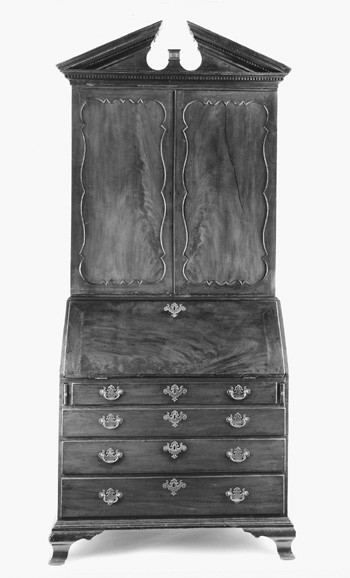

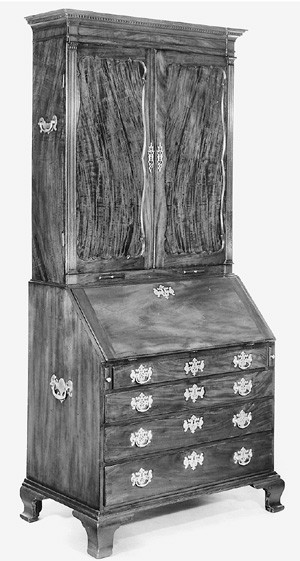

Desk-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1775–1785. Mahogany with white pine. H. 97", W. 42", D. 26". (Courtesy, Rhode Island Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

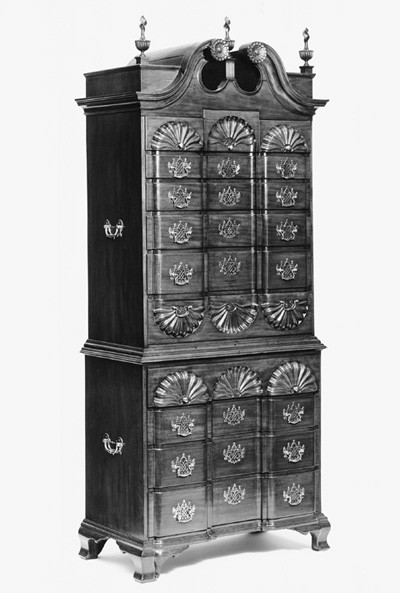

Chest-on-chest, Providence, Rhode Island, 1775–1785. Mahogany with chestnut and white pine. H. 86 3/4", W. 41 1/2", D. 21 3/4". (Kaufman American Collection; photo, Dirk Bakker.) John Brown’s daughters inscribed the piece “1785/Abby Brown/1786/Sally Brown.”

Chest-on-chest, Providence, Rhode Island, 1775–1790. Mahogany with chestnut and white pine. H. 91", W. 40 3/8", D. 22". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

John Carlisle, Jr., desk, Providence, Rhode Island, 1760–1785. Mahogany with chestnut, white pine, and cedar. H. 43 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest-on-chest, Providence, Rhode Island, 1785–1800. Mahogany with white pine. H. 92 1/2", W. 42 3/4", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Moselle Taylor Meals.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1790. Mahogany with chestnut, white pine, yellow pine, and cherry. H. 107 1/4", W. 44 2/3", D. 25 1/5". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Joseph Brown house, 50 South Main Street, Providence, Rhode Island, 1773–1774. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

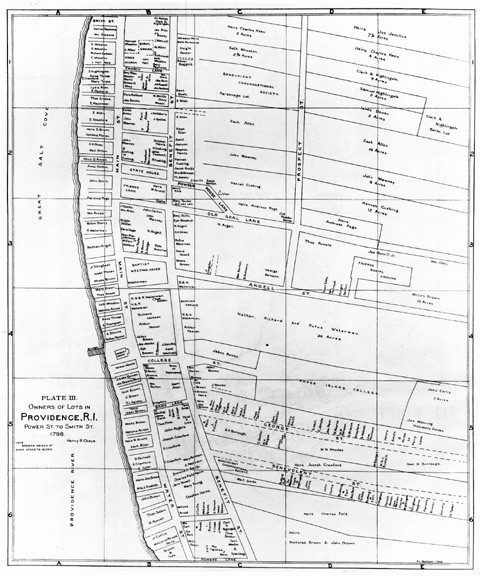

Owners of Lots in Providence from Power Street to Smith Street, taken from Henry R. Chace, Owners and Occupants of the Lots, Houses, and Shops in the Town of Providence Rhode Island in 1798 (Providence: Livermore & Knight, 1914), pl. 3. (Courtesy, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Museum Library.)

Chest-on-chest, Newport, Rhode Island, 1762–1775. Mahogany with chestnut, cherry, and pine. H. 82 1/2", W. 42", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock with movement by George Sommersall (London), Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Mahogany with white pine. H. 84 1/2", W. 20 1/4", D. 11 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock with movement by Seril Dodge, Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Mahogany with white pine and maple. H. 85 1/2", W. 21", D. 10 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1769–1775. Mahogany with chestnut and white pine. H. 86", W. 39 1/2", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Second-floor hallway of the Nicholas Brown, Jr., house, 357 Benefit Street, Providence, Rhode Island, ca. 1870. (Photograph, courtesy, John Nicholas Brown Center for the Study of American Civilization, Brown University.)

Secretary-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1795–1810. Mahogany with chestnut, cedar, and white pine. H. 110", W. 47", D. 22 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Secretary-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1795–1810. Mahogany with cherry and white pine. H. 100 1/4", W. 48", D. 43 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

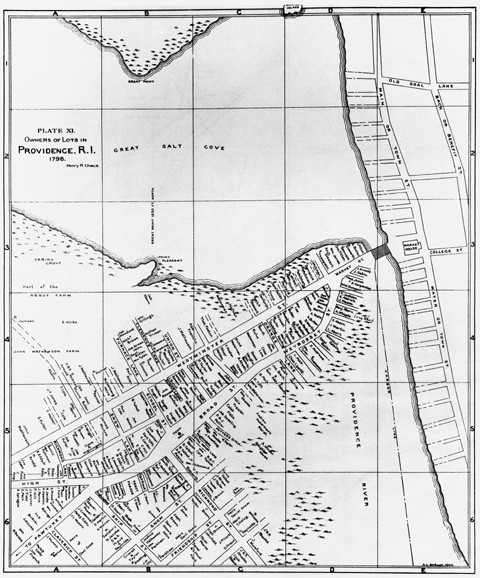

Owners of Lots in Providence, taken from Henry R. Chace, Owners and Occupants of the Lots, Houses, and Shops in the Town of Providence Rhode Island in 1798 , pl. 11. (Courtesy, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Museum Library.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Cherry with chestnut and white pine. H. 92 3/8", W. 38 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The use of chestnut as a secondary wood is common in Rhode Island furniture but relatively rare in Massachusetts work.

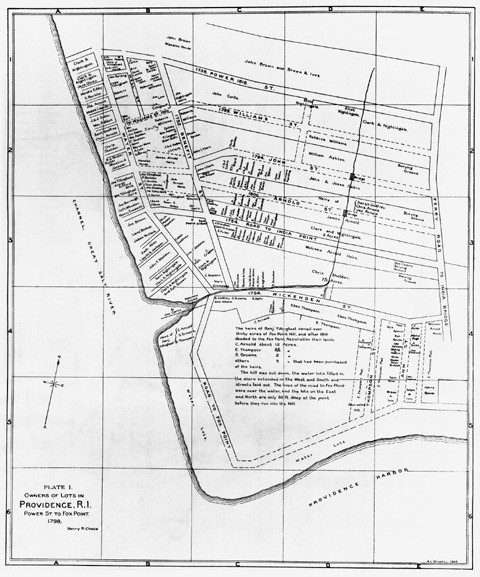

Owners of Lots in Providence from Power Street to Fox Point, taken from Henry R. Chace, Owners and Occupants of the Lots, Houses, and Shops in the Town of Providence Rhode Island in 1798, pl. 1. (Courtesy, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Museum Library.)

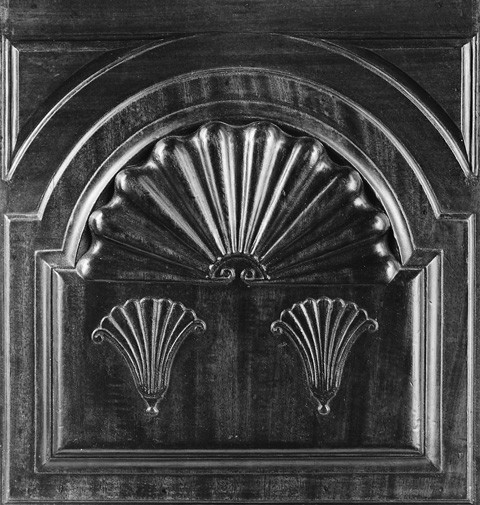

Detail of a convex shell on a Newport chest of drawers. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

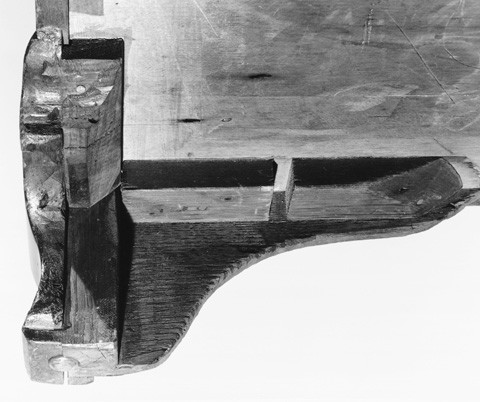

Detail of a convex shell on the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

