Card table, probably New York City, ca. 1801. Mahogany with white pine and walnut. H. 29 3/16", W. 36", D. 17 1/8" (closed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Henry Francis du Pont.) This table is one of a pair.

Detail of the horizontal laminations of the rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 1.

Card table, probably New York City, 1795–1805. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 28 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.) The top of this table is unusual in being made from solid wood. The name “Edward Rogers” is inscribed in chalk on the underside of the fixed leaf.

Detail of the vertically laminated rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail showing the kerfed and laminated corners of a card table attributed to Duncan Phyfe, New York City, 1830–1840. (Courtesy, Northeast Auctions.)

John T. Dolan, card table, New York City, 1809–1813. Mahogany with white pine and cherry. H. 30 1/8", W. 35 3/4", D. 36 5/16" (open). (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.) This triple elliptic table bears Dolan’s label.

Detail of the plum-pudding mahogany veneer on the top of the card table illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bed steps, New York City, 1815–1830. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 24 1/2", W. 19", D. 24". (Courtesy, Boscobel Restoration; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the “slipped” rear edge of the upper leaf of the card table illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The joint between the one-quarter-inch veneer and core is visible inside the mortise.

Detail showing the “slipped” top edge of a veneered drawer front. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing splits along the glue joints of the upper leaf of the card table illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of an alignment tenon and mortise on the rear edge of the top of the card table illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, New York City, 1805–1815. Mahogany with cherry, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 28 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 3/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Boscobel Restoration; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the operation of flies linked to the swinging rear legs of the card table illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, New York City, 1815–1825. Mahogany with white pine. H. 30", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Boscobel Restoration; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The swivel top rotates, exposing a well.

Card table designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and possibly made by Thomas Wetherill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1811. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 17" (closed). (Courtesy, Private Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table has a swivel top.

George Wright, console table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1811. White pine. H. 29 1/2", W. 73", D. 23 1/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of the Associate Committee of Women, 1913.) This early photograph shows the console table below a later looking glass and frame.

Charles Honoré Lannuier, card table, New York City, 1810–1815. Mahogany with mahogany. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 18 1/8" (closed). (Courtesy, White House Historical Association; photo, Bruce White.) This swivel-top table bears Lannuier’s label and is one of a pair.

Joseph Brauwers, card table, New York City, 1814 or later. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 29", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of David Stockwell.) This table bears Brauwers’s label.

Detail showing the construction of a canted corner on the card table illustrated in fig. 19.

Card table, probably New York City, 1815–1825. Mahogany with white pine, tulip poplar, and cherry. H. 29 7/8", W. 36", D. 17 3/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont.)

Detail showing the laminated construction of a canted corner of the card table illustrated in fig. 21.

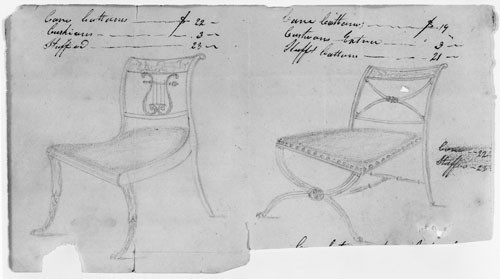

Sketches of a lyre-back chair and a Grecian cross-front chair attributed to Duncan Phyfe, New York City, ca. 1815. Pencil and ink on paper. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

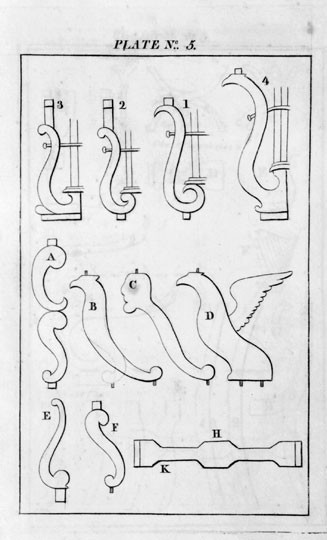

Plate 5 from the 1817 New York Book of Prices. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

Card table, New York City, 1815–1825. Mahogany and ebony with white pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont.)

Detail of the lapped block with triangular in-fills on the card table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Duncan Phyfe, card table, New York City, 1816. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 30", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Private collection; photo courtesy Robert Mussey Associates.)

Detail showing the attachment of colonnettes to two crossbars dovetailed into the frame of the card table illustrated in fig. 27.

Charles Honoré Lannuier, card table, New York City, 1817. Mahogany with ash, tulip poplar, white pine, cherry, and basswood. H. 31 1/8", W. 36", D. 17 7/8" (closed). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Michael Allison, card table, New York City, 1817 or later. Mahogany with tulip poplar and cherry. H. 31", W. 37 3/4", D. 18 1/2" (closed). (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy.)

Charles Honoré Lannuier, card table, New York City, 1815–1819. Mahogany with white pine, tulip poplar, and cherry. H. 29 3/4", W. 36", D. 17" (closed). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This table bears Lannuier’s third label.

John Budd, card table, New York City, 1817 or later. Mahogany with white pine. H. 29", W. 35*", D. 17 3/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Daughters of the American Revolution Museum.) This table bears Budd’s 1817 label.

Card table, probably New York City, 1815–1820. Mahogany with white pine, cherry, and tulip poplar. H. 29", W. 36", D. 18 1/8" (closed). (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Card table, probably New York City, 1815–1820. Mahogany with white pine. H. 31", W. 37 3/8", D. 20" (closed). (Courtesy, Private Collection; photo, Dirk Baker.)

Michael Allison, Pembroke table, New York City. Mahogany with white pine and ash. H. 30", W. 21 5/8" (closed), D. 37 13/16".

(Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York, gift of Estelle de Peyster in memory of Julia de Peyster Martin.)

Pembroke table, probably New York City, 1810–1820. Mahogany with ash, maple, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 30", W. 22 3/8" (closed), D. 35 3/4". (Courtesy, Boscobel Restoration.)

Card table, probably New York City, 1815–1825. Mahogany with white pine. H. 29 1/2", W. 35 1/2", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Duncan Phyfe, card table, New York City, 1820 or later. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum.) This table bears Phyfe’s August 1820 label.

