Robery Carey Long Jr., Hampton Mansion, 1838. Watercolor on paper. (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, all objects and photos are courtesy of Hampton National Historic Site, National Park Service.)

William Russell Birch, “Hampton the Seat of Genl. Chas. Ridgley, Maryland,” The Country Seats of the United States of North America, Springland near Bristol, PA, 1808. Engraving. 7" x 8 1/2".

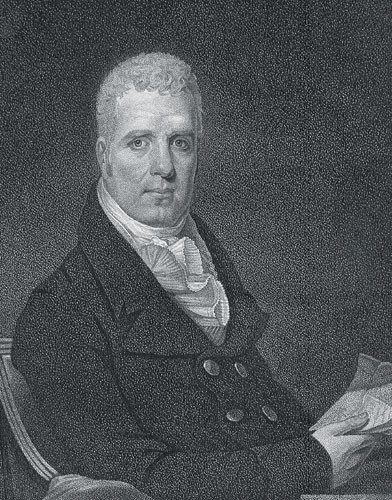

Goodman and Piggot, Charles Carnan Ridgely (1760–1829), ca. 1817–1822. Engraving. 6" x 4 3/4".

Plateau with figures of gods and goddesses, Niderviller, France, ca. 1792. Porcelain. H. of figures approx. 8 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Diana Edwards.) Plateaux were mirrored trays on small feet with silver or silver-gilt galleries; larger versions were divided into three or more sections. The one shown here, which included twenty-nine porcelain figures, was ordered by Edward Lloyd IV in 1792. Comprising five parts, it extended to nearly eight feet in length.

Dish, China, ca. 1750–1775. Porcelain. L. 16". NPSHAMP 21464. (Loan returned; no longer in collection of Hampton NHS.) Although this Chinese export was not part of Hampton’s collection during Captain Ridgely’s tenure, famille rose Chinese porcelains were popular with wealthy Maryland families, including the family of Charles Carroll the Barrister.

Fruit cooler, Caughley factory, Shropshire, England, ca. 1775-1779. Soft-paste porcelain decorated in the Dresden pattern. H. 9". NPSHAMP 11518. This cooler is one of a pair.

Dessert dish, Coalport factory, Shropshire, England, ca. 1820. Bone china, enamel painted in cobalt blue with gilding. L. 13". NPSHAMP 40353. At the center of each piece from this service is the Ridgely family crest.

Detail of the Coalport factory mark on the reverse of the dessert dish illustrated in fig. 7.

Basket and stand from dessert service, Davenport factory, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1805–1810. Bone china, enamel painted and gilded. H. of basket 6 1/2". L. of stand 10 3/4". Marks: on both, a red anchor surmounted by “Davenport” in a banner; the pattern number or painter’s mark “208.” NPSHAMP 1240, 1244.

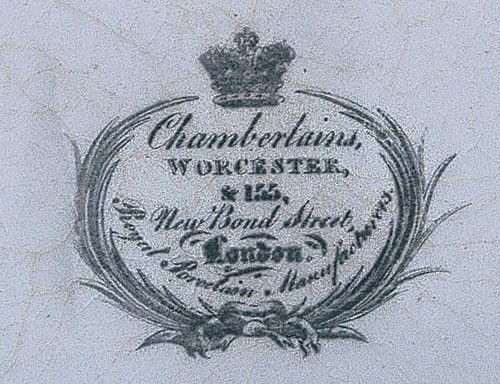

Dish from dessert service, Worcester Porcelain Manufactory (Chamberlain’s factory), England, 1811-1820. Soft-paste porcelain, painted with cobalt blue and gilded. L. 12 1/2". Mark: “155” (pattern number). NPSHAMP 10207.

Detail of Chamberlain’s Worcester mark on the reverse of a square dessert dish from the same service as the dish illustrated in fig. 10.

Vegetable dish and cover, Spode, Staffordshire, England, 1833-1847. Stoneware, with green enamels and gilding. H. (with handle) 6", L. 8 3/4". Mark: Copeland & Garrett “1666” (pattern number). NPSHAMP 9003a, b.

Serving dish from a dinner service, decorated by Feuillet, Boyer, Blot, and Hébert, Paris, ca. 1825. French porcelain, with enamel and gilding. L. 9 1/8". Mark: “Feuillet.” NPSHAMP 4158. At the center of each piece in the set is the Ridgely family coat of arms.

