George Cruikshank, “Eva Dressing Uncle Tom,” wood engraving, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, London, 1852. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.) Staffordshire manufacturers often replicated the relative scale and pose of Eva and Tom in their figural reproductions based on characters in Stowe’s novel.

Hammatt Billings, “Eliza on the Ice Floes,” wood engraving, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Illustrated Edition, Boston, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.) Billings’s rendering of Eliza as a Caucasian helped to elicit sympathy for the character’s plight. In Staffordshire, Eliza is also shown as white, whereas French ceramic manufactories tend to show her skin color more accurately.

“Tom et Evangeline” and “La Fuite d’Elise,” Limoges, ca. 1852–1853. Biscuit- and glazed hard-paste porcelain with polychrome enamels and gilding. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center; photo, author.)

Charles Bour, “Tom et Evangeline,” lithograph, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, La Case de l’Oncle Tom, Paris, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 68.288.Pr.F3.)

Bettannier, “La Fuite d’Elise,” lithograph, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, La Case de l’Oncle Tom, Paris, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 68.288.Pr.F3.)

Anonymous, “Eva and Uncle Tom,” from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Pictures and Stories fromUncle Tom’s Cabin, Boston, 1853. (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.) This was a juvenile edition of Stowe’s novel. Note the shape of Tom’s eyes and his unusually expressive face. The style of illustration is orientalist and idealized, rather than relying on caricature and overexaggerated features. This approach to depicting negroid features typifies the French decorative style, whether on vases or tablewares.

“Tom et Evangeline” and “La Fuite d’Elise,” Limoges, ca. 1850–1860. Biscuit- and glazed hard-paste porcelain with polychrome enamels and gilding. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase in memory of Genevieve Lydian Dutton Gundry by her son Jas A. Gundry, acc. nos. b2000.6.1, 6.2.) Although these figures share similar pastel palettes, the gilding on each of the pairs diVers dramatically.

“Tom et Evangeline” and “La Fuite d’Elise,” Limoges, ca. 1852–1853. Biscuit- and glazed hard-paste porcelain with polychrome enamels and gilding. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These and several other pairs of vases are decorated with fanciful enameling, but no two pairs have surfaced with identically painted features.

“Tom et Evangeline” and “La Fuite d’Elise,” Limoges, ca. 1852–1853. Biscuit- and glazed hard-paste porcelain and gilding. H. 19". (The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey, Purchase 1968, Mrs. Parker O. Griffith Fund, 68.106 a,b.)

Nathaniel Orr and Company, “Saleroom, Main Floor, Haughwout Building, New York,” wood engraving, from Cosmopolitan Art Journal 3 (June 1859). (Courtesy, the author.) This view of the ground-floor premises of the retailing emporium of Haughwout and Dailey at 540 Broadway shows a tantalizing survey of stylish porcelain and glass available for purchase in the 1850s. Haughwout’s hired women—mostly from Staffordshire but also from porcelain towns in eastern France and western Germany—to work as decorators in the custom workshop upstairs from the main selling floor. Many of the Uncle Tom’s Cabin-motif French vases might have acquired their unusual coloration and gilding styles from the women decorators working at this establishment.

Figurines based on characters from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Staffordshire potteries, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1852–1860. Bone china. H. of tallest approx. 8". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Rex Stark.)

Left: “Eva, Uncle Tom, Boat,” Dudson factory, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1852–1855. Whiteware. Right: “Eva and Uncle Tom on the Boat,” unknown factory, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1852–1855. Whiteware. H. of tallest 7". (Courtesy, Christie’s, London.) “Eva, Uncle Tom, Boat” is the only figural group whose attribution to a specific Staffordshire factory producing earthenware figures based on Uncle Tom’s Cabin is confirmed.

Figural group, “Eva, Uncle Tom, Boat,” Dudson factory, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1852–1855. Whiteware. H. 7". (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 81.18.)

