Warren Bakley, Construction, 1994. Stoneware. H. 30". (Private collection; photo, Martin Trailer.) Mixed clays were used to create the six architectural columns in this sculpture. The exteriors of the columns are decorated with a black iron oxide slip.

Warren Bakley, Construction, 2003. Stoneware. L. 42". (Private collection; photo, Warren Bakley.) This elongated wall hanging was slab formed and partially sandblasted to create texture and variation. Kiln-fired metallic oxides give the sculpture its high sheen.

Warren Bakley, Construction, front and back, 1986. Stoneware. H. 10". (Private collection; photo, Martin Trailer.) This sculptural construction, slab formed from mixed clays, was decorated with iron oxide and partial glaze.

Warren Bakley, Construction, front and back, 1986. Stoneware. H. 10". (Private collection; photo, Martin Trailer.) This sculptural construction, slab formed from mixed clays, was decorated with iron oxide and partial glaze.

Warren Bakley, Construction, 2005. Earthenware. L. 23". (Private collection; photo, Warren Bakley.) A partially glazed slab-formed wall tile, this incised and stamped wall hanging was created using mixed earthenware.

Warren Bakley, Construction, 2004. Stoneware. H. 12". (Bakley collection; photo, Warren Bakley.) Slab formed, this construction displays partial glaze and vitrified kiln washes.

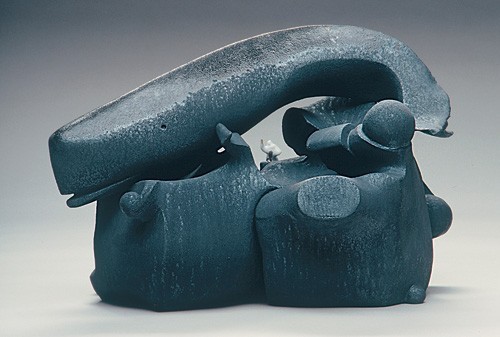

Warren Bakley, Sculpture, 1993. Stoneware. H. 10". (Private collection; photo, Martin Trailer.) This sculpture was inspired by Dr. Jonas Salk's declaration in 1993 that he would infect himself with the AIDS virus to prove the effectiveness of his experimental antiviral procedure. Jonas is the little white figure on the surfboard attempting to ride a turbulent ocean while taming a large whale.

I have come to see my creativity with clays as part of a ceramic tradition that in this century is showing movement away from utilitarian objects toward more decorative ones. I would describe myself as a designer doing sculpture within the ceramic process. It is from my role as a designer of spaces, interiors, and furnishings that my ceramics take their architectural structure and form. My intent is to express with available indigenous materials something that speaks not only of the time but also, I hope, speaks something of myself (figs. 1, 2).

Traditionally, the role of the ceramist as an independent potter was to supply utilitarian objects. With plastics, mass-produced ceramics, and other man-made materials replacing functional handmade clay items, that role has evolved to the production of objects with very little purpose other than to delight the eye and/or embellish a specific singular lifestyle. Current popular publications attest to an affluent population that seeks ceramics for their artistic appeal, their eccentricity, or merely to fill a void in a larger space. This suggests the notion that a clay object can be valued for its ability to satisfy something of the inner self, like a found shell or pottery sherd that has no specific usefulness but engenders in the beholder a sense of security in that it cannot become obsolete.

My introduction to clay was in New Jersey at age seven. The clay lay luminous white beneath the clear water of a natural spring surrounded by grasses growing through a sandy reddish soil. From this clay I made a small pinch pot that was fired in the oven of a woodstove. The pot did not survive, but my interest in clay and its possibilities did. The education of designers and architects very often includes classes in ceramics as an introduction to three-dimensional form. It was in a class such as this that clay again captured my attention and sparked an intense interest in the ceramic arts that has lasted a lifetime.

Throughout my college years and until I moved to California, I worked with clays dug from fields, river bottoms, and erosion ditches in areas of southern New Jersey. These clays were unique in that they needed no processing other than wedging. Depending on the sources, they offered a satisfying variety of mature firing ranges. They were excellent for potting and structurally good for hand building. In their raw state they possessed exceptional color inspiration. This, for me, is an important part of the creative process.

Naturally formed clays are not readily available in California. The commercial clays appear to be imposters, man-made parodies manufactured from a boringly consistent recipe for color, texture, and sculptural properties. They have little indigenous presence and, sadly, seem robbed of their rightful alluvial lineage. Despite this reality, I am still affected by the natural coloring and tactile qualities of raw clays, and these qualities play a major role in how I am feeling during the creation of each piece (figs. 3, 4). In completing each piece the application of the glaze is minimal. This is deliberate, to create a natural continuation of the adjacent unglazed surfaces. This allows the sculptural form to dominate, with the surface remaining open to the play of light and shadow (fig. 5).

I see my use of clay not only as the means to express my creative thoughts but also as being part of objects that transcend the bareness of plastics and promote the use of natural materials. I believe that when used with integrity, traditional materials—just like shells and sherds—do speak for their time, as well as to the soul of the viewer (fig. 6).

Warren Bakley, Designer; sbakley@san.rr.com