Ewer and basin, China, ca. 1750. Porcelain, with underglaze blue painting. H. of bottle 10 1/2"; D. of basin 12". NPSHAMP 4646, 4647. These Chinese exports were not part of the Ridgely estate but a museum purchase appropriate to furnishing the master bedchamber to circa 1790.

Pitcher, England, ca. 1805–1815. White stoneware, with brown dipped surface decoration. H. 6 1/4". NPSHAMP 4178. Pitchers made for the American market were produced by several Staffordshire and Yorkshire factories and are almost always unmarked. This example bearing sprig-relief American motifs was a museum purchase, relating to sherds found archaeologically at Hampton and in 1829 estate references.

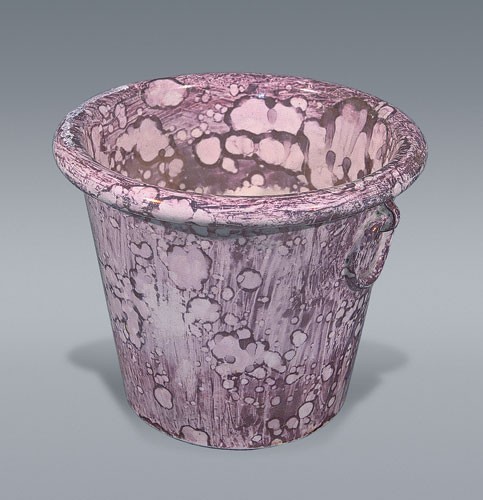

Cachepot, England, ca. 1810. Pearlware, with “moonlight luster” decoration. H. 5". NPSHAMP 10217. This cachepot, one of a pair acquired by the park in 1982, is typical of Charles Carnan Ridgely’s purchases in this period and helps to interpret his significant horticultural interest. Luster-decorated earthenwares are rarely attributable to a specific manufacturer.

Partial tea/coffee set, decorated by Feuillet, Boyer, Blot, and Hébert, Paris, ca. 1825. Porcelain, with elaborate gilding. H. of tea/coffee pot 8 3/8". NPSHAMP 21413, 21419, 21424, 21425, 21426. (Loan returned; no longer in collection of Hampton NHS.)

Fruit basket, Paris, ca. 1825. Porcelain, with gilding. H. 7", D. 9 3/8". NPSHAMP 4773.

Stand with pots de crèmes, Paris, ca. 1810–1830. Porcelain, with enamel decoration. H. of stand 15". H. of each pot de crème 4 3/8". The stand comprises five pieces held together by a metal rod. NPSHAMP 41998a–e, 41979–41989.

Covered butter dish on stand, France, ca. 1810–1830. Porcelain, with sprig or cornflower decoration. L. 12". NPSHAMP 42005.

Teapot and lid, probably Worcester, Flight, and Barr, or Caughley (Shropshire), England, ca. 1790. Soft-paste porcelain, with sprig or cornflower decoration. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, private collection).

Plate, cup and saucer, Haviland & Company, Limoges, 1870-1890 (plate) 1800-1812 (cup and saucer) Plate: Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/2". Mark: “H & Cie, L.” Cup: Hard-paste porcelain. D. 2 1/8". Mark: “Halley.” Saucer: Paris porcelain. D. 5". Mark: in script, “Halley.” NPSHAMP 9483, 9443, 9701. A group of teawares from two different periods was purchased by the Ridgelys as replacement pieces for an earlier service.

Plate, cup, and saucer, attributed to Feuillet, Boyer, Blot, and Hébert, Paris, ca. 1830–1834. Porcelain, with gilding. D. of plate 8 3/4"; H. of cup 2 1/2"; D. of saucer 5 1/2". NPSHAMP 4036–4077. This set, with a green band and floral center, was selected by Eliza Ridgely on a trip to Paris in October 1834.

Mantel clock, France, ca. 1840–1850. Porcelain base with enamel painting, surmounted by biscuit porcelain figures. H. 17 3/4". NPSHAMP 4280a, b. Eliza Ridgely appears to have purchased this clock on one of her trips to Europe. Photos of the music room from the late nineteenth century show the clock on the mantel, where it is today.

Pair of vases, China, ca. 1837–1840. Porcelain, decorated in the Rose Canton style. H. 48 3/4". NPSHAMP 1025, 1026. A Caroline Butler of New York brought a smaller pair of vases of this variety back from her trip to China in 1837 (David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade [New York: New-York Historical Society, 1984], p. 122).