George Cruikshank, “Prayer Meeting inUncle Tom’s Cabin,” from Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, London, 1852.

Plate, “PRAYER MEETING,” unknown factory, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1852–1855. Molded earthenware transfer-printed in warm black enamel. D. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 81.34.) The image of the “Prayer Meeting” is taken directly from the Cruikshank illustration shown in fig. 14. The mantel decor is typical of aspirational middle-class taste, not a true slave home interior

Plate, “UNCLE TOM'S CABIN / ELIZA CROSSING THE OHIO ON THE FLOATING ICE,” unknown factory, Stoke-on-Trent, ca. 1855. Earthenware with molded rim, transfer-printed in warm black enamel. D. approx. 5". (Courtesy, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 81.28.) This plate shows a revised illustration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Note that Eliza and Baby Harry are running toward the right side of the plate, whereas the standard orientation shows them running toward the left. The plate imagery is highly degraded.

Two-handled cups, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1854-1858. Whiteware. H. of tallest 6". Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Compared to plates, these unusual hollow-bodied wares were relatively expensive to produce. On the smaller cup is depicted Topsy, who, while supposedly working at Olivia's house, is being mischievous. "MASTER GEORGE TEACHING TOM" appeard on the trophy cup. Both images are from Cruikshank's illustrations for the first English edition of Stowe's novel.

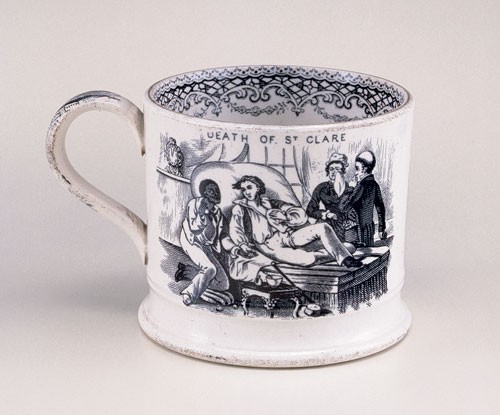

Mug, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1852–1855. Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Some of the Uncle Tom prints used by ceramic factories provide wonderfully detailed views of mid-nineteenth-century Victorian interiors. George Cruikshank’s “DEATH OF ST. CLARE” has been transposed from the English edition of Stowe’s novel to this child’s cup. The louche plantation owner is surrounded by fine furniture and other talismans of wealth.

Plate, attributed to J. Vieillard et Cie., Bordeaux, ca. 1855. Whiteware. D. 8". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate illustrates the scene “Uncle Tom Refuses to Hit Legree” (L’Oncle Tom Refuse de Battre Legree). The international success of Stowe’s novel was fueled by worker literacy movements on the Continent. Because Stowe capitalized on the popularity of the sentimental novel, women bought her book; men bought it for the action within; and religious groups and parents approved of its high moral tone. The novel was printed in more languages and in more countries at mid-century than any book other than the Bible.

Plate, Schramburg, Germany, ca. 1855. Whiteware. D. 8". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This two-color transfer-printed plate illustrates “Uncle Tom Leaving with Legree” (Onkel Tom mit Le Gree Gereitt).

Plate, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1855. Earthenware. D. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This molded polychrome-painted and transfer-printed plate depicts “THE DEATH OF UNCLE TOM,” based on Cruikshank’s illustration.

Plate, probably northern England or Scotland, ca. 1855. Whiteware. D. 7". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This earthenware polychrome transfer-printed and painted plate illustrates the “DEATH OF UNCLE TOM.” The plate was meant to appeal to a person of higher social standing than the example shown in fig. 21. Here, the teal blue sponged border frames the puce image of Tom lying on his deathbed.

Plate, J. Vieillard et Cie., Bordeaux, ca. 1855. Whiteware. D. 8". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate has an even more delicate rendering of the tragic death of Uncle Tom. The elaborate printed blue border is quite wide, diminishing the visual impact of the central image. Uncle Tom’s death, illustrated in a warm, charcoal black with delicate detail, is based on an entirely different print source from the previous images, Girard’s steel-cut engravings for the first French edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853).

