, Six Spinne wheeles, five chaire Tables, four chests this worke is to bee done by me Jno. Rickards . . . or else to forfeit one thousand lb. of Tobacco.

Mrs. Boote undoubtedly intended to sell most of Rickards’s work; however, the “very handsome” court cupboard and clothes cupboard made “according to Mrs. Boote” were probably for her personal use. The latter phrase shows how seventeenth-century patrons interacted with tradesmen and influenced the design of their household furnishings. Court cupboards and “close cupboards” like the example illustrated in figure 6 were obviously popular forms in Virginia during the third quarter of the seventeenth century.[20]

Indentures and apprenticeships clearly contributed to the persistence of Dutch furniture-making traditions in the Chesapeake. In 1673, Rickards took William Phillpott as an apprentice for the unusually short term of three years and nine months. Rickards agreed to teach Phillpott the “vocation of [the] Carpenters Trade” and furnish him with “such Carpenters Tooles as the Said Phillpott Worketh with in the time of his Servitude” at the end of his indenture. Since William Phillpott was undoubtedly a young man in 1673, it is possible that the shop tradition that began with Rickards’s indenture to Hack extended into the early eighteenth century.[21]

Clearly no Continental Europeans were more involved in the commercial and political affairs of the Chesapeake region than the Dutch. During the first quarter of the seventeenth century, they sailed to the Chesapeake to barter for tobacco. Dutch traders established permanent settlements at strategic points along the region’s waterways, and Dutch artisans immigrated to the region. Although the Dutch were gradually assimilated by the larger English population, documentary and material evidence indicates that they had a profound impact on the material life of the seventeenth-century Chesapeake region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their assistance with this article, I thank Robert Trent, Luke Beckerdite, Peter Kenny, Martha Rowe, Ronald Hurst, Jay Gaynor, and especially Frank Horton.

Appendix A

| An Inventory & appraisement of the Estate of Capt. Wm. Moseley being taken and appraised the 10th day of November 1671 by the under written who were sumoned & sworne to that purpose by vertu of an order of Court the 16th October last past as following: | |

| Vizt. | |

| In Mr. Moseley’s Study in the Garrett |

lb. tob.

|

|

|

|

| Impr. A parcell of Books Some french dutch Latten & English all att |

3000 |

| A Case of Small draws a little table & other small tries |

160

|

|

|

|

| In the Garrett |

|

| A Small parcell of tooles & Lumber |

400

|

|

|

|

| In the Chamber over her owne Roome |

|

| one feather Bead and Boulster one Rugg & blankett one Sheete a matt bead stead & bead straws |

1000

|

| one Couch a feather boulster & pillow & blankett |

200

|

| 7 Chayres, weights & scales a small looking glasse a towell frame and [illegible] |

200

|

| a little trunck and Box |

100

|

|

|

|

|

In the Porch Chamber

|

|

|

a feather bead & furniture as It Stands

|

2500

|

|

a table and foure Chayres & a little Cushion

|

300

|

|

2 truncks a Box a looking glasse a Brush & window Curtains

and a few pipes |

300

|

|

|

|

|

In the Hall Chamber

|

|

|

8 Chayres a Close stoole a small table 3 small Chushions a

Carpett & little Baskett |

860

|

|

one greate dutch trunck & what linnen is In It

|

3470

|

|

one small trunck wth linnen a scarlett wascote & tries

holland dublett |

2220

|

|

a payre of andirons a fire shovell one other small trunck

one looking glasse one spoone a small parcell of Earthen things a little frame to putt a bason on a pocket knife & a little stoole |

750

|

|

foure picktures 100; for what is in a little Closett 100

|

200

|

|

In the Hall

|

|

|

a feather bead & furniture as It Stands

|

1700

|

|

a Couch & Couch bead blankett & 2 Chushions

|

300

|

|

a side Borde & Cloath 2 Chushions a pewter bason & yoar and

several saltes & a dish |

250 |

|

a table & Carpett Six Chaires 5 Stooles

|

550

|

|

2 Chests 4 boxes a looking glasse and a Brush

|

550

|

|

a paire of Brasse andirons & Snuffers & a Brasse Branch of

Candle Sticks [illegible] |

560

|

| Six picktures a frame & a parcell of Earthen things a partison & a Baskett 600; a greate dutch Cash 500 |