Vase, China, ca. 1840–1850. Porcelain, decorated in the Rose Canton style. H. 20". NPSHAMP 1172. This large vase, with elaborate applied decoration and a cover surmounted by a foo dog finial, is one of a pair.

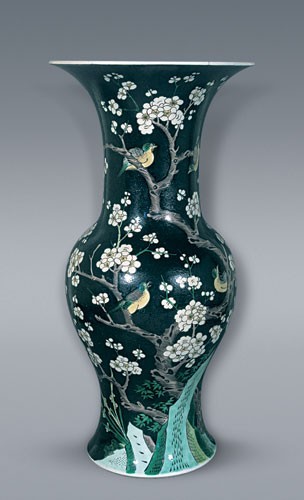

Vase, China, ca. 1860–1870. Porcelain. H. 17 7/8". NPSHAMP 10291. One of a pair, this large vase is decorated in a black ground with white prunus blossoms and translucent enamels in the famille verte style. The shape is known as yen yen and the vase is like one Warren Delano, a China trade merchant, brought back to New York in 1870. (Howard, New York and the China Trade, p. 134.)

Bowl, China, ca. 1785–1800. Porcelain. D. 15 1/2". NPSHAMP 21445. This late Qing dynasty bowl is decorated with a green enamel floral border and a cartouche, painted in sepia, of a landscape.

Bowl, China, ca. 1800–1820. Porcelain, with enamel and elaborate gilding. D. 12 1/16". NPSHAMP 17629.

Chamber pot and cover, China, ca. 1825–1835. Porcelain, with green enamel and gilding. H. 8 1/4". NPSHAMP 10236.

Bottles, China, ca. 1835–1850. Porcelain. H. 6 1/2". NPSHAMP 17630, 17631. These bottles are enamel decorated with the black butterfly motif in the Rose Canton style.

Punch bowl, China, ca. 1850–1870. Porcelain. D. 25". NPSHAMP 4770. This large bowl, decorated in the Rose Canton style, was not part of the Ridgely family possessions but a later gift. It is, however, very much in the taste of the grand purchases Eliza and John Ridgely made in the mid-nineteenth century.

Pair of vases, France, ca. 1850. Porcelain. H. 12 3/4". NPSHAMP 10246, 10247. According to late-nineteenth-century photos, these vases, decorated with bleu céleste ground and reserve panels painted with flowers, sat on the mantel of the music room, where they still reside.

Box with medallions of the heads of Roman emperors, ca. 1778–1800. Wood (box) and plaster of paris (medallions). 12" x 8". NPSHAMP 22538. This box of portrait medallions, part of a set, was probably purchased by John and Eliza Ridgely on one of their European tours.

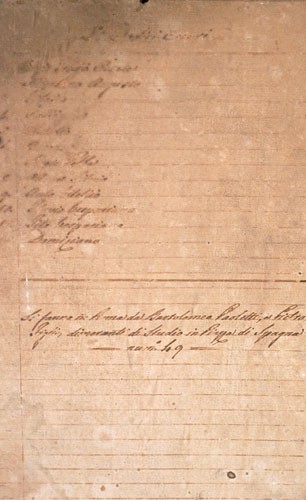

Handwritten list of the names of the emperors depicted on the medallions illustrated in 34. The list is affixed to the back of the box.

Cheese wheel stand, possibly Staffordshire, England, ca. 1850–1860. Earthenware. L. 17". NPSHAMP 10234. Transfer-printed with an underglaze blue willow pattern, this stand seems especially appropriate to find at Hampton, which had its own dairy dating from the eighteenth century.

Jug, Worcester Royal, England. Porcelain Co., Ltd., 1884. Porcelain with turquoise scale ground and twisted lizard handle in gilt. H. 11". Marks: sepia crowned circle; date letter "V" incised pattern number “260”; impressed “9a.” NPSHAMP 17713. These Japonisme-style vases were the height of fashion at the period.

Two vases, England, ca. 1870. Earthenware, painted in Greek revival style. H. 13 7/8" and 9 1/2". NPSHAMP 10210, 21459.

The most prominent family in Baltimore County, Maryland, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was the Ridgely family. By the eighteenth century, it had amassed twenty-four thousand acres of land and built one of the largest and grandest mansions in the country (figs. 1, 2). Hampton Hall, or Hampton Mansion as it is now known, was home to Ridgely families from 1788 to 1948, when it became part of the National Park Service.

