Easy chair, England or eastern Virginia, ca. 1745. Walnut with beech; original upholstery with later additions. H. 45 3/4", W. 30 1/4", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Matthew Pratt, Mary Jemima Balfour, Hampton,Virginia, 1773. Oil on canvas. 49" x 39 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society.)

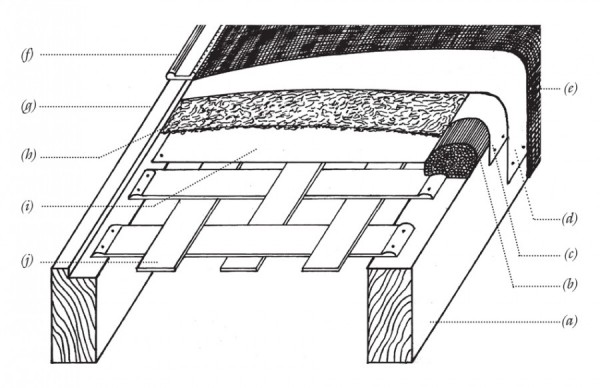

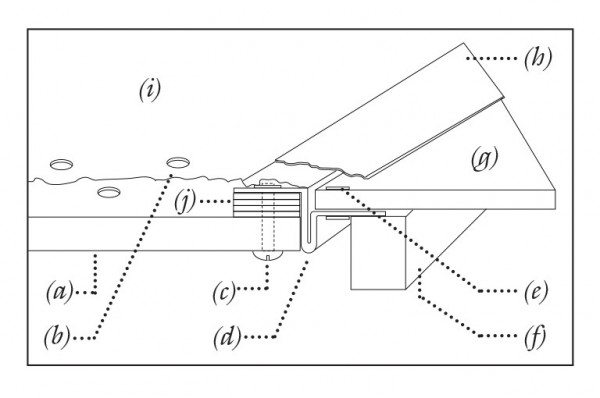

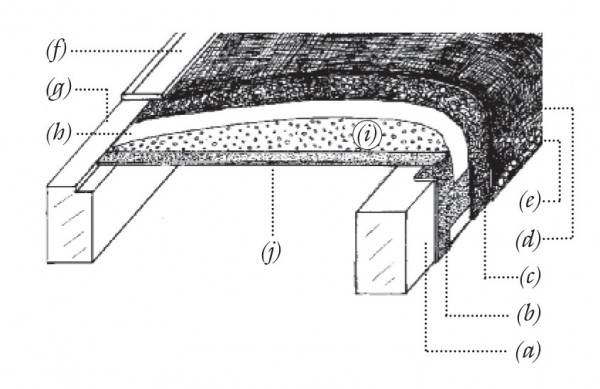

Illustration of a standard eighteenth-century approach to over-the-rail upholstery: (a) front seat rail, (b) straw or grass roll, (c) linen casing for roll, (d) top linen, (e) show textile, (f) removable shoe molding, (g) rear seat rail, (h) horse hair stuffing, (i) foundation linen, (j) webbing strips. (Drawing, Leroy Graves; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

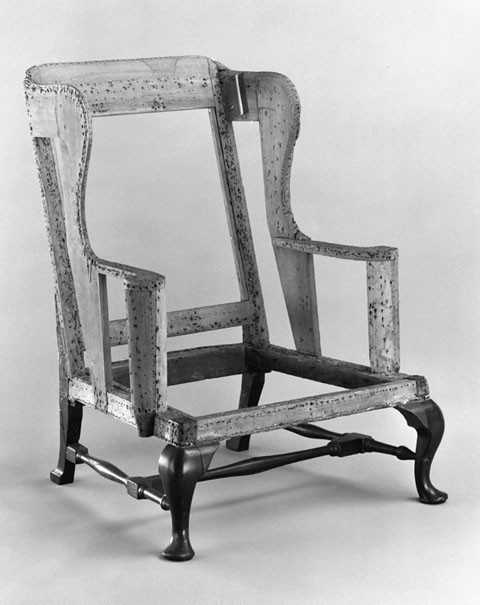

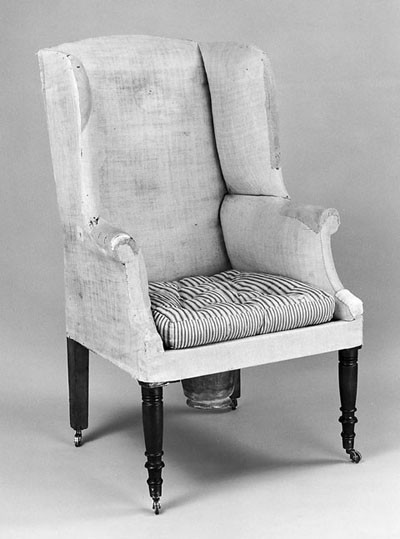

Easy chair attributed to the Anthony Hay shop, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1750–1770. Mahogany with ash, tulip poplar, and yellow pine. H. 44 1/8", D. 28 1/2", W. 31 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of a rasp-shaped wing on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 4, showing clusters of nail holes related to the original webbing on the lower edge of the back and wing.

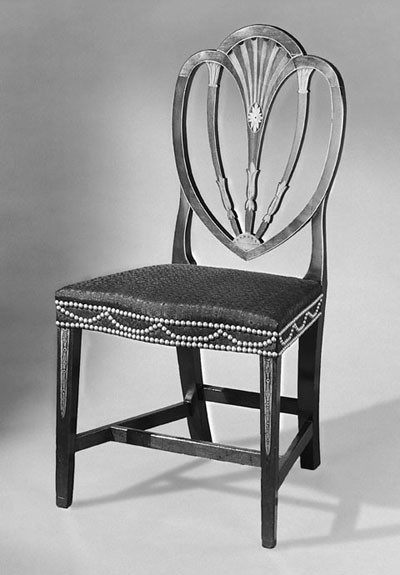

Side chair, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1815. Mahogany with ash and yellow pine.

H. 36 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of an upholstery peak on the side chair illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, L. Graves and F. C. Howlett.)

Armchair, probably Norfolk, Virginia, ca. 1790. Mahogany with ash. H. 38 3/4", W. 20 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of shadow marks indicating early or original upholstery profiles on the chair illustrated in fig. 8.

Easy chair, England, 1750–1760. Mahogany with beech and deal; remnants of original upholstery. H. 47", W. 32 3/4", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of an original edge roll on the wing of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 10.

Armchair attributed to Edmund Dickinson, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1775. Cherry; oak slipseat. H. 38 1/4", W. 26 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the slipseat from the armchair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.) The seat has its original curled hair and grass stuffing.

Detail of a leather fragment trapped beneath a forged nail on the seat frame of the chair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, L. Graves.)

Side chair, New England, 1790–1800. Mahogany with cherry and yellow pine; original upholstery foundation with remnants of haircloth cover. H. 40 3/8", W. 20 3/4", D. 18 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of textile imprints on the seat rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of modern brass nails used to point out the original nail pattern on the chair illustrated in fig. 8.

