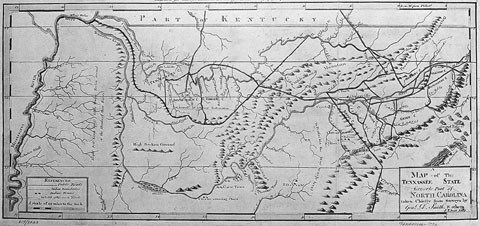

Daniel Smith, map of Tennessee, Philadelphia, 1795. Engraving on paper. 10 1/4" x 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, John Bivins.)

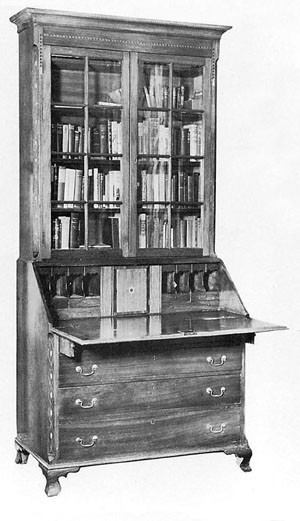

Desk-and-bookcase, Winchester area, Virginia, 1795. Cherry with yellow pine. H. 103 3/4", W. 42 1/4", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 2.

Desk-and-bookcase, Philadelphia, 1760–1770. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 109 3/4", W. 45", D. 25". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of George H. Lorimer.)

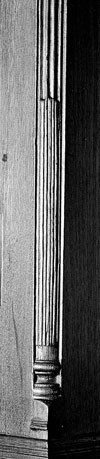

Detail of a quarter-column on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 2.

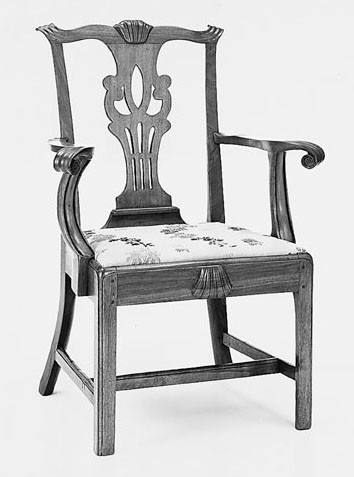

Armchair, Winchester area, Virginia, 1769. Walnut with walnut and white pine. H. 40", W. 28 3/8", D. 18 3/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Rock Castle, Hendersonville, Tennessee, 1796. (Photo, John Bivins.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Nashville area, Tennessee, 1795–1805. Walnut with tulip poplar and walnut. H. 106 9/16", W. 44 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Ladies Hermitage Association; photo, John Bivins.)

Detail of the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of a quarter-column and writing surface lock rail miter on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 9.

Chest of drawers, Nashville area, Tennessee, 1795–1805. Walnut with tulip poplar.

H. 34 3/8", W. 40 5/8", D. 20 11/16". (Courtesy, Ladies Hermitage Association; photo, John Bivins.)

Desk, Nashville area, Tennessee, 1790–1805. Walnut with tulip poplar, walnut, and cherry. H. 45 1/4", W. 45 1/4", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Tennessee State Museum; photo, John Bivins.)

Ramsey House, Knoxville, Tennessee, 1798. (Photo, John Bivins.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1790–1800. Walnut with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 87 1/4" (without feet), W. 41 7/8", D. 35 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The brasses, feet, and small strip added to the bottom of the base molding are incorrect replacements.

Detail of the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of a quarter-column on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of chamfered corner of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15.

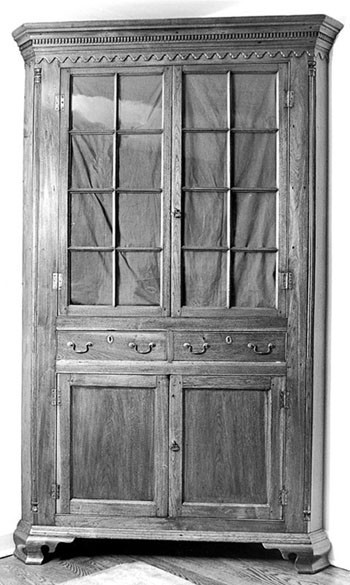

Corner cupboard, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1790–1800. Walnut with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 89 1/4", W. 44" at front face with 5 1/4" returns. (Private collection; photo, John Bivins.)

Detail of the cornice and a quarter-column on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 19.

Detail of the cornice, rosettes, and plinth of the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 19.

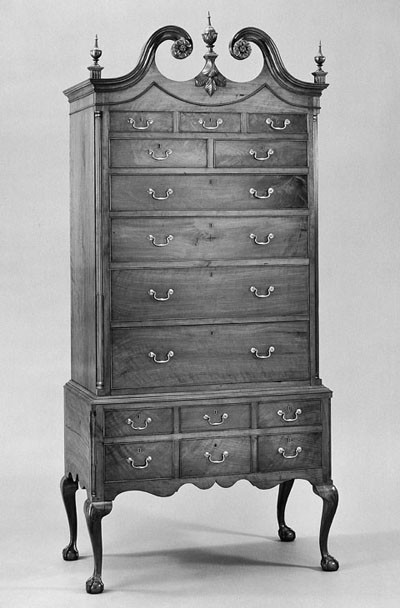

High chest, Winchester area, Virginia, 1795. Walnut with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 97", W. 44", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the pediment of the high chest illustrated in fig. 22.

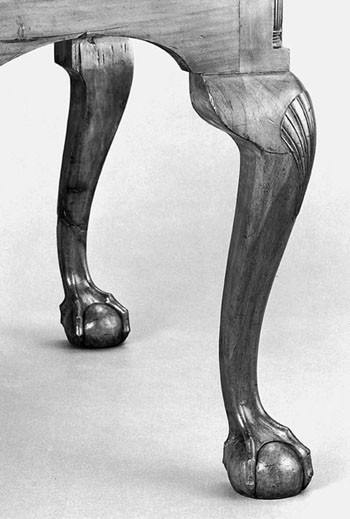

Detail of the leg of the high chest illustrated in fig. 22.

Corner cupboard, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1795–1810. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 87 3/4", W. 50 3/4" at front face with 5 7/8" returns. (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The cornice molding rises above the top of the case and consists of separate moldings: the ogee below the dentil course is a single vertical piece that rises to the crown as does the dentil course; the cove is a single vertical piece attached to the dentil course; the crown is a horizontal piece that covers the top edges of the other moldings; the running astragal frieze is glued to the case below.

Detail of a quarter-column on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, John Bivins.)

Chest of drawers, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1795–1810. Walnut with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 49 5/16", W. 39", D. 23 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The cornice on the chest of drawers is a simpler version of the cornice on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 25. The molded board that forms the top of the case and the face-nailed cove molding conceal the dovetails that join the case sides to a board below the top.