1100

|

| his woolen waring aparrell |

1300

|

| a parcell of Linen |

500

|

| one old Cloaths Suite & [illegible] |

300

|

| a small parcell of Buttons & thread a small Remnant of Sewing a Capp & a paire of topps |

200 |

|

|

|

| Carried to the other side |

22,870

|

|

|

|

|

lb. tob.

|

|

|

|

|

| Brought from the other side |

22,870

|

|

|

|

| In her owne Roome |

|

| a feather bead & furniture as It Stands |

1200

|

| a trundle bead and furniture |

300

|

| a Couch and Couch bead Chusion, blankett, Cradle and what’s in It |

300

|

| a table two formes 8 Chayres & 3 stooles |

650

|

| a Chest of draws & 2 boxes |

700

|

| one pr. of Iron andirons, tongs, Slice Snuffers bellows warming pan, 2 picktures and a looking glasse Lanthorne & other triing things |

550 |

|

|

|

| In the Entry |

|

| a Chest a box a table a Safe 2 Stocks Some knives & other Lumber |

350

|

|

|

|

| Under the Stayre Case |

|

|

|

|

| a Small parcell of tooles & other Lumber |

200

|

|

|

|

| In the milke house |

|

| a table some Caskes, a parcell of trays & bowls, panns Juggs and other Earthen things & wooden trenchers |

400

|

| 204 lb. of pewter |

2500

|

|

|

|

| In the passage to the kitchen |

|

| a Shelfe of small brasse a lamp and a Lanthorne |

700

|

|

|

|

|

In the kitchen

|

|

| a parcell of Iron potts kittles Spitts and frying panns a Copper & a Brasse kettle |

1100 |

| an Iron Rack andirons pott Racks dripping panns and some Brasse things on a Shelfe an old Brasse Stewpan & an old still |

700 |

| three gunns & other Lumber |

970

|

|

|

|

| In a shead things there |

80

|

|

|

|

| Without doores |

|

| an old Cart & wheeles 2 ploughs and one sett of Irons |

400

|

| a parcell of old tooles and other Lumber |

380

|

| an old boate & Apurtenances & Canoe |

500

|

| Tables & other horse harnesse |

300

|

| about 60 head of Hoggs young & old |

6000

|

| about 18 head of Hoggs at the plantacon att lin haven bye Informacon about one year old one [illegible] |

2000 |

|

|

|

| In the Sider house |

|

| a parcell of Salt and an Iron Chayne |

600

|

| pestle and Sliceyards & Canhooke |

300

|

| one old negro man & woman |

3000

|

| one young negro man & woman |

10,000

|

| one mollatto woman 5000; one negro girle about 3 years 1800 |

6800

|

| one negro boy about 1 _ yeares old |

2000

|

| a Boy about [illegible] yeares old sonne of the mollatto woman her mother being a negro woman |

2600 |

| an English man servant about 2 yeares to serve |

1000

|

| a Signett Ring and a small parcell of Riband |

00

|

| a little old Sash |

20

|

|

|

|

| Carried to the other side |

lbs. 68,770

|

|

|

|

| Brought from the other side |

68,770

|

|

|

|

| 5 lbs. and an ounce of Silver being Exactly weighed wth. brasse weights & Scales a hatt and Silver hatband which Shee Informed us Shee had disposed of |

00 |

| Mrs. Moseleys Side Sadle & furniture |

300

|

|

lbs. 69,270

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wee the Subscribers being sumoned & sworne appraisors of the Estate of Capt. Wm. Moseley decd. have accordingly to the best of our Judgments appraised what was Brought unto us as upon this Inventory upwards which Amounts unto the Some of Sixty nyne thousand two hundred & seventy pounds of tob. & Caske besides the five lbs. & one ounce of Plate which wee did see weighed in with scales which wee have here unto Subscribed this 11th day of November 1671

|

|

|

|

|

| Tho: Bridges Tho: viz. Jun. Will Hancock Henry Spratt |

|

|

|

|

| debts due to the Estate |

|

| Impr. Capt. Carvers note |

190

|

| Tho: Cartwrites bill |

383

|

| James Jeslands bill |

400

|

| Wm. Boultons bill |

84

|

| Humphry Smiths bill |

110

|

| Capt. Jn. Custis debt |

5000

|

|

6167

|

|

|

|

|

| Wm. Moseleys bill of gallaway being a desperate debt |

650

|

|

|

|

| a list of the Horses Sheepe & Cattle belonging to the Estate of Capt. Wm. Moseley decd. vizt. | |