Masonic master’s chair signed by Benjamin Bucktrout, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1769–1775. Mahogany with walnut; original black-grained leather upholstery with brass nail trim. H. 65 1/2", W. 31 1/4", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Settee attributed to the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1771–1776. Cherry with tulip poplar and white oak. H. 36 1/2", W. 73", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Smoking chairs, Southampton County, Virginia, ca. 1775. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 32 1/4", W. 2 3/4", D. 25". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

The Grymes Children attributed to John Hesselius, Brandon, Middlesex County, Virginia, ca. 1750. Oil on canvas. 56" x 66 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society.)

Easy chair, piedmont region of Virginia, ca. 1790. Black walnut with yellow pine; original leather upholstery. H. 44 1/4", W. 28 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Armchair, probably Albemarle County, Virginia, ca. 1800. Cherry; original black leather upholstery. H. 34 7/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the black-grained leather and a stitched seam on the chair illustrated in fig. 18.

Preconservation view of the bottom of the chair illustrated in fig. 18. (Photo, L. Graves.)

Preconservation detail of the chair illustrated in fig. 18, showing the seat with upholstery peaks visible beneath leather.

X-radiograph of an armrest on the chair illustrated in fig. 18, showing undisturbed original nails. (Courtesy, Robert Berry, Fabrication Division, Nondestructive Evaluation Section, NASA—Langley Research Center.)

X-radiograph taken above the front seat rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 18, showing one strip of webbing, webbing nails, and the front edge roll. (Courtesy, Robert Berry, Fabrication Division, Nondestructive Evaluation Section, NASA—Langley Research Center.)

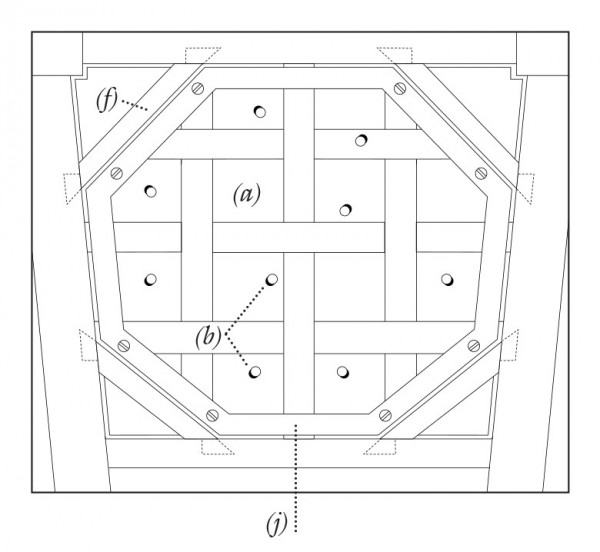

Auxiliary support for the seat of the chair illustrated in fig. 18: (a) 1/4" acrylic support plate beneath the original upholstery, (b) ventilation holes in acrylic support plate, (c) bolt and T-nut, (d) diagonal brace, (e) 4-ply laminated acid-free ragboard. (Drawing, L. Graves; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Detail of the corner bracket associated with the auxiliary support for the chair illustrated in fig. 18: (a) 1/4" acrylic support plate beneath the original upholstery, (b) ventilation hole in acrylic support plate, (c) bolt and T-nut, (d) 24-gauge copper Z-shaped bracket, (e) copper rivet, (f) diagonal brace, (g) triangular-shaped 1/8" acrylic support, (h) self-adhesive moleskin, (i) silk Crepeline fabric, (j) 4-ply laminated acid-free ragboard. (Drawing, L. Graves; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Detail of the underside of the chair illustrated in fig. 18, showing the new auxiliary support. (Photo, L. Graves.)

Easy chair, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1820. Walnut and maple with white pine, yellow pine, and tulip poplar; original upholstery. H. 45 3/4", W. 30 1/4", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

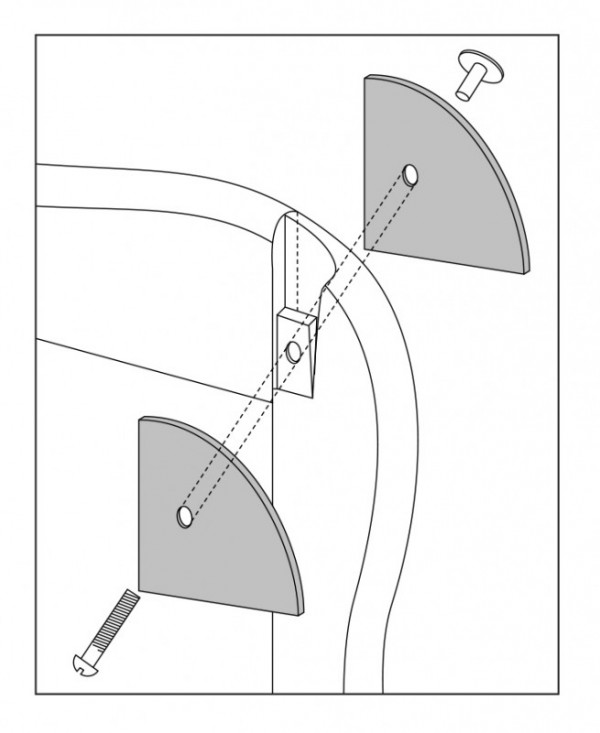

Design for plates used to secure and realign the damaged wing joint of the chair illustrated in fig. 32. (Drawing, L. Graves; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Preconservation detail of exposed Spanish moss stuffing from the chair illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, L. Graves.)

Postconservation view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 32, showing the stabilized original upholstery.

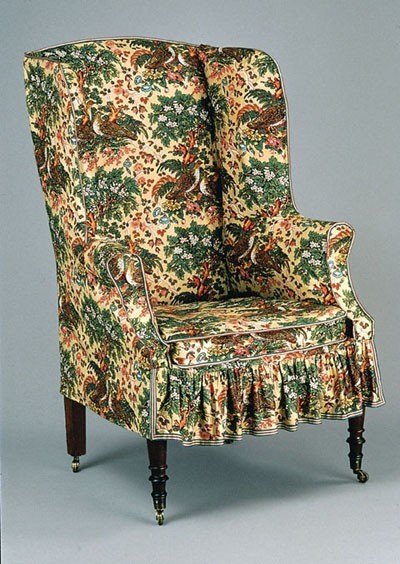

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1759. Walnut with white pine and maple; roller-printed chintz slipcover, ca. 1840. Clement Vincent or George Bright, chairmaker. Samuel Grant, upholsterer. H. 46 1/8", W. 33 7/8", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. A gift of the heirs of Elizabeth Cheever Wheeler. Photograph by David Bohl.)

Postconservation view of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 32, showing the new slipcover modeled after the example illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Side chair, probably Norfolk, Virginia, 1790–1810. Walnut and holly inlay with yellow pine. H. 34 1/2", W. 18 3/8", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail showing evidence of the original brass nail trim on the front seat rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, L. Graves and F. C. Howlett.)