Duncan Phyfe, card table, New York City, 1820 or later. Mahogany with unidentified secondary wood. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Israel Sack, Inc.) This table bears Phyfe’s August 1820 label.

Duncan Phyfe, card table, New York City, 1820 or later. Mahogany with unidentified secondary wood. H. 31 1/2", W. 36", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Card tables demonstrate great range and expression in design construction, and materials despite their functional simplicity. Because large numbers of them survive, they invite comparisons and hold the promise of documentation to maker, place, and/or time of manufacture. This article surveys the development of card tables in New York during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, a period marked by New York’s ascendancy as an urban community and, more specifically, as a leading center of furniture making. By 1805 David Longworth reported in his Almanack that the city supported sixty-six cabinetmakers, nineteen chair makers, fifteen carvers and gilders, and nine joiners. The number of furniture-making artisans increased exponentially over the next few decades. At about this time, New York surpassed Philadelphia as the largest city in the United States. New York artisans amalgamated designs and technical innovations and spread them throughout the United States via a substantial export trade.[1]

Despite the great numbers of early nineteenth-century card tables and other furniture forms ascribed to New York City artisans, no federal card tables documented to have been made before 1800 have come to light. New York furniture makers’ price books published in 1796 and 1802 help fill this void, but they must be interpreted with care. Created to establish labor prices between journeymen and shop masters for all kinds of tasks, the first editions drew heavily from London prototypes. As furniture historian Patricia Kane observed, The New-York Book of Prices for Cabinet & Chair Work, agreed upon by the Employers (1802) introduced a few local preferences and omitted other entries from the London books. This trend toward more representative descriptions continued in the New York price books of 1810 and 1817, as well as in interim supplements. Given this cautionary note, the price books nonetheless document the dominant card table forms, which compare favorably with anonymous survivals that may be identified as New York products with reasonable assurance based on favorable comparisons of their physical features with other documented New York furniture. Card table headings in the 1802 price list itemize “square” (rectangular in plan), “circular” (half-round or demilune), and “ovalo corner” (inset quarter-round corner) forms, each described as either solid or veneered in reference to construction of the hinged tops.[2]

Inlay patterns and techniques, the presence of églomisé, and the five-leg design combine to suggest that the engaging and provocative card table illustrated in figure 1 was made in New York City. Its central églomisé panel depicts an eagle and shield bearing the names of Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. A tie between those men in the Electoral College left the outcome of the presidential race of 1800 in doubt until the House of Representatives resolved the matter in Jefferson’s favor on February 17, 1801. Given the contentiousness of national politics, the card table likely commemorates the start of Jefferson’s administration and was probably made in early 1801. It is rectangular with ovolo front corners, a popular table and sideboard treatment also called “sash” in period manuscripts. The curved portion of the frame is made of three horizontal layers of white pine glued together with the grain oriented at oblique angles to the adjoining layers (fig. 2). This general technique was used on all sorts of curved surfaces, such as the popular half-round table frame represented by the New York card table illustrated in figure 3. When curved rail sections joined straight sections, as in ovolo card tables, just the curved sections were laminated and usually glued and screwed to the boards of the straight sections. Some secondary woods are difficult to identify, but white pine predominates. Although the thickness of individual laminates and the consequent number of layers varied, the result did not. Lamination produced a strong shape that resisted warping and splitting along the “short grain.” A few New York card tables of this period, including that shown in figure 3, had round corners constructed of four or five vertically laminated boards, which resemble modern plywood (fig. 4). Another technique, associated with Duncan Phyfe’s work of circa 1820 and later, used two vertically laminated boards, each slit with saw cuts, or “kerfs,” about every half inch, then bent to shape and saturated with glue (fig. 5). Still other techniques, such as single kerfed boards bent to shape and backed with canvas, were used at the time but are not associated with New York tables.[3]

One of the more recognizable features of New York federal card tables is the fifth leg, hinged to the left side of the rear rail so that it can swing out to support the folding table leaf. Most American card tables, including a few New York examples, have four legs, one of which was also hinged to support the folding top. Reasons for this regional preference are unclear. Any advantage in stability gained by five legs was diminished by the unbalanced appearance of the extra leg in the closed position. A few New York card tables were made with a sixth leg on the right side, but on some examples this additional leg was fixed. This resolution seems only to have increased cost and complicated use, since sitters had to contend with yet another leg. Regardless, the fifth leg was a well-established New York tradition, having been the norm in eighteenth-century cabriole-leg card tables. The 1802 New York price book described basic card table forms as having “four fast legs, and one fly leg.” This wording clarified the 1796 New York price book entry that specified “one fly foot, square edge to the top, four plain legs, all solid,” which left unresolved whether the fly leg was one of or in addition to the four plain legs. The 1802 wording carried through the 1810 and 1817 New York price book editions. In contrast, the Philadelphia Journeymen Cabinet and Chair-Makers’ Book of Prices (1811) called for only three fixed and one swing leg.[4]

The 1802 price list distinguished veneered from solid card tables by noting “three joints in each top; clamp’d and veneer’d; the edges cross or long banded.” All table frames that incorporated curves were veneered, regardless of how the top leaves were constructed. The 1810 New York price book listing for “an elliptic veneered card table,” a new and typically New York shape, is slightly more descriptive and affords a convenient example for detailed discussion of construction features: “the rail veneered, a bead or band on the lower edge; three joints in each top, and clamp’d slip’d on the back edges, and veneered on three sides, or the inside lip’d for cloth, the edges banded.” The elliptic shape of the top and conforming frame differed from the simpler circular or half-round shape, which had a constant radius. Double and triple elliptic alternatives introduced multiple curves (fig. 6). All of these card table forms had conforming curved frame rails constructed of two or more laminates, three and four layers being most common. However complex its shape, the table frame was always veneered. Veneers were integral to ornamental schemes, but they also masked all of the different construction techniques and materials. Veneered frames ended in a “bead or band on the lower edge,” as noted in the price-book description. Beads were strips of wood applied to the underside of the frame with a projecting half-round profile (cock bead) that marked the bottom of the frieze and protected the edge of the veneer from damage and helped prevent peeling. Some makers used a narrow strip of cross-banding rather than a bead (fig. 6), but the former was purely decorative and afforded almost no protection for the rail veneer. Typically, the banding was carried across the solid mahogany legs as well.[5]

