Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and ash. H. 41 5/8", W. 23 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Russell family of Plymouth, but it reputedly belonged to the Winslow family of Marshfield. It appears to have been painted red originally.

Turned great chair, Netherlands, 1640–1660. Ash. H. 37 3/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, John Sinkler.)

Detail of the finial of the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of the vase-ball-vase turning on the rear post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

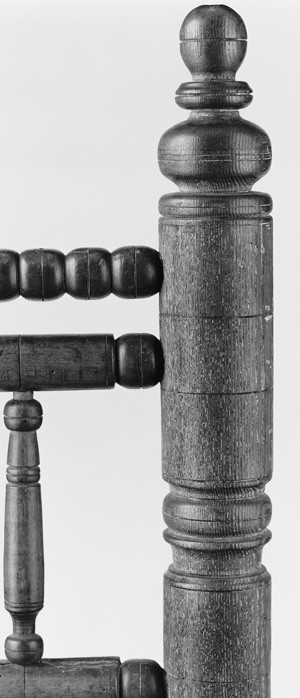

Detail of the column-ball-column turning on the rear post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of a pommel on the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of the ball-with-coves turning on the front post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

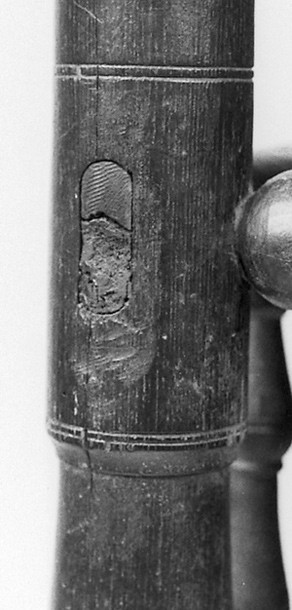

Detail of the front seat joint of the great chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Turned great chair, Boston, 1640–1670. Maple and ash. H. 45 1/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting collection, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan.)

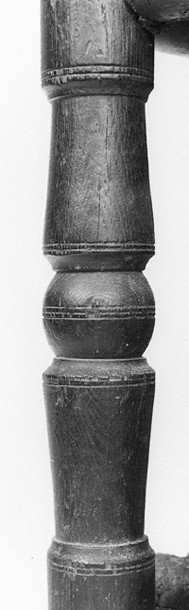

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1660–1685. Maple and ash. H. 45 1/2", W. 24 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair.)

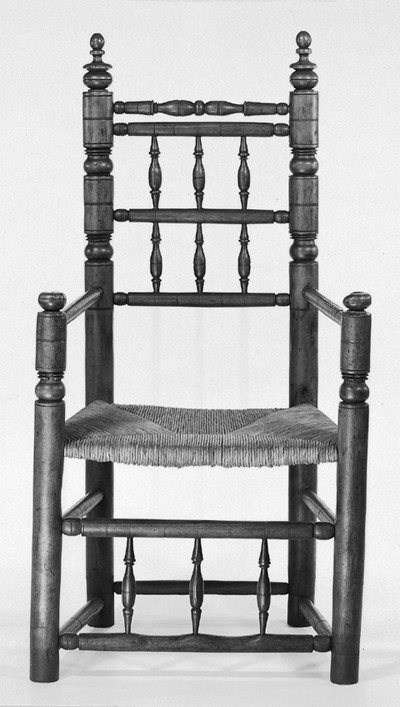

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1660–1685. Maple and ash. H. 44", W. 23 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Bartlett family of Plymouth.

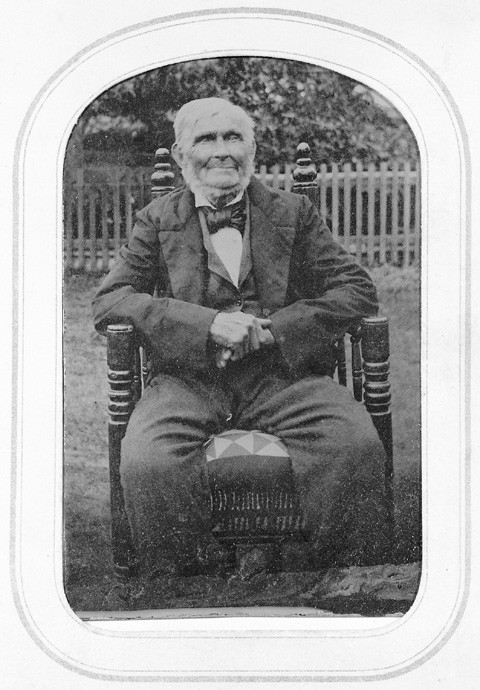

Photograph of Isaac Bartlett, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1860–1880. Tintype. 3 5/8" x 2 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The subject is seated in the great chair illustrated in fig. 11.

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and ash. H. 42 7/8", W. 25 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting collection, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan.)