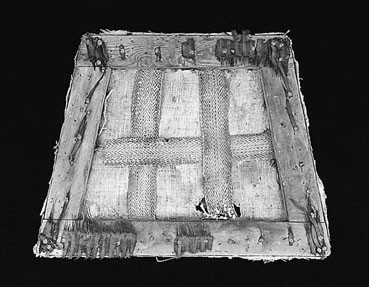

Slipseat frame, Virginia or Britain, ca. 1755. Beech; remnants of original linen and striped, black haircloth. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Sofa labeled by Chester Sully, Norfolk, Virginia, 1811. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and ash. H. 37 7/8", W. 72 5/8", D. 23". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Components of the nonintrusive upholstery system devised for the side chair illustrated in fig. 38: (a) front seat rail, (b) 24-gauge copper face plate, (c) black cotton fabric, (d) haircloth show textile, (e) brass nails, (f) removable shoe molding, (g) rear seat rail, (h) polyester batting, (i) Ethafoam, (j) 32-gauge copper foundation. (Drawing, L. Graves; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Postconservation view of the side chair illustrated in fig. 38.

Sofa, Winchester, Virginia, 1790–1800. Black walnut and maple inlay with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 37", W. 89", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Sofa, Winchester, Virginia, 1790–1800. Black walnut and maple inlay with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 37", W. 86 1/2", D. 27 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of an inlaid leg on the sofa illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the arm assembly and seat rails of the sofa illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the sofa illustrated in fig. 45, with modern nails pointing out original brass nail locations.

Detail of the sofa illustrated in fig. 44, with new upholstery and trim applied according to evidence found on the frame. (Photo, L. Graves and F. C. Howlett.)

Postconservation view of the sofa illustrated in fig. 44, with cushions fabricated according to a dimensional study of the frame. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

By the mid-1760S, Richmond County, Virginia, planter John Tayloe II (1721–1779) had completed his elegant Georgian house, Mt. Airy. His furnishings included pier tables designed by architect William Buckland, whose shop produced much of the interior woodwork in Mt. Airy, and other furniture that he and his wife, Rebecca, had purchased or inherited. The easy chair illustrated in figure 1 may have been purchased by Tayloe during the late 1740s or early 1750s, or it may have been a bequest or gift from his father, John Tayloe I (1687–1747), whose 1747 estate inventory listed “a doz Dammask Bottom’d Chairs & two Easy ditto.” It descended in the Tayloe family for several generations and oral tradition maintains that it came from Mt. Airy.[1]

Like many examples of southern upholstered furniture, the Tayloe chair has suffered from the passage of time. During the mid-nineteenth century, the cabriole legs were shortened and fitted with metal casters. Likewise, a late alteration of the armrest members resulted in an ungainly rake to the arms. The accumulation of at least seven nailed-on show textiles also reflects significant changes in the appearance and the function of the chair over time. The uppermost fabric is a Colonial Williamsburg reproduction striped cotton. Beneath it are several nineteenth-century cotton prints, an eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century red wool worsted, and the original blue and cream silk damask and foundation upholstery. A chair with a similarly elegant damask textile is depicted in Matthew Pratt’s portrait of Mary Jemima Balfour of Hampton, Virginia (fig. 2), which is about thirty years later than the Tayloe chair.[2]

Although the Tayloe chair could be restored to its original appearance, such an undertaking would compromise a wealth of historic information. Each textile layer speaks to the changing tastes of succeeding generations of owners, and each alteration of the frame tells of the changing function and status of the chair over its 250-year existence. Because so few objects survive with such comprehensive upholstery evidence, the preservation of the chair in its current state takes precedence over restoration to its original appearance.

The Task of the Upholstery Conservator

Apart from the historic information it reveals, the Tayloe easy chair illustrates an indisputable fact—upholstery fares poorly over time. Textiles become brittle and faded, stuffing materials compress and crumble, and webbing stretches and breaks. Whether concerned with function or fashion, owners typically discarded, replaced, or covered up old upholstery when it began to sag or look outmoded. Usually nothing is left but the upholstery frame, which has been re-stuffed and covered with textiles reflecting more recent tastes. The conservator is often faced with two difficult tasks: preserving extremely fragile upholstery materials when they survive and reconstructing the appearance of the original upholstery when little is left but the bare frame.

In preserving old or original upholstery materials, the conservator is chiefly concerned about arresting deterioration. Many stabilization techniques are drawn from the work of conservators of flat textiles and costumes, though the three-dimensional structure of upholstery often limits the treatment options. The fixed juxtaposition of layers of materials, each having its own properties and each serving a specific purpose, sometimes results in harmful chemical interactions that are difficult to mitigate. Upholstery materials are also constantly under tension, even when not in use, which contributes to their deterioration over time. Dust, dirt, or stains can sometimes be removed, but typically work must be carried out in situ to avoid damaging the upholstery structure. Loose or ripped textiles can be stitched in place using unobtrusive thread, and disintegrating materials may be encapsulated in a stitched-on sheer material. Auxiliary supports are also employed for upholstery that can no longer carry its own weight. Little or nothing can be done about fading, fraying, or extreme sagging. Aesthetic concerns are secondary in the conservation of original upholstery materials, which are valued chiefly as documents of period materials and techniques.

Reconstructing the appearance of historic upholstery from evidence available on a bare seating frame is a very different task. The closest parallel to such efforts is the work of the forensic anthropologist, who attempts to reconstruct the physical features, habits, and health of long-deceased individuals by carefully studying their skeletal remains. In the same way, the upholstery conservator investigates the “skeletal remains” of chairs and sofas, determining from the available evidence information about their history, appearance, and function. The conservator’s work is typically complicated by the overlapping evidence of numerous upholstery schemes. Distinguishing individual schemes can be time consuming and in some instances virtually impossible. To produce a credible reconstruction of historic upholstery, one needs to develop a thorough understanding of the techniques, materials, and tastes of the period and place of production. Information might be gathered from various sources. Pictorial references appear in cabinetmakers’ guides, paintings, and prints, and documentary evidence exists in inventories, advertisements, letters, and literature of the era. More tangible information comes from the rare examples of upholstered furniture retaining original materials; however, the most important source of information in any conservation treatment is the object itself. As bare as an upholstery frame may seem, significant evidence of the original upholstery remains on its surface.

Once the frame has been thoroughly examined and a plan formulated for reupholstery, the conservator then reapplies materials in a manner that maintains the integrity of the bare frame and preserves any evidence of the history of upholstery schemes. The goal of treatment may be to re-create the appearance of one of the early schemes, but this task must be accomplished using unconventional, nonintrusive techniques. Traditional nailing methods are avoided because of the damage they cause, and the upholstery conservator typically engineers a system that clads the frame using auxiliary frame inserts, straps, and custom-formed fittings.