The individual styles of each succeeding generation to occupy Hampton are reflected by, among other things, their ceramics. The complete saga requires examination of each generation, but here we concentrate on the period during which most of the ceramics used by the family were purchased, between the last decade of the eighteenth century and about the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The Establishment of an Empire, 1761–1790

The Ridgely family has its roots in the seventeenth century with one Robert Ridgely (1616–1681), a barrister known to have emigrated from England about 1634.[1] By 1666 he was established as a clerk of the Maryland Council and he held other offices in the province thereafter. The early Ridgelys were plantation owners but some—such as Charles the Planter (d. 1705), who died with debts that nearly equaled the value of his estate—are shrouded in obscurity.

It is with Charles’s son, Colonel Charles Ridgely (1700–1772), that the history of the family begins to come to life. By 1760 the colonel began moving his interests away from the plantation life of Anne Arundel County, Maryland, to the area north of Baltimore. He purchased one hundred acres situated just north of “Northampton,” a tract acquired in 1745, where he established with his two sons, John and Charles, an ironworks put into blast in 1762. The rich local deposits of iron ore combined with tax incentives encouraged by the local government and the British Crown made bar and pig iron in the Chesapeake area a major industry. To help sustain family shares in the iron industry Colonel Ridgely deeded some two thousand acres to his younger son, Captain Charles Ridgely (1733–1790), who effectively undertook the management of the ironworks.

Captain Ridgely’s early career had been at sea, possibly on one of his father’s ships looking after the family’s commercial interests. He later assumed command of the Baltimore Town, a ship transporting raw materials such as iron and agricultural products from the colonies to London, where they would be exchanged for finished goods. In 1760 Captain Ridgely married Rebecca Dorsey, the daughter of another wealthy ironmonger in Anne Arundel County. By 1763 he had returned from sea and began diversifying his commercial interests to include, in addition to the Northampton ironworks, a general merchandising business in Baltimore and the operation of several mills, quarries, plantations, and at least one large orchard.

The Revolutionary War and other factors hurt trade with Britain and substantially changed the focus of the iron business, moving it into camp kettles, shot, and cannon production. Essentially a pre-Jeffersonian Democrat, after the war Ridgely espoused the interests of the common man, supported paper money, and campaigned for agrarian reform. He served in the Maryland House of Delegates and was popular with his constituents.

Captain Ridgely’s business acumen had made him a very wealthy man, and, as other Marylanders in his position were doing, in 1783 he embarked on building a fine country seat, what would become Hampton Hall. The work on the mansion, completed with the labor of slaves, indentured servants (often Irish), and paid artisans, took seven years. Every aspect of the project was overseen by Captain Ridgely, who was nicknamed “the Builder.” The end result was a magnificent five-part, three-story Georgian building made of stuccoed stone with a prominent octagonal cupola rising thirty-four feet above the roof. The cupola, unique in American federal architecture, might have been inspired by the one atop Castle Howard in Yorkshire, England. Unfortunately, Charles Ridgely did not live to enjoy his splendid creation. He died suddenly in 1790, without offspring or a household inventory.

Rebecca Dorsey Ridgely decided not to remain in the large new house, and in 1791 she reached an agreement with her husband’s nephew Charles Carnan whereby she would exchange Hampton Hall for a smaller house known as “Auburn.” A curious condition in Captain Ridgely’s will required all four of his nephews to adopt the surname of Ridgely if they wished to inherit. Thus Charles Carnan became Charles Carnan Ridgely.

It is with Charles Carnan Ridgely (1760–1829) and the furnishing of Hampton that the picture of grand living in Maryland in the last decade of the eighteenth and the first three decades of the nineteenth century comes into view (fig. 3). Charles Carnan Ridgely was a brigadier general in the state militia by 1796, married Priscilla Dorsey (1762–1814), the younger sister of his aunt Rebecca. Known as General Ridgely, he sat as director on numerous local institutions and was instrumental in establishing the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Somewhat surprisingly, considering his uncle’s political views, General Ridgely became a leading federalist and promoted the interests of industry and large property ownership. He was elected to the Maryland legislature (1790–1795), the state senate (1796–1800), and served three consecutive terms as governor beginning in 1815. His administration set many precedents, among them establishing free education.

Of particular importance to the image of landed gentry was the presentation of the dining table, and in this Charles Carnan Ridgely excelled. At least by 1818, during his tenure as governor, Ridgely was employing a French chef, who moved between Annapolis, the Baltimore town house, and Hampton Hall in seasonal shifts, but his table and lands were widely known before that. In 1805 the English historian Richard Parkinson wrote in A Tour of America: “The General’s land is of great note . . . his cattle, sheep and horses & c. of a superior sort. . . . He is very famous for his race-horses. . . . He is a very genteel man, and is said to keep the best table in America. . . . I have often experienced his hospitality.”

