Introductory panel to the exhibition, Furniture of the American South. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Sideboard table attributed to William Buckland and William Bernard Sears, Richmond County, Virginia, 1761–1771. Cherry with beech. H. 32", W. 453/8", D. 311/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tall clock attributed to Peter Rife and Peter Whipple, Southern Valley of Virginia, probably Montgomery (now Pulaski) County, ca. 1810. Mahogany, mahogany veneer and cherry with tulip poplar, oak, black walnut, holly, cherry, maple, horn, bone, silver, and brass; iron, brass, and steel movement. H. 1081/2", W. 25", D. 15". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

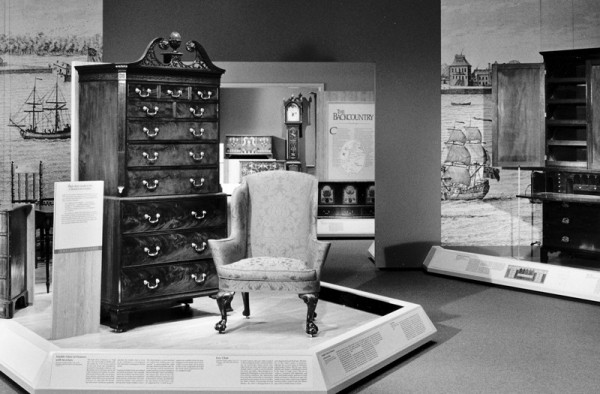

Interior view of the southern furniture exhibition showing four important masterpieces, a mahogany easy chair, 1765–1775, and mahogany double chest with open carved pediment, 1765–1780, made in Charleston, South Carolina, on display in the Carolina Low Country gallery, juxtaposed against a painted chest, 1795–1807, and tall clock, 1800, by Johannes Spitler of Shenandoah (now Page) County, Virginia, in the gallery on furniture of the southern Backcountry. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown. Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection. Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1997. 639 pp.; numerous color and bw illus., line drawings, maps, glossaries, bibliography, index. $75.00.

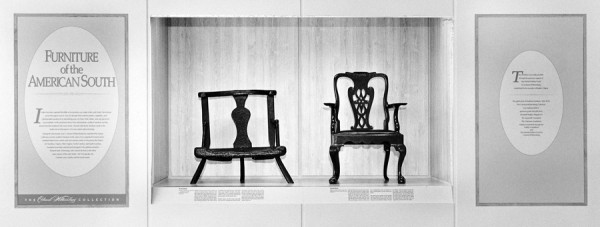

“Furniture of the American South: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection.” DeWitt Wallace Gallery, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, November 21, 1997, to December 1998.

To those familiar with the study of southern furniture over the past five decades, the story of Joseph Downs’s lecture at the first Williamsburg Antiques Forum in 1949 has become legendary. Then curator of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Downs announced that “little furniture of artistic merit was ever produced south of Baltimore.” During the question and answer period that followed, one southern matron rose from her chair with quiet indignation to ask politely, “Mr. Downs, did you make that remark out of prejudice or ignorance?” Downs’s comment had the perhaps fortunate effect of sparking a new civil war in American decorative arts, spawning the landmark 1952 exhibition “Furniture of the Old South, 1640–1820” at the Virginia Museum and a special issue of The Magazine Antiques dedicated to southern furniture. In 1965, at least partly in response to Downs’s remark, Frank L. Horton established the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which has been the major research engine for the study of southern material culture, setting out to prove the existence of meritorious furniture produced in the antebellum South. Now, almost fifty years after the infamous Downs lecture, Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, curator and assistant curator of furniture at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, have produced a scholarly book, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, with a special exhibition of southern furniture in Colonial Williamsburg (fig. 1), which definitively ends this civil war. With 639 pages of careful, documented analysis, Hurst and Prown have produced a milestone in the study of not just southern but American furniture. To play on Downs’s own words, few books of equal merit have ever been published north of Baltimore.

Serious scholarship in southern furniture developed more slowly than furniture scholarship in the North. Since 1920, for example, more than two hundred books have been written on furniture production in the New England and Middle Atlantic colonies, whereas fewer than a dozen have been published on the South. The earliest book on southern furniture, Paul H. Burroughs’s Southern Antiques (1931), was essentially a photographic essay with lengthy captions on provenance. This work was followed by several more scholarly monographs analyzing the furniture of particular southern subregions, most importantly, E. Milby Burton’s Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825 (1955), Wallace Gusler’s Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (1979), and John Bivins’s The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820 (1988). In 1975, MESDA initiated an aggressive publication schedule, launching the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts followed by the Frank L. Horton book series. Numerous articles over recent years in the MESDA journal and in other scholarly venues by Hurst, Prown, Gusler, Bivins, and others—most notably, Luke Beckerdite, Sumpter Priddy, Bradford Rauschenberg, and Thomas Savage—have promoted our understanding of specific aspects of southern furniture. As the first comprehensive study of furniture produced in the South, Hurst and Prown’s book stands at the apex of this mountain of research and promises to remain the standard work in the field for the next generation.

The authors have achieved one of the most reader-friendly books on American furniture yet written. As a catalogue of the Colonial Williamsburg collection, it presents 183 of the nearly 700 southern furniture objects in the foundation’s collection. The book is brilliantly organized by furniture group, enabling the reader to move quickly through sections on seating furniture, tables, case furniture, and other, more highly specialized forms to find the objects and categories that might be of particular interest. The book incorporates extensive use of maps, illustrations, photographs, line drawings of construction details, glossaries of furniture terminology, and a comprehensive bibliography of titles previously published on southern furniture. An abundance of information useful to both curators and collectors on the materials and construction techniques used throughout the region is also provided.

Ironically, Hurst and Prown have extended the cataloging methodology first devised by Joseph Downs more than forty years ago in his groundbreaking book American Furniture, Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (1952) to its fullest potential with complete descriptions of construction, condition, materials, dimensions, marks, and provenance. Each catalogue entry begins with a thorough discussion of the object, its known history, regional context, development of the furniture form, and specific information on the maker and patron, drawing from extensive documentary research through period newspapers and probate inventories of the region. Each entry is fully referenced and endnoted. Extensive color photography, funded by a grant from the Chipstone Foundation, combines with numerous black and white photographs of construction details and of similar, related objects to make the book visually as well as intellectually stimulating.

In the opinion of this reviewer, the authors’ most important contribution has been to slay many of the subtle prejudices that have tagged the South since General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomatox in 1865. Jonathan Prown explained in his recent article in the 1997 issue of American Furniture that, since that moment in our nation’s history, American historians have traditionally viewed the South as a “culturally impaired place.” “In the American furniture story,” Prown continued, “southern furniture exists less as an accepted regional craft tradition than as a chronic interpretive problem.” The authors quickly move beyond such models of traditional, “good-better-best” furniture connoisseurship to illustrate the need to examine southern furniture within the broader context of regional material culture for a better understanding of American culture generally. E. Milby Burton stated as early as 1955 in his monograph on Charleston furniture, “The culture of any society, whether it be primitive or highly civilized, is unerringly revealed by the material things which the society needs and the degree of skill which it displays in producing or acquiring them.” The material culture studies approach has characterized the southern furniture school for the past several decades, greatly advanced by the establishment of MESDA and the publication of Wallace Gusler and John Bivins’s books on eastern Virginia and North Carolina furniture. Slowly, the material culture approach has been incorporated into more recent publications on northern regional furniture such as Brock Jobe’s Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast (1993) and Kenneth Zogry’s “The Best the Country Affords”: Vermont Furniture, 1765–1850, but Hurst and Prown have raised this model of furniture analysis to a new level. [1]

In the preface, Hurst points to the national importance of the argument, noting that on the eve of the American Revolution the Old South, comprised of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, constituted almost half the United States’ land mass with more than 46 percent of its population. “Until students of material culture have greater access to information about the furniture made and used by the people in this vast territory,” argues Hurst, “our understanding of the early American furniture trade will be fragmentary at best.”

The opening essays written by Hurst on the Chesapeake, Prown on the Backcountry, and Thomas Savage of Historic Charleston Foundation on the Carolina Low Country, explore the cultural, social, and economic factors that define the three principal subregions of the South. These essays present the important themes that are woven throughout the book, most significantly the region’s generally misunderstood and under-appreciated ethnic diversity. As a geographic and socioeconomic entity, the South can be defined by at least six major, unifying characteristics: a warm climate and topography conducive to agriculture, relatively inexpensive and readily available land, an alluvial transportation system, an agrarian economy, a labor system based partially (but not exclusively) on race-based chattel slavery, and settlement patterns that by the late eighteenth century were generally stable. Within this dynamic region, however, numerous subregions existed (far more than just the Chesapeake, the Low Country, and the Backcountry), each with its own unique character manifested through furniture production. The first key to understanding “southern” furniture is the realization that there was never a monolithic “South.”

Although the South clearly began as an English settlement with the arrival of colonists at Jamestown in 1608, the influence of Continental Europeans from the Netherlands, Germany, and France was significant enough by the late seventeenth century to broadly impact the region’s material culture. The Dutch enjoyed an extensive trade in Chesapeake tobacco throughout the seventeenth century and established half a dozen permanent trading stations. In his introductory essay to the Carolina Low Country, Thomas Savage points out that from its inception in 1670 the South Carolina colony was a multiethnic polyglot of settlers who were not only English, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh but also French Huguenots, Dutch, Germans, and Swiss, combined with Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal. Fewer than two dozen examples of the South’s earliest furniture from the seventeenth century have survived, although the specimens that remain clearly show enough Continental European influence to differentiate them from the more English furniture of the New England colonies. These pieces are discussed thoroughly in Hurst and Prown’s book.

In his lecture at the 1997 symposium co-sponsored by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the Chipstone Foundation, James P. Whittenburg, professor of history at the College of William and Mary, suggests a new reason for the narrow survival rate of seventeenth-century southern furniture, aside from the widely accepted notions regarding the effects of climate, war, post–Civil War poverty, and destruction. In his comparative analysis of the southern and New England colonies, Whittenburg discerns development versus declension models for the two regions. In the South seventeenth-century furniture objects would have been relatively quickly discarded and exchanged for objects in the latest style (like the unused toys of overgrown children). Seventeenth-century New England furniture, on the other hand, became like holy relics to a bygone era, essential to connecting the descendants of the founding settlers to the symbolic, religious beginnings of their colony. The economic development model advanced by Whittenburg is another important key to understanding southern furniture and the development of the southern cabinetmaking industry.[2]

As Hurst and Savage discuss in their introductory essays, by the mid-eighteenth century, economic progress in the South was such that plantation owners in the Chesapeake and Low Country enjoyed the highest per capita incomes in British North America. The major coastal towns—Charleston, Williamsburg, and Annapolis—received constantly replenished waves of emigrating British cabinetmakers. Unlike their northern counterparts who frequently represented multigenerational craft traditions within particular families and communities, these tradesmen sought to fill the needs of the expanding local market and eventually hoped to retire from trade by purchasing land and slaves to secure for their children the lifestyle of the planter gentry. These emigrants brought training and a reliance on British pattern books to produce furniture deeply rooted in British cabinetmaking traditions. Their case furniture typically featured urban British construction practices with full dustboards, panel-and-frame backs, stacked foot blocking, and drawer bottoms with glue blocks. These traits became hallmarks of the “neat and plain” style typical of coastal southern furniture. Although less adorned than exuberantly carved, rococo Philadelphia high chests or bombé Boston case pieces, their furniture was structurally superior to that of most northern cabinetmakers. Importantly, the preference for such “neat and plain” furniture, as it was called, embodied a social ideology as well as a design choice. In 1772, Peter Manigault, a wealthy Low Country planter and Speaker of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, wrote to his London factor ordering furniture “the plainer the better so that it is fashionable.” A contemporary description of the style defined it as “free from what is unbecoming, inappropriate, or tawdry; simple elegance; tasteful and refined.” In many ways, the “neat and plain” style represents a solid cultural expression of the coastal planter class who sought to emulate the British country gentry through the creation of landed estates with primogeniture, republican government, and an established Anglican church.[3]

Hurst’s catalogue entry for a marble-top sideboard table (fig. 2) attributed to William Buckland (1734–1774) and William Bernard Sears (d. 1818) highlights many of the important themes presented in his essay. The table was designed by Buckland and carved by Sears for the Tayloe family of Mount Airy plantation in Richmond County, Virginia. Born in Oxfordshire, England, Buckland epitomized the successful southern tradesman. Migrating to Virginia after completing his apprenticeship in house joinery in London in 1755, he quickly enjoyed the patronage of many of northern Virginia and Maryland’s most prominent planters. Buckland’s most important commissions include Mount Airy and Gunston Hall in Virginia and the Chase-Lloyd and Hammond-Harwood houses in the town of Annapolis. The legs on his Mount Airy sideboard table point to his architectural training and reliance on British pattern books for design by resembling the consoles for a chimneypiece in Abraham Swan’s, The British Architect; or, The Builder’s Treasury of Staircases (London, 1745). The table as well as another marble-top sideboard table designed by Buckland for Mount Airy in the MESDA collection reflect his most “aspiring” designs and speak to the ambitiousness of both artisan and patron in eighteenth-century Virginia. William Bernard Sears’s work as both a house and furniture carver further illustrates the flexible role required of woodworkers in the agrarian, mostly rural, southern economy.

In his essay on the Backcountry, Jonathan Prown speaks brilliantly to the rich furniture traditions that developed in this unique, but misunderstood, American region. The Backcountry was settled by migrants from the coastal South who fanned out in search of additional land. They mingled with Germans, Swiss, and Scots-Irish, many newly arrived to America, who had traveled down the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and the Piedmont region of the Carolinas and Georgia. Important religious communities in the Backcountry included Moravians from central Germany and Mennonites from the Palatine. Small pockets of Quakers and Baptists transplanted from New England added to the region’s diverse ethnic mix. Each group contributed to the region’s distinctive furniture making traditions. The high chest form, for example, which was eschewed throughout the coastal South in favor of the more quintessentially British double chest form, developed in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia due to Pennsylvania migration. Similarly, the chests-on-frame commonly found in Randolph County, North Carolina, suggest the influence of New Light Baptists who migrated to the Piedmont from the Connecticut River Valley of New England. The decorative painting on many western Virginia case pieces strongly reflects a Germanic contribution. Although a desk-and-bookcase by the highly eccentric Martinsburg, Virginia, cabinetmaker John Shearer might not accord easily with modern, twentieth-century, decorator-inspired concepts for a Manhattan brownstone or neo-Georgian mansion on the Philadelphia mainline, Prown explains that Backcountry furniture should be seen within the context of its place and time as an expression of our American culture.

Prown’s catalogue entry for a tall clock (fig. 3) made in the southern valley of western Virginia by Peter Whipple and Peter Rife, for example, suggests the highly complex character of Backcountry furniture. It was made for Sebastian Wygal (1762–1835), the son of a Swiss emigrant who migrated to southwestern Virginia from Pennsylvania in the 1750s. Similarly, Peter Rife was born in Rockland Township, Pennsylvania, and resided in Montgomery County by the 1770s. Rife’s patron, Sebastian Wygal, was a prosperous man who owned slaves and more than two thousand acres in Montgomery County, Virginia. Rife’s tall clock speaks to his ambition as a Backcountry artisan. The clock case combines nearly every variety of wood and other materials available to a cabinetmaker working in southwestern Virginia in the early nineteenth century. Symbolically, its inlay combines neoclassical design with Germanic folk traditions, surmounted in the tympanum by an American eagle.

Throughout their book, Hurst and Prown introduce important, new characters into the lexicon of American cabinetmaking: important southern craftsmen working in the Backcountry such as Johannes Spitler of Shenandoah (now Page) County, Virginia, and artisans who practiced their craft in the major southern towns and cities such as Chester Sully of Norfolk, William King of the District of Columbia, and Thomas Lee of Charleston. American furniture scholars have been familiar for some time with only a handful of the best-known, best-documented southern furniture makers, such as Anthony Hay and Peter Scott of Williamsburg, John Shaw of Annapolis, and Thomas Elfe of Charleston, but by their use of the signed, labeled, and documented examples of southern furniture in the Colonial Williamsburg collection, Hurst and Prown have expanded our knowledge of American, not just southern, cabinetmaking. Combined with their exhibition, the publication of Hurst and Prown’s book guarantees that henceforth serious American furniture scholars will be required to know the names of Spitler, Sully, King, and Lee as well as Goddard, Townsend, Dunlap, and Dominy.[4]

On long-term display at the DeWitt Wallace Gallery, the southern furniture exhibition (fig. 4) follows the book’s lead as a well-organized, user-friendly presentation of its topic. Designed by Rick Hadley with impressive curatorial supervision by Hurst and Prown, it effectively outlines the important topics essential to explaining southern furniture. It elucidates the region’s major settlement and migration patterns, the impact of emigré craftsmen on southern furniture, the region’s multiethnic influences, the importance of European pattern books on its designs, the role of the woodworker in the agrarian southern economy, the impact of changing technologies on southern cabinetmaking, and furniture making’s eventual decline as mechanized factories in the North began to export cheap, mass-produced goods to the southern market. The exhibition moves visitors geographically through the South with galleries dedicated to furniture of the Chesapeake, the Low Country, and the Backcountry. As one of the most dynamic and interesting urban centers in the South, Baltimore receives its own gallery.

Interesting education tools incorporated into the display include an exhibition for schoolchildren on joinery and three videos, totaling twenty-seven minutes, on the three principal subregions of the South, the steps of timber production from felled tree to finished lumber, and the making of an eighteenth-century-style tea table by artisans in the Anthony Hay cabinet shop in Williamsburg.

In this reviewer’s opinion, the book’s single shortcoming is its failure to include an introductory essay by the two authors on the principal themes that are carefully and thoughtfully presented in the exhibition. A succinct discussion by Hurst and Prown on the major developments of southern cabinetmaking, its defining characteristics, and its general trends would have been an important and welcome addition to the book. These topics are discussed intermittently in the three introductory essays and woven throughout the catalogue entries but are systematically explained only in the exhibition, making a visit to the Wallace Gallery an important addition to reading the book.

The initial image upon entering the exhibition (fig. 1), for example, is a thought-provoking presentation. It explains the tremendous diversity of southern furniture by contrasting an elaborately carved mahogany armchair of 1745–1765 produced in Edenton, North Carolina, with an unusual armchair made between 1770 and 1800 found in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, earlier this century. Although both chairs feature similarly designed splats and served the same obvious seating function, the Edenton chair relates closely to known British prototypes for drawing room and dining room chairs and speaks to the increasing collectability of high-style southern furniture. The design of the Maryland chair, on the other hand, is deeply rooted in vernacular Welsh tradition, resembling similar, three-legged, low-lying chairs found in western Great Britain used for hearthside cooking that suggest its original use by a white indentured servant working in an eighteenth-century Maryland, plantation kitchen. Hurst and Prown have united both these examples for a better understanding of the complexity of southern furniture.

The dean of southern furniture studies, Frank L. Horton, has pronounced Hurst and Prown’s book the finest cultural study of American furniture yet published. Hopefully, it will inspire future publications on the various, unique subregions of the South, especially those areas not discussed in the book such as Kentucky and Tennessee. Hurst and Prown’s book should lay to rest many of the antagonisms that have divided northern and southern furniture historians since the famous Joseph Downs lecture. Southern furniture historians have earned their place at the proverbial American gate-leg table and should remove any leftover chips from shoulders. Like the famous Civil War veterans’ reunions that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century, it is time for scholars of northern and southern furniture to meet in the center of the field and recognize the important contributions that both sides have made to our national understanding.

Robert A. Leath

Historic Charleston Foundation

Jonathan Prown, “A ‘Preponderance of Pineapples’: The Problem of Southern Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1997), p. 4. E. Milby Burton, Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825 (Charleston: Charleston Museum, 1955; reprint, Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1970), p. 3.

James P. Whittenburg, “Myths and Realities Revisited: More Societies of the Colonial South,” unpublished lecture delivered on November 14, 1997, at the symposium, A Region of Regions: Cultural Diversity and the Furniture Trade in the Early South, co-sponsored by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the Chipstone Foundation.

Peter Manigault to Benjamin Stead, April 2, 1771, as quoted in “The Letterbook of Peter Manigault, 1763–1773,” edited by Maurice A. Crouse, South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 70 (July 1969): 188–89.

Prown, “A ‘Preponderance of Pineapples,’” p. 4.