Unlike the solid tops of card tables made elsewhere in the United States, New York tops were typically veneered on a solid core of secondary wood. The 1810 price book called for veneer “on three sides,” namely the top surface visible when the table was closed and the two inside surfaces visible when open. Many makers used brilliant crotch veneer for the top and less figured cuts of similar color and character for the interior surfaces. Tables veneered with matching pieces of plum-pudding mahogany or other exotically figured woods were exceptional (fig. 7). Relatively few New York card tables had broadcloth or leather on the inside surfaces, even though The New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (1810) indicated that “inside[s] lip’d for cloth” represented no additional cost.[6]

Some New York card tables have unvarnished mahogany veneers on the undersides of the fixed table leaf. The New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (1817) included a special notation in the introduction that described this practice as “veneering under side of card table beds.” A set of New York neoclassical bed steps displays similar veneering (fig. 8). The inner veneers would have been visible only when the sliding steps were removed completely in order to clean the chamber seat. Interior veneers may have been intended to reduce the possibility of warping, a concern that Thomas Sheraton raised in his Cabinet Dictionary of 1803. Warped sides would have restricted the sliding movement of steps, just as a warped fixed leaf would have made the top of a card table uneven and unsightly. However, card tables that combine underside veneers with cloth or leather playing surfaces complicate this interpretation.[7]

In New York, the standard method for constructing the tops of card tables was to frame the leaves using secondary woods and to cover the cores entirely with mahogany veneers and banding. As specified in the price books, the front and side edges of each leaf were cross-banded, an application that easily conformed to curves and—more important—hid all the white pine edges and framing joints. The back edge was sometimes not worked, exposing the sandwich of veneers and secondary wood, but it was usually covered with a thin strip of mahogany, typically about one-quarter-inch thick but sometimes only the thickness of the veneer (fig. 9). Contemporary price books described this practice as “slip’d on the back edges.” The origin of this terminology is obscure, but it likely derived from a slip of wood. The tops of mahogany-veneered drawer fronts of all kinds were also routinely slipped with mahogany to disguise the white pine cores (fig. 10). The 1802 price list used that term along with “long banding” to denote veneers laid along tabletop edges with the grain “long,” or parallel, in contrast to the more common alternative of cross-banding, in which the grain lay perpendicular to the core wood.[8]

Slipped back edges of tabletops give the impression that the leaves were veneered on solid mahogany cores. Such encasing obscures much evidence of construction, but the unveneered undersides of fixed leaves on some New York tables as well as small but consistent clues elsewhere are telling. Exposed undersides show that cores were made of two, three, or four longitudinal white pine boards glued edge to edge. Although evidence is hidden, these joints are probably simple butt joints, as in many late eighteenth-century tabletops and chest tops made throughout America of walnut, cherry, and other primary woods. Use of single, full-width pine boards in New York tabletops was very rare. Battens, called “clamps” in the price books, secured each end by tongue-and-groove joints. Tenons or other joining techniques may also have been used, but none has yet been recorded among the relatively few examples where these joints are exposed. Because the grain of the battens was oriented perpendicular to the other core boards, battens countered warping and protected end grain from splitting and fracturing, just as they did in the lids of slant-top desks. In shaped card-table tops, notably double- or triple-elliptic varieties, the battens were angled so that the multiple-curve cuts were taken out of the single board. Occasionally, the battens of tabletops were made of mahogany in combination with white pine longitudinal boards. Mahogany is a dense, hard wood that resists warping and can maintain a more stable edge profile than conifers and other secondary woods. Its use in these hidden areas indicates a commendable level of concern for durability on the part of the furniture maker.[9]

For table leaves completely encased by veneers and banding, the most obvious evidence of construction lies in patterns of splits in the large sheets of veneer. Shrinkage of the boards within the core, combined with good adhesion of the veneer, resulted in consistent splitting along the seams (fig. 11). These splits occur in the middle of the leaves but do not extend to the edges because they do not pass over the cross grain of the clamps at each end. Moreover, most splits do not follow grain patterns in the mahogany veneer, responding instead to the movement of the core woods underneath. Types of woods used in the top leaf must be extrapolated from evidence on the underside of the fixed leaf, which is usually white pine.[10]

Entries for veneered card tables in the 1802 and subsequent New York price lists also called for “three joints in each top,” a requirement omitted in descriptions of solid card tables. Contemporary artisans must have understood this terminology, but for modern students, reference to the 1796 price list is helpful. This early publication specifies “glueing up tops, either solid or to veneer on, at per joint, 0.0.3,” confirming that the “three joints in each top” were glue joints between the boards. Thomas Sheraton’s Drawing Book (1793) advised makers to “rip up dry deal, or faulty mahogany, into four inch widths, and joint them up.” Four four-inch boards yielded three joints and approximated the width of most tabletops. The battens or clamps, which were listed separately in the New York price books, represented additional glue joints, as did the slipped back edge. Despite the unambiguous language in these documents, examination of surviving New York card tables confirms variation in the numbers of joints between the longitudinal boards—ranging from none (a full-width board) to the requisite three joints for a four-board top. In practical terms, the price list provision merely established a norm.[11]

American card tables had long been made with mortise-and-tenons set into the back edges of tops to align the leaves in the open position. All New York tables beginning in the 1790s appear to have at least one alignment tenon—called a “rear leaf-edge tenon” in other studies—and some have as many as four (fig. 12). The 1817 New York price list addressed this feature with an introductory note that specified “Card table tops to start with two mortises and tongues.” Here again, the price list offered only a general guideline that was probably ignored as often as it was followed. Lack of consistency in the numbers of alignment tenons extended to their placement on either the folding or the fixed leaf. In two nearly identical card tables (Winterthur Museum), one has a single alignment tenon on the fixed leaf whereas the other has two tenons on the hinged leaf. Still other tables of this and similar design (suggesting roughly similar times of manufacture) have the targeted number of three tenons. On a five-legged table, the two outside tenons are on the fixed leaf whereas the center tenon is on the hinged leaf.[12]

