Joined chair attributed to John Elderkin, eastern Connecticut, Rhode Island, or Massachusetts, 1640–1680. Oak, cherry, and ash. H. 42 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 19 1/4" (seat). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

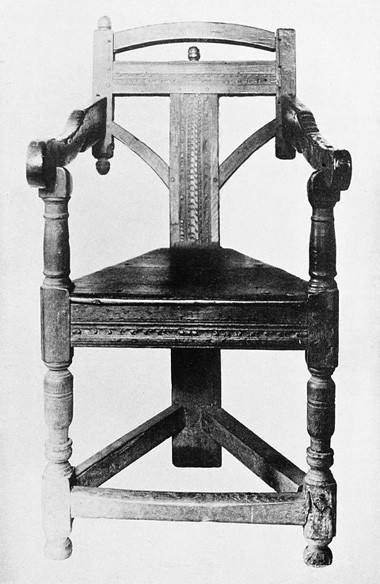

Joined chair illustrated in fig. 1, as it appeared in Wallace Nutting’s Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 2 vols. (1921, reprint ed.; Framingham, Mass.: Old America Company, 1928), 2: no. 1774.

Turned chair, England, 1550–1600. Ash. H. 44 7/8", W. 30 3/8", D. 22 3/8". (Formerly the collection of the late John Hill. Present whereabouts unknown; photo, George Fistrovitch.)

Detail of the underside of the turned chair illustrated in fig. 3. (Formerly the collection of the late John Hill. Present whereabouts unknown; photo, George Fistrovitch.)

Turned chair, England, 1550–1650. Beech and elm. H. 34", W. 24", D. 19". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Turned chair, probably Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1630–1655. Red and black ash. H. 45", W. 24 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Plymouth, Massachusetts, gift of the heirs of William Hedge; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The white pine seat board is a later replacement.

Turned chair, Connecticut, 1650–1700. Ash and oak. H. 41 1/8", W. 23", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society; photo, Robert Bitondi.)

Side view of the turned chair illustrated in fig. 7.

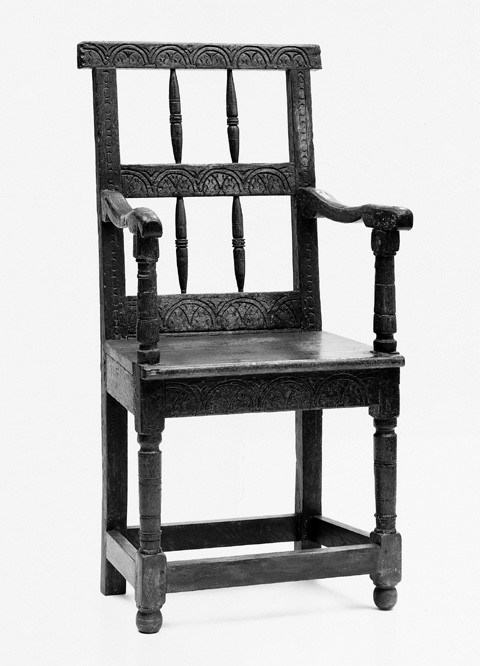

Plain chair, England, seventeenth century. Oak. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Plain chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1650–1720. White oak and maple. H. 37", W. 20 3/4", D. 16 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Hezekiah E. Bolles Fund.) This example came from Rochester in Plymouth County. It has a replaced bast seat. Most plain matted chairs probably had rush seats.

Side view of the joined chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the joined chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Court cupboard, Newbury, Massachusetts, 1680. Oak, sycamore, maple, and walnut with tulip poplar. H. 57 3/4", W. 50", D. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Joined chair, eastern Massachusetts, 1660–1680. Oak. H. 44 1/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Aimée and Rosamond Lamb.)

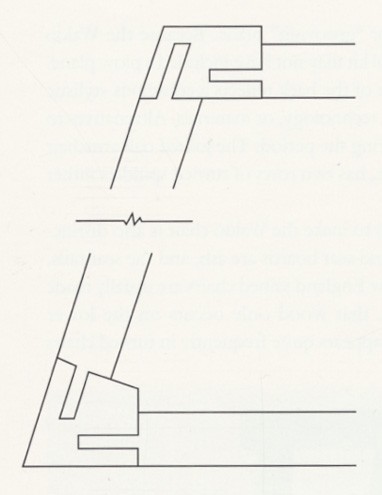

Diagram showing the seat and stretcher construction of a conventional New England wainscot chair.

