Coffer for the Hermann Benevolent Brotherhood, Philadelphia, 1816. Mahogany, maple, and cherry with yellow poplar. H. 41 5/16", W. 77 3/16", D. 41 5/16". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

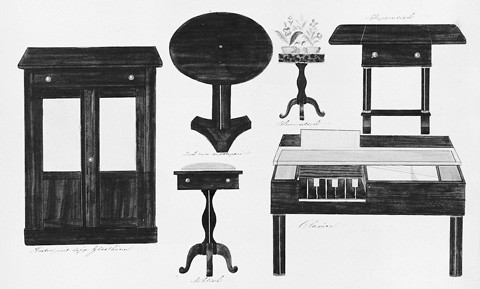

Leaf no. 77 showing toy furniture from a trade catalogue, possibly G. G. Fendler and Company, Nuremburg, Germany, 1830–1840. Hand-colored lithograph. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

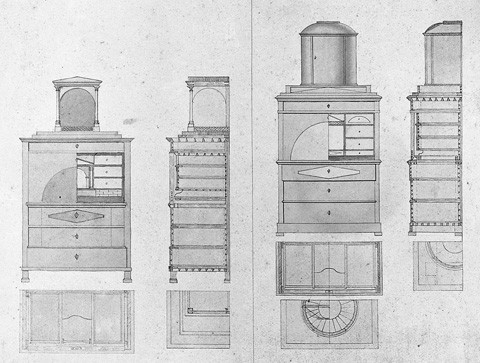

Designs for fall-front secretaries by Frederick Gutekunst, Sr. (1801–1890), Württemberg, Germany, 1828. Ink and ink wash on paper. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.) This sheet is one of fourteen brought to Philadelphia by Gutekunst in 1831. The images are variously dated from 1825 to 1828.

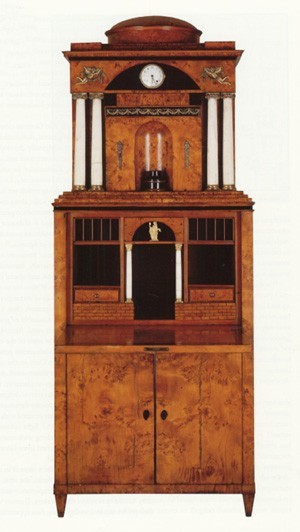

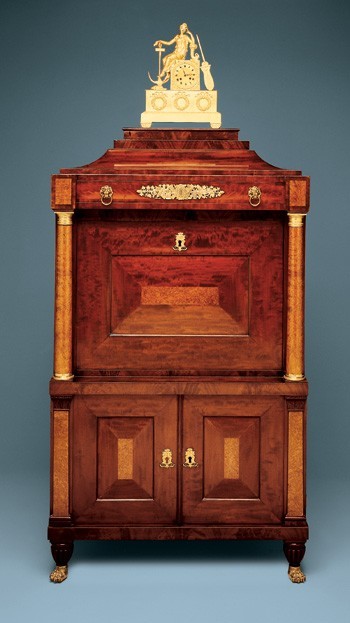

Fall-front secretary with musical works attributed to Johann Gottfried Kaufmann (1751–1818), Dresden, Germany, ca. 1804. Burled veneer with basswood; marble, paint, and gilded bronze. H. 84", W. 33 1/4", D. 20 1/8". (Stephen Girard Collection, Girard College, Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

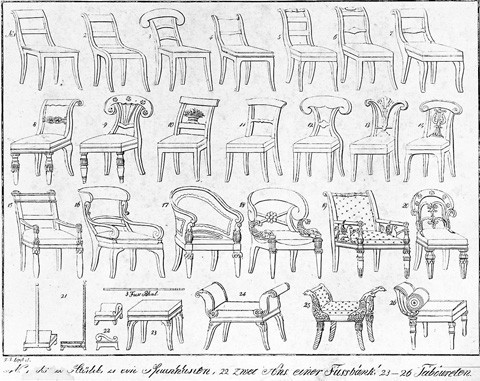

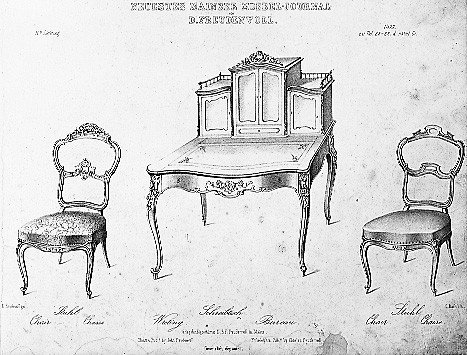

Designs for chairs and other furniture illustrated on plate 1 from G. J. Lipp, Meubles-Zeichnungen für Tischler (Berlin, 1835). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

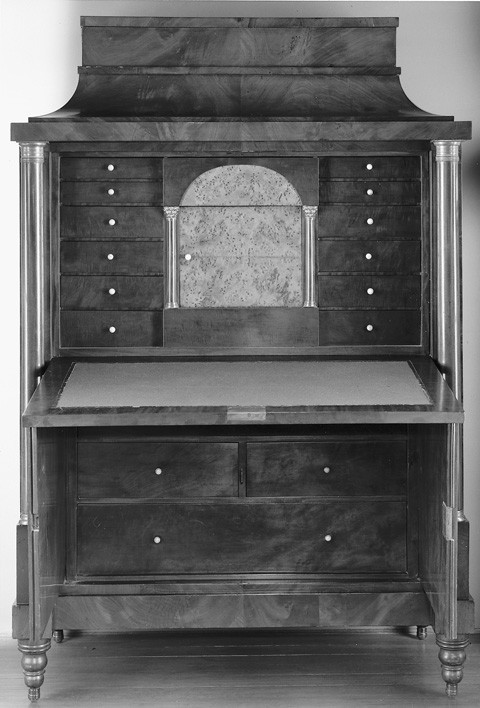

Fall-front secretary, Germany, 1820–1835. Mahogany with oak, pine, and basswood; gilding, pewter inlay, and gilded bronze. H. 72", W. 40 3/4", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

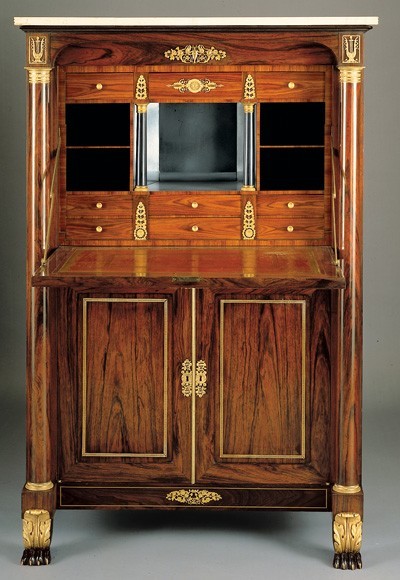

Fall-front secretary, Philadelphia, 1820–1830. Mahogany and rosewood with pine, yellow poplar, and chestnut; gilded bronze. H. 61", W. 49 3/4", D. 26 1/2". (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pianoforte by Emilius N. Scherr (1794–1874), Philadelphia, ca. 1830. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods; ivory and basemetals. H. 36", W. 68", D. 28". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. George L. Rush.)

Pianoforte by Loud & Brothers (fl. 1825–1833), Philadelphia, ca. 1830. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods; ivory and basemetals. W. 68 5/16". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Crosby Brown Collecton of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.2812) Photograph ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pier table attributed to Anthony Quervelle, Philadelphia, ca. 1830. Mahogany with yellow poplar, white pine, and yellow pine; marble and glass. H. 37 1/2", W. 41", D. 30". (Courtesy, Dallas Museum of Art, Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Willard E. Brown, III—The Bolton Foundation, Governor and Mrs. William P. Clements, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Gerald C. Johansen, George and Schatzie Lee, Mr. Irving L. Levy, Mr. and Mrs. Ronald L. McCutchin, the Stanley and Linda Marcus Foundation, Mr. Frederick R. Mayer, and the Frederick M. Mayer Memorial Fund.)

Pier table, southern Germany, 1820–1830. Materials and dimensions not recorded. (Former collection of L. Brenheimer, Munich, Germany; image from Hermann Schmitz, Deutsche Möbel des Klassizismus [Stuttgart: Hoffmann, 1923], p. 202.)

Card table by Anthony Quervelle (1789–1856), Philadelphia, 1830–1840. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods. H. 29 3/4", W. 36 7/8", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table bears Quervelle’s label for his 126 South Second Street shop. He was active there between 1829 and 1849.

Card table, possibly Altona, Germany, ca. 1830–1835. Mahogany. Secondary woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Städtisches Museum, Flensburg, Germany.)