Detail of a vasiform spindle on the great chair illustrated in fig. 1

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and ash. H. 46 3/4", W. 25 1/4", D. 17 1/4". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts, gift of Joseph Head; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has long been known as the Governor John Carver chair. It appears to have been painted black originally.

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and ash. H. 43 1/2", W. 24", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection; gift of Miss Ima Hogg.) This chair reputedly descended in the Ellis family of Carver, Massachusetts.

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1695–1715. Maple and ash. H. 42 1/2", W. 25 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall Museum, gift of Joseph Everett Chandler; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair reputedly descended in the Churchill family of Plymouth.

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1705–1720. Maple and ash. H. 41 7/8", W. 24", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair reputedly descended in the Fairbanks family of Dedham and Wrentham, Massachusetts.

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. H. 45 3/4", W. 24", D. 17 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. H. 41 3/8", W. 23 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Slat-back great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. H. 45 7/8", W. 25 1/4", D. 21". (Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting Collection, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan.)

Slat-back great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. H. 42 1/8", W. 25 1/8", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Turned great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1715–1730. Maple and ash. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, First Congregational Church of Windham Center, Connecticut, on loan to the Windham Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has long been known as the Governor William Bradford chair.

Detail of a misbored mortise hole in the right rear post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a misbored mortise hole in the right rear post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a misbored mortise hole in the right rear post of the great chair illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

In 1978 Robert Blair St. George published an article in which he attributed a group of early turned chairs to Ephraim Tinkham II (1649–1713) of Plymouth and Middleborough in Plymouth County, Massachusetts. Not content merely to cite the relevant objects and documentation, St. George proposed a reevaluation of what might half-seriously be termed the “Wallace Nutting rules” of early American turned chair aesthetics:

1. Seventeenth-century chairs with posts of greater diameter are earlier and more valuable.

2. Seventeenth-century chairs with decorative spindles below the seat (“Brewster” chairs) are distinguished from those with spindles above the seat only (“Carver” chairs), and most Brewster chairs are more valuable than most Carver chairs.

3. Brewster and Carver chairs are earlier and more valuable than almost all seventeenth-century slat-back chairs with posts of comparable diameter.

In other words, Nutting thought of these variations as discrete “types” in a fixed temporal sequence; Brewsters preceded Carvers, and both preceded slat-back chairs. Why he valued earlier chairs more highly than later ones is unclear. Perhaps Nutting thought earlier ones were dignified by association with the founders of Plymouth Colony, like William Brewster, William Bradford, John Carver, Myles Standish, and John Churchill. All these patriarchs reputedly owned armchairs now located at Pilgrim Hall in Plymouth. The popular terms “Brewster” and “Carver” used by Nutting derive from two of the Pilgrim Hall examples, although it is not apparent when these antiquarian terms entered popular usage.[1]

St. George rightly pointed out that the Tinkham shop tradition included variants that did not conform to Nutting’s notions. Chairs with essentially the same ground plan and post format could feature two tiers of spindles in the back, one tier under the arms, and one tier under the seat; only one tier of spindles in the back; or slats in the back and spindles under the arms and below the seat. The latter variant is the most unusual in this shop tradition. Nutting owned and published a slat-back example, which he termed a “semi-Brewster,” but offered no explanation of how it fitted into his stylistic and dating system. St. George suggested that all these variants were available simultaneously and that Tinkham may have used prefabricated posts to assemble chairs in whatever format the customer desired. St. George also asserted that Tinkham employed the same pattern for all his posts.[2]

Over the last twenty years, several related chairs have emerged from Plymouth County families, including one example that St. George knew only from an old photograph (fig. 1). These chairs have expanded the repertoire of design and ornament as well as the probable date range of the Tinkham shop tradition. The recent discovery of Netherlandish and New England antecedents has also helped place these chairs in a broader cultural and stylistic context.

It now appears that the Tinkham shop tradition began well before Ephraim’s apprenticeship, which probably commenced about 1662 or 1663. Although his master has not been identified, it seems fairly certain this anonymous tradesman introduced chairmaking styles and practices that persisted well into the eighteenth century. Ephraim Tinkham thus represents the “second generation” of this artisanal tradition. The myriad stylistic sources manifest in these chairs suggest that the tradition may have experienced temporary “aberrations” due to outside influences at several junctures. In short, the extraordinary variety encompassed by the tradition is the cumulative achievement of four or five shops over perhaps seventy years rather than the collective experience of one individual. We will, nevertheless, continue to use the generic term “Tinkham” to describe this chairmaking school and its products.

This article departs from St. George’s model in several regards. Although other chairmaking traditions probably produced slat-back examples as early as 1640, all of the Tinkham ones date after 1700. The fully turned chairs influenced by Boston examples appear to be the earliest ones in the Tinkham group. It is unclear whether Tinkham chairs with two tiers of spindles in the back predate those with one tier, but careful comparison of all traits suggests that one-tier backs are either later or are not represented by earlier surviving examples. Establishing a stylistic chronology for Tinkham chairs is further complicated by the fact that some makers were regressive in their application of certain ornamental details, such as finial turnings.