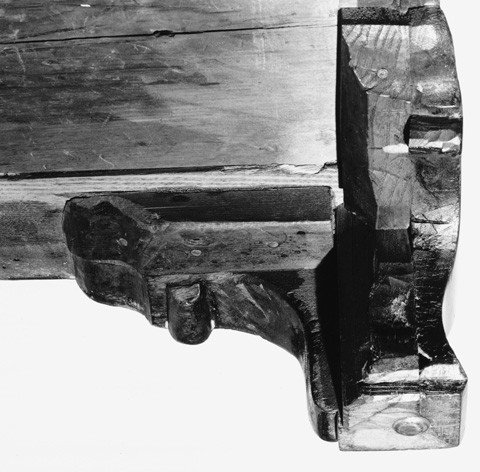

Detail of a foot on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a foot on the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail showing the front foot construction of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail showing the rear foot construction of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

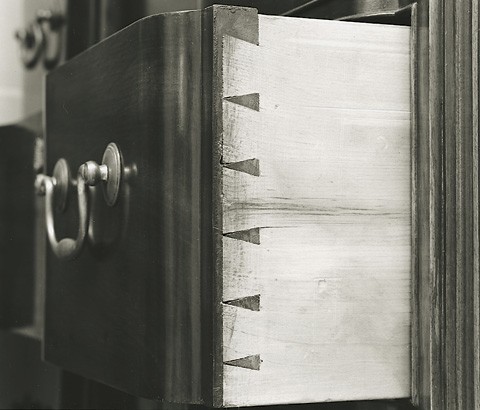

Detail of the dovetails on a drawer from a Newport chest of drawers. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail showing the saw kerf on a drawer from the chest-on-chest illustrated in

fig. 3.

Detail of the interior of the desk illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of miter joints on the doors of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 14. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest, attributed to Grindal Rawson, Providence, Rhode Island, 1750–1770. Cherry with chestnut and pine. H. 72", W. 38 3/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum Library.)

Detail of the knee carving on the high chest illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail of the carving on the plinth of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock with movement by Edward Spalding, Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Mahogany with pine and chestnut. H. 96", W. 19", D. 12". (Private collection; photo Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock with movement by Edward Spalding, Providence, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, John S. Walton.)

Detail of a rosette on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a rosette on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a rosette on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a through-tenon used in the construction of the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a through-tenon used in the construction of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of one of the fallboard supports and blocking of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the bookcase section of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk section of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a door on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the joint between the base molding and bottom board of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The sides of the dovetails are not as flared as those on Massachusetts examples.

Chest of drawers, Newport or Providence, Rhode Island, 1755–1785. Mahogany with yellow poplar, white pine, red cedar, and chestnut. H. 32 2/5", W. 36 4/5", D. 21 1/5". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Detail of a foot on the desk illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the joint between the base molding and bottom board of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a shell on a drawer of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

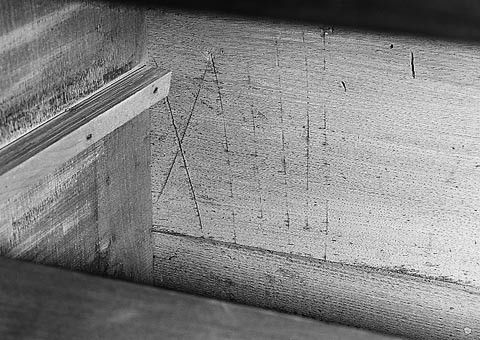

Detail of the score marks on an interior backboard of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 2. (Courtesy, Kaufman Americana Collection; Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These marks were probably made by a lumberman grading or sorting the planks.

Chalk sketch of a side chair drawn on a drawer bottom of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

Chalk sketch of an urn finial drawn on the bottom board of the lower case of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

Clothespress, Philadelphia, 1780–1790. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 100", W. 47 3/4", D. 24 1/2". (Private collection, on loan to the Rhode Island Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the dovetails on a drawer of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 5.

Detail of the dovetails on a drawer of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3.

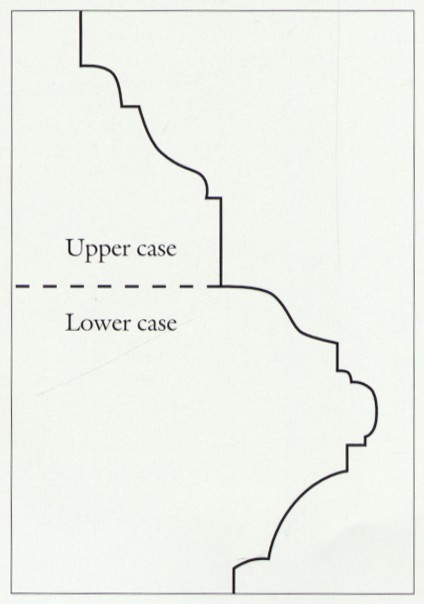

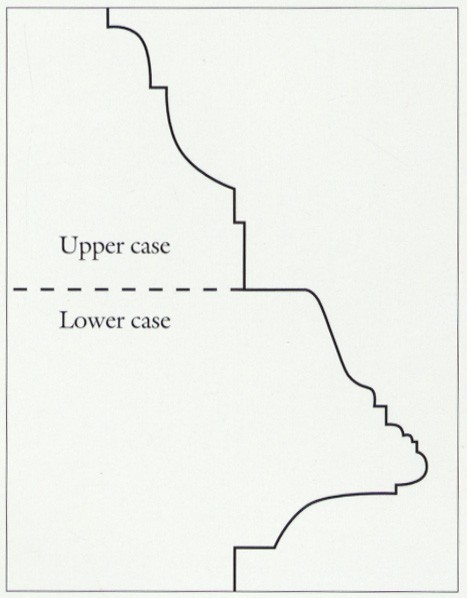

Detail of the waist moldings of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 5. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Detail of the waist moldings of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 3. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Providence, Rhode Island, 1760–1785 (desk), 1795–1810 (bookcase). Mahogany with chestnut, white pine, and cedar. H. 95 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The bookcase was produced at a later date to accompany the desk by John Carlile, Jr. (see fig. 4).

Detail showing the back edge of the cornice moldings of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Providence or Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1790. Mahogany with cherry, chestnut, and tulip poplar. H. 89", W. 39", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Since the second half of the nineteenth-century, Rhode Island block-and-shell furniture has been collected, written about, and coveted; yet, only within the past fifteen years have scholars recognized that some of this extraordinary furniture might have been made in Providence rather than in Newport. As early as 1900, furniture historians such as Luke Vincent Lockwood began to observe significant differences in objects that can now be identified as products of a Providence school. In Colonial Furniture in America (1901), Lockwood illustrated the renowned nine-shell blockfront desk-and-bookcase originally owned by Joseph Brown (fig. 1) and noted “A peculiarity not often seen on block-front pieces is that the drawers are overlapping instead of being finished with the narrow moulding above the drawers, as is usual.” In 1913, Lockwood expanded his publication and added more salient observations. The second and third editions included the four-shell blockfront chest-on-chest originally owned by John Brown (fig. 2) and Lockwood’s comments on it and the aforementioned desk-and-bookcase:

• The cornice moldings differ a little from the regular Rhode Island type and consist of a quarter-round, a fillet, a cyma recta, a fillet, a cove, an astragal, a fillet, and a small cove.

• [Both pieces have] boxes at either end of the scrolls.

• The base moldings are composed of a cove, a fillet, and a quarter-round, which differ from the regular type which are a cyma reversa and a fillet.

When Wallace Nutting illustrated these pieces along with the nine-shell chest-on-chest (fig. 3) in his Furniture Treasury (1928), he also noted that “boxes under the corner urns are found on two or three other pieces, and are also seen on English and American clocks.”[1]

During the 1920s, antiquarians began speculating on the possible makers of these objects. When the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 3 appeared in the January 1922 issue of Antiques, it was “supposed by some to have been [made by] John Goddard.” Just two years later, L. Earle Rowe published an article on Providence cabinetmaker John Carlile, Jr., and noted that “the period of investigation and historical research had begun.” Ironically, Rowe cited no documented or attributed products by his subject. Newport cabinetmaker John Goddard first received major attention in an exhibition at the Rhode Island School of Design organized by Providence architect Norman M. Isham in 1927. Isham featured the Joseph Brown desk-and-bookcase as “the most elaborate of the secretaries and thus of the whole exhibition.” He noted that the cleats on the fallboard are mitered at the top, the shells “are worked out of the solid,” and “the moulding around the desk is more elaborate . . . [consisting of] a quarter-round and a filleted cavetto instead of the usual ogee.” Isham also pointed out the elaborate cornice and included a series of line drawings and observations about the construction of the piece. Despite these distinctive features, he, Lockwood and Nutting continued to attribute these case pieces to Newport cabinetmakers.[2]

Interest in Rhode Island furniture grew during the mid-twentieth century. Mabel M. Swan’s 1946 and 1950 articles on the Townsends and Goddards introduced new documentation on Newport cabinetmakers, particularly those who left Rhode Island during the Revolution, but she neglected to mention Providence tradesmen. Ralph E. Carpenter’s The Arts and Crafts of Newport (1954) and the exhibition that inspired it (held at the Hunter House and sponsored by the Preservation Society of Newport County) were important catalysts for scholarship in the next half century. Wendell D. Garrett published a checklist of Newport cabinetmakers in 1958, followed by one on Providence tradesmen in 1966. His efforts to identify Providence cabinetmakers were augmented by two notable and longtime Providence residents. From the 1960s to his death in 1994, Joseph K. Ott made immeasurable contributions to the study of Rhode Island furniture makers, their products, and their patrons. Similarly, Eleanore B. Monahon documented the work of several generations of cabinetmakers including the Rawsons, Howards, and Grinnells.[3]