Diagram showing the seat and stretcher construction of the joined chair illustrated in fig. 1.

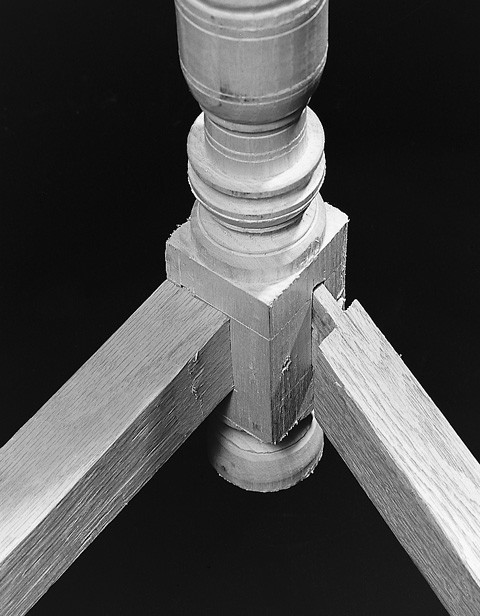

Detail of a reproduction of the joined chair illustrated in fig. 1, showing the joint angles and pins of the stretchers. (Reproduction by Peter Follansbee; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

A three-post, or “three-square,” joined chair traditionally referred to as the Waldo chair, is the only known example of this intriguing furniture form (fig. 1). In concept, this object incorporates several recognized chairmaking designs. Like many contemporary wainscot chairs, it has a front frame with two posts connected by a seat rail and a stretcher. Decorative details include turnings on the front posts and gouge-cut carving in the crease moldings on the seat rails and back. The back is unique in the history of seventeenth-century furniture design. It consists of a single, broad post that supports an open framework of rails and stiles with diagonal, curved braces. The scroll-shaped arms tenoned into the rear stiles are elongated versions of those found on wainscot chairs.[1]

Although Wallace Nutting recorded a partial history of the Waldo chair in Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1921), he stated that it was “reputed to have been brought from France, but claimed to be made of American woods” (fig. 2). In 1983, furniture historian Robert F. Trent presented new research on the history of the chair and suggested that it was made by a New England carpenter. Among several possible candidates for the maker, Trent favored John Elderkin (1616–1687), an immigrant millwright who worked in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. This article will discuss the stylistic origins of the chair, examine aspects of its construction, and assess the Elderkin attribution in greater detail.[2]

Trent’s assertion that the Waldo chair was made by an artisan trained in carpentry rather than furniture joinery is logical. Some aspects of its construction suggest that the maker was unfamiliar with traditional chairmaking procedures, whereas others relate to the framing of large seventeenth-century buildings. The distinctive construction of the rear facade reflects an understanding of complex structural forces that a joiner would rarely, if ever, encounter.

The Waldo chair has much in common with three-post, board-seated turned chairs, which survive in relatively large numbers and frequently appear in Dutch genre paintings of the period (fig. 3). The latter chairs are made almost entirely of turned members, but their seat construction is what distinguishes them from other forms. The seat is a riven (split) board captured in grooves in the adjacent lists (fig. 4). Because the seat lists enter the posts at the same height (to receive the feathered edges of the seat board), their tenons intersect each other. Turners often solved this problem by using a combination of rectangular tenons pierced by turned ones. Alternatively, some tradesmen combined large and small round tenons.[3]

In Academie or Store House of Armory & Blazon (1688), Randle Holme illustrated two seating forms with board seats—a chair with a canted back and a triangular stool. His descriptions are at times misleading and vague. The chair has no arms, but he refers to it as “a Turned chaire with Armes” and notes that “these kind . . . are [also] borne without Armes”(depicted on coats of arms as a side chair). His description of the stool is more revealing:

a Turned stoole . . . so termed because it is made by the Turner, or wheele wright all of Turned wood, wrought with Knops, and rings all over the feete, these and the chaires, are generally made with three feete, but to distinguish them from the foure feet, you may term them three footed turned stool or chair.[4]

