Flask and bank, mid-nineteenth century. Rockingham-glazed earthenware. Left: Probably English. H. 9". Right: English or American. H. 5 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo by author.)

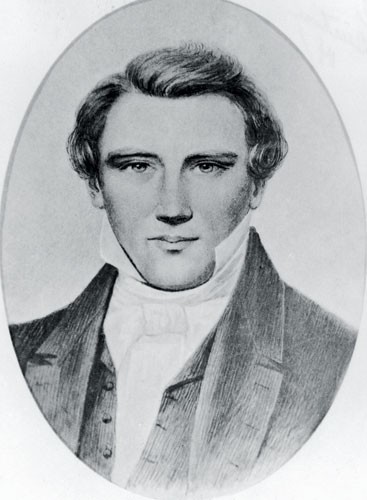

Charles William Carter, Joseph Smith Jr. Etching, 1886. 5" x 7". (Courtesy, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.)

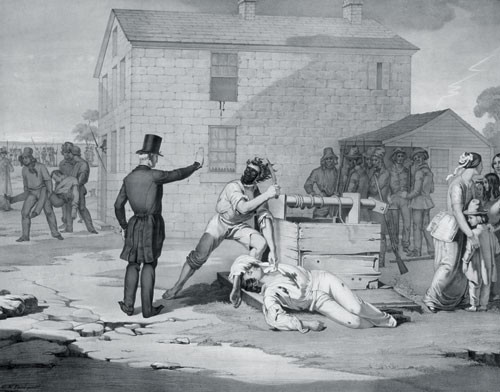

Lithograph by Nagel and Weingaertner after C. G. Crehen, Martyrdom of Joseph and Hiram Smith in Carthage Jail, June 27, 1844 (New York, 1851). (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.)

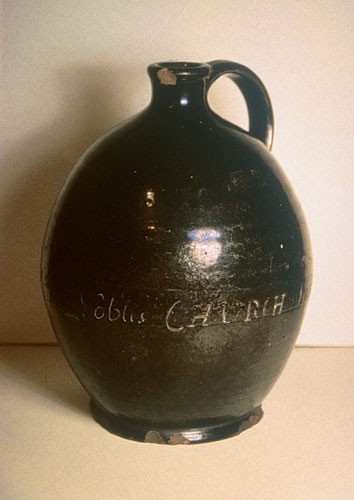

Communion jug, attributed to Daniel Bayley, Newburyport, Massachusetts, 1763. Manganese-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". Inscribed: “For the use of Mr. Noble’s CHURCH July 10, 1763.” (Courtesy, Old York Historical Society, York, Me.) This jug—one of the earliest dated pieces of American redware—was used to store wine for communion services at the Fifth Parish Congregational Church of Newbury, headed by Reverend Oliver Noble. It is the only documented example of eighteenth-century ecclesiastical redware produced in New England.

Bank, 2006. Tin. H. 4". Mark: on lid, “my MISSON SAVINGS BANK / I hope they call me on a mission”; on underside, “Made in China.” This modern version is currently being sold at the Brigham Young University Book Store in Salt Lake City, Utah. (Author’s collection; photo by author.)

The recent discovery of two unusual, inscribed yellow ware vessels gives credence to the old adage that books should not be judged by their cover—and suggests that their titles should be carefully read, too.

An intriguing Rockingham-glazed “man-on-a-barrel” spirits flask and a novelty bank in the shape of a jug appear to depict merriment and the consumption of alcohol (fig. 1). However, the inscriptions on the flask and the bank indicate that these objects were more than conventional representations of familiar forms. Given the period in which they originated, it seems likely that both were made by potters responding to the proselytizing of religious missionaries active in the United States and England during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Each vessel bears a written message applied by the maker in order to advocate a particular cause or point of view, which is highly unusual for Rockingham-glazed ware. Even though the messages deal with serious matters, they are presented with veiled humor or irony.

The impressed inscription “J. Smith/The Mormon Prophet/1830” seems a straightforward commemoration of Joseph Smith Jr., a religious visionary from Palmyra, New York, who in 1830 organized the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and published the revolutionary Book of Mormon (fig. 2). That the potter inscribed the message on a toper flask, however, makes clear the intent to lampoon rather than commemorate. The piece is a direct assault on “The Word of Wisdom,” a revelation Smith purportedly received at Kirtland, Ohio, in 1833, which advised against the consumption of wine, tobacco, hot drinks, and strong drinks.

