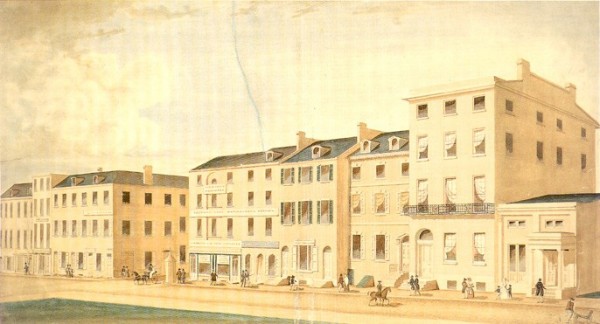

View of Walnut Street Between Third and Fourth Streets, Philadelphia, 1830—1840. Watercolor on paper. 18 3/4" x 33 1/2". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.) Hancock's rented four-story brick wareroom is shown on the left corner. An insurance survey indicated that building was 31' x 43' and that the middle two floors were partitioned into two rooms. The building was centrally located in Philadelphia's commerical district, directly opposite the merchants' Exchange and close to the waterfront.

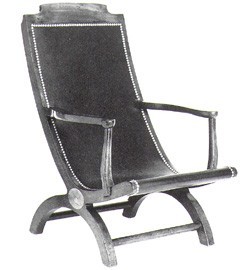

Rocking chair, labeled "John Hancock & Co.," Philadelphia, 1831—1840. Maple, mahogany, and pine H. 41", W. 24", D. 27". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 90.82.) A roll of curled hair forms a headrest, a thin padding of hair sandwiched between two pieces of fabric and twined to the spindles forms the back upholstery, and two pieces of fabric padded with hair form the arm panels. The replaced burlap cover of the left arm has been removed, revealing the curled hair and tow stuffing. The perimeter of the finish cover had a matching gimp and closely spaced brass nails.

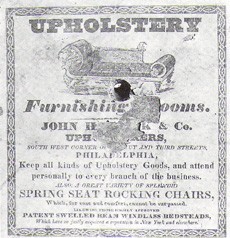

Label on the underside of the rocking chair seat illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The firm remained at Walnut and Third streets until 1840.

Campeche chair, Philadelphia, 1810—1820. Mahogany, satinwood inlay. H. 37 1/2", W. 23 7/8", D. 30 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) The original owner of this chair was Franklin Bache (1797—1864), Benjamin Franklin's great grandson.

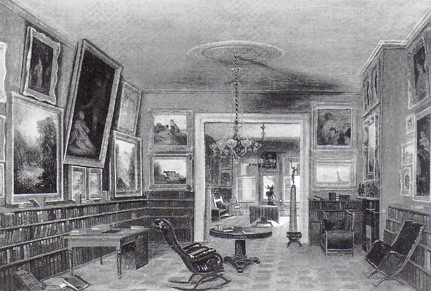

George Bacon Wood, Jr., Interior of the Library of Henry C. Carey, Philadelphia, 1879. 14" x 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Gift of the artist.)

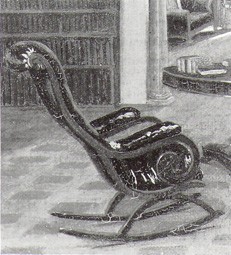

Detail of the Spanish rocking chair in the left foreground of the painting in fig. 5. The chair appears to have been upholstered in green plush. (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Gift of the artist.)

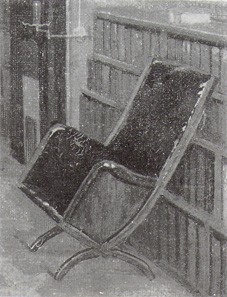

Detail of the Spanish armchair in the right foreground of the painting in fig. 5. The chair also appears to have been upholstered in green plush. (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Gift of the artist.)

The firm John Hancock and Company opened "Upholstery Furnishing Rooms" at the southwest corner of Third and Walnut streets in Philadelphia in May 1830. When the proprietor John Hancock died in 1835, the stock-in-trade and debts to the estate totaled over S24,000. The probate documents-will, executor's account, and an extensive shop inventory (see appendix) -which record the stock, materials, tools, and trade of a large upholstery and furnishing business of the 1830s, are an invaluable source to both cultural and decorative arts historians.[1]

John Hancock (born 1803, Brookline, Mass.) was one of four ambitious and entrepreneurial brothers who entered the furniture trade. Two brothers remained in Boston-Henry (born 1788, Roxbury, Mass.), a chairmaker and cabinetmaker from 1816 to 1851, and William (born 1794, Roxbury), an upholsterer from 1819 to 1849. A third brother, Belcher (born 1800, Brookline), was an upholsterer and moved with John to Philadelphia (fig. 1). The executor's account demonstrates that John Hancock and Company was the Philadelphia branch of an extensive upholstery and decorating business. John owned a one-fourth interest in his firm; William probably supplied the rest of the capital and materials.[2]

The inventory of the stock-in-trade of John Hancock and Company sheds light on the size and scope of Hancock's enterprise and the upholstery trade during the early nineteenth century. The firm produced a variety of expensive seating and bed and window furniture. By 1835 the stock included more than 200 chairs and sofas that were retailed directly through the wareroom. The proportion of unupholstered frames to upholstered chairs suggests that the firm maintained a smaller number of finished goods and numerous frames, which were upholstered to order from a variety of fabrics and trims.

