Side chair (one of a pair) labeled by Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 38 3/8", W. 23 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, M. and M. Karolik Collection.)

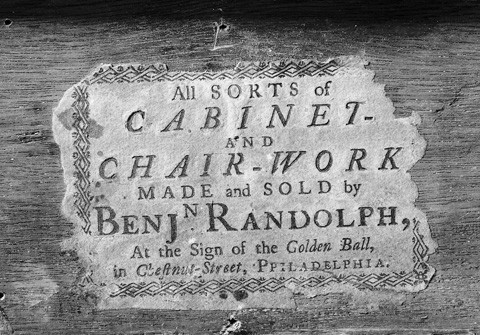

Detail of the label applied to the inside rear rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of veneer repairs to the front rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 1.

Side chair (one of a pair) labeled by Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 38 3/8", W. 23 3/4", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

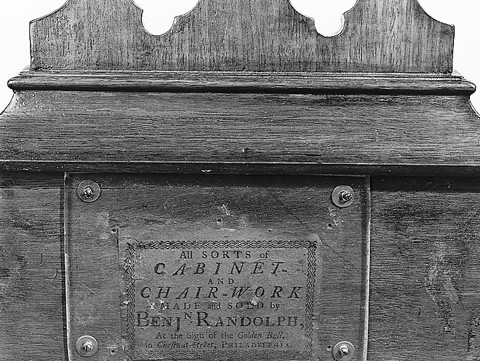

Detail of the label applied to the inside rear rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear corner block of the chair illustrated in fig. 4, showing screw holes and impressions of an angle-iron plate. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 37", W. 29 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 33 3/8", W. 24 1/4", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the front rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear end of the side rail shaping and through-tenon of the chair illustrated in fig. 1, showing two-piece construction.

Armchair, probably Delaware, 1760–1780. Mahogany. H. 39 1/2", W. 24 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The armchair is from the same set as the side chair illustrated in fig. 12.

Side chair, probably Delaware, 1760–1780. Mahogany. H. 38 11/16", W. 23 13/16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has a history of ownership in the Crowe family of Odessa, Delaware.

Detail of the inside rear rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the carved volutes.

Detail of the crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 12, showing evidence of removed volutes.

Detail of carved ornament on the splat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of carved ornament on the splat of the side chair illustrated in fig. 12, showing abraded carving.

Philadelphia furniture maker and carver Benjamin Randolph (1721–1791) attracted considerable interest among early American furniture dealers, collectors, and scholars in the 1960s and early 1970s. Historian Nicholas Wainwright advanced Randolph’s name as maker of some of the most ornate Philadelphia furniture in the rococo style in his otherwise excellent study of the house and furnishings of John and Elizabeth (Lloyd) Cadwalader. Art historian Robert C. Smith linked Randolph’s name to the grand traditions of eighteenth-century European classicism in his 1971 article on Philadelphia furniture busts and subsequently to a very ornate desk-and-bookcase.[1]

Two studies published in the 1970s contributed to replacement of Randolph’s name in the number one position with that of Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck. In his influential and valuable book American Chairs: Queen Anne and Chippendale (1972), John Kirk argued that a chair bearing a Randolph label and its mate—both in the Karolik Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—were out-of-period (figs. 1, 2). As a consequence of this analysis, both objects were removed from exhibition and have remained in storage since. Kirk also hypothesized that the design of these chairs, heretofore associated with Randolph, was more likely the work of Affleck. Seven years later, an article titled “A Methodological Study in the Identification of Some Important Philadelphia Chippendale Furniture” revised prevailing opinion about Randolph’s involvement with a group of furniture commissioned by Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader, again replacing Randolph’s name with Affleck’s. Historical arguments advanced in the aforementioned article were reinforced by new scientific technologies applied to furniture scholarship in a 1989 study at Winterthur. More recently, the focus on cabinetmakers such as Affleck and Randolph has yielded to interest in individual carvers and carving schools.[2]

Trends and preferences exist in furniture history scholarship and influence how physical and written evidence is evaluated and interpreted. These scholarly currents respond at least partially to certain published works and unpublished discoveries that enter the mainstream of generally accepted opinion. As the corpus of American furniture history grows, it is useful to revisit earlier works upon which today’s scholarship continues to build. On occasion, intervening research may substantially challenge and change earlier findings. When such information comes to light, it seems appropriate to correct distortions of the historical record so that errors are not compounded in further research.