In 1982, Ott published photographs of a desk (fig. 4) that resembled Newport examples, but was inscribed “Providence August 6th 1785 / John Carlile junr of / said town / Joyner.” Ott astutely observed that the brackets of the ogee feet had a distinctive ovolo shape like those on several block-and-shell pieces with Providence histories. It was not until 1984, however, that Michael Moses noted that four distinctive pieces of block-and-shell case furniture “were all so similar to each other and so different from the general Newport examples that all must have been made by the same craftsman.” Citing the Carlile desk, Moses suggested that a “nine shell secretary and the other examples in this group were made in Providence and possibly by a member of the Carlyle family.” Two years later, J. Michael Flanigan acknowledged the possibility of a Providence block-and-shell group in his exhibition catalogue of the Kaufman collection. However, Ralph Carpenter’s article, “A Comparative Study of the Work of John Carlile, Jr. of Providence and the Townsends and Goddards of Newport,” was the first to explore the authorship of this small but impressive group of Rhode Island furniture. Building on the research of these scholars, this article will identify and examine the blockfront case furniture of Providence cabinetmakers and explore the context in which these objects were made and used. A related subgroup of straight-front secretary-and-bookcases with pitch-pediments also will be examined because of its significant connection with the unique block-and-shell chest-on-chest with pitch-pediment that is an important part of the Providence block-and-shell story (fig. 5).[4]

Patrons and Craftsmen: Intertwining Relationships

Most of the case furniture examined in this study has strong family histories supported by a combination of documentation, provenance, and oral tradition. Many of these owners were linked by birth, marriage, and mercantile activities, and most lived and worked in close proximity to one another. Many patrons also belonged to the same church or Quaker Meeting, so their bonds were religious as well as secular.

In 1770, Providence had 4,321 residents, whereas the flourishing town of Newport had 9,209. Because of the Revolution and British occupation, Newport’s population dropped to 5,299 by 1776. Newport’s population began to grow after the war, but by 1800 Providence was well on its way to becoming the commercial and intellectual center of Rhode Island. In 1810, Providence had 10,071 inhabitants, whereas Newport had 7,907.[5]

The shrewd business acumen and success of Providence merchants and artisans during the second half of the eighteenth century played a pivotal role in this dramatic shift in population and power. Members of the Brown family, along with numerous relations and mercantile associates, were the primary civic and business leaders of their time. They were one of the wealthiest and most influential families in Providence and were major patrons of local cabinetmakers as well as Newport tradesmen. The four Brown brothers, Nicholas (1729–1791), Joseph (1733–1785), John (1736–1803) and Moses (1738–1836), were among the leading merchants in eighteenth-century Providence. As founders of Brown University, they were also key promoters of the educational and intellectual life of the city. After the death of their father James (d. 1739), the brothers were raised by their uncle Obadiah Brown (1712–1762), who had begun the family’s mercantile business with their father. Obadiah, whose own four sons died young, trained his nephews in business and eventually made Nicholas, Joseph, and John partners.[6]

The Browns’ connections with Newport were both secular and religious. Mercantile connections between Providence and Newport were particularly strong. In 1783, the Brown brothers partnered with Newport merchant George Benson to form Brown and Benson. Nicholas and John Brown were regular patrons of the Goddards, and they occasionally procured furniture for themselves as well as for local friends and merchants in faraway places. On August 29, 1760, John Goddard informed John Brown that he had “Compleated the Tea Table, and have the other Tables and Chairs in good Forwardness.” In 1766, Nicholas Brown and Company ordered “a Handsome Mahogany Arm Chair as a Close Stool for Sick Persons with a Pewter pan . . . for a gentleman in the West Indies.” In his response to the order, Goddard wrote, “I should be glad if thou or some of thy Brothers & I could agree abought a desk & Bookcase which I have to dispose of.” Both John and Nicholas owned monumental Newport desk-and-bookcases (fig. 6) and block-and-shell bureau tables, and Moses owned a plain Newport chest-on-chest. John Brown also owned a handsome pair of roundabout chairs that probably were the product of John Goddard’s shop. Surprisingly, no Newport furniture owned by Joseph Brown is known, but his 1786 inventory lists “1 bureau table and drawers 6.0.0” in the “South Parlor Chamber.” Judging from the relatively high value, the bureau table may have been a block-and-shell piece.[7]

Although Joseph did not possess the business acumen of his brothers, he was the most intellectual. In his later years, he became a professor of experimental philosophy at Brown University. He was also a competent mechanic, knowledgeable about electricity as well as architecture. His extensive library contained two architectural design books—James Gibbs’s A Book of Architecture (1728) and Abraham Swan’s The British Architect (1745). Along with James Sumner, an architect-builder from Boston, Joseph was the designer of the First Baptist Church (1774–1775), as well as his own house at 50 South Main Street (1773–1774). Scholars have noted parallels between the pediment of his house (fig. 7) and the pediments of Providence block-and-shell pieces, which have extended sides that rise above the cornice molding to form “boxes.” The architectural design appears to have been taken directly from William Salmon’s Palladio Londinensis (1734), a publication owned in Providence by Martin Seamans, a carpenter-builder who worked on projects in association with Joseph Brown. Although it is not known if Joseph Brown owned any Newport block-and-shell furniture, he undoubtedly saw it in the houses of his brothers and neighbors. He did own at least two Providence block-and-shell pieces (figs. 1, 3), each having nine carved shells.[8]

John, Joseph, and Nicholas Brown were Baptists, but Moses became a Quaker in 1774. From then on Moses maintained close ties with a wide circle of Friends, both at home and abroad. In 1783, he wrote Quaker clockmaker Thomas Wagstaff: “A Neighbor of Mine Caleb Wheaton and his father Comfort Wheaton have apply’d to me to Introduce them to a Watchmaker in London that they might in future Write to for any Article in the Watch Business.” Moses was a generous and benevolent Friend and as enterprising and wealthy as his three older brothers. During the Revolution, he spearheaded efforts to distribute food and funds to the poor and needy. On February 29, 1776, Newport cabinetmaker Edmund Townsend wrote to Moses:

Freind Brown . . . you had kindly offered to let the Town of Newport have . . . one hundred pounds Lawfull Money [on loan]. . . . [A town meeting appointed me] . . . Treasurer to hire the same and give my obligation for it as this money will be appropriated for the relief of the poore whose necessity is extreamily Great.

When Brown attempted to collect this loan thirteen years later, Townsend responded:

Your letter by Mr. [William] Almy was duly rec’d and has been shewn to the Gentlemen you mention; some of whom are already Creditors to the Town, and assure me it would be very inconvenient to them to Augment their Debt at this time. I have also communicated the Contents of your Letter to others of the Inhabitants, they all express great Concern at the present Inability of the Town to comply with your request, Owing to causes with which you are not wholly unacquainted. It is next to an impossibility for them to discharge any part of their Debts in the distressed State they are now in, but they are in hopes that a change of affairs will soon take place, and enable them to comply with the requisitions of their Creditors. And any endeavors of mine to promote so desirable an Event, will not be wanting.

This correspondence is a telling reminder of the economic devastation Newport experienced during and after the Revolution. Ironically, this very situation probably contributed to the production of Providence block-and-shell case furniture.[9]

The Bowens were another eminent Providence family closely intertwined with the Browns. In December 1762, Jabez Bowen (1739–1815) married Sarah Brown (1742–1800), daughter of Obadiah Brown and cousin of the four Brown brothers. In effect, Jabez Bowen became a brother-in-law (though actually cousin-in-law) to the Browns since Sarah’s father had raised them. A lawyer by profession, Bowen served on the Town Council (1773–1775), was a representative in the General Assembly (1777–1790), and served as Deputy Governor in 1788. He commanded a regiment in the Revolutionary War, and was a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1790. He was also a noted member of St. John’s Lodge, serving as Grand Master Mason from 1794 to 1799. Bowen was involved in several ventures with the Browns, being a partner in the iron business at Hope Furnace. Jabez and Sarah Bowen resided on Main Street, in the center of town, opposite and just north of the Market House (fig. 8). They were among the few Rhode Islanders who had their portraits painted by John Singleton Copley.[10]

Since Obadiah Brown died just six months prior to his daughter Sarah’s marriage, her cousin Moses helped procure furniture for her new home. Correspondence between John Goddard and Moses Brown details the purchase of a tea table, “common” chairs, and a chest-on-chest for the newlyweds. When asking Brown what type of chest-on-chest Bowen wanted, Goddard wrote:

I know not wither he means to have them different from what is common, as there is a sort which is called a Chest on Chest of Drawers & Sweld front which are Costly as well as ornamental. Thou’l Plese to let me know friend Bowens minde that I may Conduct accordingly.