Fall-front secretary, Philadelphia, 1815–1830. Rosewood with pine and tulip poplar; marble, gilding, paint, brass, and gilded bronze. H. 60", W. 40", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

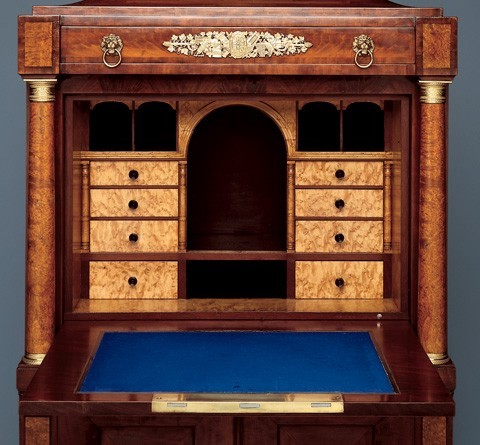

Fall-front secretary, Philadelphia, 1815–1830. Mahogany, hard maple, ebony, and cherry with yellow poplar and eastern white pine; gilded bronze. H. 62 7/8", W. 35 7/8", D. 21 1/8". (Courtesy, Dallas Museum of Art, Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Collection, anonymous gift in memory of Frederick Miller Mayer; photo, Tom Jenkins.)

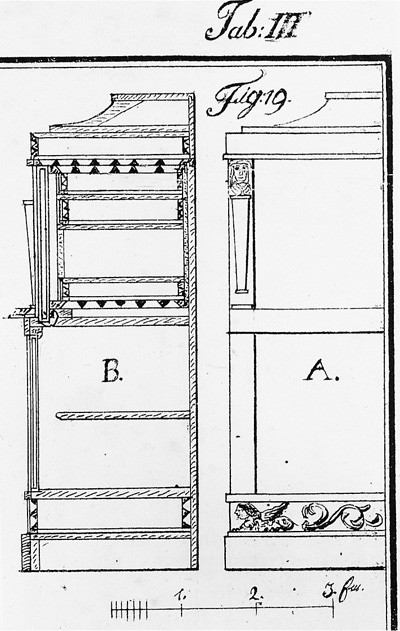

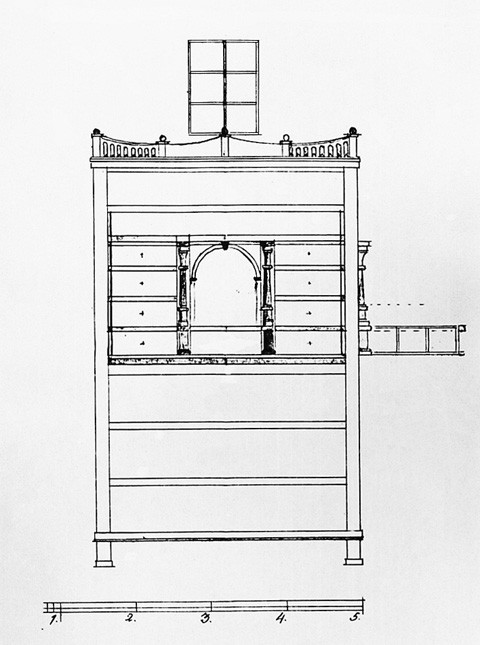

Design for a fall-front secretary illustrated on plate 3, figure 19 of Marius Wölfer, Der Bau- und Meubel-Schreiner, eine bildliche Anweisung zur antiken und moderne Architecktur (Illmenau, Germany, 1828). (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library.)

Rear view of the fall-front secretary illustrated in fig. 15.

Fall-front secretary with wings, Philadelphia, 1817–1825. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar; ebony, brass, and glass. H. 63 3/4", W. 73 3/4", D. 28 1/2". (Philadelphia Museum of Art, donated by Simon Gratz in memory of Caroline S. Gratz; photo, Eric Mitchell.)

Interior view of the fall-front secretary illustrated in fig. 18.

Interior view of the fall-front secretary illustrated in fig. 15.

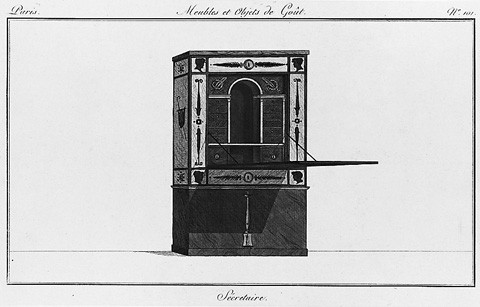

Design for a fall-front secretary illustrated on plate 101 of Pierre de la Mésangère, Collections des Meubles et Objects de Goût (Paris, 1804). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

Design for a fall-front secretary by Joseph Fiedler, Württemberg, Germany, 1800–1810. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Historical Society of York County, York, Pennsylvania; photo, Charles Venable.)

Fall-front secretary, Philadelphia, 1815–1830. Mahogany and maple with yellow poplar and pine; gilded bronze. H. 65", W. 43 1/2", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Work table, Philadelphia, 1820–1840. Mahogany with ash and other unidentified secondary woods. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Antiques.)

Chest of drawers, Philadelphia, ca. 1840. Mahogany with pine and yellow poplar. H. 45 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 20 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Tom Jenkins.) The chest is inscribed: “Bought from the / D. Pine Estate of Whitford, Pa. / by Justen Warren (?) / West Chester, Pa. / March 1912”.

Pier table, Philadelphia, 1830–1840. Mahogany and unidentified secondary woods; marble and glass. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Decorative Arts Reference Library, Winterthur Museum.)

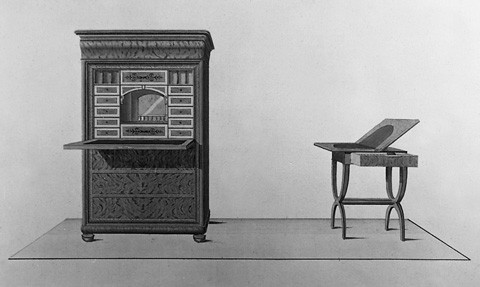

Design for a fall-front secretary (1837) illustrated on plate 2 of Wilhelm Kimbel, Journal für Möbelschreiner und Tapezierer, vol. 1 (Mainz, 1835–1853). (Courtesy, Cooper-Hewitt, National Museum of Design.)

Fall-front secretary, probably Philadelphia, 1835–1850. Mahogany with yellow poplar; glass. H. 65 1/2", W. 42 3/4", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Historical Society of York County, York, Pennsylvania; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing bureau made by Walter Pennery in John Jameson’s workshop, Philadelphia, 1830. Maple with tulip poplar; glass, brass, and iron. H. 87 3/8", W. 43 3/8", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The bureau is inscribed: “The year of our lord one thousand eight hundred / and thirty / Philadelphia June 11th 1830 / Walter Pennery”.

Design for a desk and chairs illustrated on plate 11 of D. Freudenvoll, Neuestes Mainzer Moebel-Journal (Mainz, 1846–n.d.). (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

Sofa, New York City, ca. 1849–1850. Rosewood with ash. H. 43", W. 74", D. 34". (Courtesy, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Friends of Decorative Art; photo, Tom Jenkins.) The back is constructed from seven layers of laminated wood. The newspaper fragments found in this sofa are dated 1849.

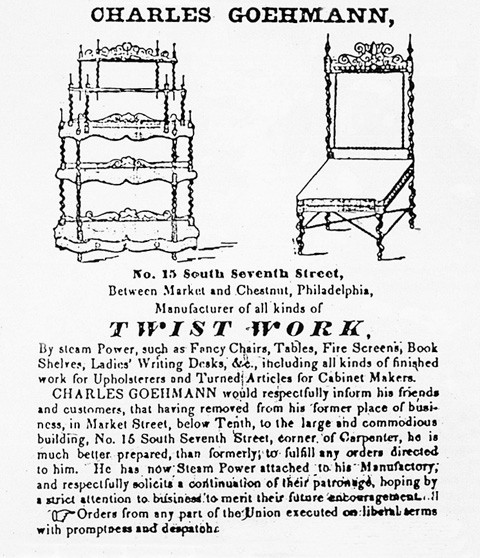

Advertisement for Charles H. L. Goehmann (d. 1866) on page 27 of O’Briens Philadelphia Wholesale Business Directory (Philadelphia, 1850). (Photo, Charles Venable.) Goehmann is listed in Philadelphia directories from 1849 to 1866. He was at the 15th Street address noted here in 1850 and 1851. He was well known for his fancy twist work, for which he was cited by the Franklin Institute in 1844.

Designs for chairs illustrated on plate 3 of J. W. Hanke, Neues Journal für Möbelschreiner (Frankfurt am Main, 1841). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library.)

