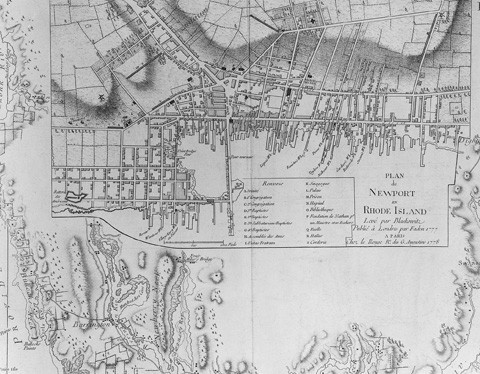

A Plan of the Town of Newport in Rhode Island, surveyed by Charles Blaskowitz. Engraving, 1777. (Courtesy, Newport Historical Society.)

Chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1775. Mahogany with chestnut. H. 34 1/2", W. 34", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; M. and M. Karolik Collection of Eighteenth-Century American Arts.)

Bureau dressing table by Edmund Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1765–1785. Mahogany with chestnut and yellow poplar. H. 33 5/8", W. 34 1/2", D. 18 7/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; M. and M. Karolik Collection of Eighteenth-Century American Arts.)

Desk-and-bookcase signed by Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1730–1750. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Sotheby's.)

“Mahogany Cabinet-Topped Block-Front Scrutoir, Messrs. Brown & Ives, Bankers, Providence, U.S.A., Circa 1775.” From Edwin Foley, The Book of Decorative Furniture: Its Form, Colour, and History, 2 vols. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 2: plate 61. (Courtesy, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Museum Library.)

High chest of drawers, possibly by John Townsend and Benjamin Baker, Newport, Rhode Island, 1750–1765. Mahogany with chestnut. H. 86", W. 39 1/2", D. 21". (Courtesy, Newport Restoration Foundation.)

Bureau table attributed to John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1785–1790. Mahogany with yellow poplar, chestnut, and white pine. H. 34 1/4", W. 37 1/8", D. 20 7/8". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery; Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

High chest of drawers by John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1759. Mahogany with chestnut, cottonwood, and white pine. H. 83 5/8", W. 40 1/4", D. 21". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery; bequest of Doris M. Brixey.) Inscribed “No. 28 /Made By /John Townsend /Newport /1759.”

Commode, Montreal area of Quebec, 1780–1790. Butternut with white pine. H. 34 1/4", W. 47 1/4", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Mrs. Dorothy Buhler in memory of Sarah M. Gilbert, gift of Estelle S. Frankfurter, and gift of John Gardner Green Estate, by exchange.)

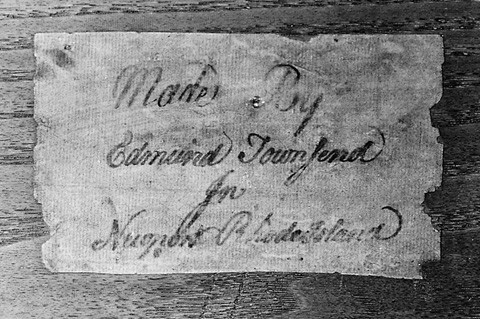

Detail of the label on the bureau table illustrated in fig. 3.

How do we account for the phenomenon of high-style Newport, Rhode Island, furniture from the last half of the eighteenth century? How did this smallest of the five major towns of colonial America (fig. 1) produce such an extraordinary body of furniture in a compressed period of time? Why are the objects (fig. 2) so consistent in design, construction, and aesthetic quality? Based on Newport’s history, one might hypothesize that Newport furniture would be a diverse, eclectic mixture of motifs and designs that reflected contributions from many places—a polyglot of designs stimulated by cosmopolitan trade, religious freedom, and Yankee entrepreneurship.

Although isolated physically, Newport merchants had extensive trade connections and privateering activities in both coastal and international waters, which gave the city the potential to bring in an enormous number of immigrant craftsmen and patrons, imported objects, and design sources, such as pattern books and builders’ guides. The salubrious climate—warmer in winter and cooler in summer than most of New England—made it a popular health resort for Southerners, especially Charlestonians, who traveled north to avoid the fevers and oppressive heat and humidity of South Carolina’s summers. Founded in 1639 by Roger Williams, a strong advocate of religious tolerance, the Rhode Island colony’s religious life made room not only for Congregationalists but also for Baptists, Sephardic Jews from Portugal and Spain, and Quakers from England. A prosperous economy in the years before the Revolution also attracted people seeking economic advantages.

Although these conditions would seem to foster diversity, the opposite occurred, as the large body of distinctive baroque furniture widely recognized today as the work of Newport chairmakers and cabinetmakers, primarily members of the intertwined Goddard and Townsend families, attests. Whatever the ultimate source of this phenomenon of American “exceptionalism”—whether it derived from the West Indies, from the Continent, from Asia, or from the furniture of other American cities—the fact remains that Rhode Island furniture of the 1740s to the 1790s is a cohesive body of work notable for its uniformity in design and high standard of craftsmanship.

In a quirky yet delightful essay published in the back of Edwin Hipkiss’s catalogue of the M. and M. Karolik Collection of Eighteenth-Century American Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, collector Maxim Karolik (1893–1963)—a part-time resident of Newport—waxed eloquently about the qualities of “Rhode Island School” furniture, which he regarded as “America’s Contribution to Craftsmanship.” Karolik saw the blockfront form, embellished with a carved shell, as the highest expression of the Rhode Island style. He compared its beautiful simplicity to the “rich pieces of the Philadelphia and the English Schools” by noting that “it would be like comparing a beautiful, unsophisticated girl, who does not even use lipstick, with a bejeweled lady dressed for a grand ball. The beauty of the first needs no embellishment at any time. The beauty of the second, when the jewels are off, may be scarcely recognizable.” Such forms were, according to Karolik, “in a class by themselves.” He backed up his opinion by acquiring many outstanding examples of Newport furniture from the 1750 to 1790 period, including J. Marsden Perry’s block-and-shell desk-and-bookcase, a labeled Edmund Townsend (1736–1811) bureau dressing table (fig. 3), a high chest now attributed to John Townsend (1732–1809), two chests of drawers, a cluster-column tea table, a pembroke table, a tall case clock, and a chair (thought at the time to be Newport).[1]

In his exaltation of Rhode Island objects, Karolik expressed the shared sentiments of the first few generations of collectors, curators, and students of American furniture. First identified as a recognizable regional phenomenon at the turn of the century, the “Rhode Island School” had been given a position of prominence in most publications of the 1920s and 1930s. Little has changed in the last sixty or seventy years. Rhode Island furniture, especially from Newport but also increasingly from Providence, is still a subject of great interest to students of American furniture. As we approach the end of the twentieth century, the subjective exaltation and objective interpretation of Rhode Island furniture remain of prime interest and concern in the field of American furniture history. The essays in this volume speak to its appeal to historians and curators, and the recent sale at auction of a newly discovered Newport desk-and-bookcase (fig. 4) signed by Christopher Townsend (1701–1787) for more than eight million dollars amply demonstrates its continued appeal to collectors.[2]

Nearly every American furniture historian has written about Newport furniture, occasionally brilliantly but more often repetitively. Although it is impossible to do justice to every author on the subject, nor to take note of every discovery along the way, an attempt has been made in this essay to summarize the general interpretive thrusts of nearly one hundred years of publications.