In the case of the Randolph labeled chair, the bibliographical record began with its feature publication in Edwin J. Hipkiss’s, Eighteenth-Century American Arts: The M. and M. Karolik Collection (1941). A decade later, Albert Sack described the chair as “the ultimate of this type and one of the greatest of the Philadelphia chairs” in Fine Points of Furniture: Early American, his popular guide to evaluating early American furniture. John Kirk’s detailed argument that the chairs are out-of-period stands in sharp contrast. He did not express doubts about the authenticity of the printed label, but he advanced a modest argument that it was fraudulently applied, a circumstance that must follow logically if the chair is not period.[3]

Patricia E. Kane’s catalogue of the chair collection at the Yale University Art Gallery, published in 1976, acknowledged the doubt cast by Kirk’s analysis but did so in a noncommittal fashion. She stated that “the authenticity of that label has been questioned” but provided no references to her sources and supplied no opinion of her own. She also noted that “the present whereabouts of another labeled example is not known, leaving the Randolph attribution somewhat in doubt.” This second chair, illustrated in Joe Kindig, Jr.’s, advertisement in the January 1943 issue of Antiques, appears to be identical to the Karolik chair. Without adequate explanation, the reader must infer that Kane’s reluctance to state an opinion was related to a concern that the label of the Kindig chair may have been removed and applied to the now problematic Karolik chair.[4]

The Karolik chair reappeared as “one of the most controversial pieces of American furniture” in an exhibit of art fakes and alterations at Yale in 1977. Francis J. Puig’s catalogue entry for the chair increased the uncertainties surrounding this object by placing it in a “questionables” category and offering several possible interpretations: The chair is fraudulent, but the label is authentic; the chair is an altered revival form; or the chair is a genuine Philadelphia example by another maker. His reference to Kirk’s book to document all of these possibilities is inaccurate. Kirk developed a single argument— the chair is fraudulent, but the label is authentic.[5]

This study revisits the controversy to lay uncertainty to rest. It offers yet another point of view—that both the chair and its label are genuine. Misunderstandings of the chair stem from misinterpretation of physical evidence partially altered and obscured by restorations. Although reinstatement of this documented example of Randolph’s work may interest only some students of early American furniture, the causes of these erroneous interpretations have broad application.

Kirk’s argument that the labeled Randolph chairs are out-of-period relied upon his comparisons of the pair to other Philadelphia examples in the rococo style. More specifically, he used five similar chairs at Yale as a “control group” and the primary base of comparison. Kirk expressed his argument as sixteen points of difference from the control group and from other contemporary Philadelphia chairs and chairmaking practices. His points, which combined objective and subjective observations of physical evidence, do not appear to follow any particular logic; but, in total, they are daunting. His objective evidence focused on details of construction; the subjective observations addressed issues of design. Several points identified apparent departures from all known practices, whereas others cited practices that are merely infrequent.[6]

Generally, objective or quantifiable evidence is more persuasive and comprehensible than subjective or qualitative evidence. Although the majority of Kirk’s observations belong in the objective category, several addressed condition issues of only modest importance. He noted, for example, that the corner blocks on the chairs are of “new stained pine” and their seat frames “are of oak, not nearly as common as pine,” suggesting that they too may be replacements. The carved brackets for each of the front legs were also called into question because they have wooden plugs covering nails or screws rather than exposed, wrought nails. Although each of Kirk’s observations represents a fair and accurate assessment of condition, none casts doubt upon the age of the chairs. Replacement of all corner blocks and resecuring of all brackets indicates that each chair must have been partially disassembled at some time. Even so, there is no indication that the knee brackets or other chair parts are replacements.