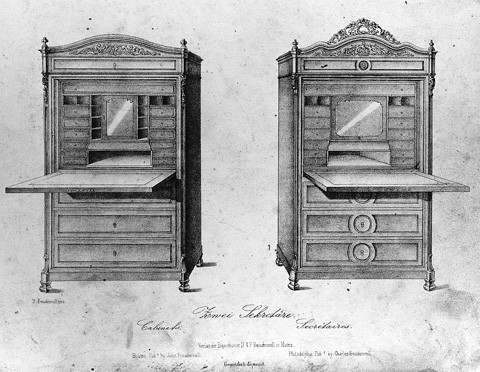

Designs for fall-front secretaries illustrated on plate 12 of D. Freudenvoll, Neuestes Mainzer Moebel-Journal (Mainz, 1846–n.d.). (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

German craftsmen and styles contributed a great deal to the extraordinary complexity of American furniture design during the first half of the nineteenth century. A host of aesthetic ideas, including Germanic ones, competed in the marketplace for acceptance. Before 1830, the complete acceptance of Germanic impulses was rare. Most German workmen were forced either to adopt the prevailing American taste in consumer goods or to change professions. With the dramatic rise in German immigration beginning in the 1830s, however, this sublimation of German design aesthetics was less complete. Between 1830 and 1850, thousands of Germanic woodworkers found employment in America’s urban centers. In introducing Germanic construction methods and stylistic details, these craftsmen played a vital role in transforming furniture design, particularly in the late classical and rococo revival modes.[1]

German Immigrant Cabinetmakers: The Continental Background

Although the colonies had attracted German immigrants from the very beginning, North America did not experience any great influx of Germans until 1683, when the first group of Palatinate Germans arrived in Pennsylvania. By the late eighteenth century, German immigration had slowed to a virtual standstill, but in 1816, the situation changed. Spurred by a series of bad harvests in southwestern Germany, an estimated 20,000 Germans emigrated to the United States between 1816 and 1817. This exodus, primarily from the area around Württemberg, soon ceased due to a temporary economic recovery. Throughout the 1820s, German immigration to America was slow. In the peak year 1828, only 3,443 Germans and Swiss crossed the Atlantic. The total number for the entire decade stood at 4,785 Germans and 3,117 Swiss.[2]

The years between 1830 and 1854 proved to be very different. As historian Mack Walker points out, “emigration was revived about 1830 by rising prices, the European revolutions [and] a more definite and more favorable view of America.” Such factors, coupled with the severely depressed state of the German economy, especially with regard to agriculture, created a situation in which many Germans came to believe that their traditional, small-town way of life was slipping away. As a result, thousands of those who could afford to do so left—primarily for America. During the 1830s, 124,726 arrived in America, and 464,330 landed between 1840 and 1850 (inclusive). In 1854, the peak year for this great wave of immigration, 215,009 Germans left their homes to begin again in this country.[3]

The vast majority of Germans who came to America during the first half of the nineteenth century were members of the lower middle class rather than peasants. Most were small farmers, independent village shopkeepers, and skilled artisans from rural areas. The percentage of craftsmen was occasionally as great as 60 percent. As Walker notes, this era of immigration “probably included a higher proportion of prosperous and skilled, educated people than that of any other time, while the poorest and least valuable members of the society stayed behind.”[4]

The reasons behind this large-scale exodus of highly skilled craftsmen and businessmen were manifold, but several factors seem particularly important. First, the collapse of the French Empire under Napoleon had a major impact on the rural craftsman. After French domination of the Continent ended and the British lifted their blockade of Continental ports, the German states (along with the rest of Europe) were flooded with cheap English exports, many of which displaced locally manufactured goods. This instability in Germany’s regional economy was furthered by the creation of the Zollverein (Customs Union) in 1834. Under the stipulations of this union, many German states lifted tariffs on goods from other member states. Although designed to bring prosperity through increased trade, the Zollverein removed the legal barriers behind which regional economies had formed; consequently, many local products were replaced by less expensive goods from other parts of Germany. The situation deteriorated even more as the roles of the factory and middleman became more pronounced throughout the period, as Germany matured industrially.[5]

Another occurrence that ultimately forced craftsmen to leave their homes was the decline and stagnation of German agriculture during much of the early nineteenth century. Since most of the artisans who eventually came to America were from small rural towns, their livelihood ultimately depended on the strength of the agricultural sector. When farmers no longer were able to produce an agricultural surplus, orders for custom-made goods, like furniture, quickly declined and often ceased altogether.

Beyond these more purely economic factors, demographics also worked against the craftsman in early nineteenth-century Germany. As young men moved out of the depressed agricultural sector into the crafts, the number of apprentices and journeymen grew at an abnormally high rate. By the 1830s, the ratio of craftsmen to the general population was completely out of balance. This situation (which did not change until much later in the century when industrialization began to absorb the surplus) led directly to underemployment, lower wages (approximately 25 percent), and general hardship. In some professions, especially weaving, as many as one-quarter to one-half of the artisans lived on the edge of subsistence. This enormous increase in the number of apprentices and journeymen also meant that master craftsmen no longer dominated their trade. Between 1800 and 1850, the number of masters rose approximately 30 percent, while that of apprentices and journeymen increased 127 percent. In 1800, every third master had a journeyman; by 1819, every second master had a journeyman; and by 1861, there were more journeymen than masters. As a result, most journeymen could no longer look forward to becoming masters with full guild rights and their own shop.[6]

While economic and demographic shifts combined to make the craftsman’s place in society less secure, changes in the way Germans perceived America aided individuals in making the final decision to leave their homeland. Though the image of “America” had appeared in German literature since the seventeenth century, it was not until the early nineteenth century that firsthand travel accounts began to surface with frequency. Initially, some of these works, such as Ludwig Gall’s My Immigration to the United States of North America (1822), presented a very negative view of America, but this outlook soon changed. In 1829, Gottfried Duden published his far more positive and influential Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America. This book, which coincided with and to some degree initiated the revival of German immigration around 1830, spoke of America in glowing terms.[7]

Alongside the travel accounts, two other literary genres had a profound influence on German immigration. The first of these was the letter. By the 1830s, correspondence from relations and friends who had established themselves in America was pouring into Germany. Having experienced a horrific crossing from Baden to Baltimore in 1817, Chrisostomus Weis nevertheless wrote:

Dearest brother what do you think will you come yes I advise you to come 100 times we have wished if only our brothers and sisters were with us and I advise all who are of a mind to come they must just come they will make better lives than in Germany. [America is] a free country, it is under no ruler every 4 years a cardinal is elected over the whole country, the country is divided into cantons and each canton has a president you pay no taxes and give nothing. . . . If you were in this country working as in Germany you would make a good future for your children.

The impact of letters such as Weis’s was often magnified by their publication in German newspapers. Not suprisingly, they often sparked cluster immigration from the vicinity of the recipient.[8]

The Auswanderungsratgeber (immigrant advice book), which became increasingly popular during the 1830s, was another important catalyst for immigration. Advice books provided information on which route to take and where to settle. Most recommended that the “section of society which has money enough to make a new start in America will find it easy to begin a new life, but those who possess only ‘naked life’ should not emigrate in the first place.” Expanding on this general rule, many advice books provided potential emigrés with very specific information on their prospects across the Atlantic. Alexander Ziegler’s German Immigrant to the United States of North America: A Guide for His Journey (1849) noted that “those craftsmen who come to America can be divided into four groups: (1) those who always find work and profit; (2) those who have difficulty in finding employment; (3) those who fare especially poorly; (4) and those who must change professions.” Among the first group, he listed forty professions including cabinetmakers, joiners, ship carpenters, clockmakers, lacquerers, and gilders. Ziegler concluded that in general “the worker in America can, due to higher pay, obtain a higher standard of living, easily get married, provide a good upbringing for his children, and can put back a nest egg for his family.” Such statements in advice books, along with letters from America, played a major role in helping individuals make that final and fateful decision to leave their homes for the New World.[9]

Once the decision had been made, questions remained regarding the best route to take and where to settle. Again, personal contact and advice books showed the way. Early in the century, the majority of Germans came to America by way of Le Havre, Antwerp, and the Dutch ports at the mouth of the Rhine. As time went on, however, increasing numbers of immigrants passed through the north German ports of Bremen and Hamburg. Initially, they left Europe as outward ballast on American-bound ships. This situation soon changed, as the number of emigrés rose in the 1830s and as shipowners realized they could profit from passenger service. Direct packet lines between German and American ports were thus established. As this transportation network developed, arrivals in Philadelphia, which had always been the traditional port of entry for incoming Germans, began to decline. New York emerged as the main port of entry for European immigrants due to its ice-free harbor and location. By 1814, New York equaled Philadelphia in volume of emigrés, and by 1825 it was firmly established as the leading immigrant port. Regardless of immigrants’ place of arrival, coastal shipping lines carried them to their final destination if it was not inland.[10]

Naturally, the advice of friends and relatives already in America greatly influenced the choice of these “final destinations,” but advice books also played an important role. Of particular interest are the published descriptions of American cities and regions. New England, for example, was portrayed as uninviting; thus, few Germans chose cities like Boston as their new home. New York was a different matter. In 1847, one author wrote:

The city of New York has about 50,000 German immigrants. As soon as one crosses Bowery Street almost everything is German and as a rule one can always converse in German with those who are dressed more comfortably than fastidiously. If one takes into consideration the northern parts of the city which are mainly populated by Germans and excludes those Germans who live separately throughout the rest of the city, it appears that the Germans form at least one-eighth of the population of New York City. This number is probably more low than high. . . . Thus, approximately 80,000 Germans live in New York and its environs.