The Beginnings: The Apotheosis of John Goddard

and the Discovery of John Townsend

The first references to Newport furniture from an historical perspective appeared in the nineteenth century, as reported by modern historians Jeanne Vibert Sloane and Ralph Carpenter. As early as 1849, Newport historian Thomas Hornsby called attention to the city’s cabinetmaking trade in an article in the Newport Daily Advertiser. Hornsby mentioned craftsmen David Huntington, Benjamin Baker, and Benjamin Peabody by name and noted that an active export trade was carried on with New York, the West Indies, and Surinam. George Champlin Mason, in his Reminiscences of Newport (1884), reiterated Hornsby’s article nearly verbatim but added considerable detail and introduced the Goddard and Townsend names apparently for the first time. He also itemized the forms that they made and noted that John Goddard (1723/24–1785) owned a copy of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director.[3]

Although noted by local antiquarians, Newport furniture per se failed to capture the attention of some of the first writers on American furniture, including Irving Whitall Lyon, Alvan Crocker Nye, Esther Singleton, E. E. Solderholtz, Newton Elwell, and others. The earliest furniture historians to call attention to the subject, albeit briefly, were Luke Vincent Lockwood (1872–1951) in the first edition of Colonial Furniture in America, published in December 1901, and Frances Clary Morse in Furniture of the Olden Time, published in 1902. Each book illustrated Newport case pieces and suggested that they were probably made there, mainly because of their history of ownership in the Brown family. Lockwood repeated the same ideas in his catalogue The Pendleton Collection, published by the Rhode Island School of Design in 1904. Lockwood apparently continued his research, for by 1913 when the second edition of his Colonial Furniture survey was published, he was able to quote the now-famous 1763 letter from John Goddard to Moses Brown, with its reference to “a Cheston Chest of Drawers & sweld front which are costly as well as ornimental,” which Lockwood and all subsequent writers have interpreted as a reference to the blockfront form. Lockwood used this source to attribute all Newport block-and-shell pieces to John Goddard, and he illustrated a number of objects that he described as “the pure Rhode Island type.” He had an extensive section on the block-and-shell desk-and-bookcases, which he concluded “were made in Newport by John Goddard. . . . There are several cabinet-top scrutoires of this type known, and they are probably as fine pieces of cabinet work as are found in the country and differ only in minor details.”[4]

Not everyone, however, immediately picked up on Lockwood’s research. Walter A. Dyer, in his popular survey of Early American Craftsmen, published by the Century Company in 1915, acknowledged that “Newport homes contained some fine furniture” and that the blockfront form originated in New England, but he was silent on the Goddards and Townsends. In 1920, Gardner Teall illustrated a desk-and-bookcase at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as the frontispiece to his Pleasures of Collecting. Although he correctly identified it as an “Early American Block-Front Cabinet-Top, Rhode Island Style Desk, 1750–1775,” he made no additional reference to the object except to note that “in American desks . . . we find the block-front to have been very popular.” Edwin Foley, in his massive two-volume Book of Decorative Furniture (1912), illustrated the Ives and Brown family desk-and-bookcase (fig. 5) but noted that it is “essentially British” and that, except for its documented history in the Brown family, “one would not hesitate to regard the scrutoir as an imported piece.”[5]

The 1920s were the key decade in establishing Newport furniture as a principal text in the canon of American furniture studies. By the time Lockwood published the third edition of Colonial Furniture in 1926, he was able to add more Goddard-type pieces to the record in his supplementary information, and he also incorporated a substantial body of material on John Townsend and other members of the Goddard-Townsend extended family. In part Lockwood was building on work contained in the pages of Antiques, which began publication in January of 1922. Newport and Rhode Island furniture figured prominently in many articles published during the first few years of that magazine. The column titled “Little-Known Masterpieces” featured block-and-shell pieces in January and September of 1922, and Walter A. Dyer, making up for lost ground, published an extensive monograph on “John Goddard and His Block-Fronts” in May 1922. Dyer made use of all previous secondary sources, and he also relied upon Duncan A. Hazard, the registrar of deeds in Newport, and Mrs. William W. Covell of Newport, a Goddard descendant, for primary source material. In February 1923, Malcolm A. Norton responded to Dyer’s article and its emphasis on Goddard with “More Light on the Block-Front.” Norton’s article, which emphasized John Townsend and his work, questioned whether Goddard was the originator of the blockfront form. In the same Antiques issue, an author known as “Bondome” added to the controversy by suggesting that there were both German and English prototypes for the blockfront. Eight months later, English furniture historian Herbert Cescinsky, in an article commissioned by Antiques, argued that the blockfront was a sure indication of Dutch influence.[6]

Much of this preliminary work, somewhat scattered and fragmentary, was assembled and enhanced in two monographs that mark the end phase of these first tentative steps in the scholarly study of Newport furniture. Norman M. Isham, an architectural historian, brought together a large amount of biographical material on “John Goddard and His Work” for an April 1927 article in the Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design. Issued in conjunction with an exhibition, this article retained the Goddard-only emphasis, citing him as “a single master craftsman” who was “the finest of all the New England cabinet-makers and one of the two best in all colonial America.” Isham carefully footnoted his article and described in detail the ornament and construction of major Newport pieces, including the Lisle family desk-and-bookcase at the Rhode Island School of Design. In an answering salvo, Charles Over Cornelius, an associate curator of decorative arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, published a monograph in the first volume of Metropolitan Museum Studies, issued in 1928–1929, in which he illustrated and discussed three pieces of John Townsend labeled furniture in the Metropolitan’s collection. As with Isham’s article, Cornelius’s work on Townsend is rich in detail and heavily annotated. He offered the theory that the source of the obvious similarity between the shells on both Goddard and Townsend pieces is “that they must have been made by the same hand.” “No doubt,” he suggested, “there was some carver, employed at times by both of them, who did this specialized work.” Without openly questioning Isham’s research, Cornelius decorously but incontrovertibly established Townsend as being of equal significance in the Newport picture.[7]

From this point on, the twin stars of Goddard and Townsend were firmly placed in the firmament of American furniture studies, and no survey of the subject could omit giving the Rhode Island school a prominent position. Wallace Nutting’s Furniture Treasury, published in two volumes in 1928 and with a third volume issued in 1933, illustrated numerous Goddard-Townsend pieces and spoke glowingly of their work. A seventeen-page biographical essay on the Goddard family in volume three, as well as a shorter entry on the Townsends, summarized a vast amount of genealogical detail for the general public, reprinted John Goddard’s inventory and other documents, and reproduced several original bills of sale and other source material in facsimile. Thus canonized by the Furniture Treasury—probably the most popular and frequently reprinted book ever published on American furniture—the Rhode Island school’s popularity was ensured, and both Goddard and Townsend became household names in the same select category as William Savery, Benjamin Randolph, Duncan Phyfe, Samuel McIntire, and a few others.[8]