Certain construction features of the front rails are more worrisome. Their decoration incorporates an important detail that deviates from known Philadelphia furniture-making practices. The front rails have C-scroll appliqués set opposite one another to create a serpentine line, and they are undercut below. Undercutting preserved the structural advantages of large tenons while providing a lighter appearance. On Philadelphia rococo side chairs, the front and side rails are typically undercut in a straight line ending in decorative hollows (quarter rounds) or ogee curves, whereas rear rails are seldom undercut. Although many of these chairs have ornaments on their front rails—shells, scrolls, leafage, flowers, cartouches—the designs are either carved in relief or applied. Kirk objected to the Randolph chairs because their decoration features both techniques; the C scrolls are applied, and their upper edges are accentuated with a groove cut into the rail. Moreover, additional small pieces of wood are glued to the backs of the scroll volutes to reinforce them where they drop below the bottom edge of the front rail. Although eighteenth-century furniture makers often glued wood to achieve required dimensions, these tiny laminations have no known parallel in Philadelphia chairmaking. They suggest that wood-dimension deficiencies occurred after assembly rather than as an intentional step.[7]

Another problematic feature, not described by Kirk but noted by others, is the presence of small veneered fills or repairs at the extremities of the C scrolls (fig. 3). These repairs, whose purpose is not immediately apparent, are identical on both sides of each chair. They also appear on the labeled Randolph chair advertised by Kindig and on its mate (figs. 4, 5). Kindig purchased both chairs from Francis P. Garvan (the pioneer collector who gave part of his collection to Yale in honor of his wife, Mabel Brady Garvan) and subsequently sold them to another important collector, Reginald Lewis. The present owner acquired the chairs at the Lewis sale in 1961.[8]

These additional chairs shed virtually no light on Kirk’s argument. Since they are so nearly identical to the ones in the Karolik Collection, they merely extend the number of chairs in question. All four examples are constructed exactly the same. Their overall dimensions and component dimensions also match, indicating that they were laid out with the same templates. The Kindig chairs are stamped “I” and “II” on the inside tops of the front rails; the Karolik chairs are numbered “III” and “IIII” in the same location, suggesting that they may all be from the same set. Similarly, the condition of each pair, including the problematic front rail decoration, is the same with the exception that the Kindig chairs were refinished more recently. Subsequent to their manufacture, all four chairs had their seat rail joints reinforced with iron braces and screws. Although the evidence on all four chairs is partially obscured by the replacement corner blocks—all of which are stained in the same manner—the screw holes are visible on the Kindig examples (fig. 6) and filled on the Karolik ones.

Comparison of the two pairs of Randolph chairs to contemporary Philadelphia examples resolves all of the front rail questions. An armchair and a side chair that differ slightly from the Randolph chairs and from each other indicate that the front rails of the Randolph chairs were merely restored incorrectly and are not evidence of out-of-period workmanship (figs. 7, 8). Collectively, these objects demonstrate unequivocally that the original front rail design of the Randolph chairs consisted of incised C scrolls (fig. 9). Not only are the present appliqués and small glued backings incorrect additions but the enigmatic veneer repairs cover the ends of the original incised design. The outer volutes of the replaced appliqués direct the eye to the knee brackets flanking them, whereas the original incised decoration passed over the leaf tips of each front bracket.[9]

To question why a restorer interpreted this evidence differently, added unnecessary carving, and covered up other decoration is futile. Unlike the revealing patterns of workmanship and design that establish a sound foundation for describing “what,” the information needed to judge “why” is simply insufficient. To project today’s standards of design and restoration back to the time of this repair invites the same error of which the chairs’ repairer is accused, namely, using contemporary approaches to solve problems presented by furniture of an earlier period.