Although he was given full credit for his gardens and table, perhaps justifiably, one wonders whether his wife had some responsibility for purchasing these objects, listed in the 1829 estate inventory:

4 Pieces of Platto glass

18 Platto images

3 Platto blocks

5 Pieces plated ware belonging to Eperne [sic]

1 Glass Eperne [sic]

$12.00

$ 3.00

$5.00

$15.00

The “images,” or figures for the table, were placed on a plateau or a surtout de table, a mirror on which the figures appear to be dancing around the table. These small earthenware or porcelain figures often took the form of gods and goddesses (fig. 4). Plateaux typically were seen only in America’s elite households and conveyed the classical education of the times. Of George Washington’s table, for example, Rosalie Stier Calvert wrote, “Yesterday we dined at the President’s House. I have never seen anything as splendid as the table—a superb gilt plateau in the center with gilt baskets filled with artificial flowers. All of the serving dishes were solid silver. . . . The plates were fine French porcelain.”[3] In the fall of 1790, when the presidential entourage moved from New York to Philadelphia, Washington’s secretary, Tobias Lear, wrote, “The large Images stand on the Side Boards in the Dining Room [of the Philadelphia house] . . . the small Images can be put in the closets with the China.”[4] Theophilus Bradbury, a Massachusetts congressman, attending one of the president’s Thursday dinners, said, “In the centre [of the table] was a pedestal of Plaster of Paris with [biscuit porcelain] images upon it, and on each end figures, male and female of the same. It was very elegant and used for ornament only.”[5] Edward Lloyd IV’s table at Wye House, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, danced with images of twenty-nine gods and goddesses, ordered from his London agents in 1792.[6]

On April 22, 1796, Charles Carnan Ridgely purchased “Table Ornaments” totaling three hundred dollars[7]—regrettably, they have not survived. Among the contents of his Baltimore town house on Gay Street were “1 Glass plated Plateau Tray, Plateau Blocks & Plateau.”[8]

The 1829 estate inventory of Charles Carnan Ridgely lists eighteen plateau images. There is no way of knowing what the images were made of, but they probably were either French or English porcelain, not plaster of paris or alabaster, as some figures were erroneously described.[9] Those of both Edward Lloyd IV and George Washington were French porcelain, which was readily available in London in the early 1790s, just after the French Revolution.[10]

Other famous tables boasted plateaux and figures to adorn them. Thomas Jefferson used several plateaux while in France and while he was president continued to embellish his tables at Monticello (and presumably in Philadelphia), as well as in Washington. As an arbiter of taste and fashion Jefferson also made purchases for his friends, among them Abigail Adams, for whom he “hunted down French dessert platters of a kind she had her heart set on for her dining table.”[11]

Although numerous fine dinner and tea sets from the first quarter of the nineteenth century are in the collection at Hampton, few ceramics survive from the eighteenth century. Those that do include a set of Chinese export famille rose–decorated porcelains, which does not have a history in the family at Hampton (fig. 5), and a pair of porcelain fruit coolers made by the Caughley factory in Shropshire, which does (fig. 6).

The ceramics purchased by families in colonial America prior to 1790 were primarily Chinese exports or English earthenwares, delft, creamware, and pearlware. Due to either a surfeit of the former or a greater availability of the latter, by 1790 one begins to see a preference for English and French porcelain over Chinese porcelains, which by then were considered old-fashioned. Charles Carnan Ridgely’s purchases of English porcelain during his tenure at Hampton shows he was one of the earliest Maryland families to do so. Unfortunately, the brief descriptions in the 1829 estate inventory taken after his death—“1 Set English China (42 pieces) $80.00”[12]—make it impossible to identify individual items. English china sets known to have been at Hampton in that period include ones made by Coalport (figs. 7, 8), Davenport (fig. 9), and two different sets of Worcester (figs. 10, 11) and Spode (fig. 12).

Another ceramic entry in the 1829 estate inventory was “1 Set French China (68 pieces),” also valued at eighty dollars. This is a rare instance in which such a generic inventory description can reasonably be assigned to particular objects, in this case the bold set of “Feuillet” porcelains, made in Paris and decorated with the Ridgely coat of arms, that are in the dining room at Hampton (fig. 13). In cupboards holding literally dozens of dinner services, tea sets, and accessory pieces, however, one must use other means to distinguish the purchases of Charles Carnan Ridgely from those of the dynamic Eliza Eichelberger Ridgely (1803–1867) of the next generation.