If Bowen purchased a chest-on-chest with a “sweld” front, it may be the one shown in figure 9. His cousin-in-law, John Brown, owned a similarly configured Rhode Island chest-on-chest; however, Brown's example has features characteristic of the “Providence school” (see fig. 2). Since John Brown married two years before the Bowens, he may have ordered his chest-on-chest first; however, it is more likely he commissioned it later and copied Bowen’s Newport example.[11]

Bowen ordered furniture from the most prominent Quaker cabinetmakers of Newport, but he also patronized Providence craftsmen. An extraordinary tall clock case (fig. 10) with a movement by London clockmaker George Sommersall (w. 1752–1773) is clearly a Providence example. Another closely related case houses a movement by Providence clockmaker Seril Dodge (1759–1802) (fig. 11), who built his house in Providence on land purchased from Moses Brown. Like Moses, Dodge was apparently a Quaker. In 1791, Moses negotiated the purchase of the Dodge house, directly opposite First Baptist Church (designed by Joseph Brown), for the estate of his deceased brother, Nicholas. The house was then renovated for Nicholas’s widow, Avis Binney Brown. Moses Brown’s associations with Dodge were numerous. In 1789 and the early 1790s, Dodge worked for Moses and his Quaker son-in-law and partner, William Almy, when they set up their immensely profitable cotton mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.[12]

Another Brown-Bowen connection involved Bowen’s half-brother, William (d. 1832), who married Sarah Corlis in 1769. Sarah’s mother, Waitstill Rhode (1722–1783), was married to Captain Jeremiah Brown, a brother of Obadiah’s and uncle to the four Brown brothers; hence, like Jabez Bowen, William was also a cousin to the Browns by marriage. It is not surprising that William and Sarah owned a Providence block-and-shell desk-and-bookcase (fig. 12), since they probably saw Newport and Providence pieces in the homes of their friends and relatives. By 1774, William and Sarah were neighbors of Joseph Brown, who in that year built a new house on Water Street just south of College Street. The Bowens lived at the corner of College and Water streets, almost directly opposite the Market House.[13]

Although Nicholas Brown owned block-and-shell furniture from Newport, it is not known if he purchased any Providence examples. An extraordinary Providence block-and-shell chest-on-chest (fig. 5) descended in his family and may have been ordered by Nicholas about 1785, when he married Avis Binney of Boston. It is more likely, however, that his son Nicholas (1769-1841) ordered it soon after his marriage to Ann Carter in 1791. The couple occupied the elder Nicholas’s house on South Main Street from 1791 until 1814 when they moved to the Joseph Nightingale house (built 1791) on Benefit Street. A 1870s photograph (fig. 13) shows the chest-on-chest in the upstairs hallway of the house. The pitch pediment and molding of the chest have parallels with interior details in Providence homes. Nicholas, Jr., grew up in a house with related architecture in the principal rooms. His uncles, Joseph and John, had similarly sophisticated interiors, and in 1791 he and his uncle, Moses, commissioned woodwork with pitch pediments in several rooms of the Dodge house.[14]

Nicholas, Jr.’s, sister Hope (1773–1855) married Thomas Poynton Ives (1769–1835) in March 1792. Originally from Massachusetts, Ives had apprenticed in the firm of Brown and Benson when he was thirteen. In 1796, he became a partner, and the business name changed to Brown and Ives. Like the Brown brothers, Ives was a successful businessman and contributed greatly to the cultural life of Providence. By 1805, he and his wife had built a magnificent brick house on Power Street, just up the hill from John Brown’s house (built 1788) and within sight of the Nightingale house. While the Iveses do not appear to have owned Providence or Newport block-and-shell furniture, they probably commissioned the pitch-pediment secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 14 for their new home. Ives undoubtedly knew of Nicholas Brown’s pitch-pediment chest-on-chest as well as a Philadelphia pitch-pediment clothespress owned by John and Abigail Brown Francis (fig. 53)[15]

Tristam Burges (1770–1853) was another prominent resident of Providence and an acquaintance of the Iveses and Browns. Originally from Massachusetts, Burges graduated from Brown University in 1796 and gained admittance to the Rhode Island Bar in 1799. In August of 1800, Burges was appointed to the Providence School Committee Advisory Board, which consisted of other prominent citizens including Jabez Bowen, Amos Atwell, Stephen Gano, and John Carlile, Jr. Stephen Gano was related to the Browns through his marriage to Joseph Brown’s daughter Mary in 1799. In 1801, Burges married Mary Arnold, the daughter of Welcome Arnold, a prominent merchant who participated in several business ventures with the Browns, including co-ownership of a distillery in 1788. Burges became a chief justice of Rhode Island in 1815 and a representative to Congress in 1825, a position he held until 1835. Like Thomas Poynton Ives, he also owned a Providence piece with an elaborate pitch-pediment (fig. 15).[16]

Providence blacksmith Amos Atwell (d. 1807) undoubtedly knew several members of the local mercantile community who were owners of Providence block-and-shell furniture. Unlike the Browns and the Bowens, he lived on the west side of Providence River in an area populated primarily by artisans like Job Sweeting and the Prouds, Rawsons, and Potters (fig. 16). Like Boston silversmith and engraver Paul Revere, Atwell was an entrepreneurial artisan who became a leader among the mechanics and manufacturers of Providence. He served on the Town Council with merchants such as Nicholas Brown and in 1789 was one of the founding members of the Providence Association of Mechanics and Manufacturers, first serving as chairman and later as treasurer. In 1790, Atwell was among a distinguished list of Providence residents who petitioned the state to incorporate as the River Machine Company; this group included Moses Brown, Welcome Arnold, Joseph Nightingale, George Corlis, George Benson, Nicholas Brown, John Brown, and John Francis, a son-in-law of John Brown. Atwell’s probate inventory, taken in 1807, reveals that he was a prosperous man of the middling sort. Listed “In the Parlour” was “1 Cherry tree Desk & Book Case” valued at $40 and an impressive assemblage of books. This desk-and-bookcase (fig. 17) is an important piece from the Providence block-and-shell school.[17]

Three generations of cabinetmakers from the Rawson family also lived on the west side of the Providence River. Born in Mendon, Massachusetts, Grindal Rawson (1719–1803) settled in Providence by 1752 when he worked on Long Warf. Although nothing is known about his apprenticeship, some scholars have speculated that he trained in Massachusetts, perhaps Boston. Much of the early furniture attributed to him suggests a Massachusetts influence both in terms of design and construction. In 1756 and 1757, he and six other tradesmen signed the Providence Cabinetmakers’ Agreement, which set prices for specific items of furniture. In 1759, Grindal owned a house at the north end of Richmond Street, near the Potters, the Prouds, and Job Sweeting. In the 1780s, he formed a partnership with Jonathon Wallen and took his eldest son, Joseph, as an apprentice to their firm. Joseph evidently completed his term by 1789. The Direct Tax Survey indicates that he was building a new house on Sugar Lane in that year.[18]

Although there is no documentation that Grindal Rawson made furniture for the Browns, Nicholas, Sr.’s, estate papers from 1792 and 1793 mention an “Amot of award in fav. Grindal Rawson agt the Estate . . . £36.” Rawson certainly had connections with prominent families in both Newport and Providence. His second wife, Elizabeth Boyd (m. 1752), was from Newport, and his fourth wife, Nancy Freeman (d. 1771), was the sister of Amos Atwell. The fact that Rawson, at age thirty-three, married a woman from Newport raises the possibility that he might have been working as a journeyman in that city prior to settling in Providence.[19]

The Carliles were another important family of Providence woodworkers; however, they lived on the east side among the merchants and close to the wharfs. Originally from Boston, John Carlile, Sr. (1727–1796), arrived in Providence by 1754, when he married Elizabeth Franklin Compton. Between 1756 and 1769, he bought turned furniture components from William Barker, including chair legs and “pillars.” Carlile’s location near the wharves was advantageous. Referred to as a “ship-joiner” in period documents, he worked on ships for the Browns during the 1760s and charged Nicholas Brown and Company for “making a house over your Boat” in 1768. A book of “notes of Hand Due to Brown & Benson” indicates that Carlile paid the firm with “2 Maple Desks” and “Cabin’Work” in 1786. He also did work for Moses Brown in the 1780s and 1790s.[20]

Carlile had five sons, but only John, Jr. (1762–1832),Benjamin (1766–1831), and Samuel (1770–after 1838) appear to have been active participants in the business. By 1784, they leased land along the Providence River suitable for erecting a shop just south of the brick Market House and almost opposite the houses of William Bowen and Joseph Brown. Bowen witnessed John Carlile, Sr.’s, will in 1795, and Carlile’s son, Samuel, helped appraise Bowen’s estate in 1832. In 1797, the Carlile brothers moved up the hill to a three-story workshop directly opposite the Joseph Nightingale house and close to the John Brown house (fig. 18). The 1798 Direct Tax Survey indicates that Benjamin and Samuel owned a twenty-by-forty-foot, two-story workshop on Clark and Nightingale’s upper wharf. Entries in the business ledgers of merchant Welcome Arnold suggest that John Carlile, Sr. and Jr., were primarily cabinetmakers, whereas Samuel and Benjamin worked as carpenters and shipjoiners. During the early nineteenth century, John, Jr., and Samuel also operated a lumberyard. John, Jr., was the most active in civic affairs. He served on the Town Council from 1818 to 1824, was a founding member of the Providence Mechanics and Manufacturers Association, and was a member of St. John’s Masonic Lodge, where he served as Grand Master from 1817 to 1824.[21]

The Stylistic Vocabulary of the Providence School

Several stylistic and technical details differentiate late eighteenth-century Providence furniture from contemporary Newport pieces. External features include:

• Relief-carved convex shells

• The predominant use of lipped rather than beaded drawers

• Cyma bracket feet with a distinctive torus drop

• Applied rosettes with bulbous convex centers and one or two layers of simple fluted petals

• Finials with cup-shaped urns and short flames

• Extended case sides that create “boxes” on the sides of pediments

• The interior arrangement of the desks

• Complex moldings

• Bookcase doors with distinctively shaped stiles and rails (on pitch-pediment pieces)

Although each case piece examined for this study exhibited different variations of these stylistic features, parallels within the group support the notion of a Providence school.[22]

Shells on case pieces from the group are easily distinguishable from the Newport ones. Newport artisans invariably applied convex shells (fig. 19), whereas their Providence counterparts carved them from the solid (fig. 20). The Providence shells also have a more sculptural quality, and their half-round perimeters are relieved at the termination of each flute. The techniques employed by Providence tradesmen were much less economical than those of Newport artisans. Because they carved their shells from the solid, Providence tradesmen had to use thicker stock and spend more time relieving and cleaning up the ground.