Kirk’s other objections to the Karolik chairs were increasingly dependent upon personal opinion and preference. He noted that the height of the rear through-tenons was almost an inch less than the height of the side rails from which they are cut. These dimensions, he continues, usually are nearly the same. Kirk’s statement is factually correct, but it implies an aberrant practice that reinforced suspicions about the age of the chairs. If typical is defined as a frequency of more than 50 percent, or even 60 or 70 percent, then this feature is atypical; however, viewing eighteenth-century craft traditions in such a dualistic manner introduces the likelihood of misinterpretation. Two different practices, such as using through-tenons or blind tenons, may have existed within a specific furniture-making community; thus, although mid-eighteenth-century Philadelphia chairs with blind rear tenons are rare, they are no less authentic. Similarly, through-tenons cut to a shorter height than the average are no less acceptable in terms of period workmanship.

Another instance where Kirk’s personal preferences adversely affected his interpretation was his analysis of the laminated rear brackets of the side rails (fig. 10). This construction detail, which appears on all four Randolph chairs, has no eighteenth-century parallel. Neither eighteenth-century chairmakers nor modern reproducers or fakers would derive any advantage from gluing up the side rails and rear tenons in this manner: It does not save materials or time. Since all of the chair frames have been taken apart, however, it is reasonable to suggest that this structural anomaly results from a restoration campaign. If the original brackets had been damaged during disassembly, they may have been planed down and replaced with the present laminations. In any event, Kirk’s assertion that the curve of the brackets is “uninspired” diverts attention from more objective considerations—namely, that these elements are probably repairs. The “subtle curve” of the brackets on two of the “control-group” chairs cited by Kirk may be visually more appealing, but their shape does not represent the only “correct” design. Philadelphia chairmakers used a variety of shapes for rear brackets, including both filleted and unfilleted ogees and quarter-rounds (or “hollows”). The laminated brackets on the Randolph chairs may thus imitate the shape of the integral ones that were there originally.

Character of line, liveliness of carving, and other subjective observations are problematic in determining age or authenticity. Surely, such judgments have their place, but they often express personal preferences rather than period tastes and furniture-making practices. In his book, Kirk used his well-trained and highly developed eye to great advantage in many instances, but he failed to enlighten in the case of the Randolph chairs. In support of his belief that these chairs are not period, he stated unequivocally that the “loose, serpentine [front seat rail] line . . . depends for effect upon the applied carving, [and] lacks character. The chair legs lack spring and strength of line.” The front rail “line” has not been altered, and its serpentine shape has parallels on several other eighteenth-century Philadelphia chairs. The notion that this design “lacks character” has nothing to do with the chairs’ age. Similarly, the profiles of the front legs match those of contemporary Philadelphia examples, some of which are considered exemplars of the rococo style. In fact, one can easily agree with Albert Sack’s assessment that “the cabriole legs achieve a perfect curve” by looking past the incorrect repairs and by not allowing hasty and incomplete conclusions to discolor the “magnificence of this example.” Kirk’s analysis of the carving also centered around observations that were more subjective than objective. He stated that “the carving is not alive” and, although “correct in detail, [it is] spiritless in execution, like the work of a copyist.” Whereas Kirk erred in suggesting that the carving is not period, his assessment may have been influenced by surface qualities stemming from previous restoration of the chairs.[10]

An armchair and a side chair in the Winterthur Museum shed light on Kirk’s perspective by showing how our observations can be affected by the changes and alterations that furniture experiences over time. In American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (1952), Winterthur curator Joseph Downs described the armchair as one of the fullest expressions of the Gothic style in Philadelphia (fig. 11). He also noted that the chair lacked through-tenons and was “an exception to the rule of construction.” Its splat design draws directly from English prototypes, although it appears more rigid and lacks some carved detail.[11]

In 1976, Winterthur was offered a set of three side chairs with the same splat design as a gift (fig. 12). Most of the collections staff agreed that the chairs were out-of-period and cited one or more of the following reasons: their splats were too big, and the feet were too small; they lacked through-tenons; their corner blocks were made of mahogany or walnut rather than less expensive local secondary woods; their carving was flat and not representative of the period. Poor finish and bleached color only exacerbated the physical evidence, but no reference was made to the armchair already in the collection.