Although over thirteen New England chairs with four feet and board seats survive, no three-footed examples are known. Two three-footed chairs have early New England histories, but both were made in England. The only New England probate reference that might designate this form is the “3 Square chaire” valued at 4s. in the 1672 inventory of Richard Jacob of Ipswich, Massachusetts. Because appraisers commonly identified chairs by their seat material, some of the numerous references to “wooden chairs” in seventeenth-century New England inventories could refer to three-footed examples with board seats.[5]

Board-seated turned chairs are made in two basic formats. In three-footed examples, the simplest version has a T-shaped back. A crest rail—either a slightly curved board or a turned rail—is mounted across the top of an extended rear post and is supported by diagonal braces. This type of chair has no layback, so the back post is perpendicular to the seat plane. When arms are employed they are turned and tenoned into the front posts and the crest rail (fig. 5). The second type of three-footed chair has a rear facade formed by a rectangular or square frame composed of turned members mounted on top of a shortened rear post, strengthened by diagonal bracing (see fig. 3). This structure is more substantial and provides some layback for comfort.

The same basic designs also occur in four-legged chairs. Although usually quite ornamental, the straight-backed version is similar in concept to rush-seated chairs. On the Plymouth example shown in figure 6, the rear posts extend from the floor to the top of the chair’s back. A more complex chair of Connecticut origin (figs. 7, 8) has a rear frame with a strong cant. The shortened back legs are tenoned up into a horizontal cross rail just above the seat, and the upper rear posts are tenoned down into the rail at an angle.

No direct antecedent for the Waldo chair is known, but two simple, shaved and planed English three-legged chairs survive. One (formerly in the Rous Lench collection) is illustrated in Victor Chinnery’s Oak Furniture: The British Tradition; the other is illustrated in figure 9. Although both objects are made of riven and hewn timber and have rectangular mortise-and-tenon joints at the front seat rail and rear crest rails, they are not “joined chairs” in the strictest sense of the term. The basic design and structure of these chairs relate more closely to turned examples. They have arms that tenon into the crest rail and diagonal braces that fit between the rear post and the crest rail. All the joinery used for the side seat rails, arms, and stretchers consists of round, shaved tenons seated in mortises bored with a brace and bit. Instead of being captured in grooves, the seat boards sit on top of the seat rails and are fastened with nails. The rear post is hewn above the seat to produce a slight layback.[6]

In design and construction, these English chairs are non-turned versions of the turned three-footed chair. The period term for these shaved and planed forms is “plain” chair. Records from the London Turner’s Company concerning the production of “matted” or rush-seated chairs reveal that turners made non-turned seating furniture. On February 20, 1615,

it was directed that the makers of chairs about the City, who were strangers and foreigners, were to bring them to the Hall to be searched according to the ordinances. When they were thus brought and searched, they were to be bought by the Master and Wardens at a price fixed by them, which was 6s per dozen for plain matted chairs and 7s per dozen for turned matted chairs.

This distinction between “plain” and “turned” chairs proves that turners made shaved examples at less cost. Documentary evidence suggests that the plain chair was the most common seating form of the period, yet very few examples survive. Their construction was the most straightforward: The parts were shaved with a drawknife, then assembled by fitting round shaved tenons into bored mortises (fig. 10). The existence of plain chairs reinforces the idea that turned components were strictly ornamental in intention. Stock for a turned chair was prepared by riving and shaving the pieces prior to shaping them on the lathe. The makers of plain matted chairs simply omitted the turning stage.[7]

Although the Waldo chair’s design incorporates some elements from three-footed, board-seated turned chairs, it is technically a joined chair. With the exception of the finials and pendants, it is constructed entirely with drawbored, mortise-and-tenon joints. The maker prepared his stock by riving and hewing the “stuff” from the log, then dressing it with a joiner’s hatchet and planes. He selected a naturally curved, or “swept,” piece of timber for the back post before hewing and planing it to refine the shape (fig. 11). This method of producing layback differs from traditional wainscot chair construction. Most joiners simply hewed and planed straight boards.[8]

The rear post of the Waldo chair is tenoned into a back frame composed of two horizontal rails, two short vertical stiles, and two diagonal braces (fig. 12). Unlike the braces in turned and plain shaved chairs, which usually fit between the post and the crest rail, those on the Waldo chair connect the rear post to short stiles. Another important distinction between this chair and turned examples is that the arms of the Waldo chair tenon into the rear stiles, not into the crest rail. This is a joiner’s practice rather than a turner’s. All triangular turned chairs have arms that are tenoned into crest rails.