Although scholars have identified the European design sources for many seventeenth-century American case pieces, they have done little to verify the antecedents of contemporary turned chairs. This is understandable given the paucity of turned chairs in European museums and the almost total lack of documented examples in England and the Netherlands. Fortunately, Dutch chairs can be analyzed by examining genre paintings. The lack of documented Continental turned chairs is unfortunate, because the historical record suggests that Dutch turned chairs were popular throughout Europe and were exported widely from the late Middle Ages until the eighteenth century. The Dutch undoubtedly established the basic three-post and four-post formulae for turned chairs and successfully competed with new styles emanating from Paris after 1670 by developing rush-seated, high-backed versions of upholstered prototypes. In many instances, it is extremely difficult to tell whether a seventeenth-century turned chair with an English history was made there or in the Netherlands. In most instances, the more stylish or well made the object, the more likely it is to be Dutch.[3]

The Dutch chair illustrated in figure 2 has no provenance, but it provides exact parallels for most of the details found on Tinkham chairs. Since Tinkham’s master probably arrived in New England during the 1620s or 1630s, the Dutch chair cannot be regarded as an antecedent; nevertheless, it is likely that Tinkham’s master and the maker of the Dutch chair were separated by only three or four apprenticeships from an ancestral shop in a major Netherlandish urban center. The large number of Dutch and Rhenish artisans that migrated to English ports between 1560 and 1640 render this idea rather more plausible than not.[4]

The proportions of the Dutch chair are strikingly similar to those of fully developed, second-generation Tinkham chairs, such as the Winslow example (see fig. 1). As St. George noted, many (but not all) Tinkham chairs are relatively narrow at the rear and wide at the front—in other words, they have a strong trapezoidal splay. The Dutch chair exhibits a peculiar approach wherein the front posts are vertical but the rear posts have a distinct backward rake, presumably for comfort. Many of the Tinkham chairs have layback, but all four of their posts are tilted to the rear (see fig. 1). These chairs sometimes have raked arms like those of the Dutch example, although none display the same labor-intensive series of five diminishing spindles under the arm.

Setting aside gross characteristics of the frame, the Dutch chair’s turned ornaments provide exact parallels for the following “Tinkham” ones: the ball-reel-ball finial (fig. 3); the bilaterally symmetrical vase-ball-vase and the column-ball-column spindles (figs. 4, 5, respectively); the ovoid pommels or grips (fig. 6); the ball turning flanked by filleted coves on the posts (fig. 7); and minor groupings of fine, scored accents. One feature of the Dutch chair that is absent in the Tinkham group is the board seat held in plowed seat rails. The side rails on the Dutch chair have round tenons that intersect the rectangular tenons of the front rail (fig. 8). This structure also occurs on a small number of Plymouth County turned chairs, notably the Bradford-Brewster-Standish group at Pilgrim Hall and the Reverend James Keith chair at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Given the striking similarities between the Tinkham chairs and the Dutch example, it is possible that turners in the Tinkham tradition made board-seated chairs that simply have not survived.[5]

All of the Tinkham features that deviate from the Dutch model are either innovations influenced by other design sources or the result of simplification. In some instances, turners in the Tinkham tradition abandoned these departures and returned to earlier designs. A Boston great chair (fig. 9) and two Tinkham examples (figs. 10, 11) illustrate these points. The finials of the Boston chair are quite similar to the applied colonettes on Boston case pieces attributed to London-trained joiners Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger and London-trained turner Thomas Edsall. Several other chairs with London-inspired details and eastern Massachusetts histories survive. Not only do they reinforce the Boston attribution of the aforementioned example, but they help distinguish that city’s chairs from those produced in Salem, Plymouth (exemplified by the Bradford-Brewster-Standish and Tinkham groups), and other towns and communities in the region.[6]

Unlike most Boston turned chairs, the one illustrated in figure 9 has two tiers of spindles in the back and one tier between the second and bottom front stretchers. It is easy to infer that a chair of this type inspired the progenitor of the Tinkham tradition to modify the traditional Anglo-Dutch back plan (see fig. 2), perhaps as early as 1650–1660. A turned great chair at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 10) and a related example that descended in the Bartlett family (figs. 11, 12) show this Boston influence at its strongest. Not only do they have the same distribution of spindles as the Boston chair, but their posts display the same heavy urns with flanges seen on the posts of the urban prototype (fig. 9). The finials of these Tinkham chairs also incorporate a second flange element that is an abbreviated version of the one on the finials of the Boston chair. Were it not for the finial turnings of the Tinkham chair shown in figure 10, one might attribute it to Boston on the basis of its urn spindles. On the Bartlett chair, the maker pulled back from such thorough-going Boston influence. He modified the urn turnings on the posts and finials but retained two variants of his standard spindle turning—the vasiform kind and the columnar kind.[7]

The Bartlett chair and the example shown in figure 13 are the only Tinkham chairs that incorporate both kinds of spindle. The Bartlett chair also suggests that spindles with relatively straight bodies may predate those with more robust vasiform shapes (figs. 14, 15). This observation may seem routine, were it not for the fact that many scholars interpret straight-bodied turnings as “degenerate” versions of earlier ones with pronounced ogee curves.