Another feature that distinguishes Providence blockfront furniture from that of Newport is the use of lipped rather than beaded drawers. Whereas most Newport straight-front case pieces have lipped drawers, blockfront pieces made in that town typically have plain drawers and cockbeading on the case. Drawer fronts with lipped edges and thumbnail moldings required more time to produce than plain ones, particularly on blockfront forms, which have curved surfaces and short flats that required carving. The block-and-shell chest-on-chest that reputedly belonged to Jabez Bowen (fig. 9) demonstrates the Newport convention of lipping the drawers of straight-front chests and applying cockbeading to those of blockfront examples. The Bowen chest is unusual in that it combines both lipped and cockbeaded drawers in one piece. Considering the fact that Providence cabinetmakers were as skilled as their Newport counterparts, their use of more labor-intensive carving and construction methods must have been a deliberate choice. Whether this choice reflects their training, their efforts to distinguish their work from Newport competitors, the demands of their patrons, or other factors remains to be determined.[23]

On most New England blockfront pieces, the foot faces are blocked to match the adjacent curves of the base molding. The responds, however, differ considerably, with variations found in the combinations of cusps, drops, and volutes on each piece. The bracket foot used by Providence cabinetmakers on both blockfront and straight-front pieces is distinctive, although two basic variations exist (figs. 21, 22). The foot design shown in figure 22 is the most prevalent, appearing on six of the eleven pieces examined for this study. This pattern may simply be a later variation of the foot design seen in figure 21. Almost none of the feet on the Providence pieces are identical to each other due to the different proportions of each piece, but the similarities between the shape of the feet are so close that one expects them to have been derived from the same template. Although these foot designs are distinctive to Providence, there are parallels with feet on pieces from the North Shore of Massachusetts.[24]

The rosettes on pieces in the Providence group are also very similar. All appear to be by the same carver or from the same shop tradition. The rosettes, which have convex centers and either one or two rows of fluted petals, were carved from small circular blocks of wood that were applied to the volutes of broken-scroll pediments (see figs. 34–36). By comparison, Newport pieces rarely have carved rosettes. When they do, the rosettes are cut from the solid and have smaller central elements and petals that are more widely spaced.[25]

Structural Features of the Providence School

In addition to the aforementioned stylistic details, several structural features suggest that these Providence case pieces are the products of a multigenerational cabinetmaking school. The feet, for example, are supported by a vertical glue block with horizontal flankers (fig. 23). On many of the Providence pieces, the cabinetmaker attached the foot faces with nails or screws. The back feet have rear brackets (made of secondary wood) that are either dadoed to the side faces or butted against them. Some of these brackets are ogee shaped, whereas others are diagonal (fig. 24). Similar variations occur on contemporary Newport feet.

The drawers of the Providence pieces are similarly constructed in a uniform manner. The frames typically have half-dovetails at the top of each side, whereas Newport drawer frames usually have half-dovetails at the top and bottom. The dovetails on the Providence drawers also tend to be less compact (figs. 25, 55). On most of the Providence pieces, the bottom boards are oriented front to back. These boards are invariably dadoed to the drawer sides; however, some are set into a groove in the drawer fronts, whereas others are set into a rabbet and nailed. The drawer bottoms also have glue strips, most of which were sawn off at a 45-degree angle at the back (fig. 26).[26]

Most of the desks in the Providence group have fallboards with mitered cleats rather than the more common squared off ones. Nearly all of the interiors, which are quite variable, differ from the typical layout of contemporary Newport desks. The only exception is the desk signed by John Carlile, Jr., which has a conventional Newport-style blocked interior (fig. 27). Two of the Providence straight-front desk-and-bookcases have interiors that follow Newport plans; however, they lack the characteristic blocking and shell carving (see fig. 15).

A subgroup of pitch-pediment pieces examined for this study have a few construction and design features that are common to them. The desk-and-bookcases, for example, have doors with very distinctive shaping to the inside edges of their frames. The ogees, fillets, and scotias of the stiles and rails combine to produce a shape reminiscent of the projecting rounded corners of Rhode Island rectangular-top tea tables. All of the door frames are constructed in the same basic fashion. The rails are through-tenoned, and the faces of the stile-rail joints are mitered (fig. 28). Other parallels can be observed in the cornice moldings of the bookcases, all of which feature the identical sequence of elements.[27]

Cornerstones of the Providence Group

The “Cherry tree Desk & Book Case” listed in Amos Atwell’s 1807 probate inventory has remained in the Providence area since its initial purchase (fig. 17). Accompanying the desk is a late nineteenth-century affidavit signed by Lyman B. Goff, president of the Union Wadding Co. in Pawtucket, which states:

Grindal Rawson, born in Mendon in 1719, moved to Providence, R.I. in 1741, and soon after made this secretary for Mr. Amos Atwell, of Providence. After the death of Mr. Atwell it was purchased by Mr. Joseph Rawson, son of Grindal, and by him sold to Henry Steere, and on the death of Mr. Steere it was purchased by Lyman B. Goff of Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Goff probably purchased the desk-and-bookcase when the collection of Providence antiquarian Henry J. Steere was auctioned after his death in 1890.[28]

No signed or labeled pieces by Grindal Rawson are known, despite the fact that he worked in Providence for nearly fifty years. The high chest of drawers illustrated in figure 29 has been attributed to him based on its provenance. The shells on the knees are very similar to those on the plinths of three tall case clocks with either Providence movements or provenances (figs. 30, 31). One of the clocks has a movement by George Sommersall and a history of ownership by Jabez Bowen (fig. 10). Two others have movements by Providence clockmaker Edward Spalding (figs. 32, 33). The composition and execution of the shells on the plinths is unusual; however, they are carved from the solid in typical Providence fashion. The treatment of the shells on the tall case clock plinths and high chest knees strongly suggests that these pieces are all from the same shop or school.[29]

A fourth tall case clock, with movement by Seril Dodge of Providence (fig. 11), relates closely in appearance and construction details to the Jabez Bowen tall case clock (fig. 10) but lacks the carved shells on the plinths. The rosettes on these two tall case clocks (figs. 10, 11) and on the Atwell piece (fig. 17) are similar in design and execution, strengthening the desk-and-bookcase’s association with Rawson. Although the sizes of the rosettes and their convex centers differ, all have eight-fluted petals and appear to be by the same carver (figs. 34-36). Other construction and design features reinforce the theory that the clocks are from the same cabinet shop. Their molding profiles are similar, and both cases have through-tenons (fig. 37) and exposed tenons (fig. 38) in the same locations. Not only are these features distinctive, but this group of Providence clocks differs from contemporary Newport examples in being proportionally shorter and wider.

The integration of Providence and Massachusetts details on the Atwell desk-and-bookcase supports an attribution to Rawson, who may have trained in or near Boston. Providence characteristics include the use of lipped drawers, mitered-cleats on the fallboard, and the aforementioned rosettes. The shells on the fallboard represent a significant departure from other examples in the Providence group. They are applied like Newport shells rather than being carved from the solid.

Like many Massachusetts desks, the Atwell example has fallboard supports that are the same height as the drawer between them. By contrast, the supports on Rhode Island desks are usually half that height (see fig. 39). The exterior drawers on the Atwell desk are unusual for any area. Most blocked drawer fronts have interior surfaces relieved to match the curves of the front, but those on the Atwell desk are straight across the back (fig. 39).

The interior compartments of the Atwell desk-and-bookcase provide the strongest evidence of Massachusetts influence. The hollowed arches in the bookcase section are similar to those on Boston examples (fig. 40), although the latter are sometimes carved, inlaid, or decorated with trompe l’oeil ornament. Similarly, the receding interior drawers and removable prospect section of the desk follow Massachusetts rather than Newport or Providence plans (fig. 41). The prospect section houses two secret drawers, another feature not typically found on Rhode Island desks. The interior drawers of the Atwell desk are also constructed like those of many Massachusetts examples: the bottom boards are oriented side to side, nailed into rabbets in the drawer front, chamfered and dadoed to the sides, and nailed up into the backs.[30]

These stylistic and structural details suggest that the maker of the Atwell desk-and-bookcase trained in Massachusetts, was familiar with Newport block-and-shell furniture, and attempted his own interpretation of the form for a Providence patron. Many Newport cabinetmakers looked to Boston as a style center, and in some cases copied Boston furniture. The earliest dated American blockfront is a desk-and-bookcase inscribed “J Coit/ 1738” and “Job Coit jr/ 1738.” It is likely that the blockfront style subsequently spread to Newport, where artisans such as the Townsends and Goddards began modifying the form. If Grindal Rawson was the maker of the Atwell desk-and-bookcase, the possibility that he trained in Massachusetts and worked as a journeyman in Newport before settling in Providence would account for the melding of regional details on the Atwell desk-and-bookcase.[31]