Desk-and-bookcase, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1795–1810. Cherry with yellow pine. H. 96" (without feet), W. 42 1/2", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Lawson-McGhee Library; photo, John Bivins.) This example is somewhat unusual in being made of cherry. Walnut is the most common primary wood in East Tennessee furniture.

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 28. (Courtesy, Lawson-McGhee Library; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1795–1810. Walnut with yellow pine and walnut. H. 97", W. 46 3/4", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Blount Mansion; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30.

Detail of the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30.

Tall chest, Knoxville area, Tennessee, 1795–1810. Cherry with yellow pine, tulip poplar, walnut, and cherry. H. 63 3/4", W. 54 3/4", D. 22 5/8". (Courtesy, Ramsey House; photo, John Bivins.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Greeneville area, Tennessee, 1800–1820. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 92 1/4", W. 45 3/4", D. 20 3/8". (Private collection; photo, John Bivins.)

Corner cupboard, Greeneville area, Tennessee, 1795–1820. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 95 1/4", W. 47" at front face with 4" returns. (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Greeneville area, Tennessee, 1800–1820. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 96", W. 44 1/2", D. 22 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Helga Studio.)

During the late 1760s, the availability of inexpensive land attracted settlers to the northeastern corner of Tennessee. Although historians David Hackett Fischer and James C. Kelly have noted that the “sweep of settlement through the Valley of Virginia led inexorably into the valley of East Tennessee,” settlers also came from other areas, including the coastal and piedmont regions of Virginia and North Carolina. While the earliest settlements were being established, parties of hunters passed through the Cumberland Gap and over the Cumberland Plateau into Middle Tennessee (fig. 1). In 1779 and 1780, three permanent settlements, including Nashville, were established in the Cumberland River Valley in northern Middle Tennessee. Although some of the earliest settlers in Middle Tennessee stopped briefly in the eastern part of the state, the two regions were separated by mountains and “three hundred miles of wilderness.” Because of this geographic barrier, East Tennessee and Middle Tennessee developed simultaneously yet independently of each other.[1]

The population in both regions continued to grow throughout the 1780s, particularly after the Revolution when the state of North Carolina sold land to generate revenue and granted land to soldiers. In Middle Tennessee, the earliest settlements centered around Davidson County, where Nashville is located, and Sumner County, the site of settlement in 1779. In upper East Tennessee, Jonesboro, Rogersville, and Greeneville predate Knoxville, which was not settled until 1786. Knoxville, however, became the largest town and the political and economic center of the region soon after William Blount, the newly appointed governor of the Territory South of the River Ohio, chose it as the site of his capital in 1791. The 1795 census of the territory lists 77,272 inhabitants, indicating that settlement grew rapidly in less than thirty years.[2]

As cabinetmakers, journeymen, and apprentices moved from southeastern Pennsylvania into the Valley of Virginia and then into Tennessee, they adapted their designs and construction methods to suit the demands of their new clientele, who often had preconceived notions about what was fashionable. As the largest town and most important style center in the Valley of Virginia, Winchester exerted a powerful influence on objects produced in the Valley and westward. As makers and patrons moved further from the original design source, however, forms were adapted and regionalized. The furniture discussed in this article shows how Delaware Valley styles were interpreted by artisans in Winchester and outlying areas of Frederick County (see Wallace Gusler article in this volume, p. 228, fig. 1) and how they were further developed and regionalized by cabinetmakers and their patrons in Middle Tennessee and East Tennessee.[3]

Like many Winchester case pieces, the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 2 has several details commonly found on Delaware Valley furniture. The shape of its pediment bears a close relationship to examples from Philadelphia and its hinterlands, but the swagged astragal molding on the tympanum contrasts with the elaborate carving found on some Delaware Valley pieces (figs. 3, 5). Likewise, the writing compartment of the Winchester desk-and-bookcase follows a typical Philadelphia plan in having a prospect door flanked by document drawers and pigeonholes with double-ogee valances above two tiers of drawers (figs. 2, 4). Although the Philadelphia desk-and-bookcase shown in figure 5 has shaped interior drawers, most desks made there during the last quarter of the eighteenth century have plain drawer fronts like the Winchester example. The Winchester desk also has ogee feet with filleted, spurred responds. Similar feet occur on Philadelphia case pieces by the mid-1740s and on furniture made outside the city during the last half of the eighteenth century.

By contrast, arched stop-fluting on quarter-columns is a distinctive feature of the Winchester school (fig. 6). Fluted quarter-columns are common on Delaware Valley furniture from the colonial period, but arched stop-fluted ones are unknown. Arched stop-fluted quarter-columns in conjunction with the aforementioned Delaware Valley details occur only on Winchester-school furniture made in the Shenandoah Valley and in Tennessee.[4]

It is difficult to determine when Winchester artisans began producing furniture in the Delaware Valley style. The earliest documented example is a chair with carved shells and Philadelphia-style arms and arm supports dated 1769 (fig. 7); however, most Winchester furniture with Delaware Valley features dates from the 1780s and 1790s. The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 2 is part of a large group of furniture purchased by David Lupton for his house, Cherry Row, built near Winchester in 1794. A related desk from nearby Fauquier County is inscribed “Christopher Frye/ Cabinet Maker/ 1797.” Although similar seating and case forms remained popular in the Valley of Virginia until at least 1800, they would have been considered old-fashioned in Philadelphia at that time. The cabinetmakers’ price list transcribed by Benjamin Lehman of Germantown indicates that rococo forms were being produced in Philadelphia as late as 1786, but during the 1790s an influx of new cabinetmakers and design books from England brought about a stylistic change. In 1795, The Journeymen Cabinet and Chair-Makers Philadelphia Book of Prices set prices for furniture in the neoclassical style.[5]

Although Winchester influences are most apparent in furniture from East Tennessee, one cabinet shop in the Nashville area of Middle Tennessee produced furniture that resembles Winchester work. Because a larger number of shops were involved over a longer period of time in Knox County, the furniture made in the Nashville area will be considered first.