Reading the Evidence

The most important part of any historic upholstery treatment is the examination of the object, since the information derived from that study should guide all decisions about the preservation of early materials and/or the plan for reupholstery. To interpret such evidence correctly, a basic knowledge of traditional upholstery techniques and materials is imperative (fig. 3). Important factors to consider during an examination include the structure and shaping of the frame, evidence left by original nails or other hardware, shadow marks and other clues to the original upholstery profile, fibers or threads relating to the original show material, and evidence of the original decorative trim.

The form, construction, shaping, and tool marks on upholstery frames can reveal a great deal about the original upholstery. For instance, the edge shaping of the board forming the wing of an easy chair provides clues to the original upholstery treatment (fig. 4). If the inner edge of the board was originally rounded with a wood rasp or other hand tool, then the wing may have had tapered, rounded upholstery with, perhaps, a single line of trim outlining the outermost edge (fig. 5). Alternatively, a square-edged board in conjunction with other evidence may indicate that the wing had boxed-edge upholstery (the wing is outlined by a thin panel of show fabric flanked on either side by a line of trim to give it a fuller appearance).

Similarly, a close examination of chair legs can often provide information about the height of the seat upholstery. An eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century British or American chair leg, for example, may retain an original upholstery peak—a triangular projection extending from the top of a front leg post (figs. 6, 7). Such a feature provides practical information about the height of the upholstery on the outer corners of the seat, since upholsterers traditionally pulled the top linen and show fabric tightly over the lightly padded peak.

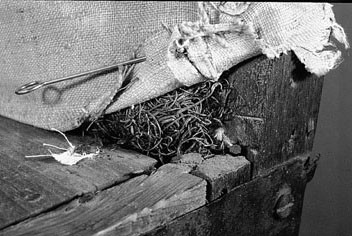

The application of upholstery is a step-by-step process, and a thorough examination for nail evidence consists of retracing each step in that process. When studying an eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century chair, one first looks for evidence of the original webbing (the support material) in the form of clustered nail holes of relatively large dimension, typically spaced along the upper surfaces of seat rails and the inner edges of frame members (see fig. 5). Evidence will then be sought for each additional nailed layer. The foundation linen, edge rolls, top linen, show fabric, and decorative trim all leave characteristic nail patterns on a chair frame, and their presence or absence, concentration, and location provide useful information about the original upholstery.

By contrast, evidence of the original loft or profile of the upholstery is often minimal. On side chairs that have not been heavily restored or refinished, differences in the color and gloss of the wood just above the back stile/seat rail joints may provide clues. Because the upholstery protected the wood from light and air-borne pollutants, the height and curvature of such “shadows” may indicate whether the seat was lightly or heavily stuffed (figs. 8, 9). Likewise, traces of early finishes or other surface treatments may denote original upholstery boundaries, which were often extended during later upholstery schemes.

The presence of edge rolls on seats, backs, and wings also influenced upholstery profiles (figs. 10, 11). Although the exact diameter of a missing edge roll is difficult to determine, nail evidence can be used to extrapolate dimensions. Closely spaced nailing, for example, suggests a tightly stitched roll and a slim upholstery profile, whereas wider-spaced nailing suggests a looser roll and a rounder profile. A more exact determination is possible if upholstery peaks are present. Edge rolls traditionally abutted upholstery peaks, so the diameter of a roll was usually equal to the height of the peak above the seat rail.

The stuffing materials used in seventeenth-century Virginia upholstered furniture are unknown because no examples survive. It is logical to assume, however, that the turkeywork and leather chairs listed in early inventories were stuffed with grass or straw, much like their British and New England counterparts. Curled horsehair became the most common filler during the eighteenth century, and its use in Virginia is documented both in extant upholstery and in documents. Cheaper materials such as grass, tow (flax fibers), and Spanish moss were also common, even in the most expensive Virginia furniture (figs. 12, 13).

Although surviving examples suggest that there is little correlation between the type of stuffing material and the general amount of loft in an early upholstery scheme, the location of the surviving material may still be revealing. Fibers of curled horsehair trapped beneath early nails on the curved arm support of a sofa, for example, might suggest the presence of padding on an area typically covered only by textiles. Likewise, imprints of a straw edge roll on a framing member may indicate the roll’s termination points and rough dimensions, extremely helpful information for determining an early upholstery profile.[3]

The discovery of fibers, textile fragments, or leather scraps related to the original show material greatly influences decisions on the final appearance of any upholstery reinterpretation (fig. 14). Though large scraps are ideal sources of information, the conservator must often examine a frame under magnification. With persistence and luck, fibers may be discovered beneath the heads of original nails still embedded in the frame. A single fiber can yield valuable information about the color and type of textile (silk, cotton, wool, linen), and bits of thread can provide clues about the texture and weight of a fabric. Similarly, woven fragments can provide insight into the weave or pattern of the original material.[4]

Even if no fibers are found, there may be clues to the original material on the upholstery frame. The weave structure of textiles such as silk, haircloth, or lightweight wool may have been imprinted on the wood by the nail heads that applied the show material or decorative trim (figs. 15, 16). Conversely, the lack of a textile imprint may signify a heavier material, such as needlepoint or leather, or the presence of a thick tape.

Three types of decorative trim were prevalent on eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American upholstered furniture: brass nails, gimp or tape (known as “lace” during the eighteenth century), and cord. Of the three, only brass nails leave evidence that is easily distinguishable on a bare upholstery frame (fig. 17). This evidence consists of rows of small, regularly spaced nail holes, usually outlining the frame but, during the federal period, occasionally appearing in the form of decorative swags, S curves, or other patterns on the faces of seat rails. Ring-shaped imprints left by the nail heads are often visible around the holes. The holes themselves may be either square (evidence of seventeenth-, eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century cast brass nails) or round (evidence of more recent nails with wire shanks). If no evidence of brass nails is present, then it is likely that the upholsterer used gimp, cord, or a combination of the two. Gimp was usually applied with an adhesive or small brads, whereas cord was stitched into the upholstery. In both cases, the evidence remaining on the frame is usually minimal or nonexistent. Here the conservator must look to historic prototypes rather than rely on physical evidence alone.

Although examining upholstery frames is a straightforward, systematic process, evidence of the original upholstery is often fragmentary or obscured. Frames were often upholstered several times, and distinguishing early schemes can be difficult. Unusual deviations from standard period upholstery practices may also be difficult to interpret. Fortunately, however, upholstery was a relatively conservative trade requiring a limited number of techniques and materials. The conservator can thus often determine the original upholstery process from the physical evidence found on an upholstery frame. Where physical evidence is incomplete or difficult to understand, supplementary information gleaned from documents, paintings, and related upholstered forms can shed light on the object’s original upholstery scheme.

Five Virginia seating forms illustrate the principles discussed above. A Masonic master’s chair made by Williamsburg cabinetmaker Benjamin Bucktrout (fig. 18) and a Richmond easy chair (fig. 32) retain significant portions of their original upholstery. Accordingly, their treatment involved research into their historic context and examination and preservation of their textile components. By contrast, the Norfolk side chair illustrated in figure 38 and the Winchester sofas illustrated in figures 44 and 45 were almost devoid of original upholstery materials. The replication of period upholstery for the example shown in figure 44 thus drew upon evidence on their frames and information from pictorial and documentary sources.