At the Rhode Island Tercentenary Exhibition at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1936, the section on furniture was titled “The Goddards and the Townsends.” Although Elizabeth T. Casey’s catalogue essay gives preeminence to John Goddard, craftsmen of both surnames are mentioned in a manner that has largely been followed to the present. In 1947 Joseph Downs, then curator of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, summarized the literature in an Antiques article titled “The Furniture of Goddard and Townsend,” a superb historiographic essay that also brought to light several “new” pieces that had been displayed that year in an exhibition at the Colony House in Newport.[9]

Checklists and Genealogy: Compiling the Biographical Record

To quote English Parliamentary historian Sir Lewis B. Namier, much research begins with “finding out who the guys were.” Nearly all the aforementioned authors, especially Lockwood, Isham, Dyer, and Cornelius, concerned themselves to a degree with compiling biographies of John Goddard, Job Townsend (1699–1765), John Townsend, and, to a much lesser extent, other members of their extended cabinetmaking families. This process has been a long and slow one of teasing information from limited primary sources, and most authors have added a few precious facts to the record along the way, building upon the work of those who have come before and, in turn, pointing the way for others to follow.

With her unparalleled mastery of primary sources, Mabel Munson Swan published the first major checklist of Newport furniture makers in Antiques in 1946. Her two-part article, issued in April and May of that year, along with her codicil on “John Goddard’s Sons” published in Antiques in 1950, has been a starting point for a number of later compilations in the same vein. Ralph Carpenter’s biographical sketches and lists in The Arts and Crafts of Newport (1954) firmly placed in the record a wealth of information on many makers and marked a milestone in the study of Newport work. Much of the material in Swan and in Carpenter was reiterated in the sketches included by Ethel Hall Bjerkoe in her Cabinetmakers of America (1957), a more widely available source. Wendell D. Garrett published a corrected checklist of Newport cabinetmakers in Antiques in June 1958, “Random Biographical Notes” in September 1968, and additional biographical and bibliographical notes in May 1982. Other authors, including Joseph K. Ott, have expanded our knowledge in numerous articles in Antiques and Rhode Island History during the 1960s and later.[10]

Jeanne Vibert Sloane included a checklist of sixty Newport joiners and cabinetmakers working during the 1745 to 1775 period in her article, “John Cahoone and the Newport Furniture Industry,” published in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno Forman (1987). In a 1991 Winterthur Portfolio article, Margaretta Lovell compiled four useful genealogical charts of the extended Goddard-Townsend family and also made reference to more than one hundred Newport craftsmen in the furniture trades in the eighteenth century. Although there is precious little primary evidence available—only a few letters and bills, a modest number of related account books, and vital statistics and probate documents—this steady accumulation of the genealogical and biographical material has created a much fuller picture of the cabinetmaking trade in Newport.[11]

Although much attention has been focused on the Goddards and Townsends, the identification of works associated with lesser-known craftsmen such as Benjamin Baker (fig. 6) also has increased our understanding of the craft system as a whole. Throughout the century, many articles and collection catalogues, such as those by Wallace Nutting, Henry Hawley, Joseph K. Ott, Stanley Stone, and others, have added both biographical information and newly discovered objects to the fold, while also reinterpreting and analyzing pieces that have been known for some time. Catalogues of the collection at the Rhode Island School of Design by Christopher Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, of the colonial furniture owned by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities by Brock Jobe, Myrna Kaye, and Philip Zea, and of the Queen Anne and Chippendale furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Morrison H. Heckscher contain valuable entries on many important examples of Rhode Island furniture. Wendy A. Cooper’s 1980 exhibition titled “In Praise of America” summarized previous research in a skillful manner and contributed additional objects to the record.[12]

Attribution and Authentication: The Connoisseurship Path

Naturally, the identification of Newport furniture on the basis of style, the delineation of its characteristics, and its attribution to specific makers has been a principal concern of nearly every writer on Newport furniture. Whereas the earliest work emphasized John Goddard, scholars soon added John Townsend and then, as research progressed, attributed objects to other members of the family and to other makers, such as the high chest by Benjamin Baker (fig. 6).

A major event in establishing a definitive Newport school was the landmark loan exhibition held at the Nichols-Wanton-Hunter house in Newport in 1953 under the auspices of the Preservation Society of Newport County. Following on the heels of The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island, by Antoinette F. Downing and Vincent J. Scully, Jr., published by the Preservation Society in 1952, this exhibition of furniture, silver, and paintings of Newport origin resulted in Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr.’s, 1954 publication, The Arts and Crafts of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640–1820, in a limited edition of two thousand copies. Carpenter laid out a list of fifteen design features and ten construction techniques “characteristic . . . of the Townsend-Goddard furniture,” recorded a checklist of more than sixty Newport joiners and cabinetmakers, and compiled a list of some thirty examples of documented Newport furniture. For the first time, text and illustrations concerning a substantial body of related material—about eighty pieces, many of them key “type specimens”—were brought together in one source. The checklists of characteristic details and diagnostic features, such as undercut talons, fine dovetailing and thin drawer sides, “detachable” legs on high chests, and many others, provided collectors with useful yardsticks for examining new pieces. Nearly fifty years later, this catalogue remains a starting point for research.[13]

By the summer of 1965, enough new material had surfaced to warrant a second major loan exhibition. “The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture, Including Some Notable Portraits, Chinese Export Porcelain & Other Items” was held at the headquarters of the Rhode Island Historical Society in Providence, organized by Joseph K. Ott. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition included entries on ninety-three pieces of furniture, encompassing Providence as well as Newport work, added an appendix on Providence account books, and reprinted Providence cabinetmakers’ agreements of 1756 and 1757. Along with Carpenter’s book, Ott’s catalogue continues to be a significant reference work.[14]

Although advances were made in the 1970s, particularly with regard to the origins of the blockfront form, the 1980s witnessed some remarkable progress in the ongoing attempt to link individual pieces with a maker’s name. In 1981 and 1982, Liza and Michael Moses and Morrison H. Heckscher of the Metropolitan Museum of Art published separate articles in Antiques concerning the attribution of Newport work. The Moseses first outlined their system of “authenticating” John Townsend’s “later tables” in May 1981, following a year later with a similiar study examining both Townsend’s and John Goddard’s tables in the “Queen Anne” and “Chippendale” styles. Heckscher’s article in the same May 1982 issue examined “John Townsend’s Block-and-Shell Furniture” through a careful study based on about thirty known examples of Townsend’s work. These heavily illustrated articles were made possible because there was a large homogeneous body of labeled, signed, and otherwise documented Townsend furniture that allowed for the development of norms and profiles of typical features. The establishment of these norms and profiles has allowed scholars to look at an unmarked piece, such as a bureau table in the Yale University Art Gallery (fig. 7), and attribute it to Townsend with a high degree of certainty.[15]