Although the Waldo chair relates to traditional wainscot examples in certain respects, the design and construction of its back is purely architectural. The truncated rear stiles, which essentially hang from the rear rails, are similar to “jetties” or overhangs in framed house construction. Other parallels with seventeenth-century buildings are evident in the curved boards used for the upper rail and diagonal braces and the simplified lamb’s tongues on the lower ends of the rear stiles. The turned finials and pendants tenoned into the rear stiles and top rail are also similar to those on jetties. Although most architectural pendants are carved from the solid, a pair from Lyme, Connecticut, are turned and tenoned into place.[9]

Only four other pieces of New England furniture have framed jetties with pendants. All are joined cupboards tentatively attributed to Newbury, Massachusetts (fig. 13). On these examples, the middle rails extend beyond the lower stiles on the sides. The oversailing rails tenon into shortened hanging stiles with turned pendants. Many English and New England cupboards have cantilevered upper sections, but they are usually supported by turned pillars. Some English and Welsh examples also have unsupported jetties with turned pendants; however, none have diagonal braces like those on the Waldo chair.[10]

The complexity of the rear framing of the chair clinches the argument that the maker trained as a carpenter. As previously discussed, turned versions of these chairs have braces that join the crest rail to the rear post—a straightforward concept that triangulates the rear structure. On the Waldo chair, the diagonal braces are tenoned from the rear post into the hanging stiles. The compression forces exerted in this arrangement are more complex than those in turned chairs. The two rear rails of the back are structurally necessary. If there were only one rail, the braces would push the bottoms of the stiles apart, levering against the shoulders of the crest rail’s tenons. The purpose of the upper curved rail is to resist the spreading force, effectively uniting the entire rear frame. This design involved more structural considerations than a joiner typically confronted. Because the stresses present in joined furniture are usually slight, diagonal braces are not required to stabilize the framing.[11]

Other structural and stylistic features differentiate the Waldo chair from conventional joiner’s work. Most wainscot chairs have back panels fitted into grooves made with a plow or “grooving” plane. Because the Waldo chair has no panels, the maker’s tool kit may not have included a plow plane. Nevertheless, the open framework of the back reflects a conscious stylistic decision rather than a lack of tools, technology, or materials. Alternatives to paneled backs certainly existed during the period. The joined oak armchair illustrated in figure 14, for example, has two rows of turned spindles rather than panels.

The combination of woods used to make the Waldo chair is also distinctive. The posts, rear rails, braces, and seat boards are ash, and the seat rails, rear stiles, and arms are cherry. New England joined chairs are usually made almost entirely of oak; however, that wood only occurs on the lower stretchers of the Waldo chair. Ash appears quite frequently in turned chairs of the period, but it is only occasionally found in New England joined work. Ash is a strong, ring-porous hardwood that is easy to rive when it is straight-grained and clear of knots. It also planes and carves very well. Ash lacks the decay resistance of white oak, but for furniture (as opposed to architecture) this is not particularly critical. The cherry components of the Waldo chair represent the only occurrence of fruitwood in seventeenth-century New England furniture. Cherry rives easily in the growth ring plane, but its interwoven fibers make it very difficult to split on the radial plane. The maker of the Waldo chair clearly understood these limitations and rived his stock oversized. The finished thickness of his cherry parts averages about 1 1/2 inches, a good deal heavier than the 1-inch stock used for contemporary joined furniture.[12]

Regardless of their choice of wood, early joiners invariably worked quartered timber (the radial plane of the stock is the face of the board). The vast majority of New England joined furniture features oak riven in this orientation. There are several reasons for using quartered stock. Dimensional stability is the foremost, but ease of working is also a consideration.[13]