Rocking chairs represented more than half of the stock of seating furniture. Eighty-six were spring-seat rockers made of mahogany, walnut, or less expensive woods such as maple, painted to simulate rosewood or curled maple. The firm also kept in stock 150 inexpensive maple rocking chairs without upholstery, variously described as "scroll seat"; "nurse" ("high" and "low back," "small," "scroll seat," "best quality," and "inferior kind"); "[New?] York Pattern"; and "common."

Fifty rosewood-grained rocking chairs outnumbered all other types, and references in Philadelphia household inventories from 1830 to 1845 attest to the popularity of these fancy rocking chairs with plush covers. Guillema Evans, for example, had "one Elastic Spring Seat Rocking Chair covered with green velvet."[3] One surviving "Im[ita]t[ion] Rosewood Rocking Chair" has its original spring seat and curled hair and tow foundation (figs. 2, 3). The cushion has five helical iron wire springs that are secured to a plank deck and twined in place.

Hancock and Company sold Spanish arm and rocking chairs, based on late-eighteenth-century campeche chairs (fig. 4), in both black walnut and mahogany and probably finished them in morocco (a goatskin leather with a grained surface), plush (a woolen velvetlike fabric, with a long pile), and haircloth (a fabric with a horsehair weft). Henry C. Carey, who owed Hancock's estate $118 in 1835, had two types of Spanish chairs in his library and may well have purchased them from Hancock's firm (figs. 5-7).

Smaller quantities of stylistically innovative or patent furniture were in stock. Among these were "Groove Arm Chairs" that may have resembled Louis XV chairs with molded or reeded backs. The "Self-Acting Chairs," or "London Recumbent Chair," which the firm advertised in 1833, is illustrated by a reclining chair sold by William Hancock. The design of this chair, with a sliding footrest beneath the front rail and a ratchet-and-hinge system that allows the arms to slide and the back to recline, may have been inspired by London cabinetmaker William Pocock's design for a "Reclining Patent Chair" published in Rudolf Ackermann's Repository of Arts in 1813.[4]

The firm's printed label suggests that "easy chair" referred to any chair with upholstered arms and back. The inventory included two easy chairs, fourteen easy chair frames, and a loose cover for an easy chair. The reference to "Tin Chair Pans" indicates that at least some of Hancock's easy chairs were fitted as close stools.

Like eighteenth-century upholsterers, Hancock and Company probably made to order much of its bedding and bed and window hangings. Although the firm maintained a substantial stock of curtain fabrics, trims, and fixtures, only five completed sets of bed hangings and a set of window curtains were in the wareroom. The appraisers found one-half dozen ready-made hair mattresses, one spring mattress, and twenty-six feather pillows and also inventoried seventy-nine ticks for beds, bolsters, and pillows, and seventy-nine yards of ticking. Feathers were processed in a kiln, and four hundred pounds of feathers were on hand. One "rattan palias" is the only mattress stuffed with cheap plant fiber; "cane shavings" were substituted for the more commonly used Spanish moss, cattail, or chaff.[5]

In a span of five years, John Hancock, with the financial and material support of his brothers, built the largest upholstery and decorating firm in Philadelphia. The company produced a relatively small line of innovative spring-seated chairs, sofas, and stools, which they finished to suit a range of customers. In part their success was linked to this flexibility, to aggressive advertising and marketing, and to the existence of a growing urban middle class of consumers. The inventory, which catalogues the stock, tools, and materials used by John Hancock and Company, sheds light on an important entrepreneurial venture of the 1830s. It is a rich document that provides a key to further interpretation of this period in American history.

Page Talbott, "Boston Empire Furniture, Part II," Antiques 109, no. 5 (May 1976): 1006—7. After John's death Belcher managed the firm with a fifth sibling, James B. Hancock (born 1810, Brookline), until 1840. Inward Coastal Manifests, 1830—1835, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 1830 to 1833, manifests for thirty vessels record more than sixty-six shipments amounting to 158 chairs, 379 packages and 68 bundles of chairs, 69 boxes and 26 bales of merchandise, too pounds and 4 bags of "hare," and other goods.