“Eva and Uncle Tom,” parian sculpture from the Royal Worcester production catalogue, ca. 1853–1855. Salt print photograph. 3 1/8" x 2". (Courtesy, The Worcester Porcelain Museum.) Wendy Cook, curator at the museum, has seen only one example of this figural group, and it was painted with polychrome enamels.

Southworth and Hawes, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Quarter-plate daguerreotype, ca. 1850. 4 1/4" x 3 1/4". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of I.N.Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, and Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937, acc. no. 37.14.40.)

Mug, Staffordshire, ca. 1855–1860. Earthenware. H. approx. 8". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Transfer-printed in warm medium blue, the legend reads “Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe / AUTHOR OD UNCLE TOM'S CABIN.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) was not just a novel; it was a cultural phenomenon. Its influence spread across America and Europe through political discourse, theatrical interpretations, and a host of visual and material representations. Now, more than 150 years after its initial publication, it is inseparable from the fabric of American culture and mythology. Of the multitude of objects produced in the wake of the novel’s publication, some of the most interesting are the ceramic and porcelain figures, vases, and decorative plates depicting scenes from the novel. These objects, produced primarily for use as decoration in Victorian parlors, speak to the varied ways Uncle Tom’s Cabin functioned in the domestic lives of their owners and teach us much about the objectification of the reader’s experience of the novel in mid-nineteenth-century America.

Although manufacturers made thousands of Uncle Tom items, more than 75 percent of the objects portray two specific scenes in the book. Because these scenes crystallize the moral and familial dramas at the novel’s center, it is no surprise that they were reproduced so extensively. The first, representing the highest “moral moment,” is the scene in which Evangeline, or Eva, “dresses” Uncle Tom in garlands of flowers (fig. 1): “every one of his buttonholes stuck full of cape jessamines . . . Eva, gayly laughing . . . hanging a wreath of roses around his neck.”[1] In this brief interlude of spontaneous love and affection, Tom’s childish simplicity makes him Eva’s emotional equal. The old slave, holding a Bible in his left hand, is now a literate and God-fearing man, embraced by the loving daughter of his owner. The garland of flowers around Tom’s neck strikes another religious note, reminding the viewer of the Lamb of God, similarly garlanded, who also sacrificed his life for others.

Conversely, the lowest moral and greatest melodramatic moment occurs as Eliza crosses the frozen Ohio River with Baby Harry in her arms (fig. 2). “Nerved with strength such as God gives only to the desperate,”[2] she runs away from slave trappers, away from a life of misery in Kentucky toward life as a free woman in Canada. This second scene reminded contemporary viewers that slave owners separated family members from one another for commercial reasons and sent bounty hunters across state lines to find escaped slaves and return them, as chattel, to their owners.

These two moments are beautifully shown in a pair of elegant figural vases, full of movement and emotion, produced at Limoges for export to America, about 1852–1853 (fig. 3).[3] The dramatic poses and coloration of the vases probably derive from a pair of prints published in the first French edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, La Case de l’Oncle Tom.[4] The scene of Eva and Tom (fig. 4) is by Charles Bour (act. 1844–1880), who exhibited paintings in the Paris Salon and made lithographs of competition entries. The second image, of Eliza’s flight (fig. 5), is signed by Bettannier, about whom little is known. Both prints share an interest in bright polychromy and imaginative foliage that are present as well on the vases.

The fanciful and heavy foliage creeping around the vases and the awkward position of Uncle Tom’s legs may derive from an additional source, the sixth illustration of the 1853 children’s edition of Stowe’s novel, called Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (fig. 6).[5] This image emphasizes Tom’s exotic, nearly Asian features, and his awkwardness before social superiors (that is, Caucasian plantation owners). His deference is underscored by his holding his hat rather than a Bible.

