Rhoda Lopez with Gerald Thiebolt, Memorial Wall, First Unitarian Universalist Church of San Diego, begun in 1978. Stoneware. L. 40' (originally 33'). (Unless otherwise noted, photos by Gerald Thiebolt.)

Closer view showing the three levels of relief modeling: undulating trees, stamped designs, and memorial plaques.

As a joyful memorial for a living church, the wall is continuously updated, as shown in this close-up view.

Gerald Thiebolt, Chalice, 2003. Stoneware. H. 33", D. 21".

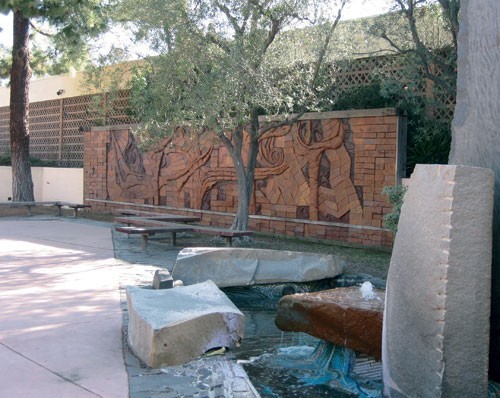

Rotunda, San Diego Museum of Art. H. of fountain 7'. (Courtesy, San Diego Museum of Art, The John M. and Sally B. Thornton Rotunda.)

Detail, central fountain basin, San Diego Museum of Art. The tiles were designed, made, and installed by the author. In this view the basin resembles an elegant turquoise necklace.

Gerald Thiebolt, landscape design, 1996. Handmade decorated stoneware bricks are combined with manufactured terracotta bricks in this San Diego yard.

Close-up view of motifs stamped into stoneware clay and fired for use in the walkway of the yard illustrated in fig. 7.

The manufactured brick, chosen for its color and texture, was reshaped for use in the landscape illustrated in fig. 7.

During my years studying architecture I always enjoyed working in three dimensions to communicate a design, as with models and sculpture, more than in two-dimensional drawings showing various views. The look and feel of various materials, their textures, patterns, and colors, appealed to my visual and tactile senses. As I look back, these interests played an important role in formulating my work in clay.

I wanted to use my architectural skills in a positive way, so in the 1960s, before I graduated from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, I signed up for the Peace Corps and was sent to northern Iran as an architect for a small city. It was a remarkable experience, being dropped into an environment in which a few simple materials—brick, glass, steel, and sometimes concrete—are used to create an amazing variety of building forms.

A view from a minaret in the desert city of Yazd presents itself as a vast sculpture of khaki-colored domes, rectangles, squares, undulating roofs, dark courtyards—all variations of the same color, positive and negative, dark and light. Beautifully tiled mosques and public buildings, covered in glazed tiles of turquoise and arabesque designs of yellow, white, and blue, glisten in the distance. Part of this sculptural phenomenon was shaped by continuity of materials. It created a “language,” whereby domes, half-domed arches, and cube shapes—all simple geometric forms—became the nouns; the rich surface decoration in bricks and tiles were the verbs; and the rhythms and counterrhythms of pattern, texture, and color were the adjectives. Even the rhythm of calligraphy was used to emphasize archways and intense patterns in squinches pointed to the transition of a square frame to a circle, which became the base of the dome. Arabesque designs in the form of plants inside some of the domes create an ethereal world of abundance with the heavens as a backdrop.

This approach to design was quite different from the “less is more” concept of design I studied in school. The worldview of American architecture was a technical one, with no ornamentation and virtually no concept of a cultural component other than its own. What I experienced in the Middle East was more humanistic and enriching in scope and scale. The use of simple materials was reinforced during my six-month trip to India and, in a very different way, in Japan, where I lived for one and a half years.

Returning to the United States during a recession was challenging and I had two short-lived jobs in architecture before I was put out of commission by a bicycle accident. That event instigated my career in clay. I learned to hand build from a friend who was taking classes and began working night and day in an explosion of creativity. I loved the plastic quality of clay, the ability to shape and texture the material at will, and I decided to get a degree in ceramics.

After three months in school, my professor referred me to Rhoda Lopez, a ceramic artist working in an architectural scale who also had a teaching studio affiliated with the University of California at San Diego. After a few years Rhoda and I became partners when she initiated work on her largest project—the Memorial Wall, nine feet high and thirty-three feet long, for the First Unitarian Universalist Church of San Diego (fig. 1). She designed a joyful, prominently placed work that would relate to the church community on a daily basis. Her design contained many abstract forms and featured a series of plaques impressed with the names of deceased church members.

I started the project by designing and constructing the simple A-frame structure to support the clay. With the help of assistants Rhoda began installing the clay pieces, much like a puzzle, while I was finishing graduate school. The project stalled temporarily when Rhoda fell ill, but after she recovered the two of us resumed working together and created the Memorial Wall with three levels of relief: soft, undulating tree forms in the highest relief; lower-relief plaques contrasting crisp angular forms; and a darker, lowest-relief textured background (fig. 2). To produce the textures, we impressed five tools and/or found objects in the clay to create new patterns in never-ending designs in an infinite number of motifs.

Rhoda and I continued working together during a fifteen-year partnership that ended with her untimely death. We collaborated on many projects, including murals for other public buildings, sculptural fireplaces, and additional projects for the First Unitarian Church. In 1992 two additions to the Memorial Wall—one on each side—were completed, increasing its length to forty feet. It continues to be a vital part of the First Unitarian Church community, as names are continually added (fig. 3), and it is viewed as a joyful place that unites the congregation; indeed, many couples arrange to be married before it.

Since making the wall I have continued producing pottery for this church, including a “chalice” used to hold a flame during services (fig. 4). Measuring twenty-one inches in diameter by thirty-three inches high, the piece contains sculptural elements that directly relate to the Memorial Wall. It was designed with ease of use in mind; it has wheels hidden inside the base so it can be moved when not in service.

Another project of mine is on view in the rotunda of the San Diego Museum of Art. As part of the centrally located fountain designed by architects Robert Thiele and Spencer Lake, I designed, made, and installed the tiles for its basin (figs. 5, 6).

Although I do wheel-throw pots, my creation of architectural clay designs continues to this day, currently including two that are yet to be built: a memorial wall that is seventy feet long and varies in height from seven to eleven feet; and five shaped walls around a gathering space with a brick surface and a stream of handmade textured brick. My interest in designing architectural spaces has led me to integrate it in unusual ways into environments using manufactured materials, such as terracotta bricks, and then combining it with my own work.

Recently, in an architectural landscape, I created a flow of lines and patterns that extends through the courtyard to the outside entry and to the drive (figs. 7, 8). I included five different colors of brick and blended them with my handmade stoneware elements (fig. 9). From an agave-like desert plant form at the entryway flow primordial roots of handmade textured stoneware bricks that wind their way throughout the project, representing the root from which life springs and is sustained. My experiences with deserts in southern California and abroad have taught me to appreciate the tenacity of life, which has been a theme in much of my work. This particular commission took me full circle, because I embellished flat surfaces with color, pattern, and texture, similar to the surface designs in Persian architecture that were revealed to me at the beginning of my career.

Gerald L. Thiebolt, Studio Associate, Clay Associates;

info@clayassociates.org