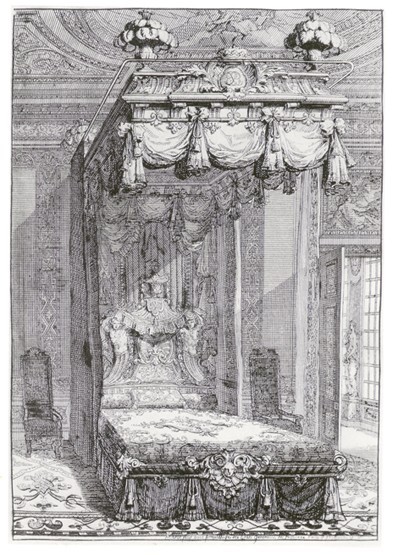

Design for a state bed in Daniel Marot, Second Livre d'Apartments, ca. 1702. (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Studies in Landscape Architecture.)

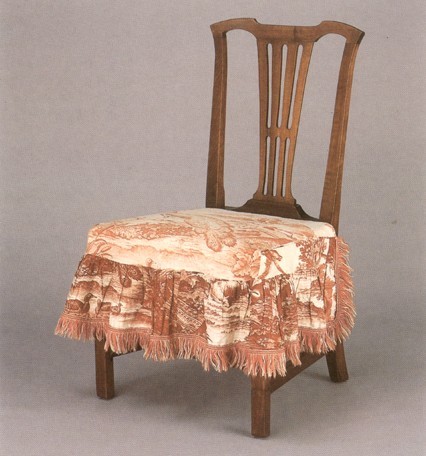

Cover for a side chair, plate printed in England by Robert Jones, Old Ford, 1761—1780. Cotton with wool and cotton fringe. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1963—36, 12.)

Cushion cover for an easy chair, plate printed in England by Robert Jones, Old Ford, 1761—1780. Cotton with wool and linen binding over the seams and cotton and wool fringe. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1963—36, 10.)

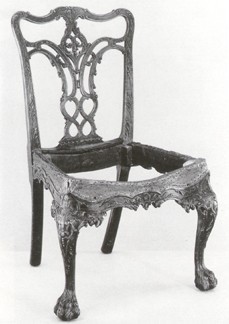

Side chair, Philadelphia, 1769—1770. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 37", W. 24", D. 24'. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1964—680. )

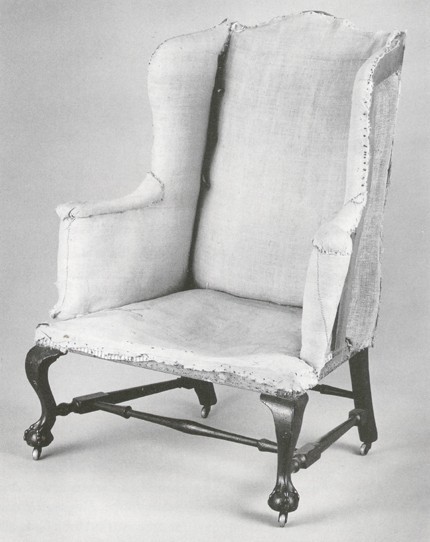

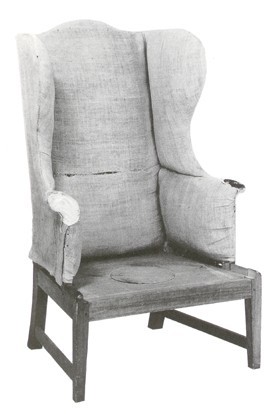

Easy chair, Massachusetts, 1760—1770. Mahogany with maple; linen foundation upholstery. H. 47 1/2", W. 34", D. 26". (Chipstone Foundation, ace. 1991. 2; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

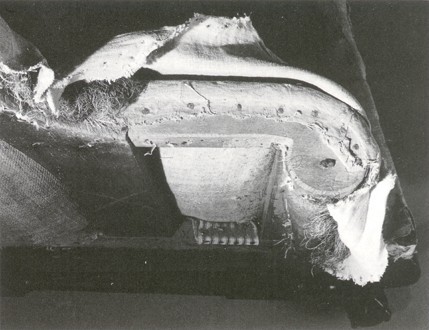

Detail of the upholstery evidence on the easy chair illustrated in fig. 5. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.) The only period tack evidence on the stiles and seat rails is for the linen cover. During conservation, an eighteenth-century pin was found between the inner back and side panels. The loose cover may have been pinned temporarily in this area.