| One stone horse about 5 yeares old, two old mares one young mare one blind mare about 2 yeares old, a yearling horse | |

|

|

|

| Sheepe |

|

| five yewes, one Ram one weather |

|

|

|

|

| Cattle |

|

|

18 young Cows, 5 very old, 5 hayfers 3 yeare old Each, two hayfers 2 yeare old, 6 yearling hayfers, somme Steeres 5 yeare old, 3 Steeres foure yeare old, six steere 3 yeare old, one bull foure yeare old, five yearling steers, two steers Calves of this years fall

|

|

|

|

|

| Att Lin haven plantacon |

|

| foure Cows and a bull Calfe 5 yearling hayfers & one yearling Steere | |

|

|

|

| Sworne to in open Court by Mrs. Mary Moseley to bee a true Inventory of Capt. Wm. Moseley’s Estate the Crop, one Bead & her wearing Cloathes Excepted this 15th November 1671 Wm. Porter Court Clerk |

|

|

|

|

| Source: Norfolk County, Va., Wills and Deeds, bk. E, 1666–1675, folios 105–7. |

|

Appendix B

| Dutch Objects in Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake Wills and Inventories | ||

| “one Dutch cupboard” |

Northampton County, Va |

Will of Edward Dowglas, November 12, 1657 |

| “greate Dutch Trunk [with] Under Drawers" |

St. Mary’s County, Md. |

Case of Simon Overzee, Maryland Archives, 41, 1658 |

| "Hgh German and Dutch Books" | Accomack County, Va. |

Inventory of George Hack, May 22, 1665 |

| “One Round Dutch Table" |

Unspecified county, Md. |

Inventory of Hugh Stanley, October 1, 1669 |

| “a parcell of Books some french, dutch, Latten & English . . . one greate dutch trunck . . . one greate Dutch Cash” |

Norfolk County, Va. |

Inventory of William Moseley, 1671 |

| “my great Dutch chest” |

Accomack County, Va. |

Will of John Fawsett, August 15, 1673 |

| “Parcell of Dutch earthen ware” | Anne Arundel County, Md. |

Inventory of William Neale, March 13, 1675/6 |

| “a map of Amsterdam . . . 1dutch painted cupboard” |

St. Mary’s County, Md. |

Inventory of Richard and Elizabeth Moy, February 14, 1675/6 |

| “6 turn’d dutch chaires” |

Cecil County, Md. |

Inventory of John Carr, September 16, 1676 |

| “parcell of old Dutch Bookes” |

Unspecified county, Md. |

Inventory of Henricke Cloystockfish, May 17, 1681 |

| "one Dutch cubert & cloth" |

Norfolk County, Va. |

Inventory of Adam Keeling, March 19, 1683/4 |

| “the greate Dutch presse... in the dineinge Roome” | Northampton County, Va. |

Will of John Custis, March 18, 1691/2 |

| “a Dutch Chest” | Accomack County, Va. | Will of Owen Collonie, September 19, 1693 |

| “2 du[t]ch painted boxes” |

Essex County, Va. |

Inventory of Francis Marriner, February 22, 1693/4 |

| a Dutch chest . . . one Dutch case with twelve glass bottles . . . a Dutch table . . . foure leather Dutch chaires” |

Northampton County, Va. |

Will of Robert Fletcher, November 29, 1695 |

| “One Du[t]ch Table” |

Isle of Wight County, Va. |

Inventory of Thomas Taberer, February 4, 1694/5 |

| “Iron bound dutch box” |

Isle of Wight County,. Va. |

Inventory of Nicholas Smith, July 23, 1696 |

| “a pokomoke wheel in the Dutch fashion . . . a Round Dutch table . . . an old Dutch cupboard” |

Accomack County, Va. |

Inventory of Thomas Teackle, August 18, 1696 |

| “Parcell of Dutch Earthen Ware” |

Isle of Wight County, Va. |

Inventory of Capt. James Benn, May 1, 1697 |

| Source: Artisan files, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. | ||