Building on this work, Michael Moses published Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards in 1984. Co-sponsored by the noted antiques firm of Israel Sack, Inc., who supplied captions for the illustrations, this book set forth a three-point methodology for “authenticating” Newport work done between 1740 and 1790. Using construction, ornament, and documentation, this system for classifying furniture was based on the degree of congruence between an unknown work and these three areas. If the unknown piece related well to one area, it was thought to be “associated with” the craftsman in question; if two areas matched up well, it was said to be “authenticated to”; and if there was strong evidence on all three aspects, then the attribution was upgraded to “made by” the particular craftsman. Separate chapters or sections were devoted to John Goddard, John Townsend, Job Townsend, Edmund Townsend, Thomas Townsend, Daniel Goddard, and others. Thirteen appendices provided genealogical data, summaries of account books, and much other information. Along with Benjamin A. Hewitt’s computer-assisted study of federal period card tables, Moses’s work on Newport remains one of the most detailed and systematic attempts to link an object with its maker.[16]

The efficacy of the “Moses method” was demonstrated to this author during the examination of a high chest (fig. 8) in the mid-1980s. This high chest had been exhibited at the landmark Girl Scouts Exhibition in 1929 and was bequeathed to Yale University. Moses, who had known the piece through photographs, learned of its arrival at Yale and soon arrived to examine the high chest in person. He predicted with uncanny accuracy each feature that would be found as the drawers were removed, the upper and lower case separated, and so forth. He attributed it to John Townsend and dated it in the late 1750s. As the piece was being reassembled, the last owner’s modern shelf paper, thumbtacked in all the drawers, was removed, and there was an inscription in one of the upper case drawers reading “No. 28 / Made By / John Townsend / Newport / 1759.” Although the “Moses method” may not be as effective in attributing works to every Newport maker, its usefulness in the case of John Townsend was clearly demonstrated in this case.[17]

In recent years, Leigh Keno, Joan Barzilay Freund, and Alan Miller have reexamined Boston seating furniture in detail and, in the process, have altered our understanding of early Newport chairs. Through a study of shipping records, account books, and other documents, as well as of the furniture itself, they concluded that the “material evidence strongly suggests that much of the seating used in Rhode Island before 1750 originated in Boston.” They also suggested that Newport chairs made after 1750 largely manifest “interpretations of Boston designs.” There thus has been an increasing emphasis on Boston as the source for much that we see in Newport work, although it is always conceded that Newport objects invariably speak with a distinctive accent.[18]

The Conundrum of the Block-and-Shell Design

From the very beginning, the blockfront form—and especially the block-and-shell variation—has been recognized as a hallmark of Newport design. Most early writers were willing to state that both the blockfront and the block-and-shell were uniquely American contributions to design. Lockwood, in his second edition of Colonial Furniture in America (1913), wrote that “the origin of the [blockfront] style is not known, but it is probably American. We find practically nothing in England or on the Continent which suggests it, except that one or two pieces have been found in England, but these could have come from America with some Tory family at the time of the Revolution.” Most writers noted that the blockfront was used throughout New England, and most, with a few exceptions, cite Newport as its place of origin. The common perception was voiced by Carl Dreppard in an entry on “Block-Front Furniture” in his Primer of American Antiques (1944). European and American connoisseurs agree, he said, that the blockfront “is the handsomest of American productions and . . . apparently . . . is original with us.” He declared that it was the “brain child” of John Goddard and John Townsend. Dreppard did note that some people believed that the origins of the blockfront lay in the Netherlands, Spain, or England, but he thought that the ultimate source, if there was such a source, was China. On the whole, however, Dreppard and many others saw the blockfront as distinctly American.[19]

A few writers did have suspicions about the originality of the blockfront. “Bondome” argued in Antiques in February 1923 that there might be both German and English prototypes, and Herbert Cescinsky in October 1923 noted that, in his mind, the blockfront always indicated Dutch influence. A major theory was floated in Nutting’s 1928 edition of the Furniture Treasury when he published a photograph, supplied to him by Hartford collector William B. Goodwin, of a large mahogany case piece in the cathedral in Havana, Cuba. “The statement has been made,” Nutting observed, “that this great piece . . . may possibly have suggested a block front as made in Newport.” Nutting further theorized that John Townsend may have seen this piece while visiting Cuba to purchase mahogany. Despite the lack of documentation for the piece in Havana, the absence of similar pieces, and the highly conjectural theory that Townsend actually saw it, the West Indies were cited occasionally as a possible source for the baroque blockfront forms made in North America.[20]

For many years, the blockfront and the block-and-shell design remained largely understood as uniquely American concepts originating in Newport. Although most writers conceded that Italian, French, Dutch, German, English, West Indies, or even Chinese influence might be the ultimate source for these designs, most writers seemed comfortable accepting them as an example of American exceptionalism. In the 1970s, some new theories were advanced that refined our understanding of the blockfront form. In 1971, R. Peter Mooz of the Winterthur Museum published a short study in Antiques that persuasively argued that the American origin of the blockfront form was Boston, not Newport. Mooz based his conclusions on a blockfront desk-and-bookcase in the Winterthur collection, which was signed by the makers Job Coit and Job Coit, Jr., of Boston and dated 1738, making it about twenty years earlier than related Newport pieces. Mooz was also the first to analyze the sources of Newport ornament from an art historical perspective. He suggested that the Newport shell was a later version of the shells found on Boston pieces like the Coit desk-and-bookcase, and he found other Newport details depicted in English design books, such as John Vardy’s Some Designs of Inigo Jones and William Kent (1744). Significantly, he argued that the source of the ornament on the Newport block-and-shell pieces might be found in “the engravings of the famous French designers Jean Le Pautre, Jean Berain, and André Charles Boulle,” and he illustrated several plates suggestive of the convex shells, C-scrolls, cup finials, and other details found on Newport work. Although the precise means of stylistic transmission was not identified, Mooz hypothesized that Daniel Ayrault, a Newport bookseller of French descent, might have been a conduit. He concluded: “The form was based on blocking developed in Boston and the ornament may have been taken from French designs, but the creative genius that combined these elements and perfected the style was Newport’s alone.”[21]

Margaretta Lovell, in a paper given at a 1972 conference sponsored by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts and published two years later, expanded upon Mooz’s thesis and carefully examined the differences between Massachusetts and Rhode Island blockfront design and construction. Lovell again gave the nod to Massachusetts as the place of origin for the design but also noted that the flow of designs reversed later in the century, when Newport influenced some Boston objects and many Salem blockfront pieces. Mercantile and trade networks were important elements in this ebb and flow of influences, as were the “close connections maintained among Quakers in eighteenth-century New England,” specifically among the Newport Quaker craftsmen. Lovell noted that “nothing precisely like the style of blocking as it is known in this country has been found abroad,” although “undulating facades” of various types are found on French, German, and Spanish furniture. “England produced some flatly blocked casepieces which exhibit a restraint and understatement of baroque movement similar to American blocking practice,” and Lovell illustrated several potential prototypes.[22]