The use of white pine as the dominant secondary wood in the tops of New York card tables defines a regional practice, but the mere presence of that wood does not readily distinguish New York work from that of several other furniture-making centers, since white pine was used extensively throughout the Northeast and elsewhere. Woods used for the rear swing or “fly” rails are more diagnostic. Swing rails, attached by a wood hinge to a stationary half (which in turn was attached to an inner fixed rail, often of white pine or similar wood), received appreciable use and wear and were often made of stronger woods. Most New York outer rear rails were made of cherry or maple. In contrast, New England swing rails were commonly made of birch, maple, or white pine, and those in Philadelphia and farther south were made of oak, ash, or yellow pine.[13]

New York furniture makers boldly combined a double- or triple-elliptic card-table top with a pillar-and-claw base to produce a distinctive card table with a narrow, sometimes absent, frame (fig. 13). Aesthetics aside, the most significant design problem was to support the hinged top without the benefit of a swinging leg. Part of the solution was to use a pair of small brackets, called flies, which were attached to the rear rail with wood hinges—a support system already in use for Pembroke tables. A second aspect of the problem concerned the center of gravity, which shifted when the folding top was opened. Without a swing leg to compensate, the table would fall over in the direction of the cantilevered and weighty hinged leaf. This matter was resolved in pillar-and-claw bases by hinging the two rear feet so that they pivoted backward, thereby reconfiguring the stance of the tripod base to hold the open tabletop in balance (fig. 14). The 1810 New York price book provides the first American evidence of these “mechanical” tables. It described the complex action simply as “three claws, two of ditto to turn out with the joint rail.” As constructed, each fly at the back rail was linked by a system of metal rods running through the pillar to the rear legs, which swung back a few inches. This modest adjustment worked, but any additional weight added to the hinged leaf—such as a stack of books or tray with a tea or coffee service—endangered the balance of the table. Within a few years, card tables with folding tops that swiveled replaced these aesthetically elegant but functionally awkward tables.[14]

Swivel tops solved the balance problem associated with mechanical pillar-and-claw card tables (fig. 15). The pair of hinged tops turned ninety degrees on an off-center axis so that when open, the two leaves remained centered on the table frame and over the central support. Because there was no change in the center of gravity, legs could be fixed, freeing cabinetmakers to address matters of appearance without compromising stability. The first use of a swivel top in America may be in the card table designed by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe as part of a larger suite of drawing room seating and tables made for a house he designed and had built for William Waln of Philadelphia (fig. 16). Latrobe first mentioned the suite in an August 26, 1808, letter in which he complained to Waln that he had ordered “another pattern” to replace the first attempt at realizing his chair design, which he dismissed as “the ugliest thing I ever saw.” In a letter of September 8, 1809, Latrobe informed Dolley Madison, for whom he was also designing seating furniture, that the Waln drawing room “will not be furnished this winter.” Furniture historians have always assumed that the Waln suite predated the Madison furniture, but this reference to delay suggests that it may not have been completed before 1810. A painted console table inscribed “Made for W. Waln . . . By Geo G Wright whilst foreman for Mr J. B. Barry & Son . . . October 10th 1811” provides a further cautionary note (fig. 17). Although the relation of this object to the painted tables and chairs still awaits resolution, the console table was clearly made for Waln’s new house if not for the same room as the Latrobe furniture.[15]

Dating the Waln card table 1810 or 1811 places it in the vanguard of design for swivel-top card tables. One of the earliest documentary references to this form is in an 1810 bill from English furniture maker George Oakley, which lists “a calamander wood circular loo table upon pedestal and claws.” The following year, The London Cabinet-Makers’ Union Book of Prices described card-table tops “made to turn around on an iron center, fix’d to a cross rail.” Significantly, swivel tops are not mentioned in either the 1805 London Supplement to the Cabinet-Makers’ Union Book of Prices or the 1797 London Prices of Cabinet Work. The French-trained New York cabinetmaker, or “ebenist,” Charles Honoré Lannuier made two different swivel-top card tables and marked them with his second label, which furniture scholars have dated between 1805 and 1812 or later, while acknowledging the need for conjecture (fig. 18).[16]

The early Latrobe and Lannuier card tables notwithstanding, the date of 1810 (and sometimes 1805) commonly used to mark the beginning of American swivel-top card tables is too early. A large and diverse body of evidence suggests that production was delayed for at least a few years. Swivel tops were not mentioned in the seventy-two-page 1810 New York price list. An undated twelve-page supplement entitled Additional Revised Prices lists “a swivel top, with piece framed between the rails for ditto” under a heading for card tables. This little booklet was probably issued shortly before or soon after another supplement entitled Additional Prices Agreed Upon by the New-York Society of Journeymen Cabinet Makers and dated July 1815. Swivel tops formed part of the furniture headings in the 1817 New York price book, affirming widespread acceptance of the technique by that date. Firmly datable American examples commence about 1815. Duncan Phyfe made a pair of swivel-top card tables for James Lefferts Brinckerhoff of New York in May 1816. Among the earliest datable New England examples is the “pr of Grecian card-tables” that Thomas Seymour made for Peter Chardon Brooks, also in 1816. Recent dating of the Edward Lloyd family swivel-top card table to circa 1812 is conjectural. Assuming its attribution to Baltimore furniture maker Edward Priestley is correct, it is not specified in any of several documented payments, one of which was made in 1812. Another unspecified payment in 1817 for $43.50 seems to be a more reasonable time frame for this table. In October of that year, Stephen Girard bought his stylish pair of dolphin-carved swivel-top card tables from Henry Connelly of Philadelphia.[17]