The figural work on these vases is of biscuit porcelain, which contrasts with the glassy glaze and bright, mercury-flashed gilding on the very high Victorian flat-backed frill vases behind the figures. The contrast of textures echoes the contrast of movement, particularly in the Eliza and Harry vase, which looks as if the figures are trying to escape from the front of the vase, running away as we do in nightmares, our feet stuck in concrete. Visual tension underlines dramatic motion. In addition, the application of overglaze polychrome enamels to the surface changes the tenor of the sculptures. In unglazed biscuit and gold, they are like refined marble statues, projecting virtue and moral aspirations. The polychrome enamels make the figures look more human, and they project the hopes and fears of the characters they depict. In underlining the melodrama of the various scenes, the coloration enabled merchants who wanted to take advantage of the fad for figures based on Stowe’s novel to sell commercial goods in quantity.

Research to date has identified two distinct models: a smaller model, at 11 3/4 inches (fig. 8), and a larger example, at 19 inches high (fig. 9). Both are found decorated in different ways, varying from undecorated biscuit and elaborate gold patterning on the vase forms to overglaze polychrome enameling with extensive gilding. Four pairs of large vases and a single example missing its mate have been identified: one pair in biscuit with gilt highlights in the collection of the Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey (see fig. 9); a single vase of Uncle Tom, also with gilt decoration decorated with gold only, now in a private collection; a pair decorated in biscuit and matte blue with gold, auctioned at Christie’s East, New York, October 27, 1998; and two pairs with extensive polychrome decoration and gilding in the collections of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut, and the Museum of the City of New York, respectively.

Four pairs of the small vases have also been identified: a pair in biscuit with gold highlights from the inventory of Gary and Diana Stradling, New York dealers who specialize in American ceramics; and three pairs decorated with polychrome enamels and gilding, one at Bayou Bend, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas (fig. 7), one in a private New England collection, and one at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center (see fig. 3).

Although the two sizes of vases are modeled differently from each other, all of the large vases are identically modeled, as are all of the small vases. This is typical of Limoges wares and speaks to the desire of manufacturers to reach diverse segments of the purchasing public. No two pairs of vases have been found with identical decoration, a fact explained by the desire of American merchandisers to present consumers with a wide array of choices. As has been noted by historians of the period 1850–1860, retailers of luxury goods had workrooms above their showrooms where special orders were executed, including those for porcelains.[6] As proof, the Cosmopolitan Art Journal illustrated the premises of the New York retailers Haughwout and Dailey of 540 Broadway at Broome Street (fig. 10). In their upstairs workrooms, more than one hundred “mostly English” china painters and several female gilders, imported from Staffordshire and elsewhere, labored to decorate items chosen by the customers downstairs.[7]

Overglaze enameling work was done after the modeling factory shipped the vases in the white, as undecorated ceramics were taxed and dutied at a much lower rate than those with elaborate details.[8] Museum curators and ceramics dealers have often misattributed these figures to Bohemia. It is now clear, however, that the vases were produced in Limoges and sent undecorated to New York, where they were decorated by Bohemian, French, and English painters and then sold. As the painters had been taught enameling and gilding in distinctive European markets, the figures reflect the background of their decorators. For instance, the vases with matte blue and gilding were decorated by an enameler trained in Limoges, where that style of decor was considered chic. The vases with enamels of intense hue and with fanciful water and plant colorations would have been painted by a decorator from Staffordshire accustomed to enameling Staffordshire figurines. The vases with very precise costume details and distinct orientalist landscapes, with attention paid to minutiae and having large areas of picked out and flashy gilding, were enameled by Bohemian workers.