The chair shown in figure 13 is quite close to the Bartlett chair but reverts to the base tradition in the form of the spindles and the somewhat edited cove-ball-cove turnings on the posts. It is also the earliest example with a ball-reel-ball finial and a giant, stepped-in pillar turning on the front posts—details that became commonplace later in the tradition. Because this finial has strong affinities to those used on many Boston baroque chairs made after 1695, it represents the latest stylistic feature of the Tinkham chair and places it solidly in the 1695–1710 date range. By contrast, the stepped-in pillars on the front posts of the chair may be a conservative detail. Related pillars occur on earlier Plymouth County cupboards and tables, which suggests that Tinkham and his master may have provided ornaments for local joiners. These stepped-in pillar turnings may also represent Boston influence, because the joiners and turners of Plymouth County copied many features of Boston case pieces.[8]

As the Tinkham chairs illustrated in figures 10 and 11 suggest, the design format consisting of two tiers of spindles in the back, one tier under the arms, and one tier between the second and bottom front stretcher may have been derived from a Boston prototype rather than a Dutch one. On the Dutch chair shown in figure 2, the principal spindle tiers are connected to the seat rails and are quite tall relative to the space they occupy. On the other hand, the purported Boston source has no spindles under the arms (see fig. 9). Adding to this confusion about the probable sources for the two-tiered spindle back in the Tinkham tradition is the existence of a one-tiered version, epitomized by the so-called John Carver chair (fig. 16). Like the William Bradford chair, the Carver example was venerated as a Pilgrim relic before the founding of the Pilgrim Society in Plymouth in 1820. Obviously this chair did not belong to John Carver (d. 1621) but is a Tinkham example of about 1690 to 1700. The great pillar motif on the front posts is typical of the group, and the three large spindles in the back are similar to the smaller columnar spindles on earlier Tinkham chairs. Missing are the pommels or hand grips, which usually have diameters that exceed those of the front posts by more than an inch. Dubbed “mushrooms” by collectors of Nutting’s generation, great pommels are most often associated with slat-back armchairs from Norwich, Connecticut. Such grips were wasteful of materials and labor because they were turned from the solid rather than applied. To some extent, however, they visually compensate for the otherwise plain format of chairs without many spindles. A slightly later chair that descended in the Ellis family of Carver, Massachusetts (fig. 17), indicates what the Carver chair’s pommels may have looked like before they were whittled away. Despite its simplified format, the Carver chair has the same finials as the Bartlett chair (figs. 11, 16) and the example shown in figure 10, thus it must date somewhat before 1695.[9]

A group of three chairs fleshes out a progression of the two-tiered design between about 1700 and 1720. One example (fig. 1) descended in the Winslow, Hayward, Russell, and Jackson families of Plymouth and has long been known as the Isaac Winslow chair. Of all the Tinkham chairs, it has the most vigorous ogee spindle turnings. Like the design format of the chairs shown in figures 9 and 11, these spindles may represent another instance of Boston influence. The Winslow chair is quite similar to one with columnar turnings and an oral tradition of descent in the Churchill family of Plymouth (fig. 18). These chairs share many features, but the finials and the slightly softer cove-ball-cove turnings on the posts of the Churchill chair suggest that it is later than the Winslow example. The finials of the Churchill example have lost the extra flange and top button (compare figs. 3 and 18); however, they resemble the finials of the Dutch chair (fig. 2). This elemental reduction may represent the waning of Boston influence and a return to the archetypal finial design. The Churchill chair retains the great pillar turning found on the posts of later examples in the Tinkham tradition. Another two-tiered chair that reputedly descended in the Fairbanks family of Dedham and Wrentham, Massachusetts, may date as late as 1710 (fig. 19). The spindles on the Fairbanks chair are inverted versions of the columnar ones on the Churchill chair, and its finials are simplified by the elimination of the large, lower ball. Microanalysis of pigment samples taken from the Fairbanks chair indicates that the spindles were painted black and that the rest of the object was unpainted. This instance is the first in which the “tan-and-ebony” color scheme associated with seventeenth-century case furniture has been documented on a turned chair.[10]

The latest Tinkham chairs, which date between 1720 and 1730, display a number of odd innovations. Two chairs (figs. 20, 21) have two sawn, strigiform balusters in the back, highly simplified ornaments, and finials capped with baroque buttons. Other late chairs have slats, including Nutting’s “semi-Brewster” (fig. 22) and an ungainly chair with two slats, a turned top rail, and eccentric finials (fig. 23). A number of these chairs (fig. 24) have slanted turned arms that hark back to the Dutch example; however, slanted arms also appear in a number of eighteenth-century New England chairmaking traditions.

The late Tinkham chair shown in figure 24 has long been associated with Governor William Bradford (1588/89–1657) of Plymouth, although his birth and death dates refute that tradition. A nineteenth-century deacon reported that one of Bradford’s granddaughters brought the chair to Windham, Connecticut, from Massachusetts. Research by R. Ridgeway, however, suggests that the chair came from the governor’s great granddaughter, Elizabeth Adams (1681–1766), who married the first minister of Windham, the Reverend Samuel Whiting (1670–1725). The chair became the pulpit chair of the Windham church, where it has remained until recently. As these later chairs suggest, turners trained in the Tinkham tradition may have continued working well into the eighteenth century, but after 1730 their designs are not readily distinguishable from others that also were subject to strong metropolitan influence.[11]

One working method of the Tinkham turners is distinctive and may help identify later chairs in the tradition. St. George asserted that “the scribed lines used by [Tinkham] . . . to demarcate the location of turned details . . . are in the same relative positions on all the chairs”; however, none of the pattern lines on chairs sampled for this article match. Unlike many turned chairs, which were made with a pattern stick formulated in the master’s shop and copied by his apprentices, their apprentices, and so on, the Tinkham chairs appear to have been laid out with a tool handle. Presumably, the turner used the length of the handle as a constant and calibrated fractional amounts by eye. This practice may explain the boring mistakes evident on at least three of the armchairs (figs. 25-27). Turners used scribed lines to locate their mortises and usually bored their joints either above or below the lines to prevent the mortises from intersecting where two horizontal members (stretchers or seat lists) enter the post at the same level. Most turners used wedges to clamp pairs of posts in a low assembly bench and aligned and bored the mortises simultaneously. Considering the rarity and complexity of large, intricately turned armchairs like the Tinkham ones and the somewhat pragmatic layout and production techniques described above, it is understandable that a turner might misbore one or more mortises, especially if he was in a hurry; nevertheless, the high incidence of boring errors seen in the Tinkham tradition is striking and demands more thorough investigation.[12]

The newly discovered Bartlett family chair and its Dutch prototype extend the stylistic chronology and probable date range of the Tinkham tradition and challenge St. George’s assertion that all this furniture could have been produced during the working life of one individual. New examples may turn up that will confuse or alter the analysis and dating proposed here, but that does not negate the importance of such exercises. Much more research needs to be presented and debated before scholars can fully understand eastern Massachusetts turned seating made before 1700.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Robert Blair St. George, Peggy Baker, Caroline Kardell, Jeremy Bangs, John Sinkler, George Neumann, Robert Bartlett Freeland, Fred and Anne Vogel, Gertrude Bancroft, Dudley and Constance Godfrey, Alfred Fredette, Henry and Lorene Cone, Eddy Nicholson, and John and Marie Vander Sande for their help at various stages of researching and writing this article. We are especially grateful for the help provided by Sophie Davidson, Peter Follansbee, Gavin Ashworth, and Luke Beckerdite.

Benno M. Forman, “Continental Furniture Craftsmen in London: 1511–1625,” Furniture History 7 (1971): 94–120.

St. George, Wrought Covenant, p. 46. For the Boston sources of some Plymouth turned ornaments on case pieces, see Robert F. Trent, “The Lawton Cupboard: A Unique Masterpiece of Early Boston Joinery and Turning,” Maine Antique Digest 16, no. 3 (March 1988): 1C–4C.

The origins of the John Carver history associated with this chair are obscure. The chair was donated to the Pilgrim Society in 1820 by Joseph Head of Boston, who also donated a pewter plate said to have belonged to Myles Standish. The entry in the minutes of the secretary to the Pilgrim Society acknowledging these donations mentions a letter from Head that accompanied the artifacts, but the letter has not been located. In 1995, Jeremy Bangs, former visiting curator of manuscripts at the Pilgrim Society, found an 1818 manuscript from a “Mr. Tufts Museum” in Plymouth that included a “Carver’s Chair” (Samuel Davis Papers, Pilgrim Society). Throughout the nineteenth century, the chair was thought to have belonged to Governor John Carver, who died in 1621. It was illustrated in several publications during the 1840s and 1850s, notably Alexander Young’s Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers (1841) and Calvin Wheeler Philleo, Jr., “A Pilgrimage to Plymouth,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 8, no. 43 (1853–1854): 49. The first attempts to determine the origin of the chair through microanalysis of the woods were either inconclusive or inaccurate (see Jonathan Fairbanks, “Four Pilgrim Chairs,” Winterthur Newsletter 9, no. 7 [September 30, 1963]: 1–3). A sample analyzed by the Department of Forestry at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1995 suggested that the chair is made partly of American ash; however, most wood anatomists dispute the validity of separating American and European ashes. The obvious inaccuracy of the Carver history has led to speculation that the chair descended from the Howland family, because John Howland came on the Mayflower as Governor Carver’s servant. The connection between a John Carver who died in Marshfield in 1679 and the early governor has never been established, and no reason exists to think the chair belonged to this later individual. How Joseph Head obtained the Carver chair and the Standish plate is unclear. The 1790 census lists two men named Joseph Head, one in Westport (Bristol County) and the other in Boston (Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in 1790, Massachusetts [Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1908]). The individual in Westport had ancestors in the Plymouth area but was not alive in 1820. The Joseph Head (1761–1836) of Boston was the son of John Head (1725–1776) of Ipswich in Suffolk, England, and his wife, Jane MacKenzie (1735–1818) of Scotland (Ann Felter Sandy, “Head Family History,” ms. dated July 4, 1992, Head Family Papers, Box 1, Massachusetts Historical Society). Joseph Head’s first wife, Elizabeth White Frazier (1764–1798), descended from an Ipswich, Massachusetts, family. His second wife, Lydia Chandler (1770–1837), was the daughter of merchant John Chandler and Lydia Ward of Petersham, Massachusetts. Lydia Chandler Head’s ancestors were from Roxbury. Although some members of this Roxbury branch of the Chandler family (who lived in Bristol, Rhode Island, and Woodstock, Connecticut) married descendants of Plymouth County families, no leads regarding the chair donated by Head have surfaced (George Chandler, The Descendants of William and Annis Chandler Who Settled in Roxbury, 1637 [Worcester, Mass.: Press of C. Hamilton, 1883], passim). A group of slat-back armchairs with pommels considerably greater in diameter than the posts have been associated with Lebanon and Norwich, Connecticut, since the 1890s. For more on these chairs, see Minor Myers, Jr., and Edgar D. Mayhew, New London County Furniture 1640–1840 (New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1974), p. 15. A somewhat more cogent analysis of these chairs is in Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 124–28.

The Russell chair, sometimes referred to as the Winslow chair or even the Winslow-Hayward-Russell chair, is illustrated in St. George, “A Plymouth Area Chairmaking Tradition,” p. 6, fig. 3. This illustration was silhouetted from a photo of the interior of the Harlow house in Plymouth taken about 1900. Because of this photo, St. George associated the chair with the Harlow family. He did not realize that the chair resided a few streets away in the residence of Allen D. Russell (1897–1984). Russell recalled that the chair was always known as the Winslow chair. Genealogical research by Mr. Russell’s daughter Mimi Aldrich and Robert F. Trent shows how the chair could have descended through the Winslow family to Mr. Russell: (2) Governor Josiah Winslow (1629–1680); to his son (3) Isaac (1671–1738); to his son (4) John (1703–1774); to his son (5) Pelham (1737–1784); to his daughter (6) Joanna Winslow Hayward (1773–1816), who married Dr. Nathan Hayward (1763–1848); to their daughter (7) Mary Winslow Hayward Russell (b. 1798), who married William S. Russell (1792–1863); to his nephew (8) John Jackson (1823–1897); to his son (9) John (1860–1939); to his son (10) Allen D. (1897–1984). New research suggests that both the Hayward and Winslow family lines are important in accessing the validity of tradition regarding the chair’s history. No probate inventory exists for Dr. Nathan Hayward of Bridgewater, one of several physicians in the extended Hayward-Winslow-Warren family. His wife (6) Joanna Winslow is more important. She and her sister, Mary Winslow Warren, were the only children of (5) Pelham Winslow and his wife, Joanna White (1744–1829) of Marshfield (Ruth McGyre and Robert Wakefield, Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, Edward Winslow [Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1997], pp. 18–19). At the outbreak of the Revolution, (5) Pelham Winslow and his cousin (5) Edward Winslow fled to Boston as Loyalists, and Pelham’s property was confiscated in 1779. The listing includes six mahogany chairs (PCPR, vol. 25, p. 458). Joanna and her two children remained behind in Plymouth. After Pelham’s death in 1784, what little remained of his estate could not support his widow and daughters (William T. Davis, Plymouth Memories of an Octogenarian [Plymouth, Mass.: Bittinger Bros., 1906], p. 163). Joanna White Winslow’s mother, Joanna Howland White (1716–1810), bequeathed her “the Bed Chairs and Looking Glass in the easterly back Chamber in which she usually sleeps,” but her will did not mention an armchair (PCPR, vol. 43, p. 446). Joanna White Winslow’s father was (5) Gideon White (1716–1779) of Plymouth. His probate inventory lists “1 armed Chair” valued at £6 in inflated Continental currency (PCPR, vol. 28, p. 16). Gideon’s father, Cornelius (1682–1755), had a group of unspecified chairs listed in his inventory (PCPR, vol. 14, p. 402). Cornelius’s wife, Joanna Howland, was the daughter of Thomas Howland (d. 1741), a prosperous landowner of Plymouth. His inventory included “1 Great Chair” worth 10s. (PCPR, vol. 8, p. 135). This is one possible source for the “Winslow” chair. Returning to the direct Winslow line, no inventory exists for (4) General John Winslow, who died intestate just before the Revolution; however, his father’s generation provides extremely important documentation. (3) Isaac Winslow (ca. 1671–1738) and his wife, Sarah Wensley (1673–1754), owned a large Marshfield farm called “Careswell,” which he inherited from his father, Governor Josiah. In 1699, Isaac built a large house that, with alterations made by his son, still stands. His probate inventory contains only a generalized listing for chairs (PCPR, vol. 8, p. 29), but his wife’s inventory, taken in inflated old Tenor currency, lists one old chair at £1.6.8. Other chairs are described as cane back, flowered (presumably needlework or turkeywork rather than veneered), and easy. The “old chair” could be the one shown in fig. 1 (PCPR, vol. 13, p. 327). Isaac Winslow’s father, Josiah, died in 1680, which is too early for the latter to have owned the chair. Barring a more thorough search of the evidence, it does not seem possible to corroborate the Winslow-Hayward-Russell history. The aforementioned William S. Russell (1792–1863) was the Plymouth town clerk and author of Guide to Plymouth and Recollections of the Pilgrims (1846). His first cousin, Nathaniel Russell II (1801–1853), owned the William Bradford turned armchair, which he inherited from his mother’s LeBaron ancestors, who were Bradford descendants.

The Churchill chair survives in fragmentary condition. Only the right front post is entirely original. The right rear consists of an original maple upper half and a replaced ash lower half. The replaced left front post is oak, and the replaced right rear post is ash. Only two of the spindles in the back are original, but all those under the arms are original. The spindles under the seat, which appear to have been moved up one stretcher in the frame, are replacements. The chair was probably cut down in height due to severe insect infestation. Subsequent infestation probably prompted the wholesale replacement of many parts. The Churchill chair is illustrated and discussed in St. George, “A Plymouth Area Chairmaking Tradition,” p. 5, fig. 2; Cullity, A Cubberd, Four Joyne Stools & Other Smalle Thinges, p. 124; and Helen Comstock, “Pilgrim Chairs,” Antiques 68, no. 5 (November 1955): 451. Comstock suggested that the chair was originally owned by Eleazor Churchill, the son of John Churchill who arrived in Plymouth by 1643. As both St. George and Comstock noted, colonial revival architect Joseph Everett Chandler of Boston donated the chair to Pilgrim Hall. His father, Albert H. Churchill Chandler, was the son of Joseph Chandler and Eliza Churchill of Duxbury. Although St. George suggested that Eliza had inherited the chair, it may have entered the Chandler family through another route. Albert H. Churchill Chandler married Adeline F. Harlow of Plymouth, and the couple shared at least two ancestors. The most plausible line of descent for the chair through the Churchill family is similar to that proposed by St. George, except that he skipped one generation. This line is as follows: (1) John Churchill to (2) Eleazor Churchill (1652–1716), to (3) Stephen Churchill (1685–1750), to (4) Stephen Churchill (1717–1751), to (5) Stephen Churchill (b. 1743), to (6) Peleg Churchill (1769–1810), to his daughter (7) Eliza, who married Joseph Chandler.

Moving backwards through the Churchill line, several other ways in which the chair might have descended become apparent. Peleg Churchill of Plymouth married Hannah Hosea of Duxbury in 1791. He was a cooper who died in 1810 with unspecified furniture listed in his inventory (PCPR, vol. 43, p. 362). Peleg Churchill’s contemporary, Joseph Chandler (1769–1795) of Kingston, was another great-grandfather of Joseph Everett Chandler, the donor. The former Joseph’s inventory listed “2 great chairs, 3 crow foot chairs & 6 common Ditto” (PCPR, vol. 35, p. 190). Perhaps one of these great chairs is the example in question.

(5) Stephen Churchill of Plymouth married Lucy Burbank in 1766. No probate documents survive for either of them. His father, Stephen (1717–1751), married Hannah Barnes (1718–1793) of Plymouth in 1738. The inventory for Stephen of the fourth generation contains a generalized reference to chairs (PCPR, vol. 13, p. 106). The Barnes family of Plymouth had genealogical ties to the Bartletts, Churchills, Chandlers, Standishes, and Carvers, all of whom have some association with chairs in this article. The Barnes family descends from (1) John Barnes, who was a resident of Plymouth by 1633, and his wife, Mary Plummer. (4) Hannah Barnes Churchill’s father, Jonathan Barnes (b. 1684), was a brother of (3) William Barnes (1670–1751/52), who was the great-great-great-grandfather of Adeline Harlow, mother of Joseph Everett Chandler, the donor of the Churchill chair. William Barnes married Alice Bradford (1680–1725), daughter of William Bradford and (3) Rebecca Bartlett. William and Jonathan Barnes’s brother (3) John married (4) Mary Bartlett, daughter of (3) Joseph Bartlett. The Barnes brothers’ sister (3) Mary (b. 1667) married John Carver of Duxbury. Their daughter, Mary Carver (b. 1695), married Thomas Standish. The aforementioned genealogical information is derived from William T. Davis, ed., Genealogical Register of Plymouth Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1975), pp. 10–12, 51–59, 124–29; Robert Wakefield, ed., Robert Bartlett of the Anne, pp. 54–5; Robert Wakefield, ed., Mayflower Families Through Five Generations: Family of Myles Standish (Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of the Mayflower Descendants, 1996), p. 13.

Stephen Churchill (1685–1750) of the third generation married Experience Ellis of Sandwich in 1708. His probate inventory has a single entry for chairs (PCPR, vol. 12, p. 426). Experience Ellis was undoubtedly related to Benjamin Ellis, the owner of the chair shown in fig. 17. Information on the second generation is sparse. Eleazor Churchill (1652–1716) married a Mary whose family is unknown. No probate documents exist for them. His daughter, Jedidah Churchill (b. 1687), married Thomas Harlow (b. 1686), a distant ancestor of Adeline Harlow. Although no exact probate references confirm the presumed line of descent of the Churchill chair cited by St. George, this one is the most plausible. The donor’s mother also had ties to the Churchill family. Almost all the donor’s ancestors were from Plymouth.

Of all the documented Tinkham-type chairs, the Fairbanks example was found farthest from Plymouth County. The chair was purchased by an antiques dealer from Nellie Fairbanks Beane of Phillips, Maine, in the early 1960s. Nellie was a tenth-generation descendant of Jonathan Fairbanks (d. 1668), who built the core of the extant Fairbanks house in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1637. His descendants in Nellie’s direct line remained in Dedham and Wrentham (near the Rhode Island border) until Joseph Fairbanks (1717–1794) and his wife, Frances, moved to Winthrop, Maine. Their descendants in Maine had three connections to Plymouth area families. (6) Captain Benjamin Fairbanks (1747–1828) married Keturah Luce (1749–1807) of Martha’s Vineyard. Her parents were Joseph Luce (1725–1762), whose family had resided on Martha’s Vineyard for three generations, and Deborah Woolen. Deborah’s maternal grandparents, Stephen Presbury (ca. 1672–1730) and Deborah Skiff (1668–1743), moved to the Vineyard from Sandwich on Cape Cod. They are of the appropriate generation to have purchased the chair. Deborah Skiff’s parents, Stephen Skiff (1641–1710) and Lydia Snow (1640–1711), were from Marshfield. Other members of the Fairbanks family in Maine had ties to Plymouth County, although they are not in the last family owner’s direct ancestral line. They include Captain Benjamin Fairbanks’s brother, (6) Colonel Nathaniel Fairbanks, whose second wife’s ancestors included Chipmans and Watermans, and Benjamin’s son, (7) Columbus Fairbanks (1793–1882), who married a Tinkham. The aforementioned genealogical information is derived from David Thurston, A Brief History of Winthrop (Maine) from 1764 to October 1855 (Portland, Maine: Brown Thurston, 1855), pp. 181–83; Donald Lines Jacobus, Descendants of Robert Waterman, 3 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Edgar F. Waterman, 1939), passim; Robert S. Wakefield, Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, Peter Brown Family (Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1992), passim; Robert S. Wakefield, Mayflower Families in Progress, Richard Warren of the Mayflower (Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1997), passim; Isaac Cobb, “Cobb Genealogy,” unpublished manuscript, Burbank, California, 1979, passim; Philip Cobb, A History of the Cobb Family (Cleveland, Ohio: privately printed, 1907), passim; and Martha McCourt et al., The American Descendants of Henry Luce of Martha’s Vineyard (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1994), passim.

The present owner of the Fairbanks chair commissioned studies of it by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities Conservation Center in 1989. David H. Mitchell examined the structure of the chair, and Joseph Godla performed pigment analysis. The Carver and Winslow chairs (figs. 1, 16) retain some of their original paint, but neither has been sampled for analysis. The Carver chair appears to have been painted entirely black, whereas the Winslow example was red.

These two chairs were first published in Cullity, A Cubberd Four Joyne Stools & Other Small Thinges, p. 125. Norwich turned chairs (see Minor Myers, Jr., and Edgar D. Mayhew, New London County Furniture, 1640–1840 [New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1974], p. 15; and Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 124–28) are a prime stylistic source for many later chairmaking traditions in Connecticut that featured slanted turned arms, and many of these traditions also featured outsized pommels or hand grips. For examples of these traditions, see Robert F. Trent, Hearts & Crowns: Folk Chairs of the Connecticut Coast 1720–1840 (New Haven, Conn.: New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1977), pp. 56–59 and 82–86. R. Ridgeway, “Governor Bradford’s Chair,” Windham Historical Society Newsletter, July 1983, pp. 4–6.