Tile fragment, Holland, ca. 1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County; photo, Al Luckenbach.) Pikeman tile recovered from Burle’s Town Land (18AN818).

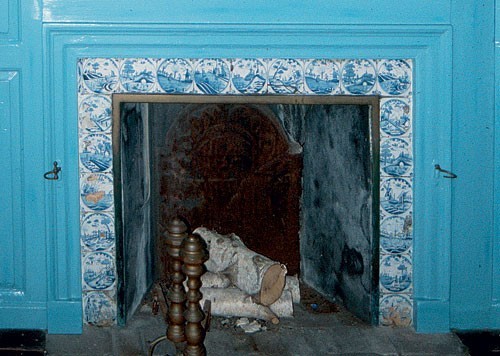

Fireplace with hearth surround of delftware tiles at the Wanton-Lyman-Hazard House, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1700. (Photo, Carl Lounsbury.)

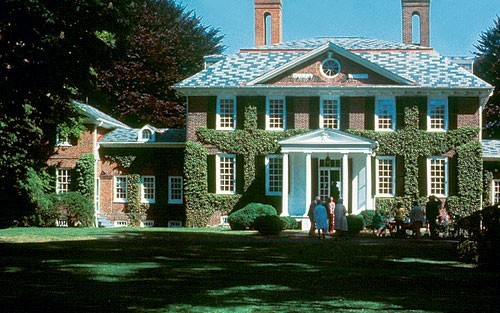

Tulip Hill, southern Anne Arundel County, Maryland, built between 1756 and 1762. (Photo, Donna Ware.)

Fireplace at Tulip Hill, with hearth surround of tiles and mid-eighteenth-century wooden overmantel and moldings. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

One of the ca. 1740 delftware tiles bordering the hearth illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, John Kille.) This tile depicts Tobias Catches the Fish, a biblical scene.

One of the ca. 1740 delftware tiles bordering the hearth illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, John Kille.) The tile pictures the Tower of Babel.

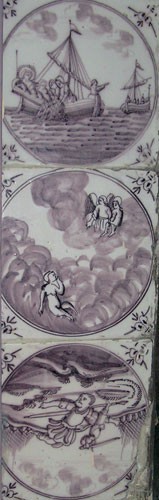

Detail of ca. 1740 delftware tiles bordering the lower left portion of the hearth illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, John Kille.) The tiles depict (top to bottom) Christ and Fishermen; Lazarus in Heaven; and David Beheads Goliath (upside down).

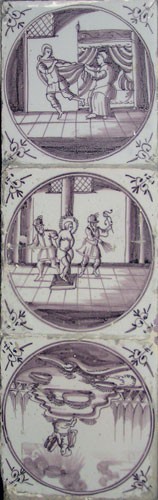

Detail of ca. 1740 delftware tiles bordering the lower right portion of the hearth illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, John Kille.) The tiles depict (top to bottom) Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife; Christ at the Column; and Moses Receiving the Laws (upside down). (Photo, John Kille.)

The use of decorated tin-glazed earthenware tiles to decorate the interior of European dwellings was quite fashionable from the late sixteenth through the mid-eighteenth centuries. As is often depicted in period genre paintings, these tiles were used both as baseboard or washboard treatments and, most frequently, as decorative fireplace surrounds. Similar “gally paving tyles” were used as decorative flooring stretching back to medieval times. By the eighteenth century, tin-glazed earthenware tiles “for chimnies” were being produced, principally in England, Holland, Italy, and Portugal, in countless stylistic varieties.

The fashion of decorating with tin-glazed earthenware tiles was transported to the Chesapeake region with the first colonists. Archaeological examples have been recovered from a number of colonial town sites and outlying plantation sites in the Chesapeake, including several locations in Virginia—Jamestown, nearby James City County, and Williamsburg—and in St. Mary’s City, Maryland. In Anne Arundel County, Maryland, tiles have been excavated at both Providence and London Town (fig. 1).[1]

Despite apparent widespread use, extant buildings in this country with in situ fireplace tile treatments are surprisingly rare. Four examples are known from Charleston, South Carolina, and several from areas farther north—Marblehead and Portsmouth, Massachusetts; Newport, Rhode Island (fig. 2); West Coxsackie, New York; and Philadelphia.

Carl Lounsbury, an architectural historian with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, has been assembling a database of documentary references to specific architectural features for nearly twenty years.[2] His work contains numerous references to the use of fireplace tiles, beginning with a 1702 travel narrative about New York City that states: “the hearths were laid with the finest tiles I ever saw...,”[3] followed by thirteen separate entries between 1720 and 1751 that mention what are variously described as “Dutch,” “white,” or “chimney tiles,” often using a combination of these terms. A single reference in 1752 to “galley tiles” is followed in 1756 by a lengthy description in A Complete Body of Architecture, which states: “These Dutch tiles were once in great reputation in ordinary houses but at present they are grown into neglect, and that not without reason...being tenderer and more easily damaged.”[4]

After a noticeable gap in the documentary record, fireplace tiles underwent a period of resurgence. Between 1765 and 1784 seven references to tiles often include the descriptors “neat copper-plate chimney tiles,” “copper plate printed tiles,” and “Liverpool tile.” The new fashion was undoubtedly related to the production during this period of transfer-printed tin-glazed earthenware and creamware tiles.