Comparison of the side chairs to the armchair, however, reveals identical and distinctive construction practices. Shared features include mahogany corner blocks, blind rear tenons, unpinned seat rail joints, and an extra strip of mahogany applied to the inside rear rail below the shoe (fig. 13). This curious addition, presumably intended to stop the back of the slip seat, is constructed of two pieces of wood, joined in the center with a diagonal glue line. The splats of the armchair and side chairs were also laid out with the same splat template, a circumstance that accounts for the slightly oversized proportions of the side chair backs. Their splats were shortened at the base to accommodate their smaller dimensions. Slight variations between these patterns disappear when the template is reversed, indicating that the chairmaker must have flipped the template between tracing each splat.[12]

In Grandeur on the Appoquinimink (1959), John Sweeney reported the provenance of the side chairs and tied them to a document that in turn associates them with the armchair. An 1845 “List of the Residue of the Household Goods of Wm. Corbit, decd., which belongs to his daughter Sarah C. Spruance & Danl. Corbit” recorded “6 best Mahogany chairs & 2 arm chairs—divided—each took 4 of these chairs.” This set must have had special meaning for the two siblings. It was divided equally, but all of the other furnishings were valued so that Daniel could buy out Sarah’s share. The three Winterthur side chairs descended directly from Daniel to the donor. They are numbered “II,” “IIII,” and “V” on the inside top of the front seat rails. The armchair is similarly numbered “VII,” establishing a sequence that supports its identification as part of the William Corbit furnishings divided in 1845.[13]

Further comparisons show how different histories of use and repair have affected the physical properties of the side chairs and armchair. Several repairs executed in a darker mahogany mar the appearance of the side chairs. Their crest rails also reveal that the repairer not only cleaned certain details but removed some of them completely. Although outlining cuts document their presence in the original carved design, small volutes that transform outlining beads into distended C scrolls have been removed from the inside edge (figs. 14, 15).

In comparison to the armchair, the side chair carving appears flat and lacking in richness of detail (figs. 16, 17). Criticism of the Randolph chair carving as “not alive . . . correct in detail but spiritless in execution, like the work of a copyist” fits the Corbit side chairs exactly. As with the Randolph chairs, the Corbit chairs tell a different story. Although the carving on the Corbit side chair is flatter and less detailed than that of the armchair, these qualities do not express the spiritlessness and misunderstanding of a copyist; rather, they probably result from harsh abrasion of the surface. This abrasion, which may have occurred at the same time as the aforementioned repairs and carving alterations, removed texture from the highlights, resulting in some loss of detail.

The precise nature of physical losses on the Randolph chairs is more difficult to assess. Perceptions of carving can be influenced by finish coatings applied to the wood. Subtle shifts in color and texture accentuate the topography of carving by reflecting light differently. Altering finishes changes the visual qualities of carving, which may result in the impression that wood has been lost as well. None of the Randolph chairs has its original finish. The Karolik chairs display a heavy, black, textured coating in crevices and carving recesses. The localized application of this finish and the abrupt transitions between coated and uncoated surfaces suggest that it did not erode naturally but was applied to recapture the appearance of age. Unfortunately, the sharp contrast in surface colors between the dark coating and cleaned areas has the opposite effect and makes the chairs look raw and abraded.

The Randolph chairs advertised by Kindig had their artificially blackened surface removed when they were refinished in the mid-1980s. Although the carving now has a relatively bright, homogenous surface, few would consider it “spiritless” or question its authenticity. In time, the finish on these chairs will age and become more subtle. Similarly, the finish on the Karolik chairs has softened and darkened noticeably over the twenty-five years since they were removed from exhibition.