Design flexibilities inherent in swivel-top technology accommodated other card table features that may also be dated independently to circa 1815. An early swivel-top card table bears the label of New York cabinetmaker Joseph Brauwers, self-described as another “ebenist, from Paris” (fig. 19). Brauwers was listed at the address printed on the label in 1814, but how long he remained there or used that label is unknown. His card table combines a swivel top and a frame with canted corners on a base of four small columns gathered in the center above a platform supported on “swept” legs, which are often referred to today as saber legs. Canted corners were described in the undated Additional Revised Prices supplement and were among the few entries noted, but not described, in the 1815 Additional Prices amendment to the 1810 edition, in which canted corners were not mentioned. The wording in the undated supplement was unchanged in the 1817 price book: “Canted corners, the rail glued up in thicknesses or dovetailed, ditto veneered and mitred on the corners, extra from square solid table.” The frame of the Brauwers table is made of solid mahogany boards, dovetailed at the corners (fig. 20). Its construction is unusual in the use of mahogany rather than white pine as the secondary wood. It also differs in having a thin, one-quarter-inch thick casing of mahogany laminated over the inner frame and underneath the outer figured mahogany veneer. Canted card tables “glued up in thicknesses” described laminated frames, but the laminations were horizontal rather than vertical as they are on this table. A typical example has three laminated layers of white pine that stagger at the cants like brickwork (figs. 21, 22). An informal survey of New York canted frames suggests that laminated construction was less common than dovetailed boards.[18]

The laminated table frame illustrated in figure 21 rests on a lyre base, in turn supported on a platform into which four swept legs are dovetailed. The front façade of the paired lyres forming the base is carved and ornamented with iron strings (which are usually made of brass or wood). The rear lyre is blank. Although New York card tables with lyres and lyre-back chairs are popularly dated as early as 1810, evidence suggests that these particular motifs, as with swivel tops, came into use about 1815. Unequivocal evidence for such designs begins in late 1815, when Duncan Phyfe sketched and executed lyre-back chairs, which he sold to Charles N. Bancker of Philadelphia in January of the following year (fig. 23). Later in 1816, Phyfe sold two more sets of lyre-back side chairs (one caned and one upholstered, the same combination as noted on the Bancker drawing) and a lyre-end sofa to James Lefferts Brinckerhoff of New York.[19]

Lyres as furniture motifs first entered American price lists in the 1817 New York Book of Prices. As illustrated in a plate in the back of that and other publications and as observed in several tables, lyres were made in halves and tenoned into the table bed above and the platform below (fig. 24). In some elegantly constructed tables, the lyres “crossed at right angles,” producing a sculptural pillar (fig. 25). The four legs had dovetailed ends that slid into the canted corners of the platform, termed the “octagon block.” These blocks were either thick boards laminated horizontally or built up of two thick boards oriented on end that crossed with a lap joint. Triangular blocks filled out the sides (fig. 26). The small printed supplement to the 1810 New York price list, undated but probably about 1815, described the laminated technique as “glueing up the block long and cross way.” The supplement also specified that the grain be set at oblique angles—“lapp’d and the corners filled in”—to minimize warping and splitting. Iron straps screwed into the undersides of the legs and the block held the legs in place, relieving some of the downward stress on the joints and preventing the dovetail mortises from splitting apart.[20]

As with lyre motifs, canted corners were not new in the early nineteenth century. Tables with octagonal tops had been made a hundred years earlier, and case pieces with narrow, canted corners became popular by the 1730s. Tables with canted corners were included in the 1796 price lists for New York and Philadelphia furniture, each of which resembled the other and borrowed heavily from the London price list of 1788 and subsequent editions of the 1790s. The 1796 New York price list included entries for a “Canted Corner Work Table” and a “card table with canted corners to be the same price as circular.” “Rounding or canting the corners of the flaps” was also mentioned as the least expensive of several decorative options for Pembroke tables. As price tables in the back of these publications indicate, however, these canted corners were fundamentally different from those of 1815 and later. The earlier canted corners were narrow, ranging from “one inch and a quarter [on the flat]” to three inches. In contrast, canted corners on tables made after 1815 are usually at least six inches wide, a dimension that created a markedly different table shape. The listing for narrow canted corners continued in the 1802 New York edition, but thereafter lapsed in that city and elsewhere in the United States. No mention of canted corners occurs in either the 1810 New York price book or the 1811 Philadelphia one. However, with the advent of swivel tops and the design freedom they allowed, New York furniture makers needed to add the new canted shape in 1815, when references and documented instances of use occur with increasing frequency.[21]

The card tables that Phyfe made for Brinckerhoff attest to the dynamic and evolving nature of New York furniture design after 1815. In addition to swivel tops and canted corners, these tables have four, widely spaced, turned and fluted colonnettes set onto a broad platform with concave sides and four hocked animal feet with gilded acanthus carving (fig. 27). The platform is horizontally laminated in the same fashion as the octagonal blocks of card tables with four clustered columns. Whereas most tables of this form have clustered columns socketed up into a single, wide crosspiece supporting the table bed, the more widely separated column pairs of the Brinckerhoff tables fit into separate crossbars dovetailed into the bed (fig. 28). However, the most important aspect of this design was the range of creative opportunity that lay within the platform concept. Lannuier realized these possibilities more fully than anyone else, producing tables similar to Brinckerhoff’s as well as those with a carved and gilded caryatid (fig. 29), dolphins, or broad lyres in place of the two forward columns. Variations by other makers included tables with carved eagles or inverted cornucopia forming the front legs, or scrolled front legs in combination with a rear lyre, all on similar platform bases. Several of these features were illustrated in plate 5 of the 1817 New York price list (fig. 24). Michael Allison labeled yet another canted-corner card table of this general plan that had four ornately carved cyma-curved supports and eagle-headed feet (fig. 30). The label on this table bears the printed date of January 1817.[22]

A group of swivel-top card tables that Lannuier labeled before his death in 1819 suggests that he played a crucial role in developing that form. According to furniture historian Peter Kenny, Lannuier may have taken the idea of swivel tops from prototypes made in post-Revolutionary France. Several details remain unresolved, however. If Lannuier learned about swivel tops before leaving France for New York in 1803, why did the technique remain dormant for so long? When, in fact, can swivel tops be documented in French furniture? If swivel tops did originate in France, what was the role of other French-trained furniture makers working in New York, such as Joseph Brauwers? Latrobe’s role also deserves more scrutiny.[23]