Though a myriad of factors influenced where a German craftsman settled in America, passages like this one must have been responsible for funneling thousands of highly skilled German craftsmen into the urban centers of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans.[11]

The New World

Although New York eventually became the main port of landing for immigrants, Philadelphia attracted a substantial number of Germans and Irish newcomers. In German immigrant literature, Philadelphia invariably received very good billing. In 1819, Ludwig Gall advised his countrymen to immigrate there, for “there [were] a hundred opportunities to earn six to eight dollars a week.” Nearly three decades later, the popular advice writer Traugott Bromme described Philadelphia as “one of the most well-planned and beautiful cities on earth,” with many attractions and a strong economy. By concentrating on the positive aspects of urban life in Philadelphia and ignoring or distorting negative features like street violence and labor unrest, Bromme created an idyllic view that must have appealed to many prospective immigrants. Perhaps even more enticing were those descriptions of Philadelphia that stressed the Germanic background and character of the city. In his History and Status of the Germans in America (1847), Franz Löher expanded on what many advice books had been saying for years when he wrote that “over one-third of the population of Philadelphia is of German origin. Of these 80,000 still understand German, but only 40,000 speak it.” Regardless of the negative comments that Löher occasionally made, his reference to Philadelphia’s large Teutonic community was certainly what many Germans were looking for, given their unfamiliarity with the English language and American customs.[12]

Such descriptions of Philadelphia and the early presence of Germans in the city helped make it a major destination for new arrivals. Although numerous Germans probably came to Philadelphia during the late 1820s and early 1830s, early figures on immigrant landings there are unavailable. Beginning in the mid-1830s, a clearer picture emerges. In 1835, 1,890 immigrants arrived from Germany; 4,079 arrived in 1840; 5,767 arrived in 1845; and 10,515 arrived in 1850. The number of Germans and Irish who came to Philadelphia via New York is unknown, but it probably surpasses the number who arrived by direct routes. By 1850, Philadelphia’s population was 29 percent foreign born. The Irish comprised 17.6 percent (71,787), and the Germans accounted for 5.6 percent (22,788).[13]

Many of the Germans who came to America before 1850 were highly skilled artisans. As a result, they tended to occupy jobs commensurate with their training. The furniture-making trades were particularly prominent. By 1850, there were 494 German cabinetmakers and 76 German turners working in Philadelphia. In all, over a third of the city’s furniture makers (38.8 percent of cabinetmakers and 29.2 percent of turners) were German emigrés. The situation was even more skewed in New York where 61 percent of the furniture makers were German born by 1855.[14]

Although skill accounted for much of the success of these immigrant craftsmen, the establishment of a labor information network beginning in the early 1830s helped artisans find employment. The primary agents in this network were the various German aid societies in Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore and German-language newspapers such as the Philadelphia-based Die Alte und Neue Welt (The Old and New World). As soon as immigrant ships landed, agents from one or more of the city’s German aid societies generally went on board to advise the newcomers. A good example of such a group is Philadelphia’s Hermann Unterstützungs Brüdershaft (Hermann Benevolent Brotherhood), which was founded in 1816 to assist immigrants (fig. 1). Aid societies helped maintain ledgers “in which the names of those who seek work as well as those of employers who need workers, are recorded” and often kept them at the docks or in the business districts. Representatives from these groups also advised artisans to contact the various city workshops in person and warned them not to trust the deceptive agents of transport companies, who were far more interested in the immigrant’s money than in his general welfare.[15]

Like benevolent societies, German-language newspapers also helped woodworkers find employment. J. G. Wesselhoeft, the owner of the nationally distributed Die Alte und Neue Welt, used his newspaper to support the “information network” he established in the early 1830s. At the center of Wesselhoeft’s business was his “Address-und Nachfragungs Bureau” (address and inquiry bureau) at 471 Pearl Street in New York. As a complement to the New York office, he established a “Commissions Bureau” on the Place Louis-Philippe in Le Havre, France. For a fee, the Continental office provided Germans who were emigrating from French ports with information and advice to simplify their crossing and relocation and offered services such as letter and address forwarding. When the agency in New York received the specific requirements of an artisan, it provided that individual with “further information through which hand craftsmen and day laborers [could] obtain employment in most cases.” The most amazing aspect of Wesselhoeft’s operation is that it was national in scope and presumably gathered information on job opportunities in every city in which his newspaper had an agent. His papers also ran lists of jobs available. One published by Wesselhoft’s German Intelligence Office in New York in June 1836 concluded: “All possible effort will be made to find a position for workers in other professions and crafts within eight days or less.”[16]

Many American-born shopowners were anxious to hire German woodworkers, particularly if they would work for lower wages. In fact, the employment of Germans in previously all-Anglo shops became so common that nativists railed against the practice during the 1840s. In November of 1845, the New York Daily Tribune reported that journeymen’s wages had fallen from $12 per week in 1836 to $5 in 1840 and speculated:

The cause of the great decrease in the wages of Cabinet-Makers is in a great measure the immense amount of poor Furniture manufactured for the Auction-Stores. This is mostly made by Germans, who work rapidly, badly and for almost nothing. There are persons who are constantly on the watch for German emigrants who can work at Cabinet-Making—going on board the ships before the emigrants have landed and engaging them for a year at $20 or $30 and their board, or on the best terms they can make. The emigrants of course know nothing of the state of the Trade, prices, regulations, &c. . . . and become willing victims to any one who offers them immediate and permanent employment. This it is which has ruined the Cabinet-Making business, and the complaints on the part of the Journeymen are incessant. There is, however, no remedy for the evil, as we see.

Although this article appeared in a New York paper, the widespread employment of German cabinetmakers in Philadelphia and other American cities undoubtedly prompted similar responses.[17]

Expectations and Realities

The fact that hundreds of German furniture makers found employment in Philadelphia does not mean that their relocation was easy or that America fulfilled their expectations. According to Mack Walker, German immigrants came to America “less to build something new than to regain and conserve something old, which they remembered or thought they did: to till new fields and find new customers, true enough, but ultimately to keep the ways of life they were used to, which the new Europe seemed determined to destroy.” In the case of the German cabinetmaker, this vision was doomed.[18]

Judging from the amount of space allocated to the topic in advice books, the fact that America maintained a highly competitive free trade system, as opposed to one dominated by guilds, presented a major problem for most immigrant craftsmen. With its myriad rules and regulations, the guild governed virtually every aspect of a craftsman’s life in early nineteenth-century Germany. Guilds decided who could become a cabinetmaker and dictated the length of the apprentice’s and journeyman’s terms. Rules also prescribed exactly how furniture could and could not be made. Cabinetmakers, for example, were often forbidden to use nails of any kind. Some guilds even specified what type of wood and joinery techniques to employ. Master-journeyman relations were similarly controlled, and the number of apprentices and journeymen in a single shop was strictly regulated. In short, almost every facet of a cabinetmaker’s life was ordered and protected by the cabinetmakers’ guilds.[19]

Because the guild system ran counter to American free trade practices, advice books often described what it would be like to work without guilds. In 1846, German author Traugott Bromme wrote:

It is important to acquaint the German craftsman with the fact that in [America] there are no guild privileges. Each man can work at any occupation he chooses. The consequence thereof has been an extraordinarily strong competition between workers. As a result many products are made either better or in a simpler manner requiring less time. The craftsman coming from [Germany] is thus initially at a disadvantage, since he neither speaks English nor is accustomed to working in the freer American manner. However, both problems are not insurmountable and an industrious craftsman, once having overcome these difficulties, can succeed well in this country.

“Skill, quickness, honesty, rectitude, and piety,” he concluded, “are the conditions which form the basis of one’s success and happiness” in America. In reality, however, the radical difference between German guilds and American free trade proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for some immigrant cabinetmakers, and the decision to change professions was common. In Philadelphia, furniture makers Charles Pommer (1780–1839) and Adolph Hoehling (1807–1893) temporarily became hotel and tavern proprietors. Similarly, Charles Dominique (b. 1804) worked as a grocer for several years, and Theobald Stockel (1806–1856) became a stovemaker. Some cabinetmakers advised their sons not to enter the craft. Frederick Gutekunst (1801–1890), for example, wanted his son, Frederick, Jr. (1831–1917), to become a lawyer. Although documentation for their relocation is scant, hundreds of German furniture makers probably left the city and moved inland. A fictional German glazier alluded to this negative aspect of urban American life in a popular novel of the day: “I, like all Germans, have fallen on hard times. The goldsmith is supposed to become a watchmaker, the cloth weaver a mechanical loom operator, the wallpaperer a cabinetmaker, and the cabinetmaker a painter—now what a glazier is supposed to become here I cannot determine.” A large number of Germanic emigrés undoubtedly agreed with this perspective.[20]

Despite such disadvantages, many German cabinetmakers who stayed in Philadelphia survived. Most did not establish their own shops, however, even though they had come to America to do precisely that. According to the 1850 Census of Manufactures, Germans owned only thirteen of the 169 shops that produced goods worth $500 or more a year. Less than 10 percent of German-born cabinetmakers had their name and profession listed in the 1850 edition of McElroy’s Philadelphia Directory. This rate, which is five times lower than that of the adult male population of Philadelphia in general, supports the hypothesis that most German furniture makers worked for other people, since journeymen had no need to advertise independently.[21]

The reasons why Germans did not establish their own shops in Philadelphia are not completely clear, but several factors are apparent. Advice books often cautioned immigrant craftsmen against working for themselves initially because most did not speak English or understand American business practices. A lack of proficiency in English was a great hindrance to the establishment of one’s own shop, particularly if one’s clientele was mostly English speaking. The extent of this problem is attested to by the frequent advertisements in German-language newspapers in which German craftsmen were seeking bilingual apprentices and journeymen. Such newspapers also abound with notices for English lessons and German-English dictionaries. A particularly revealing example of a contemporary language aid is The American Interpreter/Der Amerikanische Dolmetscher, which was printed in New Berlin, Pennsylvania, in 1831. Designed to be carried in the owner’s pocket, this thin volume primarily consists of vocabulary words concerning the major crafts in which Germans were heavily concentrated, particularly woodworking, metalworking, and agriculture. It also outlines how orders, receipts, and bills should be written in the target language. With the help of such books and bilingual co-workers and friends, Germans and Americans managed to work and live together as best they could.[22]

Lack of capital also prevented many immigrant German cabinetmakers from establishing their own shops. Often immigrants had to sell virtually all their possessions to pay for their transatlantic crossing. Tools appear to be the principal exception to this rule. Although American tools were thought to be of higher quality, German craftsmen were consistently told not to sell their tools in Germany because comparable ones in America were “almost twice as expensive” and “a craftsman is usually more comfortable with his own tools, and new ones are never as handy.”[23]

The fact that most Germans did not establish their own shops, as they had expected, pushed them into the mainstream of American life. For most, America proved to be a land of both opportunity and disappointment. Not only did they have to adjust to working for someone else permanently, but they typically had to learn English and associate with native co-workers. American work routines were faster, and the need to cut labor costs meant that furniture was often less meticulously made than in Germany. Although this country’s laissez faire craft system freed them from the often oppressive control of the guilds, it simultaneously exposed immigrant woodworkers to fierce competition and to work practices with which they were totally unfamiliar.