A second desk-and-bookcase that exhibits both Massachusetts and Rhode Island characteristics originally belonged to Providence physician William Bowen (fig. 12), half-brother of Jabez. This piece is the only one that combines shells applied like Newport examples (on the fallboard) with shells that are carved from the solid like Providence ones (on the bookcase). Other Providence features include applied rosettes, mitered cleats on the fallboard, torus and cavetto curves of the feet, and design of the desk interior. The desk interior features two long drawers with molded fronts, surmounted by five smaller drawers with plain fronts. In the center is a shell-carved prospect drawer flanked by pigeonholes with shaped dividers (fig. 42). Similar interiors occur on four other Rhode Island desks, one of which descended in the Rawson family and is attributed to either Grindal or Joseph. Another originally belonged to Providence merchant Welcome Arnold. All of these interiors differ significantly from those of contemporary Newport desks.[32]

Like the Atwell desk-and-bookcase, the Bowen example has several features typical of Massachusetts furniture: hollowed arches inside the bookcase, door panels with ogee shaping below the shells (fig. 43), beaded rather than lipped drawers, and base molding attached with a “giant” dovetail (fig. 44). Surprisingly, the hollowed arches are the only detail shared with the Atwell desk-and-bookcase. Whereas the blocking on the Atwell desk-and-bookcase was ineptly executed, the blocking on the Bowen desk-and-bookcase is equal to that of any other Providence piece.[33]

The chest of drawers illustrated in figure 45 is another piece that exhibits both Providence and Massachusetts characteristics. Its ogee bracket feet are virtually identical to those on the Joseph Brown (fig. 1) and William Bowen desk-and-bookcases (fig. 12) and on a desk inscribed by John Carlile, Jr. (fig. 4). Like the Bowen desk-and-bookcase, the chest has drawers with plain edges and cockbeading on the case rather than lipped drawers. The drawers have dovetails, dadoed bottoms, and other features typical of Providence work; however, the bottom boards are oriented side to side rather than front to back. Certain other construction details follow Massachusetts practices. The top, for example, is attached with a sliding dovetail.[34]

Although the chest of drawers and the Atwell and Bowen desk-and-bookcases are clearly related, their construction suggests that they are by different hands. The applied shells and simple moldings on the desk-and-bookcases are more closely allied with Newport cabinetmaking practices than with mainstream Providence work. The melding of Massachusetts, Newport, and Providence features raises several questions. Are the chest and desk-and-bookcases the earliest known Providence blockfront forms? Do the disparate features of these pieces signify the work of Providence makers who had simply seen Massachusetts and Newport examples, or do they document the emergence of a more cohesive “Providence school?”

The Browns of Providence: Their Furniture and Their Patronage

Joseph and John Brown and their nephew Nicholas, Jr., all patronized Providence furniture makers. Living near the Market House on Water Street from the time of their respective marriages in 1759 and 1760, Joseph and John were close neighbors of their brother Nicholas and Jabez and William Bowen. John and Sarah Brown lived in the brick house they built in 1760 until they moved up the hill to their new mansion in 1788. In 1774, Joseph built a new brick house almost directly across the street from his earlier house. These moves may have provided an occasion for ordering new block-and-shell furniture. Joseph owned a desk-and-bookcase and chest-on-chest, while John had a chest-on-chest; all three pieces were made in Providence.

Joseph Brown’s interest in architecture and the parallels between the pediment of his house and those of Providence case pieces suggest that he played a role in the design of his house and furnishings. He clearly commissioned furniture different from that of his peers. His desk-and-bookcase (fig. 1) and chest-on-chest (fig. 3) are unique in having nine carved shells each, suggesting the hand of a “gentleman” designer.

Joseph’s desk-and-bookcase is the best known of the Providence block-and-shell group. It may have been the “mahogany Desk-and-bookcase . . . 12.0.0” listed in the “North Parlor” in his 1786 probate inventory. A descendant subsequently sold the piece to the firm of Brown and Ives, who donated it to the Rhode Island Historical Society. Joseph’s chest-on-chest, which has a similar line of descent, may have been the “mahogany High case of drawers . . . 15.0.0” listed in his “Great Bed Room.” Antique dealer Joe Kindig, Jr., purchased the chest-on-chest from a Brown descendant and subsequently sold it to Henry Francis du Pont.[35]

The design and construction of Joseph Brown’s desk-and-bookcase link it to other examples in the Providence block-and-shell school. The bracket feet have front faces identical to those of the Bowen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 12) and similar to those of the desk inscribed by John Carlile (fig. 46). In contrast to its elaborate façade, the interior of the Brown desk-and-bookcase is very simple (fig. 47). With a tier of central prospect drawers, flanking pigeonholes, and simple drawers below, the Brown interior relates more closely to that of the Bowen desk (fig. 42) than to contemporary Newport interiors. The Brown desk-and-bookcase also has rosettes with large convex centers and two layers of petals; however, there are fewer petals, and they lack the cuts found on the rosettes of the Bowen example (fig. 12).

The Providence chest-on-chest owned by John Brown (fig. 2) is almost identical to the Newport example owned by John’s neighbors Jabez and Sarah Bowen (fig. 9). Given the proximity of the Bowen chest and the possibility that it was ordered by John’s brother Moses, Bowen’s chest may have been a design source for John Brown’s Providence chest-on-chest. The Bowen chest, however, lacks the extended sides that form “boxes” flanking the bonnet. The Brown chest, like the Bowen desk-and-bookcase, is one of two Providence pieces with dovetailed base molding (figs. 44, 48). On the chest, this feature is only visible from the underside of the case. The joint is concealed on top by a strip of wood that elevates the upper drawer and accommodates the lip on its lower edge.[36]

Joseph and John Brown’s chest-on-chests (figs. 2, 3) and Joseph Brown’s desk-and-bookcase (fig. 1) have several features in common: the profile of the feet, similar moldings and finials, lipped drawers that are constructed in the same manner, extended sides that form “boxes” on either side of the pediment, and shells carved from the solid. Although the designs of the shells differ from piece to piece, each has deeply fluted convex lobes that terminate in typical Providence fashion(fig. 49). At least two factors may have contributed to these design variations. The artisans producing these shells may have been influenced by several different Newport varieties. Alternatively, the level of patronage for elaborate shell-carved furniture may not have been sufficient to encourage the development of standardized designs in Providence.[37]

Several pieces in the Providence group have chalk and/or pencil marks, score marks (fig. 50), and chalk sketches. The nine-shell chest-on-chest, for example, has a drawing of a vase-back side chair on a drawer bottom (fig. 51) and a sketch of an urn finial on the bottom board of the upper case (fig. 52). If these sketches are contemporary with the chest-on-chest’s manufacture, it probably dates no earlier than 1785. A pitch-pediment chest-on-chest that belonged to either Nicholas Brown, Sr., or Jr., is related in having chalk drawings of molding profiles on the top board of the upper case.[38]

Pitch-Pediments and Providence Preferences

Joseph Brown’s nine-shell chest-on-chest (fig. 3) links the earlier Providence case pieces with a later group of pitch-pediment furniture, including the chest-on-chest commissioned by either Nicholas Brown, Sr., or Nicholas, Jr., (fig. 5). The latter chest, which appears in an 1870s photograph of the second-floor hallway (fig. 13) of the family house on Benefit Street, represents a new stylistic trend in Providence furniture made during the last two decades of the eighteenth century. Rather than choosing a broken-scroll pediment, like those on many earlier Providence examples, the patron selected a pitch-pediment for his chest-on-chest.[39]

Although pitch-pediments occur in pre-Revolutionary Rhode Island interiors, they are not found on regional case pieces from the same era. Either Nicholas or his son could have specified that the chest have a pitch-pediment to match interior details in one of the family houses. Nicholas, Jr., for example, had overmantles with elaborate pitch-pediments installed in the Seril Dodge house before it was occupied by his stepmother, Avis Brown. Imported furniture represents another likely design source for the pitchpediments on late eighteenth-century Providence work. The Philadelphia clothespress illustrated in figure 53 may be the “valuable piece of Furniture” that John Francis imported into Providence in 1785. An agent for Brown and Benson, Francis married John Brown’s daughter Abigail in 1788. Other members of the Brown family and their business associates probably saw the press while visiting with John and Abigail. If so, the pitch-pediment on the press may have inspired the one on the chest-on-chest shown in figure 5.[40]

The chest-on-chest links the earlier Providence blockfront case pieces with a slightly later group of secretary-and-bookcases with pitch-pediments. The shell carving, foot profiles, drawer construction, and secondary woods have clear parallels in earlier Providence work (see figs.1–3, 12, 17). Although the cockbeading on the case of the chest-on-chest is somewhat atypical of Providence block-and-shell furniture, similar beading appears on the lower section of the Bowen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 12).[41]

The Nicholas Brown chest-on-chest (fig. 5) is most similar to the one owned by Joseph Brown (figs. 54, 55). Both have drawer dovetails that are more tightly spaced than those on other Providence blockfront pieces yet not as clustered as those on contemporary Newport examples (see fig. 25). This difference suggests that the Nicholas and Joseph Brown chest-on-chests are not by the same cabinetmaker that produced the other examples in the Providence group. The cornice and waist moldings on the Nicholas and Joseph Brown chests are also related and considerably more complex than those on other pieces in the Providence group. Both pieces have waist moldings attached to both the upper and lower cases (figs. 56, 57). The other blockfront pieces, with the exception of the John Brown chest-on-chest, have waist moldings attached only to the lower case[42]