Appendix C

| Dutch and Other Continental Tradesmen in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake Region | ||

| “eight Dutchmen and Poles” | glass makers |

James City County, Va., 1608 |

| “Derrick the Dutch Carpenter” | carpenter and shipwright |

James City County, Va., 1627 |

| Thomas Turner |

carpenter |

Anne Arundel County, Md., 1653 |

| Bartholomew Engelbretson |

carpenter and cooper |

Lower Norfolk County, Va., 1659 |

| Augustin Herrman | surveyor | Cecil County, Md., 1661 |

| Nicholas Fountaine |

carpenter and cooper |

Calvert County, Md., 1665–1703 |

| Peter Mills |

carpenter |

St. Mary’s County, Md., 1667–1685 |

| Matthias Peterson |

carpenter |

Talbot County, Md., 1671–1686 |

| Cornelius Vorhoofe |

carpenter and shipwright |

Accomack County, Va., 1668 |

| Hans DeRinge |

carpenter |

Baltimore County, Md., 1672 |

| Michael Paulus |

carpenter |

Talbot County, Vanderford Md., 1672–1692 |

| Joseph Diserne |

carpenter |

York County, Va., 1679–1704 |

| Henricke Cloystockfish |

carpenter and shipwright |

Unspecified county, Md., 1681 |

| Remy Lefer |

carpenter |

St. Mary’s County, Md., 1688 |

| Source: Artisan files, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. | ||

Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), pp. 53–57. C. A. Weslager, The Swedes and the Dutch at New Castle (New York: Bart, 1987), pp. 1–24

Charlotte Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), pp. 13, 19–25. For the reference to Sir Thomas Dale, see p. 19.

John R. Pagan, “Dutch Maritime and Commercial Activity in Mid-Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 90, no. 4 (October 1982): 485–501. Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics, p. 20. David Peterson DeVries, “Voyages from Holland to America, A. D. 1632 to 1644,” translated by Henry C. Murphy, Collections of the New York Historical Society, second series, vol. 3, part 1 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1857), pp. 32–37, 74–78, 123–27.

Pagan, “Dutch Maritime and Commercial Activity,” pp. 485–501. See also, Jan Kupp, “Dutch Notarial Acts Relating to the Tobacco Trade in Virginia, 1608–1653,” William and Mary Quarterly 30, no. 4 (October 1973): 653–55.

Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics, p. 20. “Richard Ingle in Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine 1, no. 2 (June 1906): 131–33, 140. “Petition of certain Dutch Merchants to the States General,” in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Procured in Holland, England and France, edited by E. B. O’Callaghan (Albany, N.Y.: Weed, Parsons, and Company, 1856), pp. 436–37.

Pagan, “Dutch Maritime and Commercial Activity,” pp. 493–501. Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics, p. 21. “Denization of Augustine Herman,” Maryland Historical Magazine 3, no. 2 (June 1908): 170; Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics, p. 24.

For the connection between Dutch trade and Chinese export porcelain in Virginia, see Julia B. Curtis, “Chinese Ceramics and the Dutch Connection in Early Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” in Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (Amsterdam: Mededelingenblad, 1985), pp. 6–13; and Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics, pp. 73–80. Information on Kicotan is from personal communication with William Pittman, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. John L. Cotter, Archaeological Excavations at Jamestown (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Archeological Research Series Number Four, 1958), pp. 172, 185, 201–86. James Deetz, Flowerdew Hundred: The Archaeology of a Virginia Plantation, 1614–1864 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), pp. 43–44. Henry M. Miller, A Search for the “Citty of Saint Maries” (St. Mary’s City, Md.: St. Mary’s City Commission, 1983), p. 82. Al Luckenbach, Providence 1649: The History and Archaeology of Anne Arundel County Maryland’s First European Settlement (Annapolis, Md.: Maryland State Archives and Maryland Historical Trust, 1995), p. 2.

Inventory of Captain William Moseley, October 16, 1671, Norfolk County, Va., Wills, Deeds, &c., bk. E, 1666–1675, folios 105–7. Unless otherwise noted, all primary sources cited in this article are from transcriptions in the artisan and personnel files at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereinafter cited as MESDA), Winston-Salem, North Carolina. For a discussion of the Dutch kast, see T. H. Lunsingh Scheurleer, “The Dutch and Their Homes in the Seventeenth Century,” in Arts of the Anglo-American Community in the Seventeenth Century, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Winterthur Museum, 1975), pp. 15–29; Reinier Baarsen, Dutch Furniture 1600–1800 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1993), pp. 8–9, 14–15, 24–25, 34–35; and Peter M. Kenny, Frances Gruber Safford, and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten: The Dutch-Style Cupboards of New York and New Jersey 1650–1800 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), pp. 1–10.