Some German cabinetmakers resisted these changes by joining their native-born counterparts in the re-organization of the Society of Journeymen Cabinetmakers. When founded in Philadelphia in 1806, this organization was basically a benevolent society. In 1829, however, the members revised the constitution, so that the main purpose of the society centered around labor relations. Unskilled labor was to be kept out of the craft, and wages were to be maintained at an acceptable level. Ultimately these efforts failed, and the journeymen opened their own cabinet warerooms in 1834 in order to bypass their masters’ role as retailers. Although their Continental training had not prepared them for this form of political aggressiveness, the Society of Journeymen Cabinetmakers offered a type of guild protection that may have appealed to European craftsmen. This supposition is supported by the fact that at least four Danish-born cabinetmakers working in Philadelphia signed the Society’s new constitution in 1829. These artisans were George Brown (b. 1798), Nicholas Dalhoff (b. 1802), Charles Holst (1798–1867), and Jacob Sievers.[24]

German Influence on Philadelphia and Its Furniture

Due to the early settlement of Germans in and around Philadelphia, the city traditionally had a strong Teutonic element. With the cessation of significant German immigration in the late eighteenth century, however, the German character of Philadelphia receded. Germans arriving in the early nineteenth century often found Philadelphians of German ancestry to be “dry, cold Americans,” unaware of their origins. With the revival of immigration in 1816, this situation changed. The German nature of Philadelphia was not only renewed but enhanced. The simple fact that the approximately 23,000 Germans (5.6 percent of the total population) who lived in Philadelphia by 1850 did not settle within the confines of an ethnic ghetto meant that their presence was felt throughout the city.[25]

German was spoken widely within Philadelphia. Some native shopowners found it necessary to hire bilingual clerks to serve German-speaking customers. In 1844, cloth merchant George F. Smith advertised that German was spoken in his store. Besides reintroducing the German language, this new influx of immigrants altered the character of Philadelphia in other ways. Among the city’s numerous libraries, for example, two were devoted to German language books and periodicals. The library of the Philadelphia German Society had 4,000 volumes in 1833, and Wesselhoeft’s Lending Library contained 1,679 volumes when it opened in 1842. Arriving Germans also enhanced Philadelphia’s musical and theatrical life. Contemporary German-language newspapers are filled with notices of performances by German singing societies and musical groups as well as dozens of concerts by central European soloists and concert artists. In addition, certain restaurants in the city specialized in German food and drink. In 1819, Kutter & Shuman opened their “New German Coffee House” at 75 Walnut Street, where an assortment of beverages including “good coffee, tea, chocolate, the best of liquors, wines, port, ale, cider, strong beer, etc.” were “served up with exactness and prompt attention.” During the first half of the nineteenth century, substantial quantities of wine and foodstuffs, particularly cured meat and fish, were imported into Philadelphia directly from central Europe.[26]

Even though these developments in libraries, music, and gastronomy were significant, they may not have affected the native population as directly as the burgeoning importation of German consumer goods during this period. Although American merchants were free to trade with any country they chose following the Revolution, the real expansion in German-American trade seems to have paralleled the influx of German shopowners and merchants in the 1830s and 1840s. The presence of such immigrants, coupled with the establishment of German business agents and trade councils in this country, meant that direct and often familial ties existed between central European producers and American consumers.[27]

Native-born and German-American merchants quickly took advantage of these connections, ordering either through German agents or directly from Europe. Trade manuals, like C. W. Rördansz’s Complete Mercantile Guide to the Continent of Europe (1819), helped simplify the process. German-language manuals were also available through urban book dealers. J. G. Wesselhoeft stocked numerous trade and business aids, including “Exchange-Rate Guides” and the fourth edition of the Complete Address Book for Merchants, Manufacturers, Apothecaries, Smelters, Glass Houses, and Hotels. This multivolume set contained descriptions of 3,000 European cities and main marketplaces of the world, along with 80,000 business addresses, including foreign branches of firms. Along with the publication of business guides and directories, German banks sent agents to America to facilitate trade with Europe. Philipp Speyer, the New York agent for a banking house in Frankfurt am Main, advertised in 1842 that his direct connections with Germany and Europe as a whole enabled him “to handle any monetary exchange, including payments in any part of Europe to the satisfaction of his customers.” Such agents enabled American merchants to carry out transatlantic business more safely and expeditiously.[28]

Using their personal contacts, trade manuals, and exchange tables, Philadelphia merchants imported a variety of German goods ranging from sheep shears to chessmen. German products that were especially prevalent included drugs and chemicals, textiles and clothing, table and mirror glass, base metal utensils, arms, and musical instruments. “Fancy goods” merchants were particularly dependent upon German products. Philadelphia directories between 1820 and 1850 abound with shops advertising German fancy goods, especially combs, baskets, brushes, and toys. In fact, the trade in German fancy goods was so substantial that retail book dealers sold German trade catalogues for such wares (fig. 2). From 1839 on, Wesselhoeft regularly advertised catalogues for items made in and around Nuremberg, the European center of production for many fancy goods and toys:

Patternbooks for Nuremberg and Furth Manufacturers—one hundred half folio plates with texts and prices. $8. The plates are very neat and correct, painted in colors, and for Fancy ware merchants very useful. They contain, for example, boxes, mirrors, treenware, toys, brassware, writing pens, tin and wooden ware, etc.

Trade catalogues for other German products, such as furniture hardware and glassware, were also sent to America.[29]

Of all German products imported into America, the most significant for this study were clocks and musical instruments. In 1835, the New York firm of Hass and Götz advertised that it specialized in importing “Black Forest wall clocks, musical marble and alabaster clocks (Stockuhren), Viennese mantel clocks, high quality alarm clocks, and kitchen clocks (Küche-Standuhren).” This firm also sold clocks to dealers in other cities. During the 1840s, Philadelphia clock dealer J. G. Syz ran a similar business specializing in Black Forest musical clocks. Judging from newspaper advertisements and directories, musical instrument dealers similarly imported vast quantities of German products. In the 1819 Philadelphia directory, George Willig reported that “Grand and Square German Pianos [of] superior quality with Turkish Music [Janissary attachments]” and “Grand and Square English Pianos [of] superior quality” were available at his shop, the “Musical Magazine” on Chestnut Street. Similarly, the Philadelphia firm of A. W. Bolenius and Company offered a huge assortment of musical instruments “from various German manufacturers.” Well over fifty types of instruments are enumerated in Bolenius’s 1838 advertisement.[30]

Apparently, the large-scale importation of German and English pianofortes threatened American producers. In 1820, the Philadelphia piano-making firm of Loud & Brothers remarked that “business formerly was more thriving than it is at present owing to the Exertions that the Importing of Foreign Manufactures are making to crush (if possible) this rising manufacture of American Arts.” Loud & Brothers believed that an increased tariff was needed to protect American piano makers.[31]

Given the wide variety of objects imported and consumed by both natives and German-Americans, clearly German-made or -processed goods had a definite appeal in this country. The attraction of such goods is particularly noticeable in the manner in which they were advertised. German products were regularly identified by dealers as such, alongside French and English merchandise. Although the connotation of “German” did not necessarily identify a product as better than its native counterpart or those of other countries, it nevertheless seems to have been associated with high-quality specialty and luxury items.

Design Accommodation, 1820–1830

If Philadelphians considered German items to be on a par with English and French goods, what effects, if any, did this opinion have on domestic products? Were Philadelphians familiar with German design in objects other than those they imported? If so, were Germanic characteristics accepted and encouraged in the production of Philadelphia-made goods? In the case of furniture, the answers to these questions are complex and change over time. First, some Philadelphia consumers were probably aware of German furniture design, at least tangentially. The simple fact that scores of highly skilled Germanic woodworkers poured into the city between 1816 and 1850 meant that there was a direct link between German and Philadelphia design aesthetics.

In furniture design, this connection was further strengthened by the presence of portfolios that immigrant craftsmen brought from Germany. Often used in preparation for their guild examinations, these portfolios contained furniture designs that were commonly saved for future use (see figs. 3, 22).