Nicholas Brown’s chest-on-chest may have been one of the first pitch-pediment pieces made in Providence. The Ives secretary-and-bookcase (fig. 14), Burges secretary-and-bookcase (fig. 15), and bookcase added to the signed Carlile desk (fig. 58) appear to be by the same hand. The lower sections have virtually identical beaded drawers, bracket feet, and interiors, and all three bookcases have door frames with similar shaping, mitered face-joints, and through-tenons. The profiles of the waist and base moldings on all these objects are also related, though not identical.[43]

The pitch-pediments of the bookcases shown in figures 14, 15 and 58are similar to the one on the Nicholas Brown chest-on-chest (fig. 5). Three of these four pediments are constructed as separate units and sit on top of the case section below. Although the pediments on the Ives, Burges, and Brown pieces are fully enclosed, the one on the Carlile desk is not. The owner of the Carlile desk may have chosen an open pediment to cut costs. The cornice moldings on all four pediments are comprised of the same sequence of elements (fig. 59), which strengthens the argument that these pieces originated in the same cabinet shop.[44]

The pediment of the Ives secretary-and-bookcase differs in being integral with the upper section (fig. 14). Its roof is also capped with an extra board, which creates a more finished look. The inlaid paterae on the frieze and the prospect door are neoclassical features that further establish the object’s post-Revolutionary date. One other desk-and-bookcase that relates to the aforementioned pitch-pediment pieces is the flat-topped example shown in figure 60. Although the desk portion of this piece demonstrates aspects of Newport design, the bookcase section relates closely to the Providence pitch-pediment pieces. The similarity between elements of the bookcase doors and the sequence of cornice moldings on the flat-topped desk-and-bookcase and the pitch-pediment desk-and-bookcases suggests that all of these pieces were made by the same cabinet shop.

The style, structure, provenances, and historical context of the furniture examined in this study indicate that the entire group was made in Providence rather than in Newport. The British occupation of Newport during the Revolutionary War and the attendant decline in the city’s population and economy had a devastating effect on the furniture-making trades. By contrast, Providence merchants profited from privateering and provisioning the American forces. Unlike most of their Newport counterparts, these merchants were able to build elaborate houses and commission expensive pieces of furniture during the 1770s and 1780s.[45]

Summary

Although it is clear that Providence artisans made elaborate block-and-shell furniture, the more vexing question is who made what? Grindal Rawson, Joseph Rawson, Sr., John Carlile, Sr., and John Carlile, Jr., are the most likely candidates for makers of the Providence group. Grindal Rawson probably made the Atwell desk-and-bookcase and possibly several related tall clock cases; however, physical evidence suggests that the remaining pieces did not come from his shop unless he employed Newport-trained journeymen, had worked there himself, or had studied Newport pieces owned by Providence patrons.

The design and construction of the Bowen desk-and-bookcase and the John Brown chest-on-chest suggest that their maker trained in or near Boston. Since Grindal Rawson was born in Mendon and John Carlile, Sr., was “a native of Boston,” either could have served their apprenticeship in eastern Massachusetts where blockfront furniture was extremely popular. Could John Carlile, Sr., have been responsible for some of this work? Was he the maker of the fall-front desk with the Newport type interior (figs. 27, 58) that his son, John, Jr., inscribed in 1785? Did John, Jr., add the pitch-pediment bookcase to that desk, and might he be the maker of the entire pitch-pediment group? Or could Joseph Rawson, Sr., have continued in his father Grindal’s footsteps, making these later block-and-shell pieces as well as the pitch-pediment group?

The influence of Newport cabinetmakers on Providence work also remains a mystery. Did a Newport tradesman move to Providence and continue to make block-and-shell furniture there? Many Quakers left Newport during the Revolution, for short as well as long periods of time. Both Thomas Townsend and Abraham Redwood went to Mendon, Massachusetts, suggesting a Newport-Mendon connection that may include the Rawson family.[46]

On December 21, 1777, John Goddard’s son, Townsend, wrote to a friend, “When I left Providence I had not the time to fetch my tools which were in Kingston.” On June 15, 1782, the Providence Gazette reported that “Goddard and Engs, Cabinet-Makers from Newport,” had established a shop “on the wharf of Mr. Moses Brown.” A May 13, 1782, letter from Newport Quaker Thomas Robinson to Nicholas Brown reveals that one of the principals in the partnership was John Goddard’s son:

My neighbor John Goddard . . . has sent the Rudder of his Boat to his son [in Providence]. . . . I have taken the liberty to request thy friendly interposition . . . which will be kindly acknowledged by thy sincere friend.

The “son” was probably Townsend Goddard (1750–1790). In 1786, he was the executor of his father’s estate, and Edmund Townsend and “William Engs, jun.” were the “Commissioners” who signed a Newport Gazette notice directed to the “Creditors to the Estate of John Goddard.” William Engs or one of his relatives may have been the other principal of Goddard and Engs. The Goddards could thus have influenced Providence furniture styles during and just after the Revolution.[47]

In the October 1939 issue of Antiques, Charles Woolsey Lyon advertised a vase-back armchair with a kylix urn similar to several bearing the label of John Carlile and Son. Lyon, however, noted that the chair was “by the famous cabinetmakers, Goddard and Engs.” If Lyon’s chair was labeled, it could establish connections between Goddard and Engs and the Carliles.[48]

Although the presence of Newport-trained cabinetmakers in Providence remains speculative, Newport styles clearly influenced Providence work. The Browns, Bowens, and other members of the Providence elite patronized Newport tradesmen and were influential in developing local tastes for blockfront forms and bold shell carving. As trade with Newport declined during and immediately after the Revolutionary War, Providence artisans filled the gap by producing forms that were both similar to and different from Newport work. The number and variety of objects that survive suggest that Providence cabinetmakers were able to compete with their Newport counterparts for the most prominent patrons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their generous assistance the authors thank Denise Bastien, Luke Beckerdite, John Carpenter, Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., Robert P. Emlen, Linda Eppich, Dean F. Failey, Donald L. Fennimore, Henry H. Hawley, John Hays, Patricia E. Kane, Leigh Keno, Thomas S. Michie, Clark Pearce, Michael Podmaniczky, Kemble Widmer, and Martha Willoughby. Particular thanks go to the staffs at the John Carter Brown Library and the Rhode Island Historical Society Library. We especially thank the owners of all the objects examined in this study for their generosity, enthusiasm, and patience.

Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 1st ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), pp. 273–75. Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols., 2d ed. (1913; reprint ed., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926) 1:120–21, 246–48. Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 3 vols. (Framingham, Mass.: Old America Company, 1928), 1: figs. 317, 321, 701.

L. Earle Rowe, “John Carlile, Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 6, no. 6 (December 1924): 310–11; Norman M. Isham, “John Goddard and His Work,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design 15, no. 2 (April 1927): 14–24.

Mabel M. Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners, Part I,” Antiques 49, no. 4 (April 1946): 228–31. Mabel M. Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners, Part II,” Antiques 49, no. 5 (May 1946): 292–95. Mabel M. Swan, “John Goddard’s Sons,” Antiques 57, no. 6 (June 1950): 448–49. Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., The Arts and Crafts of Newport 1640–1820 (Newport: Preservation Society of Newport County, 1954). Wendell D. Garrett, “The Newport Cabinetmakers: A Corrected Check List,” Antiques 73, no. 5 (May 1958): 558–61. Wendell D. Garrett, “Providence Cabinetmakers, Chairmakers, Upholsterers, and Allied Craftsmen, 1756–1838—A Check List,” Antiques 90, no. 4 (October 1966): 514–19.

Joseph K. Ott, “Lesser-Known Rhode Island Cabinetmakers: The Carliles, Holmes Weaver, Judson Blake, the Rawsons, and Thomas Davenport,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1157. Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards (Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984), p. 303. J. Michael Flanagan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986), p. 76. Ralph Carpenter, “A Comparative Study of the Work of John Carlisle, Jr. of Providence and the Townsends and Goddards of Newport,” in The Walpole Society Notebook (Leeds, England: W. S. Manney & Son, Ltd. 1994), pp. 79–86. A larger group of tall clock cases with “boxed” sides and Newport-style shells is the subject of a forthcoming study. Although these cases contain works by Providence makers, such as Caleb Wheaton (1757–1827), their origin has not been firmly established. Since they all appear to be post–Revolutionary War, it is possible that Providence-style “boxed” sides were adopted by Newport makers. For more on these clocks, see Christopher P. Monkhouse, Thomas S. Michie, and John M. Carpenter, American Furniture in Pendleton House (Providence: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), pp. 89–90.

Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population before the Federal Census of 1790 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), p. 68. Peter Coleman, The Transformation of Rhode Island, 1790–1860 (Providence, R.I.: Brown University Press, 1963), p. 220.

For more on the Brown family, see The Chad Browne Memorial, 1638–1888 (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1888). For more on the Browns’ business relationships, see James B. Hedges, The Browns of Providence Plantations, Colonial Years (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952).

Brown Family Business Records, box 8, folder 3, John Carter Brown Library (hereafter cited JCBL), Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. Wendy A. Cooper, “The Furniture and Furnishings of John Brown, Merchant of Providence, 1736–1803,” (M.A. thesis, University of Delaware, Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, 1971), pp. 25–26. For the Nicholas Brown desk-and-bookcase, see Christie’s, The Magnificent Nicholas Brown Desk and Bookcase, New York, June 3, 1989, lot 100. For the John Brown desk-and-bookcase, see Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), pp. 339–44. For Moses Brown’s chest-on-chest, see Joseph K. Ott, “Some Rhode Island Furniture,” Antiques 107, no. 5 (May 1975): 942. For John Brown’s corner chairs, see Wendy A. Cooper, “The Purchase of Furniture and Furnishings by John Brown, Providence Merchant, Part I: 1760–1788,” Antiques 103, no. 2 (February 1973): 333–34, 338; and Sotheby Parke Bernet, Inc., The Lansdell K. Christie Collection of Notable American Furniture, New York, October 12, 1972, lot 49. Inventory of Joseph Brown, March 15, 1786, Providence Probate Archives, Will Book 7, pp. 6–26.