Furniture from the Nashville Area of Middle Tennessee

During his visit to the Cumberland area of Tennessee in 1785, Lewis Brantz wrote, “Nashville is a recently founded place and contains only two houses which, in true, merit the name; the rest are only huts that formerly served as a sort of fortification against Indian attacks.” Similarly, when François André Michaux visited Nashville in 1802, he commented on the existence of only “seven or eight brick houses, the remainder consisting of about 120. . . built with planks.” Men of substance, however, were building large houses in the surrounding countryside by the mid-1790s. Daniel Smith, a member of the party that founded Nashville in 1779 and for whom Smith County was later named, completed Rock Castle in Sumner County in 1796 (fig. 8). Michaux described Cragfont, the stone house built by General James Winchester in Sumner County between 1798 and 1802, as “very elegant for the country.” Lawyer John Overton built Traveller’s Rest, a two-story frame house with a side passage plan, outside Nashville in 1799. The houses constructed in both Davidson and Sumner Counties during this period reflected the growing prosperity of this fertile area of Middle Tennessee.[6]

In addition to building elegant and substantial houses, these men purchased locally made furniture to outfit them. The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 9 descended in the family of Andrew Jackson who, according to oral tradition, used it in his law office. Although several details differentiate the Jackson desk-and-bookcase from the Lupton example (fig. 2), the influence of Winchester styles on Middle Tennessee furniture is apparent. Both desks have central prospect doors, fluted document drawers, and double-ogee-shaped pigeonhole valances. The valances on the Jackson desk are significantly deeper than those on the Lupton example, and the interior drawers are arranged two over one rather than two over two (figs. 4, 10). The Jackson desk also has ogee feet with filleted, spurred responds and stop-fluted quarter-columns. The level stop-fluting on this desk (fig. 11) represents a significant departure from the Winchester school, where stop-fluting was invariably arched (fig. 6).

The Lupton and Jackson desk-and-bookcases are also constructed differently. Like many Philadelphia case pieces, the Lupton example has three-quarter-height, full-bottom dustboards that are dadoed into the case sides and attached to the drawer rails with a tongue-and-groove joint. The Jackson desk-and-bookcase has drawer supports that are dadoed into the case sides and tenoned into the front and rear drawer rails. This framed support system is relatively common on furniture from southeastern Pennsylvania and the southern backcountry. On the Jackson desk, the method of joining the writing surface lock rail to the case sides is somewhat unusual. Typically, the lock rail fits into a blind dado in the case sides and shows on the surface as a vertical joint; however, the maker of the Jackson example mitered the exposed portion of the joint (fig. 11). Like much rural furniture, this desk-and-bookcase is difficult to categorize stylistically. The shape of the cornice, the quarter-columns, and the ogee feet are rococo features, but the extreme verticality of the bookcase is more in keeping with the neoclassical taste. Conversely, the use of dentil molding only on the front of the bookcase reflects a baroque frontal aesthetic.[7]

The chest of drawers illustrated in figure 12 is from the same shop as the Jackson desk-and-bookcase, and it has the same history of descent. Although the profiles of the principal inner curves of the feet on both pieces are identical, those on the chest have slightly different responds and no fillet at the bottom. The chest also has framed drawer supports, a mitered lock rail below the top, and dovetails of the same size and pitch as those on the desk-and-bookcase. The quarter-columns on both pieces have the same base and capital moldings, but the ones on the chest are not stop-fluted. Apparently Jackson was willing to pay extra for stop-fluted quarter-columns on his desk-and-bookcase, which would have been placed in a public area, but not for his chest of drawers, which may have been in a more private space of his house.[8]

The desk illustrated in figure 13 is a product of the same Tennessee shop. It has all of the distinctive structural features found on the aforementioned pieces, and its writing compartment and stop-fluted quarter-columns are virtually identical to those of the Jackson desk-and-bookcase (figs. 10, 11). The desk interiors, including the layout, the fluted document drawers, and the shape of the valances, are the same. The feet of the desk are much bolder than those on the Jackson examples, and they have different responds and a sharper radius in their principal curve. It is unusual for feet from the same shop to vary as much as in these examples, but there is no doubt that they share a common origin.

Although cherry was the primary wood favored by cabinetmakers in Middle Tennessee, the Jackson pieces and the desk are made of walnut. After his visit to Lexington, Kentucky, between the years 1807 and 1809, Fortescue Cuming noted the “immense expense” of importing mahogany into the southern backcountry and the common use of walnut and cherry in furniture. Michaux considered cherry the “most eligible substitute for mahogany” and noted that the “Wild Cherry Tree is generally preferred to the Black Walnut, whose dun complexion with time becomes nearly black.”[9]

The Jackson pieces were probably made between 1796 and 1804. Jackson arrived in Nashville in 1788 and boarded with Rachel Stockley Donelson, the widow of Colonel John Donelson, a co-founder of Nashville. In either 1790 or 1791, Jackson married the Donelsons’ daughter, Rachel, and in 1796 they moved to Hunter’s Hill, a two-story frame house about thirteen miles north of Nashville. In 1804, debts forced them to sell Hunter’s Hill, and they moved to the Hermitage (then a log house). Jackson probably purchased the desk-and-bookcase and chest of drawers while he and his wife were living at Hunter’s Hill.[10]

The desk illustrated in figure 13 descended in the family of Colonel John Donelson. In late 1779 and early 1780, he led the flotilla of boats from upper East Tennessee to Nashville as a counterpart to the overland party led by James Robertson. Although family tradition maintains that Donelson brought this desk with him on the flatboat Adventure, this history is unlikely for several reasons. First, it is doubtful that a large, expensive case piece would have been transported on a cumbersome flatboat nearly one thousand miles on winding rivers. Second, Donelson died in 1785 (having just returned to Middle Tennessee from Harrodsburg, Kentucky, where he and his family sojourned due to food shortages and Indian troubles in the Nashville area), and the desk is not listed in his estate inventory. Finally, the same cabinetmaker made two pieces of furniture for Andrew Jackson, who came to Middle Tennessee after Donelson’s death. It is far more likely that the desk belonged to Donelson’s son, John, from whom Jackson purchased Hunter’s Hill.[11]

Since both Jackson and Donelson lived ten to fifteen miles outside Nashville in northern Davidson County, the cabinetmaker they commissioned could have lived in either Davidson County or Sumner County (fig. 1). During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, both counties had comparable numbers of cabinetmakers and joiners. By the 1810s and 1820s, several cabinetmakers worked in northern Middle Tennessee; however, only a few can be documented before 1805. Although the cabinetmaker who worked for Jackson and Donelson remains anonymous, candidates include William A. Crawford, Absalom Davis, John and Thomas Deatherage, Joseph McBride, and Thomas Murray. Unfortunately, no evidence that any of these men trained or worked in the Winchester area has surfaced.[12]