Lannuier’s familiarity with swivel tops and his proclivity to experiment with various designs led to the production of tables with incurved or concave corners. Examples with this feature from New York and elsewhere in the United States are very rare except in his work. The first specifically dated use of concave corners occurs in two nearly identical pairs of gilded figural card tables made for William Bayard of New York City in 1817 (fig. 29). Another pair of tables with concave corners was among work Lannuier shipped to Cuba shortly before he died in 1819. A card-table-size New York serving table (Boscobel Restoration) and an inlaid card table are the only other examples with similar corner treatment. Although these tables are anonymous, they establish that cabinetmakers other than Lannuier produced this concave-corner form. As with canted corners, care must be taken to distinguish these corner treatments from narrower hollows found on some tables and case pieces. Similarly, an engraved plate that appeared in the 1811 London Book of Prices illustrates a tabletop with “hollow ends,” not incurved corners. Moreover, that shape seems not to have been used much if at all in the United States.[24]

Lannuier and other New York furniture makers combined canted-corner tops with other card table design features to extend their range of offerings. Lannuier’s design of a pair of monochromatic mahogany swivel-top card tables is remarkably subdued in comparison to his gilded figural furniture from the same period, namely 1815 to 1819 (fig. 31). The turned and reeded front legs join the middle of the cant and are marked on the outside by a raised panel or plinth. A similar swivel-top table bears the label of John Budd (active 1817–1840) with the engraved date of May 1817 (fig. 32). This table differs in having twist- or rope-turned legs, a decorative treatment that seldom appeared before this date except in card tables from Lannuier’s shop. A more imaginative interpretation occurs in a pair of canted-corner tables with bandy legs, carved waterleaf ornament, and animal feet (fig. 33). As with the turned-leg tables, these front legs intersect the center of the canted corner, marked by a carved panel. Canted-corner card tables with a variety of bases continued to be made through the 1820s.[25]

Some bases for card tables were the same as those made for contemporary Pembroke tables and sofa tables. One of the more elegant designs features an octagon block raised on four swept legs (figs. 34, 35). On the table illustrated in figure 34 the block supports four turned and carved colonnettes set close to one another and a carved finial in the center. In contrast, the classic pillar-and-claw Pembroke base with a single urn-shaped and waterleaf-carved pillar above four swept legs was seldom, if ever, used on swivel-top card tables (fig. 36). The urn-shaped base was used consistently on mechanical, three-legged card tables, although questions of stability seem to have truncated its longevity. By the time pillar-and-claw bases were practical for card tables, the fashion for urn shapes seems to have passed in favor of more complex carved supports. Although there were many intersections in card table and Pembroke table design, some bases were not suitable for both forms. Large pillars had been used on Pembroke tables since the 1790s, but they were not a viable option for folding-top card tables, which had changing centers of gravity. Similarly, some front-facing platform-base designs for swivel-top card tables were not appropriate for the in-the-round design of Pembrokes. The boldly carved eagles with outswept wings supporting a canted-corner frame on a pair of card tables relate to pier tables instead (fig. 37). In general, however, card and Pembroke table designs moved in tandem, and the two table forms were sometimes made en suite.[26]

A pillar-and-claw card table with the August 1820 printed label of Duncan Phyfe demonstrates how fully card table designs had blended with Pembroke designs (fig. 38). Four leaf-carved legs rise to a boldly turned pillar beneath a D-shaped top. A highly decorated pillar on a firm, four-claw base supported Pembroke table frames as readily as card tables. Carved and uncarved versions dominated table designs of the 1820s. Two more Phyfe card tables with the same label use paired pillars spaced at each end of a trestle base. Whereas the single turned pillar updated an existing base design, the two-column trestle-base design has no obvious prototypes (figs. 39, 40). On one table the hexagonally faceted pillars taper downward. On the other, the turned pillars are architecturally rendered columns with brass-mounted capitals and bases. Curved and carved legs form each leg unit, which are connected by a stretcher.[27]

Card tables of the 1820s and later continued to express the creativity of their makers while marking broader changes in fashion and taste. Yet increasing popularity of center tables and accompanying shifts in furnishing arrangements diminished the importance of the card table—used for all sorts of functions but designed to stand against the wall—relative to other furniture forms. In classic understatement, the authors of An Encyclopedia of Domestic Economy (1845) foretold the bland future of these tables. After extolling the “modern and improved” swivel-top design, they observed, “these card-tables are, therefore, capable of every kind of embellishment as well as any occasional tables, and there is nothing in their appearance to distinguish them particularly from other tables.” Gradually, card tables blended into the seemingly endless array of tables made for mid-nineteenth-century living.[28]

David Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanack, New-York Register, and City Directory (New York, 1805), p. 111. Margo C. Flannery reports that about one thousand furniture makers were listed in New York City directories between 1795 and 1825 in “Richard Allison and the New York City Federal Style,” Antiques 103, no. 5 (May 1973): 1001. Marilynn A. Johnson, “John Hewitt, Cabinetmaker,” Winterthur Portfolio 4 (1968), pp. 185–205. Peter M. Kenny, “From New Bedford to New York to Rio and Back: The Life and Times of Elisha Blossom, Jr., Artisan of the New Republic,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 238–69.

A demilune card table with the label of New Yorker George Shipley (active 1791–1795) is identified as a Providence, Rhode Island, product; the Charles Courtright label on another demilune card table, probably of New York manufacture, is called spurious in Benjamin A. Hewitt, Patricia E. Kane, and Gerald W. R. Ward, The Work of Many Hands: Card Tables in Federal America, 1790–1820 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1982), nos. 32, 39. Patricia E. Kane, “Design Books and Price Books for American Federal-Period Card Tables,” in ibid., p. 46.

Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period (New York: Viking Press, 1966), no. 297. The mate to the commemorative table shown in figure 1 was sold in Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 21–22, 2000, lot 730. “Ovalo” corners, commonly spelled “ovolo” today, appear throughout The Journeymen Cabinet & Chair Makers’ New-York Book of Prices (New York: T. & J. Swods, No. 99 Pearl-Street, 1796) and The New-York Book of Prices for Cabinet & Chair Work, agreed upon by the Employers (New York: Southwick and Crooker, September 1802). The term was dropped from The New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (New York: Southwick and Pelsue, 1810) and later price books. Between 1800 and 1806 New York cabinetmaker John Hewitt shipped “inlaid sash cornered” sideboards to Savannah, which seems to be this shape. Johnson, “John Hewitt,” pp. 186–88. For more on the woods used in card tables made in New York, see Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, Many Hands, chart 12, p. 194. For another card table similar to the example illustrated in figure 3, see ibid., pp. 89–91, no. 37. According to David L. Barquist, the vertically laminated ovolo corners of the card table shown in figure 3 are made of tulip poplar (American Tables and Looking Glasses in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University [New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992], no. 108). Philip D. Zimmerman, “The Architectural Furniture of Duncan Phyfe, 1830–1845,” in The Richard and Beverly Kelly Collection (Portsmouth, N.H.: Northeast Auctions, April 3, 2005), p. 15, fig. 7. Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, Many Hands, chart 12, p. 194.

For a New York six-leg card table with two swinging legs and a Rhode Island six-legged table with one swing leg, see J. Michael Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986), nos. 64, 68. New-York Book of Prices 1802, p. 20. New-York Book of Prices 1796, p. 35. New-York Revised Prices 1810, p. 24; and The New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (New York: J. Seymour, 1817), p. 34. The Journeymen Cabinet and Chair-Makers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices (Philadelphia: Printed for the Society, 1811), p. 33.

New-York Book of Prices 1802, p. 21.

For a table with matched veneers, see Berry B. Tracy, Federal Furniture and Decorative Arts at Boscobel (New York: Boscobel Restoration and Harry N. Abrams, 1981), no. 28. New-York Revised Prices 1810, p. 26.

For card tables with unvarnished veneer on the underside of the stationary leaf, see Montgomery, American Furniture, nos. 314, 319, 320; and Tracy, Federal Furniture, no. 27. New-York Book of Prices 1817, p. 3. Tracy, Federal Furniture, no. 52; white pine boards are used elsewhere in the bed steps. Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Dictionary, 2 vols. (1803; reprint, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 1: 129–30. For a card table with a leather playing surface and a fixed leaf with underside veneer, see Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 318.

New-York Book of Prices 1802 states, “All straight drawers the top edge slip’d with mahogany” (p. 3), and “the top edge of the drawer fronts slipt with mahogany” (p. 9). New-York Book of Prices 1796, p. 9, includes an entry for “Slipping drawer sides, and rounding the slips,” which may be more representative of London practices. New-York Book of Prices 1802, p. 21.

For a New York card table with a full-width, single-board top, see The Taft Museum: The History of the Collections and the Baum-Taft House, edited by Edward J. Sullivan (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1995), p. 103. Glue joints between the boards are sometimes difficult to detect.

Core woods of some top leaves are visible through mortises cut through the slipped back edges for alignment tenons.

New-York Book of Prices 1796, p. 36. Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (1793; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1972), p. 161. Sheraton recommended 3 1/2" widths in his Cabinet Dictionary, 1: 129.

The term “rear leaf-edge tenon” is used in Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, Many Hands, chart 12, p. 194. Only 2 of the 27 New York tables in Hewitt’s study had three rear leaf-edge tenons, but this author knows of many others. Some card tables from other regions do not have any alignment tenons, and only those made in New York are known to have four. New-York Book of Prices 1817, p. 3. The two nearly identical tables (acc. nos. 57.722 and 57.723) are installed as a pair in the Phyfe Room. One (57.723) is illustrated in Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 315. See card table 1932.8 in Taft Museum, p. 103.

For comparative uses in card tables, see Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, Many Hands, chart 11, p. 194. Several visual identifications recorded as white pine may actually be other, visually similar woods, such as Atlantic white cedar, but reliable evidence confirms widespread use of white pine in furniture making. The card table illustrated in figure 1 has a walnut outer rear rail, which is an exception. A similar exception occurs in the walnut hinged supports, or “flies,” of a New York Pembroke table at Winterthur labeled by George Woodruff. See Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 331.

This early generation of the form was produced only in New York and, to a lesser degree, in Philadelphia. For a Philadelphia example, see Philip D. Zimmerman et al., Sewell C. Biggs Museum of American Art: A Catalogue, 2 vols. (Dover, Del.: Biggs Museum, 2002), 1: 51, no. 34. New-York Revised Prices 1810, p. 25. Some tables are so closely balanced, especially when closed, that the direction of pivoting rear-leg casters determines whether the table will stand unsupported.

As quoted in Jack L. Lindsey, “An Early Latrobe Furniture Commission,” Antiques 139, no. 1 (January 1991): 212. Lindsey dates the card table circa 1808. As quoted in Beatrice B. Garvan, Federal Philadelphia, 1785–1825: The Athens of the Western World (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), p. 91. The undated Latrobe designs for the Madison seating, which are believed to be circa 1809 based on correspondence, show chairs that have elaborate stretchers on deeply curved front and rear legs, in contrast to the bold, stretcherless designs of the Waln chairs. Arguments can be advanced to support either set as the earlier. The author thanks Christopher Storb for providing further information. George Wright is listed in Deborah Ducoff-Barone, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers, 1800–1815,” Antiques 145, no. 5 (May 1991): 995.

Ralph Edwards, The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture: From the Middle Ages to the Late Georgian Period (London: Country Life, 1964), pp. 526–27, fig. 31. As quoted in Barquist, American Tables, p. 220. Prices of Cabinet Work, with Tables and designs . . . revised and corrected by a committee of Master Cabinet Makers. These two price books are in the British Library. The author thanks Adam Bowett for bringing them to his attention and checking their contents. Peter M. Kenny, Frances F. Bretter, and Ulrich Leben, Honoré Lannuier: Cabinetmaker from Paris (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), nos. 57–58, 61, pp. 150–52. Peter Kenny dates the label on the basis of style between 1810 and 1812. Written and other evidence does not allow precise dating for the Lannuier card tables, the labels, or documented or attributed Lannuier furniture related to these card tables. The original owner of the pair of card tables also owned a bedstead, which bears the third Lannuier label, stylistically dated from after 1812 to 1819.