For more on Joseph Brown’s architectural work in Providence, see William H. Jordy and Christopher P. Monkhouse, Buildings on Paper: Rhode Island Architectural Drawings, 1825–1945 (Providence, R.I.: Brown University, 1982), pp. 5–8.

Moses Brown to Thomas Wagstaff, May 17, 1783; Edmund Townsend to Moses Brown, February 29, 1776; Edmund Townsend to Moses Brown, May 11, 1789, Moses Brown Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society (hereafter cited RIHS), Providence.

The Chad Browne Memorial, pp. 40–41. In his will, Joseph Brown appointed his brother Moses and Jabez Bowen co-executors of his estate. Providence Probate Court Archives, Will Book 7, p. 6. Hedges, The Browns of Providence, p. 312. Jules D. Prown, John Singleton Copley, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1966) 1: 209–10, figs. 322–323.

Carpenter, The Arts and Crafts of Newport, pp. 14–15. For the tea table ordered by Brown, see Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Winterthur Museum, 1997), pp. 238–40. A Newport chest-on-chest related to the one owned by Jabez and Sarah Bowen is illustrated in Sotheby Parke Bernet, Americana Week, Sale 3467, New York, January 24–27, 1973, lot 947. This chest-on-chest is now owned by the Newport Restoration Foundation and exhibited in the Whitehorne House in Newport.

The finials on the Jabez Bowen tall clock appear to be unique to American tall clocks, each consisting of a small, broad, turned mahogany urn-shaped finial (topped with a short twisted flame), which is sheathed with an openwork piece of metal in the form of four acanthus leaves. The mahogany finial was not originally made in two (or three) parts as many Rhode Island finials were, but rather it was sawn apart just beneath the cup of the urn sometime after fabrication, and the lower portion was drilled to receive a round pin that the upper part then slips onto. This segmentation allowed for the elaborate piece of foliate metalwork to be inserted between the upper and lower portions and then “folded” up around the urn. The acanthus leaf pattern and form of the metal structure is nearly identical to that seen on finials from English tall clocks and bracket clocks of the last quarter of the seventeenth century, though the metal content of those ornaments is not known. See Percy G. Dawson, et al., Early English Clocks (Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors Club, 1982), p. 178; and R. W. Symonds, Thomas Tompion, His Life and Work (London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1951) plate 1, p. 181. An analysis of the metal using X-ray flourescence spectroscopy revealed that it is primarily lead with minor amounts of tin, copper, and iron. It thus is quite different from traditional pewter, which is an alloy of tin and copper with smaller variable amounts of lead and other trace elements. The analysis of the two surface coatings (on both the metalwork and the flame tip of the urn) reveals the presence of gold (and bronze powder) in the first coating, and only bronze powder in the later coating. It is the opinion of the authors that these may not be the first finials placed on this tall clock, and that they may represent a nineteenth-century union of parts using c. 1700 English metalwork. We are indebted for these analyses to Marsha Bischel, Assistant Scientist, and Janice Carlson, Senior Scientist, of Winterthur Museum’s Analytical Laboratory. For a full discussion of the purchase and renovation of the Seril Dodge house, see Robert P. Emlen, “A Stylish House for the Widow Avis Brown: Architectural Statement and Social Position in Providence, 1791,” in Old Time New England, forthcoming. Accounts Artisans, Almy and Brown Unbound Papers, 1789–1793, RIHS. Seril Dodge is also mentioned several times in the estate accounts of Nicholas Brown (see “Estate of Nicholas Brown, Esq., Deceased In account Current with Brown, Benson, and Ives, ” box 24, folder 6, JCBL). William Almy appears to have been related to Benjamin Almy, whose signature appears on an interior drawer of a standard Newport-type desk dated 1748 (Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, New York, October 8, 1997, lot 57.) The Brown-Almy relationship may also represent another distant Brown-Townsend connection, since several Townsend men married Almy women in the early eighteenth century.

The Chad Browne Memorial, pp. 22–23 notes that Jeremiah Brown was lost at sea ca. 1740–1741, following which Waitstill married Captain George Corlis in 1745.

The architectural interiors of Joseph Brown’s 1774 house on South Main Street and John Brown’s 1788 mansion on Power Street had pitch-pediment chimneypieces and doorways. The William Russell house, built the same years as Nicholas Brown’s house on Main Street, was of comparable size and value as Brown’s and also had elaborate pitch-pediment interior features like the Joseph and John Brown houses. For images of these interiors, see American Architectural Building News 22 (1887), no. 610; The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1965), pp. xx, xxiii; and Donald C. Peirce and Hope Alswang, American Interiors: New England and the South (New York: Universe Books, 1983), pp. 22–27.

For more on the Ives house, see Barbara Snow, “Living with Antiques,” Antiques 87, no. 5 (May 1965): 580–85.

Richard M. Bayles, History of Providence County, Rhode Island, 2 vols. (New York: W.W. Preston, 1891): 1:500; Burgess Genealogy: Memorial of the Family of Thomas and Dorothy Burgess who were settled at Sandwich in the Plymouth Colony, in 1637 (Boston: Press of T.R. Marvin & Son, 1865), pp. 67–68. For the Stephen Gano–Brown relationship, see The Chad Browne Memorial, pp. 52–53.

Moses Brown Account Book, 1763–1836, p. 25, RIHS. Inventory of the Estate of Col. Amos Atwell, October 1, 1807, Will Book no. 10, pp. 188–95, Providence Probate Court Archives. Atwell’s inventory listed anvils and other tools associated with the blacksmith trade. His brick house and land on Weybosset Street were assessed at $3,000 in 1798 (Direct Tax, October 1, 1798, RIHS).

Eleanore Bradford Monahon, “The Rawson Family of Cabinetmakers in Providence, Rhode Island,” Antiques 118, no. 7 (July 1980): 133–36. Mendon, which is northwest of Providence in the Blackstone River Valley, was settled in the 1660s. Grindal Rawson’s great-grandfather, Edward Rawson, came to New England in 1636, eventually settling in Boston and becoming secretary of the colony. In 1685, Edward bought a 2000-acre tract of land from the Natick Indians in the area of Mendon. Grindal’s grandfather, Rev. Grindal Rawson (1659–1715), was born in Boston, graduated from Harvard, and settled in Mendon in 1684. Like the Rawsons, other Mendon families had Providence connections: Cook, Thayer, Aldrich, and Dorr. Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century there are continuous references to Mendon in various Brown correspondences, including a 1774 letter from Edward Rawson (probably Grindal’s brother) to Nicholas Brown. For more on the settlement of Mendon and its inhabitants, see Annals of the Town of Mendon from 1659 to 1880, compiled by John G. Metcalf (Providence, R.I.: E. L. Freeman, 1880). For a complete transcription of the 1756 Providence Cabinetmaker’s Agreement, see John Brown House Loan Exhibition, pp. 174–75. The five other cabinetmakers to sign the agreement were Gershom Carpenter, Benjamin Hunt, John Power, Phillip Potter, and Joseph Sweeting.

The account settling the estate of Nicholas Brown is in the Brown Family Business Records, box 24, folder 6, JCBL. Grindal Rawson’s first wife was Hannah Leavens of Killingly, Connecticut; his third wife was Zeruiah Harris (d. 1765). For more on the Rawson family, see E. B. Crane, The Rawson Family (Worcester, Mass.: By the family, 1875), p. 37.

Ott, “Lesser-Known Rhode Island Cabinetmakers,” pp. 1156–57. For more on Carlile, see Rowe, “John Carlile, Cabinetmaker,” pp. 310–11. Moses Brown Papers, Artisans Accounts, RIHS. Brown Family Business Records, box 13, folder 9, and box 1092, JCBL.

Will of John Carlile, Sr., 1795, Will Book 7, p. 846, Providence Probate Court Archives. Will of William Bowen, 1832, Will Book 13, pp. 577–80, Providence Probate Court Archives. For more on Carlile, see Garrett, “Providence Cabinetmakers, Chairmakers, Upholsterers, and Allied Craftsmen,” p. 516. The Welcome Arnold papers, including business ledgers, are in the JCBL.

Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (1901 edition), pp. 273–75. Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (1926 edition) 1:20–21, 246–248.

Two exceptions are the Bowen desk-and- bookcase and the Nicholas Brown chest-on-chest, both of which have beading around the drawers. Only a few Massachusetts and Connecticut blockfront pieces have lipped drawers. These include a ca. 1775 chest-on-chest from Norwich, Connecticut (William Voss Elder III and Jayne E. Stokes, American Furniture 1680–1880 [Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1987], no. 54), two ca. 1740 Boston-area dressing tables (Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, figs. 168–69), and a ca. 1750 Portsmouth, New Hampshire, chest of drawers (Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984], no. 17). A similar chest-on-chest owned by John Brown also has lipped drawers on the upper (straight-front) section and beaded drawers on the lower (blockfront) section. Cooper, “The Furniture and Furnishings of John Brown,” pp. 70–72, fig. 40.