Criticism of the labels on the Karolik and Kindig chairs must follow if the furniture is deemed to be out-of-period. In support of his claim that a genuine label was applied fraudulently, Kirk noted the lack of color variation on the wood where portions of the label had been lost and the presence of stain, presumably to simulate different oxidation patterns. In raising this issue, Kirk drew attention to an area of furniture connoisseurship that has received too little study. Despite the soundness of his assumptions—that shifts in the color of the wood should mark the original outline of the label—the wood around and underneath the edges of some other eighteenth-century labels fails to yield the expected patterns. Sometimes deep oxidation runs within the boundaries of period labels. The Randolph label on a side chair at Yale is one of several such examples. Also, the extent and rate of color change caused by oxidation itself, which vary with changing environmental conditions and materials, are not well established. The staining on the inside rear rail of the Karolik chair, if it was applied to deceive, does not appear on the labeled example sold by Kindig. Some other cause may have resulted in this staining.[14]

Kirk’s remaining comments regarding the Karolik chairs addressed broader issues of furniture history and interpretation. Citing three other chairs of “stripped-down quality,” he stated that the Karolik examples do not resemble other Randolph labeled chairs and that the “super-refinement of [their] decoration” is out of character. He makes no mention of the labeled mate advertised by Kindig nor of the elaborate, labeled Randolph card table at Winterthur. Manuscript evidence, such as carving bills rendered to John Cadwalader, indicates that Randolph’s shop produced some of the most elaborate work in Philadelphia. The implication that an eighteenth-century shopmaster such as Randolph could not supply furniture of different styles and tastes is at odds with Kirk’s own observation that London-trained Thomas Affleck responded to consumer demands by supplying ornate and simple furniture in the rococo style after his arrival in Philadelphia in 1763.[15]

Rather than standing as contrary evidence, the labeled chairs are physical documents of Randolph’s work and capabilities. They reflect a sense of immediacy that manuscript documentation can only approximate. Who today could describe the mahogany desk-and-bookcase for which Randolph charged Col. George Vaughan the substantial amount of £30 (far more than any single piece of furniture sold by Affleck to John Cadwalader) in 1765? And despite the many obvious differences between the design of the Karolik chairs and the simpler labeled Randolph chair at Yale, further study may one day reveal commonalities. One such shared feature is the unusual pronounced bead that encircles the upper part of the shoe at the base of the splat.[16]

Kirk concluded his discussion of the Randolph chairs with an analysis of their design that led him to suggest that other (authentic) chairs with these same backs should be attributed to Thomas Affleck. This point contributed nothing to the question of age and authenticity but introduced a new element of confusion. Kirk’s reasoning centered around the English qualities of the chair back, the fact that Affleck trained in London, and the existence of similar crest rails on two other chairs attributed to Affleck. Whatever argument is advanced becomes moot upon acceptance of the Randolph chairs as authentic. Regardless of that outcome, however, the argument itself assumes that individual designs or motifs are emblematic of specific makers. Ample scholarship, including Kirk’s own opinion expressed elsewhere, identifies the substantial weaknesses in this approach. Comparing the backs of the Randolph chairs with those having Affleck associations becomes yet another demonstration of the sharing of particular features of chair design—whether proportion or carved motif—throughout the Philadelphia furniture-making community.[17]

The physical evidence of early furniture is at once overtly real and covertly problematic. Detailed analysis of the Randolph chairs underscores how the structure of furniture history is dependent upon subjective observation. The physical evidence that survives today is the accumulation of actions starting from the time of original manufacture through all subsequent changes, intentional and unintentional. Although the layers of activity and their effect on the object can be separated in theory, sorting through whatever physical evidence remains is formidable and uncertain. Is carved work “lifeless” because it has lost its highlights through abrasion or because it was executed by someone copying, and not fully understanding, earlier work? How do surface qualities—altered years ago by refinishing, newly applied but intended to look older, or left undisturbed—influence comprehension of design attributes that lead to authenticating or rejecting a piece of furniture?