Davidson County cabinetmaker William Crawford owned “One Sett of Tools for Cabinet Work” when he died in 1803. Presumably, this set comprised the “chest of tools” purchased by Absalom Davis for $101.50 at Crawford’s estate sale in 1804. Absalom Davis may be the same person who was apprenticed to Stokes County, North Carolina, house joiner Isham Vest in 1798. If so, it is highly unlikely that he made the Jackson and Donelson furniture. John and Thomas Deatherage were cabinetmakers in Nashville by 1802 when they took an apprentice in the cabinet trade. Thomas died in 1812, and shortly thereafter John moved to Kentucky. Joseph McBride of Davidson County took apprentices in 1801 and 1803. The 1815 inventory of his estate lists three work benches and “1 Compleat set of Cabinet Tools.” Davidson County Court Minutes record that Thomas Murray took apprentices in the “carpenters and joiners trade” in 1792, 1795, and 1796. Two years later, John Overton sued Murray in the Sumner County Court for failure to complete a bookcase. According to Sumner County historian Walter Durham, a man named Thomas Murray moved from Rowan County, North Carolina, to Middle Tennessee in 1785. If this individual was cabinetmaker Thomas Murray, he is an unlikely candidate for the maker of the Jackson and Donelson furniture. Other individuals recorded in published checklists of Tennessee cabinetmakers have not been included either because they cannot be documented in Middle Tennessee during the late eighteenth century, because they appear to have been house joiners rather than cabinetmakers, or because known examples of their work differ significantly from the Jackson and Donelson furniture.[13]

Furniture from the Knoxville Area of East Tennessee

When John Donelson led his flotilla down the Tennessee River on the way to the Cumberland River Valley in late 1779, he was one of the first white men to pass through the area where Knoxville is situated. After William Blount chose the site as the capital of the Southwest Territory, development of the town proceeded rapidly. By 1792, several houses were under construction, including the dwelling known today as Blount Mansion. Francis A. Ramsey built a “large handsome, two-storied stone house” outside Knoxville about 1798 (fig. 14). Moravian missionaries Abraham Steiner and Frederick de Schweinitz reported that there were about one hundred houses in Knoxville in 1799, compared to about fifty in Nashville. In 1802, Michaux found the lodging in Knoxville to be “very good” but complained that its price was “rather too high” due to the desire of the inhabitants to make money quickly. He also noted the availability of merchandise from Philadelphia, Richmond, and Baltimore but pointed out that every “article of English manufacture is sold very dear.” Although some consumer goods could be obtained elsewhere, the difficulties and expense of transportation necessitated the purchase of locally made furniture. In 1802, Knoxville had 387 inhabitants, and Knox County had 12,446. This population supported at least four cabinetmakers and a sizable number of house joiners. Four different cabinet shops produced furniture in the Delaware Valley style.[14]

A desk-and-bookcase, four corner cupboards, and a chest of drawers represent the work of one of these shops. Of all the Tennessee desk-and-bookcases known, the example illustrated in figure 15 is most like those produced in southeastern Pennsylvania. It descended in the family of Barclay McGhee who came to East Tennessee from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1787 and who is listed as a taxpayer in Blount County (located south of Knox County) in 1801. The writing compartment has double-ogee-blocked drawers that are similar to those of the Philadelphia desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 5, although the Tennessee cabinetmaker used a single long drawer in the lower tier (fig. 16). The prospect door on the McGhee desk-and-bookcase is significantly different from those on other Tennessee desks. It has an arched head and a full architrave with a central key block and fluted pilasters with classical base and capital moldings. Much in the high baroque style, the cabinetmaker created a small architectural doorway that provides a “prospect,” or view, when open. By contrast, his interpretation of the “skolloped” doors found on many Delaware Valley bookcases is visually disturbing because he used equal-sized panels rather than a single panel or a small panel over a larger one. Drawers that function as fallboard supports are another Delaware Valley detail used by this tradesman. Only one other Tennessee desk with this feature is known.[15]

The relationship of this artisan’s work to the Winchester school is apparent in the arched, stop-fluted quarter-columns and chamfers of the McGhee desk-and-bookcase (figs. 17, 18). Although the combination of these corner treatments is unusual, it relates to the superimposition of orders in classical architecture (the higher or more complex the order, the higher the level). The scale of the cornice is also architectural, though it resembles cornices on cupboards made by house joiners. Astragal-scalloped friezes, like the one on the McGhee desk-and-bookcase, are rare in Shenandoah Valley furniture, but they occur frequently on cupboards attributed to the Ralph family of Kent County, Delaware, which typically have astragal-scalloped architraves as well. The Tennessee cabinetmaker used the same astragal scalloping on the applied panel of the fallboard. This panel is reminiscent of those on bookcase doors and tall clock plinths made in rural areas of southeastern Pennsylvania and the southern backcountry.[16]

The corner cupboard illustrated in figure 19 is from the same shop that produced the McGhee desk-and-bookcase. Although the heavy cornice molding and the low scrolled pediment give the cupboard a baroque appearance (figs. 20, 21), it is probably contemporary with the aforementioned piece. In all likelihood, the large size of the cupboard necessitated flattening the curve of the scroll to accommodate the breadth without a proportional increase in overall height. Concern with height may also explain why the cupboard never had feet. The shape of the arched doors may be associated with Germanic furniture made in southeastern Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley.[17]

The carving on the corner cupboard (fig. 21) ties it to the Winchester school and, in particular, to the shop that produced the Lupton desk-and-bookcase (fig. 2). Although the rosettes on the Tennessee piece are not as realistic as their Winchester counterparts, both sets have hollowed petals and veining flutes cut with a small, U-shaped gouge (referred to as a veiner). The veining on the corner cupboard most closely resembles that on the leaf appliqués of a high chest that Lupton purchased from the same Winchester shop that made his desk-and-bookcase (figs. 22, 23). The shell pendant below the plinth of the corner cupboard also has fluted gadrooning like the shell on the knee of the high chest (fig. 24), although, again, the carving is more naive on the Tennessee piece.

Several construction and carving details indicate that the McGhee desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) and the corner cupboards illustrated in figures 19 and 25 are from the same shop and possibly by the same hand. The backs of the cupboard drawers are reverse-pinned to the sides (the dovetail pins are cut in the sides and show at the back rather than at the sides), a distinctive feature that furniture historian Benno Forman ascribed to Germanic cabinetmaking traditions. This joinery, which actually weakens the drawer, seems to contradict the overbuilt nature of many German-influenced pieces, however. The cupboards and desk-and-bookcase have cock beading that is pinned to the case around the doors but applied directly to the drawer fronts. The McGhee desk-and-bookcase and the cupboard illustrated in figure 25 have the same cornice moldings and astragal-scalloped frieze, and all three pieces have sawn and applied dentil molding. The corner cupboards and desk-and-bookcase also have quarter-columns with the same base and capital moldings, and the pieces illustrated in figures 15 and 25 have arched stop-fluting (figs. 17, 26). Arched stop-fluting differentiates these objects from Nashville-school furniture, which has level stop-fluting. Two other corner cupboards from this same Knox County shop are known, and both are similar in form and decoration to the example illustrated in figure 25.[18]

A chest of drawers from the same shop (fig. 27) shares a number of details with the McGhee desk-and-bookcase and the corner cupboards illustrated in figures 19 and 25: reverse-pinned drawer backs, quarter-column base and capital turnings, applied frieze with astragal-scalloping, and cornice construction (see captions for figs. 25, 27). Like the Jackson and Donelson furniture, the chest and the McGhee desk-and-bookcase have framed drawer supports, but they are pinned into dadoes in the case sides. The front feet on the chest are original and suggest how the original feet of the McGhee desk-and-bookcase and the cupboard shown in figure 25 may have looked.[19]

The furniture from this Knoxville shop is as difficult to date as the Nashville and Winchester work discussed earlier. Stylistically, the McGhee desk-and-bookcase and the corner cupboard illustrated in figure 19 could have been made as early as the 1760s in southeastern Pennsylvania or as early as the mid-1770s in Frederick County, Virginia, but given the late settlement of Knox County, they probably date from the last decade of the eighteenth century. Both pieces show how styles persisted in the backcountry long after they were fashionable in other areas. The cupboard illustrated in figure 25 and the chest of drawers (fig. 27) were made between 1795 and 1810.