The decorating on all the Uncle Tom vases may have been done at the same establishment because certain decorative elements appear more than once on the various pairs. For instance, two pairs were painted with trompe l’oeil orientalist landscapes on the tapered bases of the vases; these scenes lend an overall effect of exotic three-dimensionality to the figural work. Several pairs share an identical gilding motif, a wide band of scrolling incurvate oval forms, which appears on the back of some vases and as a decorative feature on the front of the vase section of others. The distinctions allow us to act as detectives, trying to attribute certain motifs and gilding to specific hands or schools of decoration. For instance, a pair of figural vases at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, flamboyantly painted, yet with very detailed costumes and gilt scrolls, were almost certainly painted in the same workshop as the pair of vases owned by the Museum of the City of New York and the small pair of vases now owned by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center (see fig. 3).

It may seem surprising that these ceramics illustrating scenes from an American novel were made in Europe, but it is necessary to remember that Uncle Tom’s Cabin was very popular overseas, selling hundreds of thousands of copies in England and France alone. Indeed, without this transatlantic connection, these objects could not have been made, because no American ceramic manufactory could create the quantities of inexpensive objects demanded by the popularity of the novel.[9] In Europe, by contrast, literacy rates were much higher than in America, and factories that had experience making souvenir-type wares were well established. The combination made Stowe’s novel and items dramatizing its characters and moments readily available.

The five potting towns that make up Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire were a natural place to create a plethora of Uncle Tom’s Cabin trinket wares, first, because there was already an English audience long accustomed to purchasing items with literary connections, and second, because the existing industrial base was large enough to support multiple factories producing similar items quickly and cheaply.[10] Furthermore, Stoke was ideally located near Liverpool and its huge port to facilitate nationwide distribution.

It therefore is not surprising to learn that Staffordshire manufacturers produced thousands of items based on Uncle Tom’s Cabin (fig. 11). These include figures that commemorate Uncle Tom meeting Eva on the boat; Eva with Topsy; Eva crowning Uncle Tom with a garland of flowers; Eva and Uncle Tom on her or his own scroll base. According to P. D. Gordon Pugh, at least eighteen different models are known, including ones of Aunt Chloe and George and Eliza Harris. Some of the figures are as small as 1 1/2 inches high; others are closer to 10 inches.[11] Such figurines turn up at public sales in England far more often than in the United States.

The Dudson factory, in the nexus of ceramic manufacturing at Stoke-on-Trent, is the only one that has been clearly identified as making Uncle Tom–related figures, based on factory records dating to the early 1850s. These list “Eva, Uncle Tom, Boat,” which had the typically stylized three-dimensional appearance of other flatback figures but with the addition of the “ebonized” figure of Uncle Tom placed next to the petite figure of Eva (figs. 12, 13). A Dudson family member who was present at excavations on the site of the old Dudson factory has identified fragments of a figurine of “Eva and Uncle Tom” in a banana-shaped boat, of which only two examples are known.[12]

By far the most popular figural group shows a very small Eva seated beside a huge figure of Uncle Tom. She is variously helping Uncle Tom read his Bible in a bower or “dressing” him with a garland of flowers, and Tom holds either his hat or a Bible in his left hand. The idea for the group comes from the 1852 London edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, illustrated with twenty-seven woodcuts by the famed caricaturist George Cruikshank.[13] The headpiece shows the two figures in positions very similar to the figural group, seated in a bower. The image had strong resonance for the English, because bowers formed part of their own gardens, and bower groups made in salt-glazed stoneware and glazed earthenwares were made as early as the 1740s. The Uncle Tom’s Cabin groups hark back to that eighteenth-century tradition.[14]

Whether depicting Eva and Uncle Tom, Eva and Topsy, or George and Eliza, all these Staffordshire figural groups are loosely and quickly modeled, and even more quickly decorated with overglaze enamels. The palette of the figures is typically bright, and the figure of Uncle Tom is usually lustrously black, with exaggerated lips and mouth. All of the figures share flat backs, abstractly painted surfaces, idealized faces, and the exploitation of “exotic” or “foreign” negroid features. By mass-producing quantities of such wares and decorating them minimally, manufactories such as Dudson’s could capitalize on momentary fads among the newer consuming classes with their reasonably priced wares.