The discussion of the origins of the block-and-shell design were summarized in John T. Kirk’s American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830, published in 1982. Kirk noted that “Newport created the most original high-style furniture” and that the block-and-shell “takes its basic form from England . . . but with blocking and shells from the continent.” “Searching for the American form of blocked furniture in an original English example proved fruitless,” Kirk stated, and he, like Mooz, cited possible relationships with Parisian forms of the kind associated with Boulle and with ornament of the type associated with Jean Berain. “Deep blocking was made in Scandinavia, Germany, France, and Italy,” and “German pieces were often dramatically blocked,” which he illustrated with a desk-and-bookcase design from 1740 to 1750 by J. G. König of Augsburg. Despite these potential sources for the “general precepts” of the Newport block-and-shell, Kirk argued that Newport’s “manner of handling form, surface, and decoration was original, and included a conscious rejection of the prevailing London rococo style.” “The best Newport cabinetmakers,” according to Kirk, “consciously risked independence, and because of their superior abilities achieved a new, important artistic statement.”[23]

A small group of Newport case pieces, with canted front corners and serpentine fronts, has been seen as a manifestation of the “American response to French taste” in Newport. A key piece of the group is a large chest of drawers at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which, according to family tradition, was made for French sea captain Pierre Simon (anglicized as Peter Simon) who lived in Newport and had a house on Bridge Street. In form and size, this piece and others in the group relate to work done by contemporary French-Canadian furniture makers, such as a chest of drawers (or commode) also at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, made about 1780 in the province of Quebec (fig. 9). This chest has an undulating facade in the cross-bow, or arbalête, shape and also has feet undercut in the Rhode Island manner. Although no direct lines between Montreal and Newport can be drawn, furniture makers in each town were probably working from the same ultimate design source.[24]

Process and Profits: Economic Interpretations

From the very beginning, a branch of scholarship on Newport furniture has been concerned with the export trade that comprised such a large portion of Newport cabinetmakers’ business. The first nineteenth-century antiquarians noted this trade in their reminiscences, and occasional articles, including those by Mabel Munson Swan in 1949, brought to light a body of facts concerning the export trade from Newport and other New England ports. In 1955, noted historian Carl F. Bridenbaugh aptly summarized the Newport cabinetmaking trade: “Newport craftsmen concentrated on making several export items of high quality and originality of design, and in so doing earned a wide reputation. The Townsends, skilled cabinetmakers, who, with the Goddards, their kinsmen by marriage, evolved the impressive block of ‘Swell’d front’ chests and desks, nevertheless expended most of their skills in fashioning cheap furniture for sea captains to take on consignment to the Southern or island colonies.”[25]

The first real breakthrough in understanding and delineating the importance of this trade for Newport workmanship came when Jeanne Vibert Sloane published her 1987 article on Newport cabinetmaker John Cahoone. Sloane’s article, based on an in-depth analysis of Cahoone’s daybook from 1749 to 1760, brilliantly outlined the dual nature of the Newport furniture trade. Whereas earlier furniture scholars focused on the “highly embellished, labor-intensive cabinetwork” the Townsends and Goddards made for wealthy local patrons from the Brown, Hopkins, Redwood, Bowen, Wanton, Gibbs, and other families, Sloane emphasized the common objects, many made for export, that formed the bulk of production and “were a manufactured commodity vital to Newport’s trade economy.” Newport furniture makers acted in an independent, speculative, entrepreneurial manner fostered by Newport’s religious tolerance. “The Rhode Island Antinomians,” she argued, “endorsed the freedom of the individual to achieve prosperity through industry.” The demands of the export trade necessitated standardization, consistency, and high-quality production, all “modern” characteristics that foreshadowed the development of nineteenth-century capitalism and industrialism. Although eighteenth-century social structure kept artisans from becoming “fully independent and competitive,” these vigorous craftsmen presaged the “professional behavior and personal aspirations of enterprising Americans of the Early Republic.”[26]

In 1991, Margaretta Lovell expanded upon this theme in her richly textured Winterthur Portfolio article, “‘Such Furniture As Will Be Most Profitable’: The Business of Cabinetmaking in Eighteenth-Century Newport.” Building upon and amplifying Sloane’s analysis of Cahoone, and drawing on modern scholarship in diverse fields including anthropology and consumerism, Lovell looked at several key nodes in Newport society: community (principally family), craft, customers, and markets. She, too, noted the importance of the export trade and the dual nature of the cabinetmaking business, the importance of the export system in determining the repetitive, systematic look of Newport furniture, and the importance of aesthetics as part of the picture. Taken together, Sloane and Lovell provide the most rounded look at Newport furniture from an historical and cultural perspective; they are an essential place to begin if one wants to understand Newport furniture rather than just recognize it. All future work along these lines will build upon the framework they established.[27]

The Newport Identity

Of course, telling the story of Newport furniture is an ongoing endeavor, as the essays in this volume attest, and our opinions about its unique qualities may still be undermined if new prototypes emerge. Much has been accomplished, but there are still areas of study that need to be tackled. Perhaps Kirk and others have not found parallel objects in England because they have been looking in London rather than in provincial cities. The search may have been further hampered because English scholars have focused on two extremes—high-style London work on the one hand and rural, or vernacular, work on the other. As English scholars learn more about furniture from Britain’s smaller urban centers, American scholars may learn more about furniture from the colonies. New discoveries will also come about from returning to the primary sources, especially the furniture, again and again. In the last fifteen years or so, for example, thorough examinations have revealed previously unknown secret compartments in Rhode Island desk-and-bookcases and signatures on well-known pieces. Fortunately for scholars, Newport pieces keep coming to light with a fair degree of regularity. Another avenue of important research will be to focus on the purchasers of Newport furniture. The attitudes and values of these patrons clearly are key elements in understanding the look of the furniture. As with so many areas of American decorative arts, we lack a single, comprehensive book on Newport furniture that embraces all that has been done to date and that integrates furniture history with architectural history—a crucial undertaking for Newport, where architect Peter Harrison was such a key figure in the story of the built environment[28]

There is little question that Newport furniture made in the 1750 to 1790 period forms a cohesive group. Although Michael Moses and others can associate specific objects with individual makers, it is far more interesting that Newport objects are more similar than they are different, even though they fall into a relatively plain class (for export) and an embellished class (for wealthy local patrons). What seems less well understood are the causes of this similarity, its importance in understanding Newport as a whole, and the degree to which this formation of identity was intentional.