Furniture study, as with material culture studies in general, relies on a fundamental premise that made things are shaped and conditioned by people and are therefore expressive of those people’s experiences and thoughts. Furniture and material culture scholars turn this formula around in the practice of history: Because people determine the physical properties of things, these same physical properties can be “read” to investigate the makers and users. Despite the beautiful symmetry of this theory, the language of objects is inexact and ambiguous. One of the many challenges facing students of early American furniture is to dissect the reasoning processes that transform a mute piece of furniture into a set of descriptions and evaluations.

Appendix

For ease of reference, each of Kirk's points are summarized and presented in the order they appear in American Chairs. Original wording is set off in italics; my coments follow.

1. On both chairs all corner blocks are of new stained pine. Corner blocks on all four chairs are replacements. These replacements partially cover screw holes and surface evidence that indicate that iron braces once reinforced the joints. Any evidence of original or early corner blocks is covered by the present replacements.

2. Both seat frames are of oak, not nearly as common as pine. None of the seat frames may be original. Original slipseat frames get separated from the chairs for which they were made for a variety of reasons. Repeated upholsterings and insertion of metal straps or wood boards to reinforce sagging seats are among several actions that accelerate damage to old slip seats. Antiques collectors and dealers occasionally reuse eighteenth-century seat frames from other chairs or merely make new ones.

3. The knee brackets are not applied with large-headed, hand-made nails as was standard in Philadelphia, but show wooden pegs, which are perhaps plugs covering screws (these may be original, not a later addition). Wedge-shaped, hand-forged nails lose their holding ability once they have been loosened. Upon removal of these brackets for other restoration purposes, another fastener, most likely a screw, was used in place of the ineffective nails. The restorer opted to hide the screw head with a wooden plug.

4. The C-scroll carving on the front seat rails is applied, rather than carved from the solid as is standard in Philadelphia. This applied carving is an improper restoration.

5. The outside ends of the C scroll, where they fall below the seat rail, are backed by applied pieces rather than by the extension of the rail itself, not a Philadelphia practice. As with the C-scroll tips that these applied pieces support, they are later and improper restorations. This applied backing was never installed on one side of one of the chairs sold by Kindig.

6. There is a groove carved above the carved scroll edging to make it appear deeper, an unusual practice for the eighteenth century. Originally, this groove did not enhance a decorative motif, rather it functioned alone as the decorative motif. The groove is filled with bits of mahogany where it extends horizontally toward the sides of the chair beyond the present applied C scroll.

7. The rear shaping of the side rails is a separate piece of wood and is an uninspired curve. The present construction of the rear end of each side rail, being made of two pieces of wood, is not original and makes no structural or design sense. For some reason, unknown and perhaps unknowable, the restorer reattached all of the side rails to the rear stiles using this two-piece technique. Determining whether the curve of this inconsequential element is inspired and using that judgment as an indicator of period workmanship is not persuasive reasoning.

8. Points 5 through 7 show an attempt to save wood not customary in Philadelphia or indeed in American work of the eighteenth century. Since points 5 through 7 represent later and improper restorations, they cannot be held to a standard of eighteenth-century practices.

9. The height of the through tenons is 3/4 of an inch less than the side seat rail, whereas usually they are nearly the same depth. Indeed, the majority of through-tenons are approximately as high as the seat rails from which they are cut, but exceptions are common enough that they cannot be used to suggest out-of-period work.

10. The rear of the horizontal shaping, which is a separate piece like a bracket respond, is applied with a through tenon—not normal on Philadelphia eighteenth-century Chippendale chairs. This observation essentially duplicates point 7.

11. The carving is not alive; that is, it is correct in detail but spiritless in execution, like the work of a copyist. Words like “alive,” “spirited,” “inspired,” and “lacking in character” are judgmental labels that may result from detailed analysis. On their own merits, however, they do not convey specific information or values and are not effective in communicating a clear argument or set of reasons that can lead the reader from one level of understanding to another.