Astragal-scalloped friezes appear on two later pieces of East Tennessee furniture. A tall chest (at the East Tennessee Historical Society) with a Greene County provenance, inlaid chamfered corners, and ogee feet with spurred responds is slightly later than the chest illustrated in figure 27 and may represent the work of a cabinetmaker who trained in Knoxville, then moved to Greene County. Another tall chest with French feet and a shaped skirt is the latest example with this frieze design.[20]

Only one piece of furniture survives from each of the three remaining Knoxville shops that produced furniture in the Delaware Valley style. In the past, all three pieces have been attributed to Thomas Hope, who appears to have been a house joiner rather than a cabinetmaker. Hope emigrated from England to Charleston, South Carolina, around 1785 and moved to Knoxville during the mid-1790s. Little is known about his work in Charleston other than his involvement in the construction of Ralph Izard’s house. After moving to Knoxville, Hope advertised for an apprentice “to learn the whole art of house carpenter’s and joiner’s business.” In 1797, he offered a reward for house joiner’s tools stolen from his “carpenter’s work shop” and in 1812 identified himself as a house joiner in a registry of British aliens. Hope is credited with work on a number of houses located in or near Knoxville, including Ramsey House (fig. 14). In 1806, Charles Coffin wrote that he “Stopped for the night at Mr. John Kain’s where I conversed with Mr. Hope, his house carpenter, who did work on Colonel McClung’s house, built Mr. Izzard’s house in Charleston, South Carolina and is accounted one of the best workmen in the country. He showed an excellent book of architecture.”[21]

The only references to Hope selling furniture are in the Waste Book of David Henley, an agent of the War Department and the superintendent of Indian Affairs. Henley paid Hope $30.00 “for a double wallnut desk made for Silas Dinsmore,” $25.00 “for a desk,” and $6.00 “for a table and board to write at.” Although the costs of the desks suggest that they were made by a cabinetmaker rather than a house joiner, none of these entries specify that Hope made the furniture. Like Charleston house joiner Richard Moncrieff, he may have simply functioned as a supplier.[22]

The notion that Hope was a cabinetmaker probably originated with the autobiography of J. G. M. Ramsey, whose father built Ramsey House. Ramsey described Hope as an architect, cabinetmaker, and upholsterer and stated that he had made his father’s “tall and elegant secretary” and “a massive bureau.” His description of the secretary stretches the limits of imagination in relation to the furniture produced in Knoxville during the early nineteenth century:

In construction he used . . . some American woods he had never seen before (sumac was one of them). As may well be excused in an English mechanic, he put . . . on the top of Colonel Ramsey’s secretary the English lions and the unicorn. Colonel Ramsey refused to receive the work till he had placed the American eagles in suitable propinquity to and above the armorials of the British royalty.

Unfortunately, Dr. Ramsey’s reminiscences have resulted in the misattribution of much early Knoxville furniture to Hope, including an architectural cupboard, a “compting house desk,” a neoclassical secretary-and-bookcase, and the pieces illustrated in figures 28, 30, and 33.[23]

Hope died in 1820 while working on Rotherwood in Boatyard (Kingsport), Tennessee. The meager possessions listed in his inventory included a “box of carpenters tools.” Although Hope consistently described himself as a carpenter and joiner, he apparently possessed carving skills. The trusses under the cornice soffits of Ramsey House are attributed to him. In an 1820 letter to his wife, Hope expressed his desire “to set up to carve next Monday.”[24]

Oral tradition maintains that Hope made the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28. Thomas W. Humes, the son of the original owner, left it to the Lawson-McGhee Library at his death in the late nineteenth century. Humes was the half brother of J. G. M. Ramsey, and it is possible that the original attribution was made by him. Even if Hope was a cabinetmaker, it is unlikely that he would have made rococo forms such as this desk-and-bookcase. By the time he immigrated to America, neoclassicism was the rage in both England and Charleston. More importantly, the desk-and-bookcase is clearly associated with the Winchester school.[25]

There are both structural and decorative similarities between the Humes desk-and-bookcase (fig. 28) and the Lupton example (fig. 2). Although the tympanum of the Winchester desk-and-bookcase is taller, both pieces have similar pediment and tympanum profiles (the openings of the tympana merge with the cornice moldings in the same place on both pieces) and flat, two-paneled doors. The doors of the Knoxville piece have flush panels, unpinned joints, and applied cock beading, whereas the doors on the Lupton bookcase have recessed panels, pinned joints, and beaded stiles and rails. Both desk-and-bookcases have full-depth dustboards. The dustboards on the Humes example are one-half the height of the drawer rails, and laths that run the full depth of the case fill the lower halves of the dadoes. The Lupton desk-and-bookcase has three-quarter-height dustboards and wedges rather than lath.

Despite these similarities, the distance separating Winchester and East Tennessee is apparent in the regional adaptations of form, structure, and decoration made by Knoxville cabinetmakers. The rosettes, leaves, and shell on the Humes desk-and-bookcase (figs. 28, 29) are flat and less competently carved than those on the Winchester furniture (see figs. 2, 3, 23). Instead of having quarter-columns with arched stop-fluting on both the upper and lower cases, like the Lupton desk-and-bookcase, the Knoxville example has quarter-columns solely on the lower case, and they are not stop-fluted. The flutes on the Winchester piece return, whereas those on the Humes piece do not. Both desks have fluted document drawers flanking the prospect door, but the door on the Knoxville desk has a cove molding on either side and a small concealed drawer above rather than a full-coved surround like the door on the Winchester example. Philadelphia and Winchester desks typically have pigeonholes above the drawers, but on the Humes desk-and-bookcase this arrangement is reversed.[26]