Like its materials, the layout and construction of the seat and stretcher system of the Waldo chair are unique in seventeenth-century New England furniture. On most wainscot chairs, the side face of the front stiles was planed to match the angle of the intersecting side rails and stretchers. This method simplified the joinery because the mortises for the side rails and stretchers could be chopped parallel to the side faces of the stiles. Because the rear face of the front stiles was planed at ninety degrees to the side face, the seat rails and stretchers have tenons with ninety-degree shoulders (fig. 15). By contrast, the front stiles of the Waldo chair are square in section. The seat rails and stretchers met the stiles at an obtuse angle, so the maker cut the shoulders of the rail and stretcher tenons to match the angle at which they joined the stile. By cutting the tenons in line with the rails and stretchers, the maker maintained the strength of the timber (fig. 16).[14]

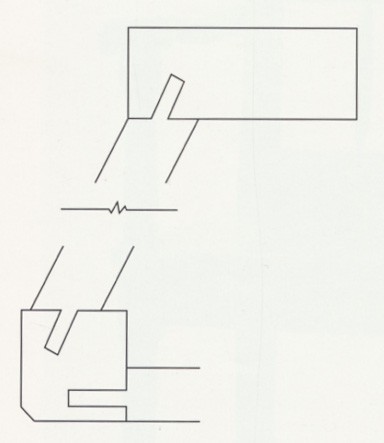

In seventeenth-century woodworking traditions, the pins (pegs) used to secure mortise-and-tenon joints exerted a great deal of force upon the tenon. This practice was necessary to draw the joint together. The tenon had to be long enough to prevent the pin (or pins) from splitting the wood beyond the pin hole, and the corresponding mortise had to be deep enough to accommodate the tenon. Ordinarily the outer face of a mortised stile and a tenoned rail are flush. Although this is the case on the front and rear facade of the Waldo chair, the side joints deviate from the norm (fig. 16). Because of the sharply tapered seat plan, straight tenons of the side rails and stretchers, and square-sectioned front stiles, the mortises for the side rails had to be positioned further inward from the side face of the front stiles than was usual. This position minimized the chance of the mortise breaking the side of the stile while maintaining enough depth for the tenon. The pegs securing these joints are perpendicular to the tenon; they enter the same face of the stile as the mortise (fig. 17). Where the side rails meet the rear post the joinery is conventional, and the tenon shoulders are flush with the arris of the post.[15]

Although cutting the front mortises for the side rails and stretchers at an angle was necessary to create the tapering seat plan, the maker would have found it difficult to chop across the fibers of the front stiles. Pre-boring the bulk of the waste would have simplified the process and allowed him to maintain an accurate angle with his chisels. This is not a joiner’s technique, for they chopped their joints exclusively with a mortise chisel. By contrast, carpenters routinely pre-bored large mortises.[16]

Although the training, tool kits, and working methods of carpenters and furniture joiners differed, the historical record suggests that woodworkers in provincial England and New England did whatever work came to hand. Scholarly discussions regarding the separation of these trades often cite the records of the London Court of Aldermen (1632), which include a lengthy court decision that demarcated the two professions and described their respective products. It is important to note, however, that this decision only applied to London and its environs.[17]

Many period documents mention carpenters making furniture. In 1653, Francis Perry of Salem and Lynn, Massachusetts, reported “that being carpenter of the [Saugus Iron] works he made many things for Gifford’s house on the Company’s account, including one great press, and set up two dressers.” Perry’s reference to a “great press” belies the notion that carpenters only made simple furniture forms such as six-board chests. The Waldo chair is another excellent case in point. Although some aspects of its framing are relatively simple, others are considerably more complicated than those of conventional wainscot chairs.[18]

Like other seventeenth-century woodworkers, carpenters frequently interacted with artisans outside their trade. The elongated scrolled arms of the Waldo chair suggest that the maker was either familiar with contemporary chairmaking practices or had access to a joiner’s patterns. Regardless of this chair’s design sources, the successful integration of features found on wainscot chairs, three-post, board-seated turned chairs, “plain chairs,” and buildings attests to the maker’s ingenuity and ability to solve complex framing problems.