Gary Wheeler Stone, “St. John’s: Archaeological Questions and Answers,” Maryland Historical Magazine 69, no. 2 (summer 1974): 157–58.

Homer Eaton Keyes, “Notes on American Wainscot Chairs,” Antiques 16, no. 6 (June 1930): 523. Homer Eaton Keyes, “Riddles & Replies,” Antiques 24, no. 9 (October 1938): 216.

John Smith, The Complete Works of Captain John Smith, edited by Philip L. Barbour, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1950), 2:180–200. William W. Hening, The Statutes at Large; being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia (New York, 1823), p. 115. Minutes of the Council and General Court, James City County, Va., July 2, 1627. Jeffrey A. Wyand and Florence L. Wyand, Colonial Maryland Naturalizations (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1986), pp. 2–6. For more on the ethnic origins of New York’s artisan community, see Kenny, Safford, and Vincent, American Kasten, pp. 14–15; and Neil D. Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in Colonial New York,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1995), passim. Inventory of Henricke Cloystockfish, May 17, 1681, Maryland Prerogative Court, Inventories and Accounts, vol. 7, 1680–1682, folio 11.

The clothes cupboard was discovered in eastern Virginia by Richmond dealer J. K. Beard. In 1940, Frank L. Horton purchased it from Beard’s estate. For other interpretations of this clothes cupboard, see James R. and Marilyn S. Melchor, “Analysis of an Enigma,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 12, no. 1 (May 1986): 1–18; and John Bivins and Forsyth Alexander, The Regional Arts of the Early South: A Sampling from the Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for MESDA, 1991), p. 23.

Kenny, Safford, and Vincent, American Kasten, pp. 10–15.

The London joiners who immigrated to Boston included Ralph Mason (1635), John Davis (1635), and Henry Messinger (1640). The London joiners who immigrated to New Haven included William Russell and William Gibbons (1640). For more on these men and the origins of dovetail construction in London and New England, see Benno M. Forman, “The Chest of Drawers in America, 1635–1730: The Origins of the Joined Chest of Drawers,” Winterthur Portfolio 20, no. 1 (spring 1985): 9–14; Robert F. Trent, “The Chest of Drawers in America, 1635–1730: A Postscript,” Winterthur Portfolio 20, no. 1 (spring 1985): 31–48; Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1988), p. 42; Benno M. Forman, “Urban Aspects of Massachusetts Furniture in the Late Seventeenth Century,” in Country Cabinetwork and Simple City Furniture, edited by John D. Morse (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for Winterthur Museum, 1970), pp. 12–16; Robert F. Trent, “New England Joinery and Turning before 1700,” in New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, 3 vols. (Boston: the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1982), pp. 501–9; 522–26, nos. 481, 482; and Robert F. Trent, “Recent Discoveries in Early New England Furniture,” lecture at the 1997 Antiques Forum, Williamsburg, Virginia. The Savell shop of Braintree, Massachusetts, also used dovetails to join drawer sides to drawer fronts (Peter Follansbee and John D. Alexander, “Seventeenth-Century Joinery from Braintree, Massachusetts: The Savell Shop Tradition,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996], pp. 94–96).

Bivins and Alexander, Regional Arts of the Early South, p. 21. Roderic H. Blackburn and Ruth Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America 1609–1776 (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1988), p. 175. John T. Kirk, American Furniture in the British Tradition to 1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), p. 236, fig. 768. I am grateful to Ronald Hurst for bringing this illustration to my attention.

For the history of this table, see accession files, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Peter M. Kenny, “Flat Gates, Draw Bars, Twists, and Urns: New York’s Distinctive, Early Baroque Oval Tables with Falling Leaves,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 113–14.

Inventory of George Hack, May 22, 1665, Accomack County, Va., Deeds and Wills, 1664–1671, folio 28a. Wyand, “Naturalizations Granted by Enactment of Private Laws,” Colonial Maryland Naturalizations, p. 5.

Inventory of George Hack. For an excellent discussion of early woodworking tools, see Jay Gaynor, “‘Tooles of all sorts to worke’: A Brief Look at Trade Tools in 17th-Century Virginia,” in The Archaeology of 17th-Century Virginia, edited by Theodore R. Reinhart and Dennis Pogue (Richmond, Va.: Archeological Society of Virginia, Special Publication no. 30, 1993), pp. 311–56.