The aforementioned drawings reveal that most of the cabinetmakers who immigrated to Philadelphia during the 1820s and 1830s were well versed in the late classical design mode known today as Biedermeier. Their presumed familiarity with this style is supported by the fact that the mean age of a German immigrant cabinetmaker was 31.8 years in 1850. Having been born around 1818, most of these artisans grew up with and served their apprenticeships constructing Biedermeier furniture. By the time they became mature craftsmen (in the late 1830s and 1840s) and immigrated to America, they were familiar with the older Biedermeier style as well as the emerging rococo revival taste.[32]

The Biedermeier aesthetic that German cabinetmakers brought to Philadelphia, and to America in general, dominated German furniture production between 1815 and 1835. Originally developed in response to material shortages caused by the Napoleonic wars and as a reaction against the foreign French Empire style, Biedermeier furniture catered to middle-class tastes rather than to those of the aristocracy. Living in what were often small houses or apartments and desiring stylish yet functional furniture, middle-class consumers found the small scale, clean lines, and bold shapes of Biedermeier design appealing. Ornamentation generally relied on meticulously matched wood veneers as opposed to elaborate bronze mounts or gilding. Occasionally furniture makers used black paint as a decorative device to contrast with a light-wood veneer as in figure 4.[33]

The basic design of Biedermeier furniture was often conceived of in a highly imaginative manner. Generally, furniture was thought of as completely frontal in both ornamental and spatial orientation, the sides being totally subordinate to the facade. Within the overall structure of the design, forms were built up out of a series of rectangles or boards placed one atop the other, with little overall integration (figs. 3, 4). Within the context of this basic rectilinearity, a limited number of geometric shapes, such as the arch, diamond, and sphere, were used. Almost invariably, however, such elements were subordinate to the mass of the carcass. In chair design, the emphasis was also frontal, with elaboration generally occurring in the back and slightly canted legs (fig. 5). Only in the most opulent examples did chairs assume an assertive, three-dimensional, sculptural quality.

During the 1830s, this emphasis on planarity, frontality, and conservative ornamentation changed as rococo revival designs became popular. Increasingly, the rectilinearity of Biedermeier furniture was broken by curvilinear elements, while plain surfaces were covered with carving. Mahogany, which had been largely displaced by native, light-colored fruit- and nutwoods early in the century, reasserted itself along with rosewood. By 1850, most traces of Biedermeier design had vanished from German furniture, especially in urban centers (see figs. 30, 33, 34).

Although Biedermeier design drew most of its inspiration from the fashion centers of Vienna, Mainz, and Berlin, the style relied significantly on two other sources. The first and most important was the imagination of the craftsman. Unlike American cabinetmakers, German woodworkers had to prove their proficiency in drawing during their apprenticeships. For their final examination, they had to create a Meisterstück of their own design. This emphasis on individuality, coupled with the fact that few German patternbooks appeared before 1835, is reflected in the imaginative and often eccentric character of much Biedermeier furniture (see figs. 3, 6). Creative combinations of bold shapes are often employed, and architectural elements are sometimes incorporated in a nonarchitectural manner. Details such as concave drawer fronts and inverted feet appear frequently, enlivening the composition.[34]

French and English designs also inspired early nineteenth-century German furniture. Because French forces occupied large areas of central Europe during the Napoleonic wars, Germans were well aware of their styles and products. Much of the German aristocracy adopted the French Empire taste for their residences, often ordering directly from Paris or commissioning German craftsmen to execute French designs. Despite some affinities between the Biedermeier and French Empire styles, including appreciation of highly figured veneers, French late classical designs were primarily confined to the nobility in central Europe and thus were not ordered on a large scale in that part of the Continent.

The influence of English furniture on the Biedermeier style was probably more significant, particularly with regard to German design in America. Because English styles had been popular in Germany since the second quarter of the eighteenth century, patternbooks by designers such as Thomas Chippendale, George Hepplewhite, Thomas Sheraton, George Smith, and Rudolf Ackermann were relatively common in northern Europe. Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book, for example, appeared in German in 1794. English furniture, much of which arrived in the northern port cities of Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck, was another important design source for German artisans. Although some German cabinetmakers used these sources to produce copies of English furniture, most simply adopted specific details, such as swags and classical architectural elements, just as they had with French designs.[35]

It was this Biedermeier aesthetic, with its strange geometric core and French and English undercurrents, that German woodworkers brought to Philadelphia and other American cities between 1816 and 1850. Were these ideas accepted and encouraged, or were they rejected? During the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the complete acceptance of German designs in Philadelphia was rare. Given the slow pace of German immigration (compared to that of the 1830s and 1840s), it seems only logical that Teutonic designs would be subordinate to Anglo-French styles; however, exceptions do exist. As in other American cities, a small though potentially significant amount of German furniture arrived in Philadelphia during this period.[36]

Two fall-front secretaries are representative of these German imports. The example shown in figure 6 descended in the Oppenheimer family of Bedford, Pennsylvania. With its crowning architectural structure, unusual placement of sphinxes, and temple interior, it is totally Biedermeier in character. A Continental origin is suggested by the presence of a wide variety of woods, including oak for the drawer linings, and maker’s marks in German. Secretaries like this example could have arrived with German immigrant families or have been purchased from a Philadelphia importer.[37]

Stephen Girard (1750–1831) purchased the musical fall-front secretary illustrated in figure 4 from Simon Chaudron in 1804. Despite its having been sold by a French immigrant, this secretary has always been considered a German product. Its history and strong adherence to Biedermeier design, evident in the secretary’s highly figured, light wood veneers, contrasting black reserves, and eccentric architectonic quality, supports this conclusion. The fact that it cost $650 and was owned by America’s wealthiest individual makes the secretary particularly noteworthy, since many of Philadelphia’s elite must have seen it in Girard’s home.[38]

In addition to importing a small amount of Biedermeier furniture early in the century, Teutonic craftsmen also produced some isolated but typical examples of German late classical furniture. The coffer from the Hermann Benevolent Brotherhood is a fine example (fig. 1). Made in 1816, just as German immigration to the United States revived, this chest displays the Biedermeier predilection for visually compartmentalized space in its use of light wood banding and a layered top. With their white color and bold shape, the spherical ivory feet add to the diversity of the design. The fall-front secretary illustrated in figure 7 also attests to the Teutonic presence in Philadelphia. Although Germanic in every detail, including its use of geometry, outward curving bottom drawer front, eccentric rectangular feet, and decorative use of the wood grain, its yellow poplar secondary wood and history point to a Philadelphia origin.[39]

Despite the existence of imported and American-made Germanic furniture in and around Philadelphia, the complete acceptance of German design was rare before 1830. The question must therefore be asked—What were the German cabinetmakers of Philadelphia producing? Although this query may never be answered conclusively, it is likely that German craftsmen drew upon those aspects of Biedermeier design that were closest to contemporary American taste in order to produce furniture virtually indistinguishable from that of native-born cabinetmakers. This aesthetic assimilation could have been achieved in several different ways. An immigrant furniture maker could, for example, have taken a Biedermeier design and eliminated its distinctive German features. The addition of locally popular details, such as carving and mahogany veneers, would have resulted in a product that melded into the furniture mainstream. The more complicated chairs illustrated in figure 5, for example, may not have appealed to Philadelphia consumers; however, the simpler forms are quite close to popular regional designs.

This process of design synthesis and accommodation is evident in Philadelphia piano cases of the period. A square pianoforte case by the Danish-born and German-trained artisan Emilius N. Scherr (1794–1874) is virtually identical to those produced by Loud & Brothers of Philadelphia (figs. 8, 9). In building or commissioning a case that so closely approximates that of a well-established Anglo-American firm, Scherr relied upon the basic similarities between the German and English traditions of square pianoforte case design to produce a saleable product. The addition of carving typical of American pianos but foreign to Germanic ones was a clear concession to local tastes; however, it did not significantly alter the maker’s mental image of what a piano should look like or affect the design of the musical works. The fact that Philadelphia pianos almost invariably follow popular English designs, even though 50 percent of the piano makers in the city were German born by 1850, attests to the success of this process.[40]

Immigrant craftsmen also maintained continuity with their Continental training by producing Germanic forms derived from French and English designs rather than from purely Biedermeier ones. Two pier tables in the French style—one Philadelphian and the other German (figs. 10, 11)—have similar shaped bases, scrolled supports with leaf decoration, concave cornices, marble tops, and veneered surfaces. English-style card tables made in Philadelphia and Germany illustrate similar parallels in their overall form, composition, and decoration (figs. 12, 13). As these examples suggest, many German furniture makers arrived in Philadelphia with a stylistic vocabulary sympathetic to local tastes.

The Fall-Front Secretary: A Case Study in European Influences

Of all the furniture forms produced in Philadelphia, none reveals how Germanic artisans accommodated local tastes more clearly than the fall-front secretary. Having obtained its mature form in the work of Jean-François Oeben (ca. 1721–1763), a German cabinetmaker working in Paris, the fall-front secretary soon became popular on the Continent. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the form was especially fashionable in countries dominated by Biedermeier design—Germany, Austria, and Scandinavia. When required to design and build a piece of furniture for their guild examinations, apprentices almost invariably chose a fall-front secretary.[41]

Since this form was not popular in England, its appearance in Philadelphia is probably the result of Continental influence. As Stephen Girard’s secretary (fig. 4) shows, some Continental imports were present in Philadelphia during the early nineteenth century. In fact, the designs that German craftsmen (and perhaps French immigrants as well) brought to America were generally dominated by this particular furniture form (see figs. 3, 22).