Listed as part of the 1829 estate inventory were “16 Blom Monge moulds,” or blanc mange molds, which are no longer in the collection, as well as a “Black Tea Pot,” of the basalt so popular at the time. One set of 297 pieces of “Blue Canton”—clearly the service the family used informally—was valued at two hundred and fifty dollars (fig. 14).

The Gay Street house sale after General Ridgely’s death included another set of Canton china, a sixty-eight-piece dessert set of English china, and another dessert set in French porcelain, none of which can be identified with any certainty. “2 White & Brown Pitchers,” also among the Gay Street inventory, were probably similar to the one purchased for Hampton by the museum staV in order to restore the inventoried objects (fig. 15). The circa 1810 pearlware cachepot with “moonlight luster” decoration (fig. 16) is in the style of Charles Carnan Ridgely’s purchases.

By the early part of the nineteenth century French porcelain was very fashionable in Maryland, and most of the wealthy families—the Ridgelys among them—possessed at least some examples of it. Somewhat surprising, considering it was on the heels of the French Revolution, Philadelphia newspapers carried advertising for French porcelain in the 1790s. Pasquier and Company, at 91 South 2nd Street, for example, advertised “French China” in the Aurora and General Advertiser on February 18, 1796: “Received from different factories in France. . . . Table sets, dessert sets, tea sets . . . & flower pots of different shapes . . . china figures, hyacinths with stands. . . .”

In 1806 and 1807 Rosalie Stier Calvert expressed her desire to have both dinner and tea services in French porcelain, pointing out that it was used at the White House and at the English ambassador’s residence.[13] Stephen Decatur’s estate inventory of 1820 included twenty dozen pieces of “Fine French China,” valued at eighty dollars, and ten dozen French china plates, valued at one hundred and twenty dollars.[14] The 1827 estate inventory of John Eager Howard (1752–1827) listed French “blue and gold” porcelain as well as one hundred and fourteen pieces of “French China gilt insides.”[15]

One wonders how much influence the marriage of Elizabeth (“Betsy”) Patterson, the beautiful daughter of Bank of Baltimore president William Patterson, to Napoleon Bonaparte’s younger brother Jérôme had on the French porcelain market in Maryland. Betsy met and married Jérôme Bonaparte in 1803, during the Baltimore “season.” Incensed that his brother contracted a marriage without his permission, Napoleon insisted that Jérôme return to France or forfeit the crown of Westphalia. In 1805 they sailed for France, but Betsy was denied entry. Jérôme made the decision to obey his brother and she continued on to England, where she gave birth to their son, Jerome. Their marriage was annulled in 1806, and by the end of 1807 Jérôme had remarried and was occupying the throne of Westphalia. Betsy returned to Baltimore, where she was known as Madame Bonaparte and continued to live in the style of French royalty. Her numerous sets of French porcelain, many of which were purchased after her marriage was annulled, are now in the Maryland Historical Society.[16]

Perhaps the most beautiful example of fine French porcelain in the Hampton collection is the ornately gilded tea/coffee set decorated by the Paris workshop of Feuillet, Boyer, Blot, and Hébert (1817–1834) (fig. 17). The Feuillet workshop, among the most prestigious of the Paris porcelain decorating studios, also provided Betsy Patterson Bonaparte with some very handsome pieces. Other Paris porcelain at Hampton is a partial dessert set including the fruit basket illustrated in figure 18.

Charles Carnan Ridgely purchased a large dinner service and numerous pieces of sprig floral porcelains (figs. 19-21)—some French and English but most of them French. Although some remain at Hampton, the majority has been given to the Maryland Historical Society or has been otherwise dispersed. The sprig porcelains with cornflower enamel decoration were very popular with prominent Americans such as Benjamin Franklin, Christopher Gore, Thomas Jefferson, and John Tayloe III.[17] The duc d’Angoulême’s Paris manufacture was commonly associated with the cornflower sprig motif, although many factories used it to decorate their porcelains.