Staffordshire manufacturers also had a long history of producing so-called ABC plates, that is, plates with borders and transfer-printed with images above brief mottos. Intended not for use but for playful instruction, they were meant to stimulate youngsters to think good religious and moral thoughts. Many such plates have been found reproducing scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, most of which are transfer-printed with direct copies of Cruikshank’s illustrations for the 1852 edition, such as “Eva Dressing Uncle Tom,” shown on a mug, and a plate with a visual interpretation of Uncle Tom’s cabin, true to Stowe’s novel right down to the portrait of George Washington hanging over the mantel (figs. 14, 15). Other plates show signs of being copies of copies of copies, evident because of the thick outlines and wavy printed backgrounds on the faces of the characters, seen, for example, in a plate illustrating “Eva and Topsy.” Manufacturers enjoyed making these plates with variegated shoulder molding because it enabled them to charge a little extra for the plates without doing anything complicated.[15]

A favorite topic for the ABC treatment repeats the imagery found on the French vases discussed earlier: Eliza’s crossing of the Ohio, a small moment in the book but one whose drama is beautifully encapsulated in Cruikshank’s illustration (fig. 16). In a relatively early version, circa 1853, we have “Eliza Crossing the Ohio on the Freezing Ice”; a later version with a more degraded print bears a new caption: “Lizzy’s Bridge: The Article Exhibits the Dominion of Maternal Love.”[16]

“The Death of Uncle Tom” is not often seen, but its imagery recalls an earlier ceramic item made by the antislavery advocate Josiah Wedgwood. As early as 1780, Wedgwood introduced little plaques that looked as though they were made in ancient Greece. They clearly depict a slave on bended knees, his arms shown in prayer to an unseen God, below the motto of the British Anti-Slavery Society, “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” Such items were mounted in gold and worn as jewelry, such as a stick pin. The slave’s image, representing a repressed cry for dignity and recognition, was often copied, albeit with some changes, by other Staffordshire manufacturers, using the new technology of lithography to create transfer-prints. Early-nineteenth-century drabware cups and saucers and unusual bone china wares such as a souvenir shoe and chamberstick, both made about 1835, serve as similar small antislavery tokens. Here the motto from the Wedgwood era has been changed and now reads, “REMEMBER THEM THAT ARE IN BONDS.”[17]

The 1852 publishing contract between John Jewett of Boston and Harriet Beecher Stowe gave Stowe only 10 percent of the novel’s overall sales, but Jewett agreed to “invest” another 10 percent in advertising the book. He agreed to “employ agents every where, to spare no pains nor expense nor effort to push the book into an unparalleled circulation.” The contemporary historian Francis Lieber wrote, “It [Stowe’s novel] will enter largely into exhibitions of paintings and possibly statuary. It will have its music.”[18]

The tantalizingly vague mention of “statuary” based on the novel allows us to imagine marble figural groups based on illustrations from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which would later be translated into parianware ceramics (fig. 24).[19] It is uncertain what parianware models of the figural group survive; a preparatory drawing of Eva and Uncle Tom dating to about 1856–1857 is recorded in the factory archives of the manufactory at Royal Worcester.[20] Stowe herself (fig. 25) was the subject of a commemorative mug, which bears the legend “Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe/AUTHOR OF UNCLE TOM'S CABIN” (fig. 26). Stowe’s image dominates the central reserve, presenting her as a national—or international—hero surrounded by figures from Uncle Tom’s Cabin as if they were supporting figures in her personal crusade against slavery. It is an amazing artifact, and one that advertises Stowe’s household name recognition across international boundaries, the first time that a literary figure and a woman, no less, was so commemorated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wong Curator of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for the inspiration to examine more closely these fascinating figural groups, and Leah C. Dilworth, chair of the English Department at Long Island University, with whom this essay was first imagined. A version of this essay was presented with Dilworth at the

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (New York: Bantam, 1981), p. 176.