Bucktrout Masonic Master’s Chair

Bucktrout’s imposing ceremonial chair may have been commissioned for Peyton Randolph, who served as provincial grand master of Virginia Freemasonry during the early 1770s and as president of the first Continental Congress in 1774. The chair’s seat consists of black-grained leather trimmed with brass nails above elaborate, relief-carved rails. Although no other brass-nailed leather upholstery from Williamsburg survives, Bucktrout obviously used the technique for other work. In October 1772, he sold Robert Carter of Nomini Hall eight “Mahogy Chares Stufed over the Rails with Brass nails.”[5]

In Virginia, leather was a common covering for chairs throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A 1698 Accomack County will lists “1 Virginia Chooch the bottom Leather,” and a 1718 York County estate inventory lists “1/2 doz of Rushia leather Chairs.” In 1745, John Walker of Middlesex County owned “12 Mahogany Chairs leather Bottoms” and “2 Elbow do.” Williamsburg cabinetmaker Peter Scott used leather seats for a settee and several side chairs that may have been among the standing furniture in the Governor’s Palace during the early 1770s (fig. 19). An armchair attributed to Edmund Dickinson, master of the Anthony Hay shop during the mid-1770s, retains fragments of its original leather upholstery (figs. 12, 14), as does a seat frame fragment excavated from the Hay shop site. Furniture makers elsewhere in southeastern Virginia also employed leather, as confirmed by the original slipseats on a pair of smoking chairs from Southampton County (fig. 20). Leather’s superior durability may partially account for its prevalence in Virginia chairs retaining original upholstery; nonetheless, evidence suggests that it remained a popular material for chair seats throughout the eighteenth century.[6]

A possible explanation for the frequent use of leather in the Williamsburg vicinity was its availability. Alexander Craig, a Williamsburg tanner and harnessmaker, sold leather and leather-related products to a variety of plantation owners, tradesmen, and cabinetmakers throughout the Tidewater region. In 1751, he advertised the “Best Sole and Neats Leather, wax’d Calve Skins and Hides, suitable for Coaches, Chaises, Couches, Portmantuas and Chair Bottoms, in any Quantity.” Although saddlemaking and harnessmaking accounted for most of his labor, Craig also provided finish work for carriages and riding chairs. On May 8, 1761, Craig charged Colonel Robert Burwell for “400 Brass nails and Lining a [riding] Chair, the Cushion and wings wt Leather Lace,” and on May 2, 1762, he billed Colonel Philip Lee for “100 Brass nails and covering a step of a Charriot.” No upholstered riding chairs from Virginia survive, but the fanciful child’s phaeton depicted in a mid-eighteenth-century portrait of the Grymes children of Brandon in Middlesex County ties the practice of coach lining to the upholstery of seating furniture (fig. 21). Similar links are also evident in Craig’s account book. In addition to selling “black grain,” “calfskin,” and other leather products to Williamsburg cabinetmaker Anthony Hay, Fredericksburg cabinetmaker James Allen, and Hampton cabinetmaker John Selden, Craig made mattresses, bolsters, and cushions for furniture. Over a five-year period during the mid-1750s, Craig recorded thirteen transactions regarding such work for the couches and easy chairs of Anthony Hay.[7]

The proximity of leatherworkers like Craig was not the sole reason for the material’s popularity in Virginia upholstery. The fact that Virginians continued to cover their chairs with leather during the late eighteenth century, as demonstrated by a piedmont easy chair (fig. 22) and an Albemarle County armchair attributed to Jefferson’s joinery at Monticello (fig. 23), suggests an ingrained stylistic impulse. Like many of their British counterparts, Virginians frequently used the phrase “neat and plain” to describe their predilection for sparsely ornamented, well-made case furniture and other goods. The phrase also applied to rich, durable, monochromatic leather upholstery. On the Bucktrout chair, the “black-grained” leather seat suggests simplicity and permanence, and the line of end-grain leather that defines and reinforces the stitched seams (fig. 24) represents the work of a skilled upholsterer or leatherworker.

The seat frame and upholstery foundation of the Bucktrout chair are characteristic of other British-influenced chairs. Like many British and American chairs with over-the-rail upholstery, the Bucktrout example has diagonal corner braces set into notches in the rails to help the frame resist the force of tightly stretched textiles (fig. 25). The outlines of the upholstery peaks at the top of the front legs are clearly visible beneath the leather (fig. 26).

Although the height of the peaks in relation to the overall rounded loft of the seat led to speculation that the chair received supplemental stuffing in the nineteenth century, X-radiography and careful “exploratory surgery” proved that the seat profile was essentially original (figs. 27, 28).

An attempt to shore up the sagging seat during the early twentieth century resulted in damaged materials and a somewhat elevated profile. This new support consisted of two pine boards inserted above the diagonal corner braces (fig. 25). Regrettably, the leather was slit along the rear edge to relieve the tension and permit the rear corner braces to be pushed up and out of their notches. This provided sufficient clearance to slide the boards into place and to return the corner braces to their proper positions. Once in place, the new boards elevated the upholstery by approximately three-fourths of an inch. The raised profile and unsightly slit at the rear of the seat convinced us to remove the pine boards in order to repair the damage and develop a better support system for the seat.

Removal of the boards permitted a thorough inspection of the foundation upholstery. To support the deep, wide seat, the upholsterer used only six strips of herringbone webbing (fig. 28). After attaching them to the seat rails (three front-to-back and three side-to-side), he nailed an oversized piece of very coarse foundation linen to the rails above the webbing, allowing it to overhang about four to five inches on each side. Then he created soft, round edge rolls by doubling back the edges of the linen, stuffing it loosely with curled horsehair, and stitching it along the top, inner edges of the rails. After filling the cavity created by the edge rolls with curled horsehair, he covered the seat with a piece of finer-textured linen. Apparently the upholsterer chose to create more loft before nailing on the leather since he added a skimmer of Spanish moss between it and the top linen. Over time, the acidic moss caused holes to form in the top linen.

Before creating a new support, we stabilized the old materials. We gently steamed the webbing and foundation linen to relax the sharp folds caused by the forced installation of the pine boards. Then we enclosed the torn, frayed ends of the webbing and linen with stitched-on Stabiltex fabric. Since the original support materials no longer contained all of the stuffing, we stitched Stabiltex over both sides of the damaged areas of the top linen and encapsulated the curled hair in a case of the same sheer material. At this point, we repositioned the materials in their original locations in preparation for a new auxiliary support.