Among standing structures in the Chesapeake Bay region, only one remains that has original colonial fireplace tiles in situ: Tulip Hill, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (fig. 3). Built between 1756 and 1762 and currently owned by the Chaney family, who have been prominent county residents since the 1650s, Tulip Hill is one of the finest eighteenth-century, five-part Georgian houses in the United States. An account book kept during the construction by its owner, Samuel Galloway, offers valuable information about the building,[5] although it does not specifically mention the tiles. Suggesting their origin, however, interesting new documentary evidence reveals that Samuel Galloway’s father, John Galloway, who married Jane Roberts Fishbourne in 1744, purchased ten dozen “Holland tyles” from the estate of her former husband, William Fishbourne, of the same year.[6]

This sole remaining tiled fireplace surround is located in a second-floor bedchamber in the southeast corner of the mansion’s main block. If other examples ever existed in the home, they were updated in later renovations, particularly with the circa 1790 addition of wings and hyphens to the structure. The construction of the surviving fireplace is typical of the earlier eighteenth century, with a shelf mantel, an overmantel, and earthenware floor tiles used as the hearth base (fig. 4).

The surround is ornamented with thirty-two Anglo-Netherlandish, manganese-decorated tiles whose decoration is principally biblical in nature (figs. 5-8). Depicted are sixteen Old Testament scenes, eleven New Testament scenes, two landscapes, and three unidentifiable scenes. Six tiles were altered to reflect the arched top of the hearth opening; some were cut to near slivers, thus accounting for the unidentified scenes, and two were placed on their sides. Curiously, the bottom tile on each side was inserted upside down (figs. 7, 8). This peculiarity is unexplained, as no evidence suggests that there were later repairs.

A list of the motif depicted on each tile and its biblical reference (if one exists) is presented below.

| Top Row | Motif | Biblical Passage |

| A1 | Jonah and the Whale | Jonah 2:10 |

| A2 | Moses and Bronze Serpent | Numbers 21:9 |

| A3 | Moses and Pharaoh’s Army? | Exodus |

| A4 | Tower of Babel | Genesis 11 |

| A5 | Joseph Interprets for the | Genesis 40:8 |

| Cupbearer and the Baker | ||

| A6 | The Circumcision | Luke 2:21 |

| A7 | Joseph Interprets for the | Genesis 40:8 |

| Cupbearer and the Baker | ||

| A8 | Expulsion from Garden of Eden | Genesis 3:24 |

| A9 | Christ Heals the Blind Man | John 9:6 |

| A10 | Noah and the Great Flood | Genesis 7:19 |

| Second Row | ||

| B1 | Coastal Landscape Scene | n/a |

| B2 | Christ Washes Disciples’ Feet | John 13:5 |

| B3 | Christ and the Fishermen | Luke 5:5 |

| B4 | Unidentified—fragmentary | n/a |

| B7 | Unidentified—fragmentary | n/a |

| B8 | Unidentified (stone wall) | n/a |

| B9 | Christ Carries the Cross | John 19:17 |

| B10 | Pilate Washes His Hands | Matthew 27:24 |

| Left Column | ||

| C1 | Christ Heals the Blind Man | John 9:6 |

| D1 | Tower of Babel | Genesis 11 |

| E1 | Samson Takes the Doors of Gaza | Judges 16:3 |

| F1 | Moses Receives the Laws | Deuteronomy 5:22 |

| G1 | Christ and the Fishermen | Luke 5:5 |

| H1 | Lazarus in Heaven | Luke 16:22 |

| I1 | David Beheads Goliath | 1 Samuel 17:51 |

| Right Column | ||

| C10 | The Circumcision | Luke 2:21 |

| D10 | Moses Receives the Laws | Deuteronomy 5:22 |

| E10 | Tobit Catches the Fish | Tobit 6:3 |

| F10 | Pastoral Landscape Scene | n/a |

| G10 | Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife | Genesis 39:12 |

| H10 | Christ at the Column | John 19:1 |

| I10 | Moses Receives the Laws | Deuteronomy 5:22 |

The disappearance of tile fireplace surrounds in colonial-period homes in the Chesapeake might be due to renovation, as updating them and their mantels was common—and it might also be related to their fragility. Given that wooden—and later slate, and perhaps even marble—panels became the fashionable medium of fireplace surrounds in later years, it is intriguing to contemplate that renovators might have entombed rather than removed the original tiles. Until such hidden treasures come to light, however, Tulip Hill remains the sole illustration of this once widespread treatment in the Chesapeake Bay region.

Al Luckenbach, Anne Arundel County Archaeologist, Director,

Lost Towns Project; alluck@aol.com

Gary Wheeler Stone, Seventeenth-Century Wall Tile from the St. Mary’s City Excavations, 1971–1985, St. Mary’s City Research Series, no. 3 (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City, 1987); John L. Cotter, Archaeological Excavations at Jamestown Colonial National Historical Park and Jamestown National Historic Site, Archeological Research Series, no. 4 (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1958); Al Luckenbach, Providence 1649: The History and Archaeology of Anne Arundel County, Maryland’s First European Settlement (Annapolis: Maryland State Archives; Crownsville: Maryland Historical Trust, 1995); John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1994).

Carl R. Lounsbury, An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Howard Henry Peckham, “Madam Knight’s Journal: A Woman Travels to New York, 1704,” in Narratives of Colonial America, 1704–1765, edited by Howard H. Peckham (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley and Sons, 1971), p. 37.

Isaac Ware, A Complete Body of Architecture: Adorned with Plans and Elevations from Original Designs, in Which Are Interspersed Some Designs of Inigo Jones Never Before Published (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), p. 63.

Donna M. Ware, Anne Arundel’s Legacy: The Historic Properties of Anne Arundel County (Annapolis, Md.: Anne Arundel County, 1990), p. 59.

J. Reaney Kelly, “‘Tulip Hill’: Its History and Its People,” Maryland Historical Magazine 60, no. 4 (December 1965): 349–403.