Ibid., p. 58.

Although unmarked, the vases can be from no place other than Limoges. Many Limoges factories made decorative wares that featured figures either from popular contemporary literature and drama or of newsworthy appeal such as politicians, preachers, sportsmen, monarchs, and so forth. These were meant to be of momentary fashionable interest, but they were better looking than very cheap fairings. Limoges, more than factories in Paris or Bohemia, produced vases in two sizes. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen discusses a pair of similar vases from the collection of the Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey, in her essay “Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramics and Glass in New York City,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, edited by Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), p. 330, no. 252, color ill. p. 537. Frelinghuysen cites Limoges rather than Paris as the likely place where these vases were made.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, La Case de l’Oncle Tom, translated by Louise Swanton-Belloc (Paris: Charpentier, 1853). As Adolphus M. Hart notes in Uncle Tom in Paris, the French rejected the high moral tone of Stowe’s novel, preferring to show the bloodthirsty melodramatic elements of the book; Hart, Uncle Tom in Paris; or, Views of Slavery Outside the Cabin (Baltimore: William Taylor and Company, 1854). Even popular American theatrical interpretations relied on these same elements to draw crowds into their halls.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Boston and London: John P. Jewett and Company, 1853).

See Dell Upton, “Inventing the Metropolis: Civilization and Urbanity in Antebellum New York,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, edited by Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000),, pp. 3–45.

See ibid., fig. 16, for the illustration of the Haughwout salesroom; the details about the company’s decorating staff can be found in Margaret Brown Klapthor et al., Official White House China, 1789 to the Present, 2nd ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), p. 77.

Klapthor, Official White House China, p. 82, says that two services decorated for Abraham Lincoln were completed with imported blanks from various French factories.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain, 1770–1920, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), suggests that the factories founded in America before the last third of the nineteenth century were prevented from enjoying widespread success through a combination of technical, marketing, and management flaws in their businesses.

The Bow factory had been making porcelain figures based on contemporary prints of famous actors and actresses since the 1750s, and the Derby factory made twelve bone china representations of William Coombs’s hilarious buffoon Dr. Syntax based on differing episodes in his travels.

P. D. Gordon Pugh, Staffordshire Portrait Figures and Allied Subjects of the Victorian Era (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1970).

The plethora of figures and the Dudson find were discussed via email at length with Miranda Goodby, beginning on January 5, 2001.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (London: J. Cassell, 1852).

Obviously, bowers were not and are not exclusively English, but the English held to their garden traditions and associated an orderly garden to an orderly, morally correct life.

See www.iath.virginia.edu/utc for a fairly complete list of plates found with Uncle Tom scenes.

See ibid. This latter image particularly helped stir moral outrage against slave-holding and assisted Stowe’s abolitionist cause. Stowe herself said she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin because the true crime of slaveholders lay in their dividing families and destroying homes. The cabin in the novel is a symbol of good, holy, moral love despite the ignorance of its occupants.

For a full discussion of these items, see Sam Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 80–109.

Quoted in Joan D. Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 224.

“Inexpensive Parian-ware sculptures had become favorite domestic adornments by this period and had proliferated on the market; one advertisement run repeatedly by a Maiden Lane proprietor boasted of more than 400 selections”; Thayer Tolles, “Modeling a Reputation: The American Sculptor and New York City,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, edited by Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), p. 161.

See Paul Atterbury and Maureen Batkin, eds., The Parian Phenomenon: A Survey of Victorian Parian Porcelain Statuary and Busts (Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1989), which includes this wonderful sketch from the factory archives. Although the image is not very distinct, it clearly shows Eva in an almost angelic state on Uncle Tom’s knee. For the pitcher, see www.iath.virginia.edu/utc.