The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 30 descended in the family of Judge David Campbell, an early Knoxville resident and a contemporary of Governor Blount. Because of its visual similarity to the Humes desk-and-bookcase (fig. 28), the Campbell example has also been attributed to Thomas Hope; however, it clearly represents the work of a second Knoxville cabinetmaker who trained in the Winchester area. The pediment of the Campbell desk-and-bookcase is more closely based on Winchester prototypes than the pediment of the Humes piece (figs. 3, 29, 31). The tympanum of the Campbell bookcase is the same height as that of the Lupton example, and it has a straight astragal molding rather than a swagged one as on the Winchester piece. The point where the tympanum opening merges with the crown molding on the Campbell example is slightly higher than on the Lupton desk-and-bookcase and high chest, although the geometry of the tympanum curves is similar. The lunetted astragals on the doors of the Campbell desk-and-bookcase are repeated on another desk-and-bookcase from the same shop that produced the Lupton furniture. The carving on the Campbell piece is also closer to Winchester work than other carving on Knoxville furniture. The leaves on the shell below the plinth is an unusual detail found on furniture from the shop that made the Lupton pieces. The carver of the Campbell desk-and-bookcase used his veiner extensively (even beneath the petals on the rosettes), as did the carver of the Knoxville corner cupboard illustrated in figure 19.[27]

The desk interior and the feet of the Campbell desk-and-bookcase diverge from Delaware Valley and Winchester styles. Rather than having document drawers on either side of the prospect door, the Campbell desk-and-bookcase has carved terms with horizontal flutes, paneled plinths, and Egyptian papyrus-form capitals (fig. 32). The pigeonholes have delicately fluted brackets that spring from gothic clustered columns with leafy capitals. These details, which have no known parallel in Knoxville work, suggest that the maker or owner may have had access to architectural design books. Although the base molding is replaced, the feet are mostly intact. Their long, scrolled responds and ogee elements near the floor lend an earlier but more vernacular appearance to the piece.[28]

The Campbell desk-and-bookcase has several unusual construction details. The bookcase has vertical tongue-and-grooved backboards that are nailed into rabbets in the sides, whereas the desk has a three-panel back. The drawer construction is unlike that of any object illustrated here. Instead of fitting into dadoes in the drawer fronts and sides, all of the drawer bottoms are dadoed into the drawer fronts and nailed into rabbets in the drawer sides. Applied strips fill the voids between the drawer bottoms and sides and serve as runners. The Campbell desk-and-bookcase also differs from the aforementioned Tennessee pieces in having full-depth, full-bottom dustboards.

The tall chest illustrated in figure 33 is a product of the fourth Knoxville cabinetmaker from the Winchester school. Like the Lupton desk-and-bookcase (fig. 2) and several of the case pieces from the Nashville area (see figs. 9, 12, 13), the chest has ogee feet with filleted, spurred responds. Its arched, stop-fluted quarter-columns relate to those on the McGhee desk-and-bookcase (figs. 15, 17) and the corner cupboard illustrated in figure 25, as well as to furniture from the Winchester school (see figs. 2, 6, 22). The chest also has a full-bottom, full-depth dustboard that fits into a half-dovetail dado in the case sides beneath the upper three drawers. The support system for the lower drawers consists solely of the drawer rail, which is half-dovetailed to the case sides, and the drawer supports, which are tenoned to the rail and dadoed to the case sides. The Nashville and other Knoxville examples feature either dustboards or fully framed drawer support systems. Perhaps because this tall chest contains neither of these support systems, the drawer rails are exceptionally deep (five inches). Like the Humes and Campbell desk-and-bookcases (figs. 28, 30), this chest was probably made between 1795 and 1810.[29]

Knoxville records from this period reveal the names of three men who were cabinetmakers and two individuals who may have been. As was the case in Davidson and Sumner Counties, there is no evidence that any of these men trained or worked in Winchester, except, of course, for the furniture itself. Given the existence of four shops producing Winchester-style furniture in Knox County, a high percentage of the cabinetmakers mentioned in Knoxville records must have trained or worked near that Virginia town.

Knoxville cabinetmaker Terrence McAffry immigrated to America from Ireland in 1796. He may have arrived in Philadelphia and traveled down the Shenandoah Valley to Winchester. If so, he may have met his wife, Martha Clopton, there. (A George Clopton was a cabinetmaker in Frederick County, Virginia, during this period.) In Knoxville, McAffry worked as both a cabinetmaker and house joiner. Thomas Hope’s copy of The Builder’s Golden Rule has an 1801 inscription stating that “R. Morrow, Mr. McClure, Mr. McCafry, Mr. Booth, and T. Hope” had agreed on prices to be charged for house joinery work. McAffry took two apprentices in the cabinetmaking trade in 1803. In the April 21, 1810, issue of Wilson’s Knoxville Gazette, he advertised that his “workmen are equal to any in this state, and his work will be executed in the neatest and most fashionable manner. He will take in exchange for furniture corn, flour, cotton, tow linnen, whiskey and pork.” According to the 1820 Manufacturers’ Census, three men worked in his shop, producing sideboards, bureaus (including examples with mahogany fronts), tables, and bedsteads. McAffry worked until his death in 1830.[30]

Although the 1820 Manufacturers’ Census is the only known document that specifies cabinetmaker James Bray’s profession, he appears to have been working in the Knoxville area by 1797, when he married Rachel Smith. In 1802, his name appears on the tax list for Knox County. According to the Manufacturers’ Census, he had four workmen who produced secretaries, “charry presses,” circular- and straight-front bureaus, tables, and bedsteads.[31]

The 1819 inventory of Moses Crawford included “One set of cabinet makers tools, a few carpenters’ tools and some plain stocks . . . several pieces of dry Beach fit for plain stocks, one work bench with a screw and Iron vice, [and] one hundred and ninety one feet of walnut plank.” Crawford was in Knoxville by 1806 when his name appears on a Knox County tax list.[32]

Considering the number of Knoxville pieces that have survived from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the shop that produced the objects illustrated in figures 15, 19, 25, and 27 must have been a sizable business in operation for several years. Both McAffry and Bray were masters of such shops. Although Crawford may have practiced the cabinetmaking trade for a number of years, he apparently was the only man working in his shop since only one work bench was listed in his estate inventory.