Several criteria determined the design for the new support. We needed to support all the materials in an approximation of the original loft without intruding on the original frame or upholstery. The system also had to protect the fragile upholstery and be made of materials that would not contribute to further deterioration. Finally, we wanted the system to be removable and not conceal the original materials when in place. The system shown in figures 29–31 satisfied all these criteria. It was easily installed by sliding a corner bracket into place above each of the diagonal braces, then screwing the transparent support plate to the brackets. The support plate is a one-fourth-inch acrylic sheet surmounted by a built-up stretcher of acid-free rag-board spanned by taut silk Crepeline. The silk bears against the original upholstery and creates a one-fourth-inch air space between the original webbing and the acrylic sheet.

With the support in place, we turned our attention to the treatment of the leather. The portion of leather originally attached to the rear seat rail was missing, having been removed when the seat was slashed along the rear edge. To compensate for the loss, we first attached a tab of acid-free cotton fabric to the underside of the slit edge using a polyvinyl acetate adhesive. We then cut a new piece of matching leather, laid it above the tab, and secured it with the same adhesive. To attach the new leather to the back rail, we glued a lightweight aluminum angle to the back edge of the leather with hot-melt adhesive (ethylene vinyl acetate) and riveted a row of closely spaced brass nails to the leather/aluminum strip to simulate the lost decorative trim. We left full-length shanks on three of the nails and tapped them into original holes (plugged) in the rear rail. Having conserved the seat, we completed the treatment of the leather by consolidating areas of minor flaking with a solution of ethulose in water and by patching a one-inch-diameter hole near the center of the seat with a paper fill colored to match the aged leather. Although the completed treatment provides support and inhibits further deterioration, we minimized cosmetic enhancements to maintain the integrity of the leather.

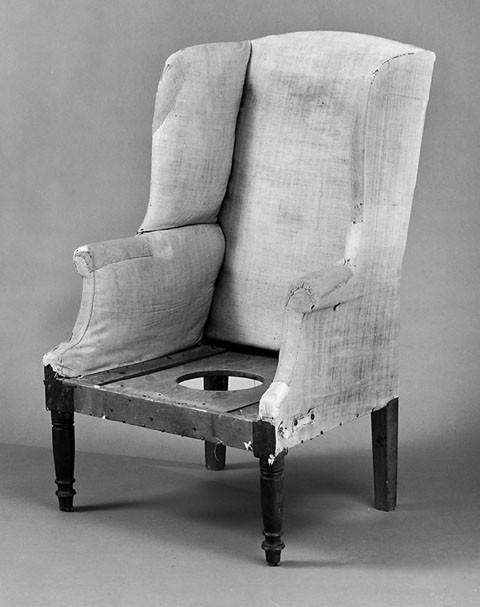

Richmond Easy Chair

The early nineteenth-century easy chair illustrated in figure 32 descended in the Gwathmey family of Burlington, in King William County, Virginia. The chair exhibits features typical of Richmond and Petersburg work, most notably the double ring and cove turning of the legs. As was often the case with easy chairs, this example doubled as a close stool. Resting within the rails is a three-board yellow pine seat with a hole cut for a chamber pot. Although the chair suffered losses to the feet and damage to the joints of the wings, it retained nearly all of its under-upholstery and an early, down-filled, ticking-covered cushion.

The chair had no evidence of a nailed-on show textile, which suggests that it originally had a slipcover. A few features of the upholstery also support that conclusion. Top linen encases both the inner and outer surfaces of the wings and back of the chair, giving it a finished appearance. Upholsterers generally applied top linen only to the padded surfaces of chairs intended to receive nailed-on show textiles. In addition, deep clefts in the upholstery at the juncture of the wings and back appear calculated to serve as tuck points for a loosely fitted slipcover.

Slipcovers became common in Virginia during the latter half of the eighteenth century. Most often, they were used to protect expensive or delicate nailed-on fabrics. In 1771, Robert Beverley of Blandfield in Essex County, Virginia, ordered “12 neat plain mahogany Chairs, with yellow worstit Stuff Damask Bottoms . . . & spare loose Cases of yellow & white Check to tie over them.” Later references and chairs similar to the Gwathmey example suggest a trend toward using slipcovers as the primary show material. An 1807 Alexandria County suit mentioned the sale of property including two “settees with double covers . . . one large Settee with double Covers . . . [and] fourteen mahogany Chairs, with double slips.” Similarly, the 1822 will of Peter Copeland of Richmond listed an “Easy Chair with 4 Covers.” The possession of multiple covers for chairs and sofas suggests their year-round usage, either to vary the covers seasonally or to substitute covers during cleaning.[8]

In conjunction with the curators of furniture and textiles, we decided to incorporate an appropriate slipcover into the treatment plan for the Gwathmey easy chair. The conservation of the frame and surviving upholstery preceded the fabrication of the cover. We lengthened the shortened feet and added casters, using the corresponding details on a virtually identical easy chair as our guide. The loose, fragmented joinery of one of the wings presented a more difficult problem—stabilizing the joint without damaging the adjacent upholstery materials. To realign and strengthen the joint, we sandwiched the adjoining wing members between two small plates of textile-covered copper (fig. 33). We only had to remove a few stitches in the linen cover to position the plates, then we drew them together using an empty three-sixteenth-inch hole formerly occupied by a wooden pin.

The original profile of the easy chair’s upholstery had lost definition, in part because of the stretched, frayed, and torn linen. The stuffing had also sagged, despite the upholsterer’s attempt to hold it in place with waxed cord (run through small holes in the framing members and secured with nails). Some of the sagging resulted from deterioration of the unprocessed Spanish moss, or “Spanish Beard,” used to stuff the chair (fig. 34). The outer skin of the moss, normally removed during processing, had crumbled to a coarse powder and sifted down to the bottom linen. Although little could be done to correct this problem, we improved the profile by manipulating the stuffing with a long upholstery needle (regulator). Using two-ply linen thread, we then stitched patches of Stabiltex to all areas of worn-through or frayed linen (fig. 35). The final treatment of the under-upholstery involved replicating the missing linen on the front seat rail. Rather than nailing it in place, we glued it to a U-shaped copper plate and friction-fit it to the rail.[9]

No fragment of the original slipcover textile survived, and no Virginia covers from the early nineteenth century are known. As a result, we used a circa 1840 roller-printed, chintz slipcover on an eighteenth-century Boston chair (fig. 36) as the prototype for a new one (fig. 37).[10]

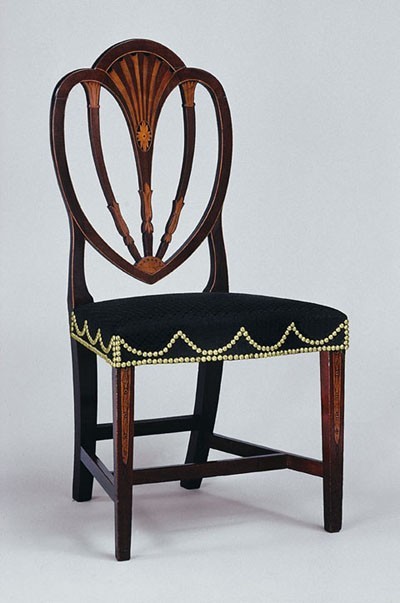

Norfolk Side Chair

In 1800, Norfolk had eight thousand inhabitants and was the eighth largest city in the United States. The city supported a growing community of cabinetmakers, chairmakers, and upholsterers who provided furniture for consumers in Norfolk and the surrounding towns and plantations of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. Urban British styles and construction practices had a profound influence on Norfolk furniture made before and immediately after the Revolution. Although British influences persisted, tradesmen from New England and New York introduced a variety of northern furniture styles during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The side chair illustrated in figure 38 may be the product of a cabinetmaker trained in a northern city. No exact prototype for this chair is known; however, examples with heart-shaped backs were made in several northern cities. Elements distinctly associated with Norfolk include the blade-shaped panels on the front legs, the bellflowers with concave outer petals, and the incised shading cuts filled with a black resinous material.[11]