Revered by millions today, this influential religious leader and his followers were driven from several Midwest towns prior to settling in Salt Lake City, Utah. The open hostility and violence they experienced along the way culminated in 1844, when Smith and his brother Hyrum, who were imprisoned in a county jail in Carthage, Illinois, were brutally shot and killed by an angry mob (fig. 3). This flask is a lasting reminder of resistance to the controversial teachings of Smith and his Mormon missionaries, many of whom sought converts in England who would relocate to Utah.

Another potter created the unusual Rockingham-glazed bank using an ovoid jug form and applying to it the words “I AM A MISSIONARY JUG” with molded, raised letters. In contrast to the flask, this self-promoting money holder was personified in order to collect funds in support of the outreach of religious missionaries, who often traveled to distant lands. Appropriating a jug form for this benign purpose was not necessarily controversial, as these vessels were used for nonalcoholic liquids as well as spirits; they were also used by churches to hold communion wine (fig. 4).[1]

People of all ages, backgrounds, and religious denominations during this period actively supported the charitable work of missionaries; children in particular were encouraged to set aside a portion of their earnings to help these workers. Even Abraham Lincoln’s son, Willie, who was known for his thoughtful and studious nature, reportedly donated his allowance to a missionary society.[2] Traditional missionary savings banks continue to be made today, although mass-produced metal has replaced handcrafted pottery (fig. 5).

It should be noted that nineteenth-century Rockingham-glazed vessels associated with religious matters are relatively rare (neither of the objects under discussion is in any of four exhaustive collector guides covering a wide range of yellow ware forms).[3] One notable exception is the well-known Rebecca-at-the-Well teapot. Based on a biblical story, this popular motif was created by potter Edwin Bennett of Baltimore and later copied by several East Coast competitors. [4]

Different types of ceramic vessels with human forms and characteristics have existed for centuries, and many were intended to personify, commemorate, or satirize a wide range of historical figures.[5] Potters in general are infamous for interjecting crass humor into their craft. The more celebrated examples include dribbling puzzle jugs, mugs with frogs, chamber pots containing excrement, and, of course, vessels depicting the English drinking character Toby Fillpot.

The two Rockingham-glazed novelty items shown here offer commentary on the work of religious missionaries during the nineteenth century and reflect how potters artfully participated in social discourse during this period. In turn, while these vessels no longer retain their intended function, they do continue a dialogue that should now be considered historically significant.

John E. Kille, Assistant Director, The Lost Towns Archaeology Project; jkille@aacounty.org

John Kille, “Fire the Kiln, Raise the Flag, and Praise God: The Bayley Jug and the Convergence of Craftmaking, Politics, and Religion in Eighteenth-Century New England,” in Piecing It Together: Ceramics and the Social History of Early New England (York, Me.: Old York Historical Society, 1997), pp. 25–42. The subject of this study is the rare earthenware communion jug illustrated in fig. 4 of this article.

Philip B. Kunhardt Jr., Philip B. Kunhardt III, and Peter W. Kunhardt, Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography (New York: Random House, 1992), p. 290. Willie died of typhoid fever in 1862 at age eleven.

See Joan Leibowitz, Yellow Ware: The Transitional Ceramic (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1985); Lisa S. McAllister and John L. Michel, Collecting Yellow Ware (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1995); Lisa S. McAllister, Collector’s Guide to Yellow Ware Book II (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1997); and Lisa S. McAllister, Collector’s Guide to Yellow Ware Book III (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 2003). A similar flask is pictured in McAllister and Michel, Collecting Yellow Ware, p. 101. However, it is incised with the name “JIM CROW,” a blackface character performed by American entertainer Thomas Dartmouth Rice, who brought his act to English theaters in 1836.

Jane Perkins Claney, Rockingham Ware in American Culture, 1830–1930: Reading Historical Artifacts (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2004), pp. 81–84, in which the popularity and successful marketing of Rebecca-at-the-Well teapots are explored.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 301–27. This chapter provides an excellent discussion of nineteenth-century English portrait and Toby flasks, as well as illustrations of several of these vessels.