Two other Knoxville men may have been cabinetmakers at the turn of the century. The 1802 inventory and estate sale of Henry Baker listed a turning lathe, a glue pot, mountings for a bureau and a desk, and a number of tools, including a keyhole saw; however, some items normally found in cabinetmakers’ inventories are not listed, including a work bench, materials, a dovetail saw, table planes, and other trade-specific tools. On March 27, 1821, the Knoxville Register reported that “An Estate worth notice” had been left in Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, by John Garrison, a cabinetmaker and carpenter, who about sixteen years before had been a resident of Knoxville. This man could be the same John Garrison whose name appeared on the 1801 tax list for Blount County. Some men who have been included on earlier checklists of Tennessee cabinetmakers have been omitted because their probate inventories indicate that they were house joiners only.[33]

Other Delaware Valley and Shenandoah Valley Influences

Nashville and Knoxville were not the only areas in Tennessee where cabinetmakers made furniture that resembled Shenandoah Valley work. A distinctive variation of the Delaware Valley style developed in Shenandoah County and Rockingham County, Virginia, both located south of Frederick County. Two shops in Greeneville, Tennessee, produced a sizable body of furniture that is more closely related to the styles associated with these two counties than with Frederick County. The range of style and decoration and changing methods of construction demonstrate the versatility and longevity of these Virginia and Tennessee shop traditions.[34]

The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 34 has a Delaware Valley–style interior, with a prospect door flanked by two document drawers and pigeonholes surmounting a two-tier drawer arrangement. The deep valances over the pigeonholes are reminiscent of the valances on the Nashville desk-and-bookcase and desk illustrated in figures 9 and 13. The corner cupboard illustrated in figure 35 is from another Greeneville shop that produced furniture in the Delaware Valley and Shenandoah Valley styles. The cross-pollination of styles and decoration in the small community of Greeneville is evident in the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 36. This desk-and-bookcase is from the same shop and has virtually the same interior as the example illustrated in figure 34; however, its inlaid rope-and-tassel ornament is a distinctive regional variant of the carved rope and tassel on the tympanum of the Greenville corner cupboard (fig. 35). On the desk-and-bookcase shown in figure 36, the inlaid rope and tassel is accompanied by upturned bellflowers, which are a hallmark of later Greene County work.

The furniture produced in Greeneville ranged from relatively plain objects (fig. 34) to more ornamental pieces with idiosyncratic carving or inlay (figs. 35, 36). In part, this variation can be explained by the history of the town. Greeneville played an important role during the early years of settlement in East Tennessee. In 1772, Jacob Brown and one or two families from North Carolina settled on the northern bank of the Nolichucky River in Greene County. Brown’s settlement (on lands leased and subsequently purchased from the Cherokee Nation) continued to grow during the 1770s and early 1780s. Frustrated over the lack of government in upper East Tennessee, the residents of the area formed the State of Franklin in 1785. Greeneville was established in 1786 as the capital of the new state. With the formation of the Southwest Territory in 1789, the disestablishment of the State of Franklin, and the choice of Knoxville as the new seat of government, Greeneville’s importance waned. According to Michaux, there were no more than forty houses in Greeneville in 1802, all of which were “built of squared beams, arranged like the trunks of trees of which log houses are formed.” Some early residents remained, however, and cabinetmakers continued to produce furniture in both plain and distinctively regional styles.[35]

Summary

At least four Knoxville shops produced a sizable body of furniture in the Winchester style; whereas only one Nashville shop worked in this style, and its surviving output consists of only three pieces. This difference is a reflection of the settlement patterns of the two areas and the cultural background of the cabinetmakers and their patrons. Folklorist Henry Glassie has traced patterns of cultural influence throughout the eastern United States and has noted that the material culture of the southern backcountry is a product of the confluence of English cultural traditions from the Chesapeake region and Germanic, Scots-Irish, and English traditions from Pennsylvania. According to Glassie, Pennsylvania influences were strongest in the Shenandoah Valley and weakest in the Tennessee Valley and the Bluegrass sections of Tennessee and Kentucky. Although many settlers in East Tennessee came from Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley, Middle Tennessee attracted a larger percentage of settlers from the coastal and piedmont regions of Virginia and the Carolinas. The provenances of the Knoxville and Nashville area furniture discussed in this article confirm these patterns of settlement and cultural influence.[36]

The settlement of northern Middle Tennessee and the histories of the families who owned the furniture discussed in this article suggest that most of the Nashville pieces date from between 1790 and 1805. Some Middle Tennesseans, like their counterparts in Frederick County, Virginia, and East Tennessee, preferred, or at least purchased, furniture that would have been considered old-fashioned along most of the eastern seaboard. Andrew Jackson lived in the piedmont regions of North Carolina and South Carolina before moving to Tennessee. John Donelson, who was born in Brunswick County, Virginia, moved to Middle Tennessee with his wife, parents, and siblings in 1780. Both of these men spent most of their adult lives in the southern backcountry and may have been unaware of, or indifferent to, the prevailing coastal fashions.[37]

Not all of the furniture made in northern Middle Tennessee during this period was as retardataire. James Winchester and Daniel Smith provide striking contrasts to Jackson and Donelson. Winchester came to Middle Tennessee in 1785 from Westminster, Maryland, about forty miles northwest of Baltimore, after having spent time during the Revolutionary War in Annapolis and Charleston. He brought his nephew William Winchester to Sumner County to assist in the building of his house, Cragfont. William took an apprentice in the cabinetmaking trade in 1802, and according to family tradition made his uncle several pieces of furniture in the neoclassical style—a sideboard, a secretary, a pair of card tables, a pembroke table, and a dining table—before returning to Maryland.[38]

Daniel Smith was born in eastern Virginia and educated at the College of William and Mary, but he spent most of his adult life in the backcountry. In 1783, he moved from southwest Virginia to Tennessee. Unlike Jackson and Donelson, Smith evidently preferred neoclassical furniture. During the 1790s, Smith’s nephews, Peter and Smith Hansborough, moved from Philadelphia to Sumner County to assist in the construction of Rock Castle. Like William Winchester, the Hansborough brothers were apparently cabinetmakers and house joiners. A sugar chest and a two-drawer chest (which has been adapted from its original form) attributed to them descended in Daniel Smith’s family. Smith also owned a secretary that is markedly similar to the example owned by James Winchester and may be by William Winchester or his apprentice.[39]

In contrast, the Knoxville pieces with provenances descended in families who migrated to East Tennessee from Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley, and Ireland. The McGhees, who owned the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 15, were from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The Andersons and McCampbells, who owned the corner cupboard illustrated in figure 19, were from Rockingham County, Virginia. The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 30 descended in the family of Judge David Campbell, who was born in Augusta County, Virginia, and lived in Washington County, Virginia, before moving to East Tennessee. Thomas Humes, the original owner of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28, was born in Ireland. Like Jackson and Donelson, these owners may have been unaware of the fashions on the coast and therefore chose furniture made in a style with which they were familiar. The dominant stylistic influences in the Knoxville area emanated from the Delaware Valley and Shenandoah Valley because a majority of the town’s cabinetmakers evidently apprenticed or worked as journeymen in the Winchester area.[40]