The chair came into the Colonial Williamsburg collection with twentieth-century upholstery that in many respects represented a plausible replication of late eighteenth-century taste and techniques. The loft of the seat was relatively low, the show textile was a medallion-patterned black horsehair, and the decorative trim consisted of a double row of brass nails sandwiching a typical, if somewhat flattened, swag pattern. Upon lifting the nails to expose a portion of the seat rail, clear evidence of square-shanked, cast brass nail trim indicated that the chair had received three over-the-rail treatments early in its history. One consisted of pronounced swags above a single line of brass nails running along the bottom edges of the rails (no upper boundary line of nails was present) (fig. 39). Another consisted of two parallel lines—about two inches apart—of close-set brass nails. The uppermost line of nails in the latter treatment intersected the swags of the first, indicating that the two nail patterns were produced at different times. A third nail pattern differed only slightly from the second, with the upper line of nails sloping downward toward the rear of the side rails. This treatment appeared incomplete and may have been aborted by the upholsterer because of the sloping nail lines.

The twentieth-century upholsterer responsible for the most recent scheme attempted to recreate a nail pattern based on the early evidence. Unfortunately, his design combined two of the early schemes, resulting in a hybrid, flattened swag-pattern between two parallel rows of nails. For our interpretation of the upholstery, we followed the outline of the early swags, which were accompanied by only a single row of nails at the bottom.

No evidence of the show material survived on the frame, so we consulted pictorial sources, documentary references, and other seating furniture to select an appropriate textile. Manufactured in the colonies by 1736 and esteemed for its durability and satinlike appearance, haircloth was one of the most common textiles used on late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Virginia chairs. The 1789 estate inventory of Gabriel Galt of Henrico County listed “11 Mahogany chairs hair bottoms.” Remnants of a black-striped haircloth survive on a slipseat frame found at Blandfield (fig. 40). This textile may resemble the “22 and 19 Inch narrow Satin Stripe Hair-Seating” mentioned in a 1790 advertisement by Baltimore cabinetmakers Bankson and Lawson. More importantly, an 1811 Norfolk sofa (fig. 41) with remnants of its original haircloth confirms the use of that material in the city and justifies its use on the side chair.[12]

In recent years, upholstery conservators have developed new methods of applying materials to bare frames to avoid the damage caused by traditional nailing techniques. The seat of the chair illustrated in figure 38 has the appearance of nailed-on upholstery, but it is completely nonintrusive. We accomplished this look by creating a “cap” consisting of several components selected for their ease of workmanship, their harmless effect, and their ability to contribute to the illusion of nailed-on upholstery (fig. 42). We used sheet copper for the foundation, because it conforms closely to the chair frame even when overlaid with other materials such as Ethafoam—a rigid polyethylene foam that is lightweight, inert, and easily shaped to simulate an upholstery profile. Since Ethafoam can be sculpted to the intended profile, show materials do not need to be stretched tightly over its surface to produce a taut appearance. If sat upon, however, Ethafoam does not fully recover its shape, so we limit its use to exhibition upholstery (functional seats are possible using minimally intrusive techinques, but their design is complicated by the need to compress the stuffing to attain the proper profile and create a comfortable seat). After sculpting the Ethafoam, we applied a layer of polyester batting to soften its appearance and to provide a slightly compressible surface for the application of the textile layers. Because of the open weave of modern haircloth, we first applied a black cotton fabric to prevent the white batting from showing. We lightly stretched the black lining over the surface, folded it over the edges of the copper plates, and glued it to the copper with hot-melt adhesive. We applied the haircloth in a similar manner, with the front corners cut and handstitched to give the appearance of a traditional cover. Finally, we applied the modern brass nails by inserting the wire shanks through holes in the copper plate, trimming the points, and peening over the projecting shanks to rivet them in place. The completed upholstery cap exists as a unit attached to the chair solely by a light friction fit, and we can safely remove it in a matter of seconds to study the chair frame (fig. 43).[13]

Two Winchester Sofas

After visiting with the Tidbald family of Winchester in 1799, Susanna Knox wrote: “They live in a large stone house, I was only in the drawing room—that was a very handsome one, elegantly furnished with mahogany—a settee covered with copperplate calico, red and white, the window curtains the same, with white muslin falls, drawn up in festoons, with large tassels as big as my two fists.” Situated on the Great Wagon Road at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, Winchester was one of the largest towns in the backcountry. It was also an important commercial center and a staging point for migration to the frontier. Like many other travelers from the east, Susanna Knox was impressed by the sophistication of the town and the furnishings and other material goods available there.[14]

Two late eighteenth-century Winchester sofas rival the finest examples from the East Coast. One of these sofas was recently reupholstered following an intensive study of its frame (fig. 44) and the frame of a nearly identical sofa (fig. 45). This side-by-side examination proved beneficial to the interpretation of missing elements on both examples and enabled us to confirm the authenticity of some unexpected features of the original upholstery on both objects.

The sofas are highly developed examples of early neoclassical seating furniture. Each has a serpentine back, scrolled and sculpted armrests that sweep upward and outward with graceful S curves, and square-tapered legs with inlaid stringing and incised bellflowers (fig. 46). The unconventional form of the bellflowers, which are inverted and have rounded lobes, is the most obvious detail associating them with backcountry production. Other features typical of Winchester work include the use of walnut rather than mahogany as the primary wood, the use of yellow pine and tulip poplar as secondary woods, and the presence of a molded bead along the lower edges of the front and side seat rails. The sofas are part of a group of furniture including a wine cooler, several sideboards, and a pair of card tables, all of which appear to be from the same Winchester shop.[15]

Although varying slightly in form (the example shown in fig. 45 has more pronounced curves on its arms and back), the sofas share many structural features. Both have ribbed structures in the arm assemblies that help define the complex shapes of the arms (fig. 47), inner front legs that are secured with sliding dovetail saddle joints, and evidence of original casters. The sofas also have two curved medial stretchers spanning the front and rear seat rails and nearly identical supports and attachment points for their removable backs. Because their structures are so similar, the unaltered crest rail of the sofa illustrated in figure 45 proved helpful in redesigning the lost upper edge of the other example (fig. 44), which was apparently planed down prior to a twentieth-century reupholstery. By studying the form of the unaltered crest and by measuring the planed-down depths of original brass nail holes found on the altered crest (unaltered areas had nail depths averaging one-half of an inch, whereas those in planed areas were as shallow as one-sixteenth of an inch), we were able to reconstruct an accurate profile that raised the central portion of the altered crest rail as much as three-eights of an inch in height.