The history of the chair provides clues to this artisan’s identity. Nutting noted that Nathan Waldo (1740–1834) owned the chair, but he was unaware that two of Waldo’s ancestors—John (1655–1700) and Daniel (1657–1737)—were woodworkers. Their father, Cornelius Waldo (1624–1700/1), emigrated from England by 1647. John married Rebecca Adams, and Daniel married her sister Susanna, whose father, Samuel (1617–1688), worked as a millwright in Braintree, Charlestown, and Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Presumably both brothers trained with their father-in-law. In 1695, Daniel received land in Chelmsford as payment for setting up and maintaining “a good and sufficient corn-mill.” John owned carpenter’s and cooper’s tools, but his inventory does not specify his trade.[19]

Since John Waldo was Nathan’s great-grandfather, it is conceivable that the chair descended through the male line; however, under New England partible inheritance laws, males typically inherited real estate, whereas females inherited “moveables,” including household furniture. It is much more likely that Nathan inherited the chair from his mother, Abigail Elderkin Waldo (b. 1715), great-granddaughter of John Elderkin.

Elderkin arrived in New England about 1637. His daughter, Abigail, was born in Dedham, Massachusetts, on September 13, 1641. Elderkin and his family moved frequently. They resided in Lynn, Massachusetts, during the mid-1640s, in New London, Connecticut, during the 1650s, and in Norwich during the early 1660s. Elderkin’s career included contracts for meetinghouses, mills, and wharves. The earliest record concerning his work is an October 17, 1650, receipt for building a mill for the town of New London. Carpenters and millwrights often had to travel significant distances to ply their trade. Elderkin also worked in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1650.[20]

One of Elderkin’s most important commissions involved work on the first meetinghouse in New London. On August 29, 1651, the town records noted that, “Goodman Elderkin doth undertake to build a meeting-house about the same demention of Mr Parke’s . . . barne and clapboard it for the sum of eight pounds, provided the town cary the tymber to the place and find nayles. And for his pay he requires a cow and 50s. in peage.” At the time, the community was holding services in Robert Parke’s barn. Elderkin’s proposal was rejected, and a site for the meetinghouse was not selected until December 1652, when he, joiner Samuel Lothrop, and Samuel Smith were contracted

to buield a substantiall house Thirty foot square the wall to be Twelve foot betweene Joyntes the wall to be broake, to have sixe windowes convenient for the house fited for glasse with two doers eich of them to be double doers to lay one floore upon the grownd of joyce and plancke to Cover the walles with good seasoned board to be rebetted one over another to make in the roofe fowre gables with a turret in the roofe floored in the bottome to Cover the roofe with sawne board close Laide and to shingle the roofe upon the boarde with short shingles not above twenty Inches to finde all stuffe Cart all timber find all nailes and to finish this worke at or before the last of October (1653).[21]

Elderkin’s services were apparently in great demand during the summer of 1651. On August 31, William Wells of Southold, Long Island, requested John Winthrop, Jr.’s, assistance in “grantinge and perswadeing your Millwright John Elderkin to come a long . . . to view the ruins of our old water mill; and build us a new.” Shortly thereafter, Thomas Mayhew, a patentee of Martha’s Vineyard, wrote Winthrop, “wee have greate want of a mill and there is one with you that I here is a verry Ingenuous man about such work that is goodman Elderkin, but wee here you have some Ingadement uppon him. Now these are to intreate you if possible you can disspense a while with him.” Evidently, Elderkin accepted the Southold offer. In March 1652, “John Elderkin of Pequot [New London]” contracted with John Winthrop, Jr., for “one whole yeere beginning the first of April next to worke with him in any Carpentry worke that I can doe and to bueild him a Saw mill and keepe the Corn mill . . . And what time I shall be absent at South hold or upon my own occasions I shall make good.”[22]

In 1659/60, the town of Moheagan (Norwich) hired Elderkin “to erect a corn-mill . . . to be completed before November 1, 1661.” As part of this agreement, the mill received forty acres from the town, the land to be improved by “John Elderkin, the Miller.” Thirteen years later, the town commissioned Elderkin to build a new meetinghouse. During the course of his work, he requested an increase in pay:

Your humble petitioner pleadeth your charitie for the reasons hereafter expressed . . . it is very well known that I have been undertaker for building of the meeting hous and it being a work very difficult to understand the whole worth and value off, yet notwithstanding I have presumed to do the work for a sertain sum of money . . . 428 pound, not having any designe thereby to make myself rich, but that the town might have their meeting house dun for a reasonable consideration. But upon my experieince, I doe find by my bill of cost, I have done the said work very much to my damage, as I shall now make appear. Gentlemen I shall not say much unto you, but onley if you may be sensible of my loss in said undertaking, I pray for your generous and charitable conclusion toward me whether it be much or little, I hope will be well excepted from your poor and humble petitioner. John Elderkin.[23]

In 1677/8, the town of New London hired him to build yet another meetinghouse. The original building contract no longer survives but was summarized in Frances Manwaring Caulkins’s The History of New London, Connecticut (1895):

The contract for building the meeting-house was made with John Elderkin and Samuel Lothrop. It was to be forty feet square, the studs twenty feet high with a turret answerable, two galleries, fourteen windows, three doors, and to set up on all the four gables of the house, pyramids comely and fit for the work, and as many lights in each window as direction should be given: a year and a half given for its completion: £240 to be paid in provision; viz, in wheat, pease, pork and beef, in quantity proportional: the town to find nails, glass, iron-work, and ropes for the rearing. Also to boat and cart the timber to the place and provide sufficient help to rear the work.[24]

The complexity of Elderkin’s architectural commissions suggests that he would have been capable of constructing the Waldo chair. An October 20, 1654, letter from John Pyncheon, Jr., to John Winthrop, Jr. (who was in Saybrook, Connecticut, at the time), alludes to Elderkin’s involvement with interior finish carpentry and joinery: “Sir, I am bold to request that the room in which my wife will be in this winter may speedily be made warm. I pray let Goodman Elderkin be called on to do it out of hand in regard my wife is but tender and cold will set in quickly.” Presumably, the room was to be made warm by “ceiling” it—enclosing it with frame-and-panel wainscot.[25]

Elderkin’s work may also have included shipbuilding. Tradition credits him with the construction of the “New London Tryall” in 1661, the first merchant vessel built in New London. The ability to frame complex structures such as ships, mills, and meetinghouses is the essential concept differentiating the maker of the Waldo chair from joiners who produced wainscot examples. Not only was Elderkin an artisan of consummate skill, but his English background may explain the variety of turned and joined chair styles that appear to have influenced the design of the Waldo chair. These facts, coupled with his familial relationship to Nathan Waldo, strongly suggest that Elderkin made this remarkable chair.[26]

For the history and a proposed attribution of the Waldo chair, see Robert F. Trent, “The Waldo Chair: A Monument of Early Connecticut Joinery,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 48, no. 4 (fall 1983): 174–88. The author thanks Trent for his assistance in preparing this article and for providing photographs of various chairs.

Most of the information on board-seated turned chairs presented here is based on unpublished research by Robert F. Trent, John Alexander, and Allan Breed. For a preliminary report on that work, see Trent, “The Board-Seated Turned Chairs Project,” Regional Furniture 4 (1990): 43–48. Other studies of turned chairs include S. Dillon Ripley, “An American Triangular Turned Chair?” in Pilgrim Century Furniture, edited by Robert F. Trent (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1976), pp. 31–33; Richard Ryder, “Three-Legged Turned Chairs,” Connoisseur 191, no. 766 (December 1975): 243–47; Richard Ryder, “Four-Legged Turned Chairs,” Connoisseur 191, no. 767 (January 1976): 44–49; Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collector’s Club, 1979), pp. 87–101; and Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture 1630–1730 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1988), pp. 68–77.

As quoted in Chinnery, Oak Furniture, pp. 545–49. Also, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 383–84.

For references to overhanging jetties see Appendix 2 in Abbott Lowell Cummings, “Massachusetts and Its First Period Houses,” in Architecture in Colonial Massachusetts, edited by Abbott Lowell Cummings (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1979), pp. 193–221. Abbott Lowell Cummings, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625–1725 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979), pp. 126, 137–38, illustrates two pendants thought to be from Newbury, Massachusetts. Norman M. Isham and Albert F. Brown, Early Connecticut Houses: An Historical and Architectural Study (Mineola, N.Y.: Isham and Brown, 1965), pp. 231–36, illustrate two pendants that were not applied. For two turned examples, see Christie’s, The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Eddy Nicholson, New York, January 27–28, 1995, p. 222, lot 1041.