Students of American furniture struggle with these questions when interpreting all the various regional schools of early American cabinetmaking. Charles F. Montgomery, in a 1976 article, emphasized the importance of both regional preferences (largely culture or patron driven) and regional characteristics (often craft derived). Philip D. Zimmerman, in a 1988 essay on the nature of regional studies in American furniture, pinpointed three categories of evidence that must be examined in any regional study: geographical, social and economic, and cultural characteristics. Over the past century, scholars of Newport furniture have addressed all these factors, beginning with the “John Goddard-as-genius” thesis and concluding with the sophisticated, structuralist economic and social explanations of Sloane and Lovell. The variety of viewpoints brought to bear on Rhode Island furniture can be seen in an unusual article prepared by a graduate class at Boston University conducted by John T. Kirk. For this article, some twenty-six scholars in different fields were presented with basic information about a desk-and-bookcase owned originally by John Brown and now at the Yale University Art Gallery and asked to respond to it from their own perspectives. Although the answers, which were very unevenly recorded and presented, usually revealed more about the preoccupations and attitudes of the respondents than they did about the object, it was fascinating to see the wide range of interpretations that a single object evoked.[29]

Were the people of Newport—patrons and craftsmen alike—striving to create what, in the twentieth century, might be considered a corporate or brand identity? A tentative answer to this question is yes, and it can be inferred from several fragments of evidence. First, many pieces of Newport furniture are labeled, signed, or otherwise bear an indication of its maker and place of manufacture (fig. 10). As Lovell indicated, such markings were not merely a matter of pride—these labels were “active agents of trade,” otherwise known as advertising or proto-advertising. Similarly, some Newport construction practices, like detachable legs on high chests, were primarily “trade-enabling innovations.” Most significantly, Lovell suggested that the look of Newport furniture, its baroque “Hogarthian Beauty,” was key to the entire enterprise. She noted, “The most powerful ingredient in their continued success was aesthetic power,” and she also observed that “widespread product recognition would develop from style constancy.”[30]

Lovell emphasized the economic motives behind Newport consistency—the drive to make “such Furniture as will be most profitable.” One could also, however, enter the realm of speculation and wonder to what degree this development of a consistent artifactual identity was a conscious choice that reflected thoughts and ideas outside the arena of furniture production itself. The four original towns of Rhode Island—Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick—were “Communities of Outcasts,” “all founded so that their inhabitants would not have to live with other people.” Historians have noted that Rhode Islanders took “irreverent pride in being independent, different, and constantly beating the odds.” Historical geographer D. W. Meinig concluded that Newport was “a general community that lived quite autonomously within New England.” Their drive for independence led Rhode Islanders to the forefront in fostering and fomenting the American Revolution, but it also led many of them to seek autonomy from the other colonies after the Revolution. Rhode Island even refused to participate actively in the War of 1812. The spirit of self-reliance runs deep and strong in the Ocean State.[31]

An underlying theme of Rhode Island’s economic history in the eighteenth century was antagonism toward the colony of Massachusetts Bay. In the same way that seventeenth-century Rhode Islanders wished to escape the theocracy of the Massachusetts Puritans, eighteenth-century Newport merchants wanted desperately to escape economic domination by their rivals in Boston. Governor Samuel Cranston (1659–1727), a key figure in the growth of Rhode Island, promoted increased agricultural exports as a means of improving Newport’s commerce, and thus he set the stage for the growth of the mercantile economy. Fisheries, the sugar trade, and, unfortunately, the slave trade were the principal sources of wealth. The colony issued its own currency as early as 1710 and manipulated it in an attempt to gain advantage over Massachusetts money, instituted port fees against outsiders, taxed goods sold by outsiders, and took other steps designed to beat the competition from the Bay colony. The ultimate goal was to establish direct trade with London, Bristol, and other ports. In a passage noted by several scholars, Newport merchant John Banister, who hoped to establish a direct trade from Newport to London, wrote in 1739 that all Rhode Island people “seeme fully Convinc’d [that direct trade] is the only method to make them selves Independent of the [Massachusetts] Bay government, to whom they have a mortal aversion.” Hatred and aversion can be great motivators; thus, even as Newport furniture makers used the Massachusetts blockfront as a starting point, they may have wished to make their own products distinctly different from that of their rivals.[32]

Clearly Newport patrons and craftsmen ignored the latest fashions. Nearly every scholar has observed that Newport furniture makers consciously rejected the asymmetry and ornamentation of the rococo style and continued to produce basically baroque furniture long after it had gone out of style elsewhere. As Charles Montgomery noted, “the Rhode Island block-and-shell furniture was a restatement, really a new statement, of the Queen Anne style aesthetic at the height of the Chippendale era in America.” Although John Goddard is thought to have owned a copy of Chippendale’s Director, when John Norman attempted to publish an American version in Philadelphia in the 1770s, with drawings by John Folwell, he was unable to obtain any advance subscribers from Newport or New England, although booksellers and merchants in Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, and South Carolina signed on.[33]

A recent book published by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, titled Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, included an essay by Greg Dening who noted that early Americans lived in a state of liminality—of thresholds, of ambivalence, of edginess—and that a constant struggle for self-identity and self-definition took place. “Human beings make great attempts to leave their signatures on life—in the children they bear, in the constitutions they write, in the things they build.” Newport furniture is surely one of the great “signatures” of eighteenth-century America, an extraordinarily beautiful means of defining a sense of self for a community. Whether this act was conscious or not is probably unknowable. What is knowable is that, in the eighteenth century, furniture was an integral part of the life, especially the social and economic life, of communities large and small. Edward S. Cooke, Jr., demonstrated this fact in his work on the furniture of Newtown and Woodbury, Connecticut. Any understanding or interpretation of these communities by historians that ignores the furniture or other decorative arts made there is incomplete and, in the case of Newport, woefully incomplete. The study of Newport furniture is not merely an exercise in antiquarianism or filiopietism; nor is it a self-absorbed avocation of interest only to a small group of affluent collectors or a self-indulgent exercise in materialism and aestheticism by curators—although it has been all of these things. Rather, it is central to any serious historical study of the Newport community as a whole.[34]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Luke Beckerdite for this opportunity to review the literature on Newport and to Jonathan L. Fairbanks and my wife, Barbara McLean Ward, of the Moffatt-Ladd House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for their critical readings of drafts of this essay. As a review essay, this article is based on the work of many authors, both past and present, whose labors I hereby acknowledge and applaud.

Maxim Karolik in Edwin J. Hipkiss, Eighteenth-Century American Arts: The M. and M. Karolik Collection (Cambridge: Harvard University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1941), pp. 350–53. The Rhode Island pieces in the Karolik collection include cat. nos. 19, 20, 32, 36, 37, 38, 59, 66, 67 (a federal period table by Holmes Weaver), 80, 101 (a federal period chair), and 125.

For the desk-and-bookcase, see Sotheby’s, Important Americana: Furniture and Folk Art, New York, January 16–17, 1999, lot 704, and such attendant publicity as Thatcher Freund, “Oh, The Tales a Secretary Could Tell!” New York Times, February 11, 1999.

Thomas Hornsby, “Newport, Past and Present,” Newport Daily Advertiser, December 8, 1849, as quoted in Jeanne Vibert Sloane, “John Cahoone and the Newport Furniture Industry,” in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno M. Forman (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), p. 92. This book was also published as volume 72, serial number 259 of Old-Time New England. George Champlin Mason, Reminiscences of Newport (1884), as quoted in Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., The Arts and Crafts of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640–1820 (Newport: Preservation Society of Newport County, 1954), p. 9. The copy of Chippendale’s Director thought to have been owned by John Goddard is in the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (31.995). It is a copy of the third edition (1762) and is missing the title page as well as plates 183 and 200. “Thomas Goddard” is written in a very small, crabbed hand on the inside back cover. There are a few stray pencil marks in the volume, none of them of any great consequence. Maxim Karolik purchased the book from Duncan A. Hazard of Newport in 1929. Hazard wrote in a letter to Edwin Hipkiss of October 29, 1929, preserved with the book, that “This Chippendale book belonged to John Goddard the celebrated cabinet-maker of Newport in the eighteenth century. John Goddard used this book.” Hazard stated that he had acquired the book from “an old lady in Newport, Miss Goffe,” whose father was a cabinetmaker in Newport ca. 1850. This Mr. Goffe “purchased the book . . . at an auction of the effects of one of the descendants of John Goddard.” Hazard also stated that “Later I had Albert W. Goddard the great-grandson of John Goddard identify this book. He was about 82 years of age and in good health and sound mind and immediately recognised the book and said it was the one his great-grandfather owned and used, and he [was] pleased to see it once more.”

Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902), pp. 272, 275. This book was published in 1901 but had the date 1902 on its title page. Modern scholars usually give Lockwood credit for being the first. Frances Clary Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time (New York: Macmillan Co., 1902), pp. 32, 43 (a Connecticut piece), 122–24. Luke Vincent Lockwood, The Pendleton Collection (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1904), pp. 10, 228, plates 55, 56. Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols., 2d ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 1:116–17, 120–21, 123–24, 246–53; 2:282–86, and a number of illustrations, including in volume 1, figs. 115, 119, 121, 122, 134, 270–75. Lockwood’s career is profiled in Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), pp. 215–21.

Walter A. Dyer, Early American Craftsmen (New York: Century Co., 1915), pp. 326, 334–35. Much of Dyer’s book first appeared as articles in House Beautiful, Country Life in America, and Good Furniture, and he may not have been able to revise his work prior to publication in book form. Gardner Teall, The Pleasures of Collecting (New York: Century Co., 1920), frontis. and p. 113. Edwin A. Foley, The Book of Decorative Furniture: Its Form, Colour, and History, 2 vols. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 2:75–76, plate 61.

Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols., 3d ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), 1:351, 354–55, 357; 2:336. “Little-Known Masterpieces,” Antiques 1, no. 1 (January 1922): 17–18; “Little-Known Masterpieces,” Antiques 2, no. 3 (September 1922): 111–12. Walter A. Dyer, “John Goddard and His Block-Fronts,” Antiques 1, no. 5 (May 1922): 203–8. Malcolm A. Norton, “More Light on the Block-Front,” Antiques 3, no. 2 (February 1923): 63–66. “Bondome,” “The Home Market: A Block Front Secretary,”Antiques 3, no. 2 (February 1923): 83–84. Herbert Cescinsky, “The ‘Block-Front’ in England,” Antiques 4, no. 4 (October 1923): 176–80. Malcolm A. Norton, “Two Unusual Block-Front Pieces,” Antiques 7, no. 3 (March 1925): 127–28. Malcom A. Norton, “The Cabinet Pedestal Table,” Antiques 4, no. 5 (November 1923): 224–25. Norton contributed another note on the blockfront in Antiques, March 1925, as well as a short essay on the Newport cabinet pedestal table in November 1923.

N. M. I. [Norman M. Isham], “John Goddard and His Work,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design 15,no. 2 (April 1927): 14–24. Charles Over Cornelius, “John Townsend: An Eighteenth-Century Cabinet-Maker,” Metropolitan Museum Studies 1 (1928–1929): 72–80. In 1926, Cornelius published Early American Furniture (New York: Century Co., 1926), in which he makes mention of Goddard but not of Townsend.

Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 3 vols. (New York: Macmillan Co., 1928–1933), figs. 260, 269, 272, 317, 627, 628, 638, 639, 701, 708, and in volume 3, pp. 427–54, 453.

E. T. Casey, “The Goddards and the Townsends,” in A Catalog of an Exhibition of Paintings by Gilbert Stuart, Furniture by the Goddards and Townsends, Silver by Rhode Island Silversmiths, Rhode Island Tercentenary Celebration (Providence: Art Museum, Rhode Island School of Design, 1936), p. 15. Joseph Downs, “The Furniture of Goddard and Townsend,” Antiques 52, no. 6 (December 1947): 427–31.

Mabel Munson Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners: Part 1,” Antiques 49, no. 4 (April 1946): 228–31; Mabel Munson Swan, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners: Part 2,” Antiques 49, no. 5 (May 1946): 292–95; Mabel Munson Swan, “John Goddard’s Sons,” Antiques 57, no. 6 (June 1950): 448–49. Carpenter, Arts and Crafts of Newport, see especially pp. 7–25. Ethel Hall Bjerkoe, The Cabinetmakers of America (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1957). Wendell D. Garrett, “The Newport Cabinetmakers: A Corrected Check List,” Antiques 73, no. 6 (June 1958): 558–61. Wendell D. Garrett, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners: Random Biographical Notes,” Antiques 94, no. 3 (September 1968): 391–93. Wendell D. Garrett, “The Goddard and Townsend Joiners of Newport: Random Biographical and Bibliographical Notes,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1153–55. N. David Scotti and Joseph K. Ott, “Notes on Rhode Island Cabinetmakers,” Antiques 87, no. 5 (May 1965): 572; a three-part article on Rhode Island cabinetmakers and allied artisans by Joseph K. Ott in Rhode Island History 28 (1969): 3–25; 49–52; 111–21; and Joseph K. Ott, “Lesser-Known Rhode Island Cabinetmakers: The Carliles, Holmes Weaver, Judson Blake, the Rawsons, and Thomas Davenport,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1156–63.

Sloane, “John Cahoone,” pp. 116–17. Margaretta M. Lovell, “‘Such Furniture As Will Be Most Profitable’: The Business of Cabinetmaking in Eighteenth-Century Newport,” Winterthur Portfolio 26, no. 1 (spring 1991): 54–55.

Charles J. Burns, “The Newport Legacy of Miss Doris Duke: A History of the Newport Restoration Foundation and a Catalogue of Its Collection at the Samuel Whitehorne Museum,” Master’s thesis, Trinity College, 1995, cat. no. 33. Burns attributed the high chest to John Townsend and suggested that Baker may have assisted in its manufacture. Wallace Nutting, “A Sidelight on John Goddard,” Antiques 30, no. 3 (September 1936): 120–21; Joseph K. Ott, “John Townsend, A Chair, and Two Tables,” Antiques 94, no. 3 (September 1968): 388–90; Joseph K. Ott, “Some Rhode Island Furniture,” Antiques 107, no. 5 (May 1975): 940–51; Stanley Stone, “Documented Newport Furniture: A John Goddard Desk and John Townsend Document Cabinet in the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley Stone,” Antiques 103, no. 2 (February 1973): 319–21; Henry H. Hawley, “A Townsend-Goddard Chest-on-Chest,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 64, no. 8 (October 1977): 276–83. Other publications of this type are cited in American Furniture Craftsmen Working Prior to 1920: An Annotated Bibliography, compiled by Charles J. Semowich (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1984), pp. 36–39, 154–57. Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, American Furniture at Pendleton House (Providence: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), which also includes an essay by Monkhouse titled “Cabinetmakers and Collectors: Colonial Furniture and Its Revival in Rhode Island,” pp. 9–49; Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture, the Colonial Era: Selections from the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1984); Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, II, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985). Heckscher has written eloquently about Newport furniture on many occasions, see his earlier article, “The Eighteenth-Century Furniture of Newport, Rhode Island,” Apollo 111, no. 219 (May 1980): 354–61, and other citations of his work in this essay. Wendy A. Cooper, In Praise of America: American Decorative Arts, 1650–1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), pp. 26–28.