Other shared features of the frames gave insight into the original fabrication and appearance of the upholstery. To augment the nailing surface for the seat webbing, the upholsterer nailed wooden strips to the inner surfaces of the side rails (see fig. 47). His practice of nailing the webbing into shallow dadoes on the upper surfaces of the rails (perpendicular to their length) suggested that he intended to maintain a low upholstery profile on the seats. Molded beads running along the bottom edges of the front and side rails indicate that the lower rail faces were exposed. This seat configuration, referred to as “half over-the-rail upholstery,” is rare on sofas of this form. Although obscured by nail damage, remnants of an early finish on the rails of the sofa illustrated in figure 45 provided further evidence that both pieces had half over-the-rail upholstery. (The rails of the other sofa were abraded and veneered during the twentieth century, thus no finish remnants remained.)

The sofas have only a few remnants of original upholstery material. The one shown in figure 44 retains strips of webbing nailed across the ribs of the arm assemblies, and the other sofa (fig. 45) has its original back webbing and foundation linen. Fibers of deer or cow hair adhering to the linen indicate the nature of the original stuffing material. The webbing arrangement and size and spacing of the nails on the sofas is remarkably similar, indicating that both sofas were upholstered by the same hand.[16]

Although no fibers relating to the original show materials of the sofas survived, both pieces have evidence of their earliest decorative trim. On both sofas, square-shaped holes, broken shanks, and head imprints from the original brass nails revealed the same pattern. The nail heads were one-half inch in diameter and spaced an inch and a half on centers. Unlike other neoclassical sofas with similar nailing, the trim on the Winchester examples outlined the inside corners formed by the juncture of the arms and backs and the seat and bottom edge of the lower back rail (fig. 48), in addition to the usual structural components—arm supports, armrests, seat rails, and crest rails. If such features had been discovered on only one sofa, they may have been dismissed as implausible aberrations. As a general rule, upholsterers did not apply expensive brass nails in locations typically covered by cushions or mattresses. Because both Winchester sofas had this unconventional treatment, the reconstructed upholstery features the same profligate use of brass nails.

The trim evidence suggested that the original upholstery on both sofas could have been leather. The brass nails left very few circular imprints on the frame, as they would have if the original covers had been a thin, woven textile. Although a woven tape or gimp beneath the nails could also have prevented the heads from scarring the frame, the very close proximity of the nail holes to the edges of the wooden elements also suggested that the sofas had leather covers. Since leather adds thickness to the surfaces of an upholstery frame, the brass nail trim runs closer to the edges of the frame and occasionally runs off the wood altogether in order to keep the nail trim flush with the corners produced by adjoining leather edges. Another clue in support of leather is the presence of knife cuts, possibly from a tool used to trim the edges, on the left seat rail of the sofa shown in figure 45. Since there were no knife cuts on the other sofa and neither example had conclusive proof that leather was the original show material, the sofa illustrated in figure 44 was reupholstered in a green moreen using a nonintrusive system.

Reupholstery of a sofa frame invariably results in questions regarding the presence or absence of a loose mattress and cushions. One cannot generalize about period upholstery since physical and documentary evidence supports various approaches to mattresses and cushions; however, dimensional studies often provide indications of their presence or absence. For the sofa illustrated in figure 44, a dimensional study provided sound indications of loose back cushions and a seat mattress. Evidence for a mattress grew from a determination of the intended height of the applied seat upholstery. The height from the floor to the upper edge of the seat rails, including an allowance of 2" for original casters, was 16 1/2". We also found nail evidence for an original edge roll approximately 1" in diameter; thus, the height from the floor to the upper surface of the seat upholstery was approximately 17 1/2", lower than most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sofa seats. Since the top edges of the outer legs are 20 1/4" high, it is logical to assume that the sofa had a 3"-thick mattress. Similarly, loose back cushions are implied by the 25" front-to-back dimension of the seat, as well as by evidence of thinly applied back upholstery. The loose cushions were probably 3 inches thick to coordinate with the seat mattress and to comfortably reduce the depth of the seat.

Most of the features of the replicated upholstery on this sofa were drawn directly from evidence found during the study of the two Winchester examples. As in the case of the show material, however, there were some gaps regarding the original appearance of a few details. The tufting of the back and seat cushions and the tape-covered cord that outlines their edges (figs. 49, 50) are somewhat conjectural, since these features cannot be determined from a bare frame. Both details, however, are based upon sound historic precedent and contribute to the final appearance of the sofa. Much like the upholstery cap for the Norfolk chair (fig. 43), the new upholstery system devised for the sofa minimizes intrusion into the frame.[17]

The preceding case studies document some of the materials and techniques used by upholsterers working in Virginia during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In addition, these studies document the steps taken by current scholars and conservators to understand and preserve original upholstery, to study and conserve seating furniture that survives in skeletal form, and to replicate the early upholstery schemes determined from such studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Luke Beckerdite, Wallace Gusler, Ronald Hurst, Jonathan Prown, David Peebles, Byron Wenger, Sally Gant, and Martha Rowe. We are especially grateful to Albert Skutans for his contributions to upholstery conservation at Colonial Williamsburg.

F. Carey Howlett, “The Identification of Grasses and Other Plant Materials Used in Historic Upholstery,” in Upholstery Conservation, edited by Marc A. Williams (East Kingston, N.H.: American Conservation Consortium, Ltd., 1990), pp. 66–91.

Kathy Francis, “Fiber and Fabric Remains on Upholstery Tacks and Frames: Identification, Interpretation, and Preservation of Textile Evidence,” in Williams, ed., Upholstery Conservation, pp. 63–65.

F. Carey Howlett, “Admitted into the Mysteries: The Benjamin Bucktrout Masonic Master’s Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 195–232. Robert Carter Papers, M-82-8, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

Will of Francis Roberts, December 13, 1698, Accomack County, Virginia, Wills, etc., 1692–1715, p. 398a. Estate inventory of Anthony Butts, March 16, 1718, York County, Virginia, Orders, Wills, 8c. No. 15, Part 2, 1716–1720, p. 415. Estate inventory of John Walker, April 19, 1745, Middlesex County, Virginia, Will Book C, 1740–1748, p. 240.

Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) is an epiphyte common to the coast of North America. Because it was shipped north beginning in the eighteenth century for use as a stuffing material, its presence in a piece of upholstered furniture offers little indication of the object’s place of manufacture. Typically the moss was processed by rotting away the impermanent outer skin, leaving only the tough black fibers that are similar in appearance to curled hair (except for the nodes and branches). The term “Spanish beard” appears in Duke de la Rochenfouchault Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America in the Years, 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London, 1800), p. 441.