The fall-front secretary was very fashionable among the upper class of Philadelphia, even though it never displaced the secretary-bookcase. Besides Girard, the Gratz, Kuhn, and Gilpin families owned examples. The form was also included in The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Ware (1828). According to this book, the labor cost for building a fall-front secretary (described as a “French Secretary”) was $22. The survival of more than a dozen early examples further attests to the form’s acceptance in Philadelphia. Although cabinetmakers in other American cities also produced fall-front secretaries, the form appears to have been more popular and more varied in Philadelphia. Boston secretaries, for example, almost invariably have strong French overtones, whereas those from Philadelphia have English, French, and/or Germanic details.[42]

The striking diversity within the Philadelphia group reflects the various foreign influences present in that city. Several of these secretaries are extremely French in character. The one shown in figure 14 relates to a design by French cabinetmaker Pierre de la Mésangère (1761–1831) in having classical columns, capitals, bases, and arches that are architectural rather than purely representative. Like their Continental counterparts, these Philadelphia secretaries in the French style have restrained, unified designs and classical proportions. Most have columns that extend from the feet to the cornice, framing the facade and supporting the marble top. The use and placement of ormolu mounts further unifies the composition, those at the top echoing those at the bottom.[43]

The Philadelphia Biedermeier secretary illustrated in figure 7 provides an interesting contrast to the preceding examples. Despite having flanking columns, its visual emphasis is on individual parts rather than on unity. The columns, curved bottom drawer, square feet, multilayered cornice, and escutcheon-shaped recess function as distinct parts, competing for attention. The repeated use of horizontal bands such as those between the drawers and in the cornice further compartmentalizes the facade.

Several other Philadelphia secretaries also have a strong affinity with German design. Similarities in proportions and construction indicate that eight are from the same unidentified shop (fig. 15). As with the example illustrated in figure 7, all of the pieces in this group reflect the Germanic propensity for imaginative design in which the facade is an amalgamation of parts, not a unified whole. On the secretary shown in figure 15, the columns do not extend from base to cornice, as in a typical French example, but rather stop halfway. The use of columns over pilasters, the orientation of the fall (horizontal) and doors (vertical), the contrasting burl-veneers, and the emphatic horizontal banding at the top, middle, and bottom all serve to compartmentalize the facade. Beyond this lack of unity, the relationship of these secretaries to German aesthetics is further revealed in the imaginative use of an architectural structure at the top. The secretary shown in figure 15 is one of the more conservative examples, featuring a stepped plinth that was likely meant to support a clock. Others in this group are crowned with more elaborate devices, including temple-like forms with recessed lunettes in their facades. As surviving German secretaries and patternbooks (fig. 16) demonstrate, the placement of such structures on a sloping base is in keeping with Biedermeier taste. Another Germanic trait is the frequent use of light burl-veneers on both interior and exterior surfaces (fig. 20). Light-wood furniture was especially prevalent in northern Germany and Scandinavia (see fig. 4). The back construction of these Philadelphia secretaries (fig. 17) also relates to central European work. All have two vertical panels separated by a wide muntin. The panels are not framed by rails or stiles but are nailed to the top and into rabbets in the sides. This structure was dominant in Germany during the period.[44]

The shop that made these eight secretaries must have been a significant one given the sophistication of its products. It either influenced or produced some of the most elaborate case pieces ever made in Philadelphia, including a brass-inlaid sideboard with knifeboxes, a fall-front secretary, and a secretary with wings (fig. 18) created for the Gratz and Kuhn families between 1815 and 1825. Traditionally, scholars have attributed these pieces to Joseph B. Barry (ca. 1757–1839), a prominent Philadelphia cabinetmaker who advertised brass-ornamented furniture and operated a large shop that employed European journeymen. Regardless of whether these objects came from his shop, they may well represent the work of a German cabinetmaker.[45]

As with the preceding group of Germanic secretaries (see fig. 15), the secretary with wings (fig. 18) has a beveled horizontal fall and two beveled vertical doors below. The facades of the Germanic secretaries and case pieces in the Gratz and Kuhn group are also compartmentalized in related ways. On the latter pieces, strong horizontal bands divide the surface into upper and lower halves, while vertical pilasters break in the middle. Invigorating the surface are cut brass panels and stringing inlaid into ebony or mahogany. A similar effect is achieved in the previous group with light-wood burl-veneer (see fig. 15). The interiors of the Gratz and Kuhn secretaries are closely related to those of the eight secretaries (figs. 19, 20). Both feature banks of drawers surmounted by pigeonholes arranged on either side of a central space consisting of a lower open compartment, central section with banded columns, and crowning arch.

The construction of the Gratz and Kuhn case furniture is related but not identical to that of the Germanic secretaries (see fig. 15). All of these objects have mahogany drawer linings and case sides that are flat (except for the continuation onto the sides of the three horizontal bands from the facades); however, the backs of the Gratz and Kuhn pieces have framed-in horizontal panels. Given these structural differences, it would be premature to attribute the Germanic secretaries to Barry’s shop or to dismiss him as a possible maker. These secretaries and the Gratz and Kuhn furniture do not, furthermore, negate the possibility that other European traditions influenced them. Not only was brass inlay used both on the Continent and in England, but furniture historian Deborah Ducoff-Barone has identified English and French parallels with the Gratz and Kuhn secretary and secretary with wings. The latter example relates to a Mésangère design for a secretary with wings as well as to one for a fall-front secretary with similarly organized interior (fig. 21).[46]

With its undercurrents of English and French design, central European late classical furniture may also have inspired the Germanic secretaries and Gratz and Kuhn pieces. German immigrants clearly introduced related designs for secretary interiors. Cabinetmaker Joseph Fiedler had a sketch of a secretary with an interior similar to Stephen Girard’s when he arrived in Pennsylvania in 1819 (figs. 4, 22). Both interiors feature banks of drawers, banded columns, an arch, and a space between the lower two drawers. It is, therefore, entirely possible that the design of the Germanic secretaries and Gratz and Kuhn furniture owe more to their maker’s imagination and training than to printed patternbooks or European prototypes.[47]

Other Philadelphia fall-front secretaries have Germanic features, but they are only tangentially related to the group of eight secretaries and the brass-inlaid pieces. The secretary illustrated in figure 23 has been attributed to the French immigrant cabinetmaker Michel Bouvier (1792–1874) for years. Although no conclusive evidence for this attribution is known, the secretary appears to have been made by an artisan trained on the Continent. One of the interior drawers is numbered “7-” in the Continental fashion, and the basic unity of design and paired, full-length columns are very French in character. The presence of contrasting burled maple veneer in the interior and a pedimented top, however, links this piece to German design. Only rarely do such pediments occur in French furniture, as opposed to central European work. If Bouvier did make this secretary, his pediment may have been influenced by the popular Biedermeier forms of rival Philadelphia shops.[48]

This survey of fall-front secretaries made before 1830 reveals the complicated nature of furniture design in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Because the city supported a variety of foreign- and native-born cabinetmakers and because customers accepted or rejected culturally specific design elements in the marketplace, Philadelphia craftsmen produced a wide range of forms. At the ends of this spectrum were quintessentially French and German pieces. In between were forms featuring German, French, and English details in varying degrees and combinations. After 1830, the picture becomes clearer, at least where German influence is concerned.

Late Classical Design

The late classical style of the 1830s and 1840s, known today as “pillar and scroll,” is often characterized by designs that stress the compartmentalization of decoration and an eccentric mixture of curvilinear and rectilinear shapes. In this late phase of neoclassicism, the emphasis is on the wood itself and on solid, heavy forms. Carving is de-emphasized, and gilded decoration appears infrequently. The sources for this style were undoubtedly international. So-called “Regency” and “French Restoration” styles both played a role, but perhaps the most important influence was late Biedermeier design from Germany.

Common German conventions that appear in Philadelphia furniture of the period include an emphasis on veneered surfaces, the use of various geometric motifs, and overall lack of visual unity. Specific decorative motifs such as large lunettes and diamonds (often in conjunction) are found on both Philadelphia and northern European furniture of the period. In the case of the Philadelphia work table shown in figure 24, the compartmentalization of the carved, veneered, and applied ornaments (gadrooning, leaves, fans, diamonds, and bosses) and of the lyre and components of the base is analogous to German and Danish work (see fig. 3). Furniture in which flat and curved, and projecting and recessive surfaces are dramatically juxtaposed is also found in both of these countries. A Philadelphia chest of drawers reflects this Germanic aesthetic (fig. 25) by having a facade that is divided into distinct horizontal bands unified solely by the grain of the wood. The upper drawers are convex, whereas the molding above them is concave. The middle drawers recede, and the bottom one protrudes below another curved molding. This same aesthetic is apparent in contemporary Philadelphia pier tables. The example illustrated in figure 26 has several visually distinct parts—marble top, scrolled supports, back, marble shelf, feet—unified solely by mahogany veneer. Although the plinth feet seem odd, they are fairly common in German work (see fig. 3).

As a contemporary plate from Wilhelm Kimbel’s Journal for Cabinetmakers and Upholsterers (1835–1853) suggests (fig. 27), the secretary shown in figure 28 is strikingly close to German prototypes. Not only is the arrangement of the three lower drawers and fall the same but the cornice profile, concave framing molding, and rounded corners are virtually identical. Both facades also feature highly figured veneer.

Besides making furniture that emphasized veneered surfaces, bold and often eccentric shapes, and a lack of visual unity, German craftsmen probably encouraged the use of native light woods in Philadelphia. The rather sudden popularity of light-wood furniture occurred around 1830, just as German woodworkers began to enter the city in large numbers. In that year, Walter Pennery received an “honorary mention” at the Franklin Institute for a light-wood bureau he made in the shop of John Jameson (fig. 29). The judges described the piece as “a very beautiful specimen of maple work.” Four years later, the judges commended a Loud & Brothers upright piano “for its good tone, and truly tasteful and splendid exterior, the case being made of American bird’s eye maple.” Encouraged by such awards, some Philadelphia shops began to specialize in light-wood furniture. The most notable was that of native-born cabinetmakers J. and A. Crout. From the founding of their shop in 1833 through the 1840s, they repeatedly received accolades for their “American-wood furniture” from the Franklin Institute. In the 1841 issue of the Public Ledger, they advertised a “splendid assortment of furniture, manufactured from a selection of American wood, such as has never before been introduced to the American public, and which, for beauty and design, cannot be surpassed by any cabinet ware manufactured from Imported Wood.” By 1850, the Crout shop was producing $10,000 worth of light-wood furniture annually.[49]

Although light-wood furniture was made in France and England during the early nineteenth century, it was more prevalent in Germany and Scandinavia. In Germany, it was seen as a nativist statement distinguishing German taste from that of France, where mahogany dominated. Some of the German cabinetmakers who came to Philadelphia probably worked with native American light woods in their homeland. In 1841, Frankfurt am Main lumber merchant Carl Küchler advertised that his warehouse contained “foreign furniture woods—including Mahogany, Palisander (or Jacaranda), Lemon, Zebra, American Maple, Amaranth, veined Amboina, veined Swedish, wild and high-quality Cedar, Ebony, Palmwood, Boxwood, and Pocked wood, etc. in blocks, planks, and veneers.” American woods were so esteemed that a Viennese piano maker named Schneider imported American maple to cover the grand piano he sent to the Crystal Palace in 1851. In view of the wood trade between America and central Europe, the continuation of a tradition of light-wood furniture using American wood would have been a logical step for many immigrant German cabinetmakers.[50]

Although the sudden popularity of light-wood furniture in Philadelphia around 1830 may also have stemmed from the rarer English and French usage, surviving furniture usually points to a Germanic connection. For example, the outward sweeping base and overall lack of visual unity of the dressing bureau by Walter Pennery suggests that he was influenced by an immigrant German craftsman (compare fig. 29 to figs. 25, 26).

The Rococo Revival Style

In America, the introduction of the rococo revival style paralleled that of the late classical style. Although Parisian designers first revived this mid-eighteenth-century taste, immigrant German craftsmen were largely responsible for introducing rococo revival designs and construction techniques in this country. By the early 1830s, curvilinear, florid carving began to appear on rectilinear Biedermeier forms. Within a decade, much of the furniture produced in central Europe was fully rococo revival in style (figs. 30, 33). As a result, those hundreds of cabinetmakers and carvers who immigrated to America in the late 1830s and 1840s must have contributed significantly to the emergence of the style in this country. Not only were they familiar with French and other Continental design sources, but they knew how to execute them. German cabinetmaker Johann Heinrich Belter (1804–1866), for example, arrived in New York around 1840 and built a thriving business making furniture in the rococo revival style. Many contemporary products from other American shops also reveal a German hand. Pages from a New York, German-language newspaper found under the rear upholstery panels of a late 1840s rococo revival sofa (fig. 31) suggest that it came from a shop with German workers skilled in laminating and carving wood. In Philadelphia, several immigrants such as Charles H. L. Goehmann (d. 1866) worked in the rococo revival style at mid-century (fig. 32).[51]

Along with the ever-increasing waves of craftsmen who immigrated to America during the 1830s and 1840s, the rise of German patternbooks provided yet another avenue for the transfer of designs (especially rococo revival and, to a lesser extent, Gothic revival) to America. Although furniture designs had been published in Germany before 1830, the number of publications increased dramatically during the 1840s and 1850s. Simultaneously, the ability of German publishers to distribute their books throughout Europe and overseas improved markedly as Germany strengthened its international trade ties during the early nineteenth century.[52]

The United States was particularly receptive to German books, including patternbooks and trade catalogues. In Philadelphia, more than fifty dealers advertised as “Foreign and American Booksellers and Publishers” in the early 1840s. Several of these, including George S. Appleton, J. Dobson, George W. Mentz, J. W. Moore, J. G. Ritter, and L. A. Woollenweber, stated that they specialized in German books. Newspaper advertisements also reveal that New York importers had established strong connections with German publishing centers, especially Leipzig and Stuttgart, by the early 1830s. In 1843, New York importer William Radde (whose Philadelphia agent was C. Rademacher) announced that he was associated with the prominent book clearinghouse of Cotta in Stuttgart and could supply a wide variety of books.[53]

Judging from their frequent appearance in advertisements, patternbooks and technical treatises were a significant part of many dealers’ businesses. In 1850, the Philadelphia firm of Zeitz and Company reported that they “import to order and have constantly on hand a very large assortment of goods. . . . books in German, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Italian, Spanish and other languages; Classics, Dictionaries, Grammars, Vocabularies, School, Juvenile, Picture, Drawing and Model Books for Architects, Cabinet, Carriage, and other manufacturers.” J. G. Wesselhoeft, perhaps the largest German book importer in the country, regularly advertised design and technical books in his newspaper, Die Alte und Neue Welt, throughout the 1830s and early 1840s. In 1840, he described the technical works kept in stock as “a large collection of highly useful works for merchants, manufacturers, artists, craftsmen, farmers, and housekeepers.”[54]

Although the subjects covered in Wesselhoeft’s advertisements ranged from vinegar to porcelain production, most of the technical books he imported pertained to architecture, textile dyeing, metalworking, and woodworking. In addition to stocking inexpensive, multivolume technical books by J. C. Leuchs (Nuremberg), Carl Matthaey (Weimar), and Marius Wölfer (Leipzig), Wesselhoeft advertised Leuchs’s Recipes for Preparing Cabinetmaker’s Glue (1839) and Stone Veneer: Its Preparation and Advantages Over Wood Veneer (ca. 1839) and Matthaey’s Designs and Descriptions of the Newest Styles for Artists and Craftsmen (3 vols., 1831–1835) and The General Polytechnical and Trade Newspaper (1834–1840). Along with these works, Wesselhoeft probably had other companion volumes, such as Matthaey’s The New Teaching, Pattern, and Ornament Book for Cabinetmakers and Carpenters (1840), New Patternbook for Wood, Horn, and Bone Turners (1841), and New Idea Magazine for Luxury, Furnishings, and Draperies (1841). Wesselhoeft also advertised Wölfer’s treatises on house and barn building, and he may have carried the same author’s The Carpenter and Cabinetmaker (1828) (fig. 16), Newest London, Parisian, Viennese and Berlin Window, Bed, and Furniture Decorations (1829), and Model and Patternbooks for Carpenters and Cabinetmakers (1832).[55]

In addition to those titles that are known to have been imported, internal evidence in other German patternbooks indicates that they were marketed in America. The Neues Journal für Möbelschreiner (New Journal for Cabinetmakers) by J. W. Hanke (1841) (fig. 33) contains advertisements in German and English. The German one lists woods and other materials available at Carl Küchler’s warehouse in Frankfurt am Main, whereas the English one concerns steel pins and uses an Anglicized version of Küchler’s name (Kuchler). Some of Küchler’s “portrait pins,” furthermore, had likenesses of Lafayette and Washington on them, proving that the advertisement, and hence Hanke’s furniture designs, were intended for an America audience.[56]

The patternbook that most clearly demonstrates a connection between German and American design between 1830 and 1850 is D. Freudenvoll’s Neuestes Mainzer Moebel-Journal (New Mainz Furniture Journal) (1846–n.d.) (figs. 30, 34). Freudenvoll’s son Charles (Carl) (b. 1812) came to Philadelphia in the late 1830s and was active for at least a decade. Charles’s records and the title pages of Neuestes Mainzer Moebel-Journal indicate that he sold his father’s lithographic designs at his shop at 9 Gaskill Street. D. Freudenvoll also distributed his designs in Mainz, Paris, Brussels, and London. By 1847, his success in Philadelphia induced him to send his other son, John, to Boston to oversee the journal’s distribution there (John’s cabinet shop was at 10 Middlesex Street). The fact that the Boston distribution center opened the same year that the London one closed suggests that Americans embraced German rococo revival designs more closely than did the English.

Given the trilingual nature of the journal (marketed in America and England as the New Magazine for Cabinet-makers and Upholsterers) and its fashionable plates, Freudenvoll’s book probably had an impact on rococo revival design in this country. Unfortunately, so little is known about early rococo revival furniture in America that the extent of the journal’s influence is hard to evaluate. Some parallels are apparent, however, since several fall-front secretaries from Philadelphia are closely related to Freudenvoll’s designs (fig. 34).[57]

Conclusion