Charles Carnan Ridgely was still acquiring furnishings for Hampton as late as 1828, a year before he died, as he purchased several costly items at the estate sale of his close friend John Eager Howard.[18] Ridgely’s will, dated April 28, 1828, contained a provision to free more than three hundred slaves listed as part of the estate at the time of his death, a decision that would affect the fortunes of the estate in years to come. After his death, the Ridgely family’s great empire was divided among the general’s eleven surviving children. The eldest, Charles Carnan Ridgely Jr., had been groomed to take the reins of the Hampton estate, but he had died in a riding accident in 1819 at age thirty-six. His brother John Carnan Ridgely (1790–1867) assumed ownership of the mansion and approximately four thousand surrounding acres, a fraction of the estate’s original twenty-four thousand.

Unlike his brother Charles, John Carnan Ridgely was unprepared to be master at Hampton, nor was his life marked by the ambition and desire for public service characteristic of the mansion’s two previous masters. His first wife, Prudence Gough Carroll of the Mount Clare Carrolls, died young, as did their six infant children. His second wife, Eliza Eichelberger Ridgely (1803–1867), was a wealthy Baltimore woman whose family, despite the name, had no apparent connection to the Ridgely family into which she married. Eliza, who by all accounts was beautiful, charming, and accomplished, had attended boarding school in Philadelphia at Miss Lyman’s Institution. In 1818 the Philadelphia portraitist Thomas Sully painted her playing the harp; coincidentally, he also painted likenesses of both her future husband, John Ridgely (in 1841), and her father-in-law, Charles Carnan Ridgely (in 1820). It is said she captivated the marquis de Lafayette on his visit to Baltimore in 1824 with her playing of the harp, and they corresponded thereafter. When John and Eliza visited France in 1833–1834, they were guests at La Grange, Lafayette’s home.

John and Eliza had five children, two of whom survived to adulthood.[19] Eliza’s daughter’s diaries from the 1840s reveal the seasonal migration between Hampton and the house in town, the tutoring of the children, and illnesses that resulted in death for two of the children. (The diaries do not mention how the third child died.) The Ridgelys were at Hampton every year from approximately April to October, returning to Baltimore for the Christmas holidays and house parties. The house in town during this generation was at 25 Hanover Street, near the harbor.[20]

John and Eliza Ridgely traveled widely, taking several extended tours of Europe: 1833–1834, 1846–1848, 1852, and 1859. It was on tours to Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, Malta, and Turkey that Eliza bought many decorative objects to adorn Hampton. It was a popular time for wealthy Americans to travel abroad collecting objects of culture and refinement. Philip Hone, mayor of New York in 1825 and a dedicated diarist (1828–1851), declared, “All the world is going to Europe.”[21]

John and Eliza bought two sets of French porcelain (figs. 22, 23), although it was Eliza who steered the grand ceramic acquisitions—the large bowls and the numerous, impressive Chinese vases, for example, which apparently were purchased abroad. Accounts record diverse purchases including French porcelains, English silverware and carpets, Turkish mirrors, mantel clocks (fig. 24), Venetian glass, Bavarian tumblers, and numerous engravings of European views.[22] In Paris Eliza purchased two leopard skin rugs, which she placed in the Great Hall, where they resided jaw to jaw for the next one hundred years. Nineteenth-century Rose Canton jars standing four feet high (fig. 25), a large pair of Rose Canton vases with attached lids (fig. 26), and a pair of large vases with a black ground (fig. 27), all currently in Hampton’s music room, were choices made by John and Eliza when they were traveling overseas. Other large bowls dating to the late Qing period (figs. 28, 29) are impressive monuments to Eliza’s superior decorative style. Even the chamber pots and dressing table bottles—in gilded and enameled Chinese porcelain—were fashion statements (figs. 30, 31). A large Rose Canton punch bowl (fig. 32) on view in the hall, though a later gift to Hampton, reflects Eliza Ridgely’s taste. A pair of French porcelain vases on the mantel in the music room (fig. 33) might have been acquired when the Ridgelys were in Paris. A set of plaster cast relief models of the heads of the Roman emperors (figs. 34, 35), which date to the last quarter of the eighteenth century, could have been purchased by John and Eliza when they were abroad, or even by Charles Carnan Ridgely.

A large English willow pattern cheese wheel stand (fig. 36) dating to the mid-nineteenth century speaks to a lifestyle at Hampton that would, after the Civil War, be eclipsed by reversals of fortune. By 1850 the Hampton estate had moved from an industrial to an agrarian economy. Fortunes had further declined due to the need to hire servants after the will of Charles Carnan Ridgely freed the slaves in 1829. John and Eliza had to engage servants as well as buy and/or rent a new slave population. Eliza’s fortune assured that Hampton was still a showplace during her lifetime.