The convergence of patrons and cabinetmakers with similar cultural backgrounds was particularly strong in Knoxville. In Nashville, however, the cultural composition of the community in general and of the cabinetmakers in particular was different. Although at least one Nashville cabinetmaker produced furniture similar to that made in Knoxville, the broader range of tastes in Nashville was a direct result of settlement patterns in Middle Tennessee. As in the study of most regional furniture, an accurate evaluation of stylistic preferences and characteristics depends heavily upon a significant sample of objects. Recognition of the full extent of Delaware Valley and Winchester influence in Tennessee may bring to light additional furniture that has been misattributed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author expresses her gratitude to the following individuals whose assistance has been invaluable: Mary Jo Case, Steve Cotham, Dick Doughty, Jim Hoobler, Ron Hurst, Marsha Mullin, Sumpter Priddy, Jonathan Prown, Susan Shames, and, most of all, John Bivins.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (hereinafter cited as CWF) has four other pieces from the same shop that made the desk-and-bookcase shown in figure 2: two high chests (acc. 1973–206, 1973–325), a card table (acc. 1987–725), and a corner cupboard (acc. 1973–197). One of the high chests is illustrated in figure 22. With the exception of the corner cupboard, all of these pieces were owned by David Lupton, who built Cherry Row on Apple Pie Ridge outside Winchester in 1794. Other furniture from the same shop is recorded in the files at CWF and the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereinafter cited as MESDA). See, for example, MESDA research files S-9460, S-11186, and S-13543. Local interpretations of all the Delaware Valley details discussed above occur on furniture from other regions of the southern backcountry. For a discussion of Delaware Valley influences on Piedmont North Carolina furniture, see John Bivins, “A Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker: The Development of Regional Style,” Antiques 103, no. 5 (May 1973): 968–73; Carolyn Weekley, “James Gheen, Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 103, no. 5 (May 1973): 940–44; Luke Beckerdite, “City Meets Country: The Work of Peter Eddleman, Cabinetmaker,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 5, no. 2 (November 1979): 59–73; and Beckerdite, “The Development of Regional Style in the Catawba River Valley: A Further Look,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 7, no. 2 (November 1981): 31–48. I thank Alan Miller for the information on quarter-columns on Delaware Valley furniture. For more on Philadelphia furniture, see William MacPherson Hornor, Blue Book of Philadelphia Furniture (1935; reprint, Alexandria, Va.: Highland House Publishers, 1988). Stop-fluted quarter-columns are common on Newport and Newport-influenced furniture (see Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards [Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984], passim). John Shearer of Martinsburg, West Virginia, used swagged rather than arched stop-fluting (MESDA research file S-11732).

Each additional option added to the cost of a piece. According to Benjamin Lehman, quarter-columns added ten shillings to the cost of a desk (Gillingham, “Benjamin Lehman,” p. 290).

James McCague, The Cumberland (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973), pp. 58–64. Paul Clements, A Past Remembered: A Collection of AnteBellum Houses in Davidson County, 2 vols. (Nashville, Tenn.: Clearview Press, 1987), 1:228. Caldwell, Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, p. 7. Arnow, Seedtime on the Cumberland, p. 240. Inventory and Division of the Estate of John Donelson, Davidson County Wills and Inventories, July 1790 and April 1791, bk. 1, pp. 166–67, 176, 196–201.

Goodspeed’s History of Hamilton, Knox, and Shelby Counties of Tennessee (1887; reprint ed., Nashville, Tenn.: Charles and Randy Elder Booksellers, 1974), pp. 798–99. Despite historian Mary Rothrock’s claim, Blount Mansion does not appear to be “the first frame house built west of the mountains.” Mary U. Rothrock, ed., The French Broad–Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1946), p. 32. Patrick, Architecture in Tennessee, pp. 69–71. Charles Coffin Journal, February 7, 1801, Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection, Lawson-McGhee Library, Knoxville, as quoted in Patrick, Architecture in Tennessee, p. 3. “Report of the Journey of the Brethren Abraham Steiner and Frederick C. De Schweinitz to the Cherokees and the Cumberland Settlements,” in Williams, comp., Early Travels in the Tennessee Country, pp. 454, 508. Michaux, Travels, pp. 272–74, 280. Deaderick, ed., Heart of the Valley, pp. 70, 74.

Benno M. Forman, “German Influences in Pennsylvania Furniture,” in Arts of the Pennsylvania Germans, edited by Scott M. Swank (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), p. 123. One of these cupboards (private collection) was nearly identical in form and decoration to figure 12, although it is slightly smaller and has quarter-column flutes that extend from the capitals to the bases. On all of the pieces with quarter-columns illustrated in this article, the flutes stop approximately 3/4" short of capitals and bases. The other cupboard (private collection) has a wide medial molding and no quarter-columns or drawers. A corner cupboard that may be related to this group is illustrated in Namuni Hale Young, Art and Furniture of East Tennessee (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1997), p. 29, fig. 51.

On June 2, 1788, the State Gazette of South Carolina reported that Hope led the city’s architects in a procession in Charleston. Although the city directory for 1790 lists Hope as a cabinetmaker at 15 Friend Street, furniture historian Brad Rauschenburg speculates that the description of Hope’s trade may be inaccurate since Friend Street was a center for carpenters, and no other cabinetmakers are listed on that street. Evidence of Hope’s work for Izard lies solely in the naming of one of his children for Ralph Izard and an entry in the journal of Charles Coffin of Knoxville regarding a conversation he had with Hope. Kenneth Scott, comp., British Aliens in the United States During the War of 1812 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1979). Beatrice St. Julien Ravenal, Architects of Charleston (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992), pp. 88–89. Susan Douglas Tate, “Thomas Hope of Tennessee, c. 1757–1820, House Carpenter and Joiner” (master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, 1972), pp. 35–37, 42. Bradford L. Rauschenberg, Charleston Cabinetmakers, 1680–1820 (Winston-Salem, N.C.: MESDA, forthcoming). Knoxville Gazette, November 14, 1796, and March 20, 1797, as cited in Tate, “Thomas Hope,” pp. 46–47. Hope’s involvement in the construction of Ramsey House is based upon an autobiography written by J. G. M. Ramsey (son of Frances Ramsey of Ramsey House) in the late nineteenth century. Tate, “Thomas Hope,” pp. 82–86. The book of architecture referred to by Coffin is probably William Pain’s The Builder’s Golden Rule, or the Youth’s Sure Guide (1782). Hope’s copy of this book, minus its cover, is in the McClung Historical Collection, Lawson-McGhee Library, Knoxville. Journal of Charles Coffin, 1775–1853, as cited in Tate, “Thomas Hope,” pp. 93, 96.

Apparently, the bookcase originally overhung the back of the desk by about 1 1/2". The bookcase now sits on top of the base molding, which is approximately 1 1/4" deep. A positioning rail attached to the leading edge of the bottom of the bookcase (behind the doors) is missing. Holes in the top of the desk indicate that this rail was screwed from below to secure the bookcase. The dovetails of the bookcase and those of the drawers of the lower case are similar.

Rothrock, French Broad–Holston Country, pp. 389–90.