Carpenter, Arts and Crafts of Newport, pp. 21–23, 26. Carpenter’s book was to be the first volume in a projected series that was never realized. See also Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., “The Newport Exhibition,” Antiques 64, no. 1 (July 1953): 38–45; Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., “Rhode Island Block-Front Furniture,” Connoisseur 131 (1953): 91; and Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr., “Discoveries in Newport Furniture and Silver,” Antiques 68, no. 1 (July 1955): 44–49.

Joseph K. Ott, The John Brown Loan House Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture Including Some Notable Portraits, Chinese Export Porcelain, and Other Items (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1954).

Liza Moses and Mike Moses, “Authenticating John Townsend’s Later Tables,” Antiques 119, no. 5 (May 1981): 1152–63; Liza Moses and Michael Moses, “Authenticating John Townsend’s and John Goddard’s Queen Anne and Chippendale Tables,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1130–43; Morrison H. Heckscher, “John Townsend’s Block-and-Shell Furniture,” Antiques 121, no. 5 (May 1982): 1144–52. For the Yale University dressing table, see Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1988), cat. no. 109.

Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards (Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984). Benjamin A. Hewitt, Patricia E. Kane, and Gerald W. R. Ward, The Work of Many Hands: Card Tables in Federal America, 1790–1820 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1982).

After being displayed at the Girl Scouts Exhibition, the high chest remained in a private collection. When it was bequeathed to Yale University by its last owner, Doris M. Brixey, it was appraised by a leading auction house and sent on to the Yale University Art Gallery where Moses examined it. Ward, American Case Furniture, cat. no. 140.

Leigh Keno, Joan Barzilay Freund, and Alan Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode: Boston Georgian Chairs, Their Export, and Their Influence,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 267–306. The authors posit that a similar situation existed in New York.

Lockwood, Colonial Furniture, 2d ed., 1:116–17. Carl W. Dreppard, The Primer of American Antiques (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1944), pp. 17–19.

“Bondome,” “The Home Market,” p. 83. Cescinsky, “The ‘Block-Front’ in England,” pp. 176–80. Nutting, Furniture Treasury, fig. 260. See also Wendell D. Garrett, “Speculations on the Rhode Island Block-Front in 1928,” Antiques 99, no. 6 (June 1971): 887–91.

R. Peter Mooz, “The Origins of Newport Block-Front Furniture Design,” Antiques 99, no. 6 (June 1971): 882–86.

Margaretta Markle Lovell, “Boston Blockfront Furniture,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Muir Whitehill, Jonathan L. Fairbanks, and Brock W. Jobe (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1974), pp. 77–136.

John T. Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), pp. 4–6, 125–28, 148.

Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates, American Furniture, 1620 to the Present (New York: Richard Marek Publishers, 1981), p. 177. This large chest of drawers and others in the group are illustrated and discussed in the essay by Philip Zea in this volume.

Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America, 1743–1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955), p. 75.

Mabel Munson Swan, “Coastwise Cargoes of Venture Furniture,” Antiques 55, no. 4 (April 1949): 278–80. Sloane, “John Cahoone.” This article was based on her 1981 master’s thesis for the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture at the University of Delaware. See also Joseph K. Ott, “Rhode Island Furniture Exports, 1783–1800, Including Information on Chaises, Buildings, Other Woodenware, and Trade Practices,” Rhode Island History 36, no. 1 (February 1977): 7ff.

Lovell, “Such Furniture As Will Be Most Profitable.”

Personal communication to the author from Jonathan L. Fairbanks, March 1999, suggesting that the furniture made in Bristol, England, bears a close relationship with Newport work. Although the original owners of much Newport furniture are known, little analysis has been done on patronage patterns, aside from sections in the Sloane and Lovell articles, and in the two-part article by Wendy A. Cooper, “The Purchase of Furniture and Furnishings by John Brown, Providence Merchant: Part 1, 1760–1788,” Antiques 103, no. 2 (February 1973): 328–29; “Part 2, 1788–1803,” Antiques 103, no. 4 (April 1973): 734–43.

Charles F. Montgomery, “Regional Preferences and Characteristics in American Decorative Arts: 1750–1800,” in American Art: 1750–1800, Towards Independence, edited by Charles F. Montgomery and Patricia E. Kane (Boston: New York Graphic Society for the Yale University Art Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1976), pp. 50–65. Philip D. Zimmerman, “Regionalism in American Furniture Studies,” in Perspectives on American Furniture, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: W.W. Norton for the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1988), pp. 11–38. “Giving an Elephant to Blind Men? The Cross-Disciplinary Role of a Desk and Bookcase,” Arts Magazine 59, no. 2 (October 1984): 87–99.

Lovell, “Such Furniture As Will Be Most Profitable,” pp. 49–50. For the significance of labels in the next generation of cabinetmakers’ work, see Barbara McLean Ward, “Marketing and Competitive Innovation: Brands, Marks, and Labels in Federal-Period Furniture,” in Everyday Life in the Early Republic, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1994), pp. 201–18.

Sydney V. James, Colonial Rhode Island: A History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), p. 13. Other useful profiles of Rhode Island society are found in Carl F. Bridenbaugh, Peter Harrison: First American Architect (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1949); Edmund Morgan, The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, 1962), chap. 8; Carl F. Bridenbaugh, Fat Mutton and Liberty of Conscience: Society in Rhode Island, 1636–1690 (New York: Atheneum, 1976); William G. McLoughlin, Rhode Island: A Bicentennial History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; Nashville, Tenn.: American Association for State and Local History, 1978), esp. pp. 50–83; and Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt. James, Colonial Rhode Island, p. xiv. D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, vol. 1, Atlantic America, 1492–1500 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 106.

For more on this idea see Luke Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Job and Christopher Townsend,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, forthcoming). Keno, Freund, and Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode,” p. 298.

Montgomery, “Regional Preferences and Characteristics,” p. 59. Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), pp. 6–8; Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 185–89.

Greg Dening, “Introduction: In Search of a Metaphor,” in Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, edited by Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, and Fredrika J. Teute (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1997), p. 2. Edward S. Cooke, Jr., Making Furniture in Preindustrial America: The Social Economy of Newtown and Woodbury, Connecticut (Baltimore, M.D.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996). Even those studies that downplay the importance of group norms in furniture production and emphasize “the pervasive forces of individuality, deviation, and the prospects of culture change” nevertheless are cognizant of the importance of studying the objects as evidence; see, for example, Gerald L. Pocius, “Gossip, Rhetoric, and Objects: A Sociolinguistic Approach to Newfoundland Furniture,” in Ward, ed., Perspectives on American Furniture, pp. 303–45; quotation p. 308.