The great era at Hampton ended with the death of Eliza Ridgely in 1867. A few examples of contemporary art pottery exist from later in the century during the tenure of Hampton’s fourth master, John and Eliza Ridgely’s son Charles Ridgely: a turquoise ground lizard jug made by the Minton factory (fig. 37) and two vases in Greek revival style (fig. 38), both from about 1870. The family continued at Hampton until the mid-twentieth century.

Hampton National Historic Site, including the mansion, home farm with dairy, formal gardens, and twenty-three dependency buildings is open to the public, with furnished period rooms that bring this important national landmark back to life, addressing the most significant periods of the estate’s history, from Captain Ridgely’s dynamic creation of a Maryland showplace in the eighteenth century to the denouement of his American dream after World War II.

Lynne Dakin Hastings, Hampton National Historic Site (Historic Hampton, Inc. in cooperation with the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1986), p. 3.

Estate Inventory of Charles Ridgely of Hampton, 1829, Maryland Hall of Records, Annapolis; copy in the archives of the Hampton National Historic Site. See also Lynne Dakin Hastings, “The Best Table in America”: Furnishing the Dining Room at Hampton (1810–1829), Historic Furnishings Report (National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1994), pp. 172–80.

Letter from Rosalie Stier Calvert to her father, H. J. Steir, dated March 13, 1819. Margaret Law Callcott, Mistress of Riversdale: The Plantation Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert, 1795–1821 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), pp. 343–44.

Susan Gray Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), p. 112.

Ibid.

For unknown reasons, two orders for figures were placed on the same day to two different London agents, Messrs. Thomas Eden and Co., and Oxley, Hancock and Co. The order to Thomas Eden and Co. reads: “Fashionable Ornamental Decoration to set of a Dining or Supper Table, that will accommodate 20 People with a Slides of the Images . . . ,” as quoted in Diana Edwards, Taste and Table: A Century of Ceramics in Early Maryland (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), p. 13.

Ridgely Papers, ms 692, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

These items sold for thirty-five dollars on October 1, 1829, at the sale following the death of General Ridgely. Also listed for sale were thirty-seven pieces of Liverpool ware, probably transfer-printed creamware. Archives, Hampton National Historic Site.

Edward Lloyd IV and George Washington both owned a number of biscuit porcelain figures made at Niderviller and Angoulême; these could have been described erroneously as plaster of paris or alabaster.

The order to Edward Lloyd’s London agents specified that the plateau images not exceed one hundred guineas. (A guinea was equal to one pound and one shilling, or twenty-one shillings.) The 1796 inventory of Edward Lloyd IV listed the value of the plateau and “29 Alabaster Images” at seventy-five pounds. See Diana Edwards, “Gods and Goddesses: A Brief Note about a Set of Niderviller Figures in a Maryland Family,” French Porcelain Society Journal 2 (2005): 115–19. In the 1790s prices were still being quoted in either sterling or dollars, but a pound traded at approximately $4.50; www.globalfinancialdata.com/index.

David G. McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001), p. 347.

The quantities listed in various inventories are unreliable because upon the death of each master the contents of the house were divided among family members; some pieces were subsequently returned. Moreover, Hampton was entailed to the eldest son of each generation and many items were assumed to be part of those transfers.

Callcott, Mistress of Riversdale, pp. 138, 142, 157–58, 343–44.

Probate Court Records, District of Columbia Record Group 21, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

MFH5476.H851F9, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore. Howard, one of George Washington’s officers during the Revolution and hero of Cowpens (1781), also served as governor of Maryland (1788–1791) and as a United States senator; in 1816 he was an unsuccessful candidate for vice president. Two of his sons married two of Ridgely’s daughters. The total value of Howard’s real estate at the time of his death was more than one million dollars.

Diana Edwards, “English Aristocrats in Maryland Society,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 7 (1989): 91.

Hastings, “Best Table in America,” p. 146.

John Eager Howard Estate Sale (1828), ms 2450, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

The focus of this article does not include John and Eliza’s children, as by their generation the purchases of household furnishings declined with the family fortunes.

Lynne Dakin Hastings, introduction to Charles E. Peterson, Notes on Hampton Mansion, 2nd ed., rev. (College Park, Md.: National Trust for Historic Preservation Library Collection of the University of Maryland Libraries, 2000), p. xiv.

Wendy A. Cooper, Classical Taste in America, 1800–1840 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1993), p. 27.

Hastings, “Best Table in America,” p. xiv.