Additional Revised Prices, p. 3, Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Additional Prices Agreed Upon by the New-York Society of Journeymen Cabinet Makers (July 1815), Winterthur Library. Jeanne ffibert Sloane, “A Duncan Phyfe Bill and the Furniture It Documents,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1109, fig. 6. Robert D. Mussey Jr., The Furniture Masterworks of John and Thomas Seymour (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Essex Museum, 2003), no. 113. The date range of 1808–1815 assigned to card table no. 112 is too early. Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates dated it circa 1818 in American Furniture: 1620 to the Present (New York: Richard Marek Publishers, 1981), p. 256; and Richard H. Randall Jr. dated it 1815–1825 in American Furniture in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1965), no. 105. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Survival of the Fittest: The Lloyd Family’s Furniture Legacy,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), p. 35; Alexandra A. Alevizatos, “‘Procured of the Best and Most Fashionable Materials’: The Furniture and Furnishings of the Lloyd Family, 1750–1850” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1999), p. 221. The author dates the table 1810–1815 and 1810–1820 in earlier studies: Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “A New Suspect: Baltimore Cabinetmaker Edward Priestley,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 113–15; and Alevizatos, “‘Procured of the Best and Most Fashionable Materials,’” pp. 335–37. Robert D. Schwarz, The Stephen Girard Collection (Philadelphia: Girard College, 1980), no. 23.

Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 318. A similar card table also labeled by Brauwers is no. 16 in Classical America, 1815–1845 (Newark, N.J.: Newark Museum Association, 1963). Additional Revised Prices, p. 3; Additional Prices 1815, p. 5; and New-York Book of Prices 1817, p. 34. Another construction feature that distinguishes the Brauwers table from other New York work is visible on the underside of the fixed top leaf: it combines mahogany veneer on secondary wood longitudinal boards with unveneered solid mahogany clamps. Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 319. The laminations on this table frame are unusual in having wood grain oriented in parallel rather than at oblique angles.

A much earlier and isolated exception can be found in an undated Philadelphia-made armchair with a lyre-shaped back splat. Perhaps one of twelve belonging to George Washington, the chair resembles a set made between 1792 and 1797 by Adam Haines of Philadelphia. See Deborah D. Waters, Delaware Collections in the Museum of the Historical Society of Delaware (Wilmington, Del.: Historical Society of Delaware, 1984), no. 11; Kathleen Catalano and Richard C. Nylander, “New Attributions to Adam Haines, Philadelphia Furniture Maker,” Antiques 117, no. 5 (May 1980): 1112, 1114. An apparent second member of the lyre-back set, not examined by the author, differs in its finials and other small decorative details, which may represent later changes to either of the two surviving chairs. See Sotheby Parke-Bernet, American Heritage Auction of Americana, New York, January 27–30, 1982, lot 1094. Montgomery, American Furniture, pp. 124, 126–28, nos. 72–73. The Phyfe drawing is on a separate piece of paper from the Bancker bill and is not dated but is presumed to be related to the bill. Sloane, “A Duncan Phyfe Bill,” p. 1109, pl. II, fig. 7.

Mention of lyres is absent from the 1810 New-York Revised Prices and the 1811 Pennsylvania Book of Prices. For examples with crossed lyres, see Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 320; Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, nos. 62–63; and Tracy, Federal Furniture, no. 27. Additional Revised Prices, p. 4. Peter Kenny identifies this little booklet, a copy of which is in the Library of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, as pre-1815, in Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, p. 82 n. 90. See also p. 179.

New-York Book of Prices 1796, pp. 33, 36, 62, table 17. An obscure circumstance occurred in 1806 when furniture maker James Linacre of Albany charged Peter E. Elmendorf “To repairing a tabel and cuting the corners.” A rectangular, Marlborough-leg Pembroke table with large cants at the corners of the drop leaves survives with other Elmendorf furniture and may be this table. See Anne Ricard Cassidy, “Furniture in Upstate New York, 1760–1840: The Glen-Sanders Collection” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1981), p. 38.

Sloane, “A Duncan Phyfe Bill,” p. 1109, fig. 6. Veneer covers the tops and sides, but splitting patterns reveal the inner structure of a near mate to the Brinckerhoff table. Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, nos. 64–87. Barquist, American Tables, no. 120; American Furniture with Related Decorative Arts, 1660–1830: The Milwaukee Art Museum and the Layton Art Collection, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991), no. 97; and Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, figs. 52, 93. Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Inc., photo files.

Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, p. 178.

Collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Albany Institute of History and Art. Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, nos. 70–73. Peter M. Kenny, “Opulence Abroad: Charles-Honoré Lannuier’s Gilded Furniture in Trinidad de Cuba,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 239–64, figs. 6, 11. Tracy, Federal Furniture, no. 39; and Israel Sack, Inc., Opportunities in American Antiques, brochure 39 (June 1, 1984), p. 66, no. p5554. For the London Book of Prices engraving, see Montgomery, American Furniture, p. 359.

Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, nos. 55–56. The circa 1810 date assigned to no. 306 in Montgomery, American Furniture, is too early. In Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, Many Hands, no. 41, the authors call the swivel-top tables “the earliest known documented example of this simple construction” yet provide no dating beyond Lannuier’s birth and death. Elisabeth Donaghy Garrett, The Arts of Independence: The DAR Museum Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Society, Daughters of the American Revolution, 1985), p. 117, nos. 115, 116. Barquist, American Tables, no. 117.

For Pembroke tables with a single urn-shaped and waterleaf-carved pillar above four swept legs, see Montgomery, American Furniture, no. 332; Tracy, Federal Furniture, no. 35; and Nancy McClelland, Duncan Phyfe and the English Regency, 1795–1830 (New York: William R. Scott, 1939), pls. 133, 137. Barquist, American Tables, no. 119.

Another Phyfe-labeled card table of this form is in Kenny, Bretter, and Leben, Honoré Lannuier, fig. 104. Israel Sack, Inc., Opportunities in American Antiques, brochure 43 (July 1, 1988), no. p6037; and Christie’s, Important American Furniture, New York, October 8, 1997, lot 86.

T. Webster and Mrs. Parkes, An Encyclopedia of Domestic Economy (1845; New York: Harper & Brothers, 1848), p. 261.