Detail of the arm of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 5. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.) This view shows the original grass roll, curled horsehair stuffing, and linen cover (pulled back). The tack holes in the cover match those on the arm; there is no tack or nail evidence or stitching in the arm area that would indicate fixed upholstery.

Easy chair, Rhode Island, 1785—1795. Cherry with maple and white pine; linen foundation upholstery. H. 46", W. 30", D. 26 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mrs. Eleanor U. Sargent, acc. 1977—215.)

Cover for the back of an armchair, England, 1680ñ1700. Embossed leather. H. 30", W. 26". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1954—985.)

Cover for a table, England, 1675—1700. Embossed leather. H. 1 1/2", D. 27". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1966—415, 2.)

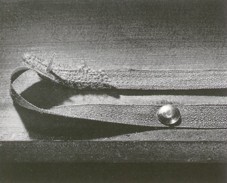

Commode cover, England, 1765-1775, Embossed leather. Dimensions not recorded. (Museum of Leathercraft; photo, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

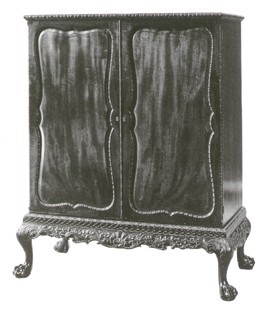

Clothespress attributed to Giles Grendey, London, 1735—1745. Mahogany with oak and deal. H. 65 1/4", W. 52 1/2", D. 27 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, ace. 1956—298.)

Interior of the clothespress in fig. 12 showing sliding trays with nail holes and fragments of tape trapping green baize. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the green baize trapped beneath nail heads on the sliding trays of the clothespress in figs. 12, 13. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

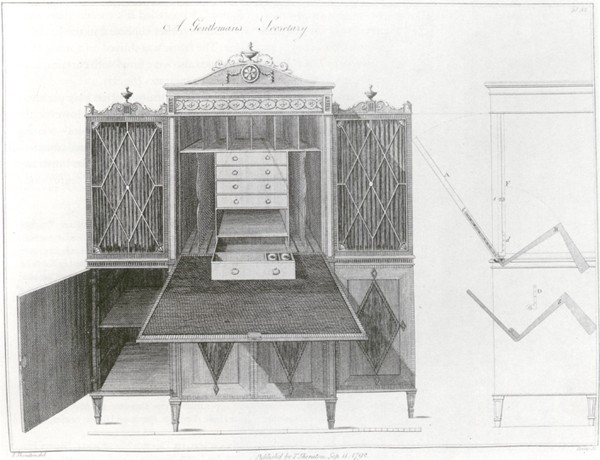

"A Gentleman's Secretary" from Thomas Sheraton's The Cabinet-Maker and Up holsterer's Draming-Book (1802). (Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Printed Books and Periodical Collection.)

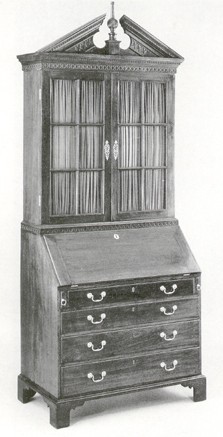

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the Anthony Hay shop, Williamsburg, 1765—1770. Walnut with yellow pine and walnut. H. 95 1/2", W . 39 1/8 ", D. 20 3/8". The silk curtains are reproductions. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1978—9.)