12. The front seat rail is shaped to a loose, serpentine line, with its higher corners rather flat, and depends for effect upon the applied carving. The line itself lacks character. This point represents a classic error in subjective reasoning, an approach that projects values onto the object or issue in question. The serpentine line Kirk criticized is a product of eighteenth-century, high-style Philadelphia chairmaking. If the line lacks character, then character cannot be a measure of eighteenth-century work.

13. [In comparison to the Karolik high chest] the legs lack spring and strength of line and the carving is far less inspired; for example, all the leafage springs from one point. This point, as with point 12, is a statement of personal design preference. Aesthetic judgments and comparisons have their place in furniture history and appreciation, but they may lead to incorrect results if they are the sole or primary basis for identification and authentication. The statement about leafage springing from one point, for example, seems undermined by the fact that one of Kirk’s “control” chairs of a similar design also employs this general pattern (see Patricia E. Kane, 300 Years of American Seating Furniture: Chairs and Beds from the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University [Boston, Mass.: New York Graphic Society, 1976], no. 91; no. 90 is another variant).

14. No variation in oxidation appears in areas where the label has worn or torn off, and stain appears to have been applied with the intent to deceive. Authenticating original application of a label on an object is an inexact process. Several other labels on furniture also lack oxidation patterns that outline the original label size. The need to argue that the label was attached fraudulently disappears if the chair is accepted as eighteenth-century work. Although the rear rail has stain on it, the presence of the stain is not sufficient to discredit the label. Intent to deceive is not inherent in the pattern of staining.

15. In approach to design, the chairs do not resemble the other known labeled Randolph chairs. [Other Randolph labeled chairs are of] “stripped-down quality”; [the] “super-refinement of decoration” [of this chair is out of character]. Eighteenth-century furniture makers supplied customers with a variety of designs. Other documented furniture as well as ample written evidence establish that Randolph was capable of making chairs as ornate and well proportioned as these. Despite the obvious differences in design, the Karolik and Yale labeled chairs share the same unusual beaded shoe design.

16. The back design of the Garvan and Boston chairs is English in its breadth and general treatment and corresponds to the Affleck-Penn chair shown in plate 260 of Hornor, . . . [making] it natural to attribute [chairs of this design] tentatively to Affleck. This point contributes little if anything to the question of age and authenticity. The observation is predicated on the assumption that individual designs or motifs are emblematic of specific makers. Ample scholarship indicates that most designs, these among them, were used by more than one maker or shop.

Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), pp. 19–20, 38–39, 116–19, 122–23. Robert C. Smith, “Finial Busts on Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia Furniture,” Antiques 100, no. 6 (December 1971): 900–905; Robert C. Smith, “A Philadelphia Desk-and-Bookcase from Chippendale’s Director,” Antiques 103, no. 1 (January 1973): 128–35.

Patricia E. Kane, 300 Years of American Seating Furniture: Chairs and Beds from the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (Boston, Mass.: New York Graphic Society, 1976), p. 106, no. 90; Antiques 43, no. 1 (January 1943): inside front cover.

Kirk, American Chairs, p. 172. He identified only three of the five chairs as those included in his book (nos. 80–82). Kane published a likely fourth, namely no. 92, in 300 Years. The fifth chair is not identified. Objective and subjective observations parallel “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” evidence discussed in Zimmerman, “A Methodological Study,” pp. 194–95.

Philip D. Zimmerman, “Workmanship as Evidence: A Model for Object Study,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 4 (winter 1981): 300 n. 43, figs. 19–20.

For English and other regional expressions of this chair back design, see John T. Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), figs. 948–58; and Brock Jobe, Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast (Boston, Mass.: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1993), nos. 82–83, pp. 310–12. For the Affleck-attributed chairs, Kirk cites Hornor, Blue Book, pls. 260 and 265. Kirk, American Chairs, pp. 14 nos. 6, 166.