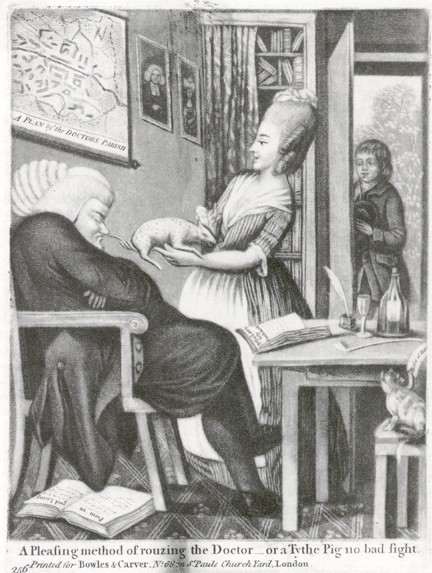

A Pleasing Method of Rouzing the Doctor, printed for Bowles and Carver, London, 1765—1775. Mezzotint. 10 1/2" x 8 1/2". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. 1941—230.)

In many ways, the finest textiles and furnishings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries functioned more for display than use. Yet householders were keenly aware of the destructive effects of sunlight, dust, and wear on their textiles, furniture, and domestic goods. To mitigate the problem, they frequently turned to less costly materials to cover their expensive furnishings, sometimes carrying protection to the extreme of encasing these objects entirely and removing the covers only for formal occasions. The concept of protecting material goods ranged from objects as small as the contents of a desk to those as large as entire beds and room-size carpets.

Decorative floors and carpets often had protective covers. Although leather covers occasionally were used to protect patterned wood floors, woolen textiles were preferred for covering carpets, probably because leather would more easily tear from a shoe heel sinking into the resilient carpet beneath. Baize and serge frequently were used for covers in the eighteenth century. The "Elegant Turkey carpet" in Aaron Burr's New York residence was protected by "a Carpet of Blue Bays." Sir Lawrence Dundas had in the front room of his London townhouse, "A large Carpet, [and] A green baize cover to do." In England and her colonies, both patrons and tradesmen realized that covers were essential to protect expensive carpets from wear and fading. When Ninian Horne wrote to Chippendale, Haig and Company about a carpet, he insisted that "there must be a covering for it of green serge." Thomas Sheraton summed up the practice of covering carpets in his Cabinet Dictionary (1803) noting that "bays" was used "to cover over carpets, and made to fit round the room, to save them." Where loose carpets had loose covers, wall-to-wall carpets often had specially fitted covers that could be attached to the floor. On January 10, 1778, Chippendale charged Sir Gilbert Heathcote £1.2.0 for "Thread and piecing out the Serge Carpet in [the] Breakfast room to fit the floor, making Eyelet holes in do and laying down with studs Compleat."[1]

Furnishings as large as beds also were slipcovered. Daniel Marot's early-eighteenth-century designs for state beds included several with an outside compass rod for curtains that could be drawn around the bed to enclose it and prevent the decorative curtains from fading (fig. 1). The red and gold state bed at Dyrham Park originally had case curtains, and the upper frame has holes where rods for these curtains were fastened. Late-seventeenth-century inventories for Ham House near London list "case curtains" for most of the important tall post beds. These were made out of white "plading" (wool), white serge (wool), yellow "sarsnet" (silk), and India silk.[2]

The use of loose, often wrinkled, slipcovers on upholstered chairs and sofas is well documented in original records, print sources, and surviving examples (figs. 2, 3).[3] Wool serge cases were gradually superseded during the second half of the eighteenth century by washable linens or cottons, usually of a color or pattern to match the rest of the furnishings in the room. Checks and stripes were preferred for public rooms such as libraries or parlors, whereas printed cottons were favored for bedchambers where the slipcovers often matched the bed hangings. The plate-printed covers illustrated in figures 2 and 3 were once part of matching textile furnishings for a bedchamber that included a tall post bed, an easy chair, and several side chairs. Virginian Robert Beverley, who ordered many of his furnishings directly from England, wanted all the furnishings of his parlor, including the case covers, to be en suite with the wallpaper. On July 16, 1771, he ordered:

3 yellow Damask window Curtains of Stuff worstit with Pullies to draw up to the Top of the Window, 11 Feet high & 4 Feet six Inches wide, the Colour to be the same as the ground of the rich yellow Paper wch I described 12 neat plain mahogany Chairs, with yellow worstit Stuff Damask Bottoms like the Curtains, & spare loose Cases of yellow & white Check to tie over them. The Bottoms all to be loose & not nailed with brass Nails, wch I dislike much & the Covering of the Hair [stuffing], with wch the Bottoms are filled to be of thick strong Canvas, & not the thin coarse stuff with wch Chairs are coverd, because they are soon set out. N B all the Chairs to be done in this Manner.[4]

From the description, it is clear that Beverley preferred chairs with slip seats or "loose bottoms" as he called them. If one assumes that the "cases of yellow & white check" were to be tied over the slip seats rather than to the stiles, Beverley intended to have slipcovers that could be tied on over the damask before the seats were placed in the chair frame. Beverley probably reserved the yellow wool damask covers for formal occasions.[5] Occasionally owners had chairs finished "in linen" until permanent upholstery was nailed on or a slipcover was made to match the room furnishings. Thomas Chippendale finished chairs in linen for Sir Edward Knatchbull of Mershamle-Hatch, Kent, while the intended needlework was being completed by his wife. In his recommendation for case material Chippendale recognized that the wool serge commonly used was out of keeping with the light painted Chinese wallpaper Knatchbull had chosen: "as the Chairs can only at present be finishd in Linnen We should be glad to know what kind of Covers you would please to have for them–Serge is most commonly usd but as the room is hung with India paper, perhaps you might Chuse some sort of Cotton–suppose a green Stripe Cotton which at this is fashionable." John Cadwalader's accounts with Philadelphia upholsterers Plunket Fleeson and John Webster provide a contemporary parallel from the colonies. Between October 8, 1770, and January 28,1771, Fleeson charged John Cadwalader £ 33.3.10 for labor and materials for thirty-two chairs, three sofas, and an easy chair, all of which he "finish'd in Canvis." In January 1772, Webster made silk cases for the sofas and twenty chairs with fabric that Cadwalader ordered from a London firm, Rushton and Beachcroft, in the summer of 1771. In the interim, Fleeson fitted the chairs with "fine Saxon blue" check cases with blue and white fringe. Although Webster's bill was somewhat vague, a February 12, 1772, entry in John Cadwalader's waste book recorded that he was paid £18.17.10 for "making Curtains in front &. back Rooms, Covers to Settee's & Covers to Chairs in front &. back Rooms." The side chair illustrated in figure 4 may have been one of those in the front room. If so, it almost certainly had a "Rich Blue Silk Damask" cover with narrow blue silk fringe.[6] The silks used for Cadwalader's furniture covers were en suite with the curtain fabrics in the front and back parlors of his house.

Easy chairs often had loose cases. The Massachusetts chair illustrated in figure 5 has its original foundation upholstery. The absence of nail holes for an outer textile proves that the chair was always fitted with a removable cover (figs. 6, 7). Such covers could be tightly fitted to follow the contours of the chair, or they could be constructed simply to drape over the frame. The Rhode Island easy chair illustrated in figure 8 probably had an informal, loosely fitted cover. Made around 1790, it has a removable slip seat (not shown) that covers a hole for a chamber pot.

Scholars traditionally have assumed that case covers were intended to protect textile upholstery, but covers were as often used to protect the wooden elements of furniture. This was especially true of gilt and inlaid surfaces that were particularly susceptible to abrasion or light. It is difficult to envision expensive pieces of furniture shrouded in case covers, but that was exactly the situation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The elaborate set of chairs and sofas made for Sir Lawrence Dundas's London house were among Thomas Chippendale's most expensive seating furniture. The chairs cost Dundas £2o each not counting the cost of the damask and were described by Chippendale as "exceeding Richly Carv'd in the Antick manner & Gilt in oil Gold." They were double the price of the most luxurious chairs (which had serge covers) Chippendale provided for Harewood House. Because of their opulence, Dundas's chairs and sofas had two sets of cases, one of crimson check and one of leather lined with flannel. The leather cases may have resembled the embossed or "damask leather" fragment illustrated in figure 9. Undoubtedly made for the back of a large armchair, the sides of this cover were cut to fit around the arms, and the top was shaped to accommodate a carved wooden crest. Internal evidence indicates that the cover once was sewn to a back piece (now lost). The cover has a tradition of use in Ham House, although it does not fit any of the furniture now surviving there.[7]

The inventories for Ham House, dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century, also list leather covers for billiard tables, for oval cedar tables, for five different sets of tables and stands, and for a portion of an inlaid floor. Two leather tabletop covers with a history of use at Ham House may have been among those inventoried, although, like the chair cover, they do not fit any furniture now at Ham. One is an oval of patterned leather approximately 28" x 40" with an overhang of about 1 ½". The other cover is circular, about 27" in diameter, and stamped with a small floral pattern typical of seventeenth-century design (fig. 10). Although no American examples of leather furniture covers are known to have survived, they occasionally were listed in seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century inventories. An appraisal of the estate of Thomas Notley of St. Mary's County, Maryland, in April 1679 listed "3 Leather Carpetts" and a "Table with Leather Carpett." "One painted leather Coverlid for a large Table old" and "2 stampt Leather Coverlids for tables" were included in the effects of James Phillips of Baltimore County in 1724.[8]

The practice of protecting tables with leather continued well into the following century. Elaborate covers were made to protect the pair of carved and gilt console tables designed by Robert Adam and executed by France and Bradbury for Dundas in 1765. The table used in Dundas's drawing room came with "a Brown Leather Cover lin'd with flannel with a fall to hang quite to the floor welted and bound with Gilt Leather." An inventory taken three years later noted that the leather cover was still on the table in that room. The tables have pedestals carved with rams heads, husks, and swags, but this elaborate carved-and-gilded decoration was hidden by the leather that hung "quite to the floor."[9] Dundas had spent an enormous amount of money on his furnishings, and he took every precaution to protect them.

The cost of covers was minimal in comparison to the textiles and furniture they protected. The magnificent "Diana and Minerva" commode that Chippendale made for Harewood House at a cost of £86.0.0 was accompanied by a damask leather cover for which he charged £1.0.0.[10] Designed to protect the elaborate marquetry top, this cover probably resembled the one illustrated in figure 11.

The practice of covering commodes and other highly finished pieces of furniture continued in the early nineteenth century. In his Cabinet Dictionary, Sheraton described "Covers for pier tables, made of stamped leather and glazed, lined with flannel to save the varnish of such table tops." He also advocated newly introduced painted canvas (similar to later oilcloth) that he deemed superior to leather.[11]

Just as covers were used to protect furniture, textiles were used to protect the items stored within the furniture. Several of Thomas Chippendale's invoices mention "bays aprons" among the materials for making clothespresses. One of the earliest surviving bills of Chippendale's firm, dated January 29, 1757, listed "A mahogany Cloaths-press wt sliding shelves £6 6–[and] Bayes tape tacks &c. £0:10:0." The clothespress for the "Little Room" or closet next to the State bedchamber at Nostell Priory was invoiced in Chippendale's bills as "A Cloaths Press very neatly Japan'd green and Gold with folding doors and drawers under, Sliding Shelves lin'd with marble paper and bays Aprons £24." An examination of the interior of this clothespress in 1981 revealed the drawers had their original marble paper and pieces of loosely woven green napped wool trapped beneath nailed-down tape at the front of each drawer-remnants of the "bays Aprons" invoiced with the press. Chippendale explained the use of baize aprons in the first edition of The Gentleman and CabinetMaker's Director (1754). For the clothespress in plate rah, he specified sliding shelves "which should be covered with green baize to cover the clothes." The soft wool covers protected the piles of clothing, preventing abrasion and snagging on the shelf above. To remove the clothing, a householder or servant drew back the covers and simply allowed them to hang down from the front of the drawer, much like an apron. A clothespress attributed to London cabinetmaker Giles Grendey also shows evidence of baize aprons; at the front edges of the sliding drawers are remnants of green napped wool trapped beneath ½" wool twill tape, nailed down at 3½" intervals (figs. 12-14). Baize aprons continued to be used in the nineteenth century. In The Cabinet Dictionary, Sheraton stated that "bays, or baize" as "used by cabinet-makers, to tack behind clothes press shelves, to throw over the clothes." In connection with a wardrobe illustrated in the third edition of his Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing Book (1793, revised ed., 1802), he wrote: "The upper middle part contains six or seven clothes press shelves, generally made about six, or six inches and an half deep, with green baize tacked to the inside of the front to cover the clothes with."[12]

The fabric named "bays" or "baize" was made of plain weave wool, woven rather loosely, and usually napped to give it a soft, shaggy surface. Sheraton defined it as "a sort of open woolen stuff, having a long nap, sometimes frized, and sometimes not. This stuff is without wale, and is wrought in a loom with two treadles like flannel." In addition to being used for carpet and clothing covers, this soft, napped fabric was used across service doors to buffer the noise of kitchen wings from the principal rooms of large houses. Chippendale also used it to line a plate closet at Harewood House, probably to keep the silver stored inside free of scratches.[13]

Long associated with the green wool fabric used on card tables and writing surfaces, baize is a familiar word to most furniture historians. Yet the use of the name "baize" for this textile is erroneous in an eighteenthcentury context. Chippendale and Sheraton consistently used the term "cloth" (usually green) for the writing surfaces of desks and for the tops of billiard tables. For example, Sheraton suggested that the fall or writing part on the gentleman's secretary illustrated in figure 15 be "lined with green cloth."[14]

Both "baize" and "cloth" were made of wool and were often dyed green, but they were very different textiles. Where baize was woven loosely and the nap generally left long, cloth was a more expensive textile that was woven closely, fulled or shrunk after weaving to give it a dense texture, with a nap shorn close after weaving, resulting in a velvety, mat surface resembling felt. Cloth often was woven in very wide widths on two-man looms, hence the term "broadcloth." After years of use, the nap of cloth often wears away, allowing the tabby weave construction to show, but when new the velvety surface of the short nap obscured the woven structure. Smooth, dense, and slightly cushioned, cloth made an excellent writing surface for quill pens. The shaggy, open surface of true eighteenth-century baize would have allowed the pen to pierce the paper. By the early nineteenth century the terminology and perhaps the character of the textiles began to change. In 1809, Philip Ludwell Grymes of Virginia had "1 Mahogany writing Table, covered with green Baize," and in 1839 William Blathwayt of Dyrham Park near Bath, England, had a "Large Mahogany Library Table with Baize Top."[15] For the eighteenth century, however, "cloth" was the material used to top writing surfaces and card tables.

Protective liners and covers clearly were both functional and decorative. The gathered fabric curtains shown on the upper doors of Sheraton's gentleman's secretary were to protect the books from dust and light (or perhaps camouflage a messy interior) and to provide a colorful, patterned (from the gathers) background for the muntins (fig. 15). Silk almost invariably was used for curtains, and here, too, the color green predominated. In 1760, Thomas Chippendale billed a customer for "Sewing Silk brass pins & making 4 silk curtains for your bookcase" and "7 yds Green Lutstring" for the purpose. Ince and Mayhew's 1762 book of designs illustrated a ladies' secretary described as having a "green Silk Curtain" over the open shelves. More than thirty years later Sheraton recommended the same color silk for several bookcases illustrated in his Drawing Book.[16]

In some instances the cabinetmaker tacked the curtains to the doors. For example, Sheraton wrote that a silk curtain with drapery ornamentation at the top was made by first assembling the silk pieces, after which "both are tacked into a rabbet together." Both plain and ornamental curtains were used in the colonies. A Williamsburg desk-and-bookcase has eighteenth-century tack holes on the stiles and upper and lower rails of each door indicating that it originally was fitted with curtains (fig. 16). Strips of wool tape, leather, or wooden nailers may have been used occasionally to hold the curtain fabric and prevent it from tearing. George Smith instructed that his bookcase doors "may be used with or without glass in the pannels, at pleasure; the doors having curtains of silk, to slide on rods, as occasion may require." A brocaded silk curtain (later dyed green) was used in front of a built-in corner cupboard in the Jonathan Sayward House in York, Maine. The fabric was shirred on a string from a narrow casing."[17] Built-in bookcases also were fitted with curtains, as an amusing satirical print from the 1760s indicates (fig. 17).

Protective textiles originally used with furniture often have perished, whereas the more sturdy wooden elements have survived. However, the frames retain evidence of their use-telltale nail or screw holes-waiting to be "read" by those literate in the visual language of original construction methods. More importantly, the use of ephemeral but important slipcovers may have been instrumental in the very survival of the furniture itself.

Rodris Roth, Floor Coverings in Eighteenth-Century America (Washington: Smithsonian Press, 1967), p. 28. Inventory, 19 Arlington Street, London, 1768, as quoted in Anthony Coleridge, "Sir Lawrence Dundas and Chippendale," Apollo 86, no. 67 (September 1967): 195. Ninan Horne to Chippendale, Haig and Company, June 20, 1789, quoted in Karin M. Walton and Christopher Gilbert, "Chippendale's Upholstery Branch," Leeds Art Calendar, no. 74 (1974) : 26. For more on carpet covers, see Christopher Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, 2 vols. (London: Studio Vista, 1978), 1: 209, 216-17, 219, 251, 265. Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Dictionary (London, 1803), annotated reprint, Wilford P. Cole and Charles F. Montgomery, eds. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 1: 4o. Gilbert, Chippendale, 1: 251.

For information about the use of slipcovers, see Florence Montgomery, "Room Furnishings as Seen in British Prints from the Lewis Walpole Library," Antiques 105, no. 3 (March 1974): 522—31; Florence Montgomery, Printed Textiles (New York: Viking, 1970), pp. 78—82; Florence Montgomery, Textiles in America, 1650–1870 (New York: Norton, 1984), pp. 123—27; Linda Baumgarten, "Curtains, Covers, and Cases: Upholstery Documents at Colonial Williamsburg," and Susan B. Swan, "An Analysis of Original Slip Covers, Window, and Bed Furnishings at Winterthur Museum," both in Mark A. Williams et al., eds., Upholstery Conservation (East Kingston, N.H.: American Conservation Consortium, 1990), pp. 160—217.

Chippendale, Haig and Company to Sir Edward Knatchbull, May 7, 1773, as quoted in Gilbert, Chippendale, 1: 226. Chinese wallpaper often was referred to as "India Paper," as it was imported by the East India Company. The bills from Fleeson, from Rushton and Beachcroft, and from Webster are reproduced in Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), pp. 40—41, 51, 69. Household Furniture, February 12, 1772, p. 94, John Cadwalader waste book, Cadwalader Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This entry is important in establishing the location of Cadwalader's chairs and in revealing that they were fitted with two sets of loose covers. The formal silk covers were blue (for the chairs in the front parlor) and yellow (for those in the rear parlor) and made of the same fabric as the window curtains. The covers probably also had narrow fringe to match the larger fringe on the curtains. The materials are listed in the Rushton and Beachcroft bill. The "Inventory of Contents Remaining in Cadwalader['s] House," taken on April 1,1786, listed "1 blue damask settee cover," "10 chair do do," and ten yellow damask chair "bottoms" (transcribed in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 72—73). The author thanks Luke Beckerdite for the Cadwalader references.

Invoice, Thomas Chippendale to Sir William Robinson, July 7, 1760, as quoted in Gilbert, Chippendale, 1: 143. "Lutstring" or lustring was a crisp, thin silk (Montgomery, Textiles in America, p. 283). William Ince and John Mayhew, The Universal System of Household Furniture, Ralph Edwards, ed. (London, 1762; reprint, London: Alec Tiranti, 1960), pl. 18. Sheraton, Drawing-Book, pp. 399, 404; supp. pp. 7, 56, 60. Other colors may have been added to the palette early in the nineteenth century. Sheraton recommended green, white, or pink silk, fluted behind the wire doors of commodes (Sheraton, Dictionary